Speeches By Martin Luther King Jr on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

This list of speeches includes those that have gained

This list of speeches includes those that have gained

*44 BC: The Funeral Oration of Roman Dictator, Julius Caesar, delivered by Mark Antony after his assassination; rephrased by William Shakespeare.

*44 BC: The Funeral Oration of Roman Dictator, Julius Caesar, delivered by Mark Antony after his assassination; rephrased by William Shakespeare.

*1521: The Here I Stand speech of

*1521: The Here I Stand speech of

*1862: The Blood and Iron speech by Prussian

*1862: The Blood and Iron speech by Prussian

Transcript.

*1940: The

*1946: The First Bayeux speech, delivered by General

*1946: The First Bayeux speech, delivered by General

Transcript.

*2002:

Transcript

Video.

*2005: The

Transcript

Video.

*2008: A More Perfect Union, in which U.S. Presidential candidate

Transcript

Video.

*2015:

Transcript

*2022:

"Great Speeches of the Twentieth Century," ''Guardian'' website

{{DEFAULTSORT:Speeches Lists of speeches Works about history

This list of speeches includes those that have gained

This list of speeches includes those that have gained notability

Notability is the property

of being worthy of notice, having fame, or being considered to be of a high degree of interest, significance, or distinction. It also refers to the capacity to be such. Persons who are notable due to public responsibi ...

in English or in English translation. The earliest listings may be approximate dates.

Before the 1st century

*c.570 BC :Gautama Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in L ...

gives his first sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. ...

at Sarnath

Sarnath (Hindustani pronunciation: aːɾnaːtʰ also referred to as Sarangnath, Isipatana, Rishipattana, Migadaya, or Mrigadava) is a place located northeast of Varanasi, near the confluence of the Ganges and the Varuna rivers in Uttar Pr ...

*431 BC: Funeral Oration by the Greek statesman Pericles

Pericles (; grc-gre, Περικλῆς; c. 495 – 429 BC) was a Greek politician and general during the Golden Age of Athens. He was prominent and influential in Athenian politics, particularly between the Greco-Persian Wars and the Pelo ...

, significant because it departed from the typical formula of Athenian funeral speeches and was a glorification of Athens' achievements, designed to stir the spirits of a nation at war.

*399 BC: The Apology of Socrates, Plato's version of the speech given by the philosopher Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no t ...

, defending himself against charges of being a man "who corrupted the young, refused to worship the gods, and created new deities."

*330 BC: On the Crown

"On the Crown" ( grc, Ὑπὲρ Κτησιφῶντος περὶ τοῦ Στεφάνου, ''Hyper Ktēsiphōntos peri tou Stephanou'') is the most famous judicial oration of the prominent Athenian statesman and orator Demosthenes, delivered in ...

by the Greek orator Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; el, Δημοσθένης, translit=Dēmosthénēs; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual pr ...

, which illustrated the last great phase of political life in Athens.

*63 BC: Catiline Orations

The Catilinarian Orations (; also simply the ''Catilinarians'') are a set of speeches to the Roman Senate given in 63 BC by Marcus Tullius Cicero, one of the year's consuls, accusing a senator, Lucius Sergius Catilina (Catiline), of leading a ...

, given by Marcus Tullius Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

, the consul of Rome, exposing to the Roman Senate the plot of Lucius Sergius Catilina and his friends to overthrow the Roman government.

*44 BC: The Funeral Oration of Roman Dictator, Julius Caesar, delivered by Mark Antony after his assassination; rephrased by William Shakespeare.

*44 BC: The Funeral Oration of Roman Dictator, Julius Caesar, delivered by Mark Antony after his assassination; rephrased by William Shakespeare.

Pre 19th century

*30: TheSermon on the Mount

The Sermon on the Mount ( anglicized from the Matthean Vulgate Latin section title: ) is a collection of sayings attributed to Jesus of Nazareth found in the Gospel of Matthew (chapters 5, 6, and 7). that emphasizes his moral teachings. It ...

, a compilation of the sayings of Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and relig ...

, epitomizing his moral teaching.

*632: The Farewell Sermon

The Farewell Sermon ( ar, خطبة الوداع, ''Khuṭbatu l-Widāʿ'' ) also known as Muhammad's Final Sermon or the Last Sermon, is a religious speech, delivered by the Islamic prophet Muhammad on Friday the 9th of Dhu al-Hijjah, 10 A ...

, delivered by the Islamic prophet, Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

some weeks before his death.

*1095: Beginning of the Christian Crusades by Pope Urban II

Pope Urban II ( la, Urbanus II; – 29 July 1099), otherwise known as Odo of Châtillon or Otho de Lagery, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 March 1088 to his death. He is best known for convening th ...

at the Council of Clermont.

*1521: The Here I Stand speech of

*1521: The Here I Stand speech of Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

, defending himself at the Diet of Worms

The Diet of Worms of 1521 (german: Reichstag zu Worms ) was an imperial diet (a formal deliberative assembly) of the Holy Roman Empire called by Emperor Charles V and conducted in the Imperial Free City of Worms. Martin Luther was summoned t ...

.

*1588: Speech to the Troops at Tilbury

The Speech to the Troops at Tilbury was delivered on 9 August Old Style (19 August New Style) 1588 by Queen Elizabeth I of England to the land forces earlier assembled at Tilbury in Essex in preparation for repelling the expected invasion by ...

by Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

, in preparation for repelling an expected invasion by the Spanish Armada.

*1599: St Crispin's Day Speech

The St Crispin's Day speech is a part of William Shakespeare's history play ''Henry V'', Act IV Scene iii(3) 18–67. On the eve of the Battle of Agincourt, which fell on Saint Crispin's Day, Henry V urges his men, who were vastly outnumbered by ...

by William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

as part of his history play ''Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (121 ...

'' has been famously portrayed by Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the British stage ...

to raise British spirits during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, and by Kenneth Branagh

Sir Kenneth Charles Branagh (; born 10 December 1960) is a British actor and filmmaker. Branagh trained at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London and has served as its president since 2015. He has won an Academy Award, four BAFTAs (plus ...

in the 1989 film ''Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (121 ...

'', and it made famous the phrase "band of brothers".

*1601: The Golden Speech by Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

, in which she revealed that it would be her final Parliament and spoke of the respect she had for the country, her position, and the parliamentarians themselves.

*1630: A Model of Christian Charity

"A Model of Christian Charity" is a sermon by Puritan leader John Winthrop, preached at the Holyrood Church in Southampton before the colonists embarked in the Winthrop Fleet. It is also known as " City upon a Hill" and denotes the notion of Ameri ...

by Puritan leader and Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1587/88 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and one of the leading figures in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led t ...

, in which the phrase " City Upon a Hill" was used and became popular in the North American colonies.

*1681-1704: The sermons and funeral orations of French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

and theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet

Jacques-Bénigne Lignel Bossuet (; 27 September 1627 – 12 April 1704) was a French bishop and theologian, renowned for his sermons and other addresses. He has been considered by many to be one of the most brilliant orators of all time and a ...

during his tenure as the bishop of Meaux Cathedral, whose sermons preached the divine right of kings

In European Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representin ...

during the reign of Louis XIV

Louis XIV (Louis Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was List of French monarchs, King of France from 14 May 1643 until his death in 1715. His reign of 72 years and 110 days is the Li ...

, and who delivered memorable orations across Europe.

*1741: Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God

"Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" is a sermon written by the American theologian Jonathan Edwards, preached to his own congregation in Northampton, Massachusetts, to profound effect, and again on July 8, 1741 in Enfield, Connecticut. The p ...

, a sermon by theologian Jonathan Edwards, noted for the glimpse it provides into the ideas of the religious Great Awakening of 1730–1755 in the United States.

*1775: Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death by U.S. colonial patriot Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry (May 29, 1736June 6, 1799) was an American attorney, planter, politician and orator known for declaring to the Second Virginia Convention (1775): " Give me liberty, or give me death!" A Founding Father, he served as the first a ...

to the Virginia House of Burgesses.

*1791: Abolish the Slave Trade, British Parliamentarian William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 175929 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist and leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, eventually becom ...

's four-hour speech to the House of Commons.

*1792: The Deathless Sermon, given by William Carey during the decline of Hyper-Calvinism in England.

Nineteenth century

*1803: Speech From the Dock by the Irish nationalistRobert Emmet

Robert Emmet (4 March 177820 September 1803) was an Irish Republican, orator and rebel leader. Following the suppression of the United Irish uprising in 1798, he sought to organise a renewed attempt to overthrow the British Crown and Prote ...

.

*1805: Red Jacket

Red Jacket (known as ''Otetiani'' in his youth and ''Sagoyewatha'' eeper Awake''Sa-go-ye-wa-tha'' as an adult because of his oratorical skills) (c. 1750–January 20, 1830) was a Seneca orator and chief of the Wolf clan, based in Western New York ...

's speech defending Native American religion

Native American religions are the spiritual practices of the Native Americans in the United States. Ceremonial ways can vary widely and are based on the differing histories and beliefs of individual nations, tribes and bands. Early European ...

.

*1823: President James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

's State of the Union Address to Congress in which he first stated the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

.

*1837: The American Scholar

"The American Scholar" was a speech given by Ralph Waldo Emerson on August 31, 1837, to the Phi Beta Kappa Society of Harvard College at the First Parish in Cambridge in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was invited to speak in recognition of his gro ...

speech given by Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a cham ...

to the Phi Beta Kappa Society

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal ...

at the First Parish in Cambridge in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

.

*1838: Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

's Lyceum Address, delivered to the Young Men's Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Generally in that type of school the t ...

of Springfield, Illinois

Springfield is the capital of the U.S. state of Illinois and the county seat and largest city of Sangamon County. The city's population was 114,394 at the 2020 census, which makes it the state's seventh most-populous city, the second largest ...

on January 27, 1838, discusses citizenship in a democratic republic

A democratic republic is a form of government operating on principles adopted from a republic and a democracy. As a cross between two exceedingly similar systems, democratic republics may function on principles shared by both republics and democr ...

and internal threats to its institutions.

*1838: The "Divinity School Address

The "Divinity School Address" is the common name for the speech Ralph Waldo Emerson gave to the graduating class of Harvard Divinity School on July 15, 1838. Its formal title is "Acquaint Thyself First Hand with Deity."

Background

Emerson prese ...

", a speech Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a cham ...

gave to the graduating class of Harvard Divinity School

Harvard Divinity School (HDS) is one of the constituent schools of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The school's mission is to educate its students either in the academic study of religion or for leadership roles in religion, gov ...

.

*1851: Ain't I A Woman?

"Ain't I a Woman?" is a speech, delivered extemporaneously, by Sojourner Truth (1797–1883), born into slavery in New York State. Some time after gaining her freedom in 1827, she became a well known anti-slavery speaker. Her speech was deliver ...

, extemporaneously delivered by abolitionist Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth (; born Isabella Baumfree; November 26, 1883) was an American Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist of New York Dutch heritage and a women's rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but esc ...

at a Women's Convention in Akron, Ohio.

*1854: The Peoria speech, made in Peoria, Illinois

Peoria ( ) is the county seat of Peoria County, Illinois, United States, and the largest city on the Illinois River. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 113,150. It is the principal city of the Peoria Metropolitan Area in Ce ...

on October 16, 1854, was with its specific arguments against slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, an important step in Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

's political ascension.

*1856: The Crime against Kansas speech was delivered on the US Senate floor on May 19–20, 1856 by Senator Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

of Massachusetts, a radical Republican, about the conflicts in "bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the ...

."

*1858: A House Divided, in which candidate for the U.S. Senate Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

, speaking of the pre-Civil War United States, quoted Matthew 12:25 and said, "A house divided against itself cannot stand."

*1858: American Infidelity

American Infidelity is the name of a speech that was delivered in the United States Congress by Joshua Giddings in February 1858. This speech was one of many congressional speeches intended to arouse passion about the immorality of slavery. It als ...

, an anti-slavery speech delivered in the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

by Joshua Giddings

Joshua Reed Giddings (October 6, 1795 – May 27, 1864) was an American attorney, politician and a prominent opponent of slavery. He represented Northeast Ohio in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1838 to 1859. He was at first a member ...

*1859: Abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

John Brown's last

A last is a mechanical form shaped like a human foot. It is used by shoemakers and cordwainers in the manufacture and repair of shoes. Lasts typically come in pairs and have been made from various materials, including hardwoods, cast iron ...

speech

Speech is a human vocal communication using language. Each language uses phonetic combinations of vowel and consonant sounds that form the sound of its words (that is, all English words sound different from all French words, even if they are th ...

.

*1860: Cooper Union Address

The Cooper Union speech or address, known at the time as the Cooper Institute speech, was delivered by Abraham Lincoln on February 27, 1860, at Cooper Union, in New York City. Lincoln was not yet the Republican nominee for the presidency, as the ...

by candidate for U.S. President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

, in which Lincoln elaborated his views on slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, affirming that he did not wish it to be expanded into the western territories and claiming that the Founding Fathers would agree with this position.

*1861: The Cornerstone speech

The Cornerstone Speech, also known as the Cornerstone Address, was an oration given by Alexander H. Stephens, Vice President of the Confederate States of America, at the Athenaeum in Savannah, Georgia, on March 21, 1861. The improvised speech, ...

by Alexander Stephens

Alexander Hamilton Stephens (February 11, 1812 – March 4, 1883) was an American politician who served as the vice president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865, and later as the 50th governor of Georgia from 1882 until his death in 1 ...

, vice president of the Confederate States of America, in which he set forth the differences between the constitution of the Confederacy and that of the United States, laid out causes for the American Civil War, and defended slavery.

*1861: Abraham Lincoln's First Inaugural Address

Abraham Lincoln's first inaugural address was delivered on Monday, March 4, 1861, as part of his taking of the oath of office for his first term as the sixteenth President of the United States. The speech, delivered at the United States Capitol ...

, on the eve of the American Civil War.

*1861: Abraham Lincoln's Fourth of July Address, a written statement sent to the U.S. Congress, recounts the initial stages of the American Civil War and sets out Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

's analysis of the southern slave states rebellion as well as Lincoln's thoughts on the war and American society.

*1862: The Blood and Iron speech by Prussian

*1862: The Blood and Iron speech by Prussian Minister-President

A minister-president or minister president is the head of government in a number of European countries or subnational governments with a parliamentary or semi-presidential system of government where they preside over the council of ministers. I ...

Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of ...

on the unification of Germany.

*1863: The Gettysburg Address

The Gettysburg Address is a speech that U.S. President Abraham Lincoln delivered during the American Civil War at the dedication of the Soldiers' National Cemetery, now known as Gettysburg National Cemetery, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on the ...

by Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

, resolving that government "of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth."

*1865: Lincoln's Second Inaugural, in which the President sought to avoid harsh treatment of the defeated South.

*1873: The "Is it a Crime for a Citizen of the United States to Vote?" speech by Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to s ...

, who in her effort to introduce women's suffrage into the United States asked her fellow citizens "how can the “consent of the governed

In political philosophy, the phrase consent of the governed refers to the idea that a government's legitimacy and moral right to use state power is justified and lawful only when consented to by the people or society over which that political pow ...

” be given if the right to vote be denied?"

*1877: The Surrender of Nez Perce Chief Joseph, pledging to "fight no more forever."

*1880: Dostoyevsky's Pushkin Speech

"Dostoyevsky's Pushkin Speech" was a speech delivered by Fyodor Dostoyevsky in honour of the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (; rus, links=no, Александр Сергеевич ПушкинIn pre-Revolutiona ...

, a speech delivered by Fyodor Dostoyevsky in honour of the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (; rus, links=no, Александр Сергеевич ПушкинIn pre-Revolutionary script, his name was written ., r=Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈpuʂkʲɪn, ...

.

*1890–1900s: Acres of Diamonds

Russell Herman Conwell (February 15, 1843 – December 6, 1925) was an American Baptist minister, orator, philanthropist, author, lawyer, and writer. He is best remembered as the founder and first president of Temple University in Philadelph ...

speeches by Temple University President Russell Conwell, the central idea of which was that the resources to achieve all good things were present in one's own community.

*1893: Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda (; ; 12 January 1863 – 4 July 1902), born Narendranath Datta (), was an Indian Hindu monk, philosopher, author, religious teacher, and the chief disciple of the Indian mystic Ramakrishna. He was a key figure in the intr ...

's address at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago, in which the Indian sage introduced Hinduism to North America.

*1895: The Atlanta Exposition Speech, an address on the topic of race relations given by Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

.

*1896: Cross of Gold by U.S. presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

, advocating bimetallism.

Twentieth century

Pre-World War I and World War I

*1900:Hun Speech

The Hun speech was delivered by German emperor Wilhelm II on 27 July 1900 in Bremerhaven, on the occasion of the farewell of parts of the German East Asian Expeditionary Corps (). The expeditionary corps were sent to Imperial China ...

by Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

, the emperor's reaction to the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an Xenophobia, anti-foreign, anti-colonialism, anti-colonial, and Persecution of Christians#China, anti-Christian uprising in China ...

in which he demands to counter the insurgency with brutal force (like the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

).

*1901: Votes for Women

A vote is a formal method of choosing in an election.

Vote(s) or The Vote may also refer to:

Music

*''V.O.T.E.'', an album by Chris Stamey and Yo La Tengo, 2004

*"Vote", a song by the Submarines from ''Declare a New State!'', 2006

Television

* " ...

, by the American writer Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has pr ...

.

*1906: I warn the Government, by Conservative member F.E. Smith in the British House of Commons.

*1910: The Man in the Arena

Citizenship in a Republic is the title of a speech given by Theodore Roosevelt, former President of the United States, at the Sorbonne in Paris, France, on April 23, 1910.

One notable passage from the speech is referred to as "The Man in the Are ...

, by U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, quoted by President Richard Nixon and cited by South Africa President Nelson Mandela.

*1915: Ireland Unfree Shall Never Be at Peace

"Ireland unfree shall never be at peace" were the climactic closing words of the graveside oration of Patrick Pearse at the funeral of Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa on 1 August 1915. The oration roused Irish republican feeling and was a significant e ...

, by Irish Nationalist Patrick Pearse, significant in the lead-up to the Easter Rising of 1916.

*1917: War Message to Congress by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

.

*1917: The April Theses

The April Theses (russian: апрельские тезисы, transliteration: ') were a series of ten directives issued by the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin upon his April 1917 return to Petrograd from his exile in Switzerland via Germa ...

, a series of ten directives issued by Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

upon his return to Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

from his exile in Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

*1918: Fourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms ...

by Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

, laying out the terms for the end of World War I.

Inter-war years and World War II

*1930:Allahabad Address

The Allahabad Address ( ur, ) was a speech by scholar, Sir Muhammad Iqbal, one of the best-known in Pakistani history. It was delivered by Iqbal during the 21st annual session of the All-India Muslim League, on the afternoon of Monday, 29 Decemb ...

by Muhammad Iqbal

Sir Muhammad Iqbal ( ur, ; 9 November 187721 April 1938), was a South Asian Muslim writer, philosopher, Quote: "In Persian, ... he published six volumes of mainly long poems between 1915 and 1936, ... more or less complete works on philos ...

. Presented the idea of a separate homeland for Indian Muslims

Islam is India's second-largest religion, with 14.2% of the country's population, approximately 172.2 million people identifying as adherents of Islam in 2011 Census. India is also the country with the second or third largest number of Muslim ...

which was ultimately realized in the form of Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

.

*1932: The Bomber Will Always Get Through

"The bomber will always get through" was a phrase used by Stanley Baldwin in a 1932 speech "A Fear for the Future" given to the British Parliament. His speech stated that contemporary bomber aircraft had the performance necessary to conduct a st ...

. a phrase used by English statesman Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

in a House of Commons speech, "A Fear For The Future."

*1933: You Cannot Take Our Honour by Otto Wels, the only German Parliamentarian to speak against the Enabling Act, which took the power of legislation away from the Parliament and handed it to Adolf Hitler's cabinet.

*1933: The Only Thing We Have to Fear Is Fear Itself, from the first inaugural address of U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

.

*1933: Atatürk's Tenth Year Speech, given by the President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or Mustafa Kemal Pasha until 1921, and Ghazi Mustafa Kemal from 1921 Surname Law (Turkey), until 1934 ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish Mareşal (Turkey), field marshal, Turkish National Movement, re ...

in Ankara

Ankara ( , ; ), historically known as Ancyra and Angora, is the capital of Turkey. Located in the central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5.1 million in its urban center and over 5.7 million in Ankara Province, maki ...

Hippodrome.

*1934: Every Man A King, a phrase used in many speeches by Louisiana Governor Huey Long

Huey Pierce Long Jr. (August 30, 1893September 10, 1935), nicknamed "the Kingfish", was an American politician who served as the 40th governor of Louisiana from 1928 to 1932 and as a United States senator from 1932 until his assassination ...

.

*1934: Speech of Gallipoli by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or Mustafa Kemal Pasha until 1921, and Ghazi Mustafa Kemal from 1921 Surname Law (Turkey), until 1934 ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish Mareşal (Turkey), field marshal, Turkish National Movement, re ...

*1936: Address to the League of Nations by the Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia

Haile Selassie I ( gez, ቀዳማዊ ኀይለ ሥላሴ, Qädamawi Häylä Səllasé, ; born Tafari Makonnen; 23 July 189227 August 1975) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as Ethiopian aristocratic and court titles ...

on the invasion of his country by Benito Mussolini of Italy.

*1936: Unamuno's Last Lecture by Miguel de Unamuno

Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo (29 September 1864 – 31 December 1936) was a Spanish essayist, novelist, poet, playwright, philosopher, professor of Greek and Classics, and later rector at the University of Salamanca.

His major philosophical essa ...

, in which he criticized the Spanish Nationalists

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spai ...

.

*1939: The Luckiest Man on the Face of the Earth, by baseball player Lou Gehrig

Henry Louis Gehrig (born Heinrich Ludwig Gehrig ; June 19, 1903June 2, 1941) was an American professional baseball first baseman who played 17 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the New York Yankees (1923–1939). Gehrig was renowned f ...

upon his retirement from the New York Yankees.

*1939: King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of In ...

of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

delivers a radio address at the outbreak of World War II calling for his subjects in Britain and the Empire to stand firm in the dark days ahead.

*1939: Reichstag Speech, also known as Hitler's prophecy speech. Amid rising international tensions Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

tells the German public and the world that the outbreak of war would mean the end of European Jewry.

*1940: The Presidential address by Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (, ; born Mahomedali Jinnahbhai; 25 December 1876 – 11 September 1948) was a barrister, politician, and the founder of Pakistan. Jinnah served as the leader of the All-India Muslim League from 1913 until the ...

to the All India Muslim League

The All-India Muslim League (AIML) was a political party established in Dhaka in 1906 when a group of prominent Muslim politicians met the Viceroy of British India, Lord Minto, with the goal of securing Muslim interests on the Indian subcont ...

's session in Lahore

Lahore ( ; pnb, ; ur, ) is the second List of cities in Pakistan by population, most populous city in Pakistan after Karachi and 26th List of largest cities, most populous city in the world, with a population of over 13 million. It is th ...

, 1940 on passing of Lahore Resolution

The Lahore Resolution ( ur, , ''Qarardad-e-Lahore''; Bengali: লাহোর প্রস্তাব, ''Lahor Prostab''), also called Pakistan resolution, was written and prepared by Muhammad Zafarullah Khan and was presented by A. K. Fazlul ...

also known as Pakistan Resolution

The Lahore Resolution ( ur, , ''Qarardad-e-Lahore''; Bengali: লাহোর প্রস্তাব, ''Lahor Prostab''), also called Pakistan resolution, was written and prepared by Muhammad Zafarullah Khan and was presented by A. K. Fazlu ...

Transcript.

*1940: The

Norway Debate

The Norway Debate, sometimes called the Narvik Debate, was a momentous debate in the British House of Commons from 7 to 9 May 1940, during the Second World War. The official title of the debate, as held in the '' Hansard'' parliamentary archiv ...

speeches, where Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeaseme ...

, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

defended the Chamberlain government's war policies Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

, Archibald Sinclair

Archibald Henry Macdonald Sinclair, 1st Viscount Thurso, (22 October 1890 – 15 June 1970), known as Sir Archibald Sinclair between 1912 and 1952, and often as Archie Sinclair, was a British politician and leader of the Liberal Party.

Backgr ...

, Roger Keyes

Admiral of the Fleet Roger John Brownlow Keyes, 1st Baron Keyes, (4 October 1872 – 26 December 1945) was a British naval officer.

As a junior officer he served in a corvette operating from Zanzibar on slavery suppression missions. Ea ...

, Leo Amery, Arthur Greenwood

Arthur Greenwood, (8 February 1880 – 9 June 1954) was a British politician. A prominent member of the Labour Party from the 1920s until the late 1940s, Greenwood rose to prominence within the party as secretary of its research department f ...

, Herbert Morrison

Herbert Stanley Morrison, Baron Morrison of Lambeth, (3 January 1888 – 6 March 1965) was a British politician who held a variety of senior positions in the UK Cabinet as member of the Labour Party. During the inter-war period, he was Minis ...

, David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for lea ...

, and others.

*1940: The Appeal of 18 June

The Appeal of 18 June (french: L'Appel du 18 juin) was the first speech made by Charles de Gaulle after his arrival in London in 1940 following the Battle of France. Broadcast to Vichy France by the radio services of the British Broadcasting Cor ...

, French leader Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Governm ...

's radio broadcast from London, the beginning of the Resistance to German occupation during World War II.

*1940: Blood, Toil, Tears, and Sweat

The phrase "blood, toil, tears and sweat" became famous in a speech given by Winston Churchill to the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom on 13 May 1940. The speech is sometimes known by that name.

Background

This was Ch ...

, a phrase used by U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt in 1897 but popularized by Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

in the first of three inspirational radio addresses during the opening months of World War II.

*1940: We Shall Fight on the Beaches

"We shall fight on the beaches" is a common title given to a speech delivered by the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom on 4 June 1940. This was the second of three major ...

, from the second radio talk by Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, promising to never surrender.

*1940: This Was Their Finest Hour

"This was their finest hour" was a speech delivered by Winston Churchill to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom on 18 June 1940, just over a month after he took over as Prime Minister at the head of an all-party coalition government.

It w ...

, the third address by Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, giving a confident view of the military situation and rallying the British people.

*1940: Never Was So Much Owed by So Many to So Few

"Never was so much owed by so many to so few" was a wartime speech delivered to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom by British prime minister Winston Churchill on 20 August 1940. The name stems from the specific line in the speech, "N ...

by Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, speaking in another radio talk about the air and naval defenders of Great Britain.

*1940: The final speech in ''The Great Dictator

''The Great Dictator'' is a 1940 American anti-war political satire black comedy film written, directed, produced, scored by, and starring British comedian Charlie Chaplin, following the tradition of many of his other films. Having been the onl ...

'' by Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is conside ...

in the role of a Jewish barber, in which he demanded solidarity between all people and a return to values like peace, empathy and freedom.

*1940: Arsenal of Democracy

"Arsenal of Democracy" was the central phrase used by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in a radio broadcast on the threat to national security, delivered on December 29, 1940—nearly a year before the United States entered the Second Worl ...

, a radio address by U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, who warned against a sense of complacency if Britain were to fall to the Axis powers.

*1941: Three Sermons in Defiance of the Nazis, in which German Bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen issued forceful, public denunciations of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

's euthanasia

Euthanasia (from el, εὐθανασία 'good death': εὖ, ''eu'' 'well, good' + θάνατος, ''thanatos'' 'death') is the practice of intentionally ending life to eliminate pain and suffering.

Different countries have different eut ...

programs and persecution of the Catholic Church.

*1941: Four Freedoms

The Four Freedoms were goals articulated by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt on Monday, January 6, 1941. In an address known as the Four Freedoms speech (technically the 1941 State of the Union address), he proposed four fundamental freed ...

, in which Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

outlined goals for peace but called for a massive build-up of U.S. arms production.

*1941: A Date Which Will Live in Infamy

The "Day of Infamy" speech, sometimes referred to as just ''"The Infamy speech"'', was delivered by Franklin D. Roosevelt, the 32nd president of the United States, to a joint session of Congress on December 8, 1941. The previous day, the Empi ...

, post-Pearl Harbor speech to the U.S. Congress in which Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

called for a declaration of war against Japan.

*1941: Declaration of war against United States by the German Führer, German Chancellor, and Führer of the Nazi Party, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

, in which he announced Germany has declared war on the United States.

*1942: Quit India

The Quit India Movement, also known as the August Kranti Movement, was a movement launched at the Bombay session of the All India Congress Committee by Mahatma Gandhi on 8th August 1942, during World War II, demanding an end to British rule ...

by Mohandas K. Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

also known as Mahatma Gandhi, calling for determined, but nonviolent, resistance against British colonial rule

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

.

*1942: The Forgotten People by the Australian Liberal Party leader Sir Robert Menzies, defining and exalting the nation's middle class.

* 1942: Slovak, cast off your parasite! by Jozef Tiso, president of the Slovak State

Slovak may refer to:

* Something from, related to, or belonging to Slovakia (''Slovenská republika'')

* Slovaks

The Slovaks ( sk, Slováci, singular: ''Slovák'', feminine: ''Slovenka'', plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group ...

, defending Slovakia's role in the Holocaust.

*1942: Hitler Stalingrad Speech by the German Führer, German Chancellor, and Führer of the Nazi Party, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

, talking about the ongoing Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II where Nazi Germany and its allies unsuccessfully fought the Soviet Union for control of the city of Stalingrad (later r ...

.

*1943: Do You Want Total War? by Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the '' Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to ...

, who exhorted the Germans to continue the war even though it would be long and difficult.

*1943: A page of glory...never to be written were two secret speeches made by '' Reichsführer''- SS Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

in which for the first time a high-ranking member of the Nazi government spoke openly of the ongoing extermination of the European Jews.

*1944: The First Bayeux speech, delivered by General Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Governm ...

of France in the context of liberation after the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

.

*1944: Patton's Speech, a profanity-laden speech to the United States Third Army

The United States Army Central, formerly the Third United States Army, commonly referred to as the Third Army and as ARCENT, is a military formation of the United States Army which saw service in World War I and World War II, in the 1991 Gulf Wa ...

by United States General George S. Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh United States Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, and the Third United States Army in France ...

, calling for the troops' bravery in spite of their fears. It was given prior to the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

.

*1944: Paris Liberated by Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Governm ...

on the day he took up governmental duties at the War Ministry in Paris.

*1945: Hirohito surrender broadcast (Gyokuon-hōsō), recorded by Japanese Emperor Hirohito and broadcast as an unconditional capitulation to the Allies.

1945–1991 Cold War years

*1946: Sinews of Peace byWinston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, introducing the phrase ''Iron Curtain'' to describe the division between eastern and western Europe.

*1946: The First Bayeux speech, delivered by General

*1946: The First Bayeux speech, delivered by General Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Governm ...

describing the postwar constitution of France.

*1947: Muhammad Ali Jinnah's 11 August Speech

The Eleventh August Speech was a speech made by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, founding father of Pakistan and known as Quaid-e-Azam (Great Leader) to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan. While Pakistan was created as a result of what could be describ ...

on the eve of independence from Britain about the struggle for Pakistan, injustices in partition, future road map for running the country, justice, equality and religious freedom for all.

*1947: Tryst with Destiny by Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India du ...

, given on the eve of Indian independence and concerning the country's history.

*1948: The Light Has Gone Out of Our Lives

The light has gone out of our lives is a speech that was delivered ex tempore by Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India, on January 30, 1948, following the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi earlier that evening. It is often cited as o ...

by Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India du ...

, about the assassination of Mohandas K. Gandhi also known as Mahatma Gandhi.

*1949: Four Points by U.S. President Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

, setting his postwar goals.

*1949: The Light on the Hill

"The light on the hill" is a phrase used to describe the objective of the Australian Labor Party. The phrase, which was used in a 1949 conference speech at the Sydney Trades Hall by then Prime Minister Ben Chifley, has Biblical origins. ' City ...

by Australia Prime Minister Ben Chifley

Joseph Benedict Chifley (; 22 September 1885 – 13 June 1951) was an Australian politician who served as the 16th prime minister of Australia from 1945 to 1949. He held office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1945, follow ...

, paying tribute to the country's labour movement.

*1950: The Declaration of Conscience

The Declaration of Conscience was a Cold War speech made by U.S. Senator from Maine, Margaret Chase Smith on June 1, 1950, less than four months after Senator Joe McCarthy's " Wheeling Speech," on February 9, 1950. Her speech was endorsed by six ot ...

, a speech made by U.S. Senator Margaret Chase Smith calling for the country to re-examine the tactics used by the House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative United States Congressional committee, committee of the United States House of Representatives, create ...

.

*1951: Old Soldiers Never Die

''Old Soldiers Never Die'' is a 1931 British comedy film directed by Monty Banks and starring Leslie Fuller, Molly Lamont and Alf Goddard. It was made at Elstree Studios by British International Pictures. It was produced as a quota quickie f ...

by U.S. General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was ...

in an appearance before Congress after being fired by President Truman as Supreme Commander in the Korean War

*1952: The political Checkers speech

The Checkers speech or Fund speech was an address made on September 23, 1952, by Senator Richard Nixon ( R- CA), six weeks before the 1952 United States presidential election, in which he was the Republican nominee for Vice President. Nixon had ...

by U.S. vice-presidential candidate Richard M. Nixon, in which he mentioned his family's pet dog of that name.

*1953: The Chance for Peace was an address by U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

shortly after the death of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin that highlighted the cost of the US–Soviet rivalry to both nations.

*1953: History Will Absolve Me

''History Will Absolve Me'' (Spanish: ''La historia me absolverá'') is the title of a two-hour speech made by Fidel Castro on 16 October 1953. Castro made the speech in his own defense in court against the charges brought against him after he led ...

, a four-hour judicial defense by revolutionary Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

on charges of leading an attack on Cuban Army barracks.

*1953: Atoms for Peace

"Atoms for Peace" was the title of a speech delivered by U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower to the UN General Assembly in New York City on December 8, 1953.

The United States then launched an "Atoms for Peace" program that supplied equipment ...

, an address by Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

on the creation of an international body to both regulate and promote the peaceful use of atomic power.

*1956: On the Personality Cult and its Consequences

"On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences" (russian: «О культе личности и его последствиях», «''O kul'te lichnosti i yego posledstviyakh''»), popularly known as the "Secret Speech" (russian: секре ...

by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

, castigating actions taken by the regime of deceased Communist Party secretary Joseph Stalin. Widely known as the "Secret Speech" because it was delivered at a closed session of that year's Communist Party Congress.

*1956: We Will Bury You

"We will bury you" (russian: «Мы вас похороним!», translit="My vas pokhoronim!") is a phrase that was used by Soviet First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev while addressing Western ambassadors at a reception at the Polish embassy i ...

by Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

, addressing Western ambassadors at a reception in the Polish embassy in Moscow.

*1957: Longest Speech in the United Nations by Indian delegate V.K. Krishna Menon

Vengalil Krishnan Krishna Menon (3 May 1896 – 6 October 1974) was an Indian academic, politician, and non-career diplomat. He was described by some as the second most powerful man in India, after the first Prime Minister of India, Jawa ...

.

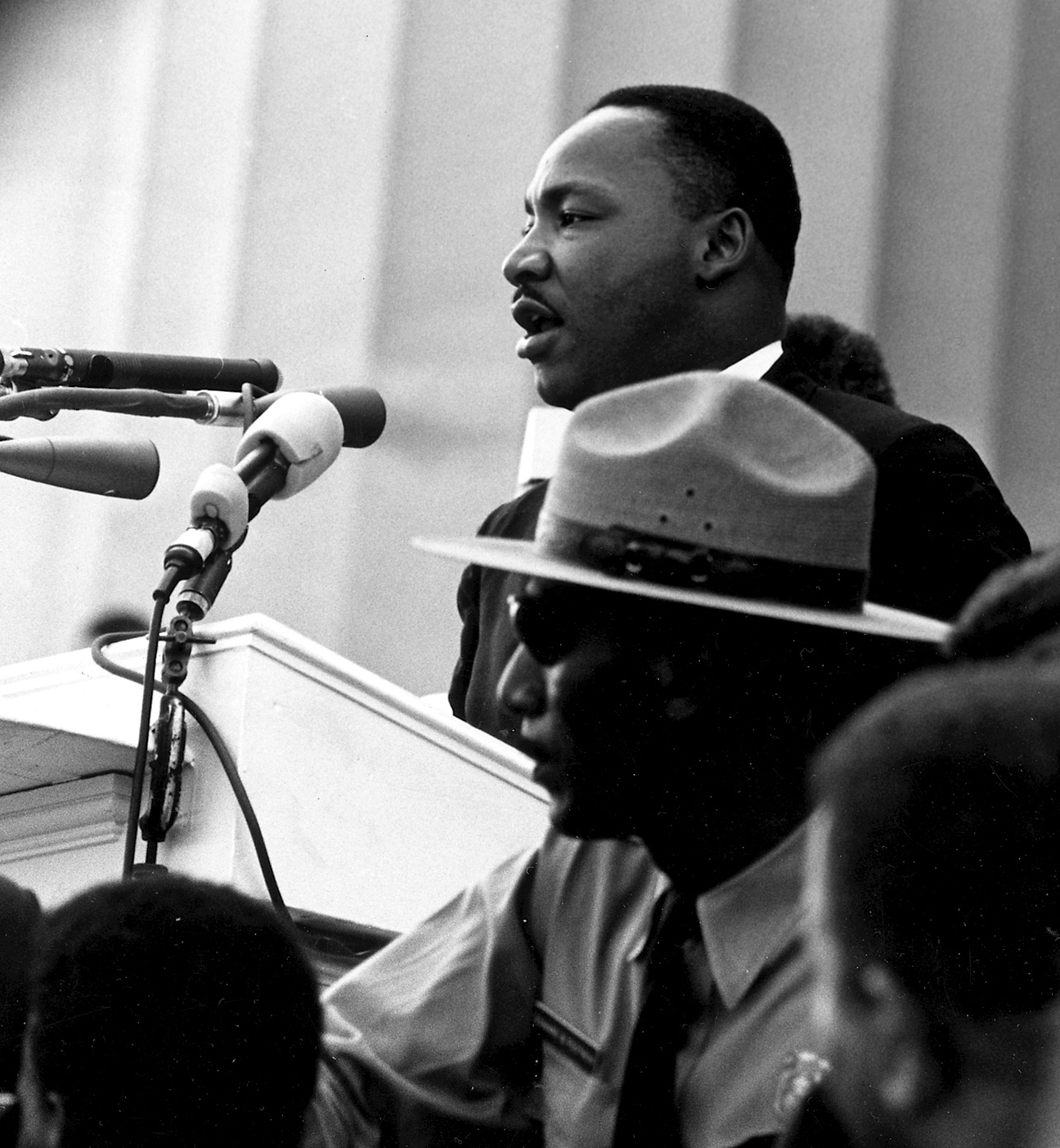

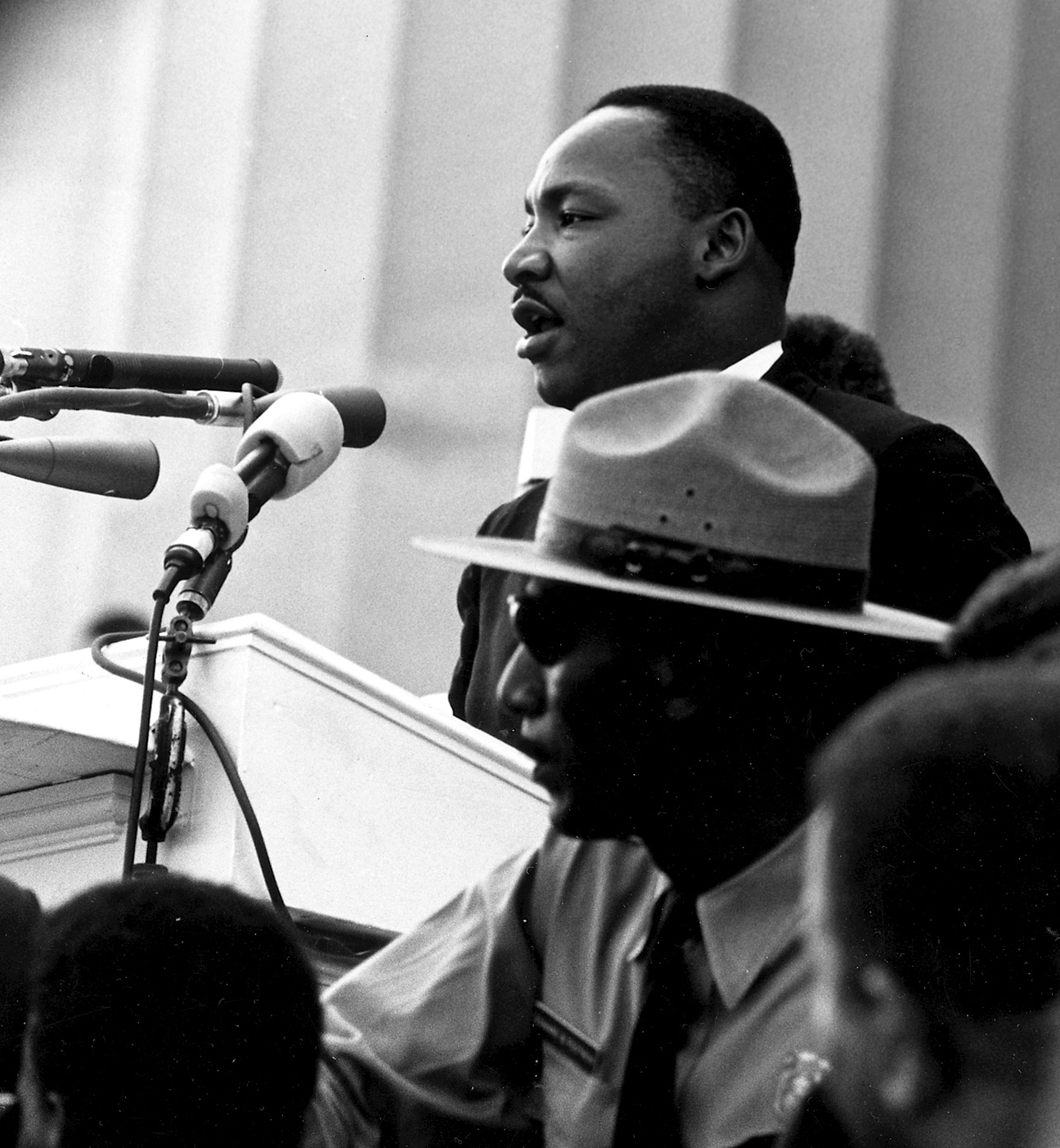

*1957: Give Us the Ballot

"Give Us the Ballot" is a 1957 speech by Martin Luther King Jr. advocating voting rights for African Americans in the United States. King delivered the speech at the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom gathering at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D ...

by Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

, an appeal for voting rights made at the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom

The Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom, or Prayer Pilgrimage to Washington, was a 1957 demonstration in Washington, D.C., an early event in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. It was the occasion for Martin Luther King Jr.'s ''Give Us th ...

at the Lincoln Memorial

The Lincoln Memorial is a U.S. national memorial built to honor the 16th president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln. It is on the western end of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., across from the Washington Monument, and is in the ...

*1959: There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom

"There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom: An Invitation to Enter a New Field of Physics" was a lecture given by physicist Richard Feynman at the annual American Physical Society meeting at Caltech on December 29, 1959. Feynman considered the possibi ...

by physicist Richard Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman (; May 11, 1918 – February 15, 1988) was an American theoretical physicist, known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics, the physics of the superflu ...

, on the possibility of direct manipulation of individual atoms as a new form of chemical synthesis.

*1960: Address to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association" by then-candidate John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

in Houston, Texas, to address fears that his being a member of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

would impact his decision-making as President.

*1960: Wind of Change speech by British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was a British Conservative statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Caricatured as "Supermac", he ...

in South Africa, in which Macmillan reiterated his support for the decolonization of Africa

The decolonisation of Africa was a process that took place in the Scramble for Africa, mid-to-late 1950s to 1975 during the Cold War, with radical government changes on the continent as Colonialism, colonial governments made the transition to So ...

.

*1960: Congolese Independence speech

The Speech at the Ceremony of the Proclamation of the Congo's Independence was a short political speech given by Patrice Lumumba on 30 June 1960 at the ceremonies marking the independence of the Republic of Congo (the modern-day Democratic Rep ...

by Congolese independence leader and its first democratically elected Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba (; 2 July 1925 – 17 January 1961) was a Congolese politician and independence leader who served as the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then known as the Republic of the Congo) from June u ...

in South Africa, in which he described the suffering of the Congolese under Belgian colonialism and the negatives that lay behind the pageantry and paternalism of the Belgian "civilising mission

The civilizing mission ( es, misión civilizadora; pt, Missão civilizadora; french: Mission civilisatrice) is a political rationale for military intervention and for colonization purporting to facilitate the Westernization of indigenous pe ...

" begun by Leopold II in the Congo Free State

''(Work and Progress)

, national_anthem = Vers l'avenir

, capital = Vivi Boma

, currency = Congo Free State franc

, religion = Catholicism (''de facto'')

, leader1 = Leopo ...

.

*1961: Eisenhower's farewell address

Eisenhower's farewell address (sometimes referred to as "Eisenhower's farewell address to the nation") was the final public speech of Dwight D. Eisenhower as the 34th President of the United States, delivered in a television broadcast on Januar ...

, a speech at the end of the term of President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

, in which he warned of the rise of the "military–industrial complex

The expression military–industrial complex (MIC) describes the relationship between a country's military and the defense industry that supplies it, seen together as a vested interest which influences public policy. A driving factor behind the r ...

" in the United States.

*1961: Ask Not What Your Country Can Do For You, the inaugural address of U.S. President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

, in which he advised his "fellow Americans" to "ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country."

*1961: The Vast Wasteland

"Television and the Public Interest" was a speech given by Federal Communications Commission (FCC) chairman Newton N. Minow to the convention of the National Association of Broadcasters on May 9, 1961. The speech was Minow's first major speech afte ...

speech by Newton Minow

Newton Norman Minow (born January 17, 1926) is an American attorney and former Chair of the Federal Communications Commission. He is famous for his speech referring to television as a "vast wasteland". While still maintaining a law practice, Min ...

, chairman of the U.S. Federal Communications Commission, in which he asserted that "when television is bad, nothing is worse."

*1962: Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

turned his concession speech in the California gubernatorial election into a 15-minute monologue aimed mainly at the press, famously (though as it turned out, prematurely) stating "...you don't have Nixon to kick around any more, because, gentlemen, this is my last press conference."

*1962: The "We choose to go to the Moon

"We choose to go to the Moon", officially titled the Address at Rice University on the Nation's Space Effort, is a September 12, 1962, speech by United States President John F. Kennedy to bolster public support for his proposal to land a man ...

" speech by U.S President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

to drum up public support for the Apollo Program at Rice University

William Marsh Rice University (Rice University) is a Private university, private research university in Houston, Houston, Texas. It is on a 300-acre campus near the Houston Museum District and adjacent to the Texas Medical Center. Rice is ranke ...

, where he reiterated his commitment to reaching the Moon by the end of the decade.

*1963: Segregation Now, Segregation Tomorrow, Segregation Forever by Alabama Governor George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Alabama for four terms. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best remembered for his staunch segregationist and ...

, which became a rallying cry for those opposed to racial integration and the U.S. civil rights movement.

*1963: I Am Prepared To Die

"I Am Prepared to Die" is the name given to the three-hour speech given by Nelson Mandela on 20 April 1964 from the dock of the defendant at the Rivonia Trial. The speech is so titled because it ends with the words "it is an ideal for which ...

by South African leader Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist who served as the President of South Africa, first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1 ...

at his trial in which he laid out the reasoning for using violence as a tactic against apartheid.

*1963: American University Speech

The American University speech, titled "A Strategy of Peace", was a commencement address delivered by United States President John F. Kennedy at the American University in Washington, D.C., on Monday, June 10, 1963. Delivered at the height o ...

by U.S. President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

to construct a better relationship with the Soviet Union and to prevent another threat of nuclear war after the events of the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962.

*1963: Report to the American People on Civil Rights

The Report to the American People on Civil Rights was a speech on civil rights, delivered on radio and television by United States President John F. Kennedy from the Oval Office on June 11, 1963 in which he proposed legislation that would later be ...

by John F. Kennedy speaking from the Oval Office.

*1963: ''Ich Bin Ein Berliner

"" (; "I am a Berliner") is a speech by United States President John F. Kennedy given on June 26, 1963, in West Berlin. It is one of the best-known speeches of the Cold War and among the most famous anti-communist speeches.

Twenty-two months ...

'' ("I am a Berliner") by U.S. President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

, voicing support for the people of West Berlin.

*1963: I Have a Dream

"I Have a Dream" is a public speech that was delivered by American civil rights activist and Baptist minister, Martin Luther King Jr., during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963. In the speech, King called ...