Saul Solomon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Saul Solomon (25 May 1817 – 16 October 1892) was an influential liberal politician of the Cape Colony, a British colony in what is now South Africa. Solomon was an important member of the movement for responsible government and an opponent of Lord Carnarvon's Confederation scheme.

/ref> As representative for Cape Town, Solomon entered the very first

retrieved 17 Nov 2017

/ref> Throughout his political career he strictly adhered to this manifesto – repeatedly turning down both cabinet and ministerial posts so as to be free to vote according to his beliefs. Although he was from a Jewish background and even funded the establishment of the Cape's first synagogue in 1849, Solomon was openly secular in outlook, declaring himself to be "a liberal in politics and a voluntary in religion". In the first Cape parliament in 1854, he presented his "Voluntary bill" (intended to end government subsidies to churches, and to ensure equal treatment of all beliefs) but it was turned down. He proceeded to put it to parliament every year, only for it to be repeatedly rejected, until it was finally passed under the

Although earlier in his career Solomon had been in favour of a form of federated "United States of Southern Africa", he shared with the Cape government concerns about the form and timing of Carnarvon's confederation project. Of particular concern to many liberal politicians were the repressive "native policies" of Natal and the Boer republics (which would have affected the rights of many Cape citizens). Saul Solomon joined the Cape government in arguing that the Cape's multi-racial constitution might not survive a session of bargaining with the Boer republics. Another issue was the fact that some neighbouring states, such as Zululand and the

Although earlier in his career Solomon had been in favour of a form of federated "United States of Southern Africa", he shared with the Cape government concerns about the form and timing of Carnarvon's confederation project. Of particular concern to many liberal politicians were the repressive "native policies" of Natal and the Boer republics (which would have affected the rights of many Cape citizens). Saul Solomon joined the Cape government in arguing that the Cape's multi-racial constitution might not survive a session of bargaining with the Boer republics. Another issue was the fact that some neighbouring states, such as Zululand and the

In 1873 he met Georgiana Margaret Thomson, the inaugural headteacher of a girls' school in Cape Colony, now known as Good Hope Seminary High School. Their views tallied on many matters, not least girls' education: he owned a first edition of

In 1873 he met Georgiana Margaret Thomson, the inaugural headteacher of a girls' school in Cape Colony, now known as Good Hope Seminary High School. Their views tallied on many matters, not least girls' education: he owned a first edition of

"Solomon, Georgiana Margaret (1844–1933)

, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography''. He retired from public life completely in 1883 due to poor health and moved to

retrieved 17 Nov 2017

/ref> who followed his mother into educational leadership as principal of the Bombay School of Art

Early life and background

Saul Solomon was born on the island ofSt Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constitu ...

on 25 May 1817. Although his family were St Helenan, they had close links to Cape Town. Saul spent his first years at a Jewish children's home in England, where he suffered from the malnutrition and rickets that physically affected him for the rest of his life. He then had a rudimentary formal education in South Africa before beginning work as an apprentice in a printing business. He later acquired the business and built it into the largest printing business in the country, founding the ''Cape Argus

The ''Cape Argus'' is a daily newspaper co-founded in 1857 by Saul Solomon and published by Sekunjalo in Cape Town, South Africa. It is commonly referred to as ''The Argus''.

Although not the first English-language newspaper in South Afric ...

'' newspaper. He was also one of the founders of Old Mutual

Old Mutual Limited is a pan-African investment, savings, insurance, and banking group. It is listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange, the Namibian Stock Exchange and the Botswana Stock Exchange. It was founded i ...

, today one of the largest insurance firms in South Africa.''1820gw – 2.3 Saul Solomon Family'', accessdate=2012-12-06/ref> As representative for Cape Town, Solomon entered the very first

Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope

The Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope functioned as the legislature of the Cape Colony, from its founding in 1853, until the creation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, when it was dissolved and the Parliament of South Africa was establish ...

(Cape Parliament) when it opened in 1854. He remained an MP for this constituency until his retirement in 1883.

Political career (1854–1883)

Saul Solomon's original election promise had been "to give my decided opposition to all legislation tending to introduce distinctions either of class, colour or creed".Stanley Trapido, 'Solomon, Saul (1817–1892)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 200retrieved 17 Nov 2017

/ref> Throughout his political career he strictly adhered to this manifesto – repeatedly turning down both cabinet and ministerial posts so as to be free to vote according to his beliefs. Although he was from a Jewish background and even funded the establishment of the Cape's first synagogue in 1849, Solomon was openly secular in outlook, declaring himself to be "a liberal in politics and a voluntary in religion". In the first Cape parliament in 1854, he presented his "Voluntary bill" (intended to end government subsidies to churches, and to ensure equal treatment of all beliefs) but it was turned down. He proceeded to put it to parliament every year, only for it to be repeatedly rejected, until it was finally passed under the

Molteno

Molteno (; lmo, label= Brianzöö, Mültée) is a '' comune'' (municipality) and a hill-top town in the Province of Lecco in the Italian region Lombardy, located about northeast of Milan and about southwest of Lecco. As of 31 December 2004, it ...

government in 1875.

The Responsible Government Movement (1854–1872)

Solomon joined the movement for responsible government in the Cape and helped to institute it when it was established in 1872. The leader of the responsible government movement, Prime MinisterJohn Charles Molteno

Sir John Charles Molteno (5 June 1814 – 1 September 1886) was a soldier, businessman, champion of responsible government and the first Prime Minister of the Cape Colony.

Early life

Born in London into a large Anglo-Italian family, Molteno ...

, was a friend and admirer. The two men were both businessmen from poor immigrant backgrounds who had outlooks that were relatively liberal for the times and saw eye-to-eye on a number of issues. According to Saul Solomon's official biography, Molteno only accepted the office of Prime Minister after insisting that it first be offered to Solomon, who turned it down however due to his delicate health. Solomon supported the Molteno Ministry, though he refused offers of cabinet positions so as to be able to oppose the government if and when his conscience required it. One supporter told Parliament that "Molteno would not hold a Ministry together for one week if Mr Solomon was in it; and no cabinet could do without him."

Eastern Cape Separatist League (1854–1874)

The eastern part of the Cape Colony had a long-running separatist movement, consisting of a portion of white settlers (the "Easterners"), led by parliamentarian John Paterson of Port Elizabeth, who resented the rule of the Cape Town parliament and wanted stricter labour laws to encourage theXhosa

Xhosa may refer to:

* Xhosa people, a nation, and ethnic group, who live in south-central and southeasterly region of South Africa

* Xhosa language

Xhosa (, ) also isiXhosa as an endonym, is a Nguni language and one of the official language ...

to leave their lands and work on the settlers' plantations.

In accordance with his stated policy that "natives should be allowed to sell their labour as they desired, and that no semblance of coercion should be employed to provide labour for the farmer" and because he detested the Easterners' white supremacist views, Solomon took a strong stance against the separatist movement and for a united, multi-racial Cape.

When he was addressing parliament about the need to enforce the principles of racial equality that the Cape's constitution called for, the Separatist representatives all stood up and walked out on him. He reportedly declared: "I would rather address empty benches than empty minds!"

In parliament he went on to lead the "Westerners", who backed the Molteno–Merriman government in successfully crushing the separatist league. Separatist parliamentarians branded him a " negrophile" – an intended insult that he in fact accepted with considerable pride, and he went on to push even further for social reform (for example repealing the discriminatory Contagious Diseases Act

The Contagious Diseases Acts (CD Acts) were originally passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1864 (27 & 28 Vict. c. 85), with alterations and additions made in 1866 (29 & 30 Vict. c. 35) and 1869 (32 & 33 Vict. c. 96). In 1862, a com ...

).

The imposition of Confederation (1874–1878)

Starting in 1874, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Carnarvon, having federated Canada, began an ill-fated plan to impose the same system of confederation on the very different states of southern Africa. Although earlier in his career Solomon had been in favour of a form of federated "United States of Southern Africa", he shared with the Cape government concerns about the form and timing of Carnarvon's confederation project. Of particular concern to many liberal politicians were the repressive "native policies" of Natal and the Boer republics (which would have affected the rights of many Cape citizens). Saul Solomon joined the Cape government in arguing that the Cape's multi-racial constitution might not survive a session of bargaining with the Boer republics. Another issue was the fact that some neighbouring states, such as Zululand and the

Although earlier in his career Solomon had been in favour of a form of federated "United States of Southern Africa", he shared with the Cape government concerns about the form and timing of Carnarvon's confederation project. Of particular concern to many liberal politicians were the repressive "native policies" of Natal and the Boer republics (which would have affected the rights of many Cape citizens). Saul Solomon joined the Cape government in arguing that the Cape's multi-racial constitution might not survive a session of bargaining with the Boer republics. Another issue was the fact that some neighbouring states, such as Zululand and the Transvaal Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when i ...

, would require military invasion to be incorporated into the confederation. Consequently, Solomon opposed Carnarvon's proposal and the "new and impatient imperialism" which motivated it.

As an alternative, Solomon proposed a looser system of federation, whereby the Cape could preserve its multi-racial franchise. Another proposed alternative was the "Molteno Plan" of the Cape Government, which advocated complete union instead of confederation, but with the Cape's constitution (including the multi-racial franchise) extended and imposed on the other states of southern Africa. Both suggestions were ignored by the Colonial Office and over the next few years Carnarvon's disastrous confederation scheme unravelled as predicted, eventually resulting the outbreak of several destructive conflicts across the region.

The Sprigg Government (1878–1881)

To further the Confederation scheme, Sir Henry Bartle Frere appointed a new and more compliant government, under the puppet Prime MinisterGordon Sprigg

Sir John Gordon Sprigg, (27 April 1830 – 4 February 1913) was an English-born colonial administrator, politician and four-time prime minister of the Cape Colony.

Early life

Sprigg was born in Ipswich, England, into a strongly Puritan fa ...

. Against the backdrop of the wider "Confederation wars" that now swept southern Africa, Sprigg began to institute a more discriminatory policy towards the Cape's Black African citizens, leading to revolts and further conflicts like the Basuto Gun War.

Although Saul Solomon had initially agreed to accept Sprigg's new government, its discriminatory policies immediately brought down his strongest criticism, which was voiced through his various media outlets. This culminated in his public campaign against the government for its role in the Koegas atrocities

The Koegas atrocities or Koegas affair (1878–80) was a notorious murder case in the Cape Colony, which led to deep political divisions and a follow up campaign, due to the perceived racial bias of the country's Attorney General. It culminated i ...

.

Sprigg's retaliation was swift. He ordered a review and cancellation of all government contracts with the Argus and other businesses that were linked to Saul Solomon. These were all given to political allies (though without the equipment to fulfill them and at several times the price). Meanwhile, Sprigg's Attorney-General, Upington, launched a series of high-profile lawsuits (bordering on show trial

A show trial is a public trial in which the judicial authorities have already determined the guilt (law), guilt or innocence of the defendant. The actual trial has as its only goal the presentation of both the accusation and the verdict to the ...

s) against Solomon himself.

The "Pro Bono Publico" trial (1878–79)

Solomon's editor, Patrick McLoughlin, had supposedly anonymously written several pieces criticising the Sprigg government and the British colonial establishment, the most infamous of which was entitled "Pro Bono Publico" ("For the Public Good"). A series of libel lawsuits were launched by the Sprigg government, ultimately targeting Solomon, whom it tried to link the pamphlets too. Although it was never proven that McLoughlin even authored the pamphlets in question (and Solomon believed he had not), the trial and related pressures caused McLoughlin to resign (he shot himself a few years later). The Sprigg party failed however, to bring Solomon himself down.The "Fiat Justitia" trial (1879–80)

The following year, Solomon's enemies had another opportunity. The Argus printed reports of racism and miscarriage of justice regarding the earlier trials for the Koegas murders, which had been sent to it signed "Fiat Justitia" ("May there be justice"). This generated another round of political trials. These attacked Solomon's new editor, Francis Dormer, for libel but again sought ultimately to damage Solomon himself. Once again the editor resigned, and once again Solomon survived, in spite of losing the trial. Crucially, he produced letters from the Koegas trial judge asking him to publish the information, and detailing the brutal violence of the murders and the racism which had prevented justice being done. "Fiat Justitia" ultimately turned out to have been Mr D.P. Faure, who had served as the Koegas court interpreter. Faure was driven from his official career by the Sprigg government, but Solomon later sought out the unemployed Faure and gave him a token translator job with the Argus.Aftermath

Solomon emerged from these attacks financially damaged, but largely victorious. The government, frantically cutting back on core infrastructure to avoid bankruptcy from its war expenses, became increasingly unpopular. When its British backers were recalled to London to face charges of misconduct, the Sprigg government fell.Personal details

Physically, Solomon was partially disabled. Childhood poverty and ill health, aggravated by a bout of rickets, had left him with badly stunted legs. When standing, this made him so short that he needed to stand on a chair to be seen when addressing Parliament. His physical condition was particularly drawn attention to by his very high-pitched voice, as well as by the frequent presence by his side of his friend and political ally Molteno, who was unusually tall, and the image of the two men together was a topic for caricature by the political cartoonists of the time. Saul Solomon was nonetheless an eloquent and persuasive speaker with a skill for reasoned argument. His proposals were usually well researched and he characteristically spent long hours studying censuses and other government publications for the precise facts and figures that he believed should inform his opinions. Consequently, he was typically always able to back up his opinions with great quantities of evidence as well as with a clear application of logic. This earned him considerable respect, even from his political opponents. An example is the cautious and guarded homage which writer Stanley Little, a political opponent, later paid to Saul Solomon in his 1887 work on the Cape's political leadership. His progressive views on equal rights extended to gender relations (for his marriage ceremony he asked that his wife should not have to vow to "obey" him), religion (he never officially renounced his Judaism, but he abhorred sectarian attitudes and attended churches as often as synagogues) and class (he asked his employees and household servants to simply call him "Saul").Marriage, children, and later life

In 1873 he met Georgiana Margaret Thomson, the inaugural headteacher of a girls' school in Cape Colony, now known as Good Hope Seminary High School. Their views tallied on many matters, not least girls' education: he owned a first edition of

In 1873 he met Georgiana Margaret Thomson, the inaugural headteacher of a girls' school in Cape Colony, now known as Good Hope Seminary High School. Their views tallied on many matters, not least girls' education: he owned a first edition of Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (, ; 27 April 1759 – 10 September 1797) was a British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationsh ...

's polemic ''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects'' (1792), written by British philosopher and women's rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), is one of the earliest works of feminist philosoph ...

''. Despite his being almost twice her age, they married. The wedding, which took place on 21 March 1874 at his home, was to have had an alteration to the standard Anglican marriage vows

Marriage vows are promises each partner in a couple makes to the other during a wedding ceremony based upon Western Christian norms. They are not universal to marriage and not necessary in most legal jurisdictions. They are not even universal w ...

: neither wife nor husband wished her to promise to obey him. However, the two clergymen officiating told the couple that this would render the ceremony without authority, so the words were included. One historian describes their marriage as "idyllic". The couple had six children.

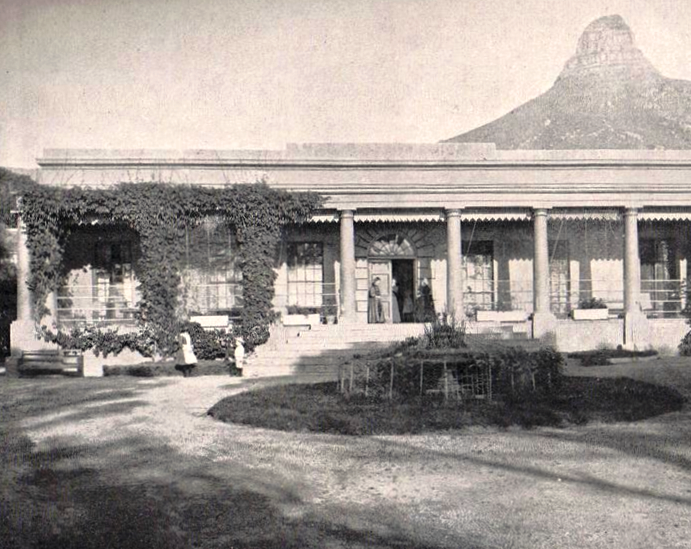

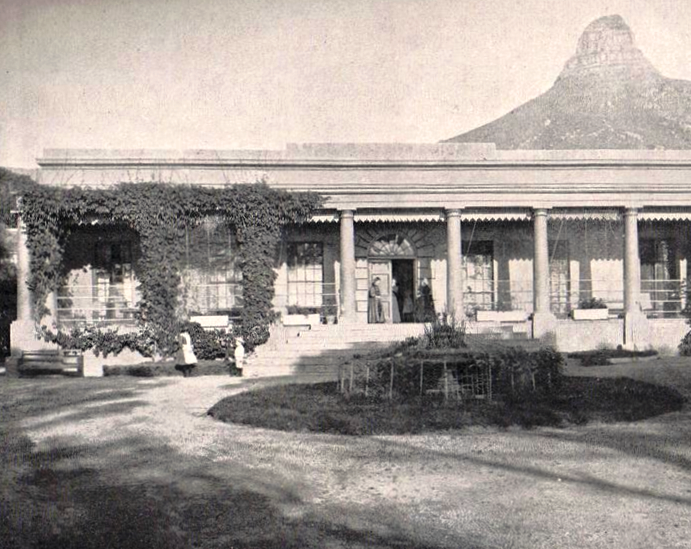

He lived at Clarensville House in Sea Point, Cape Town for most of his life. He and Georgiana enjoyed welcoming guests as varied as Cetewayo

King Cetshwayo kaMpande (; ; 1826 – 8 February 1884) was the king of the Zulu Kingdom from 1873 to 1879 and its Commander in Chief during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. His name has been transliterated as Cetawayo, Cetewayo, Cetywajo and Ketchw ...

, King of the Zulus

Zulu people (; zu, amaZulu) are a Nguni ethnic group native to Southern Africa. The Zulu people are the largest ethnic group and nation in South Africa, with an estimated 10–12 million people, living mainly in the province of KwaZulu-Nata ...

, and the future British Emperors, Princes Edward and George

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presiden ...

.

In 1881 the eldest daughter drowned – as did the governess who tried to rescue the child. Solomon's health declined and he withdrew from public life, even handing his business over to his nephews. Saul retired from public life, and the family moved to Bedford in England in 1888, where their sons attended Bedford School

:''Bedford School is not to be confused with Bedford Girls' School, Bedford High School, Bedford Modern School, Old Bedford School in Bedford, Texas or Bedford Academy in Bedford, Nova Scotia.''

Bedford School is a public school (English ind ...

. Saul died in 1892, leaving Georgiana with four children to raise.van Heyningen, Elizabeth (May 2006)"Solomon, Georgiana Margaret (1844–1933)

, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography''. He retired from public life completely in 1883 due to poor health and moved to

Kilcreggan

Kilcreggan (Scottish Gaelic: ''Cille Chreagain'') is a village on the Rosneath peninsula in Argyll and Bute, West of Scotland.

It developed on the north shore of the Firth of Clyde at a time when Clyde steamers brought it within easy reach o ...

, Scotland, in 1888. It was here that he died in 1892, of "Chronic tubular nephritis".

Saul Solomon's extended family remained deeply involved in politics and law in southern Africa for many years – though they varied greatly in their political allegiance. In particular, his nephews Sir Richard Solomon and Edward Philip Solomon

Sir Edward Phillip Solomon (1845 – 20 November 1914) was a successful lawyer and politician of the Transvaal Colony and the Union of South Africa.

Early life

Edward Solomon was born in 1845, studied to be an attorney, and based himself in Joha ...

were very influential at the time of the Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the South ...

and the lead up to the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Tra ...

; their brother William Henry Solomon became the Union's Chief Justice.

Solomon's wife Georgiana survived him by over 40 years, and was an influential suffragette. Of their three children who lived to adulthood, Daisy Solomon was also a suffragette, Hon. Saul Solomon was a high court judge (the Supreme Court of South Africa

The Supreme Court of South Africa was a superior court of law in South Africa from 1910 to 1997. It was made up of various provincial and local divisions with jurisdiction over specific geographical areas, and an Appellate Division which was th ...

), and William Ewart Gladstone Solomon was a noted painterElizabeth van Heyningen, 'Solomon , Georgiana Margaret (1844–1933)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, May 200retrieved 17 Nov 2017

/ref> who followed his mother into educational leadership as principal of the Bombay School of Art

See also

*Gordon Sprigg

Sir John Gordon Sprigg, (27 April 1830 – 4 February 1913) was an English-born colonial administrator, politician and four-time prime minister of the Cape Colony.

Early life

Sprigg was born in Ipswich, England, into a strongly Puritan fa ...

* Henry Bartle Frere

* History of Cape Colony from 1870 to 1899

* Freedom of religion in South Africa

, -

-

References

;NotesFurther reading

* ''Illustrated History of South Africa''. The Reader's Digest Association South Africa (Pty) Ltd, 1992. * Solomon, W. E. C: ''Saul Solomon – the Member for Cape Town''. Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 1948. * * Green, L: ''A Taste of the South-Easter''. Cape Town: Howard Timmins, 1971. * Green, L: ''I Heard the Old Men Say''. Cape Town: Howard Timmins, 1964. {{DEFAULTSORT:Solomon, Saul 19th century in Africa 19th-century South African people 1817 births 1892 deaths Cape Colony politicians Members of the House of Assembly of the Cape Colony Saint Helenian emigrants to South Africa Saint Helenian Jews South African businesspeople South African Jews