SMS Goeben on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

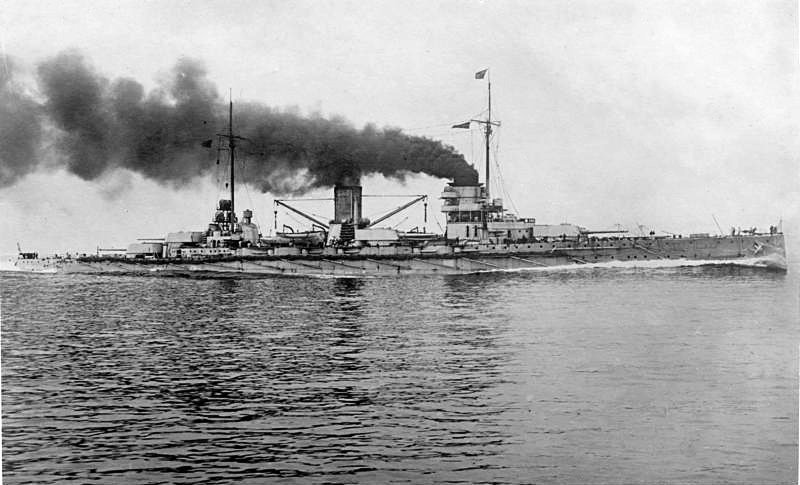

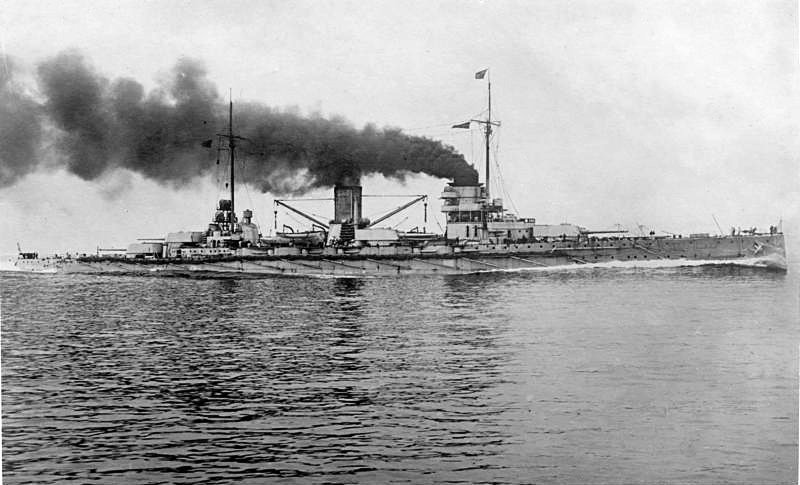

SMS was the second of two s of the

The Imperial Navy ordered , the third German battlecruiser, on 8 April 1909 under the provisional name "H" from the

The Imperial Navy ordered , the third German battlecruiser, on 8 April 1909 under the provisional name "H" from the

Souchon's two ships departed Messina early on 6 August through the southern entrance to the strait and headed for the eastern Mediterranean. The two British battlecruisers were 100 miles away, while a third, , was coaling in

Souchon's two ships departed Messina early on 6 August through the southern entrance to the strait and headed for the eastern Mediterranean. The two British battlecruisers were 100 miles away, while a third, , was coaling in

On 29 October bombarded

On 29 October bombarded

On 25 April, the same day the Allies landed at Gallipoli, Russian naval forces arrived off the Bosphorus and bombarded the forts guarding the strait. Two days later headed south to the Dardanelles to bombard Allied troops at Gallipoli, accompanied by the

On 25 April, the same day the Allies landed at Gallipoli, Russian naval forces arrived off the Bosphorus and bombarded the forts guarding the strait. Two days later headed south to the Dardanelles to bombard Allied troops at Gallipoli, accompanied by the

Admiral Souchon sent ''Yavuz'' to Zonguldak on 8 January to protect an approaching empty collier from Russian destroyers in the area, but the Russians sank the transport ship before ''Yavuz'' arrived. On the return trip to the Bosphorus, ''Yavuz'' encountered ''Imperatritsa Ekaterina''. The two ships

Admiral Souchon sent ''Yavuz'' to Zonguldak on 8 January to protect an approaching empty collier from Russian destroyers in the area, but the Russians sank the transport ship before ''Yavuz'' arrived. On the return trip to the Bosphorus, ''Yavuz'' encountered ''Imperatritsa Ekaterina''. The two ships

On 20 January 1918, and left the Dardanelles under the command of Vice Admiral Rebeur-Paschwitz, who had replaced Souchon the previous September. Rebeur-Paschwitz's intention was to draw Allied naval forces away from Palestine in support of Turkish forces there. Outside the straits, in the course of what became known as the

On 20 January 1918, and left the Dardanelles under the command of Vice Admiral Rebeur-Paschwitz, who had replaced Souchon the previous September. Rebeur-Paschwitz's intention was to draw Allied naval forces away from Palestine in support of Turkish forces there. Outside the straits, in the course of what became known as the

Over the course of the refit, the mine damage was repaired, her displacement was increased to , and the hull was slightly reworked. She was reduced in length by a half meter but her beam increased by . was equipped with new boilers and a French fire control system for her main battery guns. Two of the 15 cm guns were removed from their casemate positions. Her armor protection was not upgraded to take the lessons of the

Over the course of the refit, the mine damage was repaired, her displacement was increased to , and the hull was slightly reworked. She was reduced in length by a half meter but her beam increased by . was equipped with new boilers and a French fire control system for her main battery guns. Two of the 15 cm guns were removed from their casemate positions. Her armor protection was not upgraded to take the lessons of the

Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy () was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defence. Wilhel ...

, launched in 1911 and named after the German Franco-Prussian War veteran General August Karl von Goeben

August Karl Friedrich Christian von Goeben (10 December 181613 November 1880), was a Prussian infantry general, who won the Iron Cross for his service in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71.

Early career

Born at Stade 30 km west of Hambu ...

. Along with her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

, was similar to the previous German battlecruiser design, , but larger, with increased armor protection and two more main guns in an additional turret

Turret may refer to:

* Turret (architecture), a small tower that projects above the wall of a building

* Gun turret, a mechanism of a projectile-firing weapon

* Objective turret, an indexable holder of multiple lenses in an optical microscope

* M ...

. and were significantly larger and better armored than the comparable British .

Several months after her commissioning in 1912, , with the light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to th ...

, formed the German Mediterranean Division and patrolled there during the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars refers to a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan States in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan States of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and def ...

. After the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

on 28 July 1914, and bombarded French positions in North Africa and then evaded British naval forces in the Mediterranean and reached Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. The two ships were transferred to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

on 16 August 1914, and became the flagship of the Ottoman Navy as , usually shortened to . By bombarding Russian facilities in the Black Sea, she brought Turkey into World War I on the German side. The ship operated primarily against Russian forces in the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

during the war, including several inconclusive engagements with Russian battleship

A battleship is a large armour, armored warship with a main artillery battery, battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1 ...

s. She made a sortie into the Aegean in January 1918 that resulted in the Battle of Imbros

The Battle of Imbros was a naval action that took place during the First World War. The battle occurred on 20 January 1918 when an Ottoman squadron engaged a flotilla of the British Royal Navy off the island of Imbros in the Aegean Sea. A lac ...

, where sank a pair of British monitors

Monitor or monitor may refer to:

Places

* Monitor, Alberta

* Monitor, Indiana, town in the United States

* Monitor, Kentucky

* Monitor, Oregon, unincorporated community in the United States

* Monitor, Washington

* Monitor, Logan County, West ...

but was herself badly damaged by mines.

In 1936 she was officially renamed TCG ("Ship of the Turkish Republic "); she carried the remains of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or Mustafa Kemal Pasha until 1921, and Ghazi Mustafa Kemal from 1921 Surname Law (Turkey), until 1934 ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish Mareşal (Turkey), field marshal, Turkish National Movement, re ...

from Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

to İzmit

İzmit () is a district and the central district of Kocaeli province, Turkey. It is located at the Gulf of İzmit in the Sea of Marmara, about east of Istanbul, on the northwestern part of Anatolia.

As of the last 31/12/2019 estimation, the ...

in 1938. remained the flagship of the Turkish Navy

The Turkish Naval Forces ( tr, ), or Turkish Navy ( tr, ) is the naval warfare service branch of the Turkish Armed Forces.

The modern naval traditions and customs of the Turkish Navy can be traced back to 10 July 1920, when it was establis ...

until she was decommissioned in 1950. She was scrapped in 1973, after the West German government declined an invitation to buy her back from Turkey. She was the last surviving ship built by the Imperial German Navy, and the longest-serving dreadnought

The dreadnought (alternatively spelled dreadnaught) was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her ...

-type ship in any navy.

Design

As the German (Imperial Navy) continued in itsarms race

An arms race occurs when two or more groups compete in military superiority. It consists of a competition between two or more states to have superior armed forces; a competition concerning production of weapons, the growth of a military, and ...

with the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

in 1907, the (Imperial Navy Office) considered plans for the battlecruiser that was to be built for the following year. An increase in the budget raised the possibility of increasing the caliber of the main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

from the guns used in the previous battlecruiser, , to , but Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz

Alfred Peter Friedrich von Tirpitz (19 March 1849 – 6 March 1930) was a German grand admiral, Secretary of State of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the German Imperial Navy from 1897 until 1916. Prussi ...

, the State Secretary of the Navy, opposed the increase, preferring to add a pair of 28 cm guns instead. The Construction Department supported the change, and ultimately two ships were authorized for the 1908 and 1909 building years; was the first, followed by .

was long overall, with a beam of and a draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vesse ...

of fully loaded. The ship displaced normally, and at full load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

. was powered by four Parsons

Parsons may refer to:

Places

In the United States:

* Parsons, Kansas, a city

* Parsons, Missouri, an unincorporated community

* Parsons, Tennessee, a city

* Parsons, West Virginia, a town

* Camp Parsons, a Boy Scout camp in the state of Washingt ...

steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam tu ...

s, with steam provided by twenty-four coal-fired Schulz-Thornycroft water-tube boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by the fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-gen ...

s. The propulsion system was rated at and a top speed of , though she exceeded this speed significantly on her trials. At , the ship had a range of . Her crew consisted on 43 officers and 1,010 enlisted men.

The ship was armed with a main battery of ten SK L/50 guns mounted in five twin-gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanis ...

s; of these, one was placed forward, two were ''en echelon

An echelon formation () is a (usually military) formation in which its units are arranged diagonally. Each unit is stationed behind and to the right (a "right echelon"), or behind and to the left ("left echelon"), of the unit ahead. The name of ...

'' amidships

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water (mostly though not necessarily on the sea). Some remain current, while many date from the 17t ...

, and the other two were in a superfiring pair aft. Her secondary armament

Secondary armament is a term used to refer to smaller, faster-firing weapons that were typically effective at a shorter range than the main (heavy) weapons on military systems, including battleship- and cruiser-type warships, tanks/armored p ...

consisted of twelve SK L/45 guns placed in individual casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to antiquity, the term "casemate wall" me ...

s in the central portion of the ship. For defense against torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s, she carried twelve SK L/45 guns, also in individual mounts in the bow, the stern, and around the forward conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armored, from which an officer in charge can conn the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for the ship's engine, rudder, lines, and gro ...

. She was also equipped with four submerged torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, one in the bow, one in the stern, and one on each broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

.

The ship's armor consisted of Krupp cemented steel. The belt

Belt may refer to:

Apparel

* Belt (clothing), a leather or fabric band worn around the waist

* Championship belt, a type of trophy used primarily in combat sports

* Colored belts, such as a black belt or red belt, worn by martial arts practiti ...

was thick in the citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

In ...

where it covered the ship's ammunition magazines

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combination ...

and propulsion machinery spaces. The belt tapered down to on either end. The deck was thick, sloping downward at the side to connect to the bottom edge of the belt. The main battery gun turrets had faces, and they sat atop barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protectio ...

s that were equally thick.

Service history

The Imperial Navy ordered , the third German battlecruiser, on 8 April 1909 under the provisional name "H" from the

The Imperial Navy ordered , the third German battlecruiser, on 8 April 1909 under the provisional name "H" from the Blohm & Voss

Blohm+Voss (B+V), also written historically as Blohm & Voss, Blohm und Voß etc., is a German shipbuilding and engineering company. Founded in Hamburg in 1877 to specialise in steel-hulled ships, its most famous product was the World War II battl ...

shipyard in Hamburg, under construction number 201. Her keel was laid on 19 August; the hull was completed and the ship was launched on 28 March 1911. Fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

work followed, and she was commissioned into the German Navy on 2 July 1912.

When the First Balkan War

The First Balkan War ( sr, Први балкански рат, ''Prvi balkanski rat''; bg, Балканска война; el, Αʹ Βαλκανικός πόλεμος; tr, Birinci Balkan Savaşı) lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and invo ...

broke out in October 1912, the German General Staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (german: Großer Generalstab), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the German Army, responsible for the continuou ...

determined that a naval Mediterranean Division () was needed to project German power in the Mediterranean, and thus dispatched and the light cruiser to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. The two ships left Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the Jutland ...

on 4 November and arrived on 15 November 1912. Beginning in April 1913, visited many Mediterranean ports including Venice, Pola, and Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

, before sailing into Albanian waters. Following this trip, returned to Pola and remained there from 21 August to 16 October for maintenance.

On 29 June 1913, the Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 ( O.S.) / 29 (N.S.) June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies ...

broke out and the Mediterranean Division was retained in the area. On 23 October 1913, (Rear Admiral) Wilhelm Souchon

Wilhelm Anton Souchon (; 2 June 1864 – 13 January 1946) was a German admiral in World War I. Souchon commanded the ''Kaiserliche Marine''s Mediterranean squadron in the early days of the war. His initiatives played a major part in the entry o ...

assumed command of the squadron. and continued their activities in the Mediterranean, and visited some 80 ports before the outbreak of World War I. The navy made plans to replace with her sister

A sister is a woman or a girl who shares one or more parents with another individual; a female sibling. The male counterpart is a brother. Although the term typically refers to a family, familial relationship, it is sometimes used endearingly to r ...

, but the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated on 28 June 1914 by Bosnian Serb student Gavrilo Princip. They were shot at close range wh ...

in Sarajevo, Bosnia, on 28 June 1914 and the subsequent rise in tensions between the Great Powers made this impossible. After the assassination, Souchon assessed that war was imminent between the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in W ...

and the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

, and ordered his ships to make for Pola for repairs. Engineers came from Germany to work on the ship. had 4,460 boiler tubes replaced, among other repairs. Upon completion, the ships departed for Messina.

World War I

Pursuit of and

Kaiser Wilhelm II had ordered that in the event of war, and should either conduct raids in the western Mediterranean to prevent the return of French troops from North Africa to Europe, or break out into the Atlantic and attempt to return to German waters, on the squadron commander's discretion. On 3 August 1914, the two ships were en route to Algeria when Souchon received word of the declaration of war against France. bombardedPhilippeville

Philippeville (; wa, Flipveye) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Namur, Belgium. The Philippeville municipality includes the former municipalities of Fagnolle, Franchimont, Jamagne, Jamiolle, Merlemont, ...

, French Algeria

French Algeria (french: Alger to 1839, then afterwards; unofficially , ar, الجزائر المستعمرة), also known as Colonial Algeria, was the period of French colonisation of Algeria. French rule in the region began in 1830 with the ...

, for about 10 minutes early on 3 August while shelled nearby Bône

Annaba ( ar, عنّابة, "Place of the Jujubes"; ber, Aânavaen), formerly known as Bon, Bona and Bône, is a seaport city in the northeastern corner of Algeria, close to the border with Tunisia. Annaba is near the small Seybouse River ...

, in accordance with the Kaiser's order. Tirpitz and Admiral Hugo von Pohl then transmitted secret orders to Souchon instructing him to sail to Constantinople, in direct contravention of the Kaiser's instructions and without his knowledge.

Since could not reach Constantinople without coaling, Souchon headed for Messina. The Germans encountered the British battlecruisers and , but Germany was not yet at war with Britain and neither side opened fire. The British turned to follow and , but the German ships were able to outrun the British, and arrived in Messina by 5 August. Refueling in Messina was complicated by the declaration of Italian neutrality on 2 August. Under international law, combatant ships were permitted only 24 hours in a neutral port. Sympathetic Italian naval authorities in the port allowed and to remain in port for around 36 hours while the ships coaled from a German collier. Despite the additional time, s fuel stocks were not sufficient to permit the voyage to Constantinople, so Souchon arranged to rendezvous with another collier in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi ( Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

. The French fleet remained in the western Mediterranean, since the French naval commander in the Mediterranean, Admiral Lapeyrère, was convinced the Germans would either attempt to escape to the Atlantic or join the Austrians in Pola.

Souchon's two ships departed Messina early on 6 August through the southern entrance to the strait and headed for the eastern Mediterranean. The two British battlecruisers were 100 miles away, while a third, , was coaling in

Souchon's two ships departed Messina early on 6 August through the southern entrance to the strait and headed for the eastern Mediterranean. The two British battlecruisers were 100 miles away, while a third, , was coaling in Bizerta

Bizerte or Bizerta ( ar, بنزرت, translit=Binzart , it, Biserta, french: link=no, Bizérte) the classical Hippo, is a city of Bizerte Governorate in Tunisia. It is the northernmost city in Africa, located 65 km (40mil) north of the cap ...

, Tunisia. The only British naval force in Souchon's way was the 1st Cruiser Squadron, which consisted of the four armored cruisers

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

, , and under the command of Rear Admiral Ernest Troubridge. The Germans headed initially towards the Adriatic in a feint

Feint is a French term that entered English via the discipline of swordsmanship and fencing. Feints are maneuvers designed to distract or mislead, done by giving the impression that a certain maneuver will take place, while in fact another, or e ...

; the move misled Troubridge, who sailed to intercept them in the mouth of the Adriatic. After realizing his mistake, Troubridge reversed course and ordered the light cruiser and two destroyers to launch a torpedo attack on the Germans. s lookouts spotted the ships, and in the darkness, she and evaded their pursuers undetected. Troubridge broke off the chase early on 7 August, convinced that any attack by his four older armored cruisers against —armed with her larger 28 cm guns—would be suicidal. Souchon's journey to Constantinople was now clear.

refilled her coal bunkers off the island of Donoussa near Naxos

Naxos (; el, Νάξος, ) is a Greek island and the largest of the Cyclades. It was the centre of archaic Cycladic culture. The island is famous as a source of emery, a rock rich in corundum, which until modern times was one of the best ab ...

. During the afternoon of 10 August, the two ships entered the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

. They were met by an Ottoman picket boat

A picket boat is a type of small naval craft. These are used for harbor patrol and other close inshore work, and have often been carried by larger warships as a ship's boat. They range in size between 30 and 55 feet.

Patrol boats, or any craft en ...

, which guided them through to the Sea of Marmara

The Sea of Marmara,; grc, Προποντίς, Προποντίδα, Propontís, Propontída also known as the Marmara Sea, is an inland sea located entirely within the borders of Turkey. It connects the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea via t ...

. To circumvent neutrality requirements, the Ottoman government

The Ottoman Empire developed over the years as a despotism with the Sultan as the supreme ruler of a centralized government that had an effective control of its provinces, officials and inhabitants. Wealth and rank could be inherited but were j ...

proposed that the ships be transferred to its ownership "by means of a fictitious sale." Before the Germans could approve this, the Ottomans announced on 11 August that they had purchased the ships for 80 million Marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks, trademarks owned by an organisation for the benefit of its members

* Marks & Co, the inspiration for the novel ...

. In a formal ceremony the two ships were commissioned in the Ottoman Navy on 16 August. On 23 September, Souchon accepted an offer to command the Turkish fleet. was renamed and was renamed ; their German crews donned Ottoman uniforms and fezzes.

Black Sea operations

= 1914

= On 29 October bombarded

On 29 October bombarded Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

in her first operation against Imperial Russia, though the Ottoman Empire was not yet at war with the Entente; Souchon conducted the operation to force Turkey into the war on the side of Germany. A shell struck the ship in the aft

"Aft", in nautical terminology, is an adjective or adverb meaning towards the stern (rear) of the ship, aircraft or spacecraft, when the frame of reference is within the ship, headed at the fore. For example, "Able Seaman Smith; lie aft!" or "Wh ...

er funnel, but it failed to detonate and did negligible damage. Two other hits inflicted minor damage. The ship and her escorts passed through an inactive Russian minefield during the bombardment. As she returned to Turkish waters, came across the Russian minelayer which scuttled herself with 700 mines on board. During the engagement the escorting Russian destroyer was damaged by two of s secondary battery shells. In response to the bombardment, Russia declared war on 1 November, thus forcing the Ottomans into the wider world war. France and Great Britain bombarded the Turkish fortresses guarding the Dardanelles on 3 November and formally declared war two days later. From this engagement, the Russians drew the conclusion that the entire Black Sea Fleet

Chernomorskiy flot

, image = Great emblem of the Black Sea fleet.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Great emblem of the Black Sea fleet

, dates = May 13, ...

would have to remain consolidated so it could not be defeated in detail (one ship at a time) by .

, escorted by , intercepted the Russian Black Sea Fleet off the Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a p ...

n coastline on 18 November as it returned from a bombardment of Trebizond. Despite the noon hour the conditions were foggy and none of the capital ships were spotted initially. The Black Sea Fleet had experimented with concentrating fire from several ships under the control of one "master" ship before the war, and held her fire until , the master ship, could see . When the gunnery commands were finally received they showed a range over in excess of s own estimate of , so opened fire using her own data before turned to fire her broadside. She scored a hit with her first salvo as a 12-inch shell partially penetrated the armor casemate protecting one of s secondary guns. It detonated some of the ready-use ammunition, starting a fire that filled the casemate and killed the entire gun crew. A total of thirteen men were killed and three were wounded.

returned fire and hit in the middle funnel; the shell detonated after it passed through the funnel and destroyed the antennae for the fire-control radio, so that could not correct s inaccurate range data. The other Russian ships either used s incorrect data or never saw and failed to register any hits. hit four more times, although one shell failed to detonate, before Souchon decided to break contact after 14 minutes of combat. The four hits out of nineteen shells fired killed 34 men and wounded 24.

The following month, on 5–6 December, and provided protection for troop transports, and on 10 December, bombarded Batum

Batumi (; ka, ბათუმი ) is the second largest city of Georgia and the capital of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, located on the coast of the Black Sea in Georgia's southwest. It is situated in a subtropical zone at the foot of t ...

. On 23 December, and the protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of naval cruiser of the late-19th century, gained their description because an armoured deck offered protection for vital machine-spaces from fragments caused by shells exploding above them. Protected cruisers re ...

escorted three transports to Trebizond. While returning from another transport escort operation on 26 December, struck a mine that exploded beneath the conning tower, on the starboard side, about one nautical mile outside the Bosphorus

The Bosporus Strait (; grc, Βόσπορος ; tr, İstanbul Boğazı 'Istanbul strait', colloquially ''Boğaz'') or Bosphorus Strait is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul in northwestern Tu ...

. The explosion tore a hole in the ship's hull, but the torpedo bulkhead held. Two minutes later, struck a second mine on the port side, just forward of the main battery wing barbette; this tore open a hole. The bulkhead bowed in but retained watertight protection of the ship's interior. However, some 600 tons of water flooded the ship. There was no dock in the Ottoman Empire large enough to service , so temporary repairs were effected inside steel cofferdam

A cofferdam is an enclosure built within a body of water to allow the enclosed area to be pumped out. This pumping creates a dry working environment so that the work can be carried out safely. Cofferdams are commonly used for construction or re ...

s, which were pumped out to create a dry work area around the damaged hull. The holes were patched with concrete, which held for several years before more permanent work was necessary.

= 1915

= Still damaged, sortied from the Bosphorus on 28 January and again on 7 February 1915 to help escape the Russian fleet; she also covered the return of . then underwent repair work to the mine damage until May. On 1 April, with repairs incomplete, left the Bosphorus in company with to cover the withdrawal of and the protected cruiser , which had been sent to bombard Odessa. Strong currents, however, forced the cruisers east to the approaches of the Dnieper-Bug Liman (bay) that led to Nikolayev. As they sailed west after a course correction, struck a mine and sank, so this attack had to be aborted. After and appeared off Sevastopol and sank two cargo steamers, the Russian fleet chased them all day, and detached several destroyers after dusk to attempt a torpedo attack. Only one destroyer, , was able to close the distance and launch an attack, which missed. and returned to the Bosphorus unharmed. On 25 April, the same day the Allies landed at Gallipoli, Russian naval forces arrived off the Bosphorus and bombarded the forts guarding the strait. Two days later headed south to the Dardanelles to bombard Allied troops at Gallipoli, accompanied by the

On 25 April, the same day the Allies landed at Gallipoli, Russian naval forces arrived off the Bosphorus and bombarded the forts guarding the strait. Two days later headed south to the Dardanelles to bombard Allied troops at Gallipoli, accompanied by the pre-dreadnought battleship

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built between the mid- to late- 1880s and 1905, before the launch of in 1906. The pre-dreadnought ships replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s. Built from steel, protec ...

. They were spotted at dawn from a kite balloon as they were getting into position. When the first round from the dreadnought

The dreadnought (alternatively spelled dreadnaught) was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her ...

landed close by, moved out of firing position, close to the cliffs, where ''Queen Elizabeth'' could not engage her. On 30 April tried again, but was spotted from the pre-dreadnought which had moved into the Dardanelles to bombard the Turkish headquarters at Çanakkale. The British ship only managed to fire five rounds before moved out of her line of sight.

On 1 May, sailed to the Bay of Beikos in the Bosphorus after the Russian fleet bombarded the fortifications at the mouth of the Bosphorus. Around 7 May, sortied from the Bosphorus in search of Russian ships as far as Sevastopol, but found none. Running short on main gun ammunition, she did not bombard Sevastopol. While returning on the morning of 10 May, s lookouts spotted two Russian pre-dreadnoughts, and , and she opened fire. Within the first ten minutes she had been hit twice, although she was not seriously damaged. Admiral Souchon disengaged and headed for the Bosphorus, pursued by Russian light forces. Later that month two of the ship's 15 cm guns were taken ashore for use there, and the four 8.8 cm guns in the aft superstructure were removed at the same time. Four 8.8 cm anti-aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based ...

were installed on the aft superstructure by the end of 1915.

On 18 July, struck a mine; the ship took on some of water and was no longer able to escort coal convoys from Zonguldak

Zonguldak () is a city and the capital of Zonguldak Province in the Black Sea region of Turkey. It was established in 1849 as a port town for the nearby coal mines in Ereğli and the coal trade remains its main economic activity. According to the ...

to the Bosphorus. was assigned to the task, and on 10 August she escorted a convoy of five coal transports, along with and three torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s. During transit, the convoy was attacked by the Russian submarine , which sank one of the colliers. The following day, and another submarine tried to attack as well, though they were unable to reach a firing position. Two Russian destroyers, and , attacked a Turkish convoy escorted by and two torpedo boats on 5 September. s guns broke down during combat, and the Turks summoned , but she arrived too late: the Turkish colliers had already been beached to avoid capture by the Russian destroyers.

On 21 September, was again sent out of the Bosphorus to drive off three Russian destroyers which had been attacking Turkish coal ships. Escort missions continued until 14 November, when the submarine nearly hit with two torpedoes just outside the Bosphorus. Admiral Souchon decided the risk to the battlecruiser was too great, and suspended the convoy system. In its stead, only those ships fast enough to make the journey from Zonguldak to Constantinople in a single night were permitted; outside the Bosphorus they would be met by torpedo boats to defend them against the lurking submarines. By the end of the summer, the completion of two new Russian dreadnought battleships, and , further curtailed s activities.

= 1916–1917

= Admiral Souchon sent ''Yavuz'' to Zonguldak on 8 January to protect an approaching empty collier from Russian destroyers in the area, but the Russians sank the transport ship before ''Yavuz'' arrived. On the return trip to the Bosphorus, ''Yavuz'' encountered ''Imperatritsa Ekaterina''. The two ships

Admiral Souchon sent ''Yavuz'' to Zonguldak on 8 January to protect an approaching empty collier from Russian destroyers in the area, but the Russians sank the transport ship before ''Yavuz'' arrived. On the return trip to the Bosphorus, ''Yavuz'' encountered ''Imperatritsa Ekaterina''. The two ships engaged

An engagement or betrothal is the period of time between the declaration of acceptance of a marriage proposal and the marriage itself (which is typically but not always commenced with a wedding). During this period, a couple is said to be ''fi ...

in a brief artillery duel, beginning at a range of 18,500 meters. ''Yavuz'' turned to the southwest, and in the first four minutes of the engagement, fired five salvos from her main guns. Neither ship scored any hits, though shell splinters from near misses struck ''Yavuz''. This was the only battle between dreadnoughts on the Black Sea to ever occur. Though nominally much faster than ''Imperatritsa Ekaterina'', the Turkish battlecruiser's bottom was badly fouled and her propeller shafts were in poor condition. This made it difficult for ''Yavuz'' to escape from the powerful Russian battleship, which was reported to have reached .

Russian forces were making significant gains into Ottoman territory during the Caucasus Campaign

The Caucasus campaign comprised armed conflicts between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire, later including Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus, the German Empire, the Central Caspian Dict ...

. In an attempt to prevent further advances by the Russian army, ''Yavuz'' rushed 429 officers and men, a mountain artillery battery, machine gun and aviation units, 1,000 rifles, and 300 cases of munitions to Trebizond on 4 February. On 4 March, the Russian navy landed a detachment of some 2,100 men, along with mountain guns and horses, on either side of the port of Atina. The Turks were caught by surprise and forced to evacuate. Another landing took place at Kavata Bay, some 5 miles east of Trebizond, in June. In late June, the Turks counterattacked and penetrated around 20 miles into the Russian lines. ''Yavuz'' and ''Midilli'' conducted a series of coastal operations to support the Turkish attacks. On 4 July, ''Yavuz'' shelled the port of Tuapse

Tuapse (russian: Туапсе́; ady, Тӏуапсэ ) is a town in Krasnodar Krai, Russia, situated on the northeast shore of the Black Sea, south of Gelendzhik and north of Sochi. Population:

Tuapse is a sea port and the northern center of ...

, where she sank a steamer and a motor schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoo ...

. The Turkish ships sailed northward to circle back behind the Russians before the two Russian dreadnoughts left Sevastopol to try to attack them. They then returned to the Bosphorus, where ''Yavuz'' was docked for repairs to her propeller shaft

A drive shaft, driveshaft, driving shaft, tailshaft (Australian English), propeller shaft (prop shaft), or Cardan shaft (after Girolamo Cardano) is a component for transmitting mechanical power and torque and rotation, usually used to connect ...

s until September.

The coal shortage continued to worsen until Admiral Souchon was forced to suspend operations by ''Yavuz'' and ''Midilli'' through 1917. Early on 10 July 1917, a Royal Naval Air Service Handley Page Type O

The Handley Page Type O was a biplane bomber used by Britain during the First World War. When built, the Type O was the largest aircraft that had been built in the UK and one of the largest in the world. There were two main variants, the Handl ...

bomber, flying from Moudros

Moudros ( el, Μούδρος) is a town and a former municipality on the island of Lemnos, North Aegean, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Lemnos, of which it is a municipal unit. It covers the entire eas ...

, Greece, tried to bomb from with eight bombs. It missed but instead sank the destroyer , the largest ship sunk by air during the First World War. After an armistice between Russia and the Ottoman Empire was signed in December 1917 following the Bolshevik revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

, formalized in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russia and the Central Powers ( Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russi ...

in March 1918, coal started to arrive again from eastern Turkey.

= 1918

= On 20 January 1918, and left the Dardanelles under the command of Vice Admiral Rebeur-Paschwitz, who had replaced Souchon the previous September. Rebeur-Paschwitz's intention was to draw Allied naval forces away from Palestine in support of Turkish forces there. Outside the straits, in the course of what became known as the

On 20 January 1918, and left the Dardanelles under the command of Vice Admiral Rebeur-Paschwitz, who had replaced Souchon the previous September. Rebeur-Paschwitz's intention was to draw Allied naval forces away from Palestine in support of Turkish forces there. Outside the straits, in the course of what became known as the Battle of Imbros

The Battle of Imbros was a naval action that took place during the First World War. The battle occurred on 20 January 1918 when an Ottoman squadron engaged a flotilla of the British Royal Navy off the island of Imbros in the Aegean Sea. A lac ...

, surprised and sank the monitors

Monitor or monitor may refer to:

Places

* Monitor, Alberta

* Monitor, Indiana, town in the United States

* Monitor, Kentucky

* Monitor, Oregon, unincorporated community in the United States

* Monitor, Washington

* Monitor, Logan County, West ...

and which were at anchor and unsupported by the pre-dreadnoughts that should have been guarding them. Rebeur-Paschwitz then decided to proceed to the port of Mudros

Moudros ( el, Μούδρος) is a town and a former municipality on the island of Lemnos, North Aegean, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Lemnos, of which it is a municipal unit. It covers the entire eas ...

; there the British pre-dreadnought battleship was raising steam to attack the Turkish ships. While en route, struck several mines and sank; hit three mines as well. Retreating to the Dardanelles and pursued by the British destroyers and , she was intentionally beached near Nagara Point Nara Burnu ( Turkish "Cape Nara"), formerly Nağara Burnu, in English Nagara Point, and in older sources Point Pesquies, is a headland on the Anatolian side of the Dardanelles Straits, north of Çanakkale.

It is the narrowest and, with , the deepe ...

just outside the Dardanelles. The British attacked with bombers from No. 2 Wing of the Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British Army's Royal Flying Corps t ...

while she was grounded and hit her twice, but the bombs from the light aircraft were not heavy enough to do any serious damage. The monitor attempted to shell on the evening of 24 January, but only managed to fire ten rounds before withdrawing to escape the Turkish artillery fire. The submarine was sent to destroy the damaged ship, but was too late; the old ex-German pre-dreadnought had towed off and returned her to the safety of Constantinople. was crippled by the extensive damage; cofferdams were again built around the hull, and repairs lasted from 7 August to 19 October.

Before the repair work was carried out, escorted the members of the Ottoman Armistice Commission to Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

on 30 March 1918, after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed. After returning to Constantinople she sailed in May to Sevastopol where she had her hull cleaned and some leaks repaired. and several destroyers sailed for Novorossiysk

Novorossiysk ( rus, Новоросси́йск, p=nəvərɐˈsʲijsk; ady, ЦIэмэз, translit=Chəməz, p=t͡sʼɜmɜz) is a city in Krasnodar Krai, Russia. It is one of the largest ports on the Black Sea. It is one of the few cities hono ...

on 28 June to intern the remaining Soviet warships, but they had already been scuttled when the Turkish ships arrived. The destroyers remained, but returned to Sevastopol. On 14 July the ship was laid up

A reserve fleet is a collection of naval vessels of all types that are fully equipped for service but are not currently needed; they are partially or fully decommissioned. A reserve fleet is informally said to be "in mothballs" or "mothballed"; a ...

for the rest of the war. While in Sevastopol, dockyard workers scraped fouling from the ship's bottom. subsequently returned to Constantinople, where from 7 August to 19 October a concrete cofferdam was installed to repair one of the three areas damaged by mines.

The German navy formally transferred ownership of the vessel to the Turkish government on 2 November. According to the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres (french: Traité de Sèvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

between the Ottoman Empire and the Western Allies, was to have been handed over to the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

as war reparations, but this was not done due to the Turkish War of Independence

The Turkish War of Independence "War of Liberation", also known figuratively as ''İstiklâl Harbi'' "Independence War" or ''Millî Mücadele'' "National Struggle" (19 May 1919 – 24 July 1923) was a series of military campaigns waged by th ...

, which broke out immediately after World War I ended, as Greece attempted to seize territory from the crumbling Ottoman Empire. After modern Turkey emerged from the war victorious, the Treaty of Sèvres was discarded and the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the confl ...

was signed in its place in 1923. Under this treaty, the new Turkish republic retained possession of much of its fleet, including .

Post-war service

During the 1920s, a commitment to refurbish as the centerpiece of the new country's fleet was the only constant element of the various naval policies which were put forward. The battlecruiser remained inİzmit

İzmit () is a district and the central district of Kocaeli province, Turkey. It is located at the Gulf of İzmit in the Sea of Marmara, about east of Istanbul, on the northwestern part of Anatolia.

As of the last 31/12/2019 estimation, the ...

until 1926, in a neglected state: only two of her boilers worked, she could not steer or steam, and she still had two unrepaired scars from the mine damage in 1918. Enough money was raised to allow the purchase of a new floating dock from Germany, as could not be towed anywhere without risk of her sinking in rough seas. The French company Atelier et Chantiers de St. Nazaire-Penhöet was contracted in December 1926 to oversee the subsequent refit, which was carried out by the Gölcük Naval Shipyard. Work proceeded over three years (1927–1930); it was delayed when several compartments of the dock collapsed while being pumped out. was slightly damaged before she could be refloated and the dock had to be repaired before the repair work could begin. The Minister of Marine, Ihsan Bey (İhsan Eryavuz), was convicted of embezzlement in the resulting investigation. Other delays were caused by fraud charges which resulted in the abolition of the Ministry of Marine. The Turkish Military's Chief of Staff, Marshal Fevzi, opposed naval construction and slowed down all naval building programs following the fraud charges. Intensive work on the battlecruiser only began after the Greek Navy conducted a large-scale naval exercise off Turkey in September 1928 and the Turkish Government perceived a need to counter Greece's naval superiority. The Turks also ordered four destroyers and two submarines from Italian shipyards. The Greek Government proposed a 10-year "holiday" from naval building modeled on the Washington Treaty when it learned that was to be brought back into service, though it reserved the right to build two new cruisers. The Turkish Government rejected this proposal, and claimed that the ship was intended to counter the growing strength of the Soviet Navy in the Black Sea.

Over the course of the refit, the mine damage was repaired, her displacement was increased to , and the hull was slightly reworked. She was reduced in length by a half meter but her beam increased by . was equipped with new boilers and a French fire control system for her main battery guns. Two of the 15 cm guns were removed from their casemate positions. Her armor protection was not upgraded to take the lessons of the

Over the course of the refit, the mine damage was repaired, her displacement was increased to , and the hull was slightly reworked. She was reduced in length by a half meter but her beam increased by . was equipped with new boilers and a French fire control system for her main battery guns. Two of the 15 cm guns were removed from their casemate positions. Her armor protection was not upgraded to take the lessons of the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland (german: Skagerrakschlacht, the Battle of the Skagerrak) was a naval battle fought between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet, under Vice ...

into account, and she had only of armor above her magazines. was recommissioned in 1930, resuming her role as flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the ...

of the Turkish Navy, and performed better than expected in her speed trials; her subsequent gunnery and fire control trials were also successful. The four destroyers, which were needed to protect the battlecruiser, entered service between 1931 and 1932; their performance never met the design specifications. In response to s return to service, the Soviet Union transferred the battleship and light cruiser from the Baltic in late 1929 to ensure that the Black Sea Fleet retained parity with the Turkish Navy. The Greek Government also responded by ordering two destroyers.

In 1933, she took Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

İsmet İnönü

Mustafa İsmet İnönü (; 24 September 1884 – 25 December 1973) was a Turkish army officer and statesman of Kurdish descent, who served as the second President of Turkey from 11 November 1938 to 22 May 1950, and its Prime Minister three time ...

from Varna to Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

and carried the Shah of Iran

This is a list of monarchs of Persia (or monarchs of the Iranic peoples, in present-day Iran), which are known by the royal title Shah or Shahanshah. This list starts from the establishment of the Medes around 671 BCE until the deposition of th ...

from Trebizond to Samsun

Samsun, historically known as Sampsounta ( gr, Σαμψούντα) and Amisos (Ancient Greek: Αμισός), is a city on the north coast of Turkey and is a major Black Sea port. In 2021, Samsun recorded a population of 710,000 people. The cit ...

the following year. had her name officially shortened to in 1930 and then to in 1936. Another short refit was conducted in 1938, and in November that year she carried the remains of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or Mustafa Kemal Pasha until 1921, and Ghazi Mustafa Kemal from 1921 Surname Law (Turkey), until 1934 ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish Mareşal (Turkey), field marshal, Turkish National Movement, re ...

from Istanbul to İzmit. She and the other ships of the navy were considered outdated by the British Naval Attache by 1937, partly due to their substandard anti-aircraft armament, but in 1938 the Turkish government began planning to expand the force. Under these plans the surface fleet was to comprise two 10,000-ton cruisers and twelve destroyers. would be retained until the second cruiser was commissioned in 1945, and the navy expected to build a 23,000-ton ship between 1950 and 1960. The naval building program did not come about, as the foreign shipyards which were to build the ships concentrated on the needs of their own nations leading up to World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

remained in service throughout World War II. In November 1939 she and were the only capital ships in the Black Sea region, and ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energy ...

'' magazine reported that was superior to the Soviet ship because the latter was in poor condition. In 1941, her anti-aircraft battery was strengthened to four guns, ten guns, and four guns. These were later increased to twenty-two 40 mm guns and twenty-four 20 mm guns. On 5 April 1946, the American battleship , light cruiser , and destroyer arrived in Istanbul to return the remains of Turkish ambassador Münir Ertegün. greeted the ships in the Bosphorus, where she and ''Missouri'' exchanged 19-gun salutes.

After 1948, the ship was stationed in either İzmit or Gölcük. She was decommissioned from active service on 20 December 1950 and stricken

Stricken may refer to:

* "Stricken" (song), a 2005 song by Disturbed

* ''Stricken'' (2010 film), a 2010 American film directed by Matthew Sconce

* ''Stricken'' (2009 film), a 2009 Dutch drama film

* "Stricken", when a warship's name is removed ...

from the Navy register on 14 November 1954. When Turkey joined NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

in 1952, the ship was assigned the hull number

Hull number is a serial identification number given to a boat or ship. For the military, a lower number implies an older vessel. For civilian use, the HIN is used to trace the boat's history. The precise usage varies by country and type.

United ...

B70. The Turkish government offered to sell the ship to the West German government in 1963 as a museum ship

A museum ship, also called a memorial ship, is a ship that has been preserved and converted into a museum open to the public for educational or memorial purposes. Some are also used for training and recruitment purposes, mostly for the small numb ...

, but the offer was declined. Turkey sold the ship to M.K.E. Seyman in 1971 for scrapping

Scrap consists of recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap has monetary value, especially recovered me ...

. She was towed to the breakers on 7 June 1973, and the work was completed in February 1976. By the time of her disposal she was the last dreadnought in existence outside the United States. She was the last surviving ship built by the Imperial German Navy, and the longest-serving dreadnought-type ship in any navy.

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Goeben 1911 ships Moltke-class battlecruisers Ships built in Hamburg World War I battlecruisers of Germany World War I cruisers of the Ottoman Empire Maritime incidents in 1918