Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

from 1922 until 1991. In the anthem of the Ukrainian SSR, it was referred to simply as ''Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian invas ...

''. Under the Soviet one-party model, the Ukrainian SSR was governed by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union through its republican branch: the Communist Party of Ukraine

The Communist Party of Ukraine, Abbreviation: KPU, from Ukrainian and Russian "" is a banned political party in Ukraine. It was founded in 1993 as the successor to the Soviet-era Communist Party of Ukraine which was banned in 1991 (accord ...

.

The first iterations of the Ukrainian SSR were established during the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

, particularly after the Bolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

. The outbreak of the Ukrainian–Soviet War

The Ukrainian–Soviet War ( uk, радянсько-українська війна, translit=radiansko-ukrainska viina) was an armed conflict from 1917 to 1921 between the Ukrainian People's Republic and the Bolsheviks ( Soviet Ukraine and ...

in the former Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

saw the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

defeat the independent Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

, after which they founded the Ukrainian People's Republic of Soviets

The Ukrainian People's Republic of Soviets (russian: Украинская Народная Республика Советов, translit=Ukrainskaya Narodnaya Respublika Sovjetov) was a short-lived (1917–1918) Soviet republic of the Russian S ...

as a republic of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

in December 1917; it was later succeeded by the Ukrainian Soviet Republic

The Ukrainian Soviet Republic (russian: Украинская Советская Республика, translit= Ukrainskaya Sovetskaya Respublika) was one of the earlier Soviet Ukrainian quasi-state formations (Ukrainian People's Republic of S ...

in 1918, also under the Russian SFSR. Simultaneously with the Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

, the Ukrainian War of Independence

The Ukrainian War of Independence was a series of conflicts involving many adversaries that lasted from 1917 to 1921 and resulted in the establishment and development of a Ukrainian republic, most of which was later absorbed into the Soviet U ...

was being fought among the different Ukrainian republics founded by Ukrainian nationalists, Ukrainian anarchists

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* S ...

, and Ukrainian Bolsheviks—with either help or opposition from neighbouring states. As a Soviet quasi-state, the newly-established Ukrainian SSR became a founding member of the United Nations alongside the Byelorussian SSR

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR, or Byelorussian SSR; be, Беларуская Савецкая Сацыялістычная Рэспубліка, Bielaruskaja Savieckaja Sacyjalistyčnaja Respublika; russian: Белор� ...

, in spite of the fact that they were legally represented by the All-Union in foreign affairs. In 1922, it was one of four Soviet republics (with the Russian SFSR, the Byelorussian SSR, and the Transcaucasian SFSR

, conventional_long_name = Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic

, common_name = Transcaucasian SFSR

, p1 = Armenian Soviet Socialist RepublicArmenian SSR

, flag_p1 = Flag of SSRA ...

) that signed the Treaty on the Creation of the Soviet Union. Upon the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Ukrainian SSR emerged as the present-day independent state of Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian invas ...

, although the Soviet constitution remained in use throughout the country until the adoption of the Ukrainian constitution in June 1996.

Throughout its 72-year history, the republic's borders changed many times, with a significant portion of what is now western Ukraine

Western Ukraine or West Ukraine ( uk, Західна Україна, Zakhidna Ukraina or , ) is the territory of Ukraine linked to the former Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, which was part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Austri ...

having been annexed from eastern Poland in 1939, with significant portions of Romania in 1940, alongside another addition of territory in 1945 from Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia ( rue, Карпатьска Русь, Karpat'ska Rus'; uk, Закарпаття, Zakarpattia; sk, Podkarpatská Rus; hu, Kárpátalja; ro, Transcarpatia; pl, Zakarpacie); cz, Podkarpatská Rus; german: Karpatenukrai ...

in Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. From the 1919 establishment of the Ukrainian SSR until 1934, the city of Kharkov

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

served as its capital; however, the republic's seat of government was subsequently relocated in 1934 to the city of Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

, the historic Ukrainian capital, and remained at Kiev for the remainder of its existence.

Geographically, the Ukrainian SSR was situated in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, wh ...

, to the north of the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, ...

, and was bordered by the Soviet republics of Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centra ...

, Byelorussia, and Russia, and the countries of Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Poland. The republic's border with Czechoslovakia formed the Soviet Union's westernmost border point. According to the 1989 Soviet census

The 1989 Soviet census (russian: Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989, lit=1989 All-Union Census), conducted between 12 and 19 January of that year, was the last one that took place in the Soviet Union. The census found ...

, the republic of Ukraine had a population of 51,706,746, which fell sharply after the Soviet Union's dissolution in 1991.

Name

Its original name in 1919 was Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Соціалісти́чна Радя́нська Респу́бліка, translit=Ukrainska Sotsialistychna Radianska Respublika, abbreviated ). After the ratification of the1936 Soviet Constitution

Events

January–February

* January 20 – George V of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions and Emperor of India, dies at his Sandringham Estate. The Prince of Wales succeeds to the throne of the United Kingdom as King ...

, the names of all Soviet republics were changed, transposing the second (''socialist'') and third (''sovietskaya'' in Russian or ''radianska'' in Ukrainian) words. In accordance, on 5 December 1936, the 8th Extraordinary Congress Soviets in Soviet Union changed the name of the republic to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, which was ratified by the 14th Extraordinary Congress of Soviets in Ukrainian SSR on 31 January 1937.

The name ''Ukraine'' ( la, Vkraina) is a subject of debate. It is often perceived as being derived from the Slavic word "okraina", meaning "border land". It was first used to define part of the territory of Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas of ...

( Ruthenia) in the 12th century, at which point Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

was the capital of Rus'. The name has been used in a variety of ways since the twelfth century. For example, Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks, Zaporozhian Cossack Army, Zaporozhian Host, (, or uk, Військо Запорізьке, translit=Viisko Zaporizke, translit-std=ungegn, label=none) or simply Zaporozhians ( uk, Запорожці, translit=Zaporoz ...

called their hetmanate "Ukraine".

Within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ...

, the name carried unofficial status for larger part of Kiev Voivodeship

The Kiev Voivodeship ( pl, województwo kijowskie, la, Palatinatus Kioviensis, uk, Київське воєводство, ''Kyjivśke vojevodstvo'') was a unit of administrative division and local government in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

.

"''The'' Ukraine" used to be the usual form in English, despite Ukrainian not having a definite article

An article is any member of a class of dedicated words that are used with noun phrases to mark the identifiability of the referents of the noun phrases. The category of articles constitutes a part of speech.

In English, both "the" and "a(n)" ...

. Since the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine

The Act of Declaration of Independence of Ukraine ( uk, Акт проголошення незалежності України, Akt proholoshennya nezalezhnosti Ukrayiny) was adopted by the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republi ...

, this form has become less common in the English-speaking world

Speakers of English are also known as Anglophones, and the countries where English is natively spoken by the majority of the population are termed the ''Anglosphere''. Over two billion people speak English , making English the largest languag ...

, and style-guides warn against its use in professional writing. According to U.S. ambassador William Taylor, "The Ukraine" now implies disregard for the country's sovereignty. The Ukrainian position is that the usage of "'The Ukraine' is incorrect both grammatically and politically."

History

After the abdication of the tsar and the start of the process of destruction of the Russian Empire many people in Ukraine wished to establish a Ukrainian Republic. During a period of civil war from 1917 to 1923 many factions claiming themselves governments of the newly born republic were formed, each with supporters and opponents. The two most prominent of them were a government inKiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

called the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

(UNR) and a government in Kharkov called the Ukrainian Soviet Republic

The Ukrainian Soviet Republic (russian: Украинская Советская Республика, translit= Ukrainskaya Sovetskaya Respublika) was one of the earlier Soviet Ukrainian quasi-state formations (Ukrainian People's Republic of S ...

(USR). The Kiev-based UNR was internationally recognized and supported by the Central powers following the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russia's ...

, whereas the Kharkov-based USR was solely supported by the Soviet Russian forces, while neither the UNR nor the USR were supported by the White Russian forces that remained.

The conflict between the two competing governments, known as the Ukrainian–Soviet War

The Ukrainian–Soviet War ( uk, радянсько-українська війна, translit=radiansko-ukrainska viina) was an armed conflict from 1917 to 1921 between the Ukrainian People's Republic and the Bolsheviks ( Soviet Ukraine and ...

, was part of the ongoing Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

, as well as a struggle for national independence, which ended with the territory of pro-independence Ukrainian People's Republic being annexed into a new Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic, western Ukraine being annexed into the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of the First World ...

, and the newly stable Ukraine becoming a founding member of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

.

The government of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic was founded on 24–25 December 1917. In its publications, it named itself either the Republic of Soviets of Workers', Soldiers' and Peasants' Deputies or the Ukrainian People's Republic of Soviets

The Ukrainian People's Republic of Soviets (russian: Украинская Народная Республика Советов, translit=Ukrainskaya Narodnaya Respublika Sovjetov) was a short-lived (1917–1918) Soviet republic of the Russian S ...

. The 1917 republic was only recognised by another non-recognised country, the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. With the signing of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty, it was ultimately defeated by mid-1918 and eventually dissolved. The last session of the government took place in the city of Taganrog

Taganrog ( rus, Таганрог, p=təɡɐnˈrok) is a port city in Rostov Oblast, Russia, on the north shore of the Taganrog Bay in the Sea of Azov, several kilometers west of the mouth of the Don River. Population:

History of Taganrog

...

.

In July 1918, the former members of the government formed the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Ukraine, the constituent assembly of which took place in Moscow. With the defeat of the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

Russia resumed its hostilities towards the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

fighting for Ukrainian independence and organised another Soviet government in Kursk

Kursk ( rus, Курск, p=ˈkursk) is a city and the administrative center of Kursk Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Kur, Tuskar, and Seym rivers. The area around Kursk was the site of a turning point in the Soviet–German str ...

, Russia. On 10 March 1919, according to the 3rd Congress of Soviets in Ukraine (conducted 6–10 March 1919) the name of the state was changed to the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic.

Founding: 1917–1922

After theRussian Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

, several factions sought to create an independent Ukrainian state, alternately cooperating and struggling against each other. Numerous more or less socialist-oriented factions participated in the formation of the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

among which were Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, Mensheviks

The Mensheviks (russian: меньшевики́, from меньшинство 'minority') were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

The factions eme ...

, Socialists-Revolutionaries, and many others. The most popular faction was initially the local Socialist Revolutionary Party

The Socialist Revolutionary Party, or the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries (the SRs, , or Esers, russian: эсеры, translit=esery, label=none; russian: Партия социалистов-революционеров, ), was a major politi ...

that composed the local government together with Federalists and Mensheviks.

Immediately after the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

in Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, Bolsheviks instigated the Kiev Bolshevik Uprising to support the Revolution and secure Kiev. Due to a lack of adequate support from the local population and anti-revolutionary Central Rada, however, the Kiev Bolshevik group split. Most moved to Kharkov

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

and received the support of the eastern Ukrainian cities and industrial centers. Later, this move was regarded as a mistake by some of the People's Commissars

Commissar (or sometimes ''Kommissar'') is an English language, English transliteration of the Russian language, Russian (''komissar''), which means 'commissary'. In English, the transliteration ''commissar'' often refers specifically to the pol ...

(Yevgenia Bosch

Yevgenia Bogdanovna; russian: Го́тлибовна) Bosch; russian: Евге́ния Богда́новна Бош; german: Jewgenija Bogdanowna Bosch ( née Meisch ; – 5 January 1925) was a Ukrainian Bolshevik revolutionary, politician, ...

). They issued an ultimatum to the Central Rada on 17 December to recognise the Soviet government of which the Rada was very critical. The Bolsheviks convened a separate congress and declared the first Soviet Republic of Ukraine on 24 December 1917 claiming the Central Rada and its supporters outlaws that need to be eradicated. Warfare ensued against the Ukrainian People's Republic for the installation of the Soviet regime in the country and with the direct support from Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

the Ukrainian National forces were practically overrun. The government of Ukraine appealed to foreign capitalists, finding support in the face of the Central Powers as the others refused to recognise it. After the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russia's ...

, the Russian SFSR yielded all the captured Ukrainian territory as the Bolsheviks were forced out of Ukraine. The government of Soviet Ukraine was dissolved after its last session on 20 November 1918.

After re-taking Kharkov in February 1919, a second Soviet Ukrainian government was formed. The government enforced Russian policies that did not adhere to local needs. A group of three thousand workers were dispatched from Russia to take grain from local farms to feed Russian cities and were met with resistance. The Ukrainian language was also censured from administrative and educational use. Eventually fighting both White forces in the east and republic forces in the west, Lenin ordered the liquidation of the second Soviet Ukrainian government in August 1919.

Eventually, after the creation of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine in Moscow, a third Ukrainian Soviet government was formed on 21 December 1919 that initiated new hostilities against Ukrainian nationalists as they lost their military support from the defeated Central Powers. Eventually, the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

ended up controlling much of the Ukrainian territory after the Polish-Soviet Peace of Riga

The Peace of Riga, also known as the Treaty of Riga ( pl, Traktat Ryski), was signed in Riga on 18 March 1921, among Poland, Soviet Russia (acting also on behalf of Soviet Belarus) and Soviet Ukraine. The treaty ended the Polish–Soviet War. ...

. On 30 December 1922, along with the Russian, Byelorussian, and Transcaucasian republics, the Ukrainian SSR was one of the founding members of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

(USSR).

Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

(1917–1920).

File:Europe location UkrSSR 1922.png, Boundaries of the Ukrainian SSR (1922).

File:Ukrainian SSR Document 1937.jpg, Draft constitution of the Soviet Union (1937)

Interwar years: 1922–1939

During the 1920s, a policy of so-called Ukrainization was pursued in the Ukrainian SSR, as part of the general Sovietkorenization

Korenizatsiia or korenization ( rus, коренизация, p=kərʲɪnʲɪˈzatsɨjə, , "indigenization") was an early policy of the Soviet Union for the integration of non-Russian nationalities into the governments of their specific Soviet ...

policy; this involved promoting the use and the social status of the Ukrainian language and the elevation of ethnic Ukrainians to leadership positions (see '' Ukrainization - early years of Soviet Ukraine'' for more details).

In 1932, the aggressive agricultural policies of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

's regime resulted in one of the largest national catastrophes in the modern history for the Ukrainian nation. A famine known as the Holodomor

The Holodomor ( uk, Голодомо́р, Holodomor, ; derived from uk, морити голодом, lit=to kill by starvation, translit=moryty holodom, label=none), also known as the Terror-Famine or the Great Famine, was a man-made famin ...

caused a direct loss of human life estimated between 2.6 millionFrance Meslé, Gilles Pison, Jacques ValliFrance-Ukraine: Demographic Twins Separated by History

''Population and societies'', N°413, juin 2005ce Meslé, Jacques Vallin Mortalité et causes de décès en Ukraine au XXè siècle + CDRom CD online data (partially – ) to 10 million. Some scholars and the World Congress of Free Ukrainians assert that this was an act of genocide. The

International Commission of Inquiry Into the 1932–1933 Famine in Ukraine

The International Commission of Inquiry Into the 1932–1933 Famine in Ukraine was set up in 1984 and was initiated by the World Congress of Free Ukrainians to study and investigate the 1932-1933 man-made famine that killed millions in Ukraine. ...

found no evidence that the famine was part of a preconceived plan to starve Ukrainians, and concluded in 1990 that the famine was caused by a combination of factors, including Soviet policies of compulsory grain requisitions, forced collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

, dekulakization, and Russification

Russification (russian: русификация, rusifikatsiya), or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether involuntarily or voluntarily, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian cultur ...

. The General Assembly of the UN has stopped shy of recognizing the Holodomor as genocide, calling it a "great tragedy" as a compromise between tense positions of United Kingdom, United States, Russia, and Ukraine on the matter, while many nations went on individually to accepted it as such.

World War II: 1939–1945

In September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland and occupied Galician lands inhabited by Ukrainians, Poles and Jews adding it to the territory of the Ukrainian SSR. In 1940, the Soviet Union occupied Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina and the Hertsa region, lands inhabited by Romanians, Ukrainians, Russians, Jews, Bulgarians and Gagauz, adding them to the territory of the Ukrainian SSR and the newly formed

In September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland and occupied Galician lands inhabited by Ukrainians, Poles and Jews adding it to the territory of the Ukrainian SSR. In 1940, the Soviet Union occupied Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina and the Hertsa region, lands inhabited by Romanians, Ukrainians, Russians, Jews, Bulgarians and Gagauz, adding them to the territory of the Ukrainian SSR and the newly formed Moldavian SSR

The Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic ( ro, Republica Sovietică Socialistă Moldovenească, Moldovan Cyrillic: ) was one of the 15 republics of the Soviet Union which existed from 1940 to 1991. The republic was formed on 2 August 1940 ...

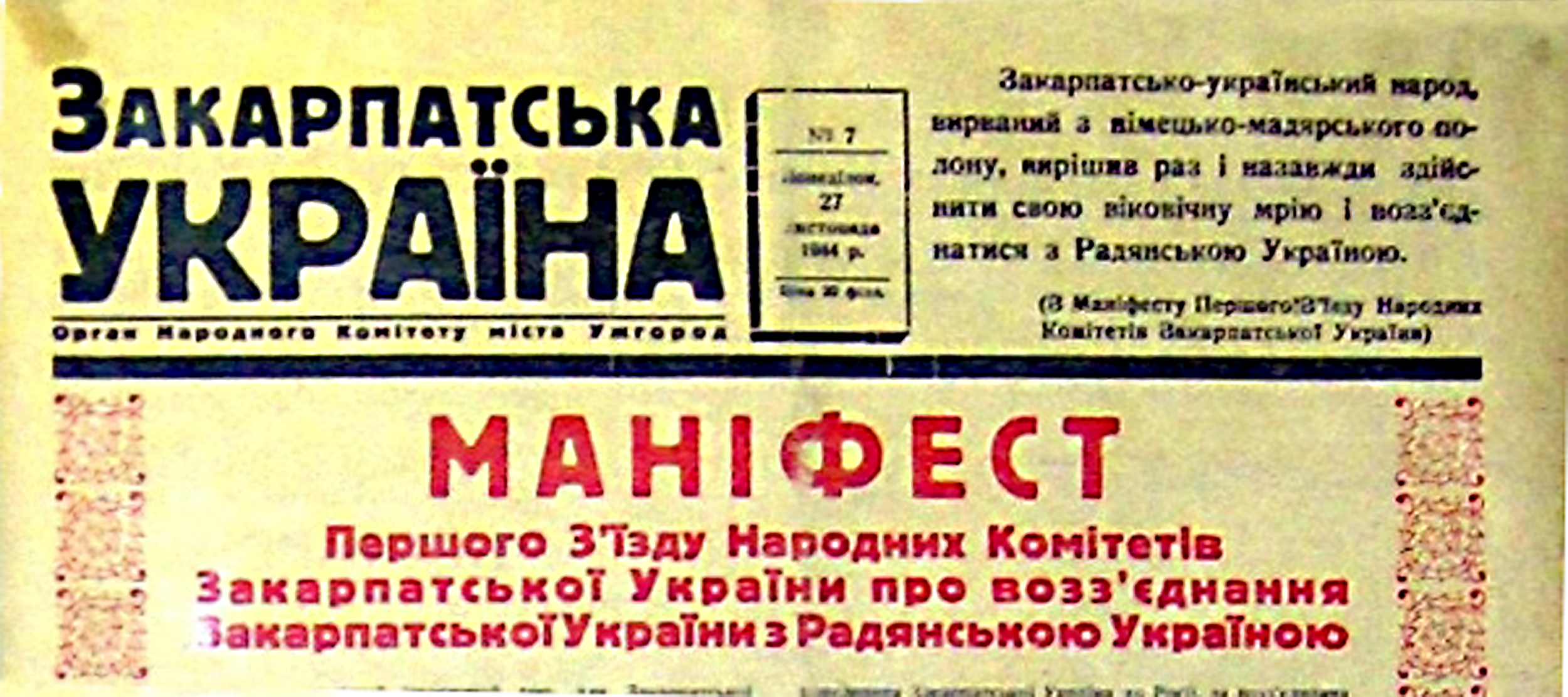

. In 1945, these lands were permanently annexed, and the Transcarpathia region was added as well, by treaty with the post-war administration of Czechoslovakia. Following eastward Soviet retreat in 1941, Ufa became the wartime seat of the Soviet Ukrainian government.

Post-war years: 1945–1953

WhileWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

(called the Great Patriotic War

The Eastern Front of World War II was a Theater (warfare), theatre of conflict between the European Axis powers against the Soviet Union (USSR), Polish Armed Forces in the East, Poland and other Allies of World War II, Allies, which encom ...

by the Soviet government) did not end before May 1945, the Germans were driven out of Ukraine between February 1943 and October 1944. The first task of the Soviet authorities was to reestablish political control over the republic which had been entirely lost during the war. This was an immense task, considering the widespread human and material losses. During World War II the Soviet Union lost about 8.6 million combatants and around 18 million civilians, of these, 6.8 million were Ukrainian civilians and military personnel. Also, an estimated 3.9 million Ukrainians were evacuated to the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

during the war, and 2.2 million Ukrainians were sent to forced labour camps by the Germans.

The material devastation was huge; Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's orders to create "a zone of annihilation" in 1943, coupled with the Soviet military's scorched-earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, military vehicles, transport v ...

policy in 1941, meant Ukraine lay in ruins. These two policies led to the destruction of 28 thousand villages and 714 cities and towns. 85 percent of Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

's city centre was destroyed, as was 70 percent of the city centre of the second-largest city in Ukraine, Kharkov

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

. Because of this, 19 million people were left homeless after the war. The republic's industrial base, as so much else, was destroyed. The Soviet government had managed to evacuate 544 industrial enterprises between July and November 1941, but the rapid German advance led to the destruction or the partial destruction of 16,150 enterprises. 27,910 thousand collective farms

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

, 1,300 machine tractor stations and 872 state farms were destroyed by the Germans.

Izmail

Izmail (, , translit. ''Izmail,'' formerly Тучков ("Tuchkov"); ro, Ismail or ''Smil''; pl, Izmaił, bg, Исмаил) is a city and municipality on the Danube river in Odesa Oblast in south-western Ukraine. It serves as the administ ...

, previously part of Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, a ...

. An agreement was signed by the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

whereby Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia ( rue, Карпатьска Русь, Karpat'ska Rus'; uk, Закарпаття, Zakarpattia; sk, Podkarpatská Rus; hu, Kárpátalja; ro, Transcarpatia; pl, Zakarpacie); cz, Podkarpatská Rus; german: Karpatenukrai ...

was handed over to Ukraine. The territory of Ukraine expanded by and increased its population by an estimated 11 million.

After World War II, amendments to the Constitution of the Ukrainian SSR were accepted, which allowed it to act as a separate subject of international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

in some cases and to a certain extent, remaining a part of the Soviet Union at the same time. In particular, these amendments allowed the Ukrainian SSR to become one of the founding members of the United Nations (UN) together with the Soviet Union and the Byelorussian SSR

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR, or Byelorussian SSR; be, Беларуская Савецкая Сацыялістычная Рэспубліка, Bielaruskaja Savieckaja Sacyjalistyčnaja Respublika; russian: Белор� ...

. This was part of a deal with the United States to ensure a degree of balance in the General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of pres ...

, which, the USSR opined, was unbalanced in favor of the Western Bloc. In its capacity as a member of the UN, the Ukrainian SSR was an elected member of the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the Organs of the United Nations, six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international security, international peace and security, recommending the admi ...

in 1948–1949 and 1984–1985.

Khrushchev and Brezhnev: 1953–1985

When Stalin died on 5 March 1953 the

When Stalin died on 5 March 1953 the collective leadership

A collective is a group of entities that share or are motivated by at least one common issue or interest, or work together to achieve a common objective. Collectives can differ from cooperatives in that they are not necessarily focused upon an ...

of Khrushchev, Georgy Malenkov

Georgy Maximilianovich Malenkov ( – 14 January 1988) was a Soviet politician who briefly succeeded Joseph Stalin as the leader of the Soviet Union. However, at the insistence of the rest of the Presidium, he relinquished control over the p ...

, Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February1890 – 8 November 1986) was a Russian politician and diplomat, an Old Bol ...

and Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolshevik ...

took power and a period of de-Stalinization began. Change came as early as 1953, when officials were allowed to criticise Stalin's policy of russification

Russification (russian: русификация, rusifikatsiya), or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether involuntarily or voluntarily, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian cultur ...

. The Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine

The Communist Party of Ukraine, Abbreviation: KPU, from Ukrainian and Russian "" is a banned political party in Ukraine. It was founded in 1993 as the successor to the Soviet-era Communist Party of Ukraine which was banned in 1991 (accord ...

(CPU) openly criticised Stalin's russification policies in a meeting in June 1953. On 4 June 1953, Aleksey Kirichenko

Aleksey Illarionovich Kirichenko uk, Олексій Іларіонович Кириченко, translit=Oleksii Ilarionovych Kyrychenko ( – 28 December 1975) was a Soviet Ukrainian politician, who was the first ethnic Ukrainian to head the re ...

succeeded Leonid Melnikov as First Secretary of the CPU; this was significant since Kyrychenko was the first ethnic Ukrainian to lead the CPU since the 1920s. The policy of de-Stalinization took two main features, that of centralisation and decentralisation from the centre. In February 1954 the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

(RSFSR) transferred Crimea to Ukraine from the Russians; even if only 22 percent of the Crimean population were ethnic Ukrainian. 1954 also witnessed the massive state-organised celebration of the 300th anniversary of the Union Russia and Ukraine also known as the Pereyaslav Council ( uk, Переяславська рада); the treaty which brought Ukraine under Russian rule three centuries before. The event was celebrated to prove the old and brotherly love between Ukrainians and Russians, and proof of the Soviet Union as a "family of nations"; it was also another way of legitimising Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism is a List of communist ideologies, communist ideology which was the main communist movement throughout the 20th century. Developed by the Bolsheviks, it was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, its Soviet satellite state ...

. On 23 June 1954, the civilian oil tanker

An oil tanker, also known as a petroleum tanker, is a ship designed for the bulk transport of oil or its products. There are two basic types of oil tankers: crude tankers and product tankers. Crude tankers move large quantities of unrefined c ...

'' Tuapse'' of the Black Sea Shipping Company based in Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrat ...

was hijacked by a fleet of Republic of China Navy

The Republic of China Navy (ROCN; ), also called the ROC Navy and colloquially the Taiwan Navy, is the maritime branch of the Republic of China Armed Forces (ROCAF).

The service was formerly commonly just called the Chinese Navy during World W ...

in the high sea

The terms international waters or transboundary waters apply where any of the following types of bodies of water (or their drainage basins) transcend international boundaries: oceans, large marine ecosystems, enclosed or semi-enclosed regiona ...

of ''19°35′N, 120°39′E'', west of Balintang Channel

The Balintang Channel ( ) is the small waterway that separates the Batanes and Babuyan Islands, both of which belong to the Philippines, in the Luzon Strait.

Notable events 1944 incident

During July 1944, the Imperial Japanese Navy cargo submarin ...

near Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, whereas the 49 Ukrainian, Russian and Moldovan crew were detained by the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

regime in various terms up to 34 years in captivity with 3 deaths.

The "Thaw"the policy of deliberate liberalisationwas characterised by four points: amnesty for all those convicted of state crime during the war or the immediate post-war years; amnesties for one-third of those convicted of state crime during Stalin's rule; the establishment of the first Ukrainian mission to the United Nations in 1958; and the steady increase of Ukrainians in the rank of the CPU and government of the Ukrainian SSR. Not only were the majority of CPU Central Committee and Politburo members ethnic Ukrainians, three-quarters of the highest ranking party and state officials were ethnic Ukrainians too. The policy of partial Ukrainisation also led to a cultural thaw within Ukraine.

In October 1964, Khrushchev was deposed by a joint Central Committee and Politburo plenum and succeeded by another collective leadership, this time led by Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union between 1964 and ...

, born in Ukraine, as First Secretary and Alexei Kosygin

Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin ( rus, Алексе́й Никола́евич Косы́гин, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ kɐˈsɨɡʲɪn; – 18 December 1980) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as the Prem ...

as Chairman of the Council of Ministers. Brezhnev's rule would be marked by social and economic stagnation, a period often referred to as the Era of Stagnation. The new regime introduced the policy of ''rastsvet'', ''sblizhenie'' and ''sliianie'' ("flowering", "drawing together" and "merging"/"fusion"), which was the policy of uniting the different Soviet nationalities into one Soviet nationality by merging the best elements of each nationality into the new one. This policy turned out to be, in fact, the reintroduction of the russification policy. The reintroduction of this policy can be explained by Khrushchev's promise of communism in 20 years

"Communism in 20 years" was a slogan put forth by Nikita Khrushchev at the 22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1961. Khrushchev's quote from his speech at the Congress was from this phrase: "We are strictly guided by scient ...

; the unification of Soviet nationalities would take place, according to Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

, when the Soviet Union reached the final stage of communism, also the final stage of human development. Some all-Union Soviet officials were calling for the abolition of the "pseudosovereign" Soviet republics, and the establishment of one nationality. Instead of introducing the ideologic concept of the ''Soviet Nation'', Brezhnev at the 24th Party Congress talked about "a new historical community of people – the Soviet people", and introduced the ideological tenant of Developed socialism, which postponed communism. When Brezhnev died in 1982, his position of General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

was succeeded by Yuri Andropov, who died quickly after taking power. Andropov was succeeded by Konstantin Chernenko

Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko uk, Костянтин Устинович Черненко, translit=Kostiantyn Ustynovych Chernenko (24 September 1911 – 10 March 1985) was a Soviet politician and the seventh General Secretary of the Comm ...

, who ruled for little more than a year. Chernenko was succeeded by Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985.

Gorbachev and dissolution: 1985–1991

Gorbachev's policies of '' perestroika'' and ''

Gorbachev's policies of '' perestroika'' and ''glasnost

''Glasnost'' (; russian: link=no, гласность, ) has several general and specific meanings – a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information, the inadmissibility of hushing up problems, ...

'' (English: ''restructuring'' and ''openness'') failed to reach Ukraine as early as other Soviet republics because of Volodymyr Shcherbytsky

Volodymyr Vasylyovych Shcherbytsky, russian: Влади́мир Васи́льевич Щерби́цкий; ''Vladimir Vasilyevich Shcherbitsky'', (17 February 1918 — 16 February 1990) was a Ukrainian Soviet politician. He was First Sec ...

, a conservative communist appointed by Brezhnev and the First Secretary of the Ukrainian Communist Party, who resigned from his post in 1989. The Chernobyl disaster

The Chernobyl disaster was a nuclear accident that occurred on 26 April 1986 at the No. 4 nuclear reactor, reactor in the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, near the city of Pripyat in the north of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Ukrainia ...

of 1986, the russification policies, and the apparent social and economic stagnation led several Ukrainians to oppose Soviet rule. Gorbachev's policy of ''perestroika'' was also never introduced into practice, 95 percent of industry and agriculture was still owned by the Soviet state in 1990. The talk of reform, but the lack of introducing reform into practice, led to confusion which in turn evolved into opposition to the Soviet state itself. The policy of ''glasnost'', which ended state censorship, led the Ukrainian diaspora to reconnect with their compatriots in Ukraine, the revitalisation of religious practices by destroying the monopoly of the Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

and led to the establishment of several opposition pamphlets, journals and newspapers.

Following the failed August Coup in Moscow on 19–21 August 1991, the Supreme Soviet of Ukraine

The Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR (Ukrainian: Верховна Рада Української РСР, tr. ''Verkhovna Rada Ukrayins'koyi RSR''; Russian: Верховный Совет Украинской ССР, tr. ''Verkhovnyy Sovet Uk ...

declared independence on 24 August 1991, which renamed the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic to Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian invas ...

. The result of the 1991 independence referendum held on 1 December 1991 proved to be a surprise. An overwhelming majority, 92.3%, voted for independence. The referendum carried in the majority of all oblasts. Notably, the Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a p ...

, which had originally been a territory of the RSFSR until 1954, supported the referendum by a 54 percent majority. Over 80 percent of the population of Eastern Ukraine

Eastern Ukraine or east Ukraine ( uk, Східна Україна, Skhidna Ukrayina; russian: Восточная Украина, Vostochnaya Ukraina) is primarily the territory of Ukraine east of the Dnipro (or Dnieper) river, particularly Khark ...

voted for independence. Ukraine's independence was almost immediately recognized by the international community. Ukraine's new-found independence was the first time in the 20th century that Ukrainian independence had been attempted without either foreign intervention or civil war. In the 1991 Ukrainian presidential election

Presidential elections were held in Ukraine on 1 December 1991,Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p1976 the first direct presidential elections in the country's history. Leonid Kravchuk, the Chairman o ...

62 percent of Ukrainians voted for Leonid Kravchuk

Leonid Makarovych Kravchuk ( uk, Леонід Макарович Кравчук; 10 January 1934 – 10 May 2022) was a Ukrainian politician and the first president of Ukraine, serving from 5 December 1991 until 19 July 1994. In 1992, he signed ...

, who had been vested with presidential powers since the Supreme Soviet's declaration of independence. The secession of the second most powerful republic in the Soviet Union ended any realistic chance of the Soviet Union staying together even on a limited scale.

A week after Kravchuk's victory, on 8 December, he and his Russian and Belarusian counterparts signed the Belovezh Accords, which declared that the Soviet Union had effectively ceased to exist and forming the Commonwealth of Independent States

The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) is a regional intergovernmental organization in Eurasia. It was formed following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. It covers an area of and has an estimated population of 239,796,010. ...

as a replacement. They were joined by eight of the remaining 12 republics (all except Georgia) on 21 December in signing the Alma-Ata Protocol, which reiterated that the Soviet Union had ceased to exist. The Soviet Union formally dissolved on 26 December.

Politics and government

The Ukrainian SSR's system of government was based on a one-partycommunist system

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

ruled by the Communist Party of Ukraine

The Communist Party of Ukraine, Abbreviation: KPU, from Ukrainian and Russian "" is a banned political party in Ukraine. It was founded in 1993 as the successor to the Soviet-era Communist Party of Ukraine which was banned in 1991 (accord ...

, a branch of the Communist Party of Soviet Union (KPSS). The republic was one of 15 constituent republics composing the Soviet Union from its entry into the union in 1922 until its dissolution in 1991. All of the political power and authority in the USSR was in the hands of Communist Party authorities, with little real power being concentrated in official government bodies and organs. In such a system, lower-level authorities directly reported to higher level authorities and so on, with the bulk of the power being held at the highest echelons of the Communist Party.

Originally, the legislative authority was vested in the Congress of Soviets of Ukraine, whose Central Executive Committee was for many years headed by Grigory Petrovsky. Soon after publishing a Stalinist constitution, the Congress of Soviets was transformed into the

Originally, the legislative authority was vested in the Congress of Soviets of Ukraine, whose Central Executive Committee was for many years headed by Grigory Petrovsky. Soon after publishing a Stalinist constitution, the Congress of Soviets was transformed into the Supreme Soviet

The Supreme Soviet (russian: Верховный Совет, Verkhovny Sovet, Supreme Council) was the common name for the legislative bodies (parliaments) of the Soviet socialist republics (SSR) in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USS ...

(and the Central Executive Committee into its Presidium), which consisted of 450 deputies. The Supreme Soviet had the authority to enact legislation, amend the constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

, adopt new administrative and territorial boundaries, adopt the budget, and establish political and economic development plans. In addition, parliament also had to authority to elect the republic's executive branch, the Council of Ministers as well as the power to appoint judges to the Supreme Court. Legislative sessions were short and were conducted for only a few weeks out of the year. In spite of this, the Supreme Soviet elected the Presidium, the Chairman, 3 deputy chairmen, a secretary, and couple of other government members to carry out the official functions and duties in between legislative sessions. Chairman of the Presidium was a powerful position in the republic's higher echelons of power, and could nominally be considered the equivalent of head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state (polity), state#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international p ...

, although most executive authority would be concentrated in the Communist Party's politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the executive committee for communist parties. It is present in most former and existing communist states.

Names

The term "politburo" in English comes from the Russian ''Politbyuro'' (), itself a contractio ...

and its First Secretary.

Full universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political sta ...

was granted for all eligible citizens aged 18 and over, excluding prisoners and those deprived of freedom. Although they could not be considered free and were of a symbolic nature, elections to the Supreme Soviet were contested every five years. Nominees from electoral districts from around the republic, typically consisting of an average of 110,000 inhabitants, were directly chosen by party authorities, providing little opportunity for political change, since all political authority was directly subordinate to the higher level above it.

With the beginning of Soviet General Secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the organization. The term is derive ...

Mikhail Gorbachev's '' perestroika'' reforms towards the mid-late 1980s, electoral reform laws were passed in 1989, liberalising the nominating procedures and allowing multiple candidates to stand for election in a district. Accordingly, the first relatively free elections in the Ukrainian SSR were contested in March 1990. 111 deputies from the Democratic Bloc, a loose association of small pro-Ukrainian and pro-sovereignty parties and the instrumental People's Movement of Ukraine (colloquially known as ''Rukh'' in Ukrainian) were elected to the parliament. Although the Communist Party retained its majority with 331 deputies, large support for the Democratic Bloc demonstrated the people's distrust of the Communist authorities, which would eventually boil down to Ukrainian independence in 1991.

Ukraine is the legal successor of the Ukrainian SSR and it stated to fulfill "those rights and duties pursuant to international agreements of Union SSR which do not contradict the Constitution of Ukraine

The Constitution of Ukraine ( uk, Конституція України, translit=Konstytutsiia Ukrainy) is the fundamental law of Ukraine. The constitution was adopted and ratified at the 5th session of the '' Verkhovna Rada'', the parliament ...

and interests of the Republic" on 5 October 1991. After Ukrainian independence the Ukrainian SSR's parliament was changed from ''Supreme Soviet'' to its current name Verkhovna Rada

The Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine ( uk, Верхо́вна Ра́да Украї́ни, translit=, Verkhovna Rada Ukrainy, translation=Supreme Council of Ukraine, Ukrainian abbreviation ''ВРУ''), often simply Verkhovna Rada or just Rada, is the ...

, the Verkhovna Rada is still Ukraine's parliament. Ukraine also has refused to recognize exclusive Russian claims to succession of the Soviet Union and claimed such status for Ukraine as well, which was stated in Articles 7 and 8 of On Legal Succession of Ukraine, issued in 1991. Following independence, Ukraine has continued to pursue claims against the Russian Federation in foreign courts, seeking to recover its share of the foreign property that was owned by the Soviet Union. It also retained its seat in the United Nations, held since 1945.

Foreign relations

On the international front, the Ukrainian SSR, along with the rest of the 15 republics, had virtually no say in their own foreign affairs. It is, however, important to note that in 1944 the Ukrainian SSR was permitted to establish bilateral relations with countries and maintain its own standing army. This clause was used to permit the republic's membership in the United Nations, alongside the Belorussian SSR. Accordingly, representatives from the "Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic" and 50 other nations founded the UN on 24 October 1945. In effect, this provided the Soviet Union (a permanentSecurity Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

member with veto powers) with another two votes in the General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of pres ...

. The latter aspect of the 1944 clauses, however, was never fulfilled and the republic's defense matters were managed by the Soviet Armed Forces

The Soviet Armed Forces, the Armed Forces of the Soviet Union and as the Red Army (, Вооружённые Силы Советского Союза), were the armed forces of the Russian SFSR (1917–1922), the Soviet Union (1922–1991), and th ...

and the Defense Ministry. Another right that was granted but never used until 1991 was the right of the Soviet republics to secede from the union, which was codified in each of the Soviet constitutions. Accordingly, Article 69 of the Constitution of the Ukrainian SSR stated: "The Ukrainian SSR retains the right to willfully secede from the USSR." However, a republic's theoretical secession from the union was virtually impossible and unrealistic in many ways until after Gorbachev's perestroika reforms.

The Ukrainian SSR was a member of the UN Economic and Social Council

The United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC; french: links=no, Conseil économique et social des Nations unies, ) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations, responsible for coordinating the economic and social fields ...

, UNICEF

UNICEF (), originally called the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund in full, now officially United Nations Children's Fund, is an agency of the United Nations responsible for providing humanitarian and developmental aid t ...

, International Labour Organization

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency whose mandate is to advance social and economic justice by setting international labour standards. Founded in October 1919 under the League of Nations, it is the first and o ...

, Universal Postal Union

The Universal Postal Union (UPU, french: link=no, Union postale universelle), established by the Treaty of Bern of 1874, is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) that coordinates postal policies among member nations, in addition to ...

, World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level o ...

, UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. I ...

, International Telecommunication Union

The International Telecommunication Union is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for many matters related to information and communication technologies. It was established on 17 May 1865 as the International Telegraph Unio ...

, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe

The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (ECE or UNECE) is one of the five regional commissions under the jurisdiction of the United Nations Economic and Social Council. It was established in order to promote economic cooperation and i ...

, World Intellectual Property Organization

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO; french: link=no, Organisation mondiale de la propriété intellectuelle (OMPI)) is one of the 15 specialized agencies of the United Nations (UN). Pursuant to the 1967 Convention Establishin ...

and the International Atomic Energy Agency

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was established in 1 ...

. It was not separately a member of the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republi ...

, Comecon

The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (, ; English abbreviation COMECON, CMEA, CEMA, or CAME) was an economic organization from 1949 to 1991 under the leadership of the Soviet Union that comprised the countries of the Eastern Bloc along wi ...

, the World Federation of Trade Unions

The World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU) is an international federation of trade union, trade unions established in 1945. Founded in the immediate aftermath of World War Two, the organization built on the pre-war legacy of the International ...

and the World Federation of Democratic Youth

The World Federation of Democratic Youth (WFDY) is an international youth organization, and has historically characterized itself as left-wing and anti-imperialist. WFDY was founded in London in 1945 as a broad international youth movement, o ...

, and since 1949, the International Olympic Committee

The International Olympic Committee (IOC; french: link=no, Comité international olympique, ''CIO'') is a non-governmental sports organisation based in Lausanne, Switzerland. It is constituted in the form of an association under the Swis ...

.

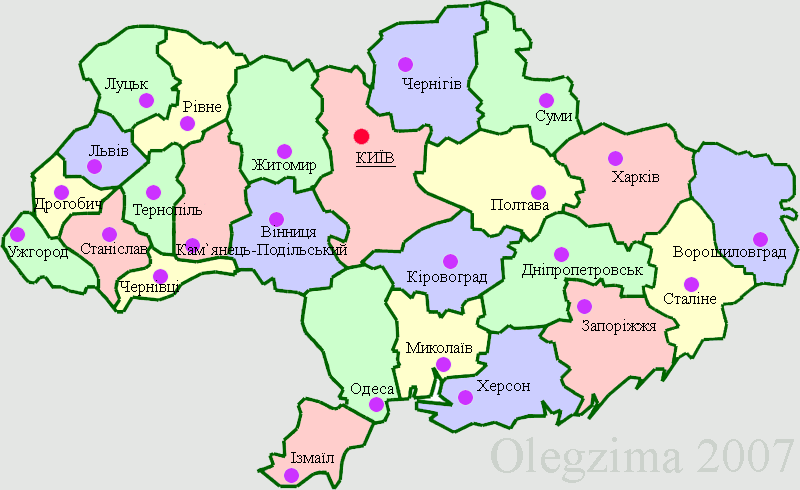

Administrative divisions

Legally, the Soviet Union and its fifteen union republics constituted a

Legally, the Soviet Union and its fifteen union republics constituted a federal system

Federalism is a combined or compound mode of government that combines a general government (the central or "federal" government) with regional governments ( provincial, state, cantonal, territorial, or other sub-unit governments) in a single p ...

, but the country was functionally a highly centralised state, with all major decision-making taking place in the Kremlin

The Kremlin ( rus, Московский Кремль, r=Moskovskiy Kreml', p=ˈmɐˈskofskʲɪj krʲemlʲ, t=Moscow Kremlin) is a fortified complex in the center of Moscow founded by the Rurik dynasty. It is the best known of the kremlins (Ru ...

, the capital and seat of government of the country. The constituent republic were essentially unitary state

A unitary state is a sovereign state governed as a single entity in which the central government is the supreme authority. The central government may create (or abolish) administrative divisions (sub-national units). Such units exercise only th ...

s, with lower levels of power being directly subordinate to higher ones. Throughout its 72-year existence, the administrative divisions of the Ukrainian SSR changed numerous times, often incorporating regional reorganisation and annexation on the part of Soviet authorities during World War II.

The most common administrative division was the oblast

An oblast (; ; Cyrillic (in most languages, including Russian and Ukrainian): , Bulgarian: ) is a type of administrative division of Belarus, Bulgaria, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Ukraine, as well as the Soviet Union and the Kingdom ...

(province), of which there were 25 upon the republic's independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. Provinces were further subdivided into raion

A raion (also spelt rayon) is a type of administrative unit of several post-Soviet states. The term is used for both a type of subnational entity and a division of a city. The word is from the French (meaning 'honeycomb, department'), and is co ...

s (districts) which numbered 490. The rest of the administrative division within the provinces consisted of cities, urban-type settlement

Urban-type settlementrussian: посёлок городско́го ти́па, translit=posyolok gorodskogo tipa, abbreviated: russian: п.г.т., translit=p.g.t.; ua, селище міського типу, translit=selyshche mis'koho typu, ab ...

s, and villages. Cities in the Ukrainian SSR were a separate exception, which could either be subordinate to either the provincial authorities themselves or the district authorities of which they were the administrative center. Two cities, the capital Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

, and Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

in Crimea, treated separately because it housed an underground nuclear submarine base, were designated "cities with special status." This meant that they were directly subordinate to the central Ukrainian SSR authorities and not the provincial authorities surrounding them.

Historical formation

However, the history of administrative divisions in the republic was not so clear cut. At the end of

However, the history of administrative divisions in the republic was not so clear cut. At the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

in 1918, Ukraine was invaded by Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

as the Russian puppet government of the Ukrainian SSR and without official declaration it ignited the Ukrainian–Soviet War

The Ukrainian–Soviet War ( uk, радянсько-українська війна, translit=radiansko-ukrainska viina) was an armed conflict from 1917 to 1921 between the Ukrainian People's Republic and the Bolsheviks ( Soviet Ukraine and ...

. Government of the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

from very start was managed by the Communist Party of Ukraine

The Communist Party of Ukraine, Abbreviation: KPU, from Ukrainian and Russian "" is a banned political party in Ukraine. It was founded in 1993 as the successor to the Soviet-era Communist Party of Ukraine which was banned in 1991 (accord ...

that was created in Moscow and was originally formed out of the Bolshevik organisational centers in Ukraine. Occupying the eastern city of Kharkov

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

, the Soviet forces chose it as the republic's seat of government, colloquially named in the media as "Kharkov – Pervaya Stolitsa (the first capital)" with implication to the era of Soviet regime. Kharkov was also the city where the first Soviet Ukrainian government was created in 1917 with strong support from Russian SFSR authorities. However, in 1934, the capital was moved from Kharkov to Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

, which remains the capital of Ukraine today.

During the 1930s, there were significant numbers of ethnic minorities living within the Ukrainian SSR. National Districts were formed as separate territorial-administrative units within higher-level provincial authorities. Districts were established for the republic's three largest minority groups, which were the Jews, Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 ''Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

, and Poles. Other ethnic groups, however, were allowed to petition the government for their own national autonomy. In 1924 on the territory of Ukrainian SSR was formed the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic

* ro, Proletari din toate țările, uniți-vă! ( Moldovan Cyrillic: )

* uk, Пролетарі всіх країн, єднайтеся!

* russian: Пролетарии всех стран, соединяйтесь!

, title_leader = First Secr ...

. Upon the 1940 conquest of Bessarabia and Bukovina by Soviet troops the Moldavian ASSR was passed to the newly formed Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic ( ro, Republica Sovietică Socialistă Moldovenească, Moldovan Cyrillic: ) was one of the 15 republics of the Soviet Union which existed from 1940 to 1991. The republic was formed on 2 August 1940 ...

, while Budzhak and Bukovina were secured by the Ukrainian SSR. Following the creation of the Ukrainian SSR significant numbers of ethnic Ukrainians found themselves living outside the Ukrainian SSR. In 1920s the Ukrainian SSR was forced to cede several territories to Russia in Severia, Sloboda Ukraine and Azov littoral including such cities like Belgorod

Belgorod ( rus, Белгород, p=ˈbʲeɫɡərət) is a city and the administrative center of Belgorod Oblast, Russia, located on the Seversky Donets River north of the border with Ukraine. Population: Demographics

The population of B ...

, Taganrog

Taganrog ( rus, Таганрог, p=təɡɐnˈrok) is a port city in Rostov Oblast, Russia, on the north shore of the Taganrog Bay in the Sea of Azov, several kilometers west of the mouth of the Don River. Population:

History of Taganrog

...

and Starodub. In the 1920s the administration of the Ukrainian SSR insisted in vain on reviewing the border between the Ukrainian Soviet Republics and the Russian Soviet Republic based on the 1926 First All-Union Census of the Soviet Union that showed that 4.5 millions of Ukrainians were living on Russian territories bordering Ukraine.Unknown Eastern UkraineThe Ukrainian Week

''The Ukrainian Week'' ( uk, Український Тиждень, translit=Ukrainskyi Tyzhden) is an illustrated weekly magazine covering politics, economics and the arts and aimed at the socially engaged Ukrainian-language reader. It provides ...

(14 March 2012) A forced end to Ukrainisation in southern Russian Soviet Republic led to a massive decline of reported Ukrainians in these regions in the 1937 Soviet Census.

Upon signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

, Nazi Germany and Soviet Union partitioned Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

and its Eastern Borderlands were secured by the Soviet buffer republics with Ukraine securing the territory of Eastern Galicia. The Soviet September Polish campaign in Soviet propaganda was portrayed as the Golden September for Ukrainians, given the unification of Ukrainian lands on both banks of Zbruch River, until then the border between the Soviet Union and the Polish communities inhabited by Ukrainian speaking families.

Economy

Before 1945

After 1945

Agriculture

In 1945, agricultural production stood at only 40 percent of the 1940 level, even though the republic's territorial expansion had "increased the amount ofarable land

Arable land (from the la, arabilis, "able to be ploughed") is any land capable of being ploughed and used to grow crops.''Oxford English Dictionary'', "arable, ''adj''. and ''n.''" Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2013. Alternatively, for th ...

". In contrast to the remarkable growth in the industrial sector, agriculture continued in Ukraine, as in the rest of the Soviet Union, to function as the economy's Achilles heel

An Achilles' heel (or Achilles heel) is a weakness in spite of overall strength, which can lead to downfall. While the mythological origin refers to a physical vulnerability, idiomatic references to other attributes or qualities that can lead to ...

. Despite the human toll of Collectivisation of agriculture in the Soviet Union, especially in Ukraine, Soviet planners still believed in the effectiveness of collective farming. The old system was reestablished; the numbers of collective farm

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

s in Ukraine increased from 28 thousand in 1940 to 33 thousand in 1949, comprising 45 million hectares; the numbers of state farm

State Farm Insurance is a large group of mutual insurance companies throughout the United States with corporate headquarters in Bloomington, Illinois.

Overview

State Farm is the largest property and casualty insurance provider, and the la ...

s barely increased, standing at 935 in 1950, comprising 12.1 million hectares. By the end of the Fourth Five-Year Plan (in 1950) and the Fifth Five-Year Plan (in 1955), agricultural output still stood far lower than the 1940 level. The slow changes in agriculture can be explained by the low productivity in collective farms, and by bad weather-conditions, which the Soviet planning system could not effectively respond to. Grain for human consumption in the post-war years decreased, this in turn led to frequent and severe food shortages.

The increase of Soviet agricultural production was tremendous, however, the Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...