Sydney Selwyn on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

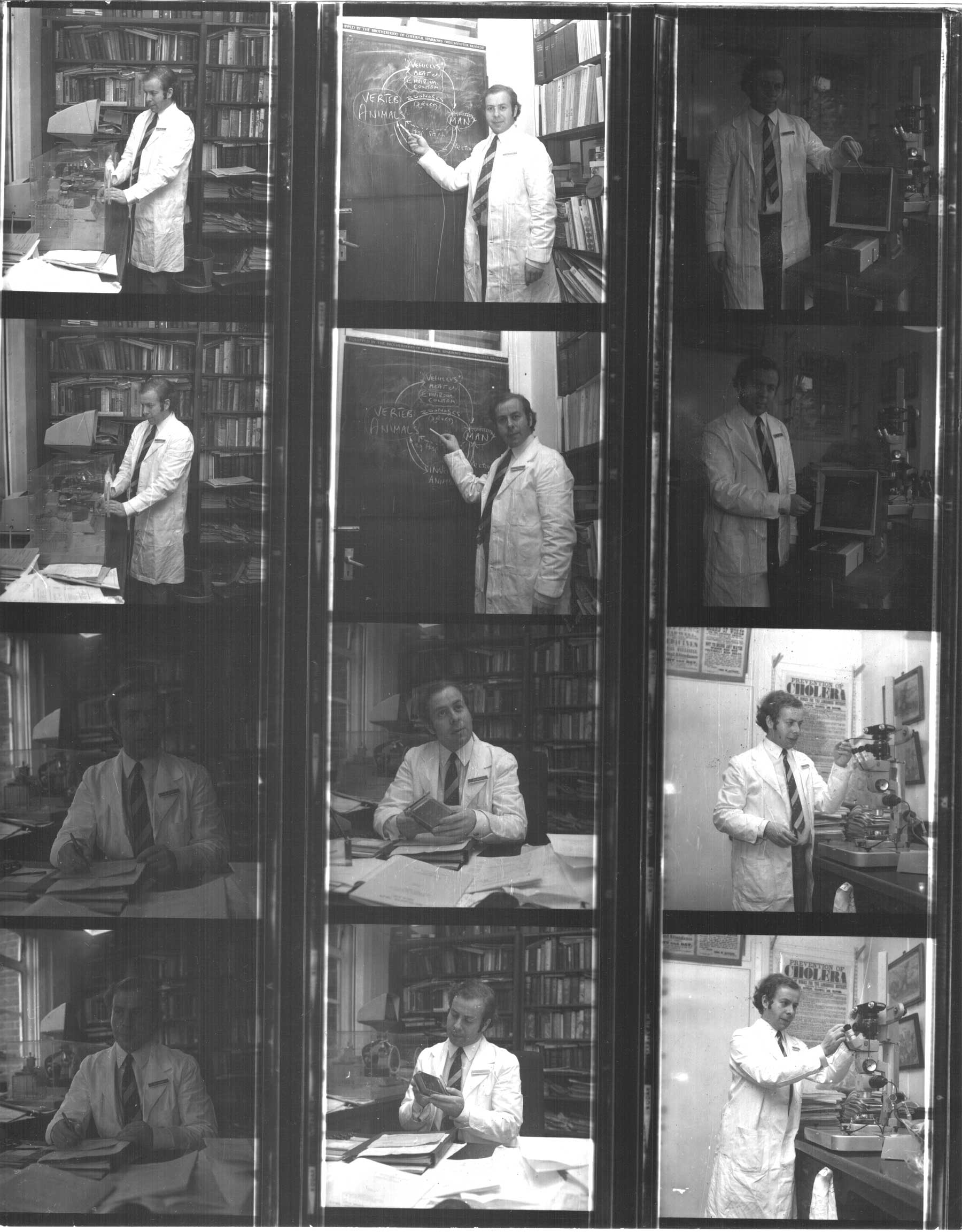

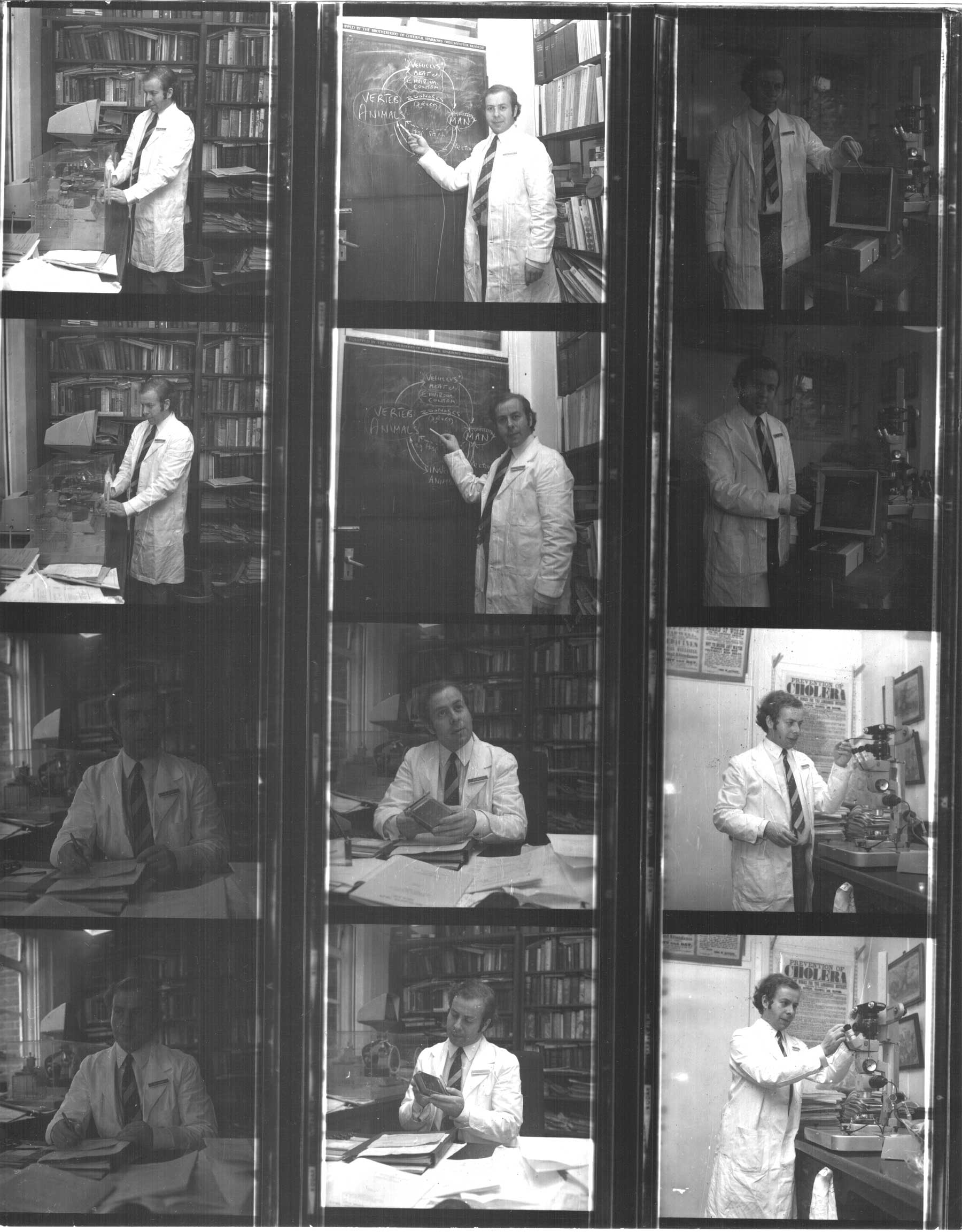

Sydney Selwyn (7 November 1934 – 8 November 1996) was a British physician, medical scientist, and professor.

He was a medical

During the 1970s and 1980s he played a significant role as a pioneer in the field of

During the 1970s and 1980s he played a significant role as a pioneer in the field of

Whilst barely in his 50s Professor Selwyn was diagnosed as suffering from "

Whilst barely in his 50s Professor Selwyn was diagnosed as suffering from "

The Selwyn Prize

is awarded by The Faculty of History And Philosophy of Medicine and Pharmacy at the historic premises of the

President of the Osler Club (1991–92)

Bartholomew's Hospital London

The Selwyn prize is awarded to the best candidate in the examination for the Diploma in the Philosophy of Medicine and it is usually presented at the John Locke Lecture.

(Alternative copy of obituary by Robin Price)

Google Scholar – links to some publications by the late Prof S Selwyn

cvphm.org

* ttp://www.veryreasonable.com/sydney/ Further information including more external links* ttp://www.bbc.co.uk/shropshire/features/2003/08/frank_bough.shtml Frank Bough former presenter for the BBC, including of "Nationwide"* The ttps://web.archive.org/web/20080513070318/http://www.anthonynolan.org.uk/ Anthony Nolan Trusta charitable organisation devoted to supporting all those with immune system disorders. {{DEFAULTSORT:Selwyn, Sydney 20th-century English medical doctors English scientists English medical historians 1934 births 1996 deaths Alumni of the University of Edinburgh People educated at Leeds Grammar School Medical doctors from Yorkshire Neurological disease deaths in England Deaths from multiple system atrophy Academics of the University of Edinburgh Academics of the University of London British microbiologists 20th-century English historians Presidents of the Osler Club of London

microbiologist

A microbiologist (from Ancient Greek, Greek ) is a scientist who studies microscopic life forms and processes. This includes study of the growth, interactions and characteristics of Microorganism, microscopic organisms such as bacteria, algae, f ...

with an interest in bacteriology Bacteriology is the branch and specialty of biology that studies the morphology, ecology, genetics and biochemistry of bacteria as well as many other aspects related to them. This subdivision of microbiology involves the identification, classificat ...

, authority on the history of medicine, avid collector, writer, lecturer, world traveller, and occasional radio and TV broadcaster.

Life

Sydney Selwyn was born inLeeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by populati ...

, 7 November 1934 and died in London, 8 November 1996.

Selwyn's parents owned and ran a butcher shop in Leeds and originally expected him to follow them in their trade or at least something similar. He chose instead to devote his life to science and academia. As a working-class boy growing up in England in the 1930s, and during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, it was a great achievement for him to win a scholarship to be educated at the prestigious and ancient Leeds Grammar School

Leeds Grammar School was an independent school founded 1552 in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. Originally a male-only school, in August 2005 it merged with Leeds Girls' High School to form The Grammar School at Leeds. The two schools physically ...

. He then went on to study at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

from which he graduated with a BSc, MB ChB, and gained an MD in hospital infection.

He worked briefly (from 1959–1960) as a house physician in Edinburgh City Hospital

The Edinburgh City Hospital (also known as the Edinburgh City Hospital for Infectious Diseases or the City Hospital at Colinton Mains) was a hospital in Colinton, Edinburgh, opened in 1903 for the treatment of infectious diseases. As the pattern ...

before becoming a lecturer in bacteriology at University of Edinburgh Medical School

The University of Edinburgh Medical School (also known as Edinburgh Medical School) is the medical school of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland and the United Kingdom and part of the College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine. It was esta ...

(1961–1966). In 1967 he became one of the youngest-ever visiting professors for the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of h ...

(WHO) at Baroda University in India, as well as a WHO SE Asia medical consultant. He toured India extensively, visiting not only towns and cities but also many remote rural areas as part of his WHO project to greatly improve the standards of health and hygiene at various hospitals. He returned from India to become first Reader, then Consultant and finally Professor of Medical Microbiology

Medical microbiology, the large subset of microbiology that is applied to medicine, is a branch of medical science concerned with the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases. In addition, this field of science studies various ...

at Westminster Medical School, University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

.

Whilst continuing as Professor at Westminster Medical School he also simultaneously became Professor of Medical Microbiology at Charing Cross Hospital Medical School

Charing Cross Hospital Medical School (CXHMS) is the oldest of the constituent medical schools of Imperial College School of Medicine.

Charing Cross remains a hospital on the forefront of medicine; in recent times pioneering the clinical use of ...

, thus running two separate departments (each with its own research and teaching teams) in two different teaching hospitals.

During the 1970s and 1980s he played a significant role as a pioneer in the field of

During the 1970s and 1980s he played a significant role as a pioneer in the field of bone marrow transplant

Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) is the transplantation of multipotent hematopoietic stem cells, usually derived from bone marrow, peripheral blood, or umbilical cord blood in order to replicate inside of a patient and to produce ...

ation. In particular he was closely involved with the treatment of two ground-breaking cases; those of Simon Bostic and Anthony Nolan. Anthony Nolan's mother went on to found the charitable Anthony Nolan Trust.

Research in the fields of bacteriology and medical microbiology were not his only professional interests. Despite his demanding research activities he also developed world-class expertise in the history and development of medicine, from the dawn of civilisation to the then present day, and also became a distinguished and popular lecturer in that subject.

He was honorary archivist of the Royal College of Pathology of which he was also a Fellow (FRCPath

The Royal College of Pathologists (RCPath) is a professional membership organisation.

Its main function is the overseeing of postgraduate training, and its Fellowship Examination (FRCPath) is recognised as the standard assessment of fitness to pr ...

), President of the Faculty of History and Philosophy of Medicine and Pharmacy president of the Medical Sciences Historical Society and a Liveryman of the Society of Apothecaries Worshipful where he was also Director of the DHMSA (the Diploma of the History of Medicine at the Society of Apothecaries), an important and popular course and diploma, to which some students even flew in from across Europe (and one from Canada) each week to attend! He led this course to new heights of popularity over the seventeen years of his tenure, until ill health forced his retirement in 1990.

He was an active member of many prestigious research and educationally based clubs and organisations, for example being President of the Osler Club of London and President of the Harveian Society of London (1991–92).

Writer

He wrote, as well as co-authored, a number of books and a great number of scientific papers. One of his most accessible and delightful publications (in collaboration with his predecessor Professor R W Lacey and research assistant and colleague Mohammed Bakhtiar) was "The beta-lactam antibiotics: penicillins and cephalosporins in perspective."Design for a banknote

His diverse interests in many fields often led to involvement in unusual projects both large and small. For example, as an authority on the history of medicine he was approached by theBank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government of ...

to suggest a medical theme for the £10 note. He not only suggested Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English Reform movement, social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during t ...

as a subject but went on to recommend they base their design on a "classic" scene of her carrying her famous lamp, which had earned her the nickname "The Lady with the Lamp," around a ward of the Military Hospital at Scutari during the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

. When the Bank of England was unable to track down the particular steel engraving he had recommended he lent them a copy of the rare print from his collection.

The Florence Nightingale £10 banknote was first issued in February 1975 and proved extremely popular (leading for a while to the £10 note being nicknamed "a Flo" by some, as in "excuse me – have you got change for a Flo"). It was not withdrawn until May 1994.

Broadcasts

Following several brief but popular broadcasts he gave on the dangers of licking postage stamps (particularly in countries that used crude forms of "cow gum" made from bones that could contain a worrying variety of still active diseases) he was consulted by De La Rue and the Walsall Security Printing companies who were early pioneers of self-adhesive stamps. One of the resulting projects he became involved with was the development of a set of self adhesive stamps featuring historic post boxes forGibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

.

He appeared a number of times as "a medical expert" on television. For example, in the 1970s he was interviewed by Frank Bough

Francis Joseph Bough (; 15 January 1933 – 21 October 2020) was an English television presenter. He was best known as the former host of BBC sports and current affairs shows including ''Grandstand'', '' Nationwide'' and '' Breakfast Time'', whi ...

on the BBC's then popular " Nationwide" programme shown on prime family-time TV. Selwyn introduced himself on the programme as a microbiologist and bacteriologist with an interest in dermatological matters such as the flora and fauna of our skin. He went on to explain that through his researches he had come to realise most of us were using far too many chemical-based cosmetics and, as a result, disrupting the ecology of our skin. This resulted, he said, in building-up a dependence on more of these otherwise unnecessary cosmetics. He suggested that clean water and small amounts of simple soap were ample and that most of the available cosmetics and personal hygiene products being advertised were not just unnecessary but also potentially harmful especially through habitual over use.

He worked with the BBC on a number of projects which included, for example, "Horizon

The horizon is the apparent line that separates the surface of a celestial body from its sky when viewed from the perspective of an observer on or near the surface of the relevant body. This line divides all viewing directions based on whether i ...

" documentaries and "Microbes and Men" (1974).

Last years and final illness

Whilst barely in his 50s Professor Selwyn was diagnosed as suffering from "

Whilst barely in his 50s Professor Selwyn was diagnosed as suffering from "multiple system atrophy

Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a rare neurodegenerative disorder characterized by autonomic dysfunction, tremors, slow movement, muscle rigidity, and postural instability (collectively known as parkinsonism) and ataxia. This is caused by progr ...

" (MSA), and told he might have only around 5–9 years left to live. However, even after being forced to take early retirement several years later he continued to write and publish in addition to travelling.

Despite his physical decline during his last decade or so he managed to retain not only his dignity and sense of humour but his passion for life also. Refusing to lose his mobility or become passive he instead delighted in learning to drive a new electrically driven self-propelled wheelchair. Eventually, as his condition worsened he lost his ability to speak, but, again undaunted, he learned to communicate by typing a single letter at a time on his lightwriter

Lightwriters are a type of speech-generating device. The person who cannot speak types a message on the keyboard, and this message is displayed on two displays, one facing the user and a second outfacing display facing the communication partner or ...

which had a built-in voice synthesiser.

He enjoyed a private family party in his honour for his 62nd birthday and was as full of enthusiasm and humour as ever (though of course had some difficulty in expressing it). He died peacefully at home later the following day.

Memorials

A room in the laboratory block of theCharing Cross Hospital

Charing Cross Hospital is an acute general teaching hospital located in Hammersmith, London, United Kingdom. The present hospital was opened in 1973, although it was originally established in 1818, approximately five miles east, in central Lond ...

(now part of Imperial College) used for both meetings and teaching or training has been named "The Sydney Selwyn Room" in his memory. His photograph and a plaque summarising his contribution to the hospital is displayed on the wall.

Each yearThe Selwyn Prize

is awarded by The Faculty of History And Philosophy of Medicine and Pharmacy at the historic premises of the

Worshipful Society of Apothecaries

The Worshipful Society of Apothecaries of London is one of the livery companies of the City of London. It is one of the largest livery companies (with over 1,600 members in 2012) and ranks 58th in their order of precedence.

The society is a m ...

in London to the best candidate from the previous year in the examination for the Diploma in the Ethics and Philosophy of Healthcare (Philosophy of Medicine). Receiving this prize, which is usually presented at the John Locke Lecture, is an impressive achievement as the standard and quality of candidates entering the examination is generally very high.

The winner of the 2021 Sydney Selwyn Lecture was Dr Lotte Elton.

With Dr Deniz Kaya & Dr Andrew Nanapragasam - both Highly Commended

Previous prize winners are:

* 2020 - Dr Mary Fletcher

* 2019 - Dr Sara Dahlen

* 2018 - Dr Tina Matthews

* 2016 - Daniel Di Francesco

* 2012 - Miss Evelyn Brown

* 2010 - Dr Margaret Baker

* 2009 – Christopher Mark Crawshaw

* 2008 – Dr. Katherine Elen Catford

* 2007 – Michael Trent Herdman

* 2006 – Paul Bingham & Edith Rom

* 2005 – Caroline Bagley & Ben Whitelaw

* 2004 – Robert Ali

See also

* MSA (Multiple system Atrophy)References

Further reading

* The beta-lactam antibiotics: penicillins and cephalosporins in perspective by Sydney Selwyn; R W Lacey; Mohammed Bakhtiar / London : Hodder and Stoughton, 1980External links

President of the Osler Club (1991–92)

Bartholomew's Hospital London

The Selwyn prize is awarded to the best candidate in the examination for the Diploma in the Philosophy of Medicine and it is usually presented at the John Locke Lecture.

(Alternative copy of obituary by Robin Price)

Google Scholar – links to some publications by the late Prof S Selwyn

cvphm.org

* ttp://www.veryreasonable.com/sydney/ Further information including more external links* ttp://www.bbc.co.uk/shropshire/features/2003/08/frank_bough.shtml Frank Bough former presenter for the BBC, including of "Nationwide"* The ttps://web.archive.org/web/20080513070318/http://www.anthonynolan.org.uk/ Anthony Nolan Trusta charitable organisation devoted to supporting all those with immune system disorders. {{DEFAULTSORT:Selwyn, Sydney 20th-century English medical doctors English scientists English medical historians 1934 births 1996 deaths Alumni of the University of Edinburgh People educated at Leeds Grammar School Medical doctors from Yorkshire Neurological disease deaths in England Deaths from multiple system atrophy Academics of the University of Edinburgh Academics of the University of London British microbiologists 20th-century English historians Presidents of the Osler Club of London