Stephenson Grand Army of the Republic Memorial on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Stephenson Grand Army of the Republic Memorial, also known as ''Dr. Benjamin F. Stephenson'', is a public artwork in

Following Stephenson's death, the GAR grew from a charitable organization for Union widows and wounded veterans to the country's most powerful single-issue political group in the late 19th century. It was the nation's first veterans association open to both officers and enlisted men, and membership grew to over 400,000. The GAR was responsible for securing large pensions for veterans and members played an active role in the election of six Union veterans as U.S. president. In the early 20th century, GAR membership declined as veterans died of old age, and organization leaders began plans to memorialize them and the GAR itself. To honor the group's founder, the GAR, at the behest of General Charles Partridge and the ''

Following Stephenson's death, the GAR grew from a charitable organization for Union widows and wounded veterans to the country's most powerful single-issue political group in the late 19th century. It was the nation's first veterans association open to both officers and enlisted men, and membership grew to over 400,000. The GAR was responsible for securing large pensions for veterans and members played an active role in the election of six Union veterans as U.S. president. In the early 20th century, GAR membership declined as veterans died of old age, and organization leaders began plans to memorialize them and the GAR itself. To honor the group's founder, the GAR, at the behest of General Charles Partridge and the ''

Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

honoring Dr. Benjamin F. Stephenson, founder of the Grand Army of the Republic

The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army (United States Army), Union Navy (U.S. Navy), and the Marines who served in the American Civil War. It was founded in 1866 in Decatur, Il ...

, a fraternal organization for Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

veterans. The memorial is sited at Indiana Plaza, located at the intersection of 7th Street, Indiana Avenue, and Pennsylvania Avenue

Pennsylvania Avenue is a diagonal street in Washington, D.C., and Prince George's County, Maryland, that connects the White House and the United States Capitol and then crosses the city to Maryland. In Maryland it is also Maryland Route 4 (MD 4) ...

NW in the Penn Quarter

Penn Quarter is a neighborhood east of Downtown Washington, D.C. and north of Pennsylvania Avenue, NW. Penn Quarter is roughly equivalent to the city's early downtown core near Pennsylvania Avenue and 7th Street NW, The definition of Downtown ...

neighborhood. The bronze figures were sculpted by J. Massey Rhind

John Massey Rhind (9 July 1860 – 1 January 1936) was a Scottish-American sculptor. Among Rhind's better known works is the marble statue of Dr. Crawford W. Long located in the National Statuary Hall Collection in Washington D.C. (1926).

E ...

, a prominent 20th-century artist. Attendees at the 1909 dedication ceremony included President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

, Senator William Warner, and hundreds of Union veterans.

The memorial is one of eighteen Civil War monuments in Washington, D.C., which were collectively listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

in 1978. The bronze sculptures of Stephenson and allegorical figures are displayed on a triangular granite shaft surmounting a concrete base. The memorial is owned and maintained by the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

, a federal agency of the Interior Department

An interior ministry (sometimes called a ministry of internal affairs or ministry of home affairs) is a government department that is responsible for internal affairs.

Lists of current ministries of internal affairs

Named "ministry"

* Ministry ...

.

History

Background

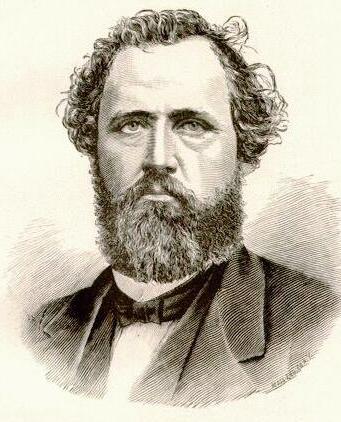

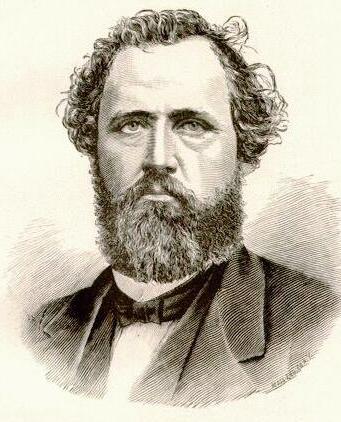

Benjamin F. Stephenson (1823–1871) was a graduate ofRush Medical College

Rush Medical College is the medical school of Rush University, located in the Illinois Medical District, about 3 km (2 miles) west of the Loop in Chicago. Offering a full-time Doctor of Medicine program, the school was chartered in 1837, and ...

who practiced medicine in Petersburg, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

. When the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

began in 1861, he was appointed surgeon of the 14th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Eventually, he achieved the rank of major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

. Following his honorable discharge in 1864, Stephenson began practicing medicine in Springfield

Springfield may refer to:

* Springfield (toponym), the place name in general

Places and locations Australia

* Springfield, New South Wales (Central Coast)

* Springfield, New South Wales (Snowy Monaro Regional Council)

* Springfield, Queenslan ...

, Illinois, and soon began plans for a national association of Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

veterans. He named the new organization the Grand Army of the Republic

The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army (United States Army), Union Navy (U.S. Navy), and the Marines who served in the American Civil War. It was founded in 1866 in Decatur, Il ...

(GAR), wrote the GAR's constitution and adopted the GAR motto "Fraternity, Charity, and Loyalty". The organization would be open to all Union soldiers and sailors who were honorably discharged. Stephenson found a lack of enthusiasm for the GAR among Springfield veterans, so he chose nearby Decatur to establish Post No. 1, Decatur, Department of Illinois, Grand Army of the Republic, on April 6, 1866. The date was the fourth anniversary of the Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh (also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing) was fought on April 6–7, 1862, in the American Civil War. The fighting took place in southwestern Tennessee, which was part of the war's Western Theater. The battlefield i ...

where he and most of the other charter members had taken part. After the GAR began to attract new members, Stephenson was relegated to adjutant general and spent most of his time attending to routine duties. At the time of his death in 1871, Stephenson's medical practice was failing, and he felt the GAR would never succeed.

Following Stephenson's death, the GAR grew from a charitable organization for Union widows and wounded veterans to the country's most powerful single-issue political group in the late 19th century. It was the nation's first veterans association open to both officers and enlisted men, and membership grew to over 400,000. The GAR was responsible for securing large pensions for veterans and members played an active role in the election of six Union veterans as U.S. president. In the early 20th century, GAR membership declined as veterans died of old age, and organization leaders began plans to memorialize them and the GAR itself. To honor the group's founder, the GAR, at the behest of General Charles Partridge and the ''

Following Stephenson's death, the GAR grew from a charitable organization for Union widows and wounded veterans to the country's most powerful single-issue political group in the late 19th century. It was the nation's first veterans association open to both officers and enlisted men, and membership grew to over 400,000. The GAR was responsible for securing large pensions for veterans and members played an active role in the election of six Union veterans as U.S. president. In the early 20th century, GAR membership declined as veterans died of old age, and organization leaders began plans to memorialize them and the GAR itself. To honor the group's founder, the GAR, at the behest of General Charles Partridge and the ''National Tribune

''National Tribune'' was an independent newspaper and publishing company owned by the National Tribune Company, formed in 1877 in Washington, D.C.

Overview

''The National Tribune'' (official title) was a post-Civil War newspaper based in Washin ...

'', raised $35,000 from its members to erect a memorial for Stephenson. Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

appropriated an additional $10,000 on March 4, 1907.

GAR leaders had specific plans for the memorial, which left little leeway for artist creativity. They wanted a tall, triangular granite shaft with three figures representing the organization's motto. J. Massey Rhind

John Massey Rhind (9 July 1860 – 1 January 1936) was a Scottish-American sculptor. Among Rhind's better known works is the marble statue of Dr. Crawford W. Long located in the National Statuary Hall Collection in Washington D.C. (1926).

E ...

(1860–1936), a Scottish-American sculptor who immigrated to the United States in 1889, was chosen for the project. At the time, he was considered one of the country's best architectural sculptors known for the large Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

*Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

*Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

**North Syracuse, New York

*Syracuse, Indiana

* Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, Miss ...

, New York. The architectural firm Rankin, Kellogg & Crane was chosen to design the central shaft of the memorial, and the reliefs were founded by Roman Bronze Works Roman Bronze Works, now operated as Roman Bronze Studios, is a bronze foundry in New York City. Established in 1897 by Riccardo Bertelli, it was the first American foundry to specialize in the lost-wax casting method, and was the country's pre-emin ...

. William Gray & Sons performed contracting duties for the memorial, and P. R. Pullman and Company was chosen as the contractor for the foundation.

A resolution passed by the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

in April 1902 provided the memorial to be erected on any of the city's public lands other than the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library is ...

and Capitol

A capitol, named after the Capitoline Hill in Rome, is usually a legislative building where a legislature meets and makes laws for its respective political entity.

Specific capitols include:

* United States Capitol in Washington, D.C.

* Numerous ...

grounds. The site chosen, at the corner of 7th Street and Louisiana Avenue (now Indiana Avenue) NW, was selected by a commission appointed by Congress. The commission consisted of Secretary of War Jacob M. Dickinson

Jacob McGavock Dickinson (January 30, 1851 – December 13, 1928) was United States Secretary of War under President William Howard Taft from 1909 to 1911. He was succeeded by Henry L. Stimson. He was an attorney, politician, and businessman ...

, Senator George P. Wetmore

George Peabody Wetmore (August 2, 1846September 11, 1921) was an American politician who was the 37th Governor of, and a Senator from, Rhode Island.

Early life

George Peabody Wetmore was born in London, England, during a visit of his parents ...

, Representative Samuel W. McCall

Samuel Walker McCall (February 28, 1851 – November 4, 1923) was a Republican lawyer, politician, and writer from Massachusetts. He was for twenty years (1893–1913) a member of the United States House of Representatives, and the 47th Governo ...

, General Louis Wagner, and Thomas S. Hopkins. The soil at the chosen site, present-day Indiana Plaza, could not support the memorial's weight, so the concrete foundation had to be expanded.

Dedication

The Stephenson memorial was formally dedicated at 2:30 pm on July 3, 1909. Hundreds of elderly veterans attended the event, many wearing their military uniforms. Prominent attendees included PresidentWilliam Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

and Senator William Warner. Following the invocation, GAR commander-in-chief Colonel Henry M. Nevius gave an impassioned speech about the sacrifices made by Union forces during the Civil War. He said by the shedding of their blood, "the flag of the United States has been raised from the dust and mire, smoke begrimed, powder stained and bullet ridden and thrown to the breeze to float forever over our broad land of the free."

Taft paid tribute to the sacrifices made by veterans and accepted the memorial on behalf of the American people. Following his speech, Warner told the crowd: "Boys, the President of the United States talks like a comrade. Get up on your feet, all of you, now three cheers for the President of the United States." The president and Rhind, who was introduced to the crowd, were both cheered. After the ceremony, the Marine Band

Marine is an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the sea or ocean.

Marine or marines may refer to:

Ocean

* Maritime (disambiguation)

* Marine art

* Marine biology

* Marine debris

* Marine habitats

* Marine life

* Marine pollution

Military

* ...

played "Tenting on the Old Camp Ground

"Tenting on the Old Camp Ground" (also known as Tenting Tonight) was a popular song during the American Civil War. A particular favorite of enlisted men in the Union army, it was written in 1863 by Walter Kittredge and first performed in that yea ...

" as the veterans sang. Brigadier General William Wallace Wotherspoon

William Wallace Wotherspoon (November 16, 1850 – October 21, 1921) was a United States Army general who served as Chief of Staff of the United States Army in 1914.

Early life

Wotherspoon was born in Washington, D.C., on November 16, 1850, th ...

served as the grand marshal of a military parade that marched from City Hall

In local government, a city hall, town hall, civic centre (in the UK or Australia), guildhall, or a municipal building (in the Philippines), is the chief administrative building of a city, town, or other municipality. It usually houses ...

, past the memorial, west on Pennsylvania Avenue

Pennsylvania Avenue is a diagonal street in Washington, D.C., and Prince George's County, Maryland, that connects the White House and the United States Capitol and then crosses the city to Maryland. In Maryland it is also Maryland Route 4 (MD 4) ...

to the Treasury Building

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be state or royal property, church treasure or in ...

, and ended at 15th Street and New York Avenue.

Later history

In 1987, the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation created Indiana Plaza by closing a portion of C Street, decreasing the width of Indiana Avenue, and adding landscaping. The process required relocating the memorial and nearbyTemperance Fountain

A temperance fountain was a fountain that was set up, usually by a private benefactor, to encourage temperance, and to make abstinence from beer possible by the provision of clean, safe, and free water. Beer was the main alternative to water, an ...

. The Stephenson memorial is now visible at the terminus of C Street. The fountain now stands where the Stephens memorial was previously located.

The memorial is one of eighteen Civil War monuments in Washington, D.C., which were collectively listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

on September 20, 1978, and the District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites

The District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites is a register of historic places in Washington, D.C. that are designated by the District of Columbia Historic Preservation Review Board (HPRB), a component of the District of Columbia Govern ...

on March 3, 1979. It is also designated a contributing property

In the law regulating historic districts in the United States, a contributing property or contributing resource is any building, object, or structure which adds to the historical integrity or architectural qualities that make the historic distri ...

to the Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site

Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site is a National Historic Site in the city of Washington, D.C. Established on September 30, 1965, the site is roughly bounded by Constitution Avenue, 15th Street NW, F Street NW, and 3rd Street NW. The hi ...

, established on September 30, 1965. The memorial and surrounding plaza are owned and maintained by the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

, a federal agency of the Interior Department

An interior ministry (sometimes called a ministry of internal affairs or ministry of home affairs) is a government department that is responsible for internal affairs.

Lists of current ministries of internal affairs

Named "ministry"

* Ministry ...

.

Design and location

The memorial is located at Indiana Plaza (Reservation 36A) in thePenn Quarter

Penn Quarter is a neighborhood east of Downtown Washington, D.C. and north of Pennsylvania Avenue, NW. Penn Quarter is roughly equivalent to the city's early downtown core near Pennsylvania Avenue and 7th Street NW, The definition of Downtown ...

neighborhood. The small public plaza, located across the street from the Archives

An archive is an accumulation of historical records or materials – in any medium – or the physical facility in which they are located.

Archives contain primary source documents that have accumulated over the course of an individual or ...

Metro

Metro, short for metropolitan, may refer to:

Geography

* Metro (city), a city in Indonesia

* A metropolitan area, the populated region including and surrounding an urban center

Public transport

* Rapid transit, a passenger railway in an urba ...

station, is bounded by 7th Street to the west, Indiana Avenue to the north, and Pennsylvania Avenue

Pennsylvania Avenue is a diagonal street in Washington, D.C., and Prince George's County, Maryland, that connects the White House and the United States Capitol and then crosses the city to Maryland. In Maryland it is also Maryland Route 4 (MD 4) ...

to the south. Two historic buildings bound the east side of the plaza: Central National Bank and National Bank of Washington, Washington Branch

The Washington Branch of the National Bank of Washington is an historic bank building located in Northwest, Washington, D.C.

History

The building was built in 1888 as a branch of The Bank of Washington. It was designed by James G. Hill and Dani ...

. Sited directly to the north of the memorial is the historic Temperance Fountain. The memorial is sited within a circular plaza and surrounded by magnolia

''Magnolia'' is a large genus of about 210 to 340The number of species in the genus ''Magnolia'' depends on the taxonomic view that one takes up. Recent molecular and morphological research shows that former genera ''Talauma'', ''Dugandiodendro ...

trees and ivy. Decorative lampposts are located at the three entrances.

The triangular shaft, consisting of granite blocks, is tall and surmounts a concrete base. On each side of the shaft is a bronze relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term ''relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that the ...

. On the front (west) side is a relief of a Union soldier and Union sailor symbolizing Fraternity. The soldier is holding a gun with his right hand, and to his left, the sailor holds the American flag

The national flag of the United States of America, often referred to as the ''American flag'' or the ''U.S. flag'', consists of thirteen equal horizontal stripes of red (top and bottom) alternating with white, with a blue rectangle in the c ...

with his right hand. The word FRATERNITY is located on the bottom of the relief. Below the Fraternity relief is a relief bust

Bust commonly refers to:

* A woman's breasts

* Bust (sculpture), of head and shoulders

* An arrest

Bust may also refer to:

Places

*Bust, Bas-Rhin, a city in France

*Lashkargah, Afghanistan, known as Bust historically

Media

* ''Bust'' (magazine ...

of Stephenson dressed in military uniform. The bust is displayed on a bronze medallion installed in a circular niche decorated with foliage. Below the Stephenson relief is an inscription flanked by Grand Army of the Republic emblems. On the northeast side of the memorial, the relief depicts a woman cloaked in a long robe and cape protecting a small child standing to her left. She is touching the child's shoulder with her left hand, and the word CHARITY is on the bottom of the relief. A woman holding a shield and drawn sword is on the southeast side of the memorial. The word LOYALTY is located on the bottom of the relief.

Inscriptions on the memorial include the following:

* 1861 1865 (upper portion of shaft, above the Union soldier and sailor relief)

* FRATERNITY (on relief, below the soldier and sailor)

* GRAND ARMY OF THE REPUBLIC / ORGANIZED AT DECATUR ILLINOIS, APRIL 6, 1866 / BY BENJAMIN FRANKLIN STEPHENSON M.D. (lower portion of the shaft, below the Stephenson relief)

* CHARITY (on relief, below the Charity figure)

* THE GREATEST / OF THESE IS / CHARITY (lower portion of the shaft, below the Charity relief)

* LOYALTY (on relief, below the Loyalty figure)

* WHO KNEW NO / GLORY BUT HIS / COUNTRY'S GOOD (lower portion of the shaft, below the Loyalty relief)

See also

*List of public art in Washington, D.C., Ward 6

This is a list of public art in List of neighborhoods of the District of Columbia by ward, Ward 6 of Washington, D.C.

This list applies only to works of public art accessible in an outdoor public space. For example, this does not include artwor ...

* Outdoor sculpture in Washington, D.C.

There are many outdoor sculptures in Washington, D.C. In addition to the capital's most famous monuments and memorials, many figures recognized as national heroes (either in government or military) have been posthumously awarded with his or her own ...

References

External links

* {{Good article 1907 sculptures Allegorical sculptures in the United States Bronze sculptures in Washington, D.C. Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C. Concrete sculptures in the United StatesWashington DC

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

Granite sculptures in Washington, D.C.

Historic district contributing properties in Washington, D.C.

Sculptures of men in Washington, D.C.

Sculptures of women in Washington, D.C.

Outdoor sculptures in Washington, D.C.

Penn Quarter

Sculptures by J. Massey Rhind