Swing Riots on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Swing Riots were a widespread uprising in 1830 by agricultural workers in southern and eastern England in protest of agricultural mechanisation and harsh working conditions. The riots began with the destruction of threshing machines in the Elham Valley area of East Kent in the summer of 1830 and by early December had spread through the whole of

The Swing Riots were a widespread uprising in 1830 by agricultural workers in southern and eastern England in protest of agricultural mechanisation and harsh working conditions. The riots began with the destruction of threshing machines in the Elham Valley area of East Kent in the summer of 1830 and by early December had spread through the whole of

Starting in the south-eastern county of

Starting in the south-eastern county of

The Saviour City: Beneficial effects of urbanization in England and Wales

''in'' Douglas. Companion Encyclopedia of Geography: The Environment and Humankind. p. 297 Not all rioters were farm workers since the list of those punished included rural artisans, shoemakers, carpenters, wheelwrights, blacksmiths and cobblers. One of those hanged was reported to have been charged only because he had knocked the hat off the head of a member of the Baring banking family. Many of the protesters who were transported had their sentences remitted in 1835.

Eventually, the farmers agreed to raise wages, and the parsons and some landlords reduced the tithes and rents. However, many farmers reneged on the agreements, and the unrest increased.

Many people advocated political reform as the only solution to the unrest, one of them being the radical politician and writer

Eventually, the farmers agreed to raise wages, and the parsons and some landlords reduced the tithes and rents. However, many farmers reneged on the agreements, and the unrest increased.

Many people advocated political reform as the only solution to the unrest, one of them being the radical politician and writer

John Owen Smith, "Headley & Selborne workhouse riot of 1830" "The Captain Swing rebellion in Sussex"

*Captain Swing Reconsidered. Papers published in ''Southern History'' vol.32 (201

{{Authority control 1830 riots 1830 in England English Poor Laws Riots and civil disorder in England History of agriculture in England William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

The Swing Riots were a widespread uprising in 1830 by agricultural workers in southern and eastern England in protest of agricultural mechanisation and harsh working conditions. The riots began with the destruction of threshing machines in the Elham Valley area of East Kent in the summer of 1830 and by early December had spread through the whole of

The Swing Riots were a widespread uprising in 1830 by agricultural workers in southern and eastern England in protest of agricultural mechanisation and harsh working conditions. The riots began with the destruction of threshing machines in the Elham Valley area of East Kent in the summer of 1830 and by early December had spread through the whole of southern England

Southern England, also known as the South of England or the South, is a sub-national part of England. Officially, it is made up of the southern, south-western and part of the eastern parts of England, consisting of the statistical regions of ...

and East Anglia

East Anglia is an area of the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, with parts of Essex sometimes also included.

The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, ...

. It was to be the largest movement of social unrest in 19th-century England.

As well as attacking the popularly-hated threshing machines, which displaced workers, the protesters rioted over low wages and required tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Modern tithes are normally voluntary and paid in money, cash, cheques or v ...

s by destroying workhouse

In Britain and Ireland, a workhouse (, lit. "poor-house") was a total institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. In Scotland, they were usually known as Scottish poorhouse, poorh ...

s and tithe barn

A tithe barn was a type of barn used in much of northern Europe in the Middle Ages for storing rents and tithes. Farmers were required to give one-tenth of their produce to the established church. Tithe barns were usually associated with the ...

s associated with their oppression. They also burned ricks and maimed cows.

The rioters directed their anger at the three targets identified as causing their misery: the tithe system, requiring payments to support the established Anglican Church; the Poor Law

In English and British history, poor relief refers to government and ecclesiastical action to relieve poverty. Over the centuries, various authorities have needed to decide whose poverty deserves relief and also who should bear the cost of hel ...

guardians, who were thought to abuse their power over the poor; and the rich tenant farmer

A tenant farmer is a farmer or farmworker who resides and works on land owned by a landlord, while tenant farming is an agricultural production system in which landowners contribute their land and often a measure of operating capital and ma ...

s, who had been progressively lowering workers' wages and introduced agricultural machinery

Agricultural machinery relates to the machine (mechanical), mechanical structures and devices used in farming or other agriculture. There are list of agricultural machinery, many types of such equipment, from hand tools and power tools to tractor ...

. If captured, the protesters faced charges of arson

Arson is the act of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, watercr ...

, robbery, riot, machine-breaking and assault. Those convicted faced imprisonment, transportation

Transport (in British English) or transportation (in American English) is the intentional Motion, movement of humans, animals, and cargo, goods from one location to another. Mode of transport, Modes of transport include aviation, air, land tr ...

and possibly execution

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in ...

.Andrew Charlesworth, Brian Short and Roger Wells. "Riots and Unrest", in Kim Leslie, ''An Historical Atlas of Sussex'', pp. 74–75

The Swing Riots had many immediate causes. The historian J. F. C. Harrison believed that they were overwhelmingly the result of the progressive impoverishment and dispossession of the English agricultural workforce over the previous fifty years leading up to 1830. In Parliament, Lord Carnarvon had said that the English labourers were reduced to a plight more abject than that of any race in Europe, with their employers no longer able to feed and employ them.Hammond. ''The Village Labourer 1760–1832''. Ch XI. "The Last Labourers' Revolt"Hansard. ''House of Lords'' Debate 22 November 1830, vol 1 Column. 617 A 2020 study found that the presence of threshing machines caused greater rioting and that the severity of the riots was lowest in areas with abundant employment alternatives and the highest in areas with few alternative employment opportunities.

Name and etymology

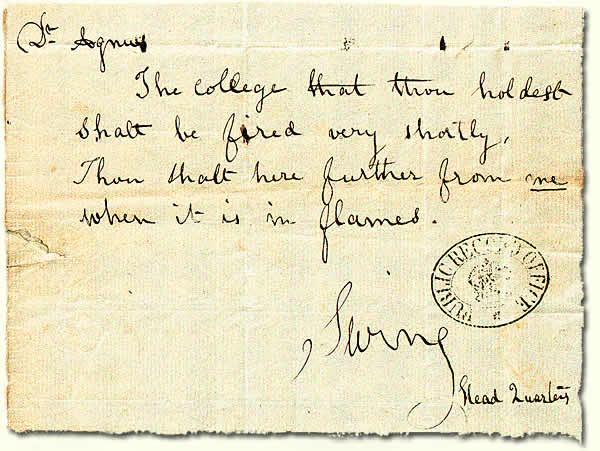

The name "Swing Riots" was derived from Captain Swing, the name attributed to the fictitious, mythical figurehead of the movement.Horspool. ''The English Rebel''. pp.339–340 The name was often used to sign threatening letters sent to farmers,magistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judi ...

s, parson

A parson is an ordained Christian person responsible for a small area, typically a parish. The term was formerly often used for some Anglican clergy and, more rarely, for ordained ministers in some other churches. It is no longer a formal term d ...

s and others. These were first mentioned by ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' on 21 October 1830.The Times, Thursday, 21 October 1830; p. 3; Issue 14363; col C

'Swing' was apparently a reference to the swinging stick of the flail used in hand threshing.

Background

Enclosure

Early 19th-century England was almost unique among major nations in having no class of landedsmallholding

A smallholding or smallholder is a small farm operating under a small-scale agriculture model. Definitions vary widely for what constitutes a smallholder or small-scale farm, including factors such as size, food production technique or technolo ...

peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasan ...

ry.Coffin. The Dorset Page. "Captain Swing in Dorset". The inclosure act

The inclosure acts created legal property rights to land previously held in common in England and Wales, particularly open fields and common land. Between 1604 and 1914 over 5,200 individual acts enclosing public land were passed, affecting 28,0 ...

s of rural England contributed to the plight of rural farmworkers. Between 1770 and 1830, about of common land were enclosed. The common land had been used for centuries by the poor of the countryside to graze their animals and grow their own produce. The land was now divided up among the large local landowners, leaving the landless farmworkers solely dependent upon working for their richer neighbours for a cash wage.Hammond. ''The Agricultural Labourer 1760–1832''. Chapter III "Enclosure" That may have offered a tolerable living during the boom years of the Napoleonic Era

The Napoleonic era is a period in the history of France and history of Europe, Europe. It is generally classified as including the fourth and final stage of the French Revolution, the first being the National Assembly (French Revoluti ...

, when labour had been in short supply and corn prices high, the return of peace in 1815 resulted in plummeting grain prices and an oversupply of labour. According to the social historians John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

and Barbara Hammond, enclosure was fatal to three classes: the small farmer, the cottager and the squatter.Hammond. ''The Village Labourer, 1760–1832''. p. 97Elmes. Architectural Jurisprudence. Title LXVI. pp. 178–179. Definition of a cottage is a small house for habitation without land. Under an Elizabeth I statute, they had to be built with at least of land. Thus, a cottager is someone who lives in a cottage with a smallholding of land Before enclosure

Enclosure or inclosure is a term, used in English landownership, that refers to the appropriation of "waste" or "common land", enclosing it, and by doing so depriving commoners of their traditional rights of access and usage. Agreements to enc ...

, the cottager was a labourer with land; after enclosure, he was a labourer without land.Hammond. ''The Village Labourer'', 1760–1832. p. 100

In contrast to the Hammonds' 1911 analysis of the events, the historian G. E. Mingay noted that when the Swing Riots broke out in 1830, the heavily-enclosed Midlands remained almost entirely quiet, but the riots were concentrated in the southern and south-eastern counties, which were little affected by enclosure. Some historians have posited that the reason was that in the West Midlands, for example, the rapid expansion of the Potteries and the coal and iron industries provided an alternative range of employment to agricultural workers.

Critically, J. D. Chambers and G. E. Mingay suggested that the Hammonds exaggerated the costs of change, but enclosure really meant more food for the growing population; more land under cultivation and, on the balance, more employment in the countryside. The modern historians of the riots, Eric Hobsbawm

Eric John Ernest Hobsbawm (; 9 June 1917 – 1 October 2012) was a British historian of the rise of industrial capitalism, socialism and nationalism. His best-known works include his tetralogy about what he called the "long 19th century" (''Th ...

and George Rudé

George Frederick Elliot Rudé (8 February 1910 – 8 January 1993) was a British Marxist historian, specializing in the French Revolution and " history from below", especially the importance of crowds in history.George Rudé (1964). ''The Crow ...

, cited only three of a total of 1,475 incidents as being directly caused by enclosure. Since the late 20th century, those contentions have been challenged by a new class of recent historians. Enclosure has been seen by some as causing the destruction of the traditional peasant way of life, however miserable:

Landless peasants could no longer maintain an economic independence and so had to become labourers. Surplus peasant labour moved into the towns to become industrial workers.

Precarious employment

In the 1780s, workers would be employed at annual hiring fairs, or ‘mops’, to serve for the whole year. During that period, the worker would receive payment in kind and in cash from his employer, would often work at his side, and would commonly share meals at the employer's table. As time passed, the gulf between farmer and employee widened. Workers were hired on stricter cash-only contracts, which ran for increasingly shorter periods. First, monthly terms became the norm. Later, contracts were offered for as little as a week.Hobsbawm/Rude. Captain Swing. pp. 18–33 Between 1750 and 1850, farm labourers faced the loss of their land, the transformation of their contracts and the sharp deterioration of their economic situations. By the time of the 1830 riots, they had retained very little of their former status except the right to parish relief, under the Old Poor Law system.Hobsbawm/Rude. Captain Swing. pp. xxi–xxii Additionally, there was an influx of Irish farm labourers in 1829, who had come to seek agricultural work which contributed to reduced employment opportunities for other farming communities. Irish labourers would find themselves being threatened from the beginning of the riots the following year.Poor Laws

Historically, the monasteries had taken responsibility for the impotent poor, but after their dissolution in 1536 to 1539, responsibility passed to the parishes.Friar. ''Sutton Local History''. pp. 324–325 the Act of Settlement in 1662 had confined relief strictly to those who were natives of the parish. The poor law system charged a Parish Rate to landowners and tenants, which was used to provide relief payments to settled residents of the parish who were ill or out of work.Hobsbawm/Rude. Captain Swing. p. 29 The payments were minimal, and at times, degrading conditions were required for their receipt. As more and more people became dependent on parish relief, ratepayers rebelled ever more loudly against the costs, and lower and lower levels of relief were offered. Three "one-gallon" bread loaves a week were considered necessary for a man inBerkshire

Berkshire ( ; abbreviated ), officially the Royal County of Berkshire, is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Oxfordshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the north-east, Greater London ...

in 1795. However provision had fallen to just two similarly-sized loaves being provided in 1817 Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated to Wilts) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It borders Gloucestershire to the north, Oxfordshire to the north-east, Berkshire to the east, Hampshire to the south-east, Dorset to the south, and Somerset to ...

.Hammonds. ''The Village Labourer''. pp. 183–185 The way in which poor law funds were disbursed led to a further reduction in agricultural wages since farmers would pay their workers as little as possible in the knowledge that the parish fund would top up wages to a basic subsistence level (see Speenhamland system

The Speenhamland system was a form of outdoor relief intended to mitigate rural poverty in England and Wales at the end of the 18th century and during the early 19th century. The law was an amendment to the Elizabethan Poor Law (the Poor Relief A ...

).Friar. Sutton Companion to Local History. pp. 324–325

Tithe System

To that mixture was added the burden of the church tithe. This was the church's right to a tenth of the parish harvest.Hobsbawm/Rude. Captain Swing. pp. 14–15 The tithe-owner could voluntarily reduce the financial burden on the parish either by allowing the parish to keep more of their share of the harvest. Or the tithe-owner could, again voluntarily, commute the tithe payments to a rental charge. The rioters had demanded that tithes should be reduced, but this demand was refused by many of the tithe-owners.Industrialisation

The final straw was the introduction of horse-powered threshing machines, which could do the work of many men.Hobsbawm/Rude. Captain Swing. Appendix IV They spread swiftly among the farming community and threatened the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands of farmworkers. Following the terrible harvests of 1828 and 1829, farm labourers faced the approaching winter of 1830 with dread.Riots

Starting in the south-eastern county of

Starting in the south-eastern county of Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

, the Swing Rioters smashed the threshing machines and threatened farmers who owned them.Hobsbawm/Rude. Captain Swing. p. 71 The first threshing machine to be destroyed was during Saturday night, 28 August 1830 at Lower Hardres. By the third week of October, more than 100 threshing machines had been destroyed in East Kent. The riots spread rapidly and systematically - following pre-existing road networks - through the southern counties of Surrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

, Sussex, Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, former county in South East England, now mainly within Greater London. Its boundaries largely followed three rivers: the River Thames, Thames in the south, the River Lea, Le ...

and Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Berkshire to the north, Surrey and West Sussex to the east, the Isle of Wight across the Solent to the south, ...

before they spread north into the Home Counties, the Midlands

The Midlands is the central region of England, to the south of Northern England, to the north of southern England, to the east of Wales, and to the west of the North Sea. The Midlands comprises the ceremonial counties of Derbyshire, Herefor ...

and East Anglia

East Anglia is an area of the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, with parts of Essex sometimes also included.

The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, ...

. Originally, the disturbances were thought to be mainly a southern and East Anglian phenomenon, but subsequent research has revealed just how widespread Swing riots really were, with almost every county south of the Scottish border involved.

In all, sixty percent of the disturbances were concentrated in the south (Berkshire 165 incidents, Hampshire 208, Kent 154, Sussex 145, Wiltshire 208); East Anglia had fewer incidents (Cambridge 17, Norfolk 88, Suffolk 40); and the Southwest, the Midlands and the North were only marginally affected.Armstrong. Farmworkers: A Social and Economic History, 1770–1980. p. 75 and Table 3.1

Tactics

The tactics varied from county to county, but typically, threatening letters, often signed by Captain Swing, would be sent to magistrates, parsons, wealthy farmers or Poor Law guardians in the area.Hobsbawm/Rude. Captain Swing. Ch. 10 The letters would call for a rise in wages, a cut in thetithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Modern tithes are normally voluntary and paid in money, cash, cheques or v ...

payments and the destruction of threshing machines, or people would take matters into their own hands. If the warnings were not heeded local farm workers would gather, often in groups of 200 to 400, and would threaten the local oligarchs with dire consequences if their demands were not met. Threshing machines would be broken, workhouses and tithe barns would be attacked and the rioters would then disperse or move on to the next village. The buildings containing the engines that powered the threshing machines were also a target of the rioters and many gin gangs, also known as horse engine houses or wheelhouses, were destroyed, particularly in south−eastern England.Hutton. The distribution of wheelhouses in Britain. pp. 30–35 There are also recorded instances of carriages being held up and their occupants robbed.

Other actions included incendiary attacks on farms, barns and hayricks in the dead of night, when it was easier to avoid detection. Although many of the actions of the rioters, such as arson, were conducted in secret at night, meetings with farmers and overseers about the grievances were conducted in daylight.

Despite the prevalence of the slogan "Bread or Blood", only one person is recorded as having been killed during the riots, which was one of the rioters by the action of a soldier or farmer. The rioters' only intent was to damage property.

Similar patterns of disturbances and their rapid spread across the country were often blamed on agitators or on "agents" sent from France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, where the revolution of July 1830 had broken out a month before the Swing Riots had begun in Kent.Smith. ''One Monday in November... And Beyond''. p.16.

Despite all of the different tactics used by the agricultural workers during the unrest, their principal aims were simply to attain a minimum living wage and to end rural unemployment.

A 2021 study that examined how information and diffusion shaped the riots found "that information about the riots traveled through personal and trade networks but not through transport or mass media networks. This information was not about repression, and local organizers played an important role in the diffusion of the riots".

Aftermath

Trials

The authorities felt severely threatened by the riots and responded with harsh punitive measures. Nearly 2,000 protesters were brought to trial in 1830–1831; 252 were sentenced to death (though only 19 were actually hanged), 644 were imprisoned and 481 were transported to penal colonies in Australia.Brian T. RobsonThe Saviour City: Beneficial effects of urbanization in England and Wales

''in'' Douglas. Companion Encyclopedia of Geography: The Environment and Humankind. p. 297 Not all rioters were farm workers since the list of those punished included rural artisans, shoemakers, carpenters, wheelwrights, blacksmiths and cobblers. One of those hanged was reported to have been charged only because he had knocked the hat off the head of a member of the Baring banking family. Many of the protesters who were transported had their sentences remitted in 1835.

Social, economic and political reform

Eventually, the farmers agreed to raise wages, and the parsons and some landlords reduced the tithes and rents. However, many farmers reneged on the agreements, and the unrest increased.

Many people advocated political reform as the only solution to the unrest, one of them being the radical politician and writer

Eventually, the farmers agreed to raise wages, and the parsons and some landlords reduced the tithes and rents. However, many farmers reneged on the agreements, and the unrest increased.

Many people advocated political reform as the only solution to the unrest, one of them being the radical politician and writer William Cobbett

William Cobbett (9 March 1763 – 18 June 1835) was an English pamphleteer, journalist, politician, and farmer born in Farnham, Surrey. He was one of an Agrarianism, agrarian faction seeking to reform Parliament, abolish "rotten boroughs", restr ...

. The authorities had received many requests to prosecute him for the speeches that he had made in defence of the rural labourer, but it was for his articles in the '' Political Register'' that he was eventually charged with seditious libel.Hansard.COBBETT'S REGISTER— INFLAMMATORY PUBLICATIONS, Debate.HC Deb 23 December 1830 vol 2 cc71-81 He wrote an article, ''The Rural War'', about the Swing Riots. He blamed those in society who lived off unearned income

Unearned income is a term coined by Henry George to refer to income gained through ownership of land and other monopoly. Today the term often refers to income received by virtue of owning property (known as property income), inheritance, pensio ...

at the expense of hard-working agricultural labourers; his solution was parliamentary reform.Dyck. William Cobbett and Rural Popular Culture. Ch. 7Cobbet. "The Rural War" in ''Cobbett's Political Register''. Vol. 37. During his trial in July 1831 at the Guildhall, he subpoena

A subpoena (; also subpœna, supenna or subpena) or witness summons is a writ issued by a government agency, most often a court, to compel testimony by a witness or production of evidence under a penalty for failure. There are two common types of ...

ed six members of the cabinet, including the prime minister. Cobbett defended himself by going on the attack. He tried to ask the government ministers awkward questions supporting his case, but they were disallowed by the Lord Chief Justice. However, he was able to discredit the prosecution's case, and at great embarrassment to the government, he was acquitted.

A major concern was that the Swing Riots could spark a larger revolt. That was reinforced by the 29 July 1830 revolution in France, which overthrew Charles X Charles X may refer to:

* Charles X of France (1757–1836)

* Charles X Gustav (1622–1660), King of Sweden

* Charles, Cardinal de Bourbon (1523–1590), recognized as Charles X of France but renounced the royal title

See also

*

* King Charle ...

, and the independence of Belgium from the Netherlands later in 1830. The support for parliamentary reform was on party lines, with the Tories against reform and the Whigs having proposed changes well before the Swing riots. The farm labourers who were involved in the disturbances did not have a vote, but it is probable that the largely landowning classes, who could vote, were influenced by the Swing Riots to support reform.Aidt and Franck. Democratization. pp. 505–547

Earl Grey, during a House of Lords debate in November 1830, suggested the best way to reduce the violence was to introduce reform of the House of Commons.Hansard. ADDRESS IS ANSWER TO THE SPEECH. Debate 2 November 1830 vol 1 cc37-38 The Tory Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they ar ...

, replied that the existing constitution was so perfect that he could not imagine any possible alternative that would be an improvement.Hansard. ADDRESS IS ANSWER TO THE SPEECH. Debate 2 November 1830 vol 1 cc52-53 When that was reported, a mob attacked Wellington's home in London.Gash, 'Wellesley, Arthur, first duke of Wellington (1769–1852)' The unrest had been confined to Kent, but during the following two weeks of November, it escalated massively by crossing East and West Sussex into Hampshire, with Swing letters appearing in other nearby counties.Charlesworth.'Social protest in a rural society'. p. 35

On 15 November 1830, Wellington's government was defeated by a vote in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

. Two days later, Earl Grey was asked to form a Whig government.Mandler, 'Lamb, William, second Viscount Melbourne (1779–1848)' Grey assigned a cabinet committee to produce a plan for parliamentary reform. Lord Melbourne became Home Secretary in the new government. He blamed local magistrates for being too lenient, and the government appointed a Special Commission of three judges to try rioters in the counties of Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Dorset, Wiltshire and Hampshire.

Acts of Parliament

The riots were a major influence on the Whig government. They added to the strong social, political and agricultural unrest throughout Britain in the 1830s, encouraging a wider demand for political reform, culminating in the introduction of theGreat Reform Act 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the Reform Act 1832, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. 4. c. 45), enacted by the Whig government of Pri ...

. The act was the first of several reforms that over the course of a century transformed the British political system from one based on privilege and corruption to one based on universal suffrage

Universal suffrage or universal franchise ensures the right to vote for as many people bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the " one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion ...

and the secret ballot. In domestic elections before the Great Reform Act 1832, only about three per cent of the English population could vote. Most constituencies had been founded in the Middle Ages and so the newly-industrial northern England had virtually no representation. Those who could vote were mainly the large landowners and wealthy commoners.

The Great Reform Act 1832 was followed by the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834

The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 (4 & 5 Will. 4. c. 76) (PLAA) known widely as the New Poor Law, was an Act of Parliament (United Kingdom), act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed by the British Whig Party, Whig government of Charles ...

, ending "outdoor relief" in cash or kind and setting up a chain of designedly unwholesome workhouse

In Britain and Ireland, a workhouse (, lit. "poor-house") was a total institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. In Scotland, they were usually known as Scottish poorhouse, poorh ...

s covering larger areas across the country to which the poor had to go if they wanted help.Green. ''Pauper London'' p.13

See also

*British Agricultural Revolution

The British Agricultural Revolution, or Second Agricultural Revolution, was an unprecedented increase in agricultural production in Britain arising from increases in labor and land productivity between the mid-17th and late 19th centuries. Agricu ...

* Ely and Littleport riots of 1816

* Luddite

The Luddites were members of a 19th-century movement of English textile workers who opposed the use of certain types of automated machinery due to concerns relating to worker pay and output quality. They often destroyed the machines in organ ...

* Rebecca Riots

The Rebecca Riots () took place between 1839 and 1843 in West and Mid Wales. They were a series of protests undertaken by local farmers and agricultural workers in response to levels of taxation. The rioters, often men dressed as women, took ...

* Tolpuddle Martyrs

The Tolpuddle Martyrs were six agricultural labourers from the village of Tolpuddle in Dorset, England, who were arrested and tried in 1834 for swearing a secret oath as members of a friendly society. Led by George Loveless, the group had ...

* William Winterbourne

Notes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

John Owen Smith, "Headley & Selborne workhouse riot of 1830"

*Captain Swing Reconsidered. Papers published in ''Southern History'' vol.32 (201

{{Authority control 1830 riots 1830 in England English Poor Laws Riots and civil disorder in England History of agriculture in England William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington