Soong Meiling on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Soong Mei-ling (also spelled Soong May-ling, ; March 5, 1898 – October 23, 2003), also known as Madame Chiang Kai-shek or Madame Chiang, was a Chinese political figure who was

In Shanghai, May-ling attended the

In Shanghai, May-ling attended the

Soong Mei-ling met

Soong Mei-ling met

Although Soong Mei-ling initially avoided the public eye after marrying Chiang, she soon began an ambitious social welfare project to establish schools for the orphans of Chinese soldiers. The orphanages were well-appointed: with playgrounds, hotels, swimming pools, a gymnasium, model classrooms, and dormitories. Soong Mei-ling was deeply involved in the project and even picked all of the teachers herself. There were two schools - one for boys and one for girls—built on a site at the foot of

Although Soong Mei-ling initially avoided the public eye after marrying Chiang, she soon began an ambitious social welfare project to establish schools for the orphans of Chinese soldiers. The orphanages were well-appointed: with playgrounds, hotels, swimming pools, a gymnasium, model classrooms, and dormitories. Soong Mei-ling was deeply involved in the project and even picked all of the teachers herself. There were two schools - one for boys and one for girls—built on a site at the foot of

After the death of her husband in 1975, Madame Chiang assumed a low profile. She was first diagnosed with

After the death of her husband in 1975, Madame Chiang assumed a low profile. She was first diagnosed with

The New York Times obituary wrote:

*''Life'' magazine called Madame the "most powerful woman in the world."

*''Liberty'' magazine described her as "the real brains and boss of the Chinese government."

*

The New York Times obituary wrote:

*''Life'' magazine called Madame the "most powerful woman in the world."

*''Liberty'' magazine described her as "the real brains and boss of the Chinese government."

*

Grand Cross of Order of the Sun of Peru (1961)

*:

**

Grand Cross of Order of the Sun of Peru (1961)

*:

**

File:Chinese Florence Nightingale.jpg, Soong giving a bandage to an injured Chinese soldier (c. 1942)Fenby, Jonathan (2009), Modern China, p. 279

File:1943 Chiang Kai-shek and Soong May-ling.jpg, Chiang and Soong in 1943

File:Soong May-ling stitching uniform for soldiers.jpg, Soong stitching uniforms for

Soong Mei-ling and the China Air Force

1995: US senators held a reception for Soong Mei-ling in recognition of China's role as a US ally in World War II.

Preview at Google Books

*

Preview at Google Books

*

Preview at Internet Archive

* *

Preview at Internet Archive

*

Preview at Google Books

Audio of her speaking at the Hollywood Bowl, 1943 (3 hours into program)

* * ttps://web.archive.org/web/20070329012515/http://www.time.com/time/subscriber/personoftheyear/archive/stories/1937.html ''Time'' magazine's "Man and Wife of the Year," 1937

Madame Chiang being honored by U.S. Senate Majority Leader Robert Dole

(left) and Senator Paul Simon (center) at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, DC, July 26, 1995

Life in pictures: Madame Chiang Kai-shek

Voice of America obituary

* ttps://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/nov/05/china.jonathanfenby The extraordinary secret of Madame Chiang Kai-shek

Madame Chiang Kai-shek - The Economist

What a 71-Year-Old Article by Madame Chiang Kai-Shek Tells Us About China Today - The Atlantic

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Soong, May-Ling 1898 births 2003 deaths Republic of China politicians from Shanghai Burials at Ferncliff Cemetery Chinese anti-communists Chinese centenarians Chinese Methodists Chinese people of World War II Chiang Kai-shek family Kuomintang politicians in Taiwan Women in China Sun Yat-sen family First Ladies of the Republic of China Wellesley College alumni Women leaders of China Articles containing video clips Female army generals Chinese Civil War refugees Taiwanese people from Shanghai Taiwanese centenarians Time Person of the Year Women centenarians American anti-communists Grand Crosses of the Order of the Sun of Peru Recipients of the Order of Merit for National Foundation

First Lady of the Republic of China

The First Lady of the Republic of China refers to the wife of the President of the Republic of China. Since 1949, the position has been based in Taiwan, where they are often called by the title of First Lady of Taiwan, in addition to First Lady ...

, the wife of Generalissimo

''Generalissimo'' ( ) is a military rank of the highest degree, superior to field marshal and other five-star ranks in the states where they are used.

Usage

The word (), an Italian term, is the absolute superlative of ('general') thus me ...

and President Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

. Soong played a prominent role in the politics of the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

and was the sister-in-law of Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

, the founder and the leader of the Republic of China. She was active in the civic life of her country and held many honorary and active positions, including chairwoman of Fu Jen Catholic University

Fu Jen Catholic University (FJU, FJCU or Fu Jen; or ) is a private Catholic university in Xinzhuang, New Taipei City, Taiwan. The university was founded in 1925 in Beijing at the request of Pope Pius XI and re-established in Taiwan in 1961 at ...

. During World War 2

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, she rallied against the Japanese; and in 1943 conducted an eight-month speaking tour of the United States of America to gain support.

Early life

She was born in her family home, a traditional house called Neishidi (內史第), inPudong

Pudong is a district of Shanghai located east of the Huangpu, the river which flows through central Shanghai. The name ''Pudong'' was originally applied to the Huangpu's east bank, directly across from the west bank or Puxi, the historic city ...

, Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flow ...

. She was born on March 5, 1898, though some biographies give the year as 1897, since Chinese tradition considers one to be a year old at birth.While records at Wellesley College and the Encyclopædia Britannica indicate she was born in 1897, the Republic of China government as well as the BBC and the ''New York Times'' cite her year of birth as 1898. The ''New York Times'' obituary includes the following explanation: "Some references give 1897 as the year because the Chinese usually consider everyone to be one year old at birth." cf: East Asian age reckoning

Countries in the East Asian cultural sphere (China, Korea, Japan, Vietnam, and their diasporas) have traditionally used specific methods of reckoning a person's numerical age based not on their birthday but the calendar year, and what age one is ...

. However, early sources such as the Columbia Encyclopedia, 1960, give her date of birth as 1896, making it possible that "one year" was subtracted twice.

She was the fourth of six children of Charlie Soong

Charles Jones Soong ( zh, c=宋嘉澍, p=Sòng Jiāshù, w=Sung Chia-shu; October 17, 1861 – May 3, 1918), also known by his courtesy name Soong Yao-ju ( zh, c=宋耀如, p=Sòng Yàorú, w=Sung Yao-ju), was a Chinese businessman who first achi ...

, a wealthy businessman and former Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's b ...

missionary from Hainan

Hainan (, ; ) is the smallest and southernmost province of the People's Republic of China (PRC), consisting of various islands in the South China Sea. , the largest and most populous island in China,The island of Taiwan, which is slightly l ...

, and his wife Ni Kwei-tseng (). Mei-ling's siblings were sister Ai-ling, sister Ching-ling, who later became Madame Sun Yat-sen, older brother Tse-ven, usually known as T. V. Soong, and younger brothers Tse-liang (T.L.) and Tse-an (T.A.)

Education

In Shanghai, May-ling attended the

In Shanghai, May-ling attended the McTyeire School

McTyeire School () was a private girls' school in Shanghai.

It was established by Young John Allen and Laura Askew Haygood in 1882. Its namesake was Holland Nimmons McTyeire.

History

The school had seven students in 1855 and more than 100 studen ...

for Girls with her sister, Ching-ling. Their father, who had studied in the United States, arranged to have them continue their education in the US in 1907. May-ling and Ching-ling attended a private school in Summit, New Jersey

Summit is a city in Union County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. The city is located on a ridge in northern- central New Jersey, within the Raritan Valley and Rahway Valley regions in the New York metropolitan area. At the 2010 United Sta ...

. In 1908, Ching-ling was accepted by her sister Ai-ling's alma mater, Wesleyan College

Wesleyan College is a private, liberal arts women's college in Macon, Georgia. Founded in 1836, Wesleyan was the first college in the world chartered to grant degrees to women.

History

The school was chartered on December 23, 1836, as the Geo ...

, at age 15 and both sisters moved to Macon, Georgia

Macon ( ), officially Macon–Bibb County, is a consolidated city-county in the U.S. state of Georgia. Situated near the fall line of the Ocmulgee River, it is located southeast of Atlanta and lies near the geographic center of the state of Geo ...

, to join Ai-ling. May-ling insisted she have her way and be allowed to accompany her older sister though she was only ten, which she did. May-ling spent the year in Demorest, Georgia

Demorest is a city in Habersham County, Georgia, United States. The population was 1,823 at the 2010 census, up from 1,465 at the 2000 census. It is the home of Piedmont University.

Geography

Demorest is located in south-central Habersham County ...

, with Ai-ling's Wesleyan friend, Blanche Moss, who enrolled May-ling as an 8th grader at Piedmont College

Piedmont University is a private university in Demorest and Athens, Georgia. Founded in 1897, Piedmont's Demorest campus includes 300 acres in a traditional residential-college setting located in the foothills of the northeast Georgia Blue Rid ...

. In 1909, Wesleyan's newly appointed president, William Newman Ainsworth, gave her permission to stay at Wesleyan and assigned her tutors. She briefly attended Fairmount College in Monteagle, Tennessee

Monteagle is a town in Franklin, Grundy, and Marion counties in the U.S. state of Tennessee, in the Cumberland Plateau region of the southeastern part of the state. The population was 1,238 at the 2000 census – 804 of the town's 1,238 resi ...

in 1910.

May-ling was officially registered as a freshman at Wesleyan in 1912 at the age of 15. She then transferred to Wellesley College

Wellesley College is a private women's liberal arts college in Wellesley, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1870 by Henry and Pauline Durant as a female seminary, it is a member of the original Seven Sisters Colleges, an unofficial g ...

two years later to be closer to her older brother, T. V., who, at the time, was studying at Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

. By then, both her sisters had graduated and returned to Shanghai. She graduated from Wellesley as one of the 33 "Durant Scholars" on June 19, 1917, with a major in English literature

English literature is literature written in the English language from United Kingdom, its crown dependencies, the Republic of Ireland, the United States, and the countries of the former British Empire. ''The Encyclopaedia Britannica'' defines E ...

and minor in philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

. She was also a member of Tau Zeta Epsilon, Wellesley's Arts and Music Society. As a result of being educated in English all her life, she spoke excellent English, with a southern accent which helped her connect with American audiences.

Madame Chiang

Soong Mei-ling met

Soong Mei-ling met Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

in 1920. Since he was eleven years her elder, already married, and a Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

, Mei-ling's mother vehemently opposed the marriage between the two, but finally agreed after Chiang showed proof of his divorce and promised to convert to Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

. Chiang told his future mother-in-law that he could not convert immediately, because religion needed to be gradually absorbed, not swallowed like a pill. They married in Shanghai on December 1, 1927. While biographers regard the marriage with varying appraisals of partnership, love, politics and competition, it lasted 48 years. The couple had no children. They renewed their wedding vows on May 24, 1944, at St. Bartholomew's Church in New York City. Polly Smith sang the Lord's Prayer at the ceremony.

Madame Chiang initiated the New Life Movement The New Life Movement () was a government-led civic campaign in the 1930s Republic of China to promote cultural reform and Neo-Confucian social morality and to ultimately unite China under a centralised ideology following the emergence of ideologica ...

and became actively engaged in Chinese politics. In 1928, she was made a member of the Committee of Yuans by Chiang. She was a member of the Legislative Yuan

The Legislative Yuan is the unicameral legislature of the Republic of China (Taiwan) located in Taipei. The Legislative Yuan is composed of 113 members, who are directly elected for 4-year terms by people of the Taiwan Area through a parallel v ...

from 1930 to 1932 and Secretary-General of the Chinese Aeronautical Affairs Commission from 1936 to 1938. In 1937 she led appeals to women to support the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

, which led to the establishment of women's battalions, such as the Guangxi Women's Battalion.

In 1945 she became a member of the Central Executive Committee of the Kuomintang

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

. As her husband rose to become Generalissimo and leader of the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

, Madame Chiang acted as his English translator, secretary and advisor. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Madame Chiang tried to promote the Chinese cause and build a legacy for her husband. Well-versed in both Chinese and Western culture, she became popular both in China and abroad.

In 1934, Soong Mei-ling was given a villa in Kuling town, Lu Mountain. She and her husband Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

both loved the villa very much. Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

named the villa ''Mei Lu Villa'' to symbolize the beauty of Lu Mountain. The couple usually stayed at this villa in Kuling town, Lu Mountain in summertime, so the mountain is called Summer Capital, and the villa is called the Summer Palace.

"Warphans"

Although Soong Mei-ling initially avoided the public eye after marrying Chiang, she soon began an ambitious social welfare project to establish schools for the orphans of Chinese soldiers. The orphanages were well-appointed: with playgrounds, hotels, swimming pools, a gymnasium, model classrooms, and dormitories. Soong Mei-ling was deeply involved in the project and even picked all of the teachers herself. There were two schools - one for boys and one for girls—built on a site at the foot of

Although Soong Mei-ling initially avoided the public eye after marrying Chiang, she soon began an ambitious social welfare project to establish schools for the orphans of Chinese soldiers. The orphanages were well-appointed: with playgrounds, hotels, swimming pools, a gymnasium, model classrooms, and dormitories. Soong Mei-ling was deeply involved in the project and even picked all of the teachers herself. There were two schools - one for boys and one for girls—built on a site at the foot of Purple Mountain Purple Mountain may refer to:

China

* Purple Mountain (Nanjing), a mountain in Nanjing, Jiangsu

Ireland

* Purple Mountain (Kerry), a mountain in County Kerry

United States

* Purple Mountain (Alaska), a mountain in Alaska

* Purple Peak (Col ...

, in Nanjing. She referred to these children as her "warphans" and made them a personal cause. The fate of the children of fallen soldiers became a much more important issue in China after the beginning of the war with Japan in 1937. In order to better provide for these children she established the Chinese Women's National War Relief Society.

Visits to the U.S.

Soong Mei-ling made several tours to theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

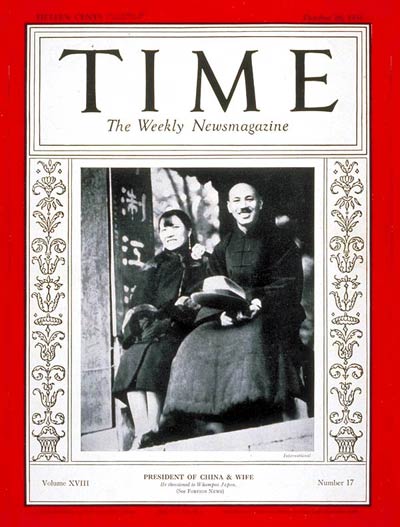

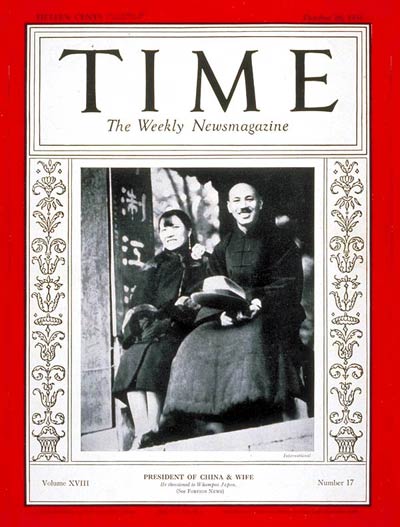

to lobby support for the Nationalists' war effort. She drew crowds as large as 30,000 people and in 1943 made the cover of ''TIME

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'' magazine for a third time. She had earlier appeared on the October 26, 1931, cover alongside her husband and on the January 3, 1937, cover with her husband as " Man and Wife of the Year."

Arguably showing the impact of her visits, in 1943, the United States Women's Army Corps recruited a unit of Chinese-American women to serve with the Army Air Forces as "Air WACs", referred to as the "Madame Chiang Kai-Shek Air WAC unit".

Both Soong Mei-ling and her husband were on good terms with ''Time'' magazine senior editor and co-founder Henry Luce

Henry Robinson Luce (April 3, 1898 – February 28, 1967) was an American magazine magnate who founded ''Time'', ''Life'', ''Fortune'', and ''Sports Illustrated'' magazine. He has been called "the most influential private citizen in the America ...

, who frequently tried to rally money and support from the American public for the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

. On February 18, 1943, she became the first Chinese national and the second woman to address both houses of the US Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washingto ...

. After the defeat of her husband's government in the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on m ...

in 1949, Madame Chiang followed her husband to Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

, while her sister Soong Ching-ling

Rosamond Soong Ch'ing-ling (27 January 189329 May 1981) was a Chinese political figure. As the third wife of Sun Yat-sen, then Premier of the Kuomintang and President of the Republic of China, she was often referred to as Madame Sun Yat-sen. ...

stayed in mainland China

"Mainland China" is a geopolitical term defined as the territory governed by the People's Republic of China (including islands like Hainan or Chongming), excluding dependent territories of the PRC, and other territories within Greater China. ...

, siding with the communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a so ...

. Madame Chiang continued to play a prominent international role. She was a Patron of the International Red Cross Committee

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure respect for all human beings, a ...

, honorary chair of the British United Aid to China Fund, and First Honorary Member of the Bill of Rights Commemorative Society.

Later life

After the death of her husband in 1975, Madame Chiang assumed a low profile. She was first diagnosed with

After the death of her husband in 1975, Madame Chiang assumed a low profile. She was first diagnosed with breast cancer

Breast cancer is cancer that develops from breast tissue. Signs of breast cancer may include a lump in the breast, a change in breast shape, dimpling of the skin, milk rejection, fluid coming from the nipple, a newly inverted nipple, or a re ...

in 1975 and would undergo two mastectomies in Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

. She also had an ovarian tumor removed in 1991.

Chang Hsien-yi

Chang Hsien-yi (; born 1943) served as deputy director of Taiwan's Institute of Nuclear Energy Research (INER) before defecting to the United States of America in 1988. Recruited by the CIA, he exposed the secret nuclear program of Taiwan to the ...

claimed that Soong Mei-ling and military officials loyal to her expedited the development of nuclear weapons and even set up a parallel chain of command to further their agenda.

Chiang Kai-shek was succeeded to power by his eldest son Chiang Ching-kuo

Chiang Ching-kuo (27 April 1910 – 13 January 1988) was a politician of the Republic of China after its retreat to Taiwan. The eldest and only biological son of former president Chiang Kai-shek, he held numerous posts in the government ...

, from a previous marriage, with whom Madame Chiang had rocky relations. In 1975, she emigrated from Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

to her family's 36 acre (14.6 hectare) estate in Lattingtown, New York

Lattingtown is a Administrative divisions of New York#Village, village located within the Oyster Bay (town), New York, Town of Oyster Bay in Nassau County, New York, Nassau County, on Long Island, in New York (state), New York, United States. The p ...

, where she kept a portrait of her late husband in full military regalia in her living room. She kept a residence in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire

Wolfeboro is a town in Carroll County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 6,416 at the 2020 census. A resort area situated beside Lake Winnipesaukee, Wolfeboro includes the village of Wolfeboro Falls.

History

The town was granted ...

, where she vacationed in the summer. Madame Chiang returned to Taiwan upon Chiang Ching-kuo's death in 1988, to shore up support among her old allies. However, Chiang Ching-kuo's successor, Lee Teng-hui

Lee Teng-hui (; 15 January 192330 July 2020) was a Taiwanese statesman and economist who served as President of the Republic of China (Taiwan) under the 1947 Constitution and chairman of the Kuomintang (KMT) from 1988 to 2000. He was the fir ...

, proved more adept at politics than she was, and consolidated his position. She again returned to the U.S. and made a rare public appearance in 1995 when she attended a reception held on Capitol Hill

Capitol Hill, in addition to being a metonym for the United States Congress, is the largest historic residential neighborhood in Washington, D.C., stretching easterly in front of the United States Capitol along wide avenues. It is one of the ...

in her honor in connection with celebrations of the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II. Madame Chiang made her last visit to Taiwan in 1995. In the 2000 Presidential Election on Taiwan, the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

produced a letter from her in which she purportedly supported the KMT candidate Lien Chan

Lien Chan (; born 27 August 1936) is a Taiwanese politician. He was the Chairman of the Taiwan Provincial Government from 1990 to 1993, Premier of the Republic of China from 1993 to 1997, Vice President of the Republic of China from 1996 to 20 ...

over independent candidate James Soong

James Soong Chu-yu (born 16 March 1942) is a Taiwanese politician. He is the founder and current Chairman of the People First Party.

Born to a Kuomintang military family of Hunanese origin, Soong began his political career as a secretary to ...

(no relation). James Soong never disputed the authenticity of the letter. Soong sold her Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United Sta ...

estate in 2000 and spent the rest of her life in a Gracie Square apartment on the Upper East Side

The Upper East Side, sometimes abbreviated UES, is a neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 96th Street to the north, the East River to the east, 59th Street to the south, and Central Park/Fifth Avenue to the wes ...

of Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

owned by her niece. An open house viewing of the estate drew many Taiwanese expatriates. When Madame Chiang was 103 years old, she had an exhibition of her Chinese paintings in New York.

Death

Madame Chiang died in her sleep inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, in her Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

apartment on October 23, 2003, at the age of 105. Her remains were interred at Ferncliff Cemetery

Ferncliff Cemetery and Mausoleum is located at 280 Secor Road in the hamlet of Hartsdale, town of Greenburgh, Westchester County, New York, United States, about north of Midtown Manhattan. It was founded in 1902, and is non-sectarian. Ferncliff ...

in Hartsdale, New York

Hartsdale is a hamlet located in the town of Greenburgh, Westchester County, New York, United States. The population was 5,293 at the 2010 census. It is a suburb of New York City.

History

Hartsdale, a CDP/hamlet/post-office in the town of Greenb ...

, pending an eventual burial with her late husband who was entombed in Cihu

Cihu Mausoleum (), officially known as the Mausoleum of Late President Chiang () or President Chiang Kai-shek Mausoleum, is the final resting place of President Chiang Kai-shek. It is located in Daxi District, Taoyuan City, Taiwan. When Chiang Kai ...

, Taiwan. The stated intention is to have them both buried in mainland China once political differences are resolved.

Upon her death, The White House released a statement:

Jia Qinglin

Jia Qinglin (; born 13 March 1940) is a retired senior leader of the People's Republic of China and of the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP). He was a member of the CCP's Politburo Standing Committee, the party's highest ruling organ, between ...

, chairman of the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference

The Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC, zh, 中国人民政治协商会议), also known as the People's PCC (, ) or simply the PCC (), is a political advisory body in the People's Republic of China and a central part of ...

(CPPCC), sent a telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

to Soong's relatives where he expressed deep condolences on her death.

Appraisals by international press

The New York Times obituary wrote:

*''Life'' magazine called Madame the "most powerful woman in the world."

*''Liberty'' magazine described her as "the real brains and boss of the Chinese government."

*

The New York Times obituary wrote:

*''Life'' magazine called Madame the "most powerful woman in the world."

*''Liberty'' magazine described her as "the real brains and boss of the Chinese government."

*Clare Boothe Luce

Clare Boothe Luce ( Ann Clare Boothe; March 10, 1903 – October 9, 1987) was an American writer, politician, U.S. ambassador, and public conservative figure. A versatile author, she is best known for her 1936 hit play '' The Women'', which h ...

compared her to Joan of Arc

Joan of Arc (french: link=yes, Jeanne d'Arc, translit= �an daʁk} ; 1412 – 30 May 1431) is a patron saint of France, honored as a defender of the French nation for her role in the siege of Orléans and her insistence on the coronati ...

and Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English Reform movement, social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during t ...

.

*Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fic ...

called her the "empress" of China.

Awards and honors

*: ** Grand Cross of Order of the Sun of Peru (1961)

*:

**

Grand Cross of Order of the Sun of Peru (1961)

*:

**

Order of Merit for National Foundation

The Order of Merit for National Foundation (Hangul: 건국훈장) is one of South Korea's orders of merit. It is awarded by the President of South Korea for "outstanding meritorious services in the interest of founding or laying a foundation for th ...

, 1st class (1966)

In popular culture

Her tour to San Francisco is mentioned (under the name Madame Chiang) in '' Last Night at the Telegraph Club'', a 2021 novel byMalinda Lo

Malinda Lo is an American writer of young adult novels including ''Ash'', ''Huntress'', ''Adaptation'', ''Inheritance,'' ''A Line in the Dark'', and '' Last Night at the Telegraph Club''. She also does research on diversity in young adult literat ...

.

Gallery

National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; ), sometimes shortened to Revolutionary Army () before 1928, and as National Army () after 1928, was the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) from 1925 until 1947 in China ...

soldiers.

File:1943 Wellesley College speech poster.jpg, 1943 Wellesley College speech poster.

File:1942 Chiang Soong Stilwell in Burma.jpg, 1942 Chiang, Soong and Joseph Stilwell

Joseph Warren "Vinegar Joe" Stilwell (March 19, 1883 – October 12, 1946) was a United States Army general who served in the China Burma India Theater during World War II. An early American popular hero of the war for leading a column walking ...

in Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

.

File:1943 Soong May-ling in White House Oval Office.jpg, 1943 Soong in the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

Oval Office

The Oval Office is the formal working space of the President of the United States. Part of the Executive Office of the President of the United States, it is located in the West Wing of the White House, in Washington, D.C.

The oval-shaped room ...

to conduct a press conference.

File:1940s Chiang Soong Chennault.gif, Soong sitting close to Chiang opposite Claire Lee Chennault

Claire Lee Chennault (September 6, 1893 – July 27, 1958) was an American military aviator best known for his leadership of the "Flying Tigers" and the Chinese Air Force in World War II.

Chennault was a fierce advocate of "pursuit" or fighter ...

.

File:Soong sisters in their youth.jpg, The three Soong sisters in their youth, with Soong Ching-ling in the middle, and Soong Ai-ling (left) and Soong Mei-ling (right)

Internet videos

*Soong Mei-ling and the China Air Force

1995: US senators held a reception for Soong Mei-ling in recognition of China's role as a US ally in World War II.

See also

*Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

* Xi'an Incident

The Xi'an Incident, previously romanized as the Sian Incident, was a political crisis that took place in Xi'an, Shaanxi in 1936. Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Nationalist government of China, was detained by his subordinate generals Chang Hs ...

* History of the Republic of China

The history of the Republic of China begins after the Qing dynasty in 1912, when the Xinhai Revolution and the formation of the Republic of China put an end to 2,000 years of imperial rule. The Republic experienced many trials and tribulations a ...

* Military of the Republic of China

The Republic of China Armed Forces (ROC Armed Forces) are the armed forces of the Republic of China (ROC), once based in mainland China and currently in its remaining jurisdictions which include the islands of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, Mat ...

* President of the Republic of China

The president of the Republic of China, now often referred to as the president of Taiwan, is the head of state of the Republic of China (ROC), as well as the commander-in-chief of the Republic of China Armed Forces. The position once had aut ...

* Politics of the Republic of China

The Republic of China (Chinese: 中華民國政治, Pinyin: ''Zhōnghuá Mínguó de zhèngzhì'') (commonly known as Taiwan) is governed in a framework of a Representative democracy, representative democratic republic under a Five-Power ...

* Soong sisters

The Soong sisters () were Soong Ai-ling, Soong Ching-ling, and Soong Mei-ling, three Shanghainese people, Shanghainese (of Hakka people, Hakka descent) Christian Chinese women who were, along with their husbands, amongst China's most significant ...

** Soong Ai-ling

Soong Ai-ling (), legally Soong E-ling or Eling Soong (July 15, 1889 – October 18, 1973) was a Chinese businesswoman, the eldest of the Soong sisters and the wife of H. H. Kung (Kung Hsiang-Hsi), who was the richest man in the early 20th cent ...

** Soong Ching-ling

Rosamond Soong Ch'ing-ling (27 January 189329 May 1981) was a Chinese political figure. As the third wife of Sun Yat-sen, then Premier of the Kuomintang and President of the Republic of China, she was often referred to as Madame Sun Yat-sen. ...

* Claire Lee Chennault

Claire Lee Chennault (September 6, 1893 – July 27, 1958) was an American military aviator best known for his leadership of the "Flying Tigers" and the Chinese Air Force in World War II.

Chennault was a fierce advocate of "pursuit" or fighter ...

* Flying Tigers

The First American Volunteer Group (AVG) of the Republic of China Air Force, nicknamed the Flying Tigers, was formed to help oppose the Japanese invasion of China. Operating in 1941–1942, it was composed of pilots from the United States Ar ...

* Chiang Fang-liang

Faina Chiang Fang-liang (, born Faina Ipat'evna Vakhreva (russian: Фаина Ипатьевна Вахрева, be, Фаіна Іпацьеўна Вахрава; 15 May 1916 – 15 December 2004) was the First Lady of the Republic of China ...

* National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; ), sometimes shortened to Revolutionary Army () before 1928, and as National Army () after 1928, was the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) from 1925 until 1947 in China ...

* Sino-German cooperation (1911–1941)

* Address to Congress - The full text of her 1943 address

* The Last Empress: Madame Chiang Kai-shek and the Birth of Modern China - A 2009 biography of Soong Mei-ling

References

Bibliography

* *Preview at Google Books

*

Preview at Google Books

*

Preview at Internet Archive

* *

Preview at Internet Archive

*

Preview at Google Books

External links

Audio of her speaking at the Hollywood Bowl, 1943 (3 hours into program)

* * ttps://web.archive.org/web/20070329012515/http://www.time.com/time/subscriber/personoftheyear/archive/stories/1937.html ''Time'' magazine's "Man and Wife of the Year," 1937

Madame Chiang being honored by U.S. Senate Majority Leader Robert Dole

(left) and Senator Paul Simon (center) at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, DC, July 26, 1995

Life in pictures: Madame Chiang Kai-shek

Voice of America obituary

* ttps://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/nov/05/china.jonathanfenby The extraordinary secret of Madame Chiang Kai-shek

Madame Chiang Kai-shek - The Economist

What a 71-Year-Old Article by Madame Chiang Kai-Shek Tells Us About China Today - The Atlantic

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Soong, May-Ling 1898 births 2003 deaths Republic of China politicians from Shanghai Burials at Ferncliff Cemetery Chinese anti-communists Chinese centenarians Chinese Methodists Chinese people of World War II Chiang Kai-shek family Kuomintang politicians in Taiwan Women in China Sun Yat-sen family First Ladies of the Republic of China Wellesley College alumni Women leaders of China Articles containing video clips Female army generals Chinese Civil War refugees Taiwanese people from Shanghai Taiwanese centenarians Time Person of the Year Women centenarians American anti-communists Grand Crosses of the Order of the Sun of Peru Recipients of the Order of Merit for National Foundation