Soedjatmoko on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

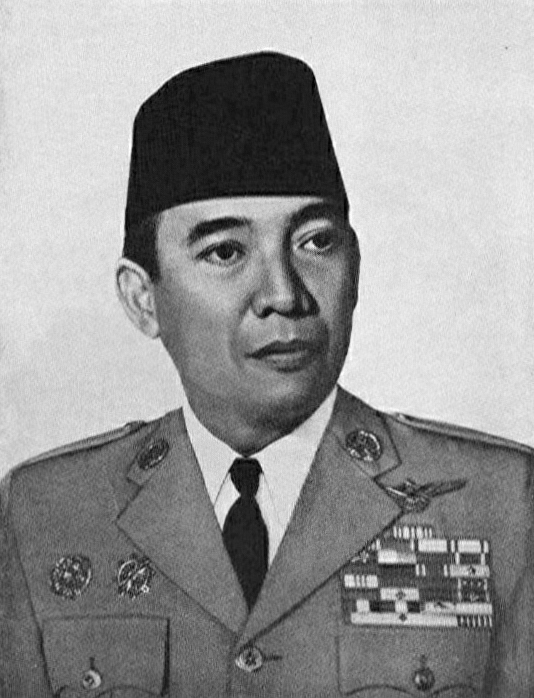

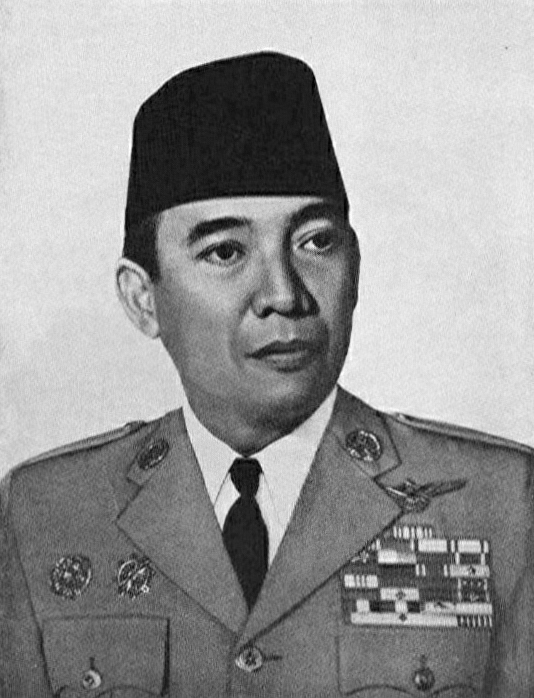

Soedjatmoko (born Soedjatmoko Mangoendiningrat; 10 January 1922 – 21 December 1989), more colloquially referred to as Bung Koko, was an Indonesian politician, intellectual and diplomat. Born to a noble father and mother in

Upon returning to Indonesia, Soedjatmoko once again became an editor of ''Siasat''. In 1952, he was one of the founders of Socialist Party daily ''Pedoman'' (''Guidance''); this was followed by a political journal, ''Konfrontasi'' (''Confrontation''). He also helped to establish the Pembangunan publishing house, which he directed until 1961. Soedjatmoko joined the

Upon returning to Indonesia, Soedjatmoko once again became an editor of ''Siasat''. In 1952, he was one of the founders of Socialist Party daily ''Pedoman'' (''Guidance''); this was followed by a political journal, ''Konfrontasi'' (''Confrontation''). He also helped to establish the Pembangunan publishing house, which he directed until 1961. Soedjatmoko joined the

Sawahlunto

Sawahlunto (Jawi script, Jawi: ) is a city in West Sumatra, Western Sumatra province, Indonesia, and lies 90 kilometres (a 2-hour drive) from Padang, the provincial capital. Sawahlunto is known as the site for the oldest coal mining site in Southe ...

, West Sumatra

West Sumatra ( id, Sumatra Barat) is a Provinces of Indonesia, province of Indonesia. It is located on the west coast of the island of Sumatra and includes the Mentawai Islands off that coast. The province has an area of , with a population of 5, ...

, after finishing his primary education, he went to Batavia (modern day Jakarta

Jakarta (; , bew, Jakarte), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta ( id, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta) is the capital and largest city of Indonesia. Lying on the northwest coast of Java, the world's most populous island, Jakarta ...

) to study medicine; in the city's slums, he saw much poverty, which became an academic interest later in life. After being expelled from medical school by the Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

in 1943 for his political activities, Soedjatmoko moved to Surakarta

Surakarta ( jv, ꦯꦸꦫꦏꦂꦠ), known colloquially as Solo ( jv, ꦱꦭ; ), is a city in Central Java, Indonesia. The 44 km2 (16.2 sq mi) city adjoins Karanganyar Regency and Boyolali Regency to the north, Karanganyar Regency and Sukoh ...

and practised medicine with his father. In 1947, after Indonesia proclaimed its independence, Soedjatmoko and two other youths were deployed to Lake Success, New York

Lake Success is a village in the Town of North Hempstead in Nassau County, on the North Shore of Long Island, in New York. The population was 2,897 at the 2010 census.

The Incorporated Village of Lake Success was the temporary home of the United ...

, to represent Indonesia at the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

(UN). They helped secure international recognition of the country's sovereignty.

After his work at the UN, Soedjatmoko attempted to study at Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

's Littauer Center for Public Administration (now the John F. Kennedy School of Government

The Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), officially the John F. Kennedy School of Government, is the school of public policy and government of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The school offers master's degrees in public policy, public ...

); however, he was forced to resign due to pressure from other work, including serving as Indonesia's first chargé d'affaires

A ''chargé d'affaires'' (), plural ''chargés d'affaires'', often shortened to ''chargé'' (French) and sometimes in colloquial English to ''charge-D'', is a diplomat who serves as an embassy's chief of mission in the absence of the ambassador ...

in London for three months as well as establishing the political desk at the Embassy of Indonesia in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

By 1952 he had returned to Indonesia, where he became involved in the socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

press and joined the Socialist Party of Indonesia

The Socialist Party of Indonesia ( id, Partai Sosialis Indonesia) was a political party in Indonesia from 1948 until 1960, when it was banned by President Sukarno.

Origins

In December 1945 Amir Sjarifoeddin's Socialist Party of Indonesia (Pars ...

. He was elected as a member of the Constitutional Assembly of Indonesia

The Constitutional Assembly ( id, Konstituante) was a body elected in 1955 to draw up a permanent constitution for the Republic of Indonesia. It sat between 10 November 1956 and 2 July 1959. It was dissolved by then President Sukarno in a decr ...

in 1955, serving until 1959; he married Ratmini Gandasubrata in 1958. However, as President Sukarno

Sukarno). (; born Koesno Sosrodihardjo, ; 6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was an Indonesian statesman, orator, revolutionary, and nationalist who was the first president of Indonesia, serving from 1945 to 1967.

Sukarno was the leader of ...

's government became more authoritarian Soedjatmoko began to criticise the government. To avoid censorship, he spent two years as a guest lecturer at Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach an ...

in Ithaca, New York

Ithaca is a city in the Finger Lakes region of New York, United States. Situated on the southern shore of Cayuga Lake, Ithaca is the seat of Tompkins County and the largest community in the Ithaca metropolitan statistical area. It is named a ...

, and another three in self-imposed unemployment in Indonesia.

After Sukarno was replaced by Suharto

Suharto (; ; 8 June 1921 – 27 January 2008) was an Indonesian army officer and politician, who served as the second and the longest serving president of Indonesia. Widely regarded as a military dictator by international observers, Suharto ...

, Soedjatmoko returned to public service. In 1966 he was sent as one of Indonesia's representatives at the UN, and in 1968 he became Indonesia's ambassador to the US; during this time he received several honorary doctoral degrees. He also advised foreign minister Adam Malik

Adam Malik Batubara (22 July 1917 – 5 September 1984), or more commonly referred to simply as Adam Malik, was an Indonesians, Indonesian politician, diplomat, and journalist, who served as the 3rd Vice President of Indonesia from 1978 until ...

. After returning to Indonesia in 1971, Soedjatmoko held a position in several think tanks. After the Malari incident in January 1974, Soedjatmoko was held for interrogation for two and a half weeks and accused of masterminding the event. Although eventually released, he could not leave Indonesia for two and a half years. In 1978 Soedjatmoko received the Ramon Magsaysay Award

The Ramon Magsaysay Award (Filipino: ''Gawad Ramon Magsaysay'') is an annual award established to perpetuate former Philippine President Ramon Magsaysay's example of integrity in governance, courageous service to the people, and pragmatic idealis ...

for International Understanding, and in 1980 he was chosen as rector of the United Nations University

The (UNU) is the think tank and academic arm of the United Nations. Headquartered in Shibuya, Tokyo, Japan, with diplomatic status as a UN institution, its mission is to help resolve global issues related to human development and welfare thro ...

in Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.468 ...

. Two years after returning from Japan, Soedjatmoko died of cardiac arrest while teaching in Yogyakarta

Yogyakarta (; jv, ꦔꦪꦺꦴꦒꦾꦏꦂꦠ ; pey, Jogjakarta) is the capital city of Special Region of Yogyakarta in Indonesia, in the south-central part of the island of Java. As the only Indonesian royal city still ruled by a monarchy, ...

.

Early life

Soedjatmoko was born on 10 January 1922 inSawahlunto

Sawahlunto (Jawi script, Jawi: ) is a city in West Sumatra, Western Sumatra province, Indonesia, and lies 90 kilometres (a 2-hour drive) from Padang, the provincial capital. Sawahlunto is known as the site for the oldest coal mining site in Southe ...

, West Sumatra

West Sumatra ( id, Sumatra Barat) is a Provinces of Indonesia, province of Indonesia. It is located on the west coast of the island of Sumatra and includes the Mentawai Islands off that coast. The province has an area of , with a population of 5, ...

, with the name Soedjatmoko Mangoendiningrat. He was the eldest son of Saleh Mangoendiningrat, a Javanese physician of noble descent from Madiun

Madiun ( jv, ꦑꦸꦛꦩꦝꦶꦪꦸꦤ꧀, translit=Kutha Madhiun) is a landlocked city in the western part of East Java, Indonesia, known for its agricultural center. It was formerly (until 2010) the capital of the Madiun Regency, but is now adm ...

, and Isnadikin, a Javanese housewife from Ponorogo

Ponorogo Regency ( id, Kabupaten Ponorogo; jv, ꦑꦧꦸꦥꦠꦺꦤ꧀ꦦꦤꦫꦒ, translit=Kabupatèn Pånårågå) is a regency (''kabupaten'') of East Java, Indonesia. It is considered the birthplace of Reog Ponorogo, a traditional Indone ...

; the couple had three other children, as well as two adopted children. Soedjatmoko's younger brother, Nugroho Wisnumurti, went on to work at the United Nations. His younger sister Miriam Budiardjo

Miriam Budiardjo (20 November 1923, Kediri – 8 January 2007, Jakarta) was an Indonesian political scientist and diplomat. Budiardjo was Deputy Chair of the Indonesian National Commission on Human Rights, and she has been credited with co-found ...

was the first woman to be an Indonesian diplomat, and became a co-founder and Dean of the Faculty of Social Science at the University of Indonesia

The University of Indonesia ( id, Universitas Indonesia, abbreviated as UI) is a public university in Depok, West Java and Salemba, Jakarta, Indonesia. It is one of the oldest tertiary-level educational institutions in Indonesia (known as the Dut ...

. When he was two years old, he and his family moved to the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

after his father received a five-year scholarship. After returning to Indonesia, Soedjatmoko continued his studies at a ''Europeesche Lagere School

Europeesche Lagere School (ELS) was a European elementary school system in what was then the Dutch East Indies during colonial rule. The schools were intended primarily for Europeans. The implementation of basic education at that time was diffe ...

'' (ELS) in Manado

Manado () is the capital City status in Indonesia, city of the Indonesian Provinces of Indonesia, province of North Sulawesi. It is the second largest city in Sulawesi after Makassar, with the 2020 Census giving a population of 451,916 distribu ...

, North Sulawesi

North Sulawesi ( id, Sulawesi Utara) is a province of Indonesia. It is located on the Minahasa Peninsula of Sulawesi, south of the Philippines and southeast of Sabah, Malaysia. It borders the Philippine province of Davao Occidental and Soccsks ...

.

Soedjatmoko later attended a '' Hogere Burgerschool'' in Surabaya

Surabaya ( jv, ꦱꦸꦫꦧꦪ or jv, ꦯꦹꦫꦨꦪ; ; ) is the capital city of the Provinces of Indonesia, Indonesian province of East Java and the List of Indonesian cities by population, second-largest city in Indonesia, after Jakarta. L ...

, where he graduated in 1940. The school introduced him to Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, and one of his teachers introduced him to European art

The art of Europe, or Western art, encompasses the history of art, history of visual art in Europe. European prehistoric art started as mobile Upper Paleolithic rock art, rock and cave painting and petroglyph art and was characteristic of the ...

; he later recalled that this introduction had allowed him to see Europeans as more than colonists. He then continued to medical school in Batavia

Batavia may refer to:

Historical places

* Batavia (region), a land inhabited by the Batavian people during the Roman Empire, today part of the Netherlands

* Batavia, Dutch East Indies, present-day Jakarta, the former capital of the Dutch East In ...

(modern day Jakarta

Jakarta (; , bew, Jakarte), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta ( id, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta) is the capital and largest city of Indonesia. Lying on the northwest coast of Java, the world's most populous island, Jakarta ...

). Upon seeing the slums of Jakarta, he was drawn to the issue of poverty, a subject with would later become an academic interest of his. However, during the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies

The Empire of Japan occupied the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) during World War II from March 1942 until after the end of the war in September 1945. It was one of the most crucial and important periods in modern Indonesian history.

In May ...

, in 1943, he was expelled from the city due to his relationship with Sutan Sjahrir

Sutan Sjahrir (5 March 1909 – 9 April 1966) was an Indonesian politician, and revolutionary independence leader, who served as the first Prime Minister of Indonesia, from 1945 until 1947. Previously, he was a key Indonesian nationalist organiz ...

– who had married Soedjatmoko's sister Siti Wahyunah – and participation in protests against the occupation.

After his expulsion, Soedjatmoko moved to Surakarta

Surakarta ( jv, ꦯꦸꦫꦏꦂꦠ), known colloquially as Solo ( jv, ꦱꦭ; ), is a city in Central Java, Indonesia. The 44 km2 (16.2 sq mi) city adjoins Karanganyar Regency and Boyolali Regency to the north, Karanganyar Regency and Sukoh ...

and studied Western history and political literature, which led to him developing an interest in socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

. Some figures which affected him besides Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

were Ortega y Gasset

Ortega is a Spanish surname. A baptismal record in 1570 records a ''de Ortega'' "from the village of Ortega". There were several villages of this name in Spain. The toponym derives from Latin ''urtica'', meaning "nettle".

Some of the Ortega spel ...

and Jan Romein

Jan Marius Romein (30 October 1893 – 16 July 1962) was a Dutch historian, journalist, literary scholar and professor of history at the University of Amsterdam. A Marxist and a student of Huizinga, Romein is remembered for his popularizing ...

. While in Surakarta he also worked at his father's hospital. After Indonesia proclaimed its independence, Soedjatmoko was asked to become Deputy Head of the Foreign Press Department in the Ministry of Information. In 1946, at the request of Prime Minister Sjahrir, he and two friends established a Dutch-language weekly, ''Het Inzicht'' (''Inside''), as a counter to the Dutch-sponsored ''Het Uίtzicht'' (''Outlook''). The next year, they launched a socialist-oriented journal, ''Siasat'' (''Tactics''), which was published weekly. During this period Soedjatmoko dropped the name Mangoendiningrat, as it reminded him of the feudal aspects of Indonesian culture.

Career

Time abroad

In 1947, Sjahrir sent Soedjatmoko to New York as a member of the Indonesian Republic's "observer" delegation to the United Nations (UN). The delegation travelled to theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

via the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

after a two-month stay in Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

; while in the Philippines, President Manuel Roxas

Manuel Acuña Roxas (born Manuel Roxas y Acuña; ; January 1, 1892 – April 15, 1948) was a Filipino lawyer and politician who served as the fifth president of the Philippines, who served from 1946 until his death due to heart attacks in 194 ...

guaranteed support of the nascent nation's case at the United Nations. Soedjatmoko stayed in Lake Success, New York

Lake Success is a village in the Town of North Hempstead in Nassau County, on the North Shore of Long Island, in New York. The population was 2,897 at the 2010 census.

The Incorporated Village of Lake Success was the temporary home of the United ...

, the temporary location of the UN, and participated in debates over international recognition of the new country. Towards the end of his stay in New York, Soedjatmoko enrolled at Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

's Littauer Center; as, at the time, he was still part of the UN delegation, he commuted between New York and Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

for seven months. After being released from the delegation, he spent most of a year at the center; for a period of three months, however, he was chargé d'affaires

A ''chargé d'affaires'' (), plural ''chargés d'affaires'', often shortened to ''chargé'' (French) and sometimes in colloquial English to ''charge-D'', is a diplomat who serves as an embassy's chief of mission in the absence of the ambassador ...

– the nation's first – at the Dutch East Indies desk of the Dutch embassy in London, serving in a temporary capacity while the Indonesian embassy was being established. In 1951, Soedjatmoko moved to Washington D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, Na ...

to establish the political desk at the Indonesian embassy there; he also became Alternate Permanent Representative of Indonesia at the UN. This busy schedule, demanding a commute between three cities, proved to be too much for him and he dropped out of the Littauer Center. In late 1951, he resigned from his positions and went to Europe for nine months, seeking political inspiration. In Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

, he met Milovan Djilas

Milovan Djilas (; , ; 12 June 1911 – 30 April 1995) was a Yugoslav communist politician, theorist and author. He was a key figure in the Partisan movement during World War II, as well as in the post-war government. A self-identified democrat ...

, who impressed him greatly.

Return home

Upon returning to Indonesia, Soedjatmoko once again became an editor of ''Siasat''. In 1952, he was one of the founders of Socialist Party daily ''Pedoman'' (''Guidance''); this was followed by a political journal, ''Konfrontasi'' (''Confrontation''). He also helped to establish the Pembangunan publishing house, which he directed until 1961. Soedjatmoko joined the

Upon returning to Indonesia, Soedjatmoko once again became an editor of ''Siasat''. In 1952, he was one of the founders of Socialist Party daily ''Pedoman'' (''Guidance''); this was followed by a political journal, ''Konfrontasi'' (''Confrontation''). He also helped to establish the Pembangunan publishing house, which he directed until 1961. Soedjatmoko joined the Indonesian Socialist Party

The Socialist Party of Indonesia ( id, Partai Sosialis Indonesia) was a political party in Indonesia from 1948 until 1960, when it was banned by President Sukarno.

Origins

In December 1945 Amir Sjarifoeddin's Socialist Party of Indonesia (Pars ...

(, or PSI) in 1955, and was elected as a member of Constitutional Assembly of Indonesia

The Constitutional Assembly ( id, Konstituante) was a body elected in 1955 to draw up a permanent constitution for the Republic of Indonesia. It sat between 10 November 1956 and 2 July 1959. It was dissolved by then President Sukarno in a decr ...

in the 1955 elections until the dissolution of the assembly in 1959. He served with the Indonesian delegation at the Bandung Conference

The first large-scale Asian–African or Afro–Asian Conference ( id, Konferensi Asia–Afrika)—also known as the Bandung Conference—was a meeting of Asian and African states, most of which were newly independent, which took place on 18–2 ...

in 1955. Later the same year, he founded the Indonesian Institute of World Affairs and became its Secretary General for four years. Soedjatmoko married Ratmini Gandasubrata in 1958. Together they had three daughters.

Towards the end of the 1950s, Soedjatmoko and President Sukarno

Sukarno). (; born Koesno Sosrodihardjo, ; 6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was an Indonesian statesman, orator, revolutionary, and nationalist who was the first president of Indonesia, serving from 1945 to 1967.

Sukarno was the leader of ...

, with whom he had had a warm working relationship, had a falling out over the president's increasingly authoritarian policies. In 1960 Soedjatmoko co-founded and headed the Democratic League, which attempted to promote democracy in the country; he also opposed Sukarno's Guided Democracy

Guided democracy, also called managed democracy, is a formally democratic government that functions as a ''de facto'' authoritarian government or in some cases, as an autocratic government. Such hybrid regimes are legitimized by elections tha ...

policy. When the effort failed, Soedjatmoko went to the US and took a position as guest lecturer at Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach an ...

. When he returned to Indonesia in 1962, he discovered that key members of the PSI had been arrested and the party banned; both ''Siasat'' and ''Pedoman'' were closed. To avoid trouble with the government, Soedjatmoko voluntarily left himself unemployed until 1965, when he became co-editor of ''An Introduction to Indonesian Historiography''.

Ambassadorship

After the failedcoup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

in 1965 and the replacement of Sukarno by Suharto

Suharto (; ; 8 June 1921 – 27 January 2008) was an Indonesian army officer and politician, who served as the second and the longest serving president of Indonesia. Widely regarded as a military dictator by international observers, Suharto ...

, Soedjatmoko returned to public service. He served as vice-chairman of the Indonesian delegation at the UN in 1966, becoming the delegation's adviser in 1967. Also in 1967, Soedjatmoko became adviser to foreign minister Adam Malik

Adam Malik Batubara (22 July 1917 – 5 September 1984), or more commonly referred to simply as Adam Malik, was an Indonesians, Indonesian politician, diplomat, and journalist, who served as the 3rd Vice President of Indonesia from 1978 until ...

, as well as a member of the International Institute for Strategic Studies

The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) is a British research institute or think tank in the area of international affairs. Since 1997, its headquarters have been Arundel House in London, England.

The 2017 Global Go To Think T ...

, a London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

-based think tank

A think tank, or policy institute, is a research institute that performs research and advocacy concerning topics such as social policy, political strategy, economics, military, technology, and culture. Most think tanks are non-governmenta ...

; the following year he became Indonesian ambassador to the United States, a position which he held until 1971. During his time as ambassador, Soedjatmoko received honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hon ...

s from several American universities, including Cedar Crest College

Cedar Crest College is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts Women's colleges in the United States, women's college in Allentown, Pennsylvania. At the start of the 2015-2016 Academic term, academic y ...

in 1969 and Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

in 1970. He also published another book, ''Southeast Asia Today and Tomorrow'' (1969). Soedjatmoko returned to Indonesia in 1971; upon his return he became Special Adviser on Social and Cultural Affairs to the Chairman of the National Development Planning Agency. That same year, he became a board member of the London-based International Institute for Environment and Development

International is an adjective (also used as a noun) meaning "between nations".

International may also refer to:

Music Albums

* ''International'' (Kevin Michael album), 2011

* ''International'' (New Order album), 2002

* ''International'' (The T ...

, a position which he held until 1976; he also joined the Club of Rome

The Club of Rome is a nonprofit, informal organization of intellectuals and business leaders whose goal is a critical discussion of pressing global issues. The Club of Rome was founded in 1968 at Accademia dei Lincei in Rome, Italy. It consists ...

.

In 1972 Soedjatmoko was selected to the board of trustees of the Ford Foundation

The Ford Foundation is an American private foundation with the stated goal of advancing human welfare. Created in 1936 by Edsel Ford and his father Henry Ford, it was originally funded by a US$25,000 gift from Edsel Ford. By 1947, after the death ...

, in which position he served 12 years; also in 1972 he became a governor of the Asian Institute of Management

The Asian Institute of Management (AIM) is an international management school and research institution. It is one of the few business schools in Asia to be internationally accredited with the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Busine ...

, a position which he held for two years. The following year he became a governor of the International Development Research Center

The International Development Research Centre (IDRC; french: Centre de recherches pour le développement international, ''CRDI'') is a Canadian federal Crown corporation that funds research and innovation within and alongside developing region ...

. In 1974, based on falsified documents, he was accused of planning the Malari incident of January 1974, in which students protested and eventually rioted during a state visit by Prime Minister of Japan Kakuei Tanaka

was a Japanese politician who served in the House of Representatives (Japan), House of Representatives from 1947 Japanese general election, 1947 to 1990 Japanese general election, 1990, and was Prime Minister of Japan from 1972 to 1974.

After ...

. Held for interrogation for two and a half weeks, Soedjatmoko was not allowed to leave Indonesia for two and a half years for his suspected involvement. In 1978 Soedjatmoko received the Ramon Magsaysay Award

The Ramon Magsaysay Award (Filipino: ''Gawad Ramon Magsaysay'') is an annual award established to perpetuate former Philippine President Ramon Magsaysay's example of integrity in governance, courageous service to the people, and pragmatic idealis ...

for International Understanding, often called Asia's Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

. The citation read, in part: Encouraging both Asians and outsiders to look more carefully at the village folkways they would modernize, odjatmokois fostering awareness of the human dimension essential to all development. .. s writings have added consequentially to the body of international thinking on what can be done to meet one of the greatest challenges of our time; how to make life more decent and satisfying for the poorest 40 percent in Southeastern and southern Asia.In response, Soedjatmoko said he felt "humbled, because of isawareness that whatever small contribution emay have made is dwarfed by the magnitude of the problem of persistent poverty and human suffering in Asia, and by the realization of how much still remains to be done."

Later life and death

In 1980 Soedjatmoko moved toTokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.468 ...

, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

. In September of that year he began service as the rector of the United Nations University

The (UNU) is the think tank and academic arm of the United Nations. Headquartered in Shibuya, Tokyo, Japan, with diplomatic status as a UN institution, its mission is to help resolve global issues related to human development and welfare thro ...

, replacing James M. Hester; he remained in that position until 1987. In Japan he published two further books, ''The Primacy of Freedom in Development'' and ''Development and Freedom''. He received the Asia Society Award in 1985, and the Universities Field Staff International Award for Distinguished Service to the Advancement of International Understanding the following year. Soedjatmoko died of cardiac arrest on 21 December 1989 when he was lecturing at Muhammadiyah University of Yogyakarta

Muhammadiyah University of Yogyakarta ( id, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta; abbreviated as UMY) is a private university in Special Region of Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta under affiliation of Muhammadiyah, the second largest Islamic organization in ...

.

References

Citations

Sources

* * {{Authority control 1922 births 1989 deaths People from Sawahlunto Ambassadors of Indonesia to the United States Ramon Magsaysay Award winners Members of the Constitutional Assembly of Indonesia United Nations University staff Indonesian Muslims 20th-century Indonesian historians Asian Institute of Management people