Seenotdienst on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Seenotdienst'' (sea rescue service) was a German military organization formed within the ''

The ''Seenotdienst'' (sea rescue service) was a German military organization formed within the ''

Early in 1939, with the growing probability of war against Great Britain, the ''Luftwaffe'' carried out large-scale rescue exercises over water. Land-based German bombers used for search duties proved inadequate in range, so bomber air bases were constructed along the coast to facilitate an air net over the Baltic and North seas. Following this, the ''Luftwaffe'' determined to procure a dedicated air-sea rescue seaplane, choosing a modification of the Heinkel He 59, a twin-engine biplane with floats. A total of 14 He 59s of the oldest models were sent to be fitted with first aid equipment, electrically heated sleeping bags, artificial respiration equipment, a floor hatch with a telescoping ladder to reach the water, a hoist, signaling devices, and lockers to hold all the gear. The Heinkel He 59s were painted white with red crosses to indicate emergency services.Lepage, Jean-Denis G. G. ''Aircraft of the Luftwaffe 1935-1945: An Illustrated History'', p. 315. McFarland, 2009. A varied collection of small surface craft were placed under the command of the air-sea rescue division.

Early in 1939, with the growing probability of war against Great Britain, the ''Luftwaffe'' carried out large-scale rescue exercises over water. Land-based German bombers used for search duties proved inadequate in range, so bomber air bases were constructed along the coast to facilitate an air net over the Baltic and North seas. Following this, the ''Luftwaffe'' determined to procure a dedicated air-sea rescue seaplane, choosing a modification of the Heinkel He 59, a twin-engine biplane with floats. A total of 14 He 59s of the oldest models were sent to be fitted with first aid equipment, electrically heated sleeping bags, artificial respiration equipment, a floor hatch with a telescoping ladder to reach the water, a hoist, signaling devices, and lockers to hold all the gear. The Heinkel He 59s were painted white with red crosses to indicate emergency services.Lepage, Jean-Denis G. G. ''Aircraft of the Luftwaffe 1935-1945: An Illustrated History'', p. 315. McFarland, 2009. A varied collection of small surface craft were placed under the command of the air-sea rescue division.

In August, a few captured French and Dutch seaplanes were modified for rescue and attached to the organization. Some three-engined Dornier Do 24

In August, a few captured French and Dutch seaplanes were modified for rescue and attached to the organization. Some three-engined Dornier Do 24

''Flying boats & seaplanes: a history from 1905'', p. 126.

Zenith Imprint, 1998. In the battle for

As the Allies advanced following the

As the Allies advanced following the

''Seenotdienst der Luftwaffe im Bereich Parow''.

The load was so great that the aircraft was unable to take off—instead, it wave-hopped and taxied back to base. During the same battle, six boats working with the ''Seenotdienst'' made repeated trips March 17–18 to a pier in Kolberg and evacuated 2,356 people.

p. 63.

yellow-painted ''Rettungsbojen'' (sea rescue buoys) were placed by the Germans in waters where air emergencies were likely. The highly visible buoy-type floats held emergency equipment including food, water, blankets and dry clothing enough for four men, and they attracted distressed airmen from both sides of the conflict. British airmen and seamen called them "Lobster Pots" for their shape. German and British rescue boats checked the floats from time to time, picking up any airmen they found, though enemy airmen were immediately made

"Seenotgruppe."

/ref> *

"Seenotflug-Kommando 1."

/ref>

"Seenotdienst: Early Development of Air-Sea Rescue"

''Air University Review'', January–February 1977 * Tilford, Earl H., Jr. ''Search and rescue in Southeast Asia'', pp. 4–8. Center for Air Force History. DIANE Publishing, 1992. * Wadman, David; Adam Thompson. (2009) ''Seeflieger: Luftwaffe Maritime Aircraft and Units, 1935–1945''. Classic Publications. {{refend Luftwaffe Rescue aviation units and formations

The ''Seenotdienst'' (sea rescue service) was a German military organization formed within the ''

The ''Seenotdienst'' (sea rescue service) was a German military organization formed within the ''Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

'' (German Air Force) to save downed airmen from emergency water landing

In aviation, a water landing is, in the broadest sense, an aircraft landing on a body of water. Seaplanes, such as floatplanes and flying boats, land on water as a normal operation. Ditching is a controlled emergency landing on the water s ...

s. The ''Seenotdienst'' operated from 1935 to 1945 and was the first organized air-sea rescue

Air-sea rescue (ASR or A/SR, also known as sea-air rescue), and aeronautical and maritime search and rescue (AMSAR) by the ICAO and IMO, is the coordinated search and rescue (SAR) of the survivors of emergency water landings as well as people ...

service.

The ''Seenotdienst'' was at first operated as a civilian service run by the military, and later was brought formally into the ''Luftwaffe''. Throughout their existence, the group solved a number of organizational, operational and technical challenges to create an effective rescue force. When British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

air leaders observed the German success, they modeled their own rescue forces after the ''Seenotdienst''. As the Allies of World War II

The Allies, formally referred to as the Declaration by United Nations, United Nations from 1942, were an international Coalition#Military, military coalition formed during the World War II, Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis ...

advanced, denying sea areas to German forces, local groups of the ''Seenotdienst'' were disbanded. The last active group served in the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

in March 1945.

1930s

In 1935, Lieutenant Colonel Konrad Goltz of the ''Luftwaffe'', a supply officer based at the port ofKiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the Jutland ...

, was given the task of organizing the ''Seenotdienst'', an air-sea rescue organization that would focus on the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

and the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

. Goltz gained coordination with aircraft units of the ''Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the a ...

'' as well as with civilian lifeboat societies and the '' German Maritime Search and Rescue Service'' (DGzRS, or "Deutsche Gesellschaft zur Rettung Schiffbrüchiger").Tilford, 1977. He held administrative command over the Ships and Boats Group which was organized at Kiel within the ''Luftwaffe''. Goltz was to operate the ''Seenotdienst'' as a civilian organization manned by both military and civilian personnel, with civil registrations applied to the aircraft.

World War II

The first multiple air-sea rescue operation occurred on December 18, 1939. A group of 24 BritishVickers Wellington

The Vickers Wellington was a British twin-engined, long-range medium bomber. It was designed during the mid-1930s at Brooklands in Weybridge, Surrey. Led by Vickers-Armstrongs' chief designer Rex Pierson; a key feature of the aircraft is its ...

medium bomber

A medium bomber is a military bomber Fixed-wing aircraft, aircraft designed to operate with medium-sized Aerial bomb, bombloads over medium Range (aeronautics), range distances; the name serves to distinguish this type from larger heavy bombe ...

s were frustrated by low clouds and fog in their mission to bomb Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsh ...

, and they turned for home. The formation attracted the energetic attention of ''Luftwaffe'' pilots flying Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a German World War II fighter aircraft that was, along with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the backbone of the Luftwaffe's fighter force. The Bf 109 first saw operational service in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War an ...

fighter aircraft

Fighter aircraft are fixed-wing military aircraft designed primarily for air-to-air combat. In military conflict, the role of fighter aircraft is to establish air superiority of the battlespace. Domination of the airspace above a battlefield ...

as well as Bf 110 heavy fighter

A heavy fighter is a historic category of fighter aircraft produced in the 1930s and 1940s, designed to carry heavier weapons, and/or operate at longer ranges than light fighter aircraft. To achieve performance, most heavy fighters were twin-eng ...

s, and more than half of the Wellingtons went down in the North Sea. German ''Seenotdienst'' rescue boats based at Hörnum worked with He 59s to save some twenty British airmen from the icy water.

In 1940 as the German advance moved to occupy Denmark and Norway, the ''Seenotdienst'' added bases along the coasts of those countries. A squadron of obsolescent Dornier Do 18

The Dornier Do 18 was a development of the Do 16 flying boat. It was developed for the ''Luftwaffe'', but ''Luft Hansa'' received five aircraft and used these for tests between the Azores and the North American continent in 1936 and on their ma ...

s that had been used for sea reconnaissance was assigned to air-sea rescue. Some of the Heinkels that had been flying out of the island of Sylt

Sylt (; da, Sild; Sylt North Frisian, Söl'ring North Frisian: ) is an island in northern Germany, part of Nordfriesland district, Schleswig-Holstein, and well known for the distinctive shape of its shoreline. It belongs to the North Frisian ...

were transferred to Aalborg

Aalborg (, , ) is Denmark's List of cities in Denmark by population, fourth largest town (behind Copenhagen, Aarhus, and Odense) with a population of 119,862 (1 July 2022) in the town proper and an Urban area, urban population of 143,598 (1 July ...

in northern Denmark. The two bases in Norway were located at Stavanger

Stavanger (, , American English, US usually , ) is a city and municipalities of Norway, municipality in Norway. It is the fourth largest city and third largest metropolitan area in Norway (through conurbation with neighboring Sandnes) and the a ...

and Bergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipalities of Norway, municipality in Vestland county on the Western Norway, west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the list of towns and cities in Norway, secon ...

. In many cases local rescue societies cooperated with the ''Seenotdienst''.

When the Netherlands and France fell to the German advance in May and June 1940, more rescue bases were put into operation. The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital o ...

and Schellingwoude

Schellingwoude is a neighbourhood of Amsterdam, Netherlands. A former village located on the northern shore of the IJ, in the province of North Holland, it was a separate municipality between 1817 and 1857, when it was merged with Ransdorp; the ...

became rescue bases in the Netherlands, and Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the C ...

and Cherbourg

Cherbourg (; , , ), nrf, Chèrbourg, ) is a former commune and subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French department of Manche. It was merged into the commune of Cherbourg-Octeville on 28 Febr ...

in France hosted rescue units that were soon to be active during the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

. The ''Seenotdienst'' was taken formally into the ''Luftwaffe'' in July 1940, becoming ''Luftwaffeninspektion 16'' (German Air Force Inspectorate 16) under the direction of ''Generalleutnant'' Hans-Georg von Seidel, the Quartermaster General of the ''Luftwaffe'', and thus indirectly under ''General der Flieger

''General der Flieger'' ( en, General of the aviators) was a General of the branch rank of the Luftwaffe (air force) in Nazi Germany. Until the end of World War II in 1945, this particular general officer rank was on three-star level ( OF-8), e ...

'' Hans Jeschonnek

Hans Jeschonnek (9 April 1899 – 18 August 1943) was a German military aviator in the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' during World War I, a general staff officer in the ''Reichswehr'' in the inter–war period and ''Generaloberst'' (Colonel-General) and a ...

, the Chief of the ''Luftwaffe'' General Staff.

Dutch rescue craft belonging to the Noord- en zuid-Hollandsche Redding Maatschappij (NZHRM, translated North and South Holland Sea Rescue Institution) and the Zuid-Hollandsche Maatschappij tot Redding van Schipbreukelingen (ZHMRS) were incorporated into the ''Seenotdienst'' during the occupation of the Netherlands. The fast motor life boats were painted white with red crosses, though twice the boats were strafed by Allied aircraft. Civilian boatmen enjoyed good relations with German authorities. Between 1940 and 1945, the Dutch boats saved some 1,100 seamen and airmen. Near the end of the occupation some local boat commanders defied the Nazi regime, and three Dutch lifeboats escaped across the Channel, one carrying 40 Jews to sanctuary in England.

In response to the heavy toll of German air action against Great Britain July–August 1940, Adolf Galland

Adolf Josef Ferdinand Galland (19 March 1912 – 9 February 1996) was a German Luftwaffe general and flying ace who served throughout the Second World War in Europe. He flew 705 combat missions, and fought on the Western Front and in the Defenc ...

recommended that German pilots in trouble over the ocean make an emergency water landing

In aviation, a water landing is, in the broadest sense, an aircraft landing on a body of water. Seaplanes, such as floatplanes and flying boats, land on water as a normal operation. Ditching is a controlled emergency landing on the water s ...

in their aircraft instead of bailing out and parachuting down. The aircraft each carried an inflatable rubber raft which would help the airmen avoid hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a body core temperature below in humans. Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia, there is shivering and mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases. In severe ...

from continued immersion in the cold water, and increase the time available for rescue. By comparison, British fighters such the Supermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Gri ...

and the Hawker Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane is a British single-seat fighter aircraft of the 1930s–40s which was designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was overshadowed in the public consciousness b ...

did not carry inflatable rafts, only life jackets

A personal flotation device (PFD; also referred to as a life jacket, life preserver, life belt, Mae West, life vest, life saver, cork jacket, buoyancy aid or flotation suit) is a flotation device in the form of a vest or suite that is worn by a ...

which were little help against the cold.

In July 1940, a white-painted He 59 operating near Deal, Kent

Deal is a coastal town in Kent, England, which lies where the North Sea and the English Channel meet, north-east of Dover and south of Ramsgate. It is a former fishing, mining and garrison town whose history is closely linked to the anch ...

was shot down and the crew taken captive because it was sharing the air with 12 Bf 109 fighters and because the British were wary of ''Luftwaffe'' aircraft dropping spies and saboteurs. The German pilot's log showed that he had noted the position and direction of British convoys—British officials determined that this constituted military reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops ( skirmishe ...

, not rescue work. The Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of Stat ...

issued Bulletin 1254 indicating that all enemy air-sea rescue aircraft were to be destroyed if encountered. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

later wrote "We did not recognise this means of rescuing enemy pilots who had been shot down in action, in order that they might come and bomb our civil population again." Germany protested this order on the grounds that rescue aircraft were part of the Geneva Convention

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conve ...

agreement stipulating that belligerents must respect each other's "mobile sanitary formations" such as field ambulances and hospital ship

A hospital ship is a ship designated for primary function as a floating medical treatment facility or hospital. Most are operated by the military forces (mostly navies) of various countries, as they are intended to be used in or near war zones. I ...

s. Churchill argued that rescue aircraft were not anticipated by the treaty, and were not covered. British attacks on He 59s increased. The ''Seenotdienst'' ordered the rescue aircraft armed as well as painted in the camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

scheme of their area of operation. The use of civil registration and red cross markings was abandoned. A ''Seenotdienst'' gunner shot down an attacking No. 43 Squadron RAF Hurricane fighter on July 20. Rescue flights were to be protected by fighter aircraft when possible.

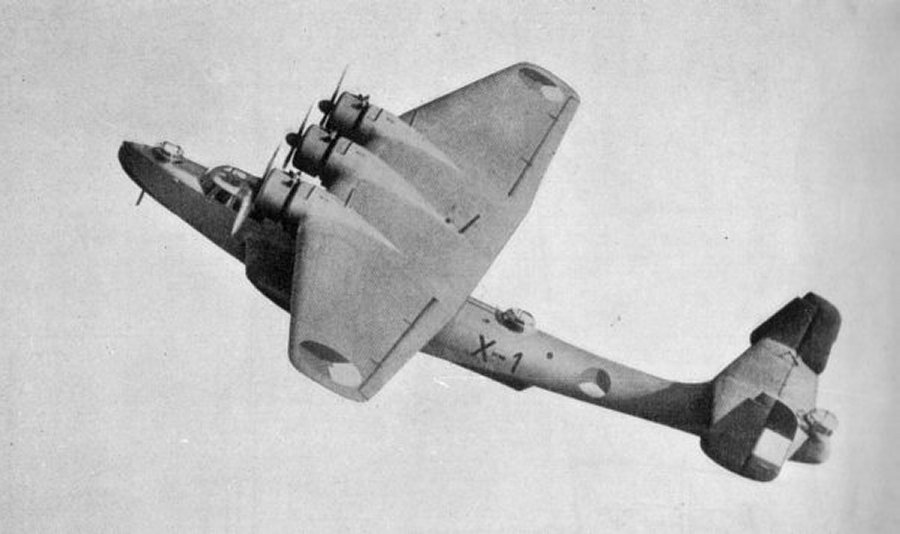

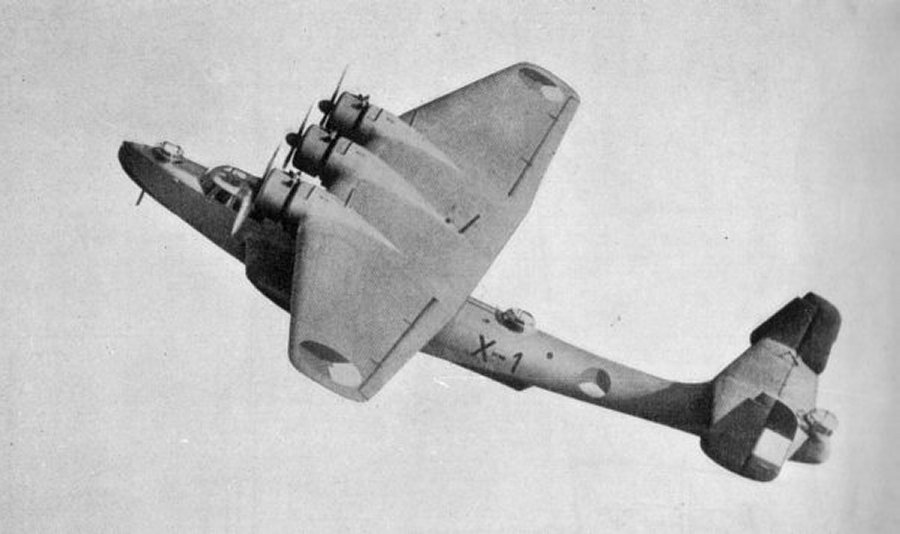

In August, a few captured French and Dutch seaplanes were modified for rescue and attached to the organization. Some three-engined Dornier Do 24

In August, a few captured French and Dutch seaplanes were modified for rescue and attached to the organization. Some three-engined Dornier Do 24 flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fuselag ...

s that were built in the Netherlands, and eight French Breguet Br.521 ''Bizerte'' models were refitted with standard ''Seenotdienst'' rescue supplies. Further bases set up at Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very ...

, Brest, St. Nazaire

Saint-Nazaire (; ; Gallo: ''Saint-Nazère/Saint-Nazaer'') is a commune in the Loire-Atlantique department in western France, in traditional Brittany.

The town has a major harbour on the right bank of the Loire estuary, near the Atlantic Oce ...

and Royan. More aircraft were brought under ''Seenotdienst'' command on an ''ad hoc'' basis, depending on the urgency. On May 22, 1941 in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

off the coast of Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

, a squadron of Do 24s was called upon to rescue survivors of the sinking of the —some 65 British sailors were picked up.Nicolaou, Stéphane''Flying boats & seaplanes: a history from 1905'', p. 126.

Zenith Imprint, 1998. In the battle for

Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, some 1,000 rescue missions were flown by Do 24s, with many shot down. In saving Italian sailors from the battleship ''Roma'', four out of five Do 24T aircraft were shot down. The fifth flying boat rescued 19 men.

British and American response

During the first two years of war, the British Royal Air Force Marine Branch had no coordinated air-sea rescue units—only about 28 crash boats and no dedicated aircraft. The ditching of a British aeroplane in the Channel or the North Sea usually doomed its crew. The fate of downed airmen was primarily in the hands of their parent organization, and they had little they could do to help the crash boats locate the accident site. In January 1941, a Directorate of Air-Sea Rescue was formed by theRoyal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

for the purpose of saving those in distress at sea, especially airmen. Proper provisioning of rescue squadrons was slow, and it took more than a year for sea-going rescue boats and aircraft to come together in active ASR squadrons. Between February and August 1941, of the 1,200 British airmen that landed in the Channel or the North Sea, 444 were rescued, with 78 more picked up and interned by the ''Seenotdienst''.Tilford, Earl H., Jr. ''Search and rescue in Southeast Asia'', pp. 4–8. Center for Air Force History. DIANE Publishing, 1992. The organization copied much from the successful efforts of the ''Seenotdienst''. British air-sea rescue units began in September 1942 to work with the United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

to coordinate rescue activities over the Channel and the North Sea. Observers from the U.S. took cues from both the ''Seenotdienst'' and the British rescue operations. The combined US-UK effort led to the saving of some 2,000 American fliers from the seas around the UK. From the time of its inception to the end of the war, the British effort alone rescued 13,629 people from the ocean, 8,000 of which were airmen.

Retreat

As the Allies advanced following the

As the Allies advanced following the invasion of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norm ...

in June 1944, the ''Luftwaffe'' pulled bases back to keep them from being overrun. Units of the ''Seenotdienst'' whose areas of operation were threatened by Allied activity were disbanded or reorganized into other groups with safer locations. For instance, in July 1944, surrounded by the U.S. VIII Corps gathering to attack Brest, ''Seenotstaffel 1'' that had been operating there since June 1940, with a southern detachment at Hourtin

Hourtin (; oc, Hortin, ) is a commune of southwestern France, located in the Gironde department, administrative region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine (before 2015: Aquitaine). It is located in the canton Le Sud-Médoc, part of the district of Lesparre- ...

, was sent to Pillau

Baltiysk (russian: Балти́йск; german: Pillau; Old Prussian: ''Pillawa''; pl, Piława; lt, Piliava; Yiddish: פּילאַווע, ''Pilave'') is a seaport town and the administrative center of Baltiysky District in Kaliningrad Oblast, Ru ...

in the Baltic Sea, then redesignated ''Seenotstaffel 60'' in August. In November 1944, German leadership decided that the flying boat manufacturing resources could be put to better use elsewhere, and ordered the Dornier factory to cease making Do 24s.

The most persons that a single ''Seenotdienst'' aircraft rescued in one sortie was 99 children and 14 adults carried by a Do 24, saved from orphanages threatened by the Soviet advance into Koszalin

Koszalin (pronounced ; csb, Kòszalëno; formerly german: Köslin, ) is a city in northwestern Poland, in Western Pomerania. It is located south of the Baltic Sea coast, and intersected by the river Dzierżęcinka. Koszalin is also a county-sta ...

during the Battle of Kolberg at the beginning of March 1945.Kieschnick, Peter. (2007''Seenotdienst der Luftwaffe im Bereich Parow''.

The load was so great that the aircraft was unable to take off—instead, it wave-hopped and taxied back to base. During the same battle, six boats working with the ''Seenotdienst'' made repeated trips March 17–18 to a pier in Kolberg and evacuated 2,356 people.

Rescue equipment

During the Battle of Britain, a problem that the ''Seenotdienst'' observed among both British and German aircrew was termed ''Rettungskollaps'' (rescue collapse)—a number of rescued fliers lost consciousness and died some 20–90 minutes after being pulled from the icy water. Investigation into the matter was initiated, including experiments on prisoners atDachau concentration camp

,

, commandant = List of commandants

, known for =

, location = Upper Bavaria, Southern Germany

, built by = Germany

, operated by = ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS)

, original use = Political prison

, construction ...

which involved submersing men in extremely cold water to induce severe hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a body core temperature below in humans. Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia, there is shivering and mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases. In severe ...

. The human subjects were then warmed up using various methods under analysis such as being wrapped in an electrically-heated sleeping bag, or being bathed in warm or hot water. Some 80–100 prisoners died in the process.

In October 1940 at the suggestion of Ernst Udet

Ernst Udet (26 April 1896 – 17 November 1941) was a German Reich, German pilot during World War I and a ''Luftwaffe'' Colonel-General (''Generaloberst'') during World War II.

Udet joined the Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte, Imperial German Ai ...

,Wadman, 2009p. 63.

yellow-painted ''Rettungsbojen'' (sea rescue buoys) were placed by the Germans in waters where air emergencies were likely. The highly visible buoy-type floats held emergency equipment including food, water, blankets and dry clothing enough for four men, and they attracted distressed airmen from both sides of the conflict. British airmen and seamen called them "Lobster Pots" for their shape. German and British rescue boats checked the floats from time to time, picking up any airmen they found, though enemy airmen were immediately made

prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of ...

.

The ''Seenotdienst'' carried out its own studies that determined which new rescue inventions were to be incorporated throughout the ''Luftwaffe''. A bright green fluorescein

Fluorescein is an organic compound and dye based on the xanthene tricyclic structural motif, formally belonging to triarylmethine dyes family. It is available as a dark orange/red powder slightly soluble in water and alcohol. It is widely used ...

dye was found to be useful to mark the area of a water landing, and all German aircraft began to carry the dye. Compact inflatable dinghies were developed for all combat aircraft, even single-engine fighters.

Aircraft used

* Arado Ar 196 *Arado Ar 199

The Arado Ar 199 was a floatplane aircraft, built by Arado Flugzeugwerke. It was a low-wing monoplane, designed in 1938 to be launched from a catapult and operated over water. The enclosed cockpit had two side-by-side seats for instructor and st ...

* Breguet Br.521 ''Bizerte''

* Cant Z.506

The CANT Z.506 ''Airone'' ( Italian: Heron) was a trimotor floatplane produced by CANT from 1935. It served as a transport and postal aircraft with the Italian airline "Ala Littoria". It established 10 world records in 1936 and another 10 in 193 ...

* Dornier Do 18

The Dornier Do 18 was a development of the Do 16 flying boat. It was developed for the ''Luftwaffe'', but ''Luft Hansa'' received five aircraft and used these for tests between the Azores and the North American continent in 1936 and on their ma ...

* Dornier Do 24

* Focke-Wulf Fw 58

The Focke-Wulf Fw 58 ''Weihe'' ( Harrier) was a German aircraft, built to fill a request by the ''Luftwaffe'' for a multi-role aircraft, to be used as an advanced trainer for pilots, gunners and radio operators.

Design and development

The Fw ...

* Focke-Wulf Fw 190

The Focke-Wulf Fw 190, nicknamed ''Würger'' (" Shrike") is a German single-seat, single-engine fighter aircraft designed by Kurt Tank at Focke-Wulf in the late 1930s and widely used during World War II. Along with its well-known counterpart, ...

* Heinkel He 59

* Heinkel He 60

* Heinkel He 114

* Heinkel He 115

* Junkers Ju 52

The Junkers Ju 52/3m (nicknamed ''Tante Ju'' ("Aunt Ju") and ''Iron Annie'') is a transport aircraft that was designed and manufactured by German aviation company Junkers.

Development of the Ju 52 commenced during 1930, headed by German aero ...

Dornier Do-24"Seenotgruppe."

/ref> *

Junkers W 34

The Junkers W 34 was a German-built, single-engine, passenger and transport aircraft. Developed in the 1920s, it was taken into service in 1926. The passenger version could take a pilot and five passengers. The aircraft was developed from the J ...

Dornier Do-24"Seenotflug-Kommando 1."

/ref>

See also

*Combat search and rescue

Combat search and rescue (CSAR) are search and rescue operations that are carried out during war that are within or near combat zones.

A CSAR mission may be carried out by a task force of helicopters, ground-attack aircraft, aerial refueling ...

(the modern term for operations of this type)

References

;Notes ;Bibliography * Born, Karl. ''Rettung zwischen den Fronten: Seenotdienst der deutschen Luftwaffe 1939–1945''. Mittler, 1996. * Boyne, Walter J. ''Beyond the Wild Blue: A History of the U.S. Air Force, 1947–1997''. Macmillan, 1998. * Dierich, Wolfgang, editor. Stiftung Luftwaffenehrenmal e.V. ''Die Verbände der Luftwaffe: 1935–1945: Gliederungen u. Kurzchroniken: Eine Dokumentation''. Motorbuch-Verlag, 1976. * Evans, Clayton. ''Rescue at sea: an international history of lifesaving, coastal rescue craft and organisations''. Naval Institute Press, 2003. * Nicolaou, Stéphane. ''Flying boats & seaplanes: a history from 1905''. Zenith Imprint, 1998. * Nielsen, Andreas. ''The German Air Force General Staff''. Issue 173 of USAF historical studies. Ayer Publishing, 1968. * Thurling, Horst. ''Die 7. Seenotstaffel: 1941–1944''. Horst Thurling, 1997. * Tilford, Earl H., Jr., Captain, USAF"Seenotdienst: Early Development of Air-Sea Rescue"

''Air University Review'', January–February 1977 * Tilford, Earl H., Jr. ''Search and rescue in Southeast Asia'', pp. 4–8. Center for Air Force History. DIANE Publishing, 1992. * Wadman, David; Adam Thompson. (2009) ''Seeflieger: Luftwaffe Maritime Aircraft and Units, 1935–1945''. Classic Publications. {{refend Luftwaffe Rescue aviation units and formations