Science And Invention In Birmingham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Birmingham's reputation for trade and innovation really begins to take off in the 12th century with the expansion of a market held there by the

Birmingham's reputation for trade and innovation really begins to take off in the 12th century with the expansion of a market held there by the  Birmingham's first notable literary figure is John Rogers, the compiler and editor of the 1537 ''

Birmingham's first notable literary figure is John Rogers, the compiler and editor of the 1537 ''

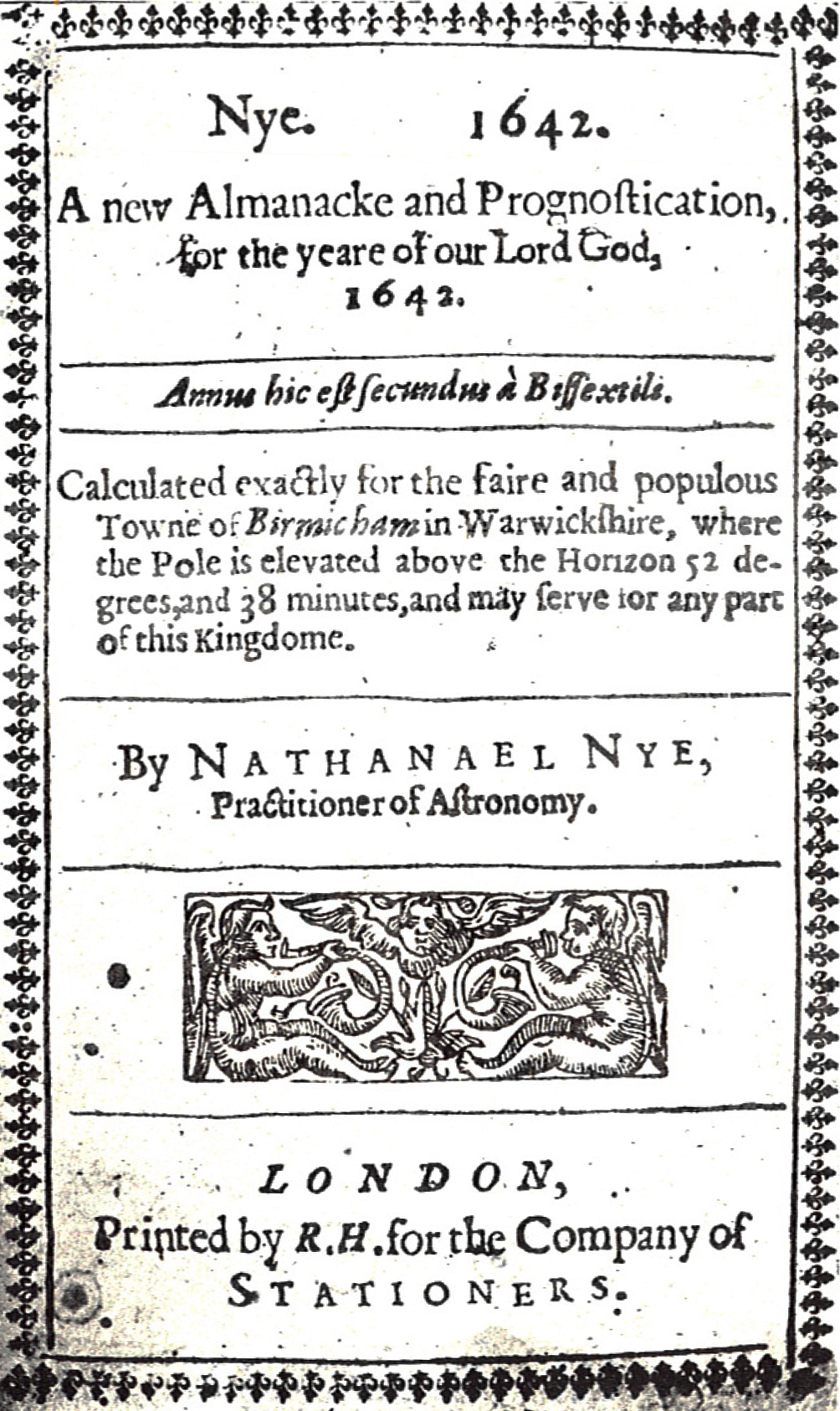

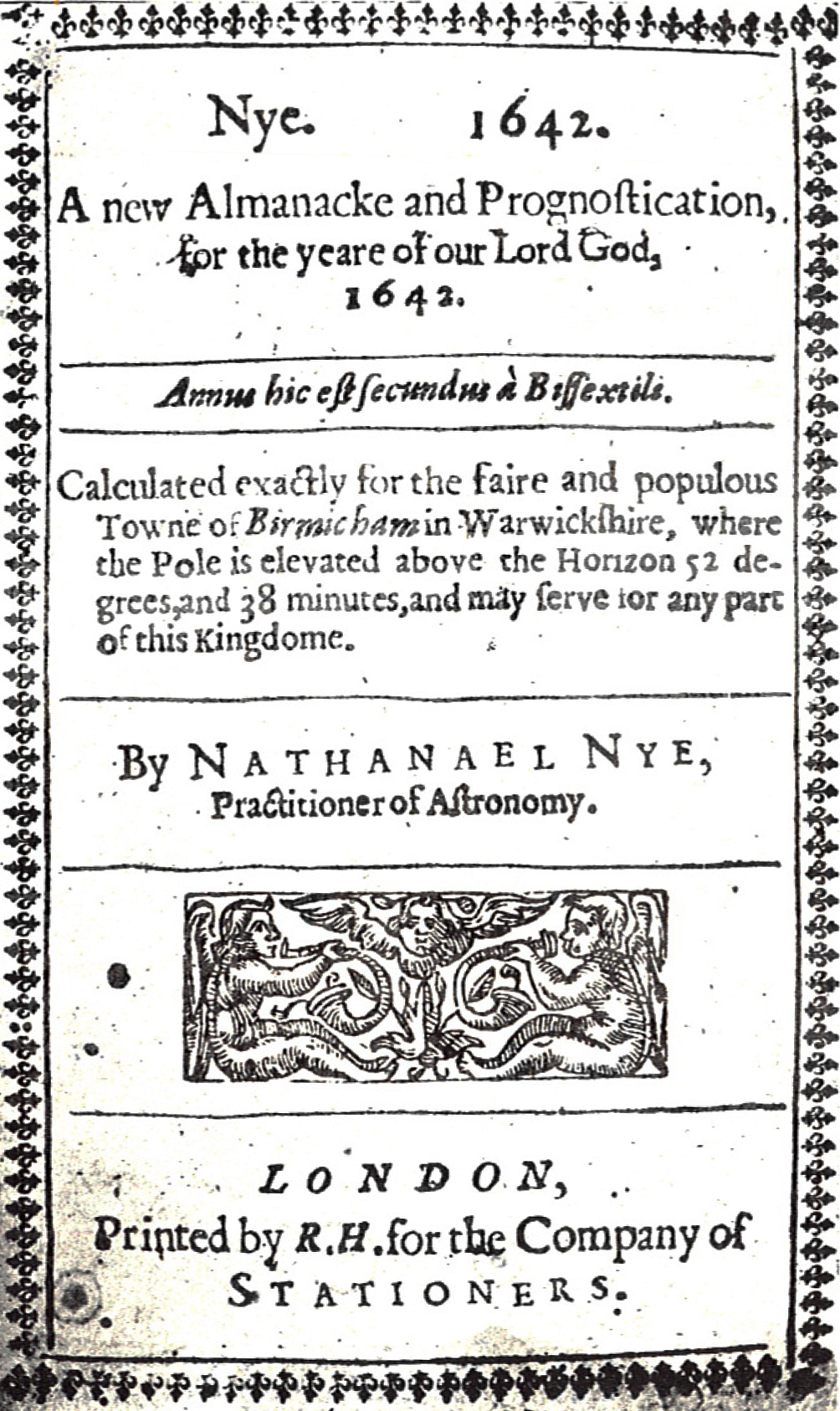

In 1642 the early Birmingham mathematician and astronomer

In 1642 the early Birmingham mathematician and astronomer  The earliest known clock makers in the town arrived from London in 1667. Between 1770 and 1870 there are over 700 clock and watch makers in the town.

In 1689 Sir Richard Newdigate, one of the new, local Newdigate baronets, approaches manufacturers in the town with the notion of supplying the British Government with

The earliest known clock makers in the town arrived from London in 1667. Between 1770 and 1870 there are over 700 clock and watch makers in the town.

In 1689 Sir Richard Newdigate, one of the new, local Newdigate baronets, approaches manufacturers in the town with the notion of supplying the British Government with

1732: The '' Birmingham Journal'' is founded and published from Thomas Warren's book store. This is possibly Birmingham's first weekly

1732: The '' Birmingham Journal'' is founded and published from Thomas Warren's book store. This is possibly Birmingham's first weekly  1738:

1738:  1743: A factory opens in

1743: A factory opens in  :A circular machine, of new design

:In conic shape: it draws and spins a thread

:Without the tedious toil of needless hands.

:A wheel, invisible, beneath the floor,

:To ev'ry member of th' harmonius frame,

:Gives necessary motion. One, intent,

:O'erlooks the work; the carded wool, he says,

:Is smoothly lapp'd around those cylinders,

:Which, gently turning, yield it to yon' cirque

:Of upright spindles, which with rapid whirl

:Spin out, in long extent, an even twine.

:A circular machine, of new design

:In conic shape: it draws and spins a thread

:Without the tedious toil of needless hands.

:A wheel, invisible, beneath the floor,

:To ev'ry member of th' harmonius frame,

:Gives necessary motion. One, intent,

:O'erlooks the work; the carded wool, he says,

:Is smoothly lapp'd around those cylinders,

:Which, gently turning, yield it to yon' cirque

:Of upright spindles, which with rapid whirl

:Spin out, in long extent, an even twine.

1757: Baskerville serif typeface is designed by

1757: Baskerville serif typeface is designed by  1765: The Lunar Society begins life as a dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the

1765: The Lunar Society begins life as a dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the  1767: A number of prominent Birmingham businessmen, including Matthew Boulton and others from the Lunar Society, hold a public meeting in the White Swan, High Street,''Smethwick and the BCN'', Malcolm D. Freeman, 2003, Sandwell MBC and Smethwick Heritage Centre Trust to consider the possibility of building a canal from Birmingham to the

1767: A number of prominent Birmingham businessmen, including Matthew Boulton and others from the Lunar Society, hold a public meeting in the White Swan, High Street,''Smethwick and the BCN'', Malcolm D. Freeman, 2003, Sandwell MBC and Smethwick Heritage Centre Trust to consider the possibility of building a canal from Birmingham to the  1779: Matthew Wasbrough designs and builds the Pickard Engine (first crank engine) for James Pickard of Snow Hill, this is defined as 'the first atmospheric engine in the world to directly achieve rotary motion by the use of a crank and

1779: Matthew Wasbrough designs and builds the Pickard Engine (first crank engine) for James Pickard of Snow Hill, this is defined as 'the first atmospheric engine in the world to directly achieve rotary motion by the use of a crank and  1781: James Watt markets his rotary-motion steam engine. The earlier steam engine's vertical movement was ideal for operating

1781: James Watt markets his rotary-motion steam engine. The earlier steam engine's vertical movement was ideal for operating  1788: Boulton and Watt build the rotative steam engine also known as a

1788: Boulton and Watt build the rotative steam engine also known as a  1794: Ralph Heaton patents a steam powered machine for mass-producing

1794: Ralph Heaton patents a steam powered machine for mass-producing  One impediment to Boulton's work is the lack of an

One impediment to Boulton's work is the lack of an  Boulton writes in 1771, "I am very desirous of becoming a great

Boulton writes in 1771, "I am very desirous of becoming a great

1802: The exterior of the

1802: The exterior of the  1821: Emanuel Heaton, gun finisher, takes out a patent for a watertight pan for

1821: Emanuel Heaton, gun finisher, takes out a patent for a watertight pan for  1828:

1828:  1830s:

1830s:  1832: William Chance, owner of a Birmingham iron merchants, invests in his brothers failing glass works in nearby

1832: William Chance, owner of a Birmingham iron merchants, invests in his brothers failing glass works in nearby  1832: A form of German silver is invented by Charles Askins, this is used to make spoons and

1832: A form of German silver is invented by Charles Askins, this is used to make spoons and  1839: Sir Edward Thomason improves the gun lock by making the cock detachable by the thumb and finger as well as making improvements to prevent misfires.

1839: Sir Edward Thomason improves the gun lock by making the cock detachable by the thumb and finger as well as making improvements to prevent misfires.

1845: During the late 1830s, canal steam boats begin operating with limited success but in 1845, Birmingham engineer

1845: During the late 1830s, canal steam boats begin operating with limited success but in 1845, Birmingham engineer  Galton formulates (and later coins the term for)

Galton formulates (and later coins the term for)  1858: After several failed attempts of launching the

1858: After several failed attempts of launching the

/ref> Richard Tangye's company then acquires the patent of the differential pulley-block in 1859, and in 1862 he invents the Tangye Patent 1867: The patent for a new type of direct-acting steam pump is acquired, in 1869 Tangye Ltd is commissioned to design the hydraulic systems for the UK's first

1867: The patent for a new type of direct-acting steam pump is acquired, in 1869 Tangye Ltd is commissioned to design the hydraulic systems for the UK's first  The first

The first  1863: William Sumner (founder of

1863: William Sumner (founder of  1868: C.H. Gould patents a British

1868: C.H. Gould patents a British  1876: William Bown patents a design for the wheels of

1876: William Bown patents a design for the wheels of  1880: Gamgee Tissue, a surgical dressing with a thick layer of absorbent cotton wool between two layers of absorbent gauze, is invented by Joseph Sampson Gamgee. It represents the first use of cotton wool in a medical context, and is a major advancement in the prevention of infection of surgical wounds. It is still the basis for many modern surgical dressings. Gamgee also invents the

1880: Gamgee Tissue, a surgical dressing with a thick layer of absorbent cotton wool between two layers of absorbent gauze, is invented by Joseph Sampson Gamgee. It represents the first use of cotton wool in a medical context, and is a major advancement in the prevention of infection of surgical wounds. It is still the basis for many modern surgical dressings. Gamgee also invents the  John Richard Dedicoat invents a bicycle bell, his patents for bicycle bells appear as early as 1877. Apprenticed to James Watt, Dedicoat goes on to become a bicycle manufacturer and makes and sells the "Pegasus" bicycle.

1883:

John Richard Dedicoat invents a bicycle bell, his patents for bicycle bells appear as early as 1877. Apprenticed to James Watt, Dedicoat goes on to become a bicycle manufacturer and makes and sells the "Pegasus" bicycle.

1883:  1885:

1885:  1894: Richard Norris, a doctor of medicine and professor of physiology at Queen's College, Birmingham, brings out a new patent of dry plate used in photography and is generally credited with the first development of the

1894: Richard Norris, a doctor of medicine and professor of physiology at Queen's College, Birmingham, brings out a new patent of dry plate used in photography and is generally credited with the first development of the  1895:

1895:  Wolseley later becomes a successful car and engine maker selling upmarket cars, and even opens a lavish showroom, Wolseley House, in

Wolseley later becomes a successful car and engine maker selling upmarket cars, and even opens a lavish showroom, Wolseley House, in

Bicycles have been manufactured in the Midlands (mainly Birmingham and

Bicycles have been manufactured in the Midlands (mainly Birmingham and  1902: The first caliper-type automobile

1902: The first caliper-type automobile  Hopkinson builds a team of researchers, one of whom is

Hopkinson builds a team of researchers, one of whom is  1905: A manually powered domestic

1905: A manually powered domestic  1906: The earliest work on the parkerizing processes is developed by British inventors William Alexander Ross, in 1869, and by Thomas Watts Coslett, in 1906. Coslett, of Birmingham, subsequently files a patent based on this same process in America in 1907. It essentially provides an iron phosphating process, using

1906: The earliest work on the parkerizing processes is developed by British inventors William Alexander Ross, in 1869, and by Thomas Watts Coslett, in 1906. Coslett, of Birmingham, subsequently files a patent based on this same process in America in 1907. It essentially provides an iron phosphating process, using  Birmingham's ingenuity and expertise in metal working aids the early production of lightweight tubing used in the construction of successful airplanes. Engineering firms pioneer advances in aircraft engines also such as

Birmingham's ingenuity and expertise in metal working aids the early production of lightweight tubing used in the construction of successful airplanes. Engineering firms pioneer advances in aircraft engines also such as  1910: Lucas Industries, Oliver Lucas's company design and make an electric car vehicle horn, which becomes industry standard; an electric motorcycle horn is manufactured the following year.

1913:

1910: Lucas Industries, Oliver Lucas's company design and make an electric car vehicle horn, which becomes industry standard; an electric motorcycle horn is manufactured the following year.

1913:  1918: Much work is carried out by Oliver Lucas's company on the design and improvement of the military search light, he also designs a signalling lamp after experiences at the Somme (department), Somme and the design is later used by the British Army.

1919: The airbag "for the covering of aeroplane and other vehicle parts" traces its origins to a United States patent submitted in 1919 by two Birmingham dentists, Harold Round & Arthur Parrott, and approved in 1920.

1920: Charles Henry Foyle invents the folding carton and is founder of Boxfoldia. However, an American process is developed by accident prior to this.

1921: A British patent for windscreen wipers is registered by Mills Munitions. Several other patents take place for windscreen wipers around the world.

1922: Birmingham rubber manufacturer Dunlop Rubber, Dunlop invents a tire, tyre with steel rods and a canvas casing that lasts three times longer than any other tyre, this is a milestone in tyre manufacture. The following year their tyres help Henry Segrave win a Grand Prix motor racing, Grand Prix title in a Sunbeam Motor Car Company, Sunbeam racing car, and are then used on a Bentley to help win the 24 Hours of Le Mans race.

By 1927 Dunlop tyres have already helped Malcolm Campbell reach a British land speed record and in this year, they help Henry Segrave achieve the world land speed record in a Sunbeam 1000 hp at Daytona Beach Road Course, USA.

1918: Much work is carried out by Oliver Lucas's company on the design and improvement of the military search light, he also designs a signalling lamp after experiences at the Somme (department), Somme and the design is later used by the British Army.

1919: The airbag "for the covering of aeroplane and other vehicle parts" traces its origins to a United States patent submitted in 1919 by two Birmingham dentists, Harold Round & Arthur Parrott, and approved in 1920.

1920: Charles Henry Foyle invents the folding carton and is founder of Boxfoldia. However, an American process is developed by accident prior to this.

1921: A British patent for windscreen wipers is registered by Mills Munitions. Several other patents take place for windscreen wipers around the world.

1922: Birmingham rubber manufacturer Dunlop Rubber, Dunlop invents a tire, tyre with steel rods and a canvas casing that lasts three times longer than any other tyre, this is a milestone in tyre manufacture. The following year their tyres help Henry Segrave win a Grand Prix motor racing, Grand Prix title in a Sunbeam Motor Car Company, Sunbeam racing car, and are then used on a Bentley to help win the 24 Hours of Le Mans race.

By 1927 Dunlop tyres have already helped Malcolm Campbell reach a British land speed record and in this year, they help Henry Segrave achieve the world land speed record in a Sunbeam 1000 hp at Daytona Beach Road Course, USA.  In 1931 Dunlop tyres help Malcolm Campbell achieve a new land speed record in a Campbell-Napier-Railton Blue Bird, Blue Bird at Daytona Beach Road Course, USA. In 1935 Dunlop helps Malcolm Campbell achieve yet another new land speed record in the USA. Foam rubber is also invented at the Dunlop Latex Development Laboratories,

In 1931 Dunlop tyres help Malcolm Campbell achieve a new land speed record in a Campbell-Napier-Railton Blue Bird, Blue Bird at Daytona Beach Road Course, USA. In 1935 Dunlop helps Malcolm Campbell achieve yet another new land speed record in the USA. Foam rubber is also invented at the Dunlop Latex Development Laboratories,  1926: Cameras have been made in Birmingham since 1880, by companies such as J. Lancaster & Son and in 1926 Coronet Camera Company, Coronet begin manufacturing cameras in the city. Coronet eventually mass-produce cheap, but affordable cameras. Coronet have close links with other Birmingham camera makers such as Standard Cameras Ltd (featured in the National Media Museum) and E Elliott Ltd, who manufacture the unique and now collectible V. P. Twin (featured in the Museum of early consumer electronics and 1st achievements).

1928: Brummie, Oscar Deutsch opens his first Odeon Cinemas, Odeon Cinema in nearby Brierley Hill. By 1930, "Odeon" is a household name and the cinemas are known for their maritime-inspired Art Deco architecture. This style is first used in 1930 on the cinema at Perry Barr in Birmingham, which is bought by Deutsch to expand the chain. He likes the style so much that he commissions the architect, Harry Weedon, to design his future buildings. The Odeon cinema chain later becomes one of the largest cinema chains in Europe.

1926: Cameras have been made in Birmingham since 1880, by companies such as J. Lancaster & Son and in 1926 Coronet Camera Company, Coronet begin manufacturing cameras in the city. Coronet eventually mass-produce cheap, but affordable cameras. Coronet have close links with other Birmingham camera makers such as Standard Cameras Ltd (featured in the National Media Museum) and E Elliott Ltd, who manufacture the unique and now collectible V. P. Twin (featured in the Museum of early consumer electronics and 1st achievements).

1928: Brummie, Oscar Deutsch opens his first Odeon Cinemas, Odeon Cinema in nearby Brierley Hill. By 1930, "Odeon" is a household name and the cinemas are known for their maritime-inspired Art Deco architecture. This style is first used in 1930 on the cinema at Perry Barr in Birmingham, which is bought by Deutsch to expand the chain. He likes the style so much that he commissions the architect, Harry Weedon, to design his future buildings. The Odeon cinema chain later becomes one of the largest cinema chains in Europe.

1928: The George Tucker Eyelet company, of Birmingham, England, produced a type of "cup" rivet. This is later developed as the "POP rivet".

1929: Brylcreem (made famous by the Teddy Boy) is invented in the city and later gives rise to other hair styling products.

First production run of Midland Red, Birmingham and Midland Motor Omnibus Company (Midland Red) buses takes place during the 1920s—one of the first British buses to have pneumatic tyres. BMMO later develop petrol and diesel engines during the 1930s, with experimental rear-engined buses being built. By the 1940s experiments with, and production of under-floor engined single-deck buses take place. Experiments and developments of independent front suspension, air suspension, rubber suspension, glass fibre construction and disc brakes take place during the 1950s. 1959 sees the introduction of a turbocharged coach capable of almost 100 mph, for non-stop motorway services. High speed (motorway) buses are developed with passenger toilets. During the 1960s BMMO becomes the first British bus company to make wide-scale use of computers in compiling bus schedules and staff rosters.

1932: The Birmingham Sound Reproducers company is set up in the West Midlands. In the early 1950s, Samuel Margolin begins buying auto-changing phonograph, turntables from BSR, using them as the basis of his Dansette record player. Over the next twenty years, "Dansette" becomes a household word in Britain. By 1957, BSR has grown to employ 2,600 workers. In addition to manufacturing their own brand of player—the Monarch Automatic Record Changer that could select and play 7", 10" and 12" records at 33, 45 or 78 rpm, changing between the various settings automatically—BSR McDonald supplied turntables and autochangers to most of the world's record player manufacturers, eventually gaining 87% of the market. By 1977, BSR's various factories produced over 250,000 units a week.

1932: Leonard Parsons is the first to use Chemical synthesis, synthetic vitamin C as treatment for scurvy in children.

1933: Credenda Conduit Co. Ltd of Birmingham patent a Credastat automatic oven thermostat, which is fitted to Creda electric cookers. This is an early advancement in electric cookers and a feature that eventually becomes standard on all electric cookers. An example of this cooker is on display at the London Science Museum.

1934: The Reynolds Tube Company introduces the Reynolds 531, double-butted tube-set 531 for high strength but lightweight bicycle frames. Reynolds 531 remains for many years at the forefront of alloy steel tubing technology and is used to form the front subframes on the Jaguar E-Type during the 1960s. Before the introduction of more exotic materials such as aluminium, titanium or Composite material, composites, Reynolds is considered the dominant maker of high end materials for bicycle frames. According to the company, 27 winners of the

1928: The George Tucker Eyelet company, of Birmingham, England, produced a type of "cup" rivet. This is later developed as the "POP rivet".

1929: Brylcreem (made famous by the Teddy Boy) is invented in the city and later gives rise to other hair styling products.

First production run of Midland Red, Birmingham and Midland Motor Omnibus Company (Midland Red) buses takes place during the 1920s—one of the first British buses to have pneumatic tyres. BMMO later develop petrol and diesel engines during the 1930s, with experimental rear-engined buses being built. By the 1940s experiments with, and production of under-floor engined single-deck buses take place. Experiments and developments of independent front suspension, air suspension, rubber suspension, glass fibre construction and disc brakes take place during the 1950s. 1959 sees the introduction of a turbocharged coach capable of almost 100 mph, for non-stop motorway services. High speed (motorway) buses are developed with passenger toilets. During the 1960s BMMO becomes the first British bus company to make wide-scale use of computers in compiling bus schedules and staff rosters.

1932: The Birmingham Sound Reproducers company is set up in the West Midlands. In the early 1950s, Samuel Margolin begins buying auto-changing phonograph, turntables from BSR, using them as the basis of his Dansette record player. Over the next twenty years, "Dansette" becomes a household word in Britain. By 1957, BSR has grown to employ 2,600 workers. In addition to manufacturing their own brand of player—the Monarch Automatic Record Changer that could select and play 7", 10" and 12" records at 33, 45 or 78 rpm, changing between the various settings automatically—BSR McDonald supplied turntables and autochangers to most of the world's record player manufacturers, eventually gaining 87% of the market. By 1977, BSR's various factories produced over 250,000 units a week.

1932: Leonard Parsons is the first to use Chemical synthesis, synthetic vitamin C as treatment for scurvy in children.

1933: Credenda Conduit Co. Ltd of Birmingham patent a Credastat automatic oven thermostat, which is fitted to Creda electric cookers. This is an early advancement in electric cookers and a feature that eventually becomes standard on all electric cookers. An example of this cooker is on display at the London Science Museum.

1934: The Reynolds Tube Company introduces the Reynolds 531, double-butted tube-set 531 for high strength but lightweight bicycle frames. Reynolds 531 remains for many years at the forefront of alloy steel tubing technology and is used to form the front subframes on the Jaguar E-Type during the 1960s. Before the introduction of more exotic materials such as aluminium, titanium or Composite material, composites, Reynolds is considered the dominant maker of high end materials for bicycle frames. According to the company, 27 winners of the  1935: Birmingham has a long history of toy and trinket manufacture and in 1935 the biggest toy makers in England, Chad Valley (toy brand), Chad Valley, are appointed Toy Makers to the Queen of the United Kingdom. During their existence Chad Valley carry out several improvements and practices in the manufacture of toys during their production between the late 19th and mid-20th centuries, constantly striving to develop new board games, jigsaw puzzle, jigsaws and toys.

1937: Professor Norman Haworth is awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry for his pioneering work on carbohydrates and synthetic vitamin C.

1939: Dr Mary Evans (chemist), Mary Evans and Dr Wilfred Gaisford begin trials of the world's first antibiotic May & Baker, M&B (sulfapyridine) as treatment for lobar pneumonia.

Birmingham becomes the major British manufacturer of the phenolic resin, phenolic plastic Bakelite.

1935: Birmingham has a long history of toy and trinket manufacture and in 1935 the biggest toy makers in England, Chad Valley (toy brand), Chad Valley, are appointed Toy Makers to the Queen of the United Kingdom. During their existence Chad Valley carry out several improvements and practices in the manufacture of toys during their production between the late 19th and mid-20th centuries, constantly striving to develop new board games, jigsaw puzzle, jigsaws and toys.

1937: Professor Norman Haworth is awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry for his pioneering work on carbohydrates and synthetic vitamin C.

1939: Dr Mary Evans (chemist), Mary Evans and Dr Wilfred Gaisford begin trials of the world's first antibiotic May & Baker, M&B (sulfapyridine) as treatment for lobar pneumonia.

Birmingham becomes the major British manufacturer of the phenolic resin, phenolic plastic Bakelite.

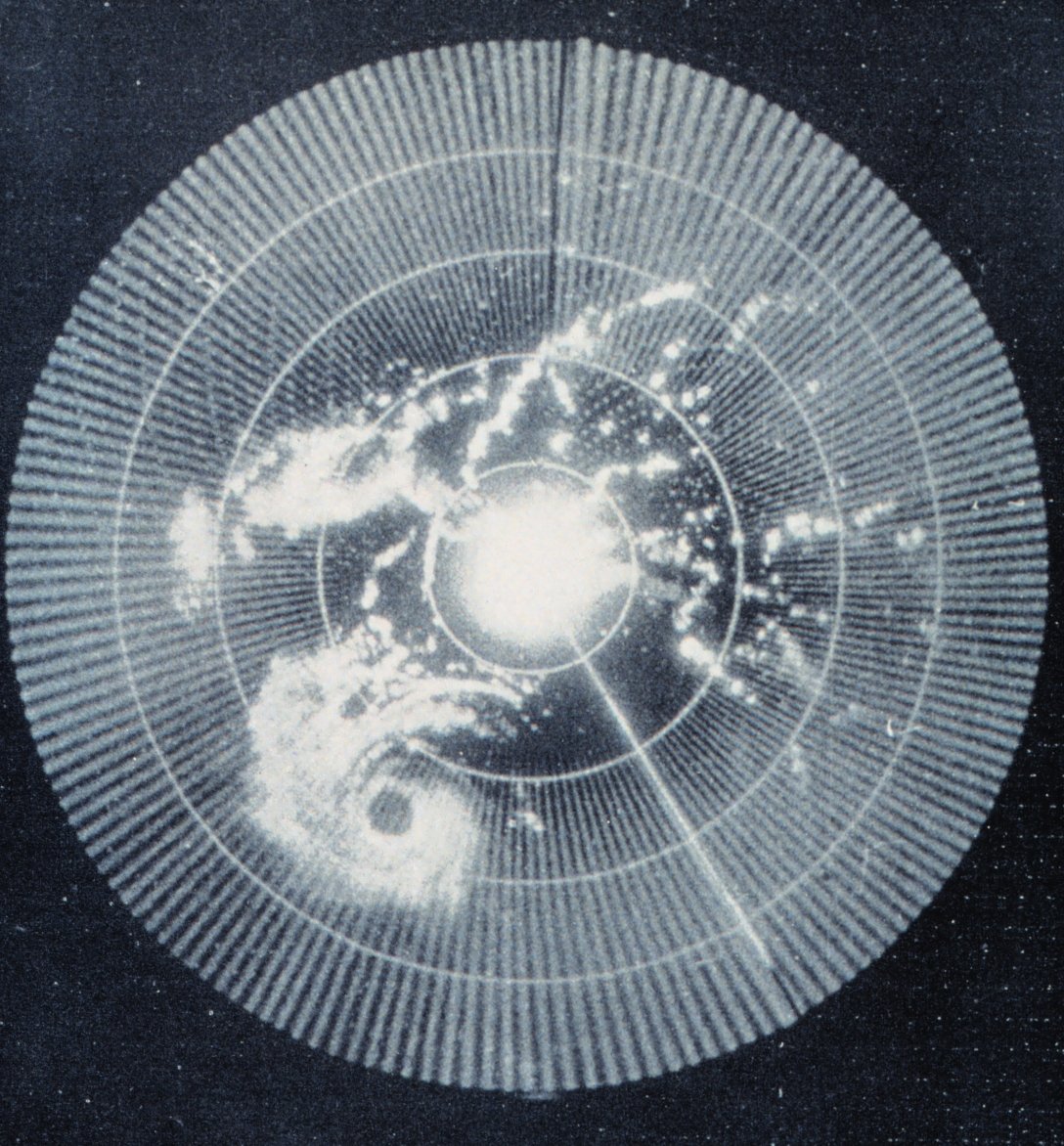

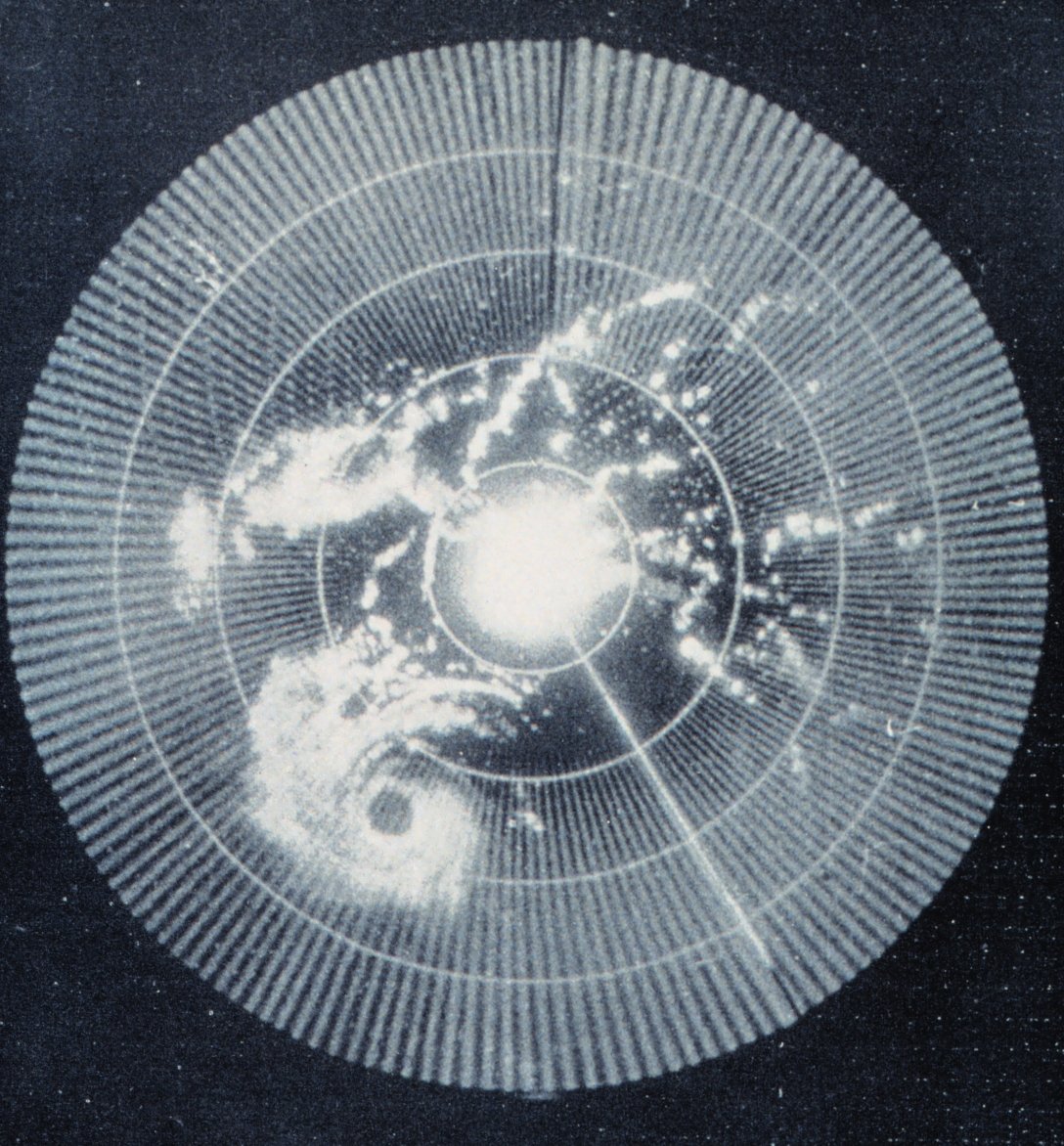

The magnetron, the core component in the development of radar, and the first microwave power oscillators are developed at the

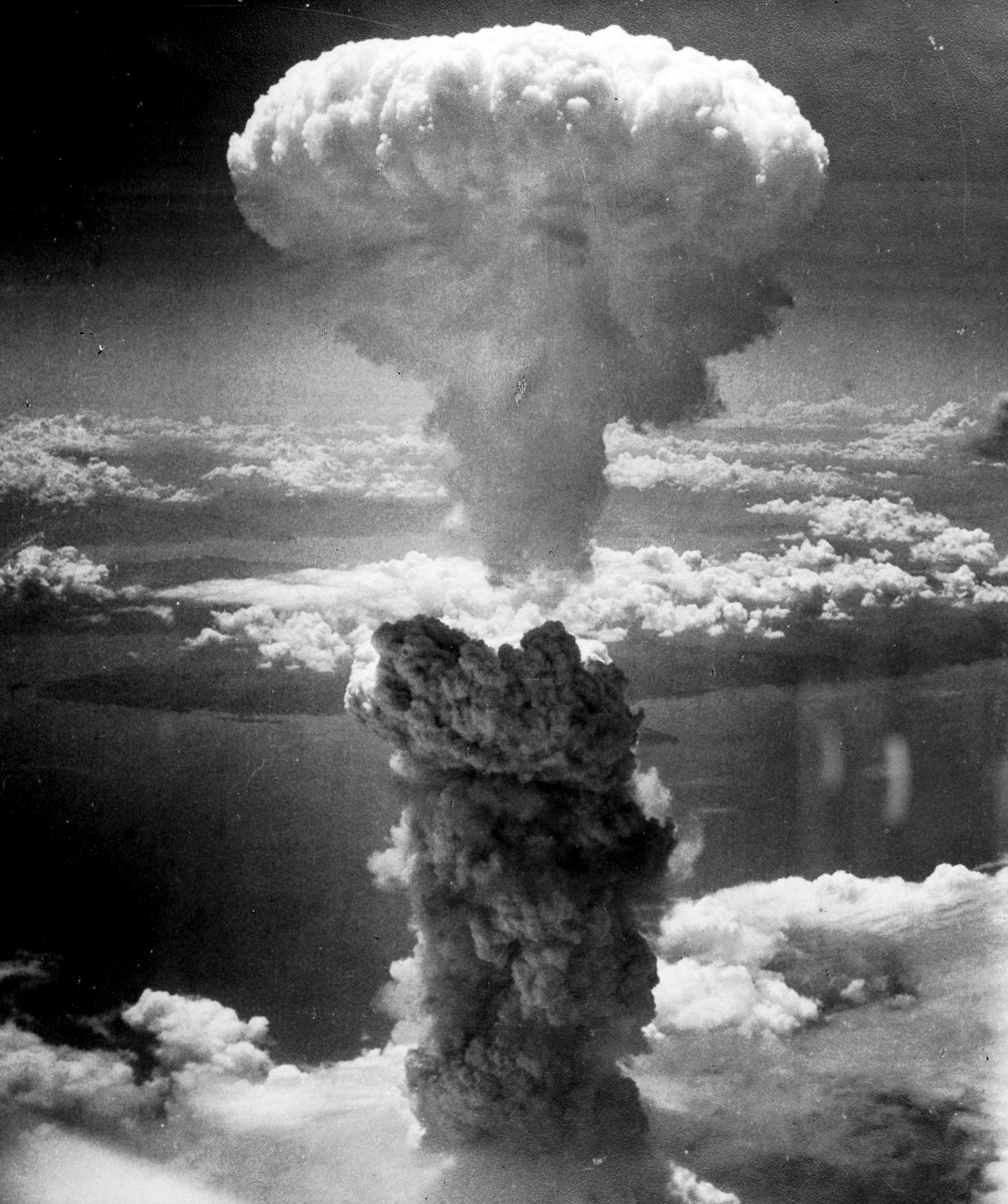

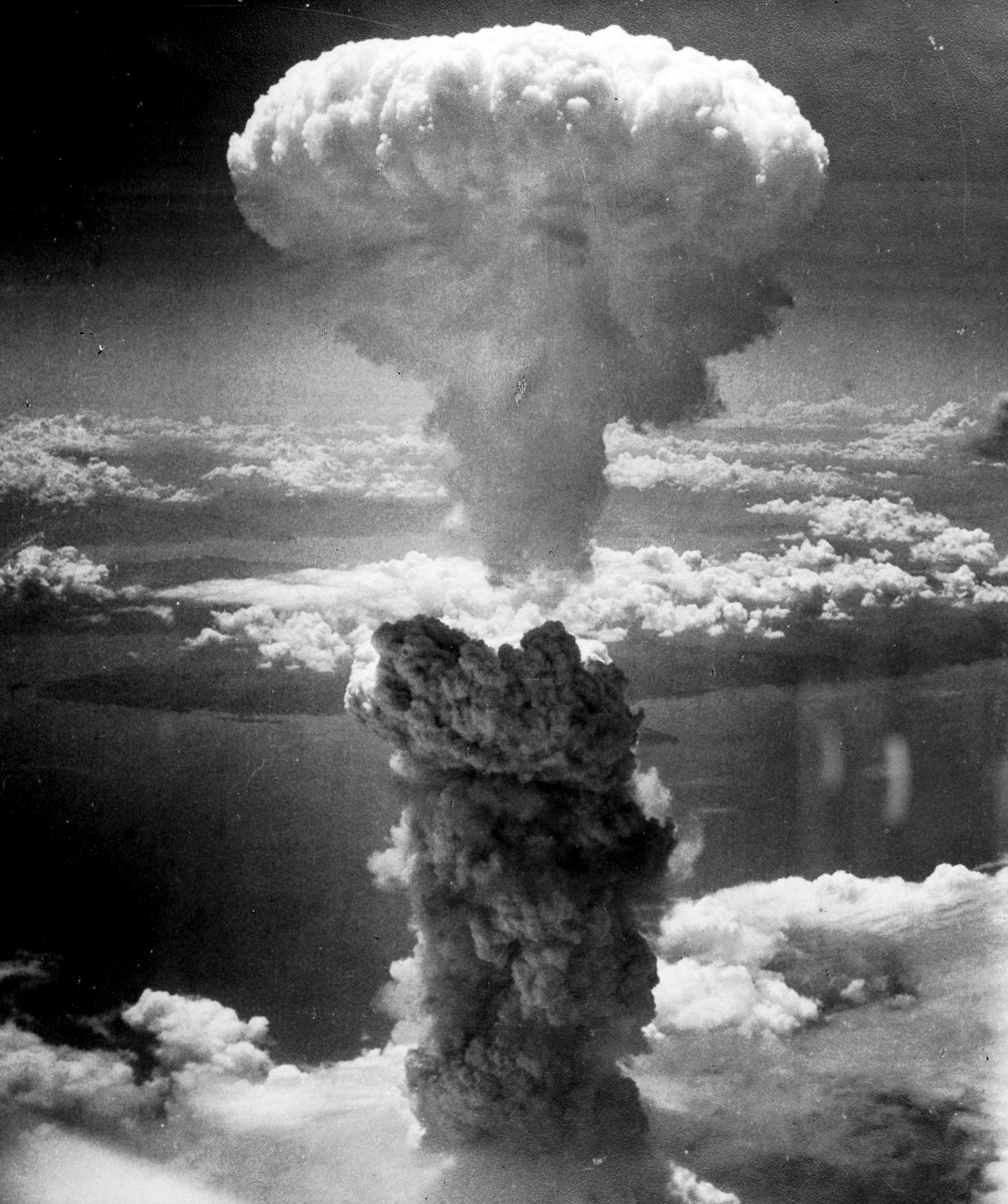

The magnetron, the core component in the development of radar, and the first microwave power oscillators are developed at the  1940: The Frisch–Peierls memorandum is finalised by Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls while both working at Birmingham University—this is the first document to set out a process by which an atomic explosion could be generated.

1944: Anthony E. Pratt, Anthony Ernest Pratt takes out his first patent for a board game named 'Murder', this is later to become the world-renowned murder mystery game 'Cluedo'.

1946: Chance Brothers produce the first all-glass syringe with interchangeable barrel and plunger, thereby allowing mass sterilisation of components without the need for matching them.

1947: Dunlop tyres help John Cobb (racing driver), John Cobb raise the world land speed record to 630 km/h in the Railton Special, which is now displayed in Birmingham's Thinktank museum.

Between 1947 and 1951 Professor Peter Medawar pioneers research on skin graft rejection at Birmingham University, this leads to the discovery of a substance that aids nerves to reunite and the discovery of acquired immunological tolerance, Medawar is awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1960 for his work during this time.

1950: In February, the first operation in England for 'hole-in-the-heart' (congenital atrial septal defect) is performed at Birmingham Children's Hospital.

Conway Berners-Lee, a mathematician and computer scientist from Birmingham, works in the team that develops the Ferranti Mark 1, the world's first commercial stored program electronic computer. Berners-Lee is demobilized from the British Army in 1947 with the rank of Major. By the late 1960s Berners-Lee leads the Medical Development Team of ICT and then ICL and is involved in some of the earliest developments in the applications of computers in medicine, and his text compression ideas are taken up by an early electronic patient record system. Berners-Lee later marries Mary Lee Woods (also from Birmingham). Woods studies at Birmingham University and later works in the team that develop programs for the Manchester Mark 1, Ferranti Mark 1 and Mark 1 Star computers. In 1955 the Berners-Lees become parents to Tim Berners-Lee, who invents the World Wide Web, making the first proposal for it in March 1989.

1940: The Frisch–Peierls memorandum is finalised by Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls while both working at Birmingham University—this is the first document to set out a process by which an atomic explosion could be generated.

1944: Anthony E. Pratt, Anthony Ernest Pratt takes out his first patent for a board game named 'Murder', this is later to become the world-renowned murder mystery game 'Cluedo'.

1946: Chance Brothers produce the first all-glass syringe with interchangeable barrel and plunger, thereby allowing mass sterilisation of components without the need for matching them.

1947: Dunlop tyres help John Cobb (racing driver), John Cobb raise the world land speed record to 630 km/h in the Railton Special, which is now displayed in Birmingham's Thinktank museum.

Between 1947 and 1951 Professor Peter Medawar pioneers research on skin graft rejection at Birmingham University, this leads to the discovery of a substance that aids nerves to reunite and the discovery of acquired immunological tolerance, Medawar is awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1960 for his work during this time.

1950: In February, the first operation in England for 'hole-in-the-heart' (congenital atrial septal defect) is performed at Birmingham Children's Hospital.

Conway Berners-Lee, a mathematician and computer scientist from Birmingham, works in the team that develops the Ferranti Mark 1, the world's first commercial stored program electronic computer. Berners-Lee is demobilized from the British Army in 1947 with the rank of Major. By the late 1960s Berners-Lee leads the Medical Development Team of ICT and then ICL and is involved in some of the earliest developments in the applications of computers in medicine, and his text compression ideas are taken up by an early electronic patient record system. Berners-Lee later marries Mary Lee Woods (also from Birmingham). Woods studies at Birmingham University and later works in the team that develop programs for the Manchester Mark 1, Ferranti Mark 1 and Mark 1 Star computers. In 1955 the Berners-Lees become parents to Tim Berners-Lee, who invents the World Wide Web, making the first proposal for it in March 1989.

1952: Professor Charlotte Anderson (Leonard Parsons Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health) is one of the team who prove that the glutens in wheat cause coeliac disease, from this gluten-free diets are introduced.

1954: The Stewart platform (a parallel robot) first comes into use. Stewart platforms have applications in machine tool technology, crane technology, underwater research, air-to-sea rescue, satellite dish positioning, telescopes and orthopedic surgery but are better known for flight simulation.

1950–1959: Essential research and development on heart pacemakers and plastic heart valves is carried out by Leon Abrams at Birmingham University.

1959: The Mini car begins production at Birmingham's Longbridge plant. The original is considered a British icon of the 1960s, and its space-saving front-wheel-drive layout (which allowed 80% of the area of the car's floorpan to be used for passengers and luggage) influenced a generation of car makers. In 1999 the Mini was voted the second most influential Car of the Century, car of the 20th century, behind the Ford Model T."This Just In: Model T Gets Award"

1952: Professor Charlotte Anderson (Leonard Parsons Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health) is one of the team who prove that the glutens in wheat cause coeliac disease, from this gluten-free diets are introduced.

1954: The Stewart platform (a parallel robot) first comes into use. Stewart platforms have applications in machine tool technology, crane technology, underwater research, air-to-sea rescue, satellite dish positioning, telescopes and orthopedic surgery but are better known for flight simulation.

1950–1959: Essential research and development on heart pacemakers and plastic heart valves is carried out by Leon Abrams at Birmingham University.

1959: The Mini car begins production at Birmingham's Longbridge plant. The original is considered a British icon of the 1960s, and its space-saving front-wheel-drive layout (which allowed 80% of the area of the car's floorpan to be used for passengers and luggage) influenced a generation of car makers. In 1999 the Mini was voted the second most influential Car of the Century, car of the 20th century, behind the Ford Model T."This Just In: Model T Gets Award"

James G. Cobb, ''The New York Times'', 24 December 1999 1962: Maurice Wilkins, New Zealand born and Birmingham raised, receives the Nobel Prize for his work on DNA structure, he is one of three who become known as the Code Breakers. Wilkins is educated at King Edward's School, Birmingham, King Edward's School (and St John's College, Cambridge), he receives a PhD for the study of phosphors at the

1962: Maurice Wilkins, New Zealand born and Birmingham raised, receives the Nobel Prize for his work on DNA structure, he is one of three who become known as the Code Breakers. Wilkins is educated at King Edward's School, Birmingham, King Edward's School (and St John's College, Cambridge), he receives a PhD for the study of phosphors at the  1962: Bill Fransen of American company Chamberlins brings two of their musical instruments to England to search for someone who could manufacture 70 matching tape heads for future Chamberlin keyboards. Fransen approaches a UK company that is skilled enough to develop the idea further and a deal is struck with Bradmatic Ltd. The first Mellotron sample keyboards are manufactured in Aston and are to enjoy great longevity in the music industry. Alongside the Hammond organ, the Mellotron later becomes a seminal musical instrument for music genres such as rock music, rock and psychedelia, it is also crucial to shaping the sound of the progressive rock and hard rock groups of the 1970s as well as inspiring further development of the sample keyboard, most notably the Fairlight (company), Fairlight, which, in turn, inspired sample modules such as the Akai Sampler range; synonymous with hip hop and dance music.

Some of the more notable songs that make use of the signature Mellotron sound include Nights In White Satin by The Moody Blues, Tomorrow Never Knows and Strawberry Fields Forever by The Beatles, 2000 Light Years from Home and We Love You by The Rolling Stones, Hole In My Shoe by Traffic (band), Traffic, Mercy Mercy Me by Marvin Gaye, Days (The Kinks song), Days by The Kinks, Space Oddity by David Bowie, Stairway to Heaven, The Rain Song and Kashmir (song), Kashmir by Led Zeppelin.

1965: ''The Birmingham Press and Mail'' installs the GEC PABX 4 ACD, the earliest example of a call centre in the UK. Already the hallmarks of the call centre can be seen in the rows of agents with individual phone terminals, taking and making calls.

1969–1970: Heavy metal music begins to take shape in Britain and America. Of the earliest influential bands that are later to be described as Heavy Metal, several of the most notable artists arise from the mid to late 1960s Brum Beat music scene, such as: Robert Plant and John Bonham of Led Zeppelin, Ozzy Osbourne, Tony Iommi, Geezer Butler and Bill Ward (musician), Bill Ward of Black Sabbath and Rob Halford and Glenn Tipton of Judas Priest.

1962: Bill Fransen of American company Chamberlins brings two of their musical instruments to England to search for someone who could manufacture 70 matching tape heads for future Chamberlin keyboards. Fransen approaches a UK company that is skilled enough to develop the idea further and a deal is struck with Bradmatic Ltd. The first Mellotron sample keyboards are manufactured in Aston and are to enjoy great longevity in the music industry. Alongside the Hammond organ, the Mellotron later becomes a seminal musical instrument for music genres such as rock music, rock and psychedelia, it is also crucial to shaping the sound of the progressive rock and hard rock groups of the 1970s as well as inspiring further development of the sample keyboard, most notably the Fairlight (company), Fairlight, which, in turn, inspired sample modules such as the Akai Sampler range; synonymous with hip hop and dance music.

Some of the more notable songs that make use of the signature Mellotron sound include Nights In White Satin by The Moody Blues, Tomorrow Never Knows and Strawberry Fields Forever by The Beatles, 2000 Light Years from Home and We Love You by The Rolling Stones, Hole In My Shoe by Traffic (band), Traffic, Mercy Mercy Me by Marvin Gaye, Days (The Kinks song), Days by The Kinks, Space Oddity by David Bowie, Stairway to Heaven, The Rain Song and Kashmir (song), Kashmir by Led Zeppelin.

1965: ''The Birmingham Press and Mail'' installs the GEC PABX 4 ACD, the earliest example of a call centre in the UK. Already the hallmarks of the call centre can be seen in the rows of agents with individual phone terminals, taking and making calls.

1969–1970: Heavy metal music begins to take shape in Britain and America. Of the earliest influential bands that are later to be described as Heavy Metal, several of the most notable artists arise from the mid to late 1960s Brum Beat music scene, such as: Robert Plant and John Bonham of Led Zeppelin, Ozzy Osbourne, Tony Iommi, Geezer Butler and Bill Ward (musician), Bill Ward of Black Sabbath and Rob Halford and Glenn Tipton of Judas Priest.

During the later half of the 20th century the first trials of the combined oral contraceptive pill outside the USA take place at Birmingham University and extensive research into advanced allergy vaccines and the synthesis of artificial blood take place.

1975: Birmingham inventor Michael Gerzon co-invents the Soundfield microphone. Gerzon studies at the University of Oxford, and is inspired by Alan Blumlein's landmark 1933 development of stereophonic recording and reproduction. The Soundfield range of microphones are now considered the ultimate microphones for recording both stereophonic and Surround sound, multichannel surround formats.

During the later half of the 20th century the first trials of the combined oral contraceptive pill outside the USA take place at Birmingham University and extensive research into advanced allergy vaccines and the synthesis of artificial blood take place.

1975: Birmingham inventor Michael Gerzon co-invents the Soundfield microphone. Gerzon studies at the University of Oxford, and is inspired by Alan Blumlein's landmark 1933 development of stereophonic recording and reproduction. The Soundfield range of microphones are now considered the ultimate microphones for recording both stereophonic and Surround sound, multichannel surround formats.  Gerzon later plays a large role in the invention of Ambisonics, which is a series of recording and replay techniques using multichannel mixing technology that can be used live or in the studio. 5

Gerzon later plays a large role in the invention of Ambisonics, which is a series of recording and replay techniques using multichannel mixing technology that can be used live or in the studio. 5

dead link and should be set up as a --> Balti (food), Balti cuisine becomes nationally renowned, after initial growth in the city during the late 1980s. Today Balti restaurants are extremely popular throughout Britain and abroad. Sir John Robert Vane, winner of a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1982 for his work on aspirin, is educated at King Edward's School, Birmingham, King Edward's School and studies Chemistry at the

Inventions from Aston University

Innovators and inventors from the University of Birmingham

{{DEFAULTSORT:Science And Invention In Birmingham Economy of Birmingham, West Midlands History of science and technology in England, Birmingham, Science And Invention Science and technology in the West Midlands (county), Birmingham History of Birmingham, West Midlands Industry in Birmingham, West Midlands English inventions Lists of inventions or discoveries

Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

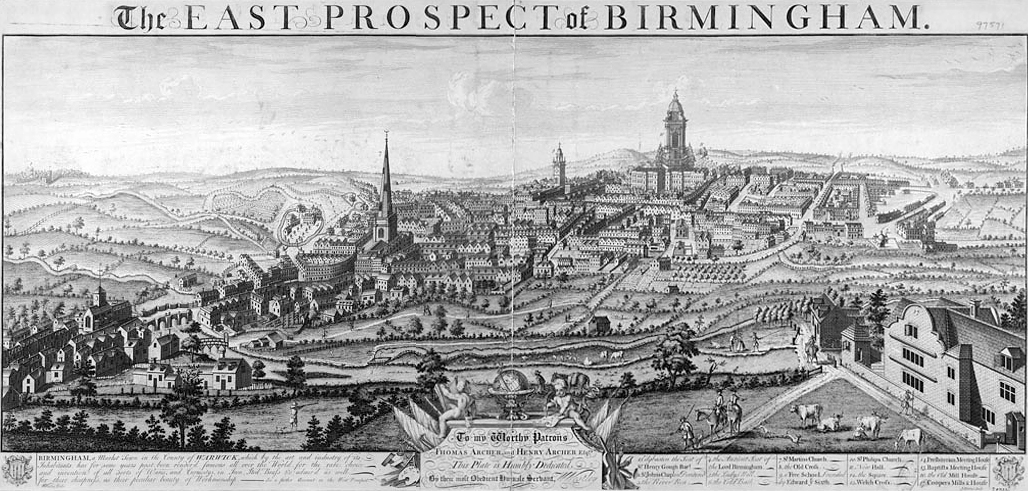

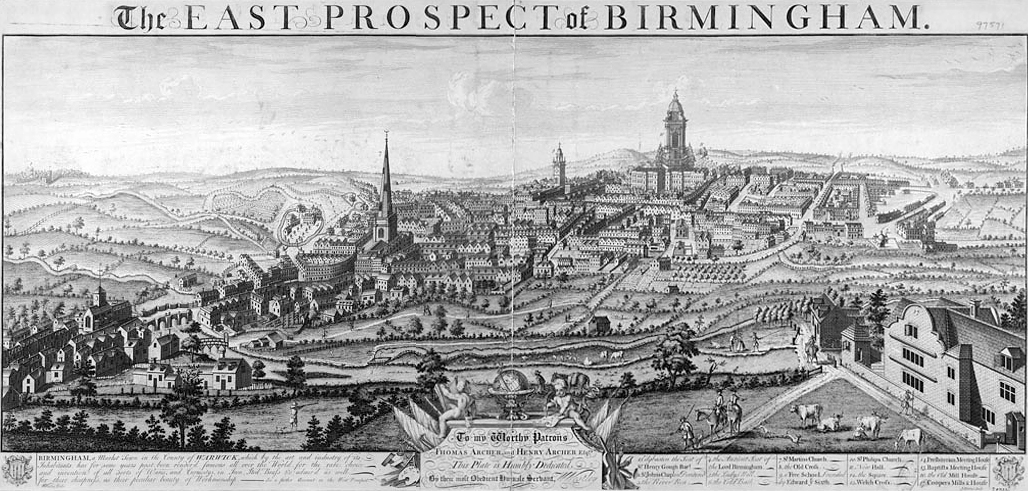

is one of England's principal industrial centres and has a history of industrial and scientific innovation. It was once known as ' city of a thousand trades' and in 1791, Arthur Young (the writer and commentator on British economic life) described Birmingham as "the first manufacturing town in the world". Right up until the mid-19th century Birmingham was regarded as the prime industrial urban town in Britain and perhaps the world, the town's rivals were more specific in their trade bases. Mill

Mill may refer to:

Science and technology

*

* Mill (grinding)

* Milling (machining)

* Millwork

* Textile mill

* Steel mill, a factory for the manufacture of steel

* List of types of mill

* Mill, the arithmetic unit of the Analytical Engine early ...

s and foundries across the world were helped along by the advances in steam power

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be tra ...

and engineering

Engineering is the use of scientific principles to design and build machines, structures, and other items, including bridges, tunnels, roads, vehicles, and buildings. The discipline of engineering encompasses a broad range of more speciali ...

that were taking place in the city. The town offered a vast array of industries and was the world's leading manufacturer of metal ware, although this was by no means the only trade flourishing in the town.

By the year 2000, of the 4,000 inventions copyrighted annually in the UK, 2,800 came from within a 35-mile radius of Birmingham. Peter Colegate of the Patent Office stated that "Every year, Birmingham amazes us by coming up with thousands of inventions. It is impossible to explain but people in the area seem to have a remarkable ability to come up with, and have the dedication to produce, ideas."

While the time line of industry and innovation listed below is extensive, it is by no means a comprehensive list of Birmingham's industrial and scientific achievements, more a guide to highlight the great diversity in the city's industrial might, which can still be seen today.

Pre-17th century

Birmingham's reputation for trade and innovation really begins to take off in the 12th century with the expansion of a market held there by the

Birmingham's reputation for trade and innovation really begins to take off in the 12th century with the expansion of a market held there by the De Birmingham family

The de Birmingham family (or de Bermingham) held the lordship of the manor of Birmingham in England for four hundred years and managed its growth from a small village into a thriving market town. They also assisted in the invasion of Ireland ...

. Around this time the Birmingham Bull Ring

The Bull Ring is a major shopping area in central Birmingham England, and has been an important feature of Birmingham since the Middle Ages, when its market was first held. Two shopping centres have been built in the area; in the 1960s, and the ...

begins to take shape, and with the town's markets there arises a necessity to produce items good enough to be sold elsewhere.

Medieval crafts in the town include textiles

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not the ...

, leather

Leather is a strong, flexible and durable material obtained from the tanning, or chemical treatment, of animal skins and hides to prevent decay. The most common leathers come from cattle, sheep, goats, equine animals, buffalo, pigs and hog ...

working and iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

working, with archaeological evidence also suggesting the presence of pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and ...

, tile

Tiles are usually thin, square or rectangular coverings manufactured from hard-wearing material such as ceramic, stone, metal, baked clay, or even glass. They are generally fixed in place in an array to cover roofs, floors, walls, edges, or ...

manufacture and probably the working of bone and horn. The following period sees the new town expand rapidly in highly favourable economic circumstances and there is archaeological evidence of small-scale industries taking place such as kiln

A kiln is a thermally insulated chamber, a type of oven, that produces temperatures sufficient to complete some process, such as hardening, drying, or chemical changes. Kilns have been used for millennia to turn objects made from clay int ...

s producing the distinctive local Deritend ware pottery.

The following decades, Birmingham becomes very productive in several trades metal working, including making small, high value items, possibly jewellery

Jewellery ( UK) or jewelry ( U.S.) consists of decorative items worn for personal adornment, such as brooches, rings, necklaces, earrings, pendants, bracelets, and cufflinks. Jewellery may be attached to the body or the clothes. From a w ...

or metal ornaments, for Master of the Knights Templar

, colors = White mantle with a red cross

, colors_label = Attire

, march =

, mascot = Two knights riding a single horse

, equipment ...

. They are sufficiently well known to be referred to without explanation as far away as London.

Birmingham's first notable literary figure is John Rogers, the compiler and editor of the 1537 ''

Birmingham's first notable literary figure is John Rogers, the compiler and editor of the 1537 ''Matthew Bible

''The Matthew Bible'', also known as ''Matthew's Version'', was first published in 1537 by John Rogers, under the pseudonym "Thomas Matthew". It combined the New Testament of William Tyndale, and as much of the Old Testament as he had been able ...

'', parts of which he also translates. This is the first complete authorised version of the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus ...

to be printed in the English language and the most influential of the early English printed Bibles, providing the basis for the later ''Great Bible

The Great Bible of 1539 was the first authorised edition of the Bible in English, authorised by King Henry VIII of England to be read aloud in the church services of the Church of England. The Great Bible was prepared by Myles Coverdale, worki ...

'' and the ''Authorized King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611, by sponsorship of K ...

''. Rogers' 1548 translation of Philip Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the L ...

's ''Weighing of the Interim'', possibly translated in Deritend

Deritend is a historic area of Birmingham, England, built around a crossing point of the River Rea. It is first mentioned in 1276. Today Deritend is usually considered to be part of Digbeth.

History

Deritend was a crossing point of the River Rea ...

, is the first book by a Birmingham man known to have been printed in England.

By the early 16th century Birmingham has already evolved into a well established arms manufacturing town, in 1538 churchman John Leialand passes through the Midlands and writes:

''I came through a praty street or ever I entered Bermingham. This street, as I remember, is called Dirty (Deritend). In it dwells smiths and cutlers and there is a brooke that divides this street from Bermingham ........ There be many smiths in the towne, that use to make knives and all manner of cutting tools, and many lorimers that make bittes, and a great many naylours, so that a great part of the towne is maintained by smiths, who have their iron and sea-coal out of Staffordshire."''Birmingham loses its

Lord of the Manor

Lord of the Manor is a title that, in Anglo-Saxon England, referred to the landholder of a rural estate. The lord enjoyed manorial rights (the rights to establish and occupy a residence, known as the manor house and demesne) as well as seig ...

in the 16th century, and the district as a whole remains an area of weak lordship throughout the following centuries. With local government remaining essentially manorial, the townspeoples' resulting high degree of economic and social freedom is to be a highly significant factor in Birmingham's subsequent development.

In 1642 the early Birmingham mathematician and astronomer

In 1642 the early Birmingham mathematician and astronomer Nathaniel Nye

Nathaniel Nye (baptised 1624 – after 1647) was an English mathematician, astronomer, cartographer and gunner.

Biography

Nye was baptised in St Martin in the Bull Ring, Birmingham on 18 April 1624, and was probably the son of a governor of t ...

publishes ''A New Almanacke and Prognostication calculated exactly for the faire and populous Towne of Birmicham in Warwickshire, where the Pole is elevated above the Horizon 52 degrees and 38 minutes, and may serve for any part of this Kingdome''.

Birmingham's principal tradesmen during the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

were the smiths, who were called upon to manufacture over 15,000 sword blades, these are supplied to Parliamentarian forces only. One of the town's leading minds, 'Nathaniel Nye' is recorded as testing a Birmingham cannon in 1643. Nye also experimented with a saker

Saker may refer to:

* Saker falcon (''Falco cherrug''), a species of falcon

* Saker (cannon), a type of cannon

* Saker Baptist College, an all-girls secondary school in Limbe, Cameroon

* Grupo Saker-Ti, a Guatemalan writers group formed in 1947

* ...

in Deritend

Deritend is a historic area of Birmingham, England, built around a crossing point of the River Rea. It is first mentioned in 1276. Today Deritend is usually considered to be part of Digbeth.

History

Deritend was a crossing point of the River Rea ...

in 1645. From 1645 he became the master gunner to the Parliamentarian garrison at Evesham

Evesham () is a market town and parish in the Wychavon district of Worcestershire, in the West Midlands region of England. It is located roughly equidistant between Worcester, Cheltenham and Stratford-upon-Avon. It lies within the Vale of Eves ...

and in 1646 he successfully directs the artillery at the Siege of Worcester, detailing his experiences and in his 1647 book ''The Art of Gunnery'', believing that war is as much a science as an art.

The earliest known clock makers in the town arrived from London in 1667. Between 1770 and 1870 there are over 700 clock and watch makers in the town.

In 1689 Sir Richard Newdigate, one of the new, local Newdigate baronets, approaches manufacturers in the town with the notion of supplying the British Government with

The earliest known clock makers in the town arrived from London in 1667. Between 1770 and 1870 there are over 700 clock and watch makers in the town.

In 1689 Sir Richard Newdigate, one of the new, local Newdigate baronets, approaches manufacturers in the town with the notion of supplying the British Government with small arms

A firearm is any type of gun designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see Legal definitions).

The first firearms originated in 10th-century China, when bamboo tubes ...

. It is stressed that they would need to be of high enough calibre to equal the small arms that were being imported from abroad. After a successful trial order in 1692, the Government places its first contract. On 5 January 1693, the "Officers of Ordnance" chooses five local firearms manufacturers to initially produce 200 " snaphance musquets" per month over the period of one year, paying 17 shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence ...

s per musket, plus 3 shillings per hundredweight

The hundredweight (abbreviation: cwt), formerly also known as the centum weight or quintal, is a British imperial and US customary unit of weight or mass. Its value differs between the US and British imperial systems. The two values are disti ...

for delivery to London. During the 18th century, Birmingham became the leading supplier of guns for the expanding British Empire.

18th century

1722: Richard Baddeley, ironmonger, patents a method for "casting wheel streaks and box irons". 1727: Birmingham is becoming a hot-bed of creative activity and local businessman and booksellerThomas Warren

Thomas Warren (fl. 1727–1767) was an English bookseller, printer, publisher and businessman.

Warren was an influential figure in Birmingham at a time when it was a hotbed of creative activity, opening a bookshop in High Street, Birmingham arou ...

opens a bookshop in the Birmingham's High Street. Warren is an influential figure in Birmingham at this time.

1732: The '' Birmingham Journal'' is founded and published from Thomas Warren's book store. This is possibly Birmingham's first weekly

1732: The '' Birmingham Journal'' is founded and published from Thomas Warren's book store. This is possibly Birmingham's first weekly newspaper

A newspaper is a periodical publication containing written information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background.

Newspapers can cover a wide variety of fields such as politics, business, spor ...

; one of its contributors is the very notable Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

of nearby Lichfield

Lichfield () is a cathedral city and civil parish in Staffordshire, England. Lichfield is situated roughly south-east of the county town of Stafford, south-east of Rugeley, north-east of Walsall, north-west of Tamworth and south-west o ...

.

1733: Thomas Warren edits and publishes Samuel Johnson's first original writing—a translation of Jerónimo Lobo's Voyage to Abyssinia. Johnson works for the Journal while he lodges with Warren. Johnson later moves on to greater things and James Boswell

James Boswell, 9th Laird of Auchinleck (; 29 October 1740 ( N.S.) – 19 May 1795), was a Scottish biographer, diarist, and lawyer, born in Edinburgh. He is best known for his biography of his friend and older contemporary the English writer ...

writes of Johnson's life: "After nine years of work, Johnson's ''A Dictionary of the English Language

''A Dictionary of the English Language'', sometimes published as ''Johnson's Dictionary'', was published on 15 April 1755 and written by Samuel Johnson. It is among the most influential dictionaries in the history of the English language.

T ...

'' was published in 1755; it had a far-reaching effect on Modern English and has been described as "one of the greatest single achievements of scholarship". The dictionary brings Johnson popularity and success. Until the completion of the ''Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a c ...

'' 150 years later, Johnson's dictionary is among the most influential dictionaries in the history of the English language

English is a West Germanic language of the Indo-European language family, with its earliest forms spoken by the inhabitants of early medieval England. It is named after the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated to the ...

.

1738:

1738: Lewis Paul

Lewis Paul (died 1759) was the original inventor of roller spinning, the basis of the water frame for spinning cotton in a cotton mill.

Life and work

Lewis Paul was of Huguenot descent. His father was physician to Lord Shaftesbury. He may hav ...

and John Wyatt, of Birmingham, patent the roller spinning machine and the flyer-and-bobbin system, for drawing cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

to a more even thickness, using two sets of rollers that travel at different speeds. This principle later becomes the basis of Richard Arkwright

Sir Richard Arkwright (23 December 1732 – 3 August 1792) was an English inventor and a leading entrepreneur during the early Industrial Revolution. He is credited as the driving force behind the development of the spinning frame, known as ...

's water frame

The water frame is a spinning frame that is powered by a water-wheel. Water frames in general have existed since Ancient Egypt times. Richard Arkwright, who patented the technology in 1769, designed a model for the production of cotton thread; ...

.

1741: John Wyatt, mechanic and inventor, designs and constructs a cart-weighing machine, later referred to as a compound lever

The compound lever is a simple machine operating on the premise that the resistance from one lever in a system of levers acts as effort for the next, and thus the applied force is transferred from one lever to the next. Almost all scales use som ...

weighing machine; the design works by way of levers that hold in place a platform, no matter where the weight is placed the load is transferred to a central lever. Weights attached to that lever then help in obtaining a reading of accurate weight. The simplicity, efficiency and accuracy of the weighing machine prove extremely popular across England, subsequently weighing errors are reduced to approximately one pound per ton, this remains a high standard of measurement into the mid-19th century.

1741: The Upper Priory Cotton Mill

The Upper Priory Cotton Mill, opened in Birmingham, England in the summer of 1741, was the world's first mechanised cotton-spinning factory or cotton mill. Established by Lewis Paul and John Wyatt in a former warehouse in the Upper Priory, near ...

opens as the world's first mechanised cotton-spinning factory. It is financed by local businessman Thomas Warren

Thomas Warren (fl. 1727–1767) was an English bookseller, printer, publisher and businessman.

Warren was an influential figure in Birmingham at a time when it was a hotbed of creative activity, opening a bookshop in High Street, Birmingham arou ...

, and opened by John Wyatt and Lewis Paul.

1742: John Baskerville

John Baskerville (baptised 28 January 1707 – 8 January 1775) was an English businessman, in areas including japanning and papier-mâché, but he is best remembered as a printer and type designer. He was also responsible for inventing "w ...

takes out a patent for making metal

A metal (from ancient Greek, Greek μέταλλον ''métallon'', "mine, quarry, metal") is a material that, when freshly prepared, polished, or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electrical resistivity and conductivity, e ...

mouldings, rolling, grinding and japanning

Japanning is a type of finish that originated as a European imitation of East Asian lacquerwork. It was first used on furniture, but was later much used on small items in metal. The word originated in the 17th century. American work, with ...

metal plates by use of weights, rollers and pickling, which Baskerville uses over the more traditional method of employing screws. This is the first patent for making metal mouldings by passing them through rolls of a certain profile.

1743: A factory opens in

1743: A factory opens in Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England ...

, fifty spindles turned on five of Paul and Wyatt's machines proving more successful than their first mill. This operates until 1764.

1746: The Colmore family release land on what is later to be known as the Jewellery Quarter to help satisfy the demands of an increasing population.

1746: A sulphuric acid

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid ( Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen and hydrogen, with the molecular for ...

factory is set up at Steelhouse Lane to use the lead chamber process invented by its co-founder John Roebuck. Roebuck and local businessman Samuel Garbett later relocate to Prestonpans

Prestonpans ( gd, Baile an t-Sagairt, Scots language, Scots: ''The Pans'') is a small mining town, situated approximately eight miles east of Edinburgh, Scotland, in the Council area of East Lothian. The population as of is. It is near the si ...

in Scotland, taking with them several skilled men from the Birmingham factory. It is here in 1762 where Roebuck takes out a patent for making malleable iron

Malleable iron is cast as white iron, the structure being a metastable carbide in a pearlitic matrix. Through an annealing heat treatment, the brittle structure as first cast is transformed into the malleable form. Carbon agglomerates into sma ...

.

1748: Lewis Paul invents the hand driven carding

Carding is a mechanical process that disentangles, cleans and intermixes fibres to produce a continuous web or sliver suitable for subsequent processing. This is achieved by passing the fibres between differentially moving surfaces covered with ...

machine. A coat of wire slips are placed around a card, which is then wrapped around a cylinder. Lewis's invention is later developed and improved by Richard Arkwright and Samuel Crompton

Samuel Crompton (3 December 1753 – 26 June 1827) was an English inventor and pioneer of the spinning industry. Building on the work of James Hargreaves and Richard Arkwright he invented the spinning mule, a machine that revolutionised th ...

, although this comes about under great suspicion after a fire at Daniel Bourn's factory in Leominster

Leominster ( ) is a market town in Herefordshire, England, at the confluence of the River Lugg and its tributary the River Kenwater. The town is north of Hereford and south of Ludlow in Shropshire. With a population of 11,700, Leominster i ...

that specifically uses Paul and Wyatt's spindles. Bourn produces a similar patent in the same year.

1757: Rev John Dyer of Northampton recognises the importance of the Paul and Wyatt cotton spinning machine in poem:

:A circular machine, of new design

:In conic shape: it draws and spins a thread

:Without the tedious toil of needless hands.

:A wheel, invisible, beneath the floor,

:To ev'ry member of th' harmonius frame,

:Gives necessary motion. One, intent,

:O'erlooks the work; the carded wool, he says,

:Is smoothly lapp'd around those cylinders,

:Which, gently turning, yield it to yon' cirque

:Of upright spindles, which with rapid whirl

:Spin out, in long extent, an even twine.

:A circular machine, of new design

:In conic shape: it draws and spins a thread

:Without the tedious toil of needless hands.

:A wheel, invisible, beneath the floor,

:To ev'ry member of th' harmonius frame,

:Gives necessary motion. One, intent,

:O'erlooks the work; the carded wool, he says,

:Is smoothly lapp'd around those cylinders,

:Which, gently turning, yield it to yon' cirque

:Of upright spindles, which with rapid whirl

:Spin out, in long extent, an even twine.

1757: Baskerville serif typeface is designed by

1757: Baskerville serif typeface is designed by John Baskerville

John Baskerville (baptised 28 January 1707 – 8 January 1775) was an English businessman, in areas including japanning and papier-mâché, but he is best remembered as a printer and type designer. He was also responsible for inventing "w ...

(1706–1775) in Birmingham, England. Baskerville is classified as a transitional typeface, positioned between the old style typefaces of William Caslon

Caslon is the name given to serif typefaces designed by William Caslon I (c. 1692–1766) in London, or inspired by his work.

Caslon worked as an engraver of punches, the masters used to stamp the moulds or matrices used to cast metal ty ...

, and the modern styles of Giambattista Bodoni

Bodoni is the name given to the serif typefaces first designed by Giambattista Bodoni (1740–1813) in the late eighteenth century and frequently revived since. Bodoni's typefaces are classified as Didone or modern. Bodoni followed the ideas o ...

and Firmin Didot Didot may refer to:

* Didot family, family of French printers, punch-cutters and publishers that flourished mainly in the 18th century

* Didot (typeface), a group of serif typefaces

* the Didot Point (typography)

In typography, the point is the ...

.

1758: Paul and Wyatt improve their Roller Spinning machine and take out a second patent. Richard Arkwright later uses this as the model for his water frame

The water frame is a spinning frame that is powered by a water-wheel. Water frames in general have existed since Ancient Egypt times. Richard Arkwright, who patented the technology in 1769, designed a model for the production of cotton thread; ...

.

1758: Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading int ...

first travels to Birmingham "to improve and increase Acquaintance among Persons of Influence", and later returns in 1760 to conduct experiments with Boulton on electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as describe ...

and sound

In physics, sound is a vibration that propagates as an acoustic wave, through a transmission medium such as a gas, liquid or solid.

In human physiology and psychology, sound is the ''reception'' of such waves and their ''perception'' by ...

. Franklin remains a common link among many of the early Lunar Society

The Lunar Society of Birmingham was a British dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the Midlands Enlightenment, including industrialists, natural philosophers and intellectuals, who met regularly between 1765 and 1813 ...

members.

1759: A patent is granted to Thomas Blockley ( locksmith), for rolling iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

into different forms and making (metal) wheel tyres.

1762: Matthew Boulton

Matthew Boulton (; 3 September 172817 August 1809) was an English manufacturer and business partner of Scottish engineer James Watt. In the final quarter of the 18th century, the partnership installed hundreds of Boulton & Watt steam engin ...

opens the Soho Foundry

Soho Foundry is a factory created in 1775 by Matthew Boulton and James Watt and their sons Matthew Robinson Boulton and James Watt Jr. at Smethwick, West Midlands, England (), for the manufacture of steam engines. Now owned by Avery Weigh-Tr ...

engineering works, Handsworth; his partnership with Scottish engineer James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was ...

makes the steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be ...

into the power plant for the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

. The term "horsepower

Horsepower (hp) is a unit of measurement of power, or the rate at which work is done, usually in reference to the output of engines or motors. There are many different standards and types of horsepower. Two common definitions used today are t ...

" is coined by Watt.

Midlands Enlightenment

The Midlands Enlightenment, also known as the West Midlands Enlightenment or the Birmingham Enlightenment, was a scientific, economic, political, cultural and legal manifestation of the Age of Enlightenment that developed in Birmingham and the wide ...

, including industrialists, natural philosophers and intellectuals, who meet regularly until 1813 in Birmingham. A paper read at the Science Museum in London in 1963 claims that "of all the provincial philosophical societies it was the most important, perhaps because it was not merely provincial. All the world came to Soho to meet Boulton, Watt or Small, who were acquainted with the leading men of Science throughout Europe and America." The Midlands Enlightenment dominates the

experience of the Enlightenment within England and its leading thinkers have international influence. In particular, it forms a pivotal link between the earlier Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transforme ...

and the later Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, facilitating the exchange of ideas between experimental science, polite culture and practical technology that enables the technological preconditions for rapid economic growth to be attained.

1767: A number of prominent Birmingham businessmen, including Matthew Boulton and others from the Lunar Society, hold a public meeting in the White Swan, High Street,''Smethwick and the BCN'', Malcolm D. Freeman, 2003, Sandwell MBC and Smethwick Heritage Centre Trust to consider the possibility of building a canal from Birmingham to the

1767: A number of prominent Birmingham businessmen, including Matthew Boulton and others from the Lunar Society, hold a public meeting in the White Swan, High Street,''Smethwick and the BCN'', Malcolm D. Freeman, 2003, Sandwell MBC and Smethwick Heritage Centre Trust to consider the possibility of building a canal from Birmingham to the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal

The Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal is a navigable narrow canal in Staffordshire and Worcestershire in the English Midlands. It is long, linking the River Severn at Stourport in Worcestershire with the Trent and Mersey Canal at Haywood ...

near Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton () is a city, metropolitan borough and administrative centre in the West Midlands, England. The population size has increased by 5.7%, from around 249,500 in 2011 to 263,700 in 2021. People from the city are called "Wulfrunians ...

, taking in the coalfields of the Black Country

The Black Country is an area of the West Midlands county, England covering most of the Metropolitan Boroughs of Dudley, Sandwell and Walsall. Dudley and Tipton are generally considered to be the centre. It became industrialised during its ...

. They commission the canal engineer James Brindley

James Brindley (1716 – 27 September 1772) was an English engineer. He was born in Tunstead, Derbyshire, and lived much of his life in Leek, Staffordshire, becoming one of the most notable engineers of the 18th century.

Early life

Born i ...

to propose a route. Brindley comes back with a largely level route via Smethwick

Smethwick () is an industrial town in Sandwell, West Midlands, England. It lies west of Birmingham city centre. Historically it was in Staffordshire.

In 2019, the ward of Smethwick had an estimated population of 15,246, while the wider b ...

, Oldbury, Tipton

Tipton is an industrial town in the West Midlands in England with a population of around 38,777 at the 2011 UK Census. It is located northwest of Birmingham.

Tipton was once one of the most heavily industrialised towns in the Black Country, w ...

, Bilston

Bilston is a market town, ward, and civil parish located in Wolverhampton, West Midlands, England. It is close to the borders of Sandwell and Walsall. The nearest towns are Darlaston, Wednesbury, and Willenhall. Historically in Staffordshi ...

and Wolverhampton to Aldersley. This kick-starts what is to become the Birmingham Canal Navigations

Birmingham Canal Navigations (BCN) is a network of canals connecting Birmingham, Wolverhampton, and the eastern part of the Black Country. The BCN is connected to the rest of the English canal system at several junctions. It was owned and opera ...

.

1770: James Watt applies the first screw propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upo ...

to an early steam engine at his Birmingham works, thus beginning the use of a hydrodynamic screw for propulsion.

1775: Ketley's Building Society

Ketley's Building Society, founded in Birmingham, England, in 1775, was the world's first building society.

The society was formed by Richard Ketley, the landlord at the Golden Cross inn at 60 Snow Hill. Taverns and coffeehouses were important me ...

is founded and becomes the world's first building society

A building society is a financial institution owned by its members as a mutual organization. Building societies offer banking and related financial services, especially savings and mortgage lending. Building societies exist in the United Ki ...

. Midland Bank

Midland Bank Plc was one of the Big Four banking groups in the United Kingdom for most of the 20th century. It is now part of HSBC. The bank was founded as the Birmingham and Midland Bank in Union Street, Birmingham, England in August 1836. It ...

(now owned by HSBC

HSBC Holdings plc is a British multinational universal bank and financial services holding company. It is the largest bank in Europe by total assets ahead of BNP Paribas, with US$2.953 trillion as of December 2021. In 2021, HSBC had $10.8 tr ...

) and Lloyds Bank

Lloyds Bank plc is a British retail and commercial bank with branches across England and Wales. It has traditionally been considered one of the " Big Four" clearing banks. Lloyds Bank is the largest retail bank in Britain, and has an exte ...

are also founded in Birmingham.

1777: Boulton and Watt build ' Old Bess', as described by the London science museums 'an engine that stands at a crossroads in history'.

1779: James Keir takes out a patent for a compound metal that is capable of being forged when hot or cold more fit for the making of bolts, nails, and sheathing for ships prior to anything before. This metal uses the same compounds and similar quantities of metals as the patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A ...

of Muntz metal, which appears at the same time.

1779: Matthew Wasbrough designs and builds the Pickard Engine (first crank engine) for James Pickard of Snow Hill, this is defined as 'the first atmospheric engine in the world to directly achieve rotary motion by the use of a crank and

1779: Matthew Wasbrough designs and builds the Pickard Engine (first crank engine) for James Pickard of Snow Hill, this is defined as 'the first atmospheric engine in the world to directly achieve rotary motion by the use of a crank and flywheel

A flywheel is a mechanical device which uses the conservation of angular momentum to store rotational energy; a form of kinetic energy proportional to the product of its moment of inertia and the square of its rotational speed. In particular, as ...

.'

1779: James Watt patents a copying press or 'letter copying machine' to deal with the mass of paper work at his business; he also invents an ink to work with it. This is the first widely used copy machine for offices and is a commercial success, being used for over a century. This letter copying press is considered to be the original photocopier

A photocopier (also called copier or copy machine, and formerly Xerox machine, the generic trademark) is a machine that makes copies of documents and other visual images onto paper or plastic film quickly and cheaply. Most modern photocopier ...

.

water pump

A pump is a device that moves fluids (liquids or gases), or sometimes slurries, by mechanical action, typically converted from electrical energy into hydraulic energy. Pumps can be classified into three major groups according to the method they ...

s but the new engine

An engine or motor is a machine designed to convert one or more forms of energy into mechanical energy.