Samuel J. Randall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Samuel Jackson Randall (October 10, 1828April 13, 1890) was an American politician from

In 1862, before rejoining his cavalry unit, Randall was elected to the

In 1862, before rejoining his cavalry unit, Randall was elected to the

With Grant, a Republican, elected president in 1868, and the

With Grant, a Republican, elected president in 1868, and the

Democrats remained in the minority when the 43rd Congress convened in 1873. Randall continued his opposition to measures proposed by Republicans, especially those intended to increase the power of the federal government. That term saw the introduction of a new civil rights bill with farther-reaching ambitions than any before it. Previous acts had seen the use of federal courts and troops to guarantee that black men and women could not be deprived of their civil rights by any state. Now Senator

Democrats remained in the minority when the 43rd Congress convened in 1873. Randall continued his opposition to measures proposed by Republicans, especially those intended to increase the power of the federal government. That term saw the introduction of a new civil rights bill with farther-reaching ambitions than any before it. Previous acts had seen the use of federal courts and troops to guarantee that black men and women could not be deprived of their civil rights by any state. Now Senator

After Kerr's death, Randall was the consensus choice of the Democratic caucus, and was elected to the Speakership when Congress returned to Washington on December 2, 1876. He assumed the chair at a tumultuous time, as the presidential election had just concluded the previous month with no clear winner. The Democratic candidate, Samuel J. Tilden of New York, had 184 electoral votes, just shy of the 185 needed for victory.

After Kerr's death, Randall was the consensus choice of the Democratic caucus, and was elected to the Speakership when Congress returned to Washington on December 2, 1876. He assumed the chair at a tumultuous time, as the presidential election had just concluded the previous month with no clear winner. The Democratic candidate, Samuel J. Tilden of New York, had 184 electoral votes, just shy of the 185 needed for victory.

Randall returned to Washington in March 1877 at the start of the

Randall returned to Washington in March 1877 at the start of the

Randall's determination to cut spending, combined with Southern Democrats' desire to reduce federal power in their home states, led the House to pass an army appropriation bill with a rider that repealed the

Randall's determination to cut spending, combined with Southern Democrats' desire to reduce federal power in their home states, led the House to pass an army appropriation bill with a rider that repealed the

The tariff fight continued into the

The tariff fight continued into the

Randall's positions on tariffs and pensions had made him, according to ''

Randall's positions on tariffs and pensions had made him, according to ''

Samuel J. Randall Papers

including correspondence, congressional papers and other printed materials, are available for research use at the

Obituary for Samuel J Randall

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:Randall, Samuel J. 1828 births 1890 deaths 19th-century American politicians American Presbyterians Burials at Laurel Hill Cemetery (Philadelphia) Candidates in the 1880 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1884 United States presidential election Deans of the United States House of Representatives Deaths from cancer in Washington, D.C. Deaths from colorectal cancer Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania Democratic Party Pennsylvania state senators People of Pennsylvania in the American Civil War Philadelphia City Council members Politicians from Philadelphia Speakers of the United States House of Representatives

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

who represented the Queen Village

Queen Village is a residential neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania that lies along the eastern edge of the city in South Philadelphia. It shares boundaries with Society Hill to the north, Bella Vista to the west and Pennsport to the south ...

, Society Hill

Society Hill is a historic neighborhood in Center City Philadelphia, with a population of 6,215 . Settled in the early 1680s, Society Hill is one of the oldest residential neighborhoods in Philadelphia.The Center City District dates the Free Soc ...

, and Northern Liberties

Northern Liberties is a neighborhood in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Prior to its incorporation into Philadelphia in 1854, it was among the top 10 largest cities in the U.S. in every census from 1790 to 1850.

Boundaries

Northern Liberties is loc ...

neighborhoods of Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

from 1863 to 1890 and served as the 29th speaker of the United States House of Representatives

The speaker of the United States House of Representatives, commonly known as the speaker of the House, is the presiding officer of the United States House of Representatives. The office was established in 1789 by Article I, Section 2 of the ...

from 1876 to 1881. He was a contender for the Democratic Party nomination for President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

in 1880

Events

January–March

* January 22 – Toowong State School is founded in Queensland, Australia.

* January – The international White slave trade affair scandal in Brussels is exposed and attracts international infamy.

* February � ...

and 1884

Events

January–March

* January 4 – The Fabian Society is founded in London.

* January 5 – Gilbert and Sullivan's '' Princess Ida'' premières at the Savoy Theatre, London.

* January 18 – Dr. William Price at ...

.

Born in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

to a family active in Whig politics, Randall shifted to the Democratic Party after the Whigs' demise. His rise in politics began in the 1850s with election to the Philadelphia Common Council and then to the Pennsylvania State Senate

The Pennsylvania State Senate is the upper house of the Pennsylvania General Assembly, the Pennsylvania state legislature. The State Senate meets in the State Capitol building in Harrisburg

Harrisburg is the capital city of the Commonwealt ...

for the 1st district. Randall served in a Union cavalry unit in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

before winning a seat in the federal House of Representatives in 1862. He was re-elected every two years thereafter until his death. The representative of an industrial region, Randall became known as a staunch defender of protective tariffs

Protective tariffs are tariffs that are enacted with the aim of protecting a domestic industry. They aim to make imported goods cost more than equivalent goods produced domestically, thereby causing sales of domestically produced goods to rise, ...

designed to assist domestic producers of manufactured goods. While often siding with Republicans on tariff issues, he differed with them in his resistance to Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

and the growth of federal power.

Randall's support for smaller, less centralized government raised his profile among House Democrats, and they elevated him to Speaker in 1876. He held that post until the Democrats lost control of the House in 1881, and was considered a possible nominee for president in 1880 and 1884. Randall's support for high tariffs began to alienate him from most Democrats, and when that party regained control of the House in 1883, he was denied another term as Speaker. Randall continued to serve in Congress as chair of the Appropriations Committee. He remained a respected party leader but gradually lost influence as the Democrats became more firmly wedded to free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

. Worsening health also curtailed his power until his death in 1890.

Early life and family

Randall was born on October 10, 1828, inPhiladelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

, the eldest son of Josiah and Ann Worrell Randall. Three younger brothers soon followed: William, Robert, and Henry. Josiah Randall was a leading Philadelphia lawyer who had served in the state legislature

A state legislature is a legislative branch or body of a political subdivision in a federal system.

Two federations literally use the term "state legislature":

* The legislative branches of each of the fifty state governments of the United Sta ...

in the 1820s. Randall's paternal grandfather, Matthew Randall, was a judge on the Pennsylvania Courts of Common Pleas and county prothonotary

The word prothonotary is recorded in English since 1447, as "principal clerk of a court," from L.L. ''prothonotarius'' ( c. 400), from Greek ''protonotarios'' "first scribe," originally the chief of the college of recorders of the court of the B ...

in that city in the early 19th century. His maternal grandfather, Joseph Worrell, was also a prominent citizen, active in politics for the Democratic Party during Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

's presidency. Josiah Randall was a Whig in politics, but drifted into the Democratic fold after the Whig Party dissolved in the 1850s.

When Randall was born, the family lived at Seventh and Walnut Streets in what is now Center City Philadelphia

Center City includes the central business district and central neighborhoods of Philadelphia. It comprises the area that made up the City of Philadelphia prior to the Act of Consolidation, 1854, which extended the city borders to be coterminous wi ...

. Randall was educated at the University Academy, a school affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a Private university, private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest- ...

. On completing school at age 17, he did not follow his father into the law, but instead took a job as a bookkeeper with a local silk merchant. Shortly thereafter, he started a coal delivery business and, at age 21, became a partner in a scrap iron business named Earp and Randall.

Two years later, in 1851, Randall married Fannie Agnes Ward, the daughter of Aaron

According to Abrahamic religions, Aaron ''′aharon'', ar, هارون, Hārūn, Greek (Septuagint): Ἀαρών; often called Aaron the priest ()., group="note" ( or ; ''’Ahărōn'') was a prophet, a high priest, and the elder brother of ...

and Mary Watson Ward of Sing Sing

Sing Sing Correctional Facility, formerly Ossining Correctional Facility, is a maximum-security prison operated by the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision in the village of Ossining, New York. It is about north of ...

, New York. Randall's new father-in-law was a major general in the New York militia and had served in Congress as a Jacksonian Democrat for several terms between 1825 and 1843. Randall and Fannie went on to have three children: Ann, Susan, and Samuel Josiah.

Local politics and military service

In 1851, Randall assisted his father in the election campaign for a local judge. The judge, a Whig, was elected despite considerable opposition from a candidate of the nativist American Party (commonly called the "Know-Nothing Party"). The strength of this group, combined with the Whigs' declining fortunes, led Samuel Randall to call himself an "American Whig" when he ran for Philadelphia Common Council the following year. He was elected, holding office for four one-year terms from 1852 to 1856. The period was one of significant change in Philadelphia's governance, as all ofPhiladelphia County

Philadelphia County is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. It is the most populous county in Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 census, Philadelphia County had a population of 1,603,797. The county is the second smallest county in Pennsyl ...

's townships and boroughs were consolidated into one city in 1854.

As the Whig Party fell apart, Randall and his family became Democrats. Josiah Randall was friendly with James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

, a Pennsylvania Democrat then serving as the United States' envoy in Great Britain. Both Randall and his father attended the Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 18 ...

in 1856 to work for Buchanan's nomination for president, which was successful. When, in 1858, a vacancy occurred in Randall's state Senate

A state legislature in the United States is the legislative body of any of the 50 U.S. states. The formal name varies from state to state. In 27 states, the legislature is simply called the ''Legislature'' or the ''State Legislature'', whil ...

district, he ran for election (as a Democrat) for the remainder of the term, and was elected. Still only 30 years old, Randall had risen rapidly in politics. Much of his term in the state Senate was spent dealing with the incorporation of street railway

A tram (called a streetcar or trolley in North America) is a rail vehicle that travels on tramway tracks on public urban streets; some include segments on segregated right-of-way. The tramlines or networks operated as public transport ar ...

companies, which he believed would benefit his district. Randall also supported legislation to reduce the power of banks, a policy that he would continue to advocate for his entire political career. In 1860, he ran for election to a full term in the state Senate while his brother Robert ran for a seat in the state House of Representatives. Ignoring their father's advice that it meant "too much Randall on the ticket", both brothers were unsuccessful.

In 1861, the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

began as eleven Southern states seceded from the Union to form the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

. Randall joined the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry

The First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry, also known as the First City Troop, is a unit of the Pennsylvania Army National Guard. It is one of the oldest military units in the United States still in active service and is among the most decorat ...

in May of that year as a private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

. The unit was stationed in central Pennsylvania and eastern Virginia during Randall's 90-day enlistment, but saw no action during that time. In 1863, he re-joined the unit, this time being elected captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

. The First Troop was sent back to central Pennsylvania during the Gettysburg campaign that summer, when Confederate forces under Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nor ...

invaded Pennsylvania. He served as provost marshal

Provost marshal is a title given to a person in charge of a group of Military Police (MP). The title originated with an older term for MPs, '' provosts'', from the Old French ''prévost'' (Modern French ''prévôt''). While a provost marshal i ...

at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Gettysburg (; non-locally ) is a borough and the county seat of Adams County in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. The Battle of Gettysburg (1863) and President Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address are named for this town.

Gettysburg is home to ...

in the days before the battle there, and had the same role at Columbia, Pennsylvania

Columbia, formerly Wright's Ferry, is a borough (town) in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, United States. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 10,222. It is southeast of Harrisburg, on the east (left) bank of the Susquehanna River, ac ...

during the battle, but did not see combat. As historian Albert V. House explained, " s military career was respectable, but far from arduous, most of his duties being routine reconnoitering which seldom led him under fire."

House of Representatives

Election to the House

In 1862, before rejoining his cavalry unit, Randall was elected to the

In 1862, before rejoining his cavalry unit, Randall was elected to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

from Pennsylvania's 1st congressional district

Pennsylvania's first congressional district includes all of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, Bucks County and a sliver of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, Montgomery County in southeastern Pennsylvania. It has been represented by Brian Fitzpatrick (Am ...

.

The city had been gerrymandered

In representative democracies, gerrymandering (, originally ) is the political manipulation of electoral district boundaries with the intent to create undue advantage for a party, group, or socioeconomic class within the constituency. The m ...

by a Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

legislature to create four solidly Republican districts, with the result that as many Democrats as possible were lumped into the 1st district. Gaining the Democratic nomination was, thus, tantamount to election; Randall defeated former mayor Richard Vaux

Richard Vaux (December 19, 1816 – March 22, 1895) was an American politician. He was mayor of Philadelphia and a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania.

Early life and education

Richard Vaux was born in Philadelphia, Pen ...

for their party's endorsement and won easily over his Republican opponent, Edward G. Webb. He won with the help of William "Squire" McMullen, the Democratic boss

Boss may refer to:

Occupations

* Supervisor, often referred to as boss

* Air boss, more formally, air officer, the person in charge of aircraft operations on an aircraft carrier

* Crime boss, the head of a criminal organization

* Fire boss, a ...

of the fourth ward, who would remain a lifelong Randall ally.

Under the congressional calendar of the 1860s, members of the 38th United States Congress

The 38th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1863, ...

, elected in November 1862, did not begin their work until December 1863. Randall arrived that month, after being discharged from his cavalry unit, to join a Congress dominated by Republicans. As a member of the minority, Randall had little opportunity to author legislation, but quickly became known as a hard-working and conscientious member. James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine (January 31, 1830January 27, 1893) was an American statesman and Republican politician who represented Maine in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1863 to 1876, serving as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representati ...

, a Republican also first elected in 1862, later characterized Randall as "a strong partisan, with many elements of leadership. He... never neglects his public duties, and never forgets the interests of the Democratic Party."

Randall was known as a friend to the manufacturers in his district, especially as it concerned protective tariffs

Protective tariffs are tariffs that are enacted with the aim of protecting a domestic industry. They aim to make imported goods cost more than equivalent goods produced domestically, thereby causing sales of domestically produced goods to rise, ...

. Despite being in the minority, Randall spoke often in defense of his constituents' interests. As House described him,

With his party continually in the minority, Randall gained experience in the functioning of the House, but his tenure left little evidence in the statute book. He attracted little attention, but kept his constituents happy and was repeatedly reelected.

War and Reconstruction

When the 38th Congress convened in December 1863, the Civil War was approaching its end. Randall was aWar Democrat

War Democrats in American politics of the 1860s were members of the Democratic Party who supported the Union and rejected the policies of the Copperheads (or Peace Democrats). The War Democrats demanded a more aggressive policy toward the Con ...

, sometimes siding with his Republican colleagues to support measures in pursuit of victory over the Confederates. When a bill was proposed to allow President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

to promote Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

to lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on th ...

, Randall voted in favor, unlike most in his party. He voted with the majority of Democrats, however, to oppose allowing black men to serve in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

.

When it came to political plans for the post-war nation, he was strictly opposed to most Republican-proposed measures. Republicans proposed the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1865, which would abolish slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, and Randall spoke against it. Claiming opposition to slavery, Randall said his objections stemmed instead from a belief that the amendment was "a beginning of changes in the Constitution and the forerunner of usurpation". After Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

became president following Lincoln's assassination

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, was Assassination, assassinated by well-known stage actor John Wilkes Booth, while attending the play ''Our American Cousin'' at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C.

S ...

, Randall came to support Johnson's policies for Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

of the defeated South, which were more lenient than those of the Republican majority in Congress. In 1867, the Republicans proposed requiring an ironclad oath from all Southerners wishing to vote, hold office, or practice law in federal courts, making them swear they had never borne arms against the United States. Randall led a 16-hour filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking out ...

against the measure; in spite of his efforts, it passed.

Randall began to gain prominence in the small Democratic caucus by opposing Reconstruction measures. His delaying tactics against fellow Pennsylvanian Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

's military Reconstruction bill in February 1867 kept the bill from being considered for two weeks—long enough to prevent it from being voted on until the next session. He likewise spoke against what would become the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. Although he opposed the amendment, Randall did favor the idea behind part of it: section 4, which guarantees that Congress may not repudiate the federal debt, nor may it assume debts of the Confederacy, nor debt that the individual Confederate states incurred during the rebellion. Many Republicans claimed that if the Democrats were to regain power, they would do exactly that, repudiating federal debt and assuming that of the rebels. Despite disagreement on other facets of Reconstruction, Randall stood firmly with the Republicans (and most Northern Democrats) on the debt.

As impeachment

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

proceedings began against President Johnson, Randall became one of his leading defenders in the House. Once the House determined to impeach Johnson, Randall worked to direct the investigation to the Judiciary Committee, rather than a special committee convened for the purpose, which he believed would be stacked with pro-impeachment members. His efforts were unsuccessful, as were his speeches in favor of the president: Johnson was impeached by a vote of 128 to 47. Johnson was not convicted after his Senate trial, and Randall remained on good terms with him after the president left office.

Financial legislation

With Grant, a Republican, elected president in 1868, and the

With Grant, a Republican, elected president in 1868, and the 41st Congress

The 41st United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1869, ...

as Republican-dominated as its immediate predecessors, Randall faced several more years in the minority. He served on the Banking and Currency Committee and began to focus on financial matters, resuming his long-standing policy against the power of banks. This placed Randall in the growing fight over the nature of the nation's currency—those who favored the gold-backed currency were called "hard money" supporters, while the policy of encouraging inflation through coining silver or issuing dollars backed by government bonds (" greenbacks") was known as "soft money". Although he believed in a gold-backed dollar, Randall was friendly to greenbacks; in general, he favored allowing the amount of currency to remain constant, while replacing bank-issued dollar bills with greenbacks. He also believed the federal government should sell its bonds directly to the public, rather than selling them only to large banks, which then re-sold them at a profit. He was unsuccessful in convincing the Republican majority to adopt any of these measures.

Randall worked with Republicans to shift the source of federal funds from taxes to tariffs. He believed the taxation of alcohol spread the burdens of taxation unfairly, especially as concerned his constituents, who included several distillers. He also believed the income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Ta ...

, first enacted during the Civil War, was being administered unfairly, with large refunds often accruing to powerful business interests. On this point, Randall was successful, and the House accepted an amendment that required all cases for refunds over $500 to be tried before a federal district court

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each federal judicial district, which each cover one U.S. state or, in some cases, a portion of a state. Each district cou ...

. He also worked toward the elimination of taxation on tea, coffee, cigars, and matches, all of which Randall believed fell disproportionately on the poor. Relief from taxation made these items cheaper for the average American, while increasing reliance on tariffs helped the industrial owners and workers in Randall's district, as it made foreign products more expensive.

Tariff legislation generally found favor with Randall, which put him more often in alliance with Republicans than Democrats. In the late 1860s and early 1870s, Randall worked to raise tariffs on a wide variety of imported goods. Even so, he sometimes differed with the Republicans when he believed the tariff proposed was too high; biographer Alfred V. House describes Randall's attitude as supporting "higher tariff rates... largely because he believed that the benefits of such high rates were passed on to the labor population." In 1870, he opposed the pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate product of the iron industry in the production of steel which is obtained by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with ...

tariff as too high, against the wishes of fellow Pennsylvanian William "Pig Iron" Kelley. Randall called his version of protectionism "incidental protection": he believed tariffs should be high enough to support the cost of running the government, but applied only to those industries that needed tariff protection to survive foreign competition.

Appropriations and investigations

While the Democrats were in the minority, Randall spent much of his time scrutinizing the Republicans' appropriations bills. During theGrant administration

The presidency of Ulysses S. Grant began on March 4, 1869, when Ulysses S. Grant was inaugurated as the 18th president of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1877. The Reconstruction era took place during Grant's two terms of office. The K ...

, he questioned thousands of items in the appropriation bills, often gaining the support of Republicans in excising expenditures that were in excess of the departments' needs. He proposed a bill that would end the practice, common at the time, of executive departments spending beyond what they had been appropriated, then petitioning Congress to retroactively approve the spending with a supplemental appropriation; the legislation passed and became law. The supplemental appropriations were typically rushed through at the end of a session with little debate. Reacting to the large grants of land given to railroads, he also sought unsuccessfully to ban all land grants to private corporations.

Investigating appropriations led Randall to focus on financial impropriety in Congress and the Grant administration. The most famous of these was the Crédit Mobilier scandal

The Crédit Mobilier scandal () was a two-part fraud conducted from 1864 to 1867 by the Union Pacific Railroad and the Crédit Mobilier of America construction company in the building of the eastern portion of the First transcontinental railroad ...

. In this scheme, the Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad , legally Union Pacific Railroad Company and often called simply Union Pacific, is a freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Paci ...

bankrupted itself by overpaying its construction company, the Crédit Mobilier of America. Crédit Mobilier was owned by the railroad's principal shareholders and, as the investigation discovered, several congressmen also owned shares that they had been allowed to purchase at discounted prices. Randall's role in the investigation was limited, but he proposed bills to ban such frauds and sought to impeach Vice President Schuyler Colfax

Schuyler Colfax Jr. (; March 23, 1823 – January 13, 1885) was an American journalist, businessman, and politician who served as the 17th vice president of the United States from 1869 to 1873, and prior to that as the 25th speaker of the Hous ...

, who had been implicated in the scandal. Randall was involved with the investigation of several other scandals, as well, including tax fraud by private tax collection contractors (known as the Sanborn incident

The Sanborn incident or Sanborn contract was an American political scandal which occurred in 1874. William Adams Richardson, President Ulysses S. Grant's Secretary of the Treasury, hired a private citizen, John B. Sanborn, a former Union General ...

) and fraud in the awarding of postal contracts (the star route scandal).

Randall was caught on the wrong side of one scandal in 1873 when Congress passed a retroactive pay increase. On the last day of the term, the 42nd Congress voted to raise its members' pay by 50%, including a raise made retroactive to the beginning of the term. Randall voted for the pay raise, and against the amendment that would have removed the retroactive provision. The law, later known as the Salary Grab Act, provoked outrage across the country. Randall defended the Act, saying that an increased salary would "put members of Congress beyond temptation" and reduce fraud. Seeing the unpopularity of the Salary Grab, the incoming 43rd Congress

The 43rd United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1873, ...

repealed it almost immediately, with Randall voting for repeal.

Rise to prominence

Democrats remained in the minority when the 43rd Congress convened in 1873. Randall continued his opposition to measures proposed by Republicans, especially those intended to increase the power of the federal government. That term saw the introduction of a new civil rights bill with farther-reaching ambitions than any before it. Previous acts had seen the use of federal courts and troops to guarantee that black men and women could not be deprived of their civil rights by any state. Now Senator

Democrats remained in the minority when the 43rd Congress convened in 1873. Randall continued his opposition to measures proposed by Republicans, especially those intended to increase the power of the federal government. That term saw the introduction of a new civil rights bill with farther-reaching ambitions than any before it. Previous acts had seen the use of federal courts and troops to guarantee that black men and women could not be deprived of their civil rights by any state. Now Senator Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

of Massachusetts proposed a new bill, aimed at requiring equal rights in all public accommodations. When Sumner died in 1874, his bill had not passed, but others from the radical wing of the Republican Party, including Representative Benjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (November 5, 1818 – January 11, 1893) was an American major general of the Union Army, politician, lawyer, and businessman from Massachusetts. Born in New Hampshire and raised in Lowell, Massachusetts, Butler is ...

of Massachusetts, continued to work for its enactment.

Randall stood against this measure, as he had against nearly all Reconstruction laws. A lack of consensus delayed the bill from coming to a vote until the lame-duck session beginning in December 1874. By that time, disillusionment with the Grant administration and worsening economic conditions had translated into a Democratic victory in the mid-term elections. When the 44th Congress

The 44th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1875, ...

gathered in March 1875, the House would have a Democratic majority for the first time since the Civil War. In the meantime, the outgoing Republicans made one last effort to pass Sumner's civil rights bill; Randall and other Democrats immediately used parliamentary maneuvers to bring action to a stand-still, hoping to delay passage until the Congress ended. Randall led his caucus in filibustering the bill, at one point remaining on the floor for 72 hours. In the end, the Democrats peeled away some Republican votes, but not enough to defeat the bill, which passed by a vote of 162 to 100. Despite the defeat, Randall's filibuster increased his prominence in the eyes of his Democratic colleagues.

As Democrats took control of the House in 1875, Randall was considered among the candidates for Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hunger ...

. Many in the caucus hesitated, however, believing Randall to be too close to railroad interests and uncertain on the money question. His leadership in the Salary Grab may have harmed him, as well. Randall was also occupied by an intra-party battle with William A. Wallace for control of the Pennsylvania Democratic Party. Wallace, who had been elected to the United States Senate in 1874, was weakened by rumors that he had taken bribes from the railroads while a member of the State Senate. Randall wanted control of the Democratic machine statewide, and the Wallace faction's vulnerability on the bribery rumors provided the opportunity. In January 1875, he had friends in the state legislature begin an investigation into Wallace's clique, which ultimately turned state Democratic leaders against the senator. At the state Democratic convention in September 1875, Randall (with the help of his old ally, Squire McMullen) triumphed, putting his men in control of the state party.

In the meantime, the divisions in the state party proved ruinous for Randall's chances at the Speaker's chair. Instead, the Democrats decided on Michael C. Kerr

Michael Crawford Kerr (March 15, 1827 – August 19, 1876) of Indiana was an attorney, an American legislator, and the first Democratic speaker of the United States House of Representatives after the Civil War.

Early life

He was born at Titu ...

of Indiana, who was elected. Randall was instead named chairman of the Appropriations Committee. In that post, he focused on reducing the government's spending, and cut the budget by $30,000,000, despite opposition from the Republican Senate. Kerr's health was fragile, and he was often absent from sessions, but Randall refused to take his place as speaker on a temporary basis, preferring to concentrate on his appropriations work. Kerr and Randall began to work more closely together through 1876, but Kerr died in August of that year, leaving the Speakership vacant once again.

Speaker of the House

Hayes and Tilden

After Kerr's death, Randall was the consensus choice of the Democratic caucus, and was elected to the Speakership when Congress returned to Washington on December 2, 1876. He assumed the chair at a tumultuous time, as the presidential election had just concluded the previous month with no clear winner. The Democratic candidate, Samuel J. Tilden of New York, had 184 electoral votes, just shy of the 185 needed for victory.

After Kerr's death, Randall was the consensus choice of the Democratic caucus, and was elected to the Speakership when Congress returned to Washington on December 2, 1876. He assumed the chair at a tumultuous time, as the presidential election had just concluded the previous month with no clear winner. The Democratic candidate, Samuel J. Tilden of New York, had 184 electoral votes, just shy of the 185 needed for victory. Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

, the Republican, had 163; the remaining 22 votes were in doubt.

Randall spent early December in conference with Tilden while committees examined the votes from the disputed states. The counts of the disputed ballots were inconclusive, with each of the states in question producing two sets of returns: one signed by Democratic officials, the other by Republicans, each claiming victory for their man. By January 1877, with the question still unresolved, Congress and President Grant agreed to submit the matter to a bipartisan Electoral Commission, which would be authorized to determine the fate of the disputed electoral votes.

Randall supported the idea, believing it the best solution to an intractable problem. The bill passed, providing for a commission of five representatives, five senators, and five Supreme Court justices. To ensure partisan balance, there would be seven Democrats and seven Republicans; the fifteenth member was to be a Supreme Court justice chosen by the other four on the commission (themselves two Republicans and two Democrats). Justice David Davis, an independent respected by both parties, was expected to be their choice, but he upset the careful planning by accepting election to the Senate by the state of Illinois and refusing to serve on the commission. The remaining Supreme Court justices were all Republicans and, with the addition of Justice Joseph P. Bradley

Joseph Philo Bradley (March 14, 1813 – January 22, 1892) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1870 to 1892. He was also a member of the Electoral Commission that decided t ...

to the place intended for Davis, the commission had an 8–7 Republican majority. Randall nevertheless favored the compromise, even voting in favor of it in the roll call vote (the Speaker usually does not vote). The commission met and awarded all the disputed ballots to Hayes by an 8–7 party-line vote.

Democrats were outraged, and many demanded that they filibuster the final count in the House. Randall did not commit, but permitted the House to take recesses several times, delaying the decision. As the March4 inauguration day approached, leaders of both parties met at Wormley's Hotel in Washington to negotiate a compromise. Republicans promised that, in exchange for Democratic acquiescence in the commission's decision, Hayes would order federal troops to withdraw from the South and accept the election of Democratic governments in the remaining " unredeemed" states there. The Democratic leadership, including Randall, agreed and the filibuster ended.

Monetary disputes

Randall returned to Washington in March 1877 at the start of the

Randall returned to Washington in March 1877 at the start of the 45th Congress

The 45th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1877, ...

and was reelected Speaker. As the session began, many in the Democratic caucus were determined to repeal the Specie Payment Resumption Act of 1875. That Act, passed when Republicans last controlled the House, was intended to gradually withdraw all greenbacks from circulation, replacing them with dollars backed in specie (i.e., gold or silver). With the elimination of the silver dollar in 1873, this would effectively return the United States to the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from th ...

for the first time since before the Civil War. Randall, who had voted against the act in 1875, agreed to let the House vote on its repeal, which narrowly passed. The Senate, still controlled by Republicans, declined to act on the bill.

The attempt at repeal did not end the controversy over silver. Democratic Representative Richard P. Bland of Missouri proposed a bill that would require the United States to buy as much silver as miners could sell the government and strike it into coins, a system that would increase the money supply and aid debtors. In short, silver miners would sell the government metal worth fifty to seventy cents, and receive back a silver dollar. Randall allowed the bill to come to the floor for an up-or-down vote during a special session in November 1877: the result was its passage by a vote of 163 to 34 (with 94 members absent). The pro-silver idea cut across party lines, and William B. Allison

William Boyd Allison (March 2, 1829 – August 4, 1908) was an American politician. An early leader of the Iowa Republican Party, he represented northeastern Iowa in the United States House of Representatives before representing his state in th ...

, a Republican from Iowa, led the effort in the Senate. Allison offered an amendment in the Senate requiring the purchase of two to four million dollars per month of silver, but not allowing private deposit of silver at the mints. Thus, the seignorage

Seigniorage , also spelled seignorage or seigneurage (from the Old French ''seigneuriage'', "right of the lord (''seigneur'') to mint money"), is the difference between the value of money and the cost to produce and distribute it. The term can be ...

, or difference between the face value of the coin and the worth of the metal contained within it accrued to the government's credit, not private citizens. President Hayes vetoed the bill, but Congress overrode the veto, and the Bland–Allison Act became law.

Potter committee

As the 1880 presidential elections approached, many Democrats remained convinced Tilden had been robbed of the presidency in 1876. In the House, Tilden supporterClarkson Nott Potter

Clarkson Nott Potter (April 25, 1825 – January 23, 1882) was a New York attorney and politician who served four terms in the United States House of Representatives from 1869 to 1875, then again from 1877 to 1879.

Early life

Potter was born in ...

of New York sought an investigation into the 1876 election in Florida and Louisiana, hoping that evidence of Republican malfeasance would harm that party's candidate in 1880. The Democratic caucus, including Randall, unanimously endorsed the idea, and the committee convened in May 1878. Some in the caucus wished to investigate the entire election, but Randall and the more moderate members worked to limit the committee's reach to the two disputed states.

Randall left no doubt about his sympathies when he assigned members to the committee, stacking it with Hayes's enemies from both parties. The committee's investigation had the opposite of the Democrats' intended effect, uncovering telegrams from Tilden's nephew, William Tilden Pelton, offering bribes to Southern Republicans in the disputed states to help Tilden claim their votes. The Pelton telegrams were in code, which the committee was able to decode; Republicans had also sent ciphered dispatches, but the committee was unable to decode them. The ensuing excitement fizzled out by June 1878 as the Congress went into recess.

Reelected Speaker

As the46th Congress

The 46th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1879, ...

convened in 1879, the Democratic caucus was reduced, but they still held a plurality of seats. The new House contained 152 Democrats, 139 Republicans, and 20 independents, most of whom were affiliated with the Greenback Party

The Greenback Party (known successively as the Independent Party, the National Independent Party and the Greenback Labor Party) was an American political party with an anti-monopoly ideology which was active between 1874 and 1889. The party ran ...

. Many of Randall's fellow Democrats differed with him over protectionism and his lack of support for Southern railroad subsidies, and considered choosing Joseph Clay Stiles Blackburn

Joseph Clay Stiles Blackburn (October 1, 1838September 12, 1918) was a Democratic Representative and Senator from Kentucky. Blackburn, a skilled and spirited orator, was also a prominent trial lawyer known for his skill at swaying juries.

Biog ...

of Kentucky as their nominee for Speaker, instead. Several other Southerners' names were floated, too, as anti-Randall Democrats tried to coalesce around a single candidate; in the end, none could be found and the caucus chose Randall as their nominee with 107 votes out of 152. With some Democrats not yet present, however, the Democrats began to fear that the Republicans and Greenbackers would strike a deal to combine their votes to elect James A. Garfield of Ohio as Speaker. When the time for the vote came, however, Garfield refused to make any compromises with the third-party men, and Randall and the Democrats were able to organize the House once more.

Civil rights and the army

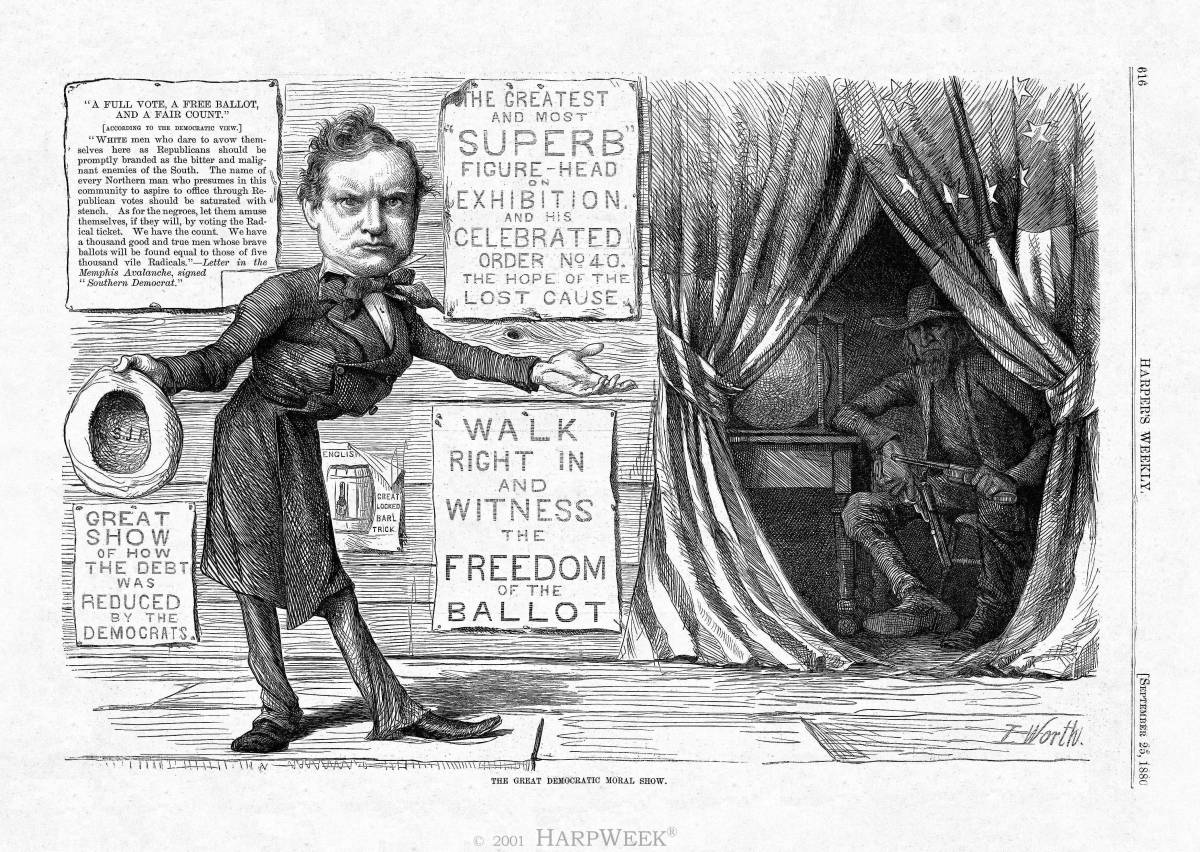

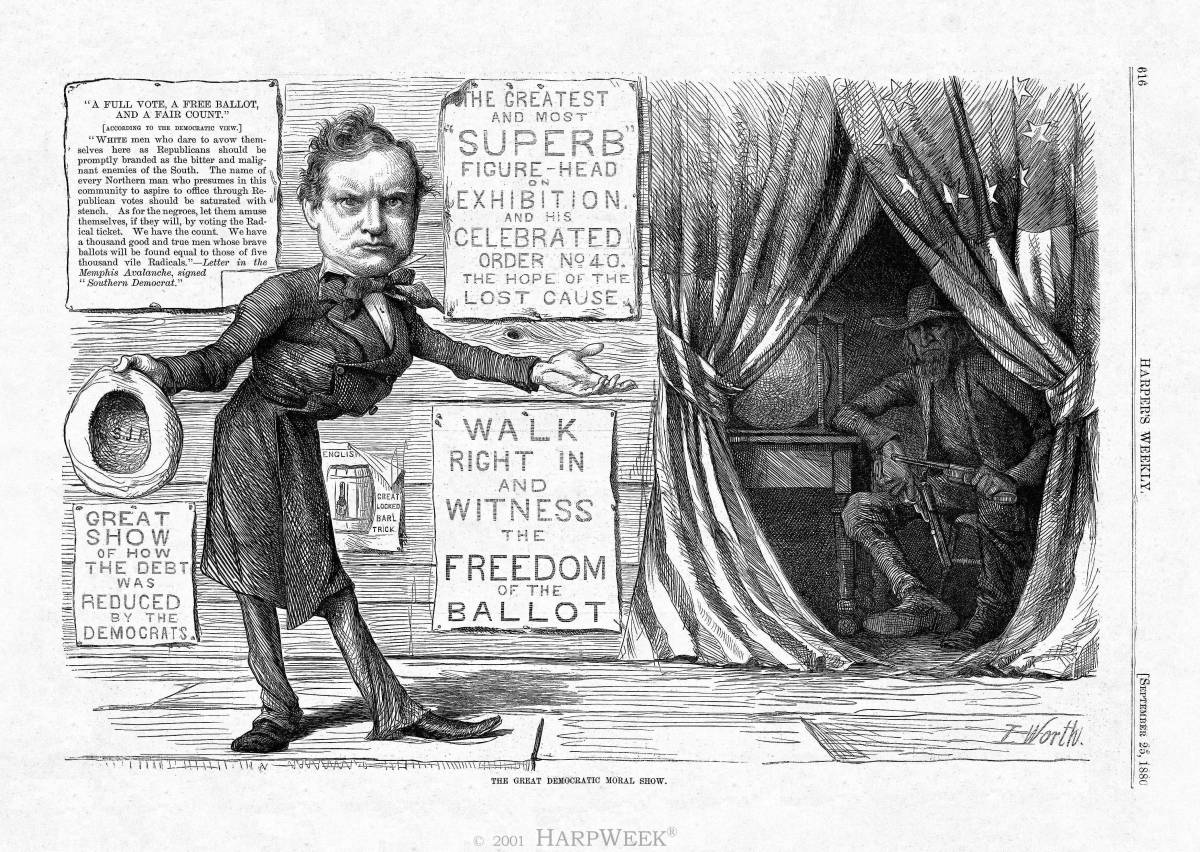

Randall's determination to cut spending, combined with Southern Democrats' desire to reduce federal power in their home states, led the House to pass an army appropriation bill with a rider that repealed the

Randall's determination to cut spending, combined with Southern Democrats' desire to reduce federal power in their home states, led the House to pass an army appropriation bill with a rider that repealed the Enforcement Acts

The Enforcement Acts were three bills that were passed by the United States Congress between 1870 and 1871. They were criminal codes that protected African Americans’ right to vote, to hold office, to serve on juries, and receive equal protect ...

, which had been used to suppress the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

. The Enforcement Acts, passed during Reconstruction over Democratic opposition, made it a crime to prevent someone from voting because of his race. Hayes was determined to preserve the law protecting black voters, and he vetoed the appropriation. The Democrats did not have enough votes to override the veto, but they passed a new bill with the same rider. Hayes vetoed this as well, and the process was repeated three times more. Finally, Hayes signed an appropriation without the rider, but Congress refused to pass another bill to fund federal marshals, who were vital to the enforcement of the Enforcement Acts. The election laws remained in effect, but the funds to enforce them were curtailed. Randall's role in the process was limited, but the Democrats' failure to force Hayes's acquiescence weakened his appeal as a potential presidential candidate in 1880.

1880 presidential election

As the 1880 elections approached, Randall had two goals: to increase his control of the Pennsylvania Democratic Party, and to nominate Tilden for president. His efforts at the former in 1875 had been successful, but Senator William Wallace's faction was again growing powerful. If he wanted to hold the Speakership, as well as to wield influence in the next presidential canvass, Randall believed he must have a united state party behind him. To that end, Randall spent much of his time outside of Congress travelling around his home state to line up support at the state convention in 1880. Some of his allies' enthusiasm backfired against him, however, after McMullen and some supporters broke up an anti-Randall meeting in Philadelphia's 5th ward with such violence that one man was left dead. When the state convention gathered in April 1880, Randall was confident of victory, but soon found that the Wallace faction outnumbered his. Wallace's majority scrambled the party's organization in Philadelphia and, although some Randall supporters received seats, the majority owed allegiance to the senator. Despite the defeat, Randall pressed on for Tilden, both in Pennsylvania and elsewhere. As rumors circulated that Tilden's health would keep him from running again, Randall remained a loyal Tilden man up to thenational convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year Nation ...

that June. After the first ballot, the New York delegation released a letter from Tilden in which he withdrew from consideration. Randall hoped for the ex-Tilden delegates to rally to him. Many did so, and Randall surged to second place on the second ballot, but the momentum had shifted to another candidate, Major General Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (February 14, 1824 – February 9, 1886) was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service ...

. Nearly all the delegates shifted to Hancock, and he was nominated.

Randall believed he had been betrayed by many he had thought would support him, but carried on regardless in support of his party's nominee. Hancock (who remained on active duty) and the Republican nominee, James A. Garfield, did not campaign directly, in keeping with the customs of that time, but campaigns were conducted by other party members, including Randall. Speaking in Pennsylvania and around the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

, Randall did his best to rally the people to Hancock against Garfield, but without success. Garfield was elected with 214 electoral votes—including those of Pennsylvania. Worse still for Randall, Garfield's victory had swept the Republicans back into a majority in the House, meaning Randall's time as Speaker was at an end.

Later House service

Tariffs

When Randall returned to Washington in 1881 to begin his term in the47th Congress

The 47th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1881, ...

, the legislature was controlled by Republicans. After Garfield's assassination later that year, Vice President Chester A. Arthur assumed the presidency. Arthur, like most Republicans, favored high tariffs, but he sought to simplify the tariff structure and to reduce excise taxes. Randall, who had returned to his seat on the Appropriations Committee, favored the president's plan, and was among the few Democrats in the House to support it. The bill that emerged from the Ways and Means Committee, dominated by protectionists, provided for only a 10 percent reduction. After conference with the Senate, the resulting bill had an even smaller effect, reducing tariffs by an average of 1.47 percent. It passed both houses narrowly on March 3, 1883, the last full day of the 47th Congress; Arthur signed the measure into law. Toward the end, Randall took less part in the debate, feeling the tension between his supporters in the House, who wanted more reductions, and his constituents at home, who wanted less.

The Democrats recaptured the House after the 1882 elections, but the incoming majority in the 48th Congress was divided on tariffs, with Randall's protectionist faction in the minority. The new Democratic caucus was more Southern and Western than in previous Congresses, and contained many new members who were unfamiliar with Randall. This led many to propose selecting a Speaker more in line with their own views, rather than returning Randall to the office. Randall's attempt to canvass the incoming representatives was further hampered by an attack of the gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intens ...

. In the end, John G. Carlisle

John Griffin Carlisle (September 5, 1834July 31, 1910) was an American politician from the commonwealth of Kentucky and was a member of the Democratic Party. He was elected to the United States House of Representatives seven times, first in ...

of Kentucky, an advocate of tariff reform, bested Randall in a poll of the Democratic caucus by a vote of 104 to 53.

Carlisle selected William Ralls Morrison

William Ralls Morrison (September 14, 1824 – September 29, 1909) was a U.S. Representative from Illinois.

Early life and career

Born on a farm at Prairie du Long, near the present town of Waterloo, Illinois, Morrison attended the common sc ...

, another tariff reformer, to lead the Ways and Means committee, but allowed Randall to take charge of Appropriations. Morrison's committee produced a bill proposing tariff reductions of 20%; Randall opposed the idea from the start, as did the Republicans. Another bout of illness kept Randall away from Congress at a crucial time in April 1884, and the tariff bill passed a procedural hurdle by just two votes. Two days later, Randall's Appropriations committee reported several funding bills with his support. Many Democrats who had voted for Morrison's tariff were thereby reminded that Randall had the power to defeat spending that was important to them; when the final vote came, enough switched sides to join with Republicans in defeating the reform 156 to 151.

Presidential election of 1884

As in 1880, the contest for the Democratic nomination for president in 1884 began under the shadow of Tilden. Declining health forced Tilden's withdrawal by June 1884, and Randall felt free to pursue his own chance at the presidency. He gathered some of the Pennsylvania delegates to his cause, but by the time the convention assembled in July, most of the former Tilden adherents had gathered around New York governorGrover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

. Early in the convention, Randall met with Daniel Manning

Daniel Manning (May 16, 1831 – December 24, 1887) was an American journalist, banker, and politician. A Democrat, he was most notable for his service as the 37th United States Secretary of the Treasury from 1885 to 1887 under President Gr ...

, Cleveland's campaign manager, and soon thereafter Randall's delegates were instructed to cast their votes for Cleveland. As his biographer, House, wrote, the "actual bargain struck between Randall and Manning is not known, but... events would seem to show that Randall was promised control of federal patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

in Pennsylvania."

Cleveland's campaign made extensive use of Randall, as he made speeches for Cleveland in New England, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Virginia, New York, and Connecticut, mainly in places where potential voters needed to be reassured that the Democrats did not want to lower the tariff so much that they would lose their jobs. In a close election, Cleveland was elected over his Republican opponent, James G. Blaine. Randall also took two tours of the South in 1884 after the election. Although, he claimed the trips to be of a personal nature, they generated speculation that Randall was gathering support for another run at the Speakership in 1885.

Resisting tariff reform

As the 49th Congress gathered in 1885, Cleveland's position on the tariff was still largely unknown. Randall declined to challenge Carlisle for Speaker, busying himself instead with the federal patronage in Pennsylvania and continued leadership of the Appropriations committee. In February 1886, Morrison, still the chairman of Ways and Means, proposed a bill to decrease the surplus by buying and cancelling $10 million worth of federal bonds each month. Cleveland opposed the plan, and Randall joined 13 Democrats and most Republicans in defeating it. Later that year, however, Cleveland supported Morrison's attempt to reduce the tariff. Again, Republicans and Randall's protectionist bloc combined to sink the measure. In the lame-duck session of 1887, Randall attempted a compromise tariff that would eliminateduties

A duty (from "due" meaning "that which is owing"; fro, deu, did, past participle of ''devoir''; la, debere, debitum, whence "debt") is a commitment or expectation to perform some action in general or if certain circumstances arise. A duty may ...

on some raw materials while also dispensing with excises on tobacco and some liquors. The bill attracted some support from Southern Democrats and Randall's protectionists, but Republicans and the rest of the Democratic caucus rejected it.

Declining influence

The tariff fight continued into the

The tariff fight continued into the 50th Congress

The 50th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1887, ...

, which opened in 1887, in which Democrats retained control of the House, with a reduced majority. By that time, Cleveland had openly sided with the tariff reformers and backed the proposals introduced in 1888 by Representative Roger Q. Mills

Roger Quarles Mills (March 30, 1832September 2, 1911) was an American lawyer and politician. During the American Civil War, he served as an officer in the Confederate States Army. Later, he served in the US Congress, first as a representative ...

of Texas. Mills had replaced Morrison at Ways and Means after the latter's defeat for reelection, and was as much in favor of tariff reform as the Illinoisan had been. Mills's bill would make small cuts to tariffs on raw materials, but relatively deeper cuts to those on manufactured goods; Randall, representing a manufacturing district, opposed it immediately. Randall was again ill and absent from the House when the Mills tariff passed by a 162 to 149 vote. The Senate, now Republican-controlled, refused to consider the bill, and it died with the 50th Congress in 1889.

Mills's and Cleveland's defeat on the tariff bill could be considered a victory for Randall, but the vote showed how isolated the former Speaker's protectionist ideas now made him in his party: only four Democrats voted against the tariff reductions. The state party likewise turned against Randall and toward free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

, adopting a pro-tariff revision platform at the 1888 state Democratic convention. At the same time, Randall seemingly reversed his long-standing commitment to fiscal economy by voting with the Republicans to override Cleveland's veto of the Dependent and Disability Pension Act

The Dependent and Disability Pension Act was passed by the United States Congress (26 Stat. 182) and signed into law by President Benjamin Harrison on June 27, 1890. The act provided pensions for all veterans who had served at least ninety days in ...

. The Act would have given a pension to every Union veteran (or their widows) who claimed he could no longer perform physical labor, regardless of whether his disability was war-related. Cleveland's veto was in line with his record of small-government cost-cutting, with which Randall would normally have sympathized. Randall, perhaps in an effort to gain favor with veterans in his district, joined the Republicans in an unsuccessful attempt to override Cleveland's veto. Another possibility proposed by biographer House is that Randall saw the federal budget surplus as reason to cut tariffs; by increasing federal spending, he hoped to decrease the surplus and maintain the need for high tariffs. Whatever the reason, the attempt failed and left Randall further alienated from his fellow Democrats.

Death

Randall's positions on tariffs and pensions had made him, according to ''

Randall's positions on tariffs and pensions had made him, according to ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', "a practical Republican" by 1888. Voting with the opposing party so frequently was an effective tactic, as he faced only token Republican opposition for reelection that year. Randall's health continued to decline. When the new congress began in 1889, he received special permission to be sworn into office from his bed, where he was confined. The new Speaker, Republican Thomas Brackett Reed of Maine, appointed Randall to the Rules and Appropriations committees, but he had no impact during that term.

On April 13, 1890, Randall died of colon cancer

Colorectal cancer (CRC), also known as bowel cancer, colon cancer, or rectal cancer, is the development of cancer from the colon or rectum (parts of the large intestine). Signs and symptoms may include blood in the stool, a change in bowe ...

in his Washington home. He had recently joined the First Presbyterian Church in the capital, and his funeral was held there. He was buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia. Elected every two years from 1862 to 1888, Randall was the only prominent Democrat continuously on the national scene between those years. In an obituary, the Bulletin of the American Iron and Steel Association described the congressman who had consistently protected their industry: "Not a great scholar, nor a great orator, nor a great writer, Samuel J. Randall was nevertheless a man of sterling common sense, quick perceptions, great courage, broad views and extraordinary capacity for work." The only scholarly works on his life are a master's thesis by Sidney I. Pomerantz, written in 1932, and a doctoral dissertation by Albert V. House, from 1934; both are unpublished. His papers were collected by the University of Pennsylvania library in the 1950s and he has been the subject of several journal articles (many by House), but awaits a full scholarly biography.

See also

List of United States Congress members who died in office (1790–1899)

The following is a list of United States senators and representatives who died of natural or accidental causes, or who killed themselves, while serving their terms between 1790 and 1899. For a list of members of Congress who were killed while in ...

Notes

References

Sources

Books

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *Articles

* * * * * * * * *Dissertation

*Newspapers

* *Further reading

* Detailed election results at electoral history of Samuel J. Randall * ThSamuel J. Randall Papers

including correspondence, congressional papers and other printed materials, are available for research use at the

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania is a long-established research facility, based in Philadelphia. It is a repository for millions of historic items ranging across rare books, scholarly monographs, family chronicles, maps, press reports and v ...

.

External links

New York Tribune (April 14, 1890Obituary for Samuel J Randall

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:Randall, Samuel J. 1828 births 1890 deaths 19th-century American politicians American Presbyterians Burials at Laurel Hill Cemetery (Philadelphia) Candidates in the 1880 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1884 United States presidential election Deans of the United States House of Representatives Deaths from cancer in Washington, D.C. Deaths from colorectal cancer Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania Democratic Party Pennsylvania state senators People of Pennsylvania in the American Civil War Philadelphia City Council members Politicians from Philadelphia Speakers of the United States House of Representatives