Saartjie Baartman on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sarah Baartman (; 1789– 29 December 1815), also spelt Sara, sometimes in the diminutive form Saartje (), or Saartjie, and Bartman, Bartmann, was a  "Venus" is sometimes used to designate representations of the female body in arts and cultural anthropology, referring to the Roman goddess of love and fertility. " Hottentot" was the colonial-era term for the indigenous Khoikhoi people of southwestern Africa, now usually considered an offensive term. The Sarah Baartman story is often regarded as the epitome of racist colonial exploitation, and of the commodification of the

"Venus" is sometimes used to designate representations of the female body in arts and cultural anthropology, referring to the Roman goddess of love and fertility. " Hottentot" was the colonial-era term for the indigenous Khoikhoi people of southwestern Africa, now usually considered an offensive term. The Sarah Baartman story is often regarded as the epitome of racist colonial exploitation, and of the commodification of the

Hendrik Cesars and Alexander Dunlop brought Baartman to London in 1810. The group lived together in Duke Street, St. James, the most expensive part of London. In the household were Sarah Baartman, Hendrik Cesars, Alexander Dunlop, and two African boys, probably brought illegally by Dunlop from the slave lodge in Cape Town.

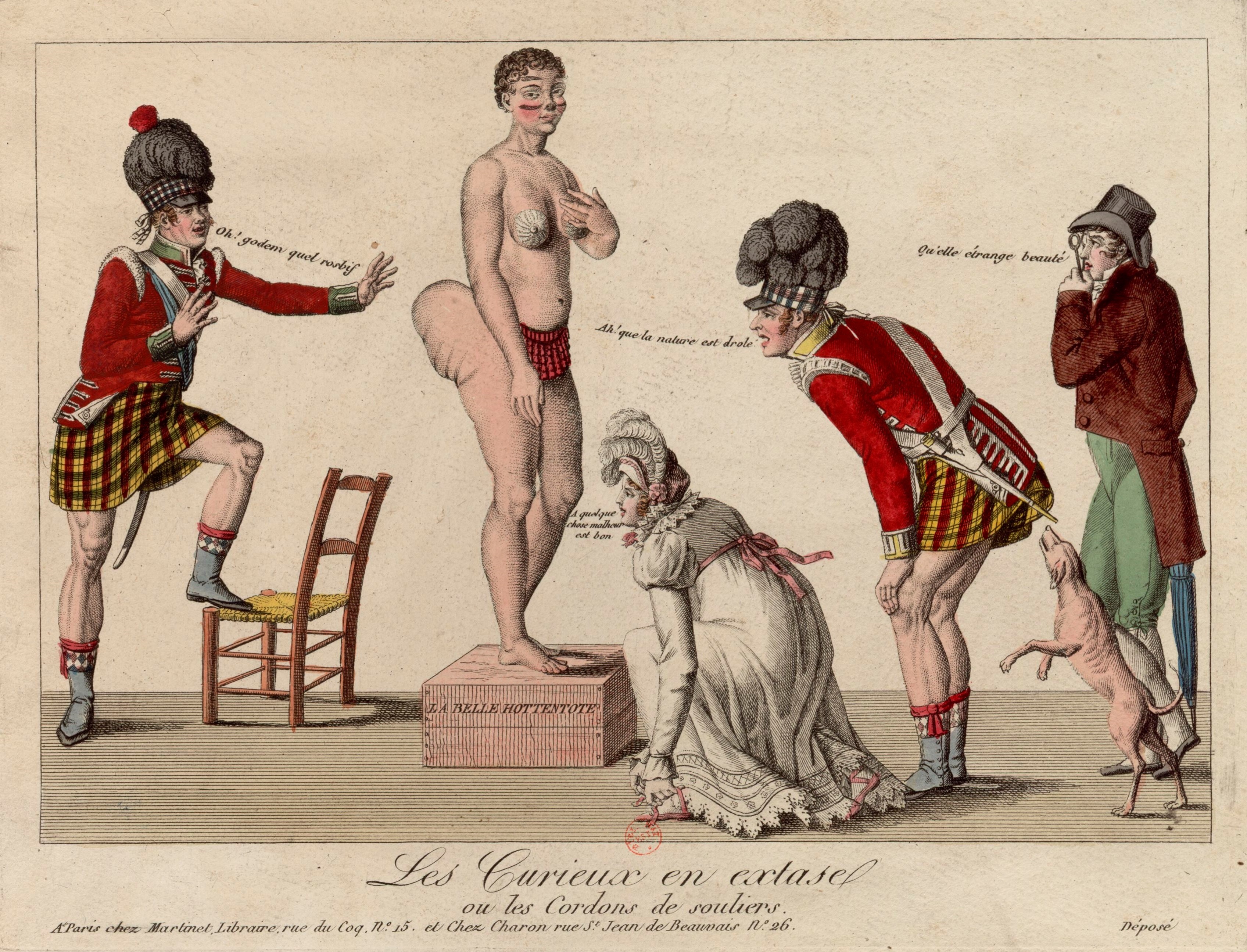

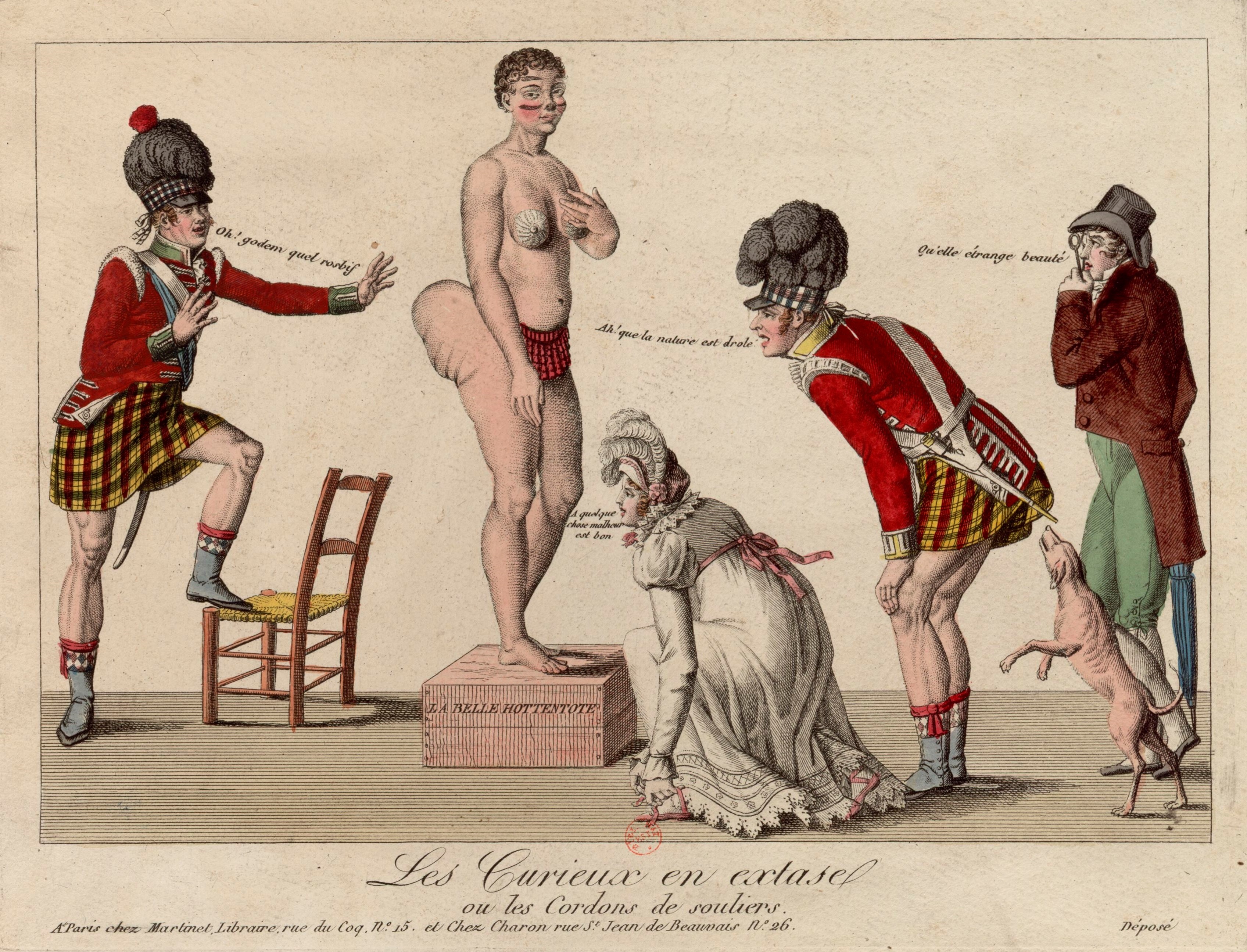

Dunlop had to have Baartman exhibited and Cesars was the showman. Dunlop exhibited Baartman at the Egyptian Room at the London residence of Thomas Hope at No. 10 Duchess Street, Cavendish Square, London. Dunlop thought he could make money because of Londoners' lack of familiarity with Africans and because of Baartman's pejoratively perceived large buttocks. Crais and Scully say: "People came to see her because they saw her not as a person but as a pure example of this one part of the natural world". She became known as the "Hottentot Venus" (as was at least one other woman, in 1829). A handwritten note made on an exhibition flyer by someone who saw Baartman in London in January 1811 indicates curiosity about her origins and probably reproduced some of the language from the exhibition; thus the following origin story should be treated with skepticism: "Sartjee is 22 Years old is 4 feet 10 Inches high, and has (for a Hottentot) a good capacity. She lived in the occupation of a Cook at the Cape of Good Hope. Her Country is situated not less than 600 Miles from the Cape, the Inhabitants of which are rich in Cattle and sell them by barter for a mere trifle. A Bottle of Brandy, or small roll of Tobacco will purchase several Sheep – Their principal trade is in Cattle Skins or Tallow. – Beyond this Nation is an other, of small stature, very subtle & fierce; the Dutch could not bring them under subjection, and shot them whenever they found them. 9 Jany, 1811. .C.? The tradition of freak shows was well established in Europe at this time, and historians have argued that this is at first how Baartman was displayed. Baartman never allowed herself to be exhibited nude,Strother, Z.S. (1999). "Display of the Body Hottentot", in Lindfors, B., (ed.), ''Africans on Stage: Studies in Ethnological Show Business''. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press: 1–55. and an account of her appearance in London in 1810 makes it clear that she was wearing a garment, albeit a tight-fitting one.''The Times'', 26 November 1810, p. 3: "...she is dressed in a colour as nearly resembling her skin as possible. The dress is contrived to exhibit the entire frame of her body, and the spectators are even invited to examine the peculiarities of her form." She became a subject of scientific interest, albeit of racist bias frequently, as well as of erotic projection. She was marketed as the "missing link between man and beast".

Her exhibition in London just a few years after the passing of the 1807 Slave Trade Act, which abolished the

Hendrik Cesars and Alexander Dunlop brought Baartman to London in 1810. The group lived together in Duke Street, St. James, the most expensive part of London. In the household were Sarah Baartman, Hendrik Cesars, Alexander Dunlop, and two African boys, probably brought illegally by Dunlop from the slave lodge in Cape Town.

Dunlop had to have Baartman exhibited and Cesars was the showman. Dunlop exhibited Baartman at the Egyptian Room at the London residence of Thomas Hope at No. 10 Duchess Street, Cavendish Square, London. Dunlop thought he could make money because of Londoners' lack of familiarity with Africans and because of Baartman's pejoratively perceived large buttocks. Crais and Scully say: "People came to see her because they saw her not as a person but as a pure example of this one part of the natural world". She became known as the "Hottentot Venus" (as was at least one other woman, in 1829). A handwritten note made on an exhibition flyer by someone who saw Baartman in London in January 1811 indicates curiosity about her origins and probably reproduced some of the language from the exhibition; thus the following origin story should be treated with skepticism: "Sartjee is 22 Years old is 4 feet 10 Inches high, and has (for a Hottentot) a good capacity. She lived in the occupation of a Cook at the Cape of Good Hope. Her Country is situated not less than 600 Miles from the Cape, the Inhabitants of which are rich in Cattle and sell them by barter for a mere trifle. A Bottle of Brandy, or small roll of Tobacco will purchase several Sheep – Their principal trade is in Cattle Skins or Tallow. – Beyond this Nation is an other, of small stature, very subtle & fierce; the Dutch could not bring them under subjection, and shot them whenever they found them. 9 Jany, 1811. .C.? The tradition of freak shows was well established in Europe at this time, and historians have argued that this is at first how Baartman was displayed. Baartman never allowed herself to be exhibited nude,Strother, Z.S. (1999). "Display of the Body Hottentot", in Lindfors, B., (ed.), ''Africans on Stage: Studies in Ethnological Show Business''. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press: 1–55. and an account of her appearance in London in 1810 makes it clear that she was wearing a garment, albeit a tight-fitting one.''The Times'', 26 November 1810, p. 3: "...she is dressed in a colour as nearly resembling her skin as possible. The dress is contrived to exhibit the entire frame of her body, and the spectators are even invited to examine the peculiarities of her form." She became a subject of scientific interest, albeit of racist bias frequently, as well as of erotic projection. She was marketed as the "missing link between man and beast".

Her exhibition in London just a few years after the passing of the 1807 Slave Trade Act, which abolished the

p. 351

Macaulay and The African Association took the matter to court and on 24 November 1810 at the Court of King's Bench the Attorney-General began the attempt "to give her liberty to say whether she was exhibited by her own consent." In support he produced two affidavits in court. The first, from a William Bullock of Liverpool Museum, was intended to show that Baartman had been brought to Britain by individuals who referred to her as if she were property. The second, by the Secretary of the African Association, described the degrading conditions under which she was exhibited and also gave evidence of coercion. Baartman was then questioned before an attorney in

"The Hottentot Venus."

'' The Flamingo's Smile''. New York: W. W. Norton

p. 298.

/ref> French naturalists, among them Georges Cuvier, head keeper of the menagerie at the

From the 1940s, there were sporadic calls for the return of her remains. A poem written in 1978 by South African poet Diana Ferrus, herself of Khoisan descent, entitled "I've come to take you home", played a pivotal role in spurring the movement to bring Baartman's remains back to her birth soil. The case gained world-wide prominence only after American paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould wrote ''

From the 1940s, there were sporadic calls for the return of her remains. A poem written in 1978 by South African poet Diana Ferrus, herself of Khoisan descent, entitled "I've come to take you home", played a pivotal role in spurring the movement to bring Baartman's remains back to her birth soil. The case gained world-wide prominence only after American paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould wrote ''

"Kim Kardashian: Posing Black Femaleness?"

''Clutch''. According to writer Geneva S. Thomas, anyone that is aware of black women's history under colonialist influence would consequentially be aware that Kardashian's photo easily elicits memory regarding the visual representation of Baartman. The photographer and director of the photo,

"The Troubling Racial History of Kim K's Champagne Shot"

''Refinery 29'', 13 November 2014. A ''People Magazine'' article in 1979 about his relationship with model Grace Jones describes Goude in the following statement:

"Kim Kardashian doesn't realize she's the butt of an old racial joke"

''The Grio'', 12 November 2014. In response to the November 2014 photograph of Kim Kardashian, Cleuci de Oliveira published an article on

1987 poem

and 1990 book, both entitled ''The Venus Hottentot''. * Hebrew poet Mordechai Geldman wrote a poem titled "THE HOTTENTOT VENUS" exploring the subject in his 1993 book Eye. * Suzan-Lori Parks used the story of Baartman as the basis for her 1996 play ''Venus.'' * Zola Maseko directed a documentary on Baartman, ''The Life and Times of Sarah Baartman'', in 1998. *

South Africa government site about her

including Diana Ferrus's pivotal poem

* [http://education.guardian.co.uk/higher/worldwide/story/0,,653760,00.html ''Guardian'' article on the return of her remains]

A documentary film called ''The Life and Times of Sara Baartman'' by Zola Maseko

The Saartjie Baartman Story

{{DEFAULTSORT:Baartman, Sarah 1770s births 1815 deaths Year of birth uncertain Art and cultural repatriation Khoikhoi People from the Eastern Cape Sideshow performers 18th-century South African people 19th-century South African women Ethnological show business South African emigrants to France South African expatriates in the United Kingdom Scientific racism

Khoikhoi

Khoekhoen (singular Khoekhoe) (or Khoikhoi in the former orthography; formerly also '' Hottentots''"Hottentot, n. and adj." ''OED Online'', Oxford University Press, March 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/88829. Accessed 13 May 2018. Citing G. S. ...

woman who was exhibited as a freak show

A freak show, also known as a creep show, is an exhibition of biological rarities, referred to in popular culture as "freaks of nature". Typical features would be physically unusual humans, such as those uncommonly large or small, those with ...

attraction in 19th-century Europe under the name Hottentot Venus, a name which was later attributed to at least one other woman similarly exhibited. The women were exhibited for their steatopygic body type uncommon in Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

which not only was perceived as a curiosity at that time, but became subject of scientific interest as well as of erotic projection. She is thought to have suffered from lipedema

Lipedema is a condition that is almost exclusively found in women and results in enlargement of both legs due to deposits of fat under the skin. Women of any weight may develop lipedema and the fat associated with lipedema is resistant to traditi ...

.

"Venus" is sometimes used to designate representations of the female body in arts and cultural anthropology, referring to the Roman goddess of love and fertility. " Hottentot" was the colonial-era term for the indigenous Khoikhoi people of southwestern Africa, now usually considered an offensive term. The Sarah Baartman story is often regarded as the epitome of racist colonial exploitation, and of the commodification of the

"Venus" is sometimes used to designate representations of the female body in arts and cultural anthropology, referring to the Roman goddess of love and fertility. " Hottentot" was the colonial-era term for the indigenous Khoikhoi people of southwestern Africa, now usually considered an offensive term. The Sarah Baartman story is often regarded as the epitome of racist colonial exploitation, and of the commodification of the dehumanization

Dehumanization is the denial of full humanness in others and the cruelty and suffering that accompanies it. A practical definition refers to it as the viewing and treatment of other persons as though they lack the mental capacities that are c ...

of black people.

Life

Early life in the Cape Colony

Baartman was born to aKhoekhoe

Khoekhoen (singular Khoekhoe) (or Khoikhoi in the former orthography; formerly also '' Hottentots''"Hottentot, n. and adj." ''OED Online'', Oxford University Press, March 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/88829. Accessed 13 May 2018. Citing G. S. ...

family in the vicinity of the Camdeboo in what is now the Eastern Cape of South Africa (then the Dutch Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie) was a Dutch United East India Company (VOC) colony in Southern Africa, centered on the Cape of Good Hope, from where it derived its name. The original colony and its successive states that the colony was inco ...

; a British colony by the time she was an adult). Saartjie is the diminutive form of Sarah; in Cape Dutch

Cape Dutch, also commonly known as Cape Afrikaners, were a historic socioeconomic class of Afrikaners who lived in the Western Cape during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The terms have been evoked to describe an affluent, apolitical se ...

the use of the diminutive form commonly indicated familiarity, endearment or contempt. Her birth name is unknown. Her surname has also been spelt Bartman and Bartmann. Her mother died when she was an infant and her father was later killed by Bushmen (San people) while driving cattle.

Baartman spent her childhood and teenage years on Dutch European

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

farms. She went through puberty rites, and kept the small tortoise shell necklace, most likely given to her by her mother, until her death in France. In the 1790s, a free black (a designation for individuals of enslaved descent) trader named Peter Cesars (also recorded as Caesar) met her and encouraged her to move to Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

. Records do not show whether she was made to leave, went willingly, or was sent by her family to Cesars. She lived in Cape Town for at least two years working in households as a washerwoman and a nursemaid, first for Peter Cesars, then in the house of a Dutch man in Cape Town. She finally moved to be a wet-nurse

A wet nurse is a woman who breastfeeds and cares for another's child. Wet nurses are employed if the mother dies, or if she is unable or chooses not to nurse the child herself. Wet-nursed children may be known as "milk-siblings", and in some cu ...

in the household of Peter Cesars' brother, Hendrik Cesars, outside of Cape Town in present day Woodstock

Woodstock Music and Art Fair, commonly referred to as Woodstock, was a music festival held during August 15–18, 1969, on Max Yasgur's dairy farm in Bethel, New York, United States, southwest of the town of Woodstock. Billed as "an Aq ...

. There is evidence that she had two children, though both died as babies. She had a relationship with a poor Dutch soldier, Hendrik van Jong, who lived in Hout Bay

Hout Bay ( af, Houtbaai, meaning "Wood Bay") is a harbour town in the Western Cape province of South Africa. It is situated in a valley on the Atlantic seaboard of the Cape Peninsula, twenty kilometres south of Cape Town. The name "Hout Bay" can ...

near Cape Town, but the relationship ended when his regiment left the Cape.

Hendrik Cesars began to show her at the city hospital in exchange for cash, where surgeon Alexander Dunlop worked. Dunlop, (sometimes wrongly cited as William Dunlop), a Scottish military surgeon in the Cape slave lodge, operated a side business in supplying showmen in Britain with animal specimens, and suggested she travel to Europe to make money by exhibiting herself. Baartman refused. Dunlop persisted, and Baartman said she would not go unless Hendrik Cesars came too. He also refused, but he finally agreed in 1810 to go to Britain to make money by putting Baartman on stage. The party left for London in 1810. It is unknown whether Baartman went willingly or was forced.

Dunlop was the frontman and conspirator behind the plan to exhibit Baartman. According to a British legal report of 26 November 1810, an affidavit supplied to the Court of King's Bench from a "Mr. Bullock of Liverpool Museum" stated: "some months since a Mr. Alexander Dunlop, who, he believed, was a surgeon in the army, came to him to sell the skin of a Camelopard

The giraffe is a large African hoofed mammal belonging to the genus ''Giraffa''. It is the tallest living terrestrial animal and the largest ruminant on Earth. Traditionally, giraffes were thought to be one species, ''Giraffa camelopardalis ...

, which he had brought from the Cape of Good Hope.... Some time after, Mr. Dunlop again called on Mr. Bullock, and told him, that he had then on her way from the Cape, a female Hottentot, of very singular appearance; that she would make the fortune of any person who shewed her in London, and that he (Dunlop) was under an engagement to send her back in two years..." Lord Caledon, governor of the Cape, gave permission for the trip, but later said regretted it after he fully learned the purpose of the trip.

On display in Europe

Hendrik Cesars and Alexander Dunlop brought Baartman to London in 1810. The group lived together in Duke Street, St. James, the most expensive part of London. In the household were Sarah Baartman, Hendrik Cesars, Alexander Dunlop, and two African boys, probably brought illegally by Dunlop from the slave lodge in Cape Town.

Dunlop had to have Baartman exhibited and Cesars was the showman. Dunlop exhibited Baartman at the Egyptian Room at the London residence of Thomas Hope at No. 10 Duchess Street, Cavendish Square, London. Dunlop thought he could make money because of Londoners' lack of familiarity with Africans and because of Baartman's pejoratively perceived large buttocks. Crais and Scully say: "People came to see her because they saw her not as a person but as a pure example of this one part of the natural world". She became known as the "Hottentot Venus" (as was at least one other woman, in 1829). A handwritten note made on an exhibition flyer by someone who saw Baartman in London in January 1811 indicates curiosity about her origins and probably reproduced some of the language from the exhibition; thus the following origin story should be treated with skepticism: "Sartjee is 22 Years old is 4 feet 10 Inches high, and has (for a Hottentot) a good capacity. She lived in the occupation of a Cook at the Cape of Good Hope. Her Country is situated not less than 600 Miles from the Cape, the Inhabitants of which are rich in Cattle and sell them by barter for a mere trifle. A Bottle of Brandy, or small roll of Tobacco will purchase several Sheep – Their principal trade is in Cattle Skins or Tallow. – Beyond this Nation is an other, of small stature, very subtle & fierce; the Dutch could not bring them under subjection, and shot them whenever they found them. 9 Jany, 1811. .C.? The tradition of freak shows was well established in Europe at this time, and historians have argued that this is at first how Baartman was displayed. Baartman never allowed herself to be exhibited nude,Strother, Z.S. (1999). "Display of the Body Hottentot", in Lindfors, B., (ed.), ''Africans on Stage: Studies in Ethnological Show Business''. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press: 1–55. and an account of her appearance in London in 1810 makes it clear that she was wearing a garment, albeit a tight-fitting one.''The Times'', 26 November 1810, p. 3: "...she is dressed in a colour as nearly resembling her skin as possible. The dress is contrived to exhibit the entire frame of her body, and the spectators are even invited to examine the peculiarities of her form." She became a subject of scientific interest, albeit of racist bias frequently, as well as of erotic projection. She was marketed as the "missing link between man and beast".

Her exhibition in London just a few years after the passing of the 1807 Slave Trade Act, which abolished the

Hendrik Cesars and Alexander Dunlop brought Baartman to London in 1810. The group lived together in Duke Street, St. James, the most expensive part of London. In the household were Sarah Baartman, Hendrik Cesars, Alexander Dunlop, and two African boys, probably brought illegally by Dunlop from the slave lodge in Cape Town.

Dunlop had to have Baartman exhibited and Cesars was the showman. Dunlop exhibited Baartman at the Egyptian Room at the London residence of Thomas Hope at No. 10 Duchess Street, Cavendish Square, London. Dunlop thought he could make money because of Londoners' lack of familiarity with Africans and because of Baartman's pejoratively perceived large buttocks. Crais and Scully say: "People came to see her because they saw her not as a person but as a pure example of this one part of the natural world". She became known as the "Hottentot Venus" (as was at least one other woman, in 1829). A handwritten note made on an exhibition flyer by someone who saw Baartman in London in January 1811 indicates curiosity about her origins and probably reproduced some of the language from the exhibition; thus the following origin story should be treated with skepticism: "Sartjee is 22 Years old is 4 feet 10 Inches high, and has (for a Hottentot) a good capacity. She lived in the occupation of a Cook at the Cape of Good Hope. Her Country is situated not less than 600 Miles from the Cape, the Inhabitants of which are rich in Cattle and sell them by barter for a mere trifle. A Bottle of Brandy, or small roll of Tobacco will purchase several Sheep – Their principal trade is in Cattle Skins or Tallow. – Beyond this Nation is an other, of small stature, very subtle & fierce; the Dutch could not bring them under subjection, and shot them whenever they found them. 9 Jany, 1811. .C.? The tradition of freak shows was well established in Europe at this time, and historians have argued that this is at first how Baartman was displayed. Baartman never allowed herself to be exhibited nude,Strother, Z.S. (1999). "Display of the Body Hottentot", in Lindfors, B., (ed.), ''Africans on Stage: Studies in Ethnological Show Business''. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press: 1–55. and an account of her appearance in London in 1810 makes it clear that she was wearing a garment, albeit a tight-fitting one.''The Times'', 26 November 1810, p. 3: "...she is dressed in a colour as nearly resembling her skin as possible. The dress is contrived to exhibit the entire frame of her body, and the spectators are even invited to examine the peculiarities of her form." She became a subject of scientific interest, albeit of racist bias frequently, as well as of erotic projection. She was marketed as the "missing link between man and beast".

Her exhibition in London just a few years after the passing of the 1807 Slave Trade Act, which abolished the slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, created a scandal. A British abolitionist society, the African Association

The Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa (commonly known as the African Association), founded in London on 9 June 1788, was a British club dedicated to the exploration of West Africa, with the mission of discove ...

, conducted a newspaper campaign for her release. The British abolitionist Zachary Macaulay

Zachary Macaulay ( gd, Sgàire MacAmhlaoibh; 2 May 1768 – 13 May 1838) was a Scottish statistician and abolitionist who was a founder of London University and of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, and a Governor of British Sierra Leone ...

led the protest, with Hendrik Cesars protesting in response that Baartman was entitled to earn her living, stating: "has she not as good a right to exhibit herself as an Irish Giant or a Dwarf?" Cesars was comparing Baartman to the contemporary Irish giants Charles Byrne and Patrick Cotter O'Brien.Lederman, Muriel and Ingrid Bartsch (2001). ''The Gender and Science Reader''. New York: Routledgep. 351

Macaulay and The African Association took the matter to court and on 24 November 1810 at the Court of King's Bench the Attorney-General began the attempt "to give her liberty to say whether she was exhibited by her own consent." In support he produced two affidavits in court. The first, from a William Bullock of Liverpool Museum, was intended to show that Baartman had been brought to Britain by individuals who referred to her as if she were property. The second, by the Secretary of the African Association, described the degrading conditions under which she was exhibited and also gave evidence of coercion. Baartman was then questioned before an attorney in

Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

, in which she was fluent, via interpreters.

Historians have subsequently stated doubts on the veracity and independence of the statement that Baartman then made. She stated that she in fact was not under restraint, had not been sexually abused and had come to London on her own free will. She also did not wish to return to her family and understood perfectly that she was guaranteed half of the profits. The case was therefore dismissed. She was questioned for three hours. The statements directly contradict accounts of her exhibitions made by Zachary Macaulay

Zachary Macaulay ( gd, Sgàire MacAmhlaoibh; 2 May 1768 – 13 May 1838) was a Scottish statistician and abolitionist who was a founder of London University and of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, and a Governor of British Sierra Leone ...

of the African Institution and other eyewitnesses. A written contract was produced, which is considered by some modern commentators to be a legal subterfuge.

The publicity given by the court case increased Baartman's popularity as an exhibit. She later toured other parts of England and was exhibited at a fair in Limerick, Ireland in 1812. She also was exhibited at a fair at Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk. On 1 December 1811 Baartman was baptised at Manchester Cathedral and there is evidence that she got married on the same day.

Later life

A man called Henry Taylor took Baartman to France around September 1814. Taylor then sold her to a man sometimes reported as an animal trainer, S. Réaux, but whose name was actually Jean Riaux and belonged to a ballet master who had been deported from the Cape Colony forseditious

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, establ ...

behaviour. Riaux exhibited her under more pressured conditions for 15 months at the Palais Royal

The Palais-Royal () is a former royal palace located in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France. The screened entrance court faces the Place du Palais-Royal, opposite the Louvre. Originally called the Palais-Cardinal, it was built for Cardinal R ...

in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

. In France she was in effect enslaved. In Paris, her exhibition became more clearly entangled with scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies ...

. French scientists were curious about whether she had the elongated labia

Elongated labia (also known as sinus pudoris or macronympha, and colloquially as khoikhoi apron or hottentot apron) is a feature of certain Khoikhoi and other African women who develop, whether naturally or through artificial stretching, relative ...

which earlier naturalists such as François Levaillant

François Levaillant (born Vaillant, later in life as Le Vaillant, ''"The Valiant"'') (6 August 1753 – 22 November 1824) was a French author, explorer, naturalist, zoological collector, and noted ornithologist. He described many new species of ...

had purportedly observed in Khoisan at the Cape.Biologist Stephen Jay Gould recounted Cuvier's monograph on Baartman's genitalia, "The labia minora

The labia minora (Latin for 'smaller lips', singular: ''labium minus'', 'smaller lip'), also known as the inner labia, inner lips, vaginal lips or nymphae are two flaps of skin on either side of the human vaginal opening in the vulva, situated b ...

, or inner lips, of the ordinary female genitalia are greatly enlarged in Khoi-San women, and may hang down three or four inches below the vulva

The vulva (plural: vulvas or vulvae; derived from Latin for wrapper or covering) consists of the external female sex organs. The vulva includes the mons pubis (or mons veneris), labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, vestibular bulbs, vulv ...

when women stand, thus giving the impression of a separate and enveloping curtain of skin."Gould, Stephen Jay (1985)"The Hottentot Venus."

'' The Flamingo's Smile''. New York: W. W. Norton

p. 298.

/ref> French naturalists, among them Georges Cuvier, head keeper of the menagerie at the

Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle

The French National Museum of Natural History, known in French as the ' (abbreviation MNHN), is the national natural history museum of France and a ' of higher education part of Sorbonne Universities. The main museum, with four galleries, is loc ...

and founder of the discipline of comparative anatomy, visited her. She was the subject of several scientific paintings at the Jardin du Roi, where she was examined in March 1815: as naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (15 April 177219 June 1844) was a French naturalist who established the principle of "unity of composition". He was a colleague of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and expanded and defended Lamarck's evolutionary theories ...

and Frédéric Cuvier

Georges-Frédéric Cuvier (28 June 1773 – 24 July 1838) was a French zoologist and paleontologist. He was the younger brother of noted naturalist and zoologist Georges Cuvier.

Career

Frederic was the head keeper of the menagerie at the Musé ...

, a younger brother of Georges, reported: "she was obliging enough to undress and to allow herself to be painted in the nude". This was not really true: Although by his standards she appeared to be naked, she wore a small apron-like garment which concealed her genitalia throughout these sessions, in accordance with her own cultural norms of modesty. She steadfastly refused to remove this even when offered money by one of the attending scientists.

She was brought out as an exhibit at wealthy people's parties and private salons. In Paris, Baartman's promoters did not need to concern themselves with slavery charges. Crais and Scully state: "By the time she got to Paris, her existence was really quite miserable and extraordinarily poor. Sara was literally treated like an animal. There is some evidence to suggest that at one point a collar was placed around her neck." At the end of her life she was a prostitute, and penniless.

Death and aftermath

Baartman died on 29 December 1815 around age 26, of an undetermined inflammatory ailment, possiblysmallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

, while other sources suggest she contracted syphilis, or pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

. Cuvier conducted a dissection but no autopsy to inquire into the reasons for Baartman's death.

The French anatomist Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville

Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville (; 12 September 1777 – 1 May 1850) was a French zoologist and anatomist.

Life

Blainville was born at Arques, near Dieppe. As a young man he went to Paris to study art, but ultimately devoted himself to natur ...

published notes on the dissection in 1816, which were republished by Georges Cuvier in the ''Memoires du Museum d'Histoire Naturelle'' in 1817. Cuvier, who had met Baartman, notes in his monograph that its subject was an intelligent woman with an excellent memory, particularly for faces. In addition to her native tongue, she spoke fluent Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

, passable English, and a smattering of French. He describes her shoulders and back as "graceful", arms "slender", hands and feet as "charming" and "pretty". He adds she was adept at playing the Jew's harp, could dance according to the traditions of her country, and had a lively personality. Despite this, Cuvier interpreted her remains, in accordance with his theories on racial evolution, as evidencing ape-like traits. He thought her small ears were similar to those of an orangutan

Orangutans are great apes native to the rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia. They are now found only in parts of Borneo and Sumatra, but during the Pleistocene they ranged throughout Southeast Asia and South China. Classified in the genu ...

and also compared her vivacity, when alive, to the quickness of a monkey. He was part of a movement of scientists who were aiming to codify a hierarchy of races with the white man at the top.

Display of remains

Saint-Hilaire applied on behalf of the Muséum d' Histoire Naturelle to retain her remains (Cuvier had preserved her brain, genitalia and skeleton), on the grounds that it was of a singular specimen of humanity and therefore of special scientific interest. The application was approved and Baartman's skeleton and body cast were displayed in Muséum d'histoire naturelle d’Angers. Her skull was stolen in 1827 but returned a few months later. The restored skeleton and skull continued to arouse the interest of visitors until the remains were moved to theMusée de l'Homme

The Musée de l'Homme (French, "Museum of Mankind" or "Museum of Humanity") is an anthropology museum in Paris, France. It was established in 1937 by Paul Rivet for the 1937 ''Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne ...

, when it was founded in 1937, and continued up until the late 1970s. Her body cast and skeleton stood side by side and faced away from the viewer which emphasised her steatopygia (accumulation of fat on the buttocks) while reinforcing that aspect as the primary interest of her body. The Baartman exhibit proved popular until it elicited complaints for being a degrading representation of women. The skeleton was removed in 1974, and the body cast in 1976.

From the 1940s, there were sporadic calls for the return of her remains. A poem written in 1978 by South African poet Diana Ferrus, herself of Khoisan descent, entitled "I've come to take you home", played a pivotal role in spurring the movement to bring Baartman's remains back to her birth soil. The case gained world-wide prominence only after American paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould wrote ''

From the 1940s, there were sporadic calls for the return of her remains. A poem written in 1978 by South African poet Diana Ferrus, herself of Khoisan descent, entitled "I've come to take you home", played a pivotal role in spurring the movement to bring Baartman's remains back to her birth soil. The case gained world-wide prominence only after American paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould wrote ''The Mismeasure of Man

''The Mismeasure of Man'' is a 1981 book by paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould. The book is both a History of science, history and critique of the statistical methods and cultural motivations underlying biological determinism, the belief that "the s ...

'' in the 1980s. Mansell Upham, a researcher and jurist specializing in colonial South African history, also helped spur the movement to bring Baartman's remains back to South Africa. After the victory of the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a social-democratic political party in South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when the first post-apartheid election install ...

(ANC) in the 1994 South African general election

General elections were held in South Africa between 26 and 29 April 1994. The elections were the first in which citizens of all races were allowed to take part, and were therefore also the first held with universal suffrage. The election was c ...

, President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Nelson Mandela formally requested that France return the remains. After much legal wrangling and debates in the French National Assembly, France acceded to the request on 6 March 2002. Her remains were repatriated

Repatriation is the process of returning a thing or a person to its country of origin or citizenship. The term may refer to non-human entities, such as converting a foreign currency into the currency of one's own country, as well as to the pro ...

to her homeland, the Gamtoos Valley, on 6 May 2002, and they were buried on 9 August 2002 on ''Vergaderingskop'', a hill in the town of Hankey

Hankey is a small town on the confluence of the Klein and Gamtoos rivers in South Africa. It is part of the Kouga Local Municipality of the Sarah Baartman District in the Eastern Cape.

History

Hankey was established in 1826 and is the ...

over 200 years after her birth.

Baartman became an icon in South Africa as representative of many aspects of the nation's history. The Saartjie Baartman Centre for Women and Children, a refuge for survivors of domestic violence, opened in Cape Town in 1999. South Africa's first offshore environmental protection vessel, the ''Sarah Baartman

Sarah Baartman (; 1789– 29 December 1815), also spelt Sara, sometimes in the diminutive form Saartje (), or Saartjie, and Bartman, Bartmann, was a Khoikhoi woman who was exhibited as a freak show attraction in 19th-century Europe under the ...

'', is also named after her.

On 8 December 2018, the University of Cape Town

The University of Cape Town (UCT) ( af, Universiteit van Kaapstad, xh, Yunibesithi ya yaseKapa) is a public research university in Cape Town, South Africa. Established in 1829 as the South African College, it was granted full university statu ...

made the decision to rename Memorial Hall, at the centre of the campus, to Sarah Baartman Hall. This follows the earlier removal of " Jameson" from the former name of the hall.

Symbolism

Sarah Baartman was not the only Khoikhoi to be taken from her homeland. Her story is sometimes used to illustrate social and political strains, and through this, some facts have been lost. Dr.Yvette Abrahams

Yvette Abrahams is an organic farmer, activist and feminist scholar in South Africa.

Life

Yvette Abrahams was born in Cape Town in the early 1960s, the daughter of Namibian activists Ottilie Abrahams and Kenneth Abrahams. She grew up in exile i ...

, professor of women and gender studies at the University of the Western Cape

The University of the Western Cape (UWC) is a public research university in Bellville, near Cape Town, South Africa. The university was established in 1959 by the South African government as a university for Coloured people only. Other un ...

, writes, "we lack academic studies that view Sarah Baartman as anything other than a symbol. Her story becomes marginalized, as it is always used to illustrate some other topic." Baartman is used to represent African discrimination and suffering in the West although there were many other Khoikhoi people who were taken to Europe. Historian Neil Parsons writes of two Khoikhoi children 13 and six years old respectively, who were taken from South Africa and displayed at a holiday fair in Elberfeld

Elberfeld is a municipal subdivision of the German city of Wuppertal; it was an independent town until 1929.

History

The first official mentioning of the geographic area on the banks of today's Wupper River as "''elverfelde''" was in a doc ...

, Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

, in 1845. ''Bosjemans'', a travelling show including two Khoikhoi men, women, and a baby, toured Britain, Ireland, and France from 1846 to 1855. P. T. Barnum's show "Little People" advertised a 16-year-old Khoikhoi girl named Flora as the "missing link" and acquired six more Khoikhoi children later.

Baartman's tale may be better known because she was the first Khoikhoi taken from her homeland, or because of the extensive exploitation and examination of her body by scientists such as Georges Cuvier, an anatomist, and the public as well as the mistreatment she received during and after her lifetime. She was brought to the West for her "exaggerated" female form, and the European public developed an obsession with her reproductive organs. Her body parts were on display at the Musée de l'Homme

The Musée de l'Homme (French, "Museum of Mankind" or "Museum of Humanity") is an anthropology museum in Paris, France. It was established in 1937 by Paul Rivet for the 1937 ''Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne ...

for 150 years, sparking awareness and sympathy in the public eye. Although Baartman was the first Khoikhoi to land in Europe, much of her story has been lost, and she is defined by her exploitation in the West.

Her body as a foundation for science

Julien-Joseph Virey

Julien-Joseph Virey (21 December 1775, Langres – 9 March 1846) was a French naturalist and anthropologist.

Biography

Julien-Joseph Virey grew up in Hortes village in southern Haute-Marne, where he had access to a library. He educated himself a ...

used Sarah Baartman's published image to validate typologies. In his essay "Dictionnaire des sciences medicales" (Dictionary of medical sciences), he summarizes the true nature of the black female within the framework of accepted medical discourse. Virey focused on identifying her sexual organs as more developed and distinct in comparison to white female organs. All of his theories regarding sexual primitivism are influenced and supported by the anatomical studies and illustrations of Sarah Baartman which were created by Georges Cuvier.

It has been suggested by anthropologists that this body type was once more widespread in humans, based on carvings of female forms dating to the Paleolithic era which are collectively known as Venus figurines

A Venus figurine is any Upper Palaeolithic statuette portraying a woman, usually carved in the round.Fagan, Brian M., Beck, Charlotte, "Venus Figurines", ''The Oxford Companion to Archaeology'', 1996, Oxford University Press, pp. 740–741 Most ...

, also referred to as Steatopygian Venuses.

Sexism

From 1814 to 1870, there were at least seven scientific descriptions of the bodies of black women done in comparative anatomy. Cuvier's dissection of Baartman helped shape European science. Baartman, along with several other African women who were dissected, were referred to as Hottentots, or sometimes Bushwoman. The "savage woman" was seen as very distinct from the "civilised female" of Europe, thus 19th-century scientists were fascinated by "the Hottentot Venus". In the 1800s, people in London were able to pay two shillings apiece to gaze upon her body. Baartman was considered a freak of nature. For extra pay, one could even poke her with a stick or finger.Colonialism

There has been much speculation and study about colonialist influence that relates to Baartman's name, social status, her illustrated and performed presentation as the "Hottentot Venus" though considered an extremely offensive term, and the negotiation for her body's return to her homeland. These components and events in Baartman's life have been used by activists and theorists to determine the ways in which 19th-century European colonists exercised control and authority over Khoikhoi people and simultaneously crafted racist and sexist ideologies about their culture. In addition to this, recent scholars have begun to analyze the surrounding events leading up to Baartman's return to her homeland and conclude that it is an expression of recent contemporary post colonial objectives. In Janet Shibamoto's book review of Deborah Cameron's book ''Feminism and Linguistic Theory'', Shibamoto discusses Cameron's study on the patriarchal context within language, which consequentially influences the way in which women continue to be contained by or subject to ideologies created by the patriarchy. Many scholars have presented information on how Baartman's life was heavily controlled and manipulated by colonialist and patriarchal language. Baartman grew up on a farm. There is no historical documentation of her indigenous Khoisan name. She was given the Dutch name "Saartjie" by Dutch colonists who occupied the land she lived on during her childhood. According to Clifton Crais and Pamela Scully:Her first name is the Cape Dutch form for "Sarah" which marked her as a colonialist's servant. "Saartje" the diminutive, was also a sign of affection. Encoded in her first name were the tensions of affection and exploitation. Her surname literally means "bearded man" in Dutch. It also means uncivilized, uncouth, barbarous, savage. Saartjie Baartman – the savage servant.Dutch colonisers also bestowed the term "Hottentot", which is derived from "hot" and "tot", Dutch approximations of common sounds in the Khoi language. The Dutch used this word when referencing Khoikhoi people because of the clicking sounds and staccato pronunciations that characterise the Khoikhoi language; these components of the Khoikhoi language were considered strange and "bestial" to Dutch colonisers. The term was used until the late 20th century, at which point most people understood its effect as a derogatory term. Travelogues that circulated in Europe would describe Africa as being "uncivilised" and lacking regard for religious virtue. Travelogues and imagery depicting Black women as "sexually primitive" and "savage" enforced the belief that it was in Africa's best interest to be colonised by European settlers. Cultural and religious conversion was considered to be an altruistic act with imperialist undertones; colonisers believed that they were reforming and correcting Khoisan culture in the name of the Christian faith and empire. Scholarly arguments discuss how Baartman's body became a symbolic depiction of "all African women" as "fierce, savage, naked, and untamable" and became a crucial role in colonising parts of Africa and shaping narratives. During the lengthy negotiation to have Baartman's body returned to her home country after her death, the assistant curator of the Musée de l'Homme, Philippe Mennecier, argued against her return, stating: "We never know what science will be able to tell us in the future. If she is buried, this chance will be lost ... for us she remains a very important treasure." According to Sadiah Qureshi, due to the continued treatment of Baartman's body as a cultural artifact, Philippe Mennecier's statement is contemporary evidence of the same type of ideology that surrounded Baartman's body while she was alive in the 18th century.

Feminist reception

Traditional iconography of Sarah Baartman and feminist contemporary art

Many African female diasporic artists have criticised the traditional iconography of Baartman. According to the studies of contemporary feminists, traditional iconography and historical illustrations of Baartman are effective in revealing the ideological representation of black women in art throughout history. Such studies assess how the traditional iconography of the black female body was institutionally and scientifically defined in the 19th century. Renee Cox,Renée Green

Renée Green (born October 25, 1959) is an American artist, writer, and filmmaker. Her pluralistic practice spans a broad range of media including sculpture, architecture, photography, prints, video, film, websites, and sound, which normally conv ...

, Joyce Scott, Lorna Simpson, Cara Mae Weems and Deborah Willis are artists who seek to investigate contemporary social and cultural issues that still surround the African female body. Sander Gilman

Sander L. Gilman, born on February 21, 1944, is an American cultural and literary historian. He is known for his contributions to Jewish studies and the history of medicine. He is the author or editor of over ninety books.

Gilman's focus is on m ...

, a cultural and literary historian states: "While many groups of African Blacks were known to Europeans in the 19th century, the Hottentot remained representative of the essence of the Black, especially the Black female. Both concepts fulfilled the iconographic function in the perception and representation of the world."

His article "Black Bodies, White Bodies: Toward an Iconography of Female Sexuality in the Late Nineteenth Century Art, Medicine and Literature" traces art historical records of black women in European art, and also proves that the association of black women with concupiscence within art history has been illustrated consistently since the beginning of the Middle Ages.

Lyle Ashton Harris

Lyle Ashton Harris (born February 6, 1965) is an American artist who has cultivated a diverse artistic practice ranging from photographic media, collage, installation art and performance art. Harris uses his works to comment on societal constructs ...

and Renee Valerie Cox worked in collaboration to produce the photographic piece Hottentot Venus 2000. In this piece, Harris photographs Victoria Cox who presents herself as Baartman while wearing large, sculptural, gilded metal breasts and buttocks attached to her body.Willis, Deborah. "Black Venus 2010: They called her 'Hottentot.'" Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2010. Project Muse

"Permitted" is an installation piece created by Renée Green inspired by Sarah Baartman. Green created a specific viewing arrangement to investigate the European perception of the black female body as "exotic", "bizarre" and "monstrous". Viewers were prompted to step onto the installed platform which was meant to evoke a stage, where Baartman may have been exhibited. Green recreates the basic setting of Baartman's exhibition. At the centre of the platform, which there is a large image of Baartman, and wooden rulers or slats with an engraved caption by Francis Galton encouraging viewers to measure Baartman's buttocks. In the installation there is also a peephole that allows viewers to see an image of Baartman standing on a crate. According to Willis, the implication of the peephole, demonstrates how ethnographic imagery of the black female form in the 19th century functioned as a form of pornography for Europeans present at Baartmans exhibit.

In her film ''Reassemblage: From the firelight to the screen'', Trinh T. Minh-ha comments on the ethnocentric bias that the colonisers eye applies to the naked female form, arguing that this bias causes the nude female body to be seen as inherently sexually provocative, promiscuous and pornographic within the context of European or western culture.

Feminist artists are interested in re-representing Baartman's image, and work to highlight the stereotypes and ethnocentric bias surrounding the black female body based on art historical representations and iconography that occurred before, after and during Baartman's lifetime.

Media representation and feminist criticism

In November 2014, ''Paper Magazine

''Paper'' (also known as ''Paper Mag'') is a New York City-based independent magazine focusing on fashion, popular culture, nightlife, music, art, and film. Initially produced monthly, the magazine eventually became a quarterly publication, and a ...

'' released a cover of Kim Kardashian

Kimberly Noel Kardashian (formerly West; born October 21, 1980) is an American socialite, media personality, and businesswoman. She first gained media attention as a friend and stylist of Paris Hilton, but received wider notice after the s ...

in which she was illustrated as balancing a champagne glass on her extended rear. The cover received much criticism for endorsing "the exploitation and fetishism of the black female body". The similarities with the way in which Baartman was represented as the "Hottentot Venus" during the 19th century have prompted much criticism and commentary.Thomas, Geneva"Kim Kardashian: Posing Black Femaleness?"

''Clutch''. According to writer Geneva S. Thomas, anyone that is aware of black women's history under colonialist influence would consequentially be aware that Kardashian's photo easily elicits memory regarding the visual representation of Baartman. The photographer and director of the photo,

Jean-Paul Goude

Jean-Paul Goude (born 8 December 1938 in Montreuil (France)) is a French graphic designer, illustrator, photographer, advertising film director and event designer. He worked as art director at ''Esquire'' magazine in New York City during the 1 ...

, based the photo on his previous work "Carolina Beaumont", taken of a nude model in 1976 and published in his book ''Jungle Fever''.Miller, Kelsey"The Troubling Racial History of Kim K's Champagne Shot"

''Refinery 29'', 13 November 2014. A ''People Magazine'' article in 1979 about his relationship with model Grace Jones describes Goude in the following statement:

Jean-Paul has been fascinated with women like Grace since his youth. The son of a French engineer and an American-born dancer, he grew up in a Paris suburb. From the moment he saw West Side Story and the Alvin Ailey dance troupe, he found himself captivated by "ethnic minorities" — black girls, PRs. "I had jungle fever." He now says, "Blacks are the premise of my work."Days before the shoot, Goude often worked with his models to find the best "hyperbolised" position to take his photos. His model and partner, Grace Jones, would also pose for days prior to finally acquiring the perfect form. "That's the basis of my entire work," Goude states, "creating a credible illusion." Similarly, Baartman and other black female slaves were illustrated and depicted in a specific form to identify features, which were seen as proof of ideologies regarding black female primitivism. The professional background of Goude and the specific posture and presentation of Kardashian's image in the recreation on the cover of ''Paper Magazine'' has caused feminist critics to comment how the objectification of the Baartman's body and the ethnographic representation of her image in 19th-century society presents a comparable and complementary parallel to how Kardashian is currently represented in the media.Telusma, Blue

"Kim Kardashian doesn't realize she's the butt of an old racial joke"

''The Grio'', 12 November 2014. In response to the November 2014 photograph of Kim Kardashian, Cleuci de Oliveira published an article on

Jezebel

Jezebel (;"Jezebel"

(US) and ) was the daughte ...

titled "Saartjie Baartman: The Original Bootie Queen", which claims that Baartman was "always an agent in her own path." Oliveira goes on to assert that Baartman performed on her own terms and was unwilling to view herself as a tool for scientific advancement, an object of entertainment, or a pawn of the state.

Neelika Jayawardane, a literature professor and editor of the website Africa is a Country, published a response to Oliveira's article. Jayawardane criticises de Oliveira's work, stating that she "did untold damage to what the historical record shows about Baartman". Jayawardane's article is cautious about introducing what she considers false agency to historical figures such as Baartman.

An article entitled "Body Talk: Feminism, Sexuality and the Body in the Work of Six African Women Artists", curated by Cameroonian-born Koyo Kouoh", which mentions Baartman's legacy and its impact on young female African artists. The work linked to Baartman is meant to reference the ethnographic exhibits of the 19th century that enslaved Baartman and displayed her naked body. Artist Valérie Oka's (''Untitled'', 2015) rendered a live performance of a black naked woman in a cage with the door swung open, walking around a sculpture of male genitalia, repeatedly. Her work was so impactful it led one audience member to proclaim, "Do we allow this to happen because we are in the white cube, or are we revolted by it?". Oka's work has been described as 'black feminist art' where the female body is a site for activism and expression. The article also mentions other African female icons and how artists are expressing themselves through performance and discussion by posing the question "How Does the White Man Represent the Black Woman?".

Social scientists James McKay and Helen Johnson cited Baartman to fit newspaper coverage of the (US) and ) was the daughte ...

African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

tennis players Venus Williams, Venus and Serena Williams within racist trans-historical narratives of "pornographic eroticism" and "sexual grotesquerie." According to McKay and Johnson, white male reporters covering the Williams sisters have fixated upon their on-court fashions and their muscular bodies, while downplaying their on-court achievements, describing their bodies as mannish, animalistic, or hyper-sexual, rather than well-developed. Their victories have been attributed to their supposed natural physical superiorities, while their defeats have been blamed on their supposed lack of discipline. This analysis claims that commentary on the size of Serena's breasts and bottom, in particular, mirrors the spectacle made of Baartman's body.

Reclaiming the story

In recent years, some black women have found her story to be a source of empowerment, one that protests the ideals of white mainstream beauty, as curvaceous bodies are increasingly lauded in popular culture and mass media. Paramount Chief Glen Taaibosch, chair of the Gauteng Khoi and San Council, says that today "we call her our Hottentot Queen" and honour her.Cultural references

* On 10 January 1811, at the New London Theatre, New Theatre, London, a pantomime called "The Hottentot Venus" featured at the end of the evening's entertainment. * In William Makepeace Thackeray's 1847 novel ''Vanity Fair (novel), Vanity Fair'', George Osborne angrily refuses his father's instruction to marry a West Indian mulatto heiress by referring to Miss Swartz as "that Hottentot Venus". * In "Crinoliniana" (1863), a poem satirising Victorian fashion, the author compares a woman in a crinoline to a "Venus" from "the Cape". * In James Joyce's 1916 novel ''A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man'', the protagonist, Stephen Dedalus, refers to "the great flanks of Venus" after a reference to the Hottentot people, when discussing the discrepancies between cultural perceptions of female beauty. * Dame Edith Sitwell referred to her allusively in "Hornpipe", a poem in the satirical collection ''Façade''. * In Jean Rhys' 1934 novel ''Voyage in the Dark'', the Creole protagonist Anna Morgan is referred to as "the Hottentot". * Elizabeth Alexander (poet), Elizabeth Alexander explores her story in1987 poem

and 1990 book, both entitled ''The Venus Hottentot''. * Hebrew poet Mordechai Geldman wrote a poem titled "THE HOTTENTOT VENUS" exploring the subject in his 1993 book Eye. * Suzan-Lori Parks used the story of Baartman as the basis for her 1996 play ''Venus.'' * Zola Maseko directed a documentary on Baartman, ''The Life and Times of Sarah Baartman'', in 1998. *

Lyle Ashton Harris

Lyle Ashton Harris (born February 6, 1965) is an American artist who has cultivated a diverse artistic practice ranging from photographic media, collage, installation art and performance art. Harris uses his works to comment on societal constructs ...

collaborated with the model Renee Valerie Cox to produce a photographic image, ''Hottentot Venus 2000''.

* Barbara Chase-Riboud wrote the novel ''Hottentot Venus: A Novel'' (2003), which humanizes Sarah Baartman

* Cathy Park Hong wrote a poem entitled "Hottentot Venus" in her 2007 book ''Translating Mo'um.''

* Lydia R. Diamond's 2008 play ''Voyeurs de Venus'' investigates Baartman's life from a postcolonial perspective.

* A movie entitled ''Black Venus (2010 film), Black Venus'', directed by Abdellatif Kechiche and starring Yahima Torres as Sarah, was released in 2010.

* Hendrik Hofmeyr composed a 20-minute opera entitled ''Saartjie'', which was to be premiered by Cape Town Opera in November 2010.

* Joanna Bator refers to a fictional descendant in her novel:

* Douglas Kearney published a poem titled "Drop It Like It's Hottentot Venus" in April 2012.

* Diane Awerbuck has Baartman feature as a central thread in her novel ''Home Remedies''. The work is critical of the "grandstanding" that so often surrounds Baartman: as Awerbuck has explained, "Saartjie Baartman is not a symbol. She is a dead woman who once suffered in a series of cruel systems. The best way we can remember her is by not letting it happen again."

*Brett Bailey's ''Exhibit B'' (a human zoo) depicts Baartman.

*Jamila Woods' song "Blk Girl Soldier" on her 2016 album ''Heavn'' references Baartman's story: "They put her body in a jar and forget her".

*Nitty Scott makes reference to Baartman in her song "For Sarah Baartman" on her 2017 album ''CREATURE!''.

*The Carters, Jay-Z and Beyoncé, make mention of her in their song "Black Effect": "Stunt with your curls, your lips, Sarah Baartman hips", off their 2018 album ''Everything is Love''.

*University of Cape Town

The University of Cape Town (UCT) ( af, Universiteit van Kaapstad, xh, Yunibesithi ya yaseKapa) is a public research university in Cape Town, South Africa. Established in 1829 as the South African College, it was granted full university statu ...

, made the historic decision to rename Memorial Hall to Sarah Baartman Hall (8 December 2018).

*Zodwa Nyoni debuted at Summerhall in 2019, a new play called ''A Khoisan Woman'' - a play about the Hottentot Venus.

*Royce da 5'9", Royce 5'9 references Sarah Baartman in his song "Upside Down" in 2020.

*Tessa McWatt discusses Baartman and the Hottentot in her 2019/20 book, "Shame on Me: An Anatomy of Race and Belonging".

See also

* Awoulaba * Body shape * Female body shape * Feminine beauty ideal * Feminism and racism * Human variability * Human zoo * Ota Benga * Racial fetishism * Racism in Europe * Scientific racism * Tono MariaReferences

Bibliography

* * * * * *Willis, Deborah (Ed.) ''Black Venus 2010: They Called Her 'Hottentot'.'' Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. .Further reading

* Fausto-Sterling, Anne (1995). "Gender, Race, and Nation: The Comparative Anatomy of 'Hottentot' Women in Europe, 1815–1817". In Terry, Jennifer and Jacqueline Urla (Ed.) ''Deviant Bodies: Critical Perspectives on Difference in Science and Popular Culture'', 19–48. Bloomington, Indiana University Press. . * * * * Ritter, Sabine (2010). ''Facetten der Sarah Baartman: Repräsentationen und Rekonstruktionen der ‚Hottentottenvenus. Münster: Lit Verlag. .Films

* Abdellatif Kechiche: ''Vénus noire (Black Venus)''. Paris: MK2, 2009 * Zola Maseko: ''The life and times of Sara Baartman''. Icarus, 1998External links

*South Africa government site about her

including Diana Ferrus's pivotal poem

* [http://education.guardian.co.uk/higher/worldwide/story/0,,653760,00.html ''Guardian'' article on the return of her remains]

A documentary film called ''The Life and Times of Sara Baartman'' by Zola Maseko

The Saartjie Baartman Story

{{DEFAULTSORT:Baartman, Sarah 1770s births 1815 deaths Year of birth uncertain Art and cultural repatriation Khoikhoi People from the Eastern Cape Sideshow performers 18th-century South African people 19th-century South African women Ethnological show business South African emigrants to France South African expatriates in the United Kingdom Scientific racism