SMS Gneisenau on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SMS ''Gneisenau''). was an

The two ''Scharnhorst''-class cruisers were ordered as part of the naval construction program laid out in the Second Naval Law of 1900, which called for a force of fourteen

The two ''Scharnhorst''-class cruisers were ordered as part of the naval construction program laid out in the Second Naval Law of 1900, which called for a force of fourteen

''Gneisenau'' went into dry dock in Tsingtao for annual repairs in the first quarter of 1912. On 13 April, the ships embarked on a month-long cruise to Japanese waters, returning to Tsingtao on 13 May. In June, ''KzS'' Willi Brüninghaus relieved Uslar as ''Gneisenau''s commander. Over the course of 1–4 August, ''Gneisenau'' steamed to

''Gneisenau'' went into dry dock in Tsingtao for annual repairs in the first quarter of 1912. On 13 April, the ships embarked on a month-long cruise to Japanese waters, returning to Tsingtao on 13 May. In June, ''KzS'' Willi Brüninghaus relieved Uslar as ''Gneisenau''s commander. Over the course of 1–4 August, ''Gneisenau'' steamed to

The British had scant resources to oppose the German squadron off the coast of South America. Rear Admiral

The British had scant resources to oppose the German squadron off the coast of South America. Rear Admiral

After the battle, Spee took his ships north to Valparaiso. Since Chile was neutral, only three ships could enter the port at a time; Spee took ''Scharnhorst'', ''Gneisenau'', and ''Nürnberg'' in first on the morning of 3 November, leaving ''Dresden'' and ''Leipzig'' with the colliers at Mas a Fuera. In Valparaiso, Spee's ships could take on coal while he conferred with the Admiralty Staff in Germany to determine the strength of remaining British forces in the region. The ships remained in the port for only 24 hours, in accordance with the neutrality restrictions, and arrived at Mas a Fuera on 6 November, where they took on more coal from captured British and French steamers. On 10 November, ''Dresden'' and ''Leipzig'' were detached for a stop in Valparaiso, and five days later, Spee took the rest of the squadron south to St. Quentin Bay in the Gulf of Penas. On 18 November, ''Dresden'' and ''Leipzig'' met Spee while en route and the squadron reached St. Quentin Bay three days later. There, they took on more coal, since the voyage around

After the battle, Spee took his ships north to Valparaiso. Since Chile was neutral, only three ships could enter the port at a time; Spee took ''Scharnhorst'', ''Gneisenau'', and ''Nürnberg'' in first on the morning of 3 November, leaving ''Dresden'' and ''Leipzig'' with the colliers at Mas a Fuera. In Valparaiso, Spee's ships could take on coal while he conferred with the Admiralty Staff in Germany to determine the strength of remaining British forces in the region. The ships remained in the port for only 24 hours, in accordance with the neutrality restrictions, and arrived at Mas a Fuera on 6 November, where they took on more coal from captured British and French steamers. On 10 November, ''Dresden'' and ''Leipzig'' were detached for a stop in Valparaiso, and five days later, Spee took the rest of the squadron south to St. Quentin Bay in the Gulf of Penas. On 18 November, ''Dresden'' and ''Leipzig'' met Spee while en route and the squadron reached St. Quentin Bay three days later. There, they took on more coal, since the voyage around

''Gneisenau'' and ''Nürnberg'' were delegated for the attack; they approached the Falklands the following morning, with the intention of destroying the wireless transmitter there. Observers aboard ''Gneisenau'' spotted smoke rising from

''Gneisenau'' and ''Nürnberg'' were delegated for the attack; they approached the Falklands the following morning, with the intention of destroying the wireless transmitter there. Observers aboard ''Gneisenau'' spotted smoke rising from  Sturdee then turned to port in an attempt to take the leeward position, but Spee countered the turn to retain his favorable position; the maneuvering did, however, reverse the order of the ships, so ''Gneisenau'' now engaged ''Invincible''. During the reversal, ''Gneisenau'' became temporarily obscured by smoke, so the British ships concentrated their fire on ''Scharnhorst'', which suffered severe damage during this phase of the action. Spee and Maerker exchanged a series of signals to determine the state of each other's vessels; Spee concluded the exchange with a signal noting that Maerker was correct to have opposed the attack on the Falklands. At 15:30, ''Gneisenau'' received a major hit that penetrated to her starboard engine room and disabled that engine, leaving her with just two operational screws. Another hit at 15:45 knocked over her forward funnel, and at 16:00 her number 4 boiler room was disabled.

At 16:00, Spee ordered ''Gneisenau'' to attempt to escape while he reversed course and attempted to launch torpedoes at his pursuers. Damage to the ship's engine and boiler rooms had reduced her speed to , however, and so the ship continued to fight on. ''Gneisenau'' nevertheless could not evade British fire, and at around the same time her bridge was hit. Two more hits followed at 16:15, one passing completely through the ship without detonating and the other exploding in the main dressing station, killing most of the wounded crew there. At 16:17, ''Scharnhorst'' finally capsized to port and sank; the British, their attention now focused on ''Gneisenau'', made no attempt to rescue the crew. By this time, ''Carnarvon'' joined the fray and contributed her guns to the bombardment. As the range fell to , heavy fire from the surviving German guns forced the British to turn away again, widening the range to .

Sturdee then turned to port in an attempt to take the leeward position, but Spee countered the turn to retain his favorable position; the maneuvering did, however, reverse the order of the ships, so ''Gneisenau'' now engaged ''Invincible''. During the reversal, ''Gneisenau'' became temporarily obscured by smoke, so the British ships concentrated their fire on ''Scharnhorst'', which suffered severe damage during this phase of the action. Spee and Maerker exchanged a series of signals to determine the state of each other's vessels; Spee concluded the exchange with a signal noting that Maerker was correct to have opposed the attack on the Falklands. At 15:30, ''Gneisenau'' received a major hit that penetrated to her starboard engine room and disabled that engine, leaving her with just two operational screws. Another hit at 15:45 knocked over her forward funnel, and at 16:00 her number 4 boiler room was disabled.

At 16:00, Spee ordered ''Gneisenau'' to attempt to escape while he reversed course and attempted to launch torpedoes at his pursuers. Damage to the ship's engine and boiler rooms had reduced her speed to , however, and so the ship continued to fight on. ''Gneisenau'' nevertheless could not evade British fire, and at around the same time her bridge was hit. Two more hits followed at 16:15, one passing completely through the ship without detonating and the other exploding in the main dressing station, killing most of the wounded crew there. At 16:17, ''Scharnhorst'' finally capsized to port and sank; the British, their attention now focused on ''Gneisenau'', made no attempt to rescue the crew. By this time, ''Carnarvon'' joined the fray and contributed her guns to the bombardment. As the range fell to , heavy fire from the surviving German guns forced the British to turn away again, widening the range to .

During the final phase of the battle, ''Gneisenau'' ran out of ammunition and resorted to firing inert training rounds; one of these struck ''Invincible''. Three more shells struck ''Gneisenau'' at around 17:15, two of them underwater on the starboard side and the other on a starboard casemate. The former hits caused serious flooding, but the third had little effect, as the gun crew had already been killed by an earlier hit and the casemate was already on fire. Several more hits followed, and by 17:30, ''Gneisenau'' was a burning wreck; she had a severe list to starboard and smoke poured from the ship, which came to a stop. At 17:35, Maerker ordered the crew to set

During the final phase of the battle, ''Gneisenau'' ran out of ammunition and resorted to firing inert training rounds; one of these struck ''Invincible''. Three more shells struck ''Gneisenau'' at around 17:15, two of them underwater on the starboard side and the other on a starboard casemate. The former hits caused serious flooding, but the third had little effect, as the gun crew had already been killed by an earlier hit and the casemate was already on fire. Several more hits followed, and by 17:30, ''Gneisenau'' was a burning wreck; she had a severe list to starboard and smoke poured from the ship, which came to a stop. At 17:35, Maerker ordered the crew to set

armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

of the German '' Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy), part of the two-ship . Named for the earlier screw corvette of the same name, the ship was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

in June 1904 at the AG Weser

Aktien-Gesellschaft „Weser" (abbreviated A.G. „Weser”) was one of the major German shipbuilding companies, located at the Weser River in Bremen. Founded in 1872 it was finally closed in 1983. All together, A.G. „Weser" built about 1,40 ...

shipyard in Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (german: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, ), is the capital of the German state Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (''Freie Hansestadt Bremen''), a two-city-state con ...

, launched in June 1906, and commissioned in March 1908. She was armed with a main battery of eight guns, a significant increase in firepower over earlier German armored cruisers, and she had a top speed of . ''Gneisenau'' initially served with the German fleet in I Scouting Group

The I Scouting Group (german: I. Aufklärungsgruppe) was a special reconnaissance unit within the German Kaiserliche Marine. The unit was famously commanded by Admiral Franz von Hipper during World War I. The I Scouting Group was one of the mos ...

, though her service there was limited owing to the British development of the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of att ...

by 1909, which the less powerful armored cruisers could not effectively combat.

Accordingly, ''Gneisenau'' was assigned to the German East Asia Squadron

The German East Asia Squadron (german: Kreuzergeschwader / Ostasiengeschwader) was an Imperial German Navy cruiser Squadron (naval), squadron which operated mainly in the Pacific Ocean between the mid-1890s until 1914, when it was destroyed at th ...

, where she joined her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

. The two cruisers formed the core of the squadron, which included several light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

s. Over the next four years, ''Gneisenau'' patrolled Germany's colonial possessions in Asia and the Pacific Ocean. She also toured foreign ports to show the flag and monitored events in China during the Xinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty, the Manchu people, Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of Chi ...

in 1911. Following the outbreak of World War I in July 1914, the East Asia Squadron, under the command of Vice Admiral Maximilian von Spee

Maximilian Johannes Maria Hubert Reichsgraf von Spee (22 June 1861 – 8 December 1914) was a naval officer of the German '' Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy), who commanded the East Asia Squadron during World War I. Spee entered the navy i ...

, crossed the Pacific to the western coast of South America, stopping for ''Gneisenau'' and ''Scharnhorst'' to attack French Polynesia

)Territorial motto: ( en, "Great Tahiti of the Golden Haze")

, anthem =

, song_type = Regional anthem

, song = " Ia Ora 'O Tahiti Nui"

, image_map = French Polynesia on the globe (French Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of Frenc ...

in the Bombardment of Papeete

The Bombardment of Papeete occurred in French Polynesia when German warships attacked on 22 September 1914, during World War I. The German armoured cruisers and entered the port of Papeete on the island of Tahiti and sank the French gunboat ...

in September.

After arriving off the coast of Chile, the East Asia Squadron encountered and defeated a British squadron at the Battle of Coronel

The Battle of Coronel was a First World War Imperial German Navy victory over the Royal Navy on 1 November 1914, off the coast of central Chile near the city of Coronel. The East Asia Squadron (''Ostasiengeschwader'' or ''Kreuzergeschwader'') ...

; during the action, ''Gneisenau'' disabled the British armored cruiser , which was then sunk by the German light cruiser . The defeat prompted the British Admiralty

The Admiralty was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom responsible for the command of the Royal Navy until 1964, historically under its titular head, the Lord High Admiral – one of the Great Officers of State. For much of its ...

to detach two battlecruisers to hunt down and destroy Spee's squadron, which they accomplished at the Battle of the Falkland Islands

The Battle of the Falkland Islands was a First World War naval action between the British Royal Navy and Imperial German Navy on 8 December 1914 in the South Atlantic. The British, after their defeat at the Battle of Coronel on 1 November, s ...

on 8 December 1914. ''Gneisenau'' was sunk with heavy loss of life, though 187 of her crew were rescued by the British.

Design

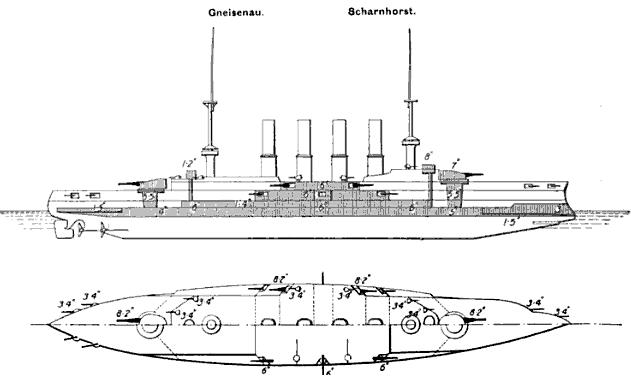

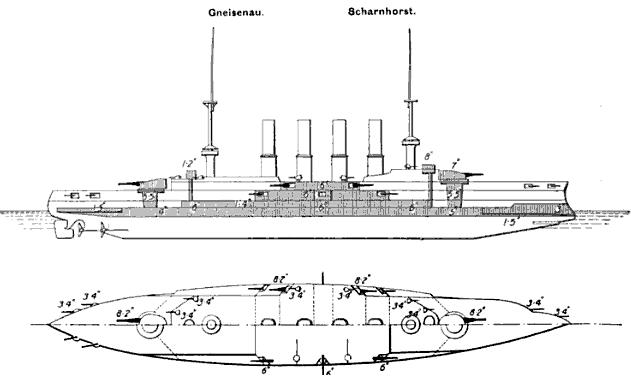

The two ''Scharnhorst''-class cruisers were ordered as part of the naval construction program laid out in the Second Naval Law of 1900, which called for a force of fourteen

The two ''Scharnhorst''-class cruisers were ordered as part of the naval construction program laid out in the Second Naval Law of 1900, which called for a force of fourteen armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

s. The ships marked a significant increase in combat power over their predecessors, the , being more heavily armed and armored. These improvements were made to allow for and ''Gneisenau'' to fight in the line of battle

The line of battle is a tactic in naval warfare in which a fleet of ships forms a line end to end. The first example of its use as a tactic is disputed—it has been variously claimed for dates ranging from 1502 to 1652. Line-of-battle tacti ...

should the need arise, a capability requested by the General Department.

''Gneisenau'' was long overall

__NOTOC__

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, an ...

, and had a beam of and a draft of . The ship displaced normally, and at full load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

. ''Gneisenau''s crew consisted of 38 officers and 726 enlisted men. The ship was powered by three triple-expansion steam engine

A compound steam engine unit is a type of steam engine where steam is expanded in two or more stages.

A typical arrangement for a compound engine is that the steam is first expanded in a high-pressure ''(HP)'' cylinder, then having given up he ...

s, each driving a screw propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

, with steam provided by eighteen coal-fired water-tube boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by the fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-gen ...

s. The boilers were ducted into four funnels located amidships

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water (mostly though not necessarily on the sea). Some remain current, while many date from the 17th t ...

. Her propulsion system was rated to produce for a top speed of . She had a cruising radius of at a speed of .

''Gneisenau''s primary armament consisted of eight SK L/40 guns, four in twin gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanism ...

s, one fore and one aft of the main superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

on the centerline, and the remaining four mounted in single casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to antiquity, the term "casemate wall" mean ...

s in the hull at main deck level, abreast the funnels. Secondary armament included six SK L/40 guns, also in individual casemates that were placed a deck below the main battery casemates. Defense against torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of se ...

s was provided by a battery of eighteen SK L/35 guns mounted in casemates. She was also equipped with four submerged torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s. One was mounted in the bow, one on each broadside, and the fourth was placed in the stern.

The ship was protected by a 15 cm belt of Krupp armor

Krupp armour was a type of steel naval armour used in the construction of capital ships starting shortly before the end of the nineteenth century. It was developed by Germany's Krupp Arms Works in 1893 and quickly replaced Harvey armour as the ...

, decreased to forward and aft of the central citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

In ...

. She had an armored deck that was thick, with the heavier armor protecting the ship's engine

An engine or motor is a machine designed to convert one or more forms of energy into mechanical energy.

Available energy sources include potential energy (e.g. energy of the Earth's gravitational field as exploited in hydroelectric power gene ...

and boiler rooms and ammunition magazines

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combinati ...

. The centerline gun turrets had thick sides, while the casemate main guns received 15 cm of armor protection. The casemate secondary battery was protected by a strake

On a vessel's hull, a strake is a longitudinal course of planking or plating which runs from the boat's stempost (at the bows) to the sternpost or transom (at the rear). The garboard strakes are the two immediately adjacent to the keel on ...

of armor that was thick.

Service history

''Gneisenau'' was the first member of the class to be ordered, on 8 June 1904; she waslaid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

at the AG Weser

Aktien-Gesellschaft „Weser" (abbreviated A.G. „Weser”) was one of the major German shipbuilding companies, located at the Weser River in Bremen. Founded in 1872 it was finally closed in 1983. All together, A.G. „Weser" built about 1,40 ...

shipyard in Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (german: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, ), is the capital of the German state Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (''Freie Hansestadt Bremen''), a two-city-state con ...

on 28 December under yard number

__NOTOC__

M

...

144. A lengthy strike by shipyard workers delayed construction of the vessel, allowing ''Scharnhorst'' to be launched first and thus be the lead ship

The lead ship, name ship, or class leader is the first of a series or class of ships all constructed according to the same general design. The term is applicable to naval ships and large civilian vessels.

Large ships are very complex and may ...

of the class. At ''Gneisenau''Alfred von Schlieffen

Graf Alfred von Schlieffen, generally called Count Schlieffen (; 28 February 1833 – 4 January 1913) was a German field marshal and strategist who served as chief of the Imperial German General Staff from 1891 to 1906. His name lived on in th ...

, the Chief of the General Staff

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, enlisted and civilian staff who serve the commander of a division or other large military u ...

. The ship moved to Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsh ...

for fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

and was commissioned into the fleet on 6 March 1908, before beginning sea trials on 26 March. These lasted until 12 July, when ''Gneisenau'' joined I Scouting Group

The I Scouting Group (german: I. Aufklärungsgruppe) was a special reconnaissance unit within the German Kaiserliche Marine. The unit was famously commanded by Admiral Franz von Hipper during World War I. The I Scouting Group was one of the mos ...

, the reconnaissance squadron of the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

. During this period, ''Kapitän zur See

Captain is the name most often given in English-speaking navies to the rank corresponding to command of the largest ships. The rank is equal to the army rank of colonel and air force rank of group captain.

Equivalent ranks worldwide include ...

'' (''KzS''—Captain at Sea) Franz von Hipper

Franz Ritter von Hipper (13 September 1863 – 25 May 1932) was an admiral in the German Imperial Navy (''Kaiserliche Marine''). Franz von Hipper joined the German Navy in 1881 as an officer cadet. He commanded several torpedo boat units a ...

served as the ship's first commanding officer.

While serving in I Scouting Group, ''Gneisenau'' participated in the normal peacetime training routine with the fleet. She took part in a major fleet cruise in the Atlantic Ocean in company with the battleship squadrons of the High Seas Fleet immediately after completing trials. Prince Heinrich had pressed for such a cruise the previous year, arguing that it would prepare the fleet for overseas operations and would break up the monotony of training in German waters. The cruise came at a time that tensions with Britain over the developing Anglo-German naval arms race

The arms race between Great Britain and Germany that occurred from the last decade of the nineteenth century until the advent of World War I in 1914 was one of the intertwined causes of that conflict. While based in a bilateral relationship that ...

were high, though no incidents occurred as a result. The fleet departed Kiel on 17 July, passed through the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal to the North Sea, and continued to the Atlantic. The fleet returned to Germany on 13 August. The autumn maneuvers followed from 27 August to 12 September, after which Hipper was replaced by ''KzS'' Konrad Trummler.

The year 1909 followed a similar pattern, with two more Atlantic cruises, the first in February and March and the second in July and August. The latter voyage included a visit to Spain. Later in the year, ''Gneisenau'' and the light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

escorted Kaiser Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until his abdication on 9 November 1918. Despite strengthening the German Empir ...

aboard his yacht

A yacht is a sailing or power vessel used for pleasure, cruising, or racing. There is no standard definition, though the term generally applies to vessels with a cabin intended for overnight use. To be termed a , as opposed to a , such a pleasu ...

, ''Hohenzollern'', on a visit to Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the t ...

Nicholas II of Russia

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pol ...

off the coast of Finland. ''Gneisenau'' won the Kaiser's ''Schießpreis'' (Shooting Prize) for excellent shooting among armored cruisers for the 1908–1909 training year. The first half of the following year passed uneventfully for ''Gneisenau'', and in July, she took part in a fleet cruise to Norway. On 8 September, the ship was reassigned to the East Asia Squadron

The German East Asia Squadron (german: Kreuzergeschwader / Ostasiengeschwader) was an Imperial German Navy cruiser Squadron (naval), squadron which operated mainly in the Pacific Ocean between the mid-1890s until 1914, when it was destroyed at th ...

and ''KzS'' Ludolf von Uslar took command of the ship for the deployment. By that time, the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

had begun commissioning their new battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of att ...

s, which significantly outclassed armored cruisers like ''Gneisenau'', but the German command decided that the ship could still be used to strengthen Germany's colonial cruiser squadron.

East Asia Squadron

On 10 November, ''Gneisenau'' departed Wilhelmshaven, bound for Germany'sKiautschou Bay concession

The Kiautschou Bay Leased Territory was a German leased territory in Imperial and Early Republican China from 1898 to 1914. Covering an area of , it centered on Jiaozhou ("Kiautschou") Bay on the southern coast of the Shandong Peninsula ...

in China. She stopped in Málaga

Málaga (, ) is a Municipalities of Spain, municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 578,460 in 2020, it is the second-most populou ...

, Spain, while en route, for a ceremony commemorating the men killed when her namesake corvette had been wrecked there on 16 December 1900. She then passed through the Mediterranean Sea, transited the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popul ...

, and while crossing the Indian Ocean, stopped in Colombo

Colombo ( ; si, කොළඹ, translit=Koḷam̆ba, ; ta, கொழும்பு, translit=Koḻumpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo m ...

, Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

. There, she embarked Crown Prince Wilhelm on 11 December, who was on a tour of British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

at the time. ''Gneisenau'' carried him to Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second-m ...

, where he left the ship. After resuming the voyage to East Asia, ''Gneisenau'' rendezvoused with the light cruiser and made stops in Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bo ...

, Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

, and Amoy

Xiamen ( , ; ), also known as Amoy (, from Hokkien pronunciation ), is a sub-provincial city in southeastern Fujian, People's Republic of China, beside the Taiwan Strait. It is divided into six districts: Huli, Siming, Jimei, Tong'an, ...

before arriving in Tsingtao

Qingdao (, also spelled Tsingtao; , Mandarin: ) is a major city in eastern Shandong Province. The city's name in Chinese characters literally means "azure island". Located on China's Yellow Sea coast, it is a major nodal city of the One Bel ...

, the German squadron's home port, on 14 March 1911. There, she rendezvoused with her sister ''Scharnhorst'', the squadron flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the ...

. On 7 April, ''Gneisenau'' carried the new ambassador to Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

, Arthur Graf Rex, from Taku

Taku may refer to:

Places North America

* the Taku River, in Alaska and British Columbia

** Fort Taku, also known as Fort Durham and as Taku, a former fort of the Hudson's Bay Company near the mouth of the Taku River

** the Taku Glacier, in ...

to Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of ...

, where she met ''Scharnhorst''; the squadron commander, ''Konteradmiral'' (''KAdm''—Rear Admiral) Günther von Krosigk, Uslar, and ''Scharnhorst''s captain met with the Emperor Meiji

, also called or , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession. Reigning from 13 February 1867 to his death, he was the first monarch of the Empire of Japan and presided over the Meiji era. He was the figure ...

. ''Gneisenau'' thereafter went on a tour of Japanese and Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part o ...

n waters, but she was sent back to Tsingtao during the Agadir Crisis

The Agadir Crisis, Agadir Incident, or Second Moroccan Crisis was a brief crisis sparked by the deployment of a substantial force of French troops in the interior of Morocco in April 1911 and the deployment of the German gunboat to Agadir, a ...

to prepare for a potential conflict.

In September, Krosigk shifted his flag to ''Gneisenau'' while ''Scharnhorst'' was in dry dock for periodic maintenance. On 10 October, the Xinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty, the Manchu people, Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of Chi ...

against the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

broke out, which caused a great deal of tension among Europeans in the country, who recalled the attacks on foreigners during the Boxer Uprising

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an anti-foreign, anti-colonial, and anti-Christian uprising in China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, ...

of 1900–1901. The rest of the East Asia Squadron was placed on alert to protect German interests and additional troops were sent to protect the German consulate. But the feared attacks on Europeans did not materialize and so the East Asia Squadron was not needed. By late November, ''Scharnhorst'' was back in service and Krosigk returned to her. ''Gneisenau'' won the ''Schießpreis'' again for the 1910–1911 training year.

''Gneisenau'' went into dry dock in Tsingtao for annual repairs in the first quarter of 1912. On 13 April, the ships embarked on a month-long cruise to Japanese waters, returning to Tsingtao on 13 May. In June, ''KzS'' Willi Brüninghaus relieved Uslar as ''Gneisenau''s commander. Over the course of 1–4 August, ''Gneisenau'' steamed to

''Gneisenau'' went into dry dock in Tsingtao for annual repairs in the first quarter of 1912. On 13 April, the ships embarked on a month-long cruise to Japanese waters, returning to Tsingtao on 13 May. In June, ''KzS'' Willi Brüninghaus relieved Uslar as ''Gneisenau''s commander. Over the course of 1–4 August, ''Gneisenau'' steamed to Pusan

Busan (), officially known as is South Korea's most populous city after Seoul, with a population of over 3.4 million inhabitants. Formerly romanized as Pusan, it is the economic, cultural and educational center of southeastern South Korea, ...

, Korea, where she pulled the HAPAG steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

free after it ran aground and escorted it to Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the Na ...

. At the end of the year, ''Gneisenau'' lay at Shanghai. In early December, Krosigk was replaced by ''KAdm'' Maximilian von Spee

Maximilian Johannes Maria Hubert Reichsgraf von Spee (22 June 1861 – 8 December 1914) was a naval officer of the German '' Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy), who commanded the East Asia Squadron during World War I. Spee entered the navy i ...

, who took ''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau'' on a tour of the southwest Pacific, including stops in Amoy, Singapore, and Batavia. The cruise continued into early 1913, and the two cruisers arrived back in Tsingtao on 2 March 1913. ''Gneisenau'' won the ''Schießpreis'' for the 1912–1913 year.

In April 1913, ''Gneisenau'' and ''Scharnhorst'' went to Japan so Spee and the ships' commanders could meet with the new emperor, Taishō. The vessels then returned to Tsingtao, where they remained for seven weeks. In late June, the two cruisers began a cruise through Germany's colonial possessions in the central Pacific. While in Rabaul on 21 July, Spee received word of further unrest in China, which prompted his return to the Wusong

Wusong, formerly romanized as Woosung, is a subdistrict of Baoshan in northern Shanghai. Prior to the city's expansion, it was a separate port town located down the Huangpu River from Shanghai's urban core.

Name

Wusong is named for the Wus ...

roadstead

A roadstead (or ''roads'' – the earlier form) is a body of water sheltered from rip currents, spring tides, or ocean swell where ships can lie reasonably safely at anchor without dragging or snatching.United States Army technical manual, TM 5 ...

outside Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowin ...

by 30 July. ''Gneisenau'' thereafter patrolled in the Yellow Sea and visited Port Arthur in October. After the situation calmed, Spee was able to take his ships on a short cruise to Japan, which began on 11 November. ''Scharnhorst'' and the rest of the squadron returned to Shanghai on 29 November, before she departed for another trip to Southeast Asia. Stops included Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

, Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent is ...

, North Borneo

(I persevere and I achieve)

, national_anthem =

, capital = Kudat (1881–1884);Sandakan (1884–1945);Jesselton (1946)

, common_languages = English, Kadazan-Dusun, Bajau, Murut, Sabah Malay, Chinese etc.

, go ...

, and Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populated ...

in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

.

In June 1914, ''KzS'' Julius Maerker took command of the ship. Shortly thereafter, Spee embarked on a cruise to German New Guinea

German New Guinea (german: Deutsch-Neu-Guinea) consisted of the northeastern part of the island of New Guinea and several nearby island groups and was the first part of the German colonial empire. The mainland part of the territory, called , ...

; ''Gneisenau'' rendezvoused with ''Scharnhorst'' in Nagasaki, Japan, where they received a full supply of coal. They then sailed south, arriving in Truk in early July where they restocked their coal supplies. While en route, they received news of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Archduke Franz Ferdinand Carl Ludwig Joseph Maria of Austria, (18 December 1863 – 28 June 1914) was the heir presumptive to the throne of Austria-Hungary. His assassination in Sarajevo was the most immediate cause of World War I.

F ...

, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with t ...

. On 17 July, the East Asia Squadron arrived in Ponape in the Caroline Islands

The Caroline Islands (or the Carolines) are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically, they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) in the centra ...

. Here, Spee had access to the German radio network, where he learned of the Austro-Hungarian declaration of war on Serbia and the Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

* Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and p ...

mobilization. On 31 July, word came that the German ultimatum, which demanded the demobilization of Russia's armies, was set to expire. Spee ordered his ships be stripped for war. On 2 August, Wilhelm II ordered German mobilization against France and Russia.

World War I

When World War I broke out, the East Asia Squadron consisted of ''Scharnhorst'', ''Gneisenau'', and the light cruisers ''Emden'', , and . At the time, ''Nürnberg'' was returning from the west coast of the United States, where ''Leipzig'' had just replaced her, and ''Emden'' was still in Tsingtao. On 6 August 1914, ''Scharnhorst'', ''Gneisenau'', the supply ship ''Titania'', and the Japanese collier ''Fukoku Maru'' were still in Ponape. Spee had issued orders to recall the light cruisers, which had been dispersed on cruises around the Pacific. ''Nürnberg'' joined Spee that day, after which Spee moved his ships toPagan Island

Pagan is a volcanic island in the Marianas archipelago in the northwest Pacific Ocean, under the jurisdiction of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. It lies midway between Alamagan to the south, and Agrihan to the north. The isl ...

in the Northern Mariana Islands

The Northern Mariana Islands, officially the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI; ch, Sankattan Siha Na Islas Mariånas; cal, Commonwealth Téél Falúw kka Efáng llól Marianas), is an unincorporated territory and commonwe ...

, a German possession in the central Pacific. Spee left for Pagan in the night, without ''Fukoku Maru'', to avoid having the Japanese crew betray his movements.

All available colliers, supply ships, and passenger liners were ordered to meet the East Asia Squadron in Pagan and ''Emden'' joined the squadron there on 12 August. The auxiliary cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

joined Spee's ships there as well. On 13 August, Commodore Karl von Müller, captain of the ''Emden'', persuaded Spee to detach his ship as a commerce raider. The four cruisers, accompanied by ''Prinz Eitel Friedrich'' and several colliers, then departed Pagan on 15 August, bound for Chile. While en route to Enewetak Atoll

Enewetak Atoll (; also spelled Eniwetok Atoll or sometimes Eniewetok; mh, Ānewetak, , or , ; known to the Japanese as Brown Atoll or Brown Island; ja, ブラウン環礁) is a large coral atoll of 40 islands in the Pacific Ocean and with i ...

in the Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Intern ...

the next morning, ''Emden'' left the formation with one of the colliers. The remaining ships again coaled after their arrival in Enewetak on 20 August.

To keep the German high command informed, on 8 September Spee detached ''Nürnberg'' to Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an Unincorporated area, unincorporated county seat of the Consolidated city-county, consolidated City and County of H ...

to send word through neutral countries. ''Nürnberg'' returned with news of the Allied capture of German Samoa, which had taken place on 29 August. ''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau'' sailed to Apia to investigate the situation. Spee had hoped to catch a British or Australian warship by surprise, but upon his arrival on 14 September, he found no warships in the harbor. On 22 September, ''Scharnhorst'' and the rest of the East Asia Squadron arrived at the French colony of Papeete

Papeete ( Tahitian: ''Papeete'', pronounced ) is the capital city of French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of the French Republic in the Pacific Ocean. The commune of Papeete is located on the island of Tahiti, in the administrative subd ...

. The Germans attacked the colony, and in the ensuing battle of Papeete, they sank the French gunboat ''Zélée''. The ships came under fire from French shore batteries but were undamaged. Fear of mines in the harbor prevented Spee from entering the harbor to seize the coal, which the French had set on fire.

By 12 October, ''Gneisenau'' and the rest of the squadron had reached Easter Island

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearly ...

. There they were joined by the light cruisers and ''Leipzig'', which had sailed from American waters, on 12 and 14 October, respectively. ''Leipzig'' also brought three more colliers with her. After a week in the area, the ships departed for Chile. On the evening of 26 October, ''Gneisenau'' and the rest of the squadron steamed out of Mas a Fuera, Chile and headed eastward, arriving in Valparaíso

Valparaíso (; ) is a major city, seaport, naval base, and educational centre in the commune of Valparaíso, Chile. "Greater Valparaíso" is the second largest metropolitan area in the country. Valparaíso is located about northwest of Santiago ...

on 30 October. On 1 November, Spee learned from ''Prinz Eitel Friedrich'' that the British light cruiser had been anchored in Coronel the previous day, so he turned towards the port to try to catch her alone.

Battle of Coronel

Christopher Cradock

Rear Admiral Sir Christopher "Kit" George Francis Maurice Cradock (2 July 1862 – 1 November 1914) was an English senior officer of the Royal Navy. He earned a reputation for great gallantry.

Appointed to the royal yacht, he was close to the ...

commanded the armored cruisers and , ''Glasgow'', and the converted armed merchant cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

. The flotilla was reinforced by the elderly pre-dreadnought battleship

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built between the mid- to late- 1880s and 1905, before the launch of in 1906. The pre-dreadnought ships replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s. Built from steel, protec ...

and the armored cruiser . The latter, however, did not arrive until after the Battle of Coronel. ''Canopus'' was left behind by Cradock, who probably felt her slow speed would prevent him from bringing the German ships to battle.

The East Asia Squadron arrived off Coronel on the afternoon of 1 November; to Spee's surprise, he encountered ''Good Hope'', ''Monmouth'', and ''Otranto'' in addition to ''Glasgow''. ''Canopus'' was still some behind, with the British colliers. At 16:17, ''Glasgow'' spotted the German ships. Cradock formed a line of battle with ''Good Hope'' in the lead, followed by ''Monmouth'', ''Glasgow'', and ''Otranto'' in the rear. Spee decided to hold off engaging until the sun had set more, at which point the British ships would be silhouetted by the sun, while his own ships would be obscured against the coast behind them. Spee turned his ships on a course nearly parallel to Cradock's ships, slowly closing the range. Cradock realized the uselessness of ''Otranto'' in the line of battle and detached her. Heavy seas made working the casemate guns in both sides' armored cruisers difficult.

By 18:07, the distance between the two squadrons had fallen to and at 18:37 Spee ordered his ships to open fire, by which time the range had dropped to . Each ship engaged their opposite in the British line, ''Gneisenau''s target being ''Monmouth''. ''Gneisenau'' struck ''Monmouth'' with her third salvo, one shell hitting her forward turret, blowing the roof off, and starting a fire. ''Gneisenau'' fired primarily armor-piercing shell

Armour-piercing ammunition (AP) is a type of projectile designed to penetrate either body armour or vehicle armour.

From the 1860s to 1950s, a major application of armour-piercing projectiles was to defeat the thick armour carried on many warsh ...

s and scored numerous hits, knocking out many of ''Monmouth''s guns. By 18:50, ''Monmouth'' had been badly damaged by ''Gneisenau'' and she fell out of line; ''Gneisenau'' therefore joined ''Scharnhorst'' in battling ''Good Hope''. At around that time, ''Gneisenau'' received a hit that struck her rear turret but did not penetrate the armor, instead exploding outside and setting fire to life jacket

A personal flotation device (PFD; also referred to as a life jacket, life preserver, life belt, Mae West, life vest, life saver, cork jacket, buoyancy aid or flotation suit) is a flotation device in the form of a vest or suite that is worn by a ...

s stored there, though the crew quickly suppressed the blaze.

At the same time, ''Nürnberg'' closed to point-blank range of ''Monmouth'' and poured shells into her. At 19:23, ''Good Hope''s guns fell silent following two large explosions; the German gunners ceased fire shortly thereafter. ''Good Hope'' disappeared into the darkness. Spee ordered his light cruisers to close with his battered opponents and finish them off with torpedoes, while he took ''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau'' further south to get out of the way. ''Glasgow'' was forced to abandon ''Monmouth'' after 19:20 when the German light cruisers approached, before fleeing south and meeting with ''Canopus''. A squall prevented the Germans from discovering ''Monmouth'', but she eventually capsized and sank at 20:18. More than 1,600 men were killed in the sinking of the two armored cruisers, including Cradock. German losses were negligible; ''Gneisenau'' had been hit four times but was not significantly damaged and suffered only two crewmen lightly injured. However, the German ships had expended over 40 percent of their ammunition supply.

Voyage to the Falklands

After the battle, Spee took his ships north to Valparaiso. Since Chile was neutral, only three ships could enter the port at a time; Spee took ''Scharnhorst'', ''Gneisenau'', and ''Nürnberg'' in first on the morning of 3 November, leaving ''Dresden'' and ''Leipzig'' with the colliers at Mas a Fuera. In Valparaiso, Spee's ships could take on coal while he conferred with the Admiralty Staff in Germany to determine the strength of remaining British forces in the region. The ships remained in the port for only 24 hours, in accordance with the neutrality restrictions, and arrived at Mas a Fuera on 6 November, where they took on more coal from captured British and French steamers. On 10 November, ''Dresden'' and ''Leipzig'' were detached for a stop in Valparaiso, and five days later, Spee took the rest of the squadron south to St. Quentin Bay in the Gulf of Penas. On 18 November, ''Dresden'' and ''Leipzig'' met Spee while en route and the squadron reached St. Quentin Bay three days later. There, they took on more coal, since the voyage around

After the battle, Spee took his ships north to Valparaiso. Since Chile was neutral, only three ships could enter the port at a time; Spee took ''Scharnhorst'', ''Gneisenau'', and ''Nürnberg'' in first on the morning of 3 November, leaving ''Dresden'' and ''Leipzig'' with the colliers at Mas a Fuera. In Valparaiso, Spee's ships could take on coal while he conferred with the Admiralty Staff in Germany to determine the strength of remaining British forces in the region. The ships remained in the port for only 24 hours, in accordance with the neutrality restrictions, and arrived at Mas a Fuera on 6 November, where they took on more coal from captured British and French steamers. On 10 November, ''Dresden'' and ''Leipzig'' were detached for a stop in Valparaiso, and five days later, Spee took the rest of the squadron south to St. Quentin Bay in the Gulf of Penas. On 18 November, ''Dresden'' and ''Leipzig'' met Spee while en route and the squadron reached St. Quentin Bay three days later. There, they took on more coal, since the voyage around Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

would be a long one and it was unclear when they would have another opportunity to coal.

Once word of the defeat reached London, the Royal Navy set to organizing a force to hunt down and destroy the East Asia Squadron. To this end, the powerful battlecruisers and were detached from the Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the F ...

and placed under the command of Vice Admiral Doveton Sturdee. The two ships left Devonport on 10 November. En route to the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubou ...

, they were joined by the armored cruisers , , and , the light cruisers and ''Glasgow'', and ''Otranto;'' the force of eight ships reached the Falklands by 7 December, where they immediately coaled.

In the meantime, Spee's ships departed St. Quentin Bay on 26 November and rounded Cape Horn on 2 December. They captured the Canadian barque

A barque, barc, or bark is a type of sailing vessel with three or more masts having the fore- and mainmasts rigged square and only the mizzen (the aftmost mast) rigged fore and aft. Sometimes, the mizzen is only partly fore-and-aft rigged, b ...

''Drummuir'', which had a cargo of of good-quality Cardiff

Cardiff (; cy, Caerdydd ) is the capital and largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Cardiff ( cy, Dinas a Sir Caerdydd, links=no), and the city is the eleventh-largest in the United Ki ...

coal. ''Leipzig'' took the ship under tow and the following day the ships stopped off Picton Island. The crews transferred the coal from ''Drummuir'' to the squadron's colliers. On the morning of 6 December, Spee held a conference with the ship commanders aboard ''Scharnhorst'' to determine their next course of action. The Germans had received numerous fragmentary and contradictory reports of British reinforcements in the region; Spee and two other captains favored an attack on the Falklands, while three other commanders, including Maerker, argued that it would be better to bypass the islands and attack British shipping off Argentina. Spee's opinion carried the day and the squadron departed for the Falklands at 12:00.

Battle of the Falkland Islands

Port Stanley

Stanley (; also known as Port Stanley) is the capital city of the Falkland Islands. It is located on the island of East Falkland, on a north-facing slope in one of the wettest parts of the islands. At the 2016 census, the city had a populat ...

, but assumed it was the British burning their coal stocks to prevent the Germans from seizing them. As they closed on the harbor, shells from ''Canopus'', which had been beached as a guard ship, began to fall around the German ships. Lookouts on the German ships spotted the large tripod masts of the battlecruisers, though these were initially believed to be from the battlecruiser ; the reports of several enemy warships combined with fire from ''Canopus'' prompted Spee to break off the attack. The Germans took a southeasterly course at after having reformed by 10:45. Spee formed his line with ''Gneisenau'' and ''Nürnberg'' ahead, ''Scharnhorst'' in the center, and ''Dresden'' and ''Leipzig'' astern. The fast battlecruisers quickly got up steam and sailed out of the harbor to pursue the East Asia Squadron.

Spee realized his armored cruisers could not escape the much faster battlecruisers and ordered the three light cruisers to attempt to break away while he turned about and allowed the British battlecruisers to engage the outgunned ''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau''. Meanwhile, Sturdee detached his cruisers to pursue the German light cruisers. ''Invincible'' opened fire at ''Scharnhorst'' while ''Inflexible'' attacked ''Gneisenau'' and Spee ordered his two armored cruisers to similarly engage their opposites. Spee had taken the lee

Lee may refer to:

Name

Given name

* Lee (given name), a given name in English

Surname

* Chinese surnames romanized as Li or Lee:

** Li (surname 李) or Lee (Hanzi ), a common Chinese surname

** Li (surname 利) or Lee (Hanzi ), a Chinese ...

position; the wind kept his ships swept of smoke, which improved visibility for his gunners. This forced Sturdee into the windward position and its corresponding worse visibility. ''Gneisenau'' quickly scored two hits on her opponent. In response to these hits, Sturdee attempted to widen the distance by turning two points to the north. This would place his ships beyond the effective range of the German guns, but keep his opponents within range of his own. Both sides checked their fire for the time being; ''Gneisenau'' had been hit twice during this stage of the battle, the first shell striking the aft funnel, killing and wounding several men with shell splinters. The second shell damaged some of the ship's cutters and penetrated into some cabins amidships. Shell fragments from a near miss penetrated into one of the magazines for the 8.8 cm guns, forcing it to be flooded to prevent a fire.

Spee countered Sturdee's maneuver by turning rapidly to the south, which significantly widened the range and temporarily raised the possibility of escaping by nightfall. The maneuver forced Sturdee to turn south as well and pursue at high speed. Given the speed advantage and the clear weather, the German hope to escape proved to be short-lived. Nevertheless, the maneuver allowed Spee to turn back north, bringing ''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau'' close enough to engage with their secondary 15 cm guns; their shooting was so effective that it forced the British to haul away a second time. After resuming the battle, the British gunfire became more accurate, and as the British were firing at very long range, the shells approached plunging fire

Plunging fire is a form of indirect fire, where gunfire is fired at a trajectory to make it fall on its target from above. It is normal at the high trajectories used to attain long range, and can be used deliberately to attack a target not susc ...

, which allowed them to penetrate the thin deck armor rather than the thicker belt. ''Gneisenau'' took several hits during this phase, including a pair of underwater hits that began to flood boiler rooms 1 and 3.

Sturdee then turned to port in an attempt to take the leeward position, but Spee countered the turn to retain his favorable position; the maneuvering did, however, reverse the order of the ships, so ''Gneisenau'' now engaged ''Invincible''. During the reversal, ''Gneisenau'' became temporarily obscured by smoke, so the British ships concentrated their fire on ''Scharnhorst'', which suffered severe damage during this phase of the action. Spee and Maerker exchanged a series of signals to determine the state of each other's vessels; Spee concluded the exchange with a signal noting that Maerker was correct to have opposed the attack on the Falklands. At 15:30, ''Gneisenau'' received a major hit that penetrated to her starboard engine room and disabled that engine, leaving her with just two operational screws. Another hit at 15:45 knocked over her forward funnel, and at 16:00 her number 4 boiler room was disabled.

At 16:00, Spee ordered ''Gneisenau'' to attempt to escape while he reversed course and attempted to launch torpedoes at his pursuers. Damage to the ship's engine and boiler rooms had reduced her speed to , however, and so the ship continued to fight on. ''Gneisenau'' nevertheless could not evade British fire, and at around the same time her bridge was hit. Two more hits followed at 16:15, one passing completely through the ship without detonating and the other exploding in the main dressing station, killing most of the wounded crew there. At 16:17, ''Scharnhorst'' finally capsized to port and sank; the British, their attention now focused on ''Gneisenau'', made no attempt to rescue the crew. By this time, ''Carnarvon'' joined the fray and contributed her guns to the bombardment. As the range fell to , heavy fire from the surviving German guns forced the British to turn away again, widening the range to .

Sturdee then turned to port in an attempt to take the leeward position, but Spee countered the turn to retain his favorable position; the maneuvering did, however, reverse the order of the ships, so ''Gneisenau'' now engaged ''Invincible''. During the reversal, ''Gneisenau'' became temporarily obscured by smoke, so the British ships concentrated their fire on ''Scharnhorst'', which suffered severe damage during this phase of the action. Spee and Maerker exchanged a series of signals to determine the state of each other's vessels; Spee concluded the exchange with a signal noting that Maerker was correct to have opposed the attack on the Falklands. At 15:30, ''Gneisenau'' received a major hit that penetrated to her starboard engine room and disabled that engine, leaving her with just two operational screws. Another hit at 15:45 knocked over her forward funnel, and at 16:00 her number 4 boiler room was disabled.

At 16:00, Spee ordered ''Gneisenau'' to attempt to escape while he reversed course and attempted to launch torpedoes at his pursuers. Damage to the ship's engine and boiler rooms had reduced her speed to , however, and so the ship continued to fight on. ''Gneisenau'' nevertheless could not evade British fire, and at around the same time her bridge was hit. Two more hits followed at 16:15, one passing completely through the ship without detonating and the other exploding in the main dressing station, killing most of the wounded crew there. At 16:17, ''Scharnhorst'' finally capsized to port and sank; the British, their attention now focused on ''Gneisenau'', made no attempt to rescue the crew. By this time, ''Carnarvon'' joined the fray and contributed her guns to the bombardment. As the range fell to , heavy fire from the surviving German guns forced the British to turn away again, widening the range to .

During the final phase of the battle, ''Gneisenau'' ran out of ammunition and resorted to firing inert training rounds; one of these struck ''Invincible''. Three more shells struck ''Gneisenau'' at around 17:15, two of them underwater on the starboard side and the other on a starboard casemate. The former hits caused serious flooding, but the third had little effect, as the gun crew had already been killed by an earlier hit and the casemate was already on fire. Several more hits followed, and by 17:30, ''Gneisenau'' was a burning wreck; she had a severe list to starboard and smoke poured from the ship, which came to a stop. At 17:35, Maerker ordered the crew to set

During the final phase of the battle, ''Gneisenau'' ran out of ammunition and resorted to firing inert training rounds; one of these struck ''Invincible''. Three more shells struck ''Gneisenau'' at around 17:15, two of them underwater on the starboard side and the other on a starboard casemate. The former hits caused serious flooding, but the third had little effect, as the gun crew had already been killed by an earlier hit and the casemate was already on fire. Several more hits followed, and by 17:30, ''Gneisenau'' was a burning wreck; she had a severe list to starboard and smoke poured from the ship, which came to a stop. At 17:35, Maerker ordered the crew to set scuttling

Scuttling is the deliberate sinking of a ship. Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel from becoming a navigation hazard; as an act of self-destruction to prevent the ship from being ...

charges and gather on the deck, as the ship was unable to continue fighting. The forward gun turret fired a final shell despite Maerker's instructions, prompting a return shot from ''Inflexible'' that struck the forward dressing station, killing many wounded men there. At 17:42, the scuttling charges detonated and the forward torpedo crew launched a torpedo to clear the tube and hasten the flooding.

The ship slowly rolled over and sank, but not before allowing some 270 to 300 of the survivors time to escape. Of these men, many died quickly from exposure in the water. A total of 598 men of her crew were killed in the engagement, though boats from ''Invincible'' and ''Inflexible'' picked up 187 men from ''Gneisenau'', including her executive officer

An executive officer is a person who is principally responsible for leading all or part of an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization. In many militaries and police forces, an executive officer, o ...

, ''Korvettenkapitän

() is the lowest ranking senior officer in a number of Germanic-speaking navies.

Austro-Hungary

Belgium

Germany

Korvettenkapitän, short: KKpt/in lists: KK, () is the lowest senior officer rank () in the German Navy.

Address

The offi ...

'' (Corvette Captain) Hans Pochhammer, the highest ranking German officer to survive and the source of German records of the battle. ''Leipzig'' and ''Nürnberg'' were also sunk. Only ''Dresden'' managed to escape, but she was eventually tracked to the Juan Fernandez Islands

''Juan'' is a given name, the Spanish and Manx versions of ''John''. It is very common in Spain and in other Spanish-speaking communities around the world and in the Philippines, and also (pronounced differently) in the Isle of Man. In Spanish, ...

and sunk. The complete destruction of the squadron killed some 2,200 German sailors and officers, including Spee and two of his sons.

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Gneisenau Scharnhorst-class cruisers Ships built in Bremen (state) 1906 ships World War I cruisers of Germany World War I shipwrecks in the Atlantic Ocean Shipwrecks of the Falkland Islands Maritime incidents in December 1914