Seize Mai on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 16 May 1877 crisis (french: link=no, Crise du seize mai) was a

The 16 May 1877 crisis (french: link=no, Crise du seize mai) was a

The 16 May 1877 crisis (french: link=no, Crise du seize mai) was a

The 16 May 1877 crisis (french: link=no, Crise du seize mai) was a constitutional crisis

In political science, a constitutional crisis is a problem or conflict in the function of a government that the political constitution or other fundamental governing law is perceived to be unable to resolve. There are several variations to this ...

in the French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940 ...

concerning the distribution of power between the president and the legislature

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually know ...

. When the royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governm ...

president Patrice MacMahon dismissed the Opportunist Republican prime minister Jules Simon, the parliament on 16 May 1877 refused to support the new government and was dissolved by the president. New elections resulted in the royalists increasing their seat totals, but nonetheless resulted in a majority for the Republicans. Thus, the interpretation of the 1875 Constitution as a parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

prevailed over a presidential system

A presidential system, or single executive system, is a form of government in which a head of government, typically with the title of president, leads an executive branch that is separate from the legislative branch in systems that use separati ...

. The crisis ultimately sealed the defeat of the royalist movement, and was instrumental in creating the conditions of the longevity of the Third Republic.

Background

Following the Franco-Prussian War, the elections for the National Assembly had brought about a monarchist majority, divided intoLegitimists

The Legitimists (french: Légitimistes) are royalists who adhere to the rights of dynastic succession to the French crown of the descendants of the eldest branch of the Bourbon dynasty, which was overthrown in the 1830 July Revolution. They r ...

and Orleanists, which conceived the republican institutions created by the fall of Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephe ...

in 1870 as a transitory state while they negotiated who would be king. Until the 1876 elections, the royalist movement dominated the legislature, thus creating the paradox of a Republic led by anti-republicans. The royalist deputies supported Marshal MacMahon

Marie Edme Patrice Maurice de MacMahon, marquis de MacMahon, duc de Magenta (; 13 June 1808 – 17 October 1893) was a French general and politician, with the distinction of Marshal of France. He served as Chief of State of France from 1873 to 1 ...

, a declared monarchist of the legitimist party, as president of the Republic. His term was set to seven years – the time to find a compromise between the two rival royalist factions.

In 1873, a plan to place Henri, comte de Chambord

Henri, Count of Chambord and Duke of Bordeaux (french: Henri Charles Ferdinand Marie Dieudonné d'Artois, duc de Bordeaux, comte de Chambord; 29 September 1820 – 24 August 1883) was disputedly King of France from 2 to 9 August 1830 as Hen ...

, the head of the Bourbon branch supported by Legitimists, back on the throne had failed over the comte's intransigence. President MacMahon was supposed to lead him to the National Assembly and have him acclaimed as king. However, the Comte de Chambord rejected this plan in the ''white flag

White flags have had different meanings throughout history and depending on the locale.

Contemporary use

The white flag is an internationally recognized protective sign of truce or ceasefire, and for negotiation. It is also used to symboliz ...

manifesto'' of 5 July 1871, reiterated by a 23 October 1873 letter, in which he explained that in no case would he abandon the white flag

White flags have had different meanings throughout history and depending on the locale.

Contemporary use

The white flag is an internationally recognized protective sign of truce or ceasefire, and for negotiation. It is also used to symboliz ...

, symbol of the monarchy (with its fleur-de-lis

The fleur-de-lis, also spelled fleur-de-lys (plural ''fleurs-de-lis'' or ''fleurs-de-lys''), is a lily (in French, and mean 'flower' and 'lily' respectively) that is used as a decorative design or symbol.

The fleur-de-lis has been used in th ...

), in exchange for the republican tricolor. Chambord believed the restored monarchy had to eliminate all traces of the Revolution, especially the Tricolor flag, in order to restore the unity between the monarchy and the nation, which the revolution had sundered. Compromise on this was impossible if the nation were to be made whole again. The general population, however, was unwilling to abandon the Tricolor flag. Chambord's decision thus ruined the hopes of a quick restoration of the monarchy

A monarchy is a government#Forms, form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The legitimacy (political)#monarchy, political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restric ...

. Monarchists therefore resigned themselves to wait for the death of the ageing, childless Chambord, when the throne could be offered to his more liberal heir, the Comte de Paris. A "temporary" republican government was therefore established. Chambord lived on until 1883, but by that time, enthusiasm for a monarchy had faded, and the Comte de Paris was never offered the French throne.

In 1875, Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers ( , ; 15 April 17973 September 1877) was a French statesman and historian. He was the second elected President of France and first President of the French Third Republic.

Thiers was a key figure in the July Rev ...

joined with the initiative of moderate Republicans Jules Ferry

Jules François Camille Ferry (; 5 April 183217 March 1893) was a French statesman and republican philosopher. He was one of the leaders of the Moderate Republicans and served as Prime Minister of France from 1880 to 1881 and 1883 to 1885. He ...

and Léon Gambetta

Léon Gambetta (; 2 April 1838 – 31 December 1882) was a French lawyer and republican politician who proclaimed the French Third Republic in 1870 and played a prominent role in its early government.

Early life and education

Born in Cahors, Ga ...

to vote for the constitutional laws of the Republic. The next year, the elections were won by the Republicans, although the end result was contradictory:

*in the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the e ...

, which gave disproportionate influence to rural areas, the majority was made up of monarchists, who had a majority of only one seat (151 against 149 Republicans)

*in the Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourbon R ...

, the overwhelming majority was composed of republicans.

*the president was MacMahon, an avowed monarchist.

Political crisis was thus inevitable. It involved a struggle for supremacy between the monarchist President of the Republic and the republican Chamber of Deputies.

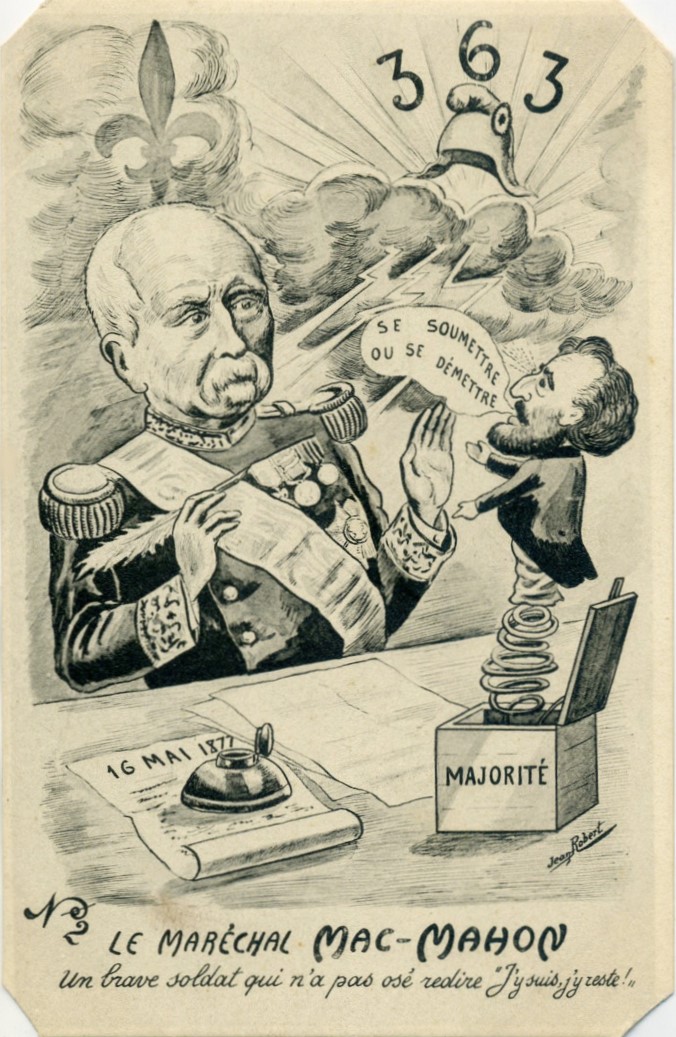

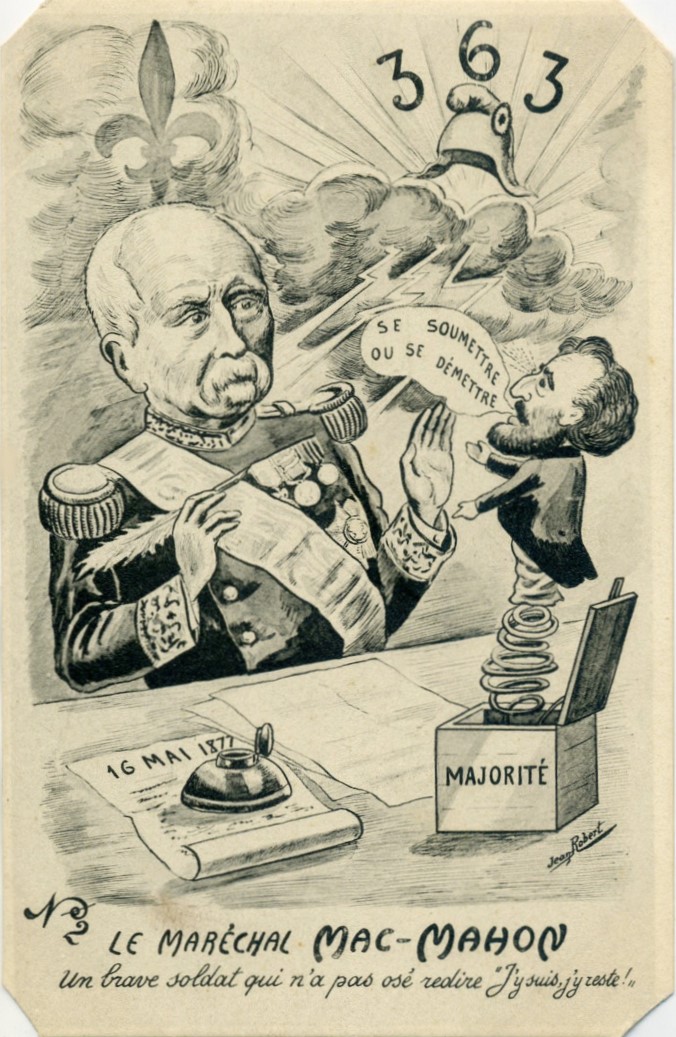

The crisis

The crisis was triggered by President MacMahon, who dismissed the moderate republican Jules Simon, head of the government, and substituted him with a new "Ordre moral" government led by the Orleanist Albert, duc de Broglie. MacMahon favoured a presidential government, while the Republicans in the chamber considered the parliament as the predominant political organ, which decided the policies of the nation. The Chamber refused to accord its trust to the new government. On 16 May 1877, 363 French deputies – among themGeorges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (, also , ; 28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A key figure of the Independent Radicals, he was a ...

, Jean Casimir-Perier

Jean Paul Pierre Casimir-Perier (; 8 November 1847 – 11 March 1907) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1894 to 1895.

Biography

He was born in Paris, the son of Auguste Casimir-Perier, the grandson of Casimir Pie ...

and Émile Loubet

Émile François Loubet (; 30 December 183820 December 1929) was the 45th Prime Minister of France from February to December 1892 and later President of France from 1899 to 1906.

Trained in law, he became mayor of Montélimar, where he was note ...

– passed a vote of no confidence

A motion of no confidence, also variously called a vote of no confidence, no-confidence motion, motion of confidence, or vote of confidence, is a statement or vote about whether a person in a position of responsibility like in government or man ...

(''Manifeste des 363'').

MacMahon dissolved the parliament and called for new elections, which brought 323 Republicans and 209 royalists to the Chamber, marking a clear rejection of the President's move. MacMahon had either to submit himself or to resign, as had Léon Gambetta

Léon Gambetta (; 2 April 1838 – 31 December 1882) was a French lawyer and republican politician who proclaimed the French Third Republic in 1870 and played a prominent role in its early government.

Early life and education

Born in Cahors, Ga ...

famously called for: "When France will have let its sovereign voice heard, then one will have to submit himself or resign" (''se soumettre ou se démettre''''Quand la France aura fait entendre sa voix souveraine, il faudra se soumettre ou se démettre.'' This famous sentence – ''se soumettre ou se démettre'', "to submit oneself or to resign" – is still often used in the modern French political debate.) MacMahon thus appointed a moderate republican, Jules Armand Dufaure

Jules Armand Stanislas Dufaure (; 4 December 1798 – 28 June 1881) was a French statesman.

Biography

Dufaure was born at Saujon, Charente-Maritime, and began his career as an advocate at Bordeaux, where he won a great reputation by his oratori ...

as president of the Council, and accepted Dufaure's interpretation of the constitution:

*ministers are responsible to the Chamber of Deputies (following the 1896 institutional crisis, the Senate obtained the right to control ministers)

*the right of dissolution of parliament

The dissolution of a legislative assembly is the mandatory simultaneous resignation of all of its members, in anticipation that a successive legislative assembly will reconvene later with possibly different members. In a democracy, the new assem ...

must remain exceptional. It was not used again during the Third Republic; even Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), commonly known as Philippe Pétain (, ) or Marshal Pétain (french: Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who attained the position of Marshal of France at the end of World ...

did not dare to dissolve it in 1940.

Aftermath

The crisis sealed the defeat of the royalists. President MacMahon accepted his defeat and resigned in January 1879. The Comte de Chambord, whose intransigence had resulted in the breakdown of the alliance betweenLegitimist

The Legitimists (french: Légitimistes) are royalists who adhere to the rights of dynastic succession to the French crown of the descendants of the eldest branch of the Bourbon dynasty, which was overthrown in the 1830 July Revolution. They ...

s and Orleanists, died in 1883, after which several Orleanists rallied to the Republic, quoting Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers ( , ; 15 April 17973 September 1877) was a French statesman and historian. He was the second elected President of France and first President of the French Third Republic.

Thiers was a key figure in the July Rev ...

' words that "the Republic is the form of government which divides he Frenchthe least". These newly rallied became the first right-wing republicans of France. After World War I (1914–18), some of the independent radicals and members of the right-wing of the late Radical-Socialist Party allied themselves with these pragmatic

Pragmatism is a philosophical movement.

Pragmatism or pragmatic may also refer to:

*Pragmaticism, Charles Sanders Peirce's post-1905 branch of philosophy

* Pragmatics, a subfield of linguistics and semiotics

*'' Pragmatics'', an academic journal i ...

republicans, although anticlericalism

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

remained a gap between these long-time rivals (and indeed continues, to be a main criterion of distinction between the French left-wing and its right-wing).

In the constitutional field, the presidential system

A presidential system, or single executive system, is a form of government in which a head of government, typically with the title of president, leads an executive branch that is separate from the legislative branch in systems that use separati ...

was definitely rejected in favor of a parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

, and the right of dissolution of parliament

The dissolution of a legislative assembly is the mandatory simultaneous resignation of all of its members, in anticipation that a successive legislative assembly will reconvene later with possibly different members. In a democracy, the new assem ...

severely restricted, so much that it was never used again under the Third Republic. After the Vichy regime

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its te ...

, the Fourth Republic (1946–1958) was again founded on this parliamentary system, something which Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

despised and rejected (''le régime des partis''). Thus, when de Gaulle had the opportunity to come back to power in the crisis of May 1958, he designed a constitution that strengthened the President. His 1962 reform to have the president elected by direct universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stan ...

(instead of being elected by deputies and senators) further increased his authority

In the fields of sociology and political science, authority is the legitimate power of a person or group over other people. In a civil state, ''authority'' is practiced in ways such a judicial branch or an executive branch of government.''The Ne ...

. The constitution designed by de Gaulle for the Fifth Republic (since 1958) specifically tailored his needs, but this specificity was also rested on the President's personal charisma

Charisma () is a personal quality of presence or charm that compels its subjects.

Scholars in sociology, political science, psychology, and management reserve the term for a type of leadership seen as extraordinary; in these fields, the term "ch ...

.

Even with de Gaulle's disappearance from the political scene a year after the May 1968 crisis, little changed until the 1980s, when the various cohabitations under President François Mitterrand

François Marie Adrien Maurice Mitterrand (26 October 19168 January 1996) was President of France, serving under that position from 1981 to 1995, the longest time in office in the history of France. As First Secretary of the Socialist Party, h ...

renewed the conflict between the presidency and the prime minister. Subsequently President Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, , ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. Chirac was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to 1988, as well as May ...

proposed to reduce the term of the presidency from seven to five years (the ''quinquennat

A constitutional referendum was held in France on 24 September 2000. Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p674 The proposal to reduce the mandate of the President from seven years to five years was app ...

''), so that both presidential and parlementary elections may be synchronous, in order to avoid any further "cohabitation" and thus conflict between the executive

Executive ( exe., exec., execu.) may refer to:

Role or title

* Executive, a senior management role in an organization

** Chief executive officer (CEO), one of the highest-ranking corporate officers (executives) or administrators

** Executive d ...

and legislative

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known ...

branches. This change was accepted by referendum in 2000.

See also

*Cohabitation (government)

Cohabitation is a system of divided government that occurs in semi-presidential systems, such as France, whenever the president is from a different political party than the majority of the members of parliament. It occurs because such a system ...

*French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940 ...

(1871–1940)

* France in the nineteenth century

References

Further reading

* Brogan, D.W. ''France Under the Republic: The Development of Modern France (1870–1939)'' (1940) pp 127–43. * Mitchell, Allan. "Thiers, MacMahon, and the Conseil superieur de la Guerre." ''French historical studies'' 6.2 (1969): 232–252. {{DEFAULTSORT:1877 05 16 crisis French Third Republic Political history of France 1877 in France France France France Prince Philippe, Count of Paris