Second European colonization wave (19th century–20th century) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of

During this period, between the 1815

During this period, between the 1815

The

The

In Britain, the age of new imperialism marked a time for significant economic changes. Because the country was the first to industrialize, Britain was technologically ahead of many other countries throughout the majority of the nineteenth century.Lambert, Tim. "England in the 19th Century." Localhistories.org. 2008. 24 March 2015

In Britain, the age of new imperialism marked a time for significant economic changes. Because the country was the first to industrialize, Britain was technologically ahead of many other countries throughout the majority of the nineteenth century.Lambert, Tim. "England in the 19th Century." Localhistories.org. 2008. 24 March 2015

/ref> By the end of the nineteenth century, however, other countries, chiefly Germany and the United States, began to challenge Britain's technological and economic power. After several decades of monopoly, the country was battling to maintain a dominant economic position while other powers became more involved in international markets. In 1870, Britain contained 31.8% of the world's manufacturing capacity while the United States contained 23.3% and Germany contained 13.2%.Platt, D.C.M. "Economic Factors in British Policy during the 'New Imperialism.'" ''Past and Present'', Vol. 39, (April 1968). pp.120–138. jstor.org. 23 March 2015

/ref> By 1910, Britain's manufacturing capacity had dropped to 14.7%, while that of the United States had risen to 35.3% and that of Germany to 15.9%. As countries like Germany and America became more economically successful, they began to become more involved with imperialism, resulting in the British struggling to maintain the volume of British trade and investment overseas. Britain further faced strained international relations with three expansionist powers (Japan, Germany, and Italy) during the early twentieth century. Before 1939, these three powers never directly threatened Britain itself, but the dangers to the Empire were clear.Davis, John. ''A History of Britain, 1885–1939''. MacMillan Press, 1999. Print. By the 1930s, Britain was worried that Japan would threaten its holdings in the Far East as well as territories in India, Australia and New Zealand. Italy held an interest in North Africa, which threatened British Egypt, and German dominance of the European continent held some danger for Britain's security. Britain worried that the expansionist powers would cause the breakdown of international stability; as such, British foreign policy attempted to protect the stability in a rapidly changing world. With its stability and holdings threatened, Britain decided to adopt a policy of concession rather than resistance, a policy that became known as appeasement. In Britain, the era of new imperialism affected public attitudes toward the idea of imperialism itself. Most of the public believed that if imperialism was going to exist, it was best if Britain was the driving force behind it.Ward, Paul. ''Britishness Since 1870''. Routledge, 2004. Print. The same people further thought that British imperialism was a force for good in the world. In 1940, the Fabian Colonial Research Bureau argued that Africa could be developed both economically and socially, but until this development could happen, Africa was best off remaining with the

/ref> Many of Europe's major elites also found advantages in formal, overseas expansion: large financial and industrial monopolies wanted imperial support to protect their overseas investments against competition and domestic political tensions abroad, bureaucrats sought government offices, military officers desired promotion, and the traditional but waning landed gentries sought increased profits for their investments, formal titles, and high office. Such special interests have perpetuated empire building throughout history.

Observing the rise of trade unionism, socialism, and other protest movements during an era of mass society both in Europe and later in North America, elites sought to use imperial jingoism to co-opt the support of part of the industrial working class. The new mass media promoted jingoism in the

Many of Europe's major elites also found advantages in formal, overseas expansion: large financial and industrial monopolies wanted imperial support to protect their overseas investments against competition and domestic political tensions abroad, bureaucrats sought government offices, military officers desired promotion, and the traditional but waning landed gentries sought increased profits for their investments, formal titles, and high office. Such special interests have perpetuated empire building throughout history.

Observing the rise of trade unionism, socialism, and other protest movements during an era of mass society both in Europe and later in North America, elites sought to use imperial jingoism to co-opt the support of part of the industrial working class. The new mass media promoted jingoism in the

In the 17th century, the British businessmen arrived in India and, after taking a small portion of land, formed the

In the 17th century, the British businessmen arrived in India and, after taking a small portion of land, formed the

In 1839, China found itself fighting the First Opium War with Great Britain after the Governor-General of

In 1839, China found itself fighting the First Opium War with Great Britain after the Governor-General of

"The Great Game" (Also called the ''Tournament of Shadows'' (, ''Turniry Teney'') in Russia) was the strategic, economic and political rivalry, emanating to

"The Great Game" (Also called the ''Tournament of Shadows'' (, ''Turniry Teney'') in Russia) was the strategic, economic and political rivalry, emanating to

France gained a leading position as an imperial power in the Pacific after making

France gained a leading position as an imperial power in the Pacific after making

The Dutch Ethical Policy was the dominant reformist and liberal political character of colonial policy in the Dutch East Indies during the 20th century. In 1901, the Dutch

The Dutch Ethical Policy was the dominant reformist and liberal political character of colonial policy in the Dutch East Indies during the 20th century. In 1901, the Dutch

full text

* * Baumgart, W. ''Imperialism: The Idea and Reality of British and French Colonial Expansion 1880-1914'' (1982) * Betts, Raymond F. ''Europe Overseas: Phases of Imperialism'' (1968) 206pp; basic survey * Cady, John Frank. ''The Roots of French Imperialism in Eastern Asia'' (1967) * Cain, Peter J., and Anthony G. Hopkins. "Gentlemanly capitalism and British expansion overseas II: new imperialism, 1850‐1945." ''The Economic History Review'' 40.1 (1987): 1–26. * * * * Hinsley, F.H., ed. ''The New Cambridge Modern History, vol. 11, Material Progress and World-Wide Problems 1870-1898'' (1979) * Hodge, Carl Cavanagh. ''Encyclopedia of the Age of Imperialism, 1800–1914'' (2 vol., 2007); online * Langer, William. ''An Encyclopedia of World History'' (5th ed. 1973); highly detailed outline of events

1948 edition online

* Langer, William. ''The Diplomacy of Imperialism 1890-1902'' (1950); advanced comprehensive history

online copy free to borrow

also se

* Manning, Patrick. ''Francophone Sub-Saharan Africa, 1880–1995'' (1998

online

* Moon, Parker T. ''Imperialism & World Politics'' (1926), Comprehensive coverage; online * Mowat, C. L., ed. ''The New Cambridge Modern History, Vol. 12: The Shifting Balance of World Forces, 1898–1945'' (1968); online * Page, Melvin E. et al. eds. ''Colonialism: An International Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia'' (2 vol 2003) * Pakenham, Thomas. ''The Scramble for Africa: White Man's Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876-1912'' (1992) * * Stuchtey, Benedikt, ed

''Colonialism and Imperialism, 1450–1950''

J.A. Hobson's Imperialism: A Study: A Centennial Retrospective by Professor Peter CainExtensive information on the British Empire

by

The Martian Chronicles: History Behind the Chronicles New Imperialism 1870–1914

*1- Coyne, Christopher J. and Steve Davies. "Empire: Public Goods and Bads" (Jan 2007)

Wayback Machine

– Fordham University

(a course syllabus)

*2- Coyne, Christopher J. and Steve Davies. "Empire: Public Goods and Bads" (Jan 2007)

Wayback Machine

{{Economy of the United Kingdom 19th century European colonisation in Africa

colonial expansion

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 au ...

by European powers, the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, and Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Com

The period featured an unprecedented pursuit of overseas territorial acquisitions. At the time, states focused on building their empires with new technological advances and developments, expanding their territory through conquest, and exploiting the resources of the subjugated countries.

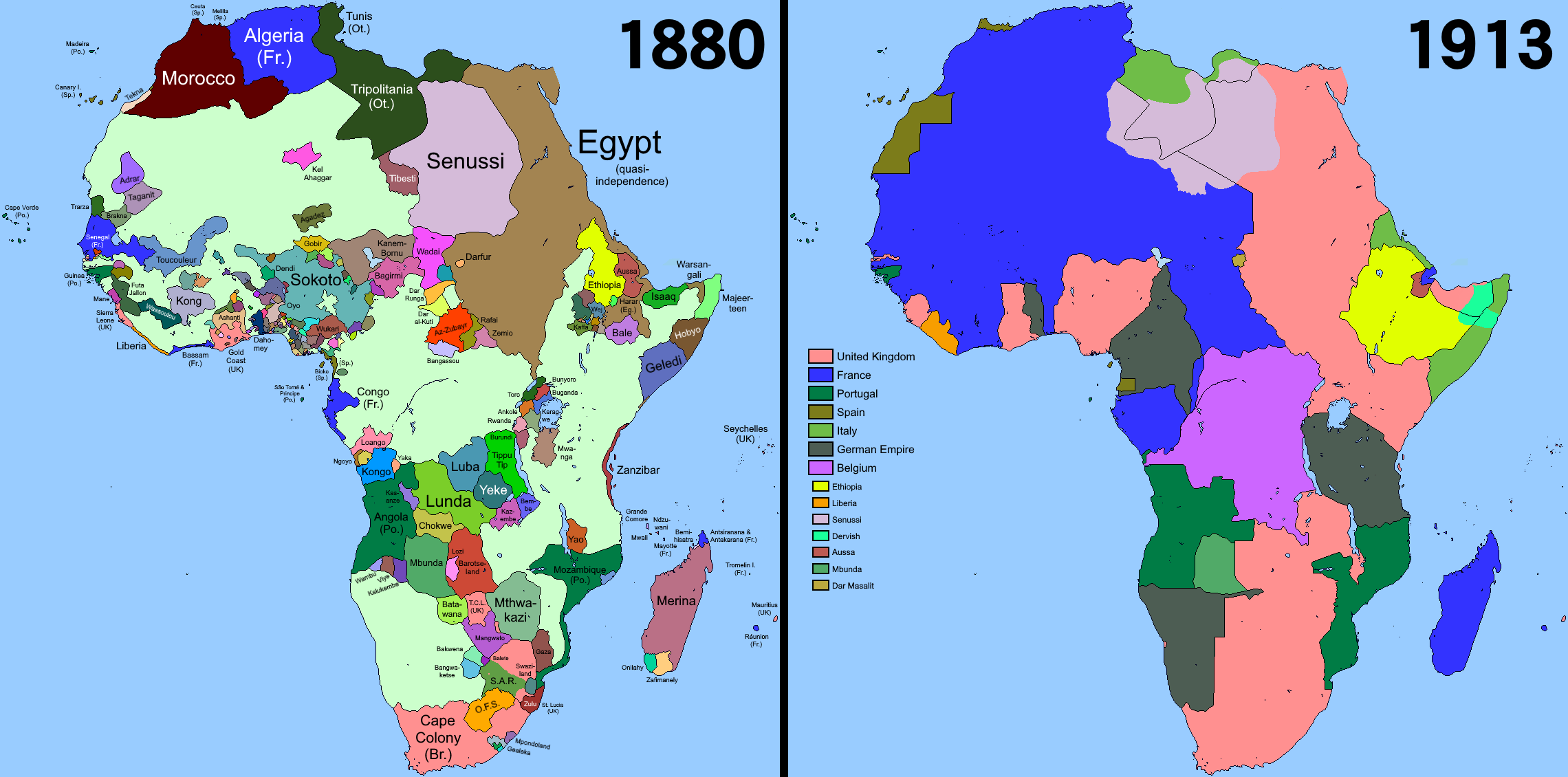

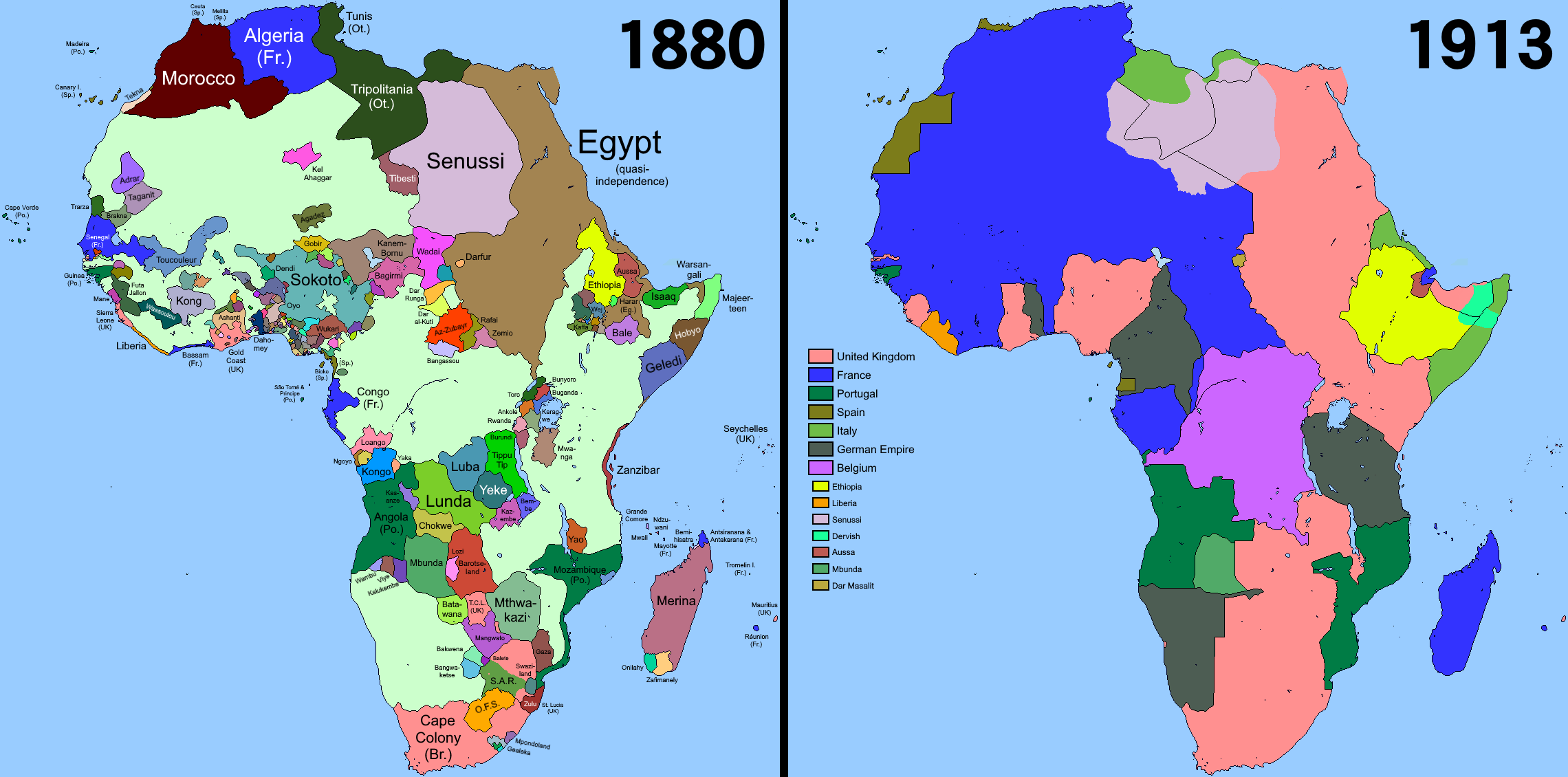

During the era of New Imperialism, the Western powers (and Japan) individually conquered almost all of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

and parts of Asia. The new wave of imperialism reflected ongoing rivalries among the great powers, the economic desire for new resources and markets, and a "civilizing mission

The civilizing mission ( es, misión civilizadora; pt, Missão civilizadora; french: Mission civilisatrice) is a political rationale for military intervention and for colonization purporting to facilitate the Westernization of indigenous pe ...

" ethos. Many of the colonies established during this era gained independence during the era of decolonization

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on separatism, in ...

that followed World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

.

The qualifier "new" is used to differentiate modern imperialism from earlier imperial activity, such as the formation of ancient empires and the first wave of European colonization

The first European colonialism, European colonization wave began with Castilians, Castilian and Portuguese Empire, Portuguese conquests and explorations, and primarily involved the European colonization of the Americas, though it also included t ...

.

Rise

TheAmerican Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

(1775–83) and the collapse of the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

in Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

in the 1820s ended the first era of European imperialism. Especially in Great Britain these revolutions helped show the deficiencies of mercantilism, the doctrine of economic competition for finite wealth which had supported earlier imperial expansion. In 1846, the Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. They wer ...

were repealed and manufacturers grew, as the regulations enforced by the Corn Laws had slowed their businesses. With the repeal in place, the manufacturers were able to trade more freely. Thus, Britain began to adopt the concept of free trade.

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

after the defeat of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

ic France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

and Imperial Germany's victory in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, Great Britain reaped the benefits of being Europe's dominant military and economic power. As the "workshop of the world", Britain could produce finished goods so efficiently that they could usually undersell comparable, locally manufactured goods in foreign markets, supplying a large share of the manufactured goods consumed by such nations as the German states, France, Belgium, and the United States.

The erosion of British hegemony after the Franco-Prussian War, in which a coalition of German states led by Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

soundly defeated the Second French Empire

The Second French Empire (; officially the French Empire, ), was the 18-year Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 14 January 1852 to 27 October 1870, between the Second and the Third Republic of France.

Historians in the 1930 ...

, was occasioned by changes in the European and world economies and in the continental balance of power following the breakdown of the Concert of Europe

The Concert of Europe was a general consensus among the Great Powers of 19th-century Europe to maintain the European balance of power, political boundaries, and spheres of influence. Never a perfect unity and subject to disputes and jockeying ...

, established by the Congress of Vienna. The establishment of nation-states in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

resolved territorial issues that had kept potential rivals embroiled in internal affairs at the heart of Europe to Britain's advantage. The years from 1871 to 1914 would be marked by an extremely unstable peace. France's determination to recover Alsace-Lorraine, annexed by Germany as a result of the Franco-Prussian War, and Germany's mounting imperialist ambitions would keep the two nations constantly poised for conflict.

This competition was sharpened by the Long Depression

The Long Depression was a worldwide price and economic recession, beginning in 1873 and running either through March 1879, or 1896, depending on the metrics used. It was most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been experiencing st ...

of 1873–1896, a prolonged period of price deflation punctuated by severe business downturns, which put pressure on governments to promote home industry, leading to the widespread abandonment of free trade among Europe's powers (in Germany from 1879 and in France from 1881).

Berlin Conference

The

The Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, also known as the Congo Conference (, ) or West Africa Conference (, ), regulated European colonisation and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period and coincided with Germany's sudden emergenc ...

of 1884–1885 sought to destroy the competition between the powers by defining "effective occupation" as the criterion for international recognition of a territory claim, specifically in Africa. The imposition of direct rule in terms of "effective occupation" necessitated routine recourse to armed force against indigenous states and peoples. Uprisings against imperial rule were put down ruthlessly, most brutally in the Herero Wars

The Herero Wars were a series of colonial wars between the German Empire and the Herero people of German South West Africa (present-day Namibia). They took place between 1904 and 1908.

Background Pre-colonial South-West Africa

The Hereros we ...

in German South-West Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

from 1904 to 1907 and the Maji Maji Rebellion

The Maji Maji Rebellion (german: Maji-Maji-Aufstand, sw, Vita vya Maji Maji), was an armed rebellion of Islamic and animist Africans against German colonial rule in German East Africa (modern-day Tanzania). The war was triggered by German Colon ...

in German East Africa from 1905 to 1907. One of the goals of the conference was to reach agreements over trade, navigation, and boundaries of Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo ...

. However, of all of the 15 nations in attendance of the Berlin Conference, none of the countries represented were African.

The main dominating powers of the conference were France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

. They remapped Africa without considering the cultural and linguistic borders that were already established. At the end of the conference, Africa was divided into 50 different colonies. The attendants established who was in control of each of these newly divided colonies. They also planned, noncommittally, to end the slave trade in Africa.

Britain during the era

In Britain, the age of new imperialism marked a time for significant economic changes. Because the country was the first to industrialize, Britain was technologically ahead of many other countries throughout the majority of the nineteenth century.Lambert, Tim. "England in the 19th Century." Localhistories.org. 2008. 24 March 2015

In Britain, the age of new imperialism marked a time for significant economic changes. Because the country was the first to industrialize, Britain was technologically ahead of many other countries throughout the majority of the nineteenth century.Lambert, Tim. "England in the 19th Century." Localhistories.org. 2008. 24 March 2015/ref> By the end of the nineteenth century, however, other countries, chiefly Germany and the United States, began to challenge Britain's technological and economic power. After several decades of monopoly, the country was battling to maintain a dominant economic position while other powers became more involved in international markets. In 1870, Britain contained 31.8% of the world's manufacturing capacity while the United States contained 23.3% and Germany contained 13.2%.Platt, D.C.M. "Economic Factors in British Policy during the 'New Imperialism.'" ''Past and Present'', Vol. 39, (April 1968). pp.120–138. jstor.org. 23 March 2015

/ref> By 1910, Britain's manufacturing capacity had dropped to 14.7%, while that of the United States had risen to 35.3% and that of Germany to 15.9%. As countries like Germany and America became more economically successful, they began to become more involved with imperialism, resulting in the British struggling to maintain the volume of British trade and investment overseas. Britain further faced strained international relations with three expansionist powers (Japan, Germany, and Italy) during the early twentieth century. Before 1939, these three powers never directly threatened Britain itself, but the dangers to the Empire were clear.Davis, John. ''A History of Britain, 1885–1939''. MacMillan Press, 1999. Print. By the 1930s, Britain was worried that Japan would threaten its holdings in the Far East as well as territories in India, Australia and New Zealand. Italy held an interest in North Africa, which threatened British Egypt, and German dominance of the European continent held some danger for Britain's security. Britain worried that the expansionist powers would cause the breakdown of international stability; as such, British foreign policy attempted to protect the stability in a rapidly changing world. With its stability and holdings threatened, Britain decided to adopt a policy of concession rather than resistance, a policy that became known as appeasement. In Britain, the era of new imperialism affected public attitudes toward the idea of imperialism itself. Most of the public believed that if imperialism was going to exist, it was best if Britain was the driving force behind it.Ward, Paul. ''Britishness Since 1870''. Routledge, 2004. Print. The same people further thought that British imperialism was a force for good in the world. In 1940, the Fabian Colonial Research Bureau argued that Africa could be developed both economically and socially, but until this development could happen, Africa was best off remaining with the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

. Rudyard Kipling's 1891 poem, "The English Flag," contains the stanza:

These lines show Kipling's belief that the British who actively took part in imperialism knew more about British national identity than the ones whose entire lives were spent solely in the imperial metropolis. While there were pockets of anti-imperialist opposition in Britain in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, resistance to imperialism was nearly nonexistent in the country as a whole. In many ways, this new form of imperialism formed a part of the British identity until the end of the era of new imperialism with the Second World War.Winds of the World, give answer! They are whimpering to and fro-- And what should they know of England who only England know?-- The poor little street-bred people that vapour and fume and brag, They are lifting their heads in the stillness to yelp at the English Flag!

Social implications

New Imperialism gave rise to new social views of colonialism.Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British India, which inspired much of his work.

...

, for instance, urged the United States to "Take up the White Man's burden" of bringing European civilization to the other peoples of the world, regardless of whether these "other peoples" wanted this civilization or not. This part of ''The White Man's Burden'' exemplifies Britain's perceived attitude towards the colonization of other countries:

While Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in We ...

became popular throughout Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, the paternalistic French and Portuguese "civilizing mission

The civilizing mission ( es, misión civilizadora; pt, Missão civilizadora; french: Mission civilisatrice) is a political rationale for military intervention and for colonization purporting to facilitate the Westernization of indigenous pe ...

" (in French: '; in Portuguese: ') appealed to many European statesmen both in and outside France. Despite apparent benevolence existing in the notion of the "White Man's Burden", the unintended consequences of imperialism might have greatly outweighed the potential benefits. Governments became increasingly paternalistic at home and neglected the individual liberties of their citizens. Military spending expanded, usually leading to an " imperial overreach", and imperialism created clients of ruling elites abroad that were brutal and corrupt, consolidating power through imperial rents and impeding social change and economic development that ran against their ambitions. Furthermore, "nation building" oftentimes created cultural sentiments of racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonis ...

and xenophobia

Xenophobia () is the fear or dislike of anything which is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression of perceived conflict between an in-group and out-group and may manifest in suspicion by the one of the other's activities, a ...

.Coyne, Christopher J. and Steve Davies. "Empire: Public Goods and Bads" (Jan 2007)/ref>

Many of Europe's major elites also found advantages in formal, overseas expansion: large financial and industrial monopolies wanted imperial support to protect their overseas investments against competition and domestic political tensions abroad, bureaucrats sought government offices, military officers desired promotion, and the traditional but waning landed gentries sought increased profits for their investments, formal titles, and high office. Such special interests have perpetuated empire building throughout history.

Observing the rise of trade unionism, socialism, and other protest movements during an era of mass society both in Europe and later in North America, elites sought to use imperial jingoism to co-opt the support of part of the industrial working class. The new mass media promoted jingoism in the

Many of Europe's major elites also found advantages in formal, overseas expansion: large financial and industrial monopolies wanted imperial support to protect their overseas investments against competition and domestic political tensions abroad, bureaucrats sought government offices, military officers desired promotion, and the traditional but waning landed gentries sought increased profits for their investments, formal titles, and high office. Such special interests have perpetuated empire building throughout history.

Observing the rise of trade unionism, socialism, and other protest movements during an era of mass society both in Europe and later in North America, elites sought to use imperial jingoism to co-opt the support of part of the industrial working class. The new mass media promoted jingoism in the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

(1898), the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the South ...

(1899–1902), and the Boxer Rebellion (1900). The left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

German historian Hans-Ulrich Wehler

Hans-Ulrich Wehler (September 11, 1931 – July 5, 2014) was a German left-liberal historian known for his role in promoting social history through the " Bielefeld School", and for his critical studies of 19th-century Germany.

Life

Wehler was bo ...

has defined social imperialism

As a political term, social imperialism is the political ideology of people, parties, or nations that are, according to Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin, "socialist in words, imperialist in deeds". In academic use, it refers to governments that enga ...

as "the diversions outwards of internal tensions and forces of change in order to preserve the social and political status quo", and as a "defensive ideology" to counter the "disruptive effects of industrialization on the social and economic structure of Germany". In Wehler's opinion, social imperialism was a device that allowed the German government to distract public attention from domestic problems and preserve the existing social and political order. The dominant elites used social imperialism as the glue to hold together a fractured society and to maintain popular support for the social ''status quo''. According to Wehler, German colonial policy in the 1880s was the first example of social imperialism in action, and was followed up by the 1897 Tirpitz Plan for expanding the German Navy. In this point of view, groups such as the Colonial Society and the Navy League are seen as instruments for the government to mobilize public support. The demands for annexing most of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

and Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

are seen by Wehler as the pinnacle of social imperialism.Eley, Geoff "Social Imperialism" pages 925–926 from ''Modern Germany'' Volume 2, New York, Garland Publishing, 1998 page 925.

The notion of rule over foreign lands commanded widespread acceptance among metropolitan populations, even among those who associated imperial colonization with oppression and exploitation. For example, the 1904 Congress of the Socialist International

The Socialist International (SI) is a political international or worldwide organisation of political parties which seek to establish democratic socialism. It consists mostly of socialist and labour-oriented political parties and organisations ...

concluded that the colonial peoples should be taken in hand by future European socialist governments and led by them into eventual independence.

South Asia

India

In the 17th century, the British businessmen arrived in India and, after taking a small portion of land, formed the

In the 17th century, the British businessmen arrived in India and, after taking a small portion of land, formed the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

. The British East India Company annexed most of the subcontinent of India, starting with Bengal in 1757 and ending with Punjab in 1849. Many princely states remained independent. This was aided by a power vacuum

In political science and political history, the term power vacuum, also known as a power void, is an analogy between a physical vacuum to the political condition "when someone in a place of power, has lost control of something and no one has repla ...

formed by the collapse of the Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was an early-modern empire that controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries. Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the d ...

in India and the death of Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb and increased British forces in India because of colonial conflicts with France. The invention of clipper ships

A clipper was a type of mid-19th-century merchant sailing vessel, designed for speed. Clippers were generally narrow for their length, small by later 19th century standards, could carry limited bulk freight, and had a large total sail area. "Cl ...

in the early 1800s cut the trip to India from Europe in half from 6 months to 3 months; the British also laid cables on the floor of the ocean allowing telegrams to be sent from India and China. In 1818, the British controlled most of the Indian subcontinent and began imposing their ideas and ways on its residents, including different succession laws that allowed the British to take over a state with no successor and gain its land and armies, new taxes, and monopolistic control of industry. The British also collaborated with Indian officials to increase their influence in the region.

Some Hindu and Muslim sepoys rebelled in 1857, resulting in the Indian Rebellion

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against Company rule in India, the rule of the East India Company, British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the The Crown, British ...

. After this revolt was suppressed by the British, India came under the direct control of the British crown. After the British had gained more control over India, they began changing around the financial state of India. Previously, Europe had to pay for Indian textiles and spices in bullion; with political control, Britain directed farmers to grow cash crops for the company for exports to Europe while India became a market for textiles from Britain. In addition, the British collected huge revenues from land rent and taxes on its acquired monopoly on salt production. Indian weavers were replaced by new spinning and weaving machines and Indian food crops were replaced by cash crops like cotton and tea.

The British also began connecting Indian cities by railroad and telegraph to make travel and communication easier as well as building an irrigation system for increasing agricultural production. When Western education was introduced in India, Indians were quite influenced by it, but the inequalities between the British ideals of governance and their treatment of Indians became clear. In response to this discriminatory treatment, a group of educated Indians established the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British E ...

, demanding equal treatment and self-governance.

John Robert Seeley

Sir John Robert Seeley, KCMG (10 September 1834 – 13 January 1895) was an English Liberal historian and political essayist. A founder of British imperial history, he was a prominent advocate for the British Empire, promoting a concept of Grea ...

, a Cambridge Professor of History, said, "Our acquisition of India was made blindly. Nothing great that has ever been done by Englishmen was done so unintentionally or accidentally as the conquest of India". According to him, the political control of India was not a conquest in the usual sense because it was not an act of a state.

The new administrative arrangement, crowned with Queen Victoria's proclamation as Empress of India

Emperor or Empress of India was a title used by British monarchs from 1 May 1876 (with the Royal Titles Act 1876) to 22 June 1948, that was used to signify their rule over British India, as its imperial head of state. Royal Proclamation of 2 ...

in 1876, effectively replaced the rule of a monopolistic enterprise with that of a trained civil service headed by graduates of Britain's top universities. The administration retained and increased the monopolies held by the company. The India Salt Act of 1882 included regulations enforcing a government monopoly on the collection and manufacture of salt; in 1923 a bill was passed doubling the salt tax.

Southeast Asia

After taking control of much of India, the British expanded further intoBurma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

, Malaya, Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

and Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and ea ...

, with these colonies becoming further sources of trade and raw materials for British goods. The United States laid claim to the Philippines, and after the Philippine–American War, took control of the country as one of its overseas possessions.

Indonesia

Formal colonization of the Dutch East Indies (nowIndonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

) commenced at the dawn of the 19th century when the Dutch state took possession of all Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

(VOC) assets. Before that time the VOC merchants were in principle just another trading power among many, establishing trading posts and settlements (colonies) in strategic places around the archipelago. The Dutch gradually extended their sovereignty over most of the islands in the East Indies. Dutch expansion paused for several years during an interregnum of British rule between 1806 and 1816, when the Dutch Republic was occupied by the French forces of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

. The Dutch government-in-exile in England ceded rule of all its colonies to Great Britain. However, Jan Willem Janssens, the Governor of the Dutch East Indies at the time, fought the British before surrendering the colony; he was eventually replaced by Stamford Raffles

Sir Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles (5 July 1781 – 5 July 1826) was a British statesman who served as the Lieutenant-Governor of the Dutch East Indies between 1811 and 1816, and Lieutenant-Governor of Bencoolen between 1818 and 1824. He is ...

.

The Dutch East Indies became the prize possession of the Dutch Empire. It was not the typical settler colony founded through massive emigration from the mother countries (such as the USA or Australia) and hardly involved displacement of the indigenous islanders, with a notable and dramatic exception in the island of Banda during the VOC era. Neither was it a plantation colony built on the import of slaves (such as Haiti or Jamaica) or a pure trade post colony (such as Singapore or Macau). It was more of an expansion of the existing chain of VOC trading posts. Instead of mass emigration from the homeland, the sizeable indigenous populations were controlled through effective political manipulation supported by military force. The servitude of the indigenous masses was enabled through a structure of indirect governance, keeping existing indigenous rulers in place. This strategy was already established by the VOC, which independently acted as a semi-sovereign state within the Dutch state, using the Indo Eurasian population as an intermediary buffer.

In 1869 British anthropologist Alfred Russel Wallace described the colonial governing structure in his book "The Malay Archipelago

''The Malay Archipelago'' is a book by the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace which chronicles his scientific exploration, during the eight-year period 1854 to 1862, of the southern portion of the Malay Archipelago including Malaysia, S ...

":

"The mode of government now adopted in Java is to retain the whole series of native rulers, from the village chief up to princes, who, under the name of Regents, are the heads of districts about the size of a small English county. With each Regent is placed a Dutch Resident, or Assistant Resident, who is considered to be his "elder brother," and whose "orders" take the form of "recommendations," which are, however, implicitly obeyed. Along with each Assistant, Resident is a Controller, a kind of inspector of all the lower native rulers, who periodically visits every village in the district, examines the proceedings of the native courts, hears complaints against the head-men or other native chiefs, and superintends the Government plantations."

Indochina

France annexed all ofVietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

and Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailan ...

in the 1880s; in the following decade, France completed its Indochinese

Mainland Southeast Asia, also known as the Indochinese Peninsula or Indochina, is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the west an ...

empire with the annexation of Laos, leaving the kingdom of Siam (now Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

) with an uneasy independence as a neutral buffer between British and French-ruled lands.

East Asia

China

In 1839, China found itself fighting the First Opium War with Great Britain after the Governor-General of

In 1839, China found itself fighting the First Opium War with Great Britain after the Governor-General of Hunan

Hunan (, ; ) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the South Central China region. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangxi ...

and Hubei

Hubei (; ; alternately Hupeh) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, and is part of the Central China region. The name of the province means "north of the lake", referring to its position north of Dongting Lake. The ...

, Lin Zexu

Lin Zexu (30 August 1785 – 22 November 1850), courtesy name Yuanfu, was a Chinese political philosopher and politician. He was the head of states (Viceroy), Governor General, scholar-official, and under the Daoguang Emperor of the Qing dynas ...

, seized the illegally traded opium. China was defeated, and in 1842 agreed to the provisions of the Treaty of Nanking

The Treaty of Nanjing was the peace treaty which ended the First Opium War (1839–1842) between Great Britain and the Qing dynasty of China on 29 August 1842. It was the first of what the Chinese later termed the Unequal Treaties.

In the ...

. Hong Kong Island was ceded to Britain, and certain ports, including Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowin ...

and Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the capital and largest city of Guangdong province in southern China. Located on the Pearl River about north-northwest of Hong Kon ...

, were opened to British trade and residence. In 1856, the Second Opium War broke out; the Chinese were again defeated and forced to the terms of the 1858 Treaty of Tientsin

The Treaty of Tientsin, also known as the Treaty of Tianjin, is a collective name for several documents signed at Tianjin (then romanized as Tientsin) in June 1858. The Qing dynasty, Russian Empire, Second French Empire, United Kingdom, and t ...

and the 1860 Convention of Peking

The Convention of Peking or First Convention of Peking is an agreement comprising three distinct treaties concluded between the Qing dynasty of China and Great Britain, France, and the Russian Empire in 1860. In China, they are regarded as amon ...

. The treaty opened new ports to trade and allowed foreigners to travel in the interior. Missionaries gained the right to propagate Christianity, another means of Western penetration. The United States and Russia obtained the same prerogatives in separate treaties

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

.

Towards the end of the 19th century, China appeared on the way to territorial dismemberment and economic vassalage, the fate of India's rulers that had played out much earlier. Several provisions of these treaties caused long-standing bitterness and humiliation among the Chinese: extraterritoriality

In international law, extraterritoriality is the state of being exempted from the jurisdiction of local law, usually as the result of diplomatic negotiations.

Historically, this primarily applied to individuals, as jurisdiction was usually cl ...

(meaning that in a dispute with a Chinese person, a Westerner had the right to be tried in a court under the laws of his own country), customs regulation, and the right to station foreign warships in Chinese waters.

In 1904, the British invaded Lhasa, a pre-emptive strike against Russian intrigues and secret meetings between the 13th Dalai Lama's envoy and Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Polan ...

. The Dalai Lama fled into exile to China and Mongolia. The British were greatly concerned at the prospect of a Russian invasion of the Crown colony of India, though Russia – badly defeated by Japan in the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

and weakened by internal rebellion – could not realistically afford a military conflict against Britain. China under the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-spea ...

, however, was another matter.

Natural disasters, famine and internal rebellions had enfeebled China in the late Qing. In the late 19th century, Japan and the Great Powers easily carved out trade and territorial concessions. These were humiliating submissions for the once-powerful China. Still, the central lesson of the war with Japan was not lost on the Russian General Staff: an Asian country using Western technology and industrial production methods could defeat a great European power. Jane E. Elliott criticized the allegation that China refused to modernize or was unable to defeat Western armies as simplistic, noting that China embarked on a massive military modernization in the late 1800s after several defeats, buying weapons from Western countries and manufacturing their own at arsenals, such as the Hanyang Arsenal

Hanyang Arsenal () was one of the largest and oldest modern arsenals in Chinese history.

History

Originally known as the ''Hubei Arsenal'', it was founded in 1891 by Qing official Zhang Zhidong, who diverted funds from the Nanyang Fleet in Gua ...

during the Boxer Rebellion. In addition, Elliott questioned the claim that Chinese society was traumatized by the Western victories, as many Chinese peasants (90% of the population at that time) living outside the concessions continued about their daily lives, uninterrupted and without any feeling of "humiliation".

The British observer Demetrius Charles de Kavanagh Boulger suggested a British-Chinese alliance to check Russian expansion in Central Asia.

During the Ili crisis when Qing China threatened to go to war against Russia over the Russian occupation of Ili, the British officer Charles George Gordon

Major-General Charles George Gordon CB (28 January 1833 – 26 January 1885), also known as Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, and Gordon of Khartoum, was a British Army officer and administrator. He saw action in the Crimean War as an officer in ...

was sent to China by Britain to advise China on military options against Russia should a potential war break out between China and Russia.

The Russians observed the Chinese building up their arsenal of modern weapons during the Ili crisis, the Chinese bought thousands of rifles from Germany. In 1880 massive amounts of military equipment and rifles were shipped via boats to China from Antwerp as China purchased torpedoes, artillery, and 260,260 modern rifles from Europe.

The Russian military observer D. V. Putiatia visited China in 1888 and found that in Northeastern China (Manchuria) along the Chinese-Russian border, the Chinese soldiers were potentially able to become adept at "European tactics" under certain circumstances, and the Chinese soldiers were armed with modern weapons like Krupp artillery, Winchester carbines, and Mauser rifles.

Compared to Russian controlled areas, more benefits were given to the Muslim Kirghiz on the Chinese controlled areas. Russian settlers fought against the Muslim nomadic Kirghiz, which led the Russians to believe that the Kirghiz would be a liability in any conflict against China. The Muslim Kirghiz were sure that in an upcoming war, that China would defeat Russia.

The Qing dynasty forced Russia to hand over disputed territory in Ili in the Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1881)

The Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1881) (), also known as Treaty of Ili (), was a treaty between the Russian Empire and the Qing dynasty that was signed in Saint Petersburg, Russia, on . It provided for the return to China of the eastern part of th ...

, in what was widely seen by the west as a diplomatic victory for the Qing. Russia acknowledged that Qing China potentially posed a serious military threat. Mass media in the west during this era portrayed China as a rising military power due to its modernization programs and as major threat to the western world, invoking fears that China would successfully conquer western colonies like Australia.

Russian sinologists, the Russian media, threat of internal rebellion, the pariah status inflicted by the Congress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878) was a diplomatic conference to reorganise the states in the Balkan Peninsula after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, which had been won by Russia against the Ottoman Empire. Represented at th ...

, and the negative state of the Russian economy all led Russia to concede and negotiate with China in St Petersburg, and return most of Ili to China.

Historians have judged the Qing dynasty's vulnerability and weakness to foreign imperialism in the 19th century to be based mainly on its maritime naval weakness while it achieved military success against westerners on land, the historian Edward L. Dreyer said that "China’s nineteenth-century humiliations were strongly related to her weakness and failure at sea. At the start of the Opium War, China had no unified navy and no sense of how vulnerable she was to attack from the sea; British forces sailed and steamed wherever they wanted to go. ... In the Arrow War

The Second Opium War (), also known as the Second Anglo-Sino War, the Second China War, the Arrow War, or the Anglo-French expedition to China, was a colonial war lasting from 1856 to 1860, which pitted the British Empire and the French Emp ...

(1856–60), the Chinese had no way to prevent the Anglo-French expedition of 1860 from sailing into the Gulf of Zhili

The Bohai Sea () is a marginal sea approximately in area on the east coast of Mainland China. It is the northwestern and innermost extension of the Yellow Sea, to which it connects to the east via the Bohai Strait. It has a mean depth of a ...

and landing as near as possible to Beijing. Meanwhile, new but not exactly modern Chinese armies suppressed the midcentury rebellions, bluffed Russia into a peaceful settlement of disputed frontiers in Central Asia, and defeated the French forces on land in the Sino-French War (1884–85). But the defeat of the fleet, and the resulting threat to steamship traffic to Taiwan, forced China to conclude peace on unfavorable terms."

The British and Russian consuls schemed and plotted against each other at Kashgar.

In 1906, Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Polan ...

sent a secret agent to China to collect intelligence on the reform and modernization of the Qing dynasty. The task was given to Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim, at the time a colonel in the Russian army, who travelled to China with French Sinologist Paul Pelliot

Paul Eugène Pelliot (28 May 187826 October 1945) was a French Sinologist and Orientalist best known for his explorations of Central Asia and his discovery of many important Chinese texts such as the Dunhuang manuscripts.

Early life and career ...

. Mannerheim was disguised as an ethnographic collector, using a Finnish passport. Finland was, at the time, a Grand Duchy. For two years, Mannerheim proceeded through Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwest ...

, Gansu, Shaanxi

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see § Name) is a landlocked province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichuan (SW), Gansu (W), N ...

, Henan

Henan (; or ; ; alternatively Honan) is a landlocked province of China, in the central part of the country. Henan is often referred to as Zhongyuan or Zhongzhou (), which literally means "central plain" or "midland", although the name is al ...

, Shanxi and Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

to Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

. At the sacred Buddhist mountain of Wutai Shan

Mount Wutai, also known by its Chinese name Wutaishan and as is a sacred Buddhist site at the headwaters of the Qingshui in Shanxi Province, China. Its central area is surrounded by a cluster of flat-topped peaks roughly corresponding to the ...

he even met the 13th Dalai Lama. However, while Mannerheim was in China in 1907, Russia and Britain brokered the Anglo-Russian Agreement, ending the classical period of the Great Game.

The correspondent Douglas Story observed Chinese troops in 1907 and praised their abilities and military skill.

The rise of Japan as an imperial power after the Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

led to further subjugation of China. In a dispute over regional suzerainty, war broke out between China and Japan, resulting in another humiliating defeat for the Chinese. By the Treaty of Shimonoseki

The , also known as the Treaty of Maguan () in China and in the period before and during World War II in Japan, was a treaty signed at the , Shimonoseki, Japan on April 17, 1895, between the Empire of Japan and Qing China, ending the Firs ...

in 1895, China was forced to recognize Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

's exit from the Imperial Chinese tributary system

The tributary system of China (), or Cefeng system () was a network of loose international relations focused on China which facilitated trade and foreign relations by acknowledging China's predominant role in East Asia. It involved multiple relati ...

, leading to the proclamation of the Korean Empire, and the island of Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

was ceded to Japan.

In 1897, taking advantage of the murder of two missionaries, Germany demanded and was given a set of mining and railroad rights around Jiaozhou Bay

The Jiaozhou Bay (; german: Kiautschou Bucht, ) is a bay located in the prefecture-level city of Qingdao (Tsingtau), China.

The bay has historically been romanized as Kiaochow, Kiauchau or Kiao-Chau in English and Kiautschou in German.

Geogra ...

in Shandong province. In 1898, Russia obtained access to Dairen

Dalian () is a major sub-provincial port city in Liaoning province, People's Republic of China, and is Liaoning's second largest city (after the provincial capital Shenyang) and the third-most populous city of Northeast China. Located on the ...

and Port Arthur and the right to build a railroad across Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

, thereby achieving complete domination over a large portion of northeast China. The United Kingdom, France, and Japan also received a number of concessions later that year.

The erosion of Chinese sovereignty contributed to a spectacular anti-foreign outbreak in June 1900, when the " Boxers" (properly the society of the "righteous and harmonious fists") attacked foreign legations in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

. This Boxer Rebellion provoked a rare display of unity among the colonial powers, who formed the Eight-Nation Alliance. Troops landed at Tianjin

Tianjin (; ; Mandarin: ), alternately romanized as Tientsin (), is a municipality and a coastal metropolis in Northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the nine national central cities in Mainland China, with a total popu ...

and marched on the capital, which they took on 14 August; the foreign soldiers then looted and occupied Beijing for several months. German forces were particularly severe in exacting revenge for the killing of their ambassador, while Russia tightened its hold on Manchuria in the northeast until its crushing defeat by Japan in the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

of 1904–1905.

Although extraterritorial jurisdiction was abandoned by the United Kingdom and the United States in 1943, foreign political control of parts of China only finally ended with the incorporation of Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delta i ...

and the small Portuguese territory of Macau

Macau or Macao (; ; ; ), officially the Macao Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (MSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China in the western Pearl River Delta by the South China Sea. With a p ...

into the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

in 1997 and 1999 respectively.

Mainland Chinese historians refer to this period as the century of humiliation.

Central Asia

"The Great Game" (Also called the ''Tournament of Shadows'' (, ''Turniry Teney'') in Russia) was the strategic, economic and political rivalry, emanating to

"The Great Game" (Also called the ''Tournament of Shadows'' (, ''Turniry Teney'') in Russia) was the strategic, economic and political rivalry, emanating to conflict

Conflict may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Films

* ''Conflict'' (1921 film), an American silent film directed by Stuart Paton

* ''Conflict'' (1936 film), an American boxing film starring John Wayne

* ''Conflict'' (1937 film) ...

between the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

and the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

for supremacy in Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

at the expense of Afghanistan, Persia and the Central Asian Khanates/Emirates. The classic Great Game period is generally regarded as running approximately from the Russo-Persian Treaty of 1813 to the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907

The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 (russian: Англо-Русская Конвенция 1907 г., translit=Anglo-Russkaya Konventsiya 1907 g.), or Convention between the United Kingdom and Russia relating to Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet (; ...

, in which nations like Emirate of Bukhara fell. A less intensive phase followed the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, causing some trouble with Persia and Afghanistan until the mid 1920s.

In the post-Second World War post-colonial period, the term has informally continued in its usage to describe the geopolitical machinations of the great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power in ...

s and regional power

In international relations, since the late 20thcentury, the term "regional power" has been used for a sovereign state that exercises significant power within a given geographical region.Joachim Betz, Ian Taylor"The Rise of (New) Regional Pow ...

s as they vie for geopolitical power as well as influence in the area, especially in Afghanistan and Iran/Persia.

Africa

Prelude

Between 1850 and 1914, Britain brought nearly 30% of Africa's population under its control, to 15% for France, 9% for Germany, 7% for Belgium and 1% for Italy:Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

alone contributed 15 million subjects to Britain, more than in the whole of French West Africa, or the entire German colonial empire. The only nations that were not under European control by 1914 were Liberia and Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

.

British colonies

Britain's formal occupation of Egypt in 1882, triggered by concern over the Suez Canal, contributed to a preoccupation over securing control of the Nile River, leading to the conquest of neighboring Sudan in 1896–1898, which in turn led to confrontation with a French military expedition atFashoda

Kodok or Kothok ( ar, كودوك), formerly known as Fashoda, is a town in the north-eastern South Sudanese state of Upper Nile State. Kodok is the capital of Shilluk country, formally known as the Shilluk Kingdom. Shilluk had been an independ ...

in September 1898. In 1899, Britain set out to complete its takeover of the future South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

, which it had begun in 1814 with the annexation of the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with t ...

, by invading the gold-rich Afrikaner republics of Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

and the neighboring Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

. The chartered British South Africa Company had already seized the land to the north, renamed Rhodesia after its head, the Cape tycoon Cecil Rhodes.

British gains in southern and East Africa prompted Rhodes and Alfred Milner

Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner, (23 March 1854 – 13 May 1925) was a British statesman and colonial administrator who played a role in the formulation of British foreign and domestic policy between the mid-1890s and early 1920s. From De ...

, Britain's High Commissioner in South Africa, to urge a "Cape to Cairo" empire: linked by rail, the strategically important Canal would be firmly connected to the mineral-rich South, though Belgian control of the Congo Free State and German control of German East Africa prevented such an outcome until the end of World War I, when Great Britain acquired the latter territory.

Britain's quest for southern Africa and its diamonds led to social complications and fallouts that lasted for years. To work for their prosperous company, British businessmen hired both white and black South Africans. But when it came to jobs, the white South Africans received the higher paid and less dangerous ones, leaving the black South Africans to risk their lives in the mines for limited pay. This process of separating the two groups of South Africans, whites and blacks, was the beginning of segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

between the two that lasted until 1990.

Paradoxically, the United Kingdom, a staunch advocate of free trade, emerged in 1914 with not only the largest overseas empire, thanks to its long-standing presence in India, but also the greatest gains in the conquest of Africa, reflecting its advantageous position at its inception.

Congo Free State

Until 1876, Belgium had no colonial presence in Africa. It was then that its king, Leopold II created the International African Society. Operating under the pretense of an international scientific and philanthropic association, it was actually a private holding company owned by Leopold. Henry Morton Stanley was employed to explore and colonize theCongo River

The Congo River ( kg, Nzâdi Kôngo, french: Fleuve Congo, pt, Rio Congo), formerly also known as the Zaire River, is the second longest river in Africa, shorter only than the Nile, as well as the second largest river in the world by discharge ...

basin area of equatorial Africa in order to capitalize on the plentiful resources such as ivory, rubber, diamonds, and metals. Up until this point, Africa was known as "the Dark Continent" because of the difficulties Europeans had with exploration. Over the next few years, Stanley overpowered and made treaties with over 450 native tribes, acquiring him over of land, nearly 67 times the size of Belgium.

Neither the Belgian government nor the Belgian people had any interest in imperialism at the time, and the land came to be personally owned by King Leopold II. At the Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, also known as the Congo Conference (, ) or West Africa Conference (, ), regulated European colonisation and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period and coincided with Germany's sudden emergenc ...

in 1884, he was allowed to have land named the Congo Free State. The other European countries at the conference allowed this to happen on the conditions that he suppress the East African slave trade, promote humanitarian policies, guarantee free trade, and encourage missions to Christianize the people of the Congo. However, Leopold II's primary focus was to make a large profit on the natural resources, particularly ivory and rubber. In order to make this profit, he passed several cruel decrees that can be considered to be genocide. He forced the natives to supply him with rubber and ivory without any sort of payment in return. Their wives and children were held hostage until the workers returned with enough rubber or ivory to fill their quota, and if they could not, their family would be killed. When villages refused, they were burned down; the children of the village were murdered and the men had their hands cut off. These policies led to uprisings, but they were feeble compared to European military and technological might, and were consequently crushed. The forced labor was opposed in other ways: fleeing into the forests to seek refuge or setting the rubber forests on fire, preventing the Europeans from harvesting the rubber.

No population figures exist from before or after the period, but it is estimated that as many as 10 million people died from violence, famine and disease. However, some sources point to a total population of 16 million people.Michiko Kakutani (30 August 1998). ""King Leopold's Ghost": Genocide With Spin Control". ''The New York Times''

King Leopold II profited from the enterprise with a 700% profit ratio for the rubber he took from Congo and exported. He used propaganda to keep the other European nations at bay, for he broke almost all of the parts of the agreement he made at the Berlin Conference. For example, he had some Congolese pygmies sing and dance at the 1897 World Fair in Belgium, showing how he was supposedly civilizing and educating the natives of the Congo. Under significant international pressure, the Belgian government annexed the territory in 1908 and renamed it the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

, removing it from the personal power of the king. Of all the colonies that were conquered during the wave of New Imperialism, the human rights abuses of the Congo Free State were considered the worst.

Oceania

France gained a leading position as an imperial power in the Pacific after making

France gained a leading position as an imperial power in the Pacific after making Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austra ...

and New Caledonia protectorates in 1842 and 1853 respectively.Bernard Eccleston, Michael Dawson. 1998. ''The Asia-Pacific Profile''. Routledge. p. 250. Tahiti was later annexed entirely into the French colonial empire in 1880, along with the rest of the Society Islands

The Society Islands (french: Îles de la Société, officially ''Archipel de la Société;'' ty, Tōtaiete mā) are an archipelago located in the South Pacific Ocean. Politically, they are part of French Polynesia, an overseas country of the ...

.

The United States made several territorial gains during this period, particularly with the annexation of Hawaii and acquisition of most of Spain's colonial outposts following the 1898 Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence