South Atlantic Blockading Squadron on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Union blockade in the

While a large proportion of blockade runners did manage to evade the Union ships, as the blockade matured, the type of ship most likely to find success in evading the naval cordon was a small, light ship with a short draft—qualities that facilitated blockade running but were poorly suited to carrying large amounts of heavy weaponry, metals, and other supplies badly needed by the South. They were also useless for exporting the large quantities of cotton that the South needed to sustain its economy. To be successful in helping the Confederacy, a blockade runner had to make many trips; eventually, most were captured or sunk. Nonetheless, five out of six attempts to evade the Union blockade were successful. During the war, some 1,500 blockade runners were captured or destroyed.

Ordinary freighters were too slow and visible to escape the Navy. The blockade runners therefore relied mainly on new steamships built in Britain with low profiles, shallow draft, and high speed. Their paddle-wheels, driven by steam engines that burned smokeless

While a large proportion of blockade runners did manage to evade the Union ships, as the blockade matured, the type of ship most likely to find success in evading the naval cordon was a small, light ship with a short draft—qualities that facilitated blockade running but were poorly suited to carrying large amounts of heavy weaponry, metals, and other supplies badly needed by the South. They were also useless for exporting the large quantities of cotton that the South needed to sustain its economy. To be successful in helping the Confederacy, a blockade runner had to make many trips; eventually, most were captured or sunk. Nonetheless, five out of six attempts to evade the Union blockade were successful. During the war, some 1,500 blockade runners were captured or destroyed.

Ordinary freighters were too slow and visible to escape the Navy. The blockade runners therefore relied mainly on new steamships built in Britain with low profiles, shallow draft, and high speed. Their paddle-wheels, driven by steam engines that burned smokeless  The blockade runners were based in the British islands of

The blockade runners were based in the British islands of

The Confederacy constructed

The Confederacy constructed

In December 1864, Union

In December 1864, Union

*

*

* *

*

Url

* * * Greene, Jack (1998). ''Ironclads at War''; Combined Publishing * McPherson, James M., ''War on the Waters: The Union & Confederate Navies, 1861-1865'' University of North Carolina Press, 2012, * * Surdam, David G. (2001). ''Northern Naval Superiority and the Economics of the American Civil War'';

Simon & Schuster, New York. *

Url

*

Url1Url2

* Wynne, Nick & Cranshaw, Joe (2011). ''Florida Civil War Blockades''

History Press, Charleston, SC, .

Url

*

Url

''Unintended Consequences of Confederate Trade Legislation''

''The Hapless Anaconda: Union Blockade 1861–1865''

By W. T. Block

* David G. Surdam

Northern Naval Superiority and the Economics of the American Civil War

Egotistigraphy", by John Sanford Barnes. An autobiography, including his Civil War Union Navy service on a ship participating in the blockade, USS ''Wabash'', privately printed 1910. Internet edition edited by Susan Bainbridge Hay 2012

{{DEFAULTSORT:Union Blockade Military operations of the American Civil War Blockades involving the United States Maritime history of the United States 1861 in the American Civil War 1862 in the American Civil War 1863 in the American Civil War 1864 in the American Civil War 1865 in the American Civil War Campaigns of the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War Campaigns of the Lower Seaboard Theater and Gulf Approach of the American Civil War .

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

was a naval strategy by the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

to prevent the Confederacy from trading.

The blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are le ...

was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

in April 1861, and required the monitoring of of Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

and Gulf

A gulf is a large inlet from the ocean into the landmass, typically with a narrower opening than a bay, but that is not observable in all geographic areas so named. The term gulf was traditionally used for large highly-indented navigable bodie ...

coastline, including 12 major ports, notably New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

and Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Mobile

Mobile may refer to:

Places

* Mobile, Alabama, a U.S. port city

* Mobile County, Alabama

* Mobile, Arizona, a small town near Phoenix, U.S.

* Mobile, Newfoundland and Labrador

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Mobile ( ...

. Those blockade runners fast enough to evade the Union Navy

), (official)

, colors = Blue and gold

, colors_label = Colors

, march =

, mascot =

, equipment =

, equipment_label ...

could carry only a small fraction of the supplies needed. They were operated largely by foreign citizens, making use of neutral ports such as Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

, Nassau

Nassau may refer to:

Places Bahamas

*Nassau, Bahamas, capital city of the Bahamas, on the island of New Providence

Canada

*Nassau District, renamed Home District, regional division in Upper Canada from 1788 to 1792

*Nassau Street (Winnipeg), ...

and Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

. The Union commissioned around 500 ships, which destroyed or captured about 1,500 blockade runners over the course of the war.

Proclamation of blockade and legal implications

On April 19, 1861, President Lincoln issued a ''Proclamation of Blockade Against Southern Ports'':Whereas an insurrection against the Government of the United States has broken out in the States of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas, and the laws of the United States for the collection of the revenue cannot be effectually executed therein comformably to that provision of the Constitution which requires duties to be uniform throughout the United States: And whereas a combination of persons engaged in such insurrection, have threatened to grant pretended letters of marque to authorize the bearers thereof to commit assaults on the lives, vessels, and property of good citizens of the country lawfully engaged in commerce on the high seas, and in waters of the United States: And whereas an Executive Proclamation has been already issued, requiring the persons engaged in these disorderly proceedings to desist therefrom, calling out a militia force for the purpose of repressing the same, and convening Congress in extraordinary session, to deliberate and determine thereon: Now, therefore, I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, with a view to the same purposes before mentioned, and to the protection of the public peace, and the lives and property of quiet and orderly citizens pursuing their lawful occupations, until Congress shall have assembled and deliberated on the said unlawful proceedings, or until the same shall ceased, have further deemed it advisable to set on foot a blockade of the ports within the States aforesaid, in pursuance of the laws of the United States, and of the law of Nations, in such case provided. For this purpose a competent force will be posted so as to prevent entrance and exit of vessels from the ports aforesaid. If, therefore, with a view to violate such blockade, a vessel shall approach, or shall attempt to leave either of the said ports, she will be duly warned by the Commander of one of the blockading vessels, who will endorse on her register the fact and date of such warning, and if the same vessel shall again attempt to enter or leave the blockaded port, she will be captured and sent to the nearest convenient port, for such proceedings against her and her cargo as prize, as may be deemed advisable. And I hereby proclaim and declare that if any person, under the pretended authority of the said States, or under any other pretense, shall molest a vessel of the United States, or the persons or cargo on board of her, such person will be held amenable to the laws of the United States for the prevention and punishment of piracy. In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand, and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed. Done at the City of Washington, this nineteenth day of April, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-one, and of the Independence of the United States the eighty-fifth.

Operations

Scope

A joint Union military-navy commission, known as theBlockade Strategy Board The Blockade Strategy Board, also known as the Commission of Conference, or the Du Pont Board, was a strategy group created by the United States Navy Department at outset of the American Civil War to lay out a preliminary strategy for enforcing P ...

, was formed to make plans for seizing major Southern ports to utilize as Union bases of operations to expand the blockade. It first met in June 1861 in Washington, D.C., under the leadership of Captain Samuel F. Du Pont

Samuel Francis Du Pont (September 27, 1803 – June 23, 1865) was a rear admiral in the United States Navy, and a member of the prominent Du Pont family. In the Mexican–American War, Du Pont captured San Diego, and was made commander of the Ca ...

.

In the initial phase of the blockade, Union forces concentrated on the Atlantic Coast. The November 1861 capture of Port Royal in South Carolina provided the Federals with an open ocean port and repair and maintenance facilities in good operating condition. It became an early base of operations for further expansion of the blockade along the Atlantic coastline, including the Stone Fleet

The Stone Fleet consisted of a fleet of aging ships (mostly whaleships) purchased in New Bedford and other New England ports, loaded with stone, and sailed south during the American Civil War by the Union Navy for use as blockships. They were to ...

of old ships deliberately sunk to block approaches to Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

. Apalachicola, Florida

Apalachicola ( ) is a city and the county seat of Franklin County, Florida, United States, on the shore of Apalachicola Bay, an inlet of the Gulf of Mexico. The population was 2,231 at the 2010 census.

History

The Apalachicola people, after ...

, received Confederate goods

In economics, goods are items that satisfy human wants

and provide utility, for example, to a consumer making a purchase of a satisfying product. A common distinction is made between goods which are transferable, and services, which are not tran ...

traveling down the Chattahoochee River

The Chattahoochee River forms the southern half of the Alabama and Georgia border, as well as a portion of the Florida - Georgia border. It is a tributary of the Apalachicola River, a relatively short river formed by the confluence of the Chatta ...

from Columbus, Georgia

Columbus is a consolidated city-county located on the west-central border of the U.S. state of Georgia. Columbus lies on the Chattahoochee River directly across from Phenix City, Alabama. It is the county seat of Muscogee County, with which it ...

, and was an early target of Union blockade efforts on Florida's Gulf Coast. Another early prize was Ship Island

Ship Island is a barrier island off the Gulf Coast of Mississippi, one of the Mississippi–Alabama barrier islands. Hurricane Camille split the island into two separate islands (West Ship Island and East Ship Island) in 1969. In early 2019, t ...

, which gave the Navy a base from which to patrol the entrances to both the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

and Mobile Bay

Mobile Bay ( ) is a shallow inlet of the Gulf of Mexico, lying within the state of Alabama in the United States. Its mouth is formed by the Fort Morgan Peninsula on the eastern side and Dauphin Island, a barrier island on the western side. The ...

. The Navy gradually extended its reach throughout the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

to the Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

coastline, including Galveston

Galveston ( ) is a coastal resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a population of 47,743 in 2010, is the county seat of surrounding Galvesto ...

and Sabine Pass

Sabine Pass is the natural outlet of Sabine Lake into the Gulf of Mexico. It borders Jefferson County, Texas, and Cameron Parish, Louisiana.

History Civil War

Two major battles occurred here during the American Civil War, known as the First and ...

.

With 3,500 miles (5,600 km) of Confederate coastline and 180 possible ports of entry to patrol, the blockade would be the largest such effort ever attempted. The United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

had 42 ships in active service, and another 48 laid up and listed as available as soon as crews could be assembled and trained. Half were sailing ships, some were technologically outdated, most were at the time patrolling distant oceans, one served on Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also has t ...

and could not be moved into the ocean, and another had gone missing off Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

. At the time of the declaration of the blockade, the Union only had three ships suitable for blockade duty. The Navy Department, under the leadership of Navy Secretary Gideon Welles

Gideon Welles (July 1, 1802 – February 11, 1878), nicknamed "Father Neptune", was the United States Secretary of the Navy from 1861 to 1869, a cabinet post he was awarded after supporting Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election. Although opposed ...

, quickly moved to expand the fleet. U.S. warships patrolling abroad were recalled, a massive shipbuilding program was launched, civilian merchant and passenger ships were purchased for naval service, and captured blockade runners were commissioned into the navy. In 1861, nearly 80 steamers and 60 sailing ships were added to the fleet, and the number of blockading vessels rose to 160. Some 52 more warships were under construction by the end of the year. By November 1862, there were 282 steamers and 102 sailing ships. By the end of the war, the Union Navy had grown to a size of 671 ships, making it the largest navy in the world.

By the end of 1861, the Navy had grown to 24,000 officers and enlisted men, over 15,000 more than in antebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern United States

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum ...

service. Four squadrons of ships were deployed, two in the Atlantic and two in the Gulf of Mexico.

Blockade service

Blockade service was attractive to Federal seamen and landsmen alike. Blockade station service was considered the most boring job in the war but also the most attractive in terms of potential financial gain. The task was for the fleet to sail back and forth to intercept any blockade runners. More than 50,000 men volunteered for the boring duty, because food and living conditions on ship were much better than theinfantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

offered, the work was safer, and especially because of the real (albeit small) chance for big money. Captured ships and their cargoes were sold at auction and the proceeds split among the sailors. When ''Eolus'' seized the hapless blockade runner ''Hope'' off Wilmington, North Carolina

Wilmington is a port city in and the county seat of New Hanover County in coastal southeastern North Carolina, United States.

With a population of 115,451 at the 2020 census, it is the eighth most populous city in the state. Wilmington is the ...

, in late 1864, the captain won $13,000 ($ today), the chief engineer $6,700, the seamen more than $1,000 each, and the cabin boy $533, compared to infantry pay of $13 ($ today) per month. The amount garnered for a prize of war

A prize of war is a piece of enemy property or land seized by a belligerent party during or after a war or battle, typically at sea. This term was used nearly exclusively in terms of captured ships during the 18th and 19th centuries. Basis in inte ...

widely varied. While the little ''Alligator'' sold for only $50, bagging the ''Memphis'' brought in $510,000 ($ today) (about what 40 civilian workers could earn in a lifetime of work). In four years, $25 million in prize money

Prize money refers in particular to naval prize money, usually arising in naval warfare, but also in other circumstances. It was a monetary reward paid in accordance with the prize law of a belligerent state to the crew of a ship belonging to t ...

($ today) was awarded.

Blockade runners

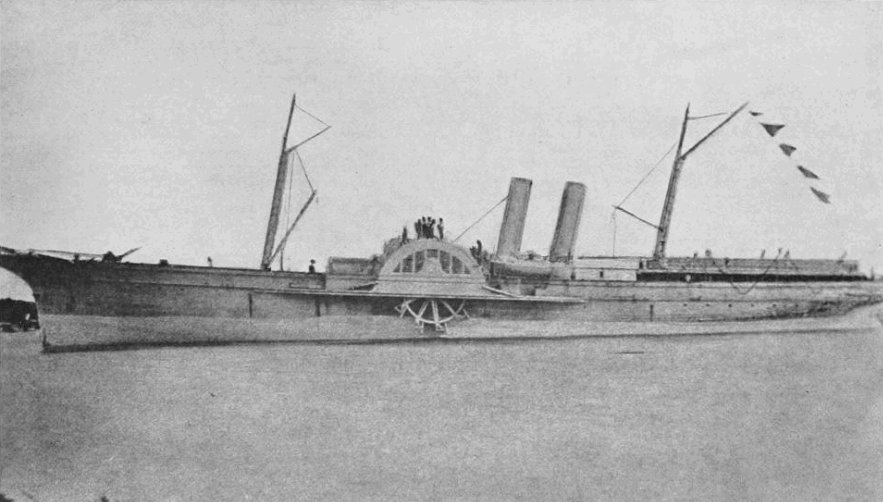

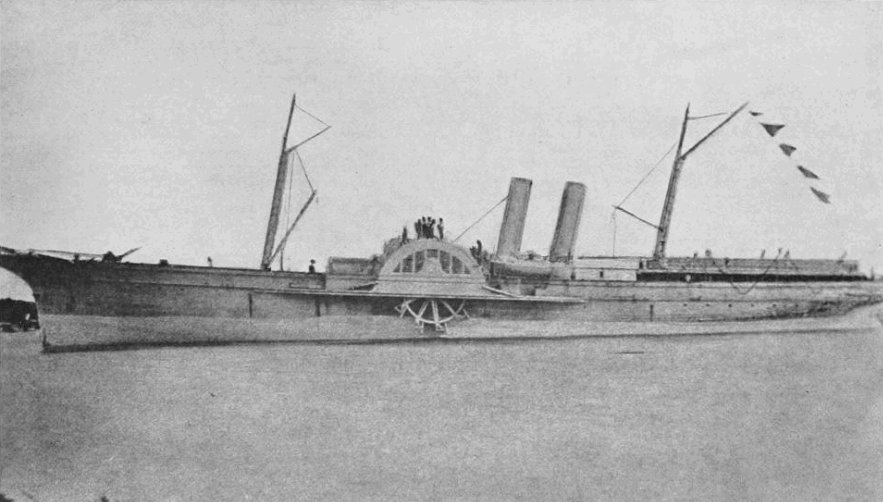

While a large proportion of blockade runners did manage to evade the Union ships, as the blockade matured, the type of ship most likely to find success in evading the naval cordon was a small, light ship with a short draft—qualities that facilitated blockade running but were poorly suited to carrying large amounts of heavy weaponry, metals, and other supplies badly needed by the South. They were also useless for exporting the large quantities of cotton that the South needed to sustain its economy. To be successful in helping the Confederacy, a blockade runner had to make many trips; eventually, most were captured or sunk. Nonetheless, five out of six attempts to evade the Union blockade were successful. During the war, some 1,500 blockade runners were captured or destroyed.

Ordinary freighters were too slow and visible to escape the Navy. The blockade runners therefore relied mainly on new steamships built in Britain with low profiles, shallow draft, and high speed. Their paddle-wheels, driven by steam engines that burned smokeless

While a large proportion of blockade runners did manage to evade the Union ships, as the blockade matured, the type of ship most likely to find success in evading the naval cordon was a small, light ship with a short draft—qualities that facilitated blockade running but were poorly suited to carrying large amounts of heavy weaponry, metals, and other supplies badly needed by the South. They were also useless for exporting the large quantities of cotton that the South needed to sustain its economy. To be successful in helping the Confederacy, a blockade runner had to make many trips; eventually, most were captured or sunk. Nonetheless, five out of six attempts to evade the Union blockade were successful. During the war, some 1,500 blockade runners were captured or destroyed.

Ordinary freighters were too slow and visible to escape the Navy. The blockade runners therefore relied mainly on new steamships built in Britain with low profiles, shallow draft, and high speed. Their paddle-wheels, driven by steam engines that burned smokeless anthracite coal

Anthracite, also known as hard coal, and black coal, is a hard, compact variety of coal that has a submetallic luster. It has the highest carbon content, the fewest impurities, and the highest energy density of all types of coal and is the high ...

, could make . Because the South lacked sufficient sailors, skippers and shipbuilding capability, the runners were mostly built, commanded and manned of officers and sailors of the British Merchant Marine. The profits from blockade running were high as a typical blockade runner could make a profit equal to about $1 million U.S dollars in 1981 values from a single voyage. Private British investors spent perhaps £50 million on the runners ($250 million in U.S. dollars, equivalent to about $2.5 billion in 2006 dollars). The pay was high: a Royal Navy officer on leave might earn several thousand dollars (in gold) in salary and bonus per round trip, with ordinary seamen earning several hundred dollars.

The blockade runners were based in the British islands of

The blockade runners were based in the British islands of Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

and the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

, or Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

, in Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

. The goods they carried were brought to these places by ordinary cargo ships, and loaded onto the runners. The runners then ran the gauntlet between their bases and Confederate ports, some apart. On each trip, a runner carried several hundred tons of compact, high-value cargo such as cotton, turpentine or tobacco outbound, and rifles, medicine, brandy, lingerie and coffee inbound. Often they also carried mail. They charged from $300 to $1,000 per ton of cargo brought in; two round trips a month would generate perhaps $250,000 in revenue (and $80,000 in wages and expenses).

Blockade runners preferred to run past the Union Navy at night, either on moonless nights, before the moon rose, or after it set. As they approached the coastline, the ships showed no lights, and sailors were prohibited from smoking. Likewise, Union warships covered all their lights, except perhaps a faint light on the commander's ship. If a Union warship discovered a blockade runner, it fired signal rockets in the direction of its course to alert other ships. The runners adapted to such tactics by firing their own rockets in different directions to confuse Union warships.

In November 1864, a wholesaler in Wilmington asked his agent in the Bahamas to stop sending so much chloroform and instead send "essence of cognac" because that perfume would sell "quite high". Confederate supporters held rich blockade runners in contempt for profiteering on luxuries while the soldiers were in rags. On the other hand, their bravery and initiative were necessary for the rebellion’s survival, and many women in the back country flaunted imported $10 gewgaws and $50 hats to demonstrate the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

had failed to isolate them from the outer world. The government in Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

, eventually regulated the traffic, requiring half the imports to be munitions; it even purchased and operated some runners on its own account and made sure they loaded vital war goods. By 1864, Lee's soldiers were eating imported meat. Blockade running was reasonably safe for both sides. It was not illegal under international law; captured foreign sailors were released, while Confederates went to prison camps. The ships were unarmed (the weight of cannon would slow them down), so they posed no danger to the Navy warships.

One example of the lucrative (and short-lived) nature of the blockade running trade was the ship ''Banshee'', which operated out of Nassau and Bermuda. She was captured on her seventh run into Wilmington, North Carolina, and confiscated by the U.S. Navy for use as a blockading ship. However, at the time of her capture, she had turned a 700% profit for her English owners, who quickly commissioned and built ''Banshee No. 2'', which soon joined the firm's fleet of blockade runners.

In May 1865, CSS ''Lark'' became the last Confederate ship to slip out of a Southern port and successfully evade the Union blockade when she left Galveston, Texas

Galveston ( ) is a coastal resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a population of 47,743 in 2010, is the county seat of surrounding Galvesto ...

, for Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

.

Impact on the Confederacy

The Union blockade was a powerful weapon that eventually ruined the Southern economy, at the cost of very few lives. The measure of the blockade's success was not the few ships that slipped through, but the thousands that never tried it. Ordinary freighters had no reasonable hope of evading the blockade and stopped calling at Southern ports. The interdiction of coastal traffic meant that long-distance travel now depended on the rickety railroad system, which never overcame the devastating impact of the blockade. Throughout the war, the South produced enough food for civilians and soldiers, but it had growing difficulty in moving surpluses to areas of scarcity and famine. Lee's army, at the end of the supply line, nearly always was short of supplies as the war progressed into its final two years. When the blockade began in 1861, it was only partially effective. It has been estimated that only one in ten ships trying to evade the blockade were intercepted. However, the Union Navy gradually increased in size throughout the war, and was able to drastically reduce shipments into Confederate ports. By 1864, one in every three ships attempting to run the blockade were being intercepted. In the final two years of the war, the only ships with a reasonable chance of evading the blockade were blockade runners specifically designed for speed. Overall, the Union Navy wrecked or captured an estimated 1500 ships that attempted to run the blockade. During the four years of the blockade, Southern ports saw approximately 8000 trips. By contrast, over 20,000 took place during the four years preceding the war. The blockade almost totally choked off Southern cotton exports, which the Confederacy depended on for hard currency. Cotton exports fell 95%, from 10 million bales in the three years prior to the war to just 500,000 bales during the blockade period. The blockade also largely reduced imports of food, medicine, war materials, manufactured goods, and luxury items, resulting in severe shortages andinflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reductio ...

. Shortages of bread led to occasional bread riots

Food riots may occur when there is a shortage and/or unequal food distribution, distribution of food. Causes can be food price rises, harvest failures, incompetent food storage, transport problems, food speculation, hoarding, poisoning of food, o ...

in Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

and other cities, showing that patriotism was not sufficient to satisfy the daily demands of the people. Land routes remained open for cattle drovers, but after the Union seized control of the Mississippi River in summer 1863, it became impossible to ship horses, cattle and swine from Texas and Arkansas to the eastern Confederacy. The blockade was a triumph of the Union Navy and a major factor in winning the war.

A significant secondary impact of the naval blockade was a resulting scarcity of salt throughout the South. In Antebellum times, returning cotton-shipping ships were often ballasted with salt, which was bountifully produced at a prehistoric dry lake near Syracuse, New York

Syracuse ( ) is a City (New York), city in and the county seat of Onondaga County, New York, Onondaga County, New York, United States. It is the fifth-most populous city in the state of New York following New York City, Buffalo, New York, Buffa ...

, but which had never been produced in significant quantity in the Southern States. Salt was necessary for curing meat; its lack led to significant hardship in keeping the Confederate forces fed as well as severely impacting the populace. In addition to blocking salt from being imported into the Confederacy, Union forces actively destroyed attempts to build salt-producing facilities at Avery Island, Louisiana

Avery Island (historically french: Île Petite Anse) is a salt dome best known as the source of Tabasco sauce. Located in Iberia Parish, Louisiana, United States, it is approximately inland from Vermilion Bay, which in turn opens onto the Gulf ...

(destroyed in 1863 by Union forces under General Nathaniel P. Banks

Nathaniel Prentice (or Prentiss) Banks (January 30, 1816 – September 1, 1894) was an American politician from Massachusetts and a Union general during the Civil War. A millworker by background, Banks was prominent in local debating societies, ...

), outside the bay at Port St. Joe, Florida (destroyed in 1862 by the Union ship Kingfisher

Kingfishers are a family, the Alcedinidae, of small to medium-sized, brightly colored birds in the order Coraciiformes. They have a cosmopolitan distribution, with most species found in the tropical regions of Africa, Asia, and Oceania, ...

), at Darien, Georgia

Darien () is a city in and the county seat of McIntosh County, Georgia, United States. It lies on Georgia's coast at the mouth of the Altamaha River, approximately south of Savannah, and is part of the Brunswick, Georgia Metropolitan Statist ...

, at Saltville, Virginia

Saltville is a town in Smyth and Washington counties in the U.S. state of Virginia. The population was 2,077 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Kingsport– Bristol (TN)– Bristol (VA) Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is a compone ...

(captured by Union forces in December 1864), and various sites hidden in marshes and bayous.

Impact on International Trade

The southern cotton industry began to heavily influence the British economy. Cotton was a highly profitable cash crop, known in the 19th century as "white gold". On the eve of the war, 1,390,938,752 pounds weight of cotton were imported into Great Britain in 1860. Of this, the United States supplied 1,115,890,608 pounds, or about five-sixths of the whole. Not only was Great Britain aware of the impact of Southern cotton, but so was the South. They were confident that their industry held large power, so much, that they referred to their industry as "King Cotton

"King Cotton" is a slogan that summarized the strategy used before the American Civil War (of 1861–1865) by secessionists in the southern states (the future Confederate States of America) to claim the feasibility of secession and to prove ther ...

." This slogan was used to declare its supremacy in America. On the floor of the U.S. Senate, Senator James Henry Hammond

James Henry Hammond (November 15, 1807 – November 13, 1864) was an attorney, politician, and planter from South Carolina. He served as a United States representative from 1835 to 1836, the 60th Governor of South Carolina from 1842 to 1844, and ...

declaimed (March 4, 1858): "You dare not make war upon cotton! No power on earth dares make war upon it. Cotton is king." The South proclaimed that many domestic and even some international markets depended so heavily on their cotton, that no one would dare spark tensions with the South. They also viewed this slogan as their reasoning behind why they should achieve their efforts in seceding from the Union. The Southern Cotton industry was so confident in the power of cotton diplomacy, that without warning, they refused to export cotton for one day.

Imagining an overwhelming response of pleas for their cotton, the Southern cotton industry experienced quite the opposite. With the decisions of Lincoln and the lack of intervention on Great Britain's part, the South was officially blockaded. Following the U.S. announcement of its intention to establish an official blockade of Confederate ports, foreign governments began to recognize the Confederacy as a belligerent

A belligerent is an individual, group, country, or other entity that acts in a hostile manner, such as engaging in combat. The term comes from the Latin ''bellum gerere'' ("to wage war"). Unlike the use of ''belligerent'' as an adjective meaning ...

in the Civil War. Great Britain declared belligerent status on May 13, 1861, followed by Spain on June 17 and Brazil on August 1. This was the first glimpse of failure for the Confederate South.

The decision to blockade Southern port cities took a large toll on the British economy but they weighed their consequences. Great Britain had a good amount of cotton stored up in warehouses in several locations that would provide for their textile needs for some time. But eventually Great Britain began to see the effects of the blockade, "the blockade had a negative impact on the economies of other countries. Textile manufacturing areas in Britain and France that depended on Southern cotton entered periods of high unemployment..." in the so-called Lancashire Cotton Famine

The Lancashire Cotton Famine, also known as the Cotton Famine or the Cotton Panic (1861–65), was a depression in the textile industry of North West England, brought about by overproduction in a time of contracting world markets. It coincided wi ...

. Nearly 80% of the cotton used in the British textile mills came from the South, and the scarcity of cotton caused by the blockade caused the price of cotton to rapidly rise by 150% by the summer of 1861. The article written in the New York Times further proves that Great Britain was aware of the influence of cotton in their empire, "Nearly one million of operatives are employed in the manufacture of cotton in Great Britain, upon whom, at least five or six millions more depend for their daily subsistence. It is no exaggeration to say, that one-quarter of the inhabitants of England are directly dependent upon the supply of cotton for their living." Despite these consequences, Great Britain concluded that their decision was crucial in terms of reaching abolition of slavery in the United States.

The blockade led to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

replacing the South as Britain's principle source of cotton. Likewise, Egyptian cotton replaced American cotton as the principle source of cotton for the textile mills of France and the Austrian empire not only for the civil war, but for the rest of the 19th century. In 1861, only 600,000 ''cantars'' (one cantar being the equivalent of 100 pounds) of cotton were exported from Egypt; by 1863 Egypt had exported 1.3 million ''cantars'' of cotton. Nearly 93% of the tax revenue collected by the Egyptian state came from taxing cotton while every landowner in the Nile river valley had started to grow cotton. The vast majority of the land in the Nile river valley were owned by a clique of wealthy families of Turkish, Albanian and Circassian origin, known in Egypt as the Turco-Circassian elite and to foreigners as the pasha class as most of the landowners usually had the Ottoman title of pasha (the equivalent of a title of nobility). The ''fellaheen'' (peasantry) became the subject of a ruthless system of exploitation as the landowners pressed the ''fellaheen'' to grow cotton instead of food, settling a bout of inflation caused by the shortage of food as more and more land was devoted to growing cotton. The wealth created by the cotton boom caused by the Union blockade led to the redevelopment of much of Cairo and Alexandria as much of the medieval cores of both cities were razed to make way for modern buildings. The cotton boom attracted a significant number of foreign businessmen to Egypt, of which the largest number were Greeks. The wealth created by the cotton boom in Egypt was ended by the end of the blockade in 1865, which allowed the cotton from the South to ultimately reenter the world market, helping to lead to Egypt's bankruptcy in 1876.

Confederate response

The Confederacy constructed

The Confederacy constructed torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of se ...

s, tending to be small, fast steam launches equipped with spar torpedo

A spar torpedo is a weapon consisting of a bomb placed at the end of a long pole, or spar, and attached to a boat. The weapon is used by running the end of the spar into the enemy ship. Spar torpedoes were often equipped with a barbed spear at ...

es, to attack the blockading fleet. Some torpedo boats were refitted steam launches; others, such as the CSS ''David'' class, were purpose-built. The torpedo boats tried to attack under cover of night by ramming the spar torpedo into the hull of the blockading ship, then backing off and detonating the explosive. The torpedo boats were not very effective and were easily countered by simple measures such as hanging chains over the sides of ships to foul the screws of the torpedo boats, or encircling the ships with wooden booms to trap the torpedoes at a distance.

One historically notable naval action was the attack of the Confederate submarine ''H. L. Hunley'', a hand-powered submarine launched from Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

, against Union blockade ships. On the night of 17 February 1864, ''Hunley'' attacked . ''Housatonic'' sank with the loss of five crew; ''Hunley'' also sank, taking her crew of eight to the bottom.

Major engagements

The first victory for the U.S. Navy during the early phases of the blockade occurred on 24 April 1861, when the sloop ''Cumberland'' and a small flotilla of support ships began seizing Confederate ships and privateers in the vicinity ofFort Monroe

Fort Monroe, managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth of Virginia, the National Park Service as the Fort Monroe National Monument, and the City of Hampton, is a former military installation in Hampton, Virgi ...

off the Virginia coastline. Within the next two weeks, Flag Officer

A flag officer is a commissioned officer in a nation's armed forces senior enough to be entitled to fly a flag to mark the position from which the officer exercises command.

The term is used differently in different countries:

*In many countr ...

Garrett J. Pendergrast had captured 16 enemy vessels, serving early notice to the Confederate War Department that the blockade would be effective if extended.

Early battles in support of the blockade included the Blockade of the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

, from May to June 1861, and the Blockade of the Carolina Coast, August–December 1861. Both enabled the Union Navy to gradually extend its blockade southward along the Atlantic seaboard.

In early March 1862, the blockade of the James River in Virginia was gravely threatened by the first ironclad, CSS ''Virginia'' in the dramatic Battle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and ''Virginia'' (rebuilt and renamed from the USS ''Merrimack'') or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the American Civil War.

It was fought over t ...

. Only the timely entry of the new Union ironclad

An ironclad is a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by Wrought iron, iron or steel iron armor, armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships ...

forestalled the threat. Two months later, ''Virginia'' and other ships of the James River Squadron

The James River Squadron was formed shortly after the secession of Virginia during the American Civil War. The squadron was part of the Virginia Navy before being transferred to the Confederate States Navy. The squadron is most notable for its ...

were scuttled in response to the Union Army and Navy advances.

The port of Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

, was effectively sealed by the reduction and surrender of Fort Pulaski

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

on 11 April.

The largest Confederate port, New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, was ill-suited to blockade running since the channels could be sealed by the U.S. Navy. From 16–22 April, the major forts below the city, Forts Jackson and St. Philip were bombarded by Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

David Dixon Porter

David Dixon Porter (June 8, 1813 – February 13, 1891) was a United States Navy admiral and a member of one of the most distinguished families in the history of the U.S. Navy. Promoted as the second U.S. Navy officer ever to attain the rank o ...

's mortar schooners. On 22 April, Flag Officer David Farragut

David Glasgow Farragut (; also spelled Glascoe; July 5, 1801 – August 14, 1870) was a flag officer of the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He was the first rear admiral, vice admiral, and admiral in the United States Navy. Fa ...

's fleet cleared a passage through the obstructions. The fleet successfully ran past the forts on the morning of 24 April. This forced the surrender of the forts and New Orleans.

The Battle of Mobile Bay

The Battle of Mobile Bay of August 5, 1864, was a naval and land engagement of the American Civil War in which a Union fleet commanded by Rear Admiral David G. Farragut, assisted by a contingent of soldiers, attacked a smaller Confederate fle ...

on 5 August 1864 closed the last major Confederate port in the Gulf of Mexico.

In December 1864, Union

In December 1864, Union Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

Gideon Welles

Gideon Welles (July 1, 1802 – February 11, 1878), nicknamed "Father Neptune", was the United States Secretary of the Navy from 1861 to 1869, a cabinet post he was awarded after supporting Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election. Although opposed ...

sent a force against Fort Fisher

Fort Fisher was a Confederate fort during the American Civil War. It protected the vital trading routes of the port at Wilmington, North Carolina, from 1861 until its capture by the Union in 1865. The fort was located on one of Cape Fear River' ...

, which protected the Confederacy's access to the Atlantic from Wilmington, North Carolina, the last open Confederate port on the Atlantic Coast. The first attack failed, but with a change in tactics (and Union generals), the fort fell in January 1865, closing the last major Confederate port.

As the Union fleet grew in size, speed and sophistication, more ports came under Federal control. After 1862, only three ports east of the Mississippi—Wilmington, North Carolina

Wilmington is a port city in and the county seat of New Hanover County in coastal southeastern North Carolina, United States.

With a population of 115,451 at the 2020 census, it is the eighth most populous city in the state. Wilmington is the ...

; Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

; and Mobile, Alabama

Mobile ( , ) is a city and the county seat of Mobile County, Alabama, United States. The population within the city limits was 187,041 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, down from 195,111 at the 2010 United States census, 2010 cens ...

—remained open for the 75–100 blockade runners in business. Charleston was shut down by Admiral John A. Dahlgren's South Atlantic Blockading Squadron in 1863. Mobile Bay was captured in August 1864 by Admiral David Farragut

David Glasgow Farragut (; also spelled Glascoe; July 5, 1801 – August 14, 1870) was a flag officer of the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He was the first rear admiral, vice admiral, and admiral in the United States Navy. Fa ...

. Blockade runners faced an increasing risk of capture—in 1861 and 1862, one sortie in 9 ended in capture; in 1863 and 1864, one in three. By war's end, imports had been choked to a trickle as the number of captures came to 50% of the sorties. Some 1,100 blockade runners were captured (and another 300 destroyed). British investors frequently made the mistake of reinvesting their profits in the trade; when the war ended they were stuck with useless ships and rapidly depreciating cotton. In the final accounting, perhaps half the investors took a profit, and half a loss.

The Union victory at Vicksburg, Mississippi, in July 1863 opened up the Mississippi River and effectively cut off the western Confederacy as a source of troops and supplies. The fall of Fort Fisher and the city of Wilmington, North Carolina, early in 1865 closed the last major port for blockade runners, and in quick succession Richmond was evacuated, the Army of Northern Virginia disintegrated, and General Lee surrendered. Thus, most economists give the Union blockade a prominent role in the outcome of the war. (Elekund, 2004)

Squadrons

The Union naval ships enforcing the blockade were divided into squadrons based on their area of operation.Atlantic Blockading Squadron

TheAtlantic Blockading Squadron

The Atlantic Blockading Squadron was a unit of the United States Navy created in the early days of the American Civil War to enforce the Union blockade of the ports of the Confederate States. It was formed in 1861 and split up the same year for th ...

was a unit of the United States Navy created in the early days of the American Civil War to enforce a blockade of the ports of the Confederate States. It was originally formed in 1861 as the Coast Blockading Squadron before being renamed May 17, 1861. It was split the same year for the creation of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron and the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron.

North Atlantic Blockading Squadron

The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron was based atHampton Roads, Virginia

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James, Nansemond and Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's Point where the Chesapeake Bay flows into the Atlantic O ...

, and was tasked with coverage of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

and North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

. Its official range of operation was from the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augus ...

to Cape Fear in North Carolina. It was tasked primarily with preventing Confederate ships from supplying troops and with supporting Union troops. It was created when the Atlantic Blockading Squadron

The Atlantic Blockading Squadron was a unit of the United States Navy created in the early days of the American Civil War to enforce the Union blockade of the ports of the Confederate States. It was formed in 1861 and split up the same year for th ...

was split between the North and South Atlantic Blockading Squadrons on 29 October 1861. After the end of the war, the squadron was merged into the Atlantic Squadron on 25 July 1865.

Commanders

South Atlantic Blockading Squadron

The South Atlantic Blockading Squadron was tasked primarily with preventing Confederate ships from supplying troops and with supporting Union troops operating between Cape Henry in Virginia down toKey West

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Island, it cons ...

in Florida. It was created when the Atlantic Blockading Squadron was split between the North and South Atlantic Blockading Squadrons on 29 October 1861. After the end of the war, the squadron was merged into the Atlantic Squadron on 25 July 1865.

Commanders

Gulf Blockading Squadron

The Gulf Blockading Squadron was a squadron of the United States Navy in the early part of the War, patrolling from Key West to the Mexican border. The squadron was the largest in operation. It was split into the East and West Gulf Blockading Squadrons in early 1862 for more efficiency.Commanders

East Gulf Blockading Squadron

The East Gulf Blockading Squadron, assigned the Florida coast from east of Pensacola to Cape Canaveral, was a minor command. The squadron was headquartered inKey West

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Island, it cons ...

and was supported by a U.S. Navy coal depot and storehouse built during 1856–61. With .

Commanders

West Gulf Blockading Squadron

The West Gulf Blockading Squadron was tasked primarily with preventing Confederate ships from supplying troops and with supporting Union troops along the western half of the Gulf Coast, from the mouth of the Mississippi to the Rio Grande and south, beyond the border with Mexico. It was created early in 1862 when the Gulf Blockading Squadron was split between the East and West. This unit was the main military force deployed by the Union in the capture and briefoccupation

Occupation commonly refers to:

*Occupation (human activity), or job, one's role in society, often a regular activity performed for payment

*Occupation (protest), political demonstration by holding public or symbolic spaces

*Military occupation, th ...

of Galveston, Texas

Galveston ( ) is a coastal resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a population of 47,743 in 2010, is the county seat of surrounding Galvesto ...

in 1862.

Commanders

Retrospective consideration

After the war, former Confederate Navy officer andLost Cause

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (or simply Lost Cause) is an American pseudohistorical negationist mythology that claims the cause of the Confederate States during the American Civil War was just, heroic, and not centered on slavery. Firs ...

proponent Raphael Semmes

Raphael Semmes ( ; September 27, 1809 – August 30, 1877) was an officer in the Confederate Navy during the American Civil War. Until then, he had been a serving officer in the US Navy from 1826 to 1860.

During the American Civil War, Semmes wa ...

contended that the announcement of a blockade had carried de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

recognition of the Confederate States of America as an independent national entity since countries do not blockade their own ports but rather ''close'' them ''(See Boston Port Act

The Boston Port Act, also called the Trade Act 1774, was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which became law on March 31, 1774, and took effect on June 1, 1774. It was one of five measures (variously called the ''Intolerable Acts'', the ...

)''. Under international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

and maritime law

Admiralty law or maritime law is a body of law that governs nautical issues and private maritime disputes. Admiralty law consists of both domestic law on maritime activities, and private international law governing the relationships between priva ...

, however, nations had the right to stop and search neutral ships in international waters if they were suspected of violating a blockade, something port closures would not allow. In an effort to avoid conflict between the United States and Britain over the searching of British merchant vessels thought to be trading with the Confederacy, the Union needed the privileges of international law that came with the declaration of a blockade.

However Semmes contends that by effectively declaring the Confederate States of America to be belligerent

A belligerent is an individual, group, country, or other entity that acts in a hostile manner, such as engaging in combat. The term comes from the Latin ''bellum gerere'' ("to wage war"). Unlike the use of ''belligerent'' as an adjective meaning ...

s—rather than insurrection

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

ists, who under international law were not eligible for recognition by foreign powers—Lincoln opened the way for Britain and France to potentially recognize the Confederacy. Britain's proclamation of neutrality was consistent with the Lincoln Administration's position—that under international law the Confederates were belligerents—and helped legitimize the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

's national right to obtain loans and buy arms from neutral nations. The British proclamation also formally gave Britain the diplomatic right to discuss openly which side, if any, to support.

See also

* Bibliography of American Civil War naval history *Confederate Navy

The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the Navy, naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the Confederate States Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the Amer ...

* Blockade mail of the Confederacy

References

Bibliography

**

*

* *

*

Url

* * * Greene, Jack (1998). ''Ironclads at War''; Combined Publishing * McPherson, James M., ''War on the Waters: The Union & Confederate Navies, 1861-1865'' University of North Carolina Press, 2012, * * Surdam, David G. (2001). ''Northern Naval Superiority and the Economics of the American Civil War'';

University of South Carolina Press

The University of South Carolina Press is an academic publisher associated with the University of South Carolina. It was founded in 1944.

By the early 1990s, the press had published several surveys of women's writing in the southern United States ...

* Time-Life Books (1983)'' The Blockade: Runners and Raiders''. ''The Civil War'' series; Time-Life Books, .

* Vandiver, Frank Everson (1947). ''Confederate Blockade Running Through Bermuda, 1861–1865: Letters And Cargo Manifests'', primary documents

* Wagner, Margaret E., Gallagher, Gary W. and Finkelman, Paul ed., (2002) ''The Library of Congress Civil War Desk Reference''Simon & Schuster, New York. *

Url

*

Url1

* Wynne, Nick & Cranshaw, Joe (2011). ''Florida Civil War Blockades''

History Press, Charleston, SC, .

Further reading

*Url

*

Url

External links

''Unintended Consequences of Confederate Trade Legislation''

''The Hapless Anaconda: Union Blockade 1861–1865''

By W. T. Block

* David G. Surdam

Northern Naval Superiority and the Economics of the American Civil War

Egotistigraphy", by John Sanford Barnes. An autobiography, including his Civil War Union Navy service on a ship participating in the blockade, USS ''Wabash'', privately printed 1910. Internet edition edited by Susan Bainbridge Hay 2012

{{DEFAULTSORT:Union Blockade Military operations of the American Civil War Blockades involving the United States Maritime history of the United States 1861 in the American Civil War 1862 in the American Civil War 1863 in the American Civil War 1864 in the American Civil War 1865 in the American Civil War Campaigns of the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War Campaigns of the Lower Seaboard Theater and Gulf Approach of the American Civil War .