Sürgünlik on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The deportation of the Crimean Tatars ( crh, Qırımtatar halqınıñ sürgünligi,

The Crimean Tatars controlled the Crimean Khanate from 1441 to 1783, when Crimea was annexed by the Russian Empire as a target of

The Crimean Tatars controlled the Crimean Khanate from 1441 to 1783, when Crimea was annexed by the Russian Empire as a target of  After the 1917 October Revolution, Crimea received autonomous status inside the USSR on 18 October 1921, but collectivization in the 1920s led to severe famine from which up to 100,000 Crimeans perished when their crops were transported to "more important" regions of the Soviet Union. By one estimate, three-quarters of the famine victims were Crimean Tatars. Their status deteriorated further after Joseph Stalin became the Soviet leader and implemented repressions that led to the deaths of at least 5.2 million Soviet citizens between 1927 and 1938.

After the 1917 October Revolution, Crimea received autonomous status inside the USSR on 18 October 1921, but collectivization in the 1920s led to severe famine from which up to 100,000 Crimeans perished when their crops were transported to "more important" regions of the Soviet Union. By one estimate, three-quarters of the famine victims were Crimean Tatars. Their status deteriorated further after Joseph Stalin became the Soviet leader and implemented repressions that led to the deaths of at least 5.2 million Soviet citizens between 1927 and 1938.

Officially due to the collaboration with the Axis Powers during World War II, the Soviet government collectively punished ten ethnic minorities, among them the Crimean Tatars. Punishment included deportation to distant regions of Central Asia and Siberia. Soviet accounts of the late 1940s indict the Crimean Tatars as an ethnicity of traitors. Although the Crimean Tatars denied that they had committed treason, this idea was widely accepted during the Soviet period and persists in the Russian scholarly and popular literature.

On 10 May 1944, Lavrentiy Beria recommended to Stalin that the Crimean Tatars should be deported away from the border regions due to their "traitorous actions". Stalin subsequently issued GKO Order No. 5859ss, which envisaged the resettlement of the Crimean Tatars. Buckley, Ruble & Hoffman (2008), p. 231 The deportation lasted only three days, 18–20 May 1944, during which NKVD agents went house to house collecting Crimean Tatars at gunpoint and forcing them to enter sealed-off cattle trains that would transfer them almost to remote locations in the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic. The Crimean Tatars were allowed to carry up to 500 kg of their property per family. The only ones who could avoid this fate were Crimean Tatar women who were married to men of non-punished ethnic groups. The exiled Crimean Tatars travelled in overcrowded wagons for several weeks and lacked food and water. It is estimated that at least 228,392 people were deported from Crimea, of which at least 191,044 were Crimean Tatars in 47,000 families. Since 7,889 people perished in the long transit in sealed-off railcars, the NKVD registered the 183,155 living Crimean Tatars who arrived at their destinations in Central Asia. The majority of the deportees were rounded up from the Crimean countryside. Only 18,983 of the exiles were from Crimean cities.

On 4 July 1944, the NKVD officially informed Stalin that the resettlement was complete. However, not long after that report, the NKVD found out that one of its units had forgotten to deport people from the Arabat Spit. Instead of preparing an additional transfer in trains, on 20 July the NKVD boarded hundreds of Crimean Tatars onto an old boat, took it to the middle of the

Officially due to the collaboration with the Axis Powers during World War II, the Soviet government collectively punished ten ethnic minorities, among them the Crimean Tatars. Punishment included deportation to distant regions of Central Asia and Siberia. Soviet accounts of the late 1940s indict the Crimean Tatars as an ethnicity of traitors. Although the Crimean Tatars denied that they had committed treason, this idea was widely accepted during the Soviet period and persists in the Russian scholarly and popular literature.

On 10 May 1944, Lavrentiy Beria recommended to Stalin that the Crimean Tatars should be deported away from the border regions due to their "traitorous actions". Stalin subsequently issued GKO Order No. 5859ss, which envisaged the resettlement of the Crimean Tatars. Buckley, Ruble & Hoffman (2008), p. 231 The deportation lasted only three days, 18–20 May 1944, during which NKVD agents went house to house collecting Crimean Tatars at gunpoint and forcing them to enter sealed-off cattle trains that would transfer them almost to remote locations in the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic. The Crimean Tatars were allowed to carry up to 500 kg of their property per family. The only ones who could avoid this fate were Crimean Tatar women who were married to men of non-punished ethnic groups. The exiled Crimean Tatars travelled in overcrowded wagons for several weeks and lacked food and water. It is estimated that at least 228,392 people were deported from Crimea, of which at least 191,044 were Crimean Tatars in 47,000 families. Since 7,889 people perished in the long transit in sealed-off railcars, the NKVD registered the 183,155 living Crimean Tatars who arrived at their destinations in Central Asia. The majority of the deportees were rounded up from the Crimean countryside. Only 18,983 of the exiles were from Crimean cities.

On 4 July 1944, the NKVD officially informed Stalin that the resettlement was complete. However, not long after that report, the NKVD found out that one of its units had forgotten to deport people from the Arabat Spit. Instead of preparing an additional transfer in trains, on 20 July the NKVD boarded hundreds of Crimean Tatars onto an old boat, took it to the middle of the  Officially, Crimean Tatars were eliminated from Crimea. The deportation encompassed every person considered by the government to be Crimean Tatar, including children, women, and the elderly, and even those who had been members of the Communist Party or the Red Army. As such, they were legally designated as special settlers, which meant that they were officially second-class citizens, prohibited from leaving the perimeter of their assigned area, attending prestigious universities, and had to regularly appear before the commandant's office.

During this mass eviction, the Soviet authorities confiscated around 80,000 houses, 500,000 cattle, 360,000 acres of land, and 40,000 tons of agricultural provisions. Besides 191,000 deported Crimean Tatars, the Soviet authorities also evicted 9,620 Armenians, 12,420 Bulgarians, and 15,040 Greeks from the peninsula. All were collectively branded as traitors and became second-class citizens for decades in the USSR. Among the deported, there were also 283 persons of other ethnicities: Italians, Romanians, Karaims, Kurds, Czechs, Hungarians, and Croats. During 1947 and 1948, a further 2,012 veteran returnees were deported from Crimea by the local MVD.

In total, 151,136 Crimean Tatars were deported to the Uzbek SSR; 8,597 to the Mari Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic; and 4,286 to the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic; and the remaining 29,846 were sent to various remote regions of the Russian SFSR. When the Crimean Tatars arrived at their destination in the Uzbek SSR, they were met with hostility by Uzbek locals who threw stones at them, even their children, because they heard that the Crimean Tatars were "traitors" and "fascist collaborators." The Uzbeks objected to becoming the "dumping ground for treasonous nations." In the coming years, several assaults against the Crimean Tatars population were registered, some of which were fatal.

Officially, Crimean Tatars were eliminated from Crimea. The deportation encompassed every person considered by the government to be Crimean Tatar, including children, women, and the elderly, and even those who had been members of the Communist Party or the Red Army. As such, they were legally designated as special settlers, which meant that they were officially second-class citizens, prohibited from leaving the perimeter of their assigned area, attending prestigious universities, and had to regularly appear before the commandant's office.

During this mass eviction, the Soviet authorities confiscated around 80,000 houses, 500,000 cattle, 360,000 acres of land, and 40,000 tons of agricultural provisions. Besides 191,000 deported Crimean Tatars, the Soviet authorities also evicted 9,620 Armenians, 12,420 Bulgarians, and 15,040 Greeks from the peninsula. All were collectively branded as traitors and became second-class citizens for decades in the USSR. Among the deported, there were also 283 persons of other ethnicities: Italians, Romanians, Karaims, Kurds, Czechs, Hungarians, and Croats. During 1947 and 1948, a further 2,012 veteran returnees were deported from Crimea by the local MVD.

In total, 151,136 Crimean Tatars were deported to the Uzbek SSR; 8,597 to the Mari Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic; and 4,286 to the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic; and the remaining 29,846 were sent to various remote regions of the Russian SFSR. When the Crimean Tatars arrived at their destination in the Uzbek SSR, they were met with hostility by Uzbek locals who threw stones at them, even their children, because they heard that the Crimean Tatars were "traitors" and "fascist collaborators." The Uzbeks objected to becoming the "dumping ground for treasonous nations." In the coming years, several assaults against the Crimean Tatars population were registered, some of which were fatal.

The mass Crimean deportations were organized by Lavrentiy Beria, the chief of the Soviet secret police, the NKVD, and his subordinates

The mass Crimean deportations were organized by Lavrentiy Beria, the chief of the Soviet secret police, the NKVD, and his subordinates

The UN reported that of the over 10,000 people left Crimea after the annexation in 2014, most were Crimean Tatars, which caused a further decline of their fragile community. Crimean Tatars stated several reasons for their departure, among them insecurity, fear, and intimidation from the new Russian authorities. In its 2015 report, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights warned that various human rights violations were recorded in Crimea, including the prevention of Crimean Tatars from marking the 71st anniversary of their deportation.

The UN reported that of the over 10,000 people left Crimea after the annexation in 2014, most were Crimean Tatars, which caused a further decline of their fragile community. Crimean Tatars stated several reasons for their departure, among them insecurity, fear, and intimidation from the new Russian authorities. In its 2015 report, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights warned that various human rights violations were recorded in Crimea, including the prevention of Crimean Tatars from marking the 71st anniversary of their deportation.

Despite the thousands of Crimean Tatars in the Red Army when it attacked Berlin, the Crimean Tatars continued to be seen and treated as a fifth column for decades. Some historians explain this as part of Stalin's plan to take complete control of Crimea. The Soviet sought access to the Dardanelles and control of territory in Turkey, where the Crimean Tatars had ethnic kin. By painting the Crimean Tatars as traitors, this taint could be extended to their kin. Scholar

Despite the thousands of Crimean Tatars in the Red Army when it attacked Berlin, the Crimean Tatars continued to be seen and treated as a fifth column for decades. Some historians explain this as part of Stalin's plan to take complete control of Crimea. The Soviet sought access to the Dardanelles and control of territory in Turkey, where the Crimean Tatars had ethnic kin. By painting the Crimean Tatars as traitors, this taint could be extended to their kin. Scholar

In 2008, Lily Hyde, a British journalist living in Ukraine, published a novel titled ''Dreamland'' that revolves around a Crimean Tatar family return to their homeland in the 1990s. The story is told from the perspective of a 12-year-old girl who moves from Uzbekistan to a demolished village with her parents, brother, and grandfather. Her grandfather tells her stories about the heroes and victims among the Crimean Tatars.

The 2013 Ukrainian Crimean Tatar-language film ''

In 2008, Lily Hyde, a British journalist living in Ukraine, published a novel titled ''Dreamland'' that revolves around a Crimean Tatar family return to their homeland in the 1990s. The story is told from the perspective of a 12-year-old girl who moves from Uzbekistan to a demolished village with her parents, brother, and grandfather. Her grandfather tells her stories about the heroes and victims among the Crimean Tatars.

The 2013 Ukrainian Crimean Tatar-language film ''

Cyrillic

, bg, кирилица , mk, кирилица , russian: кириллица , sr, ћирилица, uk, кирилиця

, fam1 = Egyptian hieroglyphs

, fam2 = Proto-Sinaitic

, fam3 = Phoenician

, fam4 = G ...

: Къырымтатар халкъынынъ сюргюнлиги) or the Sürgünlik ('exile') was the ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

and cultural genocide of at least 191,044 Crimean Tatars carried out by the Soviet authorities from 18 to 20 May 1944, which was supervised by Lavrentiy Beria, head of Soviet state security and the secret police, and which was ordered by the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. Within those three days, the NKVD used cattle trains to deport mostly women, children, and the elderly, even Communist Party members and Red Army members, to mostly the Uzbek SSR, several thousand kilometres away. They were one of the several ethnicities who were subjected to Stalin's policy of population transfer in the Soviet Union

From 1930 to 1952, the government of the Soviet Union, on the orders of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin under the direction of the NKVD official Lavrentiy Beria, forcibly transferred populations of various groups. These actions may be classified ...

.

The deportation was officially presented as collective punishment for the claimed collaboration of some Crimean Tatars with Nazi Germany, but modern experts say that the deportation was part of the Soviet plan to gain access to the Dardanelles and acquire territory in Turkey, where the Tatars had Turkic ethnic kin, or to remove minorities from the Soviet Union's border regions.

Nearly 8,000 Crimean Tatars died during the deportation, and tens of thousands perished subsequently due to the harsh exile conditions. The Crimean Tatar deportation resulted in the abandonment of 80,000 households and 360,000 acres of land. An intense campaign of detatarization followed to try to erase the remaining traces of Crimean Tatar existence. In 1956, the new Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev condemned Stalin's policies, including the deportation of various ethnic groups, but did not lift the directive forbidding the return of the Crimean Tatars despite allowing most other deported peoples to return. The Crimean Tatars remained in Central Asia for several more decades until the perestroika

''Perestroika'' (; russian: links=no, перестройка, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg) was a political movement for reform within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s widely associated wit ...

era in the late 1980s, when 260,000 Crimean Tatars returned to Crimea. Their exile had lasted 45 years. The ban on their return was officially declared null and void when the Supreme Council of Crimea declared on 14 November 1989 that the deportations had been a crime.

By 2004, the number of Crimean Tatars who had returned to Crimea had increased their share of the peninsula's population to 12 percent. The Soviet authorities had neither assisted their return nor compensated them for the land they lost. Neither Ukraine nor the Russian Federation provided reparations

Reparation(s) may refer to:

Christianity

* Restitution (theology), the Christian doctrine calling for reparation

* Acts of reparation, prayers for repairing the damages of sin

History

*War reparations

**World War I reparations, made from G ...

, compensated those deported for lost property, or filed legal proceedings against the perpetrators of the forced resettlement. The deportation and subsequent assimilation efforts in Asia represent a crucial period in the history of the Crimean Tatars. Between 2015 and 2019, the deportation was formally recognized as genocide by Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia and Canada.

Background

Russian expansion

The borders of Russia changed through military conquests and by ideological and political unions in the course of over five centuries (1533–present).

Russian Tsardom and Empire

The name ''Russia'' for the Grand Duchy of Moscow began to ap ...

. By the 14th century, most of the Turkic-speaking population of Crimea had adopted Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

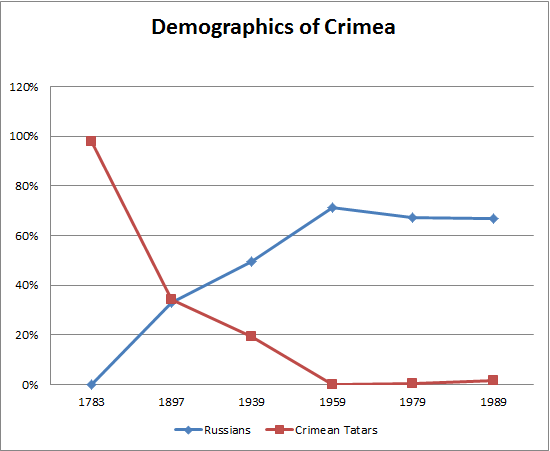

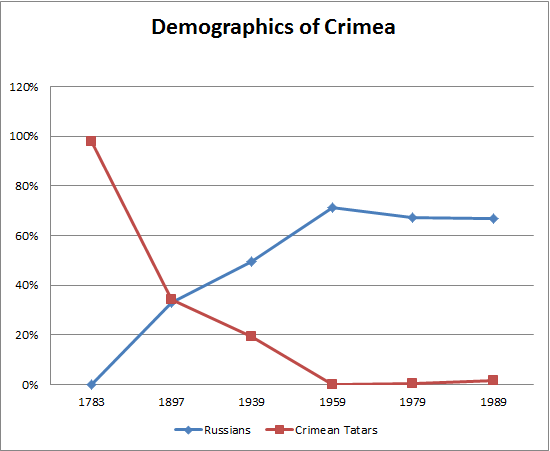

, following the conversion of Ozbeg Khan of the Golden Horde. It was the longest surviving state of the Golden Horde. They often engaged in conflicts with Moscow—from 1468 until the 17th century, Crimean Tatars were averse to the newly-established Russian rule. Thus, Crimean Tatars began leaving Crimea in several waves of emigration. Between 1784 and 1790, out of a total population of about a million, around 300,000 Crimean Tatars left for the Ottoman Empire.

The Crimean War triggered another mass exodus

Exodus or the Exodus may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Exodus, second book of the Hebrew Torah and the Christian Bible

* The Exodus, the biblical story of the migration of the ancient Israelites from Egypt into Canaan

Historical events

* Ex ...

of Crimean Tatars. Between 1855 and 1866 at least 500,000 Muslims, and possibly up to 900,000, left the Russian Empire and emigrated to the Ottoman Empire. Out of that number, at least one third were from Crimea, while the rest were from the Caucasus. These emigrants comprised 15–23 percent of the total population of Crimea. The Russian Empire used that fact as the ideological foundation to further Russify " New Russia". Eventually, the Crimean Tatars became a minority in Crimea; in 1783, they comprised 98 per cent of the population, but by 1897, this was down to 34.1 per cent. While Crimean Tatars were emigrating, the Russian government encouraged Russification

Russification (russian: русификация, rusifikatsiya), or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether involuntarily or voluntarily, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian cultur ...

of the peninsula, populating it with Russians, Ukrainians, and other Slavic ethnic groups; this Russification continued during the Soviet era. Vardys (1971), p. 101

After the 1917 October Revolution, Crimea received autonomous status inside the USSR on 18 October 1921, but collectivization in the 1920s led to severe famine from which up to 100,000 Crimeans perished when their crops were transported to "more important" regions of the Soviet Union. By one estimate, three-quarters of the famine victims were Crimean Tatars. Their status deteriorated further after Joseph Stalin became the Soviet leader and implemented repressions that led to the deaths of at least 5.2 million Soviet citizens between 1927 and 1938.

After the 1917 October Revolution, Crimea received autonomous status inside the USSR on 18 October 1921, but collectivization in the 1920s led to severe famine from which up to 100,000 Crimeans perished when their crops were transported to "more important" regions of the Soviet Union. By one estimate, three-quarters of the famine victims were Crimean Tatars. Their status deteriorated further after Joseph Stalin became the Soviet leader and implemented repressions that led to the deaths of at least 5.2 million Soviet citizens between 1927 and 1938.

World War II

In 1940, the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic had approximately 1,126,800 inhabitants, of which 218,000 people, or 19.4 percent of the population, were Crimean Tatars. In 1941, Nazi Germany invaded Eastern Europe, annexing much of the western USSR. Crimean Tatars initially viewed the Germans as liberators from Stalinism, and they had also been positively treated by the Germans in World War I. Williams (2015), p. 92 Many of the captured Crimean Tatars serving in the Red Army were sent to POW camps after Romanians and Nazis came to occupy the bulk of Crimea. Though Nazis initially called for murder of all "Asiatic inferiors" and paraded around Crimean Tatar POW's labeled as "Mongol sub-humanity", they revised this policy in the face of determined resistance from the Red Army. Beginning in 1942, Germans recruited Soviet prisoners of war to form support armies. The Dobrujan Tatar nationalist Fazil Ulkusal and Lipka Tatar Edige Kirimal helped in freeing Crimean Tatars from German prisoner-of-war camps and enlisting them in the independent Crimean support legion for the '' Wehrmacht''. This legion eventually included eight battalions, although many members were of other nationalities. From November 1941, German authorities allowed Crimean Tatars to establish Muslim Committees in various towns as a symbolic recognition of some local government authority, though they were not given any political power. Many Crimean Tatar communists strongly opposed the occupation and assisted the resistance movement to provide valuable strategic and political information. Other Crimean Tatars also fought on the side of the Soviet partisans, like the Tarhanov movement of 250 Crimean Tatars which fought throughout 1942 until its destruction. Six Crimean Tatars were even named the Heroes of the Soviet Union, and thousands more were awarded high honors in the Red Army. Up to 130,000 people died during the Axis occupation of Crimea. The Nazis implemented a brutal repression, destroying more than 70 villages that were together home to about 25 per cent of the Crimean Tatar population. Thousands of Crimean Tatars were forcibly transferred to work as ''Ostarbeiter

:

' (, "Eastern worker") was a Nazi German designation for foreign slave workers gathered from occupied Central and Eastern Europe to perform forced labor in Germany during World War II. The Germans started deporting civilians at the beginning ...

'' in German factories under the supervision of the Gestapo in what were described as "vast slave workshops", resulting in loss of all Crimean Tatar support. In April 1944 the Red Army managed to repel the Axis forces from the peninsula in the Crimean Offensive.

A majority of the hiwis (helpers), their families and all those associated with the Muslim Committees were evacuated to Germany and Hungary or Dobruja by the Wehrmacht and Romanian Army where they joined the Eastern Turkic division. Thus, the majority of the collaborators had been evacuated from Crimea by the retreating Wehrmacht. Many Soviet officials had also recognized this and rejected claims that the Crimean Tatars had betrayed the Soviet Union ''en masse''. The presence of Muslim Committees organized from Berlin by various Turkic foreigners appeared a cause for concern in the eyes of the Soviet government, already wary of Turkey at the time. Williams (2001), pp. 382–384

Falsification of information in media

Soviet publications blatantly falsified information about Crimean Tatars in the Red Army, going so far as to describe Crimean Tatar Hero of the Soviet UnionUzeir Abduramanov

Uzeir Abduramanovich Abduramanov ( crh, Üzeir Abduraman oğlu Abduramanov, russian: Узеир Абдураманович Абдураманов; 25 March 1916 – 19 January 1991) was a sapper in the Red Army during the Great Patriotic War. ...

as Azeri

Azerbaijanis (; az, Azərbaycanlılar, ), Azeris ( az, Azərilər, ), or Azerbaijani Turks ( az, Azərbaycan Türkləri, ) are a Turkic peoples, Turkic people living mainly in Azerbaijan (Iran), northwestern Iran and the Azerbaijan, Republi ...

, not Crimean Tatar, on the cover of a 1944 issue of ''Ogonyok'' magazine - even though his family had been deported for being Crimean Tatar just a few months earlier. The book ''In the Mountains of Tavria'' falsely claimed that volunteer partisan scout Bekir Osmanov

Bekir Osmanov (; 22 March 1911 26 May 1983) was a Crimean Tatar civil rights activist, agronomist, and partisan.

Early life

Osmanov was born in Crimea on 22 March 1911 in Buyuk Ozenbash village. His father, who was a teacher at a local madras ...

was a German spy and shot, although the central committee later acknowledged that he never served the Germans and survived the war, ordering later editions to have corrections after still-living Osmanov and his family noticed the obvious falsehood. Amet-khan Sultan

Amet-khan Sultan (Crimean Tatar language, Crimean Tatar: Amet-Han Sultan, Амет-Хан Султан, احمدخان سلطان; Russian language, Russian: Амет-Хан Султан; 20 October 1920 – 1 February 1971) was a highly decorated ...

, born to a Crimean Tatar mother and Lak father in Crimea, where he was born and raised, was often described as a Dagestani in post-deportation media, even though he always considered himself a Crimean Tatar.

Deportation

Officially due to the collaboration with the Axis Powers during World War II, the Soviet government collectively punished ten ethnic minorities, among them the Crimean Tatars. Punishment included deportation to distant regions of Central Asia and Siberia. Soviet accounts of the late 1940s indict the Crimean Tatars as an ethnicity of traitors. Although the Crimean Tatars denied that they had committed treason, this idea was widely accepted during the Soviet period and persists in the Russian scholarly and popular literature.

On 10 May 1944, Lavrentiy Beria recommended to Stalin that the Crimean Tatars should be deported away from the border regions due to their "traitorous actions". Stalin subsequently issued GKO Order No. 5859ss, which envisaged the resettlement of the Crimean Tatars. Buckley, Ruble & Hoffman (2008), p. 231 The deportation lasted only three days, 18–20 May 1944, during which NKVD agents went house to house collecting Crimean Tatars at gunpoint and forcing them to enter sealed-off cattle trains that would transfer them almost to remote locations in the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic. The Crimean Tatars were allowed to carry up to 500 kg of their property per family. The only ones who could avoid this fate were Crimean Tatar women who were married to men of non-punished ethnic groups. The exiled Crimean Tatars travelled in overcrowded wagons for several weeks and lacked food and water. It is estimated that at least 228,392 people were deported from Crimea, of which at least 191,044 were Crimean Tatars in 47,000 families. Since 7,889 people perished in the long transit in sealed-off railcars, the NKVD registered the 183,155 living Crimean Tatars who arrived at their destinations in Central Asia. The majority of the deportees were rounded up from the Crimean countryside. Only 18,983 of the exiles were from Crimean cities.

On 4 July 1944, the NKVD officially informed Stalin that the resettlement was complete. However, not long after that report, the NKVD found out that one of its units had forgotten to deport people from the Arabat Spit. Instead of preparing an additional transfer in trains, on 20 July the NKVD boarded hundreds of Crimean Tatars onto an old boat, took it to the middle of the

Officially due to the collaboration with the Axis Powers during World War II, the Soviet government collectively punished ten ethnic minorities, among them the Crimean Tatars. Punishment included deportation to distant regions of Central Asia and Siberia. Soviet accounts of the late 1940s indict the Crimean Tatars as an ethnicity of traitors. Although the Crimean Tatars denied that they had committed treason, this idea was widely accepted during the Soviet period and persists in the Russian scholarly and popular literature.

On 10 May 1944, Lavrentiy Beria recommended to Stalin that the Crimean Tatars should be deported away from the border regions due to their "traitorous actions". Stalin subsequently issued GKO Order No. 5859ss, which envisaged the resettlement of the Crimean Tatars. Buckley, Ruble & Hoffman (2008), p. 231 The deportation lasted only three days, 18–20 May 1944, during which NKVD agents went house to house collecting Crimean Tatars at gunpoint and forcing them to enter sealed-off cattle trains that would transfer them almost to remote locations in the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic. The Crimean Tatars were allowed to carry up to 500 kg of their property per family. The only ones who could avoid this fate were Crimean Tatar women who were married to men of non-punished ethnic groups. The exiled Crimean Tatars travelled in overcrowded wagons for several weeks and lacked food and water. It is estimated that at least 228,392 people were deported from Crimea, of which at least 191,044 were Crimean Tatars in 47,000 families. Since 7,889 people perished in the long transit in sealed-off railcars, the NKVD registered the 183,155 living Crimean Tatars who arrived at their destinations in Central Asia. The majority of the deportees were rounded up from the Crimean countryside. Only 18,983 of the exiles were from Crimean cities.

On 4 July 1944, the NKVD officially informed Stalin that the resettlement was complete. However, not long after that report, the NKVD found out that one of its units had forgotten to deport people from the Arabat Spit. Instead of preparing an additional transfer in trains, on 20 July the NKVD boarded hundreds of Crimean Tatars onto an old boat, took it to the middle of the Azov Sea

The Sea of Azov ( Crimean Tatar: ''Azaq deñizi''; russian: Азовское море, Azovskoye more; uk, Азовське море, Azovs'ke more) is a sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Kerch, ...

, and sank the ship. Those who did not drown were finished off by machine-guns

A machine gun is a automatic firearm, fully automatic, rifling, rifled action (firearms)#Autoloading operation, autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as Automatic shotgun, a ...

.

The mass Crimean deportations were organized by Lavrentiy Beria, the chief of the Soviet secret police, the NKVD, and his subordinates

The mass Crimean deportations were organized by Lavrentiy Beria, the chief of the Soviet secret police, the NKVD, and his subordinates Bogdan Kobulov

Bogdan Zakharovich Kobulov (russian: Богда́н Заха́рович Кобу́лов; 1 March 1904 – 23 December 1953) served as a senior member of the Soviet Union , Soviet security- and police-apparatus during the rule of Joseph Stalin. A ...

, Ivan Serov, B. P. Obruchnikov, M.G. Svinelupov, and A. N. Apolonov. The field operations were conducted by G. P. Dobrynin, the Deputy Head of the Gulag system; G. A. Bezhanov, the Colonel of State Security; I. I. Piiashev, Major General; S. A. Klepov, Commissar of State Security; I. S. Sheredega, Lt. General; B. I. Tekayev, Lt. Colonel of State Security; and two local leaders, P. M. Fokin, head of the Crimea NKGB, and V. T. Sergjenko, Lt. General. In order to execute this deportation, the NKVD secured 5,000 armed agents and the NKGB allocated a further 20,000 armed men, together with a few thousand regular soldiers. Two of Stalin's directives from May 1944 reveal that many parts of the Soviet government, from financing to transit, were involved in executing the operation.

On 14 July 1944 the GKO authorized the immigration of 51,000 people, mostly Russians, to 17,000 empty collective farms

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

on Crimea. On 30 June 1945, the Crimean ASSR was abolished.

Soviet propaganda

Propaganda in the Soviet Union was the practice of state-directed communication to promote class conflict, internationalism, the goals of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and the party itself.

The main Soviet censorship body, Glavlit, ...

sought to hide the population transfer by claiming that the Crimean Tatars had "voluntarily resettle to Central Asia". In essence, though, according to historian Paul Robert Magocsi, Crimea was "ethnically cleansed

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

." After this act, the term ''Crimean Tatar'' was banished from the Russian-Soviet lexicon, and all Crimean Tatar toponyms

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of ''toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage and types. Toponym is the general term for a proper name of ...

(names of towns, villages, and mountains) in Crimea were changed to Russian names on all maps as part of a wide detatarization campaign. Muslim graveyards and religious objects in Crimea were demolished or converted into secular places. During Stalin's rule, nobody was allowed to mention that this ethnicity even existed in the USSR. This went so far that many individuals were even forbidden to declare themselves as Crimean Tatars during the Soviet censuses of 1959, 1970

Events

January

* January 1 – Unix time epoch reached at 00:00:00 UTC.

* January 5 – The 7.1 Tonghai earthquake shakes Tonghai County, Yunnan province, China, with a maximum Mercalli intensity scale, Mercalli intensity of X (''Extrem ...

, and 1979. They could only declare themselves as Tatars. This ban was lifted during the Soviet census of 1989.

Aftermath

Mortality and death toll

The first deportees started arriving in the Uzbek SSR on 29 May 1944 and most had arrived by 8 June 1944. The consequent mortality rate remains disputed; the NKVD kept incomplete records of the death rate among the resettled ethnicities living in exile. Like the other deported peoples, the Crimean Tatars were placed under the regime of special settlements. Many of those deported performed forced labor: their tasks included working in coal mines and construction battalions, under the supervision of the NKVD. Deserters were executed. Special settlers routinely worked eleven to twelve hours a day, seven days a week. Despite this difficult physical labor, the Crimean Tatars were given only around to of bread per day. Accommodations were insufficient; some were forced to live in mud huts where "there were no doors or windows, nothing, just reeds" on the floor to sleep on. The sole transport to these remote areas andlabour colonies

A labor camp (or labour camp, see spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons (especi ...

was equally as strenuous. Theoretically, the NKVD loaded 50 people into each railroad car, together with their property. One witness claimed that 133 people were in her wagon. They had only one hole in the floor of the wagon which was used as a toilet. Some pregnant women were forced to give birth inside these sealed-off railroad cars. The conditions in the overcrowded train wagons were exacerbated by a lack of hygiene, leading to cases of typhus. Since the trains only stopped to open the doors at rare occasions during the trip, the sick inevitably contaminated others in the wagons. It was only when they arrived at their destination in the Uzbek SSR that the Crimean Tatars were released from the sealed-off railroad cars. Still, some were redirected to other destinations in Central Asia and had to continue their journey. Some witnesses claimed that they travelled for 24 consecutive days. During this whole time, they were given very little food or water while trapped inside. There was no fresh air since the doors and windows were bolted shut. In Kazakh SSR, the transport guards unlocked the door only to toss out the corpses along the railroad. The Crimean Tatars thus called these railcars "crematoria

Cremation is a method of final disposition of a dead body through burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India and Nepal, cremation on an open-air pyre i ...

on wheels." The records show that at least 7,889 Crimean Tatars died during this long journey, amounting to about 4 per cent of their entire ethnicity.

The high mortality rate continued for several years in exile due to malnutrition, labor exploitation

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of e ...

, diseases, lack of medical care, and exposure to the harsh desert climate of Uzbekistan. The exiles were frequently assigned to the heaviest construction sites. The Uzbek medical facilities filled with Crimean Tatars who were susceptible to the local Asian diseases not found on the Crimean peninsula where the water was purer, including yellow fever, dystrophy, malaria, and intestinal illness. The death toll was the highest during the first five years. In 1949 the Soviet authorities counted the population of the deported ethnic groups who lived in special settlements. According to their records, there were 44,887 excess death

In epidemiology, mortality displacement is the occurrence of deaths at an earlier time than they would have otherwise occurred, meaning the deaths are ''displaced'' from the future into the present. The displacement may be described as the resul ...

s in these five years, 19.6 per cent of that total group. Buckley, Ruble & Hofmann (2008), p. 207 Other sources give a figure of 44,125 deaths during that time, while a third source, using alternative NKVD archives, gives a figure of 32,107 deaths. These reports included all the people resettled from Crimea (including Armenians, Bulgarians, and Greeks), but the Crimean Tatars formed a majority in this group. It took five years until the number of births among the deported people started to surpass the number of deaths. Soviet archives reveal that between May 1944 and January 1945 a total of 13,592 Crimean Tatars perished in exile, about 7 per cent of their entire population. Almost half of all deaths (6,096) were of children under the age of 16; another 4,525 were adult women and 2,562 were adult men. During 1945, a further 13,183 people died. Thus, by the end of December 1945, at least 27,000 Crimean Tatars had already died in exile. One Crimean Tatar woman living near Tashkent recalled the events from 1944:

Estimates produced by Crimean Tatars indicate mortality figures that were far higher and amounted to 46% of their population living in exile. In 1968, when Leonid Brezhnev presided over the USSR, Crimean Tatar activists were persecuted for using that high mortality figure under the guise that it was a "slander to the USSR." In order to show that Crimean Tatars were exaggerating, the KGB published figures showing that "only" 22 per cent of that ethnic group died. The Karachay demographer Dalchat Ediev estimates that 34,300 Crimean Tatars died due to the deportation, representing an 18 per cent mortality rate. Hannibal Travis estimates that overall 40,000–80,000 Crimean Tatars died in exile. Professor Michael Rywkin gives a figure of at least 42,000 Crimean Tatars who died between 1944 and 1951, including 7,900 who died during the transit Professor Brian Glyn Williams

Brian Glyn Williams is a professor of Islamic History at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth who worked for the CIA. As an undergraduate, he attended Stetson University, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts in 1988. He received his PhD in Midd ...

gives a figure of between 40,000 and 44,000 deaths as a consequence of this deportation. The Crimean State Committee estimated that 45,000 Crimean Tatars died between 1944 and 1948. The official NKVD report estimated that 27 per cent of that ethnicity died.

Various estimates of the mortality rates of the Crimean Tatars:

Rehabilitation

Stalin's government denied the Crimean Tatars the right to education or publication in their native language. Despite the prohibition, and although they had to study in Russian or Uzbek, they maintained their cultural identity. In 1956 the new Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, held a speech in which he condemned Stalin's policies, including the mass deportations of various ethnicities. Still, even though many peoples were allowed to return to their homes, three groups were forced to stay in exile: theSoviet Germans

The German minority population in Russia, Ukraine, and the Soviet Union stemmed from several sources and arrived in several waves. Since the second half of the 19th century, as a consequence of the Russification policies and compulsory military ...

, the Meskhetian Turks

Meskhetian Turks, also referred to as Turkish Meskhetians, Ahiska Turks, and Turkish Ahiskans, ( ka, მესხეთის თურქები ''Meskhetis turk'ebi'') are an ethnic subgroup of Turks formerly inhabiting the Meskheti regio ...

, and the Crimean Tatars. In 1954, Khrushchev allowed Crimea to be included in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic since Crimea is linked by land to Ukraine and not with the Russian SFSR. On 28 April 1956, the directive "On Removing Restrictions on the Special Settlement of the Crimean Tatars... Relocated during the Great Patriotic War" was issued, ordering a de-registration of the deportees and their release from administrative supervision. However, various other restrictions were still kept and the Crimean Tatars were not allowed to return to Crimea. Moreover, that same year the Ukrainian Council of Ministers banned the exiled Crimean Tatars, Greeks, Germans, Armenians and Bulgarians from relocating even to the Kherson

Kherson (, ) is a port city of Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers appr ...

, Zaporizhia, Mykolaiv and Odessa Oblasts in the Ukrainian SSR. The Crimean Tatars did not get any compensation for their lost property.

In the 1950s, the Crimean Tatars started actively advocating for the right to return. In 1957, they collected 6,000 signatures in a petition that was sent to the Supreme Soviet

The Supreme Soviet (russian: Верховный Совет, Verkhovny Sovet, Supreme Council) was the common name for the legislative bodies (parliaments) of the Soviet socialist republics (SSR) in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) ...

that demanded their political rehabilitation and return to Crimea. In 1961 25,000 signatures were collected in a petition that was sent to the Kremlin

The Kremlin ( rus, Московский Кремль, r=Moskovskiy Kreml', p=ˈmɐˈskofskʲɪj krʲemlʲ, t=Moscow Kremlin) is a fortified complex in the center of Moscow founded by the Rurik dynasty, Rurik dynasty. It is the best known of th ...

.

Mustafa Dzhemilev, who was only six months old when his family was deported from Crimea, grew up in Uzbekistan and became an activist for the right of the Crimean Tatars to return. In 1966 he was arrested for the first time and spent a total of 17 years in prison during the Soviet era. This earned him the nickname of "Crimean Tatar Mandela." In 1984 he was sentenced for the sixth time for "anti-Soviet activity" but was given moral support by the Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov, who had observed Dzhemilev's fourth trial in 1976. When older dissidents were arrested, a new, younger generation emerged that would replace them.

On 21 July 1967, representatives of the Crimean Tatars, led by the dissident Ayshe Seitmuratova Ayshe is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*John Ayshe, English politician

* Thomas Ayshe (died 1587), English politician

See also

*Ashe (name) Ashe is a surname in Ireland. Most are of Norman origin and were originally known as ...

, gained permission to meet with high-ranking Soviet officials in Moscow, including Yuri Andropov. During the meeting, the Crimean Tatars demanded a correction of all the injustices of the USSR against their people. In September 1967, the Supreme Soviet

The Supreme Soviet (russian: Верховный Совет, Verkhovny Sovet, Supreme Council) was the common name for the legislative bodies (parliaments) of the Soviet socialist republics (SSR) in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) ...

issued a decree that acknowledged the charge of treason against the entire nation was "unreasonable" but that did not allow Crimean Tatars the same full rehabilitation encompassing the right of return that other deported peoples were given. The carefully worded decree referred to them not as "Crimean Tatars" but as "citizens of Tatar nationality who having formerly lived in Crimea ��have taken root in the Uzbek SSR", thereby minimizing Crimean Tatar existence and downplaying their desire for the right of return in addition to creating a premise for claims of the issue being "settled". Individuals united and formed groups that went back to Crimea in 1968 on their own, without state permission, but the Soviet authorities deported 6,000 of them once again. Williams (2001), p. 425 The most notable example of such resistance was a Crimean Tatar activist, Musa Mamut

Musa Mamut (Russian and Crimean Tatar Cyrillic: Муса Мамут; 20 February 1931 – 28 June 1978) was a deported Crimean Tatar who immolated himself in Crimea as a sign of protest against the enforced exile of indigenous Crimean Tatars. His ...

, who was deported when he was 12 and who returned to Crimea because he wanted to see his home again. When the police informed him that he would be evicted, he set himself on fire. Nevertheless, 577 families managed to obtain state permission to reside in Crimea.

In 1968 unrest erupted among the Crimean Tatar people in the Uzbek city of Chirchiq. In October 1973, the Jewish poet and professor Ilya Gabay committed suicide by jumping off a building in Moscow. He was one of the significant Jewish dissidents in the USSR who fought for the rights of the oppressed peoples, especially Crimean Tatars. Gabay had been arrested and sent to a labour camp but still insisted on his cause because he was convinced that the treatment of the Crimean Tatars by the USSR amounted to genocide. In 1973, Dzhemilev was also arrested for his advocacy for Crimean Tatar right to return to Crimea.

Repatriation

Despitede-Stalinization

De-Stalinization (russian: десталинизация, translit=destalinizatsiya) comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and the thaw brought about by ascension ...

, the situation didn't change until Gorbachev's perestroika

''Perestroika'' (; russian: links=no, перестройка, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg) was a political movement for reform within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s widely associated wit ...

in the late 1980s. A 1987 Tatar protest near the Kremlin

The Kremlin ( rus, Московский Кремль, r=Moskovskiy Kreml', p=ˈmɐˈskofskʲɪj krʲemlʲ, t=Moscow Kremlin) is a fortified complex in the center of Moscow founded by the Rurik dynasty, Rurik dynasty. It is the best known of th ...

prompted Gorbachev to form the Gromyko Commission which found against Tatar claims, but a second commission recommended "renewal of autonomy" for Crimean Tatars. In 1989 the ban on the return of deported ethnicities was declared officially null and void and the Supreme Council of Crimea further declared the deportations criminal, paving the way for the Crimean Tatars to return. Dzhemilev returned to Crimea that year, with at least 166,000 other Tatars doing the same by January 1992. The 1991 Russian law '' On the Rehabilitation of Repressed Peoples'' rehabilitated all Soviet repressed ethnicities and abolished all previous Russian laws relating to the deportations, calling for the "restoration and return of the cultural and spiritual values and archives which represent the heritage of the repressed people."

By 2004 the Crimean Tatars formed 12 per cent of the population of Crimea. The return was fraught: with Russian nationalist

Russian nationalism is a form of nationalism that promotes Russian cultural identity and unity. Russian nationalism first rose to prominence in the early 19th century, and from its origin in the Russian Empire, to its repression during early B ...

protests in Crimea and clashes between locals and Crimean Tatars near Yalta, which needed army intervention. Local Soviet authorities were reluctant to help returnees with jobs or housing, After the dissolution of the USSR, Crimea was part of Ukraine, but Kyiv gave limited support to Crimean Tatar settlers. Some 150,000 of the returnees were granted citizenship automatically under Ukraine's Citizenship Law

Nationality law is the law of a sovereign state, and of each of its jurisdictions, that defines the legal manner in which a national identity is acquired and how it may be lost. In international law, the legal means to acquire nationality and for ...

of 1991, but 100,000 who returned after Ukraine declared independence faced several obstacles including a costly bureaucratic process.

Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation

In March 2014, theannexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation

In February and March 2014, Russia invaded and subsequently annexed the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine. This event took place in the aftermath of the Revolution of Dignity and is part of the wider Russo-Ukrainian War.

The events in Kyiv th ...

unfolded, which was, in turn, declared illegal by the United Nations General Assembly (United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/262

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/262 was adopted on 27 March 2014 by the sixty-eighth session of the United Nations General Assembly in response to the Russian annexation of Crimea and entitled "territorial integrity of Ukraine" ...

) and which led to further deterioration of the rights of the Crimean Tatars. Even though the Russian Federation issued Decree No. 268 "On the Measures for the Rehabilitation of Armenian, Bulgarian, Greek, Crimean Tatar and German Peoples and the State Support of Their Revival and Development" on 21 April 2014, in practice it has treated Crimean Tatars with far less care. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights issued a warning against the Kremlin in 2016 because it "intimidated, harassed and jailed Crimean Tatar representatives, often on dubious charges", while the representative body the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People was banned.

The UN reported that of the over 10,000 people left Crimea after the annexation in 2014, most were Crimean Tatars, which caused a further decline of their fragile community. Crimean Tatars stated several reasons for their departure, among them insecurity, fear, and intimidation from the new Russian authorities. In its 2015 report, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights warned that various human rights violations were recorded in Crimea, including the prevention of Crimean Tatars from marking the 71st anniversary of their deportation.

The UN reported that of the over 10,000 people left Crimea after the annexation in 2014, most were Crimean Tatars, which caused a further decline of their fragile community. Crimean Tatars stated several reasons for their departure, among them insecurity, fear, and intimidation from the new Russian authorities. In its 2015 report, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights warned that various human rights violations were recorded in Crimea, including the prevention of Crimean Tatars from marking the 71st anniversary of their deportation.

Modern views and legacy

Historian Edward Allworth has noted that the extent of marginalization of the Crimean Tatars was a distinct anomaly among national policy in the USSR given the party's firm commitment maintaining the status quo of not recognizing them as a distinct ethnic group in addition to assimilating and "rooting" them in exile, in sharp contrast to the rehabilitation other deported ethnic groups such as the Chechens, Ingush, Karachays, Balkars, and Kalmyks experienced in the Khrushchev era. Between 1989 and 1994, around a quarter of a million Crimean Tatars returned to Crimea from exile in Central Asia. This was seen as a symbolic victory of their efforts to return to their native land. They returned after 45 years of exile. Not one of the several ethnic groups who were deported during Stalin's era received any kind of financial compensation. Some Crimean Tatar groups and activists have called for the international community to put pressure on the Russian Federation, the successor state of the USSR, to finance rehabilitation of that ethnicity and provide financial compensation for forcible resettlement.Walter Kolarz Walter Jean Kolarz (26 April 1912 - 21 July 1962) was a British-based scholar of the communist world who wrote widely on ethnic and religious issues.

Kolarz was born in Teplitz-Schonau, Kingdom of Bohemia, Austro-Hungarian Empire. He studied at Ch ...

alleges that the deportation and the attempt of liquidation of Crimean Tatars as an ethnicity in 1944 was just the final act of the centuries-long process of Russian colonization of Crimea that started in 1783. Historian Gregory Dufaud

Gregory may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Gregory (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Gregory (surname), a surname

Places Australia

*Gregory, Queensland, a town in the Shire of ...

regards the Soviet accusations against Crimean Tatars as a convenient excuse for their forcible transfer through which Moscow secured an unrivalled access to the geostrategic southern Black Sea on one hand and eliminated hypothetical rebellious nations at the same time. Professor of Russian and Soviet history Rebecca Manley similarly concluded that the real aim of the Soviet government was to "cleanse" the border regions of "unreliable elements". Professor Brian Glyn Williams

Brian Glyn Williams is a professor of Islamic History at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth who worked for the CIA. As an undergraduate, he attended Stetson University, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts in 1988. He received his PhD in Midd ...

states that the deportations of Meskhetian Turks

Meskhetian Turks, also referred to as Turkish Meskhetians, Ahiska Turks, and Turkish Ahiskans, ( ka, მესხეთის თურქები ''Meskhetis turk'ebi'') are an ethnic subgroup of Turks formerly inhabiting the Meskheti regio ...

, despite never being close to the scene of combat and never being charged with any crime, lends the strongest credence to the fact that the deportations of Crimeans and Caucasians was due to Soviet foreign policy rather than any real "universal mass crimes".

Modern interpretations by scholars and historians sometimes classify this mass deportation of civilians as a crime against humanity, ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

, depopulation

A population decline (also sometimes called underpopulation, depopulation, or population collapse) in humans is a reduction in a human population size. Over the long term, stretching from prehistory to the present, Earth's total human population ...

, an act of Stalinist repression, or an " ethnocide", meaning a deliberate wiping out of an identity and culture of a nation. Crimean Tatars call this event ''Sürgünlik'' ("exile"). The perception of Crimean Tatars as "uncivilized" and deserving the deportation remains throughout the Russian and Ukrainian settlers in Crimea.

Genocide question and recognition

Some activists, politicians, scholars, countries, and historians go even further and consider the deportation a crime of genocide or cultural genocide.Norman Naimark

Norman M. Naimark (; born 1944, New York City) is an American historian. He is the Robert and Florence McDonnell Professor of Eastern European Studies at Stanford University, and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. He writes on modern Easte ...

writes " e Chechens and Ingush, the Crimean Tatars, and other 'punished peoples' of the wartime period were, indeed, slated for elimination, if not physically, then as self-identifying nationalities." Professor Lyman H. Legters argued that the Soviet penal system, combined with its resettlement policies, should count as genocidal since the sentences were borne most heavily specifically on certain ethnic groups, and that a relocation of these ethnic groups, whose survival depends on ties to its particular homeland, "had a genocidal effect remediable only by restoration of the group to its homeland." Soviet dissidents Ilya Gabay and Pyotr Grigorenko both classified the event as a genocide. Historian Timothy Snyder included it in a list of Soviet policies that “meet the standard of genocide." On 12 December 2015, the Ukrainian Parliament issued a resolution recognizing this event as genocide and established 18 May as the "Day of Remembrance for the victims of the Crimean Tatar genocide." The parliament of Latvia

The Saeima () is the parliament of the Republic of Latvia. It is a unicameral parliament consisting of 100 members who are elected by proportional representation, with seats allocated to political parties which gain at least 5% of the popular vo ...

recognized the event as an act of genocide on 9 May 2019. The Parliament of Lithuania

The Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublikos Seimas), or simply the Seimas (), is the unicameral parliament of Lithuania. The Seimas constitutes the legislative branch of government in Lithuania, enacting laws and amendmen ...

did the same on 6 June 2019. Canadian Parliament passed a motion on June 10, 2019, recognizing the Crimean Tatar deportation of 1944 (Sürgünlik) as a genocide perpetrated by Soviet dictator Stalin, designating May 18 to be a day of remembrance. On 26 April 1991 the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic, under its chairman Boris Yeltsin, passed the law On the Rehabilitation of Repressed Peoples with Article 2 denouncing all mass deportations as "Stalin's policy of defamation and genocide."

A minority dispute defining the event as genocide. According to Alexander Statiev, the Soviet deportations

From 1930 to 1952, the Government of the Soviet Union, government of the Soviet Union, on the orders of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin under the direction of the NKVD official Lavrentiy Beria, forced transfer, forcibly transferred populations of ...

resulted in a "genocidal death rate", but Stalin did not have the intent

''The Intent'' is a 2016 British crime thriller film directed by, written by and starring Femi Oyeniran

Femi Oyeniran is a Nigerian-British actor and director who started his career in the cult classic ''Kidulthood'', playing the role of " ...

to exterminate these peoples. He considers such deportations merely an example of Soviet assimilation of "unwanted nations." According to Amir Weiner, the Soviet regime sought to eradicate "only" their "territorial identity". Such views were criticized by Jon Chang as "gentrified racism" and historical revisionism

In historiography, historical revisionism is the reinterpretation of a historical account. It usually involves challenging the orthodox (established, accepted or traditional) views held by professional scholars about a historical event or times ...

. He noted that the deportations had been in fact based on ethnicity of victims.

In popular culture

In 2008, Lily Hyde, a British journalist living in Ukraine, published a novel titled ''Dreamland'' that revolves around a Crimean Tatar family return to their homeland in the 1990s. The story is told from the perspective of a 12-year-old girl who moves from Uzbekistan to a demolished village with her parents, brother, and grandfather. Her grandfather tells her stories about the heroes and victims among the Crimean Tatars.

The 2013 Ukrainian Crimean Tatar-language film ''

In 2008, Lily Hyde, a British journalist living in Ukraine, published a novel titled ''Dreamland'' that revolves around a Crimean Tatar family return to their homeland in the 1990s. The story is told from the perspective of a 12-year-old girl who moves from Uzbekistan to a demolished village with her parents, brother, and grandfather. Her grandfather tells her stories about the heroes and victims among the Crimean Tatars.

The 2013 Ukrainian Crimean Tatar-language film ''Haytarma

Haytarma ( crh, Qaytarma — ''«return», «homecoming»'') is a 2013 Ukrainian period drama film. It portrays Crimean Tatar flying ace and Hero of the Soviet Union Amet-khan Sultan against the background of the 1944 deportation of the Crimean ...

'' portrays the experience of Crimean Tatar flying ace and Hero of the Soviet Union Amet-khan Sultan

Amet-khan Sultan (Crimean Tatar language, Crimean Tatar: Amet-Han Sultan, Амет-Хан Султан, احمدخان سلطان; Russian language, Russian: Амет-Хан Султан; 20 October 1920 – 1 February 1971) was a highly decorated ...

during the 1944 deportations.

In 2015 Christina Paschyn released the documentary film ''A Struggle for Home: The Crimean Tatars'' in a Ukrainian–Qatari co-production. It depicts the history of the Crimean Tatars from 1783 up until 2014, with a special emphasis on the 1944 mass deportation.

At the Eurovision Song Contest 2016

The Eurovision Song Contest 2016 was the 61st edition of the Eurovision Song Contest. It took place in Stockholm, Sweden, following the country's victory at the with the song "Heroes" by Måns Zelmerlöw. Organised by the European Broadcasting ...

in Stockholm

Stockholm () is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, largest city of Sweden as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people liv ...

, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

, the Ukrainian Crimean Tatar singer Jamala performed the song "1944

Events

Below, the events of World War II have the "WWII" prefix.

January

* January 2 – WWII:

** Free French General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny is appointed to command French Army B, part of the Sixth United States Army Group in Nor ...

", which refers to the deportation of the Crimean Tatars in the eponymous year. Jamala, an ethnic Crimean Tatar born in exile in Kyrgyzstan, dedicated the song to her deported great-grandmother. She became the first Crimean Tatar to perform at Eurovision and also the first to perform with a song with lyrics in the Crimean Tatar language. She went on to win the contest, becoming the second Ukrainian artist to win the event. John, 13 May 2016

See also

* De-Tatarization of Crimea * Deportation of the Chechens and Ingush * Deportation of the Meskhetian Turks *List of ethnic cleansing campaigns

This article lists incidents that have been termed ethnic cleansing by some academic or legal experts. Not all experts agree on every case, particularly since there are a variety of definitions of the term ethnic cleansing. When claims of ethni ...

* List of genocides by death toll

* Population transfer in the Soviet Union

From 1930 to 1952, the government of the Soviet Union, on the orders of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin under the direction of the NKVD official Lavrentiy Beria, forcibly transferred populations of various groups. These actions may be classified ...

Comments

Citations

General and cited sources

Books

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Online news reports

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Journal articles

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *International and NGO sources

* * * * * *External links

* {{Crimea topics 1944 in the Soviet Union Anti-indigenous racism Crimea in World War II Crimean Tatar diaspora Crimes against humanity Deportation Ethnic cleansing in Europe Crimean Tatars Genocides in Europe Joseph Stalin Persecution of Muslims Persecution of Turkic peoples Political repression in the Soviet Union Soviet ethnic policy Soviet World War II crimes Tatarophobia Violence against Muslims