SAM Laboratories on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

K-25 was the codename given by the

K-25 was the codename given by the

In April 1940,

In April 1940,

A secret contract was awarded to M. W. Kellogg for engineering studies in July 1941. This included the design and construction of a ten-stage pilot gaseous diffusion plant. On 14 December 1942, the Manhattan District, the US Army component of the Manhattan Project, as the effort to develop an atomic bomb became known, contracted Kellogg to design, build and operate a full-scale production plant. Unusually, the contract did not require any guarantees from Kellogg that it could actually accomplish this task. Because the scope of the project was not well defined, Kellogg and the Manhattan District agreed to defer any financial details to a later,

A secret contract was awarded to M. W. Kellogg for engineering studies in July 1941. This included the design and construction of a ten-stage pilot gaseous diffusion plant. On 14 December 1942, the Manhattan District, the US Army component of the Manhattan Project, as the effort to develop an atomic bomb became known, contracted Kellogg to design, build and operate a full-scale production plant. Unusually, the contract did not require any guarantees from Kellogg that it could actually accomplish this task. Because the scope of the project was not well defined, Kellogg and the Manhattan District agreed to defer any financial details to a later,

K-25 was the codename given by the

K-25 was the codename given by the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

to the program to produce enriched uranium

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238U ...

for atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

s using the gaseous diffusion method. Originally the codename for the product, over time it came to refer to the project, the production facility located at the Clinton Engineer Works

The Clinton Engineer Works (CEW) was the production installation of the Manhattan Project that during World War II produced the enriched uranium used in the 1945 bombing of Hiroshima, as well as the first examples of reactor-produced plu ...

in Oak Ridge, Tennessee

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson County, Tennessee, Anderson and Roane County, Tennessee, Roane counties in the East Tennessee, eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of downtown Knoxville, Tennessee, Knoxville. Oak Ridge's popu ...

, the main gaseous diffusion building, and ultimately the site. When it was built in 1944, the four-story K-25 gaseous diffusion plant was the world's largest building, comprising over of floor space and a volume of .

Construction of the K-25 facility was undertaken by J. A. Jones Construction. At the height of construction, over 25,000 workers were employed on the site. Gaseous diffusion was but one of three enrichment technologies used by the Manhattan Project. Slightly enriched product from the S-50 thermal diffusion plant was fed into the K-25 gaseous diffusion plant. Its product in turn was fed into the Y-12 electromagnetic plant. The enriched uranium was used in the Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ''Enola Gay'' p ...

atomic bomb used in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. In 1946, the K-25 gaseous diffusion plant became capable of producing highly enriched product.

After the war, four more gaseous diffusion plants named K-27, K-29, K-31 and K-33 were added to the site. The K-25 site was renamed the Oak Ridge Gaseous Diffusion Plant in 1955. Production of enriched uranium ended in 1964, and gaseous diffusion finally ceased on the site on 27 August 1985. The Oak Ridge Gaseous Diffusion Plant was renamed the Oak Ridge K-25 Site in 1989, and the East Tennessee Technology Park in 1996. Demolition of all five gaseous diffusion plants was completed in February 2017.

Background

The discovery of theneutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the atomic nucleus, nuclei of atoms. Since protons and ...

by James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick, (20 October 1891 – 24 July 1974) was an English physicist who was awarded the 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the neutron in 1932. In 1941, he wrote the final draft of the MAUD Report, which inspi ...

in 1932, followed by that of nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radio ...

in uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

by the German chemists Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and father of nuclear fission. Hahn and Lise Meitner ...

and Fritz Strassmann

Friedrich Wilhelm Strassmann (; 22 February 1902 – 22 April 1980) was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in December 1938, identified the element barium as a product of the bombardment of uranium with neutrons. Their observation was the ke ...

in 1938, and its theoretical explanation (and naming) by Lise Meitner

Elise Meitner ( , ; 7 November 1878 – 27 October 1968) was an Austrian-Swedish physicist who was one of those responsible for the discovery of the element protactinium and nuclear fission. While working at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute on r ...

and Otto Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch FRS (1 October 1904 – 22 September 1979) was an Austrian-born British physicist who worked on nuclear physics. With Lise Meitner he advanced the first theoretical explanation of nuclear fission (coining the term) and first ...

soon after, opened up the possibility of a controlled nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series of these reactions. The specific nu ...

with uranium. At the Pupin Laboratories at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

, Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" an ...

and Leo Szilard

Leo Szilard (; hu, Szilárd Leó, pronounced ; born Leó Spitz; February 11, 1898 – May 30, 1964) was a Hungarian-German-American physicist and inventor. He conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear ...

began exploring how this might be achieved. Fears that a German atomic bomb project

The Uranverein ( en, "Uranium Club") or Uranprojekt ( en, "Uranium Project") was the name given to the project in Germany to research nuclear technology, including nuclear weapons and nuclear reactors, during World War II. It went through ...

would develop atomic weapons first, especially among scientists who were refugees from Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and other fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

countries, were expressed in the Einstein-Szilard letter to the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

, Franklin D. Roosevelt. This prompted Roosevelt to initiate preliminary research in late 1939.

Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922 ...

and John Archibald Wheeler

John Archibald Wheeler (July 9, 1911April 13, 2008) was an American theoretical physicist. He was largely responsible for reviving interest in general relativity in the United States after World War II. Wheeler also worked with Niels Bohr in ...

applied the liquid drop model

In nuclear physics, the semi-empirical mass formula (SEMF) (sometimes also called the Weizsäcker formula, Bethe–Weizsäcker formula, or Bethe–Weizsäcker mass formula to distinguish it from the Bethe–Weizsäcker process) is used to approxi ...

of the atomic nucleus

The atomic nucleus is the small, dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom, discovered in 1911 by Ernest Rutherford based on the 1909 Geiger–Marsden gold foil experiment. After the discovery of the neutron ...

to explain the mechanism of nuclear fission. As the experimental physicists studied fission, they uncovered puzzling results. George Placzek

George Placzek (; September 26, 1905 – October 9, 1955) was a Moravian physicist.

Biography

Placzek was born into a wealthy Jewish family in Brünn, Moravia (now Brno, Czech Republic), the grandson of Chief Rabbi Baruch Placzek.PDF He studi ...

asked Bohr why uranium seemed to fission with both fast and slow neutrons. Walking to a meeting with Wheeler, Bohr had an insight that the fission at low energies was due to the uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exi ...

isotope

Isotopes are two or more types of atoms that have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), and that differ in nucleon numbers ( mass num ...

, while at high energies it was mainly due to the far more abundant uranium-238

Uranium-238 (238U or U-238) is the most common isotope of uranium found in nature, with a relative abundance of 99%. Unlike uranium-235, it is non-fissile, which means it cannot sustain a chain reaction in a thermal-neutron reactor. However ...

isotope. The former makes up just 0.714 percent of the uranium atoms in natural uranium, about one in every 140; natural uranium is 99.28 percent uranium-238. There is also a tiny amount of uranium-234

Uranium-234 (234U or U-234) is an isotope of uranium. In natural uranium and in uranium ore, 234U occurs as an indirect decay product of uranium-238, but it makes up only 0.0055% (55 parts per million) of the raw uranium because its half-life ...

, which accounts for just 0.006 percent.

At Columbia, John R. Dunning

John Ray Dunning (September 24, 1907 – August 25, 1975) was an American physicist who played key roles in the Manhattan Project that developed the first atomic bombs. He specialized in neutron physics, and did pioneering work in gaseous diffusio ...

believed this was the case, but Fermi was not so sure. The only way to settle this was to obtain a sample of uranium-235 and test it. He got Alfred O. C. Nier from the University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, formally the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, (UMN Twin Cities, the U of M, or Minnesota) is a public land-grant research university in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. ...

to prepare samples of uranium enriched in uranium-234, 235 and 238 using a mass spectrometer

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a '' mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is us ...

. These were ready in February 1940, and Dunning, Eugene T. Booth and Aristid von Grosse

Aristid von Grosse (January 1905 – July 21, 1985) was a German nuclear chemist. During his work with Otto Hahn, he got access to waste material from radium production, and with this starting material he was able in 1927 to isolate protact ...

then carried out a series of experiments. They demonstrated that uranium-235 was indeed primarily responsible for fission with slow neutrons, but were unable to determine precise neutron capture

Neutron capture is a nuclear reaction in which an atomic nucleus and one or more neutrons collide and merge to form a heavier nucleus. Since neutrons have no electric charge, they can enter a nucleus more easily than positively charged protons ...

cross sections because their samples were not sufficiently enriched.

At the University of Birmingham

, mottoeng = Through efforts to heights

, established = 1825 – Birmingham School of Medicine and Surgery1836 – Birmingham Royal School of Medicine and Surgery1843 – Queen's College1875 – Mason Science College1898 – Mason Univers ...

in Britain, the Australian physicist Mark Oliphant assigned two refugee physicists—Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls

Sir Rudolf Ernst Peierls, (; ; 5 June 1907 – 19 September 1995) was a German-born British physicist who played a major role in Tube Alloys, Britain's nuclear weapon programme, as well as the subsequent Manhattan Project, the combined Allie ...

—the task of investigating the feasibility of an atomic bomb, ironically because their status as enemy aliens precluded their working on secret projects like radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

. Their March 1940 Frisch–Peierls memorandum

The Frisch–Peierls memorandum was the first technical exposition of a practical nuclear weapon. It was written by expatriate German-Jewish physicists Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls in March 1940 while they were both working for Mark Oliphant a ...

indicated that the critical mass

In nuclear engineering, a critical mass is the smallest amount of fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specifically, its nuclear fi ...

of uranium-235 was within an order of magnitude

An order of magnitude is an approximation of the logarithm of a value relative to some contextually understood reference value, usually 10, interpreted as the base of the logarithm and the representative of values of magnitude one. Logarithmic di ...

of , which was small enough to be carried by a bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped from an air ...

aircraft of the day.

Gaseous diffusion

In April 1940,

In April 1940, Jesse Beams

Jesse Wakefield Beams (December 25, 1898 in Belle Plaine, Kansas – July 23, 1977) was an American physicist at the University of Virginia.

Biography

Beams completed his undergraduate B.A. in physics at Fairmount College in 1921 and his mas ...

, Ross Gunn, Fermi, Nier, Merle Tuve

Merle Anthony Tuve (June 27, 1901 – May 20, 1982) was an American geophysicist who was the Chairman of the Office of Scientific Research and Development's Section T, which was created in August 1940. He was founding director of the Johns Hopkins ...

and Harold Urey

Harold Clayton Urey ( ; April 29, 1893 – January 5, 1981) was an American physical chemist whose pioneering work on isotopes earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934 for the discovery of deuterium. He played a significant role in th ...

had a meeting at the American Physical Society

The American Physical Society (APS) is a not-for-profit membership organization of professionals in physics and related disciplines, comprising nearly fifty divisions, sections, and other units. Its mission is the advancement and diffusion of k ...

in Washington, D.C. At the time, the prospect of building an atomic bomb seemed dim, and even creating a chain reaction would likely require enriched uranium. They therefore recommended that research be conducted with the aim of developing the means to separate kilogram amounts of uranium-235. At a lunch on 21 May 1940, George B. Kistiakowsky suggested the possibility of using gaseous diffusion.

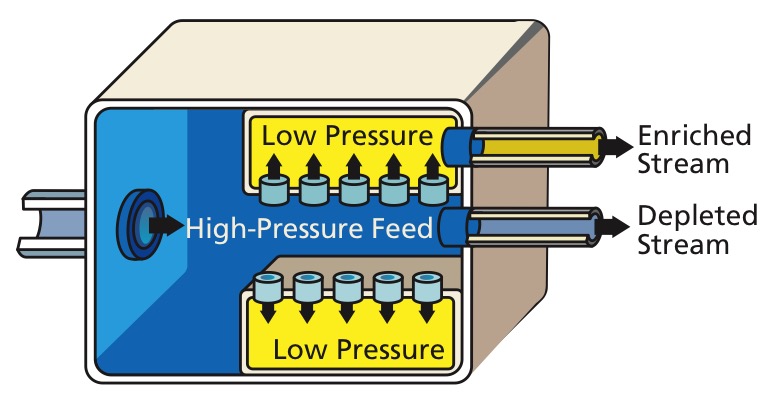

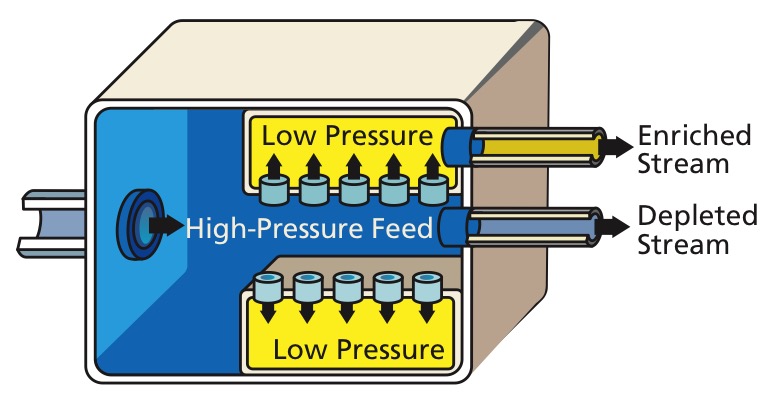

Gaseous diffusion is based on Graham's law

Graham's law of effusion (also called Graham's law of diffusion) was formulated by Scottish physical chemist Thomas Graham in 1848.Keith J. Laidler and John M. Meiser, ''Physical Chemistry'' (Benjamin/Cummings 1982), pp. 18–19 Graham found ...

, which states that the rate of effusion

In physics and chemistry, effusion is the process in which a gas escapes from a container through a hole of diameter considerably smaller than the mean free path of the molecules. Such a hole is often described as a ''pinhole'' and the escap ...

of a gas through a porous barrier is inversely proportional to the square root of the gas's molecular mass

The molecular mass (''m'') is the mass of a given molecule: it is measured in daltons (Da or u). Different molecules of the same compound may have different molecular masses because they contain different isotopes of an element. The related quant ...

. In a container with a porous barrier containing a mixture of two gases, the lighter molecules will pass out of the container more rapidly than the heavier molecules. The gas leaving the container is slightly enriched in the lighter molecules, while the residual gas is slightly depleted. A container wherein the enrichment process takes place through gaseous diffusion is called a diffuser.

Gaseous diffusion had been used to separate isotopes before. Francis William Aston

Francis William Aston FRS (1 September 1877 – 20 November 1945) was a British chemist and physicist who won the 1922 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his discovery, by means of his mass spectrograph, of isotopes in many non-radioactive elements a ...

had used it to partially separate isotopes of neon

Neon is a chemical element with the symbol Ne and atomic number 10. It is a noble gas. Neon is a colorless, odorless, inert monatomic gas under standard conditions, with about two-thirds the density of air. It was discovered (along with krypt ...

in 1931, and Gustav Ludwig Hertz had improved on the method to almost completely separate neon by running it through a series of stages. In the United States, William D. Harkins had used it to separate chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element with the symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between them. Chlorine i ...

. Kistiakowsky was familiar with the work of Charles G. Maier at the Bureau of Mines, who had also used the process to separate gases.

Uranium hexafluoride () was the only known compound of uranium sufficiently volatile to be used in the gaseous diffusion process. Before this could be done, the ''Special Alloyed Materials (SAM) Laboratories'' at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

and the Kellex Corporation had to overcome formidable difficulties to develop a suitable barrier. Fortunately, fluorine

Fluorine is a chemical element with the symbol F and atomic number 9. It is the lightest halogen and exists at standard conditions as a highly toxic, pale yellow diatomic gas. As the most electronegative reactive element, it is extremely reactiv ...

consists of only a single isotope , so that the 1percent difference in molecular weights between and is due solely to the difference in weights of the uranium isotopes. For these reasons, was the only choice as a feedstock

A raw material, also known as a feedstock, unprocessed material, or primary commodity, is a basic material that is used to produce goods, finished goods, energy, or intermediate materials that are feedstock for future finished products. As feeds ...

for the gaseous diffusion process. Uranium hexafluoride, a solid at room temperature, sublimes at at . Applying Graham's law to uranium hexafluoride:

:

where:

:''Rate1'' is the rate of effusion of 235UF6.

:''Rate2'' is the rate of effusion of 238UF6.

:''M1'' is the molar mass

In chemistry, the molar mass of a chemical compound is defined as the mass of a sample of that compound divided by the amount of substance which is the number of moles in that sample, measured in moles. The molar mass is a bulk, not molecular, ...

of 235UF6 ≈ 235 + 6 × 19 = 349g·mol−1

:''M2'' is the molar mass of 238UF6 ≈ 238 + 6 × 19 = 352g·mol−1

Uranium hexafluoride is a highly corrosive substance

A corrosive substance is one that will damage or destroy other substances with which it comes into contact by means of a chemical reaction.

Etymology

The word ''corrosive'' is derived from the Latin verb ''corrodere'', which means ''to gnaw'', ...

. It is an oxidant

An oxidizing agent (also known as an oxidant, oxidizer, electron recipient, or electron acceptor) is a substance in a redox chemical reaction that gains or " accepts"/"receives" an electron from a (called the , , or ). In other words, an oxi ...

and a Lewis acid

A Lewis acid (named for the American physical chemist Gilbert N. Lewis) is a chemical species that contains an empty orbital which is capable of accepting an electron pair from a Lewis base to form a Lewis adduct. A Lewis base, then, is any sp ...

which is able to bind to fluoride

Fluoride (). According to this source, is a possible pronunciation in British English. is an inorganic, monatomic anion of fluorine, with the chemical formula (also written ), whose salts are typically white or colorless. Fluoride salts ty ...

. It reacts with water to form a solid compound, and is very difficult to handle on an industrial scale.

Organization

Booth, Dunning and von Grosse investigated the gaseous diffusion process. In 1941, they were joined by Francis G. Slack fromVanderbilt University

Vanderbilt University (informally Vandy or VU) is a private research university in Nashville, Tennessee. Founded in 1873, it was named in honor of shipping and rail magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, who provided the school its initial $1-million ...

and Willard F. Libby

Willard Frank Libby (December 17, 1908 – September 8, 1980) was an American physical chemist noted for his role in the 1949 development of radiocarbon dating, a process which revolutionized archaeology and palaeontology. For his contributions ...

from the University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public land-grant research university system in the U.S. state of California. The system is composed of the campuses at Berkeley, Davis, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, University of Califor ...

. In July 1941, an Office of Scientific Research and Development

The Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) was an agency of the United States federal government created to coordinate scientific research for military purposes during World War II. Arrangements were made for its creation during May 1 ...

(OSRD) contract was awarded to Columbia University to study gaseous diffusion. With the help of the mathematician Karl P. Cohen

Karl Paley Cohen (February 5, 1913 – April 6, 2012) was a physical chemist who became a mathematical physicist and helped usher in the age of nuclear energy and reactor development. He began his career in 1937 making scientific advances in urani ...

, they built a twelve-stage pilot gaseous diffusion plant at the Pupin Laboratories. Initial tests showed that the stages were not as efficient as the theory would suggest; they would need about 4,600 stages to enrich to 90 percent uranium-235.

A secret contract was awarded to M. W. Kellogg for engineering studies in July 1941. This included the design and construction of a ten-stage pilot gaseous diffusion plant. On 14 December 1942, the Manhattan District, the US Army component of the Manhattan Project, as the effort to develop an atomic bomb became known, contracted Kellogg to design, build and operate a full-scale production plant. Unusually, the contract did not require any guarantees from Kellogg that it could actually accomplish this task. Because the scope of the project was not well defined, Kellogg and the Manhattan District agreed to defer any financial details to a later,

A secret contract was awarded to M. W. Kellogg for engineering studies in July 1941. This included the design and construction of a ten-stage pilot gaseous diffusion plant. On 14 December 1942, the Manhattan District, the US Army component of the Manhattan Project, as the effort to develop an atomic bomb became known, contracted Kellogg to design, build and operate a full-scale production plant. Unusually, the contract did not require any guarantees from Kellogg that it could actually accomplish this task. Because the scope of the project was not well defined, Kellogg and the Manhattan District agreed to defer any financial details to a later, cost-plus contract

A cost-plus contract, also termed a cost plus contract, is a contract such that a contractor is paid for all of its allowed expenses, ''plus'' additional payment to allow for a profit.Kellex Corporation, so the gaseous diffusion project could be kept separate from other company work. "Kell" stood for "Kellogg" and "X" for secret. Kellex operated as a self-contained and autonomous entity. Percival C. Keith, Kellogg's vice president of engineering, was placed in charge of Kellex. He drew extensively on Kellogg to staff the new company, but also had to recruit staff from outside as well. Eventually, Kellex would have over 3,700 employees.

Dunning remained in charge at Columbia until 1May 1943, when the Manhattan District took over the contract from OSRD. By this time Slack's group had nearly 50 members. His was the largest group, and it was working on the most challenging problem: the design of a suitable barrier through which the gas could diffuse. Another 30 scientists and technicians were working in five other groups. Henry A. Boorse was responsible for the pumps; Booth for the cascade test units. Libby handled chemistry, Nier analytical work and Hugh C. Paxton, engineering support. The Army reorganized the research effort at Columbia, which became the Special Alloyed Materials (SAM) Laboratories. Urey was put in charge, Dunning becoming head of one of its divisions. It would remain this way until 1March 1945, when the SAM Laboratories were taken over by

The highly corrosive nature of uranium hexafluoride presented several technological challenges. Pipes and fittings that it came into contact with had to be made of, or

The highly corrosive nature of uranium hexafluoride presented several technological challenges. Pipes and fittings that it came into contact with had to be made of, or

In 1943, Urey brought in Hugh S. Taylor from

In 1943, Urey brought in Hugh S. Taylor from

Union Carbide

Union Carbide Corporation is an American chemical corporation wholly owned subsidiary (since February 6, 2001) by Dow Chemical Company. Union Carbide produces chemicals and polymers that undergo one or more further conversions by customers befo ...

.

The expansion of the SAM Laboratories led to a search for more space. The Nash Garage Building at 3280 Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

was purchased by Columbia University. Originally an automobile dealership, it was just a few blocks from the campus. Major Benjamin K. Hough Jr. was the Manhattan District's Columbia Area engineer, and he moved his offices here too. Kellex was in the Woolworth Building

The Woolworth Building is an early American skyscraper designed by architect Cass Gilbert located at 233 Broadway in the Tribeca neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. It was the tallest building in the world from 1913 to 1930, with a ...

at 233 Broadway in Lower Manhattan

Lower Manhattan (also known as Downtown Manhattan or Downtown New York) is the southernmost part of Manhattan, the central borough for business, culture, and government in New York City, which is the most populated city in the United States with ...

. In January 1943, Lieutenant Colonel James C. Stowers was appointed New York Area Engineer, with responsibility for the entire K-25 Project. His small staff, initially of 20 military and civilian personnel, but which gradually grew to over 70, was co-located in the Woolworth Building. The Manhattan District had its offices nearby at 270 Broadway until it moved to Oak Ridge, Tennessee

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson County, Tennessee, Anderson and Roane County, Tennessee, Roane counties in the East Tennessee, eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of downtown Knoxville, Tennessee, Knoxville. Oak Ridge's popu ...

, in August 1943.

Codename

The codename "K-25" was a combination of the "K" from Kellex, and "25", a World War II-era code designation for uranium-235 (an isotope of element 92,mass number

The mass number (symbol ''A'', from the German word ''Atomgewicht'' tomic weight, also called atomic mass number or nucleon number, is the total number of protons and neutrons (together known as nucleons) in an atomic nucleus. It is approxima ...

235). The term was first used in Kellex internal reports for the end product, enriched uranium, in March 1943. By April 1943, the term "K-25 plant" was being used for the plant that created it. That month, the term "K-25 Project" was applied to the entire project to develop uranium enrichment

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238 ...

using the gaseous diffusion process. When other "K-" buildings were added after the war, "K-25" became the name of the original, larger complex.

Research and development

Diffusers

The highly corrosive nature of uranium hexafluoride presented several technological challenges. Pipes and fittings that it came into contact with had to be made of, or

The highly corrosive nature of uranium hexafluoride presented several technological challenges. Pipes and fittings that it came into contact with had to be made of, or clad

Cladding is an outer layer of material covering another. It may refer to the following:

* Cladding (boiler), the layer of insulation and outer wrapping around a boiler shell

*Cladding (construction), materials applied to the exterior of buildings ...

with nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow t ...

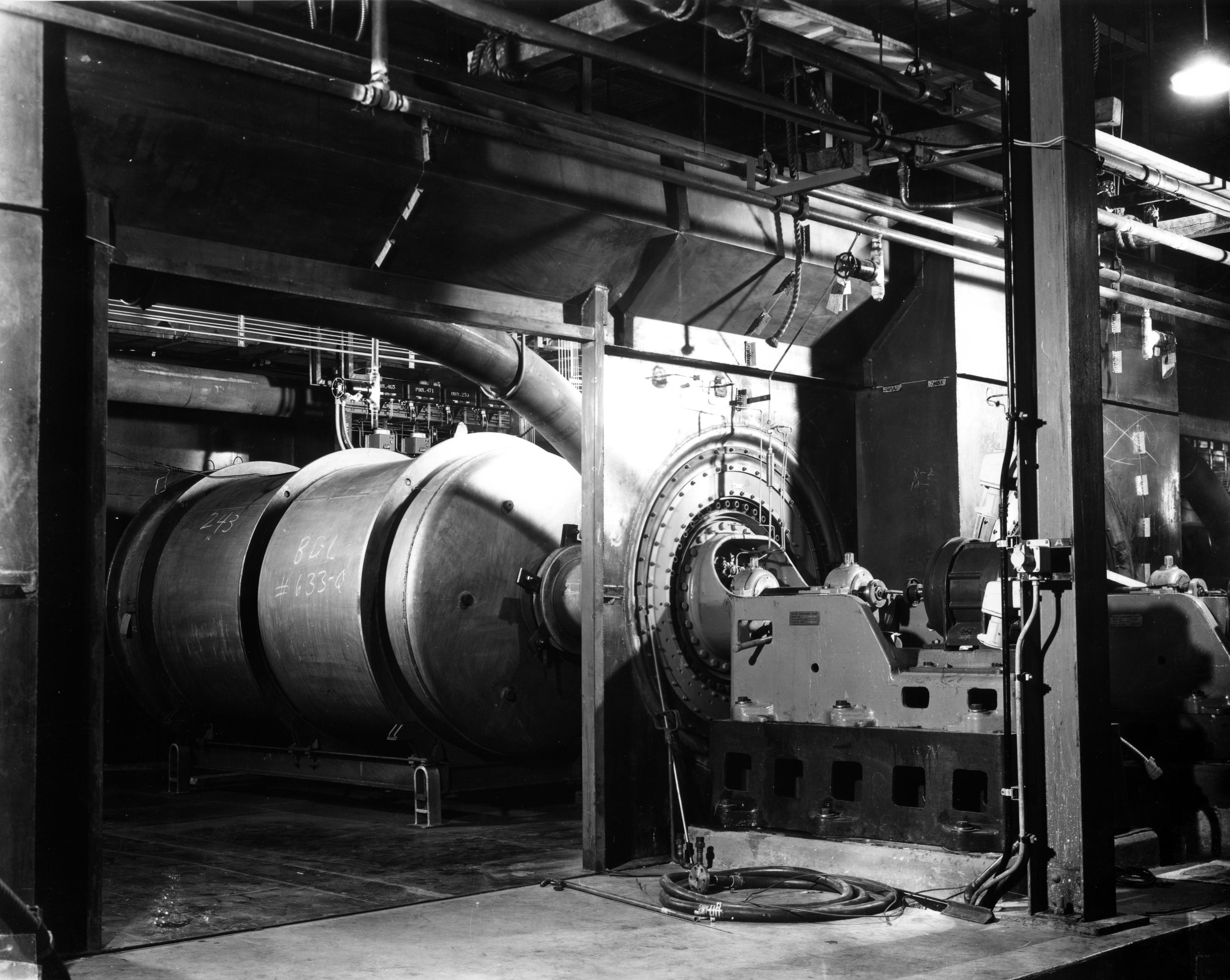

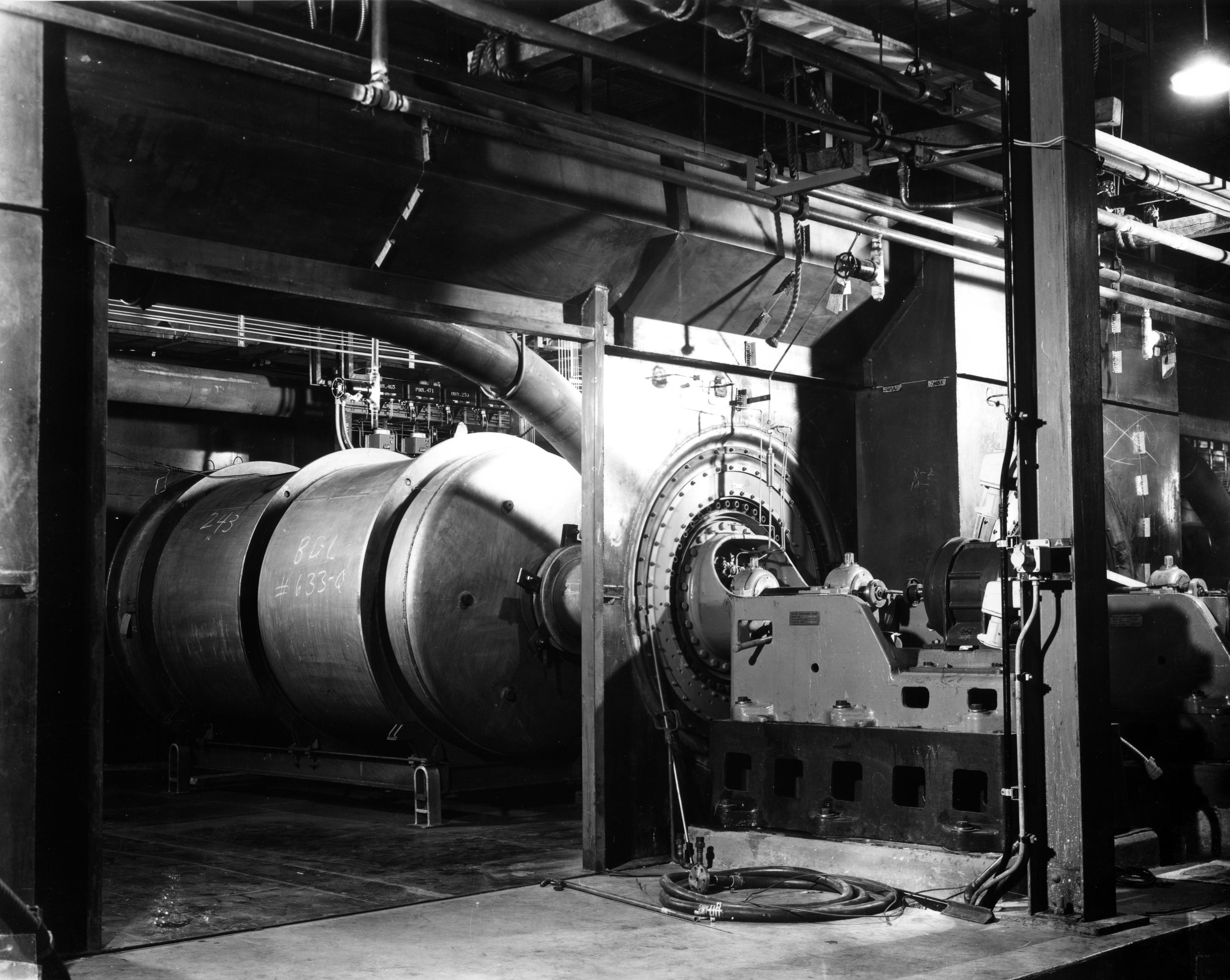

. This was fine for small objects, but impractical for the large diffusers, the tank-like containers that had to hold the gas under pressure. Nickel was a vital war material, and although the Manhattan Project could use its overriding priority to acquire it, making the diffusers out of solid nickel would deplete the national supply. The director of the Manhattan Project, Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

Leslie R. Groves Jr., gave the contract to build the diffusers to Chrysler

Stellantis North America (officially FCA US and formerly Chrysler ()) is one of the " Big Three" automobile manufacturers in the United States, headquartered in Auburn Hills, Michigan. It is the American subsidiary of the multinational automotiv ...

. In turn, its president, K. T. Keller assigned Carl Heussner, an expert in electroplating

Electroplating, also known as electrochemical deposition or electrodeposition, is a process for producing a metal coating on a solid substrate through the reduction of cations of that metal by means of a direct electric current. The part to be ...

, the task of developing a process for electroplating such a large object. Senior Chrysler executives called this "Project X-100".

Electroplating used one-thousandth of the nickel of a solid nickel diffuser. The SAM Laboratories had already attempted this and failed. Heussner experimented with a prototype in a building built within a building, and found that it could be done, so long as the series of pickling

Pickling is the process of preserving or extending the shelf life of food by either anaerobic fermentation in brine or immersion in vinegar. The pickling procedure typically affects the food's texture and flavor. The resulting food is cal ...

and scaling steps required were done without anything coming in contact with oxygen. Chrysler's entire factory at Lynch Road in Detroit was turned over to the manufacture of diffusers. The electroplating process required over of floor space, several thousand workers and a complicated air filtration system to ensure the nickel was not contaminated. By the war's end, Chrysler had built and shipped more than 3,500 diffusers.

Pumps

The gaseous diffusion process required suitable pumps that had to meet stringent requirements. Like the diffusers, they had to resist corrosion from the uranium hexafluoride feed. Corrosion would not only damage the pumps, it would contaminate the feed. They could not afford any leakage of uranium hexafluoride, especially if it was already enriched, or of oil, which would react with the uranium hexafluoride. They had to pump at high rates, and handle a gas twelve times as dense as air. To meet these requirements, the SAM Laboratories chose to usecentrifugal pump

Centrifugal pumps are used to transport fluids by the conversion of rotational kinetic energy to the hydrodynamic energy of the fluid flow. The rotational energy typically comes from an engine or electric motor. They are a sub-class of dynamic ...

s. They were aware that the desired compression ratio

The compression ratio is the ratio between the volume of the cylinder and combustion chamber in an internal combustion engine at their maximum and minimum values.

A fundamental specification for such engines, it is measured two ways: the stati ...

of 2.3:1 to 3.2:1 was unusually high for this type of pump. For some purposes, a reciprocating pump A reciprocating pump is a class of positive-displacement pumps that includes the piston pump, plunger pump, and diaphragm pump. Well maintained, reciprocating pumps can last for decades. Unmaintained, however, they can succumb to wear and tear. ...

would suffice, and these were designed by Boorse at the SAM Laboratories, while Ingersoll Rand

Ingersoll Rand is an American multinational company that provides flow creation and industrial products. The company was formed in February 2020 through the spinoff of the industrial segment of Ingersoll-Randplc (now known as Trane Technologies) ...

tackled the centrifugal pumps.

In early 1943, Ingersoll Rand pulled out. Keith approached the Clark Compressor Company and Worthington Pump and Machinery but they turned it down, saying it could not be done. So Keith and Groves saw executives at Allis-Chalmers

Allis-Chalmers was a U.S. manufacturer of machinery for various industries. Its business lines included agricultural equipment, construction equipment, power generation and power transmission equipment, and machinery for use in industrial s ...

, who agreed to build a new factory to produce the pumps, even though the pump design was still uncertain. The SAM Laboratories came up with a design, and Westinghouse built some prototypes that were successfully tested. Then Judson Swearingen at the Elliott Company

Elliott Company designs, manufactures, installs, and services turbo-machinery for Tractor unit, prime movers and rotating machinery. Headquartered in Jeannette, Pennsylvania, Elliott Company is a wholly owned subsidiary of the Japan-based company ...

came up with a revolutionary and promising design that was mechanically stable with seals that would contain the gas. This design was manufactured by Allis-Chalmers.

Barriers

Difficulties with the diffusers and pumps paled into insignificance besides those with the porous barrier. To work, the gaseous diffusion process required a barrier with microscopic holes, but not subject to plugging. It had to be extremely porous, but strong enough to handle the high pressures. And, like everything else, it had to resist corrosion from uranium hexafluoride. The latter criterion suggested a nickel barrier. Foster C. Nix at theBell Telephone Laboratories

Nokia Bell Labs, originally named Bell Telephone Laboratories (1925–1984),

then AT&T Bell Laboratories (1984–1996)

and Bell Labs Innovations (1996–2007),

is an American industrial research and scientific development company owned by mult ...

experimented with nickel powder, while Edward O. Norris at the C. O. Jelliff Manufacturing Corporation and Edward Adler at the City College of New York

The City College of the City University of New York (also known as the City College of New York, or simply City College or CCNY) is a public university within the City University of New York (CUNY) system in New York City. Founded in 1847, Cit ...

worked on a design with electroplated metallic nickel. Norris was an English interior decorator, who had developed a very fine metal mesh for use with a spray gun

Spray painting is a painting technique in which a device sprays coating material (paint, ink, varnish, etc.) through the air onto a surface. The most common types employ compressed gas—usually air—to atomize and direct the paint particles.

...

. Their design appeared too brittle and fragile for the proposed use, particularly on the higher stages of enrichment, but there was hope that this could be overcome.

In 1943, Urey brought in Hugh S. Taylor from

In 1943, Urey brought in Hugh S. Taylor from Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

to look at the problem of a usable barrier. Libby made progress on understanding the chemistry of uranium hexafluoride, leading to ideas on how to prevent corrosion and plugging. Chemical researchers at the SAM Laboratories studied fluorocarbons

Fluorocarbons are chemical compounds with carbon-fluorine bonds. Compounds that contain many C-F bonds often has distinctive properties, e.g., enhanced stability, volatility, and hydrophobicity. Fluorocarbons and their derivatives are commerci ...

, which resisted corrosion, and could be used as lubricants and coolants in the gaseous diffusion plant. Despite this progress, the K-25 Project was in serious trouble without a suitable barrier, and by August 1943 it was facing cancellation. On 13 August Groves informed the Military Policy Committee, the senior committee that steered the Manhattan Project, that gaseous diffusion enrichment in excess of fifty percent was probably infeasible, and the gaseous diffusion plant would be limited to producing product with a lower enrichment which could be fed into the calutron

A calutron is a mass spectrometer originally designed and used for separating the isotopes of uranium. It was developed by Ernest Lawrence during the Manhattan Project and was based on his earlier invention, the cyclotron. Its name was deri ...

s of the Y-12 electromagnetic plant. Urey therefore began preparations to mass-produce the Norris-Adler barrier, despite its problems.

Meanwhile, Union Carbide and Kellex had made researchers at the Bakelite Corporation, a subsidiary of Union Carbide, aware of Nix's unsuccessful efforts with powdered nickel barriers. To Frazier Groff and other researchers at Bakelite's laboratories in Bound Brook, New Jersey

Bound Brook is a borough in Somerset County, New Jersey, United States, located along the Raritan River. At the 2010 United States Census, the borough's population was 10,402,Jersey City, New Jersey

Jersey City is the second-most populous city in the U.S. state of New Jersey, after Newark.Wallace Akers and fifteen members of the British gaseous diffusion project, who would review the progress made thus far. Their verdict was that while the new barrier was potentially superior, Keith's undertaking to build a new facility to produce the new barrier in just four months, produce all the barriers required in another four and have the production facility up and running in just twelve "would be something of a miraculous achievement". On 16 January 1944, Groves ruled in favor of the Johnson barrier. Johnson built a pilot plant for the new process at the Nash Building. Taylor analyzed the sample barriers produced and pronounced only 5percent of them to be of acceptable quality. Edward Mack Jr. created his own pilot plant at Schermerhorn Hall at Columbia, and Groves obtained of nickel from the

Construction began before completion of the design for the gaseous diffusion process. Because of the large amount of electric power the K-25 plant was expected to consume, it was decided to provide it with its own electric power plant. While the

Construction began before completion of the design for the gaseous diffusion process. Because of the large amount of electric power the K-25 plant was expected to consume, it was decided to provide it with its own electric power plant. While the

It was initially intended that the construction workers should live off-site, but the poor condition of the roads and a shortage of accommodations in the area made commuting long and difficult, and in turn made it difficult to find and retain workers. Construction workers therefore came to be housed in large hutment and trailer camps. The J. A. Jones camp for K-25 workers, known as Happy Valley, held 15,000 people. This required 8dormitories, 17 barracks, 1,590 hutments, 1,153 trailers and 100 Victory Houses. A pumping station was built to supply drinking water from the Clinch River, along with a water treatment plant. Amenities included a school, eight cafeterias, a bakery, theater, three recreation halls, a warehouse and a cold storage plant. Ford, Bacon & Davis established a smaller camp for 2,100 people. Responsibility for the camps was transferred to the Roane-Anderson Company on 25 January 1946, and the school was transferred to district control in March 1946.

Work began on the main facility area on 20 October 1943. Although generally flat, some of soil and rock had to be excavated from areas up to high, and six major areas had to be filled in, to a maximum depth of . Normally buildings containing complicated heavy machinery would rest on concrete columns down to the bedrock, but this would have required thousands of columns of different length. To save time

It was initially intended that the construction workers should live off-site, but the poor condition of the roads and a shortage of accommodations in the area made commuting long and difficult, and in turn made it difficult to find and retain workers. Construction workers therefore came to be housed in large hutment and trailer camps. The J. A. Jones camp for K-25 workers, known as Happy Valley, held 15,000 people. This required 8dormitories, 17 barracks, 1,590 hutments, 1,153 trailers and 100 Victory Houses. A pumping station was built to supply drinking water from the Clinch River, along with a water treatment plant. Amenities included a school, eight cafeterias, a bakery, theater, three recreation halls, a warehouse and a cold storage plant. Ford, Bacon & Davis established a smaller camp for 2,100 people. Responsibility for the camps was transferred to the Roane-Anderson Company on 25 January 1946, and the school was transferred to district control in March 1946.

Work began on the main facility area on 20 October 1943. Although generally flat, some of soil and rock had to be excavated from areas up to high, and six major areas had to be filled in, to a maximum depth of . Normally buildings containing complicated heavy machinery would rest on concrete columns down to the bedrock, but this would have required thousands of columns of different length. To save time  Kellex's design for the main process building of K-25 called for a four-story U-shaped structure long containing 51 main process buildings and 3purge cascade buildings. These were divided into nine sections. Within these were cells of six stages. The cells could be operated independently, or consecutively, within a section. Similarly, the sections could be operated separately or as part of a single cascade. When completed, there were 2,892 stages. The basement housed the auxiliary equipment, such as the transformers, switch gears, and air conditioning systems. The ground floor contained the cells. The third level contained the piping. The fourth floor was the operating floor, which contained the control room, and the hundreds of instrument panels. From here, the operators monitored the process. The first section was ready for test runs on 17 April 1944, although the barriers were not yet ready to be installed.

The main process building surpassed

Kellex's design for the main process building of K-25 called for a four-story U-shaped structure long containing 51 main process buildings and 3purge cascade buildings. These were divided into nine sections. Within these were cells of six stages. The cells could be operated independently, or consecutively, within a section. Similarly, the sections could be operated separately or as part of a single cascade. When completed, there were 2,892 stages. The basement housed the auxiliary equipment, such as the transformers, switch gears, and air conditioning systems. The ground floor contained the cells. The third level contained the piping. The fourth floor was the operating floor, which contained the control room, and the hundreds of instrument panels. From here, the operators monitored the process. The first section was ready for test runs on 17 April 1944, although the barriers were not yet ready to be installed.

The main process building surpassed

The fluorine generating plant (K-1300) generated, bottled and stored fluorine. It had not been in great demand before the war, and Kellex and the Manhattan District considered four different processes for large-scale production. A process developed by the

The fluorine generating plant (K-1300) generated, bottled and stored fluorine. It had not been in great demand before the war, and Kellex and the Manhattan District considered four different processes for large-scale production. A process developed by the

The preliminary specification for the K-25 plant in March 1943 called for it to produce a day of product that was 90 percent uranium-235. As the practical difficulties were realized, this target was reduced to 36 percent. On the other hand, the cascade design meant construction did not need to be complete before the plant started operating. In August 1943, Kellex submitted a schedule that called for a capability to produce material enriched to 5percent uranium-235 by 1June 1945, 15 percent by 1July 1945, and 36 percent by 23 August 1945. This schedule was revised in August 1944 to 0.9 percent by 1January 1945, 5percent by 10 June 1945, 15 percent by 1August 1945, 23 percent by 13 September 1945, and 36 percent as soon as possible after that.

A meeting between the Manhattan District and Kellogg on 12 December 1942 recommended the K-25 plant be operated by Union Carbide. This would be through a wholly owned subsidiary, Carbon and Carbide Chemicals. A cost-plus-fixed-fee contract was signed on 18 January 1943, setting the fee at $75,000 per month. This was later increased to $96,000 a month to operate both K-25 and K-27. Union Carbide did not wish to be the sole operator of the facility. Union Carbide suggested the conditioning plant be built and operated by Ford, Bacon & Davis. The Manhattan District found this acceptable, and a cost-plus-fixed-fee contract was negotiated with a fee of $216,000 for services up to the end of June 1945. The contract was terminated early on 1May 1945, when Union Carbide took over the plant. Ford, Bacon & Davis was therefore paid $202,000. The other exception was the fluorine plant. Hooker Chemical was asked to supervise its construction of the fluorine plant, and initially to operate it for a fixed fee of $24,500. The plant was turned over to Union Carbide on 1February 1945.

The preliminary specification for the K-25 plant in March 1943 called for it to produce a day of product that was 90 percent uranium-235. As the practical difficulties were realized, this target was reduced to 36 percent. On the other hand, the cascade design meant construction did not need to be complete before the plant started operating. In August 1943, Kellex submitted a schedule that called for a capability to produce material enriched to 5percent uranium-235 by 1June 1945, 15 percent by 1July 1945, and 36 percent by 23 August 1945. This schedule was revised in August 1944 to 0.9 percent by 1January 1945, 5percent by 10 June 1945, 15 percent by 1August 1945, 23 percent by 13 September 1945, and 36 percent as soon as possible after that.

A meeting between the Manhattan District and Kellogg on 12 December 1942 recommended the K-25 plant be operated by Union Carbide. This would be through a wholly owned subsidiary, Carbon and Carbide Chemicals. A cost-plus-fixed-fee contract was signed on 18 January 1943, setting the fee at $75,000 per month. This was later increased to $96,000 a month to operate both K-25 and K-27. Union Carbide did not wish to be the sole operator of the facility. Union Carbide suggested the conditioning plant be built and operated by Ford, Bacon & Davis. The Manhattan District found this acceptable, and a cost-plus-fixed-fee contract was negotiated with a fee of $216,000 for services up to the end of June 1945. The contract was terminated early on 1May 1945, when Union Carbide took over the plant. Ford, Bacon & Davis was therefore paid $202,000. The other exception was the fluorine plant. Hooker Chemical was asked to supervise its construction of the fluorine plant, and initially to operate it for a fixed fee of $24,500. The plant was turned over to Union Carbide on 1February 1945.

Part of the K-300 complex was taken over by Union Carbide in August 1944, and was run as a pilot plant, training operators and developing procedures, using nitrogen instead of uranium hexafluoride until October 1944, and then

Part of the K-300 complex was taken over by Union Carbide in August 1944, and was run as a pilot plant, training operators and developing procedures, using nitrogen instead of uranium hexafluoride until October 1944, and then  With the end of the war in August 1945, the Manhattan Project's priority shifted from speed to economy and efficiency. The cascades were configurable, so they could produce a large amount of slightly enriched product by running them in parallel, or a small amount of highly enriched product through running them in series. By early 1946, with K-27 in operation, the facility was producing per day, enriched to 30 percent. The next step was to increase the enrichment further to 60 percent. This was achieved on 20 July 1946. This presented a problem, because Y-12 was not equipped to handle feed that was so highly enriched, but the

With the end of the war in August 1945, the Manhattan Project's priority shifted from speed to economy and efficiency. The cascades were configurable, so they could produce a large amount of slightly enriched product by running them in parallel, or a small amount of highly enriched product through running them in series. By early 1946, with K-27 in operation, the facility was producing per day, enriched to 30 percent. The next step was to increase the enrichment further to 60 percent. This was achieved on 20 July 1946. This presented a problem, because Y-12 was not equipped to handle feed that was so highly enriched, but the

K-25 became a prototype for other gaseous diffusion facilities established in the early post-war years. The first of these was the K-27 completed in September 1945. It was followed by the K-29 in 1951, the K-31 in 1951 and the K-33 in 1954. Further gaseous diffusion facilities were built at

K-25 became a prototype for other gaseous diffusion facilities established in the early post-war years. The first of these was the K-27 completed in September 1945. It was followed by the K-29 in 1951, the K-31 in 1951 and the K-33 in 1954. Further gaseous diffusion facilities were built at  Centrifuge cascades began operating at Oak Ridge in 1961. A gas centrifuge test facility (K-1210) opened in 1975, followed by a larger centrifuge plant demonstration facility (K-1220) in 1982. In response to an order from President

Centrifuge cascades began operating at Oak Ridge in 1961. A gas centrifuge test facility (K-1210) opened in 1975, followed by a larger centrifuge plant demonstration facility (K-1220) in 1982. In response to an order from President

K-25 History Center

on-site museum

K-25 Virtual MuseumHistoric photos of K25 by Ed WestcottDemolition of the north end of the K-25 building (Video)

*

International Nickel Company

Vale Canada Limited (formerly Vale Inco, CVRD Inco and Inco Limited; for corporate branding purposes simply known as "Vale" and pronounced in English) is a wholly owned subsidiary of the Brazilian mining company Vale. Vale's nickel mining and ...

. With plenty of nickel to work with, by April 1944, both pilot plants were producing barriers of acceptable quality 45 percent of the time.

Construction

The site chosen was at theClinton Engineer Works

The Clinton Engineer Works (CEW) was the production installation of the Manhattan Project that during World War II produced the enriched uranium used in the 1945 bombing of Hiroshima, as well as the first examples of reactor-produced plu ...

in Tennessee. The area was inspected by representatives of the Manhattan District, Kellex and Union Carbide on 18 January 1943. Consideration was also given to sites near the Shasta Dam

Shasta Dam (called Kennett Dam before its construction) is a concrete arch-gravity dam across the Sacramento River in Northern California in the United States. At high, it is the eighth-tallest dam in the United States. Located at the north ...

in California and the Big Bend of the Columbia River in Washington state. The lower humidity of these areas made them more suitable for a gaseous diffusion plant, but the Clinton Engineer Works site was immediately available and otherwise suitable. Groves decided on the site in April 1943.

Under the contract, Kellex had responsibility not just for the design and engineering of the K-25 plant, but for its construction as well. The prime construction contractor was J. A. Jones Construction from Charlotte, North Carolina

Charlotte ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of North Carolina. Located in the Piedmont region, it is the county seat of Mecklenburg County. The population was 874,579 at the 2020 census, making Charlotte the 16th-most popu ...

. It had impressed Groves with its work on several major Army construction projects, such as Camp Shelby, Mississippi

Camp Shelby is a military post whose North Gate is located at the southern boundary of Hattiesburg, Mississippi, on United States Highway 49. It is the largest state-owned training site in the nation. During wartime, the camp's mission is to s ...

. There were more than sixty subcontractors. Kellex engaged another construction company, Ford, Bacon & Davis, to build the fluorine and nitrogen facilities, and the conditioning plant. Construction work was initially the responsibility of Lieutenant Colonel Warren George, the Chief of the Construction Division of the Clinton Engineer Works. Major W. P. Cornelius became the construction officer responsible for K-25 works on 31 July 1943. He was answerable to Stowers back in Manhattan. He became Chief of the Construction Division on 1March 1946. J. J. Allison was the resident engineer from Kellex, and Edwin L. Jones, the General Manager of J. A. Jones.

Power plant

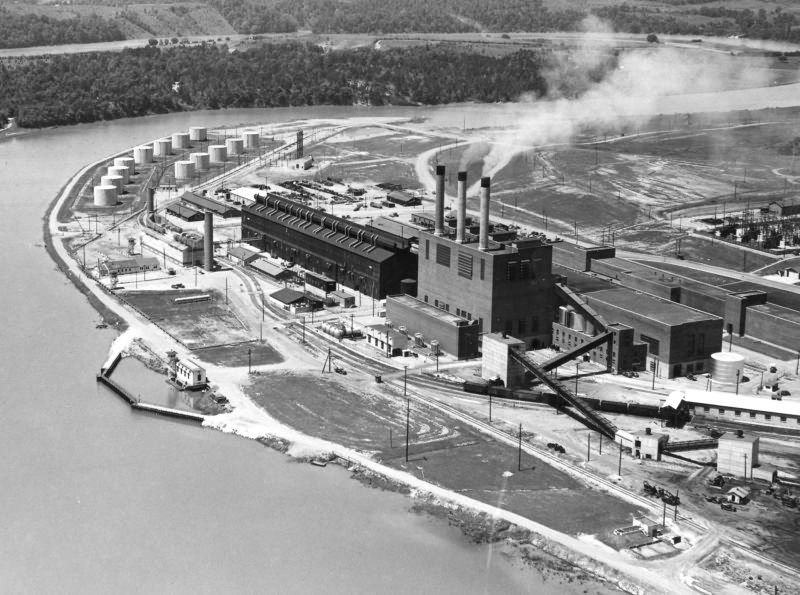

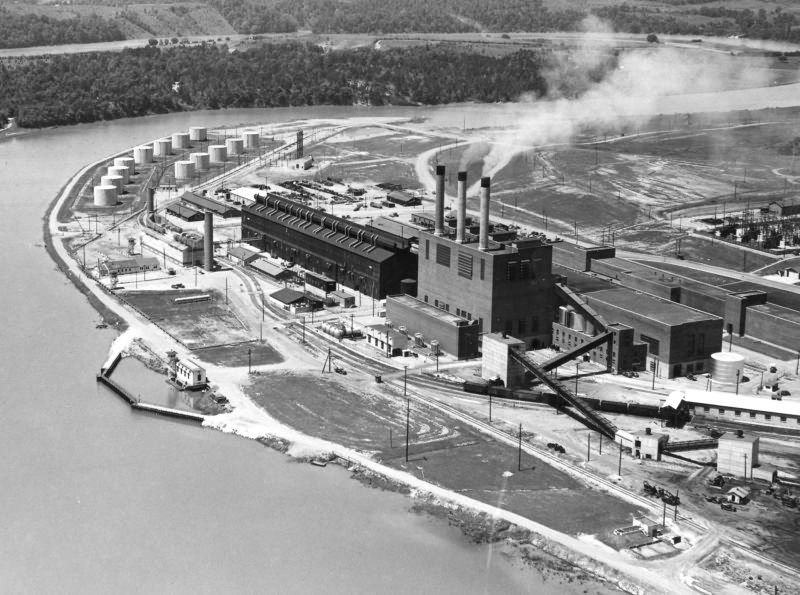

Construction began before completion of the design for the gaseous diffusion process. Because of the large amount of electric power the K-25 plant was expected to consume, it was decided to provide it with its own electric power plant. While the

Construction began before completion of the design for the gaseous diffusion process. Because of the large amount of electric power the K-25 plant was expected to consume, it was decided to provide it with its own electric power plant. While the Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolin ...

(TVA) believed it could supply the Clinton Engineer Works' needs, there was unease about relying on a single supplier when a power failure could cost the gaseous diffusion plant weeks of work, and the lines to TVA could be sabotaged. A local plant was more secure. The Kellex engineers were also attracted to the idea of being able to generate the variable frequency current required by the gaseous diffusion process without complicated transformers.

A site was chosen for this on the western edge of the Clinton Engineer Works site where it could draw cold water from the Clinch River

The Clinch River is a river that flows southwest for more than through the Great Appalachian Valley in the U.S. states of Virginia and Tennessee, gathering various tributaries, including the Powell River, before joining the Tennessee River in Ki ...

and discharge warm water into Poplar Creek without affecting the inflow. Groves approved this location on 3May 1943. Surveying began on the power plant site on 31 May 1943, and J. A. Jones started construction work the following day. Because the bedrock was below the surface, the power plant was supported on 40 concrete-filled caissons

Caisson (French for "box") may refer to:

* Caisson (Asian architecture), a spider web ceiling

* Caisson (engineering), a sealed underwater structure

* Caisson (lock gate), a gate for a dock or lock, constructed as a floating caisson

* Caisson (p ...

. Installation of the first boiler commenced in October 1943. Construction work was complete by late September. To prevent sabotage, the power plant was connected to the gaseous diffusion plant by an underground conduit. Despite this, there was one act of sabotage, in which a nail was driven through the electric cable. The culprit was never found, but was considered more likely to be a disgruntled employee than an Axis spy.

Electric power in the United States was generated at 60 hertz; the power house was able to generate variable frequencies between 45 and 60 hertz, and constant frequencies of 60 and 120 hertz. This capability was not ultimately required, and all but one of the K-25 systems ran on a constant 60 hertz, the exception using a constant 120 hertz. The first coal-fired boiler was started on 7April 1944, followed by the second on 14 July 1944 and the third on 2November 1944. Each produced of steam an hour at a pressure of and a temperature of . To obtain the fourteen turbine generators needed, Groves had to use the Manhattan Project's priority to overrule Julius Albert Krug

Julius Albert Krug (November 23, 1907March 26, 1970) was a politician who served as the United States Secretary of the Interior for the administration of President Harry S. Truman from 1946 until 1949.

Early life and education

Krug was born Novem ...

, the director of the Office of War Utilities. The turbine generators had a combined output of 238,000 kilowatts. The power plant could also receive power from TVA. It was decommissioned in the 1960s and demolished in 1995.

Gaseous diffusion plant

A site for the K-25 facility was chosen near the high school of the now-abandoned town ofWheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

. As the dimensions of the K-25 facility became more apparent, it was decided to move it to a larger site near Poplar Creek, closer to the power plant. This site was approved on 24 June 1943. Considerable work was required to prepare the site. Existing roads in the area were improved to take heavy traffic. A new road was built to connect the site to US Route 70, and another, long, to connect with Tennessee State Route 61. An old ferry over the Clinch River was upgraded, and then replaced with a bridge in December 1943. A railroad spur was run from Blair, Tennessee, to the K-25 site. Some of sidings were also provided. The first carload of freight traversed the line on 18 September 1943.

It was initially intended that the construction workers should live off-site, but the poor condition of the roads and a shortage of accommodations in the area made commuting long and difficult, and in turn made it difficult to find and retain workers. Construction workers therefore came to be housed in large hutment and trailer camps. The J. A. Jones camp for K-25 workers, known as Happy Valley, held 15,000 people. This required 8dormitories, 17 barracks, 1,590 hutments, 1,153 trailers and 100 Victory Houses. A pumping station was built to supply drinking water from the Clinch River, along with a water treatment plant. Amenities included a school, eight cafeterias, a bakery, theater, three recreation halls, a warehouse and a cold storage plant. Ford, Bacon & Davis established a smaller camp for 2,100 people. Responsibility for the camps was transferred to the Roane-Anderson Company on 25 January 1946, and the school was transferred to district control in March 1946.

Work began on the main facility area on 20 October 1943. Although generally flat, some of soil and rock had to be excavated from areas up to high, and six major areas had to be filled in, to a maximum depth of . Normally buildings containing complicated heavy machinery would rest on concrete columns down to the bedrock, but this would have required thousands of columns of different length. To save time

It was initially intended that the construction workers should live off-site, but the poor condition of the roads and a shortage of accommodations in the area made commuting long and difficult, and in turn made it difficult to find and retain workers. Construction workers therefore came to be housed in large hutment and trailer camps. The J. A. Jones camp for K-25 workers, known as Happy Valley, held 15,000 people. This required 8dormitories, 17 barracks, 1,590 hutments, 1,153 trailers and 100 Victory Houses. A pumping station was built to supply drinking water from the Clinch River, along with a water treatment plant. Amenities included a school, eight cafeterias, a bakery, theater, three recreation halls, a warehouse and a cold storage plant. Ford, Bacon & Davis established a smaller camp for 2,100 people. Responsibility for the camps was transferred to the Roane-Anderson Company on 25 January 1946, and the school was transferred to district control in March 1946.

Work began on the main facility area on 20 October 1943. Although generally flat, some of soil and rock had to be excavated from areas up to high, and six major areas had to be filled in, to a maximum depth of . Normally buildings containing complicated heavy machinery would rest on concrete columns down to the bedrock, but this would have required thousands of columns of different length. To save time soil compaction

In geotechnical engineering, soil compaction is the process in which stress applied to a soil causes densification as air is displaced from the pores between the soil grains. When stress is applied that causes densification due to water (or othe ...

was used instead. Layers were laid down and compacted with sheepsfoot rollers in the areas that had to be filled in, and the footings were laid over compacted soil in the low-lying areas and the undisturbed soil in the areas that had been excavated. Activities overlapped, so concrete pouring began while grading was still going on. Cranes

Crane or cranes may refer to:

Common meanings

* Crane (bird), a large, long-necked bird

* Crane (machine), industrial machinery for lifting

** Crane (rail), a crane suited for use on railroads

People and fictional characters

* Crane (surname ...

started lifting the steel frames into place on 19 January 1944.

Kellex's design for the main process building of K-25 called for a four-story U-shaped structure long containing 51 main process buildings and 3purge cascade buildings. These were divided into nine sections. Within these were cells of six stages. The cells could be operated independently, or consecutively, within a section. Similarly, the sections could be operated separately or as part of a single cascade. When completed, there were 2,892 stages. The basement housed the auxiliary equipment, such as the transformers, switch gears, and air conditioning systems. The ground floor contained the cells. The third level contained the piping. The fourth floor was the operating floor, which contained the control room, and the hundreds of instrument panels. From here, the operators monitored the process. The first section was ready for test runs on 17 April 1944, although the barriers were not yet ready to be installed.

The main process building surpassed

Kellex's design for the main process building of K-25 called for a four-story U-shaped structure long containing 51 main process buildings and 3purge cascade buildings. These were divided into nine sections. Within these were cells of six stages. The cells could be operated independently, or consecutively, within a section. Similarly, the sections could be operated separately or as part of a single cascade. When completed, there were 2,892 stages. The basement housed the auxiliary equipment, such as the transformers, switch gears, and air conditioning systems. The ground floor contained the cells. The third level contained the piping. The fourth floor was the operating floor, which contained the control room, and the hundreds of instrument panels. From here, the operators monitored the process. The first section was ready for test runs on 17 April 1944, although the barriers were not yet ready to be installed.

The main process building surpassed The Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a metony ...

as the largest building in the world, with a floor area of , and an enclosed volume of . Construction required of concrete, and of gas pipes. Because uranium hexafluoride corrodes steel, and steel piping had to be coated in nickel, smaller pipes were made of copper or monel

Monel is a group of alloys of nickel (from 52 to 67%) and copper, with small amounts of iron, manganese, carbon, and silicon. Monel is not a cupronickel alloy because it has less than 60% copper.

Stronger than pure nickel, Monel alloys are res ...

. The equipment operated under vacuum pressures, so plumbing had to be air tight. Special efforts were made to create as clean an environment as possible to areas where piping or fixtures were being installed. J. A. Jones established a special cleanliness unit on 18 April 1944. Buildings were completely sealed off, air was filtered, and all cleaning was with vacuum cleaners and mopping. Workers wore white lintless gloves. At the peak of construction activity in May 1945, 25,266 people were employed on the site.

Other buildings

Although by far the largest, the main process building (K-300) was but one of many that made up the facility. There was a conditioning building (K-1401), where piping and equipment were cleaned prior to installation. A feed purification building (K-101), was built to remove impurities from the uranium hexafluoride, but never operated as such because the suppliers provided feed good enough to be fed into the gaseous diffusion process. The three-story surge and waste removal building (K-601) processed the "tail" stream ofdepleted uranium hexafluoride

Depleted uranium hexafluoride (DUHF; also referred to as depleted uranium tails, depleted uranium tailings or DUF6) is a byproduct of the processing of uranium hexafluoride into enriched uranium. It is one of the chemical forms of depleted uranium ...

. The air conditioning building (K-1401) provided per minute of clean, dry air. K-1201 compressed the air. The nitrogen plant (K-1408) provided gas for use as a pump sealant and to protect equipment from moist air.

The fluorine generating plant (K-1300) generated, bottled and stored fluorine. It had not been in great demand before the war, and Kellex and the Manhattan District considered four different processes for large-scale production. A process developed by the

The fluorine generating plant (K-1300) generated, bottled and stored fluorine. It had not been in great demand before the war, and Kellex and the Manhattan District considered four different processes for large-scale production. A process developed by the Hooker Chemical Company

Hooker Chemical Company (or Hooker Electrochemical Company) was an American firm producing chloralkali products from 1903 to 1968. In 1922, bought the S. Wander & Sons Company to sell lye and chlorinated lime. The company became notorious in ...

was chosen. Owing to the hazardous nature of fluorine, it was decided that shipping it across the United States was inadvisable, and it should be manufactured on site at the Clinton Engineer Works. Two pump houses (K-801 and K-802) and two cooling towers (H-801 and H-802) provided of cooling water per day for the motors and compressors.

The administration building (K-1001) provided of office space. A laboratory building (K-1401) contained facilities for testing and analyzing feed and product. Five drum warehouses (K-1025-A to -E) had of floor space to store drums of uranium hexafluoride. Originally this was on the K-27 site. The buildings were moved on a truck to make way for K-27. There were also warehouses for general stores (K-1035), spare parts (K-1036) and equipment (K-1037). A cafeteria (K-1002) provided meal facilities, including a segregated lunch room for African Americans. There were three changing houses (K-1008-A, B and C), a dispensary (K-1003), an instrument repair building (K-1024), and a fire station (K-1021).

In mid-January 1945, Kellex proposed an extension to K-25 to allow product enrichment of up to 85 percent. Grove initially approved this, but later canceled it in favor of a 540-stage side feed unit, which became known as K-27, which could process a slightly enriched product. This could then be fed into K-25 or the calutrons at the Y-12. Kellex estimated that using the enriched feed from K-27 could lift the output from K-25 from 35 to 60 percent uranium-235. Construction started at K-27 on 3April 1945, and was completed in December 1945. The construction work was expedited by making it "virtually a Chinese copy" of a section of K-25. By 31 December 1946, when the Manhattan Project ended, 110,048,961 man-hours of construction work had been performed at the K-25 site. The total cost, including that of K-27, was $479,589,999 (equivalent to $ in ).

The water tower (K-1206-F) was a structure that held of water. It was built in 1958 by the Chicago Bridge and Iron Company

CB&I is a large engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) company with its administrative headquarters in The Woodlands, Texas. CB&I specializes in projects for oil and gas companies. CB&I employs more than 32,000 people worldwide. In May ...

and served as reservoir for the fire suppression system. Over of steel was used in its construction. It operated until 3 June 2013, when the valves were turned off. It was then drained and disconnected, and was taken out of service on 15 July. On 3 August 2013, it was demolished with explosives.

Operations

The preliminary specification for the K-25 plant in March 1943 called for it to produce a day of product that was 90 percent uranium-235. As the practical difficulties were realized, this target was reduced to 36 percent. On the other hand, the cascade design meant construction did not need to be complete before the plant started operating. In August 1943, Kellex submitted a schedule that called for a capability to produce material enriched to 5percent uranium-235 by 1June 1945, 15 percent by 1July 1945, and 36 percent by 23 August 1945. This schedule was revised in August 1944 to 0.9 percent by 1January 1945, 5percent by 10 June 1945, 15 percent by 1August 1945, 23 percent by 13 September 1945, and 36 percent as soon as possible after that.

A meeting between the Manhattan District and Kellogg on 12 December 1942 recommended the K-25 plant be operated by Union Carbide. This would be through a wholly owned subsidiary, Carbon and Carbide Chemicals. A cost-plus-fixed-fee contract was signed on 18 January 1943, setting the fee at $75,000 per month. This was later increased to $96,000 a month to operate both K-25 and K-27. Union Carbide did not wish to be the sole operator of the facility. Union Carbide suggested the conditioning plant be built and operated by Ford, Bacon & Davis. The Manhattan District found this acceptable, and a cost-plus-fixed-fee contract was negotiated with a fee of $216,000 for services up to the end of June 1945. The contract was terminated early on 1May 1945, when Union Carbide took over the plant. Ford, Bacon & Davis was therefore paid $202,000. The other exception was the fluorine plant. Hooker Chemical was asked to supervise its construction of the fluorine plant, and initially to operate it for a fixed fee of $24,500. The plant was turned over to Union Carbide on 1February 1945.

The preliminary specification for the K-25 plant in March 1943 called for it to produce a day of product that was 90 percent uranium-235. As the practical difficulties were realized, this target was reduced to 36 percent. On the other hand, the cascade design meant construction did not need to be complete before the plant started operating. In August 1943, Kellex submitted a schedule that called for a capability to produce material enriched to 5percent uranium-235 by 1June 1945, 15 percent by 1July 1945, and 36 percent by 23 August 1945. This schedule was revised in August 1944 to 0.9 percent by 1January 1945, 5percent by 10 June 1945, 15 percent by 1August 1945, 23 percent by 13 September 1945, and 36 percent as soon as possible after that.