John the Baptist or , , or , ;

[Wetterau, Bruce. ''World history''. New York: Henry Holt and Company. 1994.] syc, ܝܘܿܚܲܢܵܢ ܡܲܥܡܕ݂ܵܢܵܐ, Yoḥanān Maʿmḏānā; he, יוחנן המטביל, Yohanān HaMatbil; la, Ioannes Baptista; cop, ⲓⲱⲁⲛⲛⲏⲥ ⲡⲓⲡⲣⲟⲇⲣⲟⲙⲟⲥ or ;

ar, يوحنا المعمدان;

myz, ࡉࡅࡄࡀࡍࡀ ࡌࡀࡑࡁࡀࡍࡀ, Iuhana Maṣbana.

The name "John" is the Anglicized form, via French, Latin and then Greek, of the Hebrew, "Yochanan", which means "

YHWH

The Tetragrammaton (; ), or Tetragram, is the four-letter Hebrew theonym (transliterated as YHWH), the name of God in the Hebrew Bible. The four letters, written and read from right to left (in Hebrew), are ''yodh'', '' he'', '' waw'', and ' ...

is gracious"., group="note" ( – ) was a mission preacher active in the area of

Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

in the early 1st century AD.

He is also known as John the Forerunner in

Christianity, John the Immerser in some

Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul com ...

Christian traditions, and

Prophet Yahya in

Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

. He is sometimes alternatively referred to as John the Baptiser.

John is mentioned by the

Roman Jewish historian

Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

and he is revered as a major religious figure

[ Funk, Robert W. & the ]Jesus Seminar

The Jesus Seminar was a group of about 50 critical biblical scholars and 100 laymen founded in 1985 by Robert Funk that originated under the auspices of the Westar Institute.''Making Sense of the New Testament'' by Craig Blomberg (Mar 1, 2004 ...

(1998). ''The Acts of Jesus: The search for the Authentic Deeds of Jesus''. San Francisco: Harper; "John the Baptist" cameo, p. 268 in Christianity, Islam, the

Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith is a religion founded in the 19th century that teaches the essential worth of all religions and the unity of all people. Established by Baháʼu'lláh in the 19th century, it initially developed in Iran and parts of the ...

,

the

Druze Faith

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings of H ...

, and

Mandaeism

Mandaeism ( Classical Mandaic: ࡌࡀࡍࡃࡀࡉࡉࡀ ; Arabic: المندائيّة ), sometimes also known as Nasoraeanism or Sabianism, is a Gnostic, monotheistic and ethnic religion. Its adherents, the Mandaeans, revere Adam, Abel, ...

. He is considered to be a

prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the su ...

of

God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

by all of the aforementioned faiths, and is honoured as a

saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Catholic, Eastern Ortho ...

in many

Christian denomination

A Christian denomination is a distinct religious body within Christianity that comprises all church congregations of the same kind, identifiable by traits such as a name, particular history, organization, leadership, theological doctrine, wors ...

s. According to the

New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christi ...

, John anticipated a

messianic figure

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of ''mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach'' i ...

greater than himself,

[ Funk, Robert W. & the ]Jesus Seminar

The Jesus Seminar was a group of about 50 critical biblical scholars and 100 laymen founded in 1985 by Robert Funk that originated under the auspices of the Westar Institute.''Making Sense of the New Testament'' by Craig Blomberg (Mar 1, 2004 ...

(1998). ''The Acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus''. San Francisco: Harper. "Mark", pp. 51–161. and the

Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

s portray John as the precursor or forerunner of

Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

.

Jesus himself identifies John as "

Elijah

Elijah ( ; he, אֵלִיָּהוּ, ʾĒlīyyāhū, meaning "My God is Yahweh/YHWH"; Greek form: Elias, ''Elías''; syr, ܐܸܠܝܼܵܐ, ''Elyāe''; Arabic: إلياس or إليا, ''Ilyās'' or ''Ilyā''. ) was, according to the Books o ...

who is to come", which is a direct reference to the

Book of Malachi (Malachi 4:5), that has been confirmed by the angel who announced John's birth to his father,

Zechariah. According to the

Gospel of Luke

The Gospel of Luke), or simply Luke (which is also its most common form of abbreviation). tells of the origins, birth, ministry, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ. Together with the Acts of the Apostles, it makes up a two-vol ...

, John and Jesus were relatives.

Some scholars maintain that John belonged to the

Essenes

The Essenes (; Hebrew: , ''Isiyim''; Greek: Ἐσσηνοί, Ἐσσαῖοι, or Ὀσσαῖοι, ''Essenoi, Essaioi, Ossaioi'') were a mystic Jewish sect during the Second Temple period that flourished from the 2nd century BCE to the 1st ...

, a semi-

ascetic

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

Jewish sect who expected a messiah and practiced ritual

baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

. John used baptism as the central symbol or

sacrament

A sacrament is a Christian rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments to be a visible symbol of the rea ...

of his pre-messianic movement. Most biblical scholars agree that John

baptized Jesus, and several New Testament accounts report that some of Jesus' early followers had previously been followers of John.

According to the New Testament, John was sentenced to death and

subsequently beheaded by

Herod Antipas

Herod Antipas ( el, Ἡρῴδης Ἀντίπας, ''Hērǭdēs Antipas''; born before 20 BC – died after 39 AD), was a 1st-century ruler of Galilee and Perea, who bore the title of tetrarch ("ruler of a quarter") and is referred to as both "H ...

around AD 30 after John rebuked him for divorcing his wife

Phasaelis

Fasayil or Fasa'il ( ar, فصايل) is a Palestinian village in the northeastern West Bank, a part of the Jericho Governorate, located northwest of Jericho and about southeast of Nablus. The closest Palestinian locality is Duma to the west. Th ...

and then unlawfully wedding

Herodias

Herodias ( el, Ἡρῳδιάς, ''Hērǭdiás''; ''c.'' 15 BC – after AD 39) was a princess of the Herodian dynasty of Judaea during the time of the Roman Empire. Christian writings connect her with John the Baptist's execution.

Family relat ...

, the wife of his brother

Herod Philip I

Herod II (ca. 27 BC – 33/34 AD) was the son of Herod the Great and Mariamne II, the daughter of Simon Boethus the High Priest. For a brief period he was his father's heir apparent, but Herod I removed him from succession in his will. Some writ ...

. Josephus also mentions John in the ''

Antiquities of the Jews

''Antiquities of the Jews'' ( la, Antiquitates Iudaicae; el, Ἰουδαϊκὴ ἀρχαιολογία, ''Ioudaikē archaiologia'') is a 20-volume historiographical work, written in Greek, by historian Flavius Josephus in the 13th year of the re ...

'' and states that he was executed by order of Herod Antipas in the fortress at

Machaerus

Machaerus (Μαχαιροῦς, from grc, μάχαιρα, , makhaira sword he, מכוור; ar, قلعة مكاور, translit=Qala'at Mukawir, lit=Mukawir Castle) was a Hasmonean hilltop palace and desert fortress, now in ruins, located in t ...

.

Followers of John existed well into the 2nd century AD, and some proclaimed him to be the messiah.

In modern times, the followers of John the Baptist are the

Mandaeans

Mandaeans ( ar, المندائيون ), also known as Mandaean Sabians ( ) or simply as Sabians ( ), are an ethnoreligious group who are followers of Mandaeism. They believe that John the Baptist was the final and most important prophet. They ...

, an ancient

ethnoreligious group

An ethnoreligious group (or an ethno-religious group) is a grouping of people who are unified by a common religious and ethnic background.

Furthermore, the term ethno-religious group, along with ethno-regional and ethno-linguistic groups, is a s ...

who believe that he is their greatest and final prophet.

[

]

Gospel narratives

John the Baptist is mentioned in all four canonical Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

s and the non-canonical Gospel of the Nazarenes

The Gospel of the Nazarenes (also ''Nazareans'', ''Nazaraeans'', ''Nazoreans'', or ''Nazoraeans'') is the traditional but hypothetical name given by some scholars to distinguish some of the references to, or citations of, non-canonical Jewish-Chri ...

. The Synoptic Gospels

The gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke are referred to as the synoptic Gospels because they include many of the same stories, often in a similar sequence and in similar or sometimes identical wording. They stand in contrast to John, whose con ...

(Mark

Mark may refer to:

Currency

* Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, the currency of Bosnia and Herzegovina

* East German mark, the currency of the German Democratic Republic

* Estonian mark, the currency of Estonia between 1918 and 1927

* Fin ...

, Matthew

Matthew may refer to:

* Matthew (given name)

* Matthew (surname)

* ''Matthew'' (ship), the replica of the ship sailed by John Cabot in 1497

* ''Matthew'' (album), a 2000 album by rapper Kool Keith

* Matthew (elm cultivar), a cultivar of the C ...

and Luke

People

* Luke (given name), a masculine given name (including a list of people and characters with the name)

* Luke (surname) (including a list of people and characters with the name)

*Luke the Evangelist, author of the Gospel of Luke. Also known ...

) describe John baptising Jesus; in the Gospel of John

The Gospel of John ( grc, Εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Ἰωάννην, translit=Euangélion katà Iōánnēn) is the fourth of the four canonical gospels. It contains a highly schematic account of the ministry of Jesus, with seven "si ...

this is inferred by many to be found in John 1:32.

In Mark

The Gospel of Mark introduces John as a fulfillment of a prophecy from the Book of Isaiah

The Book of Isaiah ( he, ספר ישעיהו, ) is the first of the Latter Prophets in the Hebrew Bible and the first of the Major Prophets in the Christian Old Testament. It is identified by a superscription as the words of the 8th-century BCE ...

(in fact, a conflation of texts from Isaiah, Malachi

Malachi (; ) is the traditional author of the Book of Malachi, the last book of the Nevi'im (Prophets) section of the Tanakh. According to the 1897 ''Easton's Bible Dictionary'', it is possible that Malachi is not a proper name, as it simply mean ...

and Exodus)[Carl R. Kazmierski, ''John the Baptist: Prophet and Evangelist'' (Liturgical Press, 1996) p. 31.] about a messenger being sent ahead, and a voice crying out in the wilderness. John is described as wearing clothes of camel's hair, and living on locust

Locusts (derived from the Vulgar Latin ''locusta'', meaning grasshopper) are various species of short-horned grasshoppers in the family Acrididae that have a swarming phase. These insects are usually solitary, but under certain circumstanc ...

s and wild honey

Honey is a sweet and viscous substance made by several bees, the best-known of which are honey bees. Honey is made and stored to nourish bee colonies. Bees produce honey by gathering and then refining the sugary secretions of plants (primaril ...

. John proclaims baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sin, and says another will come after him who will not baptize with water, but with the Holy Spirit.

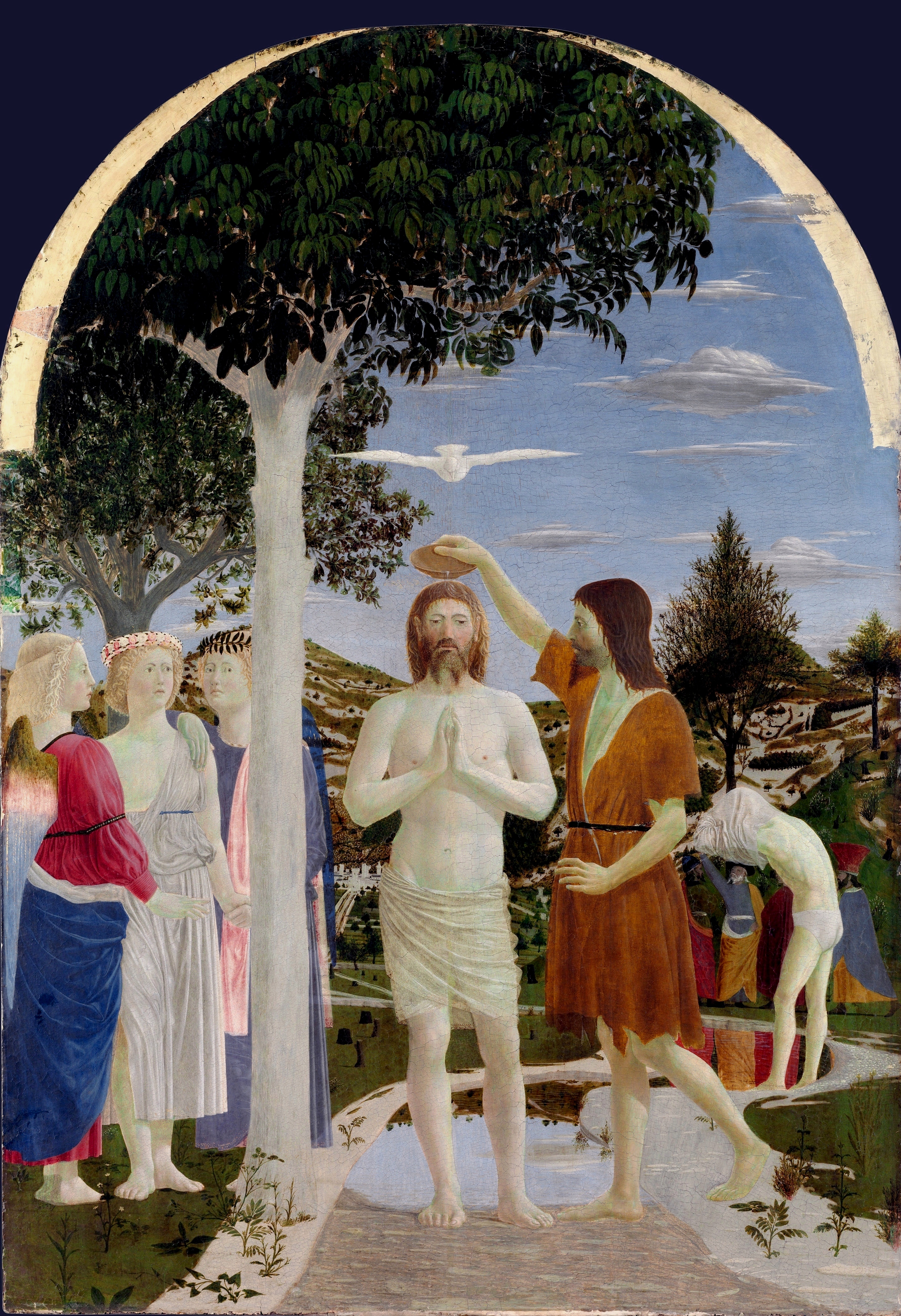

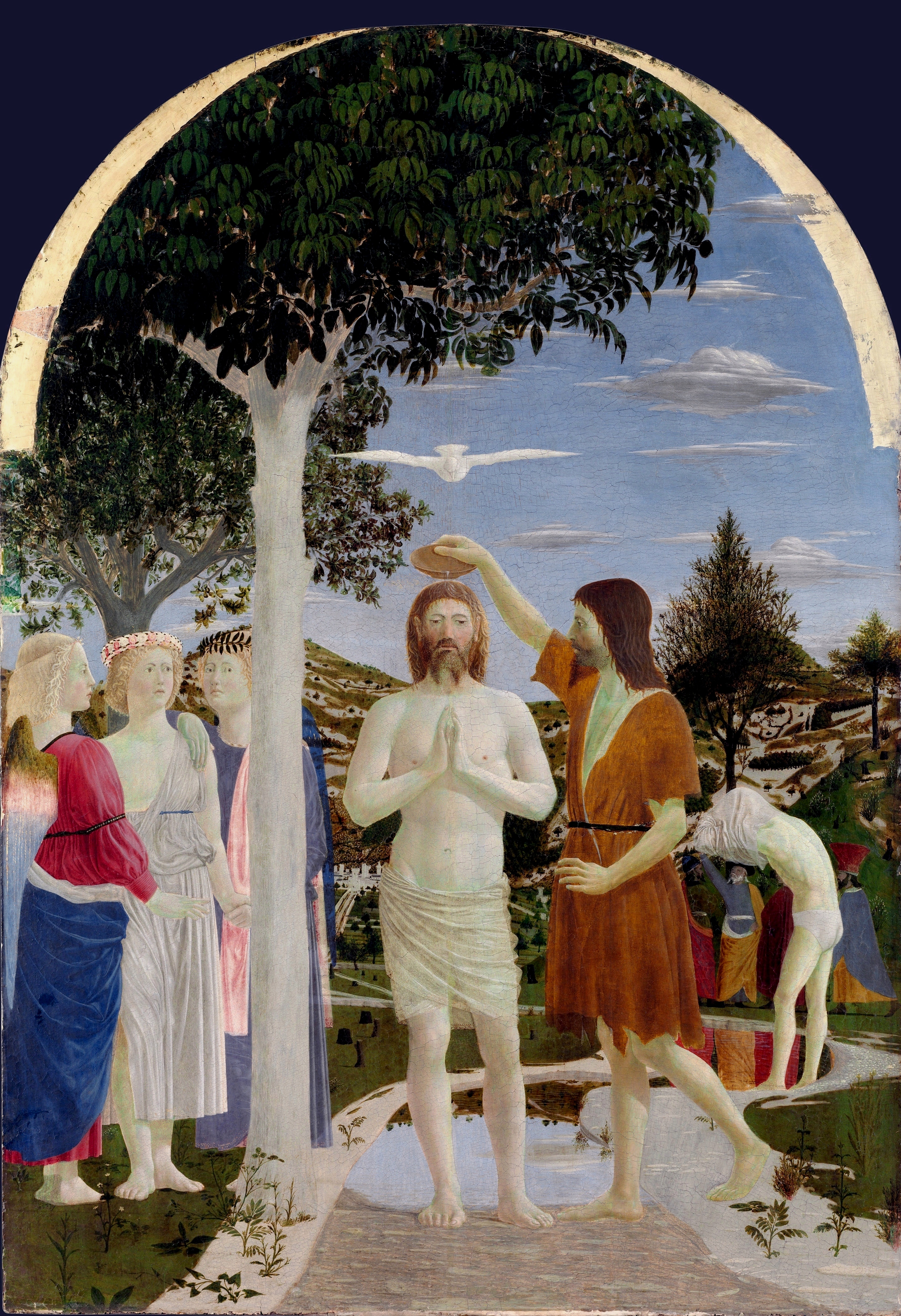

Jesus comes to John, and is baptized by him in the river Jordan. The account describes how, as he emerges from the water, Jesus sees the heavens open and the Holy Spirit descends on him "like a dove", and he hears a voice from heaven that says, "You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased".

Later in the gospel there is an account of John's death. It is introduced by an incident where the Tetrarch

Jesus comes to John, and is baptized by him in the river Jordan. The account describes how, as he emerges from the water, Jesus sees the heavens open and the Holy Spirit descends on him "like a dove", and he hears a voice from heaven that says, "You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased".

Later in the gospel there is an account of John's death. It is introduced by an incident where the Tetrarch Herod Antipas

Herod Antipas ( el, Ἡρῴδης Ἀντίπας, ''Hērǭdēs Antipas''; born before 20 BC – died after 39 AD), was a 1st-century ruler of Galilee and Perea, who bore the title of tetrarch ("ruler of a quarter") and is referred to as both "H ...

, hearing stories about Jesus, imagines that this is John the Baptist raised from the dead. It then explains that John had rebuked Herod for marrying Herodias

Herodias ( el, Ἡρῳδιάς, ''Hērǭdiás''; ''c.'' 15 BC – after AD 39) was a princess of the Herodian dynasty of Judaea during the time of the Roman Empire. Christian writings connect her with John the Baptist's execution.

Family relat ...

, the ex-wife of his brother (named here as Philip). Herodias demands his execution, but Herod, who "liked to listen" to John, is reluctant to do so because he fears him, knowing he is a "righteous and holy man".

The account then describes how Herodias's unnamed daughter dances before Herod, who is pleased and offers her anything she asks for in return. When the girl asks her mother what she should request, she is told to demand the head of John the Baptist. Reluctantly, Herod orders the beheading of John, and his head is delivered to her, at her request, on a plate. John's disciples take the body away and bury it in a tomb.

There are a number of difficulties with this passage. The Gospel refers to Antipas as "King" and the ex-husband of Herodias is named as Philip, but he is known to have been called Herod.

In Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew account begins with the same modified quotation from Isaiah, moving the Malachi and Exodus material to later in the text, where it is quoted by Jesus.

The Gospel of Matthew account begins with the same modified quotation from Isaiah, moving the Malachi and Exodus material to later in the text, where it is quoted by Jesus.

In Luke and Acts

The

The Gospel of Luke

The Gospel of Luke), or simply Luke (which is also its most common form of abbreviation). tells of the origins, birth, ministry, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ. Together with the Acts of the Apostles, it makes up a two-vol ...

adds an account of John's infancy, introducing him as the miraculous son of Zechariah, an old priest, and his wife Elizabeth, who was past menopause

Menopause, also known as the climacteric, is the time in women's lives when menstrual periods stop permanently, and they are no longer able to bear children. Menopause usually occurs between the age of 47 and 54. Medical professionals often ...

and therefore unable to have children. According to this account, the birth of John was foretold by the angel Gabriel

In Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), Gabriel (); Greek: grc, Γαβριήλ, translit=Gabriḗl, label=none; Latin: ''Gabriel''; Coptic: cop, Ⲅⲁⲃⲣⲓⲏⲗ, translit=Gabriêl, label=none; Amharic: am, ገብር� ...

to Zechariah while he was performing his functions as a priest in the temple of Jerusalem. Since he is described as a priest of the course of Abijah Abijah ( ') is a Biblical HebrewPetrovsky, p. 35 unisex nameSuperanskaya, p. 277 which means "my Father is Yah". The Hebrew form ' also occurs in the Bible.

Old Testament characters Women

* Abijah, who married King Ahaz of Judah. She is ...

and Elizabeth as one of the daughters of Aaron, this would make John a descendant of Aaron

According to Abrahamic religions, Aaron ''′aharon'', ar, هارون, Hārūn, Greek (Septuagint): Ἀαρών; often called Aaron the priest ()., group="note" ( or ; ''’Ahărōn'') was a prophet, a high priest, and the elder brother of ...

on both his father's and mother's side. On the basis of this account, the Catholic as well as the Anglican and Lutheran liturgical calendars placed the feast of the Nativity of John the Baptist on 24 June, six months before Christmas.Raymond E. Brown

Raymond Edward Brown (May 22, 1928 – August 8, 1998) was an American Sulpician priest and prominent biblical scholar. He was regarded as a specialist concerning the hypothetical " Johannine community", which he speculated contributed to the a ...

has described it as "of dubious historicity

Historicity is the historical actuality of persons and events, meaning the quality of being part of history instead of being a historical myth, legend, or fiction. The historicity of a claim about the past is its factual status. Historicity denot ...

". Géza Vermes

Géza Vermes, (; 22 June 1924 – 8 May 2013) was a British academic, Biblical scholar, and Judaist of Hungarian Jewish descent—one who also served as a Catholic priest in his youth—and scholar specialized in the field of the history of re ...

has called it "artificial and undoubtedly Luke's creation". The many similarities between the Gospel of Luke story of the birth of John and the Old Testament account of the birth of Samuel

Samuel ''Šəmūʾēl'', Tiberian: ''Šămūʾēl''; ar, شموئيل or صموئيل '; el, Σαμουήλ ''Samouḗl''; la, Samūēl is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transition from the bi ...

suggest that Luke's account of the annunciation and birth of Jesus are modeled on that of Samuel.

Post-nativity

Unique to the Gospel of Luke, John the Baptist explicitly teaches charity, baptizes tax-collectors, and advises soldiers.

The text briefly mentions that John is imprisoned and later beheaded by Herod, but the Gospel of Luke lacks the story of a step-daughter dancing for Herod and requesting John's head.

The Book of Acts portrays some disciples of John becoming followers of Jesus, a development not reported by the gospels except for the early case of Andrew

Andrew is the English form of a given name common in many countries. In the 1990s, it was among the top ten most popular names given to boys in English-speaking countries. "Andrew" is frequently shortened to "Andy" or "Drew". The word is derived ...

, Simon Peter's brother.

In the Gospel of John

The fourth gospel describes John the Baptist as "a man sent from God" who "was not the light", but "came as a witness, to bear witness to the light, so that through him everyone might believe". John confirms that he is not the Christ nor Elijah nor 'the prophet' when asked by Jewish priests and Pharisees; instead, he described himself as the "voice of one crying in the wilderness".

Upon literary analysis, it is clear that John is the "testifier and confessor ''par excellence''", particularly when compared to figures like Nicodemus

Nicodemus (; grc-gre, Νικόδημος, Nikódēmos) was a Pharisee and a member of the Sanhedrin mentioned in three places in the Gospel of John:

* He first visits Jesus one night to discuss Jesus' teachings ().

* The second time Nicodemu ...

.

Jesus's baptism is implied but not depicted. Unlike the other gospels, it is John himself who testifies to seeing "the Spirit come down from heaven like a dove and rest on him". John explicitly announces that Jesus is the one "who baptizes with the Holy Spirit" and John even professes a "belief that he is the Son of God" and "the Lamb of God".

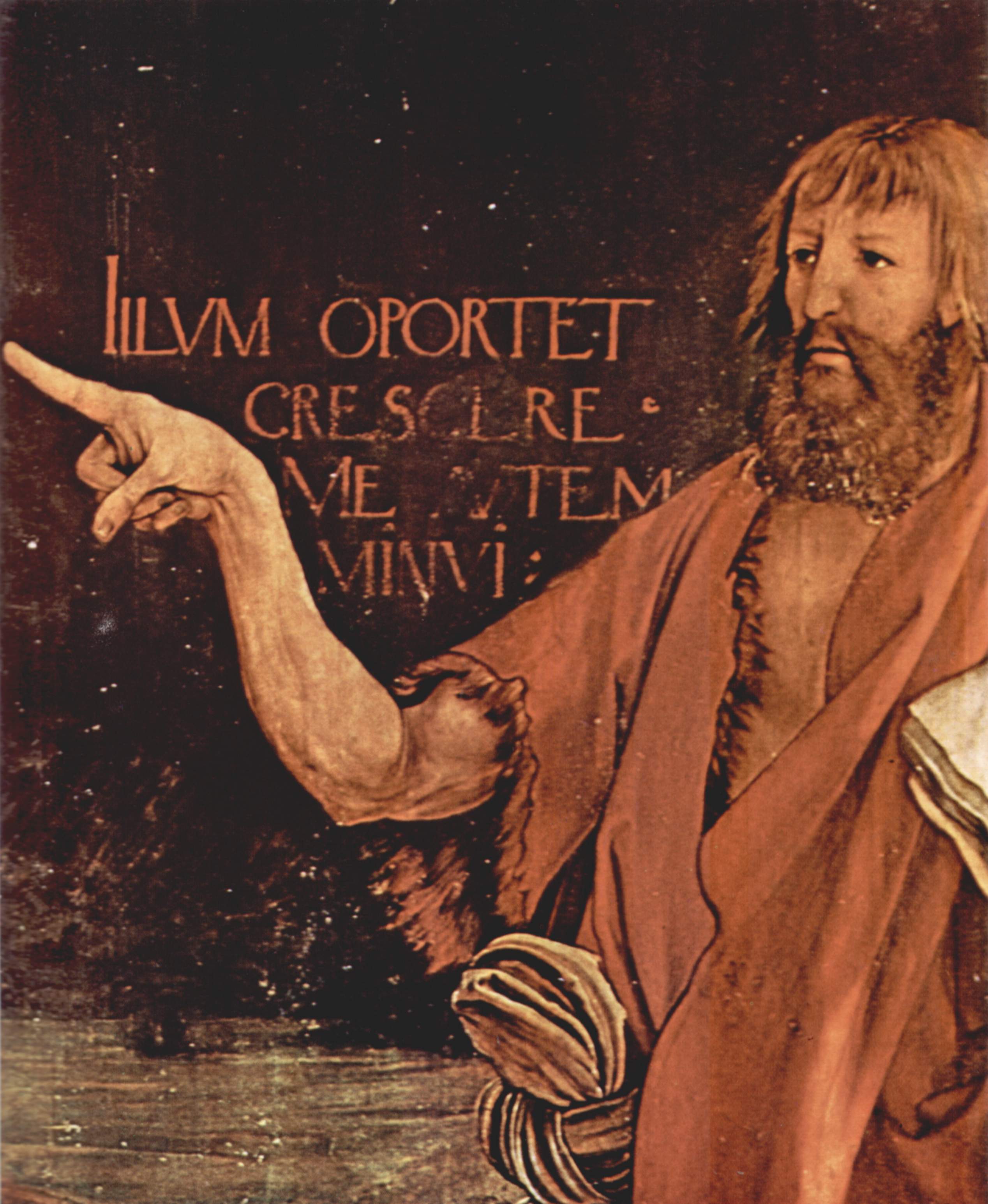

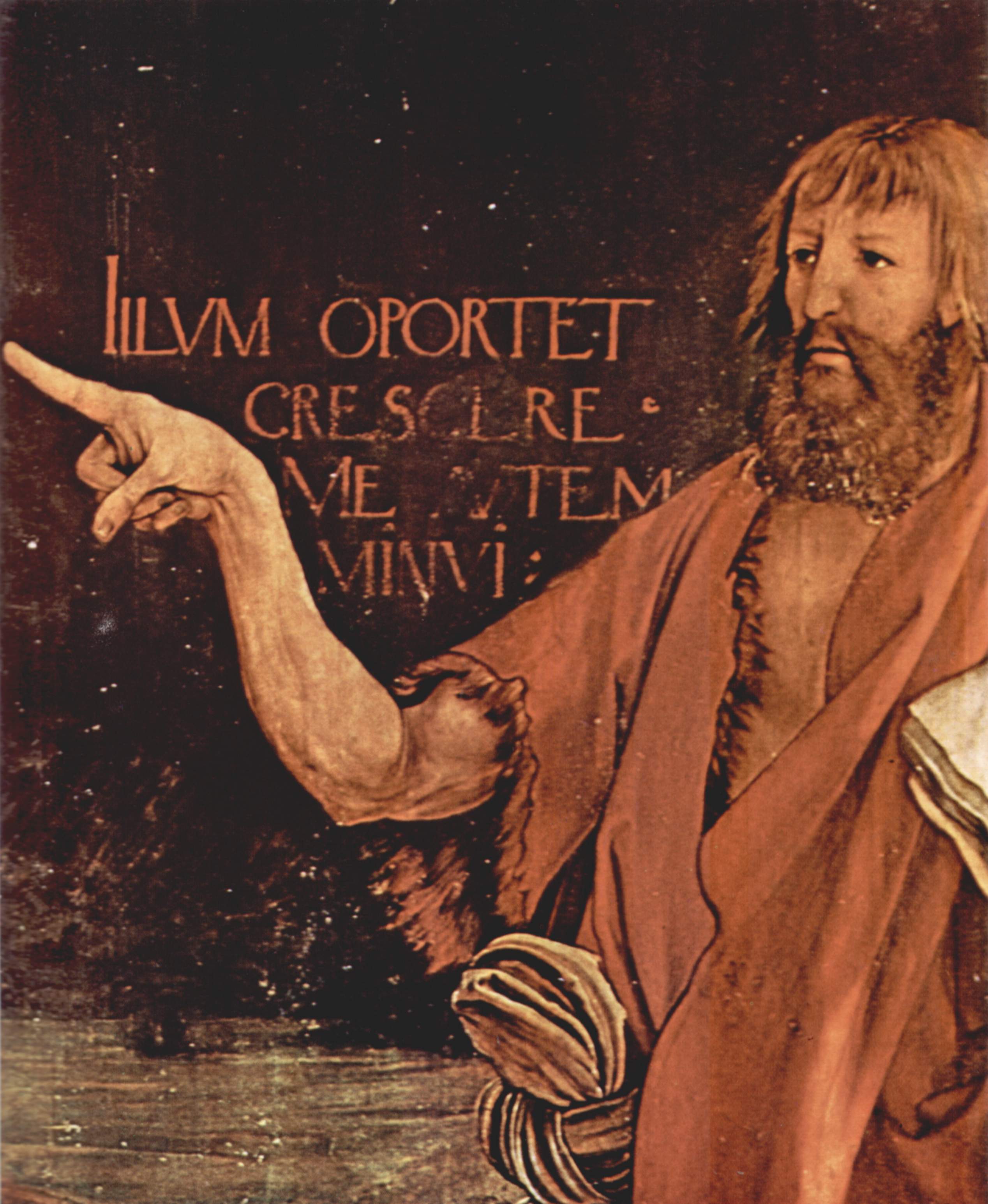

The Gospel of John reports that Jesus' disciples were baptizing and that a debate broke out between some of the disciples of John and another Jew about purification. In this debate John argued that Jesus "must become greater," while he (John) "must become less."

The Gospel of John then points out that Jesus' disciples were baptizing more people than John. Later, the Gospel relates that Jesus regarded John as "a burning and shining lamp, and you were willing to rejoice for a while in his light".

Jesus's baptism is implied but not depicted. Unlike the other gospels, it is John himself who testifies to seeing "the Spirit come down from heaven like a dove and rest on him". John explicitly announces that Jesus is the one "who baptizes with the Holy Spirit" and John even professes a "belief that he is the Son of God" and "the Lamb of God".

The Gospel of John reports that Jesus' disciples were baptizing and that a debate broke out between some of the disciples of John and another Jew about purification. In this debate John argued that Jesus "must become greater," while he (John) "must become less."

The Gospel of John then points out that Jesus' disciples were baptizing more people than John. Later, the Gospel relates that Jesus regarded John as "a burning and shining lamp, and you were willing to rejoice for a while in his light".

Comparative analysis

All four Gospels start Jesus' ministry in association with the appearance of John the Baptist.

The prophecy of Isaiah

Although the Gospel of Mark implies that the arrival of John the Baptist is the fulfilment of a prophecy from the Book of Isaiah

The Book of Isaiah ( he, ספר ישעיהו, ) is the first of the Latter Prophets in the Hebrew Bible and the first of the Major Prophets in the Christian Old Testament. It is identified by a superscription as the words of the 8th-century BCE ...

, the words quoted ("I will send my messenger ahead of you, who will prepare your way – a voice of one calling in the wilderness, 'Prepare the way for the Lord, make straight paths for him.'") are actually a composite of texts from Isaiah

Isaiah ( or ; he, , ''Yəšaʿyāhū'', "God is Salvation"), also known as Isaias, was the 8th-century BC Israelite prophet after whom the Book of Isaiah is named.

Within the text of the Book of Isaiah, Isaiah himself is referred to as "the ...

, Malachi

Malachi (; ) is the traditional author of the Book of Malachi, the last book of the Nevi'im (Prophets) section of the Tanakh. According to the 1897 ''Easton's Bible Dictionary'', it is possible that Malachi is not a proper name, as it simply mean ...

and the Book of Exodus. (Matthew and Luke drop the first part of the reference.)

Baptism of Jesus

The gospels differ on the details of the Baptism. In Mark and Luke, Jesus himself sees the heavens open and hears a voice address him personally, saying, "You are my dearly loved son; you bring me great joy". They do not clarify whether others saw and heard these things. Although other incidents where the "voice came out of heaven" are recorded in which, for the sake of the crowds, it was heard audibly, John did say in his witness that he did see the spirit coming down "out of heaven" (John 12:28–30, John 1:32).

In Matthew, the voice from heaven does not address Jesus personally, saying instead "This is my beloved son, in whom I am well pleased."

In the Gospel of John, John the Baptist himself sees the spirit descend as a dove, testifying about the experience as evidence of Jesus's status.

John's knowledge of Jesus

John's knowledge of Jesus varies across gospels. In the Gospel of Mark, John preaches of a coming leader, but shows no signs of recognizing that Jesus is this leader. In Matthew, however, John immediately recognizes Jesus and John questions his own worthiness to baptize Jesus. In both Matthew and Luke, John later dispatches disciples to question Jesus about his status, asking "Are you he who is to come, or shall we look for another?" In Luke, John is a familial relative of Jesus whose birth was foretold by Gabriel. In the Gospel of John, John the Baptist himself sees the spirit descend like a dove and he explicitly preaches that Jesus is the Son of God.

John and Elijah

The Gospels vary in their depiction of John's relationship to Elijah

Elijah ( ; he, אֵלִיָּהוּ, ʾĒlīyyāhū, meaning "My God is Yahweh/YHWH"; Greek form: Elias, ''Elías''; syr, ܐܸܠܝܼܵܐ, ''Elyāe''; Arabic: إلياس or إليا, ''Ilyās'' or ''Ilyā''. ) was, according to the Books o ...

. Matthew and Mark describe John's attire in a way reminiscent of the description of Elijah in 2 Kings 1:8, who also wore a garment of hair and a leather belt. In Matthew, Jesus explicitly teaches that John is "Elijah who was to come" (Matthew 11:14 – see also Matthew 17:11–13); many Christian theologians have taken this to mean that John was Elijah's successor. In the Gospel of John, John the Baptist explicitly denies being Elijah. In the annunciation narrative in Luke, an angel appears to Zechariah, John's father, and tells him that John "will turn many of the sons of Israel to the Lord their God," and that he will go forth "in the spirit and power of Elijah."

In Josephus' ''Antiquities of the Jews''

An account of John the Baptist is found in all extant manuscripts of the ''Antiquities of the Jews

''Antiquities of the Jews'' ( la, Antiquitates Iudaicae; el, Ἰουδαϊκὴ ἀρχαιολογία, ''Ioudaikē archaiologia'') is a 20-volume historiographical work, written in Greek, by historian Flavius Josephus in the 13th year of the re ...

'' (book 18, chapter 5, 2) by Flavius Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with th ...

(37–100):

According to this passage, the execution of John was blamed for the defeat Herod suffered. Some have claimed that this passage indicates that John died near the time of the destruction of Herod's army in AD 36. However, in a different passage, Josephus states that the end of Herod's marriage with Aretas' daughter (after which John was killed) was only the beginning of hostilities between Herod and Aretas, which later escalated into the battle.

Biblical scholar John Dominic Crossan

John Dominic Crossan (born 17 February 1934) is an Irish-American New Testament scholar, historian of early Christianity, former Catholic priest who was a prominent member of the Jesus Seminar, and emeritus professor at DePaul University. His res ...

differentiates between Josephus's account of John and Jesus, saying, "John had a monopoly, but Jesus had a franchise." To get baptized, Crossan writes, a person went only to John; to stop the movement one only needed to stop John (therefore his movement ended with his death). Jesus invited all to come and see how he and his companions had already accepted the government of God, entered it and were living it. Such a communal praxis was not just for himself, but could survive without him, unlike John's movement.

Relics

Matthew 14:12 records that "his disciples came and took away ohn'sbody and buried it." Theologian Joseph Benson

Joseph Benson (26 January 1749 – 16 February 1821) was an early English Methodist minister, one of the leaders of the movement during the time of Methodism's founder John Wesley.

Life

The son of John Benson and Isabella Robinson, his wife, he ...

refers to a belief that they managed to do so because "it seems that the body had been thrown over the prison walls, without burial, probably by order of Herodias."

The fate of his head

What became of the head of John the Baptist is difficult to determine. Ancient historians Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

, Nicephorus and Symeon Metaphrastes

Symeon, called Metaphrastes or the Metaphrast (; ; died c. 1000), was a Byzantine writer and official. He is regarded as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church and his feast day falls on 9 or 28 November.

He is best known for his 10-volume Greek ...

assumed that Herodias

Herodias ( el, Ἡρῳδιάς, ''Hērǭdiás''; ''c.'' 15 BC – after AD 39) was a princess of the Herodian dynasty of Judaea during the time of the Roman Empire. Christian writings connect her with John the Baptist's execution.

Family relat ...

had it buried in the fortress of Machaerus

Machaerus (Μαχαιροῦς, from grc, μάχαιρα, , makhaira sword he, מכוור; ar, قلعة مكاور, translit=Qala'at Mukawir, lit=Mukawir Castle) was a Hasmonean hilltop palace and desert fortress, now in ruins, located in t ...

.

An Orthodox Christian

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Church ...

tradition holds that, after buried, the head was discovered by John's followers and was taken to the Mount of Olives

The Mount of Olives or Mount Olivet ( he, הַר הַזֵּיתִים, Har ha-Zeitim; ar, جبل الزيتون, Jabal az-Zaytūn; both lit. 'Mount of Olives'; in Arabic also , , 'the Mountain') is a mountain ridge east of and adjacent to Jeru ...

, where it was twice buried and discovered, the latter events giving rise to the Orthodox feast of the First and Second Finding of the Head of St. John the Baptist. Other writers say that it was interred in Herod's palace at Jerusalem; there it was found during the reign of Constantine, and thence secretly taken to Emesa (modern Homs, in Syria), where it was concealed, the place remaining unknown for years, until it was manifested by revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on ...

in 452, Two

Two Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

churches and one mosque claim to have the head of John the Baptist: the Umayyad Mosque

The Umayyad Mosque ( ar, الجامع الأموي, al-Jāmiʿ al-Umawī), also known as the Great Mosque of Damascus ( ar, الجامع الدمشق, al-Jāmiʿ al-Damishq), located in the old city of Damascus, the capital of Syria, is one of the ...

, in Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

(Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

); the church of San Silvestro in Capite

The Basilica of Saint Sylvester the First, also known as ( it, San Silvestro in Capite, la, Sancti Silvestri in Capite), is a Roman Catholic minor basilica and titular church in Rome dedicated to Pope Sylvester I (d. AD 335). It is located on t ...

, in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (Romulus and Remus, legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

...

; and Amiens Cathedral

, image = 0 Amiens - Cathédrale Notre-Dame (1).JPG

, imagesize = 200px

, img capt = Amiens Cathedral

, pushpin map = France

, pushpin label position = below

, coordinates =

, country ...

, in France (the French king would have had it brought from the Holy Land after the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid ...

). A fourth claim is made by the Residenz Museum in Munich, Germany, which keeps a reliquary containing what the Wittelsbach

The House of Wittelsbach () is a German dynasty, with branches that have ruled over territories including Bavaria, the Palatinate, Holland and Zeeland, Sweden (with Finland), Denmark, Norway, Hungary (with Romania), Bohemia, the Electorate o ...

rulers of Bavaria believed to be the head of Saint John.

Right hand relics

An

An Orthodox Christian

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Church ...

monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

in Cetinje, Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

, and the Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Cathedral of Siena

Siena ( , ; lat, Sena Iulia) is a city in Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the province of Siena.

The city is historically linked to commercial and banking activities, having been a major banking center until the 13th and 14th centuri ...

, in Italy, both claim to have John the Baptist's right arm and hand, with which he baptised Jesus.Pope Pius II

Pope Pius II ( la, Pius PP. II, it, Pio II), born Enea Silvio Bartolomeo Piccolomini ( la, Aeneas Silvius Bartholomeus, links=no; 18 October 1405 – 14 August 1464), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 August ...

donated what was identified as the right arm and hand of John the Baptist to the Siena Cathedral.Siena Cathedral

Siena Cathedral ( it, Duomo di Siena) is a medieval church in Siena, Italy, dedicated from its earliest days as a Roman Catholic Marian church, and now dedicated to the Assumption of Mary.

It was the episcopal seat of the Diocese of Siena, and ...

annually in June.

Topkapi Palace, in Istanbul, claims to have John's right hand index finger.

Various relics and traditions

Left hand – St. John the Baptist Church of Chinsurah (India)

The saint's left hand is allegedly preserved in the Armenian Apostolic Church of St. John at Chinsurah, West Bengal

West Bengal (, Bengali: ''Poshchim Bongo'', , abbr. WB) is a state in the eastern portion of India. It is situated along the Bay of Bengal, along with a population of over 91 million inhabitants within an area of . West Bengal is the fou ...

, in India, where each year on "Chinsurah Day" in January it blesses the Armenian Christians of Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, commerc ...

.

Decapitation cloth

The decapitation cloth of Saint John, the cloth which covered his head after his execution, is said to be kept at the Aachen Cathedral

Aachen Cathedral (german: Aachener Dom) is a Roman Catholic church in Aachen, Germany and the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Aachen.

One of the oldest cathedrals in Europe, it was constructed by order of Emperor Charlemagne, who was ...

, in Germany.

Historic Armenia

According to Armenian tradition, the remains of John the Baptist would in some point have been transferred by

According to Armenian tradition, the remains of John the Baptist would in some point have been transferred by Gregory the Illuminator

Gregory the Illuminator ( Classical hy, Գրիգոր Լուսաւորիչ, reformed: Գրիգոր Լուսավորիչ, ''Grigor Lusavorich'';, ''Gregorios Phoster'' or , ''Gregorios Photistes''; la, Gregorius Armeniae Illuminator, cu, Svyas ...

to the Saint Karapet Armenian Monastery.

Bulgaria

In 2010, bones were discovered in the ruins of a Bulgarian church in the St. John the Forerunner Monastery (4th–17th centuries) on the Black Sea island of Sveti Ivan (Saint John) and two years later, after DNA and radio carbon testing proved the bones belonged to a Middle Eastern man who lived in the 1st century AD, scientists said that the remains could conceivably have belonged to John the Baptist.Sozopol

Sozopol ( bg, Созопол , el, Σωζόπολη, translit=Sozopoli) is an ancient seaside town located 35 km south of Burgas on the southern Bulgarian Black Sea Coast. Today it is one of the major seaside resorts in the country, known for th ...

.

Egypt

A crypt and relics said to be John's and mentioned in 11th- and 16th-century manuscripts, were discovered in 1969 during restoration of the Church of St. Macarius at the

A crypt and relics said to be John's and mentioned in 11th- and 16th-century manuscripts, were discovered in 1969 during restoration of the Church of St. Macarius at the Monastery of Saint Macarius the Great

The Monastery of Saint Macarius The Great also known as Dayr Aba Maqār ( ar, دير الأنبا مقار) is a Coptic Orthodox monastery located in Wadi El Natrun, Beheira Governorate, about north-west of Cairo, and off the highway betwee ...

in Scetes

Wadi El Natrun (Arabic: "Valley of Natron"; Coptic: , "measure of the hearts") is a depression in northern Egypt that is located below sea level and below the Nile River level. The valley contains several alkaline lakes, natron-rich salt de ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

.

Nagorno-Karabakh

Additional relics are claimed to reside in Gandzasar Monastery's Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, in Nagorno-Karabakh

Nagorno-Karabakh ( ) is a landlocked region in the South Caucasus, within the mountainous range of Karabakh, lying between Lower Karabakh and Syunik, and covering the southeastern range of the Lesser Caucasus mountains. The region is mos ...

.

Purported left finger bone

The bone of one of John the Baptist's left fingers is said to be at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art is an art museum in Kansas City, Missouri, known for its encyclopedic collection of art from nearly every continent and culture, and especially for its extensive collection of Asian art.

In 2007, ''Time'' maga ...

in Kansas City, Missouri

Kansas City (abbreviated KC or KCMO) is the largest city in Missouri by population and area. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 508,090 in 2020, making it the 36th most-populous city in the United States. It is the central ...

. It is held in a Gothic-style monstrance

A monstrance, also known as an ostensorium (or an ostensory), is a vessel used in Roman Catholic, Old Catholic, High Church Lutheran and Anglican churches for the display on an altar of some object of piety, such as the consecrated Eucharistic ...

made of gilded silver that dates back to 14th century Lower Saxony

Lower Saxony (german: Niedersachsen ; nds, Neddersassen; stq, Läichsaksen) is a German state (') in northwestern Germany. It is the second-largest state by land area, with , and fourth-largest in population (8 million in 2021) among the 16 ...

.

Halifax, England

Another obscure claim relates to the town of Halifax in West Yorkshire, United Kingdom, where, as patron saint of the town, the Baptist's head appears on the official coat-of-arms. One legend (among others) bases the etymology of the town's place-name on "halig" (holy) and "fax" (hair), claiming that a relic of the head, or face, of John the Baptist once existed in the town.

Religious views

Christianity

The Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

s describe John the Baptist as having had a specific role ordained by God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

as forerunner or precursor of Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

, who was the foretold Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashia ...

. The New Testament Gospels speak of this role. In Luke 1:17 the role of John is referred to as being "to turn the hearts of the fathers to the children, and the disobedient to the wisdom of the just; to make ready a people prepared for the Lord." In Luke 1:76 as "thou shalt go before the face of the Lord to prepare his ways" and in Luke 1:77 as being "To give knowledge of salvation unto his people by the remission of their sins."

There are several passages within the Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

which are interpreted by Christians as being prophetic

In religion, a prophecy is a message that has been communicated to a person (typically called a ''prophet'') by a supernatural entity. Prophecies are a feature of many cultures and belief systems and usually contain divine will or law, or pr ...

of John the Baptist in this role. These include a passage in the Book of Malachi that refers to a prophet who would "prepare the way of the Lord":

Also at the end of the next chapter in Malachi 4:5–6 it says,

The Jews of Jesus' day expected Elijah to come before the Messiah; indeed, some present day Jews continue to await Elijah's coming as well, as in the Cup of Elijah the Prophet in the Passover Seder

The Passover Seder (; he, סדר פסח , 'Passover order/arrangement'; yi, סדר ) is a ritual feast at the beginning of the Jewish holiday of Passover. It is conducted throughout the world on the eve of the 15th day of Nisan in the Hebrew c ...

. This is why the disciples ask Jesus in Matthew 17:10, "Why then say the scribes that Elias must first come?" The disciples are then told by Jesus that Elijah came in the person of John the Baptist,

These passages are applied to John in the Synoptic Gospels

The gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke are referred to as the synoptic Gospels because they include many of the same stories, often in a similar sequence and in similar or sometimes identical wording. They stand in contrast to John, whose con ...

. But where Matthew specifically identifies John the Baptist as Elijah's spiritual successor, the gospels of Mark and Luke are silent on the matter. The Gospel of John

The Gospel of John ( grc, Εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Ἰωάννην, translit=Euangélion katà Iōánnēn) is the fourth of the four canonical gospels. It contains a highly schematic account of the ministry of Jesus, with seven "si ...

states that John the Baptist denied that he was Elijah.

Influence on Paul

Many scholars believe there was contact between the early church in the Apostolic Age

Christianity in the 1st century covers the formative history of Christianity from the start of the ministry of Jesus (–29 AD) to the death of the last of the Twelve Apostles () and is thus also known as the Apostolic Age. Early Christianity ...

and what is called the "Qumran

Qumran ( he, קומראן; ar, خربة قمران ') is an archaeological site in the West Bank managed by Israel's Qumran National Park. It is located on a dry marl plateau about from the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea, near the Israeli ...

-Essene

The Essenes (; Hebrew: , ''Isiyim''; Greek: Ἐσσηνοί, Ἐσσαῖοι, or Ὀσσαῖοι, ''Essenoi, Essaioi, Ossaioi'') were a mystic Jewish sect during the Second Temple period that flourished from the 2nd century BCE to the 1st ce ...

community".Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls (also the Qumran Caves Scrolls) are ancient Jewish and Hebrew religious manuscripts discovered between 1946 and 1956 at the Qumran Caves in what was then Mandatory Palestine, near Ein Feshkha in the West Bank, on the nor ...

were found at Qumran, which the majority of historians and archaeologists identify as an Essene settlement. John the Baptist is thought to have been either an Essene or "associated" with the community at Khirbet Qumran. According to the Book of Acts, Paul met some "disciples of John" in Ephesus

Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἔφεσος, Éphesos; tr, Efes; may ultimately derive from hit, 𒀀𒉺𒊭, Apaša) was a city in ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in ...

.

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church commemorates Saint John the Baptist on two feast days:

* 24 June –

The Catholic Church commemorates Saint John the Baptist on two feast days:

* 24 June – Nativity of Saint John the Baptist

The Nativity of John the Baptist (or Birth of John the Baptist, or Nativity of the Forerunner, or colloquially Johnmas or St. John's Day (in German) Johannistag) is a Christian feast day celebrating the birth of John the Baptist. It is observed ...

* 29 August – Beheading of Saint John the Baptist

The beheading of John the Baptist, also known as the decollation of Saint John the Baptist or the beheading of the Forerunner, is a biblical event commemorated as a holy day by various Christian churches. According to the New Testament, Herod ...

According to Frederick Holweck, at the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary to his mother Elizabeth, as recounted in Luke 1:39–57, John, sensing the presence of his Jesus, upon the arrival of Mary, leaped in the womb of his mother; he was then cleansed from original sin and filled with the grace of God. In her ''Treatise of Prayer'', Saint Catherine of Siena

Catherine of Siena (Italian: ''Caterina da Siena''; 25 March 1347 – 29 April 1380), a member of the Third Order of Saint Dominic, was a mystic, activist, and author who had a great influence on Italian literature and on the Catholic Church. ...

includes a brief altercation with the Devil

A devil is the personification of evil as it is conceived in various cultures and religious traditions. It is seen as the objectification of a hostile and destructive force. Jeffrey Burton Russell states that the different conceptions of t ...

regarding her fight due to the Devil attempting to lure her with vanity

Vanity is the excessive belief in one's own abilities or attractiveness to others. Prior to the 14th century it did not have such narcissistic undertones, and merely meant ''futility''. The related term vainglory is now often seen as an archaic ...

and flattery

Flattery (also called adulation or blandishment) is the act of giving excessive compliments, generally for the purpose of ingratiating oneself with the subject. It is also used in pick-up lines when attempting to initiate sexual or romantic cou ...

. Speaking in the first person, Catherine responds to the Devil with the following words:

Eastern Christianity

The

The Eastern Catholic Churches

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also called the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous (''sui iuris'') particular churches of th ...

and Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or "canonical") ...

faithful believe that John was the last of the Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the su ...

s, thus serving as a bridge between that period of revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on ...

and the New Covenant

The New Covenant (Hebrew '; Greek ''diatheke kaine'') is a biblical interpretation which was originally derived from a phrase which is contained in the Book of Jeremiah ( Jeremiah 31:31-34), in the Hebrew Bible (or the Old Testament of the Ch ...

. They also teach that, following his death, John descended into Hades

Hades (; grc-gre, ᾍδης, Háidēs; ), in the ancient Greek religion and myth, is the god of the dead and the king of the underworld, with which his name became synonymous. Hades was the eldest son of Cronus and Rhea, although this also m ...

and there once more preached that Jesus the Messiah was coming, so he was the Forerunner of Christ in death as he had been in life. Eastern Catholic and Orthodox churches will often have an icon

An icon () is a religious work of art, most commonly a painting, in the cultures of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Catholic churches. They are not simply artworks; "an icon is a sacred image used in religious devotion". The most c ...

of Saint John the Baptist in a place of honor on the iconostasis

In Eastern Christianity, an iconostasis ( gr, εἰκονοστάσιον) is a wall of icons and religious paintings, separating the nave from the sanctuary in a church. ''Iconostasis'' also refers to a portable icon stand that can be placed ...

, and he is frequently mentioned during the Divine Services

In the practice of Christianity, canonical hours mark the divisions of the day in terms of fixed times of prayer at regular intervals. A book of hours, chiefly a breviary, normally contains a version of, or selection from, such prayers.

In t ...

. Every Tuesday throughout the year is dedicated to his memory.

The Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

remembers Saint John the Forerunner on six separate feast days, listed here in order in which they occur during the church year

The liturgical year, also called the church year, Christian year or kalendar, consists of the cycle of liturgical seasons in Christian churches that determines when feast days, including celebrations of saints, are to be observed, and which ...

(which begins on 1 September):

* 23 September –

* 12 October – Translation

Translation is the communication of the Meaning (linguistic), meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The ...

from Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

to Gatchina

The town of Gatchina ( rus, Га́тчина, , ˈɡatːɕɪnə, links=y) serves as the administrative center of the Gatchinsky District in Leningrad Oblast, Russia. It lies south-south-west of St. Petersburg, along the E95 highway which ...

: of a Particle of the Life Giving Cross, the Filersk Icon of the Mother of God, and the relic

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains of a saint or the personal effects of the saint or venerated person preserved for purposes of veneration as a tangi ...

of the

* 7 January – . This is his main feast day, immediately after Theophany

Theophany (from Ancient Greek , meaning "appearance of a deity") is a personal encounter with a deity, that is an event where the manifestation of a deity occurs in an observable way. Specifically, it "refers to the temporal and spatial manifest ...

on 6 January (7 January also commemorates the transfer of the relic of the right hand of John the Baptist from Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

to Constantinople in 956)

* 24 February –

* 25 May –

* 24 June – Nativity of Saint John the Forerunner

* 29 August – The Beheading of Saint John the Forerunner, a day of strict fast and abstinence from meat and dairy products and foods containing meat or dairy products

In addition to the above, 5 September is the commemoration of Zacharias and Elizabeth, Saint John's parents.

The Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

observes 12 October as the Transfer of the Right Hand of the Forerunner from Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

to Gatchina

The town of Gatchina ( rus, Га́тчина, , ˈɡatːɕɪnə, links=y) serves as the administrative center of the Gatchinsky District in Leningrad Oblast, Russia. It lies south-south-west of St. Petersburg, along the E95 highway which ...

(1799).

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a nontrinitarian Christian church that considers itself to be the restoration of the original church founded by Jesus Christ. The ch ...

teaches that modern revelation confirms the biblical account of John and also makes known additional events in his ministry. According to this belief, John was "ordained by the angel of God" when he was eight days old "to overthrow the kingdom of the Jews" and to prepare a people for the Lord. Latter-day Saints also believe that "he was baptized while yet in his childhood."

Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, he ...

said: "Let us come into New Testament times – so many are ever praising the Lord and His apostles. We will commence with John the Baptist. When Herod's edict went forth to destroy the young children, John was about six months older than Jesus, and came under this hellish edict, and Zecharias caused his mother to take him into the mountains, where he was raised on locusts and wild honey. When his father refused to disclose his hiding place, and being the officiating high priest at the Temple that year, was slain by Herod's order, between the porch and the altar, as Jesus said."

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints teaches that John the Baptist appeared on the banks of the Susquehanna River

The Susquehanna River (; Lenape: Siskëwahane) is a major river located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, overlapping between the lower Northeast and the Upland South. At long, it is the longest river on the East Coast of the Uni ...

near Harmony Township, Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania

Harmony Township is a township in Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 512 at the 2020 census.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the township has a total area of , of which is land and ...

, as a resurrected being to Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, he ...

and Oliver Cowdery

Oliver H. P. Cowdery (October 3, 1806 – March 3, 1850) was an American Mormon leader who, with Joseph Smith, was an important participant in the formative period of the Latter Day Saint movement between 1829 and 1836. He was the first baptized ...

on 15 May 1829, and ordained them to the Aaronic priesthood. According to the Church's dispensational view of religious history, John's ministry has operated in three dispensations: he was the last of the prophets under the law of Moses; he was the first of the New Testament prophets; and he was sent to restore the Aaronic priesthood in our day (the dispensation of the fulness of times). Latter-day Saints believe John's ministry was foretold by two prophets whose teachings are included in the Book of Mormon

The Book of Mormon is a religious text of the Latter Day Saint movement, which, according to Latter Day Saint theology, contains writings of ancient prophets who lived on the American continent from 600 BC to AD 421 and during an interlude dat ...

: Lehi and his son Nephi.

Unification Church

The Unification Church

The Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, widely known as the Unification Church, is a new religious movement, whose members are called Unificationists, or " Moonies". It was officially founded on 1 May 1954 under the name Holy S ...

teaches that God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

intended John to help Jesus during his public ministry in Judea. In particular, John should have done everything in his power to persuade the Jewish people that Jesus was the Messiah. He was to become Jesus' main disciple and John's disciples were to become Jesus' disciples. Unfortunately, John did not follow Jesus and continued his own way of baptizing people. Moreover, John also denied that he was Elijah when queried by several Jewish leaders, contradicting Jesus who stated John is Elijah who was to come. Many Jews therefore could not accept Jesus as the Messiah because John denied being Elijah, as the prophet's appearance was a prerequisite for the Messiah's arrival as stated in Malachi 4:5. According to the Unification Church, "John the Baptist was in the position of representing Elijah's physical body, making himself identical with Elijah from the standpoint of their mission."

According to Matthew 11:11, Jesus stated "there has not risen one greater than John the Baptist." However, in referring to John's blocking the way of the Jews' understanding of him as the Messiah, Jesus said "yet he who is least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he." John's failure to follow Jesus became the chief obstacle to the fulfillment of Jesus' mission.

Syrian-Egyptian Gnosticism

Among the early Judeo-Christian Gnostics the Ebionites

Ebionites ( grc-gre, Ἐβιωναῖοι, ''Ebionaioi'', derived from Hebrew (or ) ''ebyonim'', ''ebionim'', meaning 'the poor' or 'poor ones') as a term refers to a Jewish Christian sect, which viewed poverty as a blessing, that existed durin ...

held that John, along with Jesus and James the Just

James the Just, or a variation of James, brother of the Lord ( la, Iacobus from he, יעקב, and grc-gre, Ἰάκωβος, , can also be Anglicized as "Jacob"), was "a brother of Jesus", according to the New Testament. He was an early lead ...

– all of whom they revered – were vegetarians.[J Verheyden, ''Epiphanius on the Ebionites'', in ''The image of the Judaeo-Christians in ancient Jewish and Christian literature'', eds Peter J. Tomson, Doris Lambers-Petry, , p. 188 "The vegetarianism of John the Baptist and of Jesus is an important issue too in the Ebionite interpretation of the Christian life. "][ p. 102 – "Probably the most interesting of the changes from the familiar New Testament accounts of Jesus comes in the Gospel of the Ebionites description of John the Baptist, who, evidently, like his successor Jesus, maintained a strictly vegetarian cuisine."][ p. 104 – "And when he had been brought to Archelaus and the doctors of the Law had assembled, they asked him who he is and where he has been until then. And to this he made answer and spake: ''I am pure; orthe Spirit of God hath led me on, and live oncane and roots and tree-food.''"] Epiphanius of Salamis

Epiphanius of Salamis ( grc-gre, Ἐπιφάνιος; c. 310–320 – 403) was the bishop of Salamis, Cyprus, at the end of the 4th century. He is considered a saint and a Church Father by both the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Churches. He g ...

records that this group had amended their Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew), or simply Matthew. It is most commonly abbreviated as "Matt." is the first book of the New Testament of the Bible and one of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells how Israel's Messiah, Jesus, comes to his people and for ...

– known today as the Gospel of the Ebionites

The Gospel of the Ebionites is the conventional name given by scholars to an apocryphal gospel extant only as seven brief quotations in a heresiology known as the ''Panarion'', by Epiphanius of Salamis; he misidentified it as the "Hebrew" gos ...

– to change where John eats "locusts" to read "honey cakes" or "manna

Manna ( he, מָן, mān, ; ar, اَلْمَنُّ; sometimes or archaically spelled mana) is, according to the Bible, an edible substance which God provided for the Israelites during their travels in the desert during the 40-year period follow ...

".[ p. 13 – Referring to Epiphanius' quotation from the ''Gospel of the Ebionites'' in ''Panarion'' 30.13, "And his food, it says, was wild honey whose taste was of ''manna'', as cake in oil".]

Mandaeism

John the Baptist, or Yuhana Maṣbana ( myz, ࡉࡅࡄࡀࡍࡀ ࡌࡀࡑࡁࡀࡍࡀ, lit=John the Baptizer )Mandaean

Mandaeans ( ar, المندائيون ), also known as Mandaean Sabians ( ) or simply as Sabians ( ), are an ethnoreligious group who are followers of Mandaeism. They believe that John the Baptist was the final and most important prophet. They ...

s. Mandaeans also refer to him as (John, son of Zechariah).Ginza Rabba

The Ginza Rabba ( myz, ࡂࡉࡍࡆࡀ ࡓࡁࡀ, translit=Ginzā Rbā, lit=Great Treasury), Ginza Rba, or Sidra Rabba ( myz, ࡎࡉࡃࡓࡀ ࡓࡁࡀ, translit=Sidrā Rbā, lit=Great Book), and formerly the Codex Nasaraeus, is the longest ...

and the Mandaean Book of John

The Mandaean Book of John (Mandaic language ࡃࡓࡀࡔࡀ ࡖࡉࡀࡄࡉࡀ ') is a Mandaean holy book in Mandaic Aramaic which is believed by Mandeans to have been written by their prophet John the Baptist.

The book contains accounts of Jo ...

. Mandaeans believe that they descend directly from John's original disciples[Drower, Ethel Stefana. 2002. The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran: Their Cults, Customs, Magic Legends, and Folklore (reprint). Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press.] According to Mandaeism, John was a great teacher, a Nasoraean and renewer of the faith.[ John is a messenger of Light () and Truth () who possessed the power of healing and full ]Gnosis

Gnosis is the common Greek noun for knowledge ( γνῶσις, ''gnōsis'', f.). The term was used among various Hellenistic religions and philosophies in the Greco-Roman world. It is best known for its implication within Gnosticism, where it s ...

().[Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2010). Turning the Tables on Jesus: The Mandaean View. In (pp94-111). Minneapolis: Fortress Press] Scholars such as Mark Lidzbarski

Mark Lidzbarski (born Abraham Mordechai Lidzbarski, Płock, Russian Empire, 7 January 1868 – Göttingen, 13 November 1928) was a Polish philologist, Semitist and translator of Mandaean texts.

Early life and education

Lidzbarski was born in ...

, Rudolf Macúch

Rudolf Macuch (16 October 1919, in Bzince pod Javorinou – 23 July 1993, in Berlin) was a Slovak linguist, naturalized as German after 1974.

He was noted in the field of Semitic studies for his research work in three main areas: (1) Mandaic s ...

, Ethel S. Drower, Jorunn J. Buckley

Jorunn Jacobsen Buckley (born Jorunn Jacobsen in 1944 in Norway) is an American religious studies scholar and historian of religion known for her work on Mandaeism and Gnosticism. She was a former Professor of Religion at Bowdoin College. She is kn ...

, and believe that the Mandaeans likely have a historical connection with John's original disciples.[Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2002), The Mandaeans: ancient texts and modern people (PDF), Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195153859] Mandaeans believe that John was married, with his wife named Anhar, and had children.Mandaean Book of John

The Mandaean Book of John (Mandaic language ࡃࡓࡀࡔࡀ ࡖࡉࡀࡄࡉࡀ ') is a Mandaean holy book in Mandaic Aramaic which is believed by Mandeans to have been written by their prophet John the Baptist.

The book contains accounts of Jo ...

.

Islam

John the Baptist is known as Yaḥyā ibn Zakariyā ( ar, يحيى بن زكريا) in Islam and is honoured as a prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the su ...

. He is believed by Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abraha ...

s to have been a witness to the word of God, and a prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the su ...

who would herald the coming of Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

. His father Zechariah was also an Islamic prophet. Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

ic tradition maintains that John met Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

on the night of the Mi'raj

The Israʾ and Miʿraj ( ar, الإسراء والمعراج, ') are the two parts of a Night Journey that, according to Islam, the Islamic prophet Muhammad (570–632) took during a single night around the year 621 (1 BH – 0 BH). With ...

, along with Jesus in the second heaven. John's story was also told to the Abyssinian king during the Muslim refugees' Migration to Abyssinia

The migration to Abyssinia ( ar, الهجرة إلى الحبشة, translit=al-hijra ʾilā al-habaša), also known as the First Hijra ( ar, الهجرة الأولى, translit=al-hijrat al'uwlaa, label=none), was an episode in the early histor ...

. According to the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing. ...

, John was one on whom God sent peace on the day that he was born and the day that he died.

Quranic mentions

The Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing. ...

claims that John the Baptist was the first to receive this name () but since the name Yoḥanan occurs many times before John the Baptist, this verse is referring either to Islamic scholar consensus that "Yaḥyā" is not the same name as "Yoḥanan"Biblical

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

account of the miraculous

A miracle is an event that is inexplicable by natural or scientific lawsOne dictionary define"Miracle"as: "A surprising and welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore considered to be the work of a divi ...

naming of John, which accounted that he was almost named "Zacharias" (Greek: ) after his father's name, as no one in the lineage of his father Zacharias (also known as Zechariah) had been named "John" ("Yohanan"/"Yoannes") before him.

In the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing. ...

, God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

frequently mentions Zechariah's continuous praying for the birth of a son. Zechariah's wife, mentioned in the New Testament as Elizabeth, was barren and therefore the birth of a child seemed impossible.[''Lives of the Prophets'', Leila Azzam, ''John and Zechariah''] As a gift from God, Zechariah (or Zakaria) was given a son by the name of "Yaḥya" or "John", a name specially chosen for this child alone. In accordance with Zechariah's prayer, God made John and Jesus, who according to exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Biblical works. In modern usage, exegesis can involve critical interpretation ...

was born six months later,[''A–Z of Prophets in Islam and Judaism'', B. M. Wheeler, ''John the Baptist''] renew the message of God, which had been corrupted and lost by the Israelites

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele ...

. As the Quran says:

John was exhorted to hold fast to the Scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual pra ...

and was given wisdom by God while still a child.Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abraha ...

exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Biblical works. In modern usage, exegesis can involve critical interpretation ...

narrates that Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

sent John out with twelve disciples, who preached the message before Jesus called his own disciples.Sufism

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, ...

as well as Islamic

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or ''Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the main ...

mysticism, primarily because of the Quran's description of John's chastity and kindness. Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, ...

s have frequently applied commentaries on the passages on John in the Quran, primarily concerning the God-given gift of "Wisdom" which he acquired in youth as well as his parallels with Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

. Although several phrases used to describe John and Jesus are virtually identical in the Quran, the manner in which they are expressed is different.

Druze view

Druze tradition honors several "mentors" and "prophets", and John the Baptist is honored as a

Druze tradition honors several "mentors" and "prophets", and John the Baptist is honored as a prophet