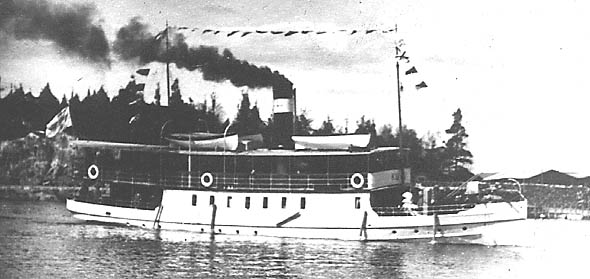

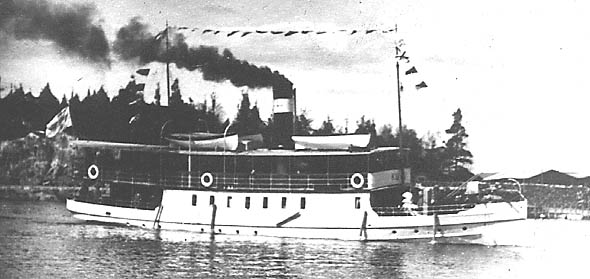

Steam ship on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and

The American ship first crossed the Atlantic Ocean arriving in Liverpool, England, on June 20, 1819, although most of the voyage was actually made under sail. The first ship to make the transatlantic trip substantially under steam power may have been the British-built Dutch-owned ''Curaçao'', a wooden 438-ton vessel built in

The American ship first crossed the Atlantic Ocean arriving in Liverpool, England, on June 20, 1819, although most of the voyage was actually made under sail. The first ship to make the transatlantic trip substantially under steam power may have been the British-built Dutch-owned ''Curaçao'', a wooden 438-ton vessel built in

Brunel was given a chance to inspect

Brunel was given a chance to inspect

The efficiency of Holt's package of boiler pressure, compound engine and hull design gave a ship that could steam at 10 knots on 20 long tons of coal a day. This fuel consumption was a saving from between 23 and 14 long tons a day, compared to other contemporary steamers. Not only did less coal need to be carried to travel a given distance, but fewer firemen were needed to fuel the boilers, so crew costs and their accommodation space were reduced. ''Agamemnon'' was able to sail from London to China with a coaling stop at

The efficiency of Holt's package of boiler pressure, compound engine and hull design gave a ship that could steam at 10 knots on 20 long tons of coal a day. This fuel consumption was a saving from between 23 and 14 long tons a day, compared to other contemporary steamers. Not only did less coal need to be carried to travel a given distance, but fewer firemen were needed to fuel the boilers, so crew costs and their accommodation space were reduced. ''Agamemnon'' was able to sail from London to China with a coaling stop at

There were a few further experiments until went into service on the route from Britain to Australia. Her triple expansion engine was designed by Dr A C Kirk, the engineer who had developed the machinery for ''Propontis''. The difference was the use of two double ended Scotch type steel boilers, running at . These boilers had patent corrugated furnaces that overcame the competing problems of heat transfer and sufficient strength to deal with the boiler pressure. ''Aberdeen'' was a marked success, achieving in trials, at 1,800 indicated horsepower, a fuel consumption of of coal per indicated horsepower. This was a reduction in fuel consumption of about 60%, compared to a typical steamer built ten years earlier. In service, this translated into less than 40 tons of coal a day when travelling at . Her maiden outward voyage to

There were a few further experiments until went into service on the route from Britain to Australia. Her triple expansion engine was designed by Dr A C Kirk, the engineer who had developed the machinery for ''Propontis''. The difference was the use of two double ended Scotch type steel boilers, running at . These boilers had patent corrugated furnaces that overcame the competing problems of heat transfer and sufficient strength to deal with the boiler pressure. ''Aberdeen'' was a marked success, achieving in trials, at 1,800 indicated horsepower, a fuel consumption of of coal per indicated horsepower. This was a reduction in fuel consumption of about 60%, compared to a typical steamer built ten years earlier. In service, this translated into less than 40 tons of coal a day when travelling at . Her maiden outward voyage to

By 1870 a number of inventions such as the

By 1870 a number of inventions such as the  Launched in 1938, was the largest passenger steamship ever built. Launched in 1969, ''

Launched in 1938, was the largest passenger steamship ever built. Launched in 1969, ''

Most steamships today are powered by

Most steamships today are powered by

E'Book

*Bennett, Frank M. (1897). ''The steam navy of the United States''. Warren & Company Publishers Philadelphia. p. 502.

E'BookUrl2

* Bradford, James C. (1986). ''Captains of the Old Steam Navy: Makers of the American Tradition, 1840–1880''. Naval Institute Press, p. 356,

Url

*Canney, Donald L. (1998). ''Lincoln's Navy: The Ships, Men and Organization, 1861–65''. Naval Institute Press. p. 232

Url

*

Url

*

E'Book

* Lambert, Andrew (1984). ''Battleships in Transition, the Creation of the Steam Battlefleet 1815–1860''. Conway Maritime Press. *

E'Book

E'Book

E'Book

*

E'Book

Url

Book

Transportation Photographs Collection

- University of Washington Library Steamships Steam engines Steam engine technology

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy

Seakeeping ability or seaworthiness is a measure of how well-suited a watercraft is to conditions when underway. A ship or boat which has good seakeeping ability is said to be very seaworthy and is able to operate effectively even in high sea stat ...

, that is propelled by one or more steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be ...

s that typically move (turn) propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

s or paddlewheels. The first steamships came into practical usage during the early 1800s; however, there were exceptions that came before. Steamships usually use the prefix

A prefix is an affix which is placed before the stem of a word. Adding it to the beginning of one word changes it into another word. For example, when the prefix ''un-'' is added to the word ''happy'', it creates the word ''unhappy''. Particu ...

designations of "PS" for ''paddle steamer'' or "SS" for ''screw steamer'' (using a propeller or screw). As paddle steamers became less common, "SS" is assumed by many to stand for "steamship". Ships powered by internal combustion engines use a prefix such as "MV" for ''motor vessel'', so it is not correct to use "SS" for most modern vessels.

As steamships were less dependent on wind patterns, new trade routes opened up. The steamship has been described as a "major driver of the first wave of trade globalization

Globalization, or globalisation (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English; American and British English spelling differences#-ise, -ize (-isation, -ization), see spelling differences), is the process of foreign relation ...

(1870–1913)" and contributor to "an increase in international trade that was unprecedented in human history".

History

Steamships were preceded by smaller vessels, called steamboats, conceived in the first half of the 18th century, with the first working steamboat andpaddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine that drives paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses wer ...

, the '' Pyroscaphe'', from 1783. Once the technology of steam was mastered at this level, steam engines were mounted on larger, and eventually, ocean-going vessels. Becoming reliable, and propelled by screw rather than paddlewheels, the technology changed the design of ships for faster, more economic propulsion.

Paddle

A paddle is a handheld tool with an elongated handle and a flat, widened distal end (i.e. the ''blade''), used as a lever to apply force onto the bladed end. It most commonly describes a completely handheld tool used to propel a human-powered ...

wheels as the main motive source became standard on these early vessels. It was an effective means of propulsion under ideal conditions but otherwise had serious drawbacks. The paddle-wheel performed best when it operated at a certain depth, however when the depth of the ship changed from added weight it further submerged the paddle wheel causing a substantial decrease in performance.

Within a few decades of the development of the river and canal steamboat, the first steamships began to cross the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the "Old World" of Afr ...

. The first sea-going steamboat was Richard Wright's first steamboat ''Experiment'', an ex-French lugger

A lugger is a sailing vessel defined by its rig, using the lug sail on all of its one or several masts. They were widely used as working craft, particularly off the coasts of France, England, Ireland and Scotland. Luggers varied extensively ...

; she steamed from Leeds

Leeds () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the thi ...

to Yarmouth in July 1813.

The first iron steamship to go to sea was the 116-ton '' Aaron Manby'', built in 1821 by Aaron Manby at the Horseley Ironworks

The Horseley Ironworks (sometimes spelled Horsley) was a major ironworks in the Tipton area in the county of Staffordshire, now the West Midlands, England.

History

Founded by Aaron Manby, it is most famous for constructing the first iron ...

, and became the first iron-built vessel to put to sea when she crossed the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or (Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kan ...

in 1822, arriving in Paris on 22 June. She carried passengers and freight to Paris in 1822 at an average speed of 8 knots (9 mph, 14 km/h).

The American ship first crossed the Atlantic Ocean arriving in Liverpool, England, on June 20, 1819, although most of the voyage was actually made under sail. The first ship to make the transatlantic trip substantially under steam power may have been the British-built Dutch-owned ''Curaçao'', a wooden 438-ton vessel built in

The American ship first crossed the Atlantic Ocean arriving in Liverpool, England, on June 20, 1819, although most of the voyage was actually made under sail. The first ship to make the transatlantic trip substantially under steam power may have been the British-built Dutch-owned ''Curaçao'', a wooden 438-ton vessel built in Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

and powered by two 50 hp engines, which crossed from Hellevoetsluis

Hellevoetsluis () is a small city and municipality in the western Netherlands. It is located in Voorne-Putten, South Holland. The municipality covers an area of of which is water and it includes the population centres Nieuw-Helvoet, Nieuwenh ...

, near Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Rotte'') is the second largest city and municipality in the Netherlands. It is in the province of South Holland, part of the North Sea mouth of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta, via the ''"N ...

on 26 April 1827 to Paramaribo

Paramaribo (; ; nicknamed Par'bo) is the capital and largest city of Suriname, located on the banks of the Suriname River in the Paramaribo District. Paramaribo has a population of roughly 241,000 people (2012 census), almost half of Suriname's ...

, Surinam Surinam may refer to:

* Surinam (Dutch colony) (1667–1954), Dutch plantation colony in Guiana, South America

* Surinam (English colony) (1650–1667), English short-lived colony in South America

* Surinam, alternative spelling for Suriname

...

on 24 May, spending 11 days under steam on the way out and more on the return. Another claimant is the Canadian ship in 1833.

The first steamship purpose-built for regularly scheduled trans-Atlantic crossings was the British side-wheel paddle steamer built by Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "one ...

in 1838, which inaugurated the era of the trans-Atlantic ocean liner

An ocean liner is a passenger ship primarily used as a form of transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships).

C ...

.

The , built in Britain in 1839 by Francis Pettit Smith, was the world's first screw propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

-driven steamship for open water seagoing. She had considerable influence on ship development, encouraging the adoption of screw propulsion by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by Kingdom of England, English and Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were foug ...

, in addition to her influence on commercial vessels. The first screw-driven propeller steamship introduced in America was on a ship built by Thomas Clyde in 1844 and many more ships and routes followed.

Screw-propeller steamers

The key innovation that made ocean-going steamers viable was the change from the paddle-wheel to thescrew-propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust up ...

as the mechanism of propulsion. These steamships quickly became more popular, because the propeller's efficiency was consistent regardless of the depth at which it operated. Being smaller in size and mass and being completely submerged, it was also far less prone to damage.

James Watt of Scotland is widely given credit for applying the first screw propeller to an engine at his Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

works, an early steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be ...

, beginning the use of a hydrodynamic

In physics and engineering, fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that describes the flow of fluids—liquids and gases. It has several subdisciplines, including ''aerodynamics'' (the study of air and other gases in motion) and ...

screw for propulsion.

The development of screw propulsion relied on the following technological innovations.

Steam engines had to be designed with the power delivered at the bottom of the machinery, to give direct drive to the propeller shaft

A drive shaft, driveshaft, driving shaft, tailshaft (Australian English), propeller shaft (prop shaft), or Cardan shaft (after Girolamo Cardano) is a component for transmitting mechanical power and torque and rotation, usually used to connect ...

. A paddle steamer's engines drive a shaft that is positioned above the waterline, with the cylinders positioned below the shaft. SS'' Great Britain'' used chain drive to transmit power from a paddler's engine to the propeller shaft - the result of a late design change to propeller propulsion.

An effective stern tube

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. Orig ...

and associated bearings were required. The stern tube contains the propeller shaft where it passes through the hull structure. It should provide an unrestricted delivery of power by the propeller shaft. The combination of hull and stern tube must avoid any flexing that will bend the shaft or cause uneven wear. The inboard end has a stuffing box that prevents water from entering the hull along the tube. Some early stern tubes were made of brass and operated as a water lubricated bearing along the entire length. In other instances a long bush of soft metal was fitted in the after end of the stern tube. ''Great Eastern'' had this arrangement fail on her first transatlantic voyage, with very large amounts of uneven wear. The problem was solved with a lignum vitae

Lignum vitae () is a wood, also called guayacan or guaiacum, and in parts of Europe known as Pockholz or pokhout, from trees of the genus '' Guaiacum''. The trees are indigenous to the Caribbean and the northern coast of South America (e.g: Co ...

water-lubricated bearing, patented in 1858. This became standard practice and is in use today.

Since the motive power of screw propulsion is delivered along the shaft, a thrust bearing

A thrust bearing is a particular type of rotary bearing. Like other bearings they permanently rotate between parts, but they are designed to support a predominantly axial load.

Thrust bearings come in several varieties.

*''Thrust ball bearings ...

is needed to transfer that load to the hull without excessive friction. SS'' Great Britain'' had a 2 ft diameter gunmetal plate on the forward end of the shaft which bore against a steel plate attached to the engine beds. Water at 200 psi was injected between these two surfaces to lubricate and separate them. This arrangement was not sufficient for higher engine powers and oil lubricated "collar" thrust bearings became standard from the early 1850s. This was superseded at the beginning of the 20th century by floating pad bearing which automatically built up wedges of oil which could withstand bearing pressures of 500 psi or more.

Name prefix

Steam-powered ships were named with a prefix designating their propeller configuration i.e. single, twin, triple-screw. Single-screw Steamship SS, Twin-Screw Steamship TSS, Triple-Screw Steamship TrSS. Steam turbine-driven ships had the prefix TS. In the UK the prefix RMS for Royal Mail Steamship overruled the screw configuration prefix.First ocean-going steamships

The first steamship credited with crossing the Atlantic Ocean between North America and Europe was the American ship , though she was actually a hybrid between a steamship and a sailing ship, with the first half of the journey making use of the steam engine. ''Savannah'' left the port ofSavannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the British colonial capital of the Province of Georgia and later t ...

, US, on 22 May 1819, arriving in Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

, England, on 20 June 1819; her steam engine having been in use for part of the time on 18 days (estimates vary from 8 to 80 hours). A claimant to the title of the first ship to make the transatlantic trip substantially under steam power is the British-built Dutch-owned ''Curaçao'', a wooden 438-ton vessel built in Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

and powered by two 50 hp engines, which crossed from Hellevoetsluis

Hellevoetsluis () is a small city and municipality in the western Netherlands. It is located in Voorne-Putten, South Holland. The municipality covers an area of of which is water and it includes the population centres Nieuw-Helvoet, Nieuwenh ...

, near Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Rotte'') is the second largest city and municipality in the Netherlands. It is in the province of South Holland, part of the North Sea mouth of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta, via the ''"N ...

on 26 April 1827 to Paramaribo

Paramaribo (; ; nicknamed Par'bo) is the capital and largest city of Suriname, located on the banks of the Suriname River in the Paramaribo District. Paramaribo has a population of roughly 241,000 people (2012 census), almost half of Suriname's ...

, Surinam Surinam may refer to:

* Surinam (Dutch colony) (1667–1954), Dutch plantation colony in Guiana, South America

* Surinam (English colony) (1650–1667), English short-lived colony in South America

* Surinam, alternative spelling for Suriname

...

on 24 May, spending 11 days under steam on the way out and more on the return. Another claimant is the Canadian ship in 1833.

The British side-wheel paddle steamer was the first steamship purpose-built for regularly scheduled trans-Atlantic crossings, starting in 1838. In 1836 Isambard Kingdom Brunel and a group of Bristol investors formed the Great Western Steamship Company to build a line of steamships for the Bristol-New York route. The idea of regular scheduled transatlantic service was under discussion by several groups and the rival British and American Steam Navigation Company was established at the same time. ''Great Western's'' design sparked controversy from critics that contended that she was too big. The principle that Brunel understood was that the carrying capacity of a hull increases as the cube of its dimensions, while water resistance only increases as the square of its dimensions. This meant that large ships were more fuel efficient, something very important for long voyages across the Atlantic.

''Great Western'' was an iron-strapped, wooden, side-wheel paddle steamer, with four masts to hoist the auxiliary sails. The sails were not just to provide auxiliary propulsion, but also were used in rough seas to keep the ship on an even keel and ensure that both paddle wheels remained in the water, driving the ship in a straight line. The hull was built of oak by traditional methods. She was the largest steamship for one year, until the British and American's ''British Queen'' went into service. Built at the shipyard of Patterson & Mercer in Bristol, ''Great Western'' was launched on 19 July 1837 and then sailed to London, where she was fitted with two side-lever steam engines from the firm of Maudslay, Sons & Field

Maudslay, Sons and Field was an engineering company based in Lambeth, London.

History

The company was founded by Henry Maudslay as Henry Maudslay and Company in 1798 and was later reorganised into Maudslay, Sons and Field in 1833 after his sons ...

, producing 750 indicated horsepower between them. The ship proved satisfactory in service and initiated the transatlantic route, acting as a model for all following Atlantic paddle-steamers.

The Cunard Line

Cunard () is a British shipping and cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its three ships have been registered in Hamilton, Ber ...

's began her first regular passenger and cargo service by a steamship in 1840, sailing from Liverpool to Boston.

In 1845 the revolutionary , also built by Brunel, became the first iron-hulled screw-driven ship to cross the Atlantic. The SS ''Great Britain'' was the first ship to combine these two innovations. After the initial success of its first liner, SS ''Great Western'' of 1838, the Great Western Steamship Company assembled the same engineering team that had collaborated so successfully before. This time however, Brunel, whose reputation was at its height, came to assert overall control over design of the ship—a state of affairs that would have far-reaching consequences for the company. Construction was carried out in a specially adapted dry dock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

in Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city i ...

, England.

Brunel was given a chance to inspect

Brunel was given a chance to inspect John Laird John Laird may refer to:

* John Laird (American politician) (born 1950), California State Senator

* John Laird (footballer) (1935–2016) Australian rules footballer

* John Laird (philosopher) (1887–1946), Scottish philosopher

* John Laird (ship ...

's (English) channel packet ship

Packet boats were medium-sized boats designed for domestic mail, passenger, and freight transportation in European countries and in North American rivers and canals, some of them steam driven. They were used extensively during the 18th and 19th ...

''Rainbow''—the largest iron-hulled

Husk (or hull) in botany is the outer shell or coating of a seed. In the United States, the term husk often refers to the leafy outer covering of an ear of maize (corn) as it grows on the plant. Literally, a husk or hull includes the protective ...

ship then in service— in 1838, and was soon converted to iron-hulled technology. He scrapped his plans to build a wooden ship and persuaded the company directors to build an iron-hulled ship. Iron's advantages included being much cheaper than wood, not being subject to dry rot

Dry rot is wood decay caused by one of several species of fungi that digest parts of the wood which give the wood strength and stiffness. It was previously used to describe any decay of cured wood in ships and buildings by a fungus which resu ...

or woodworm

A woodworm is the wood-eating larva of many species of beetle. It is also a generic description given to the infestation of a wooden item (normally part of a dwelling or the furniture in it) by these larvae.

Types of woodworm

Woodboring beetle ...

, and its much greater structural strength. The practical limit on the length of a wooden-hulled ship is about 300 feet, after which hogging—the flexing of the hull as waves pass beneath it—becomes too great. Iron hulls are far less subject to hogging, so that the potential size of an iron-hulled ship is much greater.

In the spring of 1840 Brunel also had the opportunity to inspect the , the first screw-propelled steamship, completed only a few months before by F. P. Smith's Propeller Steamship Company. Brunel had been looking into methods of improving the performance of ''Great Britain''s paddlewheels, and took an immediate interest in the new technology, and Smith, sensing a prestigious new customer for his own company, agreed to lend ''Archimedes'' to Brunel for extended tests. Over several months, Smith and Brunel tested a number of different propellers on ''Archimedes'' in order to find the most efficient design, a four-bladed model submitted by Smith. When launched in 1843, ''Great Britain'' was by far the largest vessel afloat.

Brunel's last major project, the , was built in 1854–57 with the intent of linking Great Britain with India, via the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

, without any coaling stops. This ship was arguably more revolutionary than her predecessors. She was one of the first ships to be built with a double hull with watertight compartments and was the first liner to have four funnels. She was the biggest liner throughout the rest of the 19th century with a gross tonnage of almost 20,000 tons and had a passenger-carrying capacity of thousands. The ship was ahead of her time and went through a turbulent history, never being put to her intended use. The first transatlantic steamer built of steel was , built by Allan Line Royal Mail Steamers

The Allan Shipping Line was started in 1819, by Captain Alexander Allan of Saltcoats, Ayrshire, trading and transporting between Scotland and Montreal, a route which quickly became synonymous with the Allan Line. By the 1830s the company had offi ...

and entering service in 1879.

The first regular steamship service from the East Coast to the West Coast of the United States

The West Coast of the United States, also known as the Pacific Coast, Pacific states, and the western seaboard, is the coastline along which the Western United States meets the North Pacific Ocean. The term typically refers to the contiguous ...

began on 28 February 1849, with the arrival of the in San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, California, San Jose, and Oakland, Ca ...

. The ''California'' left New York Harbor on 6 October 1848, rounded Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

at the tip of South America, and arrived at San Francisco, California, after a four-month and 21-day journey. The first steamship to operate on the Pacific Ocean was the paddle steamer ''Beaver'', launched in 1836 to service Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trade, fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake b ...

trading posts between Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ) is a sound of the Pacific Northwest, an inlet of the Pacific Ocean, and part of the Salish Sea. It is located along the northwestern coast of the U.S. state of Washington. It is a complex estuarine system of interconnected m ...

Washington and Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S ...

.

Long-distance commercial steamships

The most testing route for steam was from Britain or the East Coast of the U.S. to theFar East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The te ...

. The distance from either is roughly the same, between , traveling down the Atlantic, around the southern tip of Africa, and across the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

. Before 1866, no steamship could carry enough coal to make this voyage and have enough space left to carry a commercial cargo.

A partial solution to this problem was adopted by the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company

P&O (in full, The Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company) is a British shipping and logistics company dating from the early 19th century. Formerly a public company, it was sold to DP World in March 2006 for £3.9 billion. DP World c ...

(P&O), using an overland section between Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

and Suez

Suez ( ar, السويس '; ) is a seaport city (population of about 750,000 ) in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same b ...

, with connecting steamship routes along the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on th ...

and then through the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

. While this worked for passengers and some high value cargo, sail was still the only solution for virtually all trade between China and Western Europe or East Coast America. Most notable of these cargoes was tea, typically carried in clipper

A clipper was a type of mid-19th-century merchant sailing vessel, designed for speed. Clippers were generally narrow for their length, small by later 19th century standards, could carry limited bulk freight, and had a large total sail area. "Cl ...

s.

Another partial solution was the Steam Auxiliary Ship - a vessel with a steam engine, but also rigged as a sailing vessel. The steam engine would only be used when conditions were unsuitable for sailing - in light or contrary winds. Some of this type (for instance ''Erl King'') were built with propellers that could be lifted clear of the water to reduce drag when under sail power alone. These ships struggled to be successful on the route to China, as the standing rigging required when sailing was a handicap when steaming into a head wind, most notably against the southwest monsoon when returning with a cargo of new tea. Though the auxiliary steamers persisted in competing in far eastern trade for a few years (and it was ''Erl King'' that carried the first cargo of tea through the Suez Canal), they soon moved on to other routes.

What was needed was a big improvement in fuel efficiency. While the boilers for steam engines on land were allowed to run at high pressures, the Board of Trade

The Board of Trade is a British government body concerned with commerce and industry, currently within the Department for International Trade. Its full title is The Lords of the Committee of the Privy Council appointed for the consideration of ...

(under the authority of the Merchant Shipping Act 1854

The Merchant Shipping Act 1854 (17 & 18 Vict c. 104) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It was passed on 10 August 1854, together with the Merchant Shipping Repeal Act 1854 (17 & 18 Vict c. 120), which together repealed several ...

) would not allow ships to exceed . Compound engines were a known source of improved efficiency – but generally not used at sea due to the low pressures available. ''Carnatic'' (1863), a P&O ship, had a compound engine - and achieved better efficiency than other ships of the time. Her boilers ran at but relied on a substantial amount of superheat.

Alfred Holt, who had entered marine engineering and ship management after an apprenticeship in railway engineering, experimented with boiler pressures of in ''Cleator''. Holt was able to persuade the Board of Trade to allow these boiler pressures and, in partnership with his brother Phillip launched ''Agamemnon'' in 1865. Holt had designed a particularly compact compound engine and taken great care with the hull design, producing a light, strong, easily driven hull.  The efficiency of Holt's package of boiler pressure, compound engine and hull design gave a ship that could steam at 10 knots on 20 long tons of coal a day. This fuel consumption was a saving from between 23 and 14 long tons a day, compared to other contemporary steamers. Not only did less coal need to be carried to travel a given distance, but fewer firemen were needed to fuel the boilers, so crew costs and their accommodation space were reduced. ''Agamemnon'' was able to sail from London to China with a coaling stop at

The efficiency of Holt's package of boiler pressure, compound engine and hull design gave a ship that could steam at 10 knots on 20 long tons of coal a day. This fuel consumption was a saving from between 23 and 14 long tons a day, compared to other contemporary steamers. Not only did less coal need to be carried to travel a given distance, but fewer firemen were needed to fuel the boilers, so crew costs and their accommodation space were reduced. ''Agamemnon'' was able to sail from London to China with a coaling stop at Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label=Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It incl ...

on the outward and return journey, with a time on passage substantially less than the competing sailing vessels. Holt had already ordered two sister ships to ''Agamemnon'' by the time she had returned from her first trip to China in 1866, operating these ships in the newly formed Blue Funnel Line

Alfred Holt and Company, trading as Blue Funnel Line, was a UK shipping company that was founded in 1866 and operated merchant ships for 122 years. It was one of the UK's larger shipowning and operating companies, and as such had a significan ...

. His competitors rapidly copied his ideas for their own new ships.

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 gave a distance saving of about on the route from China to London. The canal was not a practical option for sailing vessels, as using a tug

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, suc ...

was difficult and expensive – so this distance saving was not available to them. Steamships immediately made use of this new waterway and found themselves in high demand in China for the start of the 1870 tea season. The steamships were able to obtain a much higher rate of freight

Cargo consists of bulk goods conveyed by water, air, or land. In economics, freight is cargo that is transported at a freight rate for commercial gain. ''Cargo'' was originally a shipload but now covers all types of freight, including trans ...

than sailing ships and the insurance premium for the cargo was less. So successful were the steamers using the Suez Canal that, in 1871, 45 were built in Clyde shipyards alone for Far Eastern trade.

Triple expansion engines

Throughout the 1870s, compound-engined steamships and sailing vessels coexisted in an economic equilibrium: the operating costs of steamships were still too high in certain trades, so sail was the only commercial option in many situations. The compound engine, where steam was expanded twice in two separate cylinders, still had inefficiencies. The solution was the triple expansion engine, in which steam was successively expanded in a high pressure, intermediate pressure and a low pressure cylinder. The theory of this was established in the 1850s by John Elder, but it was clear that triple expansion engines needed steam at, by the standards of the day, very high pressures. The existing boiler technology could not deliver this. Wrought iron could not provide the strength for the higher pressures. Steel became available in larger quantities in the 1870s, but the quality was variable. The overall design of boilers was improved in the early 1860s, with the Scotch-type boilers - but at that date these still ran at the lower pressures that were then current. The first ship fitted with triple expansion engines was ''Propontis'' (launched in 1874). She was fitted with boilers that operated at - but these had technical problems and had to be replaced with ones that ran at . This substantially degraded performance. There were a few further experiments until went into service on the route from Britain to Australia. Her triple expansion engine was designed by Dr A C Kirk, the engineer who had developed the machinery for ''Propontis''. The difference was the use of two double ended Scotch type steel boilers, running at . These boilers had patent corrugated furnaces that overcame the competing problems of heat transfer and sufficient strength to deal with the boiler pressure. ''Aberdeen'' was a marked success, achieving in trials, at 1,800 indicated horsepower, a fuel consumption of of coal per indicated horsepower. This was a reduction in fuel consumption of about 60%, compared to a typical steamer built ten years earlier. In service, this translated into less than 40 tons of coal a day when travelling at . Her maiden outward voyage to

There were a few further experiments until went into service on the route from Britain to Australia. Her triple expansion engine was designed by Dr A C Kirk, the engineer who had developed the machinery for ''Propontis''. The difference was the use of two double ended Scotch type steel boilers, running at . These boilers had patent corrugated furnaces that overcame the competing problems of heat transfer and sufficient strength to deal with the boiler pressure. ''Aberdeen'' was a marked success, achieving in trials, at 1,800 indicated horsepower, a fuel consumption of of coal per indicated horsepower. This was a reduction in fuel consumption of about 60%, compared to a typical steamer built ten years earlier. In service, this translated into less than 40 tons of coal a day when travelling at . Her maiden outward voyage to Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/ Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a me ...

took 42 days, with one coaling stop, carrying 4,000 tons of cargo.

Other similar ships were rapidly brought into service over the next few years. By 1885 the usual boiler pressure was and virtually all ocean-going steamships being built were ordered with triple expansion engines. Within a few years, new installations were running at . The tramp steamers that operated at the end of the 1880s could sail at with a fuel consumption of of coal per ton mile travelled. This level of efficiency meant that steamships could now operate as the primary method of maritime transport in the vast majority of commercial situations.

Era of the ocean liner

By 1870 a number of inventions such as the

By 1870 a number of inventions such as the screw propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

, the compound engine

A compound engine is an engine that has more than one stage for recovering energy from the same working fluid, with the exhaust from the first stage passing through the second stage, and in some cases then on to another subsequent stage or even s ...

, and the triple-expansion engine made trans-oceanic shipping on a large scale economically viable. In 1870 the White Star Line

The White Star Line was a British shipping company. Founded out of the remains of a defunct packet company, it gradually rose up to become one of the most prominent shipping lines in the world, providing passenger and cargo services between ...

’s set a new standard for ocean travel by having its first-class cabins amidships, with the added amenity of large portholes, electricity and running water. The size of ocean liners increased from 1880 to meet the needs of the human migration

Human migration is the movement of people from one place to another with intentions of settling, permanently or temporarily, at a new location (geographic region). The movement often occurs over long distances and from one country to another (ex ...

to the United States and Australia.

and her sister ship were the last two Cunard liners of the period to be fitted with auxiliary sails. Both ships were built by John Elder & Co. of Glasgow, Scotland, in 1884. They were record breakers by the standards of the time, and were the largest liners then in service, plying the Liverpool to New York route.

was the largest steamship in the world when she sank in 1912; a subsequent major sinking of a steamer was that of the , as an act of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

Launched in 1938, was the largest passenger steamship ever built. Launched in 1969, ''

Launched in 1938, was the largest passenger steamship ever built. Launched in 1969, ''Queen Elizabeth 2

''Queen Elizabeth 2'' (''QE2'') is a retired British ocean liner converted into a floating hotel. Originally built for the Cunard Line, the ship, named as the second ship named ''Queen Elizabeth'', was operated by Cunard as both a transatlanti ...

'' (QE2) was the last passenger steamship to cross the Atlantic Ocean on a scheduled liner voyage before she was converted to diesels in 1986. The last major passenger ship built with steam turbines was the ''Fairsky

The Turbine Steamship ''Fairsky'' was a one-class Italian-styled passenger ship operated by the Sitmar Line, best known for service on the migrant passenger route from Britain to Australia from May 1958 until February 1972. After a 20-month lay- ...

'', launched in 1984, later ''Atlantic Star'', reportedly sold to Turkish shipbreakers in 2013.

Most luxury yachts at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries were steam driven (see luxury yacht; also Cox & King yachts). Thomas Assheton Smith was an English aristocrat who forwarded the design of the steam yacht in conjunction with the Scottish marine engineer Robert Napier.

Decline of the steamship

The decline of the steamship began afterWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. Many had been lost in the war, and marine diesel engine

The diesel engine, named after Rudolf Diesel, is an internal combustion engine in which ignition of the fuel is caused by the elevated temperature of the air in the cylinder due to mechanical compression; thus, the diesel engine is a so-ca ...

s had finally matured as an economical and viable alternative to steam power. The diesel engine had far better thermal efficiency than the reciprocating steam engine

A reciprocating engine, also often known as a piston engine, is typically a heat engine that uses one or more reciprocating pistons to convert high temperature and high pressure into a rotating motion. This article describes the common featu ...

, and was far easier to control. Diesel engines also required far less supervision and maintenance than steam engines, and as an internal combustion engine it did not need boilers or a water supply, therefore was more space efficient.

The Liberty ship

Liberty ships were a ship class, class of cargo ship built in the United States during World War II under the Emergency Shipbuilding Program. Though British in concept, the design was adopted by the United States for its simple, low-cost constr ...

s were the last major steamship class equipped with reciprocating engines. The last Victory ship

The Victory ship was a class of cargo ship produced in large numbers by North American shipyards during World War II to replace losses caused by German submarines. They were a more modern design compared to the earlier Liberty ship, were slig ...

s had already been equipped with marine diesels, and diesel engines superseded both steamers and windjammer

A windjammer is a commercial sailing ship with multiple masts that may be square rigged, or fore-and-aft rigged, or a combination of the two. The informal term "windjammer" arose during the transition from the Age of Sail to the Steam-powered ...

s soon after World War Two. Most steamers were used up to their maximum economical life span, and no commercial ocean-going steamers with reciprocating engines have been built since the 1960s.

1970–present day

steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turb ...

s. After the demonstration by British engineer Charles Parsons of his steam turbine-driven yacht, '' Turbinia'', in 1897, the use of steam turbines for propulsion quickly spread. The Cunard RMS ''Mauretania'', built in 1906 was one of the first ocean liners to use the steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turb ...

(with a late design change shortly before her keel was laid down) and was soon followed by all subsequent liners.

Most capital ships of the major navies were propelled by steam turbines burning bunker fuel in both World Wars. Large naval vessels and submarines continue to be operated with steam turbines, using nuclear reactors

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat fr ...

to boil the water.

NS ''Savannah'', was the first nuclear-powered cargo-passenger ship, and was built in the late 1950s as a demonstration project for the potential use of nuclear energy.

Thousands of Liberty Ships (powered by steam piston engines) and Victory Ships (powered by steam turbine engines) were built in World War II. A few of these survive as floating museums and sail occasionally: SS ''Jeremiah O'Brien'', SS ''John W. Brown'', '' SS ''American Victory'', SS ''Lane Victory'', and SS ''Red Oak Victory''.

A steam turbine ship can be either direct propulsion (the turbines, equipped with a reduction gear, rotate directly the propellers), or turboelectric

A turbo-electric transmission uses electric generators to convert the mechanical energy of a turbine (steam or gas) into electric energy, which then powers electric motors and converts back into mechanical energy that power the driveshafts.

Tur ...

(the turbines rotate electric generators, which in turn feed electric motors operating the propellers).

While steam turbine-driven merchant ships such as the ''Algol''-class cargo ships (1972–1973), ALP Pacesetter-class container ships (1973–1974) and very large crude carrier

An oil tanker, also known as a petroleum tanker, is a ship designed for the bulk transport of oil or its products. There are two basic types of oil tankers: crude tankers and product tankers. Crude tankers move large quantities of unrefined c ...

s were built until the 1970s, the use of steam for marine propulsion in the commercial market has declined dramatically due to the development of more efficient diesel engine

The diesel engine, named after Rudolf Diesel, is an internal combustion engine in which ignition of the fuel is caused by the elevated temperature of the air in the cylinder due to mechanical compression; thus, the diesel engine is a so-ca ...

s. One notable exception are LNG carrier

An LNG carrier is a tank ship designed for transporting liquefied natural gas (LNG).

History

The first LNG carrier '' Methane Pioneer'' () carrying , classed by Bureau Veritas, left the Calcasieu River on the Louisiana Gulf coast on 25 Januar ...

s which use boil-off gas from the cargo tanks as fuel. However, even there the development of dual-fuel engines has pushed steam turbines into a niche market with about 10% market share in newbuildings in 2013. Lately, there has been some development in hybrid power plants where the steam turbine is used together with gas engines. As of August 2017 the newest class of Steam Turbine ships are the ''Seri Camellia''-class LNG carriers built by Hyundai Heavy Industries (HHI) starting in 2016 and comprising five units.

Nuclear powered ships are basically steam turbine vessels. The boiler is heated, not by heat of combustion, but by the heat generated by nuclear reactor. Most atomic-powered ships today are either aircraft carriers or submarines.

See also

* Steamboat *Paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine that drives paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses wer ...

* History of the steam engine

* International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)#Travel

* List of steam frigates of the United States Navy

*Bibliography of early American naval history

Historical accounts for early U.S. naval history now occur across the spectrum of two and more centuries. This Bibliography lends itself primarily to reliable sources covering early U.S. naval history beginning around the American Revolution per ...

* Lake steamers of North America

Notes

References

Bibliography

*E'Book

*Bennett, Frank M. (1897). ''The steam navy of the United States''. Warren & Company Publishers Philadelphia. p. 502.

E'Book

* Bradford, James C. (1986). ''Captains of the Old Steam Navy: Makers of the American Tradition, 1840–1880''. Naval Institute Press, p. 356,

Url

*Canney, Donald L. (1998). ''Lincoln's Navy: The Ships, Men and Organization, 1861–65''. Naval Institute Press. p. 232

Url

*

Url

*

E'Book

* Lambert, Andrew (1984). ''Battleships in Transition, the Creation of the Steam Battlefleet 1815–1860''. Conway Maritime Press. *

Mahan, Alfred Thayer

Alfred Thayer Mahan (; September 27, 1840 – December 1, 1914) was a United States naval officer and historian, whom John Keegan called "the most important American strategist of the nineteenth century." His book '' The Influence of Sea Power ...

, n (1907). p : ''From sail to steam: recollections of naval life''. Harper & Brothers, New York, London, p. 325E'Book

E'Book

E'Book

*

E'Book

Url

Further reading

Book

External links

*{{Commons category-inline, SteamshipsTransportation Photographs Collection

- University of Washington Library Steamships Steam engines Steam engine technology