Summerhill (book) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Summerhill: A Radical Approach to Child Rearing'' is a book about the English boarding school

''Summerhill: A Radical Approach to Child Rearing'' was written by

''Summerhill: A Radical Approach to Child Rearing'' was written by

''Summerhill'' is A. S. Neill's "aphoristic and anecdotal" account of his "famous" "early progressive school experiment in England" founded in the 1920s,

''Summerhill'' is A. S. Neill's "aphoristic and anecdotal" account of his "famous" "early progressive school experiment in England" founded in the 1920s,

Summerhill School

Summerhill School is an independent (i.e. fee-paying) boarding school in Leiston, Suffolk, England. It was founded in 1921 by Alexander Sutherland Neill with the belief that the school should be made to fit the child, rather than the other wa ...

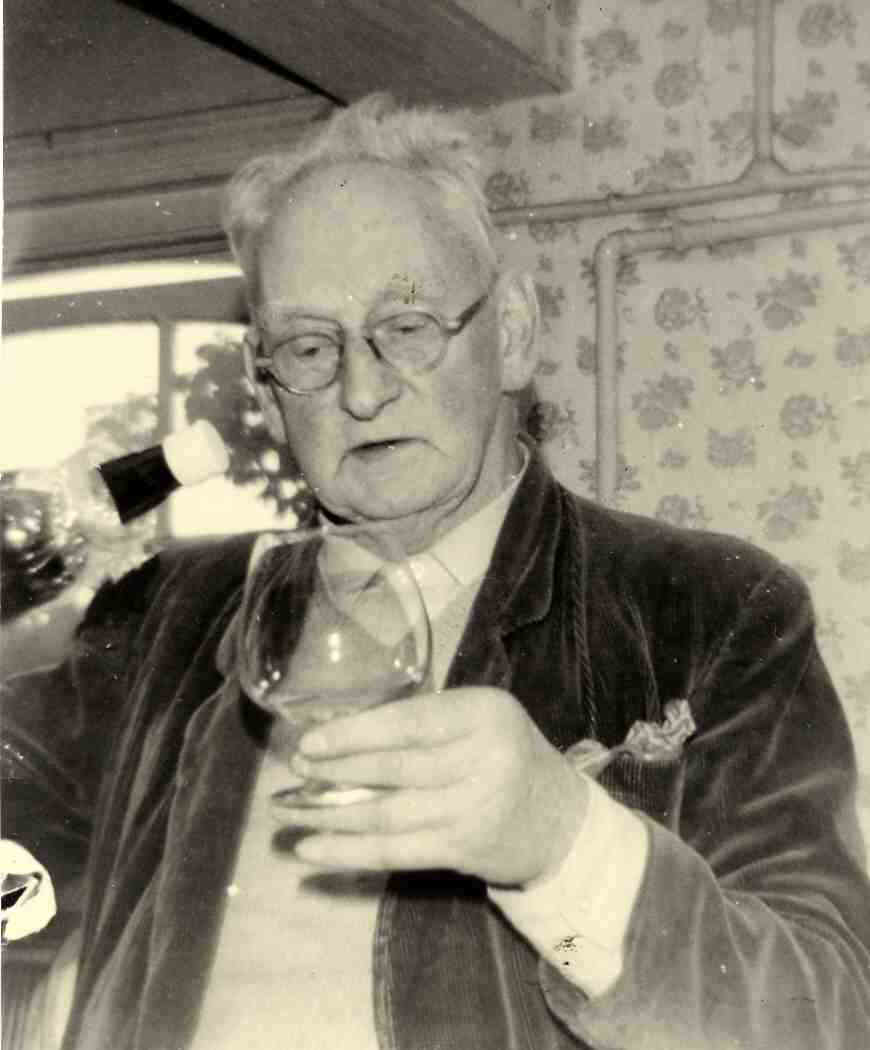

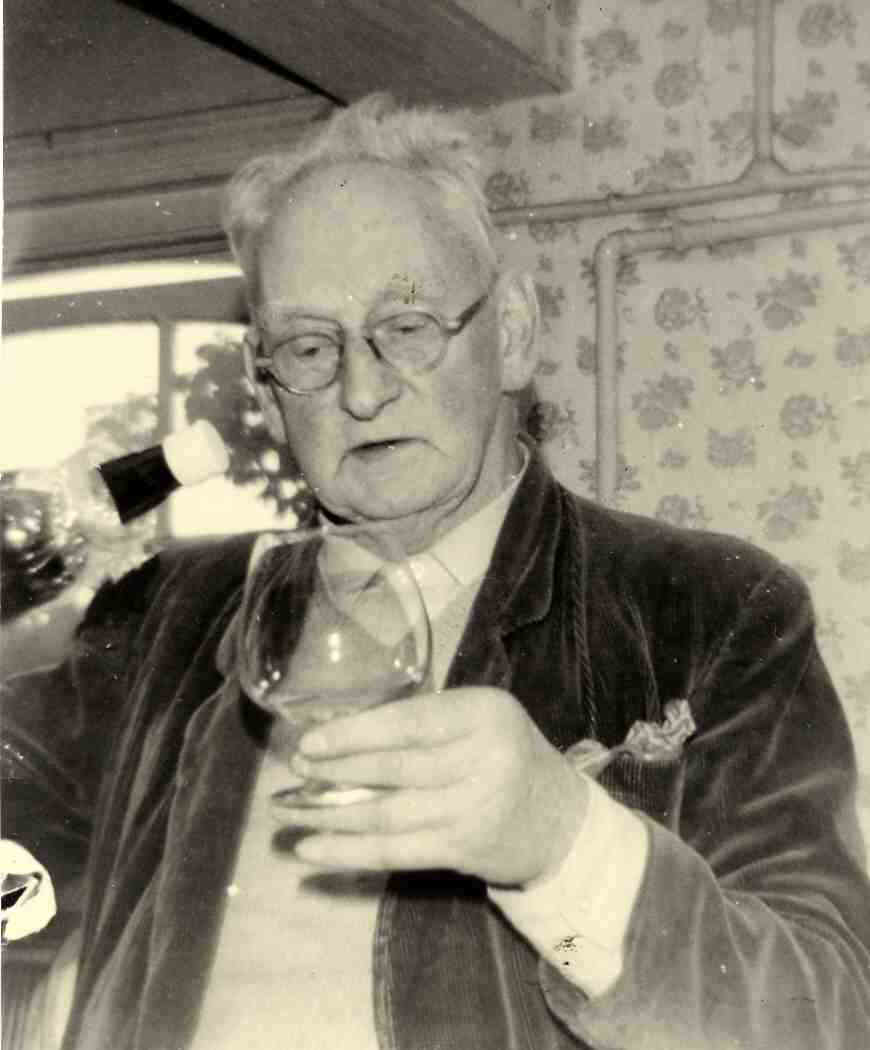

by its headmaster A. S. Neill

Alexander Sutherland Neill (17 October 1883 – 23 September 1973) was a Scottish educator and author known for his school, Summerhill, and its philosophy of freedom from adult coercion and community self-governance. Raised in Scotland, Neill ...

. It is known for introducing his ideas to the American public. It was published in America on November 7, 1960, by the Hart Publishing Company and later revised as ''Summerhill School: A New View of Childhood'' in 1993. Its contents are a repackaged collection from four of Neill's previous works. The foreword was written by psychoanalyst Erich Fromm

Erich Seligmann Fromm (; ; March 23, 1900 – March 18, 1980) was a German social psychologist, psychoanalyst, sociologist, humanistic philosopher, and democratic socialist. He was a German Jew who fled the Nazi regime and settled in the U ...

, who distinguished between authoritarian coercion and Summerhill.

The seven chapters of the book cover the origins and implementation of the school, and other topics in childrearing. Summerhill, founded in the 1920s, is run as a children's democracy under Neill's educational philosophy of self-regulation, where kids choose whether to go to lessons and how they want to live freely without imposing on others. The school makes its rules at a weekly schoolwide meeting where students and teachers each have one vote alike. Neill discarded other pedagogies for one of the innate goodness of the child.

Despite selling no advance copies in America, ''Summerhill'' brought Neill significant renown in the next decade, wherein he sold three million copies. The book was used in hundreds of college courses and translated into languages such as German. Reviewers noted Neill's charismatic personality, but doubted the project's general replicability elsewhere and its overstated generalizations. They put Neill in a lineage of experimental thought, but questioned his lasting contribution to psychology. The book begat an American Summerhillian following, cornered an education criticism market, and made Neill into a folk leader.

Background

''Summerhill: A Radical Approach to Child Rearing'' was written by

''Summerhill: A Radical Approach to Child Rearing'' was written by A. S. Neill

Alexander Sutherland Neill (17 October 1883 – 23 September 1973) was a Scottish educator and author known for his school, Summerhill, and its philosophy of freedom from adult coercion and community self-governance. Raised in Scotland, Neill ...

and published by Hart Publishing Company in 1960. In a letter to Neill, New York publisher Harold Hart suggested a book specific for America devised of parts from four of Neill's previous works: ''The Problem Child'', ''The Problem Parent'', ''The Free Child'', and ''That Dreadful School''. Neill liked his idea and gave the publisher wide liberties in the manuscript's preparation, preferring to write a preface or appendix in reflection on the writings. In rereading his work, he realized he disagreed with his earlier statements on Freudian

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies explained as originating in conflicts i ...

child analysis. Neill later regretted the liberties he afforded the publisher, particularly his removal of Wilheim Reich's name from the book and index, since Neill saw Reich as an influential figure. They also struggled over issues of copyrights. Neill did not contest his disagreements, as he was eager to see the book published.

The publisher and Neill disagreed over the choice of author for the book's foreword. Seeing forewords as more of an American tradition, Neill preferred not to have one, but suggested Henry Miller

Henry Valentine Miller (December 26, 1891 – June 7, 1980) was an American novelist. He broke with existing literary forms and developed a new type of semi-autobiographical novel that blended character study, social criticism, philosophical ref ...

, an American author who had recently written Neill a fan letter and whose ''Tropic'' series was banned in the United States. Hart didn't think Miller's introduction would help the book and approached Margaret Mead

Margaret Mead (December 16, 1901 – November 15, 1978) was an American cultural anthropologist who featured frequently as an author and speaker in the mass media during the 1960s and the 1970s.

She earned her bachelor's degree at Barnard Co ...

, who refused on the grounds of Neill's connection with Reich. Several months later, psychoanalyst and sociologist Erich Fromm

Erich Seligmann Fromm (; ; March 23, 1900 – March 18, 1980) was a German social psychologist, psychoanalyst, sociologist, humanistic philosopher, and democratic socialist. He was a German Jew who fled the Nazi regime and settled in the U ...

agreed to the project, and found consensus with Neill and the publisher. Fromm's introduction placed ''Summerhill'' in a history of backlash against progressive education and claimed that the "perverted" implementation of child freedom was more at fault than the idea of child freedom itself. He wrote that Summerhill was one of few schools that provided education without fear or hidden coercion, and that it carried the goals of "the Western humanistic tradition": "reason, love, integrity, and courage". Fromm also highlighted adult confusion about non-authoritarianism and how they mistook coercion for genuine freedom.

A revised edition was edited by Albert Lamb and released by St. Martin's Press

St. Martin's Press is a book publisher headquartered in Manhattan, New York City, in the Equitable Building. St. Martin's Press is considered one of the largest English-language publishers, bringing to the public some 700 titles a year under si ...

as ''Summerhill School: A New View of Childhood'' in 1993.

Summary

''Summerhill'' is A. S. Neill's "aphoristic and anecdotal" account of his "famous" "early progressive school experiment in England" founded in the 1920s,

''Summerhill'' is A. S. Neill's "aphoristic and anecdotal" account of his "famous" "early progressive school experiment in England" founded in the 1920s, Summerhill School

Summerhill School is an independent (i.e. fee-paying) boarding school in Leiston, Suffolk, England. It was founded in 1921 by Alexander Sutherland Neill with the belief that the school should be made to fit the child, rather than the other wa ...

. The book's intent is to demonstrate the origins and effects of unhappiness, and then show how to raise children to avoid this unhappiness. It is an "affirmation of the goodness of the child". ''Summerhill'' is the story of Summerhill School's origins, its programs and pupils, how they live and are affected by the program, and Neill's own educational philosophy. It is split into seven chapters that introduce the school and discuss parenting, sex, morality and religion, "children's problems", "parents' problems", and "questions and answers".

The school is run as a democracy, with students deciding affairs that range from the curriculum to the behavior code. Lessons are non-compulsory. Neill emphasizes "self-regulation", personal responsibility, freedom from fear, "freedom in sex play", and loving understanding over moral instruction or force. In his philosophy, all attempts to mold children are coercive in nature and therefore harmful. Caretakers are advised to "trust" in the natural process and let children self-regulate such that they live by their own rules and consequently treat with the highest respect the rights of others to live by their own rules. Neill's "self-regulation" constitutes a child's right to "live freely, without outside authority in things psychic and somatic"—that children eat and come of age when they want, are never hit, and are "always loved and protected". Children can do as they please until their actions affect others. In an example, a student can skip French class to play music, but cannot disruptively play music during the French class. Against the popular image of "go as you please schools", Summerhill has many rules. However, they are decided at a schoolwide meeting where students and teachers each have one vote apiece. This does not necessarily mean total cessation to the children, as Neill thought adults were right to bemoan child destruction of property. He considered this tension between adult and child living styles to be natural. Neill felt that most schoolwork and books kept children from their right to play, and that learning should only follow play and not be mixed "to make ork

Ork or ORK may refer to:

* Ork (folklore), a mountain demon of Tyrol folklore

* ''Ork'' (video game), a 1991 game for the Amiga and Atari ST systems

* Ork (''Warhammer 40,000''), a fictional species in the ''Warhammer 40,000'' universe

* ''Ork!'' ...

palatable". Neill found that those students interested in college would complete the prerequisites in two years and of their own volition.

The 45-person coeducational school with pupils aged five to fifteen is presented as successful and having reformed "problem children" into "successful human beings". Some became professionals and academics. In ''Summerhill'', Neill blames many of society's problems on the "miseducation in conventional schools". He felt that society's institutions prevented "real freedom in individuals". Thus, Summerhill was created as a place for children to be free to be themselves. Neill discarded many kinds of dogma ("discipline, ... direction, ... suggestion, ... moral training, .. religious instruction") and put sole faith in the belief of the innate goodness of children.

Reception

The book debuted in America on November 7, 1960 during the week ofJohn F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

's election. At the time of the book's release, Neill was unknown in the United States, and not a single bookseller purchased an advance copy. ''Summerhill'' brought him international renown over the next decade. The book sold 24,000 copies in its first year, 100 thousand in 1968, 200 thousand in 1969, two million total by 1970, and three million by 1973. ''Summerhill'' was included in over 600 American university courses, and a 1969 translation for West Germany (''The Theory and Practice of Anti-Authoritarian Education'') sold over a million copies in three years. In the wake of the book's success, publisher Harold Hart started the American Summerhill Society in New York City, of which Paul Goodman

Paul Goodman (1911–1972) was an American writer and public intellectual best known for his 1960s works of social criticism. Goodman was prolific across numerous literary genres and non-fiction topics, including the arts, civil rights, decen ...

was a founding member.

Multiple reviewers stressed the school's reliance on Neill as a charismatic figure, which begat doubts of the institution's general replicability. Sarah Crutis (''The Times Literary Supplement

''The Times Literary Supplement'' (''TLS'') is a weekly literary review published in London by News UK, a subsidiary of News Corp.

History

The ''TLS'' first appeared in 1902 as a supplement to ''The Times'' but became a separate publication i ...

'') asked whether teachers would have the "time, patience, and personality" to use Neill's methods. "Their extremes of endurance may sometimes sound masochistic", wrote D. W. Harding (''New Statesman

The ''New Statesman'' is a British political and cultural magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first connected with Sidney and Beatrice Webb and other leading members ...

''), and Richard E. Gross (''The Social Studies'') added that Neill's "extremes ... go far beyond good sense". Danica Deutsch ('' Journal of Individual Psychology'') concluded that the school's lessons curbed the child's sense of social responsibility and other society-preserving functions. Jacob Hechler (''Child Welfare'') said that what Neill described as love—a combination of "caring and noninterference"—was very hard to bring to bear. ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues ...

'' called Neill "a fiery crusader" with "deep understanding of children", and Morris Fritz Mayer (''Social Service Review

''Social Service Review'' is an academic journal published by the University of Chicago Press which covers social welfare policy and practice and its effects. It was established in 1927 and the editor-in-chief is Jennifer Mosley (University of Chic ...

'') read Neill as having the "wrath and eloquence of a biblical prophet" with a belief in children and "unyielding attack against pathological and phony values in education" that "one cannot help admiring". Willard W. Hartup (''Contemporary Psychology

''PsycCRITIQUES'' was a database of reviews of books, videos, and popular films published by the American Psychological Association. It replaced the print journal ''Contemporary Psychology: APA Review of Books'', which was published from 1956 to 20 ...

'') positioned Neill as closer to a psychotherapist than a teacher, especially as the philosophy undergirding Summerhill "derives from Freud". Gene Phillips ('' The Annals of the American Academy'') described Neill as the "essential ingredient of the democratic ethic that ... America needs".

Margaret Mead (''American Sociological Review

The ''American Sociological Review'' is a bi-monthly peer-reviewed academic journal covering all aspects of sociology. It is published by SAGE Publications on behalf of the American Sociological Association. It was established in 1936. The editors- ...

'') considered the book more of a historical document for later generations to analyze "than anything that can be taken at its face value". She wrote the school to be "unique" and "counter-pointed to the emphases and excesses" of its era, which she credited to Neill's "rare charismatic personality". To Mead, Summerhill's moral battles had passed since the 1920s, as Neill's audience already agreed with his views on frank discussions about sex and the primacy of student interest. She added that his contemporaries had moved on to "rebelling against a contentless freedom" that prioritized emotional education over intellectual lessons. Similarly, Crutis (''The Times Literary Supplement'') noted Neill's approach as less "sensational" in its method than expected, and asserted that 1960s psychologists would agree with the stance to not guilt children for masturbating and to tell the truth about the origin of babies. Morton Reisman ('' The Phi Delta Kappan'') upheld the book's subtitle and agreed that the book was "radical" in comparison to conventional American morality and education.

Multiple reviewers noted points of overgeneralization in the book. Crutis continued that criticism of individual aspects of the school, such as its stance against uniform curriculum, was justified. R. G. G. Price (''Punch

Punch commonly refers to:

* Punch (combat), a strike made using the hand closed into a fist

* Punch (drink), a wide assortment of drinks, non-alcoholic or alcoholic, generally containing fruit or fruit juice

Punch may also refer to:

Places

* Pun ...

'') remarked that the school was presented as having little intellectual or aesthetic zeal, and that Neill's statement against teaching algebra to eventual repairmen was "the most shameful sentence ever written by an educational pioneer". Hartup (''Contemporary Psychology'') and Harding (''New Statesman'') saw no evidence towards whether Summerhill students were successful by standards other than Neill's, particularly in academic distinction. The '' Saturday Review'' quoted from the British Inspectors report that the school was "unimpressive"—despite laudatory student "will and ... interest, ... their achievements are rather meager." Mead presaged that ''Summerhill'' could create "uncritical behavior" among parents unfamiliar with the pedagogical field, and that the book's "essential positive contribution", belief in child self-regulation, could be forgotten within the book's radicalism.

John Vaizey

John Ernest Vaizey, Baron Vaizey (1 October 1929 – 19 July 1984) was a British author and economist, who specialised in education.

Background and education

Vaizey was the son of Ernest Vernon Vaizey and his wife Lucy Butler Hart. He was educ ...

(''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world.

It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''The ...

'') spotlighted the book's emphasis on "the innate goodness of children" and how the progressive school movement's emphasis on freedom had spread into the public schools. Vaizey put Neill's Summerhill in a disappearing lineage of post-World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

experimental schools that focused on freedom from directed games, classics curriculum, and prudery. He wrote in 1962 that "Summerhill is clearly one of England's greatest schools" and that the decline of this experimental school tradition was a tragedy. Still, Deutsch (''Journal of Individual Psychology'') wrote that Summerhill had not been "duplicated" in the four decades since its creation. ''The Booklist

''Booklist'' is a publication of the American Library Association that provides critical reviews of books and audiovisual materials for all ages. ''Booklist''s primary audience consists of libraries, educators, and booksellers. The magazine is av ...

'' noted Neill's "scant credit" awarded to prior progressive and experimental schools, and added that the addition of a British inspection report added objective credibility to the book. Hartup (''Contemporary Psychology'') described Neill's style as "bewitchingly direct, even epigrammatic" though also "patchy", leaving many discussions incomplete.

Reviewers described the book as both convincing and not. ''The New Yorker'' wrote that skeptical readers would find the book convincing. Crutis (''The Times Literary Supplement'') thought the book would lead readers to ask why "the principles of progressive education" were not more accepted in England. Reisman (''The Phi Delta Kappan'') wrote that even the sections dedicated to the origins of neuroses were "still noteworthy, challenging, and provocative". He wrote that the book's impact is in its "realistic demonstration of how children can be helped to become happy people" without guilt, hate, and fear. On the other hand, the ''Saturday Review'' doubted children wanted or benefitted from lack of adult authority. Hartup (''Contemporary Psychology'') thought that the book, while stimulating, left questions as to its actual contribution past an "experiment in applied psychoanalysis", with "clinical procedure ... alternatively inspired, naive, and hair-raising". He called Neill "an excellent devil's advocate

The (Latin for Devil's advocate) is a former official position within the Catholic Church, the Promoter of the Faith: one who "argued against the canonization ( sainthood) of a candidate in order to uncover any character flaws or misrepresent ...

for educators" but unhelpful in resolving the ailments of mass education.

Harry Elmer Barnes

Harry Elmer Barnes (June 15, 1889 – August 25, 1968) was an American historian who, in his later years, was known for his historical revisionism and Holocaust denial. After receiving a PhD at Columbia University in 1918 Barnes became a pr ...

called the book one of the most exciting and challenging in the field of education since '' Émile''. (This said, Hartup of ''Contemporary Psychology'' said ''Summerhill'' was closer to Freud's ''Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality

''Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality'' (german: Drei Abhandlungen zur Sexualtheorie), sometimes titled ''Three Contributions to the Theory of Sex'', is a 1905 work by Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, in which the author advance ...

'' than to ''Émile'' and criticized Neill's psychoanalytic overemphases.) The psychoanalyst Benjamin Wolstein put Neill's work alongside that of John Dewey

John Dewey (; October 20, 1859 – June 1, 1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer whose ideas have been influential in education and social reform. He was one of the most prominent American scholars in the f ...

, and Sir Herbert Read

Sir Herbert Edward Read, (; 4 December 1893 – 12 June 1968) was an English art historian, poet, literary critic and philosopher, best known for numerous books on art, which included influential volumes on the role of art in education. Read ...

likened Neill to Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (, ; 12 January 1746 – 17 February 1827) was a Swiss pedagogue and educational reformer who exemplified Romanticism in his approach.

He founded several educational institutions both in German- and French-speaking r ...

and Henry Caldwell Cook. David Carr characterized the book as centered on moral education, despite Neill's recurrent insistence on the danger of moral teachings. Scholar Richard Bailey agreed with Carr's characterization.

Legacy

Richard Bailey wrote that the book "marked the birth of an American cult" with Neill and Summerhill at its center as Americans began to emulate the school and form support institutions. Bailey added that ''Summerhill'' style was accessible and humorous compared to the era's moralizing literature, and unpretentious and simple compared to Deweyan thought. The book cornered an education criticism market, and made Neill into a "reluctant" folk leader. Timothy Gray wrote that the book aroused an education reform movement with directives advocated byHerb Kohl

Herbert H. Kohl (born February 7, 1935) is an American businessman and politician. Alongside his brother and father, the Kohl family created the Kohl's department stores chain, of which Kohl went on to be president and CEO. Kohl also served as a ...

, Jonathan Kozol

Jonathan Kozol (born September 5, 1936) is an American writer, progressive activist, and educator, best known for his books on public education in the United States.

Education and experience

Born to Harry Kozol and Ruth (Massell) Kozol, Jonat ...

, Neil Postman

Neil Postman (March 8, 1931 – October 5, 2003) was an American author, educator, media theorist and cultural critic, who eschewed digital technology, including personal computers, mobile devices, and cruise control in cars, and was critical of ...

, and Ivan Illich

Ivan Dominic Illich ( , ; 4 September 1926 – 2 December 2002) was an Austrian Roman Catholic priest, theologian, philosopher, and social critic. His 1971 book '' Deschooling Society'' criticises modern society's institutional approach to edu ...

. Fifty years after the book was first released, Astra Taylor

Astra Taylor (born September 30, 1979) is a Canadian-American documentary filmmaker, writer, activist, and musician. She is a fellow of the Shuttleworth Foundation for her work on challenging predatory practices around debt.

Life

Born in Winni ...

wrote that the idea of ''Summerhill'' selling millions of copies in the 2012 American education climate "seems absurd".

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{Portal bar, Books, Education, England, Schools 1960 non-fiction books Democratic education Pedagogy Sociology of education Books about the philosophy of education British non-fiction books Books about parenting English-language books