Stork Club on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Stork Club was a

Hard times began for the Stork Club in 1956, when it lost money for the first time. In 1957, unions tried once again to organize the club's employees. Their major effort 10 years before had been unsuccessful; at that time, Sherman Billingsley was accused of attempting to influence his employees to stay out of the union with lavish staff parties and financial gifts. By 1957, all other similar New York clubs except the Stork Club were unionized. This met with resistance from Billingsley and many dependable employees left the Stork Club over his refusal to allow them to be represented by a union. Picket lines were set up and marched in front of the club daily for years, including the club's last day of business. The club received many threats connected to his refusal to accept unions for his workers; some of the threats involved Billingsley's family. In 1957, he was arrested for displaying a gun when some painters who were working at the Austrian Consulate next to the family's home sat on his stoop for lunch. Billingsley admitted to acting rashly because of the threats. Three months before his arrest, his secretary was assaulted as she was entering the building where she lived; her assailants made references to the union issues at the Stork Club.

As a result of the union dispute, many club patrons no longer visited the night spot. Those who were performers were informed of the possibility of fines and suspensions by their respective unions for crossing the Stork Club picket line as the issue continued. Many of Billingsley's friendships, including those of Walter Winchell and J. Edgar Hoover, were over as a result of the union problems. He began firing staff without good cause. As the dispute dragged on, a live band was also no longer in the dining room for music; members of the Musicians' Union had crossed the picket line to perform for some time. Previously, the club had no need for advertising; it was mentioned frequently in print and word of mouth without it. In 1963, the club offered a hamburger and French fries for $1.99 in a ''New York Times'' advertisement; when those in the know about the club saw it, they realized the Stork Club's days were coming to an end. In the last few months of its operation, at times, only three customers came in for the entire evening. On a good day in the mid-1940s, some 2,500 people visited the club.

Hard times began for the Stork Club in 1956, when it lost money for the first time. In 1957, unions tried once again to organize the club's employees. Their major effort 10 years before had been unsuccessful; at that time, Sherman Billingsley was accused of attempting to influence his employees to stay out of the union with lavish staff parties and financial gifts. By 1957, all other similar New York clubs except the Stork Club were unionized. This met with resistance from Billingsley and many dependable employees left the Stork Club over his refusal to allow them to be represented by a union. Picket lines were set up and marched in front of the club daily for years, including the club's last day of business. The club received many threats connected to his refusal to accept unions for his workers; some of the threats involved Billingsley's family. In 1957, he was arrested for displaying a gun when some painters who were working at the Austrian Consulate next to the family's home sat on his stoop for lunch. Billingsley admitted to acting rashly because of the threats. Three months before his arrest, his secretary was assaulted as she was entering the building where she lived; her assailants made references to the union issues at the Stork Club.

As a result of the union dispute, many club patrons no longer visited the night spot. Those who were performers were informed of the possibility of fines and suspensions by their respective unions for crossing the Stork Club picket line as the issue continued. Many of Billingsley's friendships, including those of Walter Winchell and J. Edgar Hoover, were over as a result of the union problems. He began firing staff without good cause. As the dispute dragged on, a live band was also no longer in the dining room for music; members of the Musicians' Union had crossed the picket line to perform for some time. Previously, the club had no need for advertising; it was mentioned frequently in print and word of mouth without it. In 1963, the club offered a hamburger and French fries for $1.99 in a ''New York Times'' advertisement; when those in the know about the club saw it, they realized the Stork Club's days were coming to an end. In the last few months of its operation, at times, only three customers came in for the entire evening. On a good day in the mid-1940s, some 2,500 people visited the club.

When the Stork Club initially closed its doors, news stories indicated it was being shut because the building it occupied had been sold and a new location was being sought. The years of labor disputes had taken their toll on Billingsley financially. Trying to keep the Stork Club going took all of his assets and about $10 million from his three daughters' trust funds. While in the hospital recuperating from a serious illness in October 1965, Billingsley sold the building to

When the Stork Club initially closed its doors, news stories indicated it was being shut because the building it occupied had been sold and a new location was being sought. The years of labor disputes had taken their toll on Billingsley financially. Trying to keep the Stork Club going took all of his assets and about $10 million from his three daughters' trust funds. While in the hospital recuperating from a serious illness in October 1965, Billingsley sold the building to

From the physical layout of the club, as described by Ed Sullivan in a 1939 column, the Stork should have been doomed to failure, since it was strangely shaped and far from roomy in places. The club's ladies' room was on the second floor of the structure and the men's room was on the third; only the dining room, bar, and later the Cub Room were on the first floor. Despite this, the club could hold 1,000 guests. A feature of the club was a solid 14-karat gold chain at its entrance; patrons were allowed entry through it by the doorman. When the East 53rd Street building came down to make way for Paley Park, one of the artifacts found in it was a

From the physical layout of the club, as described by Ed Sullivan in a 1939 column, the Stork should have been doomed to failure, since it was strangely shaped and far from roomy in places. The club's ladies' room was on the second floor of the structure and the men's room was on the third; only the dining room, bar, and later the Cub Room were on the first floor. Despite this, the club could hold 1,000 guests. A feature of the club was a solid 14-karat gold chain at its entrance; patrons were allowed entry through it by the doorman. When the East 53rd Street building came down to make way for Paley Park, one of the artifacts found in it was a

Billingsley's original plan for the Cub Room was for it to be a private place for playing gin rummy with his friends. The room was added to the club during World War II. Billingsley broke out a wall in the bar to create this private space, but it was Walter Winchell who began to call it the Cub Room. The Cub Room had no windows and was described in a

Billingsley's original plan for the Cub Room was for it to be a private place for playing gin rummy with his friends. The room was added to the club during World War II. Billingsley broke out a wall in the bar to create this private space, but it was Walter Winchell who began to call it the Cub Room. The Cub Room had no windows and was described in a

nightclub

A nightclub (music club, discothèque, disco club, or simply club) is an entertainment venue during nighttime comprising a dance floor, lightshow, and a stage for live music or a disc jockey (DJ) who plays recorded music.

Nightclubs gener ...

in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

, New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

. During its existence from 1929 to 1965, it was one of the most prestigious clubs in the world. A symbol of café society

Café society was the description of the "Beautiful People" and "Bright Young Things" who gathered in fashionable cafés and restaurants in New York, Paris and London beginning in the late 19th century. Maury Henry Biddle Paul is credited with ...

, the wealthy elite, including movie stars, celebrities, showgirl

A showgirl is a female dancer or performer in a stage entertainment show intended to showcase the performer's physical attributes, typically by way of revealing clothing, toplessness, or nudity.

History

Showgirls date back to the late 180 ...

s, and aristocrats all mixed in the VIP Cub Room of the club. The club was established on West 58th Street in 1929 by Sherman Billingsley

John Sherman Billingsley (March 10, 1896 – October 4, 1966) was an American nightclub owner and former bootlegger who was the founder and owner of New York's Stork Club.

Life and career

John Sherman Billingsley was the youngest child of ...

, a former bootlegger from Enid, Oklahoma

Enid ( ) is the ninth-largest city in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. It is the county seat of Garfield County. As of the 2020 census, the population was 51,308. Enid was founded during the opening of the Cherokee Outlet in the Land Run of 1893, a ...

. After an incident when Billingsley was kidnapped and held for ransom by Mad Dog Coll

Vincent "Mad Dog" Coll (born Uinseann Ó Colla, July 20, 1908 – February 8, 1932) was an Irish-American mob hitman in the 1920s and early 1930s in New York City. Coll gained notoriety for the allegedly accidental killing of a young child dur ...

, a rival of his mobster partners, he became the sole owner of the Stork Club. The club remained at its original location until it was raided by Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcohol ...

agents in 1931. After the raid, it moved to East 51st Street. From 1934 until its closure in 1965, it was located at 3 East 53rd Street

53rd Street is a Midtown Manhattan, midtown cross street in the New York City borough (New York City), borough of Manhattan, that runs adjacent to buildings such as the Citigroup Center, Citigroup building. It is 1.83 miles (2.94 km) ...

, just east of Fifth Avenue, when it became world-renowned with its celebrity clientele and luxury. Billingsley was known for his lavish gifts, which brought a steady stream of celebrities to the club and also ensured that those interested in the famous would have a reason to visit.

Until World War II, the club consisted of a dining room and bar with restrooms on upper floors with many mirrors and fresh flowers throughout. Billingsley originally built the well-known Cub Room as a private place where he could play cards with friends. Described as a "lopsided oval", the room had wood paneled walls hung with portraits of beautiful women and had no windows. A head waiter known as "Saint Peter" determined who was allowed entry to the Cub Room, where Walter Winchell

Walter Winchell (April 7, 1897 – February 20, 1972) was a syndicated American newspaper gossip columnist and radio news commentator. Originally a vaudeville performer, Winchell began his newspaper career as a Broadway reporter, critic and co ...

wrote his columns and broadcast his radio programs from Table 50.

During the years of its operation, the club was visited by many political, social, and celebrity figures. It counted among its guests the Kennedy and Roosevelt families, and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. The news of Grace Kelly's engagement to Prince Rainier

Rainier III (Rainier Louis Henri Maxence Bertrand Grimaldi; 31 May 1923 – 6 April 2005) was Prince of Monaco from 1949 to his death in 2005. Rainier ruled the Principality of Monaco for almost 56 years, making him one of the longest-ruling m ...

of Monaco

Monaco (; ), officially the Principality of Monaco (french: Principauté de Monaco; Ligurian: ; oc, Principat de Mónegue), is a sovereign city-state and microstate on the French Riviera a few kilometres west of the Italian region of Lig ...

broke while the couple were visiting the Stork Club. Socialite Evalyn Walsh McLean, owner of the Hope Diamond

The Hope Diamond is a diamond originally extracted in the 17th century from the Kollur Mine in Guntur, India. It is blue in color due to trace amounts of boron. Its exceptional size has revealed new information about the formation of diamonds. ...

, once lost the gem under a Stork Club table during an evening visit to the club. Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century f ...

was able to cash his $100,000 check for the film rights of ''For Whom the Bell Tolls'' at the Stork Club to settle his bill.

In the 1940s, workers of the Stork Club desired to be represented by a union, and by 1957, the employees of all similar New York venues were union members. However, Billingsley was still unwilling to allow his workers to organize, which led to union supporters picketing in front of the club for many years until its closure. During this time, many of the club's celebrity and non-celebrity guests stopped visiting the Stork Club; it closed in 1965 and was demolished the following year. The site is now the location of Paley Park

Paley Park is a pocket park located at 3 East 53rd Street between Madison and Fifth Avenues in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, on the former site of the Stork Club. Designed by the landscape architectural firm of Zion Breen Richardson Associat ...

, a small vest-pocket park.

History

Early history

The Stork Club was owned and operated by Sherman Billingsley (1896–1966) an ex- bootlegger who came to New York from Enid, Oklahoma. The ''Stork Club'' first opened in 1929 at 132 West 58th Street, just down the street from Billingsley's apartment at 152 West 58th Street. Billingsley's handwritten recollections of the early days recall that he was approached by two gamblers he knew from Oklahoma in his New York real estate office, proposing to open a restaurant together, which he accepted. The origin of the name of the club is unknown; Billingsley once remarked, "Don't ask me how or why I picked the name, because I just don't remember." New York City'sEl Morocco

El Morocco (sometimes nicknamed Elmo or Elmer) was a 20th-century Manhattan nightclub frequented by the rich and famous from the 1930s until the decline of café society in the late 1950s. It was famous for its blue zebra-stripe motif (designed ...

had the sophistication and Toots Shor's drew the sporting crowd, but the Stork Club mixed power, money, and glamor. Unlike its competitors, the Stork stayed open on Sunday nights and during the summer.

One of the first Stork Club customers was writer Heywood Broun, who resided in the vicinity. Broun's first visit to the Stork was actually made by mistake; he believed it to be a funeral home

A funeral home, funeral parlor or mortuary, is a business that provides burial and funeral services for the dead and their families. These services may include a prepared wake and funeral, and the provision of a chapel for the funeral.

Services ...

, but he soon became a regular, and invited his celebrity friends, as the name of the club spread further afield. Before long, Billingsley's Oklahoma partners sold their shares to a man named Thomas Healy. Eventually, Healy revealed that he was a " front" for three New York mobsters. Billingsley was kidnapped and held for ransom by Mad Dog Coll

Vincent "Mad Dog" Coll (born Uinseann Ó Colla, July 20, 1908 – February 8, 1932) was an Irish-American mob hitman in the 1920s and early 1930s in New York City. Coll gained notoriety for the allegedly accidental killing of a young child dur ...

, who was a rival of his mob partners. Before the ransom money could be collected by Coll, he was lured to a telephone booth, where he was shot to death. After the incident, the secret gangster partners reluctantly allowed Billingsley to buy them out for $30,000.

Another New York nightclub owner, Texas Guinan

Mary Louise Cecilia "Texas" Guinan (January 12, 1884 – November 5, 1933) was an American actress, producer and entrepreneur. Born in Texas to Irish immigrant parents, Guinan decided at an early age to become an entertainer. After becoming a st ...

, introduced Billingsley to her friend, the entertainment and gossip columnist Walter Winchell, in 1930. In September 1930, Winchell called the Stork Club "New York's New Yorkiest place on W. 58th" in his ''New York Daily Mirror

The ''New York Daily Mirror'' was an American morning tabloid newspaper first published on June 24, 1924, in New York City by the William Randolph Hearst organization as a contrast to their mainstream broadsheets, the ''Evening Journal'' and ''N ...

'' column. That evening, the Stork Club was filled with moneyed guests. Someone else who read Winchell's column in 1930 was singer-actress Helen Morgan, who had just finished filming a movie on Long Island. Morgan decided to hold a cast party at the Stork Club, paying the tab with two $1,000 bills. Winchell became a regular at the Stork Club; what he saw and heard there at his private Table 50 was the basis of his newspaper columns and radio broadcasts. Billingsley also kept professionals on his staff whose job was to listen to the chatter, determine fact from rumor, and then report the factual news to local columnists. The practice was seen as protective of the patrons by shielding them from unfounded reports, and also a continual source of publicity for the club. Billingsley's long-standing relationship with Ethel Merman

Ethel Merman (born Ethel Agnes Zimmermann, January 16, 1908 – February 15, 1984) was an American actress and singer, known for her distinctive, powerful voice, and for leading roles in musical theatre.Obituary '' Variety'', February 22, 1984. ...

, which began in 1939, brought the theater crowd to the Stork; there, she had a waiter assigned to her whose job was just to light her cigarettes. Billingsley later wrote that Merman had offered him $500,000 to leave his wife and that he turned down the offer.

Prohibition agents closed the original club on December 22, 1931, and Billingsley moved it to East 51st Street for three years. It was raided on August 29, 1932, at the 51st Street location after an angry patron lost a quarter A quarter is one-fourth, , 25% or 0.25.

Quarter or quarters may refer to:

Places

* Quarter (urban subdivision), a section or area, usually of a town

Placenames

* Quarter, South Lanarkshire, a settlement in Scotland

* Le Quartier, a settlement ...

in a coin machine and notified police. The police asked guests to quietly pay their checks and leave the building; this took two hours. In 1934, the Stork Club moved to 3 East 53rd Street, where it remained until it closed in October 1965. Billingsley's guest list for the 53rd Street opening consisted of people from Broadway and Park Avenue. He sent out 1,000 invitations for champagne and dinner. The women found much to like about the fresh flowers everywhere and the mirrored walls, while the men were pleased to see their favorite dishes on the club's menu, as well as many of their personal and business friends at the opening. When the Stork Club became a tenant in 1934, the building was known as the Physicians and Surgeons Building. Many of the medical tenants were unhappy about the night club moving in, but in February 1946, Billingsley purchased the seven-story building for $300,000 cash, evicting the doctors to expand the club.

By 1936, the Stork was doing well enough to have a million-dollar gross for the first time. Young debutante Brenda Frazier made her first visit to the Stork Club in the spring of 1938; she became a regular, bringing many young people from the society set with her. Billingsley welcomed young people who were not old enough to drink. He encouraged them to gather at the Stork Club by inviting debutantes to the club and holding a yearly "Glamor Girl" election. As the father of three daughters, Billingsley kept an eye on the young people, making sure they were not served alcohol and that they were able to have an enjoyable time at the Stork Club without it.

The Stork Club previously provided live entertainment, but after Billingsley realized the reason people came to the club was to watch people, he abandoned the floor shows in favor of giving expensive gifts to regular customers of the club. A live band was provided in the main dining room for dancing. Billingsley had a keen sense for business. Before he purchased the building where the Stork Club was, the yearly rent for the space it occupied was $12,000. Billingsley rented out the hat- and coat-check area to a separate concession for $27,000 a year. This paid the rent for the Stork Club, leaving $15,000 annually to cover bad checks. When Ernest Hemingway wanted to pay his bill with a $100,000 check he received for the movie rights to ''For Whom the Bell Tolls'', Billingsley told him he would be able to cash the check after the club closed at 4:00 am. He kept the ''Stork Club's'' name vivid in the minds of his patrons through mailing lists and a club newsletter. Billingsley was also aware of the need for a good working relationship with the press; food and drink for reporters and photographers assigned to cover the Stork Club were on the house.

Controversies

Tax raid

In early 1944, New York mayorFiorello H. La Guardia

Fiorello Henry LaGuardia (; born Fiorello Enrico LaGuardia, ; December 11, 1882September 20, 1947) was an American attorney and politician who represented New York in the House of Representatives and served as the 99th Mayor of New York City fro ...

ordered a check on the books of all major city night clubs. City tax accountants soon investigated the Stork Club, the Copacabana, and other city night spots. By July, auditors turned in a report claiming that the clubs were overcharging patrons on tax, sending the city the proper amount, and keeping the overbilled sums. One Saturday in July, city officials arrived at the Stork Club with a court order granting permission for them to seize the club's property for the amount that was claimed to be overcharged as taxes, plus penalties. The total for the Stork Club was $181,000. Billingsley, out of town with his family, was notified. The club's employees refused to turn anything over to the officials, who were intent on closing it.

Upon his return, Billingsley firmly protested that the Stork Club did not owe the city any money and was up to date on its tax payments. A compromise was reached: the club could stay open as long as a custodian for the city was allowed to be on the premises. Billingsley was eventually able to get a court order to eject the custodian, but the case dragged on for five years, costing Billingsley $100,000.

Josephine Baker

On October 19, 1951,Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker (born Freda Josephine McDonald; naturalised French Joséphine Baker; 3 June 1906 – 12 April 1975) was an American-born French dancer, singer and actress. Her career was centered primarily in Europe, mostly in her adopted Fran ...

made charges of racism against the Stork Club. Baker visited the club on October 16 as the guest of Roger Rico and his wife; both entertainers were at the Stork after their theater performances. Baker said she ordered a steak and was apparently still waiting for it an hour later. The controversy grew when Baker accused Walter Winchell of being in the Cub Room at the time and not coming to her aid. Winchell was at the club; he said he had greeted Baker and vocalist Roger Rico as the two left their Cub Room table. Winchell said he was not aware of there being any problem, and left for a late screening of the film '' The Desert Fox''. The next morning, Winchell's rumored failure to assist Baker was big news, and he received countless telephone calls. The incident blew into a major scandal and was widely publicized on the radio and newspapers. Mrs. Rico, who was part of the Baker party with her husband, said that Baker's steak was waiting for her at the table after she returned from her phone call, but the entertainer chose to make a stormy exit from the Stork anyhow. News accounts show conflicting statements from the Ricos.

Walter Winchell's name, along with those of Billingsley and the Stork Club, was further tarnished by the incident. After leaving the Stork, the Baker party made contact with WMCA WMCA may refer to:

*WMCA (AM), a radio station operating in New York City

* West Midlands Combined Authority, the combined authority of the West Midlands metropolitan county in the United Kingdom

*Wikimedia Canada

The Wikimedia Foundation, ...

's Barry Gray

Barry Gray (born John Livesey Eccles; 18 July 1908 – 26 April 1984) was a British musician and composer best known for his collaborations with television and film producer Gerry Anderson.

Life and career

Born into a musical family in Blackburn ...

, where the story was told as part of Gray's radio talk show. One of those who phoned Gray's program was television personality and columnist Ed Sullivan

Edward Vincent Sullivan (September 28, 1901 – October 13, 1974) was an American television personality, impresario, sports and entertainment reporter, and syndicated columnist for the ''New York Daily News'' and the Chicago Tribune New Yor ...

, a professional rival of Winchell's whose "home base" was the El Morocco nightclub. Sullivan's on-air remarks dealt mainly with Winchell's alleged part in the event, saying, "What Winchell has done is an insult to the United States and American newspapermen." Winchell's column of October 24, 1951, provides the same details as earlier news stories about Josephine Baker's accusations that he did not assist her at the Stork Club. Winchell also printed a letter he received from Walter White Walter White most often refers to:

* Walter White (''Breaking Bad''), character in the television series ''Breaking Bad''

* Walter Francis White (1893–1955), American leader of the NAACP

Walter White may also refer to:

Fictional characters ...

, who was the executive secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. ...

(NAACP) at the time, although Billingsley alleged the letter was a forgery.

The controversy prompted a fake bomb threat, as well as a NAACP protest outside the Stork Club. A New York police investigation of the matter followed the complaint made by the NAACP. The police investigation found that the Stork Club did not discriminate against Josephine Baker. The NAACP went on to say that the results of the police investigation did not provide enough evidence for the organization to pursue the incident further in criminal court. Baker filed suit against Winchell over the matter, but the suit was dismissed in 1955. Walter Winchell later said. "The Stork Club discriminates against everybody. White, black, and pink. The Stork bars all kinds of people for all kinds of reasons. But if your skin is green and you're rich and famous or you're syndicated, you'll be welcome at the club."

Bugging rumor

Because of Billingsley's long-standing friendship withFederal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

(FBI) head J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation � ...

, rumors persisted that the Stork Club was bugged. During his work on the Stork Club book, author and ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' reporter Ralph Blumenthal was contacted by Jean-Claude Baker, one of Josephine Baker's sons. Having read an article by Blumenthal about Leonard Bernstein's FBI file, he indicated that he had read his mother's FBI file and by comparing the file to the tapes, said he thought the Stork Club incident was overblown.

Union issues and closure

Hard times began for the Stork Club in 1956, when it lost money for the first time. In 1957, unions tried once again to organize the club's employees. Their major effort 10 years before had been unsuccessful; at that time, Sherman Billingsley was accused of attempting to influence his employees to stay out of the union with lavish staff parties and financial gifts. By 1957, all other similar New York clubs except the Stork Club were unionized. This met with resistance from Billingsley and many dependable employees left the Stork Club over his refusal to allow them to be represented by a union. Picket lines were set up and marched in front of the club daily for years, including the club's last day of business. The club received many threats connected to his refusal to accept unions for his workers; some of the threats involved Billingsley's family. In 1957, he was arrested for displaying a gun when some painters who were working at the Austrian Consulate next to the family's home sat on his stoop for lunch. Billingsley admitted to acting rashly because of the threats. Three months before his arrest, his secretary was assaulted as she was entering the building where she lived; her assailants made references to the union issues at the Stork Club.

As a result of the union dispute, many club patrons no longer visited the night spot. Those who were performers were informed of the possibility of fines and suspensions by their respective unions for crossing the Stork Club picket line as the issue continued. Many of Billingsley's friendships, including those of Walter Winchell and J. Edgar Hoover, were over as a result of the union problems. He began firing staff without good cause. As the dispute dragged on, a live band was also no longer in the dining room for music; members of the Musicians' Union had crossed the picket line to perform for some time. Previously, the club had no need for advertising; it was mentioned frequently in print and word of mouth without it. In 1963, the club offered a hamburger and French fries for $1.99 in a ''New York Times'' advertisement; when those in the know about the club saw it, they realized the Stork Club's days were coming to an end. In the last few months of its operation, at times, only three customers came in for the entire evening. On a good day in the mid-1940s, some 2,500 people visited the club.

Hard times began for the Stork Club in 1956, when it lost money for the first time. In 1957, unions tried once again to organize the club's employees. Their major effort 10 years before had been unsuccessful; at that time, Sherman Billingsley was accused of attempting to influence his employees to stay out of the union with lavish staff parties and financial gifts. By 1957, all other similar New York clubs except the Stork Club were unionized. This met with resistance from Billingsley and many dependable employees left the Stork Club over his refusal to allow them to be represented by a union. Picket lines were set up and marched in front of the club daily for years, including the club's last day of business. The club received many threats connected to his refusal to accept unions for his workers; some of the threats involved Billingsley's family. In 1957, he was arrested for displaying a gun when some painters who were working at the Austrian Consulate next to the family's home sat on his stoop for lunch. Billingsley admitted to acting rashly because of the threats. Three months before his arrest, his secretary was assaulted as she was entering the building where she lived; her assailants made references to the union issues at the Stork Club.

As a result of the union dispute, many club patrons no longer visited the night spot. Those who were performers were informed of the possibility of fines and suspensions by their respective unions for crossing the Stork Club picket line as the issue continued. Many of Billingsley's friendships, including those of Walter Winchell and J. Edgar Hoover, were over as a result of the union problems. He began firing staff without good cause. As the dispute dragged on, a live band was also no longer in the dining room for music; members of the Musicians' Union had crossed the picket line to perform for some time. Previously, the club had no need for advertising; it was mentioned frequently in print and word of mouth without it. In 1963, the club offered a hamburger and French fries for $1.99 in a ''New York Times'' advertisement; when those in the know about the club saw it, they realized the Stork Club's days were coming to an end. In the last few months of its operation, at times, only three customers came in for the entire evening. On a good day in the mid-1940s, some 2,500 people visited the club.

When the Stork Club initially closed its doors, news stories indicated it was being shut because the building it occupied had been sold and a new location was being sought. The years of labor disputes had taken their toll on Billingsley financially. Trying to keep the Stork Club going took all of his assets and about $10 million from his three daughters' trust funds. While in the hospital recuperating from a serious illness in October 1965, Billingsley sold the building to

When the Stork Club initially closed its doors, news stories indicated it was being shut because the building it occupied had been sold and a new location was being sought. The years of labor disputes had taken their toll on Billingsley financially. Trying to keep the Stork Club going took all of his assets and about $10 million from his three daughters' trust funds. While in the hospital recuperating from a serious illness in October 1965, Billingsley sold the building to Columbia Broadcasting System

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS, the abbreviation of its former legal name Columbia Broadcasting System, is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainme ...

(CBS), which turned the site into a park named after its founder's father. In a 1937 interview, Billingsley said, "I hope I'll be running a night club the last day I live." On October 4, 1966, Sherman Billingsley died of a heart attack at his Manhattan apartment. He was planning on re-opening the Stork Club at another location and was working on writing a book at the time of his death.

Interior

From the physical layout of the club, as described by Ed Sullivan in a 1939 column, the Stork should have been doomed to failure, since it was strangely shaped and far from roomy in places. The club's ladies' room was on the second floor of the structure and the men's room was on the third; only the dining room, bar, and later the Cub Room were on the first floor. Despite this, the club could hold 1,000 guests. A feature of the club was a solid 14-karat gold chain at its entrance; patrons were allowed entry through it by the doorman. When the East 53rd Street building came down to make way for Paley Park, one of the artifacts found in it was a

From the physical layout of the club, as described by Ed Sullivan in a 1939 column, the Stork should have been doomed to failure, since it was strangely shaped and far from roomy in places. The club's ladies' room was on the second floor of the structure and the men's room was on the third; only the dining room, bar, and later the Cub Room were on the first floor. Despite this, the club could hold 1,000 guests. A feature of the club was a solid 14-karat gold chain at its entrance; patrons were allowed entry through it by the doorman. When the East 53rd Street building came down to make way for Paley Park, one of the artifacts found in it was a still

A still is an apparatus used to distill liquid mixtures by heating to selectively boil and then cooling to condense the vapor. A still uses the same concepts as a basic distillation apparatus, but on a much larger scale. Stills have been use ...

. The New York Historical Society displayed that along with other ''Stork Club'' items and memorabilia in an exhibit in 2000.

Billingsley's hospitality with food, drink, and gifts overcame the structural deficits to keep his patrons returning time after time. He maintained order through a series of hand signals; without saying a word he could order complimentary drinks and gifts for a party at any given table. Billingsley was also able to summon the club's private limousine to whisk favored customers away to a theater date or a ballgame after drinks or dining at the Stork. He changed the meaning of the hand signals frequently to avoid regular patrons' being able to read them. Guests dined on the finest wines and cuisine, and it was known for its Champagne and caviar. The club gained worldwide attention for its cocktails, made by chief barman Nathaniel "Cookie" Cook, who invented dozens of cocktails at the bar, including the signature "Stork Club Cocktail". The ornamental bar of the Stork Club was subsequently relocated to Jim Brady's Bar on Maiden Lane, which acquired the bar at auction in the mid-1970s and continued to operate until the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identi ...

in 2020. The dining room featured live bands for dancing; the Benny Goodman orchestra were frequent performers. According to a 1960 Services Labor Report, the kitchen and dining room employees working in the Stork Club did "not enjoy the same wages, hours and working conditions" as the others, a primary factor which led the majority of them to the strike in January 1957.

Besides the Cub Room, the Main Dining Room, and the bar, the club contained a room for parties, the "Blessed Event Room", a large private room on the second floor with its own kitchen and bar, the "Loner's Room", which was just past the Cub Room and much like a men's club, and a private barber shop. When the Blessed Event Room was added to the Stork Club, its walls were entirely mirrored. Patrons who had rented the room for poker parties complained that the mirrors allowed players to see everyone's hand of cards

A hand is a prehensile, multi-fingered appendage located at the end of the forearm or forelimb of primates such as humans, chimpanzees, monkeys, and lemurs. A few other vertebrates such as the koala (which has two opposable thumbs on each ...

; the mirrors were then removed from the walls.

The Cub Room

Billingsley's original plan for the Cub Room was for it to be a private place for playing gin rummy with his friends. The room was added to the club during World War II. Billingsley broke out a wall in the bar to create this private space, but it was Walter Winchell who began to call it the Cub Room. The Cub Room had no windows and was described in a

Billingsley's original plan for the Cub Room was for it to be a private place for playing gin rummy with his friends. The room was added to the club during World War II. Billingsley broke out a wall in the bar to create this private space, but it was Walter Winchell who began to call it the Cub Room. The Cub Room had no windows and was described in a Louis Sobol

Louis Sobol (August 10, 1896 – February 9, 1986) was a journalist, Broadway gossip columnist, and radio host. Sobol wrote for Hearst newspapers for forty years, and was considered one of the country's most popular columnists. Sobol wrote about ...

column as a "lopsided oval". The room was lit with pink tones. On the wood-paneled walls were paintings of beautiful women; Billingsley also had similar portraits by the same artist in the ladies' powder room. After the club's labor problems began in 1957, Billingsley redecorated the entire club, choosing emerald green for the carpet and chairs, and a pinkish-red for the banquette

A banquette is a small footpath or elevated step along the inside of a rampart or parapet of a fortification. Musketeers atop it were able to view the counterscarp

A scarp and a counterscarp are the inner and outer sides, respectively, of a ...

s. The Cub Room's wood panels were replaced by beige burlap and the portraits of beautiful women were replaced by paintings of noted 19th-century race horses. As a concession to those who wanted to have a business lunch at The Stork, the Cub Room was for men only during lunch time. The ''sanctum sanctorum

The Latin phrase ''sanctum sanctorum'' is a translation of the Hebrew term ''קֹדֶשׁ הַקֳּדָשִׁים'' (Qṓḏeš HaQŏḏāšîm), literally meaning Holy of Holies, which generally refers in Latin texts to the holiest place of th ...

'', the Cub Room ("the snub room"), was guarded by a captain called "Saint Peter" (for the saint who guards the gates of Heaven).

The most famous of the Cub Room's headwaiters was John "Jack" Spooner, who was well known to many celebrities from his previous duties at LaHiff's. Billingsley recruited him in 1934 after the death of Billy Lahiff and the subsequent closure of his club. Spooner began an autograph book for his daughter, Amelia, while working at LaHiff's. Billingsley encouraged him to bring "The Book" to the Stork Club, where stars continued to sign it. Some who were famous illustrators or cartoonists such as E. C. Segar

Elzie Crisler Segar (; December 8, 1894 – October 13, 1938), known by the pen name E. C. Segar, was an American cartoonist best known as the creator of Popeye, a pop culture character who first appeared in 1929 in Segar's comic strip ''Thimble ...

(''Popeye''), Chic Young

Murat Bernard "Chic" Young (January 9, 1901March 14, 1973) was an American cartoonist who created the comic strip '' Blondie''. His 1919 ''William McKinley High School Yearbook'' cites his nickname as Chicken, source of his familiar pen name an ...

(''Blondie''), and Theodor Geisel ("Dr. Seuss

Theodor Seuss Geisel (;"Seuss"

'' At Christmas, Spooner dressed as Santa Claus, posing for photos with old and young alike.

Author T. C. McNult has referred to the Stork Club during its existence as "the most celebrated nightspot in the world"; while author Ed McMahon has called it the "most realistic nightclub of all", a name "synonymous with fame, class, and money, in no particular order". Society writer

Author T. C. McNult has referred to the Stork Club during its existence as "the most celebrated nightspot in the world"; while author Ed McMahon has called it the "most realistic nightclub of all", a name "synonymous with fame, class, and money, in no particular order". Society writer

Guests were expected to dress to high standards, with men wearing evening suits and the women wearing "gowns with silk gloves reaching the elbow". All women in full evening dress received an orchid or gardenia corsage, compliments of the Stork Club. A requirement for all men was a necktie; those who were not wearing one were either lent one or had to buy one to gain admittance. Although African Americans were not explicitly barred from entry, there was a mutual understanding that they were not welcome. Billingsley insisted on orderly conduct for all of his Stork Club guests; fighting, drunkenness, or rowdiness were prohibited. He ran the club on the principle of it being a place where people could have a good time and that it was somewhere he could bring his own family without worrying that they would see or hear something he did not want them to. Billingsley closely controlled the seating placement system in the club. Unescorted women were not allowed to enter the club after 6:00 p.m; this was a protective measure for men who may have been out with someone other than their wives.

Several celebrities did not abide by the rules and were banned from the club. Humphrey Bogart was banned after a prolonged "shouting match" with Billingsley. Milton Berle was officially barred for too much table-hopping, shouting, and doing handsprings in the club; Berle contended that the real reason was because of a Stork Club satire he had recently performed on his television program. Elliott Roosevelt, the so-called "black sheep of the club", became unwelcome at the club through an apparent misunderstanding. Billingsley had planned an engagement party for Roosevelt and his girlfriend, vocalist Gigi Durston, on the basis of the couple's friends' statements that they were going to be married. Durston had once worked at the Stork Club as a singer and Roosevelt was a longtime customer of the club. Billingsley sent out publicity notices about the party; the couple told him that they had no plans to announce their engagement at that time. Roosevelt was banned from the Stork and the party was canceled.

Guests were expected to dress to high standards, with men wearing evening suits and the women wearing "gowns with silk gloves reaching the elbow". All women in full evening dress received an orchid or gardenia corsage, compliments of the Stork Club. A requirement for all men was a necktie; those who were not wearing one were either lent one or had to buy one to gain admittance. Although African Americans were not explicitly barred from entry, there was a mutual understanding that they were not welcome. Billingsley insisted on orderly conduct for all of his Stork Club guests; fighting, drunkenness, or rowdiness were prohibited. He ran the club on the principle of it being a place where people could have a good time and that it was somewhere he could bring his own family without worrying that they would see or hear something he did not want them to. Billingsley closely controlled the seating placement system in the club. Unescorted women were not allowed to enter the club after 6:00 p.m; this was a protective measure for men who may have been out with someone other than their wives.

Several celebrities did not abide by the rules and were banned from the club. Humphrey Bogart was banned after a prolonged "shouting match" with Billingsley. Milton Berle was officially barred for too much table-hopping, shouting, and doing handsprings in the club; Berle contended that the real reason was because of a Stork Club satire he had recently performed on his television program. Elliott Roosevelt, the so-called "black sheep of the club", became unwelcome at the club through an apparent misunderstanding. Billingsley had planned an engagement party for Roosevelt and his girlfriend, vocalist Gigi Durston, on the basis of the couple's friends' statements that they were going to be married. Durston had once worked at the Stork Club as a singer and Roosevelt was a longtime customer of the club. Billingsley sent out publicity notices about the party; the couple told him that they had no plans to announce their engagement at that time. Roosevelt was banned from the Stork and the party was canceled.

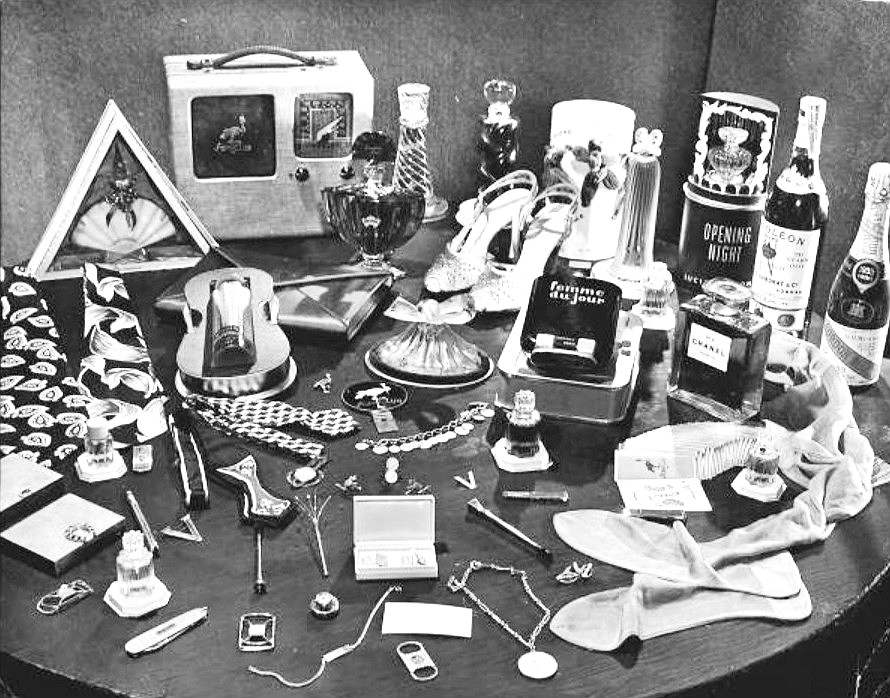

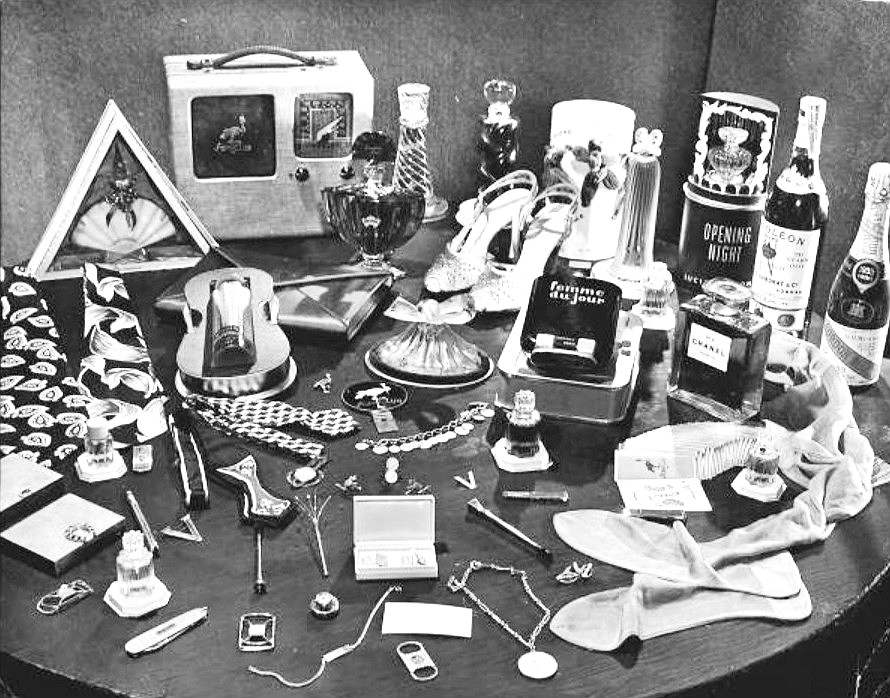

Owner Billingsley was well known for his extravagant gifts presented to his favorite patrons, spending an average of $100,000 a year on them. They included compacts studded with diamonds and rubies, French perfumes, Champagne and liquor, and even automobiles. Many of the gifts were specially made for the Stork Club, with the club's name and logo on them. Some of the best known examples were the gifts of ''Sortilège'' perfume by Le Galion, which became known as the "fragrance of the Stork Club". Billingsley convinced

Owner Billingsley was well known for his extravagant gifts presented to his favorite patrons, spending an average of $100,000 a year on them. They included compacts studded with diamonds and rubies, French perfumes, Champagne and liquor, and even automobiles. Many of the gifts were specially made for the Stork Club, with the club's name and logo on them. Some of the best known examples were the gifts of ''Sortilège'' perfume by Le Galion, which became known as the "fragrance of the Stork Club". Billingsley convinced  Sunday night was "Balloon Night". As is common with New Year's celebrations, balloons were held on the ceiling of the Main Dining Room by a net and the net would open at the stroke of midnight. As the balloons came down, the ladies would begin frantically trying to catch them. Each contained a number and a drawing would be held for the prizes, which ranged from charms for bracelets to automobiles; there were also at least three $100 bills folded and placed randomly in the balloons.

Billingsley's generosity was not confined to those who were always at the club. He received the following letter in 1955: "I am grateful to you for your thoughtful kindness in sending me such a generous selection of attractive neckties. At the same time may I once again thank you for the cigars that you regularly send to the White House." It was signed by

Sunday night was "Balloon Night". As is common with New Year's celebrations, balloons were held on the ceiling of the Main Dining Room by a net and the net would open at the stroke of midnight. As the balloons came down, the ladies would begin frantically trying to catch them. Each contained a number and a drawing would be held for the prizes, which ranged from charms for bracelets to automobiles; there were also at least three $100 bills folded and placed randomly in the balloons.

Billingsley's generosity was not confined to those who were always at the club. He received the following letter in 1955: "I am grateful to you for your thoughtful kindness in sending me such a generous selection of attractive neckties. At the same time may I once again thank you for the cigars that you regularly send to the White House." It was signed by

A ''

A ''

Inside the Cub Room at the Stork Club

Alfred Eisenstaedt's 1944 Stork Club photos for LIFE magazine

{{Restaurants in Manhattan 1929 establishments in New York City 1965 disestablishments in New York (state) Defunct drinking establishments in Manhattan Defunct restaurants in New York City Midtown Manhattan Nightlife in New York City Nightclubs in Manhattan Restaurants established in 1929 Speakeasies

'' At Christmas, Spooner dressed as Santa Claus, posing for photos with old and young alike.

Clientele and image

Author T. C. McNult has referred to the Stork Club during its existence as "the most celebrated nightspot in the world"; while author Ed McMahon has called it the "most realistic nightclub of all", a name "synonymous with fame, class, and money, in no particular order". Society writer

Author T. C. McNult has referred to the Stork Club during its existence as "the most celebrated nightspot in the world"; while author Ed McMahon has called it the "most realistic nightclub of all", a name "synonymous with fame, class, and money, in no particular order". Society writer Lucius Beebe

Lucius Morris Beebe (December 9, 1902 – February 4, 1966) was an American writer, gourmand, photographer, railroad historian, journalist, and syndicated columnist.

Early life and education

Beebe was born in Wakefield, Massachusetts, to a prom ...

wrote in 1946: "To millions and millions of people all of over the world the Stork symbolizes and epitomizes the ''de luxe'' upholstery of quintessentially urban existence. It means fame; it means wealth; it means an elegant way of life among celebrated folk". The club was a prime example of the flourishing cafe society at the time, but the real purpose of the Stork Club, according to journalist Ed Sullivan, was people watching other people, particularly non-celebrities watching celebrities. Author Mearl L. Allen, however, highlights that the club was more than a celebrity playground, and that "many decisions of tremendous social and economic importance regarding world affairs were made in the Stork Club during this time", and the likes of Desi Arnaz

Desiderio Alberto Arnaz y de Acha III (March 2, 1917 – December 2, 1986) was a Cuban-born American actor, bandleader, and film and television producer. He played Ricky Ricardo on the American television sitcom '' I Love Lucy'', in which he c ...

and Lucille Ball

Lucille Désirée Ball (August 6, 1911 – April 26, 1989) was an American actress, comedienne and producer. She was nominated for 13 Primetime Emmy Awards, winning five times, and was the recipient of several other accolades, such as the Golde ...

could often be seen conversing with executive types. Mark Bernardo, author of ''Mad Men's Manhattan: The Insider's Guide'', has said: "In some ways, the Stork Club was ahead of its time—courting celebrities by picking up their tabs, hiring a house photographer who sent candid shots of guests to the tabloids, and offering a private enclave called the Cub Room, where stars could huddle away from the prying eyes of fans, all hallmarks of modern clubs that cater to boldface names". The venue was usually packed with luminaries during its golden years, and dining orders could take a long time to be dealt with.

Notable guests through the years included Lucille Ball

Lucille Désirée Ball (August 6, 1911 – April 26, 1989) was an American actress, comedienne and producer. She was nominated for 13 Primetime Emmy Awards, winning five times, and was the recipient of several other accolades, such as the Golde ...

, Tallulah Bankhead

Tallulah Brockman Bankhead (January 31, 1902 – December 12, 1968) was an American actress. Primarily an actress of the stage, Bankhead also appeared in several prominent films including an award-winning performance in Alfred Hitchcock's '' L ...

, Joan Blondell

Joan Blondell (born Rose Joan Bluestein; August 30, 1906 – December 25, 1979) was an American actress who performed in film and television for 50 years.

Blondell began her career in vaudeville. After winning a beauty pageant, she embarked on ...

, Charlie Chaplin, Frank Costello

Frank Costello (; born Francesco Castiglia; ; January 26, 1891 – February 18, 1973) was an Italian-American crime boss of the Luciano crime family. In 1957, Costello survived an assassination attempt ordered by Vito Genovese and carried out by ...

, Bing Crosby, the Duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are rank ...

and Duchess of Windsor

Wallis, Duchess of Windsor (born Bessie Wallis Warfield, later Simpson; June 19, 1896 – April 24, 1986), was an American socialite and wife of the former King Edward VIII. Their intention to marry and her status as a divorcée caused a ...

, Brenda Frazier, Ava Gardner

Ava Lavinia Gardner (December 24, 1922 – January 25, 1990) was an American actress. She first signed a contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1941 and appeared mainly in small roles until she drew critics' attention in 1946 with her perform ...

, Artie Shaw

Artie Shaw (born Arthur Jacob Arshawsky; May 23, 1910 – December 30, 2004) was an American clarinetist, composer, bandleader, actor and author of both fiction and non-fiction.

Widely regarded as "one of jazz's finest clarinetists", Shaw led ...

, Dorothy Frooks

Dorothy Frooks (February 12, 1896 – April 13, 1997) was an American writer, publisher, military officer, lawyer, and suffragist. She also ran for Congress twice, in 1920 as a member of the Prohibition Party and in 1934 on the Law Pre ...

, Carmen Miranda

Carmen Miranda, (; born Maria do Carmo Miranda da Cunha, 9 February 1909 – 5 August 1955) was a Portuguese-born Brazilian samba singer, dancer, Broadway actress and film star who was active from the late 1920s onwards. Nicknamed "The Br ...

, Dana Andrews

Carver Dana Andrews (January 1, 1909 – December 17, 1992) was an American film actor who became a major star in what is now known as film noir. A leading man during the 1940s, he continued acting in less prestigious roles and character parts ...

, Michael O'Shea, Judy Garland

Judy Garland (born Frances Ethel Gumm; June 10, 1922June 22, 1969) was an American actress and singer. While critically acclaimed for many different roles throughout her career, she is widely known for playing the part of Dorothy Gale in '' The ...

, the Harrimans, Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century f ...

, Judy Holliday

Judy Holliday (born Judith Tuvim, June 21, 1921 – June 7, 1965) was an American actress, comedian and singer.Obituary '' Variety'', June 9, 1965, p. 71.

She began her career as part of a nightclub act before working in Broadway plays and mus ...

, J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation � ...

, Grace Kelly

Grace Patricia Kelly (November 12, 1929 – September 14, 1982) was an American actress who, after starring in several significant films in the early to mid-1950s, became Princess of Monaco by marrying Prince Rainier III in April 1956.

Kelly ...

, the Kennedys, Dorothy Kilgallen, Dorothy Lamour

Dorothy Lamour (born Mary Leta Dorothy Slaton; December 10, 1914 – September 22, 1996) was an American actress and singer. She is best remembered for having appeared in the '' Road to...'' movies, a series of successful comedies starring Bing ...

, Robert M. McBride, Vincent Price

Vincent Leonard Price Jr. (May 27, 1911 – October 25, 1993) was an American actor, art historian, art collector and gourmet cook. He appeared on stage, television, and radio, and in more than 100 films. Price has two stars on the Hollywood Wal ...

, Marilyn Monroe

Marilyn Monroe (; born Norma Jeane Mortenson; 1 June 1926 4 August 1962) was an American actress. Famous for playing comedic " blonde bombshell" characters, she became one of the most popular sex symbols of the 1950s and early 1960s, as wel ...

, the Nordstrom Sisters, Erik Rhodes, the Roosevelts, Elaine Stritch

Elaine Stritch (February 2, 1925 – July 17, 2014) was an American actress, best known for her work on Broadway and later, television. She made her professional stage debut in 1944 and appeared in numerous stage plays, musicals, feature films a ...

, Ramón Rivero, J. D. Salinger, Frank Sinatra, Elizabeth Taylor, Gene Tierney

Gene Eliza Tierney (November 19, 1920 – November 6, 1991) was an American film and stage actress. Acclaimed for her great beauty, she became established as a leading lady. Tierney was best known for her portrayal of the title character in the ...

, Mike Todd

Michael Todd (born Avrom Hirsch Goldbogen; June 22, 1909 – March 22, 1958) was an American theater and film producer, best known for his 1956 production of '' Around the World in 80 Days'', which won an Academy Award for Best Picture. Act ...

, and Gloria Vanderbilt.

The main room of the club was also frequented by many of the prominent figures that had fled Europe, from royals to businessmen, debutantes, sportsmen and military dignitaries, who often, upon departing, took with them the signature ashtrays of the club as souvenirs. The news of Grace Kelly's engagement to Prince Rainier of Monaco broke at the Stork. The couple was at the club on Tuesday, January 3, 1956, as the rumors flew. Veteran columnist Jack O'Brian passed Kelly a note, saying that reliable sources indicated she was about to become engaged to the Prince. Kelly replied she could not answer the question posed by O'Brian until Friday. Socialite Evalyn Walsh McLean

Evalyn McLean ( Walsh; August 1, 1886 – April 26, 1947) was an American mining heiress and socialite, famous for reputedly being the last private owner of the Hope Diamond (which was bought in 1911 for US$180,000 from Pierre Cartier), as we ...

, owner of the Hope Diamond

The Hope Diamond is a diamond originally extracted in the 17th century from the Kollur Mine in Guntur, India. It is blue in color due to trace amounts of boron. Its exceptional size has revealed new information about the formation of diamonds. ...

, wore the gem as if it was costume jewelry. It disappeared at the Stork Club one night during McLean's visit there. Actress Beatrice Lillie found it under one of the club's tables. Actor Warren Oates

Warren Mercer Oates (July 5, 1928 – April 3, 1982) was an American actor best known for his performances in several films directed by Sam Peckinpah, including ''The Wild Bunch'' (1969) and ''Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia'' (1974). A ...

once worked at the club as a dishwasher.

Conduct

Jackie Gleason

John Herbert Gleason (February 26, 1916June 24, 1987) was an American actor, comedian, writer, composer, and conductor known affectionately as "The Great One." Developing a style and characters from growing up in Brooklyn, New York, he was know ...

, who was a frequent guest of the club with his two daughters, was being seated with a female companion when the couple was asked to leave the premises in March 1957. Billingsley claimed that Gleason's conversation became loud and off-color when he arrived at a table and barred Gleason from the Stork Club for life. Gleason said that he had done nothing wrong. He wondered if the problem was because he was a member of the Musicians' Union, since the club's wait and kitchen staff had been on strike since January of that year.

Despite the rules and banishments, there were incidents which made their way into newspapers. Billingsley associate Steve Hannagan believed that one "good fight" a year was permissible for a respectable night club. Johnny Weissmuller

Johnny Weissmuller (born Johann Peter Weißmüller; June 2, 1904 – January 20, 1984) was an American Olympic swimmer, water polo player and actor. He was known for having one of the best competitive swimming records of the 20th century. H ...

accused a Navy lieutenant of using a lit cigarette to burn the clothing of dancers as they passed his table. The lieutenant advised Weissmuller to get a haircut; his wife told Weissmuller to go back to Hollywood with the other ape-men. The Navy man suffered two black eyes and complained that Weissmuller's friends held him as he was punched by Weissmuller. Ernest Hemingway once took issue with a stranger who slapped him on the back; knocking him into three chairs and a table as he brushed him away. Billingsley contended that many of the incidents that appeared in print were minor disagreements which were inflated by the press.

Jack Benny

Jack Benny (born Benjamin Kubelsky, February 14, 1894 – December 26, 1974) was an American entertainer who evolved from a modest success playing violin on the vaudeville circuit to one of the leading entertainers of the twentieth century wit ...

invited longtime friend, writer, and performer Goodman Ace

Goodman Ace (January 15, 1899 – March 25, 1982), born Goodman Aiskowitz, was an American humorist, radio writer and comedian, television writer, and magazine columnist.

His low-key, literate drollery and softly tart way of tweaking trends ...

to lunch with him at the Stork. Ace arrived at the club first and received the "cold shoulder

"Cold shoulder" is a phrase used to express dismissal or the act of disregarding someone. Its origin is attributed to Sir Walter Scott in a work published in 1816, which is in fact a mistranslation of an expression from the Vulgate Bible. There ...

" because he was not recognized by the staff. When Benny arrived and asked for Ace, he was told that Ace became tired of waiting and left. Soon Ace began to receive mail from the Stork, which he proceeded to answer in his tongue in cheek style. Ace's response to the message about the club having wonderful air conditioning was that after having received the cold shoulder there, he was well aware of the climate. Bilingsley responded to Ace with a gift of some Stork Club bow ties. Ace then asked for some matching socks so he might be in style to be turned away again. Ace and his wife became regulars at the club after the issue was resolved.

Stork Club gifts

Owner Billingsley was well known for his extravagant gifts presented to his favorite patrons, spending an average of $100,000 a year on them. They included compacts studded with diamonds and rubies, French perfumes, Champagne and liquor, and even automobiles. Many of the gifts were specially made for the Stork Club, with the club's name and logo on them. Some of the best known examples were the gifts of ''Sortilège'' perfume by Le Galion, which became known as the "fragrance of the Stork Club". Billingsley convinced

Owner Billingsley was well known for his extravagant gifts presented to his favorite patrons, spending an average of $100,000 a year on them. They included compacts studded with diamonds and rubies, French perfumes, Champagne and liquor, and even automobiles. Many of the gifts were specially made for the Stork Club, with the club's name and logo on them. Some of the best known examples were the gifts of ''Sortilège'' perfume by Le Galion, which became known as the "fragrance of the Stork Club". Billingsley convinced Arthur Godfrey

Arthur Morton Godfrey (August 31, 1903 – March 16, 1983) was an American radio and television broadcaster and entertainer who was sometimes introduced by his nickname The Old Redhead. At the peak of his success, in the early-to-mid 1950s, Godf ...

, Morton Downey

Sean Morton Downey (November 14, 1901 – October 25, 1985), also known as Morton Downey Sr., was an American singer and entertainer popular in the United States in the first half of the 20th century, enjoying his greatest success in the late 1 ...

, and his own assistant, Steve Hannigan, to form an investment group with him to obtain the United States distributorship of the fragrance. The partners expanded into the sale of soap, cosmetics and other sundries under the Stork Club name. They called the business Cigogne—the French word for stork; the line was carried by various drug and department stores in the United States. Every female guest of the club received a small vial of perfume and a tube of Stork Club lipstick as souvenirs of her visit. It was also Billingsley's standard practice to send every regular club patron a case of Champagne at Christmas.

Sunday night was "Balloon Night". As is common with New Year's celebrations, balloons were held on the ceiling of the Main Dining Room by a net and the net would open at the stroke of midnight. As the balloons came down, the ladies would begin frantically trying to catch them. Each contained a number and a drawing would be held for the prizes, which ranged from charms for bracelets to automobiles; there were also at least three $100 bills folded and placed randomly in the balloons.

Billingsley's generosity was not confined to those who were always at the club. He received the following letter in 1955: "I am grateful to you for your thoughtful kindness in sending me such a generous selection of attractive neckties. At the same time may I once again thank you for the cigars that you regularly send to the White House." It was signed by

Sunday night was "Balloon Night". As is common with New Year's celebrations, balloons were held on the ceiling of the Main Dining Room by a net and the net would open at the stroke of midnight. As the balloons came down, the ladies would begin frantically trying to catch them. Each contained a number and a drawing would be held for the prizes, which ranged from charms for bracelets to automobiles; there were also at least three $100 bills folded and placed randomly in the balloons.

Billingsley's generosity was not confined to those who were always at the club. He received the following letter in 1955: "I am grateful to you for your thoughtful kindness in sending me such a generous selection of attractive neckties. At the same time may I once again thank you for the cigars that you regularly send to the White House." It was signed by Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

. During World War II, three bomber planes were christened with the name of the Stork Club. Billingsley commissioned Tiffany & Co. to produce sterling silver Stork Club logo Victory pins as gifts for their crew members. Patrons were not always on the receiving end; Billingsley's writings claimed that one of his waiters received a $20,000 tip. A bartender received a new Cadillac from a grateful patron, and a headwaiter received a $10,000 tip from tennis star Fred Perry

Frederick John Perry (18 May 1909 – 2 February 1995) was a British tennis and table tennis player and former world No. 1 from England who won 10 Majors including eight Grand Slam tournaments and two Pro Slams single titles, as well ...

. It was necessary for Billingsley to give the expensive gifts and to provide some or all of a celebrity's Stork Club services for free to bring the stars to the club and keep them coming back. The notables were what brought people from all over the country in all walks of life to visit the Stork Club.

In popular culture

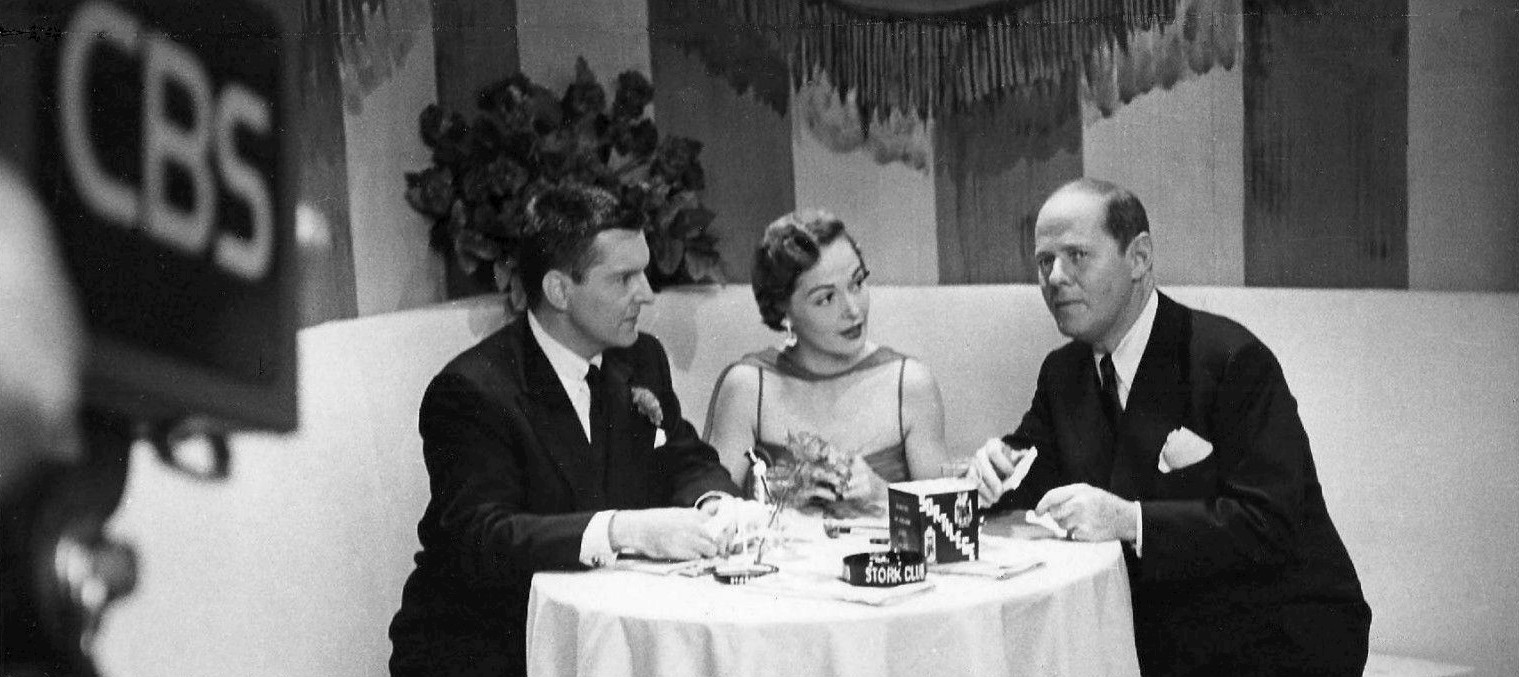

Billingley hosted thetelevision series

A television show – or simply TV show – is any content produced for viewing on a television set which can be broadcast via over-the-air, satellite, or cable, excluding breaking news, advertisements, or trailers that are typically placed be ...

''The Stork Club'', in which he circulated among the tables, interviewing guests at the club. Originally sponsored by Fatima cigarettes, the series ran from 1950 to 1955. The show was directed by Yul Brynner

Yuliy Borisovich Briner (russian: link=no, Юлий Борисович Бринер; July 11, 1920 – October 10, 1985), known professionally as Yul Brynner, was a Russian-born actor. He was best known for his portrayal of King Mongkut in th ...

, who was a television director before he became a well-known actor. The program began on CBS Television with the network having built a replica of the Cub Room on the Stork Club's sixth floor to serve as the set for the show. Billingsley was paid $12,000 each week as its host, but he was never really comfortable on camera and it was noticeable. The television show moved to ABC by 1955.

During the broadcast of May 8, 1955, Billingsley made some remarks about fellow New York restaurateur Bernard "Toots" Shor's financial solvency and honesty. Shor responded by suing for a million dollars. He collected just under $50,000 as a settlement in March 1959. ''The Stork Club'' television show ended in the same year the statements were made.

Philco Television Playhouse

''The Philco Television Playhouse'' is an American television anthology series that was broadcast live on NBC from 1948 to 1955. Produced by Fred Coe, the series was sponsored by Philco. It was one of the most respected dramatic shows of the Golde ...

'' presentation, "Murder at the Stork Club", was aired on NBC Television

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American English-language commercial broadcast television and radio network. The flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a division of Comcast, its headquarters are l ...

on January 15, 1950. Franchot Tone

Stanislaus Pascal Franchot Tone (February 27, 1905 – September 18, 1968) was an American actor, producer, and director of stage, film and television. He was a leading man in the 1930s and early 1940s, and at the height of his career was known ...

and Billingsley had cameo roles in the television drama. The television show was an adaptation of Vera Caspary

Vera Louise Caspary (November 13, 1899 – June 13, 1987) was an American writer of novels, plays, screenplays, and short stories. Her best-known novel, '' Laura'', was made into a successful movie. Though she claimed she was not a "real" myste ...

's 1946 mystery novel, ''The Murder in the Stork Club'', where the action took place in and around the famous nightclub, with Sherman Billingsley and other real-life characters appearing in the plot.

The Stork Club was also featured in several movies, including '' The Stork Club'' (1945), ''Executive Suite

An executive suite in its most general definition is a collection of offices or rooms—or suite—used by top managers of a business—or executives. Over the years, this general term has taken on a variety of specific meanings.

Corporate offi ...

'' (1954), ''Artists and Models

''Artists and Models'' is a 1955 American musical romantic comedy film in VistaVision directed by Frank Tashlin, marking Martin and Lewis's 14th feature together as a team. The film co-stars Shirley MacLaine and Dorothy Malone, with Eva Gabor ...

'' (1955), and ''My Favorite Year

''My Favorite Year'' is a 1982 American comedy film released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, directed by Richard Benjamin and written by Norman Steinberg and Dennis Palumbo from a story written by Palumbo. The film tells the story of a young comedy writ ...

'' (1982). Billingsley received $100,000 for the use of the club's name in the 1945 film. In ''All About Eve

''All About Eve'' is a 1950 American drama film written and directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, and produced by Darryl F. Zanuck. It is based on the 1946 short story "The Wisdom of Eve" by Mary Orr, although Orr does not receive a screen credit ...

'' (1950), the characters played by Bette Davis

Ruth Elizabeth "Bette" Davis (; April 5, 1908 – October 6, 1989) was an American actress with a career spanning more than 50 years and 100 acting credits. She was noted for playing unsympathetic, sardonic characters, and was famous for her pe ...

, Gary Merrill

Gary Fred Merrill (August 2, 1915 – March 5, 1990) was an American film and television actor whose credits included more than 50 feature films, a half-dozen mostly short-lived TV series, and dozens of television guest appearances. He starr ...

, Anne Baxter and George Sanders

George Henry Sanders (3 July 1906 – 25 April 1972) was a British actor and singer whose career spanned over 40 years. His heavy, upper-class English accent and smooth, bass voice often led him to be cast as sophisticated but villainous chara ...

are shown in the Cub Room of the Stork Club. The Alfred Hitchcock film ''The Wrong Man

''The Wrong Man'' is a 1956 American docudrama film noir directed by Alfred Hitchcock and starring Henry Fonda and Vera Miles. The film was drawn from the true story of an innocent man charged with a crime, as described in the book ''The True St ...

'' (1957) starred Henry Fonda

Henry Jaynes Fonda (May 16, 1905 – August 12, 1982) was an American actor. He had a career that spanned five decades on Broadway and in Hollywood. He cultivated an everyman screen image in several films considered to be classics.

Born and ra ...

as real-life Stork Club bassist Christopher Emanuel Balestrero ("Manny"), who was falsely accused of committing robberies around New York City. Scenes involving Balestrero playing the bass were actually shot at the club. The film's screenplay, written by Maxwell Anderson

James Maxwell Anderson (December 15, 1888 – February 28, 1959) was an American playwright, author, poet, journalist, and lyricist.

Background

Anderson was born on December 15, 1888, in Atlantic, Pennsylvania, the second of eight children to ...

, was based on a true story originally published in ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for Cell growth, growth, reaction to Stimu ...

''.

See also

*List of restaurants in New York City

This is a list of notable restaurants in New York City. A restaurant is a business which prepares and serves food and drink to customers in return for money, either paid before the meal, after the meal, or with an open account. New York City is th ...

References

Footnotes

Notes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* (a memoir by the maitre d' of the club during its final years). * Beebe, Lucius. ''The Stork Club Bar Book''. New York: Rinehart & Company, 1946. * Brooks, Johnny. "My Life Behind Bars". (Note: Brooks was a bartender of the Stork Club.) * ''The Stork Club Cookbook''. New York: The Stork Club, Inc., 1949 (later reprinted in paperback). * Caspary, Vera. ''The Murder in the Stork Club'' (novel). New York: Walter J. Black, 1946.External links

*Inside the Cub Room at the Stork Club

Alfred Eisenstaedt's 1944 Stork Club photos for LIFE magazine