Succession To Elizabeth on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The succession to the childless Elizabeth I was an open question from her accession in 1558 to her death in 1603, when the crown passed to

The succession to the childless Elizabeth I was an open question from her accession in 1558 to her death in 1603, when the crown passed to

/ref> he was a partisan of the Earl of Hertford, in right of his wife, the former Lady Catherine Grey. It was related to the efforts of Lord John Grey, Lady Catherine Grey's uncle and guardian, who tried to make the case that she was the royal heir at an early point in Elizabeth's reign, incurring the Queen's wrath. This manuscript brought to bear on the question the old statute ''De natis ultra mare''. It was influential in the following debate, but the interpretation of the statute became important. It also caused a furore, and allegations of a plot. Hales could only be brought to say that he had shown a draft to John Grey, William Fleetwood, the other member of parliament for the same borough, and John Foster, who had been one of the members for Hindon. Walter Haddon called Hales's arrest and the subsequent row the ''Tempestas Halesiana''. What Hales was doing was quite complex, using legal arguments to rule out Scottish claimants, and also relying on research abroad by Robert Beale to reopen the matter of the Hertford marriage.

The arguments naturally changed after Queen Mary's execution. It has been noted that Protestant supporters of James VI took over debating points previously used by her supporters; while Catholics employed some arguments that had been employed by Protestants.

A significant step was taken in Robert Highington's ''Treatise on the Succession'', in favour of the line through the House of Portugal.

Robert Persons's pseudonymous '' Conference about the next Succession to the Crown of England'', by R. Doleman (comprising perhaps co-authors, 1595), was against the claim of James VI. It cited Highington's arguments, against those of Hales and Sir Nicholas Bacon. This work made an apparent effort to discuss candidates equitably, including the Infanta of Spain, Isabella Clara Eugenia. It was taken by some in England to imply that Elizabeth's death could lead to civil war. A preface suggested that Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex might be a decisive influence. The circumstance reflected badly on Essex with the Queen. It also sought to undermine Burghley by suggesting he was a partisan of Arbella Stuart, and dealt acutely with the Lancaster/York issues.

The arguments naturally changed after Queen Mary's execution. It has been noted that Protestant supporters of James VI took over debating points previously used by her supporters; while Catholics employed some arguments that had been employed by Protestants.

A significant step was taken in Robert Highington's ''Treatise on the Succession'', in favour of the line through the House of Portugal.

Robert Persons's pseudonymous '' Conference about the next Succession to the Crown of England'', by R. Doleman (comprising perhaps co-authors, 1595), was against the claim of James VI. It cited Highington's arguments, against those of Hales and Sir Nicholas Bacon. This work made an apparent effort to discuss candidates equitably, including the Infanta of Spain, Isabella Clara Eugenia. It was taken by some in England to imply that Elizabeth's death could lead to civil war. A preface suggested that Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex might be a decisive influence. The circumstance reflected badly on Essex with the Queen. It also sought to undermine Burghley by suggesting he was a partisan of Arbella Stuart, and dealt acutely with the Lancaster/York issues.

The Doleman tract of 1594 suggested one resolution to the succession issue: the Suffolk claimant William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby should marry the Infanta of Spain, and succeed. Stanley, however, married the following year. Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy, son-in-law of Philip II of Spain, became a widower in 1597. Catholic opinion suggested he might marry a female claimant, Lady Anne Stanley (the Earl's niece), if not Arbella Stuart.

The Doleman tract of 1594 suggested one resolution to the succession issue: the Suffolk claimant William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby should marry the Infanta of Spain, and succeed. Stanley, however, married the following year. Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy, son-in-law of Philip II of Spain, became a widower in 1597. Catholic opinion suggested he might marry a female claimant, Lady Anne Stanley (the Earl's niece), if not Arbella Stuart.

The succession to the childless Elizabeth I was an open question from her accession in 1558 to her death in 1603, when the crown passed to

The succession to the childless Elizabeth I was an open question from her accession in 1558 to her death in 1603, when the crown passed to James VI of Scotland

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 ŌĆō 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

. While the accession of James went smoothly, the succession had been the subject of much debate for decades. It also, in some scholarly views, was a major political factor of the entire reign, if not so voiced. Separate aspects have acquired their own nomenclature: the "Norfolk conspiracy", and Patrick Collinson's "Elizabethan exclusion crisis".

The topics of debate remained obscured by uncertainty.

Elizabeth I balked at establishing the order of succession in any form, presumably because she feared for her own life once a successor was named. She was also concerned with England forming a productive relationship with Scotland, but whose Catholic and Presbyterian strongholds were resistant to female leadership. Catholic women who would be submissive to the Pope and not to English constitutional law were rejected.

Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

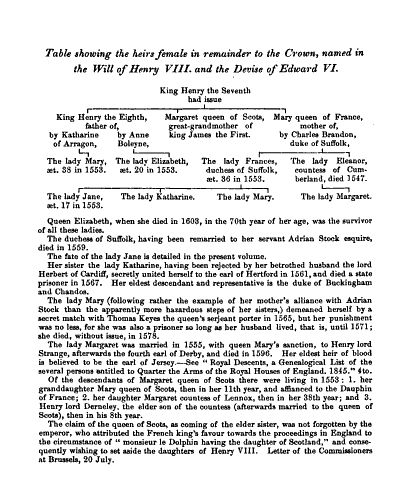

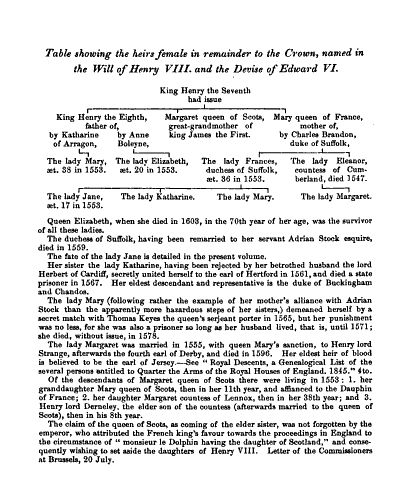

's will had named one male and seven females living at his death in 1547 as the line of succession: (1) his son Edward VI, (2) Mary I, (3) Elizabeth I, (4) Jane Grey, (5) Katherine Grey, (6) Mary Grey, and (7) Margaret Clifford.

The legal position was held by a number of authorities to hinge on such matters as the statute '' De natis ultra mare'' of Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 ŌĆō 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

, and the will of Henry VIII. Their application raised different opinions. Political, religious and military matters came to predominate later in Elizabeth's reign, in the context of the Anglo-Spanish War.

Cognatic descent from Henry VII

Descent from the two daughters of Henry VII who reached adulthood,Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, ╬╝╬▒Žü╬│╬▒Žü╬»Žä╬ĘŽé () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular througho ...

and Mary, was the first and main issue in the succession.

Lennox claim

Mary I of England

Mary I (18 February 1516 ŌĆō 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. Sh ...

had died without managing to have her preferred successor and first cousin, Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox, nominated by parliament. Margaret Douglas was a daughter of Margaret Tudor, and lived to 1578, but became a marginal figure in discussions of the succession to Elizabeth I, who at no point clarified the dynastic issues of the Tudor line. When in 1565 Margaret Douglas's elder son Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, married Mary, Queen of Scots, the "Lennox claim" was generally regarded as consolidated into the "Stuart claim".

Stuart claimants

James VI was the son of two grandchildren of Margaret Tudor. Arbella Stuart, the most serious other contender by the late 16th century, was the daughter of Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox's younger son Charles Stuart, 1st Earl of Lennox. James VI's mother, Mary, Queen of Scots, was considered a plausible successor to the English throne. At the beginning of Elizabeth's reign she sent ambassadors to England when a parliament was summoned, anticipating a role for parliament in settling the succession in her favour. Mary was a Roman Catholic, and her proximity to the succession was a factor in plotting, making her position a political problem for the English government, eventually resolved by judicial means. She was executed in 1587. In that year Mary's son James reached the age of twenty-one, while Arbella was only twelve.Suffolk claimants

While the Stuart line of James and Arbella would have had political support, by 1600 the descendants of Mary Tudor were theoretically relevant, and on legal grounds could not be discounted. Frances Grey, Duchess of Suffolk, and Eleanor Clifford, Countess of Cumberland, both had children who were in the line of succession. Frances and Eleanor were Mary Tudor's daughters by her second husband, Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk. Frances married Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Suffolk, and they had three daughters,Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey ( 1537 ŌĆō 12 February 1554), later known as Lady Jane Dudley (after her marriage) and as the "Nine Days' Queen", was an English noblewoman who claimed the throne of England and Ireland from 10 July until 19 July 1553.

Jane was ...

(1537ŌĆō1554), Lady Catherine Grey (1540ŌĆō1568), and Lady Mary Grey (1545ŌĆō1578). Of these, the two youngest lived into Queen Elizabeth's reign.

Catherine's first marriage to the youthful Henry Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, a political match, was annulled, and there were no children. She married Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford covertly in 1560. The couple were separately imprisoned in the Tower of London after Catherine became pregnant. There were two sons of the marriage, but both were decided by the established Church of England to be illegitimate. After Catherine's death in 1568, Seymour was released. The elder boy became Edward Seymour, Viscount Beauchamp; the younger was named Thomas. The "Beauchamp claim" was more insistently kept up by Thomas, relying on a defence against the ruling of illegitimacy available to him, but not to his elder brother. He died in 1600. Rumours after Elizabeth's death showed that the Beauchamp claim was not forgotten.

Lady Mary Grey married, without royal permission, Thomas Keyes, and had no sons. She completely lacked interest in royal pretensions.

The family of Eleanor Clifford was more often talked of in relation to the succession. A daughter Margaret Stanley, Countess of Derby lived to have two sons, Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby and William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby. At the period when Margaret Stanley might have been considered a succession candidate, her name was usually "Margaret Strange", based on her husband's courtesy title of Lord Strange. Her Catholic support was drawn off by the Stuart claim. Just before his death in 1593, however, the claim of her husband Henry Stanley, 4th Earl of Derby was being promoted by Sir William Stanley and William Allen William Allen may refer to:

Politicians

United States

*William Allen (congressman) (1827ŌĆō1881), United States Representative from Ohio

* William Allen (governor) (1803ŌĆō1879), U.S. Representative, Senator, and 31st Governor of Ohio

* Willia ...

.

Ferdinando's position in the succession then led to his being approached in the superficial Hesketh plot

Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby (1559 – 16 April 1594), was an English nobleman and politician. He was the son of Henry Stanley, 4th Earl of Derby, and Lady Margaret Clifford. Ferdinando had a place in the line of succession to Eliza ...

to seize power, in September 1593. His daughter Anne Stanley, Countess of Castlehaven

Anne Stanley (May 1580 – c. 8 October 1647) was an English noblewoman. She was the eldest daughter of the Earl of Derby and, through her two marriages, became Baroness Chandos and later Countess of Castlehaven. She was a distant relative o ...

, played a part in the legalistic and hypothetical discussions of the succession.

Yorkist claimant

There was some interest early in the reign of Queen Elizabeth in a claimant from theHouse of York

The House of York was a cadet branch of the English royal House of Plantagenet. Three of its members became kings of England in the late 15th century. The House of York descended in the male line from Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, ...

. Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, could make a claim only based on the idea that Henry VII was a usurper, rather than a legitimate king, but he had some supporters, ahead of the Tudor, Stuart and Suffolk lines. Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, a survivor of the Plantagenets, was his great-grandmother (on his mother's side), and her paternal grandfather was Richard, Duke of York. The Spanish diplomat Álvaro de la Quadra, on whose accounts the early intrigues round the succession have been reconstructed, considered that Robert Dudley Robert Dudley is the name of:

Surname

* Robert Dudley (actor) (1869ŌĆō1955), American dentist and film character actor

*Robert Dudley (explorer) (1574ŌĆō1649), illegitimate son of the 1st Earl of Leicester

*Robert Charles Dudley (1826ŌĆō1909) wate ...

, brother-in-law to Hastings, was pushing the Queen in March 1560 to make Hastings her successor, against his wishes. There were also some pretensions from his relations in the Pole family.

Lancastrian claim through John of Gaunt

The major political issue of the reign ofRichard II of England

Richard II (6 January 1367 ŌĆō ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father die ...

, that his uncle, the magnate John of Gaunt

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (6 March 1340 ŌĆō 3 February 1399) was an English royal prince, military leader, and statesman. He was the fourth son (third to survive infancy as William of Hatfield died shortly after birth) of King Edward ...

, would claim the throne and so overturn the principle of primogeniture

Primogeniture ( ) is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit the parent's entire or main estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relativ ...

, was revived in the context of the Elizabethan succession, after seven generations. John of Gaunt's eldest daughter having married into the Portuguese House of Aviz

The House of Aviz (Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''Casa de Avis''), also known as the Joanine Dynasty (''Dinastia Joanina''), was a dynasty of Portuguese people, Portuguese origin which flourished during the Portuguese Renaissance, Renaissance ...

, one of his descendants was the Infanta of Spain, Isabella Clara Eugenia

Isabella Clara Eugenia ( es, link=no, Isabel Clara Eugenia; 12 August 1566 ŌĆō 1 December 1633), sometimes referred to as Clara Isabella Eugenia, was sovereign of the Spanish Netherlands in the Low Countries and the north of modern France with ...

. The legitimacy of Isabella's claim was seriously put forward, on the Catholic side of the argument. A reason given for Essex's Rebellion was that the Infanta's claim had gained traction with Elizabeth and her counsellors.

Succession Act of 1543

TheSuccession to the Crown Act 1543

The Third Succession Act of King Henry VIII's reign, passed by the Parliament of England in July 1543, returned his daughters Mary and Elizabeth to the line of the succession behind their half-brother Edward. Born in 1537, Edward was the son of ...

was the third such act of the reign of Henry VIII. It endorsed the provisions of Henry's last will (whatever they were) in assigning the order of succession, after Elizabeth's death. It in consequence supported in parliamentary terms the succession claims of Lady Catherine Grey, Protestant and born in England, over those of Mary, Queen of Scots. Further, it meant that the Stuart claimants were disadvantaged, compared to the Suffolk claimants, though James VI was descended from the older daughter of Henry VII.

Setting aside the will would have, in fact, threatened the prospects of James VI, by opening up a fresh legal front. It indeed specified the preference for descendants of Mary, rather than Margaret. However, in its absence, the matter of the succession could not be handled as an issue under statute law. If it were left to the common law, the question of how James, an alien, could inherit could be raised in a more serious form.

There was no comparable Act of Parliament in Elizabeth's time. She did not follow the precedent set by her father in allowing parliamentary debate on the subject of the succession but instead actively tried to close it down throughout her reign. Paul Wentworth

Paul Wentworth (1533ŌĆō1593), a prominent English member of parliament (1559, 1563 and 1572) in the reign of Elizabeth I, was a member of the Lillingstone Lovell branch of the family.

Life

His father Sir Nicholas Wentworth (died 1557) was chi ...

explicitly challenged her position on the matter in questions put to the House of Commons in 1566.

In 1563, William Cecil drafted a bill envisaging the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

having wide powers if the Queen died without an heir, but he did not put it forward. Parliament petitioned the Queen to name her successor, but she did not do so. A Bill was passed by Parliament in 1572, but the Queen refused her assent. In the early 1590s, Peter Wentworth attempted to bring up the question again, but debate was shut down sharply. The matter surfaced mainly in drama.

Succession tracts

Discussion of the succession was strongly discouraged and became dangerous, but it was not entirely suppressed. During the last two decades of the century, thePrivy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

was active against pamphlets and privately circulated literature on the topic. John Stubbs

John Stubbs (or Stubbe) (c. 1544 ŌĆō after 25 September 1589) was an English pamphleteer, political commentator and sketch artist during the Elizabethan era.

He was born in the County of Norfolk, and was educated at Trinity College, Cambridge. ...

, who published on the closely related issue of the queen's marriage, avoided execution in 1579 but had a hand cut off and was in the Tower of London until 1581. In that year, Parliament passed the Act against Seditious Words and Rumours Uttered against the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty. The publication of books deemed seditious became a felony.

Much of the writing was therefore anonymous; in manuscript form or, in the case of Catholic arguments, smuggled into the country. Some was published in Scotland. '' Leicester's Commonwealth'' (1584), for example, an illegally circulated tract attacking the queen's favourite Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, devoted much of its space to arguing for the succession rights of Mary, Queen of Scots.

A number of treatises, or "succession tracts", circulated. Out of a large literature on the question, Edward Edwards picked five of the tracts that were major contributions. That by Hales reflected a Puritan view (it has been taken to be derived from John Ponet); and it to a large extent set the terms of the later debate. The other four developed the cases for Catholic successors.

The Hales tract

John Hales John Hales may refer to:

*John Hales (theologian) (1584ŌĆō1656), English theologian

* John Hales (bishop of Exeter) from 1455 to 1456

*John Hales (bishop of Coventry and Lichfield) (died 1490) from 1459 to 1490

* John Hales (died 1540), MP for Cante ...

wrote a speech to give in the House of Commons in 1563;historyofparliamentonline.org, ''Hales, John I (d. 1572), of Coventry, Warws. and London.''/ref> he was a partisan of the Earl of Hertford, in right of his wife, the former Lady Catherine Grey. It was related to the efforts of Lord John Grey, Lady Catherine Grey's uncle and guardian, who tried to make the case that she was the royal heir at an early point in Elizabeth's reign, incurring the Queen's wrath. This manuscript brought to bear on the question the old statute ''De natis ultra mare''. It was influential in the following debate, but the interpretation of the statute became important. It also caused a furore, and allegations of a plot. Hales could only be brought to say that he had shown a draft to John Grey, William Fleetwood, the other member of parliament for the same borough, and John Foster, who had been one of the members for Hindon. Walter Haddon called Hales's arrest and the subsequent row the ''Tempestas Halesiana''. What Hales was doing was quite complex, using legal arguments to rule out Scottish claimants, and also relying on research abroad by Robert Beale to reopen the matter of the Hertford marriage.

Francis Newdigate

Sir Francis Alexander Newdigate Newdegate, (31 December 1862 ŌĆō 2 January 1936) was an English Conservative Party politician. After over twenty years in the House of Commons, he served as Governor of Tasmania from 1917 to 1920, and Governor ...

, who had married Anne Seymour, Duchess of Somerset

Anne Seymour, Duchess of Somerset (n├®e Stanhope; before 1512 ŌĆō 16 April 1587) was the second wife of Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset (c. 1500ŌĆō1552), who held the office of lord protector during the first part of the reign of their ...

, was involved in the investigation, but was not imprisoned; Hales was. He spent a year in the Fleet Prison and the Tower of London, and for the rest of his life was under house arrest

In justice and law, house arrest (also called home confinement, home detention, or, in modern times, electronic monitoring) is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to their residence. Travel is usually restricted, if all ...

.

The case for a Catholic successor

Early tracts

John Lesley

John Lesley (or Leslie) (29 September 1527 ŌĆō 31 May 1596) was a Scottish Roman Catholic bishop and historian. His father was Gavin Lesley, rector of Kingussie, Badenoch.

Early career

He was educated at the University of Aberdeen, where he ...

wrote on behalf of Mary, Queen of Scots. ''A defence of the honour of the right high, mightye and noble Princess Marie'' (1569) had its London printing prevented by Lord Burghley. It raised, in particular, the tensions between the Succession Act of 1543 and the actual wills left by Henry VIII. Elizabeth would not accept the implied degree of parliamentary control of the succession. Further discussion of the succession was prohibited by statute, from 1571. A related work, by Thomas Morgan (as supposed), or Morgan Philipps

Morgan Phillips (also Philipps or Philippes) (died 1570) was a Welsh Roman Catholic priest and a benefactor of Douai College.

Life

Born in Monmouthshire, Phillips entered the University of Oxford in 1533, graduating B.A. on 18 February 1538; h ...

(supposed), for Mary, Queen of Scots, was another printing of Lesley's work, in 1571. Lesley's arguments in fact went back to Edmund Plowden, and had been simplified by Anthony Browne.

The Doleman tract

The arguments naturally changed after Queen Mary's execution. It has been noted that Protestant supporters of James VI took over debating points previously used by her supporters; while Catholics employed some arguments that had been employed by Protestants.

A significant step was taken in Robert Highington's ''Treatise on the Succession'', in favour of the line through the House of Portugal.

Robert Persons's pseudonymous '' Conference about the next Succession to the Crown of England'', by R. Doleman (comprising perhaps co-authors, 1595), was against the claim of James VI. It cited Highington's arguments, against those of Hales and Sir Nicholas Bacon. This work made an apparent effort to discuss candidates equitably, including the Infanta of Spain, Isabella Clara Eugenia. It was taken by some in England to imply that Elizabeth's death could lead to civil war. A preface suggested that Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex might be a decisive influence. The circumstance reflected badly on Essex with the Queen. It also sought to undermine Burghley by suggesting he was a partisan of Arbella Stuart, and dealt acutely with the Lancaster/York issues.

The arguments naturally changed after Queen Mary's execution. It has been noted that Protestant supporters of James VI took over debating points previously used by her supporters; while Catholics employed some arguments that had been employed by Protestants.

A significant step was taken in Robert Highington's ''Treatise on the Succession'', in favour of the line through the House of Portugal.

Robert Persons's pseudonymous '' Conference about the next Succession to the Crown of England'', by R. Doleman (comprising perhaps co-authors, 1595), was against the claim of James VI. It cited Highington's arguments, against those of Hales and Sir Nicholas Bacon. This work made an apparent effort to discuss candidates equitably, including the Infanta of Spain, Isabella Clara Eugenia. It was taken by some in England to imply that Elizabeth's death could lead to civil war. A preface suggested that Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex might be a decisive influence. The circumstance reflected badly on Essex with the Queen. It also sought to undermine Burghley by suggesting he was a partisan of Arbella Stuart, and dealt acutely with the Lancaster/York issues.

Other literature

The plot of ''Gorboduc

Gorboduc (''Welsh:'' Gorwy or Goronwy) was a legendary king of the Britons as recounted by Geoffrey of Monmouth. He was married to Judon. When he became old, his sons, Ferrex and Porrex, feuded over who would take over the kingdom. Porrex tried ...

'' (1561) has often been seen as a contribution to the succession debate. This view, as expounded by Axton, has led to much further debate. The play was given for the queen in 1562, and later published. Stephen Alford argues that it is a generalised "succession text", with themes of bad counsel and civil war. From the point of view of Elizabethan and Jacobean literary criticism, it has been argued that it is significant to know when the succession was "live" as an issue of public concern, right into the reign of James I, and in what form drama, in particular, might be expressing comment on it. In particular, Hopkins points out that ''Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

'' and '' King Lear'', both relating to legitimacy and dynastic politics, were written in the early years of James's reign.

The term "succession play" is now widely applied to dramas of the period that relate to a royal succession. Plays mentioned in this way include, among other works by Shakespeare, '' Hamlet''; '' Henry V''; ''A Midsummer Night's Dream

''A Midsummer Night's Dream'' is a comedy written by William Shakespeare 1595 or 1596. The play is set in Athens, and consists of several subplots that revolve around the marriage of Theseus and Hippolyta. One subplot involves a conflict amon ...

'' through allegory and the figure of Titania; and ''Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 ŌĆō ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father died ...

'' as an atypical case. Another, later play that might be read in this way is ''Perkin Warbeck

Perkin Warbeck ( 1474 ŌĆō 23 November 1499) was a pretender to the English throne claiming to be Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, who was the second son of Edward IV and one of the so-called "Princes in the Tower". Richard, were he alive, ...

'' (1634) by John Ford.

The poet Michael Drayton alluded to the succession in ''Englands Heroicall Epistles'' (1597), in a way now seen as heavy-handed dabbling in politics. In it, imaginary letters in couplets are exchanged by paired historical characters. Hopkins sees the work as a "genealogical chain" leading up to the succession issue, and points out the detailed discussion of the Yorkist claim, in the annotations to the epistles between Margaret of Anjou

Margaret of Anjou (french: link=no, Marguerite; 23 March 1430 ŌĆō 25 August 1482) was Queen of England and nominally Queen of France by marriage to King Henry VI from 1445 to 1461 and again from 1470 to 1471. Born in the Duchy of Lorrain ...

and William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk (thought in Drayton's time to have been lovers).

Position at the end of the century

Theories on the putative succession had to be revised constantly from the later 1590s. The speculations were wide, and the cast of characters changed their status. The Doleman tract of 1594 suggested one resolution to the succession issue: the Suffolk claimant William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby should marry the Infanta of Spain, and succeed. Stanley, however, married the following year. Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy, son-in-law of Philip II of Spain, became a widower in 1597. Catholic opinion suggested he might marry a female claimant, Lady Anne Stanley (the Earl's niece), if not Arbella Stuart.

The Doleman tract of 1594 suggested one resolution to the succession issue: the Suffolk claimant William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby should marry the Infanta of Spain, and succeed. Stanley, however, married the following year. Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy, son-in-law of Philip II of Spain, became a widower in 1597. Catholic opinion suggested he might marry a female claimant, Lady Anne Stanley (the Earl's niece), if not Arbella Stuart.

Thomas Wilson Thomas Wilson, Tom Wilson or Tommy Wilson may refer to:

Actors

* Thomas F. Wilson (born 1959), American actor most famous for his role of Biff Tannen in the ''Back to the Future'' trilogy

*Tom Wilson (actor) (1880ŌĆō1965), American actor

*Dan Gre ...

wrote in a report ''The State of England, Anno Domini 1600'' that there were 12 "competitors" for the succession. His counting included two Stuarts (James and Arbella), three of the Suffolks (two Beauchamp claimants and the Earl of Derby), and George Hastings, 4th Earl of Huntingdon, younger brother of the 3rd Earl mentioned above. The other six were:

*Charles Neville, 6th Earl of Westmorland

Charles Neville, 6th Earl of Westmorland (18 August 154216 November 1601) was an English nobleman and one of the leaders of the Rising of the North in 1569.

He was the son of Henry Neville, 5th Earl of Westmorland and Lady Anne Manners, second d ...

via John of Gaunt

* Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland via Edmund Crouchback

* Ant├│nio, Prior of Crato, nephew of Henry, King of Portugal

Henry ( pt, Henrique ; 31 January 1512 ŌĆö 31 January 1580), dubbed the Chaste ( pt, o Casto, links=no) and the Cardinal-King ( pt, o Cardeal-Rei, links=no), was king of Portugal and a Cardinal (Catholic Church), cardinal of the Catholic Church, ...

, via John of Gaunt; and with related claims

* Ranuccio I Farnese, Duke of Parma

* Philip III of Spain

*The Infanta of Spain.

These six may have all been taken as the Catholic candidates (Percy was not in fact a Catholic, though from a Catholic family). Wilson at the time of writing (about 1601) had been working on intelligence matters for Lord Buckhurst and Sir Robert Cecil.

Of these supposed claimants, Thomas Seymour and Charles Neville died in 1600. None of the Iberian claims came to anything. The Duke of Parma was the subject of the same speculations as the Duke of Savoy; but he married in 1600. Arbella Stuart was in the care of Bess of Hardwick, and Edward Seymour in the care of Richard Knightley, whose second wife Elizabeth was one of his sisters.

See also

* Alternative successions of the English crownNotes

References

{{reflist Elizabeth I Elizabeth I