ss great britain on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SS ''Great Britain'' is a museum ship and former passenger steamship that was advanced for her time. She was the largest passenger ship in the world from 1845 to 1854. She was designed by

After the initial success of its first liner, of 1838, the

After the initial success of its first liner, of 1838, the

''Great Britain''s builders recognised a number of advantages of iron over the traditional wooden hull. Wood was becoming more expensive, while iron was getting cheaper. Iron hulls were not subject to

''Great Britain''s builders recognised a number of advantages of iron over the traditional wooden hull. Wood was becoming more expensive, while iron was getting cheaper. Iron hulls were not subject to

In early 1840, a second chance encounter occurred, the arrival of the revolutionary at Bristol, the first screw-propelled steamship, completed only a few months before by

In early 1840, a second chance encounter occurred, the arrival of the revolutionary at Bristol, the first screw-propelled steamship, completed only a few months before by

The launching or, more accurately, the

The launching or, more accurately, the  Introductions were made, followed by the "Address to His Royal Highness the Prince Albert", by the town clerk, D. Burgess. Honours were then bestowed on him by the Society of Merchant Venturers, and there were speeches from members of the Bristol clergy. The royal party then had breakfast and, after 20 minutes, reappeared to board horse-drawn carriages.

At noon, the Prince arrived at the Great Western Steamship yard only to find the ship already "launched" and waiting for royal inspection. He boarded the ship, took refreshments in the elegantly decorated lounge then commenced his tour of inspection. He was received in the ship's banqueting room where all the local dignitaries and their ladies were gathered.

After the banquet and the toasts, he left for the naming ceremony. It had already been decided that the christening would be performed by Clarissa (1790–1868), wife of Philip John Miles (1773–1845) and mother of Bristol's MP, Philip William Skinner Miles (1816–1881), a director of the company. She stepped forward, grasped the champagne bottle and swung it towards the bows. Unfortunately, the steam packet ''Avon'' had started to tow the ship into the harbour and the bottle fell about short of its target and dropped unbroken into the water. A second bottle was rapidly obtained and the Prince hurled it against the iron hull.

In her haste, ''Avon'' had started her work before the shore warps had been released. The tow rope snapped and, due to the resultant delay, the Prince was obliged to return to the railway station and miss the end of the programme.

Introductions were made, followed by the "Address to His Royal Highness the Prince Albert", by the town clerk, D. Burgess. Honours were then bestowed on him by the Society of Merchant Venturers, and there were speeches from members of the Bristol clergy. The royal party then had breakfast and, after 20 minutes, reappeared to board horse-drawn carriages.

At noon, the Prince arrived at the Great Western Steamship yard only to find the ship already "launched" and waiting for royal inspection. He boarded the ship, took refreshments in the elegantly decorated lounge then commenced his tour of inspection. He was received in the ship's banqueting room where all the local dignitaries and their ladies were gathered.

After the banquet and the toasts, he left for the naming ceremony. It had already been decided that the christening would be performed by Clarissa (1790–1868), wife of Philip John Miles (1773–1845) and mother of Bristol's MP, Philip William Skinner Miles (1816–1881), a director of the company. She stepped forward, grasped the champagne bottle and swung it towards the bows. Unfortunately, the steam packet ''Avon'' had started to tow the ship into the harbour and the bottle fell about short of its target and dropped unbroken into the water. A second bottle was rapidly obtained and the Prince hurled it against the iron hull.

In her haste, ''Avon'' had started her work before the shore warps had been released. The tow rope snapped and, due to the resultant delay, the Prince was obliged to return to the railway station and miss the end of the programme.

Following the launch ceremony, the builders had planned to have ''Great Britain'' towed to the

Following the launch ceremony, the builders had planned to have ''Great Britain'' towed to the

When completed in 1845, ''Great Britain'' was a revolutionary vessel—the first ship to combine an iron hull with screw propulsion, and at in length and with a 3,400-ton displacement, more than longer and 1,000 tons larger than any ship previously built. Her beam was and her height from keel to main deck, . She had four decks, including the spar (upper) deck, a crew of 120, and was fitted to accommodate a total of 360 passengers, along with 1,200 tons of cargo and 1,200 tons of

When completed in 1845, ''Great Britain'' was a revolutionary vessel—the first ship to combine an iron hull with screw propulsion, and at in length and with a 3,400-ton displacement, more than longer and 1,000 tons larger than any ship previously built. Her beam was and her height from keel to main deck, . She had four decks, including the spar (upper) deck, a crew of 120, and was fitted to accommodate a total of 360 passengers, along with 1,200 tons of cargo and 1,200 tons of

Two giant propeller engines, with a combined weight of 340 tons, were installed amidships. They were built to a modified patent of Brunel's father

Two giant propeller engines, with a combined weight of 340 tons, were installed amidships. They were built to a modified patent of Brunel's father

The interior was divided into three decks, the upper two for passengers and the lower for cargo. The two passenger decks were divided into forward and aft compartments, separated by the engines and boiler amidships.

In the after section of the ship, the upper passenger deck contained the after or principal saloon, long by wide, which ran from just aft of the engine room to the stern. On each side of the saloon were corridors leading to 22 individual passenger berths, arranged two deep, a total of 44 berths for the saloon as a whole. The forward part of the saloon, nearest the engine room, contained two ladies' boudoirs or private sitting rooms, which could be accessed without entering the saloon from the 12 nearest passenger berths, reserved for women. The opposite end of the saloon opened onto the stern windows. Broad iron staircases at both ends of the saloon ran to the main deck above and the dining saloon below. The saloon was painted in "delicate tints", furnished along its length with fixed chairs of

The interior was divided into three decks, the upper two for passengers and the lower for cargo. The two passenger decks were divided into forward and aft compartments, separated by the engines and boiler amidships.

In the after section of the ship, the upper passenger deck contained the after or principal saloon, long by wide, which ran from just aft of the engine room to the stern. On each side of the saloon were corridors leading to 22 individual passenger berths, arranged two deep, a total of 44 berths for the saloon as a whole. The forward part of the saloon, nearest the engine room, contained two ladies' boudoirs or private sitting rooms, which could be accessed without entering the saloon from the 12 nearest passenger berths, reserved for women. The opposite end of the saloon opened onto the stern windows. Broad iron staircases at both ends of the saloon ran to the main deck above and the dining saloon below. The saloon was painted in "delicate tints", furnished along its length with fixed chairs of

On 26 July 1845—seven years after the Great Western Steamship Company had decided to build a second ship, and five years overdue—''Great Britain'' embarked on her maiden voyage, from

On 26 July 1845—seven years after the Great Western Steamship Company had decided to build a second ship, and five years overdue—''Great Britain'' embarked on her maiden voyage, from  In her second season of service in 1846, ''Great Britain'' successfully completed two round trips to New York at an acceptable speed, but was then laid up for repairs to one of her chain drums, which showed an unexpected degree of wear. Embarking on her third passage of the season to New York, her captain made a series of navigational errors that resulted in her being run hard aground in

In her second season of service in 1846, ''Great Britain'' successfully completed two round trips to New York at an acceptable speed, but was then laid up for repairs to one of her chain drums, which showed an unexpected degree of wear. Embarking on her third passage of the season to New York, her captain made a series of navigational errors that resulted in her being run hard aground in

The new owners decided not merely to give the vessel a total refit; the keel, badly damaged during the grounding, was completely renewed along a length of , and the owners took the opportunity to further strengthen the hull. The old

The new owners decided not merely to give the vessel a total refit; the keel, badly damaged during the grounding, was completely renewed along a length of , and the owners took the opportunity to further strengthen the hull. The old

In 1882 ''Great Britain'' was converted into a

In 1882 ''Great Britain'' was converted into a

The recovery and subsequent voyage from the Falklands to Bristol were depicted in the 1970 BBC '' Chronicle'' programme, ''The Great Iron Ship''.

The original intent was to restore her to her 1843 state. However, the philosophy changed and the conservation of all surviving pre-1970 material became the aim. In 1984 the SS ''Great Britain'' was designated as a Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, the fourth such designation outside the USA.

By 1998, an extensive survey discovered that the hull was continuing to corrode in the humid atmosphere of the dock and estimates gave her 25 years before she corroded away. Extensive conservation work began which culminated in the installation of a glass plate across the dry dock at the level of her water line, with two

The recovery and subsequent voyage from the Falklands to Bristol were depicted in the 1970 BBC '' Chronicle'' programme, ''The Great Iron Ship''.

The original intent was to restore her to her 1843 state. However, the philosophy changed and the conservation of all surviving pre-1970 material became the aim. In 1984 the SS ''Great Britain'' was designated as a Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, the fourth such designation outside the USA.

By 1998, an extensive survey discovered that the hull was continuing to corrode in the humid atmosphere of the dock and estimates gave her 25 years before she corroded away. Extensive conservation work began which culminated in the installation of a glass plate across the dry dock at the level of her water line, with two

''Great Britain'' featured in several television specials.

*The

''Great Britain'' featured in several television specials.

*The

Official websiteI. K. BrunelPanoramic tour from the BBCThe Great Britain Steamer

''Australian Town and Country Journal'', 31 December 1870, p. 17, at

BBC Chronicle 1970 – The Great Iron Ship – SS ''Great Britain'' Rescue

{{DEFAULTSORT:Great Britain, SS Ships built in Bristol Bristol Harbourside Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmarks Museum ships in the United Kingdom Passenger ships of the United Kingdom Steamships of the United Kingdom

Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "on ...

(1806–1859), for the Great Western Steamship Company

The Great Western Steam Ship Company operated the first regular transatlantic steamer service from 1838 until 1846. Related to the Great Western Railway, it was expected to achieve the position that was ultimately secured by the Cunard Line. Th ...

's transatlantic

Transatlantic, Trans-Atlantic or TransAtlantic may refer to:

Film

* Transatlantic Pictures, a film production company from 1948 to 1950

* Transatlantic Enterprises, an American production company in the late 1970s

* ''Transatlantic'' (1931 film) ...

service between Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

and New York City. While other ships had been built of iron or equipped with a screw propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

, ''Great Britain'' was the first to combine these features in a large ocean-going ship. She was the first iron steamer to cross the Atlantic Ocean, which she did in 1845, in 14 days.

The ship is in length and has a 3,400-ton displacement. She was powered by two inclined two-cylinder engines of the direct-acting type, with twin high pressure cylinders (diameter uncertain) and twin low pressure cylinders bore, all of stroke cylinders. She was also provided with secondary masts for sail power. The four decks provided accommodation for a crew of 120, plus 360 passengers who were provided with cabins, and dining and promenade saloons.

When launched in 1843, ''Great Britain'' was by far the largest vessel afloat. But her protracted construction time of six years (1839–1845) and high cost had left her owners in a difficult financial position, and they were forced out of business in 1846, having spent all their remaining funds refloating the ship after she ran aground at Dundrum Bay

Dundrum Bay (Old Irish ''Loch Rudraige'') is a bay located next to Dundrum, County Down, Northern Ireland. It is divided into the Outer Bay, and the almost entirely landlocked Inner Bay. They are separated by the dune systems of Ballykinler to th ...

in County Down near Newcastle Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area in Australia, named after Newcastle ...

in what is now Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

, after a navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation, ...

error. In 1852 she was sold for salvage and repaired. ''Great Britain'' later carried thousands of emigrants to Australia from 1852 until being converted to all-sail in 1881. Three years later, she was retired to the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

, where she was used as a warehouse, quarantine ship and coal hulk

A hulk is a ship that is afloat, but incapable of going to sea. Hulk may be used to describe a ship that has been launched but not completed, an abandoned wreck or shell, or to refer to an old ship that has had its rigging or internal equipment ...

until she was scuttled

Scuttling is the deliberate sinking of a ship. Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel from becoming a navigation hazard; as an act of self-destruction to prevent the ship from being ...

in 1937, 98 years after being laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

.

In 1970, after ''Great Britain'' had been abandoned for 33 years, Sir Jack Arnold Hayward, OBE (1923–2015) paid for the vessel to be raised and repaired enough to be towed north through the Atlantic back to the United Kingdom, and returned to the Bristol dry dock where she had been built 127 years earlier. Hayward was a prominent businessman, developer, philanthropist and owner of the English football club Wolverhampton Wanderers

Wolverhampton Wanderers Football Club (), commonly known as Wolves, is a professional football club based in Wolverhampton, England, which compete in the . The club has played at Molineux Stadium since moving from Dudley Road in 1889. The club's ...

. Now listed as part of the National Historic Fleet

The National Historic Fleet is a list of historic ships and vessels located in the United Kingdom, under the National Historic Ships register. National Historic Ships UK is an advisory body which advises the Secretary of State for Culture, Media ...

, ''Great Britain'' is a visitor attraction and museum ship in Bristol Harbour, with between 150,000 and 200,000 visitors annually.

Development

After the initial success of its first liner, of 1838, the

After the initial success of its first liner, of 1838, the Great Western Steamship Company

The Great Western Steam Ship Company operated the first regular transatlantic steamer service from 1838 until 1846. Related to the Great Western Railway, it was expected to achieve the position that was ultimately secured by the Cunard Line. Th ...

collected materials for a sister ship, tentatively named ''City of New York''. The same engineering team that had collaborated so successfully on ''Great Western''— Isambard Brunel, Thomas Guppy, Christopher Claxton and William Patterson—was again assembled. This time however, Brunel, whose reputation was at its height, came to assert overall control over the design of the ship—a state of affairs that would have far-reaching consequences for the company. Construction was carried out in a specially adapted dry dock in Bristol, England.

Adoption of iron hull

Two chance encounters were profoundly to affect the design of ''Great Britain''. In late 1838, John Laird'sEnglish Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

packet ship

Packet boats were medium-sized boats designed for domestic mail, passenger, and freight transportation in European countries and in North American rivers and canals, some of them steam driven. They were used extensively during the 18th and 19th ...

''Rainbow''—the largest iron-hulled

Husk (or hull) in botany is the outer shell or coating of a seed. In the United States, the term husk often refers to the leafy outer covering of an ear of maize (corn) as it grows on the plant. Literally, a husk or hull includes the protective ...

ship then in service—made a stop at Bristol. Brunel despatched his associates Christopher Claxton and William Patterson to make a return voyage to Antwerp on ''Rainbow'' to assess the utility of the new building material. Both men returned as converts to iron-hulled technology, and Brunel scrapped his plans to build a wooden ship and persuaded the company directors to build an iron-hulled ship.

''Great Britain''s builders recognised a number of advantages of iron over the traditional wooden hull. Wood was becoming more expensive, while iron was getting cheaper. Iron hulls were not subject to

''Great Britain''s builders recognised a number of advantages of iron over the traditional wooden hull. Wood was becoming more expensive, while iron was getting cheaper. Iron hulls were not subject to dry rot

Dry rot is wood decay caused by one of several species of fungi that digest parts of the wood which give the wood strength and stiffness. It was previously used to describe any decay of cured wood in ships and buildings by a fungus which resul ...

or woodworm

A woodworm is the wood-eating larva of many species of beetle. It is also a generic description given to the infestation of a wooden item (normally part of a dwelling or the furniture in it) by these larvae.

Types of woodworm

Woodboring beetle ...

, and they were also lighter in weight and less bulky. The chief advantage of the iron hull was its much greater structural strength. The practical limit on the length of a wooden-hulled ship is about 300 feet (91 m), after which hogging—the flexing of the hull as waves pass beneath it—becomes too great. Iron hulls are far less subject to hogging so the potential size of an iron-hulled ship is much greater. The ship's designers, led by Brunel, were initially cautious in the adaptation of their plans to iron-hulled technology. With each successive draft however, the ship grew ever larger and bolder in conception. By the fifth draft, the vessel had grown to 3,400 tons, over 1,000 tons larger than any ship then in existence.

Adoption of screw propulsion

In early 1840, a second chance encounter occurred, the arrival of the revolutionary at Bristol, the first screw-propelled steamship, completed only a few months before by

In early 1840, a second chance encounter occurred, the arrival of the revolutionary at Bristol, the first screw-propelled steamship, completed only a few months before by Francis Pettit Smith

Sir Francis Pettit Smith (9 February 1808 – 12 February 1874) was an English inventor and, along with John Ericsson, one of the inventors of the screw propeller. He was also the driving force behind the construction of the world's first scr ...

's Propeller Steamship Company. Brunel had been looking into methods of improving the performance of ''Great Britain''s paddlewheel

A paddle wheel is a form of waterwheel or impeller in which a number of paddles are set around the periphery of the wheel. It has several uses, of which some are:

* Very low-lift water pumping, such as flooding paddy fields at no more than about ...

s, and took an immediate interest in the new technology. Smith, sensing a prestigious new customer for his own company, agreed to lend ''Archimedes'' to Brunel for extended tests. Over several months, Smith and Brunel tested a number of different propellers on ''Archimedes'' to find the most efficient design, a four-bladed model submitted by Smith.

Having satisfied himself as to the advantages of screw propulsion, Brunel wrote to the company directors to persuade them to embark on a second major design change, abandoning the paddlewheel engines(already half-constructed) for completely new engines suitable for powering a propeller.

Brunel listed the advantages of the screw propeller over the paddlewheel as follows:

* Screw propulsion machinery was lighter in weight, thus improving fuel economy;

* Screw propulsion machinery could be kept lower in the hull, lowering the ship's centre of gravity and making it more stable in heavy seas;

* By taking up less room, propeller engines would allow more cargo to be carried;

* Elimination of bulky paddle boxes would lessen resistance through the water, and also allow the ship to manoeuvre more easily in confined waterways;

* The depth of a paddlewheel is constantly changing, depending on the ship's cargo and the movement of waves, while a propeller stays fully submerged and at full efficiency at all times;

* Screw propulsion machinery was cheaper.

Brunel's arguments proved persuasive, and in December 1840, the company agreed to adopt the new technology. The decision became a costly one, setting the ship's completion back by nine months.

Reporting on the ship's arrival in New York, in its first issue ''Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many famous scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it. In print since 1845, it ...

'' opined, "If there is any thing objectionable in the construction or machinery of this noble ship, it is the mode of propelling her by the screw propeller; and we should not be surprised if it should be, ere long, superseded by paddle wheels at the sides."

Launch

The launching or, more accurately, the

The launching or, more accurately, the float-out

Float-out is the process in shipbuilding that follows the keel laying and precedes the fitting-out process. It is analogous to launching a ship, a specific process that has largely been discontinued in modern shipbuilding. Both floating-out an ...

took place on 19 July 1843. Conditions were generally favourable and diarists recorded that, after a dull start, the weather brightened with only a few intermittent showers. The atmosphere of the day can best be gauged from a report the following day in ''The Bristol Mirror'':

Large crowds started to gather early in the day including many people who had travelled to Bristol to see the spectacle. There was a general atmosphere of anticipation as the Royal Emblem was unfurled. The processional route had been cleaned and Temple Street decorated with flags, banners, flowers and ribbons. Boys of the City School and girls of Red Maids were stationed in a neat orderly formation down the entire length of the Exchange. The route was a mass of colour and everybody was out on the streets as it was a public holiday. The atmosphere of gaiety even allowed thoughts to drift away from the problems of political dissension in London.Prince Albert arrived at 10 a.m. at the Great Western Railway terminus. The

royal train

A royal train is a set of railway carriages dedicated for the use of the monarch or other members of a royal family. Most monarchies with a railway system employ a set of royal carriages.

Australia

The various government railway operators of ...

, conducted by Brunel himself, had taken two hours and forty minutes from London. There was a guard of honour of members of the police force, soldiers and dragoons and, as the Prince stepped from the train, the band of the Life Guards played works by Labitsky and a selection from the "Ballet of Alma". Two sections of the platform were boarded off for the reception and it was noted by ''The Bristol Mirror'' that parts were covered with carpets from the Council House. The Prince Consort, dressed as a private gentleman, was accompanied by his equerry-in-waiting, personal secretary, the Marquess of Exeter

Marquess of Exeter is a title that has been created twice, once in the Peerage of England and once in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. The first creation came in the Peerage of England in 1525 for Henry Courtenay, 2nd Earl of Devon. For more ...

, and Lords Wharncliffe, Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

, Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincol ...

and Wellesley.

Another extended delay

Following the launch ceremony, the builders had planned to have ''Great Britain'' towed to the

Following the launch ceremony, the builders had planned to have ''Great Britain'' towed to the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

for her final fitting out. Unfortunately, the harbour authorities had failed to carry out the necessary modifications to their facilities in a timely manner. Exacerbating the problem, the ship had been widened beyond the original plans to accommodate the propeller engines, and her designers had made a belated decision to fit the engines prior to launch, which resulted in a deeper draught.

This dilemma was to result in another costly delay for the company, as Brunel's negotiations with the Bristol Dock Board dragged on for months. It was only through the intervention of the Board of Trade that the harbour authorities finally agreed to the lock modifications, which began in late 1844.

After being trapped in the harbour for more than a year, ''Great Britain'' was, at last, floated out in December 1844, but not before causing more anxiety for her proprietors. After passing successfully through the first set of lock gates, she jammed on her passage through the second, which led to the River Avon. Only the seamanship of Captain Claxton (who after naval service held the position of quay warden (harbour master) at Bristol) enabled her to be pulled back and severe structural damage avoided. The following day an army of workmen, under the direct control of Brunel, took advantage of the slightly higher tide and removed coping stones and lock gate platforms from the Junction Lock, allowing the tug ''Samson'', again under Claxton's supervision, to tow the ship safely into the Avon that midnight.

Description

General description

When completed in 1845, ''Great Britain'' was a revolutionary vessel—the first ship to combine an iron hull with screw propulsion, and at in length and with a 3,400-ton displacement, more than longer and 1,000 tons larger than any ship previously built. Her beam was and her height from keel to main deck, . She had four decks, including the spar (upper) deck, a crew of 120, and was fitted to accommodate a total of 360 passengers, along with 1,200 tons of cargo and 1,200 tons of

When completed in 1845, ''Great Britain'' was a revolutionary vessel—the first ship to combine an iron hull with screw propulsion, and at in length and with a 3,400-ton displacement, more than longer and 1,000 tons larger than any ship previously built. Her beam was and her height from keel to main deck, . She had four decks, including the spar (upper) deck, a crew of 120, and was fitted to accommodate a total of 360 passengers, along with 1,200 tons of cargo and 1,200 tons of coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

for fuel.

Like other steamships of the era, ''Great Britain'' was provided with secondary sail power, consisting of one square-rigged and five schooner-rigged masts—a relatively simple sail plan designed to reduce the number of crew required. The masts were of iron, fastened to the spar deck with iron joints, and with one exception, hinged to allow their lowering to reduce wind resistance in the event of a strong headwind. The rigging was of iron cable instead of the traditional hemp, again with a view to reducing wind resistance. Another innovative feature was the lack of traditional heavy bulwarks around the main deck; a light iron railing both reduced weight and allowed water shipped in heavy weather to run unimpeded back to sea.

The hull and single funnel

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its construct ...

amidships were both finished in black paint, with a single white stripe running the length of the hull highlighting a row of false gunports. The hull was flat-bottomed, with no external keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

, and with bulges low on each side amidships which continued toward the stern in an unusual implementation of tumblehome

Tumblehome is a term describing a hull which grows narrower above the waterline than its beam. The opposite of tumblehome is flare.

A small amount of tumblehome is normal in many naval architecture designs in order to allow any small projecti ...

—a result of the late decision to install propeller engines, which were wider at the base than the originally planned paddlewheel engines.

Brunel, anxious to ensure the avoidance of hogging in a vessel of such unprecedented size, designed the hull to be massively redundant in strength. Ten longitudinal iron girders were installed along the keel, running from beneath the engines and boiler to the forward section. The iron ribs were in size. The iron keel plates were an inch thick, and the hull seams were lapped and double rivet

A rivet is a permanent mechanical fastener. Before being installed, a rivet consists of a smooth cylindrical shaft with a head on one end. The end opposite to the head is called the ''tail''. On installation, the rivet is placed in a punched ...

ed in many places. Safety features, which also contributed to the structural strength of the vessel, included a double bottom and five watertight iron bulkheads. The total amount of iron, including the engines and machinery, was 1,500 tons.

Machinery

Two giant propeller engines, with a combined weight of 340 tons, were installed amidships. They were built to a modified patent of Brunel's father

Two giant propeller engines, with a combined weight of 340 tons, were installed amidships. They were built to a modified patent of Brunel's father Marc Marc or MARC may refer to:

People

* Marc (given name), people with the first name

* Marc (surname), people with the family name

Acronyms

* MARC standards, a data format used for library cataloging,

* MARC Train, a regional commuter rail system o ...

. The engines, which rose from the keel through the three lower decks to a height just below the main deck, were of the direct-acting type, with twin bore, stroke cylinders inclined upward at a 60° angle, capable of developing a total of at 18 rpm

Revolutions per minute (abbreviated rpm, RPM, rev/min, r/min, or with the notation min−1) is a unit of rotational speed or rotational frequency for rotating machines.

Standards

ISO 80000-3:2019 defines a unit of rotation as the dimensionl ...

. Steam power was provided by three long by high by wide, "square" saltwater boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, centr ...

s, forward of the engines, with eight furnaces each – four at each end.

In considering the gearing arrangement, Brunel had no precedent to serve as a guide. The gearing for ''Archimedes'', of the spur-and-pinion type, had proven almost unbearably noisy, and would not be suitable for a passenger ship. Brunel's solution was to install a chain drive. On the crankshaft between ''Great Britain''s two engines, he installed an diameter primary gearwheel, which, by means of a set of four massive inverted-tooth or "silent" chains, operated the smaller secondary gear near the keel, which turned the propeller shaft. This was the first commercial use of silent chain technology, and the individual silent chains installed in ''Great Britain'' are thought to have been the largest ever constructed.

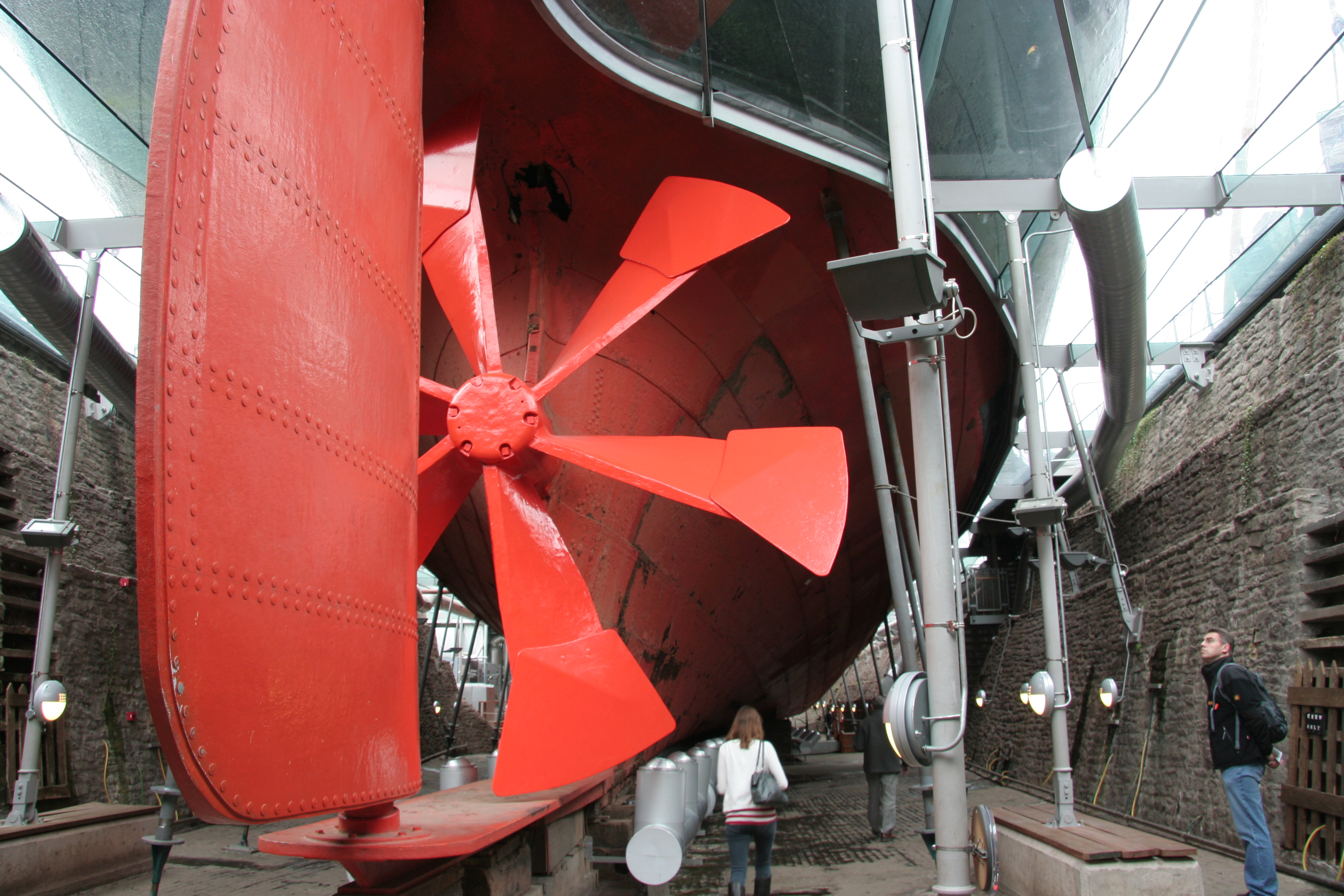

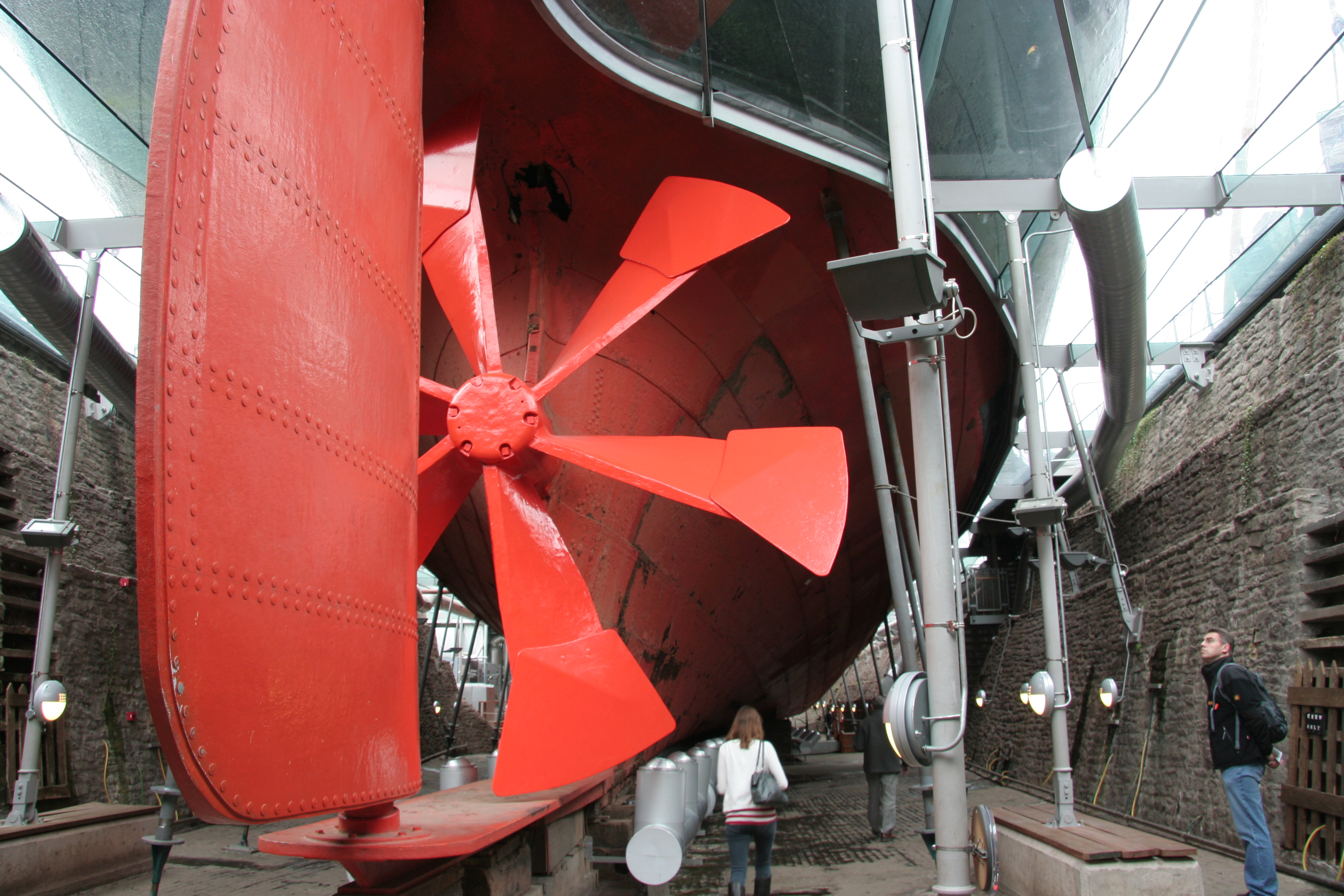

''Great Britain''s main propeller shaft, built by the Mersey Iron Works, was the largest single piece of machinery. long and in diameter, the shaft was bored with a diameter hole, reducing its weight and allowing cold water to be pumped through to reduce heat. At each end of the main propeller shaft were two secondary coupling shafts: a , diameter shaft beneath the engine, and a screw shaft of in diameter at the stern. Total length of the three shafts was , and the total weight 38 tons. The shaft was geared upward at a ratio of 1 to 3, so that at the engines' normal operating speed of 18 rpm, the propeller turned at a speed of 54 rpm. The initial propeller was a six-bladed "windmill" model of Brunel's own design, in diameter and with pitch of .

Interior

The interior was divided into three decks, the upper two for passengers and the lower for cargo. The two passenger decks were divided into forward and aft compartments, separated by the engines and boiler amidships.

In the after section of the ship, the upper passenger deck contained the after or principal saloon, long by wide, which ran from just aft of the engine room to the stern. On each side of the saloon were corridors leading to 22 individual passenger berths, arranged two deep, a total of 44 berths for the saloon as a whole. The forward part of the saloon, nearest the engine room, contained two ladies' boudoirs or private sitting rooms, which could be accessed without entering the saloon from the 12 nearest passenger berths, reserved for women. The opposite end of the saloon opened onto the stern windows. Broad iron staircases at both ends of the saloon ran to the main deck above and the dining saloon below. The saloon was painted in "delicate tints", furnished along its length with fixed chairs of

The interior was divided into three decks, the upper two for passengers and the lower for cargo. The two passenger decks were divided into forward and aft compartments, separated by the engines and boiler amidships.

In the after section of the ship, the upper passenger deck contained the after or principal saloon, long by wide, which ran from just aft of the engine room to the stern. On each side of the saloon were corridors leading to 22 individual passenger berths, arranged two deep, a total of 44 berths for the saloon as a whole. The forward part of the saloon, nearest the engine room, contained two ladies' boudoirs or private sitting rooms, which could be accessed without entering the saloon from the 12 nearest passenger berths, reserved for women. The opposite end of the saloon opened onto the stern windows. Broad iron staircases at both ends of the saloon ran to the main deck above and the dining saloon below. The saloon was painted in "delicate tints", furnished along its length with fixed chairs of oak

An oak is a tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' (; Latin "oak tree") of the beech family, Fagaceae. There are approximately 500 extant species of oaks. The common name "oak" also appears in the names of species in related genera, notably ''L ...

, and supported by 12 decorated pillars.

Beneath the after saloon was the main or dining saloon, long by wide, with dining tables and chairs capable of accommodating up to 360 people at one sitting. On each side of the saloon, seven corridors opened onto four berths each, for a total number of berths per side of 28, or 56 altogether. The forward end of the saloon was connected to a stewards' galley, while the opposite end contained several tiers of sofas. This saloon was apparently the ship's most impressive of all the passenger spaces. Columns of white and gold, 24 in number, with "ornamental capitals of great beauty", were arranged down its length and along the walls, while eight Arabesque

The arabesque is a form of artistic decoration consisting of "surface decorations based on rhythmic linear patterns of scrolling and interlacing foliage, tendrils" or plain lines, often combined with other elements. Another definition is "Foli ...

pilaster

In classical architecture, a pilaster is an architectural element used to give the appearance of a supporting column and to articulate an extent of wall, with only an ornamental function. It consists of a flat surface raised from the main wal ...

s, decorated with "beautifully painted" oriental flowers and birds, enhanced the aesthetic effect. The archways of the doors were "tastefully carved and gilded" and surmounted with medallion heads. Mirrors around the walls added an illusion of spaciousness, and the walls themselves were painted in a "delicate lemon-tinted hue" with highlights of blue and gold.

The two forward saloons were arranged in a similar plan to the after saloons, with the upper "promenade" saloon having 36 berths per side and the lower 30, totalling 132. Further forward, separate from the passenger saloons, were the crew quarters. The overall finish of the passenger quarters was unusually restrained for its time, a probable reflection of the proprietors' diminishing capital reserves. Total cost of construction of the ship, not including £53,000 for plant and equipment to build her, was £117,000—£47,000 more than her original projected price tag of £70,000.

Service history

Transatlantic service

On 26 July 1845—seven years after the Great Western Steamship Company had decided to build a second ship, and five years overdue—''Great Britain'' embarked on her maiden voyage, from

On 26 July 1845—seven years after the Great Western Steamship Company had decided to build a second ship, and five years overdue—''Great Britain'' embarked on her maiden voyage, from Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

to New York under Captain James Hosken, with 45 passengers. The ship made the passage in 14 days and 21 hours, at an average speed of – almost slower than the prevailing record. She made the return trip in days, again an unexceptional time.

Brunel, who prior to commencement of service had substituted a six-bladed "windmill" design of his own for Smith's proven four-bladed propeller design, now decided to try to improve the speed by riveting an extra two inches of iron to each propeller blade. On her next crossing to New York, carrying 104 passengers, the ship ran into heavy weather, losing a mast and three propeller blades. On 13 October, she ran aground on the Massachusetts Shoals. She was refloated and after obtaining a supply of coal from the American schooner ''David Coffin'' resumed her voyage. After repairs in New York, she set out for Liverpool with only 28 passengers and lost four propeller blades during the crossing. By this time, another design flaw had become evident. The ship rolled heavily, especially in calm weather without the steadying influence of the sail, causing discomfort to passengers.

The shareholders of the company again provided further funding to try to solve the problems. The six-bladed propeller was dispensed with and replaced with the original four-bladed, cast iron design. The third mast was removed, and the iron rigging, which had proven unsatisfactory, was replaced with conventional rigging. In a major alteration, two bilge keel

A bilge keel is a nautical device used to reduce a ship's tendency to roll. Bilge keels are employed in pairs (one for each side of the ship). A ship may have more than one bilge keel per side, but this is rare. Bilge keels increase hydrodynamic r ...

s were added to each side in an effort to lessen her tendency to roll. These repairs and alterations delayed her return to service until the following year.

In her second season of service in 1846, ''Great Britain'' successfully completed two round trips to New York at an acceptable speed, but was then laid up for repairs to one of her chain drums, which showed an unexpected degree of wear. Embarking on her third passage of the season to New York, her captain made a series of navigational errors that resulted in her being run hard aground in

In her second season of service in 1846, ''Great Britain'' successfully completed two round trips to New York at an acceptable speed, but was then laid up for repairs to one of her chain drums, which showed an unexpected degree of wear. Embarking on her third passage of the season to New York, her captain made a series of navigational errors that resulted in her being run hard aground in Dundrum Bay

Dundrum Bay (Old Irish ''Loch Rudraige'') is a bay located next to Dundrum, County Down, Northern Ireland. It is divided into the Outer Bay, and the almost entirely landlocked Inner Bay. They are separated by the dune systems of Ballykinler to th ...

on the northeast coast of Ireland on 22 September. There was no formal inquiry but it has been recently suggested by Dr Helen Doe in her book 'SS Great Britain' that it was mainly due to the captain not having updated charts, so that he mistook the new St John's light for the Calf light on the Isle of Man.

She remained aground for almost a year, protected by temporary measures organised by Brunel and James Bremner. On 25 August 1847, she was floated free at a cost of £34,000 and taken back to Liverpool, but this expense exhausted the company's remaining reserves. After languishing in Prince's Dock, Liverpool for some time, she was sold to Gibbs, Bright & Co., former agents of the Great Western Steamship Company, for a mere £25,000.

Refit and return to service

The new owners decided not merely to give the vessel a total refit; the keel, badly damaged during the grounding, was completely renewed along a length of , and the owners took the opportunity to further strengthen the hull. The old

The new owners decided not merely to give the vessel a total refit; the keel, badly damaged during the grounding, was completely renewed along a length of , and the owners took the opportunity to further strengthen the hull. The old keelson

The keelson or kelson is a reinforcing structural member on top of the keel in the hull of a wooden vessel.

In part V of “ Song of Myself”, American poet Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an Am ...

s were replaced and 10 new ones laid, which ran the entire length of the keel. Both the bow and stern were also strengthened by heavy frames of double angle iron.

Reflecting the rapid advances in propeller engine technology, the original engines were removed and replaced with a pair of smaller, lighter and more modern oscillating

Oscillation is the repetitive or periodic variation, typically in time, of some measure about a central value (often a point of equilibrium) or between two or more different states. Familiar examples of oscillation include a swinging pendulum ...

engines, with cylinders and stroke, built by John Penn & Sons of Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

. They were also provided with more support at the base and supported further by the addition of both iron and wood beams running transversely across the hull, which had the added benefit of reducing engine vibration.

The cumbersome chain-drive gearing was replaced with a simpler and by now proven cog-wheel arrangement, although the gearing of the engines to the propeller shaft remained at a ratio of one to three. The three large boilers were replaced with six smaller ones, operating at or twice the pressure of their predecessors. Along with a new cabin on the main deck, the smaller boilers allowed the cargo capacity to be almost doubled, from 1,200 to 2,200 tons.

The four-bladed propeller was replaced by a slightly smaller three-bladed model, and the bilge keels, previously added to reduce the tendency to roll, were replaced by a heavy external oak keel for the same purpose. The five-masted schooner sail-plan was replaced by four masts, two of which were square-rigged. With the refit complete, ''Great Britain'' went back into service on the New York run. After only one further round trip she was sold again, to Antony Gibbs & Sons, which planned to place her into England–Australia service.

Australian service

Antony Gibbs & Sons may have intended to employ ''Great Britain'' only to exploit a temporary demand for passenger service to the Australian goldfields following the discovery of gold in Victoria in 1851, but she found long-term employment on this route. For her new role, she was given a third refit. Her passenger accommodation was increased from 360 to 730, and her sail plan altered to a traditional three-masted, square-rigged pattern. She was fitted with a removable propeller, which could be hauled up on deck by chains to reduce drag when under sail power alone. In 1852, ''Great Britain'' made her first voyage toMelbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

, Australia, carrying 630 emigrants

Emigration is the act of leaving a resident country or place of residence with the intent to settle elsewhere (to permanently leave a country). Conversely, immigration describes the movement of people into one country from another (to permanentl ...

. She excited great interest there, with 4,000 people paying a shilling each to inspect her. She operated on the England–Australia route for almost 30 years, interrupted only by two relatively brief sojourns as a troopship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typicall ...

during the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

and the Indian Mutiny. Gradually, she earned a reputation as the most reliable of the emigrant ships to Australia and carried the first English cricket team to tour Australia in 1861.

Alexander Reid, writing in 1862, recorded some statistics of a typical voyage. The ship, with a crew of 143, put out from Liverpool on 21 October 1861, carrying 544 passengers (including the English cricket team that was the first to visit Australia), a cow, 36 sheep, 140 pigs, 96 goats and 1,114 chickens, ducks, geese and turkeys. The journey to Melbourne (her ninth) occupied 64 days, during which the best day's run was 354 miles and the worst 108. With favourable winds the ship travelled under sail alone, the screw being withdrawn from the water. Three passengers died en route. The captain was John Gray, a Scot, who had held the post since before the Crimean War.

On 8 December 1863, she was reported to have been wrecked on Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whos ...

, Cape Verde Islands

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

whilst on a voyage from London to Nelson, New Zealand. All on board were rescued. On 8 October 1868 ''The Argus'' reported "To-day, at daylight, the fine steamship ''Great Britain'' will leave her anchorage in Hobson's Bay, for Liverpool direct. On this occasion she carries less than her usual complement of passengers, the season not being a favourite one with colonists desiring to visit their native land. ''Great Britain'', however, has a full cargo, and carries gold to the value of about £250,000. As she is in fine trim, we shall probably have, in due time, to congratulate Captain Gray on having achieved another successful voyage." Gray died under mysterious circumstances, going missing overnight during a return voyage from Melbourne, on the night of 25/26 November 1872. On 22 December, she rescued the crew of the British brig ''Druid'', which had been abandoned in the Atlantic Ocean. On 19 November 1874, she collided with the British ship ''Mysore'' in the Sloyne, losing an anchor and sustaining hull damage. ''Great Britain'' was on a voyage from Melbourne to Liverpool.

Later history

sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing square-rigged or fore-and-aft sails. Some ships ...

to transport bulk coal. She made her final voyage in 1886, after loading up with coal and leaving Penarth Dock

Penarth Dock was a port and harbour which was located on the south bank of the mouth of the River Ely, at Penarth, Glamorgan, Wales. It opened in 1865 and reached its heyday before World War I, after which followed a slow decline until clos ...

in Wales for Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

on 8 February. After a fire on board en route she was found on arrival at Port Stanley

Stanley (; also known as Port Stanley) is the capital city of the Falkland Islands. It is located on the island of East Falkland, on a north-facing slope in one of the wettest parts of the islands. At the 2016 census, the city had a popula ...

in the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

where she ran aground. She was found to be damaged beyond economic repair. She was sold to the Falkland Islands Company

The Falkland Islands Company Ltd is a diversified goods and services company owned by FIH Group. Known locally as FIC, it was founded in 1851 and was granted a royal charter to trade in 1852 by Queen Victoria. It was originally founded by Samue ...

and used, afloat, as a storage hulk (coal bunker) until 1937, when she was towed to Sparrow Cove, from Port Stanley, scuttled and abandoned. As a bunker, she coaled the South Atlantic fleet that defeated Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee's fleet in the First World War Battle of the Falkland Islands

The Battle of the Falkland Islands was a First World War naval action between the British Royal Navy and Imperial German Navy on 8 December 1914 in the South Atlantic. The British, after their defeat at the Battle of Coronel on 1 November, s ...

. In the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, some of her iron was scavenged to repair , one of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

ships that fought '' Graf Spee'' and was badly damaged during the Battle of the River Plate

The Battle of the River Plate was fought in the South Atlantic on 13 December 1939 as the first naval battle of the Second World War. The Kriegsmarine heavy cruiser , commanded by Captain Hans Langsdorff, engaged a Royal Navy squadron, command ...

.

Notable passengers and crew

The ''Great Britain'' carried over 33,000 people during her working life. These included: * Gustavus Vaughan Brooke, Irish stage actor; travelled with Avonia Jones between Melbourne and Liverpool in 1861 * Fanny Duberly, author and chronicler of theCrimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

and the Indian Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the fo ...

; travelled between Cork and Mumbai

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — List of renamed Indian cities and states#Maharashtra, the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' fin ...

in 1857

* Colonel Sir George Everest

Colonel Sir George Everest CB FRS FRAS FRGS (; 4 July 1790 – 1 December 1866) was a British surveyor and geographer who served as Surveyor General of India from 1830 to 1843.

After receiving a military education in Marlow, Everest joined ...

, British surveyor and geographer; served as Surveyor General of India; namesake of Mount Everest

Mount Everest (; Tibetic languages, Tibetan: ''Chomolungma'' ; ) is List of highest mountains on Earth, Earth's highest mountain above sea level, located in the Mahalangur Himal sub-range of the Himalayas. The China–Nepal border ru ...

; travelled between Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

and New York in 1845

* John Gray, Scottish born seaman; the ''Great Britain''s longest serving captain; mysteriously disappeared while at sea; crew member 1852–1872

* James Hosken, first captain of the ''Great Britain'' and before that the '' Great Western'' from her maiden voyage until she ran aground in Dundrum Bay

Dundrum Bay (Old Irish ''Loch Rudraige'') is a bay located next to Dundrum, County Down, Northern Ireland. It is divided into the Outer Bay, and the almost entirely landlocked Inner Bay. They are separated by the dune systems of Ballykinler to th ...

* Avonia Jones, American actress, travelled with Gustavus Vaughan Brooke between Melbourne and Liverpool in 1861

* Sister Mary Paul Mulquin

Sister Mary Paul Mulquin (1842 – 10 February 1930) was a Roman Catholic nun and educationalist born in Adare, Limerick, Ireland. Born Katherine Mulquin to John Mulquin, a landowner, and his wife Catherine, née Sheehy, she changed her name in ...

, Roman Catholic nun and educationalist; travelled between Liverpool and Melbourne in 1873

* Elizabeth Parsons, English-Australian artist, travelled between Liverpool and Melbourne in 1870.

* Anthony Trollope, English novelist of the Victorian era; travelled between Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

and Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

in 1871, and wrote '' Lady Anna'' during the voyage

* Augustus Arkwright

Augustus Peter Arkwright (2 March 1821 – 6 October 1887) was a Royal Navy officer and a Conservative Party politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1868 to 1880.

Arkwright was the seventh son of Peter Arkwright J.P. of Rock House, near ...

, Royal Navy officer and a Conservative Party politician, and great grandson of Richard Arkwright, travelled between Liverpool and New York in 1852.

* George Inness

George Inness (May 1, 1825 – August 3, 1894) was a prominent American landscape painter.

Now recognized as one of the most influential American artists of the nineteenth century, Inness was influenced by the Hudson River School at the s ...

, prominent American landscape painter, travelled with his wife between Liverpool and New York in 1852.

* Henry Arthur Bright, English merchant and author, and partner in Gibbs, Bright & Co., travelled between Liverpool and New York in 1852.

* John Simcoe Macaulay

Colonel The Hon. John Simcoe Macaulay (13 October 1791 – 20 December 1855) was a businessman and political figure in Upper Canada. In 1845, before retiring to England, he donated the land on which the Church of the Holy Trinity (Toronto) w ...

, businessman and political figure in Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of th ...

, travelled between Liverpool and New York in 1852.

* William Charles (fur trader), Pacific coast pioneer, Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

factor, and a prominent figure in the early history of British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

, travelled between Liverpool and New York in 1852.

* Francis Pettit Smith

Sir Francis Pettit Smith (9 February 1808 – 12 February 1874) was an English inventor and, along with John Ericsson, one of the inventors of the screw propeller. He was also the driving force behind the construction of the world's first scr ...

, one of the inventors of the screw propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

, travelled between Liverpool and New York in 1852.

Recovery and restoration

The salvage operation, made possible by several large donations, including fromSir Jack Hayward

Sir Jack Arnold Hayward (14 June 1923 – 13 January 2015) was an English businessman, property developer, philanthropist, and president of English football club Wolverhampton Wanderers.

Biography

Early life

The only son of Charles William ...

and Sir Paul Getty, was organised by 'the SS ''Great Britain'' Project', chaired by Richard Goold-Adams. Ewan Corlett conducted a naval architect's survey, reporting that she could be refloated. A submersible pontoon, ''Mulus III'', was chartered in February 1970. A German tug, ''Varius II'', was chartered, reaching Port Stanley on 25 March. By 13 April, after some concern about a crack in the hull, the ship was mounted successfully on the pontoon and the following day the tug, pontoon and ''Great Britain'' sailed to Port Stanley for preparations for the transatlantic voyage. The voyage (code name "Voyage 47") began on 24 April, stopped in Montevideo from 2 May to 6 May for inspection, then across the Atlantic, arriving at Barry Docks

Barry Docks ( cy, Dociau'r Barri) is a port facility in the town of Barry, Vale of Glamorgan, Wales, a few miles southwest of Cardiff on the north shore of the Bristol Channel. They were opened in 1889 by David Davies and John Cory as an alterna ...

, west of Cardiff

Cardiff (; cy, Caerdydd ) is the capital and largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Cardiff ( cy, Dinas a Sir Caerdydd, links=no), and the city is the eleventh-largest in the United Kingd ...

on 22 June. ("Voyage 47" was chosen as the code name because it was on her 47th voyage from Penarth, in 1886, that during a tempest she had sought shelter in the Falklands.) Bristol-based tugs then took over and towed her, still on her pontoon, to Avonmouth Docks

The Avonmouth Docks are part of the Port of Bristol, in England. They are situated on the northern side of the mouth of the River Avon, opposite the Royal Portbury Dock on the southern side, where the river joins the Severn estuary, within Avo ...

.

The ship was then taken off the pontoon, in preparation for her re-entry into Bristol, now truly afloat. On Sunday 5 July, amidst considerable media interest, the ship was towed up the River Avon to Bristol. Perhaps the most memorable moment for the crowds that lined the final few miles was her passage under the Clifton Suspension Bridge

The Clifton Suspension Bridge is a suspension bridge spanning the Avon Gorge and the River Avon, linking Clifton in Bristol to Leigh Woods in North Somerset. Since opening in 1864, it has been a toll bridge, the income from which provides f ...

, another Brunel design. She waited for two weeks in the Cumberland Basin for a tide high enough to get her back through the locks to the Floating Harbour and her birthplace, the dry dock in the Great Western Dockyard (now a Grade II* listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

, disused since bomb damage in the Second World War).

The recovery and subsequent voyage from the Falklands to Bristol were depicted in the 1970 BBC '' Chronicle'' programme, ''The Great Iron Ship''.

The original intent was to restore her to her 1843 state. However, the philosophy changed and the conservation of all surviving pre-1970 material became the aim. In 1984 the SS ''Great Britain'' was designated as a Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, the fourth such designation outside the USA.

By 1998, an extensive survey discovered that the hull was continuing to corrode in the humid atmosphere of the dock and estimates gave her 25 years before she corroded away. Extensive conservation work began which culminated in the installation of a glass plate across the dry dock at the level of her water line, with two

The recovery and subsequent voyage from the Falklands to Bristol were depicted in the 1970 BBC '' Chronicle'' programme, ''The Great Iron Ship''.

The original intent was to restore her to her 1843 state. However, the philosophy changed and the conservation of all surviving pre-1970 material became the aim. In 1984 the SS ''Great Britain'' was designated as a Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, the fourth such designation outside the USA.

By 1998, an extensive survey discovered that the hull was continuing to corrode in the humid atmosphere of the dock and estimates gave her 25 years before she corroded away. Extensive conservation work began which culminated in the installation of a glass plate across the dry dock at the level of her water line, with two dehumidifiers

A dehumidifier is an air conditioning device which reduces and maintains the level of humidity in the air. This is done usually for health or thermal comfort reasons, or to eliminate musty odor and to prevent the growth of mildew by extracting wa ...

, keeping the space beneath at 20% relative humidity, sufficiently dry to preserve the surviving material. This being completed, the ship was "re-launched" in July 2005, and visitor access to the dry dock was restored. The site is visited by over 150,000 visitors a year with a peak in numbers in 2006 when 200,000 people visited.

Awards

The engineers Fenton Holloway won the IStructE Award for Heritage Buildings in 2006 for the restoration of ''Great Britain''. In May of that year, the ship won the prestigiousGulbenkian Prize Gulbenkian Prize is a series of prizes awarded annually by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. The main Gulbenkian Prize was established in 1976 as the Gulbenkian Science Prize awarded to Portuguese individuals and organizations.

Starting 2012, th ...

for museums and galleries. The chairman of the judging panel, Professor Robert Winston

Robert Maurice Lipson Winston, Baron Winston, (born 15 July 1940) is a British professor, medical doctor, scientist, television presenter and Labour Party politician.

Early life

Robert Winston was born in London to Laurence Winston and Rut ...

, commented:

The project won The Crown Estate Conservation Award in 2007, and the European Museum of the Year Award

The European Museum of the Year Award (EMYA) is presented each year by the European Museum Forum (European Museum Forum, EMF) under the auspices of the Council of Europe. The EMYA is considered the most important annual award in the European mu ...

s Micheletti Prize for 'Best Industrial or Technology Museum'. In 2008 the educational value of the project was honoured by the Sandford Award for Heritage Education.

Being Brunel

'Being Brunel' is a museum dedicated toIsambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "on ...

and built on the harbour next to his ship. Opened in 2018, it holds thousands of Brunel-related items, such as his school reports, his diaries and his technical drawing instruments. Costing £2 million, it occupies buildings on the quayside including Brunel's drawing office. It includes a reconstruction of his dining room from Duke Street, and the drawing office has been restored to its 1850 condition.

Popular culture

''Great Britain'' featured in several television specials.

*The

''Great Britain'' featured in several television specials.

*The ITV1

ITV1 (formerly known as ITV) is a British free-to-air public broadcast television channel owned and operated by the British media company ITV plc. It provides the Channel 3 public broadcast service across all of the United Kingdom except for t ...

series ''The West Country Tonight

''ITV News West Country'' is a British television news service broadcast and produced by ITV West Country.

Overview

''ITV News West Country''

is broadcast from studios in Brislington, Bristol, with district reporters and camera crews based in ...

'', in July 2010, told five aspects of the Great Britain's story: her history, her restoration and Bristolians' memories of her return to the city, showing their home footage of the event. Correspondent Robert Murphy travelled to Grand Bahama

Grand Bahama is the northernmost of the islands of the Bahamas, with the town of West End located east of Palm Beach, Florida. It is the third largest island in the Bahamas island chain of approximately 700 islands and 2,400 cays. The island i ...

for an exclusive interview with Sir Jack Hayward

Sir Jack Arnold Hayward (14 June 1923 – 13 January 2015) was an English businessman, property developer, philanthropist, and president of English football club Wolverhampton Wanderers.

Biography

Early life

The only son of Charles William ...

, then moved to the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

where he spoke with islanders who worked in the salvage team.

*A BBC West

BBC West is one of BBC's English Regions serving Bristol, the majority of Wiltshire and Gloucestershire; northern and eastern Somerset and northeastern Dorset.

Services Television

BBC West's television service (broadcast on BBC One) consists o ...

documentary called '' When Brunel's Ship Came Home'' tells the story of the salvage operation and was broadcast on BBC One in the West of England on 12 July 2010. It includes memories of many of the people who were involved.

*A 15-minute animated short film called ''The Incredible Journey'' produced with the University of the West of England

The University of the West of England (also known as UWE Bristol) is a public research university, located in and around Bristol, England.

The institution was know as the Bristol Polytechnic in 1970; it received university status in 1992 and ...

tells the story of the ship's return to Bristol from the Falklands in 1970.

* In 2015 it was announced that the new British passport would include an image of the SS ''Great Britain'' on a page of Iconic Innovations.

*The Living TV

Sky Witness is a British pay television channel owned and operated by Sky, a division of Comcast. The channel primarily broadcasts drama shows from the United States, aimed at the 18–45 age group. An Italian version of Sky Witness, named S ...

series ''Most Haunted

''Most Haunted'' is a British paranormal reality television series. Following complaints, the broadcast regulator, Ofcom, ruled that it was an entertainment show, not a legitimate investigation into the paranormal, and "should not be taken ser ...

'' went on the ship in 2009.

Dimensions

*Length: *Beam (width): *Height (main deck to keel): *Weight unladen: *Displacement: Engine *Rated horsepower: *Weight: *Cylinders: 4 x inverted 'V' bore *Stroke: *Pressure: *RPM: Max. 20rpm

Revolutions per minute (abbreviated rpm, RPM, rev/min, r/min, or with the notation min−1) is a unit of rotational speed or rotational frequency for rotating machines.

Standards

ISO 80000-3:2019 defines a unit of rotation as the dimensionl ...

*Main crankshaft: long and diameter

Propeller

*Diameter:

*Weight:

*Speed: 55 rpm

Other data

*Fuel capacity: of coal

*Water capacity:

*Cargo capacity:

*Cost of construction: £117,295

See also

* *Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

Official website

''Australian Town and Country Journal'', 31 December 1870, p. 17, at

Trove

Trove is an Australian online library database owned by the National Library of Australia in which it holds partnerships with source providers National and State Libraries Australia, an aggregator and service which includes full text documen ...

BBC Chronicle 1970 – The Great Iron Ship – SS ''Great Britain'' Rescue

{{DEFAULTSORT:Great Britain, SS Ships built in Bristol Bristol Harbourside Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmarks Museum ships in the United Kingdom Passenger ships of the United Kingdom Steamships of the United Kingdom

SS Great Britain

SS ''Great Britain'' is a museum ship and former passenger steamship that was advanced for her time. She was the largest passenger ship in the world from 1845 to 1854. She was designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–1859), for the Great We ...

Victorian-era merchant ships of the United Kingdom

SS Great Britain

SS ''Great Britain'' is a museum ship and former passenger steamship that was advanced for her time. She was the largest passenger ship in the world from 1845 to 1854. She was designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–1859), for the Great We ...

Ships designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Museums in Bristol

Coal hulks

1843 ships

Ships and vessels of the National Historic Fleet

Shipwrecks of the Falkland Islands

1843 establishments in England

Maritime incidents in October 1846

Maritime incidents in December 1863

Maritime incidents in May 1886