Sunday Times Golden Globe Race on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Sunday Times'' Golden Globe Race was a non-stop, single-handed,

The ''Sunday Times'' did not want to sponsor someone for the first non-stop solo circumnavigation only to have them beaten by another sailor, so the paper hit upon the idea of a sponsored race, which would cover all the sailors setting off that year. To circumvent the possibility of a non-entrant completing his voyage first and scooping the story, they made entry automatic: anyone sailing single-handed around the world that year would be considered in the race.

This still left them with a dilemma in terms of the prize. A race for the fastest time around the world was a logical subject for a prize, but there would obviously be considerable interest in the ''first'' person to complete a non-stop circumnavigation, and there was no possibility of persuading the possible candidates to wait for a combined start. The ''Sunday Times'' therefore decided to award two prizes: the ''Golden Globe'' trophy for the first person to sail single-handed, non-stop around the world; and a £5,000 prize () for the fastest time.

This automatic entry provision had the drawback that the race organisers could not vet entrants for their ability to take on this challenge safely. This was in contrast to the ''OSTAR'', for example, which in the same year required entrants to complete a solo 500-nautical mile (930 km) qualifying passage. The one concession to safety was the requirement that all competitors must start between 1 June and 31 October, in order to pass through the

The ''Sunday Times'' did not want to sponsor someone for the first non-stop solo circumnavigation only to have them beaten by another sailor, so the paper hit upon the idea of a sponsored race, which would cover all the sailors setting off that year. To circumvent the possibility of a non-entrant completing his voyage first and scooping the story, they made entry automatic: anyone sailing single-handed around the world that year would be considered in the race.

This still left them with a dilemma in terms of the prize. A race for the fastest time around the world was a logical subject for a prize, but there would obviously be considerable interest in the ''first'' person to complete a non-stop circumnavigation, and there was no possibility of persuading the possible candidates to wait for a combined start. The ''Sunday Times'' therefore decided to award two prizes: the ''Golden Globe'' trophy for the first person to sail single-handed, non-stop around the world; and a £5,000 prize () for the fastest time.

This automatic entry provision had the drawback that the race organisers could not vet entrants for their ability to take on this challenge safely. This was in contrast to the ''OSTAR'', for example, which in the same year required entrants to complete a solo 500-nautical mile (930 km) qualifying passage. The one concession to safety was the requirement that all competitors must start between 1 June and 31 October, in order to pass through the

Blyth and Knox-Johnston were well down the Atlantic by this time. Knox-Johnston, the experienced seaman, was enjoying himself, but ''Suhaili'' had problems with leaking seams near the

Blyth and Knox-Johnston were well down the Atlantic by this time. Knox-Johnston, the experienced seaman, was enjoying himself, but ''Suhaili'' had problems with leaking seams near the

By mid-November Crowhurst was already having problems with his boat. Hastily built, the boat was already showing signs of being unprepared, and in the rush to depart, Crowhurst had left behind crucial repair materials. On 15 November, he made a careful appraisal of his outstanding problems and of the risks he would face in the

By mid-November Crowhurst was already having problems with his boat. Hastily built, the boat was already showing signs of being unprepared, and in the rush to depart, Crowhurst had left behind crucial repair materials. On 15 November, he made a careful appraisal of his outstanding problems and of the risks he would face in the

By January, concern was growing for Knox-Johnston. He was having problems with his radio transmitter and nothing had been heard since he had passed south of New Zealand. He was actually making good progress, rounding

By January, concern was growing for Knox-Johnston. He was having problems with his radio transmitter and nothing had been heard since he had passed south of New Zealand. He was actually making good progress, rounding  As he sailed past the

As he sailed past the

Crowhurst re-opened radio contact on 10 April, reporting himself to be "heading" towards the

Crowhurst re-opened radio contact on 10 April, reporting himself to be "heading" towards the

'Crowhurst'

a 9-song

Download

The Sunday Times (UK) Golden Globe Race

round-the-world

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical body (e.g. a planet or moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circumnavigation of the Earth was the Magel ...

yacht race

Yacht racing is a Sailing (sport), sailing sport involving sailing yachts and larger sailboats, as distinguished from dinghy racing, which involves open boats. It is composed of multiple yachts, in direct competition, racing around a course marke ...

, held in 1968–1969, and was the first round-the-world yacht race. The race was controversial due to the failure of most competitors to finish the race and because of the apparent suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

of one entrant; however, it ultimately led to the founding of the ''BOC Challenge The Velux 5 Oceans Race was a round-the-world single-handed sailing, single-handed yacht racing, yacht race, sailed in Race stage, stages, managed by Clipper Ventures since 2000. Its most recent name comes from its main sponsor Velux. Originally kno ...

'' and ''Vendée Globe

-->

The Vendée Globe is a single-handed (solo) non-stop round the world yacht race. The race was founded by Philippe Jeantot in 1989, and since 1992 has taken place every four years. It is named after the Département of Vendée, in France, w ...

'' round-the-world races, both of which continue to be successful and popular.

The race was sponsored by the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

''Sunday Times'' newspaper and was designed to capitalise on a number of individual round-the-world voyages which were already being planned by various sailors; for this reason, there were no qualification requirements, and competitors were offered the opportunity to join and permitted to start at any time between 1 June and 31 October 1968. The Golden Globe trophy

A trophy is a tangible, durable reminder of a specific achievement, and serves as a recognition or evidence of merit. Trophies are often awarded for sporting events, from youth sports to professional level athletics. In many sports medals (or, in ...

was offered to the first person to complete an unassisted, non-stop single-handed circumnavigation of the world via the great capes

In sailing, the great capes are three major capes of the continents in the Southern Ocean—Africa's Cape of Good Hope, Australia's Cape Leeuwin, and South America's Cape Horn.

Sailing

The traditional clipper route followed the winds of the ro ...

, and a separate £5,000 prize was offered for the fastest single-handed circumnavigation.

Nine sailors started the race; four retired before leaving the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

. Of the five remaining, Chay Blyth

Sir Charles Blyth (born 14 May 1940), known as Chay Blyth, is a Scottish yachtsman and rower. He was the first person to sail single-handed non-stop westwards around the world (1971), on a 59-foot boat called '' British Steel''.

Early life

B ...

, who had set off with absolutely no sailing experience, sailed past the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

before retiring; Nigel Tetley

Nigel Tetley (8 February 1924 – 2 February 1972) was a British sailor who was the first person to circumnavigate the world solo in a trimaran.''A Voyage for Madmen'', by Peter Nichols; pages 32–33. Harper Collins, 2001.

The race

A nativ ...

sank with to go while leading; Donald Crowhurst

Donald Charles Alfred Crowhurst (1932 – July 1969) was a British businessman and amateur sailor who disappeared while competing in the ''Sunday Times'' Golden Globe Race, a single-handed, round-the-world yacht race. Soon after he started th ...

, who, in desperation, attempted to fake a round-the-world voyage to avoid financial ruin, began to show signs of mental illness, and then committed suicide; and Bernard Moitessier

Bernard Moitessier (April 10, 1925 – June 16, 1994) was a French sailor, most notable for his participation in the 1968 ''Sunday Times'' Golden Globe Race, the first non-stop, singlehanded, round the world yacht race. With the fastest circumna ...

, who rejected the philosophy behind a commercialised competition, abandoned the race while in a strong position to win and kept sailing non-stop until he reached Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

after circling the globe one and a half times. Robin Knox-Johnston

Sir William Robert Patrick Knox-Johnston (born 17 March 1939) is a British sailor. In 1969, he became the first person to perform a single-handed non-stop circumnavigation of the globe. Along with Sir Peter Blake, he won the second Jules Vern ...

was the only entrant to complete the race, becoming the first man to sail single-handed and non-stop around the world. He was awarded both prizes, and later donated the £5,000 to a fund supporting Crowhurst's family.

Genesis of the race

Long-distancesingle-handed sailing

The sport and practice of single-handed sailing or solo sailing is sailing with only one crewmember (i.e., only one person on board the vessel). The term usually refers to ocean and long-distance sailing and is used in competitive sailing and am ...

has its beginnings in the nineteenth century, when a number of sailors made notable single-handed crossings of the Atlantic. The first single-handed circumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical object, astronomical body (e.g. a planet or natural satellite, moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circ ...

of the world was made by Joshua Slocum

Joshua Slocum (February 20, 1844 – on or shortly after November 14, 1909) was the first person to sail single-handedly around the world. He was a Nova Scotian-born, naturalised American seaman and adventurer, and a noted writer. In 1900 he wr ...

, between 1895 and 1898, and many sailors have since followed in his wake, completing leisurely circumnavigations with numerous stopovers. However, the first person to tackle a single-handed circumnavigation as a speed challenge was Francis Chichester

Sir Francis Charles Chichester KBE (17 September 1901 – 26 August 1972) was a British businessman, pioneering aviator and solo sailor.

He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for becoming the first person to sail single-handed around the worl ...

, who, in 1960, had won the inaugural ''Observer Single-handed Trans-Atlantic Race

The Single-handed Trans-Atlantic Race (STAR) is an east-to-west yacht race across the North Atlantic. When inaugurated in 1960, it was the first single-handed ocean yacht race; it is run from Plymouth in England to Newport, Rhode Island in ...

'' (''OSTAR'').

In 1966, Chichester set out to sail around the world by the clipper route

The clipper route was the traditional route derived from the Brouwer Route and sailed by clipper ships between Europe and the Far East, Australia and New Zealand. The route ran from west to east through the Southern Ocean, to make use of the st ...

, starting and finishing in England with a stop in Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

, in an attempt to beat the speed records of the clipper ships

A clipper was a type of mid-19th-century Merchant ship, merchant Sailing ship, sailing vessel, designed for speed. Clippers were generally narrow for their length, small by later 19th century standards, could carry limited bulk freight, and had ...

in a small boat. His voyage was a great success, as he set an impressive round-the-world time of nine months and one daywith 226 days of sailing timeand, soon after his return to England on 28 May 1967, was knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

ed by Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. She was queen ...

. Even before his return, however, a number of other sailors had turned their attention to the next logical challengea ''non-stop'' single-handed circumnavigation of the world.

Plans laid

In March 1967, a 28-year-old British merchant marine officer,Robin Knox-Johnston

Sir William Robert Patrick Knox-Johnston (born 17 March 1939) is a British sailor. In 1969, he became the first person to perform a single-handed non-stop circumnavigation of the globe. Along with Sir Peter Blake, he won the second Jules Vern ...

, realised that a non-stop solo circumnavigation was "about all there's left to do now". Knox-Johnston had a wooden ketch

A ketch is a two- masted sailboat whose mainmast is taller than the mizzen mast (or aft-mast), and whose mizzen mast is stepped forward of the rudder post. The mizzen mast stepped forward of the rudder post is what distinguishes the ketch fr ...

, '' Suhaili'', which he and some friends had built in India to the William Atkin ''Eric'' design; two of the friends had then sailed the boat to South Africa, and in 1966 Knox-Johnston had single-handedly sailed her the remaining to London.

Knox-Johnston was determined that the first person to make a single-handed non-stop circumnavigation should be British, and he decided that he would attempt to achieve this feat. To fund his preparations he went looking for sponsorship from Chichester's sponsor, the British ''Sunday Times''. The ''Sunday Times'' was by this time interested in being associated with a successful non-stop voyage but decided that, of all the people rumoured to be preparing for a voyage, Knox-Johnston and his small wooden ketch were the least likely to succeed. Knox-Johnston finally arranged sponsorship from the ''Sunday Mirror''.

Several other sailors were interested. Bill King

Wilbur "Bill" King (October 6, 1927 – October 18, 2005) was an American sports announcer. In 2016, the National Baseball Hall of Fame named King recipient of the 2017 Ford C. Frick Award, the highest honor for American baseball broadcasters.

...

, a former Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

submarine commander, built a junk-rigged schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

, ''Galway Blazer II'', designed for heavy conditions. He was able to secure sponsorship from the ''Express'' newspapers. John Ridgway and Chay Blyth

Sir Charles Blyth (born 14 May 1940), known as Chay Blyth, is a Scottish yachtsman and rower. He was the first person to sail single-handed non-stop westwards around the world (1971), on a 59-foot boat called '' British Steel''.

Early life

B ...

, a British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

captain and sergeant, had rowed a boat across the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

in 1966. They independently decided to attempt the non-stop sail, but despite their rowing achievement were hampered by a lack of sailing experience. They both made arrangements to get boats, but ended up with entirely unsuitable vessels, boats designed for cruising protected waters and too lightly built for Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is regarded as the second-small ...

conditions. Ridgway managed to secure sponsorship from ''The People'' newspaper.

One of the most serious sailors considering a non-stop circumnavigation in late 1967 was the French sailor and author Bernard Moitessier

Bernard Moitessier (April 10, 1925 – June 16, 1994) was a French sailor, most notable for his participation in the 1968 ''Sunday Times'' Golden Globe Race, the first non-stop, singlehanded, round the world yacht race. With the fastest circumna ...

. Moitessier had a custom-built steel ketch, ''Joshua'', named after Slocum, in which he and his wife Françoise had sailed from France to Tahiti. They had then sailed her home again by way of Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramírez ...

, simply because they wanted to go home quickly to see their children. He had already achieved some recognition based on two successful books which he had written on his sailing experiences. However, he was disenchanted with the material aspect of his famehe believed that by writing his books for quick commercial success he had sold out what was for him an almost spiritual experience. He hit upon the idea of a non-stop circumnavigation as a new challenge, which would be the basis for a new and better book.

The birth of the race

By January 1968, word of all these competing plans was spreading. The ''Sunday Times'', which had profited to an unexpected extent from its sponsorship of Chichester, wanted to get involved with the first non-stop circumnavigation, but had the problem of selecting the sailor most likely to succeed. King and Ridgway, two likely candidates, already had sponsorship, and there were several other strong candidates preparing. "Tahiti" Bill Howell, an Australian cruising sailor, had made a good performance in the 1964 ''OSTAR'', Moitessier was also considered a strong contender, and there may have been other potential circumnavigators already making preparations. The ''Sunday Times'' did not want to sponsor someone for the first non-stop solo circumnavigation only to have them beaten by another sailor, so the paper hit upon the idea of a sponsored race, which would cover all the sailors setting off that year. To circumvent the possibility of a non-entrant completing his voyage first and scooping the story, they made entry automatic: anyone sailing single-handed around the world that year would be considered in the race.

This still left them with a dilemma in terms of the prize. A race for the fastest time around the world was a logical subject for a prize, but there would obviously be considerable interest in the ''first'' person to complete a non-stop circumnavigation, and there was no possibility of persuading the possible candidates to wait for a combined start. The ''Sunday Times'' therefore decided to award two prizes: the ''Golden Globe'' trophy for the first person to sail single-handed, non-stop around the world; and a £5,000 prize () for the fastest time.

This automatic entry provision had the drawback that the race organisers could not vet entrants for their ability to take on this challenge safely. This was in contrast to the ''OSTAR'', for example, which in the same year required entrants to complete a solo 500-nautical mile (930 km) qualifying passage. The one concession to safety was the requirement that all competitors must start between 1 June and 31 October, in order to pass through the

The ''Sunday Times'' did not want to sponsor someone for the first non-stop solo circumnavigation only to have them beaten by another sailor, so the paper hit upon the idea of a sponsored race, which would cover all the sailors setting off that year. To circumvent the possibility of a non-entrant completing his voyage first and scooping the story, they made entry automatic: anyone sailing single-handed around the world that year would be considered in the race.

This still left them with a dilemma in terms of the prize. A race for the fastest time around the world was a logical subject for a prize, but there would obviously be considerable interest in the ''first'' person to complete a non-stop circumnavigation, and there was no possibility of persuading the possible candidates to wait for a combined start. The ''Sunday Times'' therefore decided to award two prizes: the ''Golden Globe'' trophy for the first person to sail single-handed, non-stop around the world; and a £5,000 prize () for the fastest time.

This automatic entry provision had the drawback that the race organisers could not vet entrants for their ability to take on this challenge safely. This was in contrast to the ''OSTAR'', for example, which in the same year required entrants to complete a solo 500-nautical mile (930 km) qualifying passage. The one concession to safety was the requirement that all competitors must start between 1 June and 31 October, in order to pass through the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is regarded as the second-small ...

in summer.

To make the speed record meaningful, competitors had to start from the British Isles. However Moitessier, the most likely person to make a successful circumnavigation, was preparing to leave from Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

, in France. When the ''Sunday Times'' went to invite him to join the race, he was horrified, seeing the commercialisation of his voyage as a violation of the spiritual ideal which had inspired it. A few days later, Moitessier relented, thinking that he would join the race and that if he won, he would take the prizes and leave again without a word of thanks. In typical style, he refused the offer of a free radio to make progress reports, saying that this intrusion of the outside world would taint his voyage; he did, however, take a camera, agreeing to drop off packages of film if he got the chance.

The race declared

The race was announced on 17 March 1968, by which time King, Ridgway, Howell (who later dropped out), Knox-Johnston, and Moitessier were registered as competitors. Chichester, despite expressing strong misgivings about the preparedness of some of the interested parties, was to chair the panel of judges. Four days later, Britishelectronics

The field of electronics is a branch of physics and electrical engineering that deals with the emission, behaviour and effects of electrons using electronic devices. Electronics uses active devices to control electron flow by amplification ...

engineer Donald Crowhurst

Donald Charles Alfred Crowhurst (1932 – July 1969) was a British businessman and amateur sailor who disappeared while competing in the ''Sunday Times'' Golden Globe Race, a single-handed, round-the-world yacht race. Soon after he started th ...

announced his intention to take part. Crowhurst was the manufacturer of a modestly successful radio navigation

Radio navigation or radionavigation is the application of radio frequencies to determine a position of an object on the Earth, either the vessel or an obstruction. Like radiolocation, it is a type of radiodetermination.

The basic principles a ...

aid for sailors, who impressed many people with his apparent knowledge of sailing. With his electronics business failing, he saw a successful adventure, and the attendant publicity, as the solution to his financial troublesessentially the mirror opposite of Moitessier, who saw publicity and financial rewards as inimical to his adventure.

Crowhurst planned to sail in a trimaran

A trimaran (or double-outrigger) is a multihull boat that comprises a main hull and two smaller outrigger hulls (or "floats") which are attached to the main hull with lateral beams. Most modern trimarans are sailing yachts designed for recreati ...

. These boats were starting to gain a reputation, still very much unproven, for speed, along with a darker reputation for unseaworthiness; they were known to be very stable under normal conditions, but extremely difficult to right if knocked over, for example by a rogue wave

Rogue waves (also known as freak waves, monster waves, episodic waves, killer waves, extreme waves, and abnormal waves) are unusually large, unpredictable, and suddenly appearing surface waves that can be extremely dangerous to ships, even to lar ...

. Crowhurst planned to tackle the deficiencies of the trimaran with a revolutionary self-righting system, based on an automatically inflated air bag at the masthead. He would prove the system on his voyage, then go into business manufacturing it, thus making trimarans into safe boats for cruisers.

By June, Crowhurst had secured some financial backing, essentially by mortgaging the boat, and later his family home. Crowhurst's boat, however, had not yet been built; despite the lateness of his entry, he pressed ahead with the idea of a custom boat, which started construction in late June. Crowhurst's belief was that a trimaran would give him a good chance of the prize for the fastest circumnavigation, and with the help of a wildly optimistic table of probable performances, he even predicted that he would be first to finishdespite a planned departure on 1 October.

The race

The start (1 June to 28 July)

Given the design of the race, there was no organised start; the competitors set off whenever they were ready, over a period of several months. On 1 June 1968, the first allowable day, John Ridgway sailed fromInishmore

Inishmore ( ga, Árainn , or ) is the largest of the Aran Islands in Galway Bay, off the west coast of Ireland. With an area of and a population of 762 (as of 2016), it is the second-largest island off the Irish coast (after Achill) and ...

, Ireland, in his weekend cruiser ''English Rose IV''. Just a week later, on 8 June, Chay Blyth followed suitdespite having absolutely no sailing experience. On the day he set sail, he had friends rig the boat ''Dytiscus'' for him and then sail in front of him in another boat to show him the correct manoeuvres.

Knox-Johnston got underway from Falmouth soon after, on 14 June. He was undisturbed by the fact that it was a Friday, contrary to the common sailors' superstition that it is bad luck to begin a voyage on a Friday

Friday is the day of the week between Thursday and Saturday. In countries that adopt the traditional "Sunday-first" convention, it is the sixth day of the week. In countries adopting the ISO-defined "Monday-first" convention, it is the fifth day ...

. ''Suhaili'', crammed with tinned food, was low in the water and sluggish, but the much more seaworthy boat soon started gaining on Ridgway and Blyth.

It soon became clear to Ridgway that his boat was not up to a serious voyage, and he was also becoming affected by loneliness. On 17 June, at Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

, he made an arranged rendezvous with a friend to drop off his photos and logs, and received some mail in exchange. While reading a recent issue of the ''Sunday Times'' that he had just received, he discovered that the rules against assistance prohibited receiving mailincluding the newspaper in which he was reading thisand so he was technically disqualified. While he dismissed this as overly petty, he continued the voyage in bad spirits. The boat continued to deteriorate, and he finally decided that it would not be able to handle the heavy conditions of the Southern Ocean. On 21 July he put into Recife

That it may shine on all ( Matthew 5:15)

, image_map = Brazil Pernambuco Recife location map.svg

, mapsize = 250px

, map_caption = Location in the state of Pernambuco

, pushpin_map = Brazil#South A ...

, Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

, and retired from the race.

Even with the race underway, other competitors continued to declare their intention to join. On 30 June, Royal Navy officer Nigel Tetley announced that he would race in the trimaran

A trimaran (or double-outrigger) is a multihull boat that comprises a main hull and two smaller outrigger hulls (or "floats") which are attached to the main hull with lateral beams. Most modern trimarans are sailing yachts designed for recreati ...

he and his wife lived aboard. He obtained sponsorship from Music for Pleasure, a British budget record label, and started preparing his boat, ''Victress'', in Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

, where Moitessier, King, and Frenchman Loïck Fougeron were also getting ready. Fougeron was a friend of Moitessier, who managed a motorcycle company in Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...

, and planned to race on ''Captain Browne'', a steel gaff

Gaff may refer to:

Ankle-worn devices

* Spurs in variations of cockfighting

* Climbing spikes used to ascend wood poles, such as utility poles

Arts and entertainment

* A character in the ''Blade Runner'' film franchise

* Penny gaff, a 19th-ce ...

cutter. Crowhurst, meanwhile, was far from readyassembly of the three hulls of his trimaran only began on 28 July at a boatyard in Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

.

Attrition begins (29 July to 31 October)

Blyth and Knox-Johnston were well down the Atlantic by this time. Knox-Johnston, the experienced seaman, was enjoying himself, but ''Suhaili'' had problems with leaking seams near the

Blyth and Knox-Johnston were well down the Atlantic by this time. Knox-Johnston, the experienced seaman, was enjoying himself, but ''Suhaili'' had problems with leaking seams near the keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

. However, Knox-Johnston had managed a good repair by diving

Diving most often refers to:

* Diving (sport), the sport of jumping into deep water

* Underwater diving, human activity underwater for recreational or occupational purposes

Diving or Dive may also refer to:

Sports

* Dive (American football), a ...

and caulking

Caulk or, less frequently, caulking is a material used to seal joints or seams against leakage in various structures and piping.

The oldest form of caulk consisted of fibrous materials driven into the wedge-shaped seams between boards on w ...

the seams underwater.

Blyth was not far ahead, and although leading the race, he was having far greater problems with his boat, which was suffering in the hard conditions. He had also discovered that the fuel for his generator

Generator may refer to:

* Signal generator, electronic devices that generate repeating or non-repeating electronic signals

* Electric generator, a device that converts mechanical energy to electrical energy.

* Generator (circuit theory), an eleme ...

had been contaminated, which effectively put his radio out of action. On 15 August, Blyth went in to Tristan da Cunha

Tristan da Cunha (), colloquially Tristan, is a remote group of volcanic islands in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is the most remote inhabited archipelago in the world, lying approximately from Cape Town in South Africa, from Saint Helena ...

to pass a message to his wife, and spoke to crew from an anchored cargo ship, ''Gillian Gaggins''. On being invited aboard by her captain, a fellow Scot

The Scots ( sco, Scots Fowk; gd, Albannaich) are an ethnic group and nation native to Scotland. Historically, they emerged in the early Middle Ages from an amalgamation of two Celtic-speaking peoples, the Picts and Gaels, who founded t ...

, Blyth found the offer impossible to refuse and went aboard, while the ship's engineers fixed his generator and replenished his fuel supply.

By this time he had already shifted his focus from the race to a more personal quest to discover his own limits; and so, despite his technical disqualification for receiving assistance, he continued sailing towards Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

. His boat continued to deteriorate, however, and on 13 September he put into East London

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the f ...

. Having successfully sailed the length of the Atlantic and rounded Cape Agulhas

Cape Agulhas (; pt, Cabo das Agulhas , "Cape of the Needles") is a rocky headland in Western Cape, South Africa.

It is the geographic southern tip of the African continent and the beginning of the dividing line between the Atlantic and Indian ...

in an unsuitable boat, he decided that he would take on the challenge of the sea again, but in a better boat and on his own terms.

Despite the retirements, other racers were still getting started. On Thursday, 22 August, Moitessier and Fougeron set off, with King following on Saturday (none of them wanted to leave on a Friday). With ''Joshua'' lightened for a race, Moitessier set a fast pacemore than twice as fast as Knox-Johnston over the same part of the course. Tetley sailed on 16 September, and on 23 September, Crowhurst's boat, ''Teignmouth Electron'', was finally launched in Norfolk. Under severe time pressure, Crowhurst planned to sail to Teignmouth

Teignmouth ( ) is a seaside town, fishing port and civil parish in the English county of Devon. It is situated on the north bank of the estuary mouth of the River Teign, about 12 miles south of Exeter. The town had a population of 14,749 at the ...

, his planned departure point, in three days; but although the boat performed well downwind, the struggle against headwinds in the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

showed severe deficiencies in the boat's upwind performance, and the trip to Teignmouth took 13 days.

Meanwhile, Moitessier was making excellent progress. On 29 September he passed Trindade in the south Atlantic, and on 20 October he reached Cape Town, where he managed to leave word of his progress. He sailed on east into the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is regarded as the second-small ...

, where he continued to make good speed, covering on 28 October.

Others were not so comfortable with the ocean conditions. On 30 October, Fougeron passed Tristan da Cunha, with King a few hundred nautical miles ahead. The next dayHalloween

Halloween or Hallowe'en (less commonly known as Allhalloween, All Hallows' Eve, or All Saints' Eve) is a celebration observed in many countries on 31 October, the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Saints' Day. It begins the observanc ...

they both found themselves in a severe storm. Fougeron hove-to

In sailing, heaving to (to heave to and to be hove to) is a way of slowing a sailing vessel's forward progress, as well as fixing the helm and sail positions so that the vessel does not have to be steered. It is commonly used for a "break"; this ...

, but still suffered a severe knockdown. King, who allowed his boat to tend to herself (a recognised procedure known as ''lying ahull In sailing, lying ahull is a controversial method of weathering a storm, executed by downing all sails, battening the hatches and locking the tiller to leeward so the boat tries to point to windward but this is balanced by the force of wind and wav ...

''), had a much worse experience; his boat was rolled and lost its foremast. Both men decided to retire from the race.

The last starters (31 October to 23 December)

Four of the starters had decided to retire at this point, at which time Moitessier was east of Cape Town, Knox-Johnston was ahead in the middle of theGreat Australian Bight

The Great Australian Bight is a large oceanic bight, or open bay, off the central and western portions of the southern coastline of mainland Australia.

Extent

Two definitions of the extent are in use – one used by the International Hydrog ...

, and Tetley was just nearing Trindade. However, 31 October was also the last allowable day for racers to start, and was the day that the last two competitors, Donald Crowhurst and Alex Carozzo, got under way. Carozzo, a highly regarded Italian sailor, had competed in (but not finished) that year's ''OSTAR''. Considering himself unready for sea, he "sailed" on 31 October, to comply with the race's mandatory start date, but went straight to a mooring

A mooring is any permanent structure to which a vessel may be secured. Examples include quays, wharfs, jetties, piers, anchor buoys, and mooring buoys. A ship is secured to a mooring to forestall free movement of the ship on the water. An ''anc ...

to continue preparing his boat without outside assistance. Crowhurst was also far from readyhis boat, barely finished, was a chaos of unstowed supplies, and his self-righting system was unbuilt. He left anyway, and started slowly making his way against the prevailing winds of the English Channel.

By mid-November Crowhurst was already having problems with his boat. Hastily built, the boat was already showing signs of being unprepared, and in the rush to depart, Crowhurst had left behind crucial repair materials. On 15 November, he made a careful appraisal of his outstanding problems and of the risks he would face in the

By mid-November Crowhurst was already having problems with his boat. Hastily built, the boat was already showing signs of being unprepared, and in the rush to depart, Crowhurst had left behind crucial repair materials. On 15 November, he made a careful appraisal of his outstanding problems and of the risks he would face in the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is regarded as the second-small ...

; he was also acutely aware of the financial problems awaiting him at home. Despite his analysis that ''Teignmouth Electron'' was not up to the severe conditions which she would face in the Roaring Forties

The Roaring Forties are strong westerly winds found in the Southern Hemisphere, generally between the latitudes of 40°S and 50°S. The strong west-to-east air currents are caused by the combination of air being displaced from the Equator ...

, he pressed on.

Carozzo retired on 14 November, as he had started vomiting blood due to a peptic ulcer

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is a break in the inner lining of the stomach, the first part of the small intestine, or sometimes the lower esophagus. An ulcer in the stomach is called a gastric ulcer, while one in the first part of the intestines i ...

, and put into Porto

Porto or Oporto () is the second-largest city in Portugal, the capital of the Porto District, and one of the Iberian Peninsula's major urban areas. Porto city proper, which is the entire municipality of Porto, is small compared to its metropol ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

, for medical attention. Two more retirements were reported in rapid succession, as King made Cape Town on 22 November, and Fougeron stopped in Saint Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constitu ...

on 27 November. This left four boats in the race at the beginning of December: Knox-Johnston's ''Suhaili'', battling frustrating and unexpected headwinds in the south Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, Moitessier's ''Joshua'', closing on Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

, Tetley's ''Victress'', just passing the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

, and Crowhurst's ''Teignmouth Electron'', still in the north Atlantic.

Tetley was just entering the Roaring Forties, and encountering strong winds. He experimented with self-steering systems based on various combinations of headsails, but had to deal with some frustrating headwinds. On 21 December he encountered a calm and took the opportunity to clean the hull somewhat; while doing so, he saw a shark prowling around the boat. He later caught it, using a shark hook baited with a tin of bully beef (corned beef), and hoisted it on board for a photo. His log is full of sail changes and other such sailing technicalities and gives little impression of how he was coping with the voyage emotionally; still, describing a heavy low on 15 December he hints at his feelings, wondering "why the hell I was on this voyage anyway".

Knox-Johnston was having problems, as ''Suhaili'' was showing the strains of the long and hard voyage. On 3 November, his self-steering gear had failed for the last time, as he had used up all his spares. He was also still having leak problems, and his rudder was loose. Still, he felt that the boat was fundamentally sound, so he braced the rudder as well as he could, and started learning to balance the boat in order to sail a constant course on her own. On 7 November, he dropped mail off in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

, and on 19 November he made an arranged meeting off the Southern Coast of New Zealand with a ''Sunday Mirror'' journalist from Otago, New Zealand

Otago (, ; mi, Ōtākou ) is a region of New Zealand located in the southern half of the South Island administered by the Otago Regional Council. It has an area of approximately , making it the country's second largest local government regi ...

.

Crowhurst's false voyage (6 to 23 December)

On 10 December, Crowhurst reported that he had had some fast sailing at last, including a day's run on 8 December of , a new 24-hour record.Francis Chichester

Sir Francis Charles Chichester KBE (17 September 1901 – 26 August 1972) was a British businessman, pioneering aviator and solo sailor.

He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for becoming the first person to sail single-handed around the worl ...

was sceptical of Crowhurst's sudden change in performance, and with good reasonon 6 December, Crowhurst had started creating a faked record of his voyage, showing his position advancing much faster than it actually was. The creation of this fake log was an incredibly intricate process, involving working celestial navigation in reverse.

The motivation for this initial deception was most likely to allow him to claim an attention-getting record prior to entering the doldrums

The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ ), known by sailors as the doldrums or the calms because of its monotonous windless weather, is the area where the northeast and the southeast trade winds converge. It encircles Earth near the thermal e ...

. However, from that point on, he started to keep two logshis actual navigation log, and a second log in which he could enter a faked description of a round-the-world voyage. This would have been an immensely difficult task, involving the need to make up convincing descriptions of weather and sailing conditions in a different part of the world, as well as complex reverse navigation. He tried to keep his options open as long as possible, mainly by giving only extremely vague position reports; but on 17 December he sent a deliberately false message indicating that he was over the Equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

, which he was not. From this point his radio reportswhile remaining ambiguousindicated steadily more impressive progress around the world; but he never left the Atlantic, and it seems that after December the mounting problems with his boat had caused him to give up on ever doing so.

Christmas at sea (24 to 25 December)

Christmas Day 1968 was a strange day for the four racers, who were very far from friends and family. Crowhurst made a radio call to his wife on Christmas Eve, during which he was pressed for a precise position, but refused to give one. Instead, he told her he was "off Cape Town", a position far in advance of his plotted fake position, and even farther from his actual position, off the easternmost point inBrazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

, just 7 degrees () south of the equator.

Like Crowhurst, Tetley was depressed. He had a lavish Christmas dinner of roast pheasant, but was suffering badly from loneliness. Knox-Johnston, thoroughly at home on the sea, treated himself to a generous dose of whisky and held a rousing solo carol service, then drank a toast to the Queen at 3pm. He managed to pick up some radio stations from the U.S., and heard for the first time about the Apollo 8

Apollo 8 (December 21–27, 1968) was the first crewed spacecraft to leave low Earth orbit and the first human spaceflight to reach the Moon. The crew orbited the Moon ten times without landing, and then departed safely back to Earth. These ...

astronauts, who had just made the first orbit of the Moon. Moitessier, meanwhile, was sunbathing in a flat calm, deep in the roaring forties south-west of New Zealand.

Rounding the Horn (26 December to 18 March)

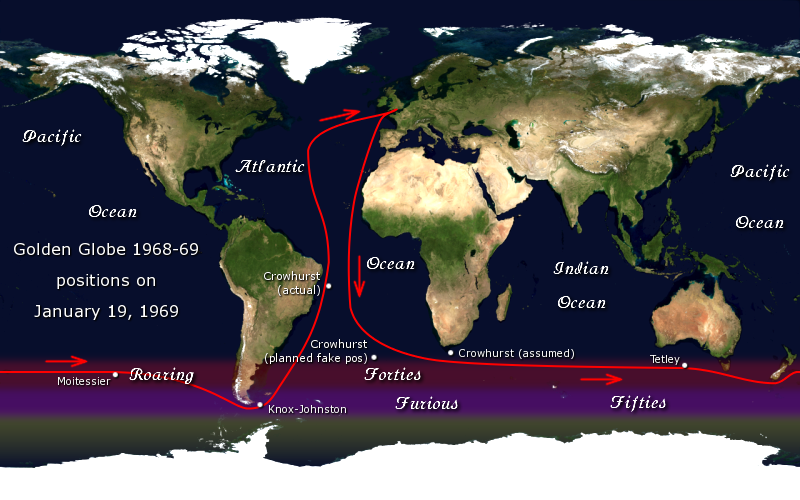

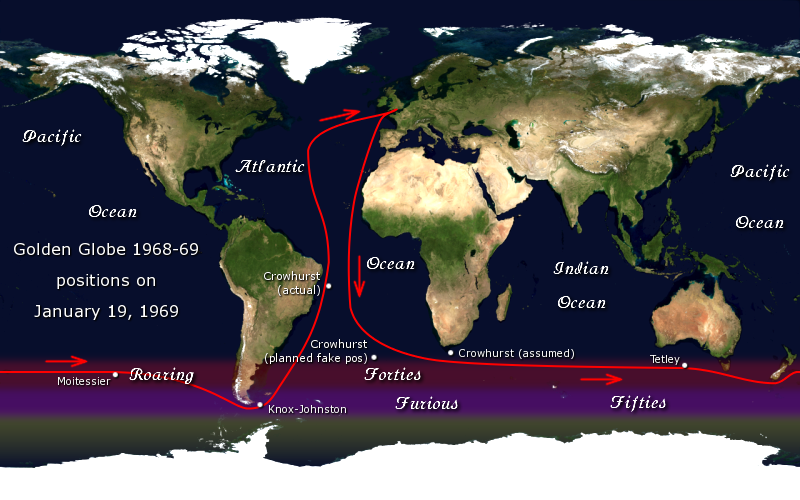

By January, concern was growing for Knox-Johnston. He was having problems with his radio transmitter and nothing had been heard since he had passed south of New Zealand. He was actually making good progress, rounding

By January, concern was growing for Knox-Johnston. He was having problems with his radio transmitter and nothing had been heard since he had passed south of New Zealand. He was actually making good progress, rounding Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramírez ...

on 17 January 1969. Elated by this successful climax to his voyage, he briefly considered continuing east, to sail around the Southern Ocean a second time, but soon gave up the idea and turned north for home.

Crowhurst's deliberately vague position reporting was also causing consternation for the press, who were desperate for hard facts. On 19 January, he finally yielded to the pressure and stated himself to be south-east of Gough Island

upright=1.3, Map of Gough island

Gough Island ( ), also known historically as Gonçalo Álvares, is a rugged volcanic island in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a dependency of Tristan da Cunha and part of the British overseas territory of Sain ...

in the south Atlantic. He also reported that due to generator problems he was shutting off his radio for some time. His position was misunderstood on the receiving end to be south-east of the Cape of Good Hope; the high speed this erroneous position implied fuelled newspaper speculation in the following radio silence, and his position was optimistically reported as rapidly advancing around the globe. Crowhurst's actual position, meanwhile, was off Brazil, where he was making slow progress south, and carefully monitoring weather reports from around the world to include in his fake log. He was also becoming increasingly concerned about ''Teignmouth Electron'', which was starting to come apart, mainly due to slapdash construction.

Moitessier also had not been heard from since New Zealand, but he was still making good progress and coping easily with the conditions of the "furious fifties". He was carrying letters from old Cape Horn sailors describing conditions in the Southern Ocean, and he frequently consulted these to get a feel for chances of encountering ice. He reached the Horn on 6 February, but when he started to contemplate the voyage back to Plymouth he realised that he was becoming increasingly disenchanted with the race concept.

As he sailed past the

As he sailed past the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouzet ...

he was sighted, and this first news of him since Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

caused considerable excitement. It was predicted that he would arrive home on 24 April as the winner (in fact, Knox-Johnston finished on 22 April). A huge reception was planned in Britain, from where he would be escorted to France by a fleet of French warships for an even more grand reception. There was even said to be a Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

waiting for him there.

Moitessier had a very good idea of this, but throughout his voyage he had been developing an increasing disgust with the excesses of the modern world; the planned celebrations seemed to him to be yet another example of brash materialism. After much debate with himself, and many thoughts of those waiting for him in England, he decided to continue sailingpast the Cape of Good Hope, and across the Indian Ocean for a second time, into the Pacific. Unaware of this, the newspapers continued to publish "assumed" positions progressing steadily up the Atlantic, until, on 18 March, Moitessier fired a slingshot message in a can onto a ship near the shore of Cape Town, announcing his new plans to a stunned world:

On the same day, Tetley rounded Cape Horn, becoming the first to accomplish the feat in a multihull

A multihull is a boat or ship with more than one hull, whereas a vessel with a single hull is a monohull. The most common multihulls are catamarans (with two hulls), and trimarans (with three hulls). There are other types, with four or more h ...

sailboat. Badly battered by his Southern Ocean voyage, he turned north with considerable relief.

Re-establishing contact (19 March to 22 April)

''Teignmouth Electron'' was also battered and Crowhurst badly wanted to make repairs, but without the spares that had been left behind he needed new supplies. After some planning, on 8 March he put into the tiny settlement of Río Salado, inArgentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, just south of the Río de la Plata

The Río de la Plata (, "river of silver"), also called the River Plate or La Plata River in English, is the estuary formed by the confluence of the Uruguay River and the Paraná River at Punta Gorda. It empties into the Atlantic Ocean and fo ...

. Although the village turned out to be the home of a small coastguard

A coast guard or coastguard is a maritime security organization of a particular country. The term embraces wide range of responsibilities in different countries, from being a heavily armed military force with customs and security duties to ...

station, and his presence was logged, he got away with his supplies and without publicity. He started heading south again, intending to get some film and experience of Southern Ocean conditions to bolster his false log.

The concern for Knox-Johnston turned to alarm in March, with no news of him since New Zealand; aircraft taking part in a NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

exercise in the North Atlantic mounted a search operation in the region of the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

. However, on 6 April he finally managed to make contact with a British tanker using his signal lamp

Signal lamp training during World War II

A signal lamp (sometimes called an Aldis lamp or a Morse lamp) is a semaphore system using a visual signaling device for optical communication, typically using Morse code. The idea of flashing dots and ...

, which reported the news of his position, from home. This created a sensation in Britain, with Knox-Johnston now clearly set to win the Golden Globe trophy, and Tetley predicted to win the £5,000 prize for the fastest time.

Crowhurst re-opened radio contact on 10 April, reporting himself to be "heading" towards the

Crowhurst re-opened radio contact on 10 April, reporting himself to be "heading" towards the Diego Ramirez Islands

Diego is a Spanish masculine given name. The Portuguese equivalent is Diogo. The name also has several patronymic derivations, listed below. The etymology of Diego is disputed, with two major origin hypotheses: ''Tiago'' and ''Didacus''.

Et ...

, near Cape Horn. This news caused another sensation, as with his projected arrival in the UK at the start of July he now seemed to be a contender for the fastest time, and (very optimistically) even for a close finish with Tetley. Once his projected false position approached his actual position, he started heading north at speed.

Tetley, informed that he might be robbed of the fastest-time prize, started pushing harder, despite that his boat was having significant problemshe made major repairs at sea in an attempt to stop the port hull of his trimaran falling off, and kept racing. On 22 April, he crossed his outbound track, one definition of a circumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical object, astronomical body (e.g. a planet or natural satellite, moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circ ...

.

The finish (22 April to 1 July)

On the same day, 22 April, Knox-Johnston completed his voyage where it had started, in Falmouth. This made him the winner of the Golden Globe trophy, and the first person to sail single-handed and non-stop around the world, which he had done in 312 days. This left Tetley and Crowhurst apparently fighting for the £5,000 prize for fastest time. However, Tetley knew that he was pushing his boat too hard. On 20 May he ran into a storm near the Azores and began to worry about the boat's severely weakened state. Hoping that the storm would soon blow over, he lowered all sail and went to sleep with the boat lying a-hull. In the early hours of the next day he was awoken by the sounds of tearing wood. Fearing that the bow of the port hull might have broken off, he went on deck to cut it loose, only to discover that in breaking away it had made a large hole in the main hull, from which ''Victress'' was now taking on water too rapidly to stop. He sent aMayday

Mayday is an emergency procedure word used internationally as a distress signal in voice-procedure radio communications.

It is used to signal a life-threatening emergency primarily by aviators and mariners, but in some countries local organiza ...

, and luckily got an almost immediate reply. He abandoned ship just before ''Victress'' finally sank and was rescued from his liferaft

A lifeboat or liferaft is a small, rigid or inflatable boat carried for emergency evacuation in the event of a disaster aboard a ship. Lifeboat drills are required by law on larger commercial ships. Rafts (liferafts) are also used. In the mil ...

that evening, having come to within of finishing what would have been the most significant voyage ever made in a multi-hulled boat.

Crowhurst was left as the only person in the race, andgiven his high reported speedsvirtually guaranteed the £5,000 prize. This would, however, also guarantee intense scrutiny of himself, his stories, and his logs by genuine Cape Horn veterans such as the sceptical Chichester. Although he had put great effort into his fabricated log, such a deception would in practice be extremely difficult to carry off, particularly for someone who did not have actual experience of the Southern Ocean; something of which he must have been aware at heart. Although he had been sailing fastat one point making over in a dayas soon as he learned of Tetley's sinking, he slowed down to a wandering crawl.

Crowhurst's main radio failed at the beginning of June, shortly after he had learned that he was the sole remaining competitor. Plunged into unwilling solitude, he spent the following weeks attempting to repair the radio, and on 22 June was finally able to transmit and receive in morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one of ...

. The following days were spent exchanging cables

Cable may refer to:

Mechanical

* Nautical cable, an assembly of three or more ropes woven against the weave of the ropes, rendering it virtually waterproof

* Wire rope, a type of rope that consists of several strands of metal wire laid into a hel ...

with his agent and the press, during which he was bombarded with news of syndication rights, a welcoming fleet of boats and helicopters, and a rapturous welcome by the British people. It became clear that he could not now avoid the spotlight.

Unable to see a way out of his predicament, he plunged into abstract philosophy, attempting to find an escape in metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

, and on 24 June he started writing a long essay to express his ideas. Inspired (in a misguided way) by the work of Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

, whose book '' Relativity: The Special and General Theory'' he had aboard, the theme of Crowhurst's writing was that a sufficiently intelligent mind can overcome the constraints of the real world. Over the following eight days, he wrote 25,000 words of increasingly tortured prose, drifting farther and farther from reality, as ''Teignmouth Electron'' continued sailing slowly north, largely untended. Finally, on 1 July, he concluded his writing with a garbled suicide note and, it is assumed, jumped overboard.

Moitessier, meanwhile, had concluded his own personal voyage more happily. He had circumnavigated the world and sailed almost two-thirds of the way round a second time, all non-stop and mostly in the roaring forties. Despite heavy weather and a couple of severe knockdowns, he contemplated rounding the Horn again. However, he decided that he and ''Joshua'' had had enough and sailed to Tahiti, where he and his wife had set out for Alicante. He thus completed his second personal circumnavigation of the world (including the previous voyage with his wife) on 21 June 1969. He started work on his book.

Aftermath of the race

Knox-Johnston, as the only finisher, was awarded both the Golden Globe trophy and the £5,000 prize for fastest time. He continued to sail and circumnavigated three more times. He was awarded aCBE

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

in 1969 and was knighted in 1995.

It is impossible to say that Moitessier would have won if he had completed the race, as he would have been sailing in different weather conditions than Knox-Johnston did, but based on his time from the start to Cape Horn being about 77% of that of Knox-Johnston, it would have been extremely close. However Moitessier is on record as stating that he would not have won. His book, ''The Long Way'', tells the story of his voyage as a spiritual journey as much as a sailing adventure and is still regarded as a classic of sailing literature. ''Joshua'' was beached, along with many other yachts, by a storm at Cabo San Lucas

Cabo San Lucas (, "Saint Luke Cape"), or simply just Cabo, is a resort city at the southern tip of the Baja California Peninsula, in the Mexican state of Baja California Sur. As at the 2020 Census, the population of the city was 202,694 inhabitan ...

in December 1982; with a new boat, ''Tamata'', Moitessier sailed back to Tahiti from the San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water from a ...

. He died in 1994.

When ''Teignmouth Electron'' was discovered drifting and abandoned in the Atlantic on 10 July, a fund was started for Crowhurst's wife and children; Knox-Johnston donated his £5,000 prize to the fund, and more money was added by press and sponsors. The news of his deception, mental breakdown, and suicide, as chronicled in his surviving logbooks, was made public a few weeks later, causing a sensation. Nicholas Tomalin and Ron Hall, two of the journalists connected with the race, wrote a 1970 book on Crowhurst's voyage, ''The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst'', described by Hammond Innes

Ralph Hammond Innes (15 July 1913 – 10 June 1998) was a British novelist who wrote over 30 novels, as well as works for children and travel books.

Biography

Innes was born in Horsham, Sussex, and educated at Feltonfleet School, Cobham, Surrey ...

in its ''Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of News UK, whi ...

'' review as "fascinating, uncomfortable reading" and a "meticulous investigation" of Crowhurst's downfall.

Tetley found it impossible to adapt to his old way of life after his adventure. He was awarded a consolation prize of £1,000, with which he decided to build a new trimaran for a round-the-world speed record attempt. His boat ''Miss Vicky'' was built in 1971, but his search for sponsorship to pay for fitting-out met with consistent rejection. His book, ''Trimaran Solo'', sold poorly. Although he outwardly seemed to be coping, the repeated failures must have taken their toll. In February 1972, he went missing from his home in Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

. His body was found in nearby woods hanging from a tree three days later. His death was originally believed to be a suicide. At the inquest

An inquest is a judicial inquiry in common law jurisdictions, particularly one held to determine the cause of a person's death. Conducted by a judge, jury, or government official, an inquest may or may not require an autopsy carried out by a coro ...

, it was revealed that the body had been discovered wearing lingerie and the hands were bound. The attending pathologist suggested the likelihood of masochistic sexual activity. Finding no evidence to suggest that Tetley had killed himself, the coroner recorded an open verdict The open verdict is an option open to a coroner's jury at an inquest in the legal system of England and Wales. The verdict means the jury confirms the death is suspicious, but is unable to reach any other verdicts open to them. Mortality studies c ...

. Tetley was cremated; Knox-Johnson and Blyth were among the mourners in attendance.

Blyth devoted his life to the sea and to introducing others to its challenge. In 1970–1971 he sailed a sponsored boat, ''British Steel'', single-handedly around the world "the wrong way", against the prevailing winds. He subsequently took part in the Whitbread Round the World Yacht Race and founded the Global Challenge

The Global Challenge (not to be confused with Global Challenge Award) was a round the world yacht race run by Challenge Business, the company started by Sir Chay Blyth in 1989. It was held every four years, and took a fleet of one-design steel y ...

race, which allows amateurs to race around the world. His old rowing partner, John Ridgway, followed a similar course; he started an adventure school in Scotland, and circumnavigated the world twice under sail: once in the Whitbread Round the World Yacht Race, and once with his wife. King finally completed a circumnavigation in ''Galway Blazer II'' in 1973.

''Suhaili'' was sailed for some years more, including a trip to Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

, and spent some years on display at the National Maritime Museum

The National Maritime Museum (NMM) is a maritime museum in Greenwich, London. It is part of Royal Museums Greenwich, a network of museums in the Maritime Greenwich World Heritage Site. Like other publicly funded national museums in the United ...

at Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

. However, her planking began to shrink because of the dry conditions and, unwilling to see her deteriorate, Knox-Johnston removed her from the museum and had her refitted in 2002. She was returned to the water and is now based at the National Maritime Museum Cornwall

The National Maritime Museum, Cornwall is located in a harbourside building at Falmouth in Cornwall, England. The building was designed by architect M. J. Long, following an architectural design competition managed by RIBA Competitions.

The ...

.

''Teignmouth Electron'' was sold to a tour operator in Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

and eventually ended up damaged and abandoned on Cayman Brac

Cayman Brac is an island that is part of the Cayman Islands. It lies in the Caribbean Sea about north-east of Grand Cayman and east of Little Cayman. It is about long, with an average width of . Its terrain is the most prominent of the thre ...

, where she lies to this day.

After being driven ashore during a storm at Cabo San Lucas

Cabo San Lucas (, "Saint Luke Cape"), or simply just Cabo, is a resort city at the southern tip of the Baja California Peninsula, in the Mexican state of Baja California Sur. As at the 2020 Census, the population of the city was 202,694 inhabitan ...

, the restored ''Joshua'' was acquired by the maritime museum in La Rochelle

La Rochelle (, , ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''La Rochéle''; oc, La Rochèla ) is a city on the west coast of France and a seaport on the Bay of Biscay, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. It is the capital of the Charente-Maritime department. With ...

, France, where it serves as part of a cruising school.

Given the failure of most starters and the tragic outcome of Crowhurst's voyage, considerable controversy was raised over the race and its organisation. No follow-up race was held for some time. However, in 1982 the ''BOC Challenge'' race was organised; this single-handed round-the-world race with stops was inspired by the Golden Globe and has been held every four years since. In 1989, Philippe Jeantot

Philippe Jeantot (born 8 May 1952 in Antananarivo, Madagascar) is a French former deep sea diver, who achieved recognition as a sailor for long-distance, single-handed racing and record-setting. He founded the ''Vendée Globe'', a single-handed, r ...

founded the ''Vendée Globe

-->

The Vendée Globe is a single-handed (solo) non-stop round the world yacht race. The race was founded by Philippe Jeantot in 1989, and since 1992 has taken place every four years. It is named after the Département of Vendée, in France, w ...

'' race, a non-stop, single-handed, round-the-world race. Essentially the successor to the Golden Globe, this race is also held every four years and has attracted public following for the sport.

Competitors

Nine competitors participated in the race. Most of these had at least some prior sailing experience, although only Carozzo had competed in a major ocean race prior to the Golden Globe Race. The following table lists the entrants in order of starting, together with their prior sailing experience, and achievements in the race:2018 Golden Globe Race

For the 50th anniversary of the first race, there was another Golden Globe Race in 2018. Entrants were limited to sailing similar yachts and equipment to what was available to Sir Robin in the original race. This race started fromLes Sables-d'Olonne

Les Sables-d'Olonne (; French meaning: "The Sands of Olonne"; Poitevin: ''Lés Sablles d'Oloune'') is a seaside town in Western France, on the Atlantic Ocean. A subprefecture of the department of Vendée, Pays de la Loire, it has the administ ...

on 1 July 2018. The prize purse has been confirmed as £75,000, with all sailors that finish before 15:25 on 22 April 2019 winning their entry fee back.

2022 Golden Globe Race

For the 54th anniversary of the first race, there is to be another Golden Globe Race in 2022. Entrants were limited to sailing similar yachts and equipment to what was available to Sir Robin in the original race, but in two classes. This race starts fromLes Sables-d'Olonne

Les Sables-d'Olonne (; French meaning: "The Sands of Olonne"; Poitevin: ''Lés Sablles d'Oloune'') is a seaside town in Western France, on the Atlantic Ocean. A subprefecture of the department of Vendée, Pays de la Loire, it has the administ ...

on 4 September 2022.

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * *Further reading

* ''The Circumnavigators: Small Boat Voyagers of Modern Times'', Donald Holm. Prentice-Hall, 1974. * ''Capsize'', by Bill King. Nautical Publishing, 1969. * ''The Longest Race'', by Hal Roth. W W Norton & Co Inc, 1983. * ''A Voyage For Madmen'', by Peter Nichols. Harper Collins Publishers, 2001. * ''A World of My Own'', by Robin Knox-Johnston. Cassell & Company LTD, 1969.Documentaries

* '' Deep Water'', directed by Louise Osmond andJerry Rothwell

Jerry Rothwell is a British documentary filmmaker best known for the award-winning feature docs '' How to Change the World'' (2015), ''Town of Runners'' (2012), ''Donor Unknown'' (2010), ''Heavy Load'' (2008) and ''Deep Water'' (2006). All of his ...

(2006).

Narrative films

* '' Gonka Veka'' (''Race of the Century''), directed by Nikita Orlov (1986). * '' Crowhurst'', directed bySimon Rumley

Simon Rumley (born 22 May 1968) is a British screenwriter, director and author. Mostly associated with the horror genre, he was described by '' Screen International'' as "one of the great British cinematic outsiders, a gifted director with the k ...

(2017).

* ''The Mercy