Susan LaFlesche Picotte on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Susan La Flesche Picotte (June 17, 1865 – September 18, 1915, Omaha) was a Native American doctor and reformer in the late 19th century. She is widely acknowledged as one of the first Indigenous peoples, and the first Indigenous woman, to earn a medical degree. She campaigned for

As a child, LaFlesche witnessed a sick Indian woman die after a white doctor refused to treat her. She later credited this tragedy as her inspiration to train as a physician, so she could provide care for the people she lived with on the Omaha Reservation.

As a child, LaFlesche witnessed a sick Indian woman die after a white doctor refused to treat her. She later credited this tragedy as her inspiration to train as a physician, so she could provide care for the people she lived with on the Omaha Reservation.

Though women were often

Though women were often  At the WMCP, La Flesche studied

At the WMCP, La Flesche studied

La Flesche returned to the Omaha reservation in 1889 to take up her position as the physician at the government boarding school on the reservation, run by the

La Flesche returned to the Omaha reservation in 1889 to take up her position as the physician at the government boarding school on the reservation, run by the

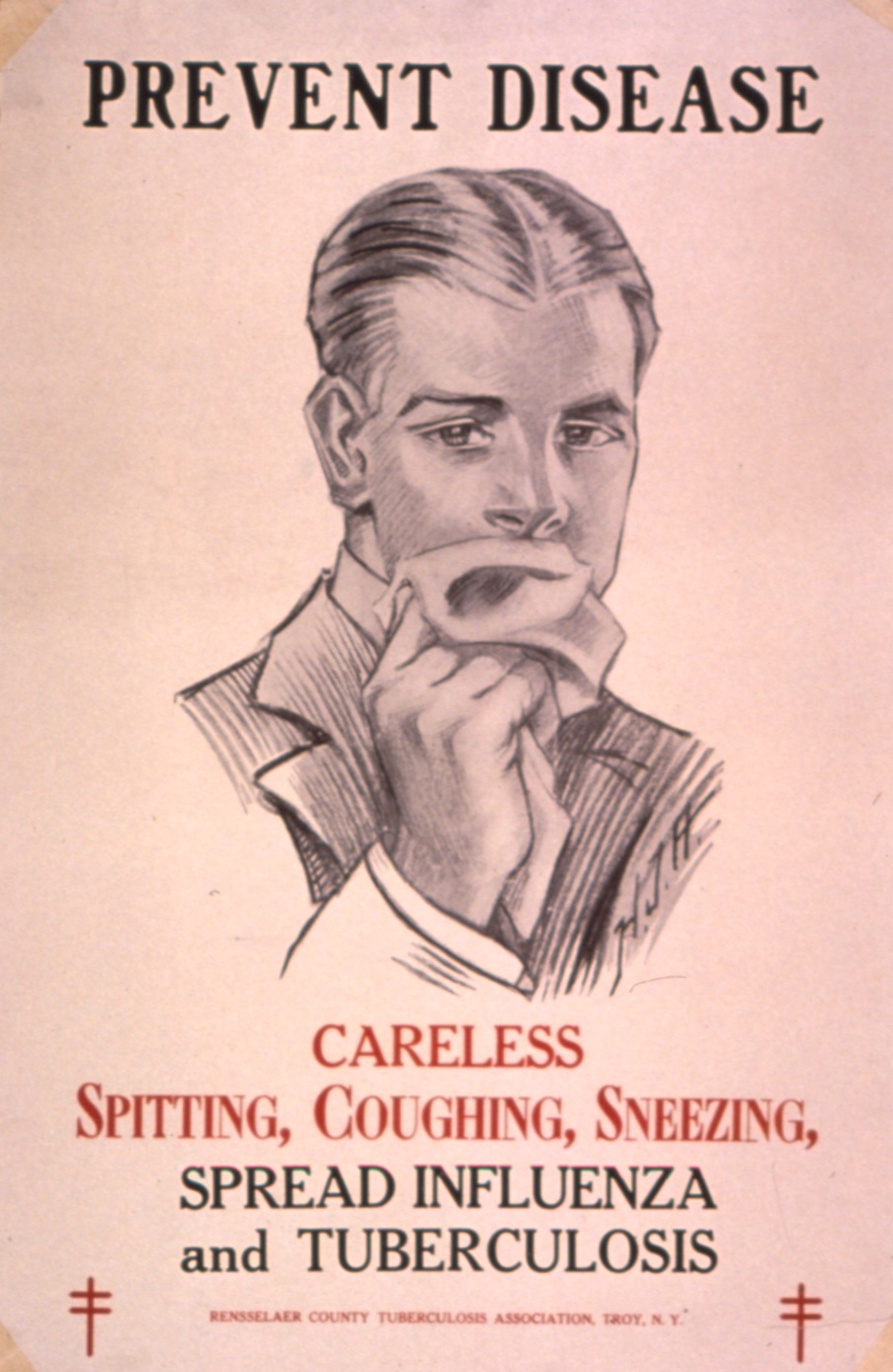

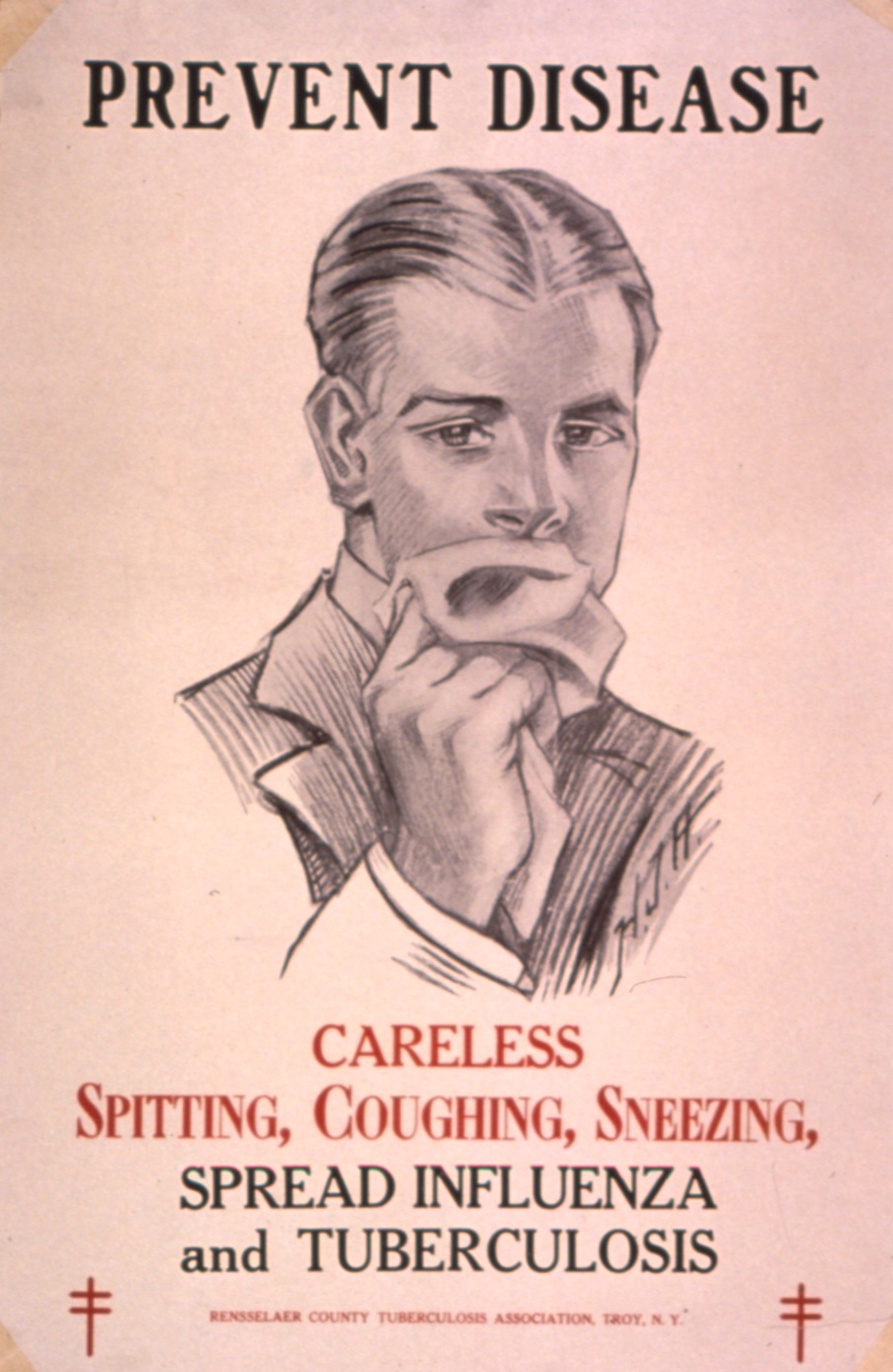

Beyond temperance, Picotte worked on public health issues in the wider community, including school hygiene, food sanitation, and efforts to combat the spread of tuberculosis. She served on the health board of the town of Walthill, and was a founding member of the Thurston County Medical Society in 1907.

Picotte was also the chair of the state health committee of the Nebraska Federation of Women's Clubs during the first decade of the 20th century. As chair, she spearheaded efforts to educate people about public health issues, particularly in the schools, believing that the key to fighting disease was education. From her time in medical school onward, she also campaigned for the building of a

Beyond temperance, Picotte worked on public health issues in the wider community, including school hygiene, food sanitation, and efforts to combat the spread of tuberculosis. She served on the health board of the town of Walthill, and was a founding member of the Thurston County Medical Society in 1907.

Picotte was also the chair of the state health committee of the Nebraska Federation of Women's Clubs during the first decade of the 20th century. As chair, she spearheaded efforts to educate people about public health issues, particularly in the schools, believing that the key to fighting disease was education. From her time in medical school onward, she also campaigned for the building of a

The issue of land allotment came up again when Picotte's husband Henry died in 1905. He left about 185 acres of land in South Dakota to her and their two sons, Pierre and Caryl, but complications had arisen in claiming and selling it. At the time of Henry's death, the land was still held in trust by the government, and in order to receive the monies from its sale, his heirs had to prove competency. Minors, such as Picotte's sons, had to have a

The issue of land allotment came up again when Picotte's husband Henry died in 1905. He left about 185 acres of land in South Dakota to her and their two sons, Pierre and Caryl, but complications had arisen in claiming and selling it. At the time of Henry's death, the land was still held in trust by the government, and in order to receive the monies from its sale, his heirs had to prove competency. Minors, such as Picotte's sons, had to have a

Doing this work, she became increasingly aware and outraged at the land fraud committed by a syndicate of men on and around the Omaha reservation. Picotte focused on the syndicate, which was made up of three white and two Omaha men who defrauded minors of their inheritances. In a bizarre twist, Picotte, who had spent much of her life proclaiming that the Omaha had the same capacity for "civilization" as any white man, wrote to the Indian Office in 1909 to say that some of her people were too incompetent to protect themselves against the fraudsters and thus needed the continued guardianship of the federal government. In 1910, she traveled to Washington, D.C. to speak with officials from the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA), and told them that though most of the Omaha were perfectly competent to manage their own affairs, the Indian Office had stifled the development of business skills and knowledge of the white world among Indians, and thus the incompetence of a minority of Omaha was, in fact, the fault of the federal government.

This argument was the product of her campaigns against the consolidation of the Omaha and Winnebago agencies, which had been suggested in 1904 and revived in 1910. Picotte had been part of a movement among the Omaha opposing this consolidation, and used letters and harshly critical newspaper articles to get her point across to the OIA bureaucracy. She argued that the unnecessary red tape created by the consolidation was nothing but an extra burden on the Omaha and was further proof that the OIA treated them like children, rather than as citizens ready to participate in a democracy. She continued to work on her community's behalf until the end of her life, though much of that seemed to be in vain, as her people lost many of their ancestral lands and became more, not less, dependent on the OIA.

Doing this work, she became increasingly aware and outraged at the land fraud committed by a syndicate of men on and around the Omaha reservation. Picotte focused on the syndicate, which was made up of three white and two Omaha men who defrauded minors of their inheritances. In a bizarre twist, Picotte, who had spent much of her life proclaiming that the Omaha had the same capacity for "civilization" as any white man, wrote to the Indian Office in 1909 to say that some of her people were too incompetent to protect themselves against the fraudsters and thus needed the continued guardianship of the federal government. In 1910, she traveled to Washington, D.C. to speak with officials from the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA), and told them that though most of the Omaha were perfectly competent to manage their own affairs, the Indian Office had stifled the development of business skills and knowledge of the white world among Indians, and thus the incompetence of a minority of Omaha was, in fact, the fault of the federal government.

This argument was the product of her campaigns against the consolidation of the Omaha and Winnebago agencies, which had been suggested in 1904 and revived in 1910. Picotte had been part of a movement among the Omaha opposing this consolidation, and used letters and harshly critical newspaper articles to get her point across to the OIA bureaucracy. She argued that the unnecessary red tape created by the consolidation was nothing but an extra burden on the Omaha and was further proof that the OIA treated them like children, rather than as citizens ready to participate in a democracy. She continued to work on her community's behalf until the end of her life, though much of that seemed to be in vain, as her people lost many of their ancestral lands and became more, not less, dependent on the OIA.

Picotte suffered for most of her life from chronic illness. In medical school, she had been bothered by trouble breathing, and after a few years working on the reservation, she was forced to take a break to recover her health in 1892, as she suffered from

Picotte suffered for most of her life from chronic illness. In medical school, she had been bothered by trouble breathing, and after a few years working on the reservation, she was forced to take a break to recover her health in 1892, as she suffered from

Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte (1865–1915) Find A Grave memorial

{{DEFAULTSORT:Picotte, Susan La Flesche 1865 births 1915 deaths 19th-century American physicians 20th-century American physicians 19th-century American women physicians 20th-century American women physicians 19th-century Native Americans 20th-century Native Americans Drexel University alumni Hampton University alumni La Flesche family Native American physicians Omaha (Native American) people People from Thurston County, Nebraska Physicians from Nebraska Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania alumni 19th-century Native American women 20th-century Native American women

public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the det ...

and for the formal, legal allotment of land to members of the Omaha tribe

The Omaha ( Omaha-Ponca: ''Umoⁿhoⁿ'') are a federally recognized Midwestern Native American tribe who reside on the Omaha Reservation in northeastern Nebraska and western Iowa, United States. There were 5,427 enrolled members as of 2012. The ...

.

Picotte was an active social reformer

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more radical social movements such as revolutionary move ...

as well as a physician. She worked to discourage drinking on the reservation where she worked as the physician, as part of the temperance movement

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting temperance or complete abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and its leaders emph ...

of the 19th century. Picotte also campaigned to prevent and treat tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

, which then had no cure, as part of a public health campaign. She also worked to help other Omaha navigate the bureaucracy of the Office of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal agency within the Department of the Interior. It is responsible for implementing federal laws and policies related to American Indians and ...

and receive the money owed to them for the sale of their land.

Early life

Susan La Flesche was born in June 1865 on theOmaha Reservation

The Omaha Reservation ( oma, Umoⁿhoⁿ tóⁿde ukʰéthiⁿ) of the federally recognized Omaha tribe is located mostly in Thurston County, Nebraska, with sections in neighboring Cuming and Burt counties, in addition to Monona County in Iowa. A ...

in eastern Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

. Her parents were culturally Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest city ...

with European and Indigenous ancestry and had lived for periods of time beyond the borders of the reservation. They married sometime in 1845–1846.

Susan’s father, Joseph La Flesche also called Iron Eye, was of Ponca

The Ponca ( Páⁿka iyé: Páⁿka or Ppáⁿkka pronounced ) are a Midwestern Native American tribe of the Dhegihan branch of the Siouan language group. There are two federally recognized Ponca tribes: the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska and the Ponca ...

and some French Canadian

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

ancestry. He was educated in St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

, but returned to the reservation as a young man. He identified culturally as Omaha. In 1853 he was adopted by Chief Big Elk, who chose him as his successor, and La Flesche became the principal leader of the Omaha tribe around 1855. Iron Eye sought to help his people by encouraging a certain amount of assimilation, particularly through the policy of land allotment, which caused some friction among the Omaha.

Susan’s mother, Mary Gale, was the daughter of Dr. John Gale, a white United States Army surgeon stationed at Fort Atkinson, and Nicomi, a woman of Omaha/Otoe

The Otoe (Chiwere: Jiwére) are a Native American people of the Midwestern United States. The Otoe language, Chiwere, is part of the Siouan family and closely related to that of the related Iowa, Missouria, and Ho-Chunk tribes.

Historically, t ...

/Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to the ...

heritage. Gale was also the stepdaughter of prominent Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

fur trader

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

and statesman Peter A. Sarpy. Like her husband, Mary Gale was identified as Omaha. Although she understood French and English, she refused to speak any language other than Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest city ...

.

Susan was the youngest of four girls, including her sisters Susette (1854–1903), Rosalie (1861–1900), and Marguerite (1862–1945). Her older half-brother Francis La Flesche

Francis La Flesche (Omaha, 1857–1932) was the first professional Native American ethnologist; he worked with the Smithsonian Institution. He specialized in Omaha and Osage cultures. Working closely as a translator and researcher with the anthro ...

, born in 1857 to her father's second wife, later became renowned as an ethnologist

Ethnology (from the grc-gre, ἔθνος, meaning 'nation') is an academic field that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology) ...

, anthropologist

An anthropologist is a person engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropology is the study of aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms and ...

and musicologist

Musicology (from Greek μουσική ''mousikē'' 'music' and -λογια ''-logia'', 'domain of study') is the scholarly analysis and research-based study of music. Musicology departments traditionally belong to the humanities, although some mu ...

(or ethnomusicologist

Ethnomusicology is the study of music from the cultural and social aspects of the people who make it. It encompasses distinct theoretical and methodical approaches that emphasize cultural, social, material, cognitive, biological, and other dim ...

), who focused on the Omaha and Osage The Osage Nation, a Native American tribe in the United States, is the source of most other terms containing the word "osage".

Osage can also refer to:

* Osage language, a Dhaegin language traditionally spoken by the Osage Nation

* Osage (Unicode b ...

cultures. As she grew, La Flesche learned the traditions of her heritage, but her parents felt certain rituals would be detrimental in the white world. They did not give their youngest daughter an Omaha name and prevented her from receiving traditional tattoos across her forehead. She spoke Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest city ...

with her parents (especially with her mother), but her father and oldest sister Susette encouraged her to speak English with her sisters, so that she would be fluent in both languages.

As a child, LaFlesche witnessed a sick Indian woman die after a white doctor refused to treat her. She later credited this tragedy as her inspiration to train as a physician, so she could provide care for the people she lived with on the Omaha Reservation.

As a child, LaFlesche witnessed a sick Indian woman die after a white doctor refused to treat her. She later credited this tragedy as her inspiration to train as a physician, so she could provide care for the people she lived with on the Omaha Reservation.

Education

Early education

La Flesche's education began early, at the mission school on the reservation. It was run first by thePresbyterians

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

and then by the Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

, after the enactment of President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

's " Peace Policy" in 1869. The reservation school was a boarding school

A boarding school is a school where pupils live within premises while being given formal instruction. The word "boarding" is used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals. As they have existed for many centuries, and now exten ...

where Native children were taught the practices of European Americans to assimilate them into white society.

After several years at the mission school, La Flesche left the reservation for Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

, New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

, where she studied at the Elizabeth Institute for two and a half years. She returned to the reservation in 1882 and taught at the agency school. She left again to study at the Hampton Institute

Hampton University is a private, historically black, research university in Hampton, Virginia. Founded in 1868 as Hampton Agricultural and Industrial School, it was established by Black and White leaders of the American Missionary Association af ...

in Hampton

Hampton may refer to:

Places Australia

*Hampton bioregion, an IBRA biogeographic region in Western Australia

*Hampton, New South Wales

*Hampton, Queensland, a town in the Toowoomba Region

*Hampton, Victoria

Canada

*Hampton, New Brunswick

*Hamp ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, from 1884 to 1886. It had been established as an historically black college

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African-American community. Mo ...

after the American Civil War, but had become a destination also for Native American students.

La Flesche attended Hampton with her sister Marguerite, her stepbrother Cary, and ten other Omaha children. The girls learned housewifery skills and the boys learned vocational skills as part of the practical skills promoted at the school. While La Flesche was a student at the Hampton Institute, she became romantically involved with a young Sioux man named Thomas Ikinicapi. She referred to him affectionately as "T.I.", but broke off her relationship with him before graduating from Hampton. La Flesche graduated from Hampton on May 20, 1886, where she was class salutatorian. She was also awarded the Demorest prize, which is given to the graduating senior who receives the highest examination scores during the junior year.

Female graduates of the Hampton Institute were generally encouraged to teach or to return to their reservations and become Christian wives and mothers. La Flesche decided in 1886 to apply to medical school

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, M ...

.

Medical school

healers

Alternative medicine is any practice that aims to achieve the healing effects of medicine despite lacking biological plausibility, testability, repeatability, or evidence from clinical trials. Complementary medicine (CM), complementary and alte ...

in Omaha Indian society, it was uncommon for any Victorian-era woman in the United States to go to medical school. In the late 19th century, only a few medical schools accepted women.

La Flesche was accepted at the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania

The Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP) was founded in 1850, and was the second medical institution in the world established to train women in medicine to earn the M.D. degree. The New England Female Medical College had been established ...

(WMCP), which had been established in 1850 as one of the few medical schools on the East Coast for the education of women. Medical school was expensive, however, and she could not afford it on her own. For help, she turned to family friend Alice Fletcher

Alice Cunningham Fletcher (March 15, 1838 in HavanaApril 6, 1923 in Washington, D.C.) was an American ethnologist, anthropologist, and social scientist who studied and documented American Indian culture.

Early life and education

Not much is ...

, an ethnographer

Ethnography (from Greek ''ethnos'' "folk, people, nation" and ''grapho'' "I write") is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. Ethnography explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject o ...

from Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

who had a broad network of contacts within women's reform organizations. La Flesche had previously helped nurse Fletcher back to health following a flareup of inflammatory rheumatism.

Fletcher encouraged La Flesche to appeal to the Connecticut Indian Association, a local auxiliary of the Women's National Indian Association

The Women's National Indian Association (WNIA) was founded in 1879 by a group of United States, American women, including educators and activists Mary Bonney and Amelia Stone Quinton. Bonney and Quinton united in the 1880s against the encroachment ...

(WNIA). The WNIA sought to "civilize" the Indians by encouraging Victorian values of domesticity among Indian women, and sponsored field matrons

Matron is the job title of a very senior or the chief nurse in several countries, including the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland and other Commonwealth countries and former colonies.

Etymology

The chief nurse, in other words the person ...

whose task was to teach Native American women "cleanliness" and "godliness."

La Flesche, in writing to the Connecticut Indian Association, had described her desire to enter the homes of her people as a physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

and teach them hygiene

Hygiene is a series of practices performed to preserve health.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), "Hygiene refers to conditions and practices that help to maintain health and prevent the spread of diseases." Personal hygiene refer ...

as well as curing their ills; this was in line with the Victorian virtues of domesticity which the Association wanted to encourage. The Association sponsored La Flesche's medical school expenses, and also paid for her housing, books and other supplies. She is considered the first person to receive aid for professional education in the United States. The Association requested that she remain single during her time at medical school and for several years after her graduation, in order to focus on her practice.

At the WMCP, La Flesche studied

At the WMCP, La Flesche studied chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

, anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its ...

, physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical ...

, histology

Histology,

also known as microscopic anatomy or microanatomy, is the branch of biology which studies the microscopic anatomy of biological tissues. Histology is the microscopic counterpart to gross anatomy, which looks at larger structures vis ...

, pharmaceutical science

Pharmacy is the science and practice of discovering, producing, preparing, dispensing, reviewing and monitoring medications, aiming to ensure the safe, effective, and affordable use of medicines. It is a miscellaneous science as it links healt ...

, obstetrics

Obstetrics is the field of study concentrated on pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. As a medical specialty, obstetrics is combined with gynecology under the discipline known as obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN), which is a surgi ...

, and general medicine, and, like her peers, did clinical work at facilities in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

alongside students from other colleges, both male and female. While attending medical school, La Flesche changed her appearance. She began to dress like her white classmates and wore her hair in a bun on the top of her head as they did.

After La Flesche's second year in medical school, she had to return home to help her family, many of whom had fallen ill due to a measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

outbreak. It could be a serious disease for both adults and children. During the rest of her schooling, she would write letters back home giving medical advice.

She was valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title for the highest-performing student of a graduating class of an academic institution.

The valedictorian is commonly determined by a numerical formula, generally an academic institution's grade point average (GPA ...

and graduated at the top of her class on March 14, 1889, after a rigorous three-year course of study.

In June 1889, La Flesche applied for the position of government physician at the Omaha Agency Indian School; she was offered the position less than two months later. After her graduation, she went on a speaking tour at the request of the Connecticut Indian Association, assuring white audiences that Indians could benefit from white civilization.

She maintained her ties with the Association after medical school. They appointed her as a medical missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

to the Omaha after graduation, and the Association funded purchase of medical instruments and books for her during her early years of practicing medicine in Nebraska.

Medical practice

La Flesche returned to the Omaha reservation in 1889 to take up her position as the physician at the government boarding school on the reservation, run by the

La Flesche returned to the Omaha reservation in 1889 to take up her position as the physician at the government boarding school on the reservation, run by the Office of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal agency within the Department of the Interior. It is responsible for implementing federal laws and policies related to American Indians and ...

. There she was responsible for teaching the students about hygiene

Hygiene is a series of practices performed to preserve health.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), "Hygiene refers to conditions and practices that help to maintain health and prevent the spread of diseases." Personal hygiene refer ...

and keeping them healthy.

Though she was not obligated to care for the broader community, the school was closer to many people than the official reservation agency, and La Flesche found herself caring for many members of the community as well as for the children of the school. La Flesche often had 20-hour workdays and was responsible for over 1,200 people.

From her office in a corner of the schoolyard, with the supplies provided by the Connecticut Indian Association, she helped people with their health but also with more mundane tasks, such as writing letters and translating

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transl ...

official documents.

She was widely trusted in the community, making house calls and caring for patients sick with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

, influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptoms ...

, cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

, dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

, and trachoma

Trachoma is an infectious disease caused by bacterium ''Chlamydia trachomatis''. The infection causes a roughening of the inner surface of the eyelids. This roughening can lead to pain in the eyes, breakdown of the outer surface or cornea of ...

.

Her first office, which was a mere 12 by 16 feet, doubled as a community meeting place.

For several years, she traveled the reservation caring for patients, on a government salary of $500.00 per year, in addition to the $250 from the Women's National Indian Association for her work as a medical missionary.

In December 1892, she became very sick, and was bedridden for several weeks. She was forced to take time off in 1893 to care for her ailing mother and also to restore her own health. She resigned in 1893 to take care of her dying mother, putting familial obligations before her public work.

In 1894, La Flesche met and became engaged

An engagement or betrothal is the period of time between the declaration of acceptance of a marriage proposal and the marriage itself (which is typically but not always commenced with a wedding). During this period, a couple is said to be ''fi ...

to Henry Picotte, a Sioux Indian from the Yankton agency. He had been married before and divorced

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganizing of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving the ...

his wife. Many of La Flesche's friends and family were surprised at the romance, but the two were married in June 1894.

Picotte and her husband had two sons: Caryl, born in 1895 or 1896, and Pierre, born in early 1898. Picotte continued to practice medicine after the birth of her children, depending on the support of her husband to make that possible. This was unusual for Victorian-era women, who were generally expected to stay home after marriage in order to be full-time mothers. Picotte's practice treated both Omaha and white patients in the town of Bancroft and surrounding communities. If necessary, Picotte would even take her children on house calls with her sometimes.

Public health reforms

Temperance

In addition to caring for her people's immediate medical problems, Picotte sought to educate her community aboutpreventive medicine

Preventive healthcare, or prophylaxis, consists of measures taken for the purposes of disease prevention.Hugh R. Leavell and E. Gurney Clark as "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting physical and mental hea ...

and other public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the det ...

issues, including temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

. Alcoholism was a serious problem on the Omaha reservation, and a personal one for Picotte: her husband Henry was an alcoholic. Disreputable whites used alcohol to take advantage of Omahas while making land deals. Picotte, as reservation physician and a prominent member of the community, was well aware of the damage such practices caused. La Flesche supported measures such as coercion and punishment to dissuade individuals from alcohol consumption within the Omaha community. Under her father's rule, a secret police system was instilled which supported corporal punishment to discipline those who consumed alcohol.

Picotte campaigned against alcohol, giving lectures

A lecture (from Latin ''lēctūra'' “reading” ) is an oral presentation intended to present information or teach people about a particular subject, for example by a university or college teacher. Lectures are used to convey critical inform ...

about the virtues of temperance, and embracing coercive efforts as well, such as prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

. In the early 1890s, she campaigned for a prohibition law in Thurston County, which did not pass, in part because of unscrupulous liquor dealers who took advantage of illiterate

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in written form in some specific context of use. In other words, hum ...

Omahas by handing them ballot

A ballot is a device used to cast votes in an election and may be found as a piece of paper or a small ball used in secret voting. It was originally a small ball (see blackballing) used to record decisions made by voters in Italy around the 16t ...

tickets with "Against Prohibition" on them. Other sources claim that the Indian men were bribed with liquor from white men. Later, she lobbied

In politics, lobbying, persuasion or interest representation is the act of lawfully attempting to influence the actions, policies, or decisions of government officials, most often legislators or members of regulatory agencies. Lobbying, which ...

for the Meilklejohn Bill, which would outlaw the sale of alcohol to any recipient of allotted land whose property was still held in trust

Trust often refers to:

* Trust (social science), confidence in or dependence on a person or quality

It may also refer to:

Business and law

* Trust law, a body of law under which one person holds property for the benefit of another

* Trust (bus ...

by the government. The Meiklejohn Bill became law in January 1897 but proved nearly impossible to enforce.

Picotte continued to fight against alcohol for the rest of her life, and when the peyote religion

The Native American Church (NAC), also known as Peyotism and Peyote Religion, is a Native American religion that teaches a combination of traditional Native American beliefs and Christianity, with sacramental use of the entheogen peyote. The re ...

arrived on the Omaha reservation in the early 1900s, she gradually accepted it as a means of fighting alcoholism, as many members of the peyote religion were able to reconnect with their spiritual traditions and reject alcoholic ambitions.

Sanitation, tuberculosis, and other public health reforms

Beyond temperance, Picotte worked on public health issues in the wider community, including school hygiene, food sanitation, and efforts to combat the spread of tuberculosis. She served on the health board of the town of Walthill, and was a founding member of the Thurston County Medical Society in 1907.

Picotte was also the chair of the state health committee of the Nebraska Federation of Women's Clubs during the first decade of the 20th century. As chair, she spearheaded efforts to educate people about public health issues, particularly in the schools, believing that the key to fighting disease was education. From her time in medical school onward, she also campaigned for the building of a

Beyond temperance, Picotte worked on public health issues in the wider community, including school hygiene, food sanitation, and efforts to combat the spread of tuberculosis. She served on the health board of the town of Walthill, and was a founding member of the Thurston County Medical Society in 1907.

Picotte was also the chair of the state health committee of the Nebraska Federation of Women's Clubs during the first decade of the 20th century. As chair, she spearheaded efforts to educate people about public health issues, particularly in the schools, believing that the key to fighting disease was education. From her time in medical school onward, she also campaigned for the building of a hospital

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emerge ...

on the reservation. It was finally completed in 1913 and later named in her honor. This was the first privately funded hospital on a reservation.

Her most important crusade was against tuberculosis, which killed hundreds of Omaha, including her husband Henry in 1905. In 1907, she wrote to the Indian Office to try to persuade them to help, but they turned her down, blaming a lack of funding. Because there was not yet a cure available, Picotte advocated cleanliness, fresh air, and the eradication of houseflies

The housefly (''Musca domestica'') is a fly of the suborder Cyclorrhapha. It is believed to have evolved in the Cenozoic Era, possibly in the Middle East, and has spread all over the world as a commensal of humans. It is the most common f ...

, which were believed to be major carriers of TB.

Picotte's willingness to engage in political action

In sociology, social action, also known as Weberian social action, is an act which takes into account the actions and reactions of individuals (or ' agents'). According to Max Weber, "Action is 'social' insofar as its subjective meaning takes ...

carried over into areas other than public health. After the death of her husband, she became increasingly active in the campaigns against extenting the trust period for the Omaha. She was a delegate to the Secretary of the Interior, protesting changes in the supervision of the Omaha.

Political involvement and the issue of allotment

Struggles with inheritance

The issue of land allotment came up again when Picotte's husband Henry died in 1905. He left about 185 acres of land in South Dakota to her and their two sons, Pierre and Caryl, but complications had arisen in claiming and selling it. At the time of Henry's death, the land was still held in trust by the government, and in order to receive the monies from its sale, his heirs had to prove competency. Minors, such as Picotte's sons, had to have a

The issue of land allotment came up again when Picotte's husband Henry died in 1905. He left about 185 acres of land in South Dakota to her and their two sons, Pierre and Caryl, but complications had arisen in claiming and selling it. At the time of Henry's death, the land was still held in trust by the government, and in order to receive the monies from its sale, his heirs had to prove competency. Minors, such as Picotte's sons, had to have a legal guardian

A legal guardian is a person who has been appointed by a court or otherwise has the legal authority (and the corresponding duty) to make decisions relevant to the personal and property interests of another person who is deemed incompetent, call ...

who could prove competency on their behalf.

The process of gaining the monies owed to them was long and arduous, and Picotte had to send letter after letter to the Indian Office to get them to recognize her as a competent individual in order to receive her portion of the inheritance, which R. J. Taylor, the agent on the Yankton reservation, finally granted to her in 1907, nearly two years after her husband's death. However, gaining her children's inheritance proved to be a harder struggle. Another relative, Peter Picotte, was the legal guardian of her sons' land, because it was in another state, but he refused to consent to the sale of the land.

Picotte responded by bombarding Commissioner Leupp, head of the Indian Office, with letters, painting Peter Picotte as a drunk and R. J. Taylor as intransigent and incompetent, while making a case for herself as the best manager of her sons' money. This time, her letters received attention, and the Indian Office responded to her within a week of the original letters, informing her that Taylor had been ordered to ignore Peter Picotte's objections.

Picotte invested this money in rental properties, and was able to use that income to support herself and her sons. This was not the end of her fights with the bureaucracy of the federal government, however. Her children inherited land from some Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota language, Dakota: Help:IPA, /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes and First Nations in Canada, First Nations peoples in North America. The ...

relatives of her husband, and she entered into another battle with the bureaucracy

The term bureaucracy () refers to a body of non-elected governing officials as well as to an administrative policy-making group. Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments staffed with non-elected offi ...

, which ended positively in 1908.

Action for the community

Picotte's struggles with the bureaucracy of allotment continued on behalf of other members of her community. In her position as a doctor, Picotte had gained the trust of her community, and her role as a localleader

Leadership, both as a research area and as a practical skill, encompasses the ability of an individual, group or organization to "lead", influence or guide other individuals, teams, or entire organizations. The word "leadership" often gets vi ...

had expanded from letter writer/interpreter to defender of Omaha land interests. She sought to help other Omaha who wanted to sell their lands and gain control of the monies owed to them, and she also tried to help resolve situations where whites took advantage of Indians who chose to lease land.

Illness, death, and legacy

Picotte suffered for most of her life from chronic illness. In medical school, she had been bothered by trouble breathing, and after a few years working on the reservation, she was forced to take a break to recover her health in 1892, as she suffered from

Picotte suffered for most of her life from chronic illness. In medical school, she had been bothered by trouble breathing, and after a few years working on the reservation, she was forced to take a break to recover her health in 1892, as she suffered from chronic pain

Chronic pain is classified as pain that lasts longer than three to six months. In medicine, the distinction between Acute (medicine), acute and Chronic condition, chronic pain is sometimes determined by the amount of time since onset. Two commonly ...

in her neck, head, and ears. She recovered but became ill again in 1893, after a fall from her horse left her with significant internal injuries. Over time, Picotte's condition caused her to go deaf.

As Picotte aged, her health declined, and by the time that the new reservation hospital was built in Walthill in 1913, she was too frail to be its sole administrator. By early March 1915, she was suffering greatly and died of bone cancer

A bone tumor is an abnormal growth of tissue in bone, traditionally classified as noncancerous (benign) or cancerous (malignant). Cancerous bone tumors usually originate from a cancer in another part of the body such as from lung, breast, thyro ...

on September 18, 1915. The next day, services by both the Presbyterian Church as well as the Amethyst Chapter of the Order of the Eastern Star

The Order of the Eastern Star is a Freemasonry, Masonic List of fraternal auxiliaries and side degrees, appendant Masonic bodies, body open to both men and women. It was established in by lawyer and educator Rob Morris (Freemason), Rob Morris, ...

were performed. She is buried in Bancroft Cemetery, Bancroft, Nebraska

Bancroft is a village in Cuming County, Nebraska, United States. The population was 495 at the 2010 census.

John Neihardt, who later became Nebraska's poet laureate, lived in Bancroft for twenty years and wrote many of his works there. His stud ...

near her husband, father, mother, sisters and half-brother.

Picotte's sons went on to live full lives. Caryl Picotte made a career in the United States Army and served in World War II, eventually settling in El Cajon, California

El Cajon ( , ; Spanish: El Cajón, meaning "the box") is a city in San Diego County, California, United States, east of downtown San Diego. The city takes its name from Rancho El Cajón, which was in turn named for the box-like shape of the va ...

. Pierre Picotte lived in Walthill, Nebraska, for most of his life and raised a family of three children.

In her career, Picotte served over 1,300 patients in a 450 square mile area.

Tributes

The reservation hospital in Walthill, Nebraska, now a community center, is named after Picotte and was declared aNational Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

in 1993. The hospital has also been named as one of the 11 most endangered places of 2018 by the National Trust. Work is underway to raise funds for its restoration.

An elementary school in western Omaha Nebraska is named after Picotte.

On June 17, 2017, the 152nd anniversary of her birth, Google

Google LLC () is an American multinational technology company focusing on search engine technology, online advertising, cloud computing, computer software, quantum computing, e-commerce, artificial intelligence, and consumer electronics. ...

released a Google Doodle

A Google Doodle is a special, temporary alteration of the logo on Google's homepages intended to commemorate holidays, events, achievements, and notable historical figures. The first Google Doodle honored the 1998 edition of the long-running an ...

honoring Picotte.

In 2018, a bust of Picotte was dedicated at the Martin Luther King Jr. Transportation Center in Sioux City.

In 2019, a statue of La Flesche was dedicated as part of Hampton University's Legacy Park.

On October 11, 2021, Nebraska's first officially recognized Indigenous Peoples’ Day, a bronze sculpture of Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte was unveiled by her descendants on Lincoln’s Centennial Mall. Benjamin Victor (sculptor)

Benjamin Matthew Victor (b. Taft, California, January 16, 1979) is an American sculptor living and working in Boise, Idaho. He is the only living artist to have three works in the National Statuary Hall in the United States Capitol. He is curre ...

created the Picotte bronze. He is the same artist who created the Chief Standing Bear sculpture that now sits on Centennial Mall, and another version of it stands in Statuary Hall in Washington D.C.

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * *External links

Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte (1865–1915) Find A Grave memorial

{{DEFAULTSORT:Picotte, Susan La Flesche 1865 births 1915 deaths 19th-century American physicians 20th-century American physicians 19th-century American women physicians 20th-century American women physicians 19th-century Native Americans 20th-century Native Americans Drexel University alumni Hampton University alumni La Flesche family Native American physicians Omaha (Native American) people People from Thurston County, Nebraska Physicians from Nebraska Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania alumni 19th-century Native American women 20th-century Native American women