San Francisco plague of 1900–1904 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The San Francisco plague of 1900–1904 was an epidemic of

In the newly formed US

In the newly formed US

In January 1900, the four-masted steamship S.S. ''Australia'' laid anchor in the

In January 1900, the four-masted steamship S.S. ''Australia'' laid anchor in the  On March 11, Kinyoun's lab presented its results. Two guinea pigs and one rat died after being exposed to samples from the first victim, proving the plague was indeed in Chinatown. Without restoring the quarantine, the Board of Health inspected every building in Chinatown, and labored to disinfect the neighborhood. Property was taken and burned if it was suspected of harboring filth. Using physical violence, policemen enforced compliance with the Board of Health's directives. Angry and worried Chinese communities reacted by hiding those that were sick.Markel 2005, p. 66

On March 13, another lab animal, a monkey that was exposed to the plague, died. All of the dead animals tested positive for the plague bacteria. U.S. Surgeon General Walter Wyman informed the San Francisco doctors at the end of March 1900 that his laboratory confirmed the fact that fleas can carry the plague and transmit it to a new host.

On March 11, Kinyoun's lab presented its results. Two guinea pigs and one rat died after being exposed to samples from the first victim, proving the plague was indeed in Chinatown. Without restoring the quarantine, the Board of Health inspected every building in Chinatown, and labored to disinfect the neighborhood. Property was taken and burned if it was suspected of harboring filth. Using physical violence, policemen enforced compliance with the Board of Health's directives. Angry and worried Chinese communities reacted by hiding those that were sick.Markel 2005, p. 66

On March 13, another lab animal, a monkey that was exposed to the plague, died. All of the dead animals tested positive for the plague bacteria. U.S. Surgeon General Walter Wyman informed the San Francisco doctors at the end of March 1900 that his laboratory confirmed the fact that fleas can carry the plague and transmit it to a new host.

Allied with powerful railroad and city business interests, California governor

Allied with powerful railroad and city business interests, California governor  The clash between Gage and federal authorities intensified. Wyman instructed Kinyoun to place Chinatown under a second quarantine, as well as blocking all East Asians from entering state borders. Wyman also instructed Kinyoun to inoculate all persons of Asian heritage in Chinatown, using an experimental

The clash between Gage and federal authorities intensified. Wyman instructed Kinyoun to place Chinatown under a second quarantine, as well as blocking all East Asians from entering state borders. Wyman also instructed Kinyoun to inoculate all persons of Asian heritage in Chinatown, using an experimental  Despite the secret agreement allowing for Kinyoun's removal, Gage went back on his promise of assisting federal authorities and continued to obstruct their efforts for study and quarantine. A report issued by the State Board of Health on September 16, 1901, bolstered Gage's claims, denying the plague's outbreak.

Despite the secret agreement allowing for Kinyoun's removal, Gage went back on his promise of assisting federal authorities and continued to obstruct their efforts for study and quarantine. A report issued by the State Board of Health on September 16, 1901, bolstered Gage's claims, denying the plague's outbreak.

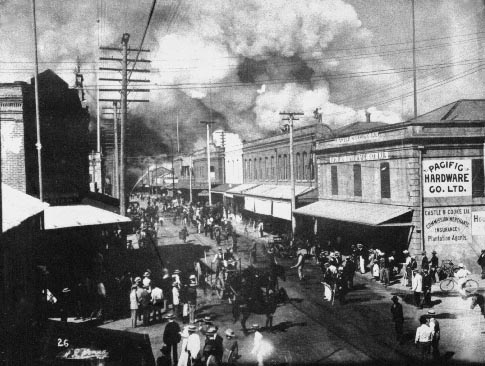

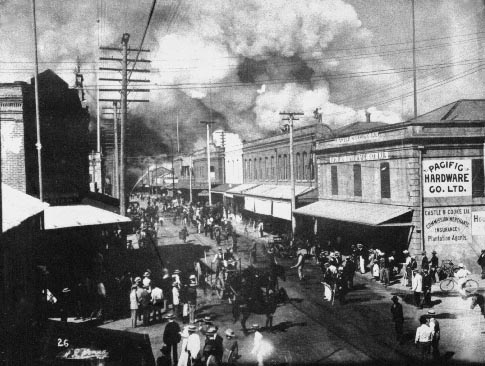

1902 Scene in Chinatown

Early Motion Pictures, Library of Congress {{DEFAULTSORT:San Francisco plague of 1900-04 1900s health disasters 1900s in California Chinatown, San Francisco Disasters in California 20th-century epidemics 1900s in San Francisco Healthcare in the San Francisco Bay Area Third plague pandemic 1900 San Francisco 1900 in California 1901 in California 1902 in California 1903 in California 1904 in California 1900 disease outbreaks 1901 disease outbreaks 1902 disease outbreaks 1903 disease outbreaks 1904 disease outbreaks 1900 disasters in the United States 1901 disasters in the United States 1902 disasters in the United States 1903 disasters in the United States 1904 disasters in the United States

bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium ('' Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as wel ...

centered on San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

's Chinatown

A Chinatown () is an ethnic enclave of Chinese people located outside Greater China, most often in an urban setting. Areas known as "Chinatown" exist throughout the world, including Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Africa and Aust ...

. It was the first plague epidemic in the continental United States

The contiguous United States (officially the conterminous United States) consists of the 48 adjoining U.S. states and the Federal District of the United States of America. The term excludes the only two non-contiguous states, Alaska and Hawaii ...

. The epidemic was recognized by medical authorities in March 1900, but its existence was denied for more than two years by California's Governor Henry Gage

Henry Tifft Gage (December 25, 1852 – August 28, 1924) was an American lawyer, politician and diplomat. A Republican, Gage was elected to a single term as the 20th governor of California from 1899 to 1903. Gage was also the U.S. Minister ...

. His denial was based on business reasons, to protect the reputations of San Francisco and California and to prevent the loss of revenue due to quarantine. The failure to act quickly may have allowed the disease to establish itself among local animal populations.Echenberg 2007, p. 237 Federal authorities worked to prove that there was a major health problem, and they isolated the affected area; this undermined Gage's credibility, and he lost the governorship in the 1902 elections. The new governor, George Pardee

George Cooper Pardee (July 25, 1857 – September 1, 1941) was an American doctor of medicine and politician. As the 21st Governor of California, holding office from January 7, 1903, to January 9, 1907, Pardee was the second native-born Californ ...

, implemented public-health measures and the epidemic was stopped in 1904. There were 121 cases identified, resulting in 119 deaths.Echenberg 2007, p. 231

Much of urban San Francisco was destroyed by a fire in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake

At 05:12 Pacific Standard Time on Wednesday, April 18, 1906, the coast of Northern California was struck by a major earthquake with an estimated moment magnitude of 7.9 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of XI (''Extreme''). High-intensity ...

, including all of the Chinatown district. The process of rebuilding began immediately but took several years. While reconstruction was in full swing, a second plague epidemic hit San Francisco in May and August 1907 but it was not centered in Chinatown. Cases occurred randomly throughout the city, including cases identified across the bay in Oakland

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third largest city overall in the Bay ...

. San Francisco's politicians and press reacted very differently this time, wanting the problem to be solved speedily. Health authorities worked quickly to assess and eradicate the disease. Approximately $2 million was spent between 1907 and 1911 to kill as many rats as possible in the city in order to control one of the disease's vectors.

In June 1908, 160 more cases had been identified, including 78 deaths, a much lower mortality rate than 1900–1904. All of the infected people were European, and the California ground squirrel

The California ground squirrel (''Otospermophilus beecheyi''), also known as the Beechey ground squirrel, is a common and easily observed ground squirrel of the western United States and the Baja California Peninsula; it is common in Oregon and ...

was identified as another vector of the disease. The initial denial of the 1900 infection may have allowed the pathogen to gain its first toehold in America, from which it spread sporadically to other states in the form of sylvatic plague (rural plague). However, it is possible that the ground squirrel infection predated 1900.

Background

The third pandemic of the plague started in 1855 in China and eventually killed about 15 million people, mainly in India. In 1894, the plague hitHong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a List of cities in China, city and Special administrative regions of China, special ...

, a major trade port between China and the US.Echenberg 2007, p. 6 US officials were worried that others would get infections from cargo carried by ships that would cross the Pacific Ocean. For these reasons, all ships were rigorously inspected. At that time, however, it was not widely known that rats could carry plague, and that fleas on those rats could transmit the disease to humans.Echenberg 2007, p. 7 Ships arriving in US ports were declared clean after inspection of the passengers showed no signs of disease. Health officials conducted no tests on rats or fleas.Echenberg 2007, p. 11 Despite important advances in the 1890s in the fight against bubonic plague, many of the world's doctors did not immediately change their ineffective and outdated methods.

In November 1898, the US Marine Hospital Service

The Marine Hospital Service was an organization of Marine Hospitals dedicated to the care of ill and disabled seamen in the United States Merchant Marine, the U.S. Coast Guard and other federal beneficiaries. The Marine Hospital Service evolv ...

(MHS) chief surgeon, James M. Gassaway, felt obliged to refute rumors of plague in San Francisco. Supported by the city's health officer, Gassaway said that some Chinese residents had died of pneumonia or lung edema, and it was not bubonic plague.

In the newly formed US

In the newly formed US Territory of Hawaii

The Territory of Hawaii or Hawaii Territory ( Hawaiian: ''Panalāʻau o Hawaiʻi'') was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from April 30, 1900, until August 21, 1959, when most of its territory, excluding ...

, the city of Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the isla ...

fell victim to the plague in December 1899. Residents of Honolulu were reporting cases of fever and swollen lymph glands forming bubo

A bubo (Greek βουβών, ''boubṓn'', 'groin') is adenitis or inflammation of the lymph nodes and is an example of reactive lymphadenopathy.

Classification

Buboes are a symptom of bubonic plague and occur as painful swellings in the thigh ...

es, with severe internal organ damage – quickly leading to death. Not knowing precisely how to control the spread of the disease, city health officials decided to burn infected houses. On January 20, 1900, changing winds fanned the flames out of control, and nearly all of Chinatown burned——leaving 6,000 without homes.

The extensive maritime operations of the port of San Francisco caused concern among medical men such as Joseph J. Kinyoun

Joseph James Kinyoun (November 25, 1860 – February 14, 1919) was an American physician and the founder of the United States' Hygienic Laboratory, the predecessor of the National Institutes of Health.

Biography

Early life

Joseph James "Jo ...

, the chief quarantine officer of the MHS in San Francisco, about the infection spreading to California. A Japanese ship, the S.S. ''Nippon Maru'', arriving in San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water f ...

in June 1899, had two plague deaths at sea, and there were two more cases of stowaways found dead in the bay, with postmortem cultures proving they had the plague. In New York in November 1899, the British ship ''J.W. Taylor'' brought three cases of plague from Brazil, but the cases were confined to the ship. The Japanese freighter S.S. ''Nanyo Maru'' arrived in Port Townsend, Washington

Port Townsend is a city on the Quimper Peninsula in Jefferson County, Washington, United States. The population was 10,148 at the 2020 United States Census.

It is the county seat and only incorporated city of Jefferson County. In addition t ...

, on January 30, 1900, with 3 deaths out of 17 cases of confirmed plague. All of these ships were quarantined; they are not known to have infected the general population. However, it is possible that plague escaped some unknown ship by way of fleas or rats, later to infect US residents.

In this atmosphere of grave danger, January 1900, Kinyoun ordered all ships coming to San Francisco from China, Japan, Australia and Hawaii to fly yellow flags to warn of possible plague on board.Chase 2003, p. 18 Many entrepreneurs and sailing men felt that this was bad for business, and unfair to ships that were free of plague. City promoters were confident that plague could not take hold, and they were unhappy with what they saw as Kinyoun's high-handed abuse of authority. On February 4, 1900, the Sunday magazine supplement of the ''San Francisco Examiner

The ''San Francisco Examiner'' is a newspaper distributed in and around San Francisco, California, and published since 1863.

Once self-dubbed the "Monarch of the Dailies" by then-owner William Randolph Hearst, and flagship of the Hearst Corporat ...

'' carried an article titled "Why San Francisco Is Plague-Proof". Certain American experts held the mistaken belief that a rice-based diet left Asians with a lower resistance to plague, and that a diet of meat kept Europeans

Europeans are the focus of European ethnology, the field of anthropology related to the various ethnic groups that reside in the states of Europe. Groups may be defined by common genetic ancestry, common language, or both. Pan and Pfeil (20 ...

free from this disease.

Infection

In January 1900, the four-masted steamship S.S. ''Australia'' laid anchor in the

In January 1900, the four-masted steamship S.S. ''Australia'' laid anchor in the Port of San Francisco

The Port of San Francisco is a semi-independent organization that oversees the port facilities at San Francisco, California, United States. It is run by a five-member commission, appointed by the Mayor and approved by the Board of Supervisors. Th ...

. The ship sailed between Honolulu and San Francisco regularly, and its passengers and crew were declared clean. Cargo from Honolulu, unloaded at a dock near the outfall of Chinatown's sewers, may have allowed rats carrying the plague to leave the ship and transmit the infection. However, it is difficult to trace the infection to a single vessel. Wherever it came from, the disease was soon established in the cramped Chinese ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished ...

neighborhood; a sudden increase in dead rats was observed as local rats became infected.

Rumors of the plague's presence abounded in the city, quickly gaining the notice of authorities from MHS stationed on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water f ...

, including Chief Kinyoun.

A Chinese American named Chick Gin, Wing Chung Ging or Wong Chut King became the first official plague victim in California.Echenberg 2007, p. 214Chase 2003, p. 17 The 41-year-old man, born in China and a San Francisco resident for 16 years, was a bachelor living in the basement of the Globe Hotel in Chinatown, at the intersection of the streets now called Grant and Jackson. The Globe Hotel was built in 1857, with the appearance of an Italian palazzo. However, by the mid-1870s it was a squalid tenement crowded with Chinese residents. Just outside, Jackson Street was the Chinese red-light district, where unmarried men could visit "hundred-men's-wives".

On February 7, 1900, Wong Chut King, the owner of a lumber yard, fell sick with what the Chinese doctors thought was typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure. ...

or gonorrhea

Gonorrhea, colloquially known as the clap, is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the bacterium ''Neisseria gonorrhoeae''. Infection may involve the genitals, mouth, or rectum. Infected men may experience pain or burning with u ...

, the latter a sexually transmitted disease

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and or ...

common to Chinatown's residents at that time. After failed medications and no relief for his illness, he died in his bed after suffering for four weeks. In the morning, the body was taken to a Chinese undertaker, where it was examined by San Francisco police surgeon Frank P. Wilson on March 6, 1900. Wilson called for A.P. O'Brien, a city health department officer, after finding suspiciously swollen lymph glands. Wilson and O'Brien then summoned Wilfred H. Kellogg, San Francisco's city bacteriologist, and the three men performed an autopsy as night closed. Looking through his microscope, Kellogg thought he saw plague bacilli.

Late at night, Kellogg ran the suspicious samples of lymph fluid to Angel Island to be tested on animals in Kinyoun's better-equipped laboratory – an operation that would take at least four days. Meanwhile, Wilson and O'Brien called upon the city's Board of Health and insisted that Chinatown be quarantined immediately.Shah 2001, p. 120

When dawn came on March 7, 1900, Chinatown was circled by rope and surrounded by policemen preventing egress or access to anyone but Whites. The 12-block area was bordered by four streets: Broadway, Kearney, California and Stockton. Approximately 25,000–35,000 residents were unable to leave. Chinese Consul General Ho Yow

Ho Yow () served as Chinese consulate general of San Francisco during a part of the San Francisco plague. His service as consulate general lasted from 1887 to 1902. Ho Yow was born in Hong Kong to a wealthy Guangzhou family. After a British edu ...

felt that the quarantine was likely based on false assumptions and that it was entirely unfair to Chinese people and would seek an injunction to lift the quarantine.Markel 2005, p. 65 San Francisco mayor James D. Phelan was in favor of keeping the Chinese-speaking residents separated from the Anglo-Americans – claiming that Chinese Americans were unclean, filthy, and "a constant menace to the public health."

Nevertheless, the Board of Health lifted the quarantine on March 9 after it had been in force for only 2½ days. O'Brien said, by way of explanation, that "the general clamor had become too great to ignore". The animals tested in Kinyoun's lab seemed to be in normal conditions after the first 48 hours of being exposed to the possible plague-causing agents. The lack of early response cast doubt on the theory that plague was the cause of Wong Chut King's death.

On March 11, Kinyoun's lab presented its results. Two guinea pigs and one rat died after being exposed to samples from the first victim, proving the plague was indeed in Chinatown. Without restoring the quarantine, the Board of Health inspected every building in Chinatown, and labored to disinfect the neighborhood. Property was taken and burned if it was suspected of harboring filth. Using physical violence, policemen enforced compliance with the Board of Health's directives. Angry and worried Chinese communities reacted by hiding those that were sick.Markel 2005, p. 66

On March 13, another lab animal, a monkey that was exposed to the plague, died. All of the dead animals tested positive for the plague bacteria. U.S. Surgeon General Walter Wyman informed the San Francisco doctors at the end of March 1900 that his laboratory confirmed the fact that fleas can carry the plague and transmit it to a new host.

On March 11, Kinyoun's lab presented its results. Two guinea pigs and one rat died after being exposed to samples from the first victim, proving the plague was indeed in Chinatown. Without restoring the quarantine, the Board of Health inspected every building in Chinatown, and labored to disinfect the neighborhood. Property was taken and burned if it was suspected of harboring filth. Using physical violence, policemen enforced compliance with the Board of Health's directives. Angry and worried Chinese communities reacted by hiding those that were sick.Markel 2005, p. 66

On March 13, another lab animal, a monkey that was exposed to the plague, died. All of the dead animals tested positive for the plague bacteria. U.S. Surgeon General Walter Wyman informed the San Francisco doctors at the end of March 1900 that his laboratory confirmed the fact that fleas can carry the plague and transmit it to a new host.

Denial and suppression by governor

Allied with powerful railroad and city business interests, California governor

Allied with powerful railroad and city business interests, California governor Henry Gage

Henry Tifft Gage (December 25, 1852 – August 28, 1924) was an American lawyer, politician and diplomat. A Republican, Gage was elected to a single term as the 20th governor of California from 1899 to 1903. Gage was also the U.S. Minister ...

publicly denied the existence of any pestilent outbreak in San Francisco, fearing that any word of the bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium ('' Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as wel ...

's presence would deeply damage the city's and state's economy.Chase 2003, pp. 70, 72, 79–81, 85, 115, 119–122 Supportive newspapers, such as the ''Call

Call or Calls may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Games

* Call, a type of betting in poker

* Call, in the game of contract bridge, a bid, pass, double, or redouble in the bidding stage

Music and dance

* Call (band), from Lahore, Paki ...

'', the ''Chronicle

A chronicle ( la, chronica, from Greek ''chroniká'', from , ''chrónos'' – "time") is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and ...

'' and the ''Bulletin

Bulletin or The Bulletin may refer to:

Periodicals (newspapers, magazines, journals)

* Bulletin (online newspaper), a Swedish online newspaper

* ''The Bulletin'' (Australian periodical), an Australian magazine (1880–2008)

** Bulletin Debate, ...

'', echoed Gage's denials, beginning what was to become an intense defamation campaign against quarantine officer Kinyoun. In response to the state's denial, Wyman recommended to federal Treasury Secretary Lyman J. Gage that he intervene. Secretary Gage agreed, creating a three-man commission of investigators who were respected medical scholars, experienced with identifying and treating the plague in China or India. The commission examined six San Francisco cases and conclusively determined that bubonic plague was present.

As with the findings of Kinyoun, the Treasury commission's findings were again immediately denounced by Governor Gage. Gage believed the federal government's growing presence in the matter was a gross intrusion of what he viewed as a state concern. In his retaliation, Gage denied the federal commission any use of the University of California's laboratories in Berkeley to further study the outbreak, by threatening the university's state funding. The ''Bulletin'' also attacked the federal commission, branding it as a "youthful and inexperienced trio."

The clash between Gage and federal authorities intensified. Wyman instructed Kinyoun to place Chinatown under a second quarantine, as well as blocking all East Asians from entering state borders. Wyman also instructed Kinyoun to inoculate all persons of Asian heritage in Chinatown, using an experimental

The clash between Gage and federal authorities intensified. Wyman instructed Kinyoun to place Chinatown under a second quarantine, as well as blocking all East Asians from entering state borders. Wyman also instructed Kinyoun to inoculate all persons of Asian heritage in Chinatown, using an experimental vaccine

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious or malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verified.

developed by Waldemar Haffkine, one known to have severe side effects. Spokesmen in Chinatown protested strenuously; they did not give their permission for this kind of mass experimentation. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association

The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) ( in the Western United States, Midwest, and Western Canada; 中華公所 (中华公所) ''zhōnghuá gōngsuǒ'' ( Jyutping: zung1wa4 gung1so2) in the East) is a historical Chinese associa ...

, also known as the Six Companies, filed suit on behalf of Wong Wai, a merchant who took a stance against what he perceived as a violation of his personal liberty. Not quite a class action suit, the arguments included similar wording such as complaints that all residents of Chinatown were being denied "equal protection under the law", part of the Fourteenth Amendment to the US constitution. Federal judge William W. Morrow

William W. Morrow (July 15, 1843 – July 24, 1929) was a United States representative from California, a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of California and a United States Circuit Judge ...

ruled uncharacteristically in favor of the Chinese, largely because the defense by the State of California was unable to prove that Chinese Americans were more susceptible to plague than Anglo Americans. The decision set a precedent for greater limits placed on public health authorities seeking to isolate diseased populations.

Between 1901 and 1902, the plague outbreak continued to worsen. In a 1901 address to both houses of the California State Legislature

The California State Legislature is a bicameral state legislature consisting of a lower house, the California State Assembly, with 80 members; and an upper house, the California State Senate, with 40 members. Both houses of the Legislatu ...

, Gage accused federal authorities, particularly Kinyoun, of injecting plague bacteria into cadavers

A cadaver or corpse is a dead human body that is used by medical students, physicians and other scientists to study anatomy, identify disease sites, determine causes of death, and provide tissue to repair a defect in a living human being. Stud ...

, falsifying evidence. In response to what he said to be massive scaremongering by the MHS, Gage pushed a censorship bill to gag any media reports of plague infection. The bill failed in the California State Legislature

The California State Legislature is a bicameral state legislature consisting of a lower house, the California State Assembly, with 80 members; and an upper house, the California State Senate, with 40 members. Both houses of the Legislatu ...

, yet laws to gag reports amongst the medical community succeeded in passage and were signed into law by the governor. In addition, $100,000 was allocated to a public campaign led by Gage to deny the plague's existence. Privately, however, Gage sent a special commission to Washington, D.C., consisting of Southern Pacific, newspaper and shipping lawyers to negotiate a settlement with the MHS, whereby the federal government would remove Kinyoun from San Francisco with the promise that the state would secretly cooperate with the MHS in stamping out the plague epidemic.

Despite the secret agreement allowing for Kinyoun's removal, Gage went back on his promise of assisting federal authorities and continued to obstruct their efforts for study and quarantine. A report issued by the State Board of Health on September 16, 1901, bolstered Gage's claims, denying the plague's outbreak.

Despite the secret agreement allowing for Kinyoun's removal, Gage went back on his promise of assisting federal authorities and continued to obstruct their efforts for study and quarantine. A report issued by the State Board of Health on September 16, 1901, bolstered Gage's claims, denying the plague's outbreak.

Racism and discrimination lawsuit

Widespread racism towardChinese immigrants

Overseas Chinese () refers to people of Chinese birth or ethnicity who reside outside Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. As of 2011, there were over 40.3 million overseas Chinese.

Terminology

() or ''Hoan-kheh'' () in Hokkien, ...

was socially accepted during the initial time of the Chinatown plague in the early 1900s. Standard social rights and privileges were often denied to the Chinese people, as shown in the way landlords would refuse to maintain their own property when renting to Chinese immigrants. The living conditions in the Chinatown community reflected the social norms and racial inequalities during that time for Chinese immigrants. Housing for the majority of Chinatown Chinese immigrants was not fit nor adequate for human living, but with scarce housing options and landlords unwilling to provide equal and fair housing, Chinese immigrants were left little option other than to live with such housing disparities. Discrimination against Chinese Americans culminated in two acts, the quarantine of San Francisco's Chinatown, and the permanent extension of the Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplo ...

of 1882. The extended quarantine of Chinatown was motivated more by racist images of Chinese Americans as carriers of disease than by actual evidence of the presence of Bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium ('' Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as wel ...

San Francisco's quarantine measures were explicitly discriminatory and segregatory, allowing European Americans to leave the affected area, but Chinese and Japanese Americans required a health certificate to leave the city. Residents were initially angered as those with jobs outside of San Francisco were prevented from working. Few Chinese agreed to take the inoculation, especially after press reports on May 22, 1900, that people who did agree were experiencing severe pain from the untested vaccine. On May 24, 1900, with the help of Chinese Six Companies

The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) ( in the Western United States, Midwest, and Western Canada; 中華公所 (中华公所) ''zhōnghuá gōngsuǒ'' (Jyutping: zung1wa4 gung1so2) in the East) is a historical Chinese association ...

, they hired the law firm of Reddy, Campbell, and Metson. Defendants included Joseph J. Kinyoun

Joseph James Kinyoun (November 25, 1860 – February 14, 1919) was an American physician and the founder of the United States' Hygienic Laboratory, the predecessor of the National Institutes of Health.

Biography

Early life

Joseph James "Jo ...

and all of the members of the San Francisco Board of Health. The Chinese wanted the courts to issue a provisional injunction to enforce what they argued was their constitutional right to travel outside of San Francisco. On July 3, 1900, Judge William W. Morrow

William W. Morrow (July 15, 1843 – July 24, 1929) was a United States representative from California, a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of California and a United States Circuit Judge ...

ruled that the defendants were violating the plaintiffs' Fourteenth Amendment. The ruling required that the same restrictions, if any, be applied to everyone no matter their ethnic group. The defendants did not have enough evidence to prove that the Chinese were transmitting the plague. Morrow agreed with the argument that if they were, the city would not have permitted them to roam the streets of San Francisco.

The Board then "attempted to sidestep the decision by instituting a quarantine order that avoided mention of race, but which was precisely drafted so as to encompass all of the Chinatown area of San Francisco while excluding white-owned businesses on the periphery of that area"; this effort was also struck down, with the court noting that the boundaries of the quarantine corresponded with the ethnicity of building occupants rather than the presence of the disease.

Detailed history

1900

Upon the death of Wong Chut King, the San Francisco Health Board took immediate action to prevent the spread of plague: Chinatown was quarantined. Health officials, in order to prevent the propagation of the disease, made the decision of placingChinatown

A Chinatown () is an ethnic enclave of Chinese people located outside Greater China, most often in an urban setting. Areas known as "Chinatown" exist throughout the world, including Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Africa and Aust ...

under quarantine, without any notice to the residents – targeting Chinese residents only. White Americans that were walking the streets of Chinatown were allowed to leave; everybody else was forced to stay. Physicians were restricted from crossing into Chinatown

A Chinatown () is an ethnic enclave of Chinese people located outside Greater China, most often in an urban setting. Areas known as "Chinatown" exist throughout the world, including Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Africa and Aust ...

to identify and help the sick. The Health Board had to approve whether or not any health official crossed into the quarantined area. Due to lack of evidence that the cause of death of King was plague, the quarantine was removed the day after to avoid controversy.

Kinyoun's lab confirmed the disease was bubonic plague and informed the Health Board right away. In an attempt to avoid a second controversial quarantine, the Health Board continued with a house-to-house inspection to look for possible plague infested households – disinfecting those that were thought to be at risk of infection. Participants in the house-to-house examination were mainly volunteer physicians and residents. On the contrary, other residents did not support the inspection and argued that the disinfecting plan was not being done in good faith. Believing a second quarantine would be soon implemented, worried residents began to flee quietly and hide in friends' houses outside of Chinatown

A Chinatown () is an ethnic enclave of Chinese people located outside Greater China, most often in an urban setting. Areas known as "Chinatown" exist throughout the world, including Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Africa and Aust ...

.

As days passed, more dead bodies were reported and autopsies revealed the presence of plague bacilli, indicating that a plague epidemic had hit San Francisco's Chinatown, but the health board still was trying to deny it. The health board attempted to keep all the information regarding the outbreak secret by implementing strict regulations of what physicians could write official death certificates. Nevertheless, newspapers published the news of the presence of bubonic plague in San Francisco to the entire nation, especially William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

's ''New York Journal

:''Includes coverage of New York Journal-American and its predecessors New York Journal, The Journal, New York American and New York Evening Journal''

The ''New York Journal-American'' was a daily newspaper published in New York City from 1937 t ...

'' which published a special plague edition.

The official inspection and disinfection of Chinatown finally began, thanks to the monetary contributions of the supervisors of the volunteer physicians, policemen, and inspectors that participated in the actual disinfection campaign. The sanitizing of Chinatown began to show results as the death toll slowly dropped throughout the month of March and the beginning of April. Towards the end of April, the corpse of Law An, a Chinese laborer from a village near the Sacramento River

The Sacramento River ( es, Río Sacramento) is the principal river of Northern California in the United States and is the largest river in California. Rising in the Klamath Mountains, the river flows south for before reaching the Sacramento� ...

, was found in an alley in Chinatown. The cause of death of Law An was determined to be bubonic plague. After that, a few more Chinese residents that died suddenly were determined to be infested with plague bacilli. The fear that the bubonic plague was spreading intensified.

The controversy of the vaccination program organized by Kinyoun with the help of Surgeon General Wyman spiked. The plan was to inoculate the Chinese residents with Haffkine's vaccine, a prophylactic anti-plague vaccine that was intended to provide some protection against the plague for a 6-month period. No one spoke about the side effects and that the vaccine was still not approved for humans. Most Chinese residents refused and demanded the vaccine to be tested in rats first. At first, representatives of the Chinese community had agreed that inoculating the population with such serum could be a reasonable and safe solution, but soon after agreed with the rest of the Chinese population in that it was not ethical to try the vaccine in humans first. The representatives from the Chinese Six companies

The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) ( in the Western United States, Midwest, and Western Canada; 中華公所 (中华公所) ''zhōnghuá gōngsuǒ'' (Jyutping: zung1wa4 gung1so2) in the East) is a historical Chinese association ...

demanded the vaccination program to be eliminated as an option, and with much pressure and insistence from the Chinese community the vaccination program was halted.

1901

Joseph J. Kinyoun

Joseph James Kinyoun (November 25, 1860 – February 14, 1919) was an American physician and the founder of the United States' Hygienic Laboratory, the predecessor of the National Institutes of Health.

Biography

Early life

Joseph James "Jo ...

was feeling the pressure of the public to clear his reputation. He summoned the help of U.S. Surgeon General Walter Wyman to bring someone from the outside to investigate Kinyoun's procedures. In December 1900 Wyman selected Assistant Surgeon General Joseph H. White to manage the investigation surrounding all of the Pacific Coast stations. White wanted to focus on how food was handled while being imported from China and Japan. Kinyoun tried to hinder these advances because he did not want to publicly admit that there was an outbreak. White made his appearance in January 1901. White and Kinyoun attended the autopsy of Chun Way Lung who was said to have suffered from gonorrhea. Wilfred Kellogg and Henry Ryfkogel conducted the autopsy and achieved respect from White by revealing that Lung had died from the bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium ('' Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as wel ...

. White concluded that Kinyoun's bacteriological confirmation could no longer be credible.1932–, Risse, Guenter B., (2012). Plague, fear, and politics in San Francisco's Chinatown. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 167–174. . OCLC 809317536

Governor Gage refused to support the diagnoses that were verified by the competent Pasteurians in San Francisco. Kinyoun was starting to express his frustration and suggested that independent outside experts confirm that the plague was present. White agreed and passed this information to the surgeon general. Kinyoun desired that his reputation be restored and that his findings were valid so that he could continue to investigate plague cases.

On January 26, Flexner, Novy, and Barker arrived in San Francisco. The three scientists were appointed to an official commission to prove if the plague existed.

Gage reacted by sending a telegram to President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in t ...

urging that the federal experts work with state health authorities. Gage's request was not granted because the federal government wanted the commission to be allowed to work independently. They would relay all of their findings to the treasury department and then forwarded to Gage. Flexner, Novy, and Barker scheduled an inspection of the sick and dead on February 6. The federal investigators split up the duties. Novy carried out bacteriological tests, while Barker accompanied by a Chinese interpreter visited the sick. By February 12, the team had studied six cases that all identified the characteristics of bubonic plague. This was confirmed by pathological and bacteriological data. Flexner, Novy, and Barker completed their investigation on February 16. They met with Governor Gage the same day and informed him of their conclusion.

Gage was upset and accused them of being a threat to public health. Over the next few weeks Gage questioned the diagnoses and blocked the publication of the final report. He blamed the commission of being biased and influenced by Kinyoun. Finally the two senators for California proposed that Gage needed to engage in friendly cooperation with federal authorities. Gage sent representatives to Washington to reach an agreement for federal authorities to suppress their findings concerning the plague in San Francisco. The federal authorities agreed to these demands after Gage's representatives verbally pledged to manage a sanitary campaign in Chinatown. This would be done secretively under the guidance of an expert from the Marine Hospital Service

The Marine Hospital Service was an organization of Marine Hospitals dedicated to the care of ill and disabled seamen in the United States Merchant Marine, the U.S. Coast Guard and other federal beneficiaries. The Marine Hospital Service evolv ...

This deal was designed to avoid impairing the state's reputation and economy. Surgeon general Wyman took the majority of the blame. He was accused of violating U.S. laws and breaking international agreements that required him to notify all nations that there was an existence of contagious disease. Wyman and President McKinley destroyed the credibility of the American public health in the eyes of the nation and abroad.

1902

Countering the continued denials made by San Francisco-based newspapers, reports from the ''Sacramento Bee

''The Sacramento Bee'' is a daily newspaper published in Sacramento, California, in the United States. Since its foundation in 1857, ''The Bee'' has become the largest newspaper in Sacramento, the fifth largest newspaper in California, and the 2 ...

'' and the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. new ...

describing the plague's spread, publicly announced the outbreak throughout the United States. The state governments of Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

and Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

imposed quarantines of California – arguing that since the state had refused to admit to a health crisis within its borders, states receiving rail or shipping cargo from California ports had the duty to protect themselves. Threats of a national quarantine grew.

As the 1902 general elections approached, members of the Southern Pacific board and the "Railroad Republican" faction increasingly saw Gage as an embarrassment to state Republicans. Gage's public denials of the plague outbreak were to protect the state's economy and the business interests of his political allies. However, reports from federal agencies and certain newspapers continued to prove Gage incorrect. Other states were moving to quarantine or boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict so ...

California, and the powerful shipping and rail companies sought a new leader. At the state Republican convention that year, the Railroad Republican faction refused Gage's renomination for governorship. In his place, former Mayor of Oakland

The city of Oakland, California, was founded in 1852, and was incorporated in 1854.

Until the early 20th century, all Oakland mayors served terms of only one or two years each.

Terms

* Office terms:

** 1 year 1854 – mayor elected by fellow ...

George Pardee

George Cooper Pardee (July 25, 1857 – September 1, 1941) was an American doctor of medicine and politician. As the 21st Governor of California, holding office from January 7, 1903, to January 9, 1907, Pardee was the second native-born Californ ...

, a German-trained medical physician, received the nomination. Pardee's nomination was largely a compromise between the Railroad Republican factions.

In his final speech, to the California State Legislature, in early January 1903, Gage continued to deny the outbreak. He blamed the federal government, in particular, Kinyoun, the MHS, and the San Francisco Board of Health for damaging the state's economy.

See also

*List of epidemics

This is a list of the largest known epidemics and pandemics caused by an infectious disease. Widespread non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular disease and cancer are not included. An epidemic is the rapid spread of disease to a large ...

* Chinese boycott of 1905

References

Notes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * *External links

1902 Scene in Chinatown

Early Motion Pictures, Library of Congress {{DEFAULTSORT:San Francisco plague of 1900-04 1900s health disasters 1900s in California Chinatown, San Francisco Disasters in California 20th-century epidemics 1900s in San Francisco Healthcare in the San Francisco Bay Area Third plague pandemic 1900 San Francisco 1900 in California 1901 in California 1902 in California 1903 in California 1904 in California 1900 disease outbreaks 1901 disease outbreaks 1902 disease outbreaks 1903 disease outbreaks 1904 disease outbreaks 1900 disasters in the United States 1901 disasters in the United States 1902 disasters in the United States 1903 disasters in the United States 1904 disasters in the United States