Early life and background

Suzanne Rachel Flore Lenglen was born in the Lenglen's father attended tennis tournaments on the Riviera circuit, where the world's best players competed in the first half of the year. Having played the sport recreationally, he bought Lenglen a racket from a toy shop in June 1910 shortly after she had turned 11 years old, and set up a makeshift court on the lawn of their house. She quickly showed enough skill to convince her father to get her a proper racket from a tennis manufacturer within a month. He then developed training exercises and played against his daughter. Three months later, Lenglen travelled to Paris to play on a proper clay court owned by her father's friend, Dr. Cizelly. At Cizelly's recommendation, she entered a local high-level tournament in Chantilly. In the singles handicap event, Lenglen won four rounds and finished in second place.

Lenglen's success at the Chantilly tournament prompted her father to train her more seriously. He studied the leading male and female players and decided to teach Lenglen the tactics from the men's game, which were more aggressive than the women's style of slowly constructing points from the baseline. When the family returned to Nice towards the end of autumn, her father arranged for her to play twice a week at the Nice Lawn Tennis Club even though children had never been allowed on the courts, and had her practise with leading male players at the club. Lenglen began training with Joseph Negro, the club's teaching professional. Negro had a wide variety of shots in his repertoire and trained Lenglen to play the same way. As Lenglen's primary coach, her father employed harsh and rigorous methods, saying, "I was a hard taskmaster, and although my advice was always well intentioned, my criticisms were at times severe, and occasionally intemperate." Lenglen's parents watched her matches and discussed her minute errors between themselves throughout, showing restraint in their criticisms only when she was sick. As a result, Lenglen became comfortable with appearing ill, which made it difficult for others to tell if she was sick.

Lenglen's father attended tennis tournaments on the Riviera circuit, where the world's best players competed in the first half of the year. Having played the sport recreationally, he bought Lenglen a racket from a toy shop in June 1910 shortly after she had turned 11 years old, and set up a makeshift court on the lawn of their house. She quickly showed enough skill to convince her father to get her a proper racket from a tennis manufacturer within a month. He then developed training exercises and played against his daughter. Three months later, Lenglen travelled to Paris to play on a proper clay court owned by her father's friend, Dr. Cizelly. At Cizelly's recommendation, she entered a local high-level tournament in Chantilly. In the singles handicap event, Lenglen won four rounds and finished in second place.

Lenglen's success at the Chantilly tournament prompted her father to train her more seriously. He studied the leading male and female players and decided to teach Lenglen the tactics from the men's game, which were more aggressive than the women's style of slowly constructing points from the baseline. When the family returned to Nice towards the end of autumn, her father arranged for her to play twice a week at the Nice Lawn Tennis Club even though children had never been allowed on the courts, and had her practise with leading male players at the club. Lenglen began training with Joseph Negro, the club's teaching professional. Negro had a wide variety of shots in his repertoire and trained Lenglen to play the same way. As Lenglen's primary coach, her father employed harsh and rigorous methods, saying, "I was a hard taskmaster, and although my advice was always well intentioned, my criticisms were at times severe, and occasionally intemperate." Lenglen's parents watched her matches and discussed her minute errors between themselves throughout, showing restraint in their criticisms only when she was sick. As a result, Lenglen became comfortable with appearing ill, which made it difficult for others to tell if she was sick.

Amateur career

1912–13: Maiden titles

Lenglen entered her first non-handicap singles event in July 1912 at the Compiègne Championships near her hometown, her only regular event of the year. She won her debut match in the quarterfinals before losing her semifinal to Jeanne Matthey. She also played in the singles and mixed doubles handicap events, winning both of them. When Lenglen returned to Nice in 1913, she entered a handicap doubles event in

Lenglen entered her first non-handicap singles event in July 1912 at the Compiègne Championships near her hometown, her only regular event of the year. She won her debut match in the quarterfinals before losing her semifinal to Jeanne Matthey. She also played in the singles and mixed doubles handicap events, winning both of them. When Lenglen returned to Nice in 1913, she entered a handicap doubles event in 1914: World Hard Court champion

Back on the Riviera in 1914, Lenglen focused on regular events. Her victory in singles against the high-ranking British player Ruth Winch was regarded as a huge surprise by the tennis community. However, Lenglen still struggled at larger tournaments early in the year, losing to Ryan in the quarterfinals at Monte Carlo and six-time Wimbledon champion Dorothea Lambert Chambers in the semifinals at the South of France Championships. In May, Lenglen was invited to enter the French Championships, which was restricted to French players. The format gave the defending champion a bye until the final match, known as the challenge round. In that match, they faced the winner of the All Comers' competition, a standard tournament bracket for the remaining players. Lenglen won the All Comers' singles draw of six players to make it to the challenge round against Marguerite Broquedis. Despite winning the first set, she lost the match. This was the last time in Lenglen's career she lost a completed singles match, and the only time she lost a singles final other than by default. Although she also lost the doubles challenge round at the tournament to Blanche and Suzanne Amblard, Lenglen won the mixed doubles title with Max Decugis as her partner.

Lenglen's performance at the French Championships set the stage for her debut at the World Hard Court Championships, one of the major tournaments recognised by the International Lawn Tennis Federation at the time. She won the singles final against Germaine Golding for her first major title. The only set she lost during the event was to Suzanne Amblard in the semifinals. Her volleying ability was instrumental in defeating Amblard, and her ability to outlast Golding in long rallies gave her the advantage in the final. Lenglen also won the doubles title with Ryan over the Amblard sisters without dropping a game in the final. She finished runner-up in mixed doubles to Ryan and Decugis. Following the World Hard Court Championships, Lenglen could have debuted at Wimbledon, but her father decided against it. He did not like her chances of defeating Lambert Chambers on grass, a surface on which she had never competed, given that she had already lost to her earlier in the year on clay.

Back on the Riviera in 1914, Lenglen focused on regular events. Her victory in singles against the high-ranking British player Ruth Winch was regarded as a huge surprise by the tennis community. However, Lenglen still struggled at larger tournaments early in the year, losing to Ryan in the quarterfinals at Monte Carlo and six-time Wimbledon champion Dorothea Lambert Chambers in the semifinals at the South of France Championships. In May, Lenglen was invited to enter the French Championships, which was restricted to French players. The format gave the defending champion a bye until the final match, known as the challenge round. In that match, they faced the winner of the All Comers' competition, a standard tournament bracket for the remaining players. Lenglen won the All Comers' singles draw of six players to make it to the challenge round against Marguerite Broquedis. Despite winning the first set, she lost the match. This was the last time in Lenglen's career she lost a completed singles match, and the only time she lost a singles final other than by default. Although she also lost the doubles challenge round at the tournament to Blanche and Suzanne Amblard, Lenglen won the mixed doubles title with Max Decugis as her partner.

Lenglen's performance at the French Championships set the stage for her debut at the World Hard Court Championships, one of the major tournaments recognised by the International Lawn Tennis Federation at the time. She won the singles final against Germaine Golding for her first major title. The only set she lost during the event was to Suzanne Amblard in the semifinals. Her volleying ability was instrumental in defeating Amblard, and her ability to outlast Golding in long rallies gave her the advantage in the final. Lenglen also won the doubles title with Ryan over the Amblard sisters without dropping a game in the final. She finished runner-up in mixed doubles to Ryan and Decugis. Following the World Hard Court Championships, Lenglen could have debuted at Wimbledon, but her father decided against it. He did not like her chances of defeating Lambert Chambers on grass, a surface on which she had never competed, given that she had already lost to her earlier in the year on clay.

World War I hiatus

After World War I began in August 1914, tournaments ceased, interfering with Lenglen's father's plan for her to enter Wimbledon in 1915. During the war, Lenglen's family lived at their home in Nice, an area less affected by the war than northern France. Although there were no tournaments, Lenglen had plenty of opportunity to train in Nice. Soldiers came to the Riviera to temporarily avoid the war, including leading tennis players such as two-time United States national champions R. Norris Williams and Clarence Griffin. These players competed in charity exhibitions primarily in Cannes to raise money for the French Red Cross. Lenglen participated and had the opportunity to play singles matches against male players.1919: Classic Wimbledon final

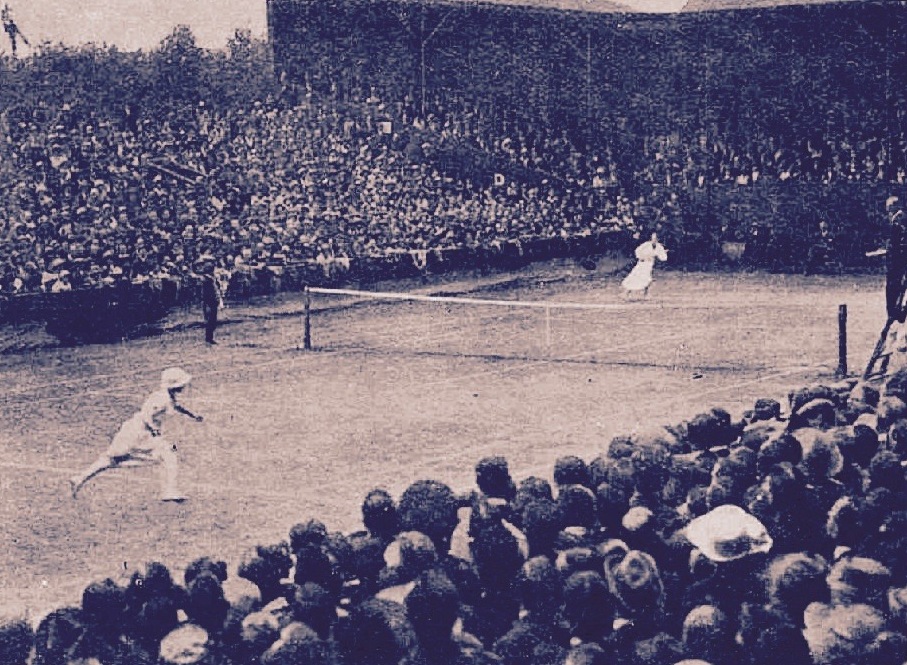

Many tournaments resumed in 1919, following the end of World War I. Lenglen won nine singles titles in ten events, all four of her doubles events, and eight mixed doubles titles in ten events. She won the South of France Championships in March without dropping a game in any of her four matches. Although the French Championships and World Hard Court Championships did not return until the following year, Lenglen was able to debut at Wimbledon in July. She won the six-round All Comers' bracket, losing only six games in the first four rounds. Her biggest challenge in the All Comers' competition was her doubles partner Ryan, who saved match points and levelled the second set of their semifinal at five games, losing only after an hour-long rain delay. Although the 20-year-old Lenglen was considered a favourite against the 40-year-old Lambert Chambers in the challenge round, Lambert Chambers was able to trouble Lenglen with well-placed drop shots. Lenglen won the first set 10–8 after both players saved two set points. After saving two match points, Lenglen won the third set 9–7 for her first Wimbledon title. The match set the record for most games in a Wimbledon women's singles final with 44, since surpassed only by the 1970 final between Margaret Court and Billie Jean King. More than 8,000 people attended the match, well above the seating capacity of 3,500 on

Many tournaments resumed in 1919, following the end of World War I. Lenglen won nine singles titles in ten events, all four of her doubles events, and eight mixed doubles titles in ten events. She won the South of France Championships in March without dropping a game in any of her four matches. Although the French Championships and World Hard Court Championships did not return until the following year, Lenglen was able to debut at Wimbledon in July. She won the six-round All Comers' bracket, losing only six games in the first four rounds. Her biggest challenge in the All Comers' competition was her doubles partner Ryan, who saved match points and levelled the second set of their semifinal at five games, losing only after an hour-long rain delay. Although the 20-year-old Lenglen was considered a favourite against the 40-year-old Lambert Chambers in the challenge round, Lambert Chambers was able to trouble Lenglen with well-placed drop shots. Lenglen won the first set 10–8 after both players saved two set points. After saving two match points, Lenglen won the third set 9–7 for her first Wimbledon title. The match set the record for most games in a Wimbledon women's singles final with 44, since surpassed only by the 1970 final between Margaret Court and Billie Jean King. More than 8,000 people attended the match, well above the seating capacity of 3,500 on 1920: Olympic champion

Lenglen began 1920 with five singles titles on the Riviera, three of which she won in lopsided finals against Ryan. However, Ryan was able to defeat Lenglen in mixed doubles at Cannes in windy conditions, Lenglen's only mixed doubles loss of the year. Although the World Hard Court Championships returned in May, Lenglen withdrew due to illness. She recovered in time for the French Championships two weeks later and won the singles, doubles, and mixed doubles titles to complete a triple crown. Lenglen easily made it to the challenge round in singles, where she defeated Broquedis in a rematch of the 1914 final. She won the doubles event with Élisabeth d'Ayen and defended her mixed doubles title with Decugis, only needing to play the challenge round.

Lenglen's next event was Wimbledon. Lambert Chambers won the All Comers' final to set up a rematch of the previous year's final. Although the match was expected to be close again and began 2–2, Lenglen won ten of the last eleven games for her second consecutive Wimbledon singles title. She won the triple crown, taking the doubles with Ryan and the mixed doubles with Australian Gerald Patterson. The doubles final was also a rematch of the previous year's final against Lambert Chambers and Larcombe, and the mixed doubles victory came against defending champions Ryan and Lycett. Lenglen's decision to partner with Patterson led to the Fédération Française de Lawn Tennis (FFLT) threatening to not pay her expenses for the Wimbledon trip unless she partnered with a compatriot. Lenglen and her father replied by paying for the trip themselves. After Wimbledon, Lenglen won both of her events in Belgium in the lead-up to the

Lenglen began 1920 with five singles titles on the Riviera, three of which she won in lopsided finals against Ryan. However, Ryan was able to defeat Lenglen in mixed doubles at Cannes in windy conditions, Lenglen's only mixed doubles loss of the year. Although the World Hard Court Championships returned in May, Lenglen withdrew due to illness. She recovered in time for the French Championships two weeks later and won the singles, doubles, and mixed doubles titles to complete a triple crown. Lenglen easily made it to the challenge round in singles, where she defeated Broquedis in a rematch of the 1914 final. She won the doubles event with Élisabeth d'Ayen and defended her mixed doubles title with Decugis, only needing to play the challenge round.

Lenglen's next event was Wimbledon. Lambert Chambers won the All Comers' final to set up a rematch of the previous year's final. Although the match was expected to be close again and began 2–2, Lenglen won ten of the last eleven games for her second consecutive Wimbledon singles title. She won the triple crown, taking the doubles with Ryan and the mixed doubles with Australian Gerald Patterson. The doubles final was also a rematch of the previous year's final against Lambert Chambers and Larcombe, and the mixed doubles victory came against defending champions Ryan and Lycett. Lenglen's decision to partner with Patterson led to the Fédération Française de Lawn Tennis (FFLT) threatening to not pay her expenses for the Wimbledon trip unless she partnered with a compatriot. Lenglen and her father replied by paying for the trip themselves. After Wimbledon, Lenglen won both of her events in Belgium in the lead-up to the 1921: Only singles defeat post-World War I

Lenglen again dominated the tournaments on the Riviera in 1921, winning eight titles in singles, six in doubles, and seven in mixed doubles. Her only loss came in mixed doubles. She won all of her matches against Ryan, four in singles and five in mixed doubles. All of Lenglen's doubles titles on the Riviera were with Ryan.

Lenglen defended her triple crown at the French Championships. Later that month, she returned to the World Hard Court Championships, where five-time United States national singles champion Molla Mallory was making her debut. The United States Lawn Tennis Association (USLTA) sent Mallory and

Lenglen again dominated the tournaments on the Riviera in 1921, winning eight titles in singles, six in doubles, and seven in mixed doubles. Her only loss came in mixed doubles. She won all of her matches against Ryan, four in singles and five in mixed doubles. All of Lenglen's doubles titles on the Riviera were with Ryan.

Lenglen defended her triple crown at the French Championships. Later that month, she returned to the World Hard Court Championships, where five-time United States national singles champion Molla Mallory was making her debut. The United States Lawn Tennis Association (USLTA) sent Mallory and 1922: Start of 179-match win streak

During the 1922 season, Lenglen did not lose a match in any discipline other than by default. She did not return to competitive tennis until March, six months after her loss to Mallory. Lenglen's first tournament back was the South of France Championships, where she won the doubles and mixed doubles titles. She did not play the singles event and did not play singles again until a month later at the Beausoleil Championships in Monte Carlo, where she won the title without dropping a game. This tournament began a 179-match win streak that Lenglen continued through the end of her amateur career. In the middle of the year, Lenglen won triple crowns at the World Hard Court Championships, the French Championships, and Wimbledon. At the first, she saved two set points in her semifinal against McKane before winning the set 10–8. Needing to play only three challenge round matches at the French, Lenglen agreed to forgo the challenge round system at Wimbledon and be included in the main draw at the request of the tournament organisers. In the singles final, she faced Mallory in a rematch of their U.S. National Championship meeting. Like in the United States, Mallory won the first two games of the final. However, Lenglen rebounded and won the next twelve games for the title. The final remains the shortest in Wimbledon history, lasting only 26 minutes.1923: Career-best 45 titles

Lenglen entered more events and won more titles in 1923 than any other year. She won all 16 of the singles events she entered, as well as 13 of 14 doubles events, and 16 of 18 mixed doubles events. Unlike previous years, she did not default a match in any discipline. At the beginning of the season, Mallory travelled to France to make her debut on the French Riviera circuit. Lenglen and Mallory had their last encounter at the South of France Championships, which Mallory entered after not performing well at her other two events on the Riviera. Lenglen defeated her without losing a game. At the same tournament, Lenglen's twelve-month win streak across all disciplines came to an end with a mixed doubles loss to Ryan and Lycett. At what was to be the last edition of the World Hard Court Championships, Lenglen faced McKane in the final in each event, all three of which were held in the same afternoon. She defeated McKane in singles and mixed doubles, the latter of which was with Henri Cochet as her partner for the second consecutive year. With Ryan absent, however, Lenglen partnered with Golding and lost to the British team of McKane and Geraldine Beamish. At the French Championships, Lenglen defended her triple crown without losing a set in spite of the challenge round format being abandoned. She partnered with Brugnon in mixed doubles for the third straight year, and paired with1924: No major titles

Although Lenglen did not lose a match in any discipline in 1924 except by default, she did not win a major tournament for the first time since 1913 aside from her hiatus due to World War I. Minor illnesses limited her to three singles events on the Riviera. Lenglen played doubles more regularly, winning eight titles in both doubles and mixed doubles. In April, Lenglen travelled to Spain to compete at the Barcelona International. Although she won all three events, she contracted jaundice soon after, preventing her from playing the French Championships. Although she had not fully recovered by Wimbledon, she entered the tournament and won her first three singles matches without dropping a game. In the next round, however, Ryan proved to be a more difficult opponent and took the second set from Lenglen 8–6, only the third set of singles Lenglen had lost since World War I. Although Lenglen narrowly won the match, she then withdrew from the tournament following the advice of her doctor. She did not play another event the rest of the year, and in particular missed the1925: Open French champion

Lenglen returned to tennis at the Beau Site New Year Meeting in Cannes the first week of the year, winning in doubles with Ryan in her only event. She played singles at only two tournaments on the Riviera, including the South of France Championships. Her only loss during this part of the season was to Ryan and Umberto de Morpurgo at the Côte d'Azur Championships in Cannes. In May, Lenglen entered the French Championships, the inaugural edition open to international players. The tournament was played at St. Cloud at the site of the defunct World Hard Court Championships. Lenglen won the triple crown and was not challenged in singles or mixed doubles. She won the singles final over McKane, losing only three games. She won the mixed doubles final with Brugnon against her doubles partner Julie Vlasto and Cochet. Although Lenglen and Vlasto lost the second set of the doubles final 9–11 to McKane and

Lenglen returned to tennis at the Beau Site New Year Meeting in Cannes the first week of the year, winning in doubles with Ryan in her only event. She played singles at only two tournaments on the Riviera, including the South of France Championships. Her only loss during this part of the season was to Ryan and Umberto de Morpurgo at the Côte d'Azur Championships in Cannes. In May, Lenglen entered the French Championships, the inaugural edition open to international players. The tournament was played at St. Cloud at the site of the defunct World Hard Court Championships. Lenglen won the triple crown and was not challenged in singles or mixed doubles. She won the singles final over McKane, losing only three games. She won the mixed doubles final with Brugnon against her doubles partner Julie Vlasto and Cochet. Although Lenglen and Vlasto lost the second set of the doubles final 9–11 to McKane and 1926: Match of the Century

The 1926 season unexpectedly was Lenglen's last as an amateur. At the beginning of the season, three-time reigning U.S. national champion Helen Wills travelled to the French Riviera with the hope of playing a match against Lenglen. With Wills's level of stardom approaching that of Lenglen's, there was an immense amount of hype for a match between them to take place. They entered the same singles draw only once, at the Carlton Club in Cannes. When Lenglen and Wills both made the final with little opposition, the club doubled the number of seats around their main court and all three thousand seats plus standing room sold out. Spectators unable to get into the venue attempted to watch the match by climbing trees and ladders or by purchasing unofficial tickets for the windows and roofs of villas across the street. In what was called the Match of the Century, Lenglen defeated Wills in straight sets. The first match point became chaotic when a winner from Wills was called

The 1926 season unexpectedly was Lenglen's last as an amateur. At the beginning of the season, three-time reigning U.S. national champion Helen Wills travelled to the French Riviera with the hope of playing a match against Lenglen. With Wills's level of stardom approaching that of Lenglen's, there was an immense amount of hype for a match between them to take place. They entered the same singles draw only once, at the Carlton Club in Cannes. When Lenglen and Wills both made the final with little opposition, the club doubled the number of seats around their main court and all three thousand seats plus standing room sold out. Spectators unable to get into the venue attempted to watch the match by climbing trees and ladders or by purchasing unofficial tickets for the windows and roofs of villas across the street. In what was called the Match of the Century, Lenglen defeated Wills in straight sets. The first match point became chaotic when a winner from Wills was called Wimbledon misunderstanding

Although Lenglen was a heavy favourite at Wimbledon with Wills not participating, she began the tournament facing two issues. She was concerned with her family's finances as her father's health was worsening, and she was not content with the FFLT wanting her to enter the doubles event with a French partner instead of her usual partner Ryan. Although Lenglen agreed to play with Vlasto as the FFLT wanted, she was unsettled by being drawn against Ryan in her opening doubles match. Lenglen's situation did not improve once the tournament began. She opened the singles event with an uncharacteristic win against Browne in which she lost five games, the same number she had lost in the entire 1925 singles event. Her next singles match was then moved before her doubles match to accommodate the royal family, who planned to be in attendance. Wanting to play doubles first, Lenglen asked for the match to be rescheduled. Although the request was never received, she arrived at the grounds late. After Wimbledon officials confronted her in anger over keeping Queen Mary waiting, she refused to play. The club ultimately adhered to Lenglen's wishes and rescheduled both matches with the doubles first. Nonetheless, Lenglen and Vlasto were defeated by Ryan and Browne in three sets while the crowd who typically supported Lenglen turned against her. Although she defeatedProfessional career

United States tour (1926–27)

A month after her withdrawal from Wimbledon, Lenglen signed a $50,000 contract (equivalent to about $ in 2020) with American sports promoter C. C. Pyle to headline a four-month professional tour in the United States beginning in October 1926. She had begun discussing a professional contract with Pyle's associate William Pickens when he visited her on the Riviera in April. Lenglen had previously turned down an offer of 200,000 francs (equivalent to about $ in 2020) to turn professional in the United States following her last victory over Molla Mallory in 1923, declining in large part to keep her amateur status. She became less concerned with that, however, after the crowd turned against her at Wimbledon. She was more interested in keeping her social status, and was convinced by Pyle that turning professional would not hurt her stardom or damage her reputation. With Lenglen on the tour, Pyle attempted to recruit other top players, including Wills, McKane, and leading Americans

A month after her withdrawal from Wimbledon, Lenglen signed a $50,000 contract (equivalent to about $ in 2020) with American sports promoter C. C. Pyle to headline a four-month professional tour in the United States beginning in October 1926. She had begun discussing a professional contract with Pyle's associate William Pickens when he visited her on the Riviera in April. Lenglen had previously turned down an offer of 200,000 francs (equivalent to about $ in 2020) to turn professional in the United States following her last victory over Molla Mallory in 1923, declining in large part to keep her amateur status. She became less concerned with that, however, after the crowd turned against her at Wimbledon. She was more interested in keeping her social status, and was convinced by Pyle that turning professional would not hurt her stardom or damage her reputation. With Lenglen on the tour, Pyle attempted to recruit other top players, including Wills, McKane, and leading Americans British tour (1927)

A few months after the end of the United States tour, Lenglen signed with British promoter Charles Cochran to headline a shorter professional tour in the United Kingdom. Cochran recruitedAftermath

Lenglen was widely criticised for her decision to turn professional. Once the tour began, the FFLT expelled her and Féret while the All England Lawn Tennis Club revoked her membership. Lenglen in turn criticised amateur tennis for her nearing poverty. In the program for the United States professional tour, she stated, "In the twelve years I have been champion I have earned literally millions of francs for tennis... And in my whole lifetime I have not earned $5,000 – not one cent of that by my specialty, my life study – tennis... I am twenty-seven and not wealthy – should I embark on any other career and leave the one for which I have what people call genius? Or should I smile at the prospect of actual poverty and continue to earn a fortune – for whom?" She criticised the barriers that typically prevented ordinary people from becoming tennis players, stating, "Under these absurd and antiquated amateur rulings, only a wealthy person can compete, and the fact of the matter is that only wealthy people ''do'' compete. Is that fair? Does it advance the sport?" Lenglen did not participate in any other professional tours after 1927. She never formally applied to be reinstated as an amateur with the FFLT either. She had asked about the possibility in 1932 after Féret was reinstated, but was told to wait another three years and decided against it.Rivalries

Lenglen vs. Mallory

Molla Mallory was the only player to defeat Lenglen in singles after World War I. Fifteen years older than Lenglen and originally from Norway, Mallory won a bronze medal at the

Molla Mallory was the only player to defeat Lenglen in singles after World War I. Fifteen years older than Lenglen and originally from Norway, Mallory won a bronze medal at the Lenglen and Ryan

Lenglen's usual doubles partner Elizabeth Ryan was also her most frequent opponent in singles. Born in the United States, Ryan travelled to England in 1912 to visit her sister before deciding to stay there permanently. Although she lost all four of her appearances in major finals, Ryan won 26 major titles between doubles and mixed doubles. The biggest strength of her game was volleying. Tennis writer Ted Tinling said, "volleying as a fundamental, aggressive technique was first injected into the women's game by Ryan." Lenglen and Ryan first partnered together at a handicap event in Monte Carlo in 1913 when they were 13 and 20 years old respectively. After losing the final at that tournament, the two of them never lost a regular doubles match, only once dropping a set in 1923 to Dorothea Lambert Chambers and Kathleen McKane, again at Monte Carlo. Ryan was Lenglen's doubles partner for 40 of her 74 doubles titles, including all six at Wimbledon and two of three at the World Hard Court Championships. Ryan defeated Lenglen in their first singles meeting in straight sets at Monte Carlo in 1914 and also won a set in their second meeting two months later. Following their first encounter, Lenglen won all 17 of their remaining matches, including five at Wimbledon and two major finals. The only time Ryan won a set against Lenglen after World War I was in the quarterfinals at Wimbledon in 1924, where Lenglen withdrew due to illness in the following round. When the FFLT asked Lenglen to take a French partner in doubles at Wimbledon in 1926, Ryan partnered with Mary Browne to defeat Lenglen and her new partner Julie Vlasto, coming from three match points down in the second set. Ryan also won their only other doubles meeting in 1914. In mixed doubles, Lenglen compiled a 23–9 record against Ryan. Half of her career mixed doubles losses were to Ryan. After losing their first six encounters, she recovered to win the next thirteen. Lenglen won her first mixed doubles match against Ryan at the 1920 Beaulieu tournament, starting a win streak that ended with a loss to Ryan and Lycett at the 1923 South of France Championships.Overlap with Wills

Helen Wills was the closest to becoming Lenglen's counterpart. Wills finished her career with 19 Grand Slam singles titles, a record that stood until 1970. She succeeded Lenglen as world No. 1 in 1927 and kept that ranking for the next six years and nine of the next twelve overall until 1938. Late in Lenglen's amateur career, Wills had built a similar level of stardom to Lenglen by winning the 1924 Olympic gold medal in singles in Lenglen's absence while still only 18 years old. Although their careers overlapped when Wills visited Europe in 1924 and 1926, Lenglen faced Wills only once in her career. Lenglen withdrew from Wimbledon and the Olympics due to jaundice in 1924, and Wills withdrew from the French Championships and Wimbledon in 1926 due to appendicitis, preventing a longer rivalry between tennis's two biggest female stars of the 1920s from emerging.Playing style

Describing Lenglen's all-court style of play, Elizabeth Ryan said: "

Describing Lenglen's all-court style of play, Elizabeth Ryan said: "Legacy

Achievements

Lenglen was ranked as the 24th greatest player in history in the '' 100 Greatest of All Time'' television series. She was the ninth-highest ranked woman overall, and the highest-ranked woman to play exclusively in the amateur era. After formal annual women's tennis rankings began to be published by tennis journalist and player A. Wallis Myers in 1921, Lenglen was No. 1 in the world in each of the first six editions of the rankings through her retirement from amateur tennis in 1926. She won a total of 250 titles consisting of 83 in singles, 74 in doubles, and 93 in mixed doubles. Nine of her singles titles were won without losing a game. Lenglen compiled win percentages of 97.9% in singles and 96.9% across all disciplines. After World War I, she won 287 of 288 singles matches, starting with a 108-match win streak and ending with a 179-match win streak, the latter of which was longer than Helen Wills's longest win streak of 161 matches. Lenglen ended her career on a 250-match win streak on clay. Lenglen's eight Grand Slam women's singles titles are tied for the tenth-most all-time, and tied for fourth in the amateur era behind only Maureen Connolly's nine, Court's thirteen, and Wills's nineteen. Aside from the 1919 Wimbledon Championships, Lenglen did not lose more than three games in a set in any of her other Grand Slam or World Hard Court Championship singles finals. Lenglen's six Wimbledon titles are tied for the sixth-most in history. Her former record of five consecutive Wimbledon titles has since been matched only by Martina Navratilova, who won her sixth in a row in 1987. Lenglen's title at the 1914 World Hard Court Championships made her the youngest major champion in tennis history at 15 years and 16 days old, nearly a year ahead of the next two youngest, Martina Hingis and Lottie Dod. Lenglen won a total of 17 titles at Wimbledon, 19 at the French Championships, and 10 at the World Hard Court Championships across all disciplines. Lenglen completed three Wimbledon triple crowns – winning the singles, doubles, and mixed doubles events at a tournament in the same year – in 1920, 1922, and 1925. She also won two triple crowns at the World Hard Court Championships in 1921 and 1922, and six at the French Championships, the first four of which came consecutively from 1920 through 1923 when the tournament was invitation-only to French nationals and the last two of which came in 1925 and 1926 when the tournament was open to internationals.Mythical persona

Following World War I, Lenglen became a symbol of national pride in France in a country looking to recover from the war. The French press referred to Lenglen as ''notre Suzanne'' (our Suzanne) to characterise her status as a national heroine; and more eminently as ''La Divine'' (The Goddess) to assert her unassailability. The press wrote about Lenglen as if she was infallible at tennis, often attributing any performance that was relatively poor by her standards to various excuses such as the fault of her doubles partner or to having concern over the health of her father. Journalists who criticised Lenglen were condemned and refuted by the rest of the press. At the Olympics, she introduced herself to journalists as "The Great Lenglen", a title that was well received. Before matches, Lenglen would predict to the press that she was going to win, a practice that Americans treated as improper. She explained, "When I am asked a question I endeavour to give a frank answer. If I know I am going to win, what harm is there in saying so?" Lenglen was the first female athlete to be acknowledged as a celebrity outside of her sport. She was acquainted with members of royal families such as King Gustav V of Sweden, and actresses such as Mary Pickford. She was well known by the general public, and her matches were well-attended by people not otherwise interested in tennis. Many of her biggest matches were sold out, including the 1919 Wimbledon final against Lambert Chambers, where the attendance more than doubled the seating capacity of Centre Court, and her first match against Mallory, where tickets were sold at a cost of up to 500 francs (about $ in 2020) and an estimated five thousand people could not gain entry to see the match after it had sold out. The popularity of Lenglen's matches at Wimbledon was a large factor in the club moving the tournament from Worple Road to its modern site at Church Road. A new Centre Court opened in 1922 with a seating capacity of nearly ten thousand, nearly three times larger than that at the old venue. At the Match of the Century against Wills, seated tickets that were sold out at 300 francs, then equivalent to about $11 in the United States (or $ in 2020), were re-sold by scalpers at up to 1200 francs, which was then about $44 (or $ in 2020). This cost far exceeded that for the men's singles final at the U.S. National Championships at the time, which were sold at as low as $2 per seat (about $ in 2020). Lenglen's mythical reputation began at a young age. She was known for a story about her father training her to improve her shot precision as a child by placing a handkerchief at different locations on the court and instructing her to hit it as a target. She was said to be able to hit the handkerchief with ease regardless of the type of incoming shot. Each time she did, he would fold it in half before replacing it with a coin. It was said that Lenglen could hit the coin up to five times in a row.Professional tennis

Lenglen was the first leading tennis player to leave amateur tennis to play professionally, thereby launching playing tennis as a professional career. The exhibition tour she headlined in the United States from 1926 to 1927 in which a few players travelled together to compete against each other across a series of venues was the first of its kind. It established a format that was repeated over twenty times for the next four decades until the start of the Open Era. With Pyle interested in tennis only because of Lenglen, Vincent Richards, the leading male player on Lenglen's United States tour, organised the next such tour featuring himself competing against Karel Koželuh in 1928. He also began organising the first major professional tournaments to feature players who had been top amateurs, beginning with the U.S. Pro Tennis Championships first held later in 1927. As the top women's players nearly all kept their amateur status, women were largely left out of both the travelling exhibition tours and the growing professional tournaments after Lenglen's playing career ended. The next significant exhibition tour to feature women's tennis players did not occur until 1941 when Alice Marble became one of the headliners on a tour that also featured leading male players Don Budge andFashion

Lenglen redefined traditional women's tennis attire early in her career. By the 1919 Wimbledon final, she avoided donning a corset in favour of a short-sleeved blouse and calf-length pleated skirt to go along with a distinctive circular-brimmed bonnet, a stark contrast with her much older opponent Dorothea Lambert Chambers who wore long sleeves and a plain skirt below the calf.

The following year, Lenglen ended the norm of women competing in clothes not suited for playing tennis. She had Jean Patou design her outfits that were not only intended to be stylish, but allowed her to perform her signature leaping ballet motion in points and did not restrict her movement on the court. This type of attire was among the earliest women's sportswear. Unusual for the time, her blouse was sleeveless and her skirt extended only to her knees. Lenglen replaced the bonnet with a bandeau, which became known as the "Lenglen bandeau" and was her signature piece of attire throughout the rest of her career. On the court, she routinely wore makeup and popularised having tanned skin instead of a pale complexion that other players had preferred before her time. Later in her career, she moved away from just wearing white in favour of brighter-coloured outfits. Overall, she pioneered the idea of players using the tennis court to showcase fashion instead of just competing. Off the court, Lenglen frequently wore an oversized and expensive fur coat.

Lenglen redefined traditional women's tennis attire early in her career. By the 1919 Wimbledon final, she avoided donning a corset in favour of a short-sleeved blouse and calf-length pleated skirt to go along with a distinctive circular-brimmed bonnet, a stark contrast with her much older opponent Dorothea Lambert Chambers who wore long sleeves and a plain skirt below the calf.

The following year, Lenglen ended the norm of women competing in clothes not suited for playing tennis. She had Jean Patou design her outfits that were not only intended to be stylish, but allowed her to perform her signature leaping ballet motion in points and did not restrict her movement on the court. This type of attire was among the earliest women's sportswear. Unusual for the time, her blouse was sleeveless and her skirt extended only to her knees. Lenglen replaced the bonnet with a bandeau, which became known as the "Lenglen bandeau" and was her signature piece of attire throughout the rest of her career. On the court, she routinely wore makeup and popularised having tanned skin instead of a pale complexion that other players had preferred before her time. Later in her career, she moved away from just wearing white in favour of brighter-coloured outfits. Overall, she pioneered the idea of players using the tennis court to showcase fashion instead of just competing. Off the court, Lenglen frequently wore an oversized and expensive fur coat.

Honours

Lenglen is honoured in a variety of ways at thePersonal life

Lenglen was in a long-term relationship with Baldwin Baldwin from 1927 to 1932. Baldwin was the grandson and heir to Lucky Baldwin, a prominent businessman and real estate investor active in California. Lenglen met Baldwin during her professional tour in the United States. Although they intended to get married, those plans never materialised largely because Baldwin was already married and his wife would not agree to a divorce while Lenglen and Baldwin were together. During this time, her father died of poor health in 1929. Lenglen was the author of several books on tennis, the first two of which she wrote during her amateur career. Her first book, ''Lawn Tennis for Girls'', covered techniques and advice on tactics for beginner tennis players. She also wrote ''Lawn Tennis: The Game of Nations'' and a romantic novel, ''The Love Game: Being the Life Story of Marcelle Penrose''. Lenglen finished her last book ''Tennis by Simple Exercises'' with Margaret Morris in 1937. The book featured a section by Lenglen on what was needed to become an all-around tennis player and a section by Morris, a choreographer and dancer, on exercises designed for tennis players. She played a role as an actress in the 1935 British musical comedy film '' Things Are Looking Up'', in which she contests a tennis match against the lead character portrayed by Cicely Courtneidge. Following her playing career, Lenglen returned to tennis as a coach in 1933, serving as the director of a school on the grounds of Stade Roland Garros. She opened her own tennis school for girls in 1936 at the Tennis Mirabeau in Paris with the support of the FFLT. She began instructing adults the following year as well. A year later in May 1938, Lenglen became the inaugural director of the French National Tennis School in Paris. Shortly after this appointment, however, Lenglen became severely fatigued while teaching at the school and needed to receive aCareer statistics

Performance timelines

Results from the French Championships before 1924 do not count towards the statistical totals because the tournament was not yet open to international players.Singles

Doubles

Mixed doubles

Source: LittleMajor finals

Grand Slam singles: 8 (8 titles)

World Championship singles: 4 (4 titles)

Source: LittleOlympic medal matches

Singles: 1 (1 gold medal)

Source: LittleSee also

* List of Grand Slam women's singles champions * List of Grand Slam women's doubles champions * List of Grand Slam mixed doubles champions * List of Grand Slam-related tennis recordsNotes

References

Books

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Lenglen, Suzanne 1899 births 1938 deaths Deaths from pernicious anemia Deaths from leukemia Deaths from cancer in France French female tennis players French Championships (tennis) champions Grand Slam (tennis) champions in mixed doubles Grand Slam (tennis) champions in women's doubles Grand Slam (tennis) champions in women's singles International Tennis Hall of Fame inductees Medalists at the 1920 Summer Olympics Olympic bronze medalists for France Olympic gold medalists for France Olympic medalists in tennis Olympic tennis players of France Tennis players from Paris Professional tennis players before the Open Era Tennis players at the 1920 Summer Olympics Wimbledon champions (pre-Open Era) 20th-century French women World number 1 ranked female tennis players Burials at Saint-Ouen Cemetery