South Sea Islands on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a

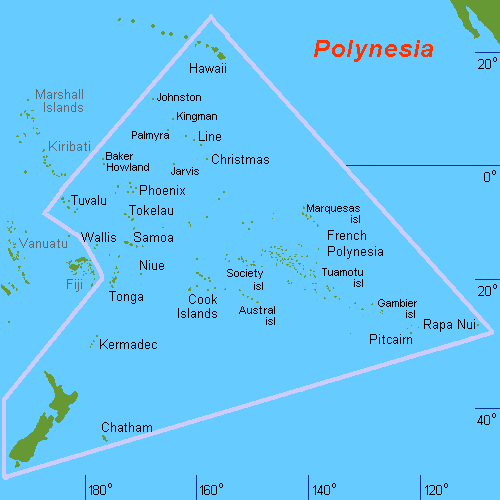

Polynesia is characterized by a small amount of land spread over a very large portion of the mid- and southern

Polynesia is characterized by a small amount of land spread over a very large portion of the mid- and southern

The Polynesian people are considered, by linguistic, archaeological, and human genetic evidence, a subset of the sea-migrating

The Polynesian people are considered, by linguistic, archaeological, and human genetic evidence, a subset of the sea-migrating  The results of research at the Teouma Lapita site (

The results of research at the Teouma Lapita site ( A complete

A complete

In the 10th century, the

In the 10th century, the

The

The

Polynesia divides into two distinct cultural groups, East Polynesia and West Polynesia. The culture of West Polynesia is conditioned to high populations. It has strong institutions of marriage and well-developed judicial, monetary and trading traditions. West Polynesia comprises the groups of

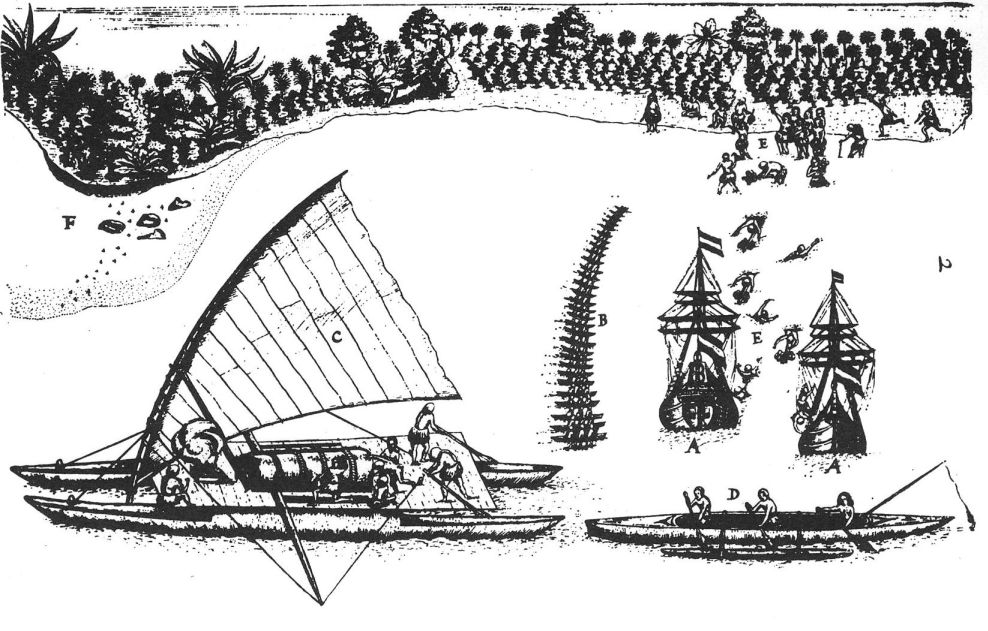

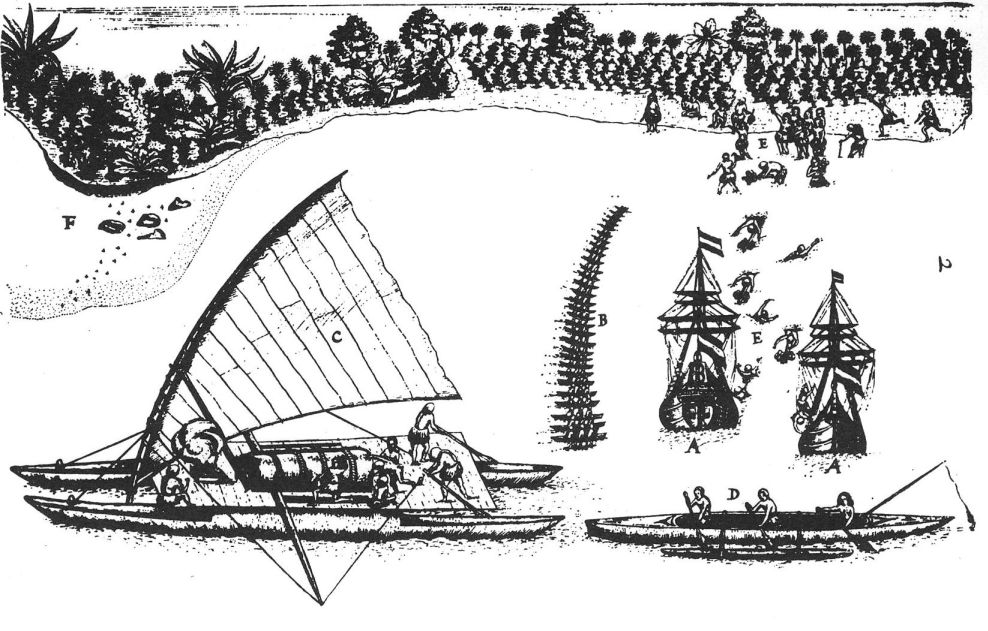

Polynesia divides into two distinct cultural groups, East Polynesia and West Polynesia. The culture of West Polynesia is conditioned to high populations. It has strong institutions of marriage and well-developed judicial, monetary and trading traditions. West Polynesia comprises the groups of  Religion, farming, fishing, weather prediction, out-rigger canoe (similar to modern

Religion, farming, fishing, weather prediction, out-rigger canoe (similar to modern

Interstellar Migration and the Human Experience

'".

Aside from New Zealand, another focus area of economic dependence regarding tourism is Hawaii. Hawaii is one of the most visited areas within the Polynesian Triangle, entertaining more than ten million visitors annually, excluding 2020. The economy of Hawaii, like that of New Zealand, is steadily dependent on annual tourists and financial counseling or aid from other countries or states. "The rate of tourist growth has made the economy overly dependent on this one sector, leaving Hawaii extremely vulnerable to external economic forces." By keeping this in mind, island states and nations similar to Hawaii are paying closer attention to other avenues that can positively affect their economy by practicing more independence and less emphasis on tourist entertainment.

Aside from New Zealand, another focus area of economic dependence regarding tourism is Hawaii. Hawaii is one of the most visited areas within the Polynesian Triangle, entertaining more than ten million visitors annually, excluding 2020. The economy of Hawaii, like that of New Zealand, is steadily dependent on annual tourists and financial counseling or aid from other countries or states. "The rate of tourist growth has made the economy overly dependent on this one sector, leaving Hawaii extremely vulnerable to external economic forces." By keeping this in mind, island states and nations similar to Hawaii are paying closer attention to other avenues that can positively affect their economy by practicing more independence and less emphasis on tourist entertainment.

These

These

Interview with David Lewis

Useful introduction to Maori society, including canoe voyages

{{Authority control 1750s neologisms Asia-Pacific Islands of Oceania Regions of Oceania

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a subregion

A subregion is a part of a larger region or continent and is usually based on location. Cardinal directions, such as south are commonly used to define a subregion.

United Nations subregions

The United Nations Statistics Division, Statistics ...

of Oceania

Oceania (, , ) is a region, geographical region that includes Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Spanning the Eastern Hemisphere, Eastern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres, Oceania is estimated to have a land area of ...

, made up of more than 1,000 island

An island (or isle) is an isolated piece of habitat that is surrounded by a dramatically different habitat, such as water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, skerries, cays or keys. An island ...

s scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are called Polynesians

Polynesians form an ethnolinguistic group of closely related people who are native to Polynesia (islands in the Polynesian Triangle), an expansive region of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. They trace their early prehistoric origins to Island Sou ...

. They have many things in common, including language relatedness, cultural practices, and traditional beliefs

A tradition is a belief or behavior (folk custom) passed down within a group or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common examples include holidays o ...

. In centuries past, they had a strong shared tradition of sailing and using stars to navigate at night. The largest country in Polynesia is New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

.

The term was first used in 1756 by the French writer Charles de Brosses

Charles de Brosses (), comte de Tournay, baron de Montfalcon, seigneur de Vezins et de Prevessin (7 February 1709 – 7 May 1777), was a French writer of the 18th century.

Life

He was president of the parliament of his hometown Dijon from 1741, a ...

, who originally applied it to all the islands of the Pacific. In 1831, Jules Dumont d'Urville

Jules Sébastien César Dumont d'Urville (; 23 May 1790 – 8 May 1842) was a French explorer and naval officer who explored the south and western Pacific, Australia, New Zealand, and Antarctica. As a botanist and cartographer, he gave his nam ...

proposed a narrower definition during a lecture at the Geographical Society of Paris. By tradition, the islands located in the southern Pacific

The Southern Pacific (or Espee from the railroad initials- SP) was an American Class I railroad network that existed from 1865 to 1996 and operated largely in the Western United States. The system was operated by various companies under the ...

have also often been called the South Sea Islands, and their inhabitants have been called South Sea Islanders

South Sea Islanders are the Australian descendants of Pacific Islanders from more than 80 islandsincluding the Oceanian archipelagoes of the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Fiji, the Gilbert Islands and New Ireland (island), New Ire ...

. The Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, Nā Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Kur ...

have often been considered to be part of the South Sea Islands because of their relative proximity to the southern Pacific islands, even though they are in fact located in the North Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

. Another term in use, which avoids this inconsistency, is "the Polynesian Triangle

The Polynesian Triangle is a region of the Pacific Ocean with three island groups at its corners: Hawai‘i, Easter Island (''Rapa Nui'') and New Zealand (Aotearoa). It is often used as a simple way to define Polynesia.

Outside the triangle, th ...

" (from the shape created by the layout of the islands in the Pacific Ocean). This term makes clear that the grouping includes the Hawaiian Islands, which are located at the northern vertex

Vertex, vertices or vertexes may refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics and computer science

*Vertex (geometry), a point where two or more curves, lines, or edges meet

* Vertex (computer graphics), a data structure that describes the positio ...

of the referenced "triangle".

Geography

Geology

Polynesia is characterized by a small amount of land spread over a very large portion of the mid- and southern

Polynesia is characterized by a small amount of land spread over a very large portion of the mid- and southern Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

. It comprises approximately of land, of which more than are within New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

. The Hawaiian archipelago comprises about half the remainder.

Most Polynesian islands and archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

s, including the Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, Nā Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Kur ...

and Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands (Manono Island, Manono an ...

, are composed of volcanic islands built by hotspots

Hotspot, Hot Spot or Hot spot may refer to:

Places

* Hot Spot, Kentucky, a community in the United States

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional entities

* Hot Spot (comics), a name for the DC Comics character Isaiah Crockett

* Hot Spot (Tra ...

(volcanoes). The other land masses in Polynesia — New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island (, ; Norfuk: ''Norf'k Ailen'') is an external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head and about from Lord Howe Island. Together with ...

, and Ouvéa

Ouvéa () or Uvea is a commune in the Loyalty Islands Province of New Caledonia, an overseas territory of France in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from t ...

, the Polynesian outlier near New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

— are the unsubmerged portions of the largely sunken continent of Zealandia

Zealandia (pronounced ), also known as (Māori) or Tasmantis, is an almost entirely submerged mass of continental crust that subsided after breaking away from Gondwanaland 83–79 million years ago.Gurnis, M., Hall, C.E., and Lavier, L.L., ...

.

Zealandia is believed to have mostly sunk below sea level 23 million years ago, and recently partially resurfaced due to a change in the movements of the Pacific Plate

The Pacific Plate is an oceanic tectonic plate that lies beneath the Pacific Ocean. At , it is the largest tectonic plate.

The plate first came into existence 190 million years ago, at the triple junction between the Farallon, Phoenix, and Iza ...

in relation to the Indo-Australian Plate

The Indo-Australian Plate is a major tectonic plate that includes the continent of Australia and the surrounding ocean and extends northwest to include the Indian subcontinent and the adjacent waters. It was formed by the fusion of the Indian an ...

. The Pacific plate had previously been subducted under the Australian Plate

The Australian Plate is a major tectonic plate in the eastern and, largely, southern hemispheres. Originally a part of the ancient continent of Gondwana, Australia remained connected to India and Antarctica until approximately when India broke ...

. When that changed, it had the effect of uplifting the portion of the continent that is modern-day New Zealand.

The convergent plate boundary that runs northwards from New Zealand's North Island is called the Kermadec-Tonga subduction zone

The Kermadec-Tonga subduction zone is a convergent plate boundary that stretches from the North Island of New Zealand northward. The formation of the Kermadec and Tonga Plates started about 4–5 million years ago. Today, the eastern boundary ...

. This subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

zone is associated with the volcanism that gave rise to the Kermadec Kermadec or de Kermadec may refer to:

Geography

* Kermadec Islands, a subtropical island arc in the South Pacific Ocean northeast of New Zealand

* Kermadec Plate, a long narrow tectonic plate located west of the Kermadec Trench

* Kermadec Trench, ...

and Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

n islands.

There is a transform fault

A transform fault or transform boundary, is a fault along a plate boundary where the motion is predominantly horizontal. It ends abruptly where it connects to another plate boundary, either another transform, a spreading ridge, or a subductio ...

that currently traverses New Zealand's South Island, known as the Alpine Fault

The Alpine Fault is a geological fault that runs almost the entire length of New Zealand's South Island (c. 480 km) and forms the boundary between the Pacific Plate and the Indo-Australian Plate. The Southern Alps have been uplifted on the f ...

.

Zealandia's continental shelf has a total area of approximately .

The oldest rocks in Polynesia are found in New Zealand and are believed to be about 510 million years old. The oldest Polynesian rocks outside Zealandia are to be found in the Hawaiian Emperor Seamount Chain and are 80 million years old.

Geographical area

Polynesia is generally defined as the islands within thePolynesian Triangle

The Polynesian Triangle is a region of the Pacific Ocean with three island groups at its corners: Hawai‘i, Easter Island (''Rapa Nui'') and New Zealand (Aotearoa). It is often used as a simple way to define Polynesia.

Outside the triangle, th ...

, although some islands inhabited by Polynesians

Polynesians form an ethnolinguistic group of closely related people who are native to Polynesia (islands in the Polynesian Triangle), an expansive region of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. They trace their early prehistoric origins to Island Sou ...

are situated outside the Polynesian Triangle. Geographically, the Polynesian Triangle is drawn by connecting the points of Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, and Easter Island

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearl ...

. The other main island groups located within the Polynesian Triangle are Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands (Manono Island, Manono an ...

, Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

, the Cook Islands

)

, image_map = Cook Islands on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, capital = Avarua

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Avarua

, official_languages =

, lan ...

, Tuvalu

Tuvalu ( or ; formerly known as the Ellice Islands) is an island country and microstate in the Polynesian subregion of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. Its islands are situated about midway between Hawaii and Australia. They lie east-northeast ...

, Tokelau

Tokelau (; ; known previously as the Union Islands, and, until 1976, known officially as the Tokelau Islands) is a dependent territory of New Zealand in the southern Pacific Ocean. It consists of three tropical coral atolls: Atafu, Nukunonu, a ...

, Niue

Niue (, ; niu, Niuē) is an island country in the South Pacific Ocean, northeast of New Zealand. Niue's land area is about and its population, predominantly Polynesian, was about 1,600 in 2016. Niue is located in a triangle between Tong ...

, Wallis and Futuna

Wallis and Futuna, officially the Territory of the Wallis and Futuna Islands (; french: Wallis-et-Futuna or ', Fakauvea and Fakafutuna: '), is a French island collectivity in the South Pacific, situated between Tuvalu to the northwest, Fiji ...

, and French Polynesia

)Territorial motto: ( en, "Great Tahiti of the Golden Haze")

, anthem =

, song_type = Regional anthem

, song = " Ia Ora 'O Tahiti Nui"

, image_map = French Polynesia on the globe (French Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of Frenc ...

.

Also, small Polynesian settlements are in Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

, the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capita ...

, the Caroline Islands

The Caroline Islands (or the Carolines) are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically, they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) in the centra ...

, and Vanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (french: link=no, République de Vanuatu; bi, Ripablik blong Vanuatu), is an island country located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of no ...

. An island group with strong Polynesian cultural traits outside of this great triangle is Rotuma

Rotuma is a Fijian dependency, consisting of Rotuma Island and nearby islets. The island group is home to a large and unique Polynesian indigenous ethnic group which constitutes a recognisable minority within the population of Fiji, known as " ...

, situated north of Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists ...

. The people of Rotuma have many common Polynesian traits, but speak a non-Polynesian language

The Polynesian languages form a genealogical group of languages, itself part of the Oceanic branch of the Austronesian family.

There are 38 Polynesian languages, representing 7 percent of the 522 Oceanic languages, and 3 percent of the Austro ...

. Some of the Lau Islands

The Lau Islands aka little Tonga (also called the Lau Group, the Eastern Group, the Eastern Archipelago) of Fiji are situated in the southern Pacific Ocean, just east of the Koro Sea. Of this chain of about sixty islands and islets, about thirty ...

to the southeast of Fiji have strong historic and cultural links with Tonga. However, in essence, Polynesia remains a cultural term referring to one of the three parts of Oceania

Oceania (, , ) is a region, geographical region that includes Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Spanning the Eastern Hemisphere, Eastern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres, Oceania is estimated to have a land area of ...

(the others being Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from Indonesia's New Guinea in the west to Fiji in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, Va ...

and Micronesia

Micronesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, consisting of about 2,000 small islands in the western Pacific Ocean. It has a close shared cultural history with three other island regions: the Philippines to the west, Polynesia to the east, and ...

).

Island groups

The following are the islands and island groups, either nations or overseas territories of former colonial powers, that are of native Polynesian culture or where archaeological evidence indicates Polynesian settlement in the past. Some islands of Polynesian origin are outside the general triangle that geographically defines the region.Core area

TheLine Islands

The Line Islands, Teraina Islands or Equatorial Islands (in Gilbertese, ''Aono Raina'') are a chain of 11 atolls (with partly or fully enclosed lagoons) and coral islands (with a surrounding reef) in the central Pacific Ocean, south of the Hawa ...

and the Phoenix Islands

The Phoenix Islands, or Rawaki, are a group of eight atolls and two submerged coral reefs that lie east of the Gilbert Islands and west of the Line Islands in the central Pacific Ocean, north of Samoa. They are part of the Kiribati, Republic ...

, most of which are parts of Kiribati

Kiribati (), officially the Republic of Kiribati ( gil, ibaberikiKiribati),Kiribati

''The Wor ...

, had no permanent settlements until European colonization, but are often considered to be parts of the ''The Wor ...

Polynesian Triangle

The Polynesian Triangle is a region of the Pacific Ocean with three island groups at its corners: Hawai‘i, Easter Island (''Rapa Nui'') and New Zealand (Aotearoa). It is often used as a simple way to define Polynesia.

Outside the triangle, th ...

.

Polynesians once inhabited the Auckland Islands

The Auckland Islands (Māori: ''Motu Maha'' "Many islands" or ''Maungahuka'' "Snowy mountains") are an archipelago of New Zealand, lying south of the South Island. The main Auckland Island, occupying , is surrounded by smaller Adams Island, ...

, the Kermadec Islands

The Kermadec Islands ( mi, Rangitāhua) are a subtropical island arc in the South Pacific Ocean northeast of New Zealand's North Island, and a similar distance southwest of Tonga. The islands are part of New Zealand. They are in total ar ...

, and Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island (, ; Norfuk: ''Norf'k Ailen'') is an external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head and about from Lord Howe Island. Together with ...

in pre-colonial times, but these islands were uninhabited by the time European explorers arrived.

The oceanic islands beyond Easter Island, such as Clipperton Island

Clipperton Island ( or ; ) is an uninhabited, coral atoll in the eastern Pacific Ocean. It is from Paris, France, from Papeete, Tahiti, and from Mexico. It is an Overseas France, overseas state private property of France under direct authori ...

, the Galápagos Islands

The Galápagos Islands (Spanish: , , ) are an archipelago of volcanic islands. They are distributed on each side of the equator in the Pacific Ocean, surrounding the centre of the Western Hemisphere, and are part of the Republic of Ecuador ...

, and the Juan Fernández Islands

The Juan Fernández Islands ( es, Archipiélago Juan Fernández) are a sparsely inhabited series of islands in the South Pacific Ocean reliant on tourism and fishing. Situated off the coast of Chile, they are composed of three main volcanic i ...

, have, on rare occasion, been categorized as being geographically within Polynesia. Some of these islands are still uninhabited, and they are believed to have had no prehistoric contact with either Polynesians or the indigenous peoples of the Americas

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many Indigenous peoples of the A ...

.

Outliers

=Melanesia

= * Anuta (inSolomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capita ...

)

* Bellona Island

Bellona Island is an island of the Rennell and Bellona Province, in the Solomon Islands. Its length is about and its average width . Its area is about . It is almost totally surrounded by high cliffs, consisting primarily of raised coral lim ...

(in Solomon Islands)

* Emae

Emae is an island in the Shepherd Islands, Shefa, Vanuatu.

Geography

Maunga Lasi is the highest peak at 644 m. It forms the northern rim of the (mostly) underwater volcano of Makura, which also covers the nearby islands of Makura and Mataso. I ...

(in Vanuatu)

* Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists ...

(excluding Rotuma

Rotuma is a Fijian dependency, consisting of Rotuma Island and nearby islets. The island group is home to a large and unique Polynesian indigenous ethnic group which constitutes a recognisable minority within the population of Fiji, known as " ...

and the Lau Islands

The Lau Islands aka little Tonga (also called the Lau Group, the Eastern Group, the Eastern Archipelago) of Fiji are situated in the southern Pacific Ocean, just east of the Koro Sea. Of this chain of about sixty islands and islets, about thirty ...

)

* Mele

Mele () is a ''Comune'' (Municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Genoa in the Italian region Liguria, located about west of Genoa.

Mele borders the following municipalities: Genoa, Masone

Masone ( or ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the ...

(in Vanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (french: link=no, République de Vanuatu; bi, Ripablik blong Vanuatu), is an island country located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of no ...

)

* Nuguria

Nuguria or the Nuguria Islands, also known as the Abgarris or Fead Islands,Richard Parkinson et al. ''Thirty years in the South Seas'', 1999 are a Polynesian outlier and islands of Papua New Guinea. They are located nearly 150 km from the nor ...

(in Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

)

* Nukumanu

The Nukumanu Islands, formerly the Tasman Islands, is an atoll of Papua New Guinea, located in the south-western Pacific Ocean, 4 degrees south of the Equator.

Description

Comprising a ring of more than twenty islets on a reef surrounding a ...

(in Papua New Guinea)

* Ontong Java

Ontong Java Atoll or Luangiua, (formerly ''Lord Howe Atoll'', not to be confused with Lord Howe Island) is one of the largest atolls on earth.

Geographically it belongs to a scattered group of three atolls which includes nearby Nukumanu Atol ...

(in Solomon Islands)

* Pileni

300px, Map of the Reef Islands

Pileni is a culturally important island in the Reef Islands, in the northern part of the Solomon Islands province of Temotu. Despite its location in Melanesia, the population of the islands is Polynesian.

Pileni ...

(in Solomon Islands)

* Rennell (in Solomon Islands)

* Sikaiana

Sikaiana (formerly called the Stewart Islands) is a small atoll NE of Malaita in Solomon Islands in the south Pacific Ocean. It is almost in length and its lagoon, known as Te Moana, is totally enclosed by the coral reef. Its total land ...

(in Solomon Islands)

* Takuu

Takuu, formerly known as Tauu and also known as Takuu Mortlock or Marqueen Islands, is a small, isolated atoll off the east coast of Bougainville in Papua New Guinea.

Geography

Takuu lies about 250 km to the northeast of Kieta, capital of ...

(in Papua New Guinea)

* Tikopia

Tikopia is a high island in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It forms a part of the Melanesian nation state of Solomon Islands but is culturally Polynesian. The first Europeans arrived on 22 April 1606 as part of the Spanish expedition of Pedro F ...

(in Solomon Islands)

=Micronesia

= *Kapingamarangi

Kapingamarangi is an atoll and a municipality in the state of Pohnpei of the Federated States of Micronesia. It is by far the most southerly atoll or island of the country and of the Caroline Islands, south of the next southerly atoll, Nukuoro, ...

(in the Federated States of Micronesia

The Federated States of Micronesia (; abbreviated FSM) is an island country in Oceania. It consists of four states from west to east, Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei and Kosraethat are spread across the western Pacific. Together, the states comprise a ...

)

* Nukuoro

Nukuoro is an atoll in the Federated States of Micronesia. It is a municipality of the state of Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia. It is the secondmost southern atoll of the country, after Kapingamarangi. They both are Polynesian outliers ...

(in the Federated States of Micronesia)

* Wake Island

Wake Island ( mh, Ānen Kio, translation=island of the kio flower; also known as Wake Atoll) is a coral atoll in the western Pacific Ocean in the northeastern area of the Micronesia subregion, east of Guam, west of Honolulu, southeast of To ...

(a part of the United States Minor Outlying Islands

The United States Minor Outlying Islands is a statistical designation defined by the International Organization for Standardization's ISO 3166-1 code. The entry code is ISO 3166-2:UM. The minor outlying islands and groups of islands consist ...

)

=Sub-Antarctic islands

= *Auckland Islands

The Auckland Islands (Māori: ''Motu Maha'' "Many islands" or ''Maungahuka'' "Snowy mountains") are an archipelago of New Zealand, lying south of the South Island. The main Auckland Island, occupying , is surrounded by smaller Adams Island, ...

(the most southerly known evidence of Polynesian settlement)

History

Origins and expansion

The Polynesian people are considered, by linguistic, archaeological, and human genetic evidence, a subset of the sea-migrating

The Polynesian people are considered, by linguistic, archaeological, and human genetic evidence, a subset of the sea-migrating Austronesian people

The Austronesian peoples, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples in Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar that speak Austrones ...

. Tracing Polynesian languages

The Polynesian languages form a genealogical group of languages, itself part of the Oceanic branch of the Austronesian family.

There are 38 Polynesian languages, representing 7 percent of the 522 Oceanic languages, and 3 percent of the Austron ...

places their prehistoric

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use of ...

origins in Island Melanesia

Island Melanesia is a subregion of Melanesia in Oceania.

It is located east of New Guinea island, from the Bismarck Archipelago to New Caledonia.Steadman, 2006. ''Extinction & biogeography of tropical Pacific birds''

See also Archaeology an ...

, Maritime Southeast Asia

Maritime Southeast Asia comprises the countries of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and East Timor. Maritime Southeast Asia is sometimes also referred to as Island Southeast Asia, Insular Southeast Asia or Oceanic Sout ...

, and ultimately, in Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

.

Between about 3,000 and 1,000 BCE, speakers of Austronesian languages began spreading from Taiwan into Maritime Southeast Asia

Maritime Southeast Asia comprises the countries of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and East Timor. Maritime Southeast Asia is sometimes also referred to as Island Southeast Asia, Insular Southeast Asia or Oceanic Sout ...

.

There are three theories regarding the spread of humans across the Pacific to Polynesia. These are outlined well by Kayser ''et al.'' (2000) and are as follows:

* Express Train model: A recent (c. 3,000–1,000 BCE) expansion out of Taiwan, via the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

and eastern Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

and from the northwest ("Bird's Head

The Bird's Head Peninsula ( Indonesian: ''Kepala Burung'', nl, Vogelkop) or Doberai Peninsula (''Semenanjung Doberai''), is a large peninsula that makes up the northwest portion of the island of New Guinea, comprising the Indonesian provinces ...

") of New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

, on to Island Melanesia

Island Melanesia is a subregion of Melanesia in Oceania.

It is located east of New Guinea island, from the Bismarck Archipelago to New Caledonia.Steadman, 2006. ''Extinction & biogeography of tropical Pacific birds''

See also Archaeology an ...

by roughly 1400 BCE, reaching western Polynesian islands around 900 BCE followed by a roughly 1,000 year "pause" before continued settlement in central and eastern Polynesia. This theory is supported by the majority of current genetic, linguistic

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

, and archaeological data.

* Entangled Bank model: Emphasizes the long history of Austronesian speakers' cultural and genetic interactions with indigenous Island Southeast Asians and Melanesians along the way to becoming the first Polynesians.

* Slow Boat model: Similar to the express-train model but with a longer hiatus in Melanesia along with admixture — genetically, culturally and linguistically — with the local population. This is supported by the Y-chromosome data of Kayser ''et al.'' (2000), which shows that all three haplotype

A haplotype ( haploid genotype) is a group of alleles in an organism that are inherited together from a single parent.

Many organisms contain genetic material ( DNA) which is inherited from two parents. Normally these organisms have their DNA or ...

s of Polynesian Y chromosomes can be traced back to Melanesia.

In the archaeological record, there are well-defined traces of this expansion which allow the path it took to be followed and dated with some certainty. It is thought that by roughly 1,400 BCE, " Lapita Peoples", so-named after their pottery tradition, appeared in the Bismarck Archipelago

The Bismarck Archipelago (, ) is a group of islands off the northeastern coast of New Guinea in the western Pacific Ocean and is part of the Islands Region of Papua New Guinea. Its area is about 50,000 square km.

History

The first inhabitants o ...

of northwest Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from Indonesia's New Guinea in the west to Fiji in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, Va ...

. This culture is seen as having adapted and evolved through time and space since its emergence "Out of Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

". They had given up rice production, for instance, which required paddy field

A paddy field is a flooded field (agriculture), field of arable land used for growing Aquatic plant, semiaquatic crops, most notably rice and taro. It originates from the Neolithic rice-farming cultures of the Yangtze River basin in sout ...

agriculture unsuitable for small islands. However, they still cultivated other ancestral Austronesian staple cultigen

A cultigen () or cultivated plant is a plant that has been deliberately altered or selected by humans; it is the result of artificial selection. These plants, for the most part, have commercial value in horticulture, agriculture or forestry. Beca ...

s like '' Dioscorea'' yams and taro

Taro () (''Colocasia esculenta)'' is a root vegetable. It is the most widely cultivated species of several plants in the family Araceae that are used as vegetables for their corms, leaves, and petioles. Taro corms are a food staple in Africa ...

(the latter are still grown with smaller-scale paddy field technology), as well as adopting new ones like breadfruit

Breadfruit (''Artocarpus altilis'') is a species of flowering tree in the mulberry and jackfruit family (Moraceae) believed to be a domesticated descendant of ''Artocarpus camansi'' originating in New Guinea, the Maluku Islands, and the Philippi ...

and sweet potato

The sweet potato or sweetpotato (''Ipomoea batatas'') is a dicotyledonous plant that belongs to the Convolvulus, bindweed or morning glory family (biology), family, Convolvulaceae. Its large, starchy, sweet-tasting tuberous roots are used as a r ...

.

Efate Island

Efate (french: Éfaté) is an island in the Pacific Ocean which is part of the Shefa Province in Vanuatu. It is also known as Île Vate.

Geography

It is the most populous (approx. 66,000) island in Vanuatu. Efate's land area of makes it Vanua ...

, Vanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (french: link=no, République de Vanuatu; bi, Ripablik blong Vanuatu), is an island country located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of no ...

) and the Talasiu Lapita site (near Nuku'alofa, Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

) published in 2016 supports the Express Train model; although with the qualification that the migration bypassed New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

and Island Melanesia

Island Melanesia is a subregion of Melanesia in Oceania.

It is located east of New Guinea island, from the Bismarck Archipelago to New Caledonia.Steadman, 2006. ''Extinction & biogeography of tropical Pacific birds''

See also Archaeology an ...

. The conclusion from research published in 2016 is that the initial population of those two sites appears to come directly from Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

or the northern Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

and did not mix with the ‘ Australo-Papuans’ of New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

and the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capita ...

. The preliminary analysis of skulls found at the Teouma and Talasiu Lapita sites is that they lack Australian or Papuan affinities and instead have affinities to mainland Asian populations.

A 2017 DNA analysis of modern Polynesians indicates that there has been intermarriage resulting in a mixed Austronesian-Papuan ancestry of the Polynesians (as with other modern Austronesians, with the exception of Taiwanese aborigines

Taiwanese may refer to:

* Taiwanese language, another name for Taiwanese Hokkien

* Something from or related to Taiwan ( Formosa)

* Taiwanese aborigines, the indigenous people of Taiwan

* Han Taiwanese, the Han people of Taiwan

* Taiwanese people, ...

). Research at the Teouma and Talasiu Lapita sites implies that the migration and intermarriage, which resulted in the mixed Austronesian-Papuan ancestry of the Polynesians, occurred after the first initial migration to Vanuatu and Tonga.

A complete

A complete mtDNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA ...

and genome-wide SNP comparison (Pugach ''et al.'', 2021) of the remains of early settlers of the Mariana Islands

The Mariana Islands (; also the Marianas; in Chamorro: ''Manislan Mariånas'') are a crescent-shaped archipelago comprising the summits of fifteen longitudinally oriented, mostly dormant volcanic mountains in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, betw ...

and early Lapita individuals from Vanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (french: link=no, République de Vanuatu; bi, Ripablik blong Vanuatu), is an island country located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of no ...

and Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

also suggest that both migrations originated directly from the same ancient Austronesian source population from the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

. The complete absence of "Papuan" admixture in the early samples indicates that these early voyages bypassed eastern Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

and the rest of New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

. The authors have also suggested a possibility that the early Lapita Austronesians were direct descendants of the early colonists of the Marianas (which preceded them by about 150 years), which is also supported by pottery evidence.

The most eastern site for Lapita archaeological remains recovered so far is at Mulifanua

Mulifanua is a village on the north-western tip of the island of Upolu, in Samoa. In the modern era, it is the capital of Aiga-i-le-Tai district. Mulifanua wharf is the main ferry terminal for inter-island vehicle and passenger travel across t ...

on Upolu

Upolu is an island in Samoa, formed by a massive basaltic shield volcano which rises from the seafloor of the western Pacific Ocean. The island is long and in area, making it the second largest of the Samoan Islands by area. With approximatel ...

. The Mulifanua site, where 4,288 pottery shards have been found and studied, has a "true" age of based on radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

and is the oldest site yet discovered in Polynesia. This is mirrored by a 2010 study also placing the beginning of the human archaeological sequences of Polynesia in Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

at 900 BCE.

Within a mere three or four centuries, between 1,300 and 900 BCE, the Lapita archaeological culture

An archaeological culture is a recurring assemblage of types of artifacts, buildings and monuments from a specific period and region that may constitute the material culture remains of a particular past human society. The connection between thes ...

spread 6,000 km further to the east from the Bismarck Archipelago, until reaching as far as Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists ...

, Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

, and Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands (Manono Island, Manono an ...

. A cultural divide began to develop between Fiji to the west, and the distinctive Polynesian language and culture emerging on Tonga and Samoa to the east. Where there was once faint evidence of uniquely shared developments in Fijian and Polynesian speech, most of this is now called "borrowing" and is thought to have occurred in those and later years more than as a result of continuing unity of their earliest dialects on those far-flung lands. Contacts were mediated especially through the Tovata

Tovata is one of three ''confederacies'' comprising the Fijian House of Chiefs, to which all of Fiji's chiefs belong.

Details of Tovata

It is located in the north east of the country, covering the provinces of Bua, Macuata and Cakaudrove on ...

confederacy of Fiji. This is where most Fijian-Polynesian linguistic interactions occurred.

In the chronology of the exploration and first populating of Polynesia, there is a gap commonly referred to as the long pause between the first populating of Western Polynesia including Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa among others and the settlement of the rest of the region. In general this gap is considered to have lasted roughly 1,000 years. The cause of this gap in voyaging is contentious among archaeologists with a number of competing theories presented including climate shifts, the need for the development of new voyaging techniques, and cultural shifts.

After the long pause, dispersion of populations into central and eastern Polynesia began. Although the exact timing of when each island group was settled is debated, it is widely accepted that the island groups in the geographic center of the region (i.e. the Cook Islands

)

, image_map = Cook Islands on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, capital = Avarua

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Avarua

, official_languages =

, lan ...

, Society Islands

The Society Islands (french: Îles de la Société, officially ''Archipel de la Société;'' ty, Tōtaiete mā) are an archipelago located in the South Pacific Ocean. Politically, they are part of French Polynesia, an overseas country of the F ...

, Marquesas Islands

The Marquesas Islands (; french: Îles Marquises or ' or '; Marquesan: ' ( North Marquesan) and ' ( South Marquesan), both meaning "the land of men") are a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France in th ...

, etc.) were settled initially between 1,000 and 1,150 CE, and ending with more far flung island groups such as Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, and Easter Island

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearl ...

settled between 1,200 and 1,300 CE.

Tiny populations may have been involved in the initial settlement of individual islands; although Professor Matisoo-Smith of the Otago study said that the founding Māori population of New Zealand must have been in the hundreds, much larger than previously thought. The Polynesian population experienced a founder effect and genetic drift. The Polynesian may be distinctively different both genotypically and phenotypically

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological proper ...

from the parent population from which it is derived. This is due to new population being established by a very small number of individuals from a larger population which also causes a loss of genetic variation.

Atholl Anderson

Atholl John Anderson (born 1943) is a New Zealand archaeologist who has worked extensively in New Zealand and the Pacific. His work is notable for its syntheses of history, biology, ethnography and archaeological evidence. He made a major contr ...

wrote that analysis of mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

(mtDNA, female) and Y chromosome

The Y chromosome is one of two sex chromosomes (allosomes) in therian mammals, including humans, and many other animals. The other is the X chromosome. Y is normally the sex-determining chromosome in many species, since it is the presence or abse ...

(male) concluded that the ancestors of Polynesian women were Austronesians

The Austronesian peoples, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples in Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar that speak Austrone ...

while those of Polynesian men were Papuans

The indigenous peoples of West Papua in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, commonly called Papuans, are Melanesians. There is genetic evidence for two major historical lineages in New Guinea and neighboring islands: a first wave from the Malay Arch ...

. Subsequently, it was found that 96% (or 93.8%) of Polynesian mtDNA has an Asian origin, as does one-third of Polynesian Y chromosomes; the remaining two-thirds from New Guinea and nearby islands; this is consistent with matrilocal residence patterns. Polynesians existed from the intermixing of few ancient Austronesian-Melanesian founders, genetically they belong almost entirely to the Haplogroup B (mtDNA), which is the marker of Austronesian expansions. The high frequencies of mtDNA Haplogroup B in the Polynesians are the result of founder effect and represents the descendants of a few Austronesian females who intermixed with Papuan males.

A genomic analysis of modern populations in Polynesia, published in 2021, provides a model of the direction and timing of Polynesian migrations from Samoa to the islands to the east. This model presents consistencies and inconsistencies with models of Polynesian migration that are based on archaeology and linguistic analysis. The 2021 genomic model presents a migration pathway from Samoa to the Cook Islands

)

, image_map = Cook Islands on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, capital = Avarua

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Avarua

, official_languages =

, lan ...

(Rarotonga), then to the Society Islands

The Society Islands (french: Îles de la Société, officially ''Archipel de la Société;'' ty, Tōtaiete mā) are an archipelago located in the South Pacific Ocean. Politically, they are part of French Polynesia, an overseas country of the F ...

(Tōtaiete mā) in the 11th century, the western Austral Islands

The Austral Islands (french: Îles Australes, officially ''Archipel des Australes;'' ty, Tuha'a Pae) are the southernmost group of islands in French Polynesia, an overseas country of the French Republic in the South Pacific. Geographically, ...

(Tuha’a Pae) and the Tuāmotu Archipelago in the 12th century, with the migrant pathway branching to the north to the Marquesas

The Marquesas Islands (; french: Îles Marquises or ' or '; Marquesan: ' (North Marquesan) and ' (South Marquesan), both meaning "the land of men") are a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France in t ...

(Te Henua ‘Enana), to Raivavae

Raivavae ( Tahitian: ''Ra‘ivāvae'' /ra.ʔi.va:va.e/) is one of the Austral Islands in French Polynesia. Its total land area including offshore islets is . At the 2017 census, it had a population of 903.

in the south, and to the easternmost destination on Easter Island

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearl ...

(Rapa Nui), which was settled in approximately CE 1200 via Mangareva

Mangareva is the central and largest island of the Gambier Islands in French Polynesia. It is surrounded by smaller islands: Taravai in the southwest, Aukena and Akamaru in the southeast, and islands in the north. Mangareva has a permanent pop ...

.

Culture

The Polynesians werematrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's Lineage (anthropology), lineage – and which can in ...

and matrilocal

In social anthropology, matrilocal residence or matrilocality (also uxorilocal residence or uxorilocality) is the societal system in which a married couple resides with or near the wife's parents. Thus, the female offspring of a mother remain ...

Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistoric period during which stone was widely used to make tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years, and ended between 4,000 BC and 2,000 BC, with t ...

societies upon arrival in Fiji, Tonga and Samoa, after having been through at least some time in the Bismarck Archipelago. The modern Polynesians still show human genetic results of a Melanesian culture which allowed indigenous men, but not women, to "marry in" – useful evidence for matrilocality.

Although matrilocality and matrilineality receded at some early time, Polynesians and most other Austronesian speakers in the Pacific Islands, were/are still highly "matricentric" in their traditional jurisprudence. The Lapita pottery for which the general archaeological complex of the earliest "Oceanic" Austronesian speakers in the Pacific Islands are named also went away in Western Polynesia. Language, social life and material culture

Material culture is the aspect of social reality grounded in the objects and architecture that surround people. It includes the usage, consumption, creation, and trade of objects as well as the behaviors, norms, and rituals that the objects creat ...

were very distinctly "Polynesian" by 1000 BCE.

Linguistically, there are five sub-groups of the Polynesian language group. Each represents a region within Polynesia and the categorization of these language groups by Green in 1966 helped to confirm Polynesian settlement took place west to east. There is a very distinct "East Polynesian" subgroup with many shared innovations not seen in other Polynesian languages. The Marquesas dialects are perhaps the source of the oldest Hawaiian speech which is overlaid by Tahitian variety speech, as Hawaiian oral histories would suggest. The earliest varieties of New Zealand Maori speech may have had multiple sources from around central Eastern Polynesia as Maori oral histories would suggest.

Political history

Cook Islands

The Cook Islands is made up of 15 islands comprising the Northern and Southern groups. The islands are spread out across many kilometers of a vast ocean. The largest of these islands is called Rarotonga, which is also the political and economic capital of the nation. The Cook Islands were formerly known as the Hervey Islands, but this name refers only to the Northern Groups. It is unknown when this name was changed to reflect the current name. It is thought that the Cook Islands were settled in two periods: the Tahitian Period, when the country was settled between 900 and 1300 AD, and the Maui Settlement, which occurred in 1600 AD, when a large contingent from Tahiti settled in Rarotonga, in the Takitumu district. The first contact between Europeans and the native inhabitants of the Cook Islands took place in 1595 with the arrival of Spanish explorer Álvaro de Mendaña inPukapuka

Pukapuka, formerly Danger Island, is a coral atoll in the northern group of the Cook Islands in the Pacific Ocean. It is one of most remote islands of the Cook Islands, situated about northwest of Rarotonga. On this small island, an ancient ...

, who called it ''San Bernardo'' (Saint Bernard). A decade later, navigator Pedro Fernández de Quirós

Pedro is a masculine given name. Pedro is the Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician name for '' Peter''. Its French equivalent is Pierre while its English and Germanic form is Peter.

The counterpart patronymic surname of the name Pedro, meaning ...

made the first European landing in the islands when he set foot on Rakahanga

Rakahanga is part of the Cook Islands, situated in the central-southern Pacific Ocean. The unspoilt atoll is from the Cook Islands' capital, Rarotonga, and lies south of the equator. Its nearest neighbour is Manihiki which is just away. Rakah ...

in 1606, calling it ''Gente Hermosa'' (Beautiful People).

Cook Islanders are ethnically Polynesians or Eastern Polynesia. They are culturally associated with Tahiti, Eastern Islands, NZ Maori and Hawaii. Early in the 17th century, they became the first race to settle in New Zealand.

Fiji

TheLau Islands

The Lau Islands aka little Tonga (also called the Lau Group, the Eastern Group, the Eastern Archipelago) of Fiji are situated in the southern Pacific Ocean, just east of the Koro Sea. Of this chain of about sixty islands and islets, about thirty ...

were subject to periods of Tongan rulership and then Fijian control until their eventual conquest by Seru Epenisa Cakobau of the Kingdom of Fiji by 1871. In around 1855 a Tongan prince, Enele Ma'afu Enele is a given name. Notable people with the name include:

* Enele Maʻafu ( 1816–1881), Tongan chief

* Enele Malele (born 1990), Fijian rugby union player

* Enele Sopoaga (born 1956), Tuvaluan diplomat and politician

* Enele Taufa (bor ...

, proclaimed the Lau islands as his kingdom, and took the title Tui Lau

Tui Lau is a Fijian chiefly title of recent history which was created during the time of Ma'afu and his conquests.

A Brief History

Ma'afu was disclaimed as a Tongan Prince by his cousin King George Tupou I. Since the Vuanirewa Clan of the Lau ...

.

Fiji had been ruled by numerous divided chieftains until Cakobau unified the landmass. The Lapita culture, the ancestors of the Polynesians, existed in Fiji from about 3500 BCE until they were displaced by the Melanesians about a thousand years later. (Both Samoans and subsequent Polynesian cultures adopted Melanesian painting and tattoo methods.)

In 1873, Cakobau ceded a Fiji heavily indebted to foreign creditors to the United Kingdom. It became independent on 10 October 1970 and a republic on 28 September 1987.

Fiji is classified as Melanesian and (less commonly) Polynesian.

Hawaii

New Zealand

Beginning in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, Polynesians began to migrate in waves toNew Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

via their canoes

A canoe is a lightweight narrow water vessel, typically pointed at both ends and open on top, propelled by one or more seated or kneeling paddlers facing the direction of travel and using a single-bladed paddle.

In British English, the term ...

, settling on both the North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

islands as well as the Chatham Islands

The Chatham Islands ( ) (Moriori: ''Rēkohu'', 'Misty Sun'; mi, Wharekauri) are an archipelago in the Pacific Ocean about east of New Zealand's South Island. They are administered as part of New Zealand. The archipelago consists of about te ...

. Over the course of several centuries, the Polynesian settlers formed distinct cultures that became known as the Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the C ...

on the New Zealand mainland , while those who settled in the Chatham Islands

The Chatham Islands ( ) (Moriori: ''Rēkohu'', 'Misty Sun'; mi, Wharekauri) are an archipelago in the Pacific Ocean about east of New Zealand's South Island. They are administered as part of New Zealand. The archipelago consists of about te ...

became the Moriori people

The Moriori are the native Polynesian people of the Chatham Islands (''Rēkohu'' in Moriori; ' in Māori), New Zealand. Moriori originated from Māori settlers from the New Zealand mainland around 1500 CE. This was near the time of th ...

. Beginning the 17th century, the arrival of Europeans to New Zealand drastically impacted Māori culture. Settlers from Europe (known as "Pākehā

Pākehā (or Pakeha; ; ) is a Māori term for New Zealanders primarily of European descent. Pākehā is not a legal concept and has no definition under New Zealand law. The term can apply to fair-skinned persons, or to any non-Māori New Ze ...

") began to colonize New Zealand in the 19th century, leading to tension with the indigenous Māori. On October 28, 1835, a group of Māori tribesmen issued a declaration of independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the ...

(drafted by Scottish businessman James Busby

James Busby (7 February 1802 – 15 July 1871) was the British Resident in New Zealand from 1833 to 1840. He was involved in drafting the 1835 Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand and the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi. As British Resident, ...

) as the "United Tribes of New Zealand

The United Tribes of New Zealand ( mi, Te W(h)akaminenga o Ngā Rangatiratanga o Ngā Hapū o Nū Tīreni, lit=) was a confederation of Māori tribes based in the north of the North Island, existing legally from 1835 to 1840. It received dipl ...

", in order to resist potential efforts at colonizing New Zealand by the French and prevent merchant ship

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are u ...

s and their cargo which belonged to Māori merchants from being seized at foreign ports. The new state received recognition from the British Crown

The Crown is the state (polity), state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, British Overseas Territories, overseas territories, Provinces and territorie ...

in 1836.

In 1840, Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

officer William Hobson

Captain William Hobson (26 September 1792 – 10 September 1842) was a British Royal Navy officer who served as the first Governor of New Zealand. He was a co-author of the Treaty of Waitangi.

Hobson was dispatched from London in July 1 ...

and several Māori chiefs signed the Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi ( mi, Te Tiriti o Waitangi) is a document of central importance to the history, to the political constitution of the state, and to the national mythos of New Zealand. It has played a major role in the treatment of the M ...

, which transformed New Zealand into a colony

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the ''metropole, metropolit ...

of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

and granting all Māori the status of British subjects. However, tensions between Pākehā settlers and the Māori over settler encroachment on Māori lands and disputes over land sales led to the New Zealand Wars

The New Zealand Wars took place from 1845 to 1872 between the New Zealand colonial government and allied Māori on one side and Māori and Māori-allied settlers on the other. They were previously commonly referred to as the Land Wars or the ...

(1845-1872) between the colonial government and the Māori. In response to the conflict, the colonial government initiated a series of land confiscations from the Māori. This social upheavel, combined with epidemics of infectious diseases from Europe, devastated both the Māori population and their social standing in New Zealand. In the 20th and 21st centuries, the Maori population began to recover, and efforts were made to redress social, economic, political and economic issues facing the Māori in wider New Zealand society. Beginning in the 1960s, a protest movement

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration or remonstrance) is a public expression of objection, disapproval or dissent towards an idea or action, typically a political one.

Protests can be thought of as acts of cooper ...

emerged seeking redress for historical grievances. In the 2013 New Zealand census

The 2013 New Zealand census was the thirty-third national census. "The National Census Day" used for the census was on Tuesday, 5 March 2013. The population of New Zealand was counted as 4,242,048, – an increase of 214,101 or 5.3% over the 20 ...

, roughly 600,000 people in New Zealand identified as being Māori.

Samoa

In the 9th century, theTui Manu'a

The title Tui Manuʻa was the title of the ruler or paramount chief of the Manuʻa Islands in present-day American Samoa.

The Tuʻi Manuʻa Confederacy, or Samoan Empire, are descriptions sometimes given to Samoan expansionism and projecte ...

controlled a vast maritime empire comprising most of the settled islands of Polynesia. The Tui Manu'a is one of the oldest Samoan titles in Samoa. Traditional oral literature

Oral literature, orature or folk literature is a genre of literature that is spoken or sung as opposed to that which is written, though much oral literature has been transcribed. There is no standard definition, as anthropologists have used vary ...

of Samoa and Manu'a talks of a widespread Polynesian network or confederacy (or "empire") that was prehistorically ruled by the successive Tui Manu'a dynasties. Manuan genealogies and religious oral literature also suggest that the Tui Manu'a had long been one of the most prestigious and powerful paramount of Samoa. Oral history suggests that the Tui Manu'a kings governed a confederacy of far-flung islands which included Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists ...

, Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

as well as smaller western Pacific chiefdom

A chiefdom is a form of hierarchical political organization in non-industrial societies usually based on kinship, and in which formal leadership is monopolized by the legitimate senior members of select families or 'houses'. These elites form a ...

s and Polynesian outlier

Polynesian outliers are a number of culturally Polynesian societies that geographically lie outside the main region of Polynesian influence, known as the Polynesian Triangle; instead, Polynesian outliers are scattered in the two other Pacific s ...

s such as Uvea

The uvea (; Lat. ''uva'', "grape"), also called the ''uveal layer'', ''uveal coat'', ''uveal tract'', ''vascular tunic'' or ''vascular layer'' is the pigmented middle of the three concentric layers that make up an eye.

History and etymolog ...

, Futuna, Tokelau

Tokelau (; ; known previously as the Union Islands, and, until 1976, known officially as the Tokelau Islands) is a dependent territory of New Zealand in the southern Pacific Ocean. It consists of three tropical coral atolls: Atafu, Nukunonu, a ...

, and Tuvalu

Tuvalu ( or ; formerly known as the Ellice Islands) is an island country and microstate in the Polynesian subregion of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. Its islands are situated about midway between Hawaii and Australia. They lie east-northeast ...

. Commerce and exchange routes between the western Polynesian societies are well documented and it is speculated that the Tui Manu'a dynasty grew through its success in obtaining control over the oceanic trade of currency goods such as finely woven ceremonial mats, whale ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals is ...

"tabua

A tabua is a polished tooth of a sperm whale that is an important cultural item in Fijian society. They were traditionally given as gifts for atonement or esteem (called ''sevusevu''), and were important in negotiations between rival chiefs. The ...

", obsidian

Obsidian () is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extrusive rock, extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock.

Obsidian is produced from felsic lava, rich in the lighter elements s ...

and basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

tools, chiefly red feathers, and seashells reserved for royalty (such as polished nautilus

The nautilus (, ) is a pelagic marine mollusc of the cephalopod family Nautilidae. The nautilus is the sole extant family of the superfamily Nautilaceae and of its smaller but near equal suborder, Nautilina.

It comprises six living species in ...

and the egg cowry