Swing Around The Circle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Swing Around the Circle is the nickname for a speaking campaign undertaken by

By the time he returned to Washington from the speaking tour, Johnson had even less support in the North than he had started with. His only remaining allies in Congress were Southern Democrats; since these were mostly former rebels, Johnson's reputation was diminished yet further by association. The Republican party would go on to a landslide victory in the congressional elections, and the new Congress would wrest control of Reconstruction from the

By the time he returned to Washington from the speaking tour, Johnson had even less support in the North than he had started with. His only remaining allies in Congress were Southern Democrats; since these were mostly former rebels, Johnson's reputation was diminished yet further by association. The Republican party would go on to a landslide victory in the congressional elections, and the new Congress would wrest control of Reconstruction from the

United States President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United State ...

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

between August 27 and September 15, 1866, in which he tried to gain support for his mild Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

policies and for his preferred candidates (mostly Democrats) in the forthcoming midterm Congressional elections. The tour's nickname came from the route that the campaign took: "Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, to New York, west to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, south to St. Louis, and east through the Ohio River valley back to the nation's capital".

Johnson undertook the speaking tour in the face of increasing opposition in the Northern United States

The Northern United States, commonly referred to as the American North, the Northern States, or simply the North, is a geographical or historical region of the United States.

History Early history

Before the 19th century westward expansion, the "N ...

and in Washington to his lenient form of Reconstruction in the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

, which had led the Southern states largely to revert to the social system that had predominated before the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. Although he believed he could regain the trust of moderate Northern Republicans by exploiting tensions between them and their Radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

counterparts on the tour, Johnson only alienated them more. This caused a supporter of Johnson to say of the tour that it would have been better "had it never been made." The tour eventually became the centerpiece of the tenth article of impeachment against Johnson.

Background

Johnson had first intended his approach to Reconstruction as a delivery of predecessorAbraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

's promise to benevolently "bind up the nation's wounds" after the war was won. However, as Congress began enacting legislation to guarantee the rights of former slaves, former slaveowner Johnson refocused on actions (including vetoes of civil rights legislation and mass pardoning of former Confederate officials) that resulted in severe oppression of freed slaves in the Southern states, as well as the return of high-ranking Confederate officials and pre-war aristocrats to power in state and federal government. The policies had infuriated the Radical Republicans in Congress and gradually alienated the moderates, who along with Democrats had been Johnson's base of congressional support, to the point that by 1866 the Congress had gathered enough antipathy towards the President to enact the first override of a Presidential veto in over twenty years, salvaging a bill that extended the life of the Freedmen's Bureau

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, usually referred to as simply the Freedmen's Bureau, was an agency of early Reconstruction, assisting freedmen in the South. It was established on March 3, 1865, and operated briefly as a ...

. Johnson also managed to alienate his own cabinet, three members of which resigned in disgust in 1866.

Thus the elections that year were viewed as a referendum on Johnson himself, who had not been elected President but had acceded to power upon Lincoln's murder. However, in Johnson's earlier political campaigns he had earned a reputation as a masterful stump speaker, and to that end he determined to undertake a political speaking tour (which at that time was unprecedented for a sitting President). His two dedicated supporters in the cabinet, Secretary of State William Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

and Navy Secretary

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the s ...

Gideon Welles

Gideon Welles (July 1, 1802 – February 11, 1878), nicknamed "Father Neptune", was the United States Secretary of the Navy from 1861 to 1869, a cabinet post he was awarded after supporting Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election. Although opposed ...

, joined him on the tour. In addition, to increase both his audience and his prestige, Johnson brought along heroes of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

such as David Farragut

David Glasgow Farragut (; also spelled Glascoe; July 5, 1801 – August 14, 1870) was a flag officer of the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He was the first rear admiral, vice admiral, and admiral in the United States Navy. Fa ...

, George Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his class, b ...

, and Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

(by then the most admired living man in the country) to stand next to him while he spoke.

The tour

Initial success

In the 18 days of the tour, Johnson and his entourage made stops inBaltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

; New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

, Albany, Auburn

Auburn may refer to:

Places Australia

* Auburn, New South Wales

* City of Auburn, the local government area

*Electoral district of Auburn

*Auburn, Queensland, a locality in the Western Downs Region

*Auburn, South Australia

*Auburn, Tasmania

*Aub ...

, Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls () is a group of three waterfalls at the southern end of Niagara Gorge, spanning the border between the province of Ontario in Canada and the state of New York in the United States. The largest of the three is Horseshoe Falls, ...

, and Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from South ...

; Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

and Toledo, Ohio

Toledo ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Lucas County, Ohio, United States. A major Midwestern United States port city, Toledo is the fourth-most populous city in the state of Ohio, after Columbus, Cleveland, and Cincinnati, and according ...

; Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at th ...

, Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

; Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, Springfield

Springfield may refer to:

* Springfield (toponym), the place name in general

Places and locations Australia

* Springfield, New South Wales (Central Coast)

* Springfield, New South Wales (Snowy Monaro Regional Council)

* Springfield, Queenslan ...

, and Alton, Illinois

Alton ( ) is a city on the Mississippi River in Madison County, Illinois, United States, about north of St. Louis, Missouri. The population was 25,676 at the 2020 census. It is a part of the River Bend area in the Metro-East region of the ...

; St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

; Indianapolis, Indiana

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Mari ...

; Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border ...

; Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

and Columbus, Ohio

Columbus () is the state capital and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Ohio. With a 2020 census population of 905,748, it is the 14th-most populous city in the U.S., the second-most populous city in the Midwest, after Chicago, and t ...

; and Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

Harrisburg is the capital city of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Dauphin County. With a population of 50,135 as of the 2021 census, Harrisburg is the 9th largest city and 15th largest municipality in Pe ...

, as well as short stops in smaller towns between.

Because Presidents had traditionally not undertaken political campaigning in the past, Johnson's action was seen even before he began as undignified and beneath the office. Johnson's advisors, aware that the President could get carried away in his own sentiments, pleaded with him to give only carefully prepared speeches; Johnson, as he had often done on the campaign trail, instead prepared a rough outline around which he could spontaneously speak.

Initially, Johnson was enthusiastically received, particularly in Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York. According to Johnson biographer Hans Trefousse, at each stop on the tour he had delivered

The press nonetheless gave him overwhelmingly positive coverage throughout the first leg of the tour (although the circumstances made his customary introduction—"Fellow citizens, it is not for the purpose of making speeches that I now appear before you"—a particular laugh line). However, when Johnson entered the Radical Republican strongholds of the Midwest, he began facing much more hostile crowds, some drawn by reports of his prior speeches and others organized by Republican leadership in those towns.

Disaster

Johnson's stop in Cleveland on September 3 marked the turning point in the tour. Because the audience was as large as it had been at previous stops, nothing seemed out of the ordinary; however, the crowd included mobs of hecklers, many of them plants by the Radical Republicans, who goaded Johnson into engaging them in mid-speech; when one of them yelled "Hang Jeff Davis!" in Cleveland, Johnson angrily replied, "Why don't you hang Thad Stevens andWendell Phillips

Wendell Phillips (November 29, 1811 – February 2, 1884) was an American abolitionist, advocate for Native Americans, orator, and attorney.

According to George Lewis Ruffin, a Black attorney, Phillips was seen by many Blacks as "the one whi ...

?" When he left the balcony from which he had spoken, reporters heard supporters reminding Johnson to maintain his dignity; Johnson's reply of "I don't care about my dignity" was carried in newspapers across the nation, abruptly ending the tour's favorable press.

Subsequent to this and other vituperative appearances in southern Michigan, the Illinois governor Richard J. Oglesby refused to attend Johnson's September 7 Chicago stop, as did the Chicago city council. Johnson nonetheless fared well in Chicago, presenting only a short and pre-written speech. However, his temper got the better of him once more in St. Louis on September 9. Provoked by a heckler, Johnson accused Radical Republicans of deliberately inciting the deadly New Orleans Riot

The New Orleans Massacre of 1866 occurred on July 30, when a peaceful demonstration of mostly Black Freedmen was set upon by a mob of white rioters, many of whom had been soldiers of the recently defeated Confederate States of America, leading t ...

that summer; again compared himself to Jesus, and the Republicans to his betrayers; and defending himself against unmade accusations of tyranny. The following day in Indianapolis, the crowd was so hostile and loud that Johnson was unable to speak at all; even after he retreated, violence and gunfire broke out in the streets between Johnson supporters and opponents, resulting in one man's death.

At other points in Kentucky, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, spectators drowned out Johnson with calls for Grant, who refused to speak, and for "Three cheers for Congress!"

Tragedy

Finally, on September 14 inJohnstown, Pennsylvania

Johnstown is a city in Cambria County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 18,411 as of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census. Located east of Pittsburgh, Johnstown is the principal city of the Johnstown, Pennsylvania, Metropol ...

, a temporary platform built beside the railroad tracks for the president's appearance gave way, sending hundreds into a drained canal 20 feet below, killing thirteen. Though Johnson attempted to halt the train and use it for triage for the injured, it could not wait due to conflicting train traffic. A few members of the presidential party left the train to assist the victims, but Johnson and the rest of the party continued onto Harrisburg

Harrisburg is the capital city of the Pennsylvania, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, Dauphin County. With a population of 50,135 as of the 2021 census, Harrisburg is the List of c ...

. To appearances, Johnson had callously abandoned the scene of massive casualties. Johnson gave $500 ($8,318 in 2016 dollars) to assist the victims.

Reaction

The press excoriated Johnson badly for his disastrous appearances and speeches. The ''New York Herald

The ''New York Herald'' was a large-distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between 1835 and 1924. At that point it was acquired by its smaller rival the ''New-York Tribune'' to form the '' New York Herald Tribune''.

His ...

'', previously the most supportive newspaper for Johnson in the entire country, stated that "It is mortifying to see a man occupying the lofty position of President of the United States descend from that position and join issue with those who are draggling their garments in the muddy gutters of political vituperation." The president was also the target of the two most important satirical journalists of the era—humorist David Ross Locke

David Ross Locke (also known by his pseudonym Petroleum V. Nasby) (September 20, 1833February 15, 1888) was an American journalist and early political commentator during and after the American Civil War.

Biography

Early life

Locke was born i ...

(writing in his persona as the backward southerner Petroleum Vesuvius Nasby

David Ross Locke (also known by his pseudonym Petroleum V. Nasby) (September 20, 1833February 15, 1888) was an American journalist and early political commentator during and after the American Civil War.

Biography

Early life

Locke was born i ...

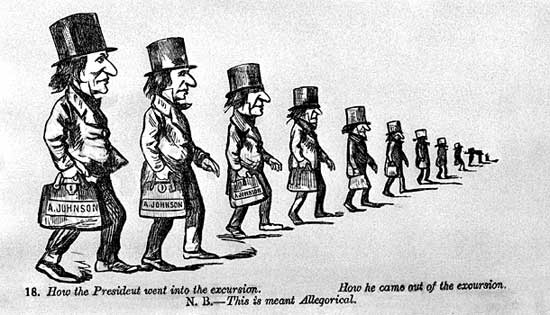

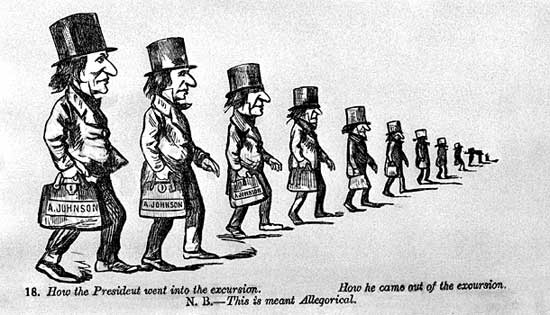

) and cartoonist Thomas Nast

Thomas Nast (; ; September 26, 1840December 7, 1902) was a German-born American caricaturist and editorial cartoonist often considered to be the "Father of the American Cartoon".

He was a critic of Democratic Party (United States), Democratic U ...

, who created three large illustrations lampooning Johnson and the Swing that became legendary.

Johnson's Republican opponents took quick advantage of their good political fortune. Thaddeus Stevens gave a speech referring to the Swing as "the remarkable circus that traveled through the country" that "cut outside the circle and entered into street brawls with common blackguards." Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

, meanwhile, gave a stump speech of his own, encouraging his audiences to vote for Republicans in the fall elections because "the President must be taught that usurpation and apostasy cannot prevail."

Radical Republicans also began spreading rumors that Johnson had been drunk at several appearances. Because Johnson had been visibly and verifiably drunk at his own inauguration as vice president the year before, reporters and political opponents took his inebriation as fact and declared him a "vulgar, drunken demagogue who was disgracing the presidency."

Johnson's supporters, too, gave negative reactions to the tour, with former Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

Governor Herschel V. Johnson

Herschel Vespasian Johnson (September 18, 1812August 16, 1880) was an American politician. He was the 41st Governor of Georgia from 1853 to 1857 and the vice presidential nominee of the Douglas wing of the Democratic Party in the 1860 U.S. pre ...

writing that the President had " acrificedthe moral power of his position, and done great damage to the cause of Constitutional Reorganization." James Doolittle, a Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

from Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, lamented that the tour had "cost Johnson one million northern voters."

Aftermath

By the time he returned to Washington from the speaking tour, Johnson had even less support in the North than he had started with. His only remaining allies in Congress were Southern Democrats; since these were mostly former rebels, Johnson's reputation was diminished yet further by association. The Republican party would go on to a landslide victory in the congressional elections, and the new Congress would wrest control of Reconstruction from the

By the time he returned to Washington from the speaking tour, Johnson had even less support in the North than he had started with. His only remaining allies in Congress were Southern Democrats; since these were mostly former rebels, Johnson's reputation was diminished yet further by association. The Republican party would go on to a landslide victory in the congressional elections, and the new Congress would wrest control of Reconstruction from the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

with the Reconstruction Acts

The Reconstruction Acts, or the Military Reconstruction Acts, (March 2, 1867, 14 Stat. 428-430, c.153; March 23, 1867, 15 Stat. 2-5, c.6; July 19, 1867, 15 Stat. 14-16, c.30; and March 11, 1868, 15 Stat. 41, c.25) were four statutes passed duri ...

of 1867.

Johnson openly defied Congress and fought them bitterly for the control of the nation's domestic policy. However, the Republicans' vastly increased congressional voting bloc not only afforded them the political power to keep Johnson at bay, it gave the party sufficient votes to attempt impeachment

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

of Johnson, first unsuccessfully in 1867 and again successfully in 1868. The Swing Around the Circle's impact was apparent even in the articles of impeachment, with the tenth of eleven articles charging that the President "did...make and declare, with a loud voice certain intemperate, inflammatory, and scandalous harangues, and therein utter loud threats and bitter menaces, as well against Congress as the laws of the United States duly enacted thereby, amid the cries, jeers and laughter of the multitudes then assembled in hearing." The article was specifically seen as being in response to speeches delivered in Washington on August 18, Cleveland on September 3, and St. Louis on September 8, 1866. During the impeachment trial, a number of reporters and other individuals were called on April 3 and 4, during the prosecution's presentation, to testify about speeches Johnson had made, including one in Washington, D.C. on August 18, 1866 (shortly before the commencement of the Swing Around the Circle) and in Cleveland, Ohio on September 3, 1866 (during the Swing Around the Circle). The impeachment managers neglected to bring the tenth article to a vote in the Senate when it became clear that it had insufficient support to result in a conviction.

The Republicans captured the White House in 1868

Events

January–March

* January 2 – British Expedition to Abyssinia: Robert Napier leads an expedition to free captive British officials and missionaries.

* January 3 – The 15-year-old Mutsuhito, Emperor Meiji of Jap ...

and maintained control of it until 1885, although Congress would continue to be the dominant force in government until the end of the 19th century. Thus, in effect, the Swing Around the Circle began a long series of political defeats that crippled Johnson, the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

and the presidency for several years.

See also

*Presidency of Andrew Johnson

The presidency of Andrew Johnson began on April 15, 1865, when Andrew Johnson became President of the United States upon the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, and ended on March 4, 1869. He had been Vice President of the United States f ...

* Reconstruction Era

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

References

Bibliography

* Boulard, Garry ''The Swing Around the Circle: Andrew Johnson and the Train Ride That Destroyed a Presidency'' (iUniverse, 2008) * http://www.harpweek.com/09Cartoon/BrowseByDateCartoon.asp?Month=November&Date=3 * https://web.archive.org/web/20100208005118/http://kids.yahoo.com/reference/encyclopedia/entry?id=JohnsonAn * http://www.sewardhouse.org/house/ * http://www.nps.gov/anjo/historyculture/timeline.htm 1866 in American politics Presidency of Andrew Johnson Reconstruction Era {{Impeachment and impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson