Sverdlov (other) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

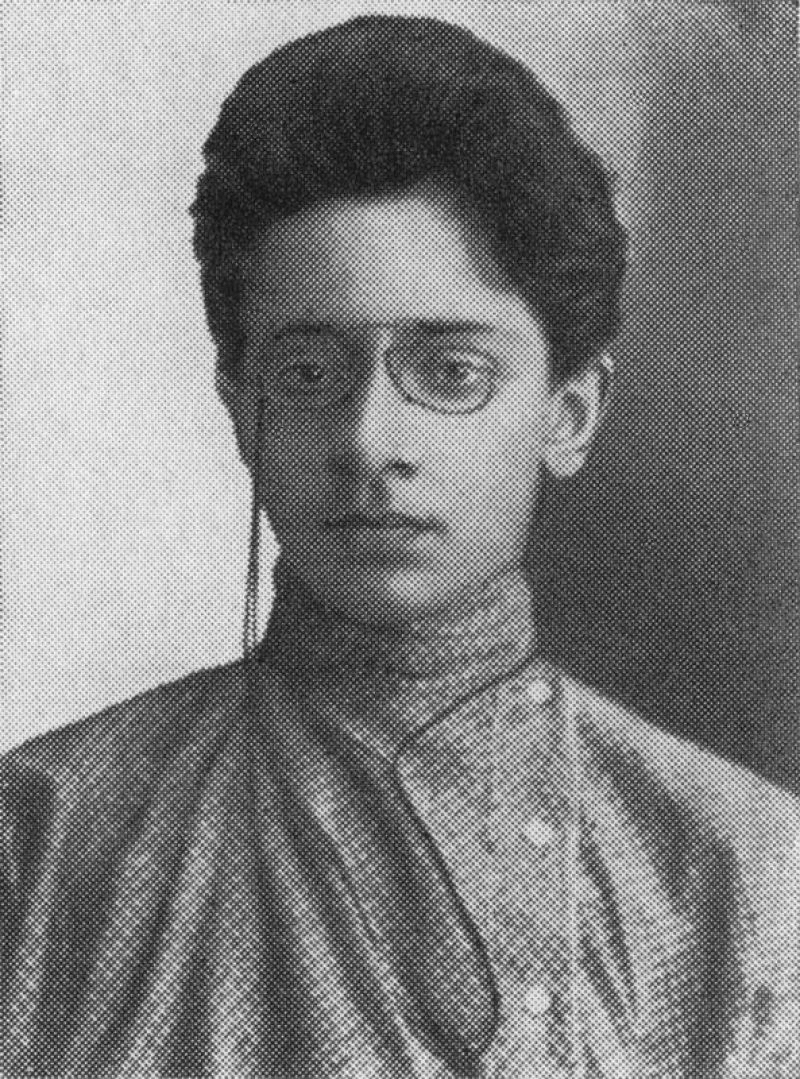

Yakov Mikhailovich Sverdlov (russian: Яков Михайлович Свердлов; 3 June O. S. 22 May">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 22 May 1885 – 16 March 1919) was a Bolshevik Party administrator and chairman of the

Sverdlov was born in

Sverdlov was born in

After the 1917

After the 1917

A book written in 1990 by the Moscow playwright

A book written in 1990 by the Moscow playwright

There are various theories on how he died and none can be proven officially such as poisoning, beating or flu. He is most commonly attributed to have died of either

There are various theories on how he died and none can be proven officially such as poisoning, beating or flu. He is most commonly attributed to have died of either

Leon Trotsky: Jacob Sverdlov – 1925 memorial essay

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Sverdlov, Yakov 1885 births 1919 deaths Politicians from Nizhny Novgorod Russian Jews Old Bolsheviks Russian communists People of the Russian Revolution People of the Russian Civil War Heads of state of Russia Communist rulers Soviet politicians Anti-monarchists Politicide perpetrators Regicides of Nicholas II Russian revolutionaries Heads of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union members People of the 1905 Russian Revolution Jewish socialists Jewish Soviet politicians Burials at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis Deaths from Spanish flu Infectious disease deaths in Russia

All-Russian Central Executive Committee

The All-Russian Central Executive Committee ( rus, Всероссийский Центральный Исполнительный Комитет, Vserossiysky Centralny Ispolnitelny Komitet, VTsIK) was the highest legislative, administrative and r ...

from 1917 to 1919. He is sometimes regarded as the first head of state of the Soviet Union, although it was not established until 1922, three years after his death.

Born in Nizhny Novgorod

Nizhny Novgorod ( ; rus, links=no, Нижний Новгород, a=Ru-Nizhny Novgorod.ogg, p=ˈnʲiʐnʲɪj ˈnovɡərət ), colloquially shortened to Nizhny, from the 13th to the 17th century Novgorod of the Lower Land, formerly known as Gork ...

to a Jewish family active in revolutionary politics, Sverdlov joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

in 1902 and supported Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

's Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

faction during an ideological split. He was active in the Urals

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through European ...

during the failed Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

, and in the next decade, he was subjected to constant imprisonment and exile. After the 1917 February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

overthrew the monarchy, Sverdlov returned to Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

and was appointed chairman of the Party Secretariat. In that capacity, he played a key role in planning of the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

.

Sverdlov was elected chairman of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee in November 1917. He worked to consolidate Bolshevik control of the new regime and supported the Red Terror

The Red Terror (russian: Красный террор, krasnyj terror) in Soviet Russia was a campaign of political repression and executions carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. It started in lat ...

campaign and the decossackization

De-Cossackization (Russian: Расказачивание, ''Raskazachivaniye'') was the Bolshevik policy of systematic repressions against Cossacks of the Russian Empire, especially of the Don and the Kuban, between 1919 and 1933 aimed at the el ...

policies. He is also considered to have played a major role in authorising the execution of the Romanov family

The Russian Imperial Romanov family (Nicholas II of Russia, his wife Alexandra Feodorovna, and their five children: Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia, and Alexei) were shot and bayoneted to death by Bolshevik revolutionaries under Yakov Yuro ...

in July 1918.

Sverdlov died in March 1919 during the Spanish flu

The 1918–1920 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case was ...

at the age of 33 and was buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis

The Kremlin Wall Necropolis was the national cemetery for the Soviet Union. Burials in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis in Moscow began in November 1917, when 240 pro-Bolshevik individuals who died during the Moscow Bolshevik Uprising were buried in m ...

. The city of Yekaterinburg

Yekaterinburg ( ; rus, Екатеринбург, p=jɪkətʲɪrʲɪnˈburk), alternatively romanized as Ekaterinburg and formerly known as Sverdlovsk ( rus, Свердло́вск, , svʲɪrˈdlofsk, 1924–1991), is a city and the administra ...

was renamed Sverdlovsk in 1924 in his honour.

Early life

Sverdlov was born in

Sverdlov was born in Nizhny Novgorod

Nizhny Novgorod ( ; rus, links=no, Нижний Новгород, a=Ru-Nizhny Novgorod.ogg, p=ˈnʲiʐnʲɪj ˈnovɡərət ), colloquially shortened to Nizhny, from the 13th to the 17th century Novgorod of the Lower Land, formerly known as Gork ...

as Yakov-Aaron Mikhailovich Sverdlov to Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

parents, Mikhail Izrailevich Sverdlov and Elizaveta Solomonova. His father was a politically active engraver who produced forged

Forging is a manufacturing process involving the shaping of metal using localized compressive forces. The blows are delivered with a hammer (often a power hammer) or a die. Forging is often classified according to the temperature at which it ...

documents and stored arms for the revolutionary underground. The Sverdlov family had six children: two daughters (Sophia and Sara) and four sons (Zinovy, Yakov, Veniamin, and Lev). After his wife's death in 1900, Mikhail converted with his family to the Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

, married Maria Aleksandrovna Kormiltseva, and had two more sons, Herman and Alexander. Sverdlov's father was sympathetic to his children's socialist tendencies and 5 out of his 6 children would become involved in revolutionary politics at some point. Mikhail watched as his household slowly became a revolutionary hotspot, where the Novgorod Social Democrats would meet, write pamphlets, and even forge stamps for false passports. Yakov's eldest brother Zinovy Zinovy or Zinovii (russian: Зиновий, Zinovij; uk, Зіновій, Zinovij) is a Russian and Ukrainian male given name, and may refer to:

* Bogdan Zinovy Mikhailovich Khmelnitsky (1595–1657), hetman of the Zaporozhian Cossack Hetmanate of ...

was adopted by Maxim Gorky

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov (russian: link=no, Алексе́й Макси́мович Пешко́в; – 18 June 1936), popularly known as Maxim Gorky (russian: Макси́м Го́рький, link=no), was a Russian writer and social ...

, who was a frequent guest at the house. Zinovy was the only Sverdlov to reject revolutionary politics and had little to no contact with Yakov after the revolution.

Yakov excelled at school, and after 4 years in gymnasium left to become a pharmacist's apprentice and a "professional revolutionary," Sverdlov joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

in 1902, and then later the Bolshevik faction, supporting Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

.

In his youth, Sverdlov became friends with a fellow revolutionary Vladimir Lubotsky (later known as Zagorsky). He was involved in the 1905 revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

while living in the Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

. Though never actually attending college, Sverdlov adopted the garb of the radical students at the time – "With his medium height, unruly brown hair, glasses continually perched on his nose, and Tolstoy shirt worn under his jacket, Sverdlov looked like a student, and for us...a student meant a revolutionary."

Sverdlov became a major activist and speaker in Nizhny Novgorod. In 1906, Sverdlov was arrested and held in the Yekaterinburg prison until his release. During his time in prison, Sverdlov continued to educate himself and others, reading Lenin, Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 p ...

, Kautsky

Karl Johann Kautsky (; ; 16 October 1854 – 17 October 1938) was a Czech-Austrian philosopher, journalist, and Marxist theorist. Kautsky was one of the most authoritative promulgators of orthodox Marxism after the death of Friedrich Engels in 1 ...

, Heine

Heine is both a surname and a given name of German origin. People with that name include:

People with the surname

* Albert Heine (1867–1949), German actor

* Alice Heine (1858–1925), American-born princess of Monaco

* Armand Heine (1818–1883) ...

, and more. Sverdlov attempted to live by the motto: "I put books to the test of life, and life to the test of books." For most of the time from his arrest in June 1906 until 1917 he was either imprisoned or exiled. In March 1911, Sverdlov was held in the St. Petersburg House of Pretrial Detention.

Sverdlov married, a second time, with Bolshevik party member and meteorologist named Klavdia Novgorodtseva. In 1911, their first child, Andrei Yakovlevich Sverdlov, was born. In 1913, their second child, Vera, was born and in 1915 Klavdia joined Yakov in exile in the village of Monastyrskoe. Sverdlov and his wife ran a Bolshevik reading circle in the town, which, though illegal, escaped the notice of the local authorities.

During the period 1914–1916 he was in internal exile in Turukhansk

Turukhansk (russian: Туруха́нск) is a rural locality (a '' selo'') and the administrative center of Turukhansky District of Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia, located north of Krasnoyarsk, at the confluence of the Yenisey and Nizhnyaya Tu ...

, Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

, along with Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

(then known as Dzhugashvili). Both had been betrayed by the Okhrana

The Department for Protecting the Public Security and Order (russian: Отделение по охранению общественной безопасности и порядка), usually called Guard Department ( rus, Охранное отд ...

agent Roman Malinovsky

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

. Of Stalin, Sverdlov wrote "The comrade I was with turned out to be such a person, socially, that we didn't talk or see each other. It was terrible." Like Stalin, he was co-opted ''in absentia'' to the 1912 Prague Conference

The Prague Conference, officially the 6th All-Russian Conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, was held in Prague, Austria-Hungary, on 5–17 January 1912. Sixteen Bolsheviks and two Mensheviks attended, although Joseph Stalin an ...

. In 1914, Sverdlov moved to a different village, moving in with his friend Filipp Goloshchyokin

Filipp Isayevich Goloshchyokin (russian: Филипп Исаевич Голощёкин) (born Shaya Itsikovich) (russian: Шая Ицикович) ( – October 28, 1941) was a Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician, and party functionar ...

, known as Georges. In early 1917, Sverdlov received news of the Putilov strike of 1917 The Putilov strike of 1917 is the name given to the strike led by the workers of the Putilov Mill (presently the Leningrad Kirov Plant) which was located in then Petrograd, Russia (present-day St. Petersburg). The strike officially began on Februar ...

in Petrograd. Alongside Goloshchyokin, he set out at once, arriving to Petrograd on 29 March 1917.

Party leader

After the 1917

After the 1917 February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

Sverdlov returned to Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

from exile as head of the Urals Delegation and found his way into Lenin's inner circle. He first met Lenin in April 1917 and subsequently usurped Elena Stasova

Elena Dmitriyevna Stasova ( rus, Елена Дмитриевна Стасова; 15 October Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._3_October.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>O.S._3_October">Old_Style_and_New_Sty ...

as the chairman of the Central Committee Secretariat

Secretariat may refer to:

* Secretariat (administrative office)

* Secretariat (horse)

Secretariat (March 30, 1970 – October 4, 1989), also known as Big Red, was a champion American thoroughbred horse racing, racehorse who is the ninth winne ...

, and became the secretary of the Central Committee of the Party. According to Podvoisky, the chairperson of the Military Revolutionary Committee

The Military Revolutionary Committee (russian: Военно-революционный комитет, ) was the name for military organs created by the Bolsheviks under the soviets in preparation for the October Revolution (October 1917 – Marc ...

, "The person who did more than anyone to help Lenin with the practicalities of translating convictions into votes was Sverdlov." As chairman of the Central Committee, Yakov played an important role in planning the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

and helped make the decision to stage an armed uprising. In November as the Bolsheviks debated whether to postpone or hold elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operate ...

, Sverdlov advocated for immediate elections as promised. When the results came back showing that the Socialist Revolutionaries

The Socialist Revolutionary Party, or the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries (the SRs, , or Esers, russian: эсеры, translit=esery, label=none; russian: Партия социалистов-революционеров, ), was a major politi ...

had won, Sverdlov, Lenin, and Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Буха́рин) ( – 15 March 1938) was a Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician, Marxist philosopher and economist and prolific author on revolutionary theory.

...

dissolved the assembly, leading to a civil war.

Sverdlov is sometimes regarded as the first head of state of the Soviet Union

The Constitution of the Soviet Union recognised the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet and the earlier Central Executive Committee (CEC) of the Congress of Soviets as the highest organs of state authority in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republic ...

, although it was not established until 1922, three years after his death. Sverdlov had a prodigious memory and was able to retain the names and details of fellow revolutionaries in exile. He promoted his friend and suite-mate Varlam Avanesov

Varlam Aleksandrovich Avanesov (russian: Варлаам Александрович Аванесов; born Suren Karpovich Martirosyan, Russian: ''Сурен Карпович Мартиросян''; 1884 – March 16, 1930) was an Armenian Bolsh ...

to second-in-command at the Central Executive Committee, and would later become a top official of the secret police. He also installed Vladimir Volodarsky as commissar of print, propaganda, and agitation until his assassination in 1918. His organizational capability was well-regarded, and during his chairmanship, thousands of local party committees were initiated. One of his comrades recalled that,

ecould tell you everything you needed to know about a comrade: where he was working, what kind of person he was, what he was good at, and what job he should be assigned to in the interests of the cause and for his benefit. Moreover, Sverdlov had a very precise impression of all the comrades: they were so firmly stamped in his memory that he could tell you all about the company each one kept. It is hard to believe, but true.Sverdlov was elected chairman of the

All-Russian Central Executive Committee

The All-Russian Central Executive Committee ( rus, Всероссийский Центральный Исполнительный Комитет, Vserossiysky Centralny Ispolnitelny Komitet, VTsIK) was the highest legislative, administrative and r ...

in November 1917, of which his wife was also a part, becoming thereby ''de jure'' head of state of the Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

until his death. He played important roles in the decision in January 1918 to end the Russian Constituent Assembly

The All Russian Constituent Assembly (Всероссийское Учредительное собрание, Vserossiyskoye Uchreditelnoye sobraniye) was a constituent assembly convened in Russia after the October Revolution of 1917. It met fo ...

and the subsequent signing on 3 March of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace, separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russian SFSR, Russia and the Central Powers (German Empire, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Kingdom of ...

. In March 1918 Sverdlov along with most prominent Bolsheviks fled Petrograd and moved the government headquarters to Moscow – the Sverdlovs moved into a room in the Kremlin.

In March 1918, Sverdlov and the Central Executive Committee discussed how to best remove the "ulcers that socialism has inherited from capitalism" and Yakov advocated for a concentrated effort to turn the poorest peasants in the villages against their kulak

Kulak (; russian: кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈlak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned ove ...

brethren. Alongside Bukharin, the party began a campaign of "concentrated violence" against many members of the landowning, capitalist, and tradesman classes of Russian society.

Romanov family

A number of sources claim that Sverdlov, alongside Lenin and Goloshchyokin, played a major role in the execution of Tsar Nicholas II and his family on 17 July 1918. A book written in 1990 by the Moscow playwright

A book written in 1990 by the Moscow playwright Edvard Radzinsky

Edvard Stanislavovich Radzinsky (russian: Э́двард Станисла́вович Радзи́нский) (born September 23, 1936) is a Russian playwright, television personality, screenwriter, and the author of more than forty popular history ...

claims that Sverdlov ordered their execution on 16 July 1918. This book and other Radzinsky books were characterized as "folk history

A people's history, or history from below, is a type of historical narrative which attempts to account for historical events from the perspective of common people rather than leaders. There is an emphasis on disenfranchised, the oppressed, the p ...

" by journalists and academic historians. However Yuri Slezkine

Yuri Lvovich Slezkine (Russian: Ю́рий Льво́вич Слёзкин ''Yúriy L'vóvich Slyózkin''; born February 7, 1956) is a Russian-born American historian and translator. He is a professor of Russian history, Sovietologist, and Directo ...

in his book ''The Jewish Century'' expressed a slightly different opinion: "Early in the Civil War, in June 1918, Lenin ordered the killing of Nicholas II and his family. Among the men entrusted with carrying out the orders were Sverdlov, Filipp Goloshchyokin

Filipp Isayevich Goloshchyokin (russian: Филипп Исаевич Голощёкин) (born Shaya Itsikovich) (russian: Шая Ицикович) ( – October 28, 1941) was a Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician, and party functionar ...

and Yakov Yurovsky

Yakov Mikhailovich Yurovsky (; Unless otherwise noted, all dates used in this article are of the Gregorian Calendar, as opposed to the Julian Calendar which was used in Russia prior to . – 2 August 1938) was a Russian Old Bolshevik, revo ...

".

The 1922 book by a White Army

The White Army (russian: Белая армия, Belaya armiya) or White Guard (russian: Бѣлая гвардія/Белая гвардия, Belaya gvardiya, label=none), also referred to as the Whites or White Guardsmen (russian: Бѣлогв� ...

general, Mikhail Diterikhs

Mikhail Konstantinovich Diterikhs (russian: Михаи́л Константи́нович Ди́терихс, r=Michaíl Konstantinovič Díterichs; May 17, 1874 – September 9, 1937) served as a general in the Imperial Russian Army and subsequent ...

, ''The Murder of the Tsar's Family and members of the House of Romanov in the Urals'', sought to portray the murder of the royal family as a Jewish plot against Russia. It referred to Sverdlov by his Jewish nickname "Yankel" and to Goloshchekin as "Isaac". This book in turn was based on an account by one Nikolai Sokolov, special investigator for the Omsk

Omsk (; rus, Омск, p=omsk) is the administrative center and largest city of Omsk Oblast, Russia. It is situated in southwestern Siberia, and has a population of over 1.1 million. Omsk is the third largest city in Siberia after Novosibirsk ...

regional court, whom Diterikhs assigned with the task of investigating the disappearance of the Romanovs while serving as regional governor under the White regime during the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

. The investigating magistrate in Ekaterinburg in 1918 saw the signed telegraphic instructions to execute the Imperial Family came from Sverdlov. These details were published in 1966.

According to Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

's diaries, after returning from the front (of the Russian Civil War) he had the following dialogue with Sverdlov:

Red Terror and decossackization

Following the assassination ofMoisei Uritsky

Moisei Solomonovich Uritsky ( ua, Мойсей Соломонович Урицький; russian: Моисей Соломонович Урицкий; – 30 August 1918) was a Bolshevik revolutionary leader in Russia. After the October Revol ...

and the assassination attempt

This is a list of survivors of assassination attempts, listed chronologically. It does ''not'' include those who were heads of state or government at the time of the assassination attempt. See List of heads of state and government who survived as ...

on Lenin in August 1918, Sverdlov drafted a document that called for "merciless mass terror against all the enemies of the revolution".Page 158, Under his and Lenin's leadership, the Central Executive Committee adopted Sverdlov's resolution calling for "mass red terror against the bourgeoisie and its agents." During Lenin's recovery Sverdlov moved into Lenin's office in the Kremlin and took over some of Lenin's official obligations. He oversaw the interrogation of Lenin's would-be assassin, Fanny Kaplan

Fanny Efimovna Kaplan (russian: Фа́нни Ефи́мовна Капла́н, links=no; real name Feiga Haimovna Roytblat, ; February 10, 1890 – September 3, 1918) was a Ukrainian Jewish woman, Socialist-Revolutionary, and early Soviet dissi ...

, and even moved Kaplan from the Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fsʲɪrɐˈsʲijskəjə tɕrʲɪzvɨˈtɕæjnəjə kɐˈmʲisʲɪjə), abbreviated ...

headquarters

Headquarters (commonly referred to as HQ) denotes the location where most, if not all, of the important functions of an organization are coordinated. In the United States, the corporate headquarters represents the entity at the center or the to ...

to be held in a basement room underneath Sverdlov's apartment. Sverdlov's deputy Avanesov gave the order for Kaplan's execution and Sverdlov himself personally ordered that the body be "destroyed without a trace."

Sverdlov supported the Red Terror campaign, specifically when it came to the policy of decossackization

De-Cossackization (Russian: Расказачивание, ''Raskazachivaniye'') was the Bolshevik policy of systematic repressions against Cossacks of the Russian Empire, especially of the Don and the Kuban, between 1919 and 1933 aimed at the el ...

that was started in 1917 as a part of the Russian Civil War. This policy resulted in the deaths of thousands of Cossacks, while the Soviet government confiscated land and food produced by the Cossack population. Sverdlov wrote that "not a single crime against the revolutionary military spirit will remain unpunished," and that the release of Cossack prisoners was unacceptable. This policy was temporarily suspended in March 1919 while Sverdlov was in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

overseeing the election of the Ukrainian Communist Party's central committee.

Death

There are various theories on how he died and none can be proven officially such as poisoning, beating or flu. He is most commonly attributed to have died of either

There are various theories on how he died and none can be proven officially such as poisoning, beating or flu. He is most commonly attributed to have died of either typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

or more likely the Spanish flu

The 1918–1920 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case was ...

, after a political visit to the Ukraine and Oryol

Oryol ( rus, Орёл, p=ɐˈrʲɵl, lit. ''eagle''), also transliterated as Orel or Oriol, is a city and the administrative center of Oryol Oblast situated on the Oka River, approximately south-southwest of Moscow. It is part of the Central Fed ...

. Kremlin doctors diagnosed him with the Spanish flu. Even as his illness progressed, he continued to perform his duties as chairman of the Central Committee. On 14 March 1919 Sverdlov lost consciousness and on the 16th he died at the age of 33.Page 164,

He is buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis

The Kremlin Wall Necropolis was the national cemetery for the Soviet Union. Burials in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis in Moscow began in November 1917, when 240 pro-Bolshevik individuals who died during the Moscow Bolshevik Uprising were buried in m ...

in Moscow. Today his grave is one of the twelve individual tombs located between the Lenin Mausoleum

Lenin's Mausoleum (from 1953 to 1961 Lenin's & Stalin's Mausoleum) ( rus, links=no, Мавзолей Ленина, r=Mavzoley Lenina, p=məvzɐˈlʲej ˈlʲenʲɪnə), also known as Lenin's Tomb, situated on Red Square in the centre of Moscow, is ...

and the Kremlin wall

The Moscow Kremlin Wall is a defensive wall that surrounds the Moscow Kremlin, recognisable by the characteristic notches and its Kremlin towers. The original walls were likely a simple wooden fence with guard towers built in 1156.

The Kremlin w ...

.

He was succeeded in an interim capacity by Mikhail Vladimirsky

Mikhail Fyodorovich Vladimirsky (russian: Михаи́л Фёдорович Влади́мирский; – 2 April 1951) was a Soviet politician and Bolshevik revolutionary who was for a short period of time, the Chairman of the All-Russian C ...

, and eventually by Mikhail Kalinin

Mikhail Ivanovich Kalinin (russian: link=no, Михаи́л Ива́нович Кали́нин ; 3 June 1946), known familiarly by Soviet citizens as "Kalinych", was a Soviet politician and Old Bolshevik revolutionary. He served as head of s ...

as Chairman of the Central Executive Committee, and by Elena Stasova

Elena Dmitriyevna Stasova ( rus, Елена Дмитриевна Стасова; 15 October Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._3_October.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>O.S._3_October">Old_Style_and_New_Sty ...

as Chairwoman of the Secretariat.

Legacy

* In a speech on 18 March 1919 Vladimir Lenin praised Sverdlov and his contributions to the revolution. He called Sverdlov "the most perfectly complete type of professional revolutionary." * The Central School for Soviet and Party Work, housed in the former Merchants House, Moscow was renamed theSverdlov Communist University

The Sverdlov Communist University (Russian: Коммунистический университет имени Я. М. Свердлова) was a school for Soviet activists in Moscow, founded in 1918 as the Central School for Soviet and Party Work. ...

shortly after Sverdlov's death.

* The Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution of 1917. It developed from a ...

destroyer leader (commissioned during 1913) was renamed during 1923.

* The first ship of the s was also named after him.

* Yekaterinburg

Yekaterinburg ( ; rus, Екатеринбург, p=jɪkətʲɪrʲɪnˈburk), alternatively romanized as Ekaterinburg and formerly known as Sverdlovsk ( rus, Свердло́вск, , svʲɪrˈdlofsk, 1924–1991), is a city and the administra ...

, dubbed the "third capital of Russia", as it is ranked third by the size of economy, culture, transportation and tourism, was renamed "Sverdlovsk" in 1924 and returned to its former name in 1991.

* In 1938 a number of Ukrainian settlements as well as the Sverdlov mine (part of Sverdlovantratsyt company in 2010s) were merged into the city of Sverdlovsk, which the Ukrainian government renamed Dovzhansk on 12 May 2016, although the renaming could not be enforced due to the Russo-Ukrainian War

The Russo-Ukrainian War; uk, російсько-українська війна, rosiisko-ukrainska viina. has been ongoing between Russia (alongside Russian separatist forces in Donbas, Russian separatists in Ukraine) and Ukraine since Feb ...

.

* A few locations in the former Soviet Union still bear Sverdlov's name, in the Russian Federation and in Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan,, pronounced or the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Kyrgyzstan is bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, Tajikistan to the south, and the People's Republic of China to the east. ...

. Others have been renamed.

See also

*Zinovy Peshkov

Zinovy Alekseyevich Peshkov (russian: Зиновий Алексеевич Пешков, french: Zinovi Pechkoff or ''Pechkov'', 16 October 1884 – 27 November 1966) was a Russian-born French general and diplomat.

Early life

Born as Zalman ...

, Yakov's brother

*Yakov Sverdlov (film)

Yakov Sverdlov', (russian: Яков Свердлов) is a 1940 Soviet drama film directed by Sergei Yutkevich.

Plot

The film tells about the life and work of the Chairman of the Central Executive Committee Yakov Sverdlov.

Starring

* Leonid L ...

References

Sources

* * * *Slezkine, Yuri (2019). ''The House of Government

''The House of Government: A Saga of the Russian Revolution'' is a 2017 study of the history of the Russian Revolution, the formation of the Soviet Union, and its early history from the days of the New Economic Policy into the early days of Stali ...

.'' Princeton University Press.

External links

Leon Trotsky: Jacob Sverdlov – 1925 memorial essay

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Sverdlov, Yakov 1885 births 1919 deaths Politicians from Nizhny Novgorod Russian Jews Old Bolsheviks Russian communists People of the Russian Revolution People of the Russian Civil War Heads of state of Russia Communist rulers Soviet politicians Anti-monarchists Politicide perpetrators Regicides of Nicholas II Russian revolutionaries Heads of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union members People of the 1905 Russian Revolution Jewish socialists Jewish Soviet politicians Burials at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis Deaths from Spanish flu Infectious disease deaths in Russia