South-African on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in

South Africa contains some of the oldest archaeological and human-fossil sites in the world. Archaeologists have recovered extensive fossil remains from a series of caves in

South Africa contains some of the oldest archaeological and human-fossil sites in the world. Archaeologists have recovered extensive fossil remains from a series of caves in

Settlements of Bantu-speaking peoples, who were iron-using agriculturists and herdsmen, were present south of the Limpopo River (now the northern border with

Settlements of Bantu-speaking peoples, who were iron-using agriculturists and herdsmen, were present south of the Limpopo River (now the northern border with

By the early 17th century, Portugal's maritime power was starting to decline, and English and Dutch merchants competed to oust Portugal from its lucrative monopoly on the spice trade. Representatives of the British

By the early 17th century, Portugal's maritime power was starting to decline, and English and Dutch merchants competed to oust Portugal from its lucrative monopoly on the spice trade. Representatives of the British

In the first two decades of the 19th century, the Zulu people grew in power and expanded their territory under their leader, Shaka. Shaka's warfare indirectly led to the ('crushing'), in which one to two million people were killed and the inland plateau was devastated and depopulated in the early 1820s. An offshoot of the Zulu, the Matabele people created a larger empire that included large parts of the

In the first two decades of the 19th century, the Zulu people grew in power and expanded their territory under their leader, Shaka. Shaka's warfare indirectly led to the ('crushing'), in which one to two million people were killed and the inland plateau was devastated and depopulated in the early 1820s. An offshoot of the Zulu, the Matabele people created a larger empire that included large parts of the

The Boer republics successfully resisted British encroachments during the First Boer War (1880–1881) using

The Boer republics successfully resisted British encroachments during the First Boer War (1880–1881) using

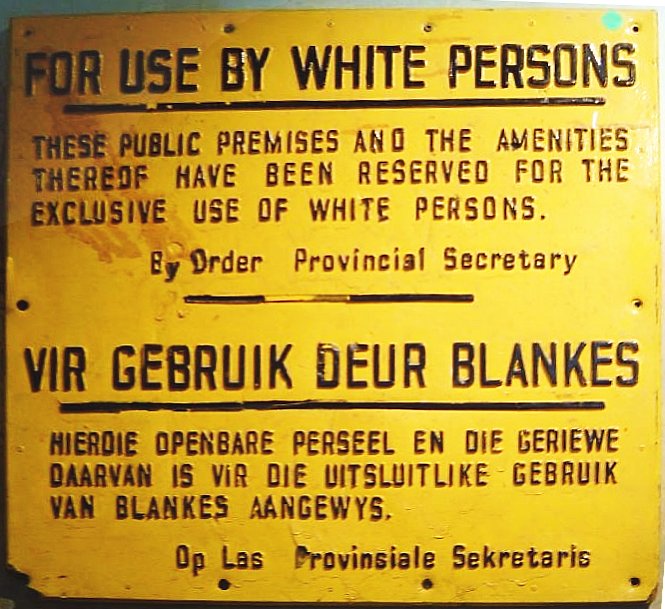

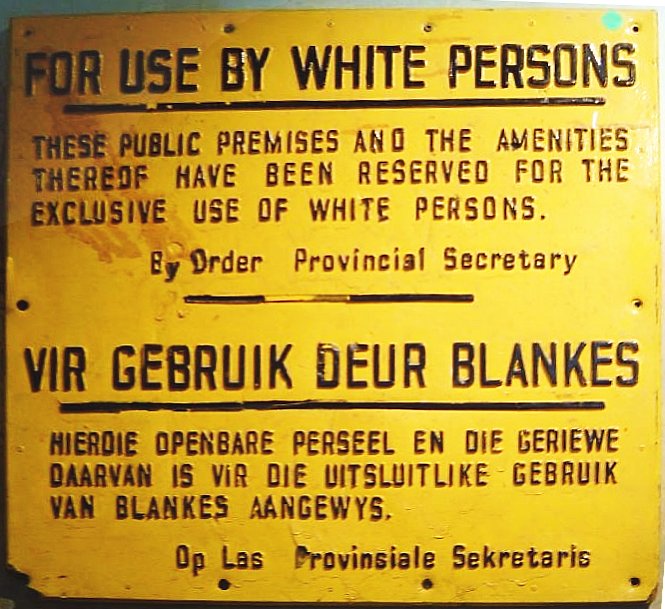

In 1948, the National Party was elected to power. It strengthened the racial segregation begun under Dutch and British colonial rule. Taking Canada's

In 1948, the National Party was elected to power. It strengthened the racial segregation begun under Dutch and British colonial rule. Taking Canada's

The

The

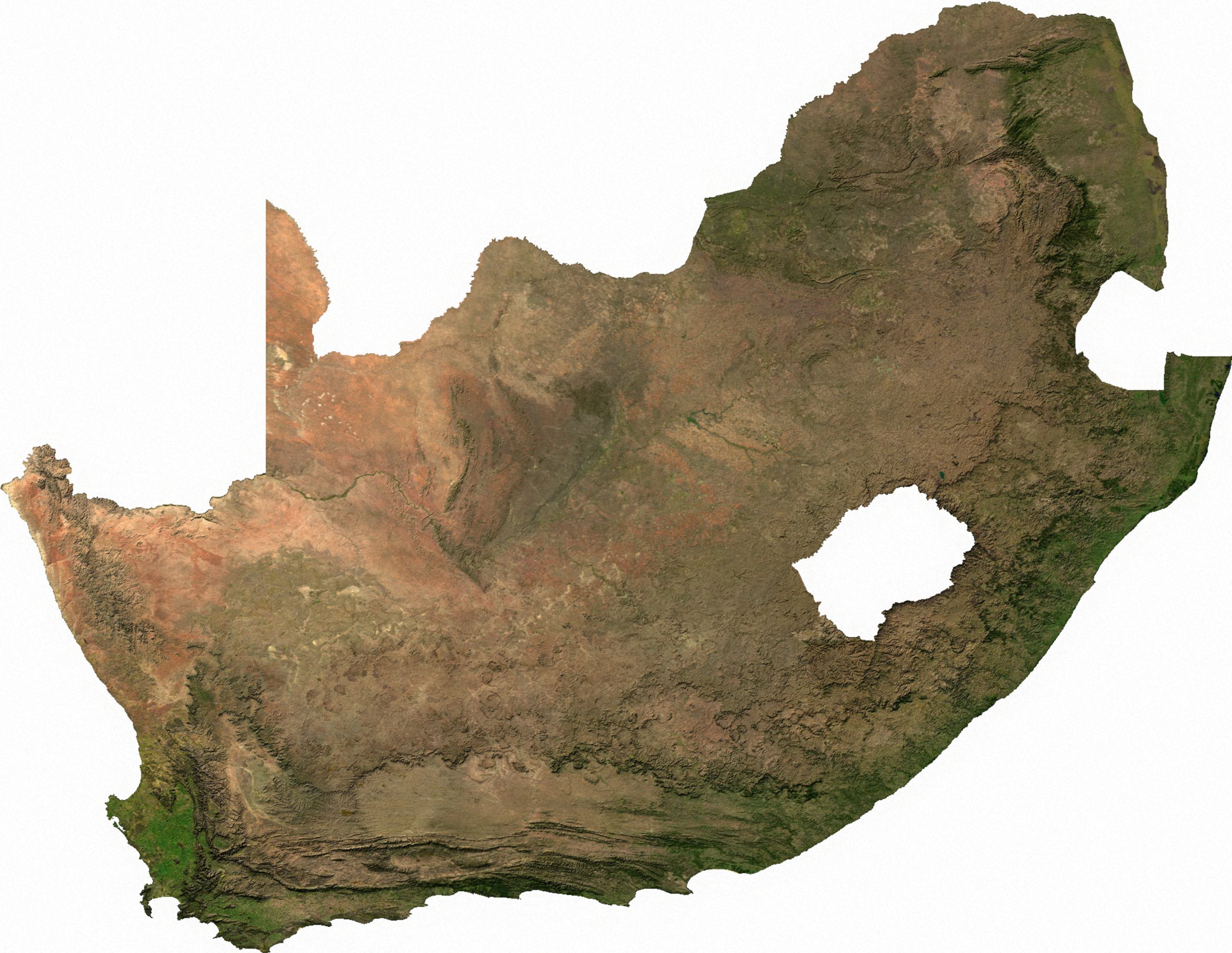

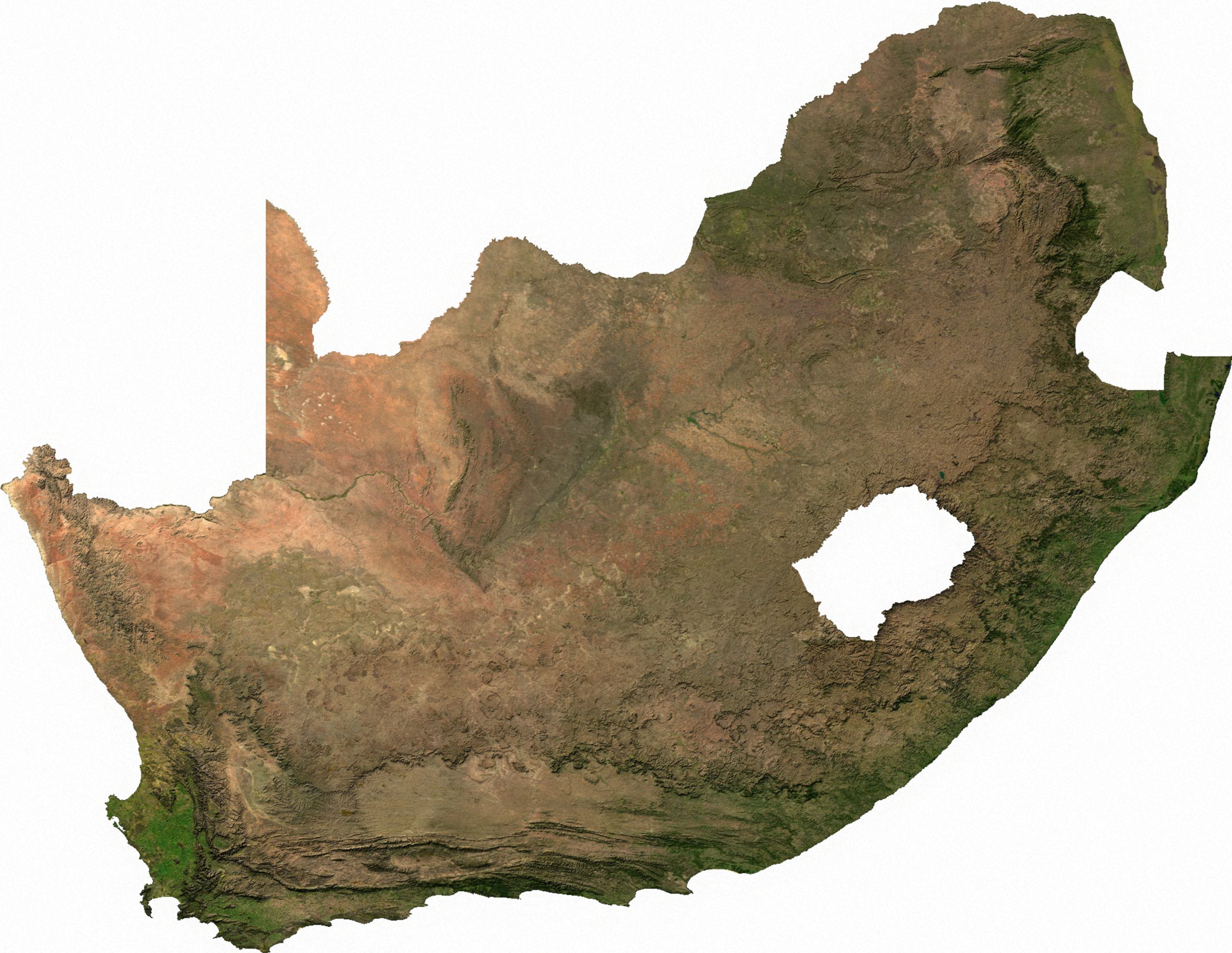

South Africa is in southernmost Africa, with a coastline that stretches more than and along two oceans (the South Atlantic and the Indian). At , South Africa is the 24th-largest country in the world. Excluding the

South Africa is in southernmost Africa, with a coastline that stretches more than and along two oceans (the South Atlantic and the Indian). At , South Africa is the 24th-largest country in the world. Excluding the  The coastal belt below the south and south-western stretches of the Great Escarpment contains several ranges of

The coastal belt below the south and south-western stretches of the Great Escarpment contains several ranges of

South Africa has a generally

South Africa has a generally

National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (NCCAS)

,'' Version UE10, 13 November 2019. This is a critical concern for South Africans as climate change will affect the overall status and wellbeing of the country, for example with regards to

South Africa signed the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity on 4 June 1994 and became a party to the convention on 2 November 1995. It has subsequently produced a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, which was received by the convention on 7 June 2006. The country is ranked sixth out of the world's seventeen megadiverse countries.

South Africa signed the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity on 4 June 1994 and became a party to the convention on 2 November 1995. It has subsequently produced a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, which was received by the convention on 7 June 2006. The country is ranked sixth out of the world's seventeen megadiverse countries.

South Africa has lost a large area of natural habitat in the last four decades, primarily because of overpopulation, sprawling development patterns, and deforestation during the 19th century. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.94/10, ranking it 112th globally out of 172 countries. South Africa is one of the worst affected countries in the world when it comes to invasion by alien species with many (e.g., black wattle, Port Jackson willow, ''

South Africa has lost a large area of natural habitat in the last four decades, primarily because of overpopulation, sprawling development patterns, and deforestation during the 19th century. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.94/10, ranking it 112th globally out of 172 countries. South Africa is one of the worst affected countries in the world when it comes to invasion by alien species with many (e.g., black wattle, Port Jackson willow, ''

South Africa is a nation of about 60 million (as of 2021) people of diverse origins, cultures, languages, and religions. The last

South Africa is a nation of about 60 million (as of 2021) people of diverse origins, cultures, languages, and religions. The last

South Africa has 11 official languages: Zulu, Xhosa,

South Africa has 11 official languages: Zulu, Xhosa,

The adult

The adult

According to the

According to the

South Africa is a

South Africa is a

The South African National Defence Force (SANDF) was created in 1994 as a

The South African National Defence Force (SANDF) was created in 1994 as a

Law enforcement in South Africa is primarily the responsibility of the

Law enforcement in South Africa is primarily the responsibility of the

Each of the nine provinces is governed by a

Each of the nine provinces is governed by a

South Africa has a mixed economy, the third largest in Africa, after Nigeria and Egypt. It also has a relatively high gross domestic product (GDP) per capita compared to other countries in sub-Saharan Africa (US$11,750 at

South Africa has a mixed economy, the third largest in Africa, after Nigeria and Egypt. It also has a relatively high gross domestic product (GDP) per capita compared to other countries in sub-Saharan Africa (US$11,750 at

South Africa has always been a mining powerhouse. Diamond and gold production were in 2013 well down from their peaks, though South Africa is still number five in gold and remains a cornucopia of mineral riches. It is the world's largest producer of

South Africa has always been a mining powerhouse. Diamond and gold production were in 2013 well down from their peaks, though South Africa is still number five in gold and remains a cornucopia of mineral riches. It is the world's largest producer of

From 1995 to 2003, the number of formal jobs decreased and informal jobs increased; overall unemployment worsened. According to data published by the University of Cape Town, between 2017 and the end of 2020, South Africa had lost 56% of its middle-class earners, and the number of ultra-poor who earn below minimum wage had increased by 6.6 million individuals (54%).

The government's Black Economic Empowerment policies have drawn criticism from Neva Makgetla, previous lead economist for research and information at the

From 1995 to 2003, the number of formal jobs decreased and informal jobs increased; overall unemployment worsened. According to data published by the University of Cape Town, between 2017 and the end of 2020, South Africa had lost 56% of its middle-class earners, and the number of ultra-poor who earn below minimum wage had increased by 6.6 million individuals (54%).

The government's Black Economic Empowerment policies have drawn criticism from Neva Makgetla, previous lead economist for research and information at the

South Africa has a very large energy sector and is currently the only country on the African continent that possesses a

South Africa has a very large energy sector and is currently the only country on the African continent that possesses a

Several important scientific and technological developments have originated in South Africa. South Africa was ranked 61st in the

Several important scientific and technological developments have originated in South Africa. South Africa was ranked 61st in the

Different methods of transport in South Africa include roads, railways, airports, water, and pipelines for petroleum oil. The majority of people in South Africa use informal Share taxi, minibus taxis as their main mode of transport. Bus rapid transit has been implemented in some cities in an attempt to provide more formalised and safer public transport services. These systems have been widely criticised because of their large capital and operating costs. South Africa has many major ports including Cape Town, Durban, and Port Elizabeth that allow ships and other boats to pass through, some carrying passengers and some carrying Oil tanker, petroleum tankers.

Different methods of transport in South Africa include roads, railways, airports, water, and pipelines for petroleum oil. The majority of people in South Africa use informal Share taxi, minibus taxis as their main mode of transport. Bus rapid transit has been implemented in some cities in an attempt to provide more formalised and safer public transport services. These systems have been widely criticised because of their large capital and operating costs. South Africa has many major ports including Cape Town, Durban, and Port Elizabeth that allow ships and other boats to pass through, some carrying passengers and some carrying Oil tanker, petroleum tankers.

Data table South Africa

, 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2012 Sanitation access increased from 71% to 79% during the same period. However, water supply and sanitation has come under increasing pressure in recent years despite a commitment made by the government to improve service standards and provide investment subsidies to the water industry. The eastern parts of South Africa suffer from periodic droughts linked to the El Niño weather phenomenon. In early 2018, Cape Town, which has different weather patterns to the rest of the country, faced a water crisis as the city's water supply was predicted to run dry before the end of June. Water-saving measures were in effect that required each citizen to use less than per day. Cape Town rejected an offer from Israel to help it build desalination plants.

South African art includes the oldest art objects in the world, which were discovered in a South African cave and dated from roughly 75,000 years ago. The scattered tribes of the Khoisan peoples moving into South Africa from around 10,000 BC had their own fluent art styles seen today in a multitude of cave paintings. They were superseded by the Bantu/Nguni peoples with their own vocabularies of art forms. Forms of art evolved in the mines and townships: a dynamic art using everything from plastic strips to bicycle spokes. The Dutch-influenced folk art of the Afrikaner Trekboer, and the urban white artists, earnestly following changing European traditions from the 1850s onwards, also contributed to this eclectic mix which continues to evolve to this day.

South African art includes the oldest art objects in the world, which were discovered in a South African cave and dated from roughly 75,000 years ago. The scattered tribes of the Khoisan peoples moving into South Africa from around 10,000 BC had their own fluent art styles seen today in a multitude of cave paintings. They were superseded by the Bantu/Nguni peoples with their own vocabularies of art forms. Forms of art evolved in the mines and townships: a dynamic art using everything from plastic strips to bicycle spokes. The Dutch-influenced folk art of the Afrikaner Trekboer, and the urban white artists, earnestly following changing European traditions from the 1850s onwards, also contributed to this eclectic mix which continues to evolve to this day.

There is great diversity in Music of South Africa, South African music. Black musicians have developed a unique style called Kwaito, that is said to have taken over radio, television, and magazines. Of note is Brenda Fassie, who launched to fame with her song "Weekend Special", which was sung in English. More famous traditional musicians include Ladysmith Black Mambazo, while the Soweto String Quartet performs classical music with an African flavour. South Africa has produced world-famous jazz musicians, notably Hugh Masekela, Jonas Gwangwa, Abdullah Ibrahim, Miriam Makeba, Jonathan Butler, Chris McGregor, and Sathima Bea Benjamin. Afrikaans music covers multiple genres, such as the contemporary Steve Hofmeyr, the punk rock band Fokofpolisiekar, and the singer-songwriter Jeremy Loops. South African popular musicians that have found international success include Manfred Mann (musician) , Manfred Mann, Johnny Clegg, rap-rave duo Die Antwoord, and rock band Seether.

Although few Cinema of South Africa, South African film productions are known outside South Africa, many foreign films have been produced about South Africa. Arguably, the most high-profile film portraying South Africa in recent years was ''District 9'' and its upcoming sequel. Other notable exceptions are the film , which won the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film, Academy Award for Foreign Language Film at the 78th Academy Awards in 2006, as well as , which won the Golden Bear at the 2005 Berlin International Film Festival. In 2015, the Oliver Hermanus film The Endless River (film), ''The Endless River'' became the first South African film selected for the Venice Film Festival.

There is great diversity in Music of South Africa, South African music. Black musicians have developed a unique style called Kwaito, that is said to have taken over radio, television, and magazines. Of note is Brenda Fassie, who launched to fame with her song "Weekend Special", which was sung in English. More famous traditional musicians include Ladysmith Black Mambazo, while the Soweto String Quartet performs classical music with an African flavour. South Africa has produced world-famous jazz musicians, notably Hugh Masekela, Jonas Gwangwa, Abdullah Ibrahim, Miriam Makeba, Jonathan Butler, Chris McGregor, and Sathima Bea Benjamin. Afrikaans music covers multiple genres, such as the contemporary Steve Hofmeyr, the punk rock band Fokofpolisiekar, and the singer-songwriter Jeremy Loops. South African popular musicians that have found international success include Manfred Mann (musician) , Manfred Mann, Johnny Clegg, rap-rave duo Die Antwoord, and rock band Seether.

Although few Cinema of South Africa, South African film productions are known outside South Africa, many foreign films have been produced about South Africa. Arguably, the most high-profile film portraying South Africa in recent years was ''District 9'' and its upcoming sequel. Other notable exceptions are the film , which won the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film, Academy Award for Foreign Language Film at the 78th Academy Awards in 2006, as well as , which won the Golden Bear at the 2005 Berlin International Film Festival. In 2015, the Oliver Hermanus film The Endless River (film), ''The Endless River'' became the first South African film selected for the Venice Film Festival.

South African literature emerged from a unique social and political history. One of the first well known novels written by a black author in an African language was Sol Plaatje, Solomon Thekiso Plaatje's ''Mhudi'', written in 1930. During the 1950s, ''Drum (South African magazine), Drum'' magazine became a hotbed of political satire, fiction, and essays, giving a voice to the urban black culture.

Notable white South African authors include Alan Paton, who published the novel ''Cry, the Beloved Country'' in 1948. Nadine Gordimer became the first South African to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 1991. J. M. Coetzee, J.M. Coetzee won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2003. When awarding the prize, the Swedish Academy stated that Coetzee "in innumerable guises portrays the surprising involvement of the outsider."

The plays of Athol Fugard have been regularly premiered in fringe theatres in South Africa, London (Royal Court Theatre) and New York. Olive Schreiner's ''The Story of an African Farm'' (1883) was a revelation in Victorian literature: it is heralded by many as introducing feminism into the novel form.

Breyten Breytenbach was jailed for his involvement with the guerrilla movement against apartheid. André Brink was the first Afrikaner writer to be banned book, banned by the government after he released the novel ''A Dry White Season (novel), A Dry White Season''.

South African literature emerged from a unique social and political history. One of the first well known novels written by a black author in an African language was Sol Plaatje, Solomon Thekiso Plaatje's ''Mhudi'', written in 1930. During the 1950s, ''Drum (South African magazine), Drum'' magazine became a hotbed of political satire, fiction, and essays, giving a voice to the urban black culture.

Notable white South African authors include Alan Paton, who published the novel ''Cry, the Beloved Country'' in 1948. Nadine Gordimer became the first South African to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 1991. J. M. Coetzee, J.M. Coetzee won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2003. When awarding the prize, the Swedish Academy stated that Coetzee "in innumerable guises portrays the surprising involvement of the outsider."

The plays of Athol Fugard have been regularly premiered in fringe theatres in South Africa, London (Royal Court Theatre) and New York. Olive Schreiner's ''The Story of an African Farm'' (1883) was a revelation in Victorian literature: it is heralded by many as introducing feminism into the novel form.

Breyten Breytenbach was jailed for his involvement with the guerrilla movement against apartheid. André Brink was the first Afrikaner writer to be banned book, banned by the government after he released the novel ''A Dry White Season (novel), A Dry White Season''.

The cuisine of South Africa is immensely diverse, and foods from a many different cultures and backgrounds are enjoyed by all communities, and especially marketed to tourists who wish to sample the large variety available. The cuisine is mostly meat-based and has spawned the distinctively South African social gathering known as the , a variation of the barbecue. South Africa has also developed into a major South African wine, wine producer, with some of the best vineyards lying in valleys around Stellenbosch, Franschhoek, Paarl and Barrydale.

The cuisine of South Africa is immensely diverse, and foods from a many different cultures and backgrounds are enjoyed by all communities, and especially marketed to tourists who wish to sample the large variety available. The cuisine is mostly meat-based and has spawned the distinctively South African social gathering known as the , a variation of the barbecue. South Africa has also developed into a major South African wine, wine producer, with some of the best vineyards lying in valleys around Stellenbosch, Franschhoek, Paarl and Barrydale.

South Africa's most popular sports are association football, rugby union and cricket. Other sports with significant support are swimming, athletics, golf, boxing, tennis, ringball, field hockey, surfing and netball. Although football (soccer) commands the greatest following among the youth, other sports like basketball, judo, softball and skateboarding are becoming increasingly popular amongst the populace.

Association football is the most popular sport in South Africa. Footballers who have played for major foreign clubs include Steven Pienaar, Lucas Radebe and Philemon Masinga, Benni McCarthy, Aaron Mokoena, and Delron Buckley. South Africa hosted the 2010 FIFA World Cup, and FIFA president Sepp Blatter awarded South Africa a grade 9 out of 10 for successfully hosting the event. Player Benni McCarthy is also a first-team coach for the English football club Manchester United F.C., Manchester United.

Famous boxing personalities include Baby Jake Jacob Matlala, Vuyani Bungu, Welcome Ncita, Dingaan Thobela, Corrie Sanders, Gerrie Coetzee and Brian Mitchell (boxer), Brian Mitchell. Durban surfer Jordy Smith won the 2010 Billabong J-Bay Open making him the highest ranked surfer in the world. South Africa produced Formula One motor racing's 1979 world champion Jody Scheckter. Famous active cricket players include Kagiso Rabada, David Miller (South African cricketer), David Miller, Keshav Maharaj, Anrich Nortje, Reeza Hendricks and Rilee Rossouw; some also participate in the Indian Premier League.

South Africa's most popular sports are association football, rugby union and cricket. Other sports with significant support are swimming, athletics, golf, boxing, tennis, ringball, field hockey, surfing and netball. Although football (soccer) commands the greatest following among the youth, other sports like basketball, judo, softball and skateboarding are becoming increasingly popular amongst the populace.

Association football is the most popular sport in South Africa. Footballers who have played for major foreign clubs include Steven Pienaar, Lucas Radebe and Philemon Masinga, Benni McCarthy, Aaron Mokoena, and Delron Buckley. South Africa hosted the 2010 FIFA World Cup, and FIFA president Sepp Blatter awarded South Africa a grade 9 out of 10 for successfully hosting the event. Player Benni McCarthy is also a first-team coach for the English football club Manchester United F.C., Manchester United.

Famous boxing personalities include Baby Jake Jacob Matlala, Vuyani Bungu, Welcome Ncita, Dingaan Thobela, Corrie Sanders, Gerrie Coetzee and Brian Mitchell (boxer), Brian Mitchell. Durban surfer Jordy Smith won the 2010 Billabong J-Bay Open making him the highest ranked surfer in the world. South Africa produced Formula One motor racing's 1979 world champion Jody Scheckter. Famous active cricket players include Kagiso Rabada, David Miller (South African cricketer), David Miller, Keshav Maharaj, Anrich Nortje, Reeza Hendricks and Rilee Rossouw; some also participate in the Indian Premier League.

South Africa has produced numerous world class rugby players, including Francois Pienaar, Joost van der Westhuizen, Danie Craven, Frik du Preez, Naas Botha, and Bryan Habana. South Africa has won the Rugby World Cup three times, tying New Zealand for the most Rugby World Cup wins. South Africa first won the 1995 Rugby World Cup, which it hosted. They went on to win the tournament again in 2007 and in 2019. It followed the 1995 Rugby World Cup by hosting the 1996 African Cup of Nations, with the national team South Africa national soccer team, Bafana Bafana going on to win the tournament. In 2022, the South Africa women's national soccer team, women's team also won the 2022 Women's Africa Cup of Nations, Women's Africa Cup of Nations, beating Morocco women's national football team, Morocco 2–1 in 2022 Women's Africa Cup of Nations Final, the final. It also hosted the 2003 Cricket World Cup, the ICC World Twenty20, 2007 World Twenty20 Championship. South Africa's national cricket team, the South Africa national cricket team, Proteas, have also won the inaugural edition of the 1998 ICC KnockOut Trophy by defeating West Indies national cricket team, West Indies in the final. South Africa national blind cricket team, South Africa's national blind cricket team also went on to win the inaugural edition of the Blind Cricket World Cup in 1998.

In 2004, the swimming team of Roland Schoeman, Lyndon Ferns, Darian Townsend and Ryk Neethling won the gold medal at the 2004 Summer Olympics, Olympic Games in Athens, simultaneously breaking the world record in the 4×100 Freestyle Relay. Penny Heyns won Olympic Gold in the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games, and more recently, swimmers Tatjana Schoenmaker and Lara van Niekerk have both broken world records and won gold medals at the Olympic and Commonwealth Games. In 2012, Oscar Pistorius became the first double amputee sprinter to compete at the 2012 Summer Olympics, Olympic Games in London. In golf, Gary Player is generally regarded as one of the greatest golfers of all time, having won the Grand Slam (golf), Career Grand Slam, one of five golfers to have done so. Other South African golfers to have won major tournaments include Bobby Locke, Ernie Els, Retief Goosen, Tim Clark (golfer), Tim Clark, Trevor Immelman, Louis Oosthuizen and Charl Schwartzel.

South Africa has produced numerous world class rugby players, including Francois Pienaar, Joost van der Westhuizen, Danie Craven, Frik du Preez, Naas Botha, and Bryan Habana. South Africa has won the Rugby World Cup three times, tying New Zealand for the most Rugby World Cup wins. South Africa first won the 1995 Rugby World Cup, which it hosted. They went on to win the tournament again in 2007 and in 2019. It followed the 1995 Rugby World Cup by hosting the 1996 African Cup of Nations, with the national team South Africa national soccer team, Bafana Bafana going on to win the tournament. In 2022, the South Africa women's national soccer team, women's team also won the 2022 Women's Africa Cup of Nations, Women's Africa Cup of Nations, beating Morocco women's national football team, Morocco 2–1 in 2022 Women's Africa Cup of Nations Final, the final. It also hosted the 2003 Cricket World Cup, the ICC World Twenty20, 2007 World Twenty20 Championship. South Africa's national cricket team, the South Africa national cricket team, Proteas, have also won the inaugural edition of the 1998 ICC KnockOut Trophy by defeating West Indies national cricket team, West Indies in the final. South Africa national blind cricket team, South Africa's national blind cricket team also went on to win the inaugural edition of the Blind Cricket World Cup in 1998.

In 2004, the swimming team of Roland Schoeman, Lyndon Ferns, Darian Townsend and Ryk Neethling won the gold medal at the 2004 Summer Olympics, Olympic Games in Athens, simultaneously breaking the world record in the 4×100 Freestyle Relay. Penny Heyns won Olympic Gold in the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games, and more recently, swimmers Tatjana Schoenmaker and Lara van Niekerk have both broken world records and won gold medals at the Olympic and Commonwealth Games. In 2012, Oscar Pistorius became the first double amputee sprinter to compete at the 2012 Summer Olympics, Olympic Games in London. In golf, Gary Player is generally regarded as one of the greatest golfers of all time, having won the Grand Slam (golf), Career Grand Slam, one of five golfers to have done so. Other South African golfers to have won major tournaments include Bobby Locke, Ernie Els, Retief Goosen, Tim Clark (golfer), Tim Clark, Trevor Immelman, Louis Oosthuizen and Charl Schwartzel.

Government of South Africa

South Africa

''The World Factbook''. Central Intelligence Agency.

South Africa

from ''UCB Libraries GovPubs''

South Africa

from the BBC News * * {{Authority control South Africa BRICS nations Countries in Africa English-speaking countries and territories G20 nations Member states of the African Union Member states of the Commonwealth of Nations Member states of the United Nations Newly industrializing countries Republics in the Commonwealth of Nations Southern African countries States and territories established in 1910

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

and Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by th ...

s; to the north by the neighbouring countries of Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

, Botswana

Botswana (, ), officially the Republic of Botswana ( tn, Lefatshe la Botswana, label=Setswana, ), is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. Botswana is topographically flat, with approximately 70 percent of its territory being the Kalahar ...

, and Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and Mozam ...

; and to the east and northeast by Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

and Eswatini

Eswatini ( ; ss, eSwatini ), officially the Kingdom of Eswatini and formerly named Swaziland ( ; officially renamed in 2018), is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. It is bordered by Mozambique to its northeast and South Africa to its no ...

. It also completely enclaves

An enclave is a territory (or a small territory apart of a larger one) that is entirely surrounded by the territory of one other state or entity. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is sometimes used improperly to deno ...

the country Lesotho

Lesotho ( ), officially the Kingdom of Lesotho, is a country landlocked country, landlocked as an Enclave and exclave, enclave in South Africa. It is situated in the Maloti Mountains and contains the Thabana Ntlenyana, highest mountains in Sou ...

. It is the southernmost country on the mainland of the Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by the ...

, and the second-most populous country located entirely south of the equator, after Tanzania. South Africa is a biodiversity hotspot, with unique biomes, plant and animal life. With over 60 million people, the country is the world's 24th-most populous nation and covers an area of . South Africa has three capital cities, with the executive, judicial and legislative branches of government based in Pretoria

Pretoria () is South Africa's administrative capital, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to South Africa.

Pretoria straddles the Apies River and extends ...

, Bloemfontein, and Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

respectively. The largest city is Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu and xh, eGoli ), colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, or "The City of Gold", is the largest city in South Africa, classified as a megacity, and is one of the 100 largest urban areas in the world. According to Demo ...

.

About 80% of the population are Black South Africans

Racial groups in South Africa have a variety of origins. The Race (classification of human beings), racial categories introduced by Apartheid remain ingrained in South African society with South Africans and the South African government contin ...

. The remaining population consists of Africa's largest communities of European (White South Africans

White South Africans generally refers to South Africans of European descent. In linguistic, cultural, and historical terms, they are generally divided into the Afrikaans-speaking descendants of the Dutch East India Company's original settlers, ...

), Asian (Indian South Africans

Indian South Africans are South Africans who descend from indentured labourers and free migrants who arrived from British India during the late 1800s and early 1900s. The majority live in and around the city of Durban, making it one of the l ...

and Chinese South Africans), and multiracial ( Coloured South Africans) ancestry. South Africa is a multiethnic society encompassing a wide variety of cultures, languages

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of met ...

, and religions

Religion is usually defined as a social-cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, tran ...

. Its pluralistic makeup is reflected in the constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

's recognition of 11 official languages, the fourth-highest number in the world. According to the 2011 census, the two most spoken first languages are Zulu (22.7%) and Xhosa (16.0%). The two next ones are of European origin: Afrikaans

Afrikaans (, ) is a West Germanic language that evolved in the Dutch Cape Colony from the Dutch vernacular of Holland proper (i.e., the Hollandic dialect) used by Dutch, French, and German settlers and their enslaved people. Afrikaans gra ...

(13.5%) developed from Dutch and serves as the first language of most Coloured and White South Africans; English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

(9.6%) reflects the legacy of British colonialism and is commonly used in public and commercial life.

The country is one of the few in Africa never to have had a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

, and regular elections have been held for almost a century. However, the vast majority of Black South Africans were not enfranchised

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

until 1994. During the 20th century, the black majority sought to claim more rights from the dominant white minority, which played a large role in the country's recent history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

and politics. The National Party imposed apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

in 1948, institutionalising previous racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

. After a long and sometimes violent struggle by the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a Social democracy, social-democratic political party in Republic of South Africa, South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when ...

and other anti-apartheid activists both inside and outside the country, the repeal of discriminatory laws began in the mid-1980s. Since 1994, all ethnic and linguistic groups have held political representation in the country's liberal democracy

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into diff ...

, which comprises a parliamentary republic

A parliamentary republic is a republic that operates under a parliamentary system of government where the executive branch (the government) derives its legitimacy from and is accountable to the legislature (the parliament). There are a number ...

and nine provinces

The term Nine Provinces or Nine Regions (), is used in ancient Chinese histories to refer to territorial divisions or islands during the Xia and Shang dynasties and has now come to symbolically represent China. "Province" is the word used to t ...

. South Africa is often referred to as the " rainbow nation" to describe the country's multicultural diversity, especially in the wake of apartheid.

South Africa is a middle power in international affairs; it maintains significant regional influence and is a member of both the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

and the G20

The G20 or Group of Twenty is an intergovernmental forum comprising 19 countries and the European Union (EU). It works to address major issues related to the global economy, such as international financial stability, climate change mitigation, ...

. It is a developing country

A developing country is a sovereign state with a lesser developed industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to other countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is also no clear agreem ...

, ranking 109th on the Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a statistic composite index of life expectancy, education (mean years of schooling completed and expected years of schooling upon entering the education system), and per capita income indicators, whi ...

, the 2nd highest in Africa. It has been classified by the World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and grants to the governments of low- and middle-income countries for the purpose of pursuing capital projects. The World Bank is the collective name for the Interna ...

as a newly industrialised country

The category of newly industrialized country (NIC), newly industrialized economy (NIE) or middle income country is a socioeconomic classification applied to several countries around the world by political scientists and economists. They represent ...

and has the third-largest economy in Africa and the most industrialized, technologically advanced economy in Africa overall as well as the 39th-largest in the world. South Africa has the most UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Africa. Since the end of apartheid, government accountability and quality of life have substantially improved. However, crime

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a State (polity), state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definit ...

, poverty and inequality remain widespread, with about two-fifths of the total population being unemployed , while some three-fifths of the population lived under the poverty line in 2014 and a quarter under $2.15 a day.

Etymology

The name "South Africa" is derived from the country's geographic location at the southern tip of Africa. Upon formation, the country was named theUnion of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Trans ...

in English and in Dutch, reflecting its origin from the unification of four formerly separate British colonies. Since 1961, the long formal name in English has been the "Republic of South Africa" and in Afrikaans

Afrikaans (, ) is a West Germanic language that evolved in the Dutch Cape Colony from the Dutch vernacular of Holland proper (i.e., the Hollandic dialect) used by Dutch, French, and German settlers and their enslaved people. Afrikaans gra ...

. Since 1994, the country has had an official name in each of its 11 official languages.

Mzansi, derived from the Xhosa noun meaning "south", is a colloquial name

Colloquialism (), also called colloquial language, everyday language or general parlance, is the linguistic style used for casual (informal) communication. It is the most common functional style of speech, the idiom normally employed in conversa ...

for South Africa, while some Pan-Africanist

Pan-Africanism is a worldwide movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous and diaspora peoples of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atlantic slave trade, the movement exte ...

political parties prefer the term "Azania

Azania ( grc, Ἀζανία) is a name that has been applied to various parts of southeastern tropical Africa. In the Roman period and perhaps earlier, the toponym referred to a portion of the Southeast Africa coast extending from northern Kenya ...

".

History

Prehistoric archaeology

South Africa contains some of the oldest archaeological and human-fossil sites in the world. Archaeologists have recovered extensive fossil remains from a series of caves in

South Africa contains some of the oldest archaeological and human-fossil sites in the world. Archaeologists have recovered extensive fossil remains from a series of caves in Gauteng

Gauteng ( ) is one of the nine provinces of South Africa. The name in Sotho-Tswana languages means 'place of gold'.

Situated on the Highveld, Gauteng is the smallest province by land area in South Africa. Although Gauteng accounts for only ...

Province. The area, a UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

, has been branded "the Cradle of Humankind

The Cradle of Humankind is a paleoanthropological site and is located about northwest of Johannesburg, South Africa, in the Gauteng province. Declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1999, the site is home to the largest concentration of ...

". The sites include Sterkfontein

Sterkfontein (Afrikaans for ''Strong Spring'') is a set of limestone caves of special interest to paleo-anthropologists located in Gauteng province, about northwest of Johannesburg, South Africa in the Muldersdrift area close to the town of K ...

, one of the richest sites for hominin

The Hominini form a taxonomic tribe of the subfamily Homininae ("hominines"). Hominini includes the extant genera ''Homo'' (humans) and '' Pan'' (chimpanzees and bonobos) and in standard usage excludes the genus ''Gorilla'' (gorillas).

The t ...

fossils in the world, as well as Swartkrans, Gondolin Cave

Gondolin Cave is a fossiliferous dolomitic paleocave system in the Northwest Province, South Africa. The paleocave formed in the Eccles Formation dolomites ( Malmani Subgroup, Chuniespoort Group carbonate-banded iron formation marine platform). G ...

, Kromdraai

Kromdraai Conservancy is a protected conservation park located to the south-west of Gauteng province in north-east South Africa. It is in the Muldersdrift area not far from Krugersdorp.

Etymology

Its name is derived from Afrikaans meaning "Cro ...

, Cooper's Cave

Cooper's Cave is a series of fossil-bearing breccia filled cavities. The cave is located almost exactly between the well known South African hominid-bearing sites of Sterkfontein and Kromdraai and about northwest of Johannesburg, South Africa an ...

and Malapa

Malapa is a fossil-bearing cave located about northeast of the well known South African hominid-bearing sites of Sterkfontein and Swartkrans and about north-northwest of Johannesburg, South Africa. It is situated within the Cradle of Human ...

. Raymond Dart

Raymond Arthur Dart (4 February 1893 – 22 November 1988) was an Australian anatomist and anthropologist, best known for his involvement in the 1924 discovery of the first fossil ever found of ''Australopithecus africanus'', an extinct homi ...

identified the first hominin fossil discovered in Africa, the Taung Child

The Taung Child (or Taung Baby) is the fossilised skull of a young ''Australopithecus africanus''. It was discovered in 1924 by quarrymen working for the Northern Lime Company in Taung, South Africa. Raymond Dart described it as a new species ...

(found near Taung) in 1924. Other hominin remains have come from the sites of Makapansgat in Limpopo

Limpopo is the northernmost province of South Africa. It is named after the Limpopo River, which forms the province's western and northern borders. The capital and largest city in the province is Polokwane, while the provincial legislature is ...

Province; Cornelia and Florisbad in Free State Province; Border Cave in KwaZulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal (, also referred to as KZN and known as "the garden province") is a province of South Africa that was created in 1994 when the Zulu bantustan of KwaZulu ("Place of the Zulu" in Zulu) and Natal Province were merged. It is locate ...

Province; Klasies River Caves in Eastern Cape

The Eastern Cape is one of the provinces of South Africa. Its capital is Bhisho, but its two largest cities are East London and Gqeberha.

The second largest province in the country (at 168,966 km2) after Northern Cape, it was formed in ...

Province; and Pinnacle Point

Pinnacle Point a small promontory immediately south of Mossel Bay, a town on the southern coast of South Africa. Excavations since the year 2000 of a series of caves at Pinnacle Point have revealed occupation by Middle Stone Age people between ...

, Elandsfontein Elandsfontein may refer to:

* Elandsfontein, an archaeological site near Hopefield, South Africa

* Elandsfontein, a farm homestead that is now a suburb of Alberton, South Africa

{{disambiguation ...

and Die Kelders Cave in Western Cape

The Western Cape is a province of South Africa, situated on the south-western coast of the country. It is the fourth largest of the nine provinces with an area of , and the third most populous, with an estimated 7 million inhabitants in 2020 ...

Province.

These finds suggest that various hominid species existed in South Africa from about three million years ago, starting with ''Australopithecus africanus

''Australopithecus africanus'' is an extinct species of australopithecine which lived between about 3.3 and 2.1 million years ago in the Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene of South Africa. The species has been recovered from Taung, Sterkfonte ...

,'' followed by ''Australopithecus sediba

''Australopithecus sediba'' is an extinct species of australopithecine recovered from Malapa Cave, Cradle of Humankind, South Africa. It is known from a partial juvenile skeleton, the holotype MH1, and a partial adult female skeleton, the para ...

'', '' Homo ergaster'', ''Homo erectus

''Homo erectus'' (; meaning "upright man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Pleistocene, with its earliest occurrence about 2 million years ago. Several human species, such as '' H. heidelbergensis'' and '' H. antecessor' ...

'', '' Homo rhodesiensis'', ''Homo helmei

The Florisbad Skull is an important human fossil of the early Middle Stone Age, representing either late ''Homo heidelbergensis'' or early ''Homo sapiens''.

It was discovered in 1932 by T. F. Dreyer at the Florisbad site, Free State Province, ...

'', '' Homo naledi'' and modern human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

s (''Homo sapiens''). Modern humans have inhabited Southern Africa for at least 170,000 years. Various researchers have located pebble tools

A pebble is a clast of rock with a particle size of based on the Udden-Wentworth scale of sedimentology. Pebbles are generally considered larger than granules ( in diameter) and smaller than cobbles ( in diameter). A rock made predominan ...

within the Vaal River valley.

Bantu expansion

Settlements of Bantu-speaking peoples, who were iron-using agriculturists and herdsmen, were present south of the Limpopo River (now the northern border with

Settlements of Bantu-speaking peoples, who were iron-using agriculturists and herdsmen, were present south of the Limpopo River (now the northern border with Botswana

Botswana (, ), officially the Republic of Botswana ( tn, Lefatshe la Botswana, label=Setswana, ), is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. Botswana is topographically flat, with approximately 70 percent of its territory being the Kalahar ...

and Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and Mozam ...

) by the 4th or 5th century CE. They displaced, conquered, and absorbed the original Khoisan

Khoisan , or (), according to the contemporary Khoekhoegowab orthography, is a catch-all term for those indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who do not speak one of the Bantu languages, combining the (formerly "Khoikhoi") and the or ( in t ...

, Khoikhoi and San peoples. The Bantu slowly moved south. The earliest ironworks

An ironworks or iron works is an industrial plant where iron is smelted and where heavy iron and steel products are made. The term is both singular and plural, i.e. the singular of ''ironworks'' is ''ironworks''.

Ironworks succeeded bloomeri ...

in modern-day KwaZulu-Natal Province

KwaZulu-Natal (, also referred to as KZN and known as "the garden province") is a province of South Africa that was created in 1994 when the Zulu bantustan of KwaZulu ("Place of the Zulu" in Zulu) and Natal Province were merged. It is locat ...

are believed to date from around 1050. The southernmost group was the Xhosa people

The Xhosa people, or Xhosa language, Xhosa-speaking people (; ) are African people who are direct kinsmen of Tswana people, Sotho people and Twa people, yet are narrowly sub grouped by European as Nguni people, Nguni ethnic group whose traditi ...

, whose language incorporates certain linguistic traits from the earlier Khoisan people. The Xhosa reached the Great Fish River

The Great Fish River (called ''great'' to distinguish it from the Namibian Fish River) ( af, Groot-Visrivier) is a river running through the South African province of the Eastern Cape. The coastal area between Port Elizabeth and the Fish Riv ...

, in today's Eastern Cape Province. As they migrated, these larger Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

populations displaced or assimilated earlier peoples. In Mpumalanga

Mpumalanga () is a province of South Africa. The name means "East", or literally "The Place Where the Sun Rises" in the Swazi, Xhosa, Ndebele and Zulu languages. Mpumalanga lies in eastern South Africa, bordering Eswatini and Mozambique. It ...

Province, several stone circles have been found along with a stone arrangement that has been named Adam's Calendar, and the ruins are thought to be created by the Bakone, a Northern Sotho people.

Portuguese exploration

In 1487, the Portuguese explorerBartolomeu Dias

Bartolomeu Dias ( 1450 – 29 May 1500) was a Portuguese mariner and explorer. In 1488, he became the first European navigator to round the southern tip of Africa and to demonstrate that the most effective southward route for ships lay in the o ...

led the first European voyage to land in southern Africa. On 4 December, he landed at Walfisch Bay (now known as Walvis Bay in present-day Namibia). This was south of the furthest point reached in 1485 by his predecessor, the Portuguese navigator Diogo Cão

Diogo Cão (; -1486), anglicised as Diogo Cam and also known as Diego Cam, was a Portuguese explorer and one of the most notable navigators of the Age of Discovery. He made two voyages sailing along the west coast of Africa in the 1480s, explorin ...

(Cape Cross

Cape Cross (Afrikaans: ''Kaap Kruis''; German: ''Kreuzkap''; Portuguese: ''Cabo da Cruz'') is a headland in the South Atlantic in Skeleton Coast, western Namibia.

History

In 1484, Portuguese navigator and explorer Diogo Cão was ordered by Ki ...

, north of the bay). Dias continued down the western coast of southern Africa. After 8 January 1488, prevented by storms from proceeding along the coast, he sailed out of sight of land and passed the southernmost point of Africa without seeing it. He reached as far up the eastern coast of Africa as, what he called, , probably the present-day Groot River

Groot River or Grootrivier, meaning "large river", may refer to:

* Groot River (Eastern Cape), a tributary of the Gamtoos River (South Africa)

* Groot River (Southern Cape), a tributary of the Gourits River (South Africa)

* Groot River (Western C ...

, in May 1488. On his return he saw the cape, which he named ('Cape of Storms'). King John II John II may refer to:

People

* John Cicero, Elector of Brandenburg (1455–1499)

* John II Casimir Vasa of Poland (1609–1672)

* John II Comyn, Lord of Badenoch (died 1302)

* John II Doukas of Thessaly (1303–1318)

* John II Komnenos (1087–1 ...

renamed the point , or Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

, as it led to the riches of the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around t ...

. Dias' feat of navigation was immortalised in Luís de Camões' 1572 epic poem '' Os Lusíadas''.

Dutch colonisation

By the early 17th century, Portugal's maritime power was starting to decline, and English and Dutch merchants competed to oust Portugal from its lucrative monopoly on the spice trade. Representatives of the British

By the early 17th century, Portugal's maritime power was starting to decline, and English and Dutch merchants competed to oust Portugal from its lucrative monopoly on the spice trade. Representatives of the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

sporadically called at the cape in search of provisions as early as 1601 but later came to favour Ascension Island

Ascension Island is an isolated volcanic island, 7°56′ south of the Equator in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is about from the coast of Africa and from the coast of South America. It is governed as part of the British Overseas Territory o ...

and Saint Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constitu ...

as alternative ports of refuge. Dutch interest was aroused after 1647, when two employees of the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

were shipwrecked at the cape for several months. The sailors were able to survive by obtaining fresh water and meat from the natives. They also sowed vegetables in the fertile soil. Upon their return to Holland, they reported favourably on the cape's potential as a "warehouse and garden" for provisions to stock passing ships for long voyages.

In 1652, a century and a half after the discovery of the cape sea route, Jan van Riebeeck

Johan Anthoniszoon "Jan" van Riebeeck (21 April 1619 – 18 January 1677) was a Dutch navigator and colonial administrator of the Dutch East India Company.

Life

Early life

Jan van Riebeeck was born in Culemborg, as the son of a surgeon. He ...

established a station at the Cape of Good Hope, at what would become Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

, on behalf of the Dutch East India Company. In time, the cape became home to a large population of , also known as (), former company employees who stayed in Dutch territories overseas after serving their contracts. Dutch traders also brought thousands of enslaved people to the fledgling colony from Indonesia, Madagascar, and parts of eastern Africa. Some of the earliest mixed race communities in the country were formed between , enslaved people, and indigenous peoples. This led to the development of a new ethnic group, the Cape Coloureds, most of whom adopted the Dutch language and Christian faith.

The eastward expansion of Dutch colonists ushered in a series of wars with the southwesterly migrating Xhosa tribe, known as the Xhosa Wars

The Xhosa Wars (also known as the Cape Frontier Wars or the Kaffir Wars) were a series of nine wars (from 1779 to 1879) between the Xhosa people, Xhosa Kingdom and the British Empire as well as Trekboers in what is now the Eastern Cape in Sout ...

, as both sides competed for the pastureland near the Great Fish River, which the colonists desired for grazing cattle. ''Vrijburgers'' who became independent farmers on the frontier were known as ''Boers

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled this area ...

'', with some adopting semi-nomadic lifestyles being denoted as . The Boers formed loose militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

s, which they termed ''commandos'', and forged alliances with Khoisan peoples to repel Xhosa raids. Both sides launched bloody but inconclusive offensives, and sporadic violence, often accompanied by livestock theft, remained common for several decades.

British colonisation and the Great Trek

Great Britain occupied Cape Town between 1795 and 1803 to prevent it from falling under the control of theFrench First Republic

In the history of France, the First Republic (french: Première République), sometimes referred to in historiography as Revolutionary France, and officially the French Republic (french: République française), was founded on 21 September 1792 ...

, which had invaded the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

. After briefly returning to Dutch rule under the Batavian Republic

The Batavian Republic ( nl, Bataafse Republiek; french: République Batave) was the successor state to the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. It was proclaimed on 19 January 1795 and ended on 5 June 1806, with the accession of Louis Bona ...

in 1803, the cape was occupied again by the British in 1806. Following the end of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, it was formally ceded to Great Britain and became an integral part of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

. British emigration to South Africa began around 1818, subsequently culminating in the arrival of the 1820 Settlers

The 1820 Settlers were several groups of British colonists from England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales, settled by the government of the United Kingdom and the Cape Colony authorities in the Eastern Cape of South Africa in 1820.

Origins

After th ...

. The new colonists were induced to settle for a variety of reasons, namely to increase the size of the European workforce and to bolster frontier regions against Xhosa incursions.

In the first two decades of the 19th century, the Zulu people grew in power and expanded their territory under their leader, Shaka. Shaka's warfare indirectly led to the ('crushing'), in which one to two million people were killed and the inland plateau was devastated and depopulated in the early 1820s. An offshoot of the Zulu, the Matabele people created a larger empire that included large parts of the

In the first two decades of the 19th century, the Zulu people grew in power and expanded their territory under their leader, Shaka. Shaka's warfare indirectly led to the ('crushing'), in which one to two million people were killed and the inland plateau was devastated and depopulated in the early 1820s. An offshoot of the Zulu, the Matabele people created a larger empire that included large parts of the highveld

The Highveld (Afrikaans: ''Hoëveld'', where ''veld'' means "field") is the portion of the South African inland plateau which has an altitude above roughly 1500 m, but below 2100 m, thus excluding the Lesotho mountain regions to the south-east of ...

under their king Mzilikazi.

During the early 19th century, many Dutch settlers departed from the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when i ...

, where they had been subjected to British control, in a series of migrant groups who came to be known as , meaning "pathfinders" or "pioneers". They migrated to the future Natal, Free State, and Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

regions. The Boers founded the Boer republics: the South African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it ...

, the Natalia Republic

The Natalia Republic was a short-lived Boer republic founded in 1839 after a Voortrekker victory against the Zulus at the Battle of Blood River. The area was previously named ''Natália'' by Portuguese sailors, due to its discovery on Christma ...

, and the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

.

The discovery of diamonds in 1867 and gold in 1884 in the interior started the Mineral Revolution

The Mineral Revolution is a term used by historians to refer to the rapid industrialisation and economic changes which occurred in South Africa from the 1860s onwards. The Mineral Revolution was largely driven by the need to create a permanen ...

and increased economic growth and immigration. This intensified British efforts to gain control over the indigenous peoples. The struggle to control these important economic resources was a factor in relations between Europeans and the indigenous population and also between the Boers and the British.

On 16 May 1876, President Thomas François Burgers of the South African Republic declared war against the Pedi people. King Sekhukhune

Sekhukhune I (Matsebe; circa 1814 – 13 August 1882) was the paramount King of the Marota, more commonly known as the Bapedi, from 21 September 1861 until his assassination on 13 August 1882 by his rival and half-brother, Mampuru II. As the Pedi ...

managed to defeat the army on 1 August 1876. Another attack by the Lydenburg Volunteer Corps was also repulsed. On 16 February 1877, the two parties signed a peace treaty at Botshabelo. The Boers' inability to subdue the Pedi led to the departure of Burgers in favour of Paul Kruger

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger (; 10 October 1825 – 14 July 1904) was a South African politician. He was one of the dominant political and military figures in 19th-century South Africa, and President of the South African Republic (or ...

and the British annexation of the South African Republic. In 1878 and 1879 three British attacks were successfully repelled until Garnet Wolseley defeated Sekhukhune in November 1879 with an army of 2,000 British soldiers, Boers and 10,000 Swazis.

The Anglo-Zulu War

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Following the passing of the British North America Act of 1867 forming a federation in Canada, Lord Carnarvon thought that a similar political effort, coupl ...

was fought in 1879 between the British and the Zulu Kingdom

The Zulu Kingdom (, ), sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire or the Kingdom of Zululand, was a monarchy in Southern Africa. During the 1810s, Shaka established a modern standing army that consolidated rival clans and built a large following ...

. Following Lord Carnarvon

Earl of Carnarvon is a title that has been created three times in British history. The current holder is George Herbert, 8th Earl of Carnarvon. The town and county in Wales to which the title refers are historically spelled ''Caernarfon,'' havi ...

's successful introduction of federation in Canada, it was thought that similar political effort, coupled with military campaigns, might succeed with the African kingdoms, tribal areas and Boer republics in South Africa. In 1874, Henry Bartle Frere

Sir Henry Bartle Edward Frere, 1st Baronet, (29 March 1815 – 29 May 1884) was a Welsh British colonial administrator. He had a successful career in India, rising to become Governor of Bombay (1862–1867). However, as High Commissioner for ...

was sent to South Africa as the British High Commissioner to bring such plans into being. Among the obstacles were the presence of the independent states of the Boers, and the Zululand army. The Zulu nation defeated the British at the Battle of Isandlwana

The Battle of Isandlwana (alternative spelling: Isandhlwana) on 22 January 1879 was the first major encounter in the Anglo-Zulu War between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Eleven days after the British commenced their invasion of Zulul ...

. Eventually, though, Zululand lost the war, resulting in the termination of the Zulu nation's independence.

Boer Wars

The Boer republics successfully resisted British encroachments during the First Boer War (1880–1881) using

The Boer republics successfully resisted British encroachments during the First Boer War (1880–1881) using guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or Irregular military, irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, Raid (military), raids ...

tactics, which were well-suited to local conditions. The British returned with greater numbers, more experience, and new strategy in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

(1899–1902) and, although they suffered heavy casualties through attrition

Attrition may refer to

*Attrition warfare, the military strategy of wearing down the enemy by continual losses in personnel and material

**War of Attrition, fought between Egypt and Israel from 1968 to 1970

**War of attrition (game), a model of agg ...

, they were ultimately successful. Over 27,000 Boer women and children died in the British concentration camps.

South Africa's urban population grew rapidly from the end of the 19th century onward. After the devastation of the wars, Dutch-descendant Boer farmers fled into cities from the devastated Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

and Orange Free State territories to become the class of the white urban poor.

Independence

Anti-British policies among white South Africans focused on independence. During the Dutch and British colonial years,racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

was mostly informal, though some legislation was enacted to control the settlement and movement of indigenous people, including the Native Location Act of 1879

The ''Native Location Act of 1879'' was an act of racial segregation in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretc ...

and the system of pass laws

In South Africa, pass laws were a form of internal passport system designed to segregate the population, manage urbanization and allocate migrant labor. Also known as the natives' law, pass laws severely limited the movements of not only black ...

.

Eight years after the end of the Second Boer War and after four years of negotiation, the South Africa Act 1909

The South Africa Act 1909 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which created the Union of South Africa from the British Cape Colony, Colony of Natal, Orange River Colony, and Transvaal Colony. The Act also made provisions for pote ...

granted nominal independence while creating the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Trans ...

on 31 May 1910. The union was a dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

that included the former territories of the Cape, Transvaal and Natal colonies, as well as the Orange Free State republic. The Natives' Land Act

The Natives Land Act, 1913 (subsequently renamed Bantu Land Act, 1913 and Black Land Act, 1913; Act No. 27 of 1913) was an Act of the Parliament of South Africa that was aimed at regulating the acquisition of land.

According to the ''Encyclopæd ...

of 1913 severely restricted the ownership of land by blacks; at that stage they controlled only 7% of the country. The amount of land reserved for indigenous peoples was later marginally increased.

In 1931, the union became fully sovereign from the United Kingdom with the passage of the Statute of Westminster, which abolished the last powers of the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprema ...

to legislate on the country. Only three other African countries—Liberia, Ethiopia, and Egypt—had been independent prior to that point. In 1934, the South African Party and National Party merged to form the United Party, seeking reconciliation between Afrikaners and English-speaking whites. In 1939, the party split over the entry of the union into World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

as an ally of the United Kingdom, a move which the National Party followers strongly opposed.

Beginning of apartheid

In 1948, the National Party was elected to power. It strengthened the racial segregation begun under Dutch and British colonial rule. Taking Canada's

In 1948, the National Party was elected to power. It strengthened the racial segregation begun under Dutch and British colonial rule. Taking Canada's Indian Act

The ''Indian Act'' (, long name ''An Act to amend and consolidate the laws respecting Indians'') is a Canadian act of Parliament that concerns registered Indians, their bands, and the system of Indian reserves. First passed in 1876 and still ...

as a framework, the nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

government classified all peoples into three races (''Whites, Blacks, Indians and Coloured people (people of mixed race)'') and developed rights and limitations for each. The white minority (less than 20%) controlled the vastly larger black majority. The legally institutionalised segregation became known as ''apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

''. While whites enjoyed the highest standard of living

Standard of living is the level of income, comforts and services available, generally applied to a society or location, rather than to an individual. Standard of living is relevant because it is considered to contribute to an individual's quality ...

in all of Africa, comparable to First World

The concept of First World originated during the Cold War and comprised countries that were under the influence of the United States and the rest of NATO and opposed the Soviet Union and/or communism during the Cold War. Since the collapse of ...

Western nations, the black majority remained disadvantaged by almost every standard, including income, education, housing, and life expectancy. The Freedom Charter

The Freedom Charter was the statement of core principles of the South African Congress Alliance, which consisted of the African National Congress (ANC) and its allies: the South African Indian Congress, the South African Congress of Democrats ...