Sesostris on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sesostris ( grc-gre, Σέσωστρις), also transliterated as Sesoösis, or Sesonchosis, is the name of a legendary king of ancient Egypt who, according to

Sesostris ( grc-gre, Σέσωστρις), also transliterated as Sesoösis, or Sesonchosis, is the name of a legendary king of ancient Egypt who, according to

Sesostris ( grc-gre, Σέσωστρις), also transliterated as Sesoösis, or Sesonchosis, is the name of a legendary king of ancient Egypt who, according to

Sesostris ( grc-gre, Σέσωστρις), also transliterated as Sesoösis, or Sesonchosis, is the name of a legendary king of ancient Egypt who, according to Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

, led a military expedition into parts of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. Tales of Sesostris are probably based on the life of Senusret I

Senusret I (Middle Egyptian: z-n-wsrt; /suʀ nij ˈwas.ɾiʔ/) also anglicized as Sesostris I and Senwosret I, was the second pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt. He ruled from 1971 BC to 1926 BC (1920 BC to 1875 BC), and was one of the mos ...

, Senusret III

Khakaure Senusret III (also written as Senwosret III or the hellenised form, Sesostris III) was a pharaoh of Egypt. He ruled from 1878 BC to 1839 BC during a time of great power and prosperity, and was the fifth king of the Twelfth Dynasty of t ...

and perhaps other Pharaohs such as Sheshonq I and Ramesses II

Ramesses II ( egy, rꜥ-ms-sw ''Rīʿa-məsī-sū'', , meaning "Ra is the one who bore him"; ), commonly known as Ramesses the Great, was the third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Along with Thutmose III he is often regarded a ...

.

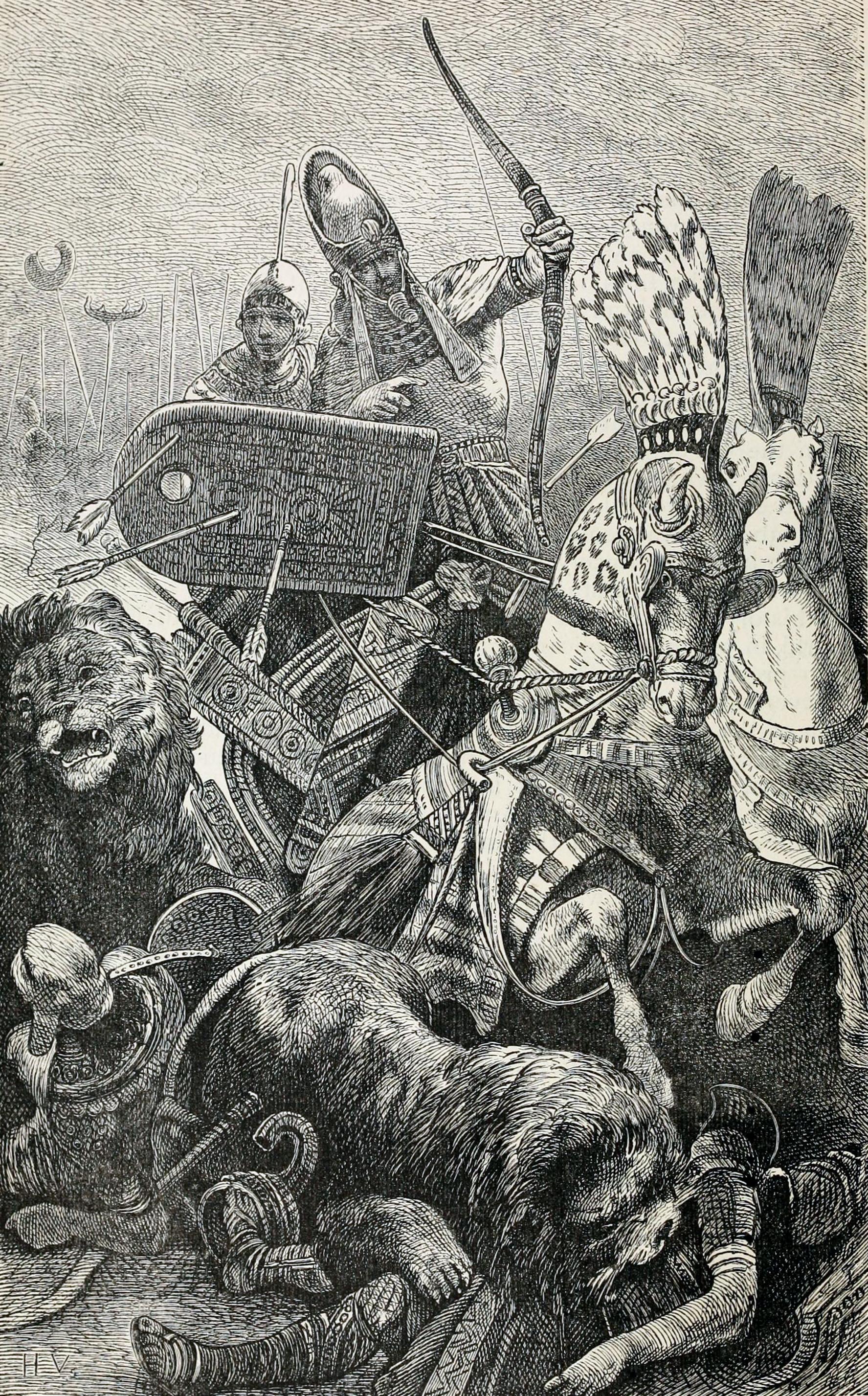

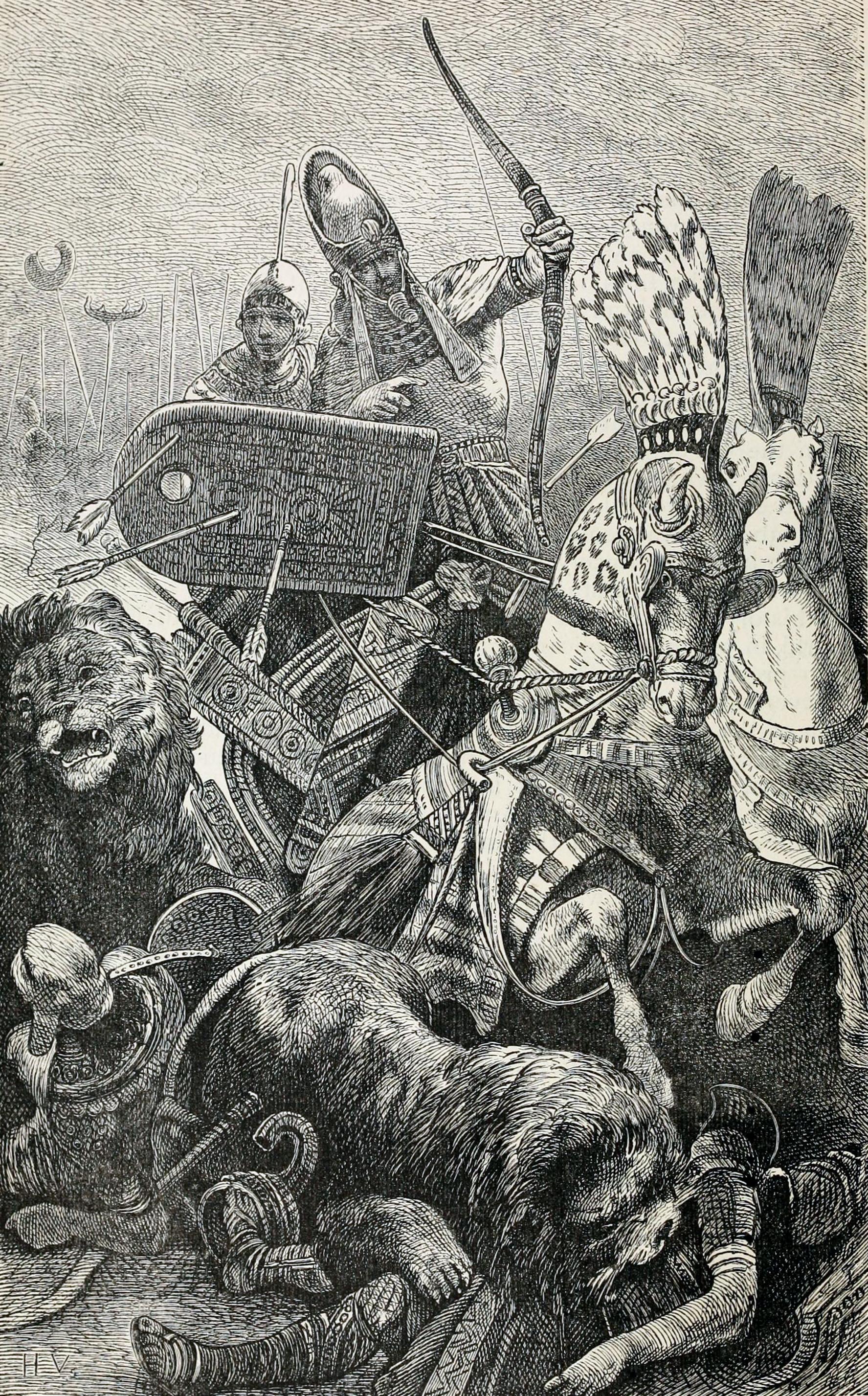

Account of Herodotus

In Herodotus' ''Histories'' there appears a story told by Egyptian priests about a Pharaoh Sesostris, who once led an army northward overland toAsia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, then fought his way westward until he crossed into Europe, where he defeated the Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Cent ...

and Thracians

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied ...

(possibly in modern Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

and Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

). Sesostris then returned home, leaving colonists behind at the river Phasis in Colchis

In Greco-Roman geography, Colchis (; ) was an exonym for the Georgian polity of Egrisi ( ka, ეგრისი) located on the coast of the Black Sea, centered in present-day western Georgia.

Its population, the Colchians are generally though ...

. Herodotus cautioned the reader that much of this story came second hand via Egyptian priests, but also noted that the Colchians were commonly believed to be Egyptian colonists.

Herodotus also relates that when Sesostris defeated an army without much resistance he erected a pillar in their capital with a vulva on it to symbolize the fact that the army fought like women. Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

also makes mention of Sesostris, who, he claims, was defeated by Saulaces, a gold-rich king of Colchis.

Herodotus describes Sesostris as the father of the blind king Pheron, who was less warlike than his father.

According to Professor Alan Lloyd 'The core of Herodotus’ narrative is provided by an Egyptian tradition which presented Sesostris as a model of the ideal of kingship. This certainly contained an historical element, but it has been supplemented and contaminated by folklore, nationalist propaganda, and Greek attitudes."

Diodorus Siculus

According toDiodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

(who calls him ''Sesoosis'') and Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called " Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could s ...

, he conquered the whole world, even Scythia

Scythia ( Scythian: ; Old Persian: ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) or Scythica (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ), also known as Pontic Scythia, was a kingdom created by the Scythians during the 6th to 3rd centuries BC in the Pontic–Caspian steppe.

...

and Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

, divided Egypt into administrative districts or '' nomes'', was a great law-giver, and introduced a caste

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultur ...

system into Egypt and the worship of Serapis

Serapis or Sarapis is a Graeco-Egyptian deity. The cult of Serapis was promoted during the third century BC on the orders of Greek Pharaoh Ptolemy I Soter of the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt as a means to unify the Greeks and Egyptians in his r ...

. Diodorus also wrote that "with regard to this king not only are the Greek writers at variance with one another, but also among the Egyptians the priests and the poets who sing his praises give conflicting stories” (1.53).

Modern research

InManetho

Manetho (; grc-koi, Μανέθων ''Manéthōn'', ''gen''.: Μανέθωνος) is believed to have been an Egyptian priest from Sebennytos ( cop, Ϫⲉⲙⲛⲟⲩϯ, translit=Čemnouti) who lived in the Ptolemaic Kingdom in the early third ...

's ''Aegyptiaca'' (History of Egypt), a pharaoh called "Sesostris" occupied the same position as the known pharaoh Senusret III

Khakaure Senusret III (also written as Senwosret III or the hellenised form, Sesostris III) was a pharaoh of Egypt. He ruled from 1878 BC to 1839 BC during a time of great power and prosperity, and was the fifth king of the Twelfth Dynasty of t ...

of the Twelfth Dynasty

The Twelfth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (Dynasty XII) is considered to be the apex of the Middle Kingdom by Egyptologists. It often is combined with the Eleventh, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth dynasties under the group title, Middle Kingdom. Some ...

, and his name is now usually viewed as a corruption of Senusret/Senwosret/Senwosri. In fact, he is commonly believed to be based on Senusret III, with the possible addition of memories of other namesake pharaohs of the same dynasty, as well as Seti I

Menmaatre Seti I (or Sethos I in Greek) was the second pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt during the New Kingdom period, ruling c.1294 or 1290 BC to 1279 BC. He was the son of Ramesses I and Sitre, and the father of Ramesses II.

The ...

and Ramesses II

Ramesses II ( egy, rꜥ-ms-sw ''Rīʿa-məsī-sū'', , meaning "Ra is the one who bore him"; ), commonly known as Ramesses the Great, was the third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Along with Thutmose III he is often regarded a ...

of the much later Nineteenth Dynasty.

The images of Sesostris carved in stone in Ionia

Ionia () was an ancient region on the western coast of Anatolia, to the south of present-day Izmir. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionia ...

which Herodotus said he had seen are likely to be identified with the Luwian

The Luwians were a group of Anatolian peoples who lived in central, western, and southern Anatolia, in present-day Turkey, during the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. They spoke the Luwian language, an Indo-European language of the Anatolian sub-fam ...

inscriptions of Karabel Pass, the Karabel relief

The Hittite / Luwian Karabel relief is a rock relief in the pass of the same name, between Torbalı and Kemalpaşa, about 20 km from Izmir in Turkey. Rock reliefs are a prominent aspect of Hittite art.

Description

The monument o ...

, now known to have been carved by Tarkasnawa, king of the Arzawa

Arzawa was a region and a political entity (a " kingdom" or a federation of local powers) in Western Anatolia in the second half of the 2nd millennium BC (roughly from the late 15th century BC until the beginning of the 12th century BC). The core ...

n rump state of Mira

Mira (), designation Omicron Ceti (ο Ceti, abbreviated Omicron Cet, ο Cet), is a red-giant star estimated to be 200–400 light-years from the Sun in the constellation Cetus.

ο Ceti is a binary stellar system, consisting of a vari ...

. The kings of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth dynasties were possibly the greatest conquerors that Egypt ever produced, and their records are much clearer than the older dynasties on the limits of Egyptian expansion. Senusret III raided into the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

as far as Shechem

Shechem ( ), also spelled Sichem ( ; he, שְׁכֶם, ''Šəḵem''; ; grc, Συχέμ, Sykhém; Samaritan Hebrew: , ), was a Canaanite and Israelite city mentioned in the Amarna Letters, later appearing in the Hebrew Bible as the first c ...

, also into Ethiopia, and at Semna

The region of Semna is 15 miles south of Wadi Halfa and is situated where rocks cross the Nile narrowing its flow—the Semna Cataract.

Semna was a fortified area established in the reign of Senusret I (1965–1920 BC) on the west bank of the N ...

above the second cataract set up a stela

A stele ( ),Anglicized plural steles ( ); Greek plural stelai ( ), from Greek , ''stēlē''. The Greek plural is written , ''stēlai'', but this is only rarely encountered in English. or occasionally stela (plural ''stelas'' or ''stelæ''), wh ...

of conquest that in its expressions recalls the stelae of Sesostris in Herodotus: Sesostris may, therefore, be the highly magnified portrait of this Pharaoh.

Sesostris is also mentioned in the Alexander Romance where Alexander is described as "the new Sesostris, ruler of the world.

See also

* War of Vesosis and TanausisReferences

Bibliography

* Herodotus ii. 102-1ll * Diodorus Siculus i. 53-59 * Strabo xv. p. 687 *Kurt Sethe

Kurt Heinrich Sethe (30 September 1869 – 6 July 1934) was a noted German Egyptologist and philologist from Berlin. He was a student of Adolf Erman. Sethe collected numerous texts from Egypt during his visits there and edited the ''Urkunden ...

, "Sesostris," in ''Unters. z. Gesch. u. Altertumskunde Agyptens'', tome ii. Hinrichs, Leipzig (1900).

{{authority control

Kings of Egypt in Greek mythology

Kings of Egypt in Herodotus

Senusret III