Symphony No. 9 (Vaughan Williams) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

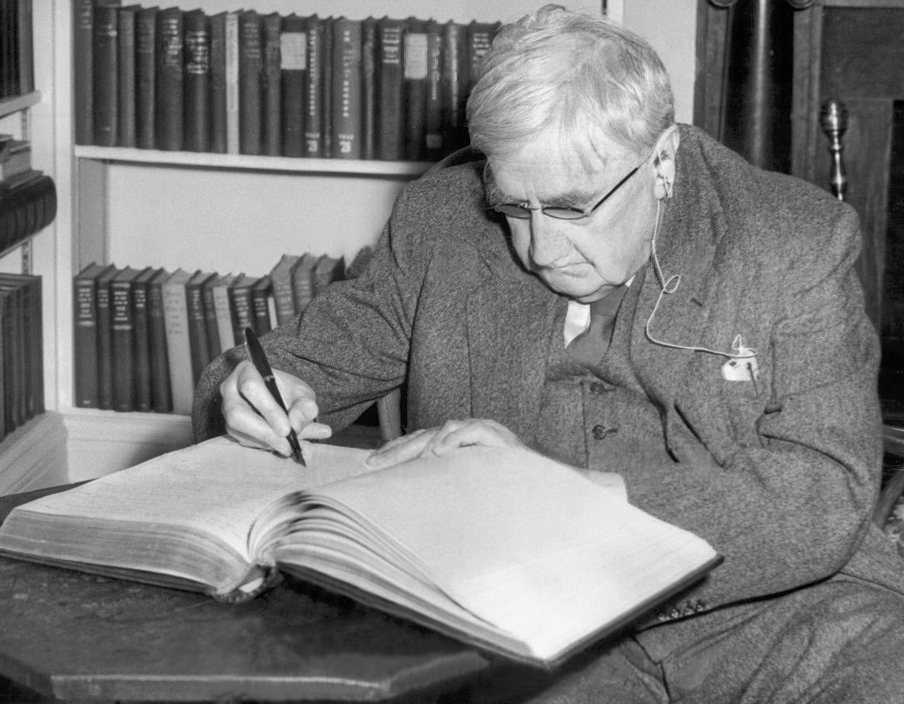

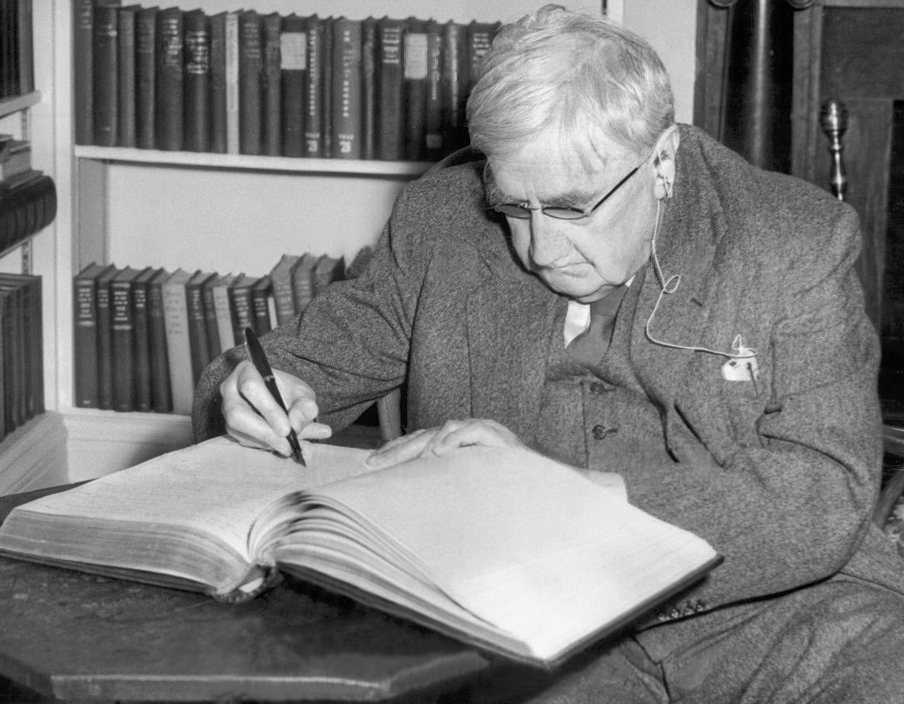

The Symphony No. 9 in E minor was the last symphony written by the English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams. He composed it during 1956 and 1957, and it was given its premiere performance in London by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by

The Symphony No. 9 in E minor was the last symphony written by the English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams. He composed it during 1956 and 1957, and it was given its premiere performance in London by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by

. The work received its North American premiere on 10 August, conducted by

"Vaughan Williams discarded programme in his Ninth Symphony"

''Journal of the RVW Society'', No 24, June 2002, p. 9

The Symphony No. 9 in E minor was the last symphony written by the English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams. He composed it during 1956 and 1957, and it was given its premiere performance in London by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by

The Symphony No. 9 in E minor was the last symphony written by the English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams. He composed it during 1956 and 1957, and it was given its premiere performance in London by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Sir Malcolm Sargent

Sir Harold Malcolm Watts Sargent (29 April 1895 – 3 October 1967) was an English conductor, organist and composer widely regarded as Britain's leading conductor of choral works. The musical ensembles with which he was associated include ...

on 2 April 1958, in the composer's eighty-sixth year. The work was received respectfully but, at first, without great enthusiasm. Its reputation has subsequently grown, and the symphony has entered the repertoire, in the concert hall and on record, with the majority of recordings from the 1990s and the 21st century.

In his early sketches for the symphony, Vaughan Williams made explicit reference to characters and scenes in Thomas Hardy's '' Tess of the d'Urbervilles''. By the time the symphony was complete he had deleted the programmatic details, but musical analysts have found many points in which the work nonetheless evokes the novel.

Background and first performances

By the mid-1950s Vaughan Williams, in his eighties, was regarded as the Grand Old Man of English music, greatly as he disliked the term. Between 1910 and 1955 he had composed eight symphonies, and early in 1956, before the premiere of the Eighth he began to think about and make sketches for a ninth. During the early stages of the composition of the symphony, Vaughan Williams conceived first a musical depiction ofSalisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of ...

, the Plain

In geography, a plain is a flat expanse of land that generally does not change much in elevation, and is primarily treeless. Plains occur as lowlands along valleys or at the base of mountains, as coastal plains, and as plateaus or uplands ...

and Stonehenge and then an evocation of Thomas Hardy's '' Tess of the d'Urbervilles'', set in the same surroundings. The programmatic elements disappeared as work progressed.Frogley (1987), pp. 49–50 and 57 Existing sketches show that in the early stages of composition certain passages related to specific people and events in the novel: in some of the manuscripts the first movement is headed "Wessex Prelude" and the heading "Tess" appears above sketches for the second movement. By the time the work was complete, the composer was at pains to characterise it as absolute music

Absolute music (sometimes abstract music) is music that is not explicitly 'about' anything; in contrast to program music, it is non- representational.M. C. Horowitz (ed.), ''New Dictionary of the History of Ideas'', , vol.1, p. 5 The idea of abs ...

:

The work was commissioned by and dedicated to the Royal Philharmonic Society

The Royal Philharmonic Society (RPS) is a British music society, formed in 1813. Its original purpose was to promote performances of instrumental music in London. Many composers and performers have taken part in its concerts. It is now a memb ...

. It was complete by November 1957 when a piano arrangement was played to a group of the composer's friends, including the composers Arthur Bliss

Sir Arthur Edward Drummond Bliss (2 August 189127 March 1975) was an English composer and conductor.

Bliss's musical training was cut short by the First World War, in which he served with distinction in the army. In the post-war years he qu ...

and Herbert Howells

Herbert Norman Howells (17 October 1892 – 23 February 1983) was an English composer, organist, and teacher, most famous for his large output of Anglican church music.

Life

Background and early education

Howells was born in Lydney, Gloucest ...

and the critic Frank Howes

Frank Stewart Howes (2 April 1891 – 28 September 1974) was an English music critic. From 1943 to 1960 he was chief music critic of ''The Times''. From his student days Howes gravitated towards criticism as his musical specialism, guided by the a ...

. A fortnight before the premiere, Vaughan Williams arranged (and paid for) a three-hour rehearsal at which the symphony was played through twice; after hearing the piece he made some minor adjustments in preparation for the premiere.

Sir Malcolm Sargent

Sir Harold Malcolm Watts Sargent (29 April 1895 – 3 October 1967) was an English conductor, organist and composer widely regarded as Britain's leading conductor of choral works. The musical ensembles with which he was associated include ...

conducted the first public performance at a Royal Philharmonic Society concert at the Royal Festival Hall, London on 2 April 1958, the central item in the programme, between Kodály's ''Concerto for Orchestra'' and Berlioz's ''Harold in Italy

''Harold en Italie,'' ''symphonie avec un alto principal'' (English: ''Harold in Italy,'' ''symphony with viola obbligato''), as the manuscript calls and describes it, is a four-movement orchestral work by Hector Berlioz, his Opus 16, H. 68, wr ...

''. He again conducted the symphony on 5 August 1958 at a Prom

A promenade dance, commonly called a prom, is a dance party for high school students. It may be offered in semi-formal black tie or informal suit for boys, and evening gowns for girls. This event is typically held near the end of the school y ...

concert, broadcast by the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...William Steinberg

William Steinberg (Cologne, August 1, 1899New York City, May 16, 1978) was a German-American conductor.

Biography

Steinberg was born Hans Wilhelm Steinberg in Cologne, Germany. He displayed early talent as a violinist, pianist, and composer, ...

at the Vancouver

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the List of cities in British Columbia, most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the ...

International Festival. Leopold Stokowski

Leopold Anthony Stokowski (18 April 1882 – 13 September 1977) was a British conductor. One of the leading conductors of the early and mid-20th century, he is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra and his appear ...

conducted the US premiere at Carnegie Hall, New York on 25 September,Schonberg, Harold C. "A Vaughan Williams Premiere; Stokowski Leads Ninth Symphony in U.S. Bow", ''The New York Times'', 26 September 1958, p. 22 and Sir John Barbirolli

Sir John Barbirolli ( Giovanni Battista Barbirolli; 2 December 189929 July 1970) was a British conductor and cellist. He is remembered above all as conductor of the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester, which he helped save from dissolution in 194 ...

conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra in the work in December of that year.

Music

The orchestral forces required are: *Woodwinds: piccolo, two flutes, twooboe

The oboe ( ) is a type of double reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites. The most common oboe plays in the treble or soprano range.

...

s, cor anglais, two clarinets (in B), bass clarinet (in B), two bassoons, contrabassoon, two alto saxophones (in E), tenor saxophone

The tenor saxophone is a medium-sized member of the saxophone family, a group of instruments invented by Adolphe Sax in the 1840s. The tenor and the alto are the two most commonly used saxophones. The tenor is pitched in the key of B (while ...

(in B)

*Brass: four horn

Horn most often refers to:

*Horn (acoustic), a conical or bell shaped aperture used to guide sound

** Horn (instrument), collective name for tube-shaped wind musical instruments

*Horn (anatomy), a pointed, bony projection on the head of various ...

s (in F), two trumpet

The trumpet is a brass instrument commonly used in classical and jazz ensembles. The trumpet group ranges from the piccolo trumpet—with the highest register in the brass family—to the bass trumpet, pitched one octave below the standard ...

s (in B), flügelhorn (in B), three trombone

The trombone (german: Posaune, Italian, French: ''trombone'') is a musical instrument in the brass family. As with all brass instruments, sound is produced when the player's vibrating lips cause the air column inside the instrument to vibrate ...

s, tuba

The tuba (; ) is the lowest-pitched musical instrument in the brass family. As with all brass instruments, the sound is produced by lip vibrationa buzzinto a mouthpiece. It first appeared in the mid-19th century, making it one of the ne ...

*Percussion: timpani

Timpani (; ) or kettledrums (also informally called timps) are musical instruments in the percussion family. A type of drum categorised as a hemispherical drum, they consist of a membrane called a head stretched over a large bowl traditionally ...

, side drum

The snare (or side drum) is a percussion instrument that produces a sharp staccato sound when the head is struck with a drum stick, due to the use of a series of stiff wires held under tension against the lower skin. Snare drums are often used in ...

, tenor drum A tenor drum is a membranophone without a snare. There are several types of tenor drums.

Early music

Early music tenor drums, or long drums, are cylindrical membranophone without snare used in Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque music. They consi ...

, bass drum, cymbals

A cymbal is a common percussion instrument. Often used in pairs, cymbals consist of thin, normally round plates of various alloys. The majority of cymbals are of indefinite pitch, although small disc-shaped cymbals based on ancient designs soun ...

, triangle

A triangle is a polygon with three edges and three vertices. It is one of the basic shapes in geometry. A triangle with vertices ''A'', ''B'', and ''C'' is denoted \triangle ABC.

In Euclidean geometry, any three points, when non- colline ...

, large gong

A gongFrom Indonesian and ms, gong; jv, ꦒꦺꦴꦁ ; zh, c=鑼, p=luó; ja, , dora; km, គង ; th, ฆ้อง ; vi, cồng chiêng; as, কাঁহ is a percussion instrument originating in East Asia and Southeast Asia. Gongs ...

, tam-tam

A gongFrom Indonesian and ms, gong; jv, ꦒꦺꦴꦁ ; zh, c=鑼, p=luó; ja, , dora; km, គង ; th, ฆ้อง ; vi, cồng chiêng; as, কাঁহ is a percussion instrument originating in East Asia and Southeast Asia. Gongs ...

, deep bell

A bell is a directly struck idiophone percussion instrument. Most bells have the shape of a hollow cup that when struck vibrates in a single strong strike tone, with its sides forming an efficient resonator. The strike may be made by an inte ...

s, glockenspiel, xylophone

The xylophone (; ) is a musical instrument in the percussion family that consists of wooden bars struck by mallets. Like the glockenspiel (which uses metal bars), the xylophone essentially consists of a set of tuned wooden keys arranged in ...

, celesta

*Strings: two harps, and strings

String or strings may refer to:

*String (structure), a long flexible structure made from threads twisted together, which is used to tie, bind, or hang other objects

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Strings'' (1991 film), a Canadian anim ...

The symphony is in four movements. Timings in performance vary considerably: at the premiere Sargent and the Royal Philharmonic took 30m 25s, which is nearer than most subsequent performances on record to the composer's metronome markings, but is felt by some critics to be too fast in places. In preparation for the first commercial recording of the work in August 1958, Sir Adrian Boult

Sir Adrian Cedric Boult, CH (; 8 April 1889 – 22 February 1983) was an English conductor. Brought up in a prosperous mercantile family, he followed musical studies in England and at Leipzig, Germany, with early conducting work in London ...

discussed the ending of the last movement with Vaughan Williams, which he felt was too abrupt. Vaughan Williams suggested that he could play that section "a good deal slower" if he wished while he considered Boult's suggestion that he add 20 or 30 measures.Frogley (2001), p. 21 Timings of studio recordings of the work have ranged from 29m 45s (Kees Bakels

Kees Bakels (born 14 January 1945, in Amsterdam) is a Dutch conductor.

Bakels began his musical career as a violinist, and later studied conducting at the Amsterdam Conservatory and the Accademia Musicale Chigiana in Siena, Italy. He has appea ...

, 1996) to 38m 30 ( André Previn, 1971), with 34 minutes or so a more typical duration.

1. Moderato maestoso

In the composer's published analysis the Moderato first movement is described as not in strict sonata form but obeying the general principles of statement, contrast and repetition.Manning, p. 391 The symphony opens inE minor

E minor is a minor scale based on E, consisting of the pitches E, F, G, A, B, C, and D. Its key signature has one sharp. Its relative major is G major and its parallel major is E major.

The E natural minor scale is:

:

Changes needed ...

, in time, with a held unison E in four octaves, followed by a slow theme for low brasses and winds over the sustained E. This leads to the first solo entrance of the three saxophones in a solemn theme in triads over a quiet E minor chord. The clarinets, accompanied by harp chords, introduce a gentler theme in G minor

G minor is a minor scale based on G, consisting of the pitches G, A, B, C, D, E, and F. Its key signature has two flats. Its relative major is B-flat major and its parallel major is G major.

According to Paolo Pietropaolo, it is the con ...

that elides into the G major

G major (or the key of G) is a major scale based on G, with the pitches G, A, B, C, D, E, and F. Its key signature has one sharp. Its relative minor is E minor and its parallel minor is G minor.

The G major scale is:

Notable composi ...

that conventional sonata form would suggest. This returns in fuller form later in the movement, forming the recapitulation section, and now played by a solo violin, before the movement returns to the opening theme and ends with a saxophone cadence (''à la Napolitaine'', in the composer's phrase).

2. Andante sostenuto

The slow movement, markedAndante

Andante may refer to:

Arts

* Andante (tempo), a moderately slow musical tempo

* Andante (manga), ''Andante'' (manga), a shōjo manga by Miho Obana

* Andante (song), "Andante" (song), a song by Hitomi Yaida

* "Andante, Andante", a 1980 song by A ...

sostenuto, opens in G minor, time, with a theme for the solo flügelhorn. According to the musicologist Alain Frogley and others, the composer's original programmatic conceptions are essentially unaltered in the score despite his deletion of the labelling of themes, and in the opening it is possible to hear the sound of the wind blowing through Stonehenge.Frogley, pp. 50–51Horton, pp. 224–225 Later in the movement the music evokes Tess, the pursuing constabulary, her arrest and the bell striking eight before her hanging. Vaughan Williams, avoiding mention of the original programme, describes the flügelhorn theme as "borrowed from an early work of the composer's, luckily long since scrapped, but changed so that its own father would hardly recognize it". He continues: The movement closes on a pianissimo chord of C major sustained across four bars.

3. Scherzo

Thescherzo

A scherzo (, , ; plural scherzos or scherzi), in western classical music, is a short composition – sometimes a movement from a larger work such as a symphony or a sonata. The precise definition has varied over the years, but scherzo often re ...

third movement is marked Allegro pesante

''Pesante'' () is a musical term, meaning "heavy and ponderous."

References

Musical terminology

Musical notation

{{music-theory-stub ...

, and moves between and time. After an opening fortissimo brass discord, accompanied by a rhythmic pattern on the side drum, the saxophones play the first main theme, which is followed by a second theme, in , and, reverting to , a third. A subsidiary theme is developed in canon. The music is interrupted by a repetition of the opening dissonance, out of which the solo B-flat saxophone and the side drum bring the movement to a quiet end.

4. Finale

The last movement, marked Andante tranquillo, is in two distinct sections, the first in repeated binary form and the second a sonata allegro with coda. The first section begins with a long cantilena on the violins and then the violas, with clarinet counterpoint. The second theme, for horns, is followed by a repetition of both themes, before a short phrase that occurs throughout the movement introduces the second section, a viola theme, soft at first and becoming louder and contrapuntal, for full orchestra before ending on an E major triad, fortissimo but fading away to silence.Critical reception

According to Vaughan Williams's biographer Michael Kennedy, after the first performances, "there was no denying the coolness of the critics' reception of the music. Its enigmatic mood puzzled them, and more attention was therefore paid to the use of the flügel horn and to the flippant programme note." The flügelhorn player at the premiere remarked that all the press coverage was about the instrument, to the detriment of serious discussion of the symphony as a work. An example of what Kennedy describes as the composer's flippancy in his programme note concerns the instrumentation: In the American journal ''Notes

Note, notes, or NOTE may refer to:

Music and entertainment

* Musical note, a pitched sound (or a symbol for a sound) in music

* ''Notes'' (album), a 1987 album by Paul Bley and Paul Motian

* ''Notes'', a common (yet unofficial) shortened versio ...

'', R. Murray Schafer

Raymond Murray Schafer (18 July 1933 – 14 August 2021) was a Canadian composer, writer, music educator, and environmentalist perhaps best known for his World Soundscape Project, concern for acoustic ecology, and his book ''The Tuning of th ...

commented that although most libraries would wish to acquire the score because of Vaughan Williams's reputation as a symphonist, "I find it difficult...to discover much more than a numerical value in the work". He complained about the saxophones and flügelhorn: "all this extra color seems to be employed simply in thickening the middle-orchestra texture. … The formal mastery is still present, but I don't think it saves the work". Other critics in America were more impressed. In the ''Musical Courier

The ''Musical Courier'' was a weekly 19th- and 20th-century American music trade magazine that began publication in 1880.

The publication included editorials, obituaries, announcements, scholarly articles and investigatory writing about musical ...

'', Gideon Waldrop described the symphony as "a work of beauty ... lyricism, sheer tonal beauty and thorough craftsmanship were in evidence throughout" and in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'', Harold C. Schonberg

Harold Charles Schonberg (29 November 1915 – 26 July 2003) was an American music critic and author. He is best known for his contributions in ''The New York Times'', where he was chief music critic from 1960 to 1980. In 1971, he became the fi ...

wrote that "the symphony is packed with strong personal melody from beginning to end ... A mellow glow suffuses the work, as it does the work of many veteran composers who seem to gaze retrospectively over their careers ... the Ninth Symphony is a masterpiece".

In the decades following his death, the music of Vaughan Williams was to a considerable extent ignored by musical academics and critics, although not by the public: his music remained popular in the concert hall and on record. In the mid-1990s the critical and musicological tide turned in his favour. So far as the Ninth Symphony was concerned, the earlier view that it said nothing new began to be supplanted by the recognition that although it was, as ''The Times'' put it in 2008, "the synthesis and summation of all that had gone before", the music was visionary, violent, elusive and ambiguous. In 2011, in a note for the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra

The San Francisco Symphony (SFS), founded in 1911, is an American orchestra based in San Francisco, California. Since 1980 the orchestra has been resident at the Louise M. Davies Symphony Hall in the city's Hayes Valley neighborhood. The San F ...

, Larry Rothe wrote, "Like Beethoven’s final symphony, this one portrays huge conflicts and superhuman striving. Then, in its midst, a light-drenched seascape unfolds, but the vision retreats as suddenly as it appeared. Vaughan Williams had not composed music so angry and assertive since his Sixth Symphony". Frogley and others believe that the work became better understood once the programmatic element became widely known.Barr, John"Vaughan Williams discarded programme in his Ninth Symphony"

''Journal of the RVW Society'', No 24, June 2002, p. 9

Recordings

Notes, references and sources

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * {{Authority control Symphony 009 1957 compositions Compositions in E minor Adaptations of works by Thomas Hardy