Sarah Jennings on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough, Princess of Mindelheim, Countess of Nellenburg (née Jenyns, spelt Jennings in most modern references; 5 June 1660 (Old Style) – 18 October 1744), was an English courtier who rose to be one of the most influential women of her time through her close relationship with

In 1677, Jennings's brother Ralph died, and she and her sister Frances became co-heirs of the family estates in Hertfordshire and Kent. Churchill chose Sarah Jennings over Catherine Sedley, but both Churchill's and Jennings's families disapproved of the match, and therefore they married secretly in the winter of 1677–78.

John and Sarah Churchill were both Protestants in a predominantly Catholic court, a circumstance that would complicate their political allegiances. Although no date was recorded, the marriage was announced only to the Duchess of York and a small circle of friends, so that Sarah could keep her court position as Maid of Honour.

When Churchill became pregnant, her marriage was announced publicly (on 1 October 1678), and she retired from the court to give birth to her first child, Harriet, who died in infancy. When the Duke of York went into self-imposed exile to Scotland as a result of the furore surrounding the

In 1677, Jennings's brother Ralph died, and she and her sister Frances became co-heirs of the family estates in Hertfordshire and Kent. Churchill chose Sarah Jennings over Catherine Sedley, but both Churchill's and Jennings's families disapproved of the match, and therefore they married secretly in the winter of 1677–78.

John and Sarah Churchill were both Protestants in a predominantly Catholic court, a circumstance that would complicate their political allegiances. Although no date was recorded, the marriage was announced only to the Duchess of York and a small circle of friends, so that Sarah could keep her court position as Maid of Honour.

When Churchill became pregnant, her marriage was announced publicly (on 1 October 1678), and she retired from the court to give birth to her first child, Harriet, who died in infancy. When the Duke of York went into self-imposed exile to Scotland as a result of the furore surrounding the

In 1702, William III died, and Anne became queen. Anne immediately offered John Churchill a dukedom, which Sarah initially refused. Sarah was concerned that a dukedom would strain the family's finances; a ducal family at the time was expected to show off its rank through lavish entertainments. Anne countered by offering the Marlboroughs a

In 1702, William III died, and Anne became queen. Anne immediately offered John Churchill a dukedom, which Sarah initially refused. Sarah was concerned that a dukedom would strain the family's finances; a ducal family at the time was expected to show off its rank through lavish entertainments. Anne countered by offering the Marlboroughs a

The Duchess's frankness and indifference for rank, so admired by Anne earlier in their friendship, was now seen to be intrusive. The Duchess had a powerful intimacy with the two most powerful men in the country, the Duke of Marlborough (her husband) and the Earl of Godolphin. Godolphin, though a great friend of the Duchess, had considered refusing high office after Anne's accession, preferring to live quietly and away from the Duchess of Marlborough's political side. The Earl considered the Duchess (as a powerful and intelligent woman) bossy, interfering, and presuming to tell him what to do when the Duke was away.

The Duchess, although a woman in a man's world of national and international politics, was always ready to give her advice, express her opinions, antagonize with outspoken censure, and insist on having her say on every possible occasion.Hibbert, p. 312 However, she had a charm and vivaciousness admired by many, and she could easily delight those she met with her wit.

Anne's apparent withdrawal of genuine affection occurred for a number of reasons. She was frustrated by the Duchess of Marlborough's long absences from court and despite numerous letters from Anne to the Duchess on this subject, the Duchess rarely attended. There was also a political difference between them: the Queen was a

The Duchess's frankness and indifference for rank, so admired by Anne earlier in their friendship, was now seen to be intrusive. The Duchess had a powerful intimacy with the two most powerful men in the country, the Duke of Marlborough (her husband) and the Earl of Godolphin. Godolphin, though a great friend of the Duchess, had considered refusing high office after Anne's accession, preferring to live quietly and away from the Duchess of Marlborough's political side. The Earl considered the Duchess (as a powerful and intelligent woman) bossy, interfering, and presuming to tell him what to do when the Duke was away.

The Duchess, although a woman in a man's world of national and international politics, was always ready to give her advice, express her opinions, antagonize with outspoken censure, and insist on having her say on every possible occasion.Hibbert, p. 312 However, she had a charm and vivaciousness admired by many, and she could easily delight those she met with her wit.

Anne's apparent withdrawal of genuine affection occurred for a number of reasons. She was frustrated by the Duchess of Marlborough's long absences from court and despite numerous letters from Anne to the Duchess on this subject, the Duchess rarely attended. There was also a political difference between them: the Queen was a

The Duchess's last attempt to re-establish her friendship with Anne came in 1710 when they had their final meeting. An account written by the Duchess shortly afterwards shows that she pleaded to be given an explanation of why their friendship was at an end, but Anne was unmoved, coldly repeating a few set phrases such as "I shall make no answer to anything you say" and "you may put it in writing".

The Duchess was so appalled by the Queen's "inhuman" conduct that she was reduced to tears, and most unusually for a woman who rarely spoke of religion, ended by threatening the Queen with the judgment of God. Anne replied that God's judgment on her concerned herself only, but later admitted that this was the one remark from the Duchess that hurt her deeply.

After hearing this, the Duke of Marlborough, realising that Anne intended to dismiss him and his wife, begged the Queen to keep them in their offices for nine months until the campaign was over, so that they could retire honourably. However, Anne told the Duke that "for her nne'shonour" the Duchess was to resign immediately and return her gold key – the symbol of her authority within the royal household – within two days.Field, p. 287. Years of trying the Queen's patience finally had resulted in her dismissal. When told the news, the Duchess, in a fit of pride, told the Duke to return the key to the Queen immediately.

In January 1711, the Duchess of Marlborough lost the offices of Mistress of the Robes and

The Duchess's last attempt to re-establish her friendship with Anne came in 1710 when they had their final meeting. An account written by the Duchess shortly afterwards shows that she pleaded to be given an explanation of why their friendship was at an end, but Anne was unmoved, coldly repeating a few set phrases such as "I shall make no answer to anything you say" and "you may put it in writing".

The Duchess was so appalled by the Queen's "inhuman" conduct that she was reduced to tears, and most unusually for a woman who rarely spoke of religion, ended by threatening the Queen with the judgment of God. Anne replied that God's judgment on her concerned herself only, but later admitted that this was the one remark from the Duchess that hurt her deeply.

After hearing this, the Duke of Marlborough, realising that Anne intended to dismiss him and his wife, begged the Queen to keep them in their offices for nine months until the campaign was over, so that they could retire honourably. However, Anne told the Duke that "for her nne'shonour" the Duchess was to resign immediately and return her gold key – the symbol of her authority within the royal household – within two days.Field, p. 287. Years of trying the Queen's patience finally had resulted in her dismissal. When told the news, the Duchess, in a fit of pride, told the Duke to return the key to the Queen immediately.

In January 1711, the Duchess of Marlborough lost the offices of Mistress of the Robes and

The Duchess and Queen Anne never made up their differences, although one eyewitness claimed to have heard Anne asking whether the Marlboroughs had reached the shore, leading to rumours that she had called them home herself. Anne died on 1 August 1714 at

The Duchess and Queen Anne never made up their differences, although one eyewitness claimed to have heard Anne asking whether the Marlboroughs had reached the shore, leading to rumours that she had called them home herself. Anne died on 1 August 1714 at  The Duchess was relieved to move back to England. The Duke became one of the King's close advisers, and the Duchess moved back into

The Duchess was relieved to move back to England. The Duke became one of the King's close advisers, and the Duchess moved back into

The Duke of Marlborough died at Windsor in 1722, and the Duchess arranged a large funeral for him. Their daughter Henrietta became duchess in her own right. The Dowager Duchess became one of the trustees of the Marlborough estate, and she used her business sense to distribute the family fortune, including the income for her daughter Henrietta.

The Dowager Duchess's personal income was now considerable, and she used the money to invest in land; she believed this would protect her from

The Duke of Marlborough died at Windsor in 1722, and the Duchess arranged a large funeral for him. Their daughter Henrietta became duchess in her own right. The Dowager Duchess became one of the trustees of the Marlborough estate, and she used her business sense to distribute the family fortune, including the income for her daughter Henrietta.

The Dowager Duchess's personal income was now considerable, and she used the money to invest in land; she believed this would protect her from  The Duchess of Marlborough fought against anything she thought was extravagant. She wrote to the Duke of Somerset, "I have reduced the stables to one-third of what was intended by Sir John

The Duchess of Marlborough fought against anything she thought was extravagant. She wrote to the Duke of Somerset, "I have reduced the stables to one-third of what was intended by Sir John  The Dowager Duchess's friendship with Queen Caroline ended when she refused the Queen access through her Wimbledon estate, which resulted in the loss of her £500 income as Ranger of Windsor Great Park.Hibbert, p. 334. The Dowager Duchess was also rude to King George II – making it clear that he was "too much of a German" – which further alienated her from the court. Her '' persona non-grata'' status at the Walpole-controlled court prevented her from suppressing the rise of the Tories; Walpole's taxes and peace with Spain were deeply unpopular with ruling class English society, and the Tories were gaining much more support as a result.

The Dowager Duchess never lost her good looks and, despite failing popularity, received many offers of marriage after the death of her husband, including one from her old enemy, the Duke of Somerset. Ultimately, she decided against remarriage, preferring to keep her independence. The Dowager Duchess continued to appeal against court decisions which ruled that funding for Blenheim should come from the Marlboroughs' personal estate, and not the government. This made her unpopular; as a trustee of her family's estate, she could easily have afforded the payments herself. She was surprised by the grief she felt following the death of her eldest living daughter, Henrietta, in 1733. The Dowager Duchess lived to see her enemy Robert Walpole fall in 1742, and in the same year attempted to improve her reputation by approving a biographical publication titled ''An Account of the Dowager Duchess of Marlborough from her first coming to Court to the year 1710''. She died at the age of 84, on 18 October 1744, at Marlborough House; she was buried at Blenheim. Her husband's body was exhumed from

The Dowager Duchess's friendship with Queen Caroline ended when she refused the Queen access through her Wimbledon estate, which resulted in the loss of her £500 income as Ranger of Windsor Great Park.Hibbert, p. 334. The Dowager Duchess was also rude to King George II – making it clear that he was "too much of a German" – which further alienated her from the court. Her '' persona non-grata'' status at the Walpole-controlled court prevented her from suppressing the rise of the Tories; Walpole's taxes and peace with Spain were deeply unpopular with ruling class English society, and the Tories were gaining much more support as a result.

The Dowager Duchess never lost her good looks and, despite failing popularity, received many offers of marriage after the death of her husband, including one from her old enemy, the Duke of Somerset. Ultimately, she decided against remarriage, preferring to keep her independence. The Dowager Duchess continued to appeal against court decisions which ruled that funding for Blenheim should come from the Marlboroughs' personal estate, and not the government. This made her unpopular; as a trustee of her family's estate, she could easily have afforded the payments herself. She was surprised by the grief she felt following the death of her eldest living daughter, Henrietta, in 1733. The Dowager Duchess lived to see her enemy Robert Walpole fall in 1742, and in the same year attempted to improve her reputation by approving a biographical publication titled ''An Account of the Dowager Duchess of Marlborough from her first coming to Court to the year 1710''. She died at the age of 84, on 18 October 1744, at Marlborough House; she was buried at Blenheim. Her husband's body was exhumed from

Although the Duchess of Marlborough's downfall is chiefly attributed to her own self-serving relationship with Queen Anne, she was a vibrant and intelligent woman who promoted Anne's interests when she was princess. However, she found Anne a dull conversationalist and the Duchess did not find her company stimulating.

The Duchess believed that she had a right to enforce her political advice, whether Anne personally liked it or not, and became angry if the Queen stubbornly refused to take it. She seems to have underestimated Anne's strength of character, continuing to believe she could dominate a woman whom foreign ambassadors noted had become "very determined and quite ferocious". Apart from her notorious bad temper, the Duchess's main weakness has been described as "an almost pathological inability to admit the validity of anyone else's point of view".

Abigail Masham also played a key role in the Duchess's downfall. Modest and retiring, she promoted the Tory policies of her cousin Robert Harley. Despite Masham's owing her position at court to the Duchess of Marlborough, the Duchess soon saw Masham as her enemy who supplanted her in Anne's affections when the Duchess spent more and more time away from the Queen.

During her lifetime, the Duchess of Marlborough drafted 26 wills, the last of which was only written a few months before her death, and purchased 27 estates. With a wealth of over £4 million in land, £17,000 in rent rolls, and a further £12,500 in annuities, she made financial bequests to rising Whig ministers such as William Pitt, later the first Earl of Chatham, and

Although the Duchess of Marlborough's downfall is chiefly attributed to her own self-serving relationship with Queen Anne, she was a vibrant and intelligent woman who promoted Anne's interests when she was princess. However, she found Anne a dull conversationalist and the Duchess did not find her company stimulating.

The Duchess believed that she had a right to enforce her political advice, whether Anne personally liked it or not, and became angry if the Queen stubbornly refused to take it. She seems to have underestimated Anne's strength of character, continuing to believe she could dominate a woman whom foreign ambassadors noted had become "very determined and quite ferocious". Apart from her notorious bad temper, the Duchess's main weakness has been described as "an almost pathological inability to admit the validity of anyone else's point of view".

Abigail Masham also played a key role in the Duchess's downfall. Modest and retiring, she promoted the Tory policies of her cousin Robert Harley. Despite Masham's owing her position at court to the Duchess of Marlborough, the Duchess soon saw Masham as her enemy who supplanted her in Anne's affections when the Duchess spent more and more time away from the Queen.

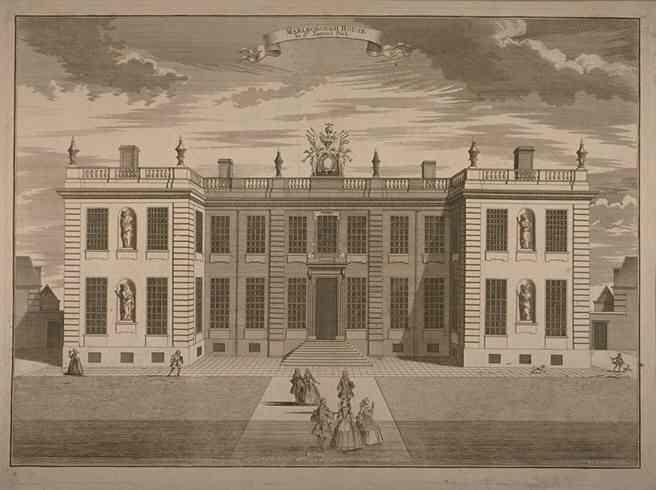

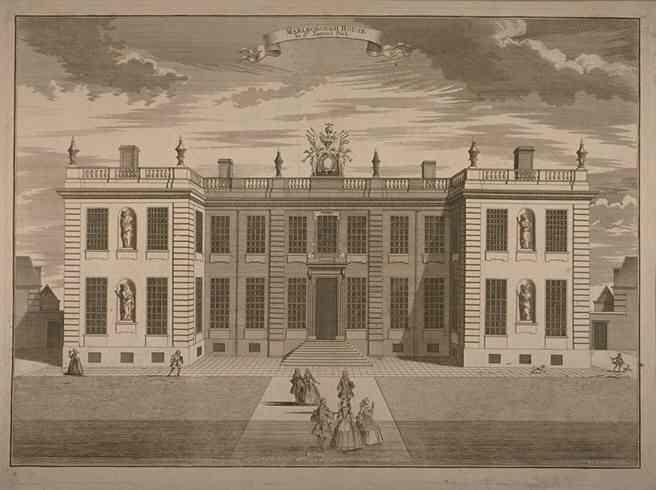

During her lifetime, the Duchess of Marlborough drafted 26 wills, the last of which was only written a few months before her death, and purchased 27 estates. With a wealth of over £4 million in land, £17,000 in rent rolls, and a further £12,500 in annuities, she made financial bequests to rising Whig ministers such as William Pitt, later the first Earl of Chatham, and  Much of the money left after the Duchess's numerous bequests was inherited by her grandson John Spencer, with the condition that he could not accept a political office under the government. He also inherited the remainder of the Duchess's numerous estates, including Wimbledon. Marlborough House remained empty for 14 years, with the exception of James Stephens, one of her executors, before it became the property of the Dukes of Marlborough upon Stephens's death.

In 1817, Marlborough House became a royal residence, and passed through members of the British royal family until it became the

Much of the money left after the Duchess's numerous bequests was inherited by her grandson John Spencer, with the condition that he could not accept a political office under the government. He also inherited the remainder of the Duchess's numerous estates, including Wimbledon. Marlborough House remained empty for 14 years, with the exception of James Stephens, one of her executors, before it became the property of the Dukes of Marlborough upon Stephens's death.

In 1817, Marlborough House became a royal residence, and passed through members of the British royal family until it became the

Berkshire History biography about Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough

Encyclopædia Britannica "additional reading" article about Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Marlborough, Sarah Churchill, Duchess of 1660 births 1744 deaths 18th-century English people 17th-century English women 17th-century English people 18th-century British women writers 18th-century British writers British and English royal favourites English duchesses by marriage English letter writers Women letter writers British maids of honour Mistresses of the Robes to Anne, Queen of Great Britain German countesses German princesses People from St Albans People from Old Windsor People from Woodstock, Oxfordshire

Anne, Queen of Great Britain

Anne (6 February 1665 – 1 August 1714) was Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland from 8 March 1702 until 1 May 1707. On 1 May 1707, under the Acts of Union, the kingdoms of England and Scotland united as a single sovereign state known a ...

. Churchill's relationship and influence with Princess Anne were widely known, and leading public figures often turned their attentions to her, hoping for favour from Anne. By the time Anne became queen, the Duchess of Marlborough's knowledge of government and intimacy with the Queen had made her a powerful friend and a dangerous enemy.

Churchill enjoyed a "long and devoted" relationship with her husband of more than 40 years, the great general John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough

General John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, 1st Prince of Mindelheim, 1st Count of Nellenburg, Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, (26 May 1650 – 16 June 1722 O.S.) was an English soldier and statesman whose career spanned the reig ...

. After Anne's father, King James II

James VII and II (14 October 1633 16 September 1701) was King of England and King of Ireland as James II, and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II, on 6 February 1685. He was deposed in the Glorious Re ...

, was deposed during the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

, Sarah Churchill acted as Anne's agent, promoting her interests during the reigns of William III and Mary II

Mary II (30 April 166228 December 1694) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland, co-reigning with her husband, William III & II, from 1689 until her death in 1694.

Mary was the eldest daughter of James, Duke of York, and his first wife ...

. When Anne came to the throne after William's death in 1702, the Duke of Marlborough, together with Sidney Godolphin, 1st Earl of Godolphin

Sidney Godolphin, 1st Earl of Godolphin, (15 June 1645 – 15 September 1712) was a leading British politician of the late 17th and the early 18th centuries. He was a Privy Councillor and Secretary of State for the Northern Department bef ...

, rose to head the government partly owing to his wife.

While the Duke of Marlborough was fighting the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phi ...

, the Duchess kept him informed of court intrigue and conveyed his requests and political advice to the Queen. The Duchess campaigned tirelessly on behalf of the Whigs, while also devoting herself to building projects such as Blenheim Palace

Blenheim Palace (pronounced ) is a country house in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, England. It is the seat of the Dukes of Marlborough and the only non-royal, non- episcopal country house in England to hold the title of palace. The palace, on ...

. A strong-willed woman, she strained her relationship with the Queen whenever they disagreed on political, court, or church appointments. After her final break with Anne in 1711, the Duke and Duchess were dismissed from Court, but the Duchess had her revenge under the Hanoverian kings following Anne's death. She later had famous disagreements with many important people, including her daughter Henrietta Godolphin, 2nd Duchess of Marlborough

Henrietta Godolphin, 2nd Duchess of Marlborough (19 July 1681 – 24 October 1733) was the daughter of John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, general of the army, and Sarah Jennings, Duchess of Marlborough, close friend and business manager o ...

; the architect of Blenheim Palace, John Vanbrugh

Sir John Vanbrugh (; 24 January 1664 (baptised) – 26 March 1726) was an English architect, dramatist and herald, perhaps best known as the designer of Blenheim Palace and Castle Howard. He wrote two argumentative and outspoken Restorat ...

; Prime Minister Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, (26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745; known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole) was a British statesman and Whig politician who, as First Lord of the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Lea ...

; King George II; and his wife, Queen Caroline. The money she inherited from the Marlborough trust

Trust often refers to:

* Trust (social science), confidence in or dependence on a person or quality

It may also refer to:

Business and law

* Trust law, a body of law under which one person holds property for the benefit of another

* Trust (bus ...

left her one of the richest women in Europe. She died in 1744, aged 84.

Early life

Sarah Jennings was born on 5 June 1660, probably at Holywell House,St Albans

St Albans () is a cathedral city in Hertfordshire, England, east of Hemel Hempstead and west of Hatfield, north-west of London, south-west of Welwyn Garden City and south-east of Luton. St Albans was the first major town on the old Rom ...

, Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For gover ...

. She was the daughter of Richard Jennings (or Jenyns), a Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

, and Frances Thornhurst. Her paternal grandfather was Sir John Jennings, father of an extraordinarily large family by his wife Alice Spencer. Her uncle Martin Lister

Martin Lister FRS (12 April 1639 – 2 February 1712) was an English naturalist and physician. His daughters Anne and Susanna were two of his illustrators and engravers.

J. D. Woodley, ‘Lister , Susanna (bap. 1670, d. 1738)’, Oxford Dic ...

was a prominent naturalist.

Richard Jennings came into contact with James, Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of English (later British) monarchs. The equivalent title in the Scottish peerage was Du ...

(the future James II, brother of King Charles II), in 1663, during negotiations for the recovery of an estate in Kent ( Agney Court) that had been the property of his mother-in-law, Susan Lister (''née'' Temple). James's first impressions were favourable, and in 1664 Sarah's sister, Frances, was appointed maid of honour

A maid of honour is a junior attendant of a queen in royal households. The position was and is junior to the lady-in-waiting. The equivalent title and office has historically been used in most European royal courts.

Role

Traditionally, a queen ...

to the Duchess of York

Duchess of York is the principal courtesy title held by the wife of the duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son ...

, Anne Hyde

Anne Hyde (12 March 163731 March 1671) was Duchess of York and Albany as the first wife of James, Duke of York, who later became King James II and VII.

Anne was the daughter of a member of the English gentry – Edward Hyde (later created ...

.Field, p. 8.

Although James forced Frances to give up the post because of her marriage to a Catholic, James did not forget the family. In 1673, Sarah entered court as maid of honour to James's second wife, Mary of Modena

Mary of Modena ( it, Maria Beatrice Eleonora Anna Margherita Isabella d'Este; ) was Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland as the second wife of James II and VII. A devout Roman Catholic, Mary married the widower James, who was then the younge ...

.

Sarah Jennings became close to the young Princess Anne

Anne, Princess Royal (Anne Elizabeth Alice Louise; born 15 August 1950), is a member of the British royal family. She is the second child and only daughter of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and the only sister of Ki ...

in about 1675, and the friendship grew stronger as the two grew older. In late 1675, when she was still only fifteen, she met John Churchill

General John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, 1st Prince of Mindelheim, 1st Count of Nellenburg, Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, (26 May 1650 – 16 June 1722 O.S.) was an English soldier and statesman whose career spanned the reign ...

, 10 years her senior, who fell in love with her. Churchill, who had previously been a lover of Charles II's mistress Barbara Palmer, 1st Duchess of Cleveland

Barbara Palmer, 1st Duchess of Cleveland, Countess of Castlemaine (née Barbara Villiers, – 9 October 1709), was an English royal mistress of the Villiers family and perhaps the most notorious of the many mistresses of King Charles II of E ...

, had little to offer financially, as his estates were deeply in debt. Jennings had a rival for Churchill in Catherine Sedley

Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester, Countess of Portmore (21 December 1657 – 26 October 1717), daughter of Sir Charles Sedley, 5th Baronet, was the mistress of King James II of England both before and after he came to the throne. Catheri ...

, a wealthy mistress of James II and the choice of Churchill's father, Sir Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, who was anxious to restore the family's fortune. John Churchill may have hoped to take Jennings as a mistress in place of the Duchess of Cleveland, who had recently departed for France, but surviving letters from Jennings to Churchill show her unwillingness to assume that role.

Marriage

In 1677, Jennings's brother Ralph died, and she and her sister Frances became co-heirs of the family estates in Hertfordshire and Kent. Churchill chose Sarah Jennings over Catherine Sedley, but both Churchill's and Jennings's families disapproved of the match, and therefore they married secretly in the winter of 1677–78.

John and Sarah Churchill were both Protestants in a predominantly Catholic court, a circumstance that would complicate their political allegiances. Although no date was recorded, the marriage was announced only to the Duchess of York and a small circle of friends, so that Sarah could keep her court position as Maid of Honour.

When Churchill became pregnant, her marriage was announced publicly (on 1 October 1678), and she retired from the court to give birth to her first child, Harriet, who died in infancy. When the Duke of York went into self-imposed exile to Scotland as a result of the furore surrounding the

In 1677, Jennings's brother Ralph died, and she and her sister Frances became co-heirs of the family estates in Hertfordshire and Kent. Churchill chose Sarah Jennings over Catherine Sedley, but both Churchill's and Jennings's families disapproved of the match, and therefore they married secretly in the winter of 1677–78.

John and Sarah Churchill were both Protestants in a predominantly Catholic court, a circumstance that would complicate their political allegiances. Although no date was recorded, the marriage was announced only to the Duchess of York and a small circle of friends, so that Sarah could keep her court position as Maid of Honour.

When Churchill became pregnant, her marriage was announced publicly (on 1 October 1678), and she retired from the court to give birth to her first child, Harriet, who died in infancy. When the Duke of York went into self-imposed exile to Scotland as a result of the furore surrounding the Popish Plot

The Popish Plot was a fictitious conspiracy invented by Titus Oates that between 1678 and 1681 gripped the Kingdoms of England and Scotland in anti-Catholic hysteria. Oates alleged that there was an extensive Catholic conspiracy to assassinate ...

, John and Sarah accompanied him, and Charles II rewarded John's loyalty by creating him Baron Churchill of Eyemouth

Eyemouth ( sco, Heymooth) is a small town and civil parish in Berwickshire, in the Scottish Borders area of Scotland. It is east of the main north–south A1 road and north of Berwick-upon-Tweed.

The town's name comes from its location at th ...

in Scotland. As a result, Sarah became Lady Churchill. The Duke of York returned to England after the religious tension had eased, and Sarah was appointed a Lady of the Bedchamber

Lady of the Bedchamber is the title of a lady-in-waiting holding the official position of personal attendant on a British queen regnant or queen consort. The position is traditionally held by the wife of a peer. They are ranked between the Mis ...

to Anne after the latter's marriage in 1683.

Reign of James II (1685–1688)

The early reign of James II was relatively successful; it was not expected that a Catholic king could assert control in a fiercely Protestant, anti-Catholic country. In addition, his daughter and heir was a Protestant. However, when James attempted to reform the national religion, popular discontent against him and his government became widespread. The level of alarm increased when Queen Mary gave birth to a Roman Catholic son and heir, Prince James Francis Edward, on 10 June 1688. A group of politicians known as theImmortal Seven

The ''Invitation to William'' was a letter sent by seven notable English nobles, later called "the Immortal Seven", to stadtholder William III, Prince of Orange, received by him on 30 June 1688 (Julian calendar, 10 July Gregorian calendar). In ...

invited Prince William of Orange, husband of James's Protestant daughter Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also call ...

, to invade England and remove James from power, a plan that became public knowledge very quickly. James still retained some influence, and he ordered that both Lady Churchill and Princess Anne be placed under house arrest

In justice and law, house arrest (also called home confinement, home detention, or, in modern times, electronic monitoring) is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to their residence. Travel is usually restricted, if a ...

at Anne's residence (the Cockpit

A cockpit or flight deck is the area, usually near the front of an aircraft or spacecraft, from which a pilot controls the aircraft.

The cockpit of an aircraft contains flight instruments on an instrument panel, and the controls that ena ...

) in the Palace of Whitehall

The Palace of Whitehall (also spelt White Hall) at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, except notably Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, were destroyed by fire. He ...

. Both their husbands, though previously loyal to James, had switched their allegiances to William of Orange. In her memoirs, Lady Churchill described how the two easily escaped captivity and fled to Nottingham

Nottingham ( , locally ) is a city and unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east of Sheffield and north-east of Birmingham. Nottingham has links to the legend of R ...

:

Although Churchill implied that she had encouraged the escape for the safety of Princess Anne, it is more likely that she was protecting herself and her husband.Field, pp. 54, 55. If James had succeeded in defeating Prince William of Orange in battle, he might have imprisoned and even executed Lord and Lady Churchill for treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, whereas it was unlikely he would have condemned his daughter to a similar fate. But James fled to France in December 1688 rather than confront the invading army, allowing William to take over his throne.

William III and Mary II

Life for Churchill during the reign of William and Mary was difficult. William and Mary awarded Churchill's husband the titleEarl of Marlborough

Earl of Marlborough is a title that has been created twice, both times in the Peerage of England. The first time in 1626 in favour of James Ley, 1st Baron Ley and the second in 1689 for John Churchill, 1st Baron Churchill the future Duke of Marl ...

, but the new earl and countess enjoyed considerably less favour than they had during the reign of James II. The Earl of Marlborough had supported the now exiled James, and by this time, the Countess's influence on Anne, and her cultivation of high members of the government to promote Anne's interests, was widely known. Mary II responded to this by demanding that Anne dismiss Lady Marlborough. However, Anne refused. This created a rift between Mary and Anne that never healed.

Other problems also emerged. In 1689, Anne's supporters (including the Marlboroughs and the Duke of Somerset) demanded that she be granted a parliamentary annuity

In investment, an annuity is a series of payments made at equal intervals.Kellison, Stephen G. (1970). ''The Theory of Interest''. Homewood, Illinois: Richard D. Irwin, Inc. p. 45 Examples of annuities are regular deposits to a savings account, ...

of £50,000, a sum that would end her dependence on William and Mary.Field, p. 60. The Countess of Marlborough was seen as the driving force behind this bill, creating further ill-feeling towards her at court. William responded to the demand by offering the same sum from the Privy Purse

The Privy Purse is the British Sovereign's private income, mostly from the Duchy of Lancaster. This amounted to £20.1 million in net income for the year to 31 March 2018.

Overview

The Duchy is a landed estate of approximately 46,000 acres (200 ...

to keep Anne dependent on his generosity. However, Anne, through the Countess of Marlborough, refused, pointing out that a parliamentary grant would be more secure than charity from the Privy Purse. Eventually Anne received the grant from Parliament and felt she owed this to the Countess's efforts.

The Countess's success as a leader of the opposition only intensified Queen Mary's animosity towards the Marlboroughs. Although she could not dismiss the Countess of Marlborough from Anne's service, Mary responded by evicting the Countess from her court lodgings at the Palace of Whitehall. Anne responded by leaving the court as well, and she and the Countess went to stay with their friends the Duke and Duchess of Somerset at Syon House

Syon House is the west London residence of the Duke of Northumberland. A Grade I listed building, it lies within the 200-acre (80 hectare) Syon Park, in the London Borough of Hounslow.

The family's traditional central London residence had b ...

. Anne continued to defy Mary's demand for the Countess's dismissal, even though an incriminating document signed by the Earl of Marlborough supporting the recently exiled James II and his supporters had been discovered. This document is likely to have been forged by Robert Young, a known forger and disciple of Titus Oates

Titus Oates (15 September 1649 – 12/13 July 1705) was an English priest who fabricated the "Popish Plot", a supposed Catholic conspiracy to kill King Charles II.

Early life

Titus Oates was born at Oakham in Rutland. His father Samuel (1610� ...

; Oates was famous for stirring a strongly anti-Catholic atmosphere in England between 1679 and the early 1680s.Field, pp. 79–80. The Earl was imprisoned in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

.Field, p. 79. The loneliness the Countess suffered during these events drew her and Anne closer together.

Following the death of Mary II from smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

in 1694, William III restored Anne's honours, as she was now next in line to the throne, and provided her with apartments at St. James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in London, the capital of the United Kingdom. The palace gives its name to the Court of St James's, which is the monarch's royal court, and is located in the City of Westminster in London. Altho ...

. He also restored the Earl of Marlborough to all his offices and honours and exonerated him from any past accusations. However, fearing the Countess's powerful influence, William kept Anne out of government affairs, and he did not make her regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

in his absences though she was now his heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

.

Power behind the throne: Queen Anne

In 1702, William III died, and Anne became queen. Anne immediately offered John Churchill a dukedom, which Sarah initially refused. Sarah was concerned that a dukedom would strain the family's finances; a ducal family at the time was expected to show off its rank through lavish entertainments. Anne countered by offering the Marlboroughs a

In 1702, William III died, and Anne became queen. Anne immediately offered John Churchill a dukedom, which Sarah initially refused. Sarah was concerned that a dukedom would strain the family's finances; a ducal family at the time was expected to show off its rank through lavish entertainments. Anne countered by offering the Marlboroughs a pension

A pension (, from Latin ''pensiō'', "payment") is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payments ...

of £5,000 a year for life from Parliament, as well as an extra £2,000 a year from the Privy Purse, and they accepted the dukedom. The Duchess of Marlborough was promptly created Mistress of the Robes

The mistress of the robes was the senior lady in the Royal Household of the United Kingdom.

Formerly responsible for the queen consort's/regnant's clothes and jewellery (as the name implies), the post had the responsibility for arranging the rota o ...

(the highest office in the royal court that could be held by a woman), Groom of the Stool

The Groom of the Stool (formally styled: "Groom of the King's Close Stool") was the most intimate of an English monarch's courtiers, responsible for assisting the king in excretion and hygiene.

The physical intimacy of the role naturally led t ...

, Keeper of the Privy Purse

The Keeper of the Privy Purse and Treasurer to the King/Queen (or Financial Secretary to the King/Queen) is responsible for the financial management of the Royal Household of the Sovereign of the United Kingdom. The officeholder is assisted by th ...

, and Ranger of Windsor Great Park

The office of Ranger of Windsor Great Park was established to oversee the protection and maintenance of the Great Park at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. The ranger has always been somebody close to the monarch.

Apart from a single ...

. She was the first of only two women ever to be Keeper of the Privy Purse and the only woman ever to be Ranger of Windsor Great Park. As Keeper of the Privy Purse, she was replaced by the only other woman to hold the position: her cousin and rival Abigail Masham, Baroness Masham

Abigail Masham, Baroness Masham (née Hill; 6 December 1734), was an English courtier. She was a favourite of Queen Anne, and a cousin of Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough.

Life Early life

Abigail Hill was the daughter of Francis Hill, a London m ...

. The Duke accepted the Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. It is the most senior order of knighthood in the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British honours system, outranked in ...

as well as the office of Captain-General

Captain general (and its literal equivalent in several languages) is a high military rank of general officer grade, and a gubernatorial title.

History

The term "Captain General" started to appear in the 14th century, with the meaning of Comman ...

of the army.

During much of Anne's reign, the Duke of Marlborough was abroad fighting the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phi ...

, while the Duchess remained in England. Despite being the most powerful woman in England besides the Queen, she appeared at court only rarely, preferring to oversee the construction of her new estate, Woodstock

Woodstock Music and Art Fair, commonly referred to as Woodstock, was a music festival held during August 15–18, 1969, on Max Yasgur's dairy farm in Bethel, New York, United States, southwest of the town of Woodstock, New York, Woodstock. ...

Manor (the site of the later Blenheim Palace

Blenheim Palace (pronounced ) is a country house in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, England. It is the seat of the Dukes of Marlborough and the only non-royal, non- episcopal country house in England to hold the title of palace. The palace, on ...

), a gift from Queen Anne after the Duke's victory at the Battle of Blenheim

The Battle of Blenheim (german: Zweite Schlacht bei Höchstädt, link=no; french: Bataille de Höchstädt, link=no; nl, Slag bij Blenheim, link=no) fought on , was a major battle of the War of the Spanish Succession. The overwhelming Allied v ...

. Nevertheless, Anne sent her news of political developments in letters and consulted the Duchess's advice in most matters.

The Duchess was famous for telling the Queen exactly what she thought, and did not offer her flattery. The two women had invented pet names for themselves during their youth which they continued to use after Anne became queen: ''Mrs Freeman'' (Sarah) and ''Mrs Morley'' (Anne). Effectively a business manager, the Duchess had control over the Queen's position, from her finances to people admitted to the royal presence.

Wavering influence

Anne, however, expected kindness and compassion from her closest friend. The Duchess was not forthcoming in this regard and frequently overpowered and dominated Anne. One major political disagreement occurred when the Duchess insisted that her son-in-lawCharles Spencer, 3rd Earl of Sunderland

Charles Spencer, 3rd Earl of Sunderland, KG, PC (23 April 167519 April 1722), known as Lord Spencer from 1688 to 1702, was an English statesman and nobleman from the Spencer family. He served as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (1714–1717), Lord P ...

, be admitted into the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the m ...

. The Duchess allied herself more strongly with the Whigs, who supported the Duke of Marlborough in the war, and the Whigs hoped to utilise the Duchess's position as royal favourite.

Anne refused to appoint Sunderland. She disliked the radical Whigs, whom she saw as a threat to her royal prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, privilege and immunity, recognized in common law and, sometimes, in civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy, as belonging to the sovereign and which have become widely vested in t ...

.Field, pp. 111–112. The Duchess used her close friendship with Sidney Godolphin, 1st Earl of Godolphin

Sidney Godolphin, 1st Earl of Godolphin, (15 June 1645 – 15 September 1712) was a leading British politician of the late 17th and the early 18th centuries. He was a Privy Councillor and Secretary of State for the Northern Department bef ...

, whom Anne trusted, to eventually secure such appointments, but continued to lobby Anne herself. She sent Whig reading materials to Anne in an attempt to win her over to her own preferred political party. In 1704, Anne confided to Lord Godolphin that she did not think she and the Duchess of Marlborough could ever be true friends again.

Clash of personalities

The Duchess's frankness and indifference for rank, so admired by Anne earlier in their friendship, was now seen to be intrusive. The Duchess had a powerful intimacy with the two most powerful men in the country, the Duke of Marlborough (her husband) and the Earl of Godolphin. Godolphin, though a great friend of the Duchess, had considered refusing high office after Anne's accession, preferring to live quietly and away from the Duchess of Marlborough's political side. The Earl considered the Duchess (as a powerful and intelligent woman) bossy, interfering, and presuming to tell him what to do when the Duke was away.

The Duchess, although a woman in a man's world of national and international politics, was always ready to give her advice, express her opinions, antagonize with outspoken censure, and insist on having her say on every possible occasion.Hibbert, p. 312 However, she had a charm and vivaciousness admired by many, and she could easily delight those she met with her wit.

Anne's apparent withdrawal of genuine affection occurred for a number of reasons. She was frustrated by the Duchess of Marlborough's long absences from court and despite numerous letters from Anne to the Duchess on this subject, the Duchess rarely attended. There was also a political difference between them: the Queen was a

The Duchess's frankness and indifference for rank, so admired by Anne earlier in their friendship, was now seen to be intrusive. The Duchess had a powerful intimacy with the two most powerful men in the country, the Duke of Marlborough (her husband) and the Earl of Godolphin. Godolphin, though a great friend of the Duchess, had considered refusing high office after Anne's accession, preferring to live quietly and away from the Duchess of Marlborough's political side. The Earl considered the Duchess (as a powerful and intelligent woman) bossy, interfering, and presuming to tell him what to do when the Duke was away.

The Duchess, although a woman in a man's world of national and international politics, was always ready to give her advice, express her opinions, antagonize with outspoken censure, and insist on having her say on every possible occasion.Hibbert, p. 312 However, she had a charm and vivaciousness admired by many, and she could easily delight those she met with her wit.

Anne's apparent withdrawal of genuine affection occurred for a number of reasons. She was frustrated by the Duchess of Marlborough's long absences from court and despite numerous letters from Anne to the Duchess on this subject, the Duchess rarely attended. There was also a political difference between them: the Queen was a Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

(the party known as the "Church party", religion being one of Anne's chief concerns), and the Duchess was a Whig (the party known to support Marlborough's wars).

The Duchess did not share Anne's deep interest in religion, a subject she rarely mentioned, although at their last fraught interview she did warn Anne that she risked God's vengeance for her unreasoning cruelty to the Duchess. The Queen did not want this difference to come between them, but the Duchess, always thinking of her husband, wanted Anne to give more support to the Whigs, which she was not prepared to do.

The Duchess of Marlborough was called to Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge beca ...

in 1703, where her only surviving son, John, Marquess of Blandford, was taken ill with smallpox. The Duke was recalled from the war and was at his bedside when he died on 20 February 1703. The Duchess was heartbroken over the loss of her son and became reclusive for a period, expressing her grief by closing herself off from Anne and either not answering her letters or doing so in a cold and formal manner. However, the Duchess did not allow Anne to shut her out when Anne suffered bereavement.

After the death of Anne's husband, Prince George of Denmark

Prince George of Denmark ( da, Jørgen; 2 April 165328 October 1708) was the husband of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. He was the consort of the British monarch from Anne's accession on 8 March 1702 until his death in 1708.

The marriage of Geor ...

, in 1708, the Duchess arrived, uninvited, at Kensington Palace to find Anne with the prince's body. She pressed the heartbroken Queen to move from Kensington to St James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in London, the capital of the United Kingdom. The palace gives its name to the Court of St James's, which is the monarch's royal court, and is located in the City of Westminster in London. Alt ...

in London, which Anne bluntly refused, and instead commanded the Duchess to call Abigail Masham to attend her. Aware that Masham was gaining more influence with Anne, the Duchess disobeyed the Queen, and instead scolded her for grieving over Prince George's death. Although Anne eventually submitted and allowed herself to be taken to St James's Palace, the Duchess's insensitivity greatly offended her and added to the already significant strain on the relationship.

Fall from grace

Abigail Masham: political rival

The Duchess of Marlborough had previously introduced her impoverished cousin, then known as Abigail Hill, to court, with the intention of finding a role for her. Abigail, the eldest daughter of the Duchess's aunt, Elizabeth Hill (Jennings), was working as a servant to Sir John Rivers ofKent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it fac ...

when the Duchess first learned of her existence. Because the Duchess's grandfather Sir John Jennings had fathered twenty-two children, she had a multitude of cousins and did not know them all. Out of kindness and a sense of family solidarity, she gave Abigail Hill employment within her own household at St Albans, and after a tenure of satisfactory service, Hill was made a Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Anne in 1704. The Duchess later claimed in her memoirs that she had raised Hill "in all regards as a sister", though there were implications that she only assisted her cousin out of embarrassment of her difficult circumstances.

Hill was also a second cousin, on her father's side, to the Tory leader Robert Harley, later first Earl of Oxford and Mortimer

Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer was a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1711 for the statesman Robert Harley, with remainder, failing heirs male of his body, to those of his grandfather, Sir Robert Harley. He was made ...

. Flattering, subtle and retiring, Hill was the complete opposite of the Duchess of Marlborough, who was dominating, blunt and scathing. During the Duchess's frequent absences from court, Hill and Anne grew close. Not only was Hill happy to give the Queen the kindness and compassion that Anne had longed for from the Duchess, she also never pressured the Queen about politics. Anne responded with pathos to Hill's flattery and charm. She was present at Hill's secret wedding, in 1707, to Samuel Masham, groom of the bedchamber to Prince George, without the Duchess's knowledge.Field, p. 178.

The Duchess was completely oblivious to any friendship between Anne and Abigail Masham and was therefore surprised when she discovered that Abigail frequently saw the Queen in private. The Duchess found out about Masham's marriage several months after it had occurred and immediately went to see Anne with the intention of informing her of the event. It was at that interview that Anne let slip that she had begged Masham to tell the Duchess of the marriage, and the Duchess became suspicious about what had really happened. After questioning servants and the Royal Household for a week about Masham's marriage, the Duchess discovered that the Queen had been present and had given Abigail a dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment ...

of £2,000 from the Privy Purse. That proved to the Duchess that Anne was duplicitous. Despite being Keeper of the Privy Purse, the Duchess had been unaware of any such payment.

Strained relationship

In July 1708, the Duke of Marlborough and his allyPrince Eugene of Savoy

Prince Eugene Francis of Savoy–Carignano, (18 October 1663 – 21 April 1736) better known as Prince Eugene, was a field marshal in the army of the Holy Roman Empire and of the Austrian Habsburg dynasty during the 17th and 18th centuries. H ...

won a great victory at the Battle of Oudenarde

The Battle of Oudenarde, also known as the Battle of Oudenaarde, was a major engagement of the War of the Spanish Succession, pitting a Grand Alliance force consisting of eighty thousand men under the command of the Duke of Marlborough and Pr ...

. On the way to the thanksgiving service at St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a G ...

, the Duchess of Marlborough engaged in a furious argument with the Queen about the jewels Anne wore to the service, and showed her a letter from the Duke which expressed hope that the Queen would make good political use of the victory. The implication that she should publicly express her support for the Whigs offended Anne; at the service the Duchess told the Queen to "be quiet" after Anne continued the argument, thus offending the Queen still further.

Anne's next letter to the Duchess was an exercise in chilling hostility, referring sarcastically to the "command" the Duchess had given her to be silent. As a result the Duchess, who rarely admitted that she was in the wrong, for once realised that she had gone too far and apologised for her rudeness, but her apology had little effect. Anne wrote to the Duke of Marlborough, encouraging him not to let her rift with the Duchess become public knowledge, but he could not prevent his wife's indiscretion.

The Duchess continued vehemently supporting the Whigs in writing and speaking to Anne, with the support of Godolphin and the other Whig ministers. The news of the public's support for the Whigs reached the Duke in letters from the Duchess and Godolphin, which influenced the Duke's political advice to the Queen. Anne, already in ill health, felt used and harassed and was desperate for escape. She found refuge in the gentle and quiet comfort of Abigail Masham.

Anne had explained before that she did not wish the public to know that her relationship with the Duchess of Marlborough was failing, because any sign that the Duchess was out of favour would have a damaging impact on the Duke's authority as captain-general

Captain general (and its literal equivalent in several languages) is a high military rank of general officer grade, and a gubernatorial title.

History

The term "Captain General" started to appear in the 14th century, with the meaning of Comman ...

. The Duchess was kept in all of her offices – purely for the sake of her husband's position as Captain-General of the army – and the tension between the two women lingered until early in 1711. This year was to see the end of their relationship for good.

The Duchess had always been jealous of Anne's affection for Abigail Masham after she learned of it. With the Duke of Marlborough and most of the Whig party, she had tried to force Anne to dismiss Masham. All these attempts failed, even when Anne was threatened with an official parliamentary demand from the Whigs, who were suspicious of Masham's Tory influence with Anne. The whole scenario echoed Anne's refusal to give up Sarah Churchill during the reign of William and Mary, but the threat of parliamentary interference exceeded anything tried against Anne in the 1690s.

Anne was ultimately triumphant; she conducted interviews with high-ranking politicians of both political parties and begged them "with tears in her eyes" to oppose the motion. The general view was that the Marlboroughs had made themselves look ridiculous over a trivial matter – since when, it was asked, did Parliament address the Queen on whom she should employ in her bedchamber?

The passion Anne showed for Masham, and the Queen's stubborn refusal to dismiss her, angered the Duchess to the point that she implied that a lesbian affair was taking place between the two women. During the mourning period for Anne's husband, the Duchess was the only one who refused to wear suitable mourning clothes. This gave the impression that she did not consider Anne's grief over his death to be genuine. Eventually, because of the mass support for peace in the War of the Spanish Succession, Anne decided she no longer needed the Duke of Marlborough and took the opportunity to dismiss him on trumped-up charges of embezzlement

Embezzlement is a crime that consists of withholding assets for the purpose of conversion of such assets, by one or more persons to whom the assets were entrusted, either to be held or to be used for specific purposes. Embezzlement is a type ...

.

Final dismissal

The Duchess's last attempt to re-establish her friendship with Anne came in 1710 when they had their final meeting. An account written by the Duchess shortly afterwards shows that she pleaded to be given an explanation of why their friendship was at an end, but Anne was unmoved, coldly repeating a few set phrases such as "I shall make no answer to anything you say" and "you may put it in writing".

The Duchess was so appalled by the Queen's "inhuman" conduct that she was reduced to tears, and most unusually for a woman who rarely spoke of religion, ended by threatening the Queen with the judgment of God. Anne replied that God's judgment on her concerned herself only, but later admitted that this was the one remark from the Duchess that hurt her deeply.

After hearing this, the Duke of Marlborough, realising that Anne intended to dismiss him and his wife, begged the Queen to keep them in their offices for nine months until the campaign was over, so that they could retire honourably. However, Anne told the Duke that "for her nne'shonour" the Duchess was to resign immediately and return her gold key – the symbol of her authority within the royal household – within two days.Field, p. 287. Years of trying the Queen's patience finally had resulted in her dismissal. When told the news, the Duchess, in a fit of pride, told the Duke to return the key to the Queen immediately.

In January 1711, the Duchess of Marlborough lost the offices of Mistress of the Robes and

The Duchess's last attempt to re-establish her friendship with Anne came in 1710 when they had their final meeting. An account written by the Duchess shortly afterwards shows that she pleaded to be given an explanation of why their friendship was at an end, but Anne was unmoved, coldly repeating a few set phrases such as "I shall make no answer to anything you say" and "you may put it in writing".

The Duchess was so appalled by the Queen's "inhuman" conduct that she was reduced to tears, and most unusually for a woman who rarely spoke of religion, ended by threatening the Queen with the judgment of God. Anne replied that God's judgment on her concerned herself only, but later admitted that this was the one remark from the Duchess that hurt her deeply.

After hearing this, the Duke of Marlborough, realising that Anne intended to dismiss him and his wife, begged the Queen to keep them in their offices for nine months until the campaign was over, so that they could retire honourably. However, Anne told the Duke that "for her nne'shonour" the Duchess was to resign immediately and return her gold key – the symbol of her authority within the royal household – within two days.Field, p. 287. Years of trying the Queen's patience finally had resulted in her dismissal. When told the news, the Duchess, in a fit of pride, told the Duke to return the key to the Queen immediately.

In January 1711, the Duchess of Marlborough lost the offices of Mistress of the Robes and Groom of the Stole

The Groom of the Stool (formally styled: "Groom of the King's Close Stool") was the most intimate of an English monarch's courtiers, responsible for assisting the king in excretion and hygiene.

The physical intimacy of the role naturally led t ...

and was replaced by Elizabeth Seymour, Duchess of Somerset. Abigail Masham was made Keeper of the Privy Purse. This broke a promise Anne had made to distribute these court offices to the Duchess of Marlborough's children.

The Marlboroughs also lost state funding for Blenheim Palace, and the building came to a halt for the first time since it was begun in 1705. Now in disgrace, they left England and travelled in Europe. As a result of his success in the War of the Spanish Succession, the Duke of Marlborough was a favourite among the German courts and with the Holy Roman Empire, and the family was received in those places with full honours.

The Duchess, however, did not like being away from England and often complained that she and the Duke were received with full honours in Europe, but were in disgrace at home. The Duchess found life travelling the royal courts difficult, remarking that they were full of dull company. She took the waters at Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th ...

in Germany on account of her ill health, corresponded with those in England who could supply her with political gossip, and indulged in her fascination with Catholicism.

Revival of favour

The Duchess and Queen Anne never made up their differences, although one eyewitness claimed to have heard Anne asking whether the Marlboroughs had reached the shore, leading to rumours that she had called them home herself. Anne died on 1 August 1714 at

The Duchess and Queen Anne never made up their differences, although one eyewitness claimed to have heard Anne asking whether the Marlboroughs had reached the shore, leading to rumours that she had called them home herself. Anne died on 1 August 1714 at Kensington Palace

Kensington Palace is a royal residence set in Kensington Gardens, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in London, England. It has been a residence of the British royal family since the 17th century, and is currently the official L ...

; the Protestant Whig Privy Councillors had insisted on their right to be present, preventing Henry St. John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke

Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke (; 16 September 1678 – 12 December 1751) was an English politician, government official and political philosopher. He was a leader of the Tories, and supported the Church of England politically des ...

, from declaring for the Pretender, James Francis Edward Stuart.

The Marlboroughs returned home on the afternoon of Anne's death. The Act of Settlement 1701

The Act of Settlement is an Act of the Parliament of England that settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns to only Protestants, which passed in 1701. More specifically, anyone who became a Roman Catholic, or who married one, be ...

ensured a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

succession by passing over more than 50 stronger Catholic claimants and proclaiming Georg Ludwig, Elector of Hanover

The Electorate of Hanover (german: Kurfürstentum Hannover or simply ''Kurhannover'') was an electorate of the Holy Roman Empire, located in northwestern Germany and taking its name from the capital city of Hanover. It was formally known as ...

(the great-grandson of James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

* James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

* James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334– ...

through Georg's mother Sophia of Hanover

Sophia of Hanover (born Princess Sophia of the Palatinate; 14 October 1630 – 8 June 1714) was the Electress of Hanover by marriage to Elector Ernest Augustus and later the heiress presumptive to the thrones of England and Scotland (later Gre ...

), King George I of Great Britain

George I (George Louis; ; 28 May 1660 – 11 June 1727) was King of Great Britain and Ireland from 1 August 1714 and ruler of the Electorate of Hanover within the Holy Roman Empire from 23 January 1698 until his death in 1727. He was the first ...

.

The new reign was supported by the Whigs, who were mostly staunch Protestants. The Tories were suspected of supporting the Pretender, a Roman Catholic. George I rewarded the Whigs by forming a Whig government; at his welcome in Queen's House

Queen's House is a former royal residence built between 1616 and 1635 near Greenwich Palace, a few miles down-river from the City of London and now in the London Borough of Greenwich. It presently forms a central focus of what is now the Old ...

at Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwi ...

, he conversed with the Whigs but not with the Tories. The Duchess of Marlborough approved of his choice of Whig ministers.

King George also had a personal friendship with the Marlboroughs; the Duke had fought with him in the War of the Spanish Succession, and John and Sarah made frequent visits to the Hanoverian court during their effective exile from England. George's first words to the Duke as king of Great Britain were, "My lord Duke, I hope your troubles are now over." Marlborough was restored to his old office of Captain-General of the Army.

The Duchess was relieved to move back to England. The Duke became one of the King's close advisers, and the Duchess moved back into

The Duchess was relieved to move back to England. The Duke became one of the King's close advisers, and the Duchess moved back into Marlborough House

Marlborough House, a Grade I listed mansion in St James's, City of Westminster, London, is the headquarters of the Commonwealth of Nations and the seat of the Commonwealth Secretariat. It was built in 1711 for Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Mar ...

, where she flaunted her eldest granddaughter, Lady Henrietta Godolphin, in the hope of finding her a suitable marriage partner. Henrietta eventually married Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle-upon-Tyne

Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle upon Tyne and 1st Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne, (21 July 169317 November 1768) was a British Whig statesman who served as the 4th and 6th Prime Minister of Great Britain, his official life extended ...

, in April 1717, and the rest of the Marlboroughs' grandchildren made successful marriages.

The Duchess of Marlborough's concern for her grandchildren briefly came to a halt when in 1716 her husband had two strokes, the second of which left him without the ability to speak. The Duchess spent much of her time with him, accompanying him to Tunbridge Wells

Royal Tunbridge Wells is a town in Kent, England, southeast of central London. It lies close to the border with East Sussex on the northern edge of the High Weald, whose sandstone geology is exemplified by the rock formation High Rocks. Th ...

and Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Pla ...

, and he recovered shortly afterwards. Even after his recovery, the Duchess opened his correspondence and filtered the letters the Duke received, lest their contents precipitate another stroke.

The Duchess had a good relationship with her daughter Anne Spencer, Countess of Sunderland, whereas she later became estranged from her daughters Henrietta, Elizabeth and Mary. Heartbroken when Anne died in 1716, the Duchess kept her favourite cup and a lock of her hair and adopted the Sunderlands' youngest child, Lady Diana

Diana, Princess of Wales (born Diana Frances Spencer; 1 July 1961 – 31 August 1997) was a member of the British royal family. She was the first wife of King Charles III (then Prince of Wales) and mother of Princes William and Harry. Her ac ...

, who later became her favourite granddaughter.

Later years

The Duke of Marlborough died at Windsor in 1722, and the Duchess arranged a large funeral for him. Their daughter Henrietta became duchess in her own right. The Dowager Duchess became one of the trustees of the Marlborough estate, and she used her business sense to distribute the family fortune, including the income for her daughter Henrietta.

The Dowager Duchess's personal income was now considerable, and she used the money to invest in land; she believed this would protect her from

The Duke of Marlborough died at Windsor in 1722, and the Duchess arranged a large funeral for him. Their daughter Henrietta became duchess in her own right. The Dowager Duchess became one of the trustees of the Marlborough estate, and she used her business sense to distribute the family fortune, including the income for her daughter Henrietta.

The Dowager Duchess's personal income was now considerable, and she used the money to invest in land; she believed this would protect her from currency devaluation

In macroeconomics and modern monetary policy, a devaluation is an official lowering of the value of a country's currency within a fixed exchange-rate system, in which a monetary authority formally sets a lower exchange rate of the national curren ...

. She purchased Wimbledon manor in 1723, and rebuilt the manor house. Her wealth was so considerable that she hoped to marry her granddaughter Lady Diana Spencer to Frederick, Prince of Wales

Frederick, Prince of Wales, (Frederick Louis, ; 31 January 170731 March 1751), was the eldest son and heir apparent of King George II of Great Britain. He grew estranged from his parents, King George and Queen Caroline. Frederick was the fath ...

, for which she would pay a massive dowry of £100,000.Hibbert, p. 331.

However, Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, (26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745; known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole) was a British statesman and Whig politician who, as First Lord of the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Lea ...

, First Lord of the Treasury

The first lord of the Treasury is the head of the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury exercising the ancient office of Lord High Treasurer in the United Kingdom, and is by convention also the prime minister. This office is not equivalent to the ...

(analogous to a modern Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

), vetoed the plan. Walpole, although a Whig, had alienated the Dowager Duchess by supporting peace in Europe; she was also suspicious of his financial probity and Walpole, in turn, mistrusted the Dowager Duchess. Despite this, good relations with the royal family continued and the Dowager Duchess was occasionally invited to court by Queen Caroline, who attempted to cultivate her friendship.

Sarah Churchill was a capable business manager, unusual in a period when women were excluded from most things outside the management of their household. Her friend Arthur Maynwaring

Arthur Maynwaring or Mainwaring (9 July 1668 – 13 November 1712), of Ightfield, Shropshire, was an English official and Whig politician who sat in the English and British House of Commons from 1706 to 1712. He was also a journalist and a po ...

wrote that she was more capable of business than any man.Hibbert, p. 336. Although she never came to like Blenheim Palace – describing it as "that great heap of stones" – she became more enthusiastic about its construction and wrote to the Duke of Somerset