Susman Kiselgof on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Susman (Zinoviy Aronovich) Kiselgof (, ; 1878 – 1939) was a Russian-Jewish folksong collector and pedagogue associated with the

Susman (Zinoviy Aronovich) Kiselgof (, ; 1878 – 1939) was a Russian-Jewish folksong collector and pedagogue associated with the

available in digital format

in the collection of the

Susman (Zinoviy Aronovich) Kiselgof (, ; 1878 – 1939) was a Russian-Jewish folksong collector and pedagogue associated with the

Susman (Zinoviy Aronovich) Kiselgof (, ; 1878 – 1939) was a Russian-Jewish folksong collector and pedagogue associated with the Society for Jewish Folk Music

The Jewish art music movement began at the end of the 19th century in Russia, with a group of Russian Jewish classical composers dedicated to preserving Jewish folk music and creating a new, characteristically Jewish genre of classical music. The ...

in St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. Like his contemporary Joel Engel, he conducted fieldwork in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

to collect Jewish religious and secular music. Materials he collected were used in the compositions of such figures as Joseph Achron

Joseph Yulyevich Achron, also seen as Akhron (Russian: Иосиф Юльевич Ахрон, Hebrew: יוסף אחרון) (May 1, 1886April 29, 1943) was a Russian-born Jewish composer and violinist, who settled in the United States. His preoccu ...

, Lev Pulver

Lev Mikhaylovich Pulver (Yiddish pronunciation: Leib Pulver, yi, לייב פּולווער, European spelling: Leo Pulver, russian: link=no, Пульвер, Лев Михайлович), was a Russian-Jewish musician. He was born on in Verkhn ...

, and Alexander Krein

Alexander Abramovich Krein (; 20 October 1883 in Nizhny Novgorod – 25 April 1951 in Staraya Ruza, Moscow Oblast) was a Soviet composer.

Background

The Krein family was steeped in the klezmer tradition; his father Abram (who moved to Russia fr ...

.

Biography

Kiselgof was born inVelizh

Velizh (russian: Ве́лиж) is a town and the administrative center of Velizhsky District in Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the bank of the Western Dvina, from Smolensk, the administrative center of the oblast. Population:

History

In ...

, Vitebsk Governorate

Vitebsk Governorate (russian: Витебская губерния, ) was an administrative unit ( guberniya) of the Russian Empire, with the seat of governorship in Vitebsk. It was established in 1802 by splitting the Byelorussia Governorate and ...

, Russian Empire, on March 15, 1878 (March 3 by the Julian Calendar

The Julian calendar, proposed by Roman consul Julius Caesar in 46 BC, was a reform of the Roman calendar. It took effect on , by edict. It was designed with the aid of Greek mathematicians and astronomers such as Sosigenes of Alexandr ...

then in use). He was the son of a Melamed

Melamed, ''Melammed'' ( he, מלמד, Teacher) in Biblical times denoted a religious teacher or instructor in general (e.g., in Psalm 119:99 and Proverbs 5:13), but which in the Talmudic period was applied especially to a teacher of children, and ...

. He studied at a Cheder

A ''cheder'' ( he, חדר, lit. "room"; Yiddish pronunciation ''kheyder'') is a traditional primary school teaching the basics of Judaism and the Hebrew language.

History

''Cheders'' were widely found in Europe before the end of the 18th ...

and then at the Velizh Jewish College and at the Vilna Jewish Teacher's College in 1894. He never received a full musical education, but showed a natural ability to perceive pitch and learn new instruments. At age 11 he took violin lessons from a klezmer

Klezmer ( yi, קלעזמער or ) is an instrumental musical tradition of the Ashkenazi Jews of Central and Eastern Europe. The essential elements of the tradition include dance tunes, ritual melodies, and virtuosic improvisations played for l ...

named Meir Berson, but was otherwise mostly self-taught. He began his efforts to collect Jewish folk music around 1902. He also became a member of the General Jewish Labour Bund and became involved in its educational efforts for some years, apparently from 1898 to either 1906 or 1908. He may have spent at least a few weeks in prison in 1899 for possession of illegal literature.

After teaching at various institutions in Vitebsk

Vitebsk or Viciebsk (russian: Витебск, ; be, Ві́цебск, ; , ''Vitebsk'', lt, Vitebskas, pl, Witebsk), is a city in Belarus. The capital of the Vitebsk Region, it has 366,299 inhabitants, making it the country's fourth-largest ci ...

, Kiselgof relocated to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

in 1906, where he became a teacher in the school of the Society for the Promotion of Culture among the Jews of Russia

The Society for the Promotion of Culture among the Jews of Russia (Hebrew: ''Hevra Mefitsei Haskalah''; Russian: ''Obshchestva dlia Rasprostraneniia Prosveshcheniia Mezhdu Evreiami v Rossii'', or OPE; sometimes translated into English as "Society ...

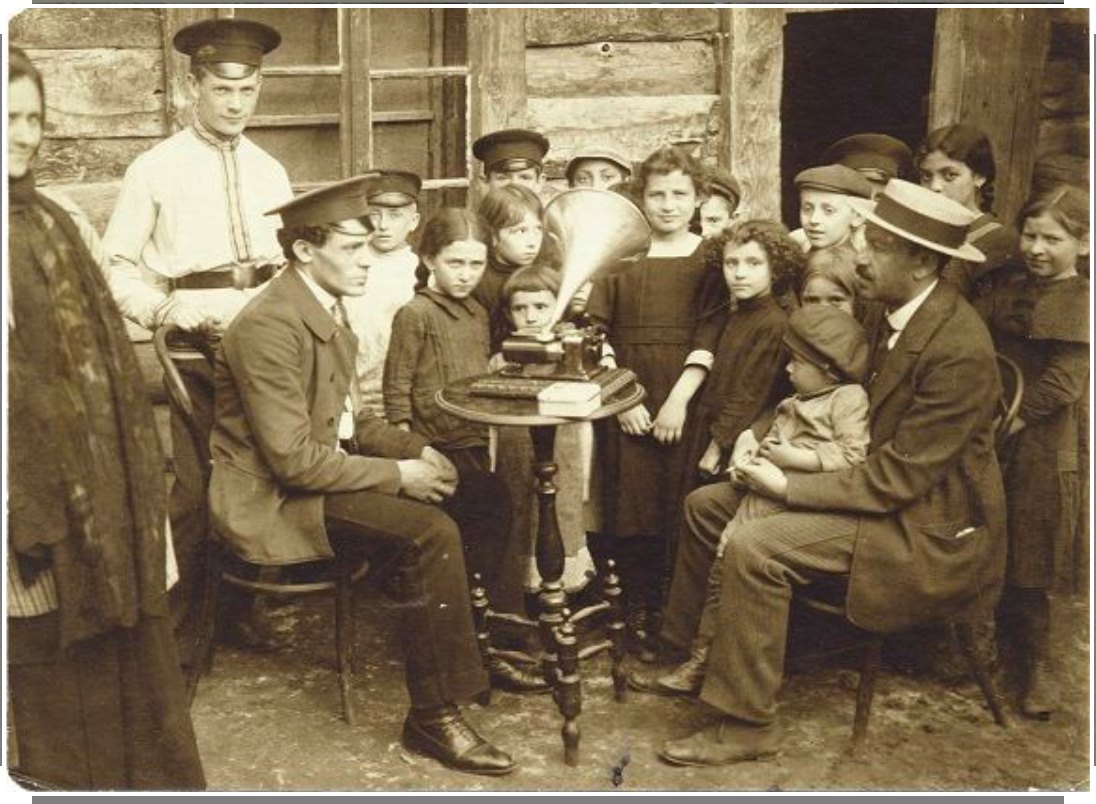

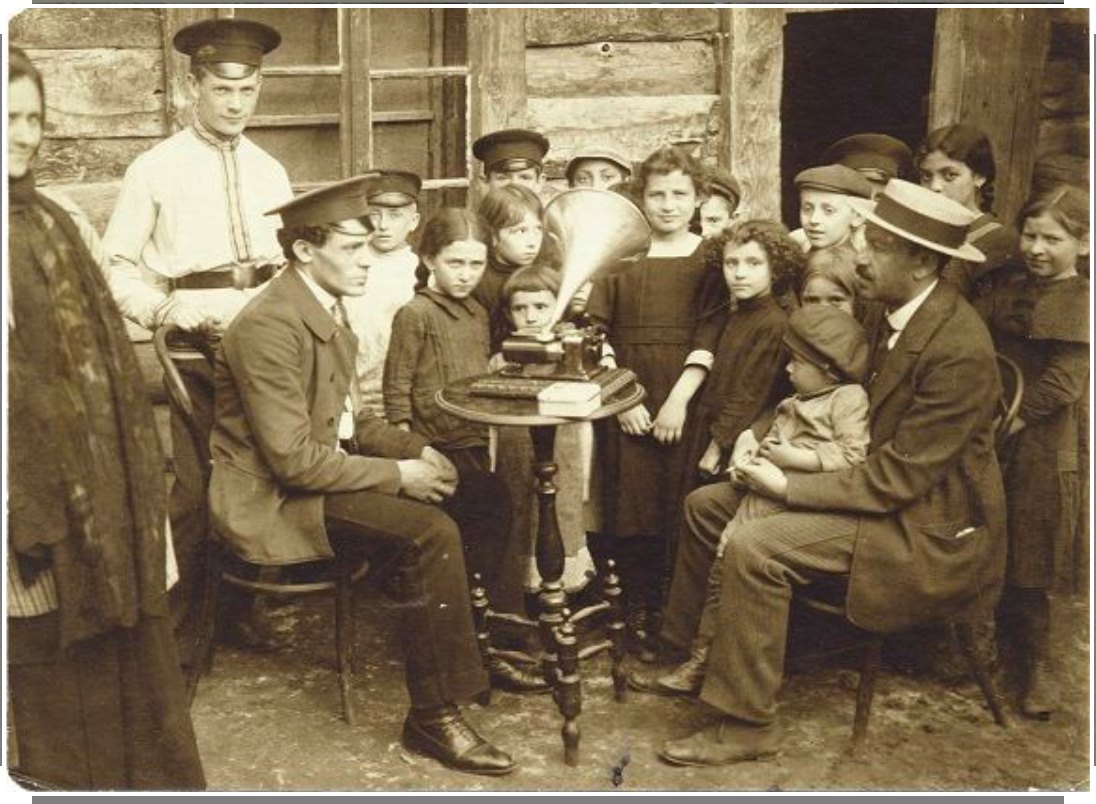

and a choir conductor. In 1908 he married his wife Guta Grigorievna. He continued his efforts to document and research Jewish folklore; from 1907 to 1915 he made annual summer expeditions to the Pale of Settlement

The Pale of Settlement (russian: Черта́ осе́длости, '; yi, דער תּחום-המושבֿ, '; he, תְּחוּם הַמּוֹשָב, ') was a western region of the Russian Empire with varying borders that existed from 1791 to 19 ...

, during which he recorded more than 2000 Jewish folk songs and tunes. His trip in 1907 was to Mogilev Governorate

The Mogilev Governorate () or Government of Mogilev was a governorate () of the Russian Empire in the territory of the present day Belarus. Its capital was in Mogilev, referred to as Mogilev-on-the-Dnieper, or Mogilev Gubernskiy.

The area of the ...

to the center of Chabad Hasidism. In 1913-14 he participated in the well-known ethnographic expeditions of An-sky. He also became very active in Jewish cultural life in St. Petersburg; in 1908, he was a founding member of the Society for Jewish Folk Music

The Jewish art music movement began at the end of the 19th century in Russia, with a group of Russian Jewish classical composers dedicated to preserving Jewish folk music and creating a new, characteristically Jewish genre of classical music. The ...

, and was on its board until 1921. In that group, he worked with such figures as Lazare Saminsky

Lazare Saminsky, born Lazar Semyonovich Saminsky (russian: Лазарь (Элиэзер) Семенович Саминский; Valehotsulove (now Dolynske), near Odessa, 27 October 1882 O.S. / 8 November N.S. – Port Chester, New York, 30 Jun ...

, Mikhail Gnessin, Solomon Rosowsky

Solomon (Salomo) Rosowsky (1878, Riga –1962) was a cantor (hazzan) and composer, and son of the Rigan cantor, Baruch Leib Rosowsky.

Early life

Rosowsky began to study music only after he graduated from the University of Kyiv, with a degree in ...

, and Pavel Lvov. And 1909, he was involved in fundraising efforts to create a new Jewish theatre in the city. He also became a friend and tutor to Jascha Heifetz

Jascha Heifetz (; December 10, 1987) was a Russian-born American violinist. Born in Vilnius, he moved while still a teenager to the United States, where his Carnegie Hall debut was rapturously received. He was a virtuoso since childhood. Fritz ...

during this time.

In 1911, he published his best-known songbook ''Lider-zamelbukh far der yidishe shul un familie'' (Song collection for the Jewish school and family), a collection of roughly 90 songs in choral arrangement with piano. These included secular and religious Yiddish songs and wordless Nigunim

A nigun ( he, ניגון meaning "tune" or "melody", plural nigunim) or niggun (plural niggunim) is a form of Jewish religious song or tune sung by groups. It is vocal music, often with repetitive sounds such as "Bim-Bim-Bam", "Lai-Lai-Lai", " ...

. It was reprinted several times; the 1923 reprint iavailable in digital format

in the collection of the

Yiddish Book Center

The Yiddish Book Center (formerly the National Yiddish Book Center), located on the campus of Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts, United States, is a cultural institution dedicated to the preservation of books in the Yiddish language, a ...

.

In the early period of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, Kiselgof continued along the same music and education path he had already been on. In 1919, he became the musical consultant, teacher and choirmaster for the newly founded Petrograd Jewish Theater Studio of Alexei Granovsky (later known as GOSET

The Moscow State Jewish (Yiddish) Theatre (Russian: Московский Государственный Еврейский Театр; Yiddish: Moskver melukhnisher yidisher teater), also known by its acronym GOSET (ГОСЕТ), was a Yiddish theat ...

). In 1920 he became director of National Jewish School No.11 and Children's Home No.78 in Leningrad. His Wax cylinder

Waxes are a diverse class of organic compounds that are lipophilic, malleable solids near ambient temperatures. They include higher alkanes and lipids, typically with melting points above about 40 °C (104 °F), melting to give low ...

recordings were also transferred from the Jewish Ethnographic Museum in St. Petersburg to the Institute of Proletarian Culture in Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

.

Kiselgof was arrested in the summer of 1938 by the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

. His wife Guta died in July 1938, shortly after his arrest. Meanwhile, his daughter wrote petitions to Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolshevik ...

, head of the NKVD, asking for his release and the right to meet with him. Kiselgof was released from prison on May 11, 1939, and died within a month due to poor health. He was apparently buried in the Preobrazhénskoye Jewish cemetery in Saint Petersburg, although the location of his gravesite cannot be found.

Legacy

A number of composers affiliated with theGOSET

The Moscow State Jewish (Yiddish) Theatre (Russian: Московский Государственный Еврейский Театр; Yiddish: Moskver melukhnisher yidisher teater), also known by its acronym GOSET (ГОСЕТ), was a Yiddish theat ...

theatre and the Society for Jewish Folk Music

The Jewish art music movement began at the end of the 19th century in Russia, with a group of Russian Jewish classical composers dedicated to preserving Jewish folk music and creating a new, characteristically Jewish genre of classical music. The ...

used folkloric materials collected by Kiselgof in their compositions. These include Joseph Achron

Joseph Yulyevich Achron, also seen as Akhron (Russian: Иосиф Юльевич Ахрон, Hebrew: יוסף אחרון) (May 1, 1886April 29, 1943) was a Russian-born Jewish composer and violinist, who settled in the United States. His preoccu ...

in his music for the plays ''The Sorceress'' and ''Mazltov'', Lev Pulver

Lev Mikhaylovich Pulver (Yiddish pronunciation: Leib Pulver, yi, לייב פּולווער, European spelling: Leo Pulver, russian: link=no, Пульвер, Лев Михайлович), was a Russian-Jewish musician. He was born on in Verkhn ...

in the music for ''Two Hundred Thousand'' and ''Night at the Rebbe's House'', and Alexander Krein

Alexander Abramovich Krein (; 20 October 1883 in Nizhny Novgorod – 25 April 1951 in Staraya Ruza, Moscow Oblast) was a Soviet composer.

Background

The Krein family was steeped in the klezmer tradition; his father Abram (who moved to Russia fr ...

in the music for ''At Night at the Old Marketplace''.

His original manuscripts, cylinders and materials were held in the Institute of Proletarian Jewish Culture during his lifetime, and upon its dissolution in 1949 were sent to the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine

The Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine, VNLU ( uk, Національна бібліотека України імені В.І. Вернадського) is the main academic library and main scientific information centre in Ukraine, one of th ...

. Some audio recordings from his expeditions can be purchased on CD from the Vernadsky Library or streamed from their website. Some of those musical manuscripts, along with another set by Avraham-Yehoshua Makonovetsky, are currently being digitized by a crowdsourced project organized by the Klezmer Institute called the Kiselgof-Makonovetsky Digital Manuscript Project (KMDMP).

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kiselgof, Susman Ethnographers 1878 births 1939 deaths People from Velizh Yiddish-language folklore Soviet Jews Ethnomusicologists Educational theorists from the Russian Empire Soviet music educators Music educators from the Russian Empire Yiddish theatre