Sydney Barber Josiah Skertchly on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sydney Barber Josiah Skertchly (14 December 1850 – 2 February 1926) was an English and later Australian botanist and geologist. He described and mapped the geology of

He then worked as assistant curator to the Geological Society, London, with Sir

He then worked as assistant curator to the Geological Society, London, with Sir

Darwin Correspondence Project: Sydney Barber Josiah Skertchly

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Skertchly, Sydney Barber Josiah Australian geologists 1850 births 1926 deaths Australian naturalists People from Anstey, Leicestershire English emigrants to Australia People from Brisbane Alumni of Imperial College London Royal Society of Queensland

East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

and The Fens

The Fens, also known as the , in eastern England are a naturally marshy region supporting a rich ecology and numerous species. Most of the fens were drained centuries ago, resulting in a flat, dry, low-lying agricultural region supported by a ...

, travelled the world exploring geology and other aspects of science, and became influential in scientific societies in Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

.

Biography

Early life

Born in Anstey,Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ; postal abbreviation Leics.) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East Midlands, England. The county borders Nottinghamshire to the north, Lincolnshire to the north-east, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire t ...

, Skertchly was the son of an English engineer, Joseph Skertchly, and Sarah Moseley, née Barber. He was educated at King Edward's School, Ashby-de-la-Zouch

Ashby-de-la-Zouch, sometimes spelt Ashby de la Zouch () and shortened locally to Ashby, is a market town and civil parish in the North West Leicestershire district of Leicestershire, England. The town is near to the Derbyshire and Staffordshire ...

where he won the Queen's gold medal for science. He studied geology at the Royal School of Mines

The Royal School of Mines comprises the departments of Earth Science and Engineering, and Materials at Imperial College London. The Centre for Advanced Structural Ceramics and parts of the London Centre for Nanotechnology and Department of Bioe ...

(later Imperial College, London

Imperial College London (legally Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) is a public research university in London, United Kingdom. Its history began with Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, who developed his vision for a cu ...

) under Sir Ralph Tate

Ralph Tate (11 March 1840 – 20 September 1901) was a British-born botanist and geologist, who was later active in Australia.

Early life

Tate was born at Alnwick in Northumberland, the son of Thomas Turner Tate (1807–1888), a teacher of math ...

and Thomas H. Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

.Australian Dictionary of Biography, ''Skertchly''. 1988.

Career

Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

. In 1869 he began to travel, becoming assistant geologist to Ismail Pasha, khedive

Khedive (, ota, خدیو, hıdiv; ar, خديوي, khudaywī) was an honorific title of Persian origin used for the sultans and grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire, but most famously for the viceroy of Egypt from 1805 to 1914.Adam Mestyan"Kh ...

of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

. He worked in East Anglia for the British Geological Survey

The British Geological Survey (BGS) is a partly publicly funded body which aims to advance geoscientific knowledge of the United Kingdom landmass and its continental shelf by means of systematic surveying, monitoring and research.

The BGS h ...

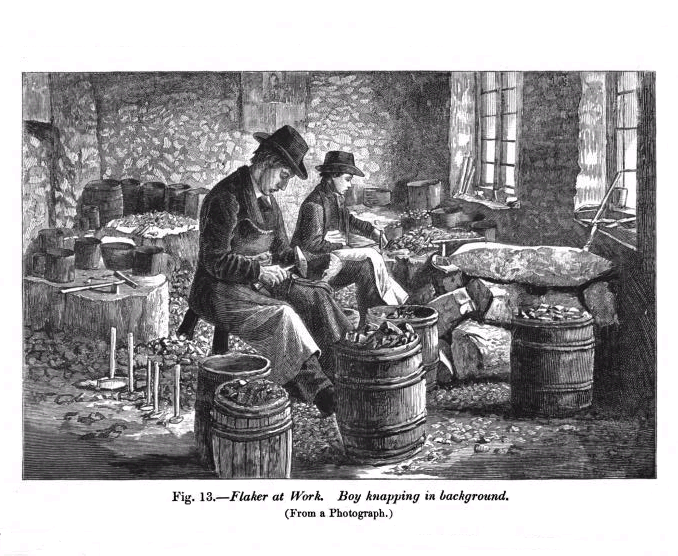

, studying and making maps of the geologically young strata there, as well as writing on the gun-flint industry which exploited the local flints. He described and named the Brandon Beds which lie under the Boulder clay

Boulder clay is an unsorted agglomeration of clastic sediment that is unstratified and structureless and contains gravel of various sizes, shapes, and compositions distributed at random in a fine-grained matrix. The fine-grained matrix consists ...

.

Skertchly sent Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

a copy of his ''Geology of the Fenland'' in 1878. Darwin replied with a gift of his ''Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

''. He also corresponded with Darwin's rival and co-discoverer of natural selection, Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was a British naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution through natural se ...

.

He travelled to California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and eas ...

, and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, studying and writing on geology and wider scientific subjects. He pioneered the first ever series of science textbooks written by scientists rather than school teachers, and a system for showing relief on maps. He became professor of Botany in Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

. When war broke out in 1891 between China and Japan, he moved to Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

, Australia. He gave many lectures on geology there, and wrote on science and natural history for the ''Brisbane Courier

''The Courier-Mail'' is an Australian newspaper published in Brisbane. Owned by News Corp Australia, it is published daily from Monday to Saturday in tabloid format. Its editorial offices are located at Bowen Hills, in Brisbane's inner norther ...

''.

Societies

Skertchly became a member of the Geological Society, London, in 1871, and of theRoyal Anthropological Institute

The Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (RAI) is a long-established anthropological organisation, and Learned Society, with a global membership. Its remit includes all the component fields of anthropology, such as biolo ...

in 1880. He was president of the Royal Society of Queensland

The Royal Society of Queensland was formed in Queensland, Australia in 1884 from the Queensland Philosophical Society, Queensland's oldest scientific institution, with royal patronage granted in 1885.

The aim of the Society is "Progressing scie ...

in 1898. He founded and was the first president of the Field Naturalists' Club in 1906. He was examining board president of the Queensland Institute of Ophthalmic Opticians from 1910 to 1925, and president of the Child Study Association of Queensland.

Family and later life

Skertchly married Rachel Ellen Kemp on 26 June 1871 in London, and they travelled around France and Italy together. She illustrated ''Colouration in Animals and Plants'' (1886) for him. They had three children. A daughter, Ruby, who married Edward James Cooper of 'Birribon',Carrara

Carrara ( , ; , ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, in central Italy, of the province of Massa and Carrara, and notable for the white or blue-grey marble quarried there. It is on the Carrione River, some Boxing the compass, west-northwest o ...

near Nerang, Queensland

Nerang is a town and suburb in the City of Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia. In the , Nerang had a population of 16,864 people.

Geography

The Nerang River flows through the locality from south to east, passing through the town. The river ult ...

in Australia and two sons, Harold Brandon and Ethelbert Forbes. Both sons died during military service. The Skertchlys retired to Nerang near their daughter and her family. Rachel Skertchly died in 1919 and Professor Skertchly died on 2 February 1926 in Molendinar, Queensland

Molendinar is a mixed-use suburb in the City of Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia. In the , Molendinar had a population of 6,375 people.

Geography

The suburb is bounded by Smith Street to the north, Olsen Avenue to the east, the Southport Ne ...

. Both are buried in Nerang cemetery.

Works

* (1877). ''The Geology of the Fenland'' * with Whitaker, William (1878?). ''The Geology of South-Western Norfolk and of Northern Cambridgeshire: (Explanation of Sheet 65)''. * (1878). ''The Physical System of the Universe. An outline of physiography''. * with Miller, S.H. (1878). ''The Fenland past and present ... With engravings, maps and diagrams''. * (1879). ''On the manufacture of Gun-Flints, the methods of excavating for flint, the age of palæolithic man, and the connection between neolithic art and the gun-flint trade''. * completing work of Tylor, Alfred (1886). ''Colouration in Animals and Plants''. * (1894) ''The future of the Port of Shanghai : a geological study''. * (1898). ''On the geology of the country round Stanthorpe and Warwick, South Queensland,: With especial reference to the tin and gold fields and the silver deposits''. Queensland: Geological survey.See also

*Adaptive Coloration in Animals

''Adaptive Coloration in Animals'' is a 500-page textbook about camouflage, warning coloration and mimicry by the Cambridge zoologist Hugh Cott, first published during the Second World War in 1940; the book sold widely and made him famous.

The ...

(Cott, 1940)

* The Colours of Animals

''The Colours of Animals'' is a zoology book written in 1890 by Sir Edward Bagnall Poulton (1856–1943). It was the first substantial textbook to argue the case for Darwinian selection applying to all aspects of animal coloration. The book al ...

(Poulton, 1890)

References

Bibliography

* *External links

Darwin Correspondence Project: Sydney Barber Josiah Skertchly

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Skertchly, Sydney Barber Josiah Australian geologists 1850 births 1926 deaths Australian naturalists People from Anstey, Leicestershire English emigrants to Australia People from Brisbane Alumni of Imperial College London Royal Society of Queensland