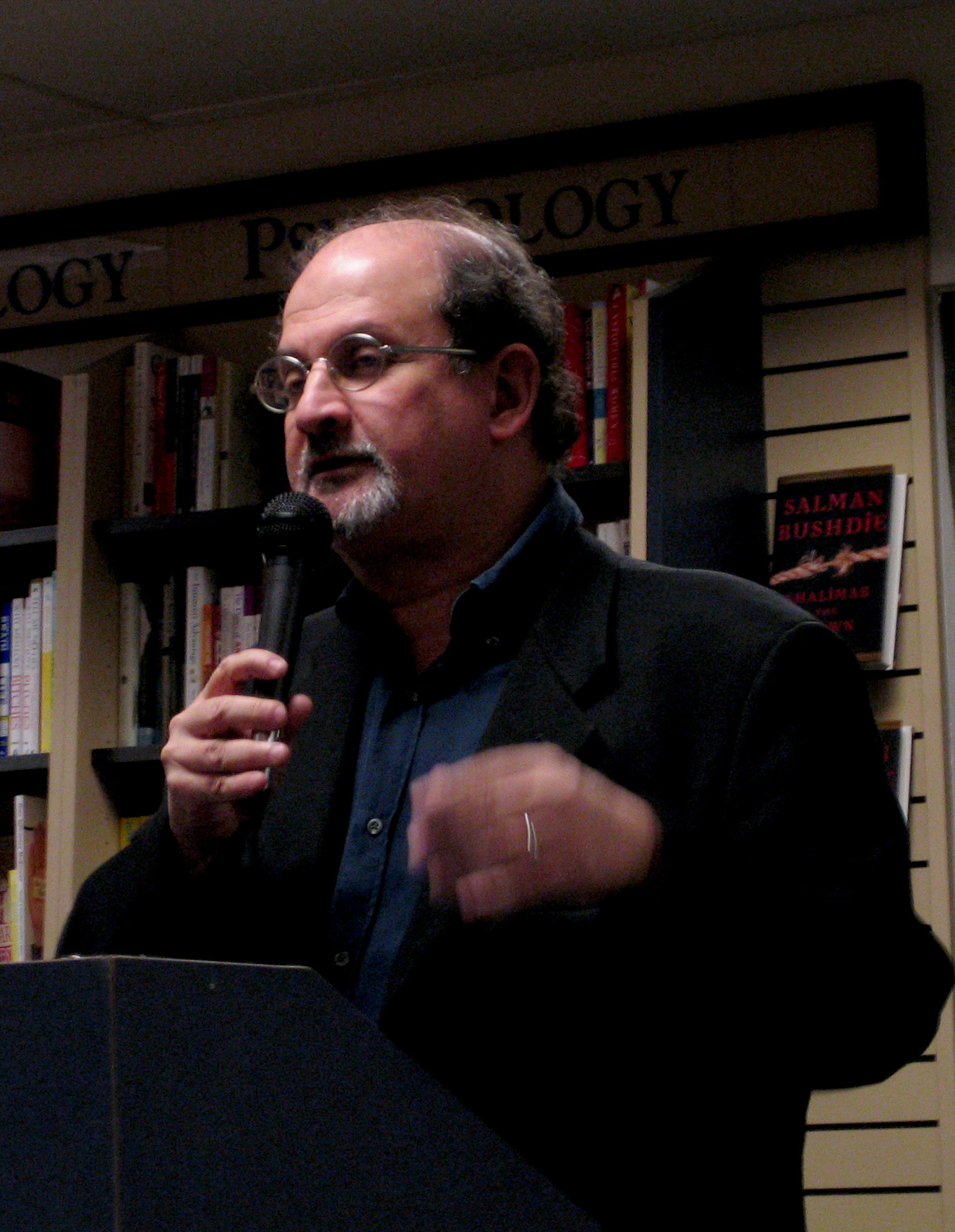

Salman Rushdie on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Ahmed Salman Rushdie (; born 19 June 1947) is an Indian-born British-American novelist. His work often combines magic realism with historical fiction and primarily deals with connections, disruptions, and migrations between

. Retrieved 20 January 2008 He is the son of Anis Ahmed Rushdie, a

Eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

and Western civilization

Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions">human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Cle ...

s, typically set on the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

.

Rushdie's second novel, '' Midnight's Children'' (1981), won the Booker Prize in 1981 and was deemed to be "the best novel of all winners" on two occasions, marking the 25th

25 (twenty-five) is the natural number following 24 and preceding 26.

In mathematics

It is a square number, being 52 = 5 × 5. It is one of two two-digit numbers whose square and higher powers of the number also ends in the same last t ...

and the 40th anniversary of the prize.

After his fourth novel, ''The Satanic Verses

''The Satanic Verses'' is the fourth novel of British-Indian writer Salman Rushdie. First published in September 1988, the book was inspired by the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. As with his previous books, Rushdie used magical realism ...

'' (1988), Rushdie became the subject of several assassination attempts and death threats, including a '' fatwa'' calling for his death issued by Ruhollah Khomeini, the supreme leader of Iran

The Supreme Leader of Iran ( fa, رهبر ایران, rahbar-e irān) is the head of state of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The Supreme Leader directs the executive system and judicial system of the Islamic theocratic government and is the co ...

. Numerous killings and bombings have been carried out by extremists who cite the book as motivation, sparking a debate about censorship and religiously motivated violence. On 12 August 2022, a man stabbed Rushdie after rushing onto the stage where the novelist was scheduled to deliver a lecture at an event in Chautauqua, New York

Chautauqua ( ) is a town and lake resort community in Chautauqua County, New York, United States. The population was 4,017 at the 2020 census. The town is named after Chautauqua Lake. It is the home of the Chautauqua Institution and the birthplace ...

.

In 1983, Rushdie was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. He was appointed a of France in 1999. Rushdie was knighted in 2007 for his services to literature. In 2008, ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

'' ranked him 13th on its list of the 50 greatest British writer

British literature is literature from the United Kingdom, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the Isle of Man, and the Channel Islands. This article covers British literature in the English language. Anglo-Saxon (Old English) l ...

s since 1945. Since 2000, Rushdie has lived in the United States. He was named Distinguished Writer in Residence at the Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute of New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private research university in New York City. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded by a group of New Yorkers led by then- Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.

In 1832, th ...

in 2015. Earlier, he taught at Emory University

Emory University is a private research university in Atlanta, Georgia. Founded in 1836 as "Emory College" by the Methodist Episcopal Church and named in honor of Methodist bishop John Emory, Emory is the second-oldest private institution of ...

. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters

The American Academy of Arts and Letters is a 300-member honor society whose goal is to "foster, assist, and sustain excellence" in American literature, music, and art. Its fixed number membership is elected for lifetime appointments. Its headqu ...

. In 2012, he published '' Joseph Anton: A Memoir'', an account of his life in the wake of the events following ''The Satanic Verses''.

Biography

Early life and family background

Ahmed Salman Rushdie was born inBombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second-m ...

on 19 June 1947 during the British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was him ...

, into an Indian Kashmiri Muslim

Kashmiri Muslims are ethnic Kashmiris who practice Islam and are native to the Kashmir Valley in Indian-administered Kashmir. Quote: "Jammu and Kashmir: Territory in northwestern India, subject to a dispute between India and Pakistan. It has b ...

family.''Literary Encyclopedia'': "Salman Rushdie". Retrieved 20 January 2008 He is the son of Anis Ahmed Rushdie, a

Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

-educated lawyer-turned-businessman, and Negin Bhatt, a teacher. Rushdie's father was dismissed from the Indian Civil Services

The Civil Services refer to the career government civil servants who are the permanent executive branch of the Republic of India. Elected cabinet ministers determine policy, and civil servants carry it out.

Central Civil Servants are employee ...

(ICS) after it emerged that the birth certificate submitted by him had changes to make him appear younger than he was. Rushdie has three sisters. He wrote in his 2012 memoir that his father adopted the name Rushdie in honour of Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psy ...

(Ibn Rushd).

Rushdie grew up in Bombay and was educated at the Cathedral and John Connon School

The Cathedral & John Connon School is a co-educational private school founded in 1860 and located in Fort, Mumbai, Maharashtra.Fort (Mumbai precinct), Fort, South Bombay, before moving to England to attend Rugby School in

Salman Rushdie's Midnight Child

. South Asian Diaspora. 25 July 2012. Collaborating with musician

Following the novel '' Fury'', set mainly in New York and avoiding the previous sprawling narrative style that spans generations, periods and places, Rushdie's 2005 novel '' Shalimar the Clown'', a story about love and betrayal set in Kashmir and Los Angeles, was hailed as a return to form by a number of critics.

In his 2002 non-fiction collection ''Step Across This Line'', he professes his admiration for the Italian writer

Following the novel '' Fury'', set mainly in New York and avoiding the previous sprawling narrative style that spans generations, periods and places, Rushdie's 2005 novel '' Shalimar the Clown'', a story about love and betrayal set in Kashmir and Los Angeles, was hailed as a return to form by a number of critics.

In his 2002 non-fiction collection ''Step Across This Line'', he professes his admiration for the Italian writer

Rushdie was the President of

Rushdie was the President of

Though he enjoys writing, Rushdie says he would have become an actor if his writing career had not been successful. From early childhood, he dreamed of appearing in Hollywood movies (which he later realised in his frequent cameo appearances).

Rushdie includes fictional television and movie characters in some of his writings. He had a

Though he enjoys writing, Rushdie says he would have become an actor if his writing career had not been successful. From early childhood, he dreamed of appearing in Hollywood movies (which he later realised in his frequent cameo appearances).

Rushdie includes fictional television and movie characters in some of his writings. He had a

Rushdie supported the 1999 NATO bombing of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, leading leftist historian

Rushdie supported the 1999 NATO bombing of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, leading leftist historian

Salman Rushdie

at ''

Salman Rushdie

at ''

Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

Emory University

Salman Rushdie papers, 1947–2012

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rushdie, Salman 1947 births Living people Writers from Mumbai Screenwriters from Mumbai Male actors from Mumbai Novelists from Maharashtra Film producers from Mumbai American critics of Islam American people of Indian descent American people of Kashmiri descent Atheism in the United Kingdom British Asian writers British atheism activists British critics of Islam British expatriates in the United States British former Muslims British people of Indian descent British people of Kashmiri descent Critics of Islamism Critics of religions English atheists English expatriates in the United States English feminists English humanists English memoirists English people of Indian descent English people of Kashmiri descent English social commentators Fatwas Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature Former Muslim critics of Islam Former Muslims turned agnostics or atheists Free speech activists Indian copywriters Indian emigrants to England Indian emigrants to the United Kingdom Indian expatriates in Pakistan Indian former Muslims Indian people of Kashmiri descent Indian television writers Kashmiri Muslims Kashmiri people Knights Bachelor Magic realism writers Male feminists Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom People educated at Rugby School People with acquired American citizenship Postcolonial literature Postmodern writers Stabbing survivors Victims of bomb threats Iran–United Kingdom relations Cathedral and John Connon School alumni Alumni of King's College, Cambridge Emory University faculty Booker Prize winners British Book Award winners Best Screenplay Genie and Canadian Screen Award winners Iran's Book of the Year Awards recipients James Tait Black Memorial Prize recipients 20th-century atheists 20th-century English novelists 20th-century Indian essayists 20th-century Indian novelists 21st-century American novelists 21st-century atheists 21st-century English novelists 21st-century Indian dramatists and playwrights 21st-century Indian essayists 21st-century Indian male actors 21st-century Indian novelists

Rugby, Warwickshire

Rugby is a market town in eastern Warwickshire, England, close to the River Avon. In the 2021 census its population was 78,125, making it the second-largest town in Warwickshire. It is the main settlement within the larger Borough of Rugby whi ...

, and then King's College, Cambridge

King's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Formally The King's College of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas in Cambridge, the college lies beside the River Cam and faces out onto King's Parade in the centre of the cit ...

, from which he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in history.

Personal life

Rushdie has married and divorced four times, and has had at least one other significant relationship. He was first married to Clarissa Luard, literature officer of theArts Council of England

The arts are a very wide range of human practices of creative expression, storytelling and cultural participation. They encompass multiple diverse and plural modes of thinking, doing and being, in an extremely broad range of media. Both h ...

, from 1976 to 1987. The couple had a son born in 1979, who is married to the London-based jazz singer Natalie Rushdie. He left Clarissa Luard in the mid-1980s for the Australian writer Robyn Davidson

Robyn Davidson (born 6 September 1950) is an Australian writer best known for her 1980 book ''Tracks'', about her 2,700 km (1,700 miles) trek across the deserts of Western Australia using camels. Her career of travelling and writing about ...

, to whom he was introduced by their common friend Bruce Chatwin

Charles Bruce Chatwin (13 May 194018 January 1989) was an English travel writer, novelist and journalist. His first book, ''In Patagonia'' (1977), established Chatwin as a travel writer, although he considered himself instead a storyteller, ...

. Rushdie and Davidson never married, and they had split up by the time his divorce from Clarissa came through in 1987. Rushdie's second wife was the American novelist Marianne Wiggins

Marianne Wiggins (born 1947) is an American author. According to ''The Cambridge Guide to Women's Writing in English'', Wiggins writes with "a bold intelligence and an ear for hidden comedy." She has won a Whiting Award, an National Endowment fo ...

; they were married in 1988 and divorced in 1993. His third wife, from 1997 to 2004, was British editor and author Elizabeth West; they have a son, born in 1997. In 2004, very shortly after his third divorce, Rushdie married Padma Lakshmi, an Indian-born actress, model, and host of the American reality-television show '' Top Chef''. Rushdie stated that Lakshmi had asked for a divorce in January 2007, and later that year, in July, the couple filed it.

In 1999, Rushdie had an operation to correct ptosis, a problem with the levator palpebrae superioris muscle that causes drooping of the upper eyelid. According to Rushdie, it made it increasingly difficult for him to open his eyes. "If I hadn't had an operation, in a couple of years from now I wouldn't have been able to open my eyes at all", he said.

Since 2000, Rushdie has lived in the United States, mostly near Union Square

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

in Lower Manhattan, New York City. He is a fan of the English football club Tottenham Hotspur.

Career

Copywriter

Rushdie worked as a copywriter for the advertising agencyOgilvy & Mather

Ogilvy is a New York City-based British advertising, marketing, and public relations agency. It was founded in 1850 by Edmund Mather as a London-based advertising agency, agency. In 1964, the firm became known as Ogilvy & Mather after merging wit ...

, where he came up with "irresistibubble" for Aero and "Naughty but Nice" for cream cakes, and for the agency Ayer Barker (until 1982), for whom he wrote the line "That'll do nicely" for American Express.Ravikrishnan, AshutoshSalman Rushdie's Midnight Child

. South Asian Diaspora. 25 July 2012. Collaborating with musician

Ronnie Bond

Ronnie Bond (born Ronald James Bullis; 4 May 1940 – 13 November 1992) was an English drummer, best known as the original drummer with the 1960s rock band The Troggs.

Born in Andover, Hampshire, Bond was the original drummer with The Troggs, ...

, Rushdie wrote the words for an advertising record on behalf of the now defunct Burnley Building Society

The Burnley Building Society, incorporated in Burnley in 1850, was, by 1911, not only "by far the largest in the County of Lancashire... but the sixth in magnitude in the kingdom". Their motto was By Service We Progress.

History

The Burnley Buil ...

that was recorded at Good Earth Studios

Dean Street Studios is a commercial recording studio located at 59 Dean Street, Soho, London, England.

History

The premises are first known to have been used as a film studio in 1950s, which then became Zodiac Studios.

The studio was bought by p ...

, London. The song was called "The Best Dreams" and was sung by George Chandler. It was while at Ogilvy that Rushdie wrote ''Midnight's Children'', before becoming a full-time writer.

Literary works

Rushdie's first novel, '' Grimus'' (1975), a part-science fiction tale, was generally ignored by the public and literary critics. His next novel, '' Midnight's Children'' (1981), catapulted him to literary notability. This work won the 1981 Booker Prize and, in 1993 and 2008, was awarded the Best of the Bookers as the best novel to have received the prize during its first 25 and 40 years. ''Midnight's Children'' follows the life of a child, born at the stroke of midnight as India gained its independence, who is endowed with special powers and a connection to other children born at the dawn of a new and tumultuous age in the history of the Indian sub-continent and the birth of the modern nation of India. The character of Saleem Sinai has been compared to Rushdie. However, the author refuted the idea of having written any of his characters as autobiographical, stating, "People assume that because certain things in the character are drawn from your own experience, it just becomes you. In that sense, I've never felt that I've written an autobiographical character." After ''Midnight's Children'', Rushdie wrote '' Shame'' (1983), in which he depicts the political turmoil in Pakistan, basing his characters on Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and GeneralMuhammad Zia-ul-Haq

General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq HI, GCSJ, ร.ม.ภ, (Urdu: ; 12 August 1924 – 17 August 1988) was a Pakistani four-star general and politician who became the sixth President of Pakistan following a coup and declaration of martial law in ...

. ''Shame'' won France's '' Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger'' (Best Foreign Book) and was a close runner-up for the Booker Prize. Both these works of postcolonial literature are characterised by a style of magic realism and the immigrant outlook that Rushdie is very conscious of as a member of the Kashmiri diaspora.

Rushdie wrote a non-fiction book about Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the countr ...

in 1987 called ''The Jaguar Smile

''The Jaguar Smile'' is Salman Rushdie's first full-length non-fiction book, which he wrote in 1987 after visiting Nicaragua. The book is Subtitle (titling), subtitled ''A Nicaraguan Journey'' and relates his travel experiences, the people he met ...

''. This book has a political focus and is based on his first-hand experiences and research at the scene of Sandinista

The Sandinista National Liberation Front ( es, Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, FSLN) is a socialist political party in Nicaragua. Its members are called Sandinistas () in both English and Spanish. The party is named after Augusto C� ...

political experiments. He became interested in Nicaragua after he had been a neighbour of Madame Somoza, wife of the former Nicaraguan dictator, and his son Zafar was born around the time of the Nicaraguan revolution.

His most controversial work, ''The Satanic Verses

''The Satanic Verses'' is the fourth novel of British-Indian writer Salman Rushdie. First published in September 1988, the book was inspired by the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. As with his previous books, Rushdie used magical realism ...

'', was published in 1988 (see section below). It was followed by ''Haroun and the Sea of Stories

''Haroun and the Sea of Stories'' is a 1990 children's novel by Salman Rushdie. It was Rushdie's fifth major publication and followed ''The Satanic Verses''. It is a phantasmagorical story that begins in a city so sad and ruinous that it has fo ...

'' in 1990. Written in the shadow of a fatwa, it is about the dangers of story-telling and an allegorical defence of the power of stories over silence.

In addition to books, Rushdie has published many short stories, including those collected in '' East, West'' (1994). '' The Moor's Last Sigh'', a family epic ranging over some 100 years of India's history was published in 1995. ''The Ground Beneath Her Feet

''The Ground Beneath Her Feet'' is Salman Rushdie's sixth novel. Published in 1999, it is a variation on the Orpheus#Death of Eurydice, Orpheus/Eurydice myth, with rock music replacing Orpheus's lyre. The myth works as a red thread from which ...

'' (1999) is a remaking of the myth of Orpheus

Orpheus (; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet in ancient Greek religion. He was also a renowned poet and, according to the legend, travelled with J ...

that presents an alternative history

Alternate history (also alternative history, althist, AH) is a genre of speculative fiction of stories in which one or more historical events occur and are resolved differently than in real life. As conjecture based upon historical fact, alte ...

of modern rock music. The song of the same name by U2 is one of many song lyrics included in the book; hence Rushdie is credited as the lyricist.

Following the novel '' Fury'', set mainly in New York and avoiding the previous sprawling narrative style that spans generations, periods and places, Rushdie's 2005 novel '' Shalimar the Clown'', a story about love and betrayal set in Kashmir and Los Angeles, was hailed as a return to form by a number of critics.

In his 2002 non-fiction collection ''Step Across This Line'', he professes his admiration for the Italian writer

Following the novel '' Fury'', set mainly in New York and avoiding the previous sprawling narrative style that spans generations, periods and places, Rushdie's 2005 novel '' Shalimar the Clown'', a story about love and betrayal set in Kashmir and Los Angeles, was hailed as a return to form by a number of critics.

In his 2002 non-fiction collection ''Step Across This Line'', he professes his admiration for the Italian writer Italo Calvino

Italo Calvino (, also , ;. RAI (circa 1970), retrieved 25 October 2012. 15 October 1923 – 19 September 1985) was an Italian writer and journalist. His best known works include the '' Our Ancestors'' trilogy (1952–1959), the ''Cosmicomi ...

and the American writer Thomas Pynchon

Thomas Ruggles Pynchon Jr. ( , ; born May 8, 1937) is an American novelist noted for his dense and complex novels. His fiction and non-fiction writings encompass a vast array of subject matter, genres and themes, including history, music, scie ...

, among others. His early influences included Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo (; ; 24 August 1899 – 14 June 1986) was an Argentine short-story writer, essayist, poet and translator, as well as a key figure in Spanish-language and international literature. His best-known b ...

, Mikhail Bulgakov, Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (; 27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet and mathematician. His most notable works are '' Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (1865) and its sequ ...

, Günter Grass and James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important writers of ...

. Rushdie was a personal friend of Angela Carter

Angela Olive Pearce (formerly Carter, Stalker; 7 May 1940 – 16 February 1992), who published under the name Angela Carter, was an English novelist, short story writer, poet, and journalist, known for her feminist, magical realism, and picar ...

's and praised her highly in the foreword of her collection ''Burning your Boats''.

2008 saw the publication of '' The Enchantress of Florence'', one of Rushdie's most challenging works that focuses on the past. It tells the story of a European's visit to Akbar's court, and his revelation that he is a lost relative of the Mughal emperor. The novel was praised in a review in ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' as a "sumptuous mixture of history with fable".

His novel ''Luka and the Fire of Life

''Luka and the Fire of Life'' is a novel by Salman Rushdie. It was published by Jonathan Cape (UK) and Random House (US) in 2010. It is the sequel to ''Haroun and the Sea of Stories''. Rushdie has said "he turned to the world of video games for ...

'', a sequel to ''Haroun and the Sea of Stories'', was published in November 2010 to critical acclaim. Earlier that year, he announced that he was writing his memoirs, entitled '' Joseph Anton: A Memoir'', which was published in September 2012.

In 2012, Rushdie became one of the first major authors to embrace Booktrack

Booktrack is the creator of the e-reader technology that incorporates multimedia such as music, sound effects, and ambient sound. The company was founded and maintains offices in Auckland, New Zealand and is headquartered in San Francisco, Califor ...

(a company that synchronises ebooks with customised soundtracks), when he published his short story " In the South" on the platform.

2015 saw the publication of Rushdie's novel ''Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights

''Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights'' is a fantasy novel by British Indian author Salman Rushdie published by Jonathan Cape in 2015.

Plot

The novel is set in New York City in the near future. It deals with jinns, and recounts the st ...

'', a shift back to his old beloved style of magic realism. This novel is designed in the structure of a Chinese mystery box with different layers. Based on the central conflict of scholar Ibn Rushd

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology, ...

(from whom Rushdie's family name derives), Rushdie goes on to explore several themes of transnationalism and cosmopolitanism by depicting a war of the universe which a supernatural world of jinns also accompanies.

In 2017, '' The Golden House'', a satirical novel set in contemporary America, was published. 2019 saw the publication of Rushdie's fourteenth novel '' Quichotte'', inspired by Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 NS) was an Early Modern Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best kno ...

' classic novel ''Don Quixote

is a Spanish epic novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts, in 1605 and 1615, its full title is ''The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha'' or, in Spanish, (changing in Part 2 to ). A founding work of West ...

''.

In 2021 '' Languages of Truth'', a collection of essays written between 2003 and 2020 was published. Rushdie's fifteenth novel ''Victory City'', described as an epic tale of a woman who breathes a fantastical empire into existence, will be published in February 2023.

Critical reception

Rushdie has had a string of commercially successful and critically acclaimed novels. His works have been shortlisted for the Booker Prize five times, in 1981 for '' Midnight's Children'', 1983 for ''Shame'', 1988 for ''The Satanic Verses

''The Satanic Verses'' is the fourth novel of British-Indian writer Salman Rushdie. First published in September 1988, the book was inspired by the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. As with his previous books, Rushdie used magical realism ...

'', 1995 for '' The Moor's Last Sigh'', and in 2019 for ''Quichotte''. In 1981, he was awarded the prize. His 2005 novel '' Shalimar the Clown'' received the prestigious Hutch Crossword Book Award

A crossword is a word puzzle that usually takes the form of a square or a rectangular grid of white- and black-shaded squares. The goal is to fill the white squares with letters, forming words or phrases, by solving clues which lead to the answ ...

, and, in the UK, was a finalist for the Whitbread Book Awards. It was shortlisted for the 2007 International Dublin Literary Award

The International Dublin Literary Award ( ga, Duais Liteartha Idirnáisiúnta Bhaile Átha Chliath), established as the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award in 1996, is presented each year for a novel written or translated into English. ...

. Rushdie's works have spawned 30 book-length studies and over 700 articles on his writing. He is frequently mentioned a favourite to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Academic and other activities

Rushdie has mentored younger Indian (and ethnic-Indian) writers, influenced an entire generation of Indo-Anglian writers, and is an influential writer in postcolonial literature in general. He opposed the British government's introduction of the ''Racial and Religious Hatred Act'', something he writes about in his contribution to ''Free Expression Is No Offence'', a collection of essays by several writers, published by Penguin in November 2005. Rushdie was the President of

Rushdie was the President of PEN American Center

PEN America (formerly PEN American Center), founded in 1922 and headquartered in New York City, is a nonprofit organization that works to defend and celebrate free expression in the United States and worldwide through the advancement of liter ...

from 2004 to 2006 and founder of the PEN World Voices Festival. In 2007, he began a five-year term as Distinguished Writer in Residence at Emory University

Emory University is a private research university in Atlanta, Georgia. Founded in 1836 as "Emory College" by the Methodist Episcopal Church and named in honor of Methodist bishop John Emory, Emory is the second-oldest private institution of ...

in Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

, Georgia, where he has also deposited his archives. In May 2008, he was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

The American Academy of Arts and Letters is a 300-member honor society whose goal is to "foster, assist, and sustain excellence" in American literature, music, and art. Its fixed number membership is elected for lifetime appointments. Its headqu ...

. In 2014, he taught a seminar on British Literature and served as the 2015 keynote speaker In September 2015, he joined the New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private research university in New York City. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded by a group of New Yorkers led by then- Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.

In 1832, th ...

Journalism Faculty as a Distinguished Writer in Residence.

Rushdie is a member of the advisory board of The Lunchbox Fund, a non-profit organisation that provides daily meals to students of township schools in Soweto of South Africa. He is a member of the advisory board of the Secular Coalition for America, an advocacy group representing the interests of atheistic and humanistic Americans in Washington, D.C., and a patron of Humanists UK (formerly the British Humanist Association). He is a laureate of the International Academy of Humanism. In November 2010 he became a founding patron of Ralston College, a new liberal arts college that has adopted as its motto a Latin translation of a phrase ("free speech is life itself") from an address he gave at Columbia University in 1991 to mark the two-hundredth anniversary of the first amendment to the US Constitution.

Film and television

Though he enjoys writing, Rushdie says he would have become an actor if his writing career had not been successful. From early childhood, he dreamed of appearing in Hollywood movies (which he later realised in his frequent cameo appearances).

Rushdie includes fictional television and movie characters in some of his writings. He had a

Though he enjoys writing, Rushdie says he would have become an actor if his writing career had not been successful. From early childhood, he dreamed of appearing in Hollywood movies (which he later realised in his frequent cameo appearances).

Rushdie includes fictional television and movie characters in some of his writings. He had a cameo appearance

A cameo role, also called a cameo appearance and often shortened to just cameo (), is a brief appearance of a well-known person in a work of the performing arts. These roles are generally small, many of them non-speaking ones, and are commonly ei ...

in the film '' Bridget Jones's Diary'' based on the book of the same name, which is itself full of literary in-jokes. On 12 May 2006, Rushdie was a guest host on ''The Charlie Rose Show

''Charlie Rose'' (also known as ''The Charlie Rose Show'') is an American television interview and talk show, with Charlie Rose as executive producer, executive editor, and host. The show was syndicated on PBS from 1991 until 2017 and is owned ...

'', where he interviewed Indo-Canadian filmmaker Deepa Mehta, whose 2005 film, ''Water

Water (chemical formula ) is an Inorganic compound, inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living ...

'', faced violent protests. He appears in the role of Helen Hunt's obstetrician-gynecologist in the film adaptation (Hunt's directorial debut) of Elinor Lipman's novel '' Then She Found Me''. In September 2008, and again in March 2009, he appeared as a panellist on the HBO programme ''Real Time with Bill Maher

''Real Time with Bill Maher'' is an American television talk show that airs weekly on HBO, hosted by comedian and political satirist Bill Maher. Much like his previous series ''Politically Incorrect'' on Comedy Central and later on ABC, ''Real ...

''. Rushdie has said that he was approached for a cameo in '' Talladega Nights'': "They had this idea, just one shot in which three very, very unlikely people were seen as NASCAR

The National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing, LLC (NASCAR) is an American auto racing sanctioning and operating company that is best known for stock car racing. The privately owned company was founded by Bill France Sr. in 1948, and ...

drivers. And I think they approached Julian Schnabel

Julian Schnabel (born October 26, 1951) is an American painter and filmmaker. In the 1980s, he received international attention for his "plate paintings" — with broken ceramic plates set onto large-scale paintings. Since the 1990s, he has been ...

, Lou Reed, and me. We were all supposed to be wearing the uniforms and the helmet, walking in slow motion with the heat haze." In the end their schedules did not allow for it.

In 2009, Rushdie signed a petition in support of film director Roman Polanski

Raymond Roman Thierry Polański , group=lower-alpha, name=note_a ( né Liebling; 18 August 1933) is a French-Polish film director, producer, screenwriter, and actor. He is the recipient of numerous accolades, including an Academy Award, tw ...

, calling for his release after Polanski was arrested in Switzerland in relation to his 1977 charge for drugging and raping a 13-year-old girl.

Rushdie collaborated on the screenplay for the cinematic adaptation of his novel ''Midnight's Children'' with director Deepa Mehta. The film was also called '' Midnight's Children''. Seema Biswas, Shabana Azmi

Shabana Azmi (born 18 September 1950) is an Indian actress of Hindi film, television and theatre. One of India's most acclaimed actresses, Azmi is known for her portrayals of distinctive, often unconventional female characters across several ge ...

, Nandita Das, and Irrfan Khan

Irrfan Khan () (born Sahabzade Irfan Ali Khan; 7 January 196729 April 2020), also known simply as Irrfan, was an Indian actor who worked in Indian cinema as well as British and American films. Widely regarded as one of the finest actors in In ...

participated in the film. Production began in September 2010; the film was released in 2012.

Rushdie announced in June 2011 that he had written the first draft of a script for a new television series for the US cable network Showtime, a project on which he will also serve as an executive producer. The new series, to be called ''The Next People'', will be, according to Rushdie, "a sort of paranoid science-fiction series, people disappearing and being replaced by other people." The idea of a television series was suggested by his US agents, said Rushdie, who felt that television would allow him more creative control than feature film. ''The Next People'' is being made by the British film production company Working Title

A working title, which may be abbreviated and styled in trade publications after a putative title as (wt), also called a production title or a tentative title, is the temporary title of a product or project used during its development, usually ...

, the firm behind projects including ''Four Weddings and a Funeral

''Four Weddings and a Funeral'' is a 1994 British romantic comedy film directed by Mike Newell. It is the first of several films by screenwriter Richard Curtis to feature Hugh Grant, and follows the adventures of Charles (Grant) and his circle ...

'' and ''Shaun of the Dead

''Shaun of the Dead'' is a 2004 zombie comedy film directed by Edgar Wright and written by Wright and Simon Pegg. Pegg stars as Shaun, a downtrodden salesman in London who is caught in a zombie apocalypse with his friend Ed ( Nick Frost). The ...

''.

In 2017, Rushdie appeared as himself in episode 3 of season 9 of '' Curb Your Enthusiasm'', sharing scenes with Larry David

Lawrence Gene David (born July 2, 1947) is an American comedian, writer, actor, and television producer. He and Jerry Seinfeld created the television sitcom ''Seinfeld'', on which David was head writer and executive producer for the first seve ...

to offer advice on how Larry should deal with the ''fatwa'' that has been ordered against him.

''The Satanic Verses'' and the ''fatwā''

The publication of ''The Satanic Verses

''The Satanic Verses'' is the fourth novel of British-Indian writer Salman Rushdie. First published in September 1988, the book was inspired by the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. As with his previous books, Rushdie used magical realism ...

'' by Viking Penguin in September 1988 caused immediate controversy in the Islamic world because of what was seen by some to be an irreverent depiction of Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mo ...

. The title refers to a disputed Muslim tradition that is related in the book. According to this tradition, Muhammad ( Mahound in the book) added verses ('' Ayah'') to the Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , s ...

accepting three Arabian pagan goddesses who used to be worshipped in Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow ...

as divine beings. According to the legend, Muhammad later revoked the verses, saying the devil tempted him to utter these lines to appease the Meccans (hence the "Satanic" verses). However, the narrator reveals to the reader that these disputed verses were actually from the mouth of the Archangel Gabriel

In Abrahamic religions ( Judaism, Christianity and Islam), Gabriel (); Greek: grc, Γαβριήλ, translit=Gabriḗl, label=none; Latin: ''Gabriel''; Coptic: cop, Ⲅⲁⲃⲣⲓⲏⲗ, translit=Gabriêl, label=none; Amharic: am, ገብ ...

. The book was banned in many countries with large Muslim communities (13 in total: Iran, India, Bangladesh, Sudan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Kenya, Thailand, Tanzania, Indonesia, Singapore, Venezuela, and Pakistan).

In response to the protests, on 22 January 1989, Rushdie published a column in ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the ...

'' that called Muhammad "one of the great geniuses of world history," but noted that Islamic doctrine holds Muhammad to be human, and in no way perfect. He held that the novel is not "an anti-religious novel. It is, however, an attempt to write about migration, its stresses and transformations."

On 14 February 1989—Valentine's Day, and also the day of his close friend Bruce Chatwin

Charles Bruce Chatwin (13 May 194018 January 1989) was an English travel writer, novelist and journalist. His first book, ''In Patagonia'' (1977), established Chatwin as a travel writer, although he considered himself instead a storyteller, ...

's funeral—a ''fatwā

A fatwā ( ; ar, فتوى; plural ''fatāwā'' ) is a legal ruling on a point of Islamic law (''sharia'') given by a qualified '' Faqih'' (Islamic jurist) in response to a question posed by a private individual, judge or government. A jurist ...

'' ordering Rushdie's execution was proclaimed on Radio Tehran by Ayatollah Khomeini

Ruhollah Khomeini, Ayatollah Khomeini, Imam Khomeini ( , ; ; 17 May 1900 – 3 June 1989) was an Iranian political and religious leader who served as the first supreme leader of Iran from 1979 until his death in 1989. He was the founder of ...

, the Supreme leader of Iran

The Supreme Leader of Iran ( fa, رهبر ایران, rahbar-e irān) is the head of state of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The Supreme Leader directs the executive system and judicial system of the Islamic theocratic government and is the co ...

at the time, calling the book "blasphemous

Blasphemy is a speech crime and religious crime usually defined as an utterance that shows contempt, disrespects or insults a deity, an object considered sacred or something considered inviolable. Some religions regard blasphemy as a religio ...

against Islam". Chapter IV of the book depicts the character of an Imam in exile who returns to incite revolt from the people of his country with no regard for their safety. According to Khomeini's son, his father never read the book. A bounty was offered for Rushdie's death, and he was thus forced to live under police protection for several years. On 7 March 1989, the United Kingdom and Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

broke diplomatic relations over the Rushdie controversy.

When, on BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC that replaced the BBC Home Service in 1967. It broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes, including news, drama, comedy, science and history from the BBC' ...

, he was asked for a response to the threat, Rushdie said, "Frankly, I wish I had written a more critical book," and "I'm very sad that it should have happened. It's not true that this book is a blasphemy against Islam. I doubt very much that Khomeini or anyone else in Iran has read the book or more than selected extracts out of context." Later, he wrote that he was "proud, then and always", of that statement; while he did not feel his book was especially critical of Islam, "a religion whose leaders behaved in this way could probably use a little criticism."

The publication of the book and the ''fatwā'' sparked violence around the world, with bookstores firebombed. Muslim communities in several nations in the West held public rallies, burning copies of the book. Several people associated with translating or publishing the book were attacked, seriously injured, and even killed. Many more people died in riots in some countries. Despite the danger posed by the fatwā, Rushdie made a public appearance at London's Wembley Stadium

Wembley Stadium (branded as Wembley Stadium connected by EE for sponsorship reasons) is a football stadium in Wembley, London. It opened in 2007 on the site of the original Wembley Stadium, which was demolished from 2002 to 2003. The stadium ...

on 11 August 1993, during a concert by U2. In 2010, U2 bassist Adam Clayton

Adam Charles Clayton (born 13 March 1960) is an English-born Irish musician who is the bass guitarist of the rock band U2. He has resided in County Dublin, Ireland since his family moved to Malahide in 1965, when he was five years old. C ...

recalled that "lead vocalist Bono had been calling Salman Rushdie from the stage every night on the Zoo TV tour. When we played Wembley, Salman showed up in person and the stadium erupted. You ouldtell from rummerLarry Mullen, Jr.'s face that we weren't expecting it. Salman was a regular visitor after that. He had a backstage pass and he used it as often as possible. For a man who was supposed to be in hiding, it was remarkably easy to see him around the place."

On 24 September 1998, as a precondition to the restoration of diplomatic relations with the UK, the Iranian government, then headed by Mohammad Khatami, gave a public commitment that it would "neither support nor hinder assassination operations on Rushdie."

Hardliners in Iran have continued to reaffirm the death sentence. In early 2005, Khomeini's ''fatwā'' was reaffirmed by Iran's current dictator, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei

Sayyid Ali Hosseini Khamenei ( fa, سید علی حسینی خامنهای, ; born 19 April 1939) is a Twelver Shia '' marja and the second and current Supreme Leader of Iran, in office since 1989. He was previously the third president ...

, in a message to Muslim pilgrims making the annual pilgrimage to Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow ...

. Additionally, the Revolutionary Guards declared that the death sentence on him is still valid.

Rushdie has reported that he still receives a "sort of Valentine's card" from Iran each year on 14 February letting him know the country has not forgotten the vow to kill him and has jokingly referred it as "my unfunny Valentine" in a reference to the song " My Funny Valentine". He said, "It's reached the point where it's a piece of rhetoric rather than a real threat." Despite the threats on Rushdie personally, he said that his family has never been threatened, and that his mother, who lived in Pakistan during the later years of her life, even received outpourings of support. Rushdie himself has been prevented from entering Pakistan, however.

A former bodyguard to Rushdie, Ron Evans, planned to publish a book recounting the behaviour of the author during the time he was in hiding. Evans said Rushdie tried to profit financially from the ''fatwa'' and was suicidal, but Rushdie dismissed the book as a "bunch of lies" and took legal action against Evans, his co-author and their publisher. On 26 August 2008, Rushdie received an apology at the High Court in London from all three parties. A memoir of his years of hiding, ''Joseph Anton'', was released on 18 September 2012. Joseph Anton was Rushdie's secret alias.

In February 1997, Ayatollah Hasan Sane'i, leader of the ''bonyad panzdah-e khordad'' (Fifteenth of Khordad Foundation),

reported that the blood money offered by the foundation for the assassination of Rushdie would be increased from $2 million to $2.5 million. Then a semi-official religious foundation in Iran increased the reward it had offered for the killing of Rushdie from $2.8 million to $3.3 million.

In November 2015, former Indian minister P. Chidambaram acknowledged that banning ''The Satanic Verses'' was wrong. In 1998, Iran's former president Mohammad Khatami proclaimed the fatwa "finished"; but it has never been officially lifted, and in fact has been reiterated several times by Ali Khamenei and other religious officials. Yet more money was added to the bounty in February 2016.

Failed assassination attempt (1989)

On 3 August 1989, while Mustafa Mahmoud Mazeh was priming a book bomb loaded with RDX explosives in a hotel inPaddington

Paddington is an area within the City of Westminster, in Central London. First a medieval parish then a metropolitan borough, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Three important landmarks of the district are Padd ...

, Central London, the bomb exploded prematurely, destroying two floors of the hotel and killing Mazeh. A previously unknown Lebanese group, the Organization of the Mujahidin of Islam, said he died preparing an attack "on the apostate Rushdie". There is a shrine in Tehran's Behesht-e Zahra

Behesht-e Zahra ( fa, بهشت زهرا, lit. ''The Paradise of Zahra'', from Fatima az-Zahra) is the largest cemetery in Iran. Located in the southern part of metropolitan Tehran, it is connected to the city by Tehran Metro Line 1.

History

...

cemetery for Mustafa Mahmoud Mazeh that says he was "Martyred in London, 3 August 1989. The first martyr to die on a mission to kill Salman Rushdie." Mazeh's mother was invited to relocate to Iran, and the Islamic World Movement of Martyrs' Commemoration built his shrine in the cemetery that holds thousands of Iranian soldiers slain in the Iran–Iraq War

The Iran–Iraq War was an armed conflict between Iran and Ba'athist Iraq, Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. It began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for almost eight years, until the acceptance of United Nations S ...

.

Hezbollah's comments (2006)

During the 2006 ''Jyllands-Posten'' Muhammad cartoons controversy, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah declared that "If there had been a Muslim to carry out Imam Khomeini's ''fatwā'' against the renegade Salman Rushdie, this rabble who insult our Prophet Mohammed in Denmark, Norway and France would not have dared to do so. I am sure there are millions of Muslims who are ready to give their lives to defend our prophet's honour and we have to be ready to do anything for that."''International Guerillas'' (1990)

In 1990, soon after the publication of ''The Satanic Verses'', a Pakistani film entitled '' International Gorillay'' (''International Guerillas'') was released that depicted Rushdie as a "James Bond-style villain" plotting to cause the downfall of Pakistan by opening a chain of casinos and discos in the country; he is ultimately killed at the end of the movie. The film was popular with Pakistani audiences, and it "presents Rushdie as aRambo

Rambo is a surname with Norwegian (Vestfold) and Swedish origins. It possibly originated with '' ramn'' + '' bo'', meaning "raven's nest". It has variants in French (''Rambeau'', ''Rambaut'', and ''Rimbaud'') and German (''Rambow''). It is now best ...

-like figure pursued by four Pakistani guerrillas". The British Board of Film Classification

The British Board of Film Classification (BBFC, previously the British Board of Film Censors) is a non-governmental organisation founded by the British film industry in 1912 and responsible for the national classification and censorship of f ...

refused to allow it a certificate, as "it was felt that the portrayal of Rushdie might qualify as criminal libel, causing a breach of the peace as opposed to merely tarnishing his reputation." This effectively prevented the release of the film in the UK. Two months later, however, Rushdie himself wrote to the board, saying that while he thought the film "a distorted, incompetent piece of trash", he would not sue if it were released. He later said, "If that film had been banned, it would have become the hottest video in town: everyone would have seen it". While the film was a great hit in Pakistan, it went virtually unnoticed elsewhere.

Al-Qaeda hit list (2010)

In 2010,Anwar al-Awlaki

Anwar Nasser al-Awlaki (also spelled al-Aulaqi, al-Awlaqi; ar, أنور العولقي, Anwar al-‘Awlaqī; April 21 or 22, 1971 – September 30, 2011) was an American imam who was killed in 2011 in Yemen by a U.S. government drone strik ...

published an Al-Qaeda hit list in ''Inspire'' magazine, including Rushdie along with other figures claimed to have insulted Islam, including Ayaan Hirsi Ali

Ayaan Hirsi Ali (; ; Somali: ''Ayaan Xirsi Cali'':'' Ayān Ḥirsī 'Alī;'' born Ayaan Hirsi Magan, ar, أيان حرسي علي / ALA-LC: ''Ayān Ḥirsī 'Alī'' 13 November 1969) is a Somali-born Dutch-American activist and former politicia ...

, cartoonist Lars Vilks, and three ''Jyllands-Posten'' staff members: Kurt Westergaard, Carsten Juste, and Flemming Rose. The list was later expanded to include Stéphane "Charb" Charbonnier, who was murdered in a terror attack on ''Charlie Hebdo'' in Paris, along with 11 other people. After the attack, Al-Qaeda called for more killings.

Rushdie expressed his support for ''Charlie Hebdo''. He said, "I stand with ''Charlie Hebdo'', as we all must, to defend the art of satire, which has always been a force for liberty and against tyranny, dishonesty and stupidity ... religious totalitarianism has caused a deadly mutation in the heart of Islam and we see the tragic consequences in Paris today." In response to the attack, Rushdie commented on what he perceived as victim-blaming in the media, stating: "You can dislike ''Charlie Hebdo''.... But the fact that you dislike them has nothing to do with their right to speak. The fact you dislike them certainly doesn't in any way excuse their murder."

Jaipur Literature Festival (2012)

Rushdie was due to appear at the Jaipur Literature Festival in January 2012 inJaipur, Rajasthan

Jaipur (; Hindi: ''Jayapura''), formerly Jeypore, is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Rajasthan. , the city had a population of 3.1 million, making it the tenth most populous city in the country. Jaipur is also known a ...

, India. However, he later cancelled his event appearance, and a further tour of India at the time, citing a possible threat to his life as the primary reason. Several days after, he indicated that state police agencies had lied, in order to keep him away, when they informed him that paid assassins were being sent to Jaipur to kill him. Police contended that they were afraid Rushdie would read from the banned ''The Satanic Verses'', and that the threat was real, considering imminent protests by Muslim organizations.

Meanwhile, Indian authors Ruchir Joshi

Ruchir Joshi is an Indian writer, a filmmaker and a columnist for '' The Telegraph'', ''India Today'' as well as other publications. He is best known for his debut novel titled ''The Last Jet-Engine Laugh'' (2001). He is also the editor of India' ...

, Jeet Thayil, Hari Kunzru and Amitava Kumar abruptly left the festival, and Jaipur, after reading excerpts from Rushdie's banned novel at the festival. The four were urged to leave by organizers as there was a real possibility they would be arrested.

A proposed video link session between Rushdie and the Jaipur Literature Festival was also cancelled at the last minute after the government pressured the festival to stop it. Rushdie returned to India to address a conference in New Delhi on 16 March 2012.

Chautauqua attack (2022)

On 12 August 2022, while about to start a lecture at theChautauqua Institution

The Chautauqua Institution ( ) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit education center and summer resort for adults and youth located on in Chautauqua, New York, northwest of Jamestown in the Western Southern Tier of New York State. Established in 1874, the ...

in Chautauqua

Chautauqua ( ) was an adult education and social movement in the United States, highly popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Chautauqua assemblies expanded and spread throughout rural America until the mid-1920s. The Chautauqua br ...

, New York, Rushdie was attacked by a man who rushed onto the stage and stabbed him repeatedly, including in the neck and abdomen. The attacker was pulled away before being taken into custody by a state trooper; Rushdie was airlifted to UPMC Hamot, a tertiary trauma centre in Erie, Pennsylvania

Erie (; ) is a city on the south shore of Lake Erie and the county seat of Erie County, Pennsylvania, United States. Erie is the fifth largest city in Pennsylvania and the largest city in Northwestern Pennsylvania with a population of 94,831 ...

, where he underwent surgery before being put on a ventilator. Security measures at UPMC Hamot were increased due to the potential threat of further attempts on his life. This included 24 hour protection with a security officer outside his room and searches being performed upon entry into the hospital. The suspect was identified as 24-year-old Hadi Matar

On August 12, 2022, a man stabbed novelist Salman Rushdie multiple times as he was about to give a public lecture at the Chautauqua Institution in Chautauqua, New York, United States. A 24-year-old suspect, Hadi Matar, was arrested at the scene, ...

of Fairview, New Jersey. Later in the day, Rushdie's agent, Andrew Wylie, confirmed that Rushdie had received stab injuries to the liver and hand, and that he might lose an eye. A day later, Rushdie was taken off the ventilator and was able to speak, according to his agent, Wylie.

On 23 October 2022, Wylie reported that Rushdie had lost sight in one eye and the use of one hand but survived the murder attempt.

Awards, honours, and recognition

Salman Rushdie has received many plaudits for his writings, including the European Union'sAristeion Prize

The Aristeion Prize was a European literary annual prize. It was given to authors for significant contributions to contemporary European literature, and to translators for exceptional translations of contemporary European literary works.

The priz ...

for Literature, the Premio Grinzane Cavour (Italy), and the Writer of the Year Award in Germany, and many of literature's highest honours.

Awards and honours include:

* Austrian State Prize for European Literature (1993)

* Booker Prize (1981)

* Doctor Honoris Causa from the University of Liège, Belgium (1999)

* Golden PEN Award

*Hans Christian Andersen Literature Award

The Hans Christian Andersen Literature Award is a Danish literary award established in 2010. It is awarded every other year to a living author whose work resembles Hans Christian Andersen. It is one of the biggest literary prizes in the world wit ...

(2014)

* Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters from Indiana University

Indiana University (IU) is a system of public universities in the U.S. state of Indiana.

Campuses

Indiana University has two core campuses, five regional campuses, and two regional centers under the administration of IUPUI.

*Indiana Universi ...

(2018)

* Honorary Doctor of Letters from Emory University

Emory University is a private research university in Atlanta, Georgia. Founded in 1836 as "Emory College" by the Methodist Episcopal Church and named in honor of Methodist bishop John Emory, Emory is the second-oldest private institution of ...

(2015)

* James Joyce Award from University College Dublin

University College Dublin (commonly referred to as UCD) ( ga, Coláiste na hOllscoile, Baile Átha Cliath) is a public research university in Dublin, Ireland, and a member institution of the National University of Ireland. With 33,284 student ...

(2008)

* Outstanding Lifetime Achievement in Cultural Humanism from Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

(2007)

* PEN Pinter Prize (UK)

* St. Louis Literary Award from the Saint Louis University Library Associates

*Swiss Freethinkers Award 2019

Knighthood

Rushdie was knighted for services to literature in the Queen's Birthday Honours on 16 June 2007. He remarked: "I am thrilled and humbled to receive this great honour, and am very grateful that my work has been recognised in this way." In response to his knighthood, many nations with Muslim majorities protested. Parliamentarians of several of these countries condemned the action, and Iran and Pakistan called in their British envoys to protest formally. Controversial condemnation issued by Pakistan's Religious Affairs Minister Muhammad Ijaz-ul-Haq was in turn rebuffed by former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto. Several called publicly for his death. Some non-Muslims expressed disappointment at Rushdie's knighthood, claiming that the writer did not merit such an honour and there were several other writers who deserved the knighthood more than Rushdie. Al-Qaeda condemned the Rushdie honour. The group's then-leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, was quoted as saying in an audio recording that UK's award for Rushdie was "an insult to Islam", and it was planning "a very precise response." Rushdie was appointed a Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH) in the 2022 Birthday Honours for services to literature.Religious and political beliefs

Religious background

Rushdie came from aliberal Muslim

Liberalism and progressivism within Islam involve professed Muslims who have created a considerable body of Progressivism, progressive thought about Islamic understanding and practice. Their work is sometimes characterized as "Progressivism, prog ...

family, but he is now an atheist. In a 2006 interview with PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

, Rushdie called himself a "hardline atheist".

In 1989, in an interview following the ''fatwa'', Rushdie said that he was in a sense a lapsed Muslim, though "shaped by Muslim culture more than any other," and a student of Islam. In another interview the same year, he said, "My point of view is that of a secular human being. I do not believe in supernatural entities, whether Christian, Jewish, Muslim or Hindu."

In 1990, in the "hope that it would reduce the threat of Muslims acting on the fatwa to kill him", he issued a statement claiming he had renewed his Muslim faith, had repudiated the attacks on Islam made by characters in his novel, and was committed to working for better understanding of the religion across the world. Rushdie later said that he was only "pretending".

Rushdie advocates the application of higher criticism, pioneered during the late 19th century. In a guest opinion piece printed in ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'' and ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

'' in mid-August 2005, Rushdie called for a reform in Islam.

Rushdie is a critic of moral and cultural relativism. He favours calling things by their true names and constantly argues about what is wrong and what is right. In an interview with Point of Inquiry in 2006, he described his view as follows:

Rushdie is an advocate of religious satire. He condemned the Charlie Hebdo shooting

On 7 January 2015, at about 11:30 a.m. CET local time, two French Muslim terrorists and brothers, Saïd and Chérif Kouachi, forced their way into the offices of the French satirical weekly newspaper ''Charlie Hebdo'' in Paris. Armed with ...

and defended comedic criticism of religions in a comment originally posted on English PEN

Founded in 1921, English PEN is one of the world's first non-governmental organisations and among the first international bodies advocating for human rights. English PEN was the founding centre of PEN International, a worldwide writers' associat ...

where he called religions a medieval form of unreason. Rushdie called the attack a consequence of "religious totalitarianism", which according to him had caused "a deadly mutation in the heart of Islam". He said:

When asked about reading and writing as a human right, Rushdie states, "the larger stories, the grand narratives that we live in, which are things like nation, and family, and clan, and so on. Those stories are considered to be treated reverentially. They need to be part of the way in which we conduct the discourse of our lives and to prevent people from doing something very damaging to human nature." Though Rushdie believes the freedoms of literature to be universal, the bulk of his fictions portrays the struggles of the marginally underrepresented. This can be seen in his portrayal of the role of women in his novel '' Shame''. In this novel, Rushdie, "suggests that it is women who suffer most from the injustices of the Pakistani social order." His support of feminism can also be seen in a 2015 interview with '' New York'' magazine's '' The Cut''.

Political background

UK politics

In 2006, Rushdie stated that he supported comments byJack Straw

John Whitaker Straw (born 3 August 1946) is a British politician who served in the Cabinet from 1997 to 2010 under the Labour governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. He held two of the traditional Great Offices of State, as Home Secretary ...

, then-Leader of the House of Commons

The leader of the House of Commons is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom whose main role is organising government business in the House of Commons. The leader is generally a member or attendee of the cabinet of t ...

from Labour, who criticized the wearing of the niqab (a veil that covers all of the face except the eyes). Rushdie stated that his three sisters would never wear the veil. He said, "I think the battle against the veil has been a long and continuing battle against the limitation of women, so in that sense I'm completely on Straw's side."

US politics

Rushdie supported the 1999 NATO bombing of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, leading leftist historian

Rushdie supported the 1999 NATO bombing of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, leading leftist historian Tariq Ali

Tariq Ali (; born 21 October 1943) is a Pakistani-British political activist, writer, journalist, historian, filmmaker, and public intellectual. He is a member of the editorial committee of the ''New Left Review'' and ''Sin Permiso'', and con ...

to label Rushdie and other "warrior writers" as "the belligerati". He was supportive of the US-led campaign to remove the Taliban

The Taliban (; ps, طالبان, ṭālibān, lit=students or 'seekers'), which also refers to itself by its state name, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a Deobandi Islamic fundamentalist, militant Islamist, jihadist, and Pasht ...

in Afghanistan, which began in 2001 but was a vocal critic of the 2003 war in Iraq

This is a list of wars involving the Republic of Iraq and its predecessor states.

Other armed conflicts involving Iraq

* Wars during Mandatory Iraq

** Ikhwan raid on South Iraq 1921

* Smaller conflicts, revolutions, coups and periphery confli ...

. He has stated that while there was a "case to be made for the removal of Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolutio ...

", US unilateral

__NOTOC__

Unilateralism is any doctrine or agenda that supports one-sided action. Such action may be in disregard for other parties, or as an expression of a commitment toward a direction which other parties may find disagreeable. As a word, ''un ...

military intervention was unjustifiable. Marxist critic Terry Eagleton

Terence Francis Eagleton (born 22 February 1943) is an English literary theorist, critic, and public intellectual. He is currently Distinguished Professor of English Literature at Lancaster University.

Eagleton has published over forty books, ...

, a former admirer of Rushdie's work, criticized him, saying he "cheered on the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a meton ...

's criminal ventures in Iraq and Afghanistan." Eagleton subsequently apologized for having misrepresented Rushdie's views.

Rushdie supported the election of Democrat Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the ...

for the American presidency and has often criticized the Republican Party. He was involved in the Occupy Movement, both as a presence at Occupy Boston and as a founding member of Occupy Writers. Rushdie is a supporter of gun control, blaming a shooting at a Colorado cinema in July 2012 on the American right to keep and bear arms. He acquired American citizenship in 2016 and voted for Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, diplomat, and former lawyer who served as the 67th United States Secretary of State for President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, as a United States sen ...

in that year's election.

Against religious extremism

In the wake of the ''Jyllands-Posten'' Muhammad cartoons controversy in March 2006—which many considered an echo of the death threats and ''fatwā

A fatwā ( ; ar, فتوى; plural ''fatāwā'' ) is a legal ruling on a point of Islamic law (''sharia'') given by a qualified '' Faqih'' (Islamic jurist) in response to a question posed by a private individual, judge or government. A jurist ...

'' that followed publication of ''The Satanic Verses

''The Satanic Verses'' is the fourth novel of British-Indian writer Salman Rushdie. First published in September 1988, the book was inspired by the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. As with his previous books, Rushdie used magical realism ...

'' in 1989—Rushdie signed the manifesto ''Together Facing the New Totalitarianism'', a statement warning of the dangers of religious extremism

Religious fanaticism, or religious extremism, is a pejorative designation used to indicate uncritical zeal or obsessive enthusiasm which is related to one's own, or one's group's, devotion to a religion – a form of human fanaticism which cou ...

. The Manifesto was published in the left-leaning French weekly '' Charlie Hebdo'' in March 2006.

When Amnesty International suspended human rights activist Gita Sahgal

Gita Sahgal (born 1956/1957) is an Indian writer, journalist, film director, and women's rights and human rights activist, whose work focusses on the issues of feminism, fundamentalism and racism.

She has been a co-founder and active member of ...

for saying to the press that she thought the organization should distance itself from Moazzam Begg

Moazzam Begg ( ur, ; born 5 July 1968 in Sparkhill, Birmingham) is a British Pakistani who was held in extrajudicial detention by the US government in the Bagram Theater Internment Facility and the Guantanamo Bay detainment camp, in Cuba, ...

and his organization, Rushdie said: Amnesty…has done its reputation incalculable damage by allying itself with Moazzam Begg and his groupIn July 2020, Rushdie was one of the 153 signers of the "Harper's Letter" (also known as "Cageprisoners Cage is a London-based advocacy organisation which aims to empower communities impacted by the War on Terror. Cage highlights and campaigns against state policies, developed as part of the War on Terror. The organisation was formed to raise awa ..., and holding them up as human rights advocates. It looks very much as if Amnesty's leadership is suffering from a kind of moral bankruptcy, and has lost the ability to distinguish right from wrong. It has greatly compounded its error by suspending the redoubtable Gita Sahgal for the crime of going public with her concerns. Gita Sahgal is a woman of immense integrity and distinction.… It is people like Gita Sahgal who are the true voices of the human rights movement; Amnesty and Begg have revealed, by their statements and actions, that they deserve our contempt.

A Letter on Justice and Open Debate

"A Letter on Justice and Open Debate", also known as the ''Harper's'' Letter, is an open letter defending free speech published on the ''Harper's Magazine'' website on July 7, 2020, with 153 signatories, criticizing what it called "illiberalism" ...

") that expressed concern that "the free exchange of information and ideas, the lifeblood of a liberal society, is daily becoming more constricted."

South Asian politics and Kashmir

Rushdie has been critical of Pakistan's former Prime Minister Imran Khan, after Khan took personal jabs at him in a 2012 interview where Khan called Rushdie "unbalanced", saying he has the "mindset of a small man", claiming they had "never met" and he would never "want to meet him ever", despite the two being spotted together in public numerous times. Rushdie has expressed his preference for India over Pakistan on numerous occasions in writing and on live television interviews. In one such interview in 2003, Rushdie claimed "Pakistan sucks" after being asked about why he felt more like an outsider there than in India or England. He cited India's diversity, openness, and "richness of life experience" as his preference over Pakistan's "airlessness", resulting from lack of personal freedom, widespread public corruption, and inter-ethnic tension. In Indian politics, Rushdie has criticized theBharatiya Janata Party

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP; ; ) is a political party in India, and one of the two major Indian political parties alongside the Indian National Congress. Since 2014, it has been the ruling political party in India under Narendra Mod ...

and its chairperson, current Prime Minister Narendra Modi

Narendra Damodardas Modi (; born 17 September 1950) is an Indian politician serving as the 14th and current Prime Minister of India since 2014. Modi was the Chief Minister of Gujarat from 2001 to 2014 and is the Member of Parliament fro ...

.