Savonarola on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Girolamo Savonarola, OP (, , ; 21 September 1452 – 23 May 1498) or Jerome Savonarola was an Italian Dominican

Savonarola was born on 21 September 1452 in Ferrara to Niccolò di Michele and Elena. His father, Niccolò, was born in Ferrara to a family originally from

Savonarola was born on 21 September 1452 in Ferrara to Niccolò di Michele and Elena. His father, Niccolò, was born in Ferrara to a family originally from

Savonarola preached on the

Savonarola preached on the

With Savonarola's advice and support (as a non-citizen and cleric he was ineligible to hold office), a Savonarolan political "party", dubbed "the Frateschi", took shape and steered the friar's program through the councils. The oligarchs most compromised by their service to the Medici were barred from office. A new constitution enfranchised the artisan class, opened minor civic offices to selection by lot, and granted every citizen in good standing the right to a vote in a new parliament, the Consiglio Maggiore, or Great Council. At Savonarola's urging, the Frateschi government, after months of debate, passed a "Law of Appeal" to limit the longtime practice of using exile and capital punishment as factional weapons. Savonarola declared a new era of "universal peace". On 13 January 1495 he preached his great Renovation Sermon to a huge audience in the cathedral, recalling that he had begun prophesying in Florence four years earlier, although the divine light had come to him "more than fifteen, maybe twenty years ago". He now claimed that he had predicted the deaths of

With Savonarola's advice and support (as a non-citizen and cleric he was ineligible to hold office), a Savonarolan political "party", dubbed "the Frateschi", took shape and steered the friar's program through the councils. The oligarchs most compromised by their service to the Medici were barred from office. A new constitution enfranchised the artisan class, opened minor civic offices to selection by lot, and granted every citizen in good standing the right to a vote in a new parliament, the Consiglio Maggiore, or Great Council. At Savonarola's urging, the Frateschi government, after months of debate, passed a "Law of Appeal" to limit the longtime practice of using exile and capital punishment as factional weapons. Savonarola declared a new era of "universal peace". On 13 January 1495 he preached his great Renovation Sermon to a huge audience in the cathedral, recalling that he had begun prophesying in Florence four years earlier, although the divine light had come to him "more than fifteen, maybe twenty years ago". He now claimed that he had predicted the deaths of

On 12 May 1497, Pope Alexander VI

On 12 May 1497, Pope Alexander VI

Savonarolan religious ideas found a reception elsewhere. In Germany and Switzerland the early Protestant reformers, most notably

Savonarolan religious ideas found a reception elsewhere. In Germany and Switzerland the early Protestant reformers, most notably

Almost thirty volumes of Savonarola's sermons and writings have so far been published in the ''Edizione nazionale delle Opere di Girolamo Savonarola'' (Rome, Angelo Belardetti, 1953 to the present). For editions of the 15th and 16th centuries see ''Catalogo delle edizioni di Girolamo Savonarola (secc. xv–xvi)'' ed. P. Scapecchi (Florence, 1998, ).

* ''Prison Meditations on Psalms 51 and 31'' ed. John Patrick Donnelly, S.J. ()

* The Compendium of Revelations in Bernard McGinn ed. ''Apocalyptic Spirituality: Treatises and Letters of Lactantius,

Almost thirty volumes of Savonarola's sermons and writings have so far been published in the ''Edizione nazionale delle Opere di Girolamo Savonarola'' (Rome, Angelo Belardetti, 1953 to the present). For editions of the 15th and 16th centuries see ''Catalogo delle edizioni di Girolamo Savonarola (secc. xv–xvi)'' ed. P. Scapecchi (Florence, 1998, ).

* ''Prison Meditations on Psalms 51 and 31'' ed. John Patrick Donnelly, S.J. ()

* The Compendium of Revelations in Bernard McGinn ed. ''Apocalyptic Spirituality: Treatises and Letters of Lactantius,

Catholic Encyclopedia entry on Girolamo Savonarola

''Predica dell'arte del bene morire''

From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the

''Savonarola's Visions'', documentary about Girolamo Savonarola

{{DEFAULTSORT:Savonarola, Girolamo Executed Roman Catholic priests Italian Roman Catholics Italian torture victims Italian Dominicans People excommunicated by the Catholic Church People executed by the Papal States by burning People executed for heresy Religious leaders from Ferrara Rulers of Florence University of Ferrara alumni 1452 births 1498 deaths 15th-century Italian Roman Catholic priests Proto-Protestants

friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the ...

from Ferrara and preacher active in Renaissance Florence

Florence ( it, Firenze) weathered the decline of the Western Roman Empire to emerge as a financial hub of Europe, home to several banks including that of the politically powerful Medici family. The city's wealth supported the development of a ...

. He was known for his prophecies of civic glory, the destruction of secular art and culture, and his calls for Christian renewal. He denounced clerical corruption, despotic rule, and the exploitation of the poor.

In September 1494, when Charles VIII of France invaded Italy and threatened Florence, such prophecies seemed on the verge of fulfilment. While Savonarola intervened with the French king, the Florentines expelled the ruling Medicis and, at the friar's urging, established a "popular" republic. Declaring that Florence would be the New Jerusalem, the world centre of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

and "richer, more powerful, more glorious than ever", he instituted an extreme puritanical campaign, enlisting the active help of Florentine youth.

In 1495 when Florence refused to join Pope Alexander VI's Holy League against the French, the Vatican summoned Savonarola to Rome. He disobeyed and further defied the pope by preaching under a ban, highlighting his campaign for reform with processions, bonfires of the vanities, and pious theatricals. In retaliation, the pope excommunicated him in May 1497 and threatened to place Florence under an interdict

In Catholic canon law, an interdict () is an ecclesiastical censure, or ban that prohibits persons, certain active Church individuals or groups from participating in certain rites, or that the rites and services of the church are banished from ...

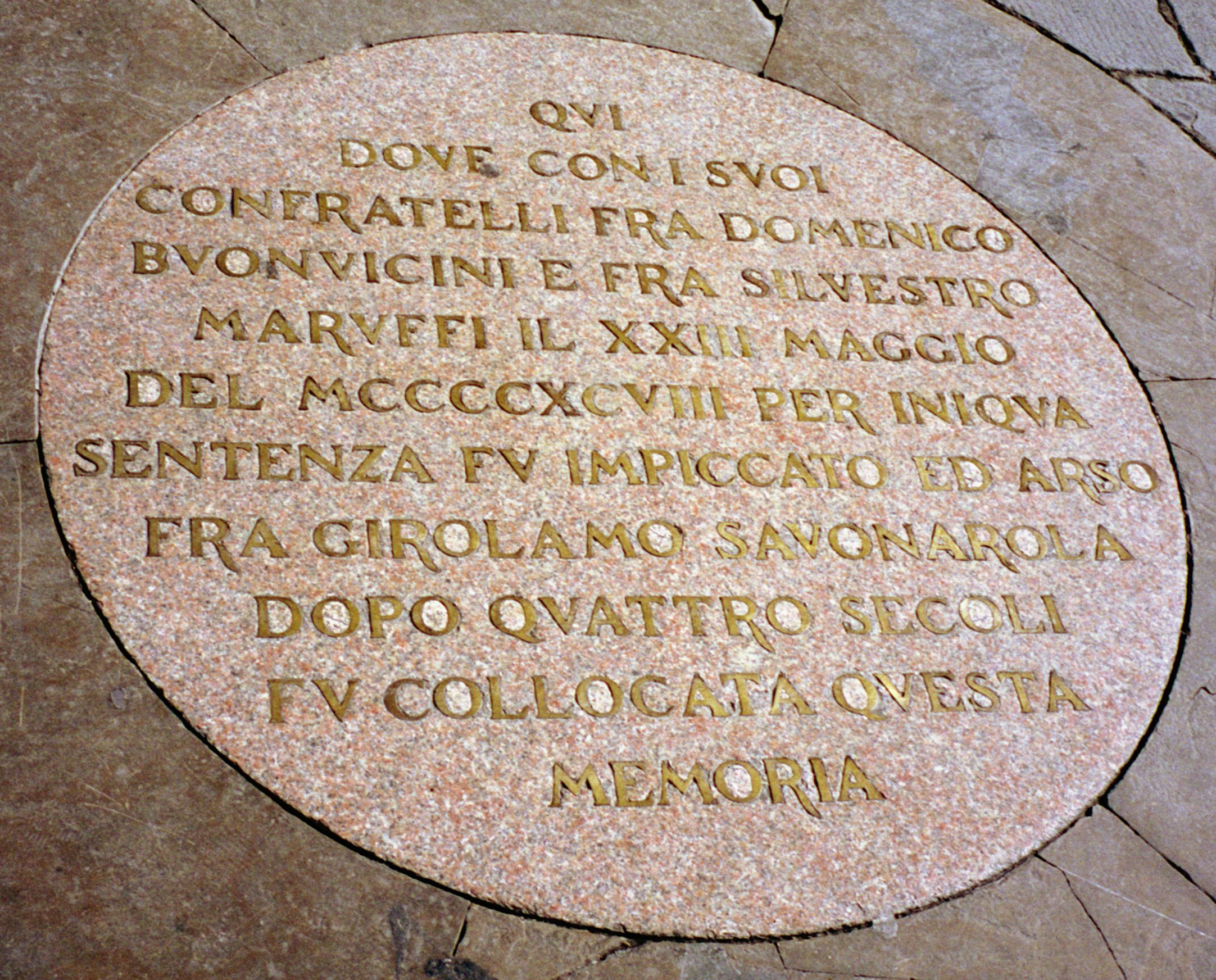

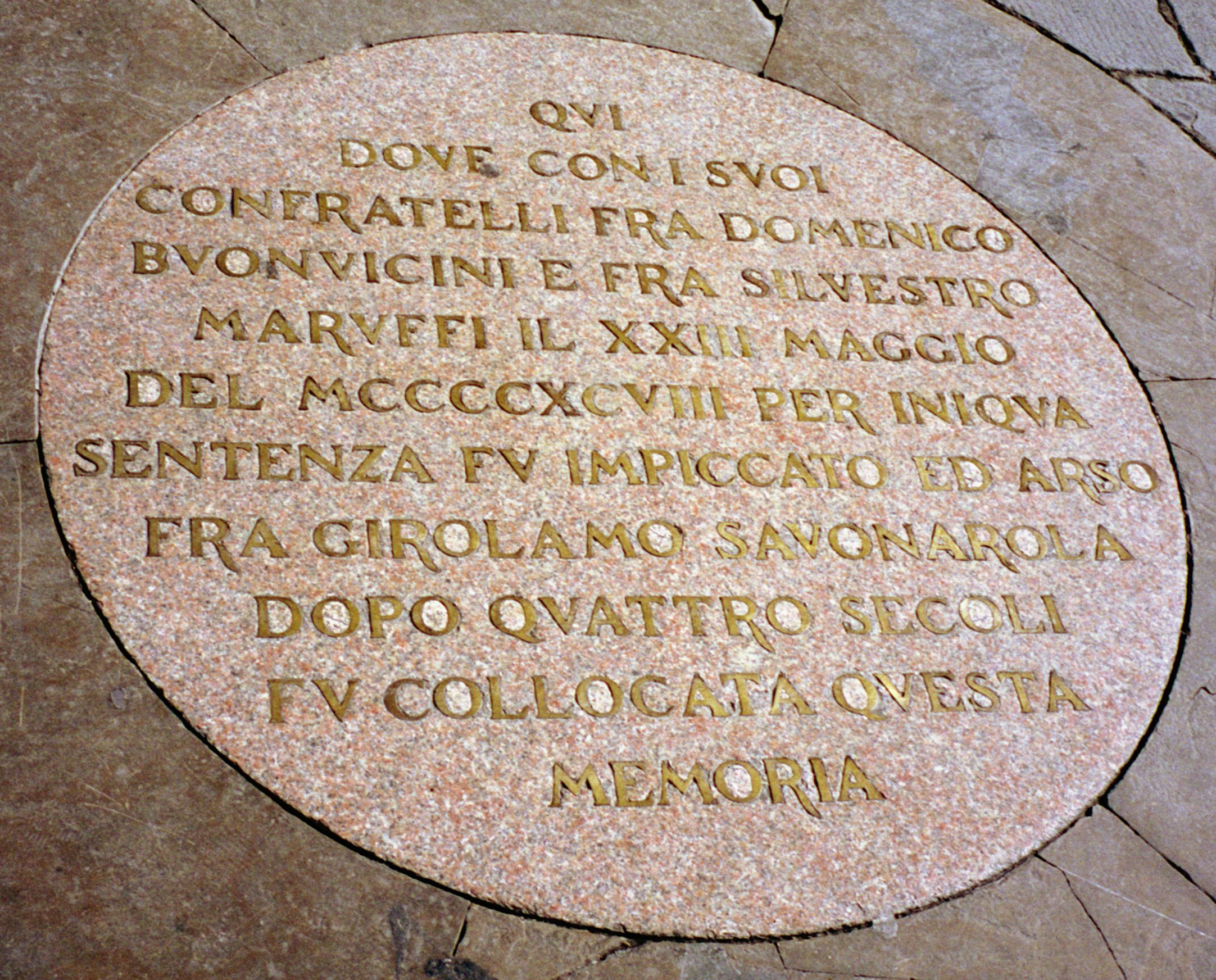

. A trial by fire proposed by a rival Florentine preacher in April 1498 to test Savonarola's divine mandate turned into a fiasco, and popular opinion turned against him. Savonarola and two of his supporting friars were imprisoned. On 23 May 1498, Church and civil authorities condemned, hanged, and burned the three friars in the main square of Florence.

Savonarola's devotees, the Piagnoni, kept his cause of republican freedom and religious reform alive well into the following century, although the Medici—restored to power in 1512 with the help of the papacy—eventually broke the movement. Some Protestants, including Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

himself, consider Savonarola to be a vital precursor to the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

.

Early years

Savonarola was born on 21 September 1452 in Ferrara to Niccolò di Michele and Elena. His father, Niccolò, was born in Ferrara to a family originally from

Savonarola was born on 21 September 1452 in Ferrara to Niccolò di Michele and Elena. His father, Niccolò, was born in Ferrara to a family originally from Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

; his mother, Elena, claimed a lineage from the Bonacossi family of Mantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and '' comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture. In 2017, it was named as the Eur ...

. She and Niccolò had seven children, of whom Girolamo was third. His grandfather, Michele Savonarola, a noted and successful physician and polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

, oversaw Girolamo's education. The family amassed a great deal of wealth from Michele's medical practice.

After his grandfather's death in 1468 Savonarola may have attended the public school run by Battista Guarino, son of Guarino da Verona

Guarino Veronese or Guarino da Verona (1374 – 14 December 1460) was an Italian classical scholar, humanist, and translator of ancient Greek texts during the Renaissance. In the republics of Florence and Venice he studied under Manuel Chrysol ...

, where he would have received his introduction to the classics as well as to the poetry and writings of Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited ...

, father of Renaissance humanism

Renaissance humanism was a revival in the study of classical antiquity, at first in Italy and then spreading across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term ''humanist'' ( it, umanista) referred to teache ...

. Earning an arts degree at the University of Ferrara

The University of Ferrara ( it, Università degli Studi di Ferrara) is the main university of the city of Ferrara in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy. In the years prior to the First World War the University of Ferrara, with more than 5 ...

, he prepared to enter medical school, following in his grandfather's footsteps. At some point, however, he abandoned his career intentions.

In his early poems he expresses his preoccupation with the state of the Church and of the world. He began to write poetry of an apocalyptic bent, notably "On the Ruin of the World" (1472) and "On the Ruin of the Church" (1475), in which he singled out the papal court at Rome for special obloquy. About the same time he seems to have been thinking about a life in religion. As he later told his biographer, a sermon he heard by a preacher in Faenza persuaded him to abandon the world. Most of his biographers reject or ignore the account of his younger brother and follower, Maurelio (later fra Mauro), that in his youth Girolamo had been spurned by a neighbour, Laudomia Strozzi, to whom he had proposed marriage. True or not, in a letter he wrote to his father when he left home to join the Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers ( la, Ordo Praedicatorum) abbreviated OP, also known as the Dominicans, is a Catholic mendicant order of Pontifical Right for men founded in Toulouse, France, by the Spanish priest, saint and mystic Dominic of ...

he hints at being troubled by desires of the flesh. There is also a story that on the eve of his departure he dreamed that he was cleansed of such thoughts by a shower of icy water, which prepared him for the ascetic life. In the unfinished treatise he left behind, later called "De contemptu Mundi" or "On Contempt for the World", he calls upon readers to fly from this world of adultery, sodomy, murder and envy.

Savonarola studied Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North A ...

and Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wit ...

. He also studied the scriptures and even memorized parts.

On 25 April 1475 Girolamo Savonarola went to Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language, Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 1 ...

, where he knocked on the door of the Friary of San Domenico, of the Order of Friars Preacher, and asked to be admitted. As he told his father in his farewell letter, he wanted to become a knight of Christ.

Friar

In the convent, Savonarola took the vow of obedience proper to his order, and after a year was ordained to the priesthood. He studied Scripture, logic, Aristotelian philosophy andThomistic

Thomism is the philosophical and theological school that arose as a legacy of the work

Work may refer to:

* Work (human activity), intentional activity people perform to support themselves, others, or the community

** Manual labour, physica ...

theology in the Dominican studium, practised preaching to his fellow friars, and engaged in disputations. He then matriculated in the theological faculty to prepare for an advanced degree. Even as he continued to write devotional works and to deepen his spiritual life, he was openly critical of what he perceived as the decline in convent austerity. In 1478 his studies were interrupted when he was sent to the Dominican priory of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Ferrara as assistant master of novices. The assignment might have been a normal, temporary break from the academic routine, but in Savonarola's case, it was a turning point. One explanation is that he had alienated certain of his superiors, particularly fra Vincenzo Bandelli, or Bandello, a professor at the studium and future master general of the Dominicans, who resented the young friar's opposition to modifying the Order's rules against the ownership of property. In 1482, instead of returning to Bologna to resume his studies, Savonarola was assigned as lector, or teacher, in the Convent of San Marco in Florence.

In San Marco, fra Girolamo (Savonarola) taught logic to the novices, wrote instructional manuals on ethics, logic, philosophy and government, composed devotional works, and prepared his sermons for local congregations. As he recorded in his notes, his preaching was not altogether successful. Florentines were put off by his foreign-sounding Ferrarese speech, his strident voice and (especially to those who valued humanist rhetoric) his inelegant style.

While waiting for a friend in the Convent of San Giorgio, he was studying Scripture when he suddenly conceived "about seven reasons" why the Church was about to be scourged and renewed. He broached these apocalyptic themes in San Gimignano, where he went as Lenten preacher in 1485 and again in 1486, but a year later, when he left San Marco for a new assignment, he had said nothing of his "San Giorgio revelations" in Florence.

Preacher

For the next several years Savonarola lived as an itinerant preacher with a message of repentance and reform in the cities and convents of north Italy. As his letters to his mother and his writings show, his confidence and sense of mission grew along with his widening reputation. In 1490, he was reassigned to San Marco. It seems that this was due to the initiative of the humanist philosopher-prince,Giovanni Pico della Mirandola

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (24 February 1463 – 17 November 1494) was an Italian Renaissance nobleman and philosopher. He is famed for the events of 1486, when, at the age of 23, he proposed to defend 900 theses on religion, philosophy, ...

, who had heard Savonarola in a formal disputation in Reggio Emilia and been impressed with his learning and piety. Pico was in trouble with the Church for some of his unorthodox philosophical ideas (the famous "900 theses") and was living under the protection of Lorenzo the Magnificent

Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici (; 1 January 1449 – 8 April 1492) was an Italian statesman, banker, ''de facto'' ruler of the Florentine Republic and the most powerful and enthusiastic patron of Renaissance culture in Italy. Also known as Lorenzo ...

, the Medici ''de facto'' ruler of Florence. To have Savonarola beside him as a spiritual counsellor, he persuaded Lorenzo that the friar would bring prestige to the convent of San Marco and its Medici patrons. After some delay, apparently due to the interference of his former professor fra Vincenzo Bandelli, now Vicar General of the Order, Lorenzo succeeded in bringing Savonarola back to Florence, where he arrived in May or June of that year.

Prophet

Savonarola preached on the

Savonarola preached on the First Epistle of John

The First Epistle of John is the first of the Johannine epistles of the New Testament, and the fourth of the catholic epistles. There is no scholarly consensus as to the authorship of the Johannine works. The author of the First Epistle is ter ...

and on the Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation is the final book of the New Testament (and consequently the final book of the Christian Bible). Its title is derived from the first word of the Koine Greek text: , meaning "unveiling" or "revelation". The Book of ...

, drawing such large crowds that he eventually moved to the cathedral. Without mentioning names, he made pointed allusions to tyrants who usurped the freedom of the people, and he excoriated their allies, the rich and powerful who neglected and exploited the poor. Complaining of the evil lives of a corrupt clergy, he now called for repentance and renewal before the arrival of a divine scourge. Scoffers dismissed him as an over-excited zealot and "preacher of the desperate" and sneered at his growing band of followers as ''Piagnoni''—"Weepers" or "Wailers", an epithet they adopted. In 1492 Savonarola warned of "the Sword of the Lord over the earth quickly and soon" and envisioned terrible tribulations to Rome. Around 1493 (these sermons have not survived) he began to prophesy that a New Cyrus was coming over the mountains to begin the renewal of the Church.

In September 1494 King Charles VIII of France crossed the Alps with a formidable army, throwing Italy into political chaos. Many viewed the arrival of King Charles as proof of Savonarola's gift of prophecy. Charles, however, advanced on Florence, sacking Tuscan strongholds and threatening to punish the city for refusing to support his expedition. As the populace took to the streets to expel Piero the Unfortunate, Lorenzo de' Medici's son and successor, Savonarola led a delegation to the camp of the French king in mid-November 1494. He pressed Charles to spare Florence and enjoined him to take up his divinely appointed role as the reformer of the Church. After a short, tense occupation of the city, and another intervention by fra Girolamo (as well as the promise of a huge subsidy), the French resumed their journey southward on 28 November 1494. Savonarola now declared that by answering his call to penitence, the Florentines had begun to build a new Ark of Noah which had saved them from the waters of the divine flood. Even more sensational was the message in his sermon of 10 December:

I announce this good news to the city, that Florence will be more glorious, richer, more powerful than she has ever been; First, glorious in the sight of God as well as of men: and you, O Florence will be the reformation of all Italy, and from here the renewal will begin and spread everywhere, because this is the navel of Italy. Your counsels will reform all by the light and grace that God will give you. Second, O Florence, you will have innumerable riches, and God will multiply all things for you. Third, you will spread your empire, and thus you will have power temporal and spiritual.This astounding guarantee may have been an allusion to the traditional patriotic myth of Florence as the new Rome, which Savonarola would have encountered in his readings in Florentine history. In any case, it encompassed both temporal power and spiritual leadership.

Reformer

With Savonarola's advice and support (as a non-citizen and cleric he was ineligible to hold office), a Savonarolan political "party", dubbed "the Frateschi", took shape and steered the friar's program through the councils. The oligarchs most compromised by their service to the Medici were barred from office. A new constitution enfranchised the artisan class, opened minor civic offices to selection by lot, and granted every citizen in good standing the right to a vote in a new parliament, the Consiglio Maggiore, or Great Council. At Savonarola's urging, the Frateschi government, after months of debate, passed a "Law of Appeal" to limit the longtime practice of using exile and capital punishment as factional weapons. Savonarola declared a new era of "universal peace". On 13 January 1495 he preached his great Renovation Sermon to a huge audience in the cathedral, recalling that he had begun prophesying in Florence four years earlier, although the divine light had come to him "more than fifteen, maybe twenty years ago". He now claimed that he had predicted the deaths of

With Savonarola's advice and support (as a non-citizen and cleric he was ineligible to hold office), a Savonarolan political "party", dubbed "the Frateschi", took shape and steered the friar's program through the councils. The oligarchs most compromised by their service to the Medici were barred from office. A new constitution enfranchised the artisan class, opened minor civic offices to selection by lot, and granted every citizen in good standing the right to a vote in a new parliament, the Consiglio Maggiore, or Great Council. At Savonarola's urging, the Frateschi government, after months of debate, passed a "Law of Appeal" to limit the longtime practice of using exile and capital punishment as factional weapons. Savonarola declared a new era of "universal peace". On 13 January 1495 he preached his great Renovation Sermon to a huge audience in the cathedral, recalling that he had begun prophesying in Florence four years earlier, although the divine light had come to him "more than fifteen, maybe twenty years ago". He now claimed that he had predicted the deaths of Lorenzo de' Medici

Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici (; 1 January 1449 – 8 April 1492) was an Italian statesman, banker, ''de facto'' ruler of the Florentine Republic and the most powerful and enthusiastic patron of Renaissance culture in Italy. Also known as Lorenzo ...

and of Pope Innocent VIII in 1492 and the coming of the sword to Italy—the invasion of King Charles of France. As he had foreseen, God had chosen Florence, "the navel of Italy", as his favourite and he repeated: if the city continued to do penance and began the work of renewal it would have riches, glory and power.

If the Florentines had any doubt that the promise of worldly power and glory had heavenly sanction, Savonarola emphasised this in a sermon of 1 April 1495, in which he described his mystical journey to the Virgin Mary in heaven. At the celestial throne Savonarola presents the Holy Mother a crown made by the Florentine people and presses her to reveal their future. Mary warns that the way will be hard both for the city and for him, but she assures him that God will fulfil his promises: Florence will be "more glorious, more powerful and richer than ever, extending its wings farther than anyone can imagine". She and her heavenly minions will protect the city against its enemies and support its alliance with the French. In the New Jerusalem that is Florence peace and unity will reign. Based on such visions, Savonarola promoted theocracy, and declared Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

the king of Florence. He saw sacred art as a tool to promote this worldview, and he was therefore only opposed to secular art, which he saw as worthless and potentially damaging.

Buoyed by liberation and prophetic promise, the Florentines embraced Savonarola's campaign to rid the city of "vice". At his repeated insistence, new laws were passed against "sodomy" (which included male and female same-sex relations), adultery, public drunkenness, and other moral transgressions, while his lieutenant Fra Silvestro Maruffi organised boys and young men to patrol the streets to curb immodest dress and behaviour. For a time, Pope Alexander VI (1492–1503) tolerated friar Girolamo's strictures against the Church, but he was moved to anger when Florence declined to join his new Holy League against the French invader, and blamed it on Savonarola's pernicious influence. An exchange of letters between the pope and the friar ended in an impasse which Savonarola tried to break by sending the pope "a little book" recounting his prophetic career and describing some of his more dramatic visions. This was the Compendium of Revelations, a self-dramatization which was one of the farthest-reaching and most popular of his writings.

The pope was not mollified. He summoned the friar to appear before him in Rome, and when Savonarola refused, pleading ill health and confessing that he was afraid of being attacked on the journey, Alexander banned him from further preaching. For some months Savonarola obeyed, but when he saw his influence slipping he defied the pope and resumed his sermons, which became more violent in tone. He not only attacked secret enemies at home whom he rightly suspected of being in league with the papal Curia, he condemned the conventional, or "tepid", Christians who were slow to respond to his calls. He dramatised his moral campaign with special Masses for the youth, processions, bonfires of the vanities and religious theatre in San Marco. He and his close friend, the humanist poet Girolamo Benivieni

Girolamo Benivieni (; 6 February 1453 – August 1542) was a Florentine poet and a musician. His father was a notary in Florence. He suffered poor health most of his life, which prevented him from taking a more stable job. He was a leading m ...

, composed lauds and other devotional songs for the Carnival processions of 1496, 1497 and 1498, replacing the bawdy Carnival songs of the era of Lorenzo de' Medici. These continued to be copied and performed after his death, along with songs composed by Piagnoni in his memory. A number of them have survived.

Proto-Protestant

Savonarola like the later reformers, desired a return to the "early apostolic simplicity". Many Protestants view Savonarola as a precursor to the reformation with respect to his views on "the doctrine of justification, his emphasis on individual faith, his emphasis on the authority of scripture and compassion for the poor". The writings of Savonarola spread widely toGermany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and Switzerland, and due to Savonarola's life and death, many people started to see the papacy as corrupted and sought a new reform of the church. Many people saw him as a martyr, including Martin Luther, who was influenced by Savonarola's writings. Savonarola's beliefs on the doctrine of justification are similar in some respects to Martin Luther’s teachings, stating that we are not justified by ourselves. Savonarola perhaps even influenced John Calvin, but this is a matter of historical debate.

Savonarola never abandoned the dogmas of the Roman Catholic Church; for example, Savonarola held to a belief in seven sacraments and that the Church of Rome is "the mother of all other churches and the pope its head." However his protests against papal corruption, reliance on the bible as the main guide link Savonarola with the later reformation. Savonarola himself held scripture as a very high authority, he himself stated: ”I preach the regeneration of the Church, taking the Scriptures as my sole guide.". It is untrue that God’s grace is obtained by pre-existing works of merit as though works and deserts were the cause of predestination. On the contrary, these are the result of predestination. Tell me, Peter; tell me, O Magdalene, wherefore are ye in paradise? Confess that not by your own merits have ye obtained salvation, but by the goodness of God '' — Girolamo Savonarola''.Other quotes from Savonarola such as "Not by their own deservings, O Lord, or by their own works have they been saved, lest any man should be able to boast, but because it seemed good in Thy sight." made

Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

say that even though the theology of Savonarola wasn't perfect, it was still an example of true Christian theology. Martin Luther later stated about Savonarola:Christ canonizes Savonarola through us even though popes and papists burst to pieces over it — Martin LutherSavonarola while revering the office of the papacy, nevertheless criticized the pope

Alexander VI

Pope Alexander VI ( it, Alessandro VI, va, Alexandre VI, es, Alejandro VI; born Rodrigo de Borja; ca-valencia, Roderic Llançol i de Borja ; es, Rodrigo Lanzol y de Borja, lang ; 1431 – 18 August 1503) was head of the Catholic Churc ...

and his papal court. Savonarola even prophecied that Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

will come under judgement from God.the Pope may command me to do something that contravenes the law of Christian love or the Gospel. But, if he did so command, I would say to him, thou art no shepherd. Not the Roman Church, but thou errest Who are the fat kine of Bashan on the mountains of Samaria? I say they are the courtesans of Italy and Rome. Or, are there none? A thousand are too few for Rome, 10,000, 12,000, 14,000 are too few for Rome. Prepare thyself, O Rome, for great will be thy punishments - Girolamo SavonarolaCatholic sources, however, criticize the inclusion of Savonarola as a Protestant forerunner, because much of his theology still aligned with Rome. Despite inspiring some Protestant reformers, Savonarola also influenced some leaders of the Counter-Reformation.

Excommunication and death

On 12 May 1497, Pope Alexander VI

On 12 May 1497, Pope Alexander VI excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

Savonarola and threatened the Florentines with an interdict

In Catholic canon law, an interdict () is an ecclesiastical censure, or ban that prohibits persons, certain active Church individuals or groups from participating in certain rites, or that the rites and services of the church are banished from ...

if they persisted in harbouring him. After describing the Church as a whore, Savonarola was excommunicated for heresy and sedition.

On 18 March 1498, after much debate and steady pressure from a worried government, Savonarola withdrew from public preaching. Under the stress of excommunication, he composed his spiritual masterpiece, the ''Triumph of the Cross

In the Christian liturgical calendar, there are several different Feasts of the Cross, all of which commemorate the cross used in the crucifixion of Jesus. Unlike Good Friday, which is dedicated to the passion of Christ and the crucifixion, these ...

'', a celebration of the victory of the Cross over sin and death and an exploration of what it means to be a Christian. This he summed up in the theological virtue of ''caritas'', or love. In loving their neighbours, Christians return the love which they have received from their Creator and Savior. Savonarola hinted at performing miracles to prove his divine mission, but when a rival Franciscan preacher proposed to test that mission by walking through fire

''Walking Through Fire'' is the twelfth studio album by the Canadian rock band April Wine, released in 1985 April Wine- Album Chart History @Billboard.com (''Walking Through Fire'' peaked in October of 1985)Retrieved 7-7-2012. (see 1985 in musi ...

, he lost control of public discourse. Without consulting him, his confidant Fra Domenico da Pescia offered himself as his surrogate and Savonarola felt he could not afford to refuse. The first trial by fire in Florence in over four hundred years was set for 7 April. A crowd filled the central square, eager to see if God would intervene, and if so, on which side. The nervous contestants and their delegations delayed the start of the contest for hours. A sudden rain drenched the spectators and government officials cancelled the proceedings. The crowd disbanded angrily; the burden of proof had been on Savonarola, and he was blamed for the fiasco. A mob assaulted the convent of San Marco.

Fra Girolamo, Fra Domenico, and Fra Silvestro Maruffi were arrested and imprisoned. Under torture Savonarola confessed to having invented his prophecies and visions, then recanted, then confessed again. In his prison cell in the tower of the government palace he composed meditations on Psalms 51 and 31. On the morning of 23 May 1498, the three friars were led out into the main square where, before a tribunal of high clerics and government officials, they were condemned as heretics and schismatics, and sentenced to die forthwith. Stripped of their Dominican garments in ritual degradation, they mounted the scaffold in their thin white shirts. Each on separate gallows, they were hanged, while fires were ignited below them to consume their bodies. To prevent devotees from searching for relics, their ashes were carted away and scattered in the Arno

The Arno is a river in the Tuscany region of Italy. It is the most important river of central Italy after the Tiber.

Source and route

The river originates on Monte Falterona in the Casentino area of the Apennines, and initially takes a ...

.

Aftermath

Resisting censorship and exile, the friars of San Marco fostered a cult of "the three martyrs" and venerated Savonarola as a saint. They encouraged women in local convents and surrounding towns to find mystical inspiration in his example, and, by preserving many of his sermons and writings, they helped keep his political as well as his religious ideas alive. The return of theMedici

The House of Medici ( , ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first began to gather prominence under Cosimo de' Medici, in the Republic of Florence during the first half of the 15th century. The family originated in the Mu ...

in 1512 ended the Savonarola-inspired republic and intensified pressure against the movement, although both were briefly revived in 1527 when the Medici were once again forced out. In 1530 Pope Clement VII

Pope Clement VII ( la, Clemens VII; it, Clemente VII; born Giulio de' Medici; 26 May 1478 – 25 September 1534) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 November 1523 to his death on 25 September 1534. Deemed "the ...

(Giulio de' Medici), with the help of soldiers of the Holy Roman Emperor, restored Medici rule, and Florence became a hereditary dukedom.

Savonarola's contemporary Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli ( , , ; 3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527), occasionally rendered in English as Nicholas Machiavel ( , ; see below), was an Italian diplomat, author, philosopher and historian who lived during the Renaissance. ...

discusses the friar in Chapter VI of his book ''The Prince

''The Prince'' ( it, Il Principe ; la, De Principatibus) is a 16th-century political treatise written by Italian diplomat and political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli as an instruction guide for new princes and royals. The general theme of ''The ...

'', writing:

Savonarolan religious ideas found a reception elsewhere. In Germany and Switzerland the early Protestant reformers, most notably

Savonarolan religious ideas found a reception elsewhere. In Germany and Switzerland the early Protestant reformers, most notably Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

himself, read some of the friar's writings and praised him as a martyr and forerunner whose ideas on faith and grace anticipated Luther's own doctrine of justification by faith alone. In France many of his works were translated and published and Savonarola came to be regarded as a precursor of evangelical, or Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

, reform though Savonarola himself had remained a believer in the dogmas of the Catholic church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and even in his last major work had defended the institution of the papacy. Within the Dominican Order Savonarola was seen as a devotional figure ("the evolving image of a Counter-Reformation saintly prelate"), and in this benevolent guise his memory lived on. Philip Neri

Philip Romolo Neri ( ; it, italics=no, Filippo Romolo Neri, ; 22 July 151526 May 1595), known as the "Second Apostle of Rome", after Saint Peter, was an Italian priest noted for founding a society of secular clergy called the Congregation of ...

, founder of the Oratorians An Oratorian is a member of one of the following religious orders:

* Oratory of Saint Philip Neri (Roman Catholic), who use the postnominal letters C.O.

* Oratory of Jesus (Roman Catholic)

* Oratory of the Good Shepherd (Anglican)

* Teologisk Orator ...

, a Florentine who had been educated by the San Marco Dominicans, also defended Savonarola's memory. In Wittenberg

Wittenberg ( , ; Low Saxon: ''Wittenbarg''; meaning ''White Mountain''; officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg (''Luther City Wittenberg'')), is the fourth largest town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Wittenberg is situated on the River Elbe, north o ...

, the hometown of Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

, a statue of Girolamo Savonarola was erected to honour him.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the "New Piagnoni" found inspiration in the friar's writings and sermons for the Italian national awakening known as the Risorgimento

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

. By emphasising his political activism over his puritanism and cultural conservatism they restored Savonarola's voice for radical political change. The venerable pre-Reformation icon ceded to the fiery Renaissance reformer. This somewhat anachronistic image, fortified by much new scholarship, informed the major new biography by Pasquale Villari

Pasquale Villari (3 October 1827 – 11 December 1917) was an Italian historian and politician.

Early life and publications

Villari was born in Naples and took part in the risings of 1848 there against the Bourbons and subsequently fled to Flore ...

, who regarded Savonarola's preaching against Medici despotism as the model for the Italian struggle for liberty and national unification. In Germany, the Catholic theologian and church historian Joseph Schnitzer

Joseph Schnitzer (15 June 1859 in Lauingen – 1 December 1939 in Munich) was a theologian. He started teaching at Munich University

The Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (simply University of Munich or LMU; german: Ludwig-Maximilians-Uni ...

edited and published contemporary sources which illuminated Savonarola's career. In 1924 he crowned his vast research with a comprehensive study of Savonarola's life and times in which he presented the friar as the last best hope of the Catholic Church before the catastrophe of the Protestant Reformation. In the Italian People's Party founded by Don Luigi Sturzo

Luigi Sturzo (; 26 November 1871 – 8 August 1959) was an Italian Catholic priest and prominent politician. He was known in his lifetime as a "clerical socialist" and is considered one of the fathers of the Christian democratic platform. He w ...

in 1919, Savonarola was revered as a champion of social justice, and after 1945 he was held up as a model of reformed Catholicism by leaders of the Christian Democratic Party

__NOTOC__

Christian democratic parties are political parties that seek to apply Christian principles to public policy. The underlying Christian democracy movement emerged in 19th-century Europe, largely under the influence of Catholic social tea ...

. From this milieu, in 1952, came the third of the major Savonarola biographies, the ''Vita di Girolamo Savonarola'' by Roberto Ridolfi. For the next half century Ridolfi was the guardian of the friar's saintly memory as well as the dean of Savonarola research which he helped grow into a scholarly industry. Today, with most of Savonarola's treatises and sermons and many of the contemporary sources (chronicles, diaries, government documents and literary works) available in critical editions, scholars can provide fresh, better informed assessments of his character and his place in the Renaissance, the Reformation and modern European history. The present-day Church has considered his beatification.

Bibliography

Savonarola's writings

Almost thirty volumes of Savonarola's sermons and writings have so far been published in the ''Edizione nazionale delle Opere di Girolamo Savonarola'' (Rome, Angelo Belardetti, 1953 to the present). For editions of the 15th and 16th centuries see ''Catalogo delle edizioni di Girolamo Savonarola (secc. xv–xvi)'' ed. P. Scapecchi (Florence, 1998, ).

* ''Prison Meditations on Psalms 51 and 31'' ed. John Patrick Donnelly, S.J. ()

* The Compendium of Revelations in Bernard McGinn ed. ''Apocalyptic Spirituality: Treatises and Letters of Lactantius,

Almost thirty volumes of Savonarola's sermons and writings have so far been published in the ''Edizione nazionale delle Opere di Girolamo Savonarola'' (Rome, Angelo Belardetti, 1953 to the present). For editions of the 15th and 16th centuries see ''Catalogo delle edizioni di Girolamo Savonarola (secc. xv–xvi)'' ed. P. Scapecchi (Florence, 1998, ).

* ''Prison Meditations on Psalms 51 and 31'' ed. John Patrick Donnelly, S.J. ()

* The Compendium of Revelations in Bernard McGinn ed. ''Apocalyptic Spirituality: Treatises and Letters of Lactantius, Adso of Montier-en-Der

Adso of Montier-en-Der ( la, Adso Dervensis) (910/920 – 992) was abbot of the Benedictine monastery of Montier-en-Der in France, and died on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Biographical information on Adso comes mainly from one single source and has ...

, Joachim of Fiore

Joachim of Fiore, also known as Joachim of Flora and in Italian Gioacchino da Fiore (c. 1135 – 30 March 1202), was an Italian Christian theologian, Catholic abbot, and the founder of the monastic order of San Giovanni in Fiore. According to th ...

, the Franciscan Spirituals

The Fraticelli (Italian for "Little Brethren") or Spiritual Franciscans opposed changes to the rule of Saint Francis of Assisi, especially with regard to poverty, and regarded the wealth of the Church as scandalous, and that of individual church ...

, Savonarola'' (New York, 1979, )

* Savonarola ''A Guide to Righteous Living and Other Works'' ed. Konrad Eisenbichler (Toronto, Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2003, )

* ''Selected Writings of Girolamo Savonarola Religion and Politics, 1490–1498'' ed. Anne Borelli and Maria Pastore Passaro (New Haven, Yale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day, and became an official department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and operationally autonomous.

, Yale Universi ...

, 2006, )

*

*

Cultural influence

Music

*William Byrd

William Byrd (; 4 July 1623) was an English composer of late Renaissance music. Considered among the greatest composers of the Renaissance, he had a profound influence on composers both from his native England and those on the continent. He ...

used the text of Savonarola's ''Infelix ego

''Infelix ego'' ("Alas, wretch that I am") is a Latin meditation on the ''Miserere'', Psalm 51 (Psalm 50 in Septuagint numbering), composed in prison by Girolamo Savonarola by 8 May 1498, after he was tortured on the rack, and two weeks before he ...

'' in his work by the same name as part of the '' Cantiones Sacrae 1591'' xxiv–xvi.

* Charles Villiers Stanford

Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (30 September 1852 – 29 March 1924) was an Anglo-Irish composer, music teacher, and conductor of the late Romantic era. Born to a well-off and highly musical family in Dublin, Stanford was educated at the ...

wrote an opera

Opera is a form of theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer and a libr ...

titled ''Savonarola'', which had its premiere in Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

on 18 April 1884.

* Luigi Dallapiccola

Luigi Dallapiccola (February 3, 1904 – February 19, 1975) was an Italian composer known for his lyrical serialism, twelve-tone compositions.

Biography

Dallapiccola was born in Pisino d'Istria (at the time part of Austria-Hungary, current ...

used text from Savonarola's Meditation on the Psalm ''My hope is in Thee, O Lord'' in his 1938 choral work '' Canti di prigionia''.

Fiction

* Lenau, Nikolaus, ''Savonarola'' (poem, 1837) * Eliot, George, ''Romola

''Romola'' (1862–63) is a historical novel written by Mary Ann Evans under the pen name of George Eliot set in the fifteenth century. It is "a deep study of life in the city of Florence from an intellectual, artistic, religious, and social poi ...

'' (novel, 1863)

* Mann, Thomas, '' Fiorenza'' (play, 1909)

* Herrmann, Bernhard, ''Savonarola im Feuer'' (1909)

* The 1917 story, "'Savonarola' Brown," by Max Beerbohm

Sir Henry Maximilian Beerbohm (24 August 1872 – 20 May 1956) was an English essayist, parodist and caricaturist under the signature Max. He first became known in the 1890s as a dandy and a humorist. He was the drama critic for the '' Saturd ...

(published in '' Seven Men''), concerns an aspiring playwright, author of an unfinished, unintentionally absurd retelling of the life of Savonarola. (His four-act play took him nine years to write, is eighteen pages long, and features a romance between Savonarola and Lucrezia Borgia, and also cameos by Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: '' ...

, Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

, and St. Francis of Assisi

Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, better known as Saint Francis of Assisi ( it, Francesco d'Assisi; – 3 October 1226), was a mystic Italian Catholic friar, founder of the Franciscans, and one of the most venerated figures in Christianit ...

.)

* Van Wyck, William, ''Savonarola: A Biography in Dramatic Episodes'' (1926)

* Hines and King, ''Fire of Vanity'' (play, 1930)

* Salacrou, Armand, ''Le terre est ronde'' (1938)

* The novel ''Kámen a bolest'' ("suffering and the stone") (1942), Karel Schulz

Karel Schulz (6 May 1899 – 27 February 1943) was a Czech novelist, theatre critic, poet and short story writer, whose best known work is the historical novel ''Stone and Pain'' (1942; cs, Kámen a bolest).Prokop, Vladimír. ''Přehled česk ...

's historical novel about the life of Michelangelo, features Savonarola as an important character.

* Bacon, Wallace A., Savonarola: A Play in Nine Scenes (1950)

* '' The Agony and the Ecstasy'' (1961), Irving Stone

Irving Stone (born Tennenbaum, July 14, 1903 – August 26, 1989) was an American writer, chiefly known for his biographical novels of noted artists, politicians, and intellectuals. Among the best known are '' Lust for Life'' (1934), about the l ...

's novelisation of Michelangelo's life, depicts the events in Florence from the Medici's point of view.

* The fourth segment of Walerian Borowczyk

Walerian Borowczyk (21 October 1923 – 3 February 2006) was an internationally known Polish film director described by film critics as a 'genius who also happened to be a pornographer'. He directed 40 films between 1946 and 1988. Borowczyk set ...

's 1974 anthology film, '' Immoral Tales'', is set during the reign of Pope Alexander VI. A character called "Friar Hyeronimus Savonarola", played by Philippe Desboeuf, holds a sermon in which he publicly condemns the corruption of the church and the sexual depravity of the papacy. Borowczyk juxtaposes Savonarola's sermon with the Pope enjoying a threesome

In human sexuality, a threesome is commonly understood as "a sexual interaction between three people whereby at least one engages in physical sexual behaviour with both the other individuals". Though ''threesome'' most commonly refers to sexua ...

with his daughter, Lucrezia Borgia, and his son, Cesare Borgia. Savonarola is arrested and publicly burned to death.

* In the 1976 film ''Network

Network, networking and networked may refer to:

Science and technology

* Network theory, the study of graphs as a representation of relations between discrete objects

* Network science, an academic field that studies complex networks

Mathematics ...

'', the network programming executive played by Faye Dunaway refers to crusading reporter Howard Beale as "a magnificent messianic figure, inveighing against the hypocrisies of our times, a strip

Strip or Stripping may refer to:

Places

* Aouzou Strip, a strip of land following the northern border of Chad that had been claimed and occupied by Libya

* Caprivi Strip, narrow strip of land extending from the Okavango Region of Namibia to ...

Savonarola, Monday through Friday".

* In her novel ''The Passion of New Eve

''The Passion of New Eve'' is a novel by Angela Carter, first published in 1977. The book is set in a dystopian United States where civil war has broken out between different political, racial and gendered groups. A dark satire, the book parod ...

'' (1977), Angela Carter

Angela Olive Pearce (formerly Carter, Stalker; 7 May 1940 – 16 February 1992), who published under the name Angela Carter, was an English novelist, short story writer, poet, and journalist, known for her feminist, magical realism, and picar ...

describes the preaching leader of an army of god-fearing child soldiers as a "precocious Savonarola".

* The novel ''The Palace

''The Palace'' is a British drama television series that aired on ITV in 2008. Produced by Company Pictures for the ITV network, it was created by Tom Grieves and follows a fictional British Royal Family in the aftermath of the death of King ...

'' (1978) by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro features Savonarola as the main antagonist of the vampire Saint Germain.

* The historical fantasy novel '' The Dragon Waiting'' (1984) by John M. Ford has Savonarola as one of the antagonists in chapter 3, set in the Medici court.

* The novel '' Sabbath's Theater'' (1995) by Philip Roth

Philip Milton Roth (March 19, 1933 – May 22, 2018) was an American novelist and short story writer.

Roth's fiction—often set in his birthplace of Newark, New Jersey—is known for its intensely autobiographical character, for philosophicall ...

makes reference to Savonarola.

* The novel ''The Birth of Venus

''The Birth of Venus'' ( it, Nascita di Venere ) is a painting by the Italian artist Sandro Botticelli, probably executed in the mid 1480s. It depicts the goddess Venus arriving at the shore after her birth, when she had emerged from the sea ...

'' (2003 ) by Sarah Dunant makes extensive references to Savonarola.

* In episode 7 (2003) of the manga-anime series ''Gunslinger Girl

''Gunslinger Girl'' (stylized in all caps) is a Japanese manga series by Yu Aida. It began serialization on May 21, 2002 in ''Dengeki Daioh'' and ended on September 27, 2012. The chapters were also published in 15 ''tankōbon'' volumes by A ...

'', two of the protagonists, Jean and Rico, visit Florence. There Savonarola is mentioned among other famous people who lived in the city, while he shares his surname with one of the series antagonists.

* The novel '' The Rule of Four'' (2004) by Ian Caldwell and Dustin Thomason

Dustin Thomason (born 1976) is an American writer and producer who co-authored the ''New York Times'' bestselling historical fiction novel '' The Rule of Four'' with Ian Caldwell.

Novels

Thomason began his career as a novelist. He is a co-autho ...

makes extensive references to Savonarola.

* In the novel ''I, Mona Lisa'' (2006) (UK title ''Painting Mona Lisa

''I, Mona Lisa'' (UK title ''Painting Mona Lisa'') is a historical novel by Jeanne Kalogridis about Lisa Gherardini, the model for Leonardo da Vinci's painting ''Mona Lisa''. Lisa is portrayed as a young Italian woman who learns about the murder ...

'') by Jeanne Kalogridis

Jeanne Kalogridis (pronounced ''Jean Kal-o-GREED-us''), also known by the pseudonym J.M. Dillard (born 1954), is a writer of historical, science and horror fiction.

She was born in Florida and studied at the University of South Florida, earning ...

, he is given a negative slant, as the Medicis are portrayed as sympathetic and noble.

* The novel '' The Enchantress of Florence'' (2008) by Salman Rushdie

Sir Ahmed Salman Rushdie (; born 19 June 1947) is an Indian-born British-American novelist. His work often combines magic realism with historical fiction and primarily deals with connections, disruptions, and migrations between Eastern and We ...

* The young adult novel '' The Smile'' (2008) by Donna Jo Napoli

Donna Jo Napoli (born February 28, 1948) is an American writer of children's and young adult fiction, as well as a linguist. She currently is a professor at Swarthmore College teaching Linguistics in all different forms (music, Theater (structure ...

shows Savonarola as he was observed by a young Mona Lisa.

* In the novel ''Wolf Hall

''Wolf Hall'' is a 2009 historical novel by English author Hilary Mantel, published by Fourth Estate, named after the Seymour family's seat of Wolfhall, or Wulfhall, in Wiltshire. Set in the period from 1500 to 1535, ''Wolf Hall'' is a symp ...

'' (2009) by Hilary Mantel

Dame Hilary Mary Mantel ( ; born Thompson; 6 July 1952 – 22 September 2022) was a British writer whose work includes historical fiction, personal memoirs and short stories. Her first published novel, '' Every Day Is Mother's Day'', was relea ...

, the Bonfire of the Vanities is brought up in a story by the protagonist, Thomas Cromwell.

* Savonarola appears as a main assassination target in the videogame ''Assassin's Creed II

''Assassin's Creed II'' is a 2009 action-adventure video game developed by Ubisoft Montréal and published by Ubisoft. It is the second major installment in the ''Assassin's Creed'' series, and the sequel to 2007's '' Assassin's Creed''. The g ...

'' (2009).

* In the novel, ''The Poet Prince'' (2010), Kathleen McGowan portrays him as an enemy of the Tuscan people in their pursuit of artistic fame during his reign.

* Savonarola's life story is explored in the novel ''Fanatics'' (2011) by William Bell and his ghost plays an important role in the story.

* In Showtime's '' The Borgias'', Savonarola is a recurring character in the two first seasons and is portrayed by Steven Berkoff. His burning takes place in the episode '' The Confession''.

* In the Netflix series '' Borgia'', Savonarola is portrayed by Iain Glen

Iain Alan Sutherland Glen (born 24 June 1961) is a Scottish actor. Glen is best known for his roles as Dr. Alexander Isaacs/Tyrant in three films of the ''Resident Evil'' film series (2004–2016) and as Ser Jorah Mormont in the HBO fantasy t ...

in season 2 (2013).

* Savonarola is a character in Canadian playwright Jordan Tannahill

Jordan Tannahill is a Canadian author, playwright, filmmaker, and theatre director.

His novels and plays have been translated into twelve languages, and honoured with a number of prizes including two Governor General's Literary Awards.

's 2016 play ''Botticelli in the Fire''.

* In the Rai Fiction series ''Medici

The House of Medici ( , ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first began to gather prominence under Cosimo de' Medici, in the Republic of Florence during the first half of the 15th century. The family originated in the Mu ...

'', Savonarola is portrayed by Francesco Montanari in season 2 (2018).

* The historical fantasy and alternate history novel ''Lent

Lent ( la, Quadragesima, 'Fortieth') is a solemn religious observance in the liturgical calendar commemorating the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring temptation by Satan, according to the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke ...

'' (2019) by Jo Walton

Jo Walton (born 1964) is a Welsh and Canadian fantasy and science fiction writer and poet. She is best known for the fantasy novel ''Among Others'', which won the Hugo and Nebula Awards in 2012, and '' Tooth and Claw'', a Victorian era novel ...

is a retelling of Savonarola's life.

References

Further reading

*Dall'Aglio, Stefano, ''Savonarola and Savonarolism'' (Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies. 2010). * Herzig,Tamar, ''Savonarola's Women: Visions and Reform in Renaissance Italy'' (Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2008). * Lowinsky, Edward E., ''Music in the Culture of the Renaissance and Other Essays'' (University of Chicago Press, 1989). *Macey, Patrick, ''Bonfire Songs: Savonarola's Musical Legacy'' (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1998). *Martines, Lauro, ''Fire in the City: Savonarola and the Struggle for Renaissance Florence'' (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006) * Meltzoff, Stanley, ''Botticelli, Signorelli and Savonarola: Theologia Poetica and Painting from Boccaccio to Poliziano'' (Florence: L.S. Olschki, 1987). *Morris, Samantha, ''The Pope’s Greatest Adversary: Girolamo Savonarola'' (South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword History, 2021). *Polizzotto, Lorenzo, ''The Elect Nation: The Savonarolan Movement in Florence, 1494–1545'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 1994). *Ridolfi, Roberto, ''Vita di Girolamo Savonarola'', ed. A.F. Verde, Florence (6th ed., 1997). * Roeder, Ralph Edmund LeClercq, ''The Man of the Renaissance: Four Lawgivers: Savanarola, Machiavelli, Castiglione, Aretino'', The Viking Press, 1933. *Steinberg, Ronald M., ''Fra Girolamo Savonarola, Florentine Art, and Renaissance Historiography'' (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1977). * Strathern, Paul, ''Death in Florence: The Medici, Savanarola, and the Battle for the Soul of a Renaissance City'' (New York, London: Pegasus Books, 2015). * Weinstein, Donald, ''Savonarola: The Rise and Fall of a Renaissance Prophet'' (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011) *Weinstein, Donald and Hotchkiss, Valerie R., eds. ''Girolamo Savonarola Piety, Prophecy and Politics in Renaissance Florence'', Catalogue of the Exhibition (Dallas, Bridwell Library, 1994).External links

Catholic Encyclopedia entry on Girolamo Savonarola

''Predica dell'arte del bene morire''

From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library ...

''Savonarola's Visions'', documentary about Girolamo Savonarola

{{DEFAULTSORT:Savonarola, Girolamo Executed Roman Catholic priests Italian Roman Catholics Italian torture victims Italian Dominicans People excommunicated by the Catholic Church People executed by the Papal States by burning People executed for heresy Religious leaders from Ferrara Rulers of Florence University of Ferrara alumni 1452 births 1498 deaths 15th-century Italian Roman Catholic priests Proto-Protestants