Name and dedication

Location

History

Early years

The foundation of St Giles' is usually dated to 1124 and attributed to David I The parish was likely detached from the older parish of St Cuthbert's. David raised Edinburgh to the status of a

The foundation of St Giles' is usually dated to 1124 and attributed to David I The parish was likely detached from the older parish of St Cuthbert's. David raised Edinburgh to the status of a Collegiate church

In 1419, During the period of these petitions, William Preston of Gorton had, with the permission of

During the period of these petitions, William Preston of Gorton had, with the permission of Reformation

At the beginning of 1559, with the Scottish Reformation gaining ground, the town council hired soldiers to defend St Giles' from the Reformers; the council also distributed the church's treasures among trusted townsmen for safekeeping. At 3 pm on 29 June 1559 the army of the Lords of the Congregation entered Edinburgh unopposed and, that afternoon,

At the beginning of 1559, with the Scottish Reformation gaining ground, the town council hired soldiers to defend St Giles' from the Reformers; the council also distributed the church's treasures among trusted townsmen for safekeeping. At 3 pm on 29 June 1559 the army of the Lords of the Congregation entered Edinburgh unopposed and, that afternoon, Church and crown: 1567–1633

In 1567, Mary, Queen of Scots was deposed and succeeded by her infant son, James VI, St Giles' was a focal point of the ensuing Marian civil war. After his assassination in January 1570, the James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray, Regent Moray, a leading opponent of Mary, Queen of Scots, was interred within the church;

In 1567, Mary, Queen of Scots was deposed and succeeded by her infant son, James VI, St Giles' was a focal point of the ensuing Marian civil war. After his assassination in January 1570, the James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray, Regent Moray, a leading opponent of Mary, Queen of Scots, was interred within the church; Cathedral

James' son and successor, Charles I, first visited St Giles' on 23 June 1633 during his visit to Scotland for his coronation. He arrived at the church unannounced and displaced the Reader (liturgy), reader with clergy who conducted the service according to the rites of the Church of England. On 29 September that year, Charles, responding to a petition from John Spottiswoode, Archbishop of St Andrews, elevated St Giles' to the status of a cathedral to serve as the seat of the new Bishop of Edinburgh. Work began to remove the internal partition walls and to furnish the interior in the manner of Durham Cathedral.

Work on the church was incomplete when, on 23 July 1637, the replacement in St Giles' of Knox's Book of Common Order by a Scottish version of the Church of England's Book of Common Prayer provoked rioting due to the latter's perceived similarities to Roman Catholic ritual. Tradition attests that this riot was started when a market trader named Jenny Geddes threw her stool at the Dean (Christianity), dean, James Hannay. In response to the unrest, services at St Giles' were temporarily suspended.

James' son and successor, Charles I, first visited St Giles' on 23 June 1633 during his visit to Scotland for his coronation. He arrived at the church unannounced and displaced the Reader (liturgy), reader with clergy who conducted the service according to the rites of the Church of England. On 29 September that year, Charles, responding to a petition from John Spottiswoode, Archbishop of St Andrews, elevated St Giles' to the status of a cathedral to serve as the seat of the new Bishop of Edinburgh. Work began to remove the internal partition walls and to furnish the interior in the manner of Durham Cathedral.

Work on the church was incomplete when, on 23 July 1637, the replacement in St Giles' of Knox's Book of Common Order by a Scottish version of the Church of England's Book of Common Prayer provoked rioting due to the latter's perceived similarities to Roman Catholic ritual. Tradition attests that this riot was started when a market trader named Jenny Geddes threw her stool at the Dean (Christianity), dean, James Hannay. In response to the unrest, services at St Giles' were temporarily suspended.

The events of 23 July 1637 led to the signing of the Covenanters, National Covenant in February 1638, which, in turn, led to the Bishops' Wars, the first conflict of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. St Giles' again became a Presbyterian church and the partitions were restored. Before 1643, the Preston Aisle was also fitted out as a permanent meeting place for the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland.

In autumn 1641, Charles I attended Presbyterian services in the East Kirk under the supervision of its minister, Alexander Henderson (theologian), Alexander Henderson, a leading Covenanter. The King had lost the Bishops' Wars and had come to Edinburgh because the Treaty of Ripon compelled him to ratify Acts of the Parliament of Scotland passed during the ascendancy of the Covenanters.

After the Covenanters' loss at the Battle of Dunbar (1650), Battle of Dunbar, troops of the Commonwealth of England under Oliver Cromwell entered Edinburgh and occupied the East Kirk as a garrison church. John Lambert (general), General John Lambert and Cromwell himself were among English soldiers who preached in the church and, during the Protectorate, the East Kirk and Tolbooth Kirk were each partitioned in two.

At the Restoration (Scotland), Restoration in 1660, the Cromwellian partition was removed from the East Kirk and a new royal loft was installed there. In 1661, the Parliament of Scotland, under Charles II of England, Charles II, restored episcopacy and St Giles' became a cathedral again. At Charles' orders, the body of James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose – a senior supporter of Charles I executed by the Covenanters – was re-interred in St Giles'. The reintroduction of bishops sparked a new period of rebellion and, in the wake of the Battle of Rullion Green in 1666,

The events of 23 July 1637 led to the signing of the Covenanters, National Covenant in February 1638, which, in turn, led to the Bishops' Wars, the first conflict of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. St Giles' again became a Presbyterian church and the partitions were restored. Before 1643, the Preston Aisle was also fitted out as a permanent meeting place for the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland.

In autumn 1641, Charles I attended Presbyterian services in the East Kirk under the supervision of its minister, Alexander Henderson (theologian), Alexander Henderson, a leading Covenanter. The King had lost the Bishops' Wars and had come to Edinburgh because the Treaty of Ripon compelled him to ratify Acts of the Parliament of Scotland passed during the ascendancy of the Covenanters.

After the Covenanters' loss at the Battle of Dunbar (1650), Battle of Dunbar, troops of the Commonwealth of England under Oliver Cromwell entered Edinburgh and occupied the East Kirk as a garrison church. John Lambert (general), General John Lambert and Cromwell himself were among English soldiers who preached in the church and, during the Protectorate, the East Kirk and Tolbooth Kirk were each partitioned in two.

At the Restoration (Scotland), Restoration in 1660, the Cromwellian partition was removed from the East Kirk and a new royal loft was installed there. In 1661, the Parliament of Scotland, under Charles II of England, Charles II, restored episcopacy and St Giles' became a cathedral again. At Charles' orders, the body of James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose – a senior supporter of Charles I executed by the Covenanters – was re-interred in St Giles'. The reintroduction of bishops sparked a new period of rebellion and, in the wake of the Battle of Rullion Green in 1666, Four churches in one: 1689–1843

In 1699, the courtroom in the northern half of the Tolbooth partition was converted into the West St Giles' Parish Church, New North (or Haddo's Hole) Kirk. At the Acts of Union 1707, Union of Scotland and England's Parliaments in 1707, the tune "Why Should I Be Sad on my Wedding Day?" rang out from St Giles' recently installed carillon. During the Jacobite rising of 1745, inhabitants of Edinburgh met in St Giles' and agreed to surrender the city to the advancing army of Charles Edward Stuart.

From 1758 to 1800, Hugh Blair, a leading figure of the Scottish Enlightenment and religious moderate, served as minister of the High Kirk; his sermons were famous throughout Britain and attracted Robert Burns and Samuel Johnson to the church. Blair's contemporary, Alexander Webster, was a leading Evangelicalism, evangelical who, from his pulpit in the Tolbooth Kirk, expounded strict Calvinist doctrine.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Luckenbooths and Tolbooth, which had enclosed the north side of the church, were demolished along with shops built up around the walls of the church. The exposure of the church's exterior revealed its walls were leaning outwards. In 1817, the city council commissioned Archibald Elliot to produce plans for the church's restoration. Elliot's drastic plans proved controversial and, due to a lack of funds, nothing was done with them.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 106.

In 1699, the courtroom in the northern half of the Tolbooth partition was converted into the West St Giles' Parish Church, New North (or Haddo's Hole) Kirk. At the Acts of Union 1707, Union of Scotland and England's Parliaments in 1707, the tune "Why Should I Be Sad on my Wedding Day?" rang out from St Giles' recently installed carillon. During the Jacobite rising of 1745, inhabitants of Edinburgh met in St Giles' and agreed to surrender the city to the advancing army of Charles Edward Stuart.

From 1758 to 1800, Hugh Blair, a leading figure of the Scottish Enlightenment and religious moderate, served as minister of the High Kirk; his sermons were famous throughout Britain and attracted Robert Burns and Samuel Johnson to the church. Blair's contemporary, Alexander Webster, was a leading Evangelicalism, evangelical who, from his pulpit in the Tolbooth Kirk, expounded strict Calvinist doctrine.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Luckenbooths and Tolbooth, which had enclosed the north side of the church, were demolished along with shops built up around the walls of the church. The exposure of the church's exterior revealed its walls were leaning outwards. In 1817, the city council commissioned Archibald Elliot to produce plans for the church's restoration. Elliot's drastic plans proved controversial and, due to a lack of funds, nothing was done with them.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 106.

George IV attended service in the High Kirk during his 1822 Visit of King George IV to Scotland, visit to Scotland. The publicity of the King's visit created impetus to restore the now-dilapidated building. With £20,000 supplied by the city council and the government, William Burn was commissioned to lead the restoration. Burn's initial plans were modest, but, under pressure from the authorities, Burn produced something closer to Elliot's plans.

Between 1829 and 1833, Burn significantly altered the church: he encased the exterior in ashlar, raised the church's roofline and reduced its footprint. He also added north and west doors and moved the internal partitions to create a church in the nave, a church in the choir, and a meeting place for the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in the southern portion. Between these, the crossing and north transept formed a large vestibule. Burn also removed internal monuments; the General Assembly's meeting place in the Preston Aisle; and the police office and fire engine house, the building's last secular spaces.

Burn's contemporaries were split between those who congratulated him on creating a cleaner, more stable building and those who regretted what had been lost or altered.Marshall 2009, p. 115. In the Victorian era and the first half of the 20th century, Burn's work fell far from favour among commentators. Its critics included Robert Louis Stevenson, who stated: "…zealous magistrates and a misguided architect have shorn the design of manhood and left it poor, naked, and pitifully pretentious." Since the second half of the 20th century, Burn's work has been recognised as having secured the church from possible collapse.Fawcett 1994, p. 186.

The High Kirk returned to the choir in 1831. The Tolbooth Kirk returned to the nave in 1832; when they left for a The Hub, Edinburgh, new church on Castlehill in 1843, the nave was occupied by the Haddo's Hole congregation. The General Assembly found its new meeting hall inadequate and met there only once, in 1834; the Old Kirk congregation moved into the space.Dunlop 1988, p. 20.

George IV attended service in the High Kirk during his 1822 Visit of King George IV to Scotland, visit to Scotland. The publicity of the King's visit created impetus to restore the now-dilapidated building. With £20,000 supplied by the city council and the government, William Burn was commissioned to lead the restoration. Burn's initial plans were modest, but, under pressure from the authorities, Burn produced something closer to Elliot's plans.

Between 1829 and 1833, Burn significantly altered the church: he encased the exterior in ashlar, raised the church's roofline and reduced its footprint. He also added north and west doors and moved the internal partitions to create a church in the nave, a church in the choir, and a meeting place for the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in the southern portion. Between these, the crossing and north transept formed a large vestibule. Burn also removed internal monuments; the General Assembly's meeting place in the Preston Aisle; and the police office and fire engine house, the building's last secular spaces.

Burn's contemporaries were split between those who congratulated him on creating a cleaner, more stable building and those who regretted what had been lost or altered.Marshall 2009, p. 115. In the Victorian era and the first half of the 20th century, Burn's work fell far from favour among commentators. Its critics included Robert Louis Stevenson, who stated: "…zealous magistrates and a misguided architect have shorn the design of manhood and left it poor, naked, and pitifully pretentious." Since the second half of the 20th century, Burn's work has been recognised as having secured the church from possible collapse.Fawcett 1994, p. 186.

The High Kirk returned to the choir in 1831. The Tolbooth Kirk returned to the nave in 1832; when they left for a The Hub, Edinburgh, new church on Castlehill in 1843, the nave was occupied by the Haddo's Hole congregation. The General Assembly found its new meeting hall inadequate and met there only once, in 1834; the Old Kirk congregation moved into the space.Dunlop 1988, p. 20.

Victorian era

At the Disruption of 1843, Robert Gordon (minister), Robert Gordon and James Buchanan (minister), James Buchanan, ministers of the High Kirk, left their charges and the established church to join the newly founded Free Church of Scotland (1843-1900), Free Church. A significant number of their congregation left with them; as did William King Tweedie, minister of the first charge of the Tolbooth Kirk, and Charles John Brown, minister of West St Giles' Parish Church, Haddo's Hole Kirk. The Old Kirk congregation was suppressed in 1860. At a public meeting in Edinburgh City Chambers on 1 November 1867, William Chambers, publisher and Lord Provost of Edinburgh, first advanced his ambition to remove the internal partitions and restore St Giles' as a "Westminster Abbey for Scotland".Marshall 2009, p. 120. Chambers commissioned Robert Morham to produce initial plans. Lindsay Mackersy, solicitor and session clerk of the High Kirk, supported Chambers' work and William Hay was engaged as architect; a management board to supervise the design of new windows and monuments was also created. The restoration was part of a movement for Liturgy, liturgical beautification in late 19th century Scottish Presbyterianism and many evangelicals feared the restored St Giles' would more resemble a Roman Catholic church than a Presbyterian one. Nevertheless, the Presbytery of Edinburgh approved plans in March 1870 and the High Kirk was restored between June 1872 and March 1873: the pews and gallery were replaced with stalls and chairs and, for the first time since the Reformation, stained glass and an Pipe organ, organ were introduced. The restoration of the former Old Kirk and the West Kirk began in January 1879. In 1881, West St Giles' Parish Church, the West Kirk vacated St. Giles'.Marshall 2009, p. 127. During the restoration, many human remains were unearthed; these were transported in five large boxes for reinterment in Greyfriars Kirkyard. Although he had managed to view the reunified interior, William Chambers died on 20 May 1883, only three days before John Hamilton-Gordon, 1st Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair, John Hamilton-Gordon, 7th Earl of Aberdeen, Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, ceremonially opened the restored church; Chambers' funeral was held in the church two days after its reopening.20th and 21st centuries

In 1911, George V opened the newly constructed chapel of the knights of the

In 1911, George V opened the newly constructed chapel of the knights of the Architecture

The first St Giles' was likely a small, Romanesque building of the 12th century with a rectangular nave and semi-circular Apse, apsidal chancel. Before the middle of the 13th century, an aisle was added to the south of the church. Archaeological excavations in the 1980s found the 12th-century church was likely constructed of pink sandstone and grey whinstone. The excavations, found the first church was built on a substantial clay platform created to level the steep slope of the area. This platform was surrounded by a boundary ditch. By 1385, this building had likely been replaced by the core of the current church: a nave and aisles of five Bay (architecture), bays, a crossing and transepts, and a choir of four bays. The church was extended in stages between 1387 and 1518. In Richard Fawcett's words, this "almost haphazard addition of large numbers of chapels" produced "an extraordinarily complex plan".Fawcett 2002, p. 45. The resultant profusion of outer aisles is typical of French Gothic architecture, French medieval church architecture but unusual in Britain. Apart from the internal partitioning of the church in the wake of the Reformation, few significant alterations were made until the restoration by William Burn in 1829–1833, which included the removal of several bays of the church, the addition of Clerestory, clerestories to the nave and transepts, and the encasement of the church's exterior in polished ashlar. The church was significantly restored under William Hay between 1872 and 1883, including the removal of the last internal partitions. In the late 19th century, a number of ground level rooms were added around the periphery of the church. The Thistle Chapel was added to the south-east corner of the church by Robert Lorimer in 1909–11. The most significant subsequent restoration commenced in 1979 under Bernard Feilden and Simpson & Brown: this included the levelling of the floor and the rearrangement of the interior around a central communion table.Exterior

The exterior of the church, with the exception of the tower, dates almost entirely from William Burn's restoration of 1829–1833 and afterwards.RCAHMS 1951, p. 26. Prior to this restoration, St Giles' possessed what Richard Fawcett called a "uniquely complex external appearance" as the result of the church's numerous extensions; externally, a number of chapels were emphasised by gables. Following the early 19th century demolition of the Luckenbooths, Tolbooth, and shops built against St Giles', the walls of the church were exposed to be leaning outward by as much as one and a half feet in places. Burn encased the exterior of the building in polished ashlar of gray sandstone from Cullalo in Fife. This layer is tied to the existing walls by iron cramps and varies in width from eight inches (20 centimetres) at the base of the walls to five inches (12.5 centimetres) at the top. Burn co-operated with Robert Reid (architect), Robert Reid, the architect of new buildings in Parliament Square, to ensure the exteriors of their buildings would complement each other. Burn significantly altered the profile of the church: he expanded the transepts, created a

Following the early 19th century demolition of the Luckenbooths, Tolbooth, and shops built against St Giles', the walls of the church were exposed to be leaning outward by as much as one and a half feet in places. Burn encased the exterior of the building in polished ashlar of gray sandstone from Cullalo in Fife. This layer is tied to the existing walls by iron cramps and varies in width from eight inches (20 centimetres) at the base of the walls to five inches (12.5 centimetres) at the top. Burn co-operated with Robert Reid (architect), Robert Reid, the architect of new buildings in Parliament Square, to ensure the exteriors of their buildings would complement each other. Burn significantly altered the profile of the church: he expanded the transepts, created a Tower and crown steeple

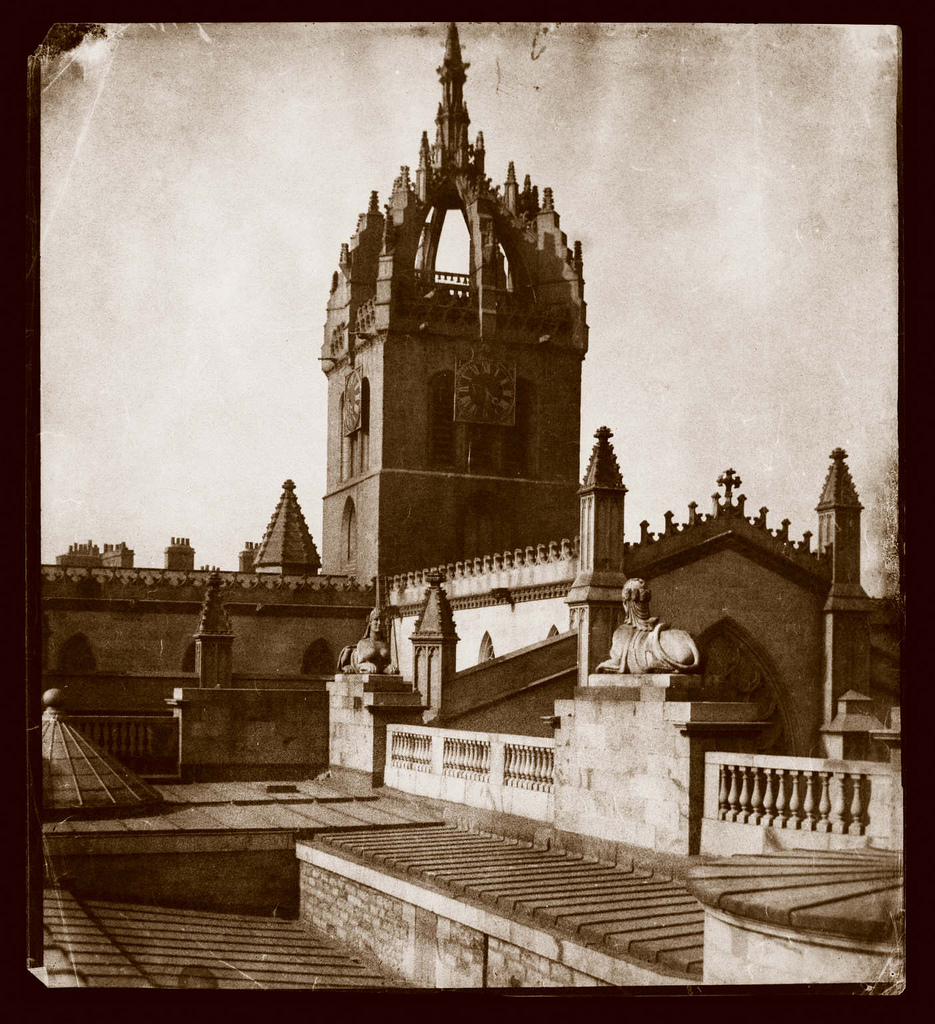

St Giles' possesses a central tower over its crossing (architecture), crossing: this arrangement is common in larger Scottish medieval secular clergy, secular churches. The tower was constructed in two stages. The lower section of the tower has lancet window, lancet openings with "Y"-shaped tracery on every side.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 108. This had likely been completed by 1416, in which year the ''Scotichronicon'' records storks nesting there. The upper stage of the tower has clusters of three Foil (architecture), cusped lancet openings on each side. The date of this work is uncertain, but it may relate both to fines levied on building works at St Giles' in 1486 and to rules of 1491 for the master mason and his men.Marshall 2009, p. 40. From at least 1590, there was a clock face on the tower and, by 1655, there were three faces. The clock faces were removed in 1911.

St Giles' crown steeple is one of Edinburgh's most famous and distinctive landmarks. Cameron Lees wrote of the steeple: "Edinburgh would not be Edinburgh without it." Dendrochronological analysis dates the crown steeple to between 1460 and 1467. The steeple is one of two surviving medieval crown steeples in Scotland: the other is at King's College, Aberdeen and dates from after 1505. John Hume called St Giles' crown steeple "a serene reminder of the imperial aspirations of the late House of Stuart, Stewart monarchs". The design, however, is English in origin, being found at Newcastle Cathedral, St Nicholas' Church, Newcastle before it was introduced to Scotland at St Giles'; the medieval St Mary-le-Bow, City of London, London, may also have possessed a crown steeple. Another crown steeple existed at St Michael's Parish Church, Linlithgow until 1821 and others may have been planned, and possibly begun, at the parish churches of St Mary's Collegiate Church, Haddington, Haddington and Dundee Parish Church (St Mary's), Dundee. These other examples are composed only of diagonal flying buttresses springing from the four corners of the tower; whereas the St Giles' steeple is unique among medieval crown steeples in being composed of eight buttresses: four springing from the corners and four springing from the centre of each side of the tower.MacGibbon and Ross 1896, ii p. 449.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 109.

For the arrival into Edinburgh of Anne of Denmark in 1590, 21 weather vanes were added to the crests of the steeple; these were removed prior to 1800 and replacements were installed in 2005. The steeple was repaired by John Mylne (died 1667), John Mylne the Younger in 1648. Mylne added pinnacles half-way up the crests of the buttresses; he is also largely responsible for the present appearance of the central pinnacle and may have rebuilt the tower's Tracery, traceried parapet.Hay 1976, p. 252. The Weather vane, weathercock atop the central pinnacle was created by Alexander Anderson in 1667; it replaced an earlier weathercock of 1567 by Alexander Honeyman.

St Giles' possesses a central tower over its crossing (architecture), crossing: this arrangement is common in larger Scottish medieval secular clergy, secular churches. The tower was constructed in two stages. The lower section of the tower has lancet window, lancet openings with "Y"-shaped tracery on every side.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 108. This had likely been completed by 1416, in which year the ''Scotichronicon'' records storks nesting there. The upper stage of the tower has clusters of three Foil (architecture), cusped lancet openings on each side. The date of this work is uncertain, but it may relate both to fines levied on building works at St Giles' in 1486 and to rules of 1491 for the master mason and his men.Marshall 2009, p. 40. From at least 1590, there was a clock face on the tower and, by 1655, there were three faces. The clock faces were removed in 1911.

St Giles' crown steeple is one of Edinburgh's most famous and distinctive landmarks. Cameron Lees wrote of the steeple: "Edinburgh would not be Edinburgh without it." Dendrochronological analysis dates the crown steeple to between 1460 and 1467. The steeple is one of two surviving medieval crown steeples in Scotland: the other is at King's College, Aberdeen and dates from after 1505. John Hume called St Giles' crown steeple "a serene reminder of the imperial aspirations of the late House of Stuart, Stewart monarchs". The design, however, is English in origin, being found at Newcastle Cathedral, St Nicholas' Church, Newcastle before it was introduced to Scotland at St Giles'; the medieval St Mary-le-Bow, City of London, London, may also have possessed a crown steeple. Another crown steeple existed at St Michael's Parish Church, Linlithgow until 1821 and others may have been planned, and possibly begun, at the parish churches of St Mary's Collegiate Church, Haddington, Haddington and Dundee Parish Church (St Mary's), Dundee. These other examples are composed only of diagonal flying buttresses springing from the four corners of the tower; whereas the St Giles' steeple is unique among medieval crown steeples in being composed of eight buttresses: four springing from the corners and four springing from the centre of each side of the tower.MacGibbon and Ross 1896, ii p. 449.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 109.

For the arrival into Edinburgh of Anne of Denmark in 1590, 21 weather vanes were added to the crests of the steeple; these were removed prior to 1800 and replacements were installed in 2005. The steeple was repaired by John Mylne (died 1667), John Mylne the Younger in 1648. Mylne added pinnacles half-way up the crests of the buttresses; he is also largely responsible for the present appearance of the central pinnacle and may have rebuilt the tower's Tracery, traceried parapet.Hay 1976, p. 252. The Weather vane, weathercock atop the central pinnacle was created by Alexander Anderson in 1667; it replaced an earlier weathercock of 1567 by Alexander Honeyman.

Nave

The Pevsner Architectural Guides, ''Buildings of Scotland'' series calls the nave "archaeologically the most complicated part of church".Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 112. Though the nave dates to the 14th century and is one of the oldest parts of the church, it has been significantly altered and extended since.MacGibbon and Ross 1896, ii p. 420. The ceiling over the central section of the nave is a List of architectural vaults, tierceron vault in plaster; this was added during William Burn's restoration of 1829–1833. Burn also heightened the walls of the central section of the nave by 16 feet (4.8 metres), adding windows to create aNorth nave aisle and chapels

The ceiling of the north nave aisle is a rib vault in a similar style to the Albany Aisle: this suggests the north nave aisle dates to the same campaign of building at the turn of the 15th century.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 113.MacGibbon and Ross 1896, ii p. 426.RCAHMS 1951, p. 31. In the first decade of the 15th century, the Albany Aisle was erected as a northward extension of the two westernmost bays of the north nave aisle. The Aisle consists of two bays under a stone Rib vault, rib-vaulted ceiling. The west window of the chapel was blocked up during the Burn restoration of 1829–1833. The north wall of the Aisle contains a semi-circular tomb recess. The ceiling vaults are supported by a bundled pillar that supports a foliate Capital (architecture), capital and octagonal Abacus (architecture), abacus upon which are the Escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheons of the Aisle's donors: Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany andSouth nave aisles

The inner and outer south nave aisles were likely begun in the later 15th century around the time of the Preston Aisle, which they strongly resemble. They were likely completed by 1510, when altars of the Trinity, Holy Trinity, Saint Apollonia, and Thomas the Apostle, Saint Thomas were added to the west end of the inner aisle. The current aisles replaced the original south nave aisle and the five chapels by John Primrose, John Skuyer, and John of Perth, named in a contract of 1387. The inner aisle retains its original List of architectural vaults, quadripartite vault; however, the plaster List of architectural vaults, tierceron vault of the outer aisle (known as the Moray Aisle) dates to William Burn's restoration. During the Burn restoration, the two westernmost bays of the outer aisle were removed. There remains a prominent gap between the pillars of the missing bays and the 19th century wall. At the west end of the outer aisle, Burn added a new wall with a door and oriel window. Burn also replaced the window of the inner aisle with a smaller window, centred north of the original in order to accommodate a double Niche (architecture), niche on the exterior wall. The outline of the original window is still visible in the interior wall. In 1513, Alexander Lauder of Blyth commissioned an aisle of two bays at the eastern end of the outer south nave aisle: the Holy Blood Aisle is the easternmost and only surviving bay of this aisle.MacGibbon and Ross 1896, ii p. 441. It is named for the Confraternity of the Holy Blood, to whom it was granted upon completion in 1518. The western bay of the Aisle and the pillar separating the two bays were removed during the Burn restoration and the remainder was converted to a heating chamber. The Aisle was restored to ecclesiastical use under William Hay. An elaborate late Gothic tomb recess occupies the south wall of the aisle.Crossing and transepts

The Pier (architecture), piers of the crossing date to the original building campaign of the 14th century and may be the oldest part of the present church. The piers were likely raised around 1400, at which time the present vault and bell hole were created. The first stages of both transepts were likely completed by 1395, in which year the St John's Aisle was added to the north of the north transept. Initially, the north transept extended no further than the north wall of the aisles and possessed a Barrel vault, tunnel-vaulted ceiling at the same height as those in the crossing and aisles. The arches between the transept and north aisles of the choir and nave appear to be 14th century.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 111. The St John's Chapel, extending north of the line of the aisles, was added in 1395; in its western end was a Stairs#Spiral and helical stairs, turnpike stair, which, at the William Burn, Burn restoration, was re-set in the thick wall between the St Eloi Aisle and the north transept. The remains of St John's Chapel are visible in the east wall of the north transept: these include fragments of vaulting and a medieval window, which faces into the Chambers Aisle. The bottom half of this window's tracery, as far as its Battlement, embattled transom (architectural), transom, is original; curvilinear tracery was added to the upper half by MacGibbon and Ross in 1889–91. At the Burn restoration, the north transept was heightened and aChoir

The Pevsner Architectural Guides, ''Buildings of Scotland'' series calls the choir the "finest piece of late medieval parish church architecture in Scotland". The choir dates to two periods of building: one in the 14th century and one in the 15th. The archaeological excavations indicate the choir was extended to almost its current size in a single phase before the mid-15th-century work. The choir was initially built as a hall church: as such, it was unique in Scotland. The western three bays of the choir date to this initial period of construction. The arcades of these bays are supported by simple, octagonal pillars. In the middle of the 15th century, two Bay (architecture), bays were added to the east end of the choir and the central section was raised to create aChoir aisles

Of the two choir aisles, the north is only two thirds the width of the south aisle, which contained the Lady Chapel prior to the Reformation.Fawcett 1994, p. 187. Richard Fawcett suggests this indicates that both choir aisles were rebuilt after 1385. In both aisles, the curvature of the spandrels between the Rib vault, ribs gives the effect of a dome in each bay. The ribs appear to serve a structural purpose; however, the lack of any intersection between the lateral and longitudinal cells of each bay means that these vaults are effectively pointed barrel vaults.Hannah 1934, p. 159. Having been added as part of the mid-15th century extension, the eastern bays of both aisles contain proper lateral cells. The north wall of the north choir aisle contains a 15th-century tomb recess; in this wall, a Grotesque (architecture), grotesque, which may date to the 12th century church, has been re-set. At the east end of the south aisle is a stone staircase added by Bernard Feilden and Simpson & Brown in 1981–82. The Chambers Aisle stands north of the westernmost bay of the north choir aisle. This chapel was created in 1889–91 by MacGibbon and Ross as a memorial to William Chambers. This Aisle stands on the site of the medieval Sacristy, vestry, which, at the Reformation, was converted to the Town Clerk's office before being restored to its original use by William Burn. MacGibbon and Ross removed the wall between the vestry and the church and inserted a new arch and vaulted ceiling, both of which incorporate medieval masonry.Marshall 2009, p. 145. The Preston Aisle stands south of the western three bays of the south choir aisle. It is named for William Preston of Gorton, who donatedStained glass

St Giles' is glazed with 19th and 20th century stained glass by a diverse array of artists and manufacturers. Between 2001 and 2005, the church's stained glass was restored by the Stained Glass Design Partnership of Kilmaurs. Fragments of the medieval stained glass were discovered in the 1980s: none was obviously pictorial and some may have been grisaille. A pre-Reformation window depicting an elephant and the emblem of the Incorporated Trades of Edinburgh, Incorporation of Hammermen survived in the St Giles' Cathedral#St Eloi Aisle, St Eloi Aisle until the 19th century. References to the removal of the stained glass windows after the Reformation are unclear. A scheme of coloured glass was considered as early as 1830: three decades before the first new coloured glass in a Church of Scotland building was installed at Greyfriars Kirk in 1857; however, the plan was rejected by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council.Victorian windows

By the 1860s, attitudes to stained glass had liberalised within Scottish Presbyterianism and the insertion of new windows was a key component of William Chambers' plan to restore St Giles'. The firm of James Ballantine was commissioned to produce a sequence depicting the life of Jesus of Nazareth, Christ, as suggested by the artists Robert Herdman and Joseph Noel Paton. This sequence commences with a window of 1874 in the north choir aisle and climaxes in the great east window of 1877, depicting the Crucifixion of Jesus, Crucifixion and Ascension of Jesus, Ascension.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 116.

Other windows by Ballantine & Son are the Parable of the Prodigal Son, Prodigal Son window in the south wall of the south nave aisle; the west window of the Albany Aisle, depicting the Parable of the ten virgins, parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins and the Parable of the talents or minas, parable of the talents (1876); and the west window of the Preston Aisle, depicting Paul the Apostle, Saint Paul (1881).Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, pp. 116–117. Ballantine & Son are also responsible for the window of the Holy Blood Aisle, depicting the assassination and funeral of the James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray, Regent Moray (1881): this is the only window of the church that depicts events from Scottish history.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 117.Marshall 2009, p. 128.Kallus 2010, p. 19. Andrew Ballantine produced the west window in the south wall of the inner south nave aisle (1886): this depicts scenes from the life of Moses. The subsequent generation of the Ballantine firm, Ballantine & Gardiner, produced windows depicting the first Pentecost (1895) and Saint Peter (1895–1900) in the Preston Aisle; David and Jonathan (1 Samuel), Jonathan in the east window of the south side of the outer south nave aisle (1900–01); Joseph (Genesis), Joseph in the east window of the south wall of the inner south nave aisle (1898); and, in the windows of the Chambers Aisle, Solomon's construction of the Solomon's Temple, Temple (1892) and scenes from the life of John the Baptist (1894).

Multiple generations of the Ballantine firm executed Heraldry, heraldic windows in the oriel window of the outer south nave aisle (1883) and in the

By the 1860s, attitudes to stained glass had liberalised within Scottish Presbyterianism and the insertion of new windows was a key component of William Chambers' plan to restore St Giles'. The firm of James Ballantine was commissioned to produce a sequence depicting the life of Jesus of Nazareth, Christ, as suggested by the artists Robert Herdman and Joseph Noel Paton. This sequence commences with a window of 1874 in the north choir aisle and climaxes in the great east window of 1877, depicting the Crucifixion of Jesus, Crucifixion and Ascension of Jesus, Ascension.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 116.

Other windows by Ballantine & Son are the Parable of the Prodigal Son, Prodigal Son window in the south wall of the south nave aisle; the west window of the Albany Aisle, depicting the Parable of the ten virgins, parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins and the Parable of the talents or minas, parable of the talents (1876); and the west window of the Preston Aisle, depicting Paul the Apostle, Saint Paul (1881).Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, pp. 116–117. Ballantine & Son are also responsible for the window of the Holy Blood Aisle, depicting the assassination and funeral of the James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray, Regent Moray (1881): this is the only window of the church that depicts events from Scottish history.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 117.Marshall 2009, p. 128.Kallus 2010, p. 19. Andrew Ballantine produced the west window in the south wall of the inner south nave aisle (1886): this depicts scenes from the life of Moses. The subsequent generation of the Ballantine firm, Ballantine & Gardiner, produced windows depicting the first Pentecost (1895) and Saint Peter (1895–1900) in the Preston Aisle; David and Jonathan (1 Samuel), Jonathan in the east window of the south side of the outer south nave aisle (1900–01); Joseph (Genesis), Joseph in the east window of the south wall of the inner south nave aisle (1898); and, in the windows of the Chambers Aisle, Solomon's construction of the Solomon's Temple, Temple (1892) and scenes from the life of John the Baptist (1894).

Multiple generations of the Ballantine firm executed Heraldry, heraldic windows in the oriel window of the outer south nave aisle (1883) and in the 20th century windows

Oscar Paterson is responsible for the west window of the north side of the north nave aisle (1906): this shows saints associated with St Giles'. Karl Parsons designed the west window of the south side of the south choir aisle (1913): this depicts saints associated with Scotland. Douglas Strachan is responsible for the windows of the choir clerestory that depict saints (1932–35) and for the north transept window (1922): this shows Jesus walking on water, Christ walking on water and Calming the storm, stilling the Sea of Galilee, alongside golden angels subduing demons that represent the Anemoi, four winds of the earth.Kallus 2010, p. 23.

Windows of the later 20th century include a window in the north transept

Oscar Paterson is responsible for the west window of the north side of the north nave aisle (1906): this shows saints associated with St Giles'. Karl Parsons designed the west window of the south side of the south choir aisle (1913): this depicts saints associated with Scotland. Douglas Strachan is responsible for the windows of the choir clerestory that depict saints (1932–35) and for the north transept window (1922): this shows Jesus walking on water, Christ walking on water and Calming the storm, stilling the Sea of Galilee, alongside golden angels subduing demons that represent the Anemoi, four winds of the earth.Kallus 2010, p. 23.

Windows of the later 20th century include a window in the north transept Memorials

There are over a hundred memorials in St. Giles'; most date from the 19th century onwards.

In the medieval period, the floor of St Giles' was paved with memorial stones and brasses; these were gradually cleared after the Reformation.Marshall 2011, p. 1. At the William Burn, Burn restoration of 1829–1833, most post-Reformation memorials were destroyed; fragments were removed to Coulter, South Lanarkshire, Culter Mains and Swanston, Edinburgh, Swanston.RCAHMS 1951, p. 34.

The installation of memorials to notable Scots was an important component of William Chambers' plans to make St Giles' the "Westminster Abbey of Scotland". To this end, a management board was set up in 1880 to supervise the installation of new monuments; it continued in this function until 2000. All the memorials were conserved between 2008 and 2009.

There are over a hundred memorials in St. Giles'; most date from the 19th century onwards.

In the medieval period, the floor of St Giles' was paved with memorial stones and brasses; these were gradually cleared after the Reformation.Marshall 2011, p. 1. At the William Burn, Burn restoration of 1829–1833, most post-Reformation memorials were destroyed; fragments were removed to Coulter, South Lanarkshire, Culter Mains and Swanston, Edinburgh, Swanston.RCAHMS 1951, p. 34.

The installation of memorials to notable Scots was an important component of William Chambers' plans to make St Giles' the "Westminster Abbey of Scotland". To this end, a management board was set up in 1880 to supervise the installation of new monuments; it continued in this function until 2000. All the memorials were conserved between 2008 and 2009.

Ancient memorials

Medieval tomb recesses survive in the Preston Aisle, Holy Blood Aisle, Albany Aisle, and north choir aisle; alongside these, fragments of memorial stones have been re-incorporated into the east wall of the Preston Aisle: these include a memorial to "Johannes Touris de Innerleith" and a carving of the coat of arms of Edinburgh.

A memorial brass to the James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray, Regent Moray is situated on his monument in the Holy Blood Aisle. The plaque depicts female personifications of Justice and Religion flanking the Regent's coat of arms, arms and an inscription by George Buchanan. The plaque was inscribed by James Gray (goldsmith), James Gray on the rear of a fragment of a late 15th century memorial brass: a fibreglass replica of this side of the brass is installed on the opposite wall.Marshall 2011, p. 72. The plaque was originally set in a monument of 1570 by Murdoch Walker and John Ryotell: this was destroyed at the Burn restoration but the plaque was saved and reinstated in 1864, when John Stuart, 12th Earl of Moray commissioned David Cousin to design a replica of his ancestor's memorial.

A memorial tablet in the basement vestry commemorates John Stewart, 4th Earl of Atholl, who was buried in the Chepman Aisle in 1579. A commemorative plaque, plaque commemorating the Napier baronets, Napiers of Merchiston is located on the north exterior wall of the choir. This was likely installed on the south side of the church by Archibald Napier, 1st Lord Napier in 1637; it was moved to its present location during the Burn restoration.

Medieval tomb recesses survive in the Preston Aisle, Holy Blood Aisle, Albany Aisle, and north choir aisle; alongside these, fragments of memorial stones have been re-incorporated into the east wall of the Preston Aisle: these include a memorial to "Johannes Touris de Innerleith" and a carving of the coat of arms of Edinburgh.

A memorial brass to the James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray, Regent Moray is situated on his monument in the Holy Blood Aisle. The plaque depicts female personifications of Justice and Religion flanking the Regent's coat of arms, arms and an inscription by George Buchanan. The plaque was inscribed by James Gray (goldsmith), James Gray on the rear of a fragment of a late 15th century memorial brass: a fibreglass replica of this side of the brass is installed on the opposite wall.Marshall 2011, p. 72. The plaque was originally set in a monument of 1570 by Murdoch Walker and John Ryotell: this was destroyed at the Burn restoration but the plaque was saved and reinstated in 1864, when John Stuart, 12th Earl of Moray commissioned David Cousin to design a replica of his ancestor's memorial.

A memorial tablet in the basement vestry commemorates John Stewart, 4th Earl of Atholl, who was buried in the Chepman Aisle in 1579. A commemorative plaque, plaque commemorating the Napier baronets, Napiers of Merchiston is located on the north exterior wall of the choir. This was likely installed on the south side of the church by Archibald Napier, 1st Lord Napier in 1637; it was moved to its present location during the Burn restoration.

Victorian and Edwardian memorials

Most memorials installed between the William Burn, Burn restoration of 1829–1833 and the William Chambers (publisher), Chambers restoration of 1872–83 are now located in the north transept: these include white marble tablets commemorating Major General Robert Henry Dick (died 1846); Patrick Robertson, Lord Robertson (died 1855); and Aglionby Ross Carson (1856).Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 115. The largest of these memorials is a massive plaque surmounted by an urn designed by David Bryce to commemorate George Lorimer, Dean of Guild and hero of the 1865 Theatre Royal, Edinburgh, Theatre Royal fire (1867).

William Chambers, who funded the restoration of 1872–83, commissioned the memorial plaque to Walter Chepman in the Chepman Aisle (1879): this was designed by William Hay and produced by Francis Skidmore. Chambers himself is commemorated by a large plaque in a red marble frame (1894): located in the Chambers Aisle, this was designed by MacGibbon and Ross, David MacGibbon with the bronze plaque produced by Robert Inches, Hamilton and Inches. William Hay, the architect who oversaw the restoration (died 1888), is commemorated by a plaque in the north transept vestibule with a relief portrait by John Rhind (sculptor), John Rhind.

The first memorial installed after the Chambers restoration was a brass plaque dedicated to Dean James Hannay, the cleric whose reading of Charles I's Scottish Prayer Book in 1637 sparked rioting (1882). In response, and John Stuart Blackie and Robert Halliday Gunning supported a monument to Jenny Geddes, who, according to tradition, threw a stool at Hannay. An 1885 plaque on the floor between south nave aisles now marks the putative spot of Geddes' action. Other historical figures commemorated by plaques of this period include Agnes Keith, Countess of Moray (1893); Robert Leighton (bishop), Robert Leighton (1883); Gavin Douglas (1883); Alexander Henderson (theologian), Alexander Henderson (1883); William Carstares (1884); and John Craig (minister), John Craig (1883), and James Dalrymple, 1st Viscount Stair (1906).

The largest memorials of this period are the Jacobean architecture, Jacobean-style monuments to James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose in the Chepman Aisle (1888) and to his rival, Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll, in the St Eloi Aisle (1895); both are executed in alabaster and marble and take the form of aedicules in which lie life-size effigy, effigies of their dedicatees. The Montrose monument was designed by Robert Rowand Anderson and carved by John Rhind (sculptor), John and William Birnie Rhind. The Argyll monument, funded by Robert Halliday Gunning, was designed by Sydney Mitchell and carved by Charles McBride.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, pp. 115–116.

Other prominent memorials of this period include the Jacobean-style plaque on the south wall of the south choir aisle, commemorating John Inglis, Lord Glencorse and designed by Robert Rowand Anderson (1892); the memorial to Arthur Penrhyn Stanley (died 1881) in the Preston Aisle, including a relief portrait by Mary Grant (sculptor), Mary Grant; and the large bronze relief of Robert Louis Stevenson by Augustus Saint-Gaudens on the west wall of the Moray Aisle (1904). A life-size bronze statue of John Knox by James Pittendrigh MacGillivray (1906) stands in the north nave aisle. This initially stood in a Gothic Niche (architecture), niche in the east wall of the Albany Aisle; the niche was removed in 1951 and between 1965 and 1983, the statue stood outside the church, in Parliament Square.

William Chambers, who funded the restoration of 1872–83, commissioned the memorial plaque to Walter Chepman in the Chepman Aisle (1879): this was designed by William Hay and produced by Francis Skidmore. Chambers himself is commemorated by a large plaque in a red marble frame (1894): located in the Chambers Aisle, this was designed by MacGibbon and Ross, David MacGibbon with the bronze plaque produced by Robert Inches, Hamilton and Inches. William Hay, the architect who oversaw the restoration (died 1888), is commemorated by a plaque in the north transept vestibule with a relief portrait by John Rhind (sculptor), John Rhind.

The first memorial installed after the Chambers restoration was a brass plaque dedicated to Dean James Hannay, the cleric whose reading of Charles I's Scottish Prayer Book in 1637 sparked rioting (1882). In response, and John Stuart Blackie and Robert Halliday Gunning supported a monument to Jenny Geddes, who, according to tradition, threw a stool at Hannay. An 1885 plaque on the floor between south nave aisles now marks the putative spot of Geddes' action. Other historical figures commemorated by plaques of this period include Agnes Keith, Countess of Moray (1893); Robert Leighton (bishop), Robert Leighton (1883); Gavin Douglas (1883); Alexander Henderson (theologian), Alexander Henderson (1883); William Carstares (1884); and John Craig (minister), John Craig (1883), and James Dalrymple, 1st Viscount Stair (1906).

The largest memorials of this period are the Jacobean architecture, Jacobean-style monuments to James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose in the Chepman Aisle (1888) and to his rival, Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll, in the St Eloi Aisle (1895); both are executed in alabaster and marble and take the form of aedicules in which lie life-size effigy, effigies of their dedicatees. The Montrose monument was designed by Robert Rowand Anderson and carved by John Rhind (sculptor), John and William Birnie Rhind. The Argyll monument, funded by Robert Halliday Gunning, was designed by Sydney Mitchell and carved by Charles McBride.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, pp. 115–116.

Other prominent memorials of this period include the Jacobean-style plaque on the south wall of the south choir aisle, commemorating John Inglis, Lord Glencorse and designed by Robert Rowand Anderson (1892); the memorial to Arthur Penrhyn Stanley (died 1881) in the Preston Aisle, including a relief portrait by Mary Grant (sculptor), Mary Grant; and the large bronze relief of Robert Louis Stevenson by Augustus Saint-Gaudens on the west wall of the Moray Aisle (1904). A life-size bronze statue of John Knox by James Pittendrigh MacGillivray (1906) stands in the north nave aisle. This initially stood in a Gothic Niche (architecture), niche in the east wall of the Albany Aisle; the niche was removed in 1951 and between 1965 and 1983, the statue stood outside the church, in Parliament Square.

20th and 21st century memorials

In the north choir aisle, the bronze plaque commemorating Sophia Jex-Blake (died 1912) and the stone plaque to James Nicoll Ogilvie (1928) were designed by Robert Lorimer. Lorimer himself is commemorated by a large stone plaque in the Preston Aisle (1932): this was designed by Alexander Paterson. A number of plaques in the "Writers' Corner" in the Moray Aisle incorporate relief portraits of their dedicatees: these include memorials to Robert Fergusson (1927) and Margaret Oliphant (1908), sculpted by James Pittendrigh Macgillivray; John Brown (physician, born 1810), John Brown (1924), sculpted by Pilkington Jackson; and John Stuart Blackie (died 1895) and Thomas Chalmers (died 1847), designed by Robert Lorimer. Further relief portrait plaques commemorate Robert Inches (1922) in the former session house and William Alexander Smith (Boys' Brigade), William Smith (1929) in the Chambers Aisle; the former was sculpted by Henry Snell Gamley. Pilkington Jackson executed a pair of bronze relief portraits in pedimented Hopton Wood stone frames to commemorate Cameron Lees (1931) and Wallace Williamson (1936): these flank the entrance to the Thistle Chapel in the south choir aisle.Military memorials

Victorian

Victorian military memorials are concentrated at the west end of the church. The oldest military memorial is John Steell's memorial to members of the 78th (Highlanders) Regiment of Foot killed by disease in Sindh between 1844 and 1845 (1850): this white marble tablet contains a relief of a mourning woman and is located on the west wall of the nave. Nearby is the second-oldest military memorial, William Brodie (sculptor), William Brodie's Indian Rebellion of 1857 memorial for the 93rd (Sutherland Highlanders) Regiment of Foot (1864): this depicts, in white marble, two Highland soldiers flanking a tomb. John Rhind (sculptor), John Rhind sculpted the Royal Scots Greys' Mahdist War, Sudan memorial (1886): a large brass Celtic cross on grey marble. John Rhind and William Birnie Rhind sculpted the Highland Light Infantry's Second Boer War memorial: a marble-framed brass plaque. William Birnie Rhind and Thomas Duncan Rhind sculpted the Royal Scots 1st Battalion's Second Boer War memorial: a bronze relief within a pedimented marble frame (1903); WS Black designed the Royal Scots 3rd Battalion's Second Boer War memorial: a portrait marble plaque surmounted by an angel flanked by obelisks.

John Rhind (sculptor), John Rhind sculpted the Royal Scots Greys' Mahdist War, Sudan memorial (1886): a large brass Celtic cross on grey marble. John Rhind and William Birnie Rhind sculpted the Highland Light Infantry's Second Boer War memorial: a marble-framed brass plaque. William Birnie Rhind and Thomas Duncan Rhind sculpted the Royal Scots 1st Battalion's Second Boer War memorial: a bronze relief within a pedimented marble frame (1903); WS Black designed the Royal Scots 3rd Battalion's Second Boer War memorial: a portrait marble plaque surmounted by an angel flanked by obelisks.

World Wars

The Elsie Inglis memorial in the north choir aisle was designed by Frank Mears and sculpted in rose-tinted French stone and slate by Pilkington Jackson (1922): it depicts the angels of 1 Corinthians 13, Faith, Hope, and Love. Jackson also executed the Royal Scots 5th Battalion's Gallipoli Campaign memorial – bronze with a marble tablet (1921) – and the McCrae's Battalion, 16th (McCrae's) Battalion's First World War memorial, showing Saint Michael and sculpted in Portland stone: this was designed by Robert Lorimer, who also designed the bronze memorial plaque to the Royal Army Medical Corps in the north choir aisle. Individual victims of the war commemorated in St Giles' include Neil Primrose (politician), Neil Primrose (1918) and Sir Robert Arbuthnot, 4th Baronet (1917). Ministers and students of the Church of Scotland and United Free Church of Scotland are commemorated by a large oak panel at the east end of the north nave aisle by Messrs Begg and Lorne Campbell (1920).

Henry Snell Gamley is responsible for the congregation's First World War memorial (1926): located in the Albany Aisle, this consists of a large bronze relief of an angel crowning the "spirit of a soldier", its green marble tablet names the 99 members of the congregation killed in the conflict. Gamley is also responsible for the nearby white marble and bronze tablet to Scottish soldiers killed in France (1920); the Royal Scots 9th Battalion's white marble memorial in the south nave aisle (1921); and the bronze relief portrait memorial to Edward Maxwell Salvesen in the north choir aisle (1918).

The names of 38 members of the congregation killed in the Second World War are inscribed on tablets designed by Esmé Gordon within a medieval tomb recess in the Albany Aisle: these were unveiled at the dedication of the Albany Aisle as a war memorial chapel in 1951. As part of this memorial, a cross with panels by Elizabeth Dempster was mounted on the east wall of the Aisle. Other notable memorials of the Second World War include Basil Spence's large wooden plaque to the 94th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery, 94th (City of Edinburgh) Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery (1954) in the north choir aisle and the nearby Church of Scotland chaplains memorial (1950): this depicts Andrew the Apostle, Saint Andrew in bronze relief and was manufactured by Charles Henshaw.

The Elsie Inglis memorial in the north choir aisle was designed by Frank Mears and sculpted in rose-tinted French stone and slate by Pilkington Jackson (1922): it depicts the angels of 1 Corinthians 13, Faith, Hope, and Love. Jackson also executed the Royal Scots 5th Battalion's Gallipoli Campaign memorial – bronze with a marble tablet (1921) – and the McCrae's Battalion, 16th (McCrae's) Battalion's First World War memorial, showing Saint Michael and sculpted in Portland stone: this was designed by Robert Lorimer, who also designed the bronze memorial plaque to the Royal Army Medical Corps in the north choir aisle. Individual victims of the war commemorated in St Giles' include Neil Primrose (politician), Neil Primrose (1918) and Sir Robert Arbuthnot, 4th Baronet (1917). Ministers and students of the Church of Scotland and United Free Church of Scotland are commemorated by a large oak panel at the east end of the north nave aisle by Messrs Begg and Lorne Campbell (1920).

Henry Snell Gamley is responsible for the congregation's First World War memorial (1926): located in the Albany Aisle, this consists of a large bronze relief of an angel crowning the "spirit of a soldier", its green marble tablet names the 99 members of the congregation killed in the conflict. Gamley is also responsible for the nearby white marble and bronze tablet to Scottish soldiers killed in France (1920); the Royal Scots 9th Battalion's white marble memorial in the south nave aisle (1921); and the bronze relief portrait memorial to Edward Maxwell Salvesen in the north choir aisle (1918).

The names of 38 members of the congregation killed in the Second World War are inscribed on tablets designed by Esmé Gordon within a medieval tomb recess in the Albany Aisle: these were unveiled at the dedication of the Albany Aisle as a war memorial chapel in 1951. As part of this memorial, a cross with panels by Elizabeth Dempster was mounted on the east wall of the Aisle. Other notable memorials of the Second World War include Basil Spence's large wooden plaque to the 94th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery, 94th (City of Edinburgh) Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery (1954) in the north choir aisle and the nearby Church of Scotland chaplains memorial (1950): this depicts Andrew the Apostle, Saint Andrew in bronze relief and was manufactured by Charles Henshaw.

Features

Prior to the Reformation, St Giles' was furnished with as many as fifty stone subsidiary altars, each with their own furnishings and plate. The Dean of Guild's accounts from the 16th century also indicate the church possessed an Easter sepulchre, sacrament house, rood loft, lectern, pulpit, wooden chandeliers, and Choir (architecture)#Seating, choir stalls.RCAHMS 1951, p. 28. On 16 December 1558 the goldsmith James Mosman (goldsmith), James Mosman weighed and valued the treasures of St Giles' including the reliquary of the saint's arm bone with a diamond ring on his finger, a silver cross, and a ship for incense. At the Reformation, the interior was stripped and a new pulpit at the east side of the crossing became the church's focal point. Seating was installed for children and the burgh's council and trade guilds and a stool of penitence was added. After the Reformation, St Giles' was gradually partitioned into smaller churches. At the church's restoration by William Hay in 1872–83, the last post-Reformation internal partitions were removed and the church was oriented to face the communion table at the east end; the nave was furnished with chairs and the choir with stalls; a low railing separated the nave from the choir. The Pevsner Architectural Guides, ''Buildings of Scotland'' series described this arrangement as "High Presbyterian (Low church, Low Anglican)". Most of the church's furnishings date from this restoration onwards. From 1982, the church was reoriented with seats in the choir and nave facing a central communion table under the crossing.Furniture

Pulpits, tables, and font

The pulpit dates to 1883 and was carved in Caen stone and green marble by John Rhind (sculptor), John Rhind to a design by William Hay. The pulpit is octagonal with relief panels depicting the acts of mercy. An octagonal oak pulpit of 1888 with a tall steepled Canopy (building), canopy stands in the Moray Aisle: this was designed by Robert Rowand Anderson. St Giles' possessed a wooden pulpit prior to the Reformation. In April 1560, this was replaced with a wooden pulpit with two locking doors, likely located at the east side of the crossing; a lectern was also installed. A brass eagle lectern stands on the south side of the crossing: this was given by an anonymous couple for use in the Moray Aisle.Marshall 2009, p. 183. The bronze lectern steps were sculpted by Jacqueline Gruber Steiger and donated in 1991 by the Normandy Veterans' Association.Marshall 2009, p. 188. Until 1982, a Caen stone lectern, designed by William Hay stood opposite the pulpit at the west end of the choir.Marshall 2009, p. 124. Situated in the crossing, the communion table is a Carrara marble block unveiled in 2011: it was donated by Roger Lindsay and designed by Luke Hughes. This replaced a wooden table in use since 1982. The plain communion table used after the William Chambers (publisher), Chambers restoration was donated to the West Parish Church of Stirling in 1910 and replaced by an oak communion table designed by Robert Lorimer and executed by Nathaniel Grieve. The table displays painted carvings of the Lamb of God,Seating

Since 2003, new chairs, many of which bear small brass plaques naming donors, have replaced chairs of the 1880s by West and Collier throughout the church. Two banks of Choir (architecture)#Seating, choir stalls in a semi-circular arrangement occupy the south transept; these were installed by Whytock & Reid in 1984. Whytock & Reid also provided box pews for the nave in 1985; these have since been removed. In 1552, prior to the Reformation, Andrew Mansioun executed the south bank of Choir (architecture)#Seating, choir stalls; the north bank were likely imported. In 1559, at the outset of the Scottish Reformation, these were removed to the Tolbooth for safe-keeping; they may have been re-used to furnish the church after the Reformation. There has been a royal loft or pew in St Giles' since the regency of Mary of Guise. Standing between the south choir aisle and Preston Aisle, the current monarch's seat possess a tall back and canopy, on which stand the royal arms of Scotland; this oak seat and desk were created in 1953 to designs of Esmé Gordon and incorporate elements of the former royal pew of 1885 by William Hay. Hay's royal pew stood in the Preston Aisle; it replaced an oak royal pew of 1873, also designed by Hay and executed by John Taylor & Son: this was re-purposed as an internal west porch and was removed in 2008.

There has been a royal loft or pew in St Giles' since the regency of Mary of Guise. Standing between the south choir aisle and Preston Aisle, the current monarch's seat possess a tall back and canopy, on which stand the royal arms of Scotland; this oak seat and desk were created in 1953 to designs of Esmé Gordon and incorporate elements of the former royal pew of 1885 by William Hay. Hay's royal pew stood in the Preston Aisle; it replaced an oak royal pew of 1873, also designed by Hay and executed by John Taylor & Son: this was re-purposed as an internal west porch and was removed in 2008.

Metalwork, lighting, and plate

The gates and railings of the Albany Aisle, the St Eloi Aisle, the Holy Blood Aisle, and the Chepman Aisle are the work of Francis Skidmore and date from the Chambers restoration. Skidmore also produced the chancel railing – now removed – and the iron screens at the east end of the north choir aisle: these originally surrounded the Moray Aisle.Marshall 2009, p. 177. The gates and font bracket in the Chambers Aisle are by Thomas Hadden and date from the aisle's designation as the Chapel of Youth in 1927–29. The west door is surrounded by a metal and blue glass screen of 2008 by Leifur Breiðfjörð. The church is lit by stainless steel and aluminium chandeliers as well as by concealed strip lights below the windows. The chandeliers are designed to evoke Lily, lilies and were produced between 2007 and 2008 by Lighting Design Partnership near Edinburgh; they replaced a concealed lighting system of 1958. In 1882, during the William Chambers (publisher), Chambers restoration, Francis Skidmore provided a set of gas chandeliers based on a chandelier in St Mary Redcliffe, Bristol.Marshall 2009, p. 136. Electric lighting was installed in 1911 and Robert Lorimer designed new electric chandeliers; at their removal in 1958, some of these were donated to St John's Kirk, Perth, Scotland, Perth and Cleish Church. A red glass "Lamp of Remembrance" by Thomas Hadden hangs in the Albany Aisle: its steel frame imitates St Giles' crown steeple. A lamp with stained glass panels by Douglas Strachan hangs in the Chambers Aisle. Plate in possession of the church includes four communion cups dated 1643 and two flagons dated 1618 and given by George Montaigne, then Bishop of Lincoln. Among the church's silver are two plates dated 1643 and a Pitcher (container), ewer dated 1609.Clocks and bells

The current clock was manufactured by James Ritchie & Son and installed in 1911; this replaced a clock of 1721 by Langley Bradley of London, which is now housed in the Museum of Edinburgh. A clock is recorded in 1491. Between 1585 and 1721, the former clock of Lindores Abbey was used in St Giles'. The hour bell of the cathedral was cast in 1846 by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, possibly from the metal of the medieval Great Bell, which had been taken down about 1774. The Great Bell was cast in Flanders in 1460 by John and William Hoerhen and bore the Coat of arms, arms of Guelderland and an image of the Madonna (art), Virgin and Child. Robert Maxwell cast the second bell in 1706 and the third in 1728: these chime the Quarter bells, quarters, the latter bears the coat of arms of Edinburgh. Between 1700 and 1890, a carillon of 23 bells, manufactured in 1698 and 1699 by John Meikle, hung in the tower. Daniel Defoe, who visited Edinburgh in 1727, praised the bells but added "they are heard much better at a distance than near at hand". In 1955, an anonymous Presbyterian polity#Elder, elder donated one of the carillon's bells: it hangs in a Gothic wooden frame next to the Chambers Aisle.Marshall 2009, p. 100. Nearby hangs the bell of : this was presented in 1955 by the British Admiralty, Admiralty to mark the ship's connection to Edinburgh. The bell hangs in a frame topped by a naval crown: this was made from ''Howe''s deck timbers. The Vespers, vesper bell of 1464 stands in the south nave aisle.

The hour bell of the cathedral was cast in 1846 by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, possibly from the metal of the medieval Great Bell, which had been taken down about 1774. The Great Bell was cast in Flanders in 1460 by John and William Hoerhen and bore the Coat of arms, arms of Guelderland and an image of the Madonna (art), Virgin and Child. Robert Maxwell cast the second bell in 1706 and the third in 1728: these chime the Quarter bells, quarters, the latter bears the coat of arms of Edinburgh. Between 1700 and 1890, a carillon of 23 bells, manufactured in 1698 and 1699 by John Meikle, hung in the tower. Daniel Defoe, who visited Edinburgh in 1727, praised the bells but added "they are heard much better at a distance than near at hand". In 1955, an anonymous Presbyterian polity#Elder, elder donated one of the carillon's bells: it hangs in a Gothic wooden frame next to the Chambers Aisle.Marshall 2009, p. 100. Nearby hangs the bell of : this was presented in 1955 by the British Admiralty, Admiralty to mark the ship's connection to Edinburgh. The bell hangs in a frame topped by a naval crown: this was made from ''Howe''s deck timbers. The Vespers, vesper bell of 1464 stands in the south nave aisle.

Flags and heraldry

From 1883, Regulation Colours, regimental colours were hung in the nave. In 1982, the Scottish Command of the British Army offered to catalogue and preserve the colours. The colours were removed from the nave and 29 were reinstated in the Moray Aisle. Since 1953, the banners of the current Order of the Thistle, Knights of the Thistle have hung in the Preston Aisle, near the entrance to the Thistle Chapel. The banner of Douglas Haig hangs in the Chambers Aisle; this was donated in 1928 by Lady Haig after her husband's lying-in-state in St Giles'. A large wooden panel, showing the Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom, arms of George II of Great Britain, George II hangs on the tower wall above at the west end of the choir: this is dated 1736 and was painted by Roderick Chalmers. The Fetternear Banner, the only surviving religious banner from pre- Reformation Scotland, was made around 1520 for the Confraternity of the Holy Blood, which had its altar in the Lauder Aisle. The banner, which depicts the wounded Jesus of Nazareth, Christ and the Arma Christi, instruments of His passion, is held by the National Museum of Scotland.National Covenant

St Giles' possesses one of the original copies of Scotland's Covenanters, National Covenant of 1638. The copy in St Giles' was signed by leadingThistle Chapel

Located at the south-east corner of St Giles', the Thistle Chapel is the chapel of the

Located at the south-east corner of St Giles', the Thistle Chapel is the chapel of the Worship

Services and liturgy

St Giles' holds three services every Sunday: * 9.30 am: Morning Service - Choir, Sermon, Eucharist, Holy Communion * 11.00 am: Morning Service - Choir, Sermon * 6 pm: St Giles' At Six - Programme of Music Every weekday a service is held at 12 noon. Sunday morning service is also live-streamed from the St Giles' Cathedral YouTube channel. Prior to the Reformation, St Giles' used the Sarum Use, with Solemn Mass, High Mass being celebrated at the High Altar and Low Mass celebrated at the subsidiary altars. After the Reformation, services were conducted according to the Book of Common Order; unaccompanied congregation singing of the Psalms replaced choral and organ music and preaching replaced the Mass as the central focus of worship; public penance was also introduced. Eucharist, Communion services were initially held three times a year; the congregation sat around trestle tables: a practice that continued until the 1870s. The attempted replacement of the Book of Common Order by a Scottish version of the Book of Common Prayer on 23 July 1637 sparked rioting, which led to the signing of the Covenanters, National Covenant. From 1646, the Directory for Public Worship was used. During the Commonwealth of England, Commonwealth, the Directory fell out of use; public penance, psalm-singing, and Bible readings were removed from the service and laity, lay preaching was introduced. Between 1648 and 1655, the ministers withheld communion in protest. During the second imposition of episcopacy under Charles II of England, Charles II and James II of England, James VII the liturgy reverted to its post-Reformation form and there was no attempt to bring it into line with the practice of the Church of England. By the beginning of the 18th century, the services of the Book of Common Order had been replaced by extempore prayers. Cameron Lees, minister between 1877 and 1911, was a leading figure in the liturgical revival among Scottish Presbyterian churches in the latter half of the 19th century. Lees used the Church Service Society's ''Euchologion'' for communion services and compiled the ''St Giles' Book of Common Order'': this directed daily and Sunday services between 1884 and 1926. Under Lees, Christmas, Easter, and Watchnight services were introduced. With financial support from John Ritchie Findlay, daily service was also introduced for the first time since the Commonwealth of England, Commonwealth. Lees' successor, Andrew Wallace Williamson continued this revival and revised the ''St Giles' Book of Common Order''. A weekly communion service was introduced by Williamson's successor, Charles Warr. The current pattern of four Sunday services, including two communions, was adopted in 1983 during the incumbency of Gilleasbuig Macmillan. Macmillan introduced a number of changes to communion services, including the practice of communicants' gathering round the central communion table and passing elements to each other.Notable services

Since the medieval period, St Giles' has hosted regular and occasional services of civic and national significance. Important annual services held in St Giles include the Edinburgh's civic Remembrance Sunday service, the Kirking of the council for the Edinburgh City Council, city council, the Kirking of the Courts for the legal profession, the Thistle Service for the Order of the Thistle, Knights of the Thistle; and a service during the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. The Kirking of the Parliament has been held in St Giles' at the opening of every new session of the Scottish Parliament since the Parliament's foundation in 1999; this revives an earlier service for the Parliament of Scotland.

St Giles' has also long enjoyed a close connection with the Scottish then British royal families; the royal Order of the Thistle, Knights of Thistle, including Elizabeth II, the Queen as Sovereign of the Order, attend the Thistle service in St Giles' every second year. Since the regency of Mary of Guise, there has been a royal pew or loft in St Giles'. Notable services for the royal family include the Requiem, Requiem Mass for James I of Scotland, James I (1437); the service to welcome Anne of Denmark to Scotland (1590); divine service during the Visit of King George IV to Scotland, visit of George IV (1822); and Elizabeth II's receipt of the Honours of Scotland (1953).

Significant occasional services in St Giles' include the memorial Mass for the dead of Battle of Flodden, Flodden (1513); thanksgivings for the Scottish Reformation (1560), the Acts of Union 1707, Union (1707), and Victory in Europe Day (1945); and the service to mark the opening of the first Edinburgh International Festival (1947).Marshall 2009, p. 191. Recent occasional services have marked the return to Scotland of the Stone of Scone (1996) and the opening of the National Museum of Scotland (1998); a service of reconciliation after the 2014 Scottish independence referendum was also held in St Giles'.

St Giles' hosted the lyings-in-state of Elsie Inglis (1917) and Douglas Haig (1928). Notable recent funerals include those of Robin Cook (2005) and John Bellany (2013). Notable recent weddings include the marriage of Chris Hoy to Sarra Kemp (2010).

Since the medieval period, St Giles' has hosted regular and occasional services of civic and national significance. Important annual services held in St Giles include the Edinburgh's civic Remembrance Sunday service, the Kirking of the council for the Edinburgh City Council, city council, the Kirking of the Courts for the legal profession, the Thistle Service for the Order of the Thistle, Knights of the Thistle; and a service during the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. The Kirking of the Parliament has been held in St Giles' at the opening of every new session of the Scottish Parliament since the Parliament's foundation in 1999; this revives an earlier service for the Parliament of Scotland.

St Giles' has also long enjoyed a close connection with the Scottish then British royal families; the royal Order of the Thistle, Knights of Thistle, including Elizabeth II, the Queen as Sovereign of the Order, attend the Thistle service in St Giles' every second year. Since the regency of Mary of Guise, there has been a royal pew or loft in St Giles'. Notable services for the royal family include the Requiem, Requiem Mass for James I of Scotland, James I (1437); the service to welcome Anne of Denmark to Scotland (1590); divine service during the Visit of King George IV to Scotland, visit of George IV (1822); and Elizabeth II's receipt of the Honours of Scotland (1953).