Spiro Gulabchev on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Spiro Konstantinov Gulabchev (12 June 1856 – January 1918) was a Bulgarian anarchist known for leading the '' siromahomilstvo'' movement, a Bulgarian

Spiro Gulabchev was born on 12 June 1856 in

Spiro Gulabchev was born on 12 June 1856 in

Gulabchev and his father nevertheless experienced financial trouble during this period, which threatened Gulabchev's ability to complete his course. Eventually, Gulabchev wrote a letter to Joseph I of Bulgaria in which he asked for financial assistance for his father, so that he may afford to complete his education.

While studying in Kiev, Gulabchev was exposed to the

Gulabchev and his father nevertheless experienced financial trouble during this period, which threatened Gulabchev's ability to complete his course. Eventually, Gulabchev wrote a letter to Joseph I of Bulgaria in which he asked for financial assistance for his father, so that he may afford to complete his education.

While studying in Kiev, Gulabchev was exposed to the

left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

, populist, and Russian nihilist movement that sought to create a society which protected the poorest among them. An avid opponent of inequality, and holding communitarian

Communitarianism is a philosophy that emphasizes the connection between the individual and the community. Its overriding philosophy is based upon the belief that a person's social identity and personality are largely molded by community relati ...

beliefs, Gulabchev organized educational associations and activities for the poor in multiple towns as clubs and libraries, through which he actively advocated for revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

ary action. In late 1880s, the ''siromakhomilstvo'' split between anarchism and socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

, with Gulabchev advocating for the former. In 1892, he formed an anarchist study group in Ruse

Ruse may refer to:

Places

*Ruse, Bulgaria, a major city of Bulgaria

**Ruse Municipality

** Ruse Province

** 19th MMC – Ruse, a constituency

*Ruše, a town and municipality in north-eastern Slovenia

* Ruše, Žalec, a small settlement in east-ce ...

.

Early life

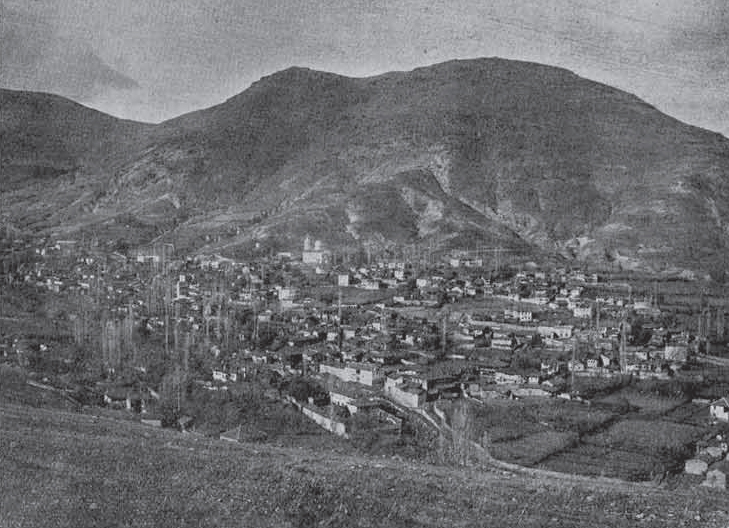

Lerin

Florina ( el, Φλώρινα, ''Flórina''; known also by some alternative names) is a town and municipality in the mountainous northwestern Macedonia, Greece. Its motto is, 'Where Greece begins'.

The town of Florina is the capital of the ...

, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, to Catherine Gulabchev and Konstantin, a priest who was active in the Bulgarian Revival movement and headed a church of the Bulgarian Exarchate

The Bulgarian Exarchate ( bg, Българска екзархия, Balgarska ekzarhiya; tr, Bulgar Eksarhlığı) was the official name of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church before its autocephaly was recognized by the Ecumenical See in 1945 and th ...

in Lerin. He was educated at a primary and secondary level in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, Edirne, and Plovdiv

Plovdiv ( bg, Пловдив, ), is the second-largest city in Bulgaria, standing on the banks of the Maritsa river in the historical region of Thrace. It has a population of 346,893 and 675,000 in the greater metropolitan area. Plovdiv is the c ...

, throughout which his peers included Dimitar Blagoev

Dimitar Blagoev Nikolov (, mk, Димитар Благоев Николов; 14 June 1856 – 7 May 1924) was a Bulgarian political leader and philosopher. He was the founder of the Bulgarian left-wing political movement and of the first social- ...

, whom Gulabchev would later oppose.

In 1870 Gulabchev found work as a teacher in the village of Gorno Nevolyani, where he introduced the monitorial system The Monitorial System, also known as Madras System or Lancasterian System, was an education method that took hold during the early 19th century, because of Spanish, French, and English colonial education that was imposed into the areas of expansion. ...

of education. He initially taught in both Greek and Bulgarian but, by his second year, had begun to teach entirely in Bulgarian, providing his students with Bulgarian textbooks and teaching them to read and write.

Gulabchev was a favourite of both students and parents, but as news began to spread of his father's schismatic

Schismatic may refer to:

* Schismatic (religion), a member of a religious schism, or, as an adjective, of or pertaining to a schism

* a term related to the Covenanters, a Scottish Presbyterian movement in the 17th century

* pertaining to the schi ...

leanings (and as the Bulgarian Schism was reaching its climax), Gulabchev was pushed out of Gorno Nevolyani. In autumn of 1871 he left for Plovdiv to see a relative, Panaret Plovdivski.

University and political radicalisation

In 1877 Gulabchev traveled to theRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, where he enrolled at the Moscow Theological Academy and studied for two years before transferring to Moscow State University to study law. Before completing the course, however, he once again transferred in 1881, this time to study philology

Philology () is the study of language in oral and writing, written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defin ...

at the Faculty of History and Philology at Kiev University. His study was funded through scholarships and grants provided by Eastern Rumelia (and then by the Principality of Bulgaria

The Principality of Bulgaria ( bg, Княжество България, Knyazhestvo Balgariya) was a vassal state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. It was established by the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

After the Russo-Turkish War ende ...

following Bulgaria's unification in 1885). Gulabchev and his father nevertheless experienced financial trouble during this period, which threatened Gulabchev's ability to complete his course. Eventually, Gulabchev wrote a letter to Joseph I of Bulgaria in which he asked for financial assistance for his father, so that he may afford to complete his education.

While studying in Kiev, Gulabchev was exposed to the

Gulabchev and his father nevertheless experienced financial trouble during this period, which threatened Gulabchev's ability to complete his course. Eventually, Gulabchev wrote a letter to Joseph I of Bulgaria in which he asked for financial assistance for his father, so that he may afford to complete his education.

While studying in Kiev, Gulabchev was exposed to the agrarian socialist

Agrarian socialism is a political ideology that promotes “the equal distribution of landed resources among collectivized peasant villages” This socialist system places agriculture at the center of the economy instead of the industrialization ...

and populist movements that had begun to emerge within the Russian intelligentsia; in particular, he came under the influence of the ideas of "popular enlightenment" proposed by the Narodniks and the conspiratorial

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

*

*

* The term has a nega ...

revolutionary socialist

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revoluti ...

methods of Narodnaya Volya. He was also impressed by the liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

values of the Enlightenment and the federalist

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

beliefs of the Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

academic Mykhailo Drahomanov. Gulabchev came to believe that in order to build a socially just society, populist ideas would have to be spread through a "book" movement in the Balkans; specifically, he focused his attention on the Bulgarian student diaspora, working to establish a network of "readers' friendly societies", which he also called "readers' fellowships" or simply "fellowships". Gulabchev planned to spread such fellowships internationally, covering all countries with a Bulgarian student population, with these fellowships being subordinate to a central fellowship in Kiev. He hoped that these cohesive student groups would produce propaganda when they returned to Bulgaria.

The first of these fellowships, which Gulabchev personally coordinated with students returning to Bulgaria to see family, appeared in Ruse

Ruse may refer to:

Places

*Ruse, Bulgaria, a major city of Bulgaria

**Ruse Municipality

** Ruse Province

** 19th MMC – Ruse, a constituency

*Ruše, a town and municipality in north-eastern Slovenia

* Ruše, Žalec, a small settlement in east-ce ...

, Silistra

Silistra ( bg, Силистра ; tr, Silistre; ro, Silistra) is a town in Northeastern Bulgaria. The town lies on the southern bank of the lower Danube river, and is also the part of the Romanian border where it stops following the Danube. Sil ...

, Veliko Tarnovo

Veliko Tarnovo ( bg, Велико Търново, Veliko Tărnovo, ; "Great Tarnovo") is a town in north central Bulgaria and the administrative centre of Veliko Tarnovo Province.

Often referred as the "''City of the Tsars''", Veliko Tarnovo ...

, Varna

Varna may refer to:

Places Europe

*Varna, Bulgaria, a city in Bulgaria

**Varna Province

**Varna Municipality

** Gulf of Varna

**Lake Varna

**Varna Necropolis

*Vahrn, or Varna, a municipality in Italy

*Varniai, a city in Lithuania

* Varna (Šaba ...

, and Anhialo. In practice, these fellowships were generally composed of 5 – 10 members who distributed literature, maintained book collections, wrote magazine/newspaper articles, and translated foreign publications into Bulgarian. Their creation was funded by Gulabchev, after which they were maintained by membership fees (a portion of which went to the central fellowship in Kiev) and donations from wealthy patrons.

The fellowships became more structured as time passed. In 1882 Gulabchev designed a constitution for the network and began to carefully select the members of future fellowships, acting as a secret society

A secret society is a club or an organization whose activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence a ...

similar to Narodnaya Volya. In 1883 he established a student society at Kiev University called the "Friendly Society for the Promotion of Bulgarianness in Macedonia".

Return to Bulgaria and the siromakhomilstvo movement

By 1884 Gulabchev had become known to the Special Corps of Gendarmes and was, according to state documents, interrogated as a witness "due to a close acquaintance with a person who is extremely unreliable in political terms". He nevertheless continued his political activities; on 5 February 1886, while disembarking the Russian ship ''Azov'' inConstantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, Gulabchev was found by Russian Empire customs to be smuggling 37 publications that were considered "revolutionary" in nature. Officials imprisoned him in Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

. Throughout interrogations he refused to reveal suppliers or transportation chains, maintaining that he had bought the literature cheaply in Sofia

Sofia ( ; bg, София, Sofiya, ) is the capital and largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain in the western parts of the country. The city is built west of the Iskar river, and ha ...

for personal use. He was soon after expelled from Kiev University, but the state prosecutor was hesitant to bring a foreign citizen to trial.

The case began to appear in Bulgarian newspapers, with articles stating that the Bulgarian student was under threat of being exiled to Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

; following intervention by the Bulgarian Exarchate and government it was eventually decided to instead deport Gulabchev to Bulgaria. By mid to late 1886 he had been released.

Undeterred, he continued to be active in politics. He began teaching at Gabrovo School in January 1887, where he found himself in a socialist environment. Here, he organized a secret circle which eventually culminated in an 1888 student revolt; Gulabchev planned that the students would distribute a propaganda pamphlet after it was quelled, but this never materialized. He was afterwards transferred to First Boy's Public School in Varna, where he had established the "Kapka" educational society the year before. By 1889 he was teaching in Veliko Tarnovo.

While he taught, Gulabchev continued to develop the political ideas he had been influenced by in Russia. His "readers' fellowships" continued to appear throughout Bulgarian cities and began attempts to build a more cohesive ideology; Gulabchev grew a movement, the ''siromakhomilstvo'', around the belief that the poorest (''siromasi'') ought to be protected and shown love and mercy – contemporary Bulgarian histiography described the movement as a populist and Russian nihilist movement. The ''siromakhomilstvo'' condemned social inequalities and actively advocated for revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

ary action among the poor through events organised in clubs and libraries. Like many similar movements throughout the period, Gulabchev decried luxury, fashion, and other aesthetic focuses on the grounds that they were an affront to the poor. For similar reasons, he criticized government spending on higher education while the majority didn't have access to secondary education, but also emphasised the importance of solidarity between the intelligentsia and the impoverished. He employed populist techniques to demonstrate this solidarity, such as forbidding his immediate followers from wearing ties, which he felt were a symbol of alienation between the intellectual class and the common people.

''Siromakhomilstvo'' groups communicated through cipher

In cryptography, a cipher (or cypher) is an algorithm for performing encryption or decryption—a series of well-defined steps that can be followed as a procedure. An alternative, less common term is ''encipherment''. To encipher or encode i ...

s after 1891, which had become popular among socialist organisations.

Gulabchev's image of an ideal future, which he referred to as 'primitively-communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

', struggled to gain significant attention outside of the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the in ...

; by the late 1880s the ''siromakhomilstvo'' movement split off into anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

, state socialist

State socialism is a political and economic ideology within the socialist movement that advocates state ownership of the means of production. This is intended either as a temporary measure, or as a characteristic of socialism in the transition f ...

, and Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

movements, with Gulabchev supporting anarchism.

In 1892 he founded the first anarchist group in Ruse

Ruse may refer to:

Places

*Ruse, Bulgaria, a major city of Bulgaria

**Ruse Municipality

** Ruse Province

** 19th MMC – Ruse, a constituency

*Ruše, a town and municipality in north-eastern Slovenia

* Ruše, Žalec, a small settlement in east-ce ...

, where members studied the works of Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activis ...

. In response to a 1909 international anarchist congress, Gulabchev was involved in an unsuccessful campaign to organise anarchist groups in Bulgaria on a national level.

Footnotes

Citations

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gulabchev, Spiro 1852 births 1918 deaths Bulgarian anarchists