Sorcery (goetia) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Goetia'' () is a type of European sorcery, often referred to as

''Goetia'' () is a type of European sorcery, often referred to as

A ''grimoire'' (also known as a "book of spells", "magic book", or a "spellbook") is a

A ''grimoire'' (also known as a "book of spells", "magic book", or a "spellbook") is a

The English word magic has its origins in

The English word magic has its origins in

There is also a medieval-era Templar Magic Square in the

There is also a medieval-era Templar Magic Square in the

Godfrid Storms argued that

Godfrid Storms argued that

''Goetia'' and some (though not all) medieval grimoires became associated with demonolatry. These grimoires contain magical words of power and instructions for the

''Goetia'' and some (though not all) medieval grimoires became associated with demonolatry. These grimoires contain magical words of power and instructions for the

In

In

''Goetia'' () is a type of European sorcery, often referred to as

''Goetia'' () is a type of European sorcery, often referred to as witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have us ...

, that has been transmitted through grimoire

A grimoire ( ) (also known as a "book of spells" or a "spellbook") is a textbook of magic, typically including instructions on how to create magical objects like talismans and amulets, how to perform magical spells, charms and divination, and ...

s—books containing instructions for performing magical practices. The term "goetia" finds its origins in the Greek word "goes", which originally denoted diviners

Divination (from Latin ''divinare'', 'to foresee, to foretell, to predict, to prophesy') is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic, standardized process or ritual. Used in various forms throughout history ...

, magicians

Magician or The Magician may refer to:

Performers

* A practitioner of magic (supernatural)

* A practitioner of magic (illusion)

* Magician (fantasy), a character in a fictional fantasy context

Entertainment

Books

* ''The Magician'', an 18th-ce ...

, healers, and seer

In the United States, the efficiency of air conditioners is often rated by the seasonal energy efficiency ratio (SEER) which is defined by the Air Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute, a trade association, in its 2008 standard AHRI ...

s. Initially, it held a connotation of low magic, implying fraudulent or deceptive ''mageia'' as opposed to theurgy

Theurgy (; ) describes the practice of rituals, sometimes seen as magical in nature, performed with the intention of invoking the action or evoking the presence of one or more deities, especially with the goal of achieving henosis (uniting wi ...

, which was regarded as divine magic. Grimoires, also known as "books of spells" or "spellbooks," serve as instructional manuals for various magical endeavors. They cover crafting magical objects, casting spells, performing divination, and summoning supernatural entities like angels, spirits, deities, and demons. Although the term "grimoire" originates from Europe, similar magical texts have been found in diverse cultures across the world.

The history of grimoires can be traced back to ancient Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

, where magical incantations were inscribed on cuneiform clay tablets. Ancient Egyptians also employed magical practices, including incantations

An incantation, a spell, a charm, an enchantment or a bewitchery, is a magical formula intended to trigger a magical effect on a person or objects. The formula can be spoken, sung or chanted. An incantation can also be performed during ceremo ...

inscribed on amulets

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word amuletum, which Pliny's ''Natural History'' describes as "an object that protects ...

. The magical system of ancient Egypt, deified in the form of the god Heka Heka may refer to:

* Heka (god), the deification of magic in Egyptian mythology

* Lambda Orionis, a star in the constellation of Orion, also known by the traditional names "Meissa" and "Heka"

* Phenom II

Phenom II is a family of AMD's multi-core ...

, underwent changes after the Macedonian invasion led by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

. The rise of the Coptic

Coptic may refer to:

Afro-Asia

* Copts, an ethnoreligious group mainly in the area of modern Egypt but also in Sudan and Libya

* Coptic language, a Northern Afro-Asiatic language spoken in Egypt until at least the 17th century

* Coptic alphabet ...

writing system and the Library of Alexandria

The Great Library of Alexandria in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. The Library was part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, which was dedicated to the Muses, th ...

further influenced the development of magical texts, which evolved from simple charms to encompass various aspects of life, including financial success and fulfillment. Legendary figures like Hermes Trismegistus

Hermes Trismegistus (from grc, Wiktionary:Ἑρμῆς, Ἑρμῆς ὁ Τρισμέγιστος, "Hermes the Thrice-Greatest"; Classical Latin: la, label=none, Mercurius ter Maximus) is a legendary Hellenistic figure that originated as a Syn ...

emerged, associated with writing and magic, contributing to the creation of magical books.

Throughout history, various cultures have contributed to magical practices. Early Christianity saw the use of grimoires by certain Gnostic

Gnosticism (from grc, γνωστικός, gnōstikós, , 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems which coalesced in the late 1st century AD among Jewish and early Christian sects. These various groups emphasized pe ...

sects, with texts like the Book of Enoch containing astrological and angelic information. King Solomon

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

of Israel was linked with magic and sorcery, attributed to a book with incantations for summoning demons. The pseudepigraphic Testament of Solomon

The Testament of Solomon is a pseudepigraphical composite text ascribed to King Solomon but not regarded as canonical scripture by Jews or Christian groups. It was written in the Greek language, based on precedents dating back to the early 1st mil ...

, one of the oldest magical texts, narrates Solomon's use of a magical ring to command demons. With the ascent of Christianity, books on magic were frowned upon, and the spread of magical practices was often associated with paganism

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christianity, early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions ot ...

. This sentiment led to book burnings and the association of magical practitioners with heresy and witchcraft.

The magical revival of Goetia gained momentum in the 19th century, spearheaded by figures like Eliphas Levi Eliphaz is one of Esau's sons in the Bible.

Eliphaz or Eliphas is also the given name of:

* Eliphaz (Job), another person in the Bible

* Eliphaz Dow (1705-1755), the first male executed in New Hampshire, for murder

* Eliphaz Fay (1797–1854), f ...

and Aleister Crowley

Aleister Crowley (; born Edward Alexander Crowley; 12 October 1875 – 1 December 1947) was an English occultist, ceremonial magician, poet, painter, novelist, and mountaineer. He founded the religion of Thelema, identifying himself as the pro ...

. They interpreted and popularized magical traditions, incorporating elements from Kabbalah

Kabbalah ( he, קַבָּלָה ''Qabbālā'', literally "reception, tradition") is an esoteric method, discipline and Jewish theology, school of thought in Jewish mysticism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ( ''Məqūbbāl'' "rece ...

, Hermeticism

Hermeticism, or Hermetism, is a philosophical system that is primarily based on the purported teachings of Hermes Trismegistus (a legendary Hellenistic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth). These teachings are containe ...

, and ceremonial magic

Ceremonial magic (ritual magic, high magic or learned magic) encompasses a wide variety of rituals of magic. The works included are characterized by ceremony and numerous requisite accessories to aid the practitioner. It can be seen as an ex ...

. Levi emphasized personal transformation and ethical implications, while Crowley's works were written in support of his new religious movement

A new religious movement (NRM), also known as alternative spirituality or a new religion, is a religious or spiritual group that has modern origins and is peripheral to its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in origin or th ...

, Thelema

Thelema () is a Western esoteric and occult social or spiritual philosophy and new religious movement founded in the early 1900s by Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), an English writer, mystic, occultist, and ceremonial magician. The word '' ...

. Contemporary practitioners of occultism

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism an ...

and esotericism

Western esotericism, also known as esotericism, esoterism, and sometimes the Western mystery tradition, is a term scholars use to categorise a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas a ...

continue to engage with Goetia, drawing from historical texts while adapting rituals to align with personal beliefs. Ethical debates surround Goetia, with some approaching it cautiously due to the potential risks of interacting with powerful entities. Others view it as a means of inner transformation and self-empowerment.

History of grimoires

A ''grimoire'' (also known as a "book of spells", "magic book", or a "spellbook") is a

A ''grimoire'' (also known as a "book of spells", "magic book", or a "spellbook") is a textbook

A textbook is a book containing a comprehensive compilation of content in a branch of study with the intention of explaining it. Textbooks are produced to meet the needs of educators, usually at educational institutions. Schoolbooks are textboo ...

of magic

Magic or Magick most commonly refers to:

* Magic (supernatural), beliefs and actions employed to influence supernatural beings and forces

* Ceremonial magic, encompasses a wide variety of rituals of magic

* Magical thinking, the belief that unrela ...

, typically including instructions on how to create magical objects like talisman

A talisman is any object ascribed with religious or magical powers intended to protect, heal, or harm individuals for whom they are made. Talismans are often portable objects carried on someone in a variety of ways, but can also be installed perm ...

s and amulet

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word amuletum, which Pliny's ''Natural History'' describes as "an object that protects ...

s, how to perform magical spells, charms, and divination

Divination (from Latin ''divinare'', 'to foresee, to foretell, to predict, to prophesy') is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic, standardized process or ritual. Used in various forms throughout histor ...

, and how to summon

Evocation is the act of evoking, calling upon, or summoning a spirit, demon, deity or other supernatural agents, in the Western mystery tradition. Comparable practices exist in many religions and magical traditions and may employ the use of m ...

or invoke supernatural entities such as angel

In various theistic religious traditions an angel is a supernatural spiritual being who serves God.

Abrahamic religions often depict angels as benevolent celestial intermediaries between God (or Heaven) and humanity. Other roles include ...

s, spirits

Spirit or spirits may refer to:

Liquor and other volatile liquids

* Spirits, a.k.a. liquor, distilled alcoholic drinks

* Spirit or tincture, an extract of plant or animal material dissolved in ethanol

* Volatile (especially flammable) liquids, ...

, deities

A deity or god is a supernatural being who is considered divine or sacred. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines deity as a god or goddess, or anything revered as divine. C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greate ...

, and demon

A demon is a malevolent supernatural entity. Historically, belief in demons, or stories about demons, occurs in religion, occultism, literature, fiction, mythology, and folklore; as well as in media such as comics, video games, movies, ani ...

s. While the term ''grimoire'' is originally European—and many Europeans throughout history, particularly ceremonial magic

Ceremonial magic (ritual magic, high magic or learned magic) encompasses a wide variety of rituals of magic. The works included are characterized by ceremony and numerous requisite accessories to aid the practitioner. It can be seen as an ex ...

ians and cunning folk

Cunning folk, also known as folk healers or wise folk, were practitioners of folk medicine, helpful folk magic and divination in Europe from the Middle Ages until the 20th century. Their practices were known as the cunning craft. Their services a ...

, have used grimoires—the historian Owen Davies has noted that similar books can be found all around the world, ranging from Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

to Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

. He also noted that in this sense, the world's first grimoires were created in Europe and the ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran ( Elam, ...

.

The earliest known written magical incantations come from ancient Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

(modern Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

), where they have been found inscribed on cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge-sha ...

clay tablets that archaeologists

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

excavated from the city of Uruk

Uruk, also known as Warka or Warkah, was an ancient city of Sumer (and later of Babylonia) situated east of the present bed of the Euphrates River on the dried-up ancient channel of the Euphrates east of modern Samawah, Al-Muthannā, Iraq.Harm ...

and dated to between the 5th and 4th centuries BC. The ancient Egyptians also employed magical incantations, which have been found inscribed on amulets and other items. The Egyptian magical system, known as heka Heka may refer to:

* Heka (god), the deification of magic in Egyptian mythology

* Lambda Orionis, a star in the constellation of Orion, also known by the traditional names "Meissa" and "Heka"

* Phenom II

Phenom II is a family of AMD's multi-core ...

, was greatly altered and expanded after the Macedonians, led by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

, invaded Egypt in 332 BC.

Under the next three centuries of Hellenistic Egypt, the Coptic

Coptic may refer to:

Afro-Asia

* Copts, an ethnoreligious group mainly in the area of modern Egypt but also in Sudan and Libya

* Coptic language, a Northern Afro-Asiatic language spoken in Egypt until at least the 17th century

* Coptic alphabet ...

writing system evolved, and the Library of Alexandria

The Great Library of Alexandria in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. The Library was part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, which was dedicated to the Muses, th ...

was opened. This likely had an influence upon books of magic, with the trend on known incantations switching from simple health and protection charms to more specific things, such as financial success and sexual fulfillment. Around this time the legendary figure of Hermes Trismegistus

Hermes Trismegistus (from grc, Wiktionary:Ἑρμῆς, Ἑρμῆς ὁ Τρισμέγιστος, "Hermes the Thrice-Greatest"; Classical Latin: la, label=none, Mercurius ter Maximus) is a legendary Hellenistic figure that originated as a Syn ...

developed as a conflation of the Egyptian god Thoth

Thoth (; from grc-koi, Θώθ ''Thṓth'', borrowed from cop, Ⲑⲱⲟⲩⲧ ''Thōout'', Egyptian: ', the reflex of " eis like the Ibis") is an ancient Egyptian deity. In art, he was often depicted as a man with the head of an ibis or a ...

and the Greek Hermes

Hermes (; grc-gre, Ἑρμῆς) is an Olympian deity in ancient Greek religion and mythology. Hermes is considered the herald of the gods. He is also considered the protector of human heralds, travellers, thieves, merchants, and orato ...

; this figure was associated with writing and magic and, therefore, of books on magic.

The ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cultu ...

and Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

believed that books on magic were invented by the Persians

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian.

...

. The 1st-century AD writer Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

stated that magic had been first discovered by the ancient philosopher Zoroaster

Zoroaster,; fa, زرتشت, Zartosht, label=New Persian, Modern Persian; ku, زەردەشت, Zerdeşt also known as Zarathustra,, . Also known as Zarathushtra Spitama, or Ashu Zarathushtra is regarded as the spiritual founder of Zoroastria ...

around the year 647 BC but that it was only written down in the 5th century BC by the magician Osthanes

Ostanes (from Ancient Greek, Greek ), also spelled Hostanes and Osthanes, is a legendary Persians, Persian magus and alchemist. It was the pen-name used by several pseudepigraphy, pseudo-anonymous authors of Greek and Latin works from Hellenistic ...

. His claims are not, however, supported by modern historians. The Greek Magical Papyri

The Greek Magical Papyri (Latin: ''Papyri Graecae Magicae'', abbreviated ''PGM'') is the name given by scholars to a body of papyri from Graeco-Roman Egypt, written mostly in ancient Greek (but also in Old Coptic, Demotic, etc.), which each cont ...

, nearly a millennium after the fall of Mesopotamia, preserve the name of the Sumerian goddess Ereshkigal

In Mesopotamian mythology, Ereshkigal ( sux, , lit. "Queen of the Great Earth") was the goddess of Kur, the land of the dead or underworld in Sumerian religion, Sumerian mythology. In later myths, she was said to rule Irkalla alongside her husb ...

.

The ancient Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

people were often viewed as being knowledgeable in magic, which, according to legend, they had learned from Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu (Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pro ...

, who had learned it in Egypt. Among many ancient writers, Moses was seen as an Egyptian rather than a Jew. Two manuscripts likely dating to the 4th century, both of which purport to be the legendary eighth Book of Moses (the first five being the initial books in the Biblical Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

), present him as a polytheist

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, the b ...

who explained how to conjure gods and subdue demons.

Meanwhile, there is definite evidence of grimoires being used by certain—particularly Gnostic

Gnosticism (from grc, γνωστικός, gnōstikós, , 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems which coalesced in the late 1st century AD among Jewish and early Christian sects. These various groups emphasized pe ...

—sects of early Christianity

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish ...

. In the '' Book of Enoch'' found within the Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls (also the Qumran Caves Scrolls) are ancient Jewish and Hebrew religious manuscripts discovered between 1946 and 1956 at the Qumran Caves in what was then Mandatory Palestine, near Ein Feshkha in the West Bank, on the nor ...

, for instance, there is information on astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of Celestial o ...

and the angels. In possible connection with the ''Book of Enoch'', the idea of Enoch

Enoch () ''Henṓkh''; ar, أَخْنُوخ ', Qur'ān.html"_;"title="ommonly_in_Qur'ān">ommonly_in_Qur'ānic_literature__'_is_a_biblical_figure_and_Patriarchs_(Bible).html" "title="Qur'ānic_literature.html" ;"title="Qur'ān.html" ;"title="o ...

and his great-grandson Noah

Noah ''Nukh''; am, ኖህ, ''Noḥ''; ar, نُوح '; grc, Νῶε ''Nôe'' () is the tenth and last of the pre-Flood patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5– ...

having some involvement with books of magic given to them by angels continued through to the medieval period.

Israelite King Solomon

Solomon (; , ),, ; ar, سُلَيْمَان, ', , ; el, Σολομών, ; la, Salomon also called Jedidiah (Hebrew language, Hebrew: , Modern Hebrew, Modern: , Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yăḏīḏăyāh'', "beloved of Yahweh, Yah"), ...

was a Biblical figure associated with magic and sorcery in the ancient world. The 1st-century Romano-Jewish historian Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for ''The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly d ...

mentioned a book circulating under the name of Solomon that contained incantations for summoning demons and described how a Jew called Eleazar used it to cure cases of possession.

The pseudepigraphic

Pseudepigrapha (also anglicized as "pseudepigraph" or "pseudepigraphs") are falsely attributed works, texts whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past.Bauckham, Richard; "Pseu ...

''Testament of Solomon

The Testament of Solomon is a pseudepigraphical composite text ascribed to King Solomon but not regarded as canonical scripture by Jews or Christian groups. It was written in the Greek language, based on precedents dating back to the early 1st mil ...

'' is one of the oldest magical texts. It is a Greek manuscript attributed to Solomon and was likely written in either Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c. ...

or Egypt sometime in the first five centuries AD; over 1,000 years after Solomon's death. The work tells of the building of The Temple and relates that construction was hampered by demons until the archangel

Archangels () are the second lowest rank of angel in the hierarchy of angels. The word ''archangel'' itself is usually associated with the Abrahamic religions, but beings that are very similar to archangels are found in a number of other relig ...

Michael

Michael may refer to:

People

* Michael (given name), a given name

* Michael (surname), including a list of people with the surname Michael

Given name "Michael"

* Michael (archangel), ''first'' of God's archangels in the Jewish, Christian an ...

gave the King a magical ring. The ring, engraved with the Seal of Solomon

The Seal of Solomon or Ring of Solomon ( he, חותם שלמה, '; ar, خاتم سليمان, ') is the legendary signet ring attributed to the Israelite king Solomon in medieval mystical traditions, from which it developed in parallel within ...

, had the power to bind demons from doing harm. Solomon used it to lock demons in jars and commanded others to do his bidding, although eventually, according to the ''Testament'', he was tempted into worshiping the gods Moloch

Moloch (; ''Mōleḵ'' or הַמֹּלֶךְ ''hamMōleḵ''; grc, Μόλοχ, la, Moloch; also Molech or Molek) is a name or a term which appears in the Hebrew Bible several times, primarily in the book of Leviticus. The Bible strongly co ...

and Ashtoreth

Astarte (; , ) is the Hellenized form of the Ancient Near Eastern goddess Ashtart or Athtart (Northwest Semitic), a deity closely related to Ishtar (East Semitic), who was worshipped from the Bronze Age through classical antiquity. The name i ...

. Subsequently, after losing favour with the god of Israel, King Solomon wrote the work as a warning and a guide to the reader.

When Christianity became the dominant faith of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

, the early Church frowned upon the propagation of books on magic, connecting it with paganism

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christianity, early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions ot ...

, and burned books of magic. The New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

records that after the unsuccessful exorcism

Exorcism () is the religious or spiritual practice of evicting demons, jinns, or other malevolent spiritual entities from a person, or an area, that is believed to be possessed. Depending on the spiritual beliefs of the exorcist, this may be ...

by the seven sons of Sceva became known, many converts decided to burn their own magic and pagan books in the city of Ephesus

Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἔφεσος, Éphesos; tr, Efes; may ultimately derive from hit, 𒀀𒉺𒊭, Apaša) was a city in ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in t ...

; this advice was adopted on a large scale after the Christian ascent to power.

Magic and ''goetia'' in the Greco-Roman world

Greece

The English word magic has its origins in

The English word magic has its origins in ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

.

During the late sixth and early fifth centuries BCE, the Persian ''maguš'' was Graecicized and introduced into the ancient Greek language as ''μάγος'' and ''μαγεία''. In doing so it transformed meaning, gaining negative connotations, with the ''magos'' being regarded as a charlatan whose ritual practices were fraudulent, strange, unconventional, and dangerous. As noted by Davies, for the ancient Greeks—and subsequently for the ancient Romans—"magic was not distinct from religion but rather an unwelcome, improper expression of it—the religion of the other". The historian Richard Gordon suggested that for the ancient Greeks, being accused of practicing magic was "a form of insult".

Magical operations largely fell into two categories: theurgy

Theurgy (; ) describes the practice of rituals, sometimes seen as magical in nature, performed with the intention of invoking the action or evoking the presence of one or more deities, especially with the goal of achieving henosis (uniting wi ...

() defined as high magic, and ''goetia'' () as low magic or witchcraft. Theurgy in some contexts appears simply to glorify the kind of magic that is being practiced – usually a respectable priest-like figure is associated with the ritual. ''Goetia'' was a derogatory term connoting low, specious or fraudulent ''mageia''.

'' Katadesmoi'' (Latin: '' defixiones)'', curses inscribed on wax or lead tablets and buried underground, were frequently executed by all strata of Greek society, sometimes to protect the entire ''polis''. Communal curses carried out in public declined after the Greek classical period, but private curses remained common throughout antiquity. They were distinguished as magical by their individualistic, instrumental and sinister qualities. These qualities, and their perceived deviation from inherently mutable cultural constructs of normality, most clearly delineate ancient magic from the religious rituals of which they form a part.

A large number of magical papyri

The Greek Magical Papyri (Latin: ''Papyri Graecae Magicae'', abbreviated ''PGM'') is the name given by scholars to a body of papyri from Graeco-Roman Egypt, written mostly in ancient Greek (but also in Old Coptic, Demotic, etc.), which each con ...

, in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, Coptic

Coptic may refer to:

Afro-Asia

* Copts, an ethnoreligious group mainly in the area of modern Egypt but also in Sudan and Libya

* Coptic language, a Northern Afro-Asiatic language spoken in Egypt until at least the 17th century

* Coptic alphabet ...

, and Demotic

Demotic may refer to:

* Demotic Greek, the modern vernacular form of the Greek language

* Demotic (Egyptian), an ancient Egyptian script and version of the language

* Chữ Nôm, the demotic script for writing Vietnamese

See also

*

* Demos (disa ...

, have been recovered and translated. They contain early instances of:

* the use of magic word

Magic words are often nonsense phrases used in fantasy fiction or by stage magicians. Frequently such words are presented as being part of a divine, adamic, or other secret or empowered language. Certain comic book heroes use magic words to activ ...

s said to have the power to command spirits;

* the use of mysterious symbol

A symbol is a mark, sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, object, or relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by creating linkages between otherwise very different conc ...

s or sigil

A sigil () is a type of symbol used in magic. The term has usually referred to a pictorial signature of a deity or spirit. In modern usage, especially in the context of chaos magic, sigil refers to a symbolic representation of the practitioner ...

s which are thought to be useful when invoking or evoking spirits.

In the first century BCE, the Greek concept of the ''magos'' was adopted into Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and used by a number of ancient Roman

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC ...

writers as ''magus'' and ''magia''. The earliest known Latin use of the term was in Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

's ''Eclogue

An eclogue is a poem in a classical style on a pastoral subject. Poems in the genre are sometimes also called bucolics.

Overview

The form of the word ''eclogue'' in contemporary English developed from Middle English , which came from Latin , whi ...

'', written around 40 BCE, which makes reference to ''magicis... sacris'' (magic rites). The Romans already had other terms for the negative use of supernatural powers, such as ''veneficus'' and ''saga''. The Roman use of the term was similar to that of the Greeks, but placed greater emphasis on the judicial application of it.

Roman Empire

In ancient Roman society, magic was associated with societies to the east of the empire; the first century CE writerPliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

for instance claimed that magic had been created by the Iranian philosopher Zoroaster

Zoroaster,; fa, زرتشت, Zartosht, label=New Persian, Modern Persian; ku, زەردەشت, Zerdeşt also known as Zarathustra,, . Also known as Zarathushtra Spitama, or Ashu Zarathushtra is regarded as the spiritual founder of Zoroastria ...

, and that it had then been brought west into Greece by the magician Osthanes

Ostanes (from Ancient Greek, Greek ), also spelled Hostanes and Osthanes, is a legendary Persians, Persian magus and alchemist. It was the pen-name used by several pseudepigraphy, pseudo-anonymous authors of Greek and Latin works from Hellenistic ...

, who accompanied the military campaigns of the Persian King Xerxes.

Within the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

, laws would be introduced criminalising things regarded as magic. The practice of magic was banned in the late Roman world, and the ''Codex Theodosianus

The ''Codex Theodosianus'' (Eng. Theodosian Code) was a compilation of the laws of the Roman Empire under the Christian emperors since 312. A commission was established by Emperor Theodosius II and his co-emperor Valentinian III on 26 March 429 a ...

'' (438 AD) states:

If any wizard therefore or person imbued with magical contamination who is called by custom of the people a magician ..should be apprehended in my retinue, or in that of the Caesar, he shall not escape punishment and torture by the protection of his rank.

''Defixiones'' and sorcery in Roman Britain

Christopher A. Faraone

Christopher is the English version of a Europe-wide name derived from the Greek name Χριστόφορος (''Christophoros'' or '' Christoforos''). The constituent parts are Χριστός (''Christós''), "Christ" or "Anointed", and φέρει� ...

writes that "In Late Antiquity we can see that a goddess invoked as Hecate Ereshkigal was useful in both protective magic and in curses. ..she also appears on a number of curse tablets .. Robin Melrose writes that "the first clear-cut magic in Britain was the use of curse tablet

A curse tablet ( la, tabella defixionis, defixio; el, κατάδεσμος, katadesmos) is a small tablet with a curse written on it from the Greco-Roman world. Its name originated from the Greek and Latin words for "pierce" and "bind". The table ...

s, which came with the Romans.

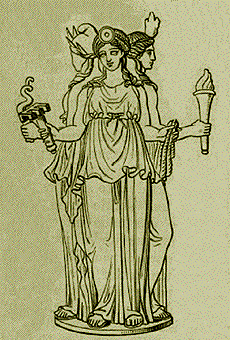

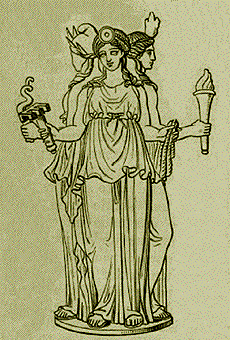

Potter and Johns wrote that "Some classical deities, notably Hecate

Hecate or Hekate, , ; grc-dor, Ἑκάτᾱ, Hekátā, ; la, Hecatē or . is a goddess in ancient Greek religion and mythology, most often shown holding a pair of torches, a key, snakes, or accompanied by dogs, and in later periods depicte ...

of the underworld

The underworld, also known as the netherworld or hell, is the supernatural world of the dead in various religious traditions and myths, located below the world of the living. Chthonic is the technical adjective for things of the underworld.

...

, had triple manifestations. In Roman Britain, some fifty dedications to the Mothers are recorded in stone inscriptions and other objects, constituting ample evidence of the importance of the cult among native Celts and others."

In 1979–80, the Bath curse tablets

The Bath curse tablets are a collection of about 130 Roman era curse tablets (or ''defixiones'' in Latin) discovered in 1979/1980 in the English city of Bath. The tablets were requests for intervention of the goddess Sulis Minerva in the retu ...

were found at the site of ''Aquae Sulis

Aquae Sulis (Latin for ''Waters of Sulis'') was a small town in the Roman province of Britannia. Today it is the English city of Bath, Somerset. The Antonine Itinerary register of Roman roads lists the town as ''Aquis Sulis.'' Ptolemy records ...

'' (now Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

in England). All but one of the 130 tablets concerned the restitution of stolen goods. Over 80 similar tablets have been discovered in and about the remains of a temple to Mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

nearby, at West Hill, Uley

Uley is a village and civil parish in the county of Gloucestershire, England. The parish includes the hamlets of Elcombe and Shadwell and Bencombe, all to the south of the village of Uley, and the hamlet of Crawley to the north. The village is ...

, making south-western Britain one of the major centres for finds of Latin ''defixiones''.

Most of the inscriptions are in colloquial Latin, and specifically in the Vulgar Latin

Vulgar Latin, also known as Popular or Colloquial Latin, is the range of non-formal Register (sociolinguistics), registers of Latin spoken from the Crisis of the Roman Republic, Late Roman Republic onward. Through time, Vulgar Latin would evolve ...

of the Romano-British

The Romano-British culture arose in Britain under the Roman Empire following the Roman conquest in AD 43 and the creation of the province of Britannia. It arose as a fusion of the imported Roman culture with that of the indigenous Britons, a ...

population, known as "British Latin

British Latin or British Vulgar Latin was the Vulgar Latin spoken in Great Britain in the Roman and sub-Roman periods. While Britain formed part of the Roman Empire, Latin became the principal language of the elite, especially in the more roma ...

". Two of the inscriptions are in a language which is not Latin, although they use Roman lettering, and may be in a British Celtic language

The Celtic languages ( usually , but sometimes ) are a group of related languages descended from Proto-Celtic. They form a branch of the Indo-European language family. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward ...

. If this should be the case, they would be the only examples of a written ancient British Celtic language; however, there is not yet scholarly consensus on their decipherment.

There is also a medieval-era Templar Magic Square in the

There is also a medieval-era Templar Magic Square in the Rivington Church

Rivington Church is an active Anglican parish church in Rivington, Lancashire, England. It is in the Deane deanery, the Bolton archdeanery and Diocese of Manchester. The church has been designated a Grade II listed building. The church has no p ...

in Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

, England. Scholars have found medieval Sator-based charms, remedies, and cures, for a diverse range of applications from childbirth, to toothaches, to love potions, to ways of warding off evil spells, and even to determine whether someone was a witch. Richard Cavendish notes a medieval manuscript in the Bodleian

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford, and is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. It derives its name from its founder, Sir Thomas Bodley. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second- ...

says: "Write these ive satorwords on in parchment with the blood of a Culver igeonand bear it in thy left hand and ask what thou wilt and thou shalt have it. fiat."

In medieval times, the Roman temple at Bath would be incorporated into the Matter of Britain

The Matter of Britain is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the list of legendary kings of Britain, legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. It ...

. The thermal springs at Bath were said to have been dedicated to Minerva by the legendary King Bladud

Bladud or Blaiddyd is a legendary king of the Britons, although there is no historical evidence for his existence. He is first mentioned in Geoffrey of Monmouth's ''Historia Regum Britanniae'' ( 1136), which describes him as the son of King Rud ...

and the temple there endowed with an eternal flame.

In Medieval Europe

Role of the Matter of Britain in the condemnation of ''goetia''

Godfrid Storms argued that

Godfrid Storms argued that animism

Animism (from Latin: ' meaning 'breath, Soul, spirit, life') is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct Spirituality, spiritual essence. Potentially, animism perceives all things—Animal, animals, Plant, plants, Ro ...

played a significant role in the worldview of Anglo-Saxon magic, noting that in the recorded charms, "All sorts of phenomenon are ascribed to the visible or invisible intervention of good or evil spirits." The primary creature of the spirit world that appear in the Anglo-Saxon charms is the ''ælf'' (nominative plural ''ylfe'', "elf

An elf () is a type of humanoid supernatural being in Germanic mythology and folklore. Elves appear especially in North Germanic mythology. They are subsequently mentioned in Snorri Sturluson's Icelandic Prose Edda. He distinguishes "ligh ...

"), an entity who was believed to cause sickness in humans. Another type of spirit creature, a demonic one, believed to cause physical harm in the Anglo-Saxon world was the ''dweorg'' or ''dƿeorg''/''dwerg'' ("dwarf

Dwarf or dwarves may refer to:

Common uses

*Dwarf (folklore), a being from Germanic mythology and folklore

* Dwarf, a person or animal with dwarfism

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional entities

* Dwarf (''Dungeons & Dragons''), a humanoid ...

"), whom Storms characterised as a "disease-spirit". A number of charms imply the belief that malevolent "disease-spirits" were causing sickness by inhabiting a person's blood. Such charms offer remedies to remove these spirits, calling for blood to be drawn out to drive the disease-spirit out with it.

The adoption of Christianity saw some of these pre-Christian mythological creatures reinterpreted as devil

A devil is the personification of evil as it is conceived in various cultures and religious traditions. It is seen as the objectification of a hostile and destructive force. Jeffrey Burton Russell states that the different conceptions of t ...

s, who are also referenced in the surviving charms. In late Anglo-Saxon England, nigromancy

Black magic, also known as dark magic, has traditionally referred to the use of supernatural powers or magic for evil and selfish purposes, specifically the seven magical arts prohibited by canon law, as expounded by Johannes Hartlieb in 1456 ...

('black magic', sometimes confused with necromancy

Necromancy () is the practice of magic or black magic involving communication with the dead by summoning their spirits as apparitions or visions, or by resurrection for the purpose of divination; imparting the means to foretell future events; ...

) was among the witchcraft practices condemned by Ælfric of Eynsham

Ælfric of Eynsham ( ang, Ælfrīc; la, Alfricus, Elphricus; ) was an English abbot and a student of Æthelwold of Winchester, and a consummate, prolific writer in Old English of hagiography, homilies, biblical commentaries, and other genres. H ...

(c. 955 – c. 1010):

Witches still go to cross-roads and to heathen burials with their delusive magic and call to the devil; and he comes to them in the likeness of the man that is buried there, as if he arises from death.

Gregory of Nyssa

Gregory of Nyssa, also known as Gregory Nyssen ( grc-gre, Γρηγόριος Νύσσης; c. 335 – c. 395), was Bishop of Nyssa in Cappadocia from 372 to 376 and from 378 until his death in 395. He is venerated as a saint in Catholici ...

(c. 335 – c. 395) had said that demon

A demon is a malevolent supernatural entity. Historically, belief in demons, or stories about demons, occurs in religion, occultism, literature, fiction, mythology, and folklore; as well as in media such as comics, video games, movies, ani ...

s had children with women called cambion

In European mythology and literature since at least the 19th century, a cambion is the offspring of an incubus, succubus, or other demon with a human. In its earliest known uses, it was related to the word for change and was cognate with changelin ...

s, which added to the children they had between them, contributed to increase the number of demons. However, the first popular account of such a union and offspring does not occur in Western literature until around 1136, when Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth ( la, Galfridus Monemutensis, Galfridus Arturus, cy, Gruffudd ap Arthur, Sieffre o Fynwy; 1095 – 1155) was a British cleric from Monmouth, Wales and one of the major figures in the development of British historiograph ...

wrote the story of Merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and le ...

in his pseudohistorical account of British history, ''Historia Regum Britanniae

''Historia regum Britanniae'' (''The History of the Kings of Britain''), originally called ''De gestis Britonum'' (''On the Deeds of the Britons''), is a pseudohistorical account of British history, written around 1136 by Geoffrey of Monmouth. I ...

'' ''(History of the Kings of Britain)'', in which he reported that Merlin's father was an incubus

An incubus is a demon in male form in folklore that seeks to have sexual intercourse with sleeping women; the corresponding spirit in female form is called a succubus. In medieval Europe, union with an incubus was supposed by some to result in t ...

..

Anne Lawrence-Mathers writes that at that time "... views on demons and spirits were still relatively flexible. There was still a possibility that the ''daemon

Daimon or Daemon (Ancient Greek: , "god", "godlike", "power", "fate") originally referred to a lesser deity or guiding spirit such as the daimons of ancient Greek religion and mythology and of later Hellenistic religion and philosophy.

The word ...

s'' of classical tradition were different from the demons of the Bible." Accounts of sexual relations with demons in literature continues with ''The Life of Saint Bernard

Bernard (''Bernhard'') is a French and West Germanic masculine given name. It is also a surname.

The name is attested from at least the 9th century. West Germanic ''Bernhard'' is composed from the two elements ''bern'' "bear" and ''hard'' "brav ...

'' by Geoffrey of Auxerre Geoffrey of Clairvaux, or Geoffrey of Auxerre, was the secretary and biographer of Bernard of Clairvaux and later abbot of a number of monasteries in the Cistercian tradition.

Life

He was born between the years 1115 and 1120, at Auxerre. At an ea ...

( 1160) and the ''Life and Miracles of St. William of Norwich

William of Norwich (2 February 1132 – 22 March 1144) was an English boy whose disappearance and killing was, at the time, attributed to the Jewish community of Norwich. It is the first known medieval accusation against Jews of ritual murder. ...

'' by Thomas of Monmouth

Thomas of Monmouth ( fl. 1149–1172) was a Benedictine monk who lived in the Priory at Norwich Cathedral, England during the mid-twelfth century. He was the author of ''The Life and Miracles of St William of Norwich'', a hagiography of William of ...

( 1173). The theme of sexual relations with demons became a matter of increasing interest for late 12th-century writers.

''Prophetiae Merlini

The ''Prophetiæ Merlini'' is a Latin work of Geoffrey of Monmouth circulated, perhaps as a ''libellus'' or short work, from about 1130, and by 1135. Another name is ''Libellus Merlini''.

The work contains a number of prophecies attributed to ...

'' (''The Prophecies of Merlin''), a Latin work of Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth ( la, Galfridus Monemutensis, Galfridus Arturus, cy, Gruffudd ap Arthur, Sieffre o Fynwy; 1095 – 1155) was a British cleric from Monmouth, Wales and one of the major figures in the development of British historiograph ...

in circulation by 1135, perhaps as a ''libellus'' or short work, was the first work about the prophet Myrddin

Myrddin Wyllt (—"Myrddin the Wild", kw, Marzhin Gwyls, br, Merzhin Gueld) is a figure in medieval Welsh legend. In Middle Welsh poetry he is accounted a chief bard, the speaker of several poems in The Black Book of Carmarthen and The Red Bo ...

in a language other than Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

. The ''Prophetiae'' was widely read — and believed — throughout Europe, much as the prophecies of Nostradamus

Michel de Nostredame (December 1503 – July 1566), usually Latinised as Nostradamus, was a French astrologer, apothecary, physician, and reputed seer, who is best known for his book ''Les Prophéties'' (published in 1555), a collection o ...

would be centuries later; John Jay Parry and Robert Caldwell note that the ''Prophetiae Merlini'' "were taken most seriously, even by the learned and worldly wise, in many nations", and list examples of this credulity as late as 1445.

It was only beginning in the 1150s that the Church turned its attention to defining the possible roles of spirits and demons, especially with respect to their sexuality and in connection with the various forms of magic

Magic or Magick most commonly refers to:

* Magic (supernatural), beliefs and actions employed to influence supernatural beings and forces

* Ceremonial magic, encompasses a wide variety of rituals of magic

* Magical thinking, the belief that unrela ...

which were then believed to exist. Christian demonologists eventually came to agree that sexual relationships between demons and humans happen, but they disagreed on why and how. A common point of view is that demons induce men and women to the sin

In a religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, s ...

of lust

Lust is a psychological force producing intense desire for something, or circumstance while already having a significant amount of the desired object. Lust can take any form such as the lust for sexuality (see libido), money, or power. It can ...

, and adultery

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal ...

is often considered as an associated sin.

''Goetia'' viewed as ''maleficium'', sorcery and witchcraft

''Goetia'' and some (though not all) medieval grimoires became associated with demonolatry. These grimoires contain magical words of power and instructions for the

''Goetia'' and some (though not all) medieval grimoires became associated with demonolatry. These grimoires contain magical words of power and instructions for the evocation

Evocation is the act of evoking, calling upon, or summoning a spirit, demon, deity or other supernatural agents, in the Western mystery tradition. Comparable practices exist in many religions and magical traditions and may employ the use of mi ...

of spirits

Spirit or spirits may refer to:

Liquor and other volatile liquids

* Spirits, a.k.a. liquor, distilled alcoholic drinks

* Spirit or tincture, an extract of plant or animal material dissolved in ethanol

* Volatile (especially flammable) liquids, ...

derived from older pagan traditions. Sources include Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

n, Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

, Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

n, Greek, Celtic, and Anglo-Saxon paganism and include demons or devils mentioned in the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

, such as Asmodeus

Asmodeus (; grc, Ἀσμοδαῖος, ''Asmodaios'') or Ashmedai (; he, אַשְמְדּאָי, ''ʾAšmədʾāy''; see below for other variations), is a ''prince of demons'' and hell."Asmodeus" in ''The New Encyclopædia Britannica''. Chica ...

, Astaroth

Astaroth (also Ashtaroth, Astarot and Asteroth), in demonology, was known to be the Great Duke of Hell in the first hierarchy with Beelzebub and Lucifer; he was part of the evil trinity. He is known to be a male figure most likely named afte ...

, and Beelzebub

Beelzebub ( ; he, ''Baʿal-zəḇūḇ'') or Beelzebul is a name derived from a Philistine god, formerly worshipped in Ekron, and later adopted by some Abrahamic religions as a major demon. The name ''Beelzebub'' is associated with the Cana ...

.

During the 14th century, sorcerers were feared and respected throughout many societies and used many practices to achieve their goals. "Witches or sorcerers were usually feared as well as respected, and they used a variety of means to attempt to achieve their goals, including incantations (formulas or chants invoking evil spirits), divination

Divination (from Latin ''divinare'', 'to foresee, to foretell, to predict, to prophesy') is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic, standardized process or ritual. Used in various forms throughout histor ...

and oracle

An oracle is a person or agency considered to provide wise and insightful counsel or prophetic predictions, most notably including precognition of the future, inspired by deities. As such, it is a form of divination.

Description

The word '' ...

s (to predict the future), amulet

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word amuletum, which Pliny's ''Natural History'' describes as "an object that protects ...

s and charms

Charm may refer to:

Social science

* Charisma, a person or thing's pronounced ability to attract others

* Superficial charm, flattery, telling people what they want to hear

Science and technology

* Charm quark, a type of elementary particle

* Cha ...

(to ward off hostile spirits and harmful events), potion

A potion () is a liquid "that contains medicine, poison, or something that is supposed to have magic powers.” It derives from the Latin word ''potus'' which referred to a drink or drinking. The term philtre is also used, often specifically ...

s or salves, and dolls

A doll is a model typically of a human or humanoid character, often used as a toy for children. Dolls have also been used in traditional religious rituals throughout the world. Traditional dolls made of materials such as clay and wood are found ...

or other figures (to represent their enemies)".

Medieval Europe saw the Latin legal term ''maleficium'' applied to forms of ''sorcery'' or ''witchcraft'' that were conducted with the intention of causing harm. Early in the 14th century, ''maleficium'' was one of the charges leveled against the Knights Templar

, colors = White mantle with a red cross

, colors_label = Attire

, march =

, mascot = Two knights riding a single horse

, equipment ...

.

''Maleficium'' was defined as "the practice of malevolent magic, derived from casting lots as a means of divining the future in the ancient Mediterranean world", or as "an act of witchcraft performed with the intention of causing damage or injury; the resultant harm." In general, the term applies to any magical act intended to cause harm or death to people or property. Lewis and Russell stated, "''Maleficium'' was a threat not only to individuals but also to public order, for a community wracked by suspicions about witches could split asunder". Those accused of maleficium were punished by being imprisoned or even executed.

Sorcery came to be associated with the Old Testament figure of Solomon

Solomon (; , ),, ; ar, سُلَيْمَان, ', , ; el, Σολομών, ; la, Salomon also called Jedidiah (Hebrew language, Hebrew: , Modern Hebrew, Modern: , Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yăḏīḏăyāh'', "beloved of Yahweh, Yah"), ...

; various grimoire

A grimoire ( ) (also known as a "book of spells" or a "spellbook") is a textbook of magic, typically including instructions on how to create magical objects like talismans and amulets, how to perform magical spells, charms and divination, and ...

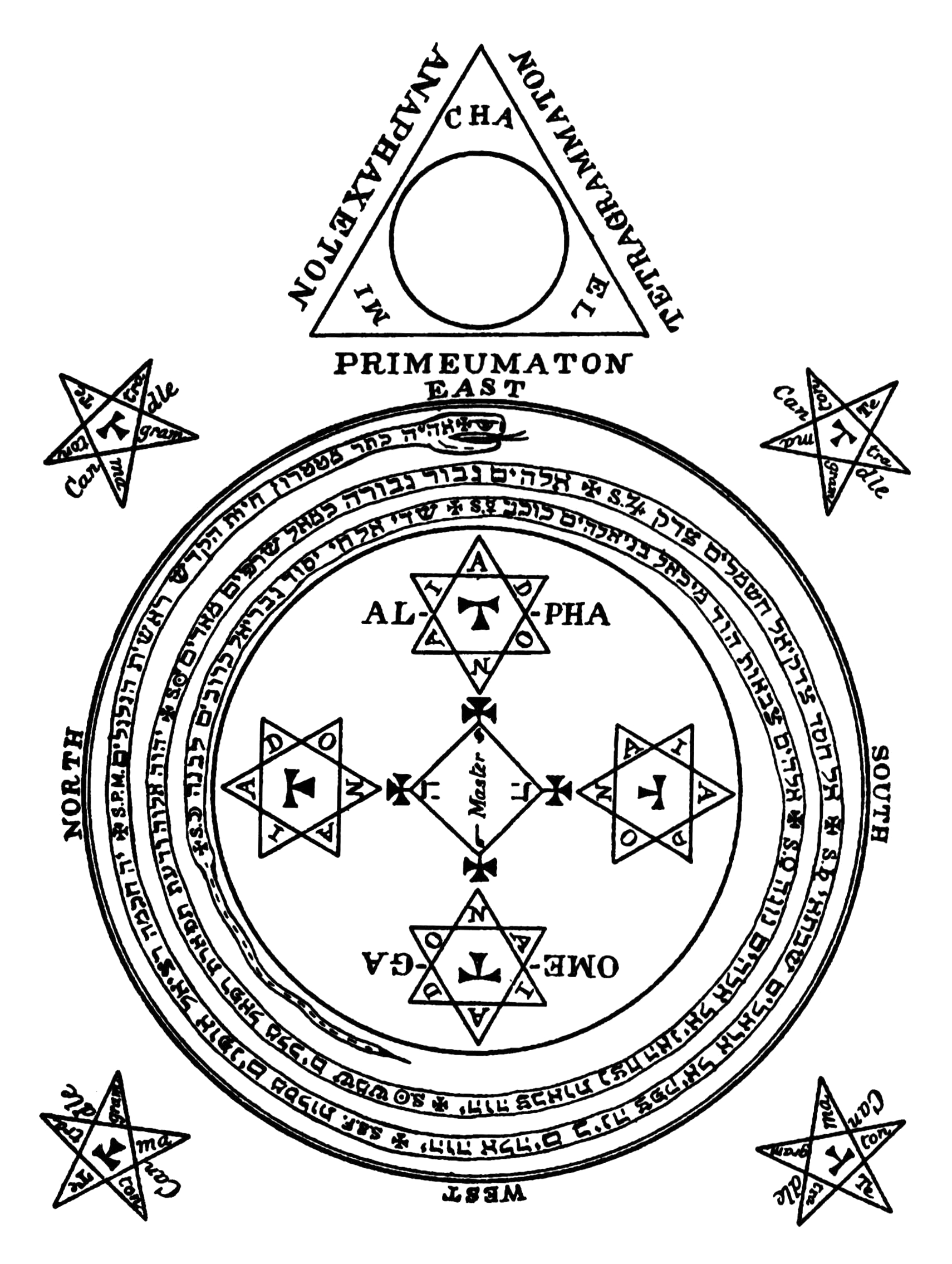

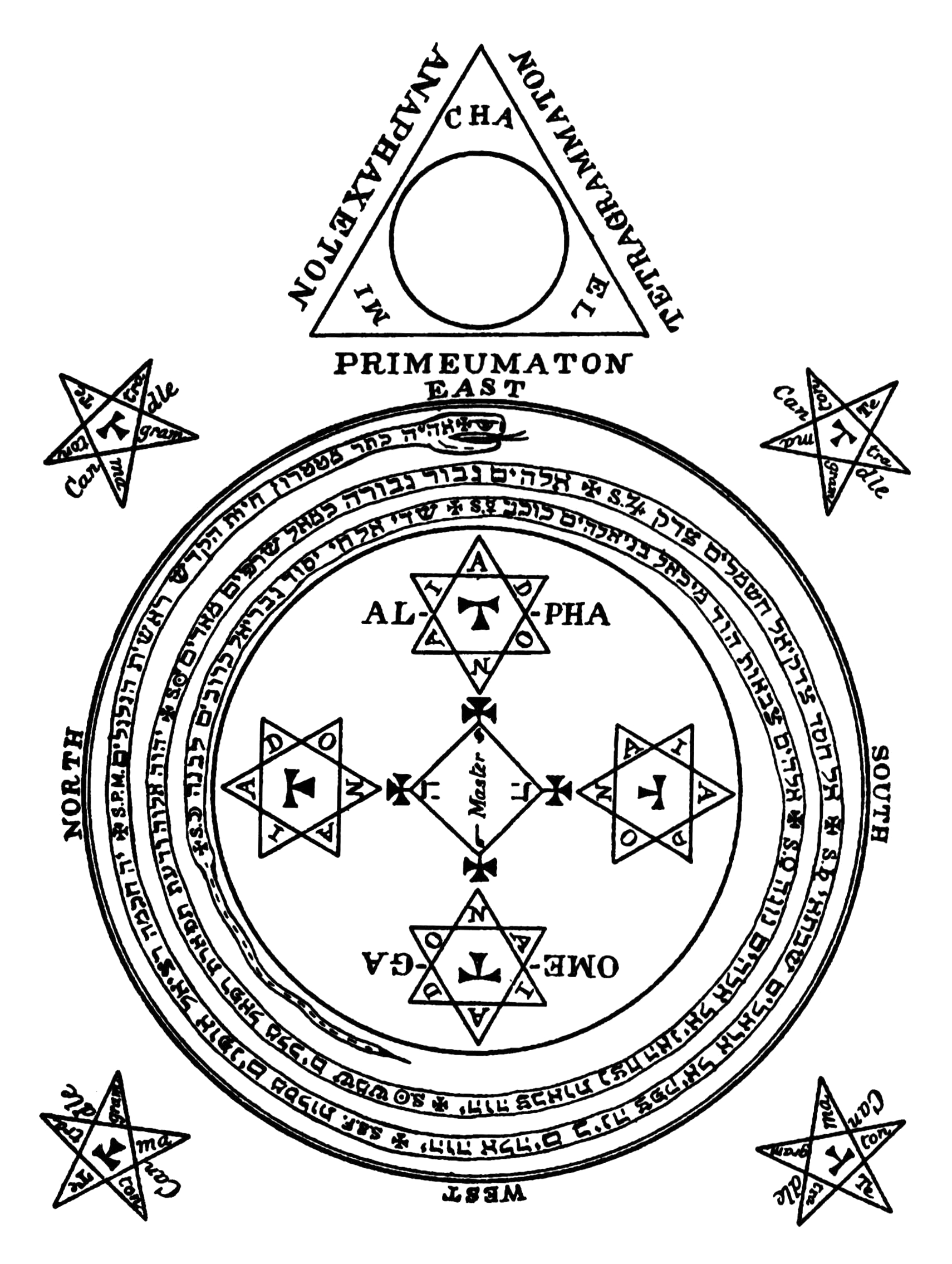

s, or books outlining magical practices, were written that claimed to have been written by Solomon. One well-known goetic grimoire is the ''Ars Goetia

''The Lesser Key of Solomon'', also known as ''Lemegeton Clavicula Salomonis'' or simply ''Lemegeton'', is an anonymous grimoire on demonology. It was compiled in the mid-17th century, mostly from materials a couple of centuries older.''Lemegeto ...

'', included in the 16th-century text known as ''The Lesser Key of Solomon

''The Lesser Key of Solomon'', also known as ''Lemegeton Clavicula Salomonis'' or simply ''Lemegeton'', is an anonymous grimoire on demonology. It was compiled in the mid-17th century, mostly from materials a couple of centuries older.''Lemegeto ...

'', which was likely compiled from materials several centuries older.

One of the most obvious sources for the ''Ars Goetia'' is Johann Weyer

Johann Weyer or Johannes Wier ( la, Ioannes Wierus or '; 1515 – 24 February 1588) was a Dutch physician, occultist and demonologist, disciple and follower of Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa.

He was among the first to publish against t ...

's ''Pseudomonarchia Daemonum

''Pseudomonarchia Daemonum'', or ''False Monarchy of Demons'', first appears as an Appendix to ''De praestigiis daemonum'' (1577) by Johann Weyer.Pseudomonarchia Daemonum (Liber officiorum spirituum); Johann Weyer, ed. Joseph Peterson; 2000. Avai ...

'' in his ''De praestigiis daemonum

''De praestigiis daemonum'', translated as ''On the Tricks of Demons'', is a book by medical doctor Johann Weyer, also known as Wier, first published in Basel in 1563. The book argues that witchcraft does not exist and that those who claim to pr ...

'' (1577). Weyer relates that his source for this intelligence was a book called '' Liber officiorum spirituum, seu liber dictus Empto Salomonis, de principibus et regibus demoniorum'' ("The book of the offices of spirits, or the book called Empto, by Solomon, about the princes and kings of demons"). Weyer does not cite, and is unaware of, any other books in the ''Lemegeton'', suggesting that the ''Lemegeton'' was derived from his work, not the other way around. Additionally, some material came from Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (; ; 14 September 1486 – 18 February 1535) was a German polymath, physician, legal scholar, soldier, theologian, and occult writer. Agrippa's ''Three Books of Occult Philosophy'' published in 1533 drew ...

's ''Three Books of Occult Philosophy

''Three Books of Occult Philosophy'' (''De Occulta Philosophia libri III'') is Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa's study of occult philosophy, acknowledged as a significant contribution to the Renaissance philosophical discussion concerning the power ...

'' (1533), and the ''Heptameron'' by pseudo-Pietro d'Abano.

The later Middle Ages saw words for these practitioners of harmful magical acts appear in various European languages: ''sorcière'' in French, ''Hexe'' in German, ''strega'' in Italian, and ''bruja'' in Spanish. The English term for malevolent practitioners of magic, witch, derived from the earlier Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

term ''wicce''. A person that performs sorcery is referred to as a ''sorcerer'' or a ''witch

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of Magic (supernatural), magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In Middle Ages, medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually ...

'', conceived as someone who tries to reshape the world through the occult. The word ''witch'' is over a thousand years old: Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

formed the compound from ('witch') and ('craft'). The masculine form was ('male sorcerer'). In early modern Scots, the word warlock

A warlock is a male practitioner of witchcraft.

Etymology and terminology

The most commonly accepted etymology derives ''warlock'' from the Old English '' wǣrloga'', which meant "breaker of oaths" or "deceiver" and was given special applicatio ...

came to be used as the male equivalent of witch

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of Magic (supernatural), magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In Middle Ages, medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually ...

(which can be male or female, but is used predominantly for females).

Probably the best-known characteristic of a sorcerer or witch is their ability to cast a spell—a set of words, a formula or verse, a ritual, or a combination of these, employed to do magic. Spells traditionally were cast by many methods, such as by the inscription of glyph

A glyph () is any kind of purposeful mark. In typography, a glyph is "the specific shape, design, or representation of a character". It is a particular graphical representation, in a particular typeface, of an element of written language. A g ...

s or sigil

A sigil () is a type of symbol used in magic. The term has usually referred to a pictorial signature of a deity or spirit. In modern usage, especially in the context of chaos magic, sigil refers to a symbolic representation of the practitioner ...

s on an object to give that object magical powers; by the immolation or binding of a wax or clay image (poppet

In folk magic and witchcraft, a poppet (also known as poppit, moppet, mommet or pippy) is a doll made to represent a person, for casting spells on that person or to aid that person through magic. They are occasionally found lodged in chimneys. T ...

) of a person to affect them magically; by the recitation of incantation

An incantation, a spell, a charm, an enchantment or a bewitchery, is a magical formula intended to trigger a magical effect on a person or objects. The formula can be spoken, sung or chanted. An incantation can also be performed during ceremo ...

s; by the performance of physical ritual

A ritual is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or objects, performed according to a set sequence. Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a community, including a religious community. Rituals are characterized, b ...

s; by the employment of magical herb

In general use, herbs are a widely distributed and widespread group of plants, excluding vegetables and other plants consumed for macronutrients, with savory or aromatic properties that are used for flavoring and garnishing food, for medicinal ...

s as amulets or potion

A potion () is a liquid "that contains medicine, poison, or something that is supposed to have magic powers.” It derives from the Latin word ''potus'' which referred to a drink or drinking. The term philtre is also used, often specifically ...

s; by gazing at mirrors, swords or other specula (scrying

Scrying, also known by various names such as "seeing" or "peeping", is the practice of looking into a suitable medium in the hope of detecting significant messages or visions. The objective might be personal guidance, prophecy, revelation, or in ...

) for purposes of divination; and by many other means.

During the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

, the many magical practices and rituals of ''goetia'' were considered evil or irreligious and by extension, black magic in the broad sense. Witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have us ...

and non-mainstream esoteric study were prohibited and targeted by the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

..

European witch-hunts and witch-trials

In

In Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

, sorcery came to be associated with heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

and apostasy

Apostasy (; grc-gre, ἀποστασία , 'a defection or revolt') is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that i ...

and to be viewed as evil. Among the Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, Protestants, and secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

leadership of the Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

an Early Modern period, fears about sorcery and witchcraft rose to fever pitch and sometimes led to large-scale witch-hunt

A witch-hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. The Witch trials in the early modern period, classical period of witch-hunts in Early Modern Europe and European Colon ...

s. The key century was the fifteenth, which saw a dramatic rise in awareness and terror of witchcraft, culminating in the publication of the but prepared by such fanatical popular preachers as Bernardino of Siena.

The ''Malleus Maleficarum

The ''Malleus Maleficarum'', usually translated as the ''Hammer of Witches'', is the best known treatise on witchcraft. It was written by the German Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer (under his Latinized name ''Henricus Institor'') and first ...

,'' (Latin for 'Hammer of The Witches') was a witch-hunting manual written in 1486 by two German monks, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger. It was used by both Catholics and Protestants for several hundred years, outlining how to identify a witch, what makes a woman more likely than a man to be a witch, how to put a witch on trial, and how to punish a witch. The book defines a witch as evil and typically female. The book became the handbook for secular courts throughout Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

Europe, but was not used by the Inquisition, which even cautioned against relying on the work. In total, tens or hundreds of thousands of people were executed, and others were imprisoned, tortured, banished, and had lands and possessions confiscated. The majority of those accused were women, though in some regions the majority were men.

Johann Weyer

Johann Weyer or Johannes Wier ( la, Ioannes Wierus or '; 1515 – 24 February 1588) was a Dutch physician, occultist and demonologist, disciple and follower of Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa.

He was among the first to publish against t ...

(1515–1588) was a Dutch physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

, occultist

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism an ...

and demonologist

Demonology is the study of demons within religious belief and myth. Depending on context, it can refer to studies within theology, religious doctrine, or pseudoscience. In many faiths, it concerns the study of a hierarchy of demons. Demons may be ...

, and a disciple and follower of Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (; ; 14 September 1486 – 18 February 1535) was a German polymath, physician, legal scholar, soldier, theologian, and occult writer. Agrippa's ''Three Books of Occult Philosophy'' published in 1533 drew ...

. He was among the first to publish against the persecution of witch

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of Magic (supernatural), magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In Middle Ages, medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually ...

es. His most influential work is ('On the Illusions of the Demons and on Spells and Poisons'; 1563).

In 1584, the English writer Reginald Scot

Reginald Scot (or Scott) ( – 9 October 1599) was an Englishman and Member of Parliament, the author of ''The Discoverie of Witchcraft'', which was published in 1584. It was written against the belief in witches, to show that witchcraft did ...

published ''The Discoverie of Witchcraft