Soviet political repressions on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Throughout the

'' Znanie — Sila'' magazine, no. 11, 2003 and the information was uncovered about the so-called

In his book, '' Terrorism and Communism: A Reply to Karl Kautsky,'' Trotsky also argued that the reign of terror began with the White Terror under the White Guard forces and the Bolsheviks responded with the Red Terror. There is no consensus among the Western historians on the number of deaths from the Red Terror in

In his book, '' Terrorism and Communism: A Reply to Karl Kautsky,'' Trotsky also argued that the reign of terror began with the White Terror under the White Guard forces and the Bolsheviks responded with the Red Terror. There is no consensus among the Western historians on the number of deaths from the Red Terror in

«Красный террор» в России 1918–1923.

nbsp;— 2-ое изд., доп. — Берлин, 1924 Modern historian Sergei Volkov, assessing the Red Terror as the entire repressive policy of the Bolsheviks during the years of the Civil War (1917–1922), estimates the direct death toll of the Red Terror at 2 million people. Volkov's calculations, however, do not appear to have been confirmed by other major scholars.

Collectivization in the

Collectivization in the

Nikolai Klyuev was the first known homosexual to suffer from Soviet repressions. The poet was accused of writing love lyrics that "were written from a male person to a male person." In February 1934, Klyuyev was arrested in his apartment on charges of "composing and distributing counter-revolutionary literary works", and in 1937 he was shot.

In later times, the most famous victim of the Soviet repression against the LGBT community was a film director

Nikolai Klyuev was the first known homosexual to suffer from Soviet repressions. The poet was accused of writing love lyrics that "were written from a male person to a male person." In February 1934, Klyuyev was arrested in his apartment on charges of "composing and distributing counter-revolutionary literary works", and in 1937 he was shot.

In later times, the most famous victim of the Soviet repression against the LGBT community was a film director

Estimates of the number of deaths attributable specifically to

Estimates of the number of deaths attributable specifically to

A Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Political Repression (День памяти жертв политических репрессий) has been officially held on 30 October in Russia since 1991. It is also marked in other former Soviet republics except Ukraine, which has its own annual Day of Remembrance for the victims of political repressions by the Soviet regime, held each year on the third Sunday of May.

Members of the Memorial society took an active part in such commemorative meetings. Since 2007, Memorial had also organised the day-long "Restoring the Names" ceremony at the Solovetsky Stone in Moscow every 29 October. The organization was banned by the

A Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Political Repression (День памяти жертв политических репрессий) has been officially held on 30 October in Russia since 1991. It is also marked in other former Soviet republics except Ukraine, which has its own annual Day of Remembrance for the victims of political repressions by the Soviet regime, held each year on the third Sunday of May.

Members of the Memorial society took an active part in such commemorative meetings. Since 2007, Memorial had also organised the day-long "Restoring the Names" ceremony at the Solovetsky Stone in Moscow every 29 October. The organization was banned by the

"New directions in Gulag studies: a roundtable discussion,"

Canadian Slavonic Papers 59, no 3-4 (2017) * * * * * Lynne Viola

"New sources on Soviet perpetrators of mass repression: a research note,"

Canadian Slavonic Papers 60, no 3-4 (2018) * * * * *

history of the Soviet Union

The history of the Soviet Union (USSR) (1922–91) began with the ideals of the Russian Bolshevik Revolution and ended in dissolution amidst economic collapse and political disintegration. Established in 1922 following the Russian Civil War, ...

, tens of millions of people suffered political repression

Political repression is the act of a state entity controlling a citizenry by force for political reasons, particularly for the purpose of restricting or preventing the citizenry's ability to take part in the political life of a society, thereby ...

, which was an instrument of the state since the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

. It culminated during the Stalin era

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

, then declined, but it continued to exist during the "Khrushchev Thaw

The Khrushchev Thaw (, or simply ''ottepel'')William Taubman, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era, London: Free Press, 2004 is the period from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s when Political repression in the Soviet Union, repression and Censorship in ...

", followed by increased persecution of Soviet dissidents

Soviet dissidents were people who disagreed with certain features of Soviet ideology or with its entirety and who were willing to speak out against them. The term ''dissident'' was used in the Soviet Union (USSR) in the period from the mid-1960 ...

during the Brezhnev era, and it did not cease to exist until late in Mikhail Gorbachev's rule when it was ended in keeping with his policies of glasnost

''Glasnost'' ( ; , ) is a concept relating to openness and transparency. It has several general and specific meanings, including a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information and the inadmissi ...

and perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

.

Origins and early Soviet times

Secret police had a long history in Tsarist Russia.Ivan the Terrible

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (; – ), commonly known as Ivan the Terrible,; ; monastic name: Jonah. was Grand Prince of Moscow, Grand Prince of Moscow and all Russia from 1533 to 1547, and the first Tsar of all Russia, Tsar and Grand Prince of all R ...

used the Oprichina, while more recently the Third Section and Okhrana

The Department for the Protection of Public Safety and Order (), usually called the Guard Department () and commonly abbreviated in modern English sources as the Okhrana ( rus , Охрана, p=ɐˈxranə, a=Ru-охрана.ogg, t= The Guard) w ...

existed.

Early on, the Leninist

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vangu ...

view of the class conflict

In political science, the term class conflict, class struggle, or class war refers to the economic antagonism and political tension that exist among social classes because of clashing interests, competition for limited resources, and inequali ...

and the resulting notion of the dictatorship of the proletariat provided the theoretical basis of the repressions. Its legal basis was formalized into the Article 58 in the code of the Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

and similar articles for other Soviet republics.

According to the Marxist historian Marcel Liebman

Marcel Liebman (7 July 1929 – 1 March 1986) was a Belgian Marxist historian of political sociology and theory, active at the Université libre de Bruxelles and Vrije Universiteit Brussel.

Life

A historian of socialism and of communism, h ...

, Lenin's wartime measures such as banning opposition parties was prompted by the fact that several political parties either took up arms against the new Soviet government

The Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was the executive and administrative organ of the highest body of state authority, the All-Union Supreme Soviet. It was formed on 30 December 1922 and abolished on 26 December 199 ...

, or participated in sabotage, collaborated with the deposed Tsarists, or made assassination attempts against Lenin and other Bolshevik leaders. Liebman noted that opposition parties such as the Cadets who were democratically elected to the Soviets in some areas, then proceeded to use their mandate to welcome in Tsarist and foreign capitalist military forces. In one incident in Baku, the British military, once invited in, proceeded to execute members of the Bolshevik Party who had peacefully stood down from the Soviet when they failed to win the elections. As a result, the Bolsheviks banned each opposition party when it turned against the Soviet government. In some cases, bans were lifted. This banning of parties did not have the same repressive character as later bans enforced under the Stalinist

Stalinism (, ) is the totalitarian means of governing and Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1927 to 1953 by dictator Joseph Stalin and in Soviet satellite states between 1944 and 1953. Stalinism in ...

regime. Trotsky also argued that he and Lenin had intended to lift the ban on the opposition parties

Parliamentary opposition is a form of political opposition to a designated government, particularly in a Westminster-based parliamentary system. This article uses the term ''government'' as it is used in Parliamentary systems, i.e. meaning ''th ...

such as the Mensheviks

The Mensheviks ('the Minority') were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903. Mensheviks held more moderate and reformist ...

and Socialist Revolutionaries as soon as the economic and social conditions of Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

had improved.

At times, the repressed were called the enemies of the people

The terms enemy of the people and enemy of the nation are designations for the political opponents and the social-class opponents of the power group within a larger social unit, who, thus identified, can be subjected to political repression. ...

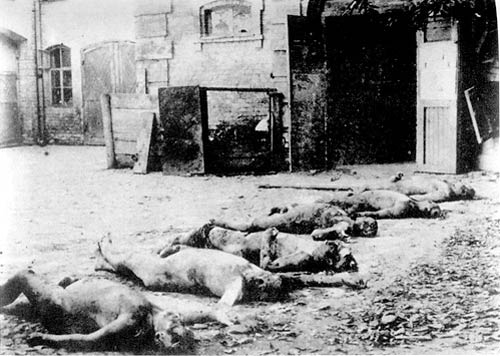

. Punishments by the state included summary execution

In civil and military jurisprudence, summary execution is the putting to death of a person accused of a crime without the benefit of a free and fair trial. The term results from the legal concept of summary justice to punish a summary offense, a ...

s, sending innocent people to Gulag

The Gulag was a system of Labor camp, forced labor camps in the Soviet Union. The word ''Gulag'' originally referred only to the division of the Chronology of Soviet secret police agencies, Soviet secret police that was in charge of runnin ...

, forced resettlement

Population transfer or resettlement is a type of mass migration that is often imposed by a state policy or international authority. Such mass migrations are most frequently spurred on the basis of ethnicity or religion, but they also occur d ...

, and stripping of citizen's rights. Repression was conducted by the Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fsʲɪrɐˈsʲijskəjə tɕrʲɪzvɨˈtɕæjnəjə kɐˈmʲisʲɪjə, links=yes), ...

secret police and its successors, and other state organs. Periods of increased repression include the Red Terror

The Red Terror () was a campaign of political repression and Mass killing, executions in Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Soviet Russia which was carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police ...

, Collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

, the Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

s, the Doctors' Plot

The "doctors' plot" () was a Soviet state-sponsored anti-intellectual and anti-cosmopolitan campaign based on a conspiracy theory that alleged an anti-Soviet cabal of prominent medical specialists, including some of Jewish ethnicity, intend ...

, and others. The secret police

image:Putin-Stasi-Ausweis.png, 300px, Vladimir Putin's secret police identity card, issued by the East German Stasi while he was working as a Soviet KGB liaison officer from 1985 to 1989. Both organizations used similar forms of repression.

Secre ...

forces conducted massacres of prisoners on numerous occasions. Repression took place in the Soviet republics and in the territories occupied by the Soviet Army

The Soviet Ground Forces () was the land warfare service branch of the Soviet Armed Forces from 1946 to 1992. It was preceded by the Red Army.

After the Soviet Union ceased to exist in December 1991, the Ground Forces remained under th ...

during and following World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, including the Baltic states

The Baltic states or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term encompassing Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, and the OECD. The three sovereign states on the eastern co ...

and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

.

State repression led to incidents of popular resistance, such as the Tambov peasant rebellion (1920–1921), the Kronstadt rebellion

The Kronstadt rebellion () was a 1921 insurrection of Soviet sailors, Marines, naval infantry, and civilians against the Bolsheviks, Bolshevik government in the Russian port city of Kronstadt. Located on Kotlin Island in the Gulf of Finland, ...

(1921), and the Vorkuta Uprising (1953); the Soviet authorities suppressed such resistance with overwhelming military force and brutality. During the Tambov rebellion, Mikhail Tukhachevsky

Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevsky ( rus, Михаил Николаевич Тухачевский, Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevskiy, p=tʊxɐˈtɕefskʲɪj; – 12 June 1937), nicknamed the Red Napoleon, was a Soviet general who was prominen ...

(chief Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

commander in the area) authorized Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

military forces to use chemical weapons

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as ...

against villages with civilian population and rebels. Publications in local Communist newspapers openly glorified liquidations of "bandits" with the poison gas. The Internal Troops of the Cheka and the Red Army practiced the terror tactics of taking and executing numerous hostages, often in connection with desertions of forcefully mobilized peasants. According to Orlando Figes

Orlando Guy Figes (; born 20 November 1959) is a British and German historian and writer. He was a professor of history at Birkbeck College, University of London, where he was made Emeritus Professor on his retirement in 2022.

Figes is known f ...

, more than 1 million people deserted from the Red Army in 1918, around 2 million people deserted in 1919, and almost 4 million deserters escaped from the Red Army in 1921.

In 1919, 612 "hardcore" deserters of the total 837,000 draft dodgers and deserters

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or Military base, post without permission (a Pass (military), pass, Shore leave, liberty or Leave (U.S. military), leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with u ...

were executed following Trotsky's dracionan measures. According to Figes, "a majority of deserters (most registered as "weak-willed") were handed back to the military authorities, and formed into units for transfer to one of the rear armies or directly to the front". Even those registered as "malicious" deserters were returned to the ranks when the demand for reinforcements became desperate". Forges also noted that the Red Army instituted amnesty

Amnesty () is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power officially forgiving certain classes of people who are subject to trial but have not yet be ...

weeks to prohibit punitive measures against desertion which encouraged the voluntary return of 98,000-132,000 deserters to the army.

For a long time historians assumed that the destruction of the officer cadre of the Red Army happened during Stalin's Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

. However new data that emerged on the break of the 21st century radically changed this perception, Операция «Весна»'' Znanie — Sila'' magazine, no. 11, 2003 and the information was uncovered about the so-called

Vesna Case

The "Vesna" Case (), also Operation Vesna of 1930-1931 was a massive series of Soviet repressions targeting former officers and generals of the Russian Imperial Army who had served in the Red Army and Soviet Navy, a major purge of the Red Arm ...

, a massive series of Soviet repressions targeting former officers and generals of the Russian Imperial Army who had served in the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

and Soviet Navy

The Soviet Navy was the naval warfare Military, uniform service branch of the Soviet Armed Forces. Often referred to as the Red Fleet, the Soviet Navy made up a large part of the Soviet Union's strategic planning in the event of a conflict with t ...

, a major purge

In history, religion and political science, a purge is a position removal or execution of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, another, their team leaders, or society as a whole. A group undertaking such an ...

of the Red Army during 1930-1931.

Red Terror

In his book, '' Terrorism and Communism: A Reply to Karl Kautsky,'' Trotsky also argued that the reign of terror began with the White Terror under the White Guard forces and the Bolsheviks responded with the Red Terror. There is no consensus among the Western historians on the number of deaths from the Red Terror in

In his book, '' Terrorism and Communism: A Reply to Karl Kautsky,'' Trotsky also argued that the reign of terror began with the White Terror under the White Guard forces and the Bolsheviks responded with the Red Terror. There is no consensus among the Western historians on the number of deaths from the Red Terror in Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

. One source gives estimates of 28,000 executions per year from December 1917 to February 1922. Estimates for the number of people shot during the initial period of the Red Terror are at least 10,000. Estimates for the whole period go for a low of 50,000Stone, Bailey (2013). ''The Anatomy of Revolution Revisited: A Comparative Analysis of England, France, and Russia''. Cambridge University Press. p. 335. to highs of 140,000 and 200,000 executed. Most estimations for the number of executions in total put the number at about 100,000. However, social scientist Nikolay Zayats from the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus

The National Academy of Sciences of Belarus (NASB; ; , , ) is the national academy of Belarus.

History Inbelkult - predecessor to the Academy

The Academy has its origins in the Institute of Belarusian Culture (Inbelkult), a Belarusian acade ...

has argued that the figures have been greatly exaggerated due to White Army

The White Army, also known as the White Guard, the White Guardsmen, or simply the Whites, was a common collective name for the armed formations of the White movement and Anti-Sovietism, anti-Bolshevik governments during the Russian Civil War. T ...

propaganda.

According to Vadim Erlikhman's investigation, the number of the Red Terror's victims is at least 1,200,000 people. According to Robert Conquest

George Robert Acworth Conquest (15 July 19173 August 2015) was a British and American historian, poet, novelist, and propagandist. He was briefly a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain but later wrote several books condemning commun ...

, a total of 140,000 people were shot in 1917–1922. Candidate of Historical Sciences Nikolay Zayats states that the number of people shot by the Cheka in 1918–1922 is about 37,300 people, shot in 1918–1921 by the verdicts of the tribunals—14,200, i.e. about 50,000–55,000 people in total, although executions and atrocities were not limited to the Cheka, having been organized by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

as well.

In 1924, anti-Bolshevik Popular Socialist Sergei Melgunov (1879–1956) published a detailed account on the Red Terror in Russia, where he cited Professor Charles Saroléa's estimates of 1,766,188 deaths from the Bolshevik policies. He questioned the accuracy of the figures, but endorsed Saroléa's "characterisation of terror in Russia", stating it matches reality.Часть IV. На гражданской войнe. // '' Sergei Melgunov'«Красный террор» в России 1918–1923.

nbsp;— 2-ое изд., доп. — Берлин, 1924 Modern historian Sergei Volkov, assessing the Red Terror as the entire repressive policy of the Bolsheviks during the years of the Civil War (1917–1922), estimates the direct death toll of the Red Terror at 2 million people. Volkov's calculations, however, do not appear to have been confirmed by other major scholars.

Collectivization

Collectivization in the

Collectivization in the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

was a policy, pursued between 1928 and 1933, to consolidate individual land and labour into collective farms (, ''kolkhoz

A kolkhoz ( rus, колхо́з, a=ru-kolkhoz.ogg, p=kɐlˈxos) was a form of collective farm in the Soviet Union. Kolkhozes existed along with state farms or sovkhoz. These were the two components of the socialized farm sector that began to eme ...

'', plural ''kolkhozy''). The Soviet leaders were confident that the replacement of individual peasant farms by kolkhozy would immediately increase food supplies for the urban population, the supply of raw materials for processing industry, and agricultural exports generally. Collectivization was thus regarded as the solution to the crisis in agricultural distribution (mainly in grain deliveries) that had developed since 1927 and was becoming more acute as the Soviet Union pressed ahead with its ambitious industrialization program. As the peasantry, with the exception of the poorest part, resisted the collectivization policy, the Soviet government resorted to harsh measures to force the farmers to collectivize. In his conversation with Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, Joseph Stalin gave his estimate of the number of "kulak

Kulak ( ; rus, кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈɫak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned over ...

s" who were repressed for resisting Soviet collectivization

The Soviet Union introduced collective farming, collectivization () of its agricultural sector between 1928 and 1940. It began during and was part of the First five-year plan (Soviet Union), first five-year plan. The policy aimed to integra ...

as 10 million, including those forcibly deported. Recent historians have estimated the death toll in the range of six to 13 million.

Great Purge

The Great Purge (,transliterated

Transliteration is a type of conversion of a text from one writing system, script to another that involves swapping Letter (alphabet), letters (thus ''wikt:trans-#Prefix, trans-'' + ''wikt:littera#Latin, liter-'') in predictable ways, such as ...

''Bolshoy terror'', ''The Great Terror'') was a series of campaigns of political repression

Political repression is the act of a state entity controlling a citizenry by force for political reasons, particularly for the purpose of restricting or preventing the citizenry's ability to take part in the political life of a society, thereby ...

and persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these term ...

in the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

orchestrated by Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

in 1937–1938.Figes, 2007: pp. 227–315Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe. By Robert Gellately. 2007. Knopf. 720 pages It involved the purge of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, repression of peasants

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer

A farmer is a person engaged in agriculture, raising living organisms for food or raw materials. The term usually applies to people who do some combination of raising f ...

, deportations of ethnic minorities

The term "minority group" has different meanings, depending on the context. According to common usage, it can be defined simply as a group in society with the least number of individuals, or less than half of a population. Usually a minority g ...

, and the persecution of unaffiliated persons, characterized by widespread police surveillance, widespread suspicion of "saboteurs", imprisonment, and killings. Estimates of the number of deaths associated with the Great Purge run from the official figure of 681,692 to nearly 1,2 million.

LGBT persecution

On September 15, 1933, the deputy head of theOGPU

The Joint State Political Directorate ( rus, Объединённое государственное политическое управление, p=ɐbjɪdʲɪˈnʲɵn(ː)əjə ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)əjə pəlʲɪˈtʲitɕɪskəjə ʊprɐˈv ...

, Genrikh Yagoda

Genrikh Grigoryevich Yagoda (, born Yenokh Gershevich Iyeguda; 7 November 1891 – 15 March 1938) was a Soviet secret police official who served as director of the NKVD, the Soviet Union's security and intelligence agency, from 1934 to 1936. A ...

reported to Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

about the disclosure of the "conspiracy of the homosexual community" in Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

, Leningrad

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

and Kharkiv

Kharkiv, also known as Kharkov, is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city in Ukraine.

. As Yagoda pointed out in the explanatory note, "the conspirators were engaged in the creation of a network of salons and other organized formations, with the subsequent transformation of these associations into direct spy cells".

Stalin ordered "to punish the scumbags" in a demonstrative way, and to introduce a corresponding directive into the legislation. At the first stage, about 130 people were arrested who gave the necessary confessions under torture, and on December 17, 1933, the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR decided to extend criminal liability to "unnatural relationship". The article was added to the Criminal Code of the RSFSR on April 1, 1934 in the section "sexual crimes" under number 154-a. "Voluntary" sexual intercourse between two men was sentenced to three to five years in the camps, and for "cohabitation" with the use of violence - from five to eight.

Nikolai Klyuev was the first known homosexual to suffer from Soviet repressions. The poet was accused of writing love lyrics that "were written from a male person to a male person." In February 1934, Klyuyev was arrested in his apartment on charges of "composing and distributing counter-revolutionary literary works", and in 1937 he was shot.

In later times, the most famous victim of the Soviet repression against the LGBT community was a film director

Nikolai Klyuev was the first known homosexual to suffer from Soviet repressions. The poet was accused of writing love lyrics that "were written from a male person to a male person." In February 1934, Klyuyev was arrested in his apartment on charges of "composing and distributing counter-revolutionary literary works", and in 1937 he was shot.

In later times, the most famous victim of the Soviet repression against the LGBT community was a film director Sergei Parajanov

Sergei Iosifovich Parajanov (January 9, 1924 – July 20, 1990) was a Soviet film director and screenwriter. He is regarded by film critics, film historians and filmmakers to be one of the greatest filmmakers of all time.

Parajanov was born to ...

.

Population transfers

Population transfer in the Soviet Union may be divided into the following broad categories: deportations of "anti-Soviet

Anti-Sovietism or anti-Soviet sentiment are activities that were actually or allegedly aimed against the Soviet Union or government power within the Soviet Union.

Three common uses of the term include the following:

* Anti-Sovietism in inter ...

" categories within the population, who were often classified as " enemies of the workers"; deportations of nationalities; labor force transfer; and organised migrations in opposite directions in order to fill the ethnically cleansed territories. In most cases their destinations were underpopulated and remote areas (see Involuntary settlements in the Soviet Union).

Entire nations and ethnic groups were collectively punished by the Soviet government for their alleged collaboration with the enemy during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. At least nine distinct ethnic-linguistic groups, including ethnic Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The constitution of Germany, implemented in 1949 following the end of World War ...

, ethnic Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

, ethnic Poles, Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars (), or simply Crimeans (), are an Eastern European Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group and nation indigenous to Crimea. Their ethnogenesis lasted thousands of years in Crimea and the northern regions along the coast of the Blac ...

(recognized as genocide), Balkars

Balkars ( or аланла, romanized: alanla or таулула, , 'mountaineers') are a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group in the North Caucasus region, one of the titular nation, titular populations of Kabardino-Balkaria.

Their Karachay-B ...

, Chechens, and Kalmyks

Kalmyks (), archaically anglicised as Calmucks (), are the only Mongolic ethnic group living in Europe, residing in the easternmost part of the European Plain.

This dry steppe area, west of the lower Volga River, known among the nomads as ...

, were deported to remote and unpopulated areas of Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

(see sybirak) and Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

.Conquest, 1986: Koreans

Koreans are an East Asian ethnic group native to the Korean Peninsula. The majority of Koreans live in the two Korean sovereign states of North and South Korea, which are collectively referred to as Korea. As of 2021, an estimated 7.3 m ...

and Romanians

Romanians (, ; dated Endonym and exonym, exonym ''Vlachs'') are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking ethnic group and nation native to Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. Sharing a Culture of Romania, ...

were also deported. Mass operations of the NKVD were needed to deport millions of people, many of whom died. According to various sources, more than 6 million people were deported, with the death toll ranging from 800,000 to 1,500,000 in the USSR only.

Gulag

The Gulag "was the branch of the State Security that operated the penal system of forced labour camps and associated detention and transit camps and prisons. While these camps housed criminals of all types, the Gulag system has become primarily known as a place forpolitical prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although ...

s and as a mechanism for repressing political opposition to the Soviet state."

Repressions in annexed territories

During the early years ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the Soviet Union annexed several territories in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

as a consequence of the German–Soviet Pact and its Secret Additional Protocol.

Baltic States

In theBaltic countries

The Baltic states or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term encompassing Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, and the OECD. The three sovereign states on the eastern co ...

of Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

, Latvia

Latvia, officially the Republic of Latvia, is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the three Baltic states, along with Estonia to the north and Lithuania to the south. It borders Russia to the east and Belarus to t ...

and Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

, repressions and mass deportations were carried out by the Soviets. The Serov Instructions, ''"On the Procedure for carrying out the Deportation of Anti-Soviet Elements from Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia"'', contained detailed procedures and protocols to observe in the deportation of Baltic nationals. Public tribunals were also set up to punish "traitors to the people": those who had fallen short of the "political duty" of voting their countries into the USSR. In the first year of Soviet occupation, from June 1940 to June 1941, the number confirmed executed, conscripted, or deported is estimated at a minimum of 124,467: 59,732 in Estonia, 34,250 in Latvia, and 30,485 in Lithuania. This included 8 former heads of state and 38 ministers from Estonia, 3 former heads of state and 15 ministers from Latvia, and the then-president, 5 prime ministers and 24 other ministers from Lithuania.

Poland

Romania

Post-Stalin era (1953–1991)

AfterStalin's death

Joseph Stalin, second leader of the Soviet Union, died on 5 March 1953 at his Kuntsevo Dacha after suffering a stroke, at age 74. He was given a state funeral in Moscow on 9 March, with four days of national mourning declared. On the day of t ...

, the suppression of dissent was dramatically reduced and it also took new forms. The internal critics of the system were convicted of anti-Soviet agitation

Anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda (ASA) () was a criminal offence in the Soviet Union. Initially, the term was interchangeably used with counter-revolutionary agitation. The latter term was in use immediately after the October Revolution of 1917 ...

, anti-Soviet slander, or they were accused of being "social parasites". Other critics were accused of being mentally ill, they were accused of having sluggish schizophrenia and incarcerated in "psikhushka

Psikhushka (; ) is a Russian ironic diminutive for psychiatric hospital. In Russia, the word entered everyday vocabulary. This word has been occasionally used in English, since the Soviet dissident movement and diaspora community in the West use ...

s", i.e. mental hospitals which were used as prisons by the Soviet authorities. A number of notable dissidents

A dissident is a person who actively challenges an established political or religious system, doctrine, belief, policy, or institution. In a religious context, the word has been used since the 18th century, and in the political sense since the 2 ...

, including Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Soviet and Russian author and Soviet dissidents, dissident who helped to raise global awareness of political repression in the Soviet Union, especially the Gulag pris ...

, Vladimir Bukovsky

Vladimir Konstantinovich Bukovsky (; 30 December 1942 – 27 October 2019) was a Soviet and Russian Human rights activists, human rights activist and writer. From the late 1950s to the mid-1970s, he was a prominent figure in the Soviet dissid ...

, and Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov (; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet Physics, physicist and a List of Nobel Peace Prize laureates, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, which he was awarded in 1975 for emphasizing human rights around the world.

Alt ...

, were sent to internal or external exile.

Loss of life

Estimates of the number of deaths attributable specifically to

Estimates of the number of deaths attributable specifically to Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

vary widely. Some scholars assert that record-keeping of the executions of political prisoners and ethnic minorities are neither reliable nor complete; others contend archival materials contain irrefutable data far superior to sources utilized prior to 1991, such as statements from emigres and other informants. Those historians working after the Soviet Union's dissolution have estimated victim totals ranging from approximately 3 million to nearly 9 million. Some scholars still assert that the death toll could be in the tens of millions.

American historian Richard Pipes

Richard Edgar Pipes (; July 11, 1923 – May 17, 2018) was an American historian who specialized in Russian and Soviet history. Pipes was a frequent interviewee in the press on the matters of Soviet history and foreign affairs. His writings als ...

noted: "Censuses revealed that between 1932 and 1939—that is, after collectivization but before World War II—the population decreased by 9 to 10 million people. In his most recent edition of ''The Great Terror

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the assassination of Sergei Kirov by Leonid Nikolae ...

'' (2007), Robert Conquest

George Robert Acworth Conquest (15 July 19173 August 2015) was a British and American historian, poet, novelist, and propagandist. He was briefly a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain but later wrote several books condemning commun ...

states that while exact numbers may never be known with complete certainty, at least 15 million people were killed "by the whole range of Soviet regime's terrors". Rudolph Rummel

Rudolph Joseph Rummel (October 21, 1932 – March 2, 2014) was an American political scientist, a statistician and professor at Indiana University, Yale University, and University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. He spent his career studying data on collect ...

in 2006 said that the earlier higher victim total estimates are correct, although he includes those killed by the government of the Soviet Union in other Eastern European countries as well. Conversely, J. Arch Getty and Stephen G. Wheatcroft insist that the opening of the Soviet archives has vindicated the lower estimates put forth by "revisionist" scholars. Simon Sebag Montefiore

Simon Jonathan Sebag Montefiore ( ; born 27 June 1965) is a British historian, television presenter and author of history books and novels,

including '' Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar'' (2003), '' Jerusalem: The Biography'' (2011), '' The Rom ...

in 2003 suggested that Stalin was ultimately responsible for the deaths of at least 20 million people.

Some of these estimates rely in part on demographic losses. Conquest explained how he arrived at his estimate: "I suggest about eleven million by the beginning of 1937, and about three million over the period 1937–38, making fourteen million. The eleven-odd million is readily deduced from the undisputed population deficit shown in the suppressed census of January 1937, of fifteen to sixteen million, by making reasonable assumptions about how this was divided between birth deficit and deaths."

Australian historian Stephen G. Wheatcroft claims that prior to the opening of the archives for historical research, "our understanding of the scale and the nature of Soviet repression has been extremely poor" and that some specialists who wish to maintain earlier high estimates of the Stalinist death toll are "finding it difficult to adapt to the new circumstances when the archives are open and when there are plenty of irrefutable data" and instead "hang on to their old Sovietological methods with round-about calculations based on odd statements from emigres and other informants who are supposed to have superior knowledge." Conversely, some historians believe that the official archival figures of the categories that were recorded by Soviet authorities are unreliable and incomplete. In addition to failures regarding comprehensive recordings, as one additional example, Canadian historian Robert Gellately

Robert Gellately (born 1943) is a Canadian academic and noted authority on the history of modern Europe, particularly during World War II and the Cold War era.

Education and career

He earned his B.A., B.Ed., and M.A. degrees at Memorial Unive ...

and British historian Simon Sebag Montefiore

Simon Jonathan Sebag Montefiore ( ; born 27 June 1965) is a British historian, television presenter and author of history books and novels,

including '' Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar'' (2003), '' Jerusalem: The Biography'' (2011), '' The Rom ...

argue that the many suspects beaten and tortured to death while in "investigative custody" were likely not to have been counted amongst the executed.

Remembering the victims

A Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Political Repression (День памяти жертв политических репрессий) has been officially held on 30 October in Russia since 1991. It is also marked in other former Soviet republics except Ukraine, which has its own annual Day of Remembrance for the victims of political repressions by the Soviet regime, held each year on the third Sunday of May.

Members of the Memorial society took an active part in such commemorative meetings. Since 2007, Memorial had also organised the day-long "Restoring the Names" ceremony at the Solovetsky Stone in Moscow every 29 October. The organization was banned by the

A Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Political Repression (День памяти жертв политических репрессий) has been officially held on 30 October in Russia since 1991. It is also marked in other former Soviet republics except Ukraine, which has its own annual Day of Remembrance for the victims of political repressions by the Soviet regime, held each year on the third Sunday of May.

Members of the Memorial society took an active part in such commemorative meetings. Since 2007, Memorial had also organised the day-long "Restoring the Names" ceremony at the Solovetsky Stone in Moscow every 29 October. The organization was banned by the Russian government

The Russian Government () or fully titled the Government of the Russian Federation () is the highest federal executive governmental body of the Russian Federation. It is accountable to the president of the Russian Federation and controlled by ...

in 2022. Some of Memorial's human rights activities have continued in Russia.

The Wall of Grief in Moscow, inaugurated in October 2017, is Russia's first monument ordered by presidential decree for people killed during the Stalinist

Stalinism (, ) is the totalitarian means of governing and Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1927 to 1953 by dictator Joseph Stalin and in Soviet satellite states between 1944 and 1953. Stalinism in ...

repressions in the Soviet Union.

See also

*Active measures

Active measures () is a term used to describe political warfare conducted by the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation. The term, which dates back to the 1920s, includes operations such as espionage, propaganda, sabotage and assassination, b ...

* Crimes against humanity under communist regimes

* Criticism of communist party rule

* Goli Otok

* Hitler Youth conspiracy

*Human rights in the Soviet Union

Human rights in the Soviet Union were severely limited. The Soviet Union was a Totalitarianism, totalitarian state from History of the Soviet Union (1927–53), 1927 until 1953 and a one-party state until 1990. Freedom of speech was suppressed an ...

* Mass killings under communist regimes

* Persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union

* Persecution of Christians in the Eastern Bloc

*Political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union

There was systematic political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union, based on the interpretation of political opposition or dissent as a psychiatric problem. It was called "psychopathological mechanisms" of dissent.

During the leader ...

*Rehabilitation (Soviet)

Rehabilitation (, transliterated in English as ''reabilitatsiya'' or academically rendered as ''reabilitacija'') was a term used in the context of the former Soviet Union and the post-Soviet states. Beginning after the death of Stalin in 1953, ...

*Law of the Soviet Union

The Law of the Soviet Union was the law as it developed in the Soviet Union (USSR) following the October Revolution of 1917. Modified versions of the Soviet legal system operated in many Communist states following the Second World War—including ...

*Politics of the Soviet Union

The political system of the Soviet Union took place in a federal single-party soviet socialist republic framework which was characterized by the superior role of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), the only party permitted by the C ...

*Soviet repressions in Belarus

Soviet repression in Belarus () refers to cases of persecution of people in Belarus under Soviet rule.

Number of victims

According to researchers, the exact number of people who became victims of Soviet repression in Belarus is hard to determin ...

*'' The Black Book of Communism''

* Anti-religious campaign during the Russian Civil War (1917–1921)

* RSFSR and USSR anti-religious campaign (1921–1928)

* USSR anti-religious campaign (1928–1941)

* USSR anti-religious campaign (1958–1964)

* USSR anti-religious campaign (1970s–1987)

References

Notes

Bibliography

* * * * * * *"New directions in Gulag studies: a roundtable discussion,"

Canadian Slavonic Papers 59, no 3-4 (2017) * * * * * Lynne Viola

"New sources on Soviet perpetrators of mass repression: a research note,"

Canadian Slavonic Papers 60, no 3-4 (2018) * * * * *

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{Soviet Union topics Political and cultural purges Persecution of dissidents in the Soviet Union Murder in the Soviet Union Political violence Persecution of intellectuals