State Duma (Russian Empire) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The State Duma, also known as the Imperial Duma, was the

Coming under pressure from the

Coming under pressure from the

The first Duma was established with around 500 deputies; most radical left parties, such as the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries and the

The first Duma was established with around 500 deputies; most radical left parties, such as the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries and the

The Second Duma (from 20 February 1907 to 3 June 1907) lasted 103 days. One of the new members was

The Second Duma (from 20 February 1907 to 3 June 1907) lasted 103 days. One of the new members was

The Fourth Duma of 15 November 1912 – 6 October 1917, elected in September/October, was also of limited political influence. The first session was held from 15 November 1912 to 25 June 1913, and the second session from 15 October 1913 to 14 June 1914. On 1 July 1914 the Tsar suggested that the Duma should be reduced to merely a consultative body, but an extraordinary session was held on 26 July 1914 during the

The Fourth Duma of 15 November 1912 – 6 October 1917, elected in September/October, was also of limited political influence. The first session was held from 15 November 1912 to 25 June 1913, and the second session from 15 October 1913 to 14 June 1914. On 1 July 1914 the Tsar suggested that the Duma should be reduced to merely a consultative body, but an extraordinary session was held on 26 July 1914 during the

Speech from the Throne by Nicholas II at Opening of the State Duma, photo essay with commentaryFour Dumas of Imperial Russia

{{Authority control 1905 establishments in the Russian Empire 1917 disestablishments in Russia

lower house

A lower house is one of two Debate chamber, chambers of a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the upper house. Despite its official position "below" the upper house, in many legislatures worldwide, the lower house has co ...

of the Governing Senate

The Governing Senate (russian: Правительствующий сенат, Pravitelstvuyushchiy senat) was a legislative, judicial, and executive body of the Russian Emperors, instituted by Peter the Great to replace the Boyar Duma and last ...

in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, while the upper house

An upper house is one of two Debate chamber, chambers of a bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the lower house.''Bicameralism'' (1997) by George Tsebelis The house formally designated as the upper house is usually smalle ...

was the State Council State Council may refer to:

Government

* State Council of the Republic of Korea, the national cabinet of South Korea, headed by the President

* State Council of the People's Republic of China, the national cabinet and chief administrative auth ...

. It held its meetings in the Taurida Palace

Tauride Palace (russian: Таврический дворец, translit=Tavrichesky dvorets) is one of the largest and most historically important palaces in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Construction and early use

Prince Grigory Potemkin of Tauride ...

in St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. It convened four times between 27 April 1906 and the collapse of the Empire in February 1917. The first and the second dumas were more democratic and represented a greater number of national types than their successors. The third duma was dominated by gentry, landowners and businessmen. The fourth duma held five sessions; it existed until 2 March 1917, and was formally dissolved on 6 October 1917.

History

Coming under pressure from the

Coming under pressure from the Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

, on August 6, 1905 (O.S.), Sergei Witte

Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte (; ), also known as Sergius Witte, was a Russian statesman who served as the first prime minister of the Russian Empire, replacing the tsar as head of the government. Neither a liberal nor a conservative, he attract ...

(appointed by Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pola ...

to manage peace negotiations with Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

after the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

of 1904–1905) issued a manifesto about the convocation of the Duma, initially thought to be a purely advisory body, the so-called Bulygin-Duma. In the subsequent October Manifesto

The October Manifesto (russian: Октябрьский манифест, Манифест 17 октября), officially "The Manifesto on the Improvement of the State Order" (), is a document that served as a precursor to the Russian Empire's fi ...

, the Tsar promised to introduce further civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties may ...

, provide for broad participation in a new "State Duma", and endow the Duma with legislative and oversight powers. The State Duma was to be the lower house

A lower house is one of two Debate chamber, chambers of a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the upper house. Despite its official position "below" the upper house, in many legislatures worldwide, the lower house has co ...

of a parliament, and the State Council of Imperial Russia

The State Council ( rus, Госуда́рственный сове́т, p=ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)ɨj sɐˈvʲet) was the supreme state advisory body to the Tsar in Imperial Russia. From 1906, it was the upper house of the parliament under the ...

the upper house

An upper house is one of two Debate chamber, chambers of a bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the lower house.''Bicameralism'' (1997) by George Tsebelis The house formally designated as the upper house is usually smalle ...

.

However, Nicholas II was determined to retain his autocratic power (in which he succeeded). On April 23, 1906 ( O.S.), the Tsar issued the Fundamental Laws, which gave him the title of "supreme autocrat". Although no law could be made without the Duma's assent, neither could the Duma pass laws without the approval of the noble-dominated State Council (half of which was to be appointed directly by the Tsar), and the Tsar himself retained a veto. The laws stipulated that ministers

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of governme ...

could not be appointed by, and were not responsible to, the Duma, thus denying responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive bran ...

at the executive level. Furthermore, the Tsar had the power to dismiss the Duma and announce new elections whenever he wished; article 87 allowed him to pass temporary (emergency) laws by decrees. All these powers and prerogatives assured that, in practice, the Government of Russia continued to be a non-official absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constitut ...

. It was in this context that the first Duma opened four days later, on April 27, 1906.

First Duma

The first Duma was established with around 500 deputies; most radical left parties, such as the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries and the

The first Duma was established with around 500 deputies; most radical left parties, such as the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

had boycotted the election, leaving the moderate Constitutional Democrats

)

, newspaper = ''Rech''

, ideology = ConstitutionalismConstitutional monarchismLiberal democracyParliamentarism Political pluralismSocial liberalism

, position = Centre to centre-left

, international =

, colours ...

(Kadets) with the most deputies (around 184). Second came an alliance of slightly more radical leftists, the Trudoviks

The Trudoviks (russian: Трудова́я гру́ппа, translit=Trudovaya gruppa, lit=Labour Group) were a social-democratic political party of Russia in early 20th century.

History

The Trudoviks were a breakaway of the Socialist Revolut ...

(Laborites) with around 100 deputies. To the right of both were a number of smaller parties, including the Octobrists

The Union of 17 October (russian: Союз 17 Октября, ''Soyuz 17 Oktyabrya''), commonly known as the Octobrist Party (Russian: Октябристы, ''Oktyabristy''), was a liberal-reformist constitutional monarchist political party in la ...

. Together, they had around 45 deputies. Other deputies, mainly from peasant groups, were unaffiliated.

The Kadets were among the only political parties capable of consistently drawing voters due to their relatively moderate political stance. The Kadets drew from an especially urban population, often failing to draw the attention of rural communities who were instead committed to other parties.

The Duma ran for 73 days until 8 July 1906, with little success. The Tsar and his loyal Prime Minister Ivan Goremykin

Ivan Logginovich Goremykin (russian: Ива́н Лóггинович Горемы́кин, Iván Lógginovich Goremýkin) (8 November 183924 December 1917) was a Russian politician who served as the prime minister of the Russian Empire in 1906 a ...

were keen to keep it in check, and reluctant to share power; the Duma, on the other hand, wanted continuing reform, including electoral reform, and, most prominently, land reform. Sergei Muromtsev

Sergey Andreevich Muromtsev (russian: Серге́й Андре́евич Му́ромцев) (October 5, Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._23_September.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/> O.S._23_September">O ...

, Professor of Law at Moscow University, was elected Chairman. Lev Urusov held a famous speech. Scared by this liberalism, the Tsar dissolved the Duma, reportedly saying "curse the Duma. It is all Witte's doing". The same day, Pyotr Stolypin

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin ( rus, Пётр Арка́дьевич Столы́пин, p=pʲɵtr ɐrˈkadʲjɪvʲɪtɕ stɐˈlɨpʲɪn; – ) was a Russian politician and statesman. He served as the third prime minister and the interior minist ...

was named as the new Prime Minister who promoted a coalition cabinet

A coalition government is a form of government in which political parties cooperate to form a government. The usual reason for such an arrangement is that no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an election, an atypical outcome in ...

, as did Vasily Maklakov

Vasily Alekseyevich Maklakov (Russian: Васи́лий Алексе́евич Маклако́в; , Moscow – July 15, 1957, Baden, Switzerland) was a Russian student activist, a trial lawyer and liberal parliamentary deputy, an orator, and on ...

, Alexander Izvolsky

Count Alexander Petrovich Izvolsky or Iswolsky (russian: Алекса́ндр Петро́вич Изво́льский, , Moscow – 16 August 1919, Paris) was a Russian diplomat remembered as a major architect of Russia's alliance with Grea ...

, Dmitri Trepov and the Tsar.

In frustration, Paul Miliukov

Pavel Nikolayevich Milyukov ( rus, Па́вел Никола́евич Милюко́в, p=mʲɪlʲʊˈkof; 31 March 1943) was a Russian historian and liberal politician. Milyukov was the founder, leader, and the most prominent member of the Con ...

, who regarded the Russian Constitution of 1906

The Russian Constitution of 1906 refers to a major revision of the 1832 Fundamental Laws of the Russian Empire, which transformed the formerly absolutist state into one in which the emperor agreed for the first time to share his autocratic powe ...

as a mock-constitution, and approximately 200 deputies mostly from the liberal Kadet

)

, newspaper = ''Rech''

, ideology = ConstitutionalismConstitutional monarchismLiberal democracyParliamentarism Political pluralismSocial liberalism

, position = Centre to centre-left

, international =

, colours ...

s party decamped to Vyborg, then part of Russian Finland

The Grand Duchy of Finland ( fi, Suomen suuriruhtinaskunta; sv, Storfurstendömet Finland; russian: Великое княжество Финляндское, , all of which literally translate as Grand Principality of Finland) was the predecessor ...

, to discuss the way forward. From there, they issued the Vyborg Appeal

The Vyborg Manifesto (russian: Выборгское воззвание, translit=Vyborgskoye Vozzvaniye, fi, Viipurin manifesti, sv, Viborgsmanifestet); also called the Vyborg Appeal) was a proclamation signed by several Russian politicians, pri ...

, which called for civil disobedience and a revolution. Largely ignored, it ended in their arrest and the closure of Kadet Party offices. This, among other things, helped pave the way for an alternative makeup for the second Duma.

Second Duma

The Second Duma (from 20 February 1907 to 3 June 1907) lasted 103 days. One of the new members was

The Second Duma (from 20 February 1907 to 3 June 1907) lasted 103 days. One of the new members was Vladimir Purishkevich

Vladimir Mitrofanovich Purishkevich ( rus, Влади́мир Митрофа́нович Пуришке́вич, p=pʊrʲɪˈʂkʲevʲɪt͡ɕ; , Kishinev – 1 February 1920, Novorossiysk, Russia) was a far-right politician in Imperial Russia, no ...

, strongly opposed to the October Manifesto

The October Manifesto (russian: Октябрьский манифест, Манифест 17 октября), officially "The Manifesto on the Improvement of the State Order" (), is a document that served as a precursor to the Russian Empire's fi ...

. The Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

s and Menshevik

The Mensheviks (russian: меньшевики́, from меньшинство 'minority') were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

The factions eme ...

s (that is, both factions of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

) and the Socialist Revolutionaries all abandoned their policies of boycotting elections to the Duma, and consequently won a number of seats. The election was an overall success for Russian left-wing parties: the Trudoviks

The Trudoviks (russian: Трудова́я гру́ппа, translit=Trudovaya gruppa, lit=Labour Group) were a social-democratic political party of Russia in early 20th century.

History

The Trudoviks were a breakaway of the Socialist Revolut ...

won 104 seats, the Social Democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

65 (47 Mensheviks and 18 Bolsheviks), the Socialist Revolutionaries

The Socialist Revolutionary Party, or the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries (the SRs, , or Esers, russian: эсеры, translit=esery, label=none; russian: Партия социалистов-революционеров, ), was a major politi ...

37 and the Popular Socialists

The Popular Socialist Party () emerged in Russia in the early twentieth century.

History

The roots of the Popular Socialist Party (NSP) lay in the 'Legal Populist' movement of the 1890s, and its founders looked upon N.K. Mikhailovsky and Alex ...

16.

The Kadets (by this point the most moderate and centrist party), found themselves outnumbered two-to-one by their more radical counterparts. Even so, Stolypin and the Duma could not build a working relationship, being divided on the issues of land confiscation (which the socialists and, to a lesser extent, the Kadets, supported but the Tsar and Stolypin vehemently opposed) and Stolypin's brutal attitude towards law and order.

On 1 June 1907, prime minister Pyotr Stolypin

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin ( rus, Пётр Арка́дьевич Столы́пин, p=pʲɵtr ɐrˈkadʲjɪvʲɪtɕ stɐˈlɨpʲɪn; – ) was a Russian politician and statesman. He served as the third prime minister and the interior minist ...

accused Social Democrats of preparing an armed uprising and demanded that the Duma exclude 55 Social Democrats from Duma sessions and strip 16 of their parliamentary immunity

Parliamentary immunity, also known as legislative immunity, is a system in which politicians such as president, vice president, governor, lieutenant governor, member of parliament, member of legislative assembly, member of legislative council, s ...

. When this ultimatum was rejected by Duma, it was dissolved on 3 June by an ukase

In Imperial Russia, a ukase () or ukaz (russian: указ ) was a proclamation of the tsar, government, or a religious leader (patriarch) that had the force of law. "Edict" and "decree" are adequate translations using the terminology and concepts ...

(imperial decree) in what became known as the Coup of June 1907

The Coup of June 1907, sometimes known as Stolypin's Coup (russian: Третьеиюньский переворот, Tretyeiyunskiy perevorot "Coup of June 3rd"), is the name commonly given to the dissolution of the Second State Duma of the Russi ...

.

The Tsar was unwilling to be rid of the State Duma, despite these problems. Instead, using emergency powers, Stolypin and the Tsar changed the electoral law and gave greater electoral value to the votes of landowners and owners of city properties, and less value to the votes of the peasantry, whom he accused of being "misled", and, in the process, breaking his own Fundamental Laws.

Third Duma

This ensured the third Duma (7 November 1907 – 3 June 1912) would be dominated by gentry, landowners and businessmen. The number of deputies from non-Russian regions was greatly reduced. The system facilitated better, if hardly ideal, cooperation between the Government and the Duma; consequently, the Duma lasted a full five-year term, and succeeded in 200 pieces of legislation and voting on some 2500 bills. Due to its more noble, andGreat Russian

Russian (russian: русский язык, russkij jazyk, link=no, ) is an East Slavic language mainly spoken in Russia. It is the native language of the Russians, and belongs to the Indo-European language family. It is one of four living Eas ...

composition, the third Duma, like the first, was also given a nickname, "The Duma of the Lords and Lackeys" or "The Master's Duma". The Octobrist party were the largest, with around one-third of all the deputies. This Duma, less radical and more conservative, left clear that the new electoral system would always generate a landowners-controlled Duma in which the tsar would have vast amounts of influence over, which in turn would be under complete submission to the Tsar, unlike the first two Dumas.

In terms of legislation, the Duma supported an improvement in Russia's military capabilities, Stolypin's plans for land reform and basic social welfare measures. The power of Nicholas' hated land captains was consistently reduced. It also supported more regressive laws, however, such as on the question of Finnish autonomy and Russification

Russification (russian: русификация, rusifikatsiya), or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether involuntarily or voluntarily, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian cultur ...

, with a fear of the Empire breaking up being prevalent. Since the dissolution of the Second Duma a very large proportion of the Empire was either under martial law, or one of the milder forms of the state of siege. It was forbidden, for instance, at various times and in various places, to refer to the dissolution of the Second Duma, to the funeral of the Speaker of the First Duma, Muromtsev, and the funeral of Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

, to the fanatical ight-wingmonk Iliodor

Sergei Michailovich Trufanov (Russian: Серге́й Миха́йлович Труфа́нов; formerly Hieromonk Iliodor or Hieromonk Heliodorus, russian: Иеромонах Илиодор; October 19, 1880 – 28 January 1952) was a lapsed hie ...

, or to the notorious ''agent provocateur'', Yevno Azef

Yevno Fishelevich Azef (russian: Евгений Филиппович (Евно Фишелевич) Азеф, also transliterated as ''Evno'' Azef, 1869–1918) was a Russian socialist revolutionary who also operated as a double agent and agent ...

. Stolypin was assassinated in September 1911 and replaced by his Finance Minister Vladimir Kokovtsov

Count Vladimir Nikolayevich Kokovtsov (russian: Влади́мир Никола́евич Коко́вцов; – 29 January 1943) was a Russian politician who served as the Prime Minister of Russia from 1911 to 1914, during the reign of Empe ...

. It enabled Count Kokovtsov to balance the budget regularly and even to spend on productive purposes.

Fourth Duma

The Fourth Duma of 15 November 1912 – 6 October 1917, elected in September/October, was also of limited political influence. The first session was held from 15 November 1912 to 25 June 1913, and the second session from 15 October 1913 to 14 June 1914. On 1 July 1914 the Tsar suggested that the Duma should be reduced to merely a consultative body, but an extraordinary session was held on 26 July 1914 during the

The Fourth Duma of 15 November 1912 – 6 October 1917, elected in September/October, was also of limited political influence. The first session was held from 15 November 1912 to 25 June 1913, and the second session from 15 October 1913 to 14 June 1914. On 1 July 1914 the Tsar suggested that the Duma should be reduced to merely a consultative body, but an extraordinary session was held on 26 July 1914 during the July Crisis

The July Crisis was a series of interrelated diplomatic and military escalations among the major powers of Europe in the summer of 1914, Causes of World War I, which led to the outbreak of World War I (1914–1918). The crisis began on 28 June 1 ...

. The third session gathered from 27 to 29 January 1915, the fourth from 19 July 1915 to 3 September, the fifth from 9 February to 20 June 1916, and the sixth from 1 November to 16 December 1916. No one exactly knew when they would resume their deliberations. It seems the last session was never opened (on 14 February), but kept closed on 27 February 1917.

There was one promising new member in Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, ; Reforms of Russian orthography, original spelling: ( – 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months ...

, a Trudovik

The Trudoviks (russian: Трудова́я гру́ппа, translit=Trudovaya gruppa, lit=Labour Group) were a social-democratic political party of Russia in early 20th century.

History

The Trudoviks were a breakaway of the Socialist Revolut ...

, but also Roman Malinovsky

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

, a Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

who was a double agent for the secret police. In March 1913 the Octobrists

The Union of 17 October (russian: Союз 17 Октября, ''Soyuz 17 Oktyabrya''), commonly known as the Octobrist Party (Russian: Октябристы, ''Oktyabristy''), was a liberal-reformist constitutional monarchist political party in la ...

, led by Alexander Guchkov

Alexander Ivanovich Guchkov (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Гучко́в) (14 October 1862 – 14 February 1936) was a Russian politician, Chairman of the Third Duma and Minister of War in the Russian Provisional Government.

...

, President of the Duma, commissioned an investigation on Grigori Rasputin

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (; rus, links=no, Григорий Ефимович Распутин ; – ) was a Russian mystic and self-proclaimed holy man who befriended the family of Nicholas II, the last Emperor of Russia, thus g ...

to research the allegations being a Khlyst

The Khlysts or Khlysty ( rus, Хлысты, p=xlɨˈstɨ, "whips") were an underground Spiritual Christian sect, which split from the Russian Orthodox Church and existed from the 1600s until the late 20th century.

The New Israel sect that desc ...

. The leading party of the Octobrists divided itself into three different sections.

The Duma "met on 8 August for three hours to pass emergency war credits, ndit was not asked to remain in session because it would only be in the way." The Duma volunteered its own dissolution until 14 February 1915. A serious conflict arose in January as the government kept information on the battlefield (in April at Gorlice

Gorlice ( uk, Горлиці, translit=''Horlytsi'') is a city and an urban municipality ("gmina") in south eastern Poland with around 29,500 inhabitants (2008). It is situated south east of Kraków and south of Tarnów between Jasło and Nowy S ...

) secret to the Duma. In May Guchkov initiated the War Industries Committees in order to unite industrialists who were supplying the army with ammunition and military equipment, to mobilize industry for war needs and prolonged military action, to put political pressure on the tsarist government. On 17 July 1915 the Duma reconvened for six weeks. Its former members became increasingly displeased with Tsarist control of military and governmental affairs and demanded its own reinstatement. When the Tsar refused its call for the replacement of his cabinet on 21 August with a "Ministry of National Confidence", roughly half of the deputies formed a "Progressive Bloc", which in 1917 became a focal point of political resistance. On 3 September 1915 the Duma prorogued.

On the eve of the war the government and the Duma were hovering round one another like indecisive wrestlers, neither side able to make a definite move. The war made the political parties more cooperative and practically formed into one party. When the Tsar announced he would leave for the front at Mogilev

Mogilev (russian: Могилёв, Mogilyov, ; yi, מאָלעוו, Molev, ) or Mahilyow ( be, Магілёў, Mahilioŭ, ) is a city in eastern Belarus, on the Dnieper River, about from the border with Russia's Smolensk Oblast and from the bor ...

, the Progressive Bloc

The Progressive Bloc () is an electoral alliance in the Dominican Republic. The alliance is led by the Dominican Liberation Party

The Dominican Liberation Party ( Spanish: Partido de la Liberación Dominicana, referred to here by its Spanis ...

was formed, fearing Rasputin's influence over Tsarina Alexandra would increase.

The Duma gathered on 9 February 1916 after the 76-year-old Ivan Goremykin

Ivan Logginovich Goremykin (russian: Ива́н Лóггинович Горемы́кин, Iván Lógginovich Goremýkin) (8 November 183924 December 1917) was a Russian politician who served as the prime minister of the Russian Empire in 1906 a ...

had been replaced by Boris Stürmer

Baron Boris Vladimirovich Shturmer (russian: Бори́с Влади́мирович Штю́рмер) (27 July 1848 – 9 September 1917) was a Russian lawyer, a Master of Ceremonies at the Russian Court, and a district governor. He became a ...

as prime minister and on the condition not to mention Rasputin. The deputies were disappointed when Stürmer held his speech. Because of the war, he said, it was not the time for constitutional reforms. For the first time in his life, the Tsar made a visit to the Taurida Palace

Tauride Palace (russian: Таврический дворец, translit=Tavrichesky dvorets) is one of the largest and most historically important palaces in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Construction and early use

Prince Grigory Potemkin of Tauride ...

, which made it practically impossible to hiss at the new prime minister.

On 1 November 1916 (Old Style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 158 ...

) the Duma reconvened and the government under Boris Stürmer

Baron Boris Vladimirovich Shturmer (russian: Бори́с Влади́мирович Штю́рмер) (27 July 1848 – 9 September 1917) was a Russian lawyer, a Master of Ceremonies at the Russian Court, and a district governor. He became a ...

was attacked by Pavel Milyukov

Pavel Nikolayevich Milyukov ( rus, Па́вел Никола́евич Милюко́в, p=mʲɪlʲʊˈkof; 31 March 1943) was a Russian historian and liberal politician. Milyukov was the founder, leader, and the most prominent member of the Con ...

in the State Duma, not gathering since February. In his speech he spoke of "Dark Forces", and highlighted numerous governmental failures with the famous question "Is this stupidity or treason?" Kerensky called the ministers "hired assassins" and "cowards" and said they were "guided by the contemptible Grishka Rasputin!" Stürmer and Protopopov asked in vain for the dissolution of the Duma. Stürmer's resignation looked like a concession to the Duma.Ivan Grigorovich

Ivan Konstantinovich Grigorovich (russian: Ива́н Константи́нович Григоро́вич) (26 January 1853 – 3 March 1930) served as Imperial Russia's last Naval Minister from 1911 until the onset of the 1917 revolution.

Ea ...

and Dmitry Shuvayev

Dmitry Savelyevich Shuvayev (; – 19 December 1937) was a Russian military leader, Infantry General (1912) and Minister of War (1916).

Life

Dmitry Shuvayev graduated from Alexander Military School in 1872. Between 1873 and 1875, he particip ...

declared in the Duma that they had confidence in the Russian people, the navy, and the army; the war could be won.

For the Octobrists and the Kadets, who were the liberals in the parliament, Rasputin, and his support of autocracy and absolute monarchy, was one of their main obstacles. The politicians tried to bring the government under control of the Duma. "To the Okhrana

The Department for Protecting the Public Security and Order (russian: Отделение по охранению общественной безопасности и порядка), usually called Guard Department ( rus, Охранное отд ...

it was obvious by the end of 1916 that the liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

Duma project was superfluous, and that the only two options left were repression or a social revolution."

On 19 November Vladimir Purishkevich

Vladimir Mitrofanovich Purishkevich ( rus, Влади́мир Митрофа́нович Пуришке́вич, p=pʊrʲɪˈʂkʲevʲɪt͡ɕ; , Kishinev – 1 February 1920, Novorossiysk, Russia) was a far-right politician in Imperial Russia, no ...

, one of the founders of the Black Hundreds

The Black Hundred (russian: Чёрная сотня, translit=Chornaya sotnya), also known as the black-hundredists (russian: черносотенцы; chernosotentsy), was a reactionary, monarchist and ultra-nationalist movement in Russia in t ...

, gave a speech in the Duma. He declared the monarchy had become discredited because of what he called the "ministerial leapfrog".

On 2 December, Trepov ascended the tribune in the Duma to read the government programme. The deputies shouted "down with the Ministers! Down with Protopopov!" The Prime-Minister was not allowed to speak and had to leave the rostrum three times. Trepov threatened to shut the troublesome Duma completely in her attempt to control the Tsar. The Tsar, his cabinet, Alexandra, and Rasputin discussed when to open the Duma, on 12 or 19 January, 1 or 14 February, or never. Rasputin suggested to keep the Duma closed until February; Alexandra and Protopopov supported him. On Friday, 16 December Milyukov stated in the Duma: "maybe e will bedismissed to 9 January, maybe until February", but in the evening the Duma was closed until 12 January, by a decree prepared on the day before. A military guard had been on duty at the building.

The February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

began on 22 February when the Tsar had left for the front, and strikes broke out in the Putilov workshops. On 23 February (International Women's Day

International Women's Day (IWD) is a global holiday celebrated annually on March 8 as a focal point in the women's rights movement, bringing attention to issues such as gender equality, reproductive rights, and violence and abuse against wom ...

), women in Saint Petersburg joined the strike, demanding woman suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to gran ...

, an end to Russian food shortages, and the end of World War I. Although all gathering on the streets were absolutely forbidden, on 25 February, some 250,000 people were on strike. The Tsar ordered Sergey Semyonovich Khabalov, an inexperienced and extremely indecisive commander of the Petrograd military district (and Nikolay Iudovich Ivanov

Nikolai Iudovich Ivanov (russian: Никола́й Иу́дович Ива́нов, tr. ; 1851 – 27 January 1919) was a Russian artillery general in the Imperial Russian Army.

Family

Ivanov's family origin was debatable, some sources say ...

) to suppress the rioting by force. On the 27th the Duma delegates received an order from his Majesty that he had decided to prorogue the Duma until April, leaving it with no legal authority to act. The Duma refused to obey, and gathered in a private meeting. According to Buchanan: "It was an act of madness to prorogue the Duma at a moment like the present." "The delegates decided to form a Provisional Committee of the State Duma

The Provisional Committee of the State Duma () was a special government body established on March 12, 1917 (27 February O.S.) by the Fourth State Duma deputies at the outbreak of the February Revolution in the same year. It was formed under th ...

. The Provisional Committee ordered the arrest of all the ex-ministers and senior officials."Orlando Figes

Orlando Guy Figes () is a British historian and writer. Until his retirement, he was Professor of History at Birkbeck College, University of London.

Figes is known for his works on Russian history, such as '' A People's Tragedy'' (1996), ''Nata ...

(2006). ''A People's Tragedy

''A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution, 1891–1924'' is a history book by British historian Orlando Figes on the Russian Revolution and the years leading up to it. It was written between 1989 and 1996, and first edition was published in 1996 ...

: The Russian Revolution: 1891–1924'', p. 328–329. The Tauride Palace was occupied by the crowd and soldiers. "On the evening the Council of Ministers of Russia The Russian Council of Ministers is an executive governmental council that brings together the principal officers of the Executive Branch of the Russian government. This includes the chairman of the government and ministers of federal government dep ...

held its last meeting in the Marinsky Palace

Mariinsky Palace (), also known as Marie Palace, was the last neoclassical Imperial residence to be constructed in Saint Petersburg. It was built between 1839 and 1844, designed by the court architect Andrei Stackenschneider. It houses the ci ...

and formally submitted its resignation to the Tsar when they were cut off from the telephone. Soon a group of Duma members formed the Provisional Committee. Guchkov, along with Vasily Shulgin

Vasily Vitalyevich Shulgin (russian: Васи́лий Вита́льевич Шульги́н; 13 January 1878 – 15 February 1976) was a Russian conservative monarchist, politician and member of the White movement.

Young years

Shulgin was bo ...

, came to the army headquarters near Pskov to persuade the Tsar to abdicate. The committee sent commissars to take over ministries and other government institutions, dismissing Tsar-appointed ministers and formed the Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or f ...

under Georgi Lvov

Prince Georgy Yevgenyevich Lvov (7/8 March 1925) was a Russian aristocrat and statesman who served as the first prime minister of Russia, prime minister of Russian Provisional Government, republican Russia from 15 March to 20 July 1917. During ...

.

On 2 March 1917 the Provisional government decided that the Duma would not be reconvened. Following the Kornilov Affair and the proclamation of the Russian Republic

The Russian Republic,. referred to as the Russian Democratic Federal Republic. in the Decree on the system of government of Russia (1918), 1918 Constitution, was a short-lived state (polity), state which controlled, ''de jure'', the territ ...

, the State Duma was dissolved on 6 October 1917 by the Provisional government; a Provisional Council of the Russian Republic

Provisional Council of the Russian Republic (, (also known as Pre-parliament) was a legislative assembly of the Russian Republic. It convened at the Marinsky Palace on October 20, 1917, but was dissolved by the Bolsheviks on November, 7/8, 1917. ...

was convened on 20th October 1917 as a provisional parliament, in preparation to the election of the Russian Constituent Assembly

The All Russian Constituent Assembly (Всероссийское Учредительное собрание, Vserossiyskoye Uchreditelnoye sobraniye) was a constituent assembly convened in Russia after the October Revolution of 1917. It met fo ...

.

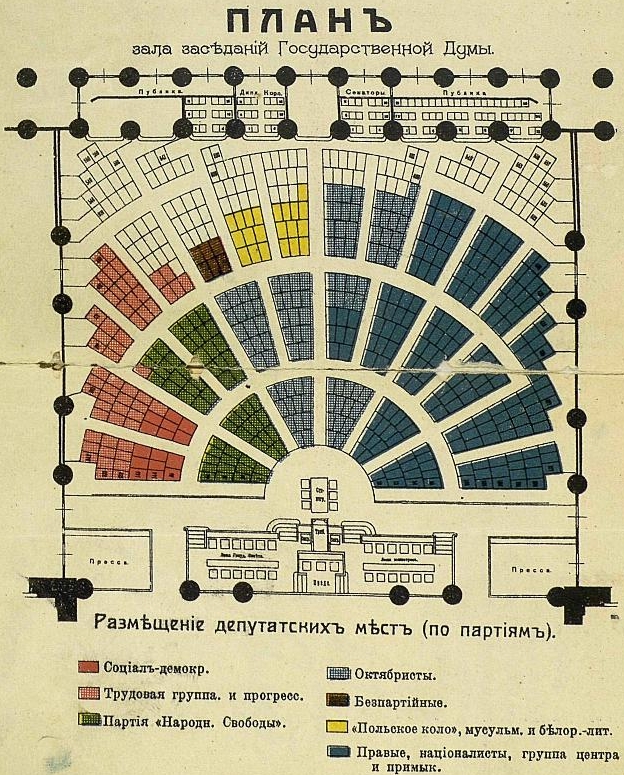

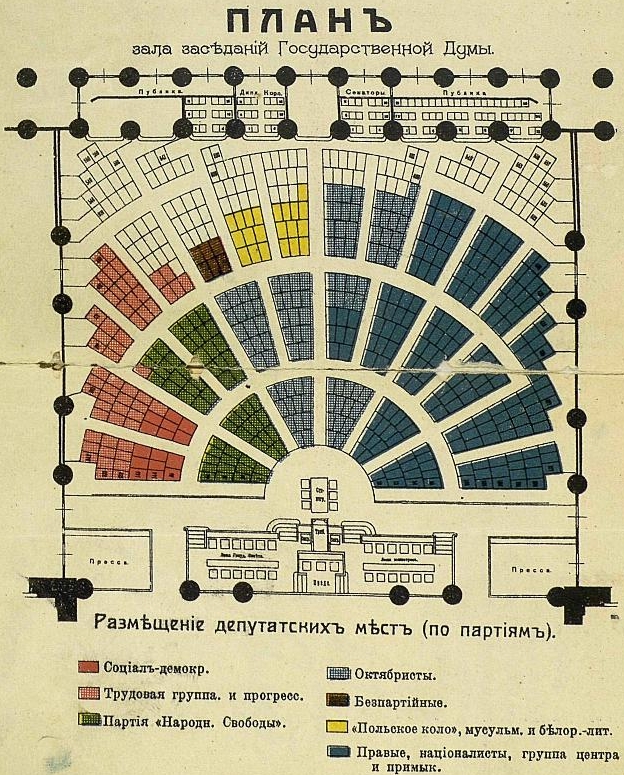

Seats held in Imperial Dumas

Chairmen of the State Duma

*Sergey Muromtsev

Sergey Andreevich Muromtsev (russian: Серге́й Андре́евич Му́ромцев) (October 5, Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._23_September.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/> O.S._23_September">O ...

(1906)

* Fyodor Golovin (1907)

*Nikolay Khomyakov

Nikolay Alekseevich Khomyakov (russian: Никола́й Алексе́евич Хомяко́в; January 19, 1850 – June 28, 1925) was a Russian politician.

Life

Khomyakov was born in Moscow, the son of Aleksey Khomyakov, a well-known Slav ...

(1907–1910)

*Alexander Guchkov

Alexander Ivanovich Guchkov (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Гучко́в) (14 October 1862 – 14 February 1936) was a Russian politician, Chairman of the Third Duma and Minister of War in the Russian Provisional Government.

...

(1910–1911)

*Mikhail Rodzianko

Mikhail Vladimirovich Rodzianko (russian: Михаи́л Влади́мирович Родзя́нко; uk, Михайло Володимирович Родзянко; 21 February 1859, Yekaterinoslav Governorate – 24 January 1924, Beod ...

(1911–1917)

Deputy Chairmen of the State Duma

*The First Duma **PrincePavel Dolgorukov

Prince Pavel Dmitrievich Dolgorukov (russian: Князь Па́вел Дми́триевич Долгору́ков, tr. ; 1866, Tsarskoye Selo – June 9, 1927) was a Russian landowner and aristocrat who was executed by the Bolsheviks in 19 ...

(Cadet Party

)

, newspaper = ''Rech''

, ideology = ConstitutionalismConstitutional monarchismLiberal democracyParliamentarism Political pluralismSocial liberalism

, position = Centre to centre-left

, international =

, colours ...

) 1906

**Nikolay Gredeskul

Nikolay Andreyevich Gredeskul (Russian: Николай Андреевич Гредескул; 20 April 1865 – 8 September 1941) was a Russians, Russian liberalism, liberal politician.

Biography Origins

He was from an old noble family of Moldavi ...

(Cadet Party

)

, newspaper = ''Rech''

, ideology = ConstitutionalismConstitutional monarchismLiberal democracyParliamentarism Political pluralismSocial liberalism

, position = Centre to centre-left

, international =

, colours ...

) 1906

*The Second Duma

**N. N. Podznansky (Left) 1907

**M. E. Berezik ( Trudoviki) 1907

*The Third Duma

**Vol. V. M. Volkonsky (moderately right), bar. A. F. Meyendorff (Octobrist), C. J. Szydlowski (Octobrist), M. Kapustin (Octobrist), I. Sozonovich (right).

*The Fourth Duma

**Prince D. D. Urusov (Progressive Bloc)

***+ Prince V. M. Volkonsky (Centrum-Right) (1912–1913)

**Nikolay Nikolayevich Lvov (Progressive Bloc

The Progressive Bloc () is an electoral alliance in the Dominican Republic. The alliance is led by the Dominican Liberation Party

The Dominican Liberation Party ( Spanish: Partido de la Liberación Dominicana, referred to here by its Spanis ...

) (1913)

** Aleksandr Konovalov (Progressive Bloc

The Progressive Bloc () is an electoral alliance in the Dominican Republic. The alliance is led by the Dominican Liberation Party

The Dominican Liberation Party ( Spanish: Partido de la Liberación Dominicana, referred to here by its Spanis ...

) (1913–1914)

**S. T. Varun-Sekret (Octobrist Party

The Union of 17 October (russian: Союз 17 Октября, ''Soyuz 17 Oktyabrya''), commonly known as the Octobrist Party (Russian: Октябристы, ''Oktyabristy''), was a liberal-reformist constitutional monarchist political party in ...

) (1913–1916)

**Alexander Protopopov

Alexander Dmitrievich Protopopov (; 18 December 1866 – 27 October 1918) was a Russian publicist and politician who served as Minister of the Interior from September 1916 to February 1917.

Protopopov became a leading liberal politician in Rus ...

(Left Wing Octobrist Party

The Union of 17 October (russian: Союз 17 Октября, ''Soyuz 17 Oktyabrya''), commonly known as the Octobrist Party (Russian: Октябристы, ''Oktyabristy''), was a liberal-reformist constitutional monarchist political party in ...

) (1914–1916)

**Nikolai Vissarionovich Nekrasov

Nikolai Vissarionovich Nekrasov (russian: Никола́й Виссарио́нович Некра́сов) (, Saint Petersburg – May 7, 1940, Moscow) was a Russian liberal politician and the last Governor-General of Finland.

Biography

Parliam ...

(Cadet Party

)

, newspaper = ''Rech''

, ideology = ConstitutionalismConstitutional monarchismLiberal democracyParliamentarism Political pluralismSocial liberalism

, position = Centre to centre-left

, international =

, colours ...

) (1916–1917)

**Count V. A. Bobrinsky (Nationalist) (1916–1917)

Notes

References

External links

*Speech from the Throne by Nicholas II at Opening of the State Duma, photo essay with commentary

{{Authority control 1905 establishments in the Russian Empire 1917 disestablishments in Russia

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

Government of the Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...