History

Early history

From 1901 to the onset of World War I, the Socialist Party had numerous elected officials throughout the United States. There were two Socialist members of Congress, Meyer London of New York City and

From 1901 to the onset of World War I, the Socialist Party had numerous elected officials throughout the United States. There were two Socialist members of Congress, Meyer London of New York City and  The party's opposition to World War I caused a sharp decline in membership. It suffered from the United States Postmaster General, Postmaster General's decision to refuse to allow the delivery of party newspapers and periodicals via the U.S. mail, severely disrupting the party's activity, particularly in rural areas. Radicals moved further left into the IWW or the

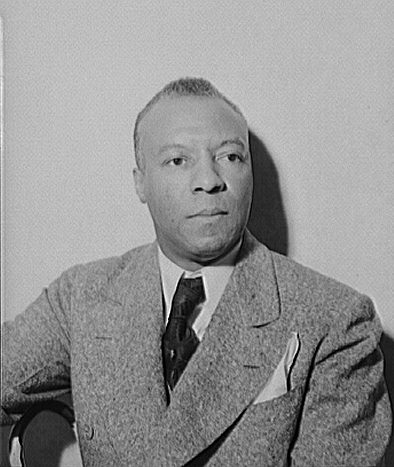

The party's opposition to World War I caused a sharp decline in membership. It suffered from the United States Postmaster General, Postmaster General's decision to refuse to allow the delivery of party newspapers and periodicals via the U.S. mail, severely disrupting the party's activity, particularly in rural areas. Radicals moved further left into the IWW or the Victor Berger in Milwaukee

According to historian Sally Miller,Split of the Left Wing Section

In January 1919, Vladimir Lenin invited the IWW and the radical wing of the Socialist Party to join in the founding of the Communist Third International, the Comintern. The Left Wing Section of the Socialist Party emerged as an organized faction early that year, building its organization around a lengthy Left Wing Manifesto by Louis C. Fraina. This effort to organize in order to "win the Socialist Party for the Left Wing" was staunchly resisted by the "Regulars", who controlled a big majority of the seats of the Socialist Party's governing NEC. When it seemed certain that the 1919 party elections for a new NEC had been dominated by the Left Wing, the sitting NEC, citing voting irregularities, refused to tally the votes, declared the entire election invalid and in May 1919 suspended the party's Russian, Latvian, Ukrainian, Polish, South Slavic and Hungarian language federations, in addition to Michigan's entire state organization. In future weeks, Massachusetts's and Ohio's state organizations were similarly disfranchised and "reorganized" by the NEC, while in New York and Pennsylvania the "Regular" State Executive Committees undertook reorganization of Left Wing branches and locals on a case-by-case basis. In June 1919, the Left Wing Section held a conference in New York City to discuss its organizational plans. The group found itself deeply divided, with one section, led by NEC members Alfred Wagenknecht and L. E. Katterfeld and including famed radical journalist John Reed (journalist), John Reed favoring a continued effort to gain control of the SPA at its forthcoming Emergency National Convention in Chicago, to be held at the end of August, while another section, headed by the Russian Socialist Federation of Alexander Stoklitsky and Nicholas I. Hourwich, Nicholas Hourwich and the Socialist Party of Michigan seeking to wash its hands of the Socialist Party and immediately move to establish a new Communist Party USA#History, Communist Party of America. Eventually, this latter Federation-dominated group was joined by important Left Wingers Charles Ruthenberg, C. E. Ruthenberg and Louis Fraina, a depletion of Left Wing forces that made the result of the 1919 Socialist Convention a foregone conclusion.

In June 1919, the Left Wing Section held a conference in New York City to discuss its organizational plans. The group found itself deeply divided, with one section, led by NEC members Alfred Wagenknecht and L. E. Katterfeld and including famed radical journalist John Reed (journalist), John Reed favoring a continued effort to gain control of the SPA at its forthcoming Emergency National Convention in Chicago, to be held at the end of August, while another section, headed by the Russian Socialist Federation of Alexander Stoklitsky and Nicholas I. Hourwich, Nicholas Hourwich and the Socialist Party of Michigan seeking to wash its hands of the Socialist Party and immediately move to establish a new Communist Party USA#History, Communist Party of America. Eventually, this latter Federation-dominated group was joined by important Left Wingers Charles Ruthenberg, C. E. Ruthenberg and Louis Fraina, a depletion of Left Wing forces that made the result of the 1919 Socialist Convention a foregone conclusion.

Regardless, Wagenknecht's and Reed's plans to fight it out at the 1919 Emergency National Convention continued apace. With the most radical state organizations effectively purged by the Regulars (Massachusetts, Minnesota) or unable to participate (Ohio, Michigan) and the Left Wing language federations suspended, a big majority of the hastily elected delegates to the gathering were controlled by the Executive Secretary Adolph Germer and the Regulars. A group of Left Wingers without delegate credentials, including Reed and his sidekick Benjamin Gitlow, made an effort to occupy chairs on the convention floor before the gathering was called into order. The incumbents were unable to block the Left Wingers at the door, but soon called to their aid the already present police, who obligingly expelled the boisterous radicals from the hall. With the Credentials Committee firmly in the hands of the Regulars from the outset, the gathering's outcome was no longer in doubt and most of the remaining Left Wing delegates departed, to meet with other co-thinkers downstairs in a previously reserved room in a parallel convention. It was this gathering that established itself as the Communist Labor Party of America, Communist Labor Party on August 31, 1919.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in Chicago, the Federations and Michiganders and their supporters established the Communist Party of America at a convention gaveled to order on September 1, 1919. Unity between these two communist organizations was a lengthy and complicated process, formally taking place at a secret convention held at the Overlook Mountain House hotel near Woodstock, New York, in May 1921 with the establishment of a new unified Communist Party of America. A Left Wing loyal to the Communist International remained in the Socialist Party through 1921, continuing the fight to bring the Socialist Party into the ranks of the Comintern. This group, which opposed the underground secret organizations the Communist Parties had become, included noted party journalist J. Louis Engdahl and William F. Kruse, William Kruse, head of the party's youth affiliate, the Young People's Socialist League (1907), Young People's Socialist League, as well as a significant segment of the Socialist Party's Chicago organization. These left-wing dissidents continued to make themselves heard until their departure from the party after the 1921 convention.

Regardless, Wagenknecht's and Reed's plans to fight it out at the 1919 Emergency National Convention continued apace. With the most radical state organizations effectively purged by the Regulars (Massachusetts, Minnesota) or unable to participate (Ohio, Michigan) and the Left Wing language federations suspended, a big majority of the hastily elected delegates to the gathering were controlled by the Executive Secretary Adolph Germer and the Regulars. A group of Left Wingers without delegate credentials, including Reed and his sidekick Benjamin Gitlow, made an effort to occupy chairs on the convention floor before the gathering was called into order. The incumbents were unable to block the Left Wingers at the door, but soon called to their aid the already present police, who obligingly expelled the boisterous radicals from the hall. With the Credentials Committee firmly in the hands of the Regulars from the outset, the gathering's outcome was no longer in doubt and most of the remaining Left Wing delegates departed, to meet with other co-thinkers downstairs in a previously reserved room in a parallel convention. It was this gathering that established itself as the Communist Labor Party of America, Communist Labor Party on August 31, 1919.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in Chicago, the Federations and Michiganders and their supporters established the Communist Party of America at a convention gaveled to order on September 1, 1919. Unity between these two communist organizations was a lengthy and complicated process, formally taking place at a secret convention held at the Overlook Mountain House hotel near Woodstock, New York, in May 1921 with the establishment of a new unified Communist Party of America. A Left Wing loyal to the Communist International remained in the Socialist Party through 1921, continuing the fight to bring the Socialist Party into the ranks of the Comintern. This group, which opposed the underground secret organizations the Communist Parties had become, included noted party journalist J. Louis Engdahl and William F. Kruse, William Kruse, head of the party's youth affiliate, the Young People's Socialist League (1907), Young People's Socialist League, as well as a significant segment of the Socialist Party's Chicago organization. These left-wing dissidents continued to make themselves heard until their departure from the party after the 1921 convention.

Expulsion of Socialists from the New York Assembly

On January 7, 1920, less than a week after the Palmer Raids had swept and stunned the country, the 143rd New York State Legislature#State Assembly, New York Assembly was called to order. The majority Republicans easily elected their candidate for the Speaker, Thaddeus C. Sweet and after opening day formalities the body took a brief recess. Back in session, Sweet declared: "The Chair directs the Sergeant-at-Arms to present before the Bar (law), bar of the House Sam DeWitt, Samuel A. DeWitt, Samuel Orr, Louis Waldman, Charles Solomon (politician), Charles Solomon, and August Claessens", the Assembly's five Socialist members. Sweet attacked the five, declaring they had been "elected on a platform that is absolutely inimical to the best interests of the state of New York and the United States". The Socialist Party, Sweet said, was "not truly a political party", but rather "a membership organization admitting within its ranks aliens, enemy aliens, and minors". The party had denounced America's participation in the European war and had lent aid and comfort to Ludwig Martens, the "self-styled Soviet Ambassador and alien, who entered this country as a German in 1916". It had supported the revolutionaries in German Revolution of 1918–1919, Germany, Austria and Hungarian Soviet Republic, Hungary, Sweet continued; and consorted with international Socialist parties close to the Communist International. Sweet concluded:

Sweet attacked the five, declaring they had been "elected on a platform that is absolutely inimical to the best interests of the state of New York and the United States". The Socialist Party, Sweet said, was "not truly a political party", but rather "a membership organization admitting within its ranks aliens, enemy aliens, and minors". The party had denounced America's participation in the European war and had lent aid and comfort to Ludwig Martens, the "self-styled Soviet Ambassador and alien, who entered this country as a German in 1916". It had supported the revolutionaries in German Revolution of 1918–1919, Germany, Austria and Hungarian Soviet Republic, Hungary, Sweet continued; and consorted with international Socialist parties close to the Communist International. Sweet concluded:

It is every citizen's right to his day in court. If this house should adopt a resolution declaring your seat herein vacant, pending a hearing before a tribunal of this house, you will be given an opportunity to appear before such tribunal to prove your right to a seat in this legislative body, and upon the result of such hearing and the findings of the Assembly tribunal, your right to participate in the actions of this body will be determined.The Assembly suspended the quintet by a vote of 140 to 6, with one Democrat supporting the Socialists. Civil libertarians and concerned citizens raised their voices to aid the suspended Socialists and protest percolated throughout the press. The principal argument was that the expulsion of elected members of minority parties by majority parties from their councils set a dangerous precedent in a democracy. The battle culminated in a highly publicized trial in the Assembly, which dominated the body's activity from its opening on January 20, 1920, until its conclusion on March 11. Socialist Party leader and former 1917 New York City mayoral candidate Morris Hillquit served as chief counsel for the suspended Socialists, aided by party founder and future Socialist vice-presidential candidate Seymour Stedman. At the trial, Hillquit charged that Sweet had made a "specific, concrete, definite, affirmative declaration of guilt" of the five Assemblymen before they were ever charged with any offense. It was also Sweet who appointed the members of the Judiciary Committee to which the matter was referred. "Thus the accuser selects his own judges", Hillquit declared. Hillquit sought to remove for reasons of bias any members of the Judiciary Committee who had taken part in the activities of the Lusk Committee, the New York State Senate's anti-radicalism committee. He particularly challenged the presence of Assemblyman Louis A. Cuvillier, who had stated on the floor of the house the previous night words to the effect that "if the five accused Assemblymen are found guilty, they ought not to be expelled, but taken out and shot". The Assembly voted overwhelmingly for expulsion on April 1, 1920. On September 16, 1920, a special election was held to fill the five seats vacated by the Assembly, with each of the five expelled Socialists running for reelection against a "fusion" candidate representing the combined Republican and Democratic parties. All five Socialists were returned to office. Three of the five, Waldman, Claessens and Solomon, were again denied their seats after a contentious debate by votes of 90 to 45 on September 21, 1920. Orr and DeWitt, deemed less culpable than their peers by the earlier findings of the Judiciary Committee, were seated by votes of 87 to 48. In solidarity with their ousted colleagues, the pair refused to take their seats."Socialists Again Ousted by New York Assembly," ''Minnesota Daily Star,'' September 22, 1920, p. 1. After the five seats were again vacated, Hillquit expressed his disappointment at the Assembly's "unconstitutional action". But, he continued, "it will draw the issues clearer between the united Republican and Democratic parties representing arbitrary lawlessness, and the Socialist Party, which stood and stands for democratic and representative government". The legislature attempted to prevent the election and seating of Socialists in the future by passing laws designed to exclude the Socialist Party from recognition as a political party and to alter the legislature's oath-taking procedures so that elected members could be excluded before being sworn. Governor Al Smith vetoed the legislation.

Quest for a mass Farmer–Labor Party

In the first half of 1919, the Socialist Party had over 100,000 dues-paying members, and by the second half of 1921 it had been shattered. Fewer than 14,000 members remained in party ranks, with the departure of the large, well-funded Finnish Socialist Federation adding to the malaise. In September 1921, the NEC determined that the time had come to end the party's historic aversion to fusion with other political organizations and issue an appeal declaring that the "forces of every progressive, liberal, and radical organization of the workers must be mobilized" to repel conservative assaults and "advance the industrial and political power of the working class". This desire for common action seems to have been shared by various unions, as late in 1921 a call was issued in the name of the country's 16 major railway labor unions seeking a Conference for Progressive Political Action (CPPA). The CPPA was originally intended to be an umbrella organization bringing together various elements of the farmer and labor movement together in a common program. Invitations to the group's founding conference were issued to members of a wide variety of "progressive" organizations of widely varied perspectives. As a result, from its inception the heterogeneous body was unable to agree on a program or a declaration of principles, let alone congeal into a new political party. The Socialist Party was an enthusiastic supporter of the CPPA and the group dominated its thinking from the start of 1922 through the first quarter of 1925. In this period of organizational weakness, the party sought to forge lasting ties with the existing trade union movement, leading in short order to a mass labor party in the United States on the British model. A first National Conference of the CPPA was held in Chicago in February 1922, attended by 124 delegates representing a broad spectrum of labor, farmer and political organizations. The gathering passed an "Address to the American People" stating its criticism of existing conditions and formally proposing an amorphous plan of action validating the status quo ante: the labor unions on the group's right wing to endorse labor-friendly candidates of the Democratic Party, the Socialists and Farmer-Labor Party adherents on the group's left wing to conduct their own independent campaigns. From the Socialist Party's perspective, perhaps the most important thing the CPPA did at its first National Conference was agree to meet again. The party leadership understood the process of building an independent Third party (United States), third party that could count on the allegiance of the country's trade union leadership would be a protracted process and the mere fact of "agreement to disagree" but nevertheless meeting again was regarded as a step forward. The communist movement also sought to pursue the strategy of bursting from its isolation by forming a mass Farmer-Labor Party. Finally emerged from its underground existence in 1922, the Communists, through their "legal political party", the Workers Party of America, sent four delegates to the CPPA's December 1922 gathering. But after protracted debate, the Credentials Committee strongly objected to the participation of Communist representatives in its proceedings and issued a recommendation that Workers Party's representatives and youth organization not be seated. The Socialist Party's delegates strongly supported excluding the Communists and acted accordingly, even though the two organizations shared a vision of a party akin to the British Labour Party in which constituent political groups jointly participated while retaining their independent existence. The fissure between the organizations thus widened. As with the first conference, the 2nd Conference of the CPPA split over the all-important issue of an independent political party, with a proposal by five delegates of the Farmer-Labor Party calling for "independent political action by the agricultural and industrial workers through a party of their own" defeated by a vote of 52 to 64. A majority report declaring against an independent political party was instead adopted. This defeat of the bid for an independent political party cost the CPPA one its major component organizations, with the Farmer-Labor Party delegation announcing that its group would no longer affiliate with the CPPA after the convention. Although the Socialists did not realize it at the time, the chances that the organization would ever be transformed into an authentic mass Farmer-Labor party like British Labour were greatly lessened by the FLP's departure. The Socialists remained optimistic, and the May 1923 National Convention of the Socialist Party voted after lengthy debate to retain its affiliation with the CPPA and to continue its work for an independent political party from within that group. The May 20 vote in favor of maintaining affiliation with the CPPA was 38–12. Failing a mass farmer-labor party from the CPPA, the Socialists sought at least a powerful presidential nominee to run in opposition to the old parties. A 3rd National Conference of the CPPA was held in St. Louis, Missouri, on February 11 and 12, 1924, a gathering that punted on the issue of committing itself to the 1924 presidential campaign, deciding instead to "immediately issue a call for a convention of workers, farmers, and progressives for the purpose of taking action on nomination of candidates for the offices of President and Vice President of the United States, and on other questions that may come before the convention". The decisive moment finally came on July 4, 1924, a date that was not selected accidentally. The 1st National Convention of the CPPA was assembled in Cleveland at the city auditorium, which was packed with close to 600 delegates representing international unions, state federations of labor, branches of cooperative societies, state branches and national officers of the Socialist, Farmer-Labor and Progressive Parties as well as the Committee of 48, state and national affiliates of the Women's Committee on Political Action and sundry individuals. Very few farmers were in attendance. It was around this time that the Socialists began actively participating in discussions about democratic principles as much as Marxism, Marxist ones. By 1924, they supported the Progressive Party (United States, 1924–34), Progressive Party ticket, which pushed for the reform of the The National Committee had previously requested that Wisconsin Senator Robert M. La Follette run for president. The Cleveland Convention was addressed by La Follette's son, Robert M. La Follette Jr., who read a message from his father accepting the call and declaring that the time had come "for a militant political movement independent of the two old party organizations". But La Follette declined to lead a third party, seeking to protect those progressives elected nominally as Republicans and Democrats. He said that the primary issue of the 1924 campaign was breaking the "combined power of the private monopoly system over the political and economic life of the American people". After the November election a new party might well be established, La Follette said, that might unite all progressives.

The Socialist Party enthusiastically supported La Follette's independent candidacy, declining to run its own candidate in 1924. Although La Follette garnered five million votes, his campaign failed to seriously challenge the old parties' hegemony and was regarded by the unions as a disappointing failure.

After the election, the governing National Committee of the CPPA met in Washington, D.C. While the body had a mandate from the July convention to issue a call for a convention to organize a new political party, the representatives of the critical railway unions, with the exception of William H. Johnston of the Machinists, were united in opposition to the idea. The railroad unions instead proposed a motion not to hold the 1925 organizational convention. This proposal was defeated by a vote of 30 to 13. After their defeat on this question, the railroaders on National Committee members withdrew from the meeting, announcing that they would await further instructions from their respective organizations with regard to future participation.DeLeon and Fine (eds.), ''The American Labor Year Book, 1925,'' p. 131. The loss of the very unions that had brought about the CPPA spelled its demise.

The National Committee nonetheless scheduled a convention to decide on the formation of a new political party for February 21, 1925, to be held in Chicago. ''Labor,'' the official organ of the railway unions, did nothing to promote this 2nd Convention of the CPPA, stating that since the executives of the various unions had taken no stance on the matter, it would be up to subordinate sections to consider sending delegates themselves.

The February 1925 convention found its task virtually insurmountable as the heterogeneous organization had split over the fundamental question of realignment of the major parties via the primary elections process as opposed to establishment of a new competitive political party. The railway unions, whose efforts who had originally brought the CPPA into existence, were fairly solidly united against the Third Party tactic, instead favoring continuation of the CPPA as a sort of pressure group for progressive change within the Democratic and Republican parties.

L. E. Sheppard, president of the Order of Railway Conductors of America, presented a resolution calling for a continuation of the CPPA on non-partisan lines as a political pressure group. This proposal was met by an amendment by Morris Hillquit of the Socialist Party, who called the five million votes cast for La Follette an encouraging beginning and urged action for establishment of an American Labor Party on the British model—in which constituent groups retained their organizational autonomy within the larger umbrella organization. A third proposal was made by J.A.H. Hopkins of the Committee of Forty-Eight, which called for establishment of a Progressive Party built around individual enrollments. No vote was ever taken by the convention on any of the three proposals mooted. Instead, after some debate the convention was unanimously adjourned ''Adjournment sine die, sine die''—bringing an abrupt end to the Conference for Progressive Political Action.

Debs addressed a "mass meeting" including delegates of the convention in a keynote address delivered at the Lexington Hotel early in the afternoon of February 21. After his speech, those delegates favoring establishment of a new political party reconvened, with the opponents of an independent political party departing. The reconvened Founding Convention found itself split between adherents of a non-class Progressive Party based upon individual memberships as opposed to the Socialists' conception of a class-conscious Labor Party employing "direct affiliation" of "organizations of workers and farmers and of progressive political and educational groups who fully accept its program and principles". After extensive debate, the Socialist counterproposal was defeated by a vote of 93 to 64. The trade unions it coveted gone, the farmers nonexistent, the Socialist Party exited the convention and abandoned the strategy of establishing a new mass party through the CPPA. The remaining liberals formed a Progressive Party that survived for a short time in a limited number of states throughout the 1920s.

The National Committee had previously requested that Wisconsin Senator Robert M. La Follette run for president. The Cleveland Convention was addressed by La Follette's son, Robert M. La Follette Jr., who read a message from his father accepting the call and declaring that the time had come "for a militant political movement independent of the two old party organizations". But La Follette declined to lead a third party, seeking to protect those progressives elected nominally as Republicans and Democrats. He said that the primary issue of the 1924 campaign was breaking the "combined power of the private monopoly system over the political and economic life of the American people". After the November election a new party might well be established, La Follette said, that might unite all progressives.

The Socialist Party enthusiastically supported La Follette's independent candidacy, declining to run its own candidate in 1924. Although La Follette garnered five million votes, his campaign failed to seriously challenge the old parties' hegemony and was regarded by the unions as a disappointing failure.

After the election, the governing National Committee of the CPPA met in Washington, D.C. While the body had a mandate from the July convention to issue a call for a convention to organize a new political party, the representatives of the critical railway unions, with the exception of William H. Johnston of the Machinists, were united in opposition to the idea. The railroad unions instead proposed a motion not to hold the 1925 organizational convention. This proposal was defeated by a vote of 30 to 13. After their defeat on this question, the railroaders on National Committee members withdrew from the meeting, announcing that they would await further instructions from their respective organizations with regard to future participation.DeLeon and Fine (eds.), ''The American Labor Year Book, 1925,'' p. 131. The loss of the very unions that had brought about the CPPA spelled its demise.

The National Committee nonetheless scheduled a convention to decide on the formation of a new political party for February 21, 1925, to be held in Chicago. ''Labor,'' the official organ of the railway unions, did nothing to promote this 2nd Convention of the CPPA, stating that since the executives of the various unions had taken no stance on the matter, it would be up to subordinate sections to consider sending delegates themselves.

The February 1925 convention found its task virtually insurmountable as the heterogeneous organization had split over the fundamental question of realignment of the major parties via the primary elections process as opposed to establishment of a new competitive political party. The railway unions, whose efforts who had originally brought the CPPA into existence, were fairly solidly united against the Third Party tactic, instead favoring continuation of the CPPA as a sort of pressure group for progressive change within the Democratic and Republican parties.

L. E. Sheppard, president of the Order of Railway Conductors of America, presented a resolution calling for a continuation of the CPPA on non-partisan lines as a political pressure group. This proposal was met by an amendment by Morris Hillquit of the Socialist Party, who called the five million votes cast for La Follette an encouraging beginning and urged action for establishment of an American Labor Party on the British model—in which constituent groups retained their organizational autonomy within the larger umbrella organization. A third proposal was made by J.A.H. Hopkins of the Committee of Forty-Eight, which called for establishment of a Progressive Party built around individual enrollments. No vote was ever taken by the convention on any of the three proposals mooted. Instead, after some debate the convention was unanimously adjourned ''Adjournment sine die, sine die''—bringing an abrupt end to the Conference for Progressive Political Action.

Debs addressed a "mass meeting" including delegates of the convention in a keynote address delivered at the Lexington Hotel early in the afternoon of February 21. After his speech, those delegates favoring establishment of a new political party reconvened, with the opponents of an independent political party departing. The reconvened Founding Convention found itself split between adherents of a non-class Progressive Party based upon individual memberships as opposed to the Socialists' conception of a class-conscious Labor Party employing "direct affiliation" of "organizations of workers and farmers and of progressive political and educational groups who fully accept its program and principles". After extensive debate, the Socialist counterproposal was defeated by a vote of 93 to 64. The trade unions it coveted gone, the farmers nonexistent, the Socialist Party exited the convention and abandoned the strategy of establishing a new mass party through the CPPA. The remaining liberals formed a Progressive Party that survived for a short time in a limited number of states throughout the 1920s.

Left turn and split of the Old Guard

In 1928, the Socialist Party returned as an independent electoral entity under the leadership of Norman Thomas, a radical Protestant minister from New York City. This reentry into the electoral fray behind Thomas fueled major growth of the party during the first years of Great Depression, primarily among youth. A skilled orator and advocate of step-by-step solution of social problems, Thomas had excellent access to churches, colleges and civic institutions. He also had, as New York social democrat Louis Waldman later noted, "those qualities of mind and character which appealed to the intelligent and educated young people of the country and which drew them into the ranks of the party in unprecedented numbers". The 1928 convention voted to reduce membership dues to just $1 per year, with only half that sum going to the use of the National Office and the balance retained by state and local organizations. This level of funding proved insufficient for anything beyond the bare minimum of operations by the National Office in Chicago—no official party publication was made available to the members of the organization, with several privately held socialist newspapers fulfilling the function as fonts of party information. The dues rate cut did prove helpful in reducing the party's membership slide. After nearly a decade of steady decline, the Socialist Party again began to grow, advancing from a low of under 8,000 dues payers in 1928 to a membership of almost 17,000 by 1932. But this growth came at a price, as deep factional divisions developed between the youthful newcomers (radicalized and drawn to militant Marxism by the world economic crisis) and the "Old Guard" headed by Morris Hillquit, James Oneal and Waldman. The generational battle first erupted at the May 1932 Milwaukee Convention. Participant Anna Bercowitz noted four primary factions at this gathering, i.e. an Old Guard defending the current course of the party and the position of Hillquit, practical Socialists of the Milwaukee type, the young Marxist Militant faction, Militants and liberal pacifist Thomasites such as Devere Allen who followed Thomas's lead.The groups which represented the so-called 'New Blood' at the convention, the Militants and the Liberals and which at this convention merged for the sole purpose of deposing the present leadership [of the party] had little in common. Many members of the most aggressive, although numerically weakest of these groups, the Militants, had little in common with the so-called Thomasites. ... And as for the so-called Mid-western group, although they cast their vote with the opposition, on fundamentals they too are opposed to much of the liberalizing tendencies manifest in the party in recent years. Yet they voted, contrary to their usual procedure in their respective communities, with the opposition. That trades had been made there can be no doubt, and that some groups had been used as innocent dupes can also hardly be doubted...Hillquit was challenged at the 1932 convention by Daniel Hoan of Milwaukee, with the Militants and the Thomas group voting for Hoan with the Midwesterners. Hillquit was reelected National Chairman by a vote of 105–86, representing paid memberships of 7526 to 6984. Six members of the newly elected NEC were adherents of the Hillquit-Old Guard faction. It is clear that to some large extent the controversy between the young newcomers of the Militant faction and that of the so-called Old Guard can be reduced to this struggle for practical control of the party apparatus. Historian Frank Warren notes that "one cannot understand the Old Guard's actions unless one recognizes its intense desire to maintain its place in the party hierarchy; the drives of the young were a threat to the power of the New York Old Guard." He also adds that "clearly one would falsely idealize the Militants if one failed to recognize that their ambitions were not always selfless". In addition to the raw struggle for control of the party apparatus, there was also a divergence of visions about the role of the Socialist Party in the then-current crisis of capitalism, with mass unemployment at home and the growth of fascism and militarism abroad. The alternative vision of the Militants would be expressed at the subsequent convention of the party held in Detroit in June 1934, at which it was Thomas and his tactical allies of the Militant faction who emerged triumphant. It was this gathering that adopted a new 1934 Declaration of Principles, Declaration of Principles that inflamed the Old Guard faction on a number of different levels. The ideological differences between the radical pacifist Thomas and his allies of the Militant faction on the one hand and the Old Guard faction on the other have been succinctly summarized as follows:

Fundamentally there is much more in common between the Militants and the so-called 'Old Guard' than between the Militants and the [religious pacifist] Thomasites and surely than between the frank practical 'mid-western' type of Socialists, yet when it was a question of vote on the Russian resolution, on the TU [Trade Union] resolution and on the question of the National Chairman and the Executive Committee votes were not cast on the basis of principles but apparently on the basis of 'trades'. The real difference between the Militants and the 'Old Guard' seems to be based on lack of sufficient activity and on tempo rather than on principle.

The Old Guard was convinced that the 1934 Declaration of Principles was an open declaration in favor of armed insurrection; Thomas believed it was a necessary statement to indicate that Socialists would not lie down in the face of fascism. The Old Guard believed that the anti-war sections of the Declaration of Principles placed the party under the threat of legal prosecution for advocating unlawful actions to oppose war; again Thomas believed that a strong statement was necessary to put capitalism on warning that if it engaged in imperialist war there would be opposition. The Old Guard believed that a united front with the Communists was immoral and would be disastrous for the Socialists, that even limited united action on specific causes should be banned, and even that exploratory discussions about a united front were going too far. Thomas opposed a united front on a general level, including any joint actions in political contests, but he thought that carefully planned united action on specific cases could, and should, take place. And he believed that it was worth while to conduct exploratory talks, even though he felt they would likely lead to nothing. The Old Guard felt that the Socialists' invitation to unaffiliated radicals and the Party's acceptance of former Communists, Lovestoneites, and Trotskyists was turning the party away from democratic socialism and to Communism. Thomas, though he disagreed with the ideology of these anti-Stalinist Communists, was willing to try to work with a party that included them, if they were willing to accept party discipline and not try to take over the Party. The Old Guard considered the Revolutionary Policy Committee, a far-left group within the Socialist Party, a Communist and anarchist group that had no place in a democratic socialist party. Thomas disagreed with the 'romantic revolutionists' in the Revolutionary Policy Committee (as he disagreed with the 'romantic parliamentarians' of the Old Guard), but still felt it was useful to try to salvage some of the enthusiasm and dedication that went into the Revolutionary Policy Committee by permitting its members to remain in the Party if, again, they followed party policy and party discipline.In addition to the generational and ideological differences between the young Militant faction and the Old Guard and their divergence over tempo of activity and party personnel was great disagreement about matters of symbolism and style. Many of the young radicals dressed and acted in marked contrast to their staid, buttoned-down elders, as New York Old Guard leader Louis Waldman recounted in a 1944 memoir:

Symptoms of a new and dangerous spirit among the Socialist youth began to become manifest on all sides. The youngsters appeared at meetings of the party in blue shirts and red ties. At first this attracted no special attention, for oddity in dress is no novelty among radicals. But gradually their number increased and we now could see that this was a uniform. The Socialist youth of America, like the fascist youth in Europe, had succumbed to the shirt mania.After its loss on the floor of the Detroit Convention, the Old Guard took its case to the rank and file of the party, who had been called upon to either approve or defeat the new Declaration of Principles in a referendum. A Committee for the Preservation of the Socialist Party was established and an agitational pamphlet published. New York State Assemblyman Charles Solomon was the author of the group's first polemical piece, ''Detroit and the Party'', urging defeat of the 1934 Declaration of Principles by the membership at referendum''.'' In this pamphlet, he decried the Detroit Declaration of Principles as "reckless", observing pointedly that "furious phrases cannot take the place of organized mass power". Solomon noted that over "the past three or four years" there had arisen "certain definite groups" in the ranks of the Socialist Party. He continued:

The shirt tendency was followed by the salute mania. In Europe, the Nazi salute was the outstretched arm; here in America the United Front was symbolized by the adoption of the Communist clenched fist salute. This greeting, a raised arm at a slightly different angle from the Nazi or Communist salute, now became routine at all our meetings. [...] Some of the older members of the party were truly horrified at this totalitarian tendency, but others couldn't resist the trend and fell into line. Among these, I painfully record, was Norman Thomas.

Along with the blue shirts, the red ties, the clenched fists, the raised arm salute, came the banners, the slogans, the demonstrations; all the trappings that make for totalitarian, unthinking mass fervor. These now became regular features at party gatherings. I can still recall the howl of triumph that rose from these young people at one of our meetings when for the first time Norman Thomas returned the clenched fist salute to them. As I stood at his side, my arms deliberately folded to indicate that I would have no part of this, their cheers for Thomas rose to almost uncontrollable frenzy.

The Declaration does not stand by itself, in a vacuum, as it were. Important as it is, it does not alone account for the vital struggle that is now being waged in the party. It represents the culminating point of a deep seated antagonism. It is like the straw that breaks or threatens to break the camel's back. The Declaration of Principles has brought to the surface divergences which are deep, antagonisms which make of our party not a coherent political organization working harmoniously for a common objective but a battle ground of internecine strife.Solomon charged that the "so-called 'left was "making its position clear" with the Declaration of Principles. "There was no mistaking the flag it had unfurled", he declared; "[i]t was the banner of thinly veiled communism". While he declared that "the Declaration of Principles must be decisively rejected in the referendum", he nevertheless strongly hinted that a factional split was in the offing. Merely defeating the proposed Declaration of Principles was "not enough"; he concluded that the "Socialist Party must be made safe for Socialism, for social democracy". ''American Socialist Quarterly'' editor Haim Kantorovitch made the case for the Militant faction in a pamphlet urging approval of the Declaration of Principles at referendum:

The declaration of principles does not call for insurrection or violence. It simply states that if capitalism should collapse, the Socialist Party will not shrink from the responsibility of taking power. In case of a collapse of capitalism, if the socialists refuse to take power, the fascists will. To say beforehand that in time of a general collapse of capitalism...the socialists will not dare take power before they have a clear mandate from the majority through a democratic vote, is the same as saying that in case of a general collapse of capitalism the Socialist Party will voluntarily, in the name of democracy, turn over the power to the fascists or other reactionary elements, and continue their democratic propaganda from concentration camps.The membership of the Socialist Party approved the 1934 Declaration of Principles in its referendum, a victory that moved the Old Guard toward the exits—although factional fighting continued into 1936. In 1936, the leaders of the Old Guard formed a new rival organization to the Socialist Party, the Social Democratic Federation (United States), Social Democratic Federation, and somewhat reluctantly endorsed Franklin D. Roosevelt for president in that year's election. They also worked to establish the American Labor Party (ALP), a labor-oriented umbrella organization that included both socialist and non-socialist elements, both putting forward its own candidates and endorsing those of the Democratic Party (U.S.), Democratic and Republican Party (U.S.), Republican parties.

End Poverty in California movement

The novelist Upton Sinclair had long been associated with the Socialist Party in California. He was twice its candidate for Congress and its nominee for governor in 1930, but won fewer than 50,000 votes. In 1934, Sinclair ran in the Democratic primary for governor and astonished everyone by winning on a promise of radical socialist economic reforms he dubbed End Poverty in California movement (EPIC). Conservative and Republican elements rallied against Sinclair and defeated him in the general election. The Socialist Party in California and nationwide refused to allow its members to be active in any other party, and expelled him, along with socialists who supported his California campaign. Sinclair won 879,537 votes, doubling his primary total, but that was only 38% of the record-breaking turnout as Republican Frank Merriam won with 49% while Raymond Haight, running under the Progressive Party banner, collected 13%. State Socialist Party chair Milen Dempster mounted a feeble effort to hold back the enthusiasm for Sinclair, gaining less than 3,000 votes. The expulsions destroyed the Socialist Party in California. More important, Sinclair's campaign encouraged many radicals in other states to turn away from the Socialist Party. Membership, which had climbed back above 19,000 in 1934, declined to less than 6,000 in 1937 and barely 2,000 in 1940.Demise of the all-inclusive party

Norman Thomas, his radical pacifist co-thinkers, and their young Marxist allies of the Militant faction sought to build a mass political movement by transforming the Socialist Party into what they called an "all-inclusive party". Not only was an appeal made to the radical intellectuals and trade unionists who were the historic core of the organization, but an effort was made to work closely with the Communist Party in joint actions and to infuse the Socialist Party with the leading personnel of small radical oppositional organizations, including in particular the anti-Stalinist communist groupings headed by Jay Lovestone (the so-called "Lovestoneites") and James P. Cannon (the so-called "Trotskyists"). An array of left-wing intellectuals came into the Socialist orbit as a result of this venture, including (from the Lovestoneites) Bertram D. Wolfe, Herbert Zam and Benjamin Gitlow, as well as (from the Trotskyists) Max Shachtman, James Burnham, Martin Abern and Hal Draper. A broad array of radicals from other tendencies also contributed to the pages of the party's official theoretical journal, including from the Communist Party orbit Joseph P. Lash of the American Student Union, the radical novelist James T. Farrell, public intellectual Sidney Hook, leading American Marxist of the 1910s Louis B. Boudin and Canadian Trotskyist Maurice Spector.

A bid was made to unite the factional and marginalized American Left in a common cause, and great hope was held for success in the enterprise. After the Nazis rose in Germany and Austria by 1934, no longer did the Communist Party engage in its Third Period epithets against the Socialists as so-called "social fascism, social fascists". Lillian Symes wrote in the Socialist Party's theoretical magazine in February 1937 of the "incredible change" taking place in the Communist Party in its seeming abandonment of sectarianism and move toward a broad "people's front" against fascism. At the same time, other radical organizations sought to alter their tactics so as to rapidly build an aggressive left-wing organization to oppose nascent fascism. Since 1934, the French Trotskyist organization had entered the French Socialist Party in an effort to build its strength and win support for its ideas. Pressure to follow this policy of the "French Turn" was building among the American Trotskyist group. For a brief period in 1935 and 1936, the vision of the Socialist Party as an "all-inclusive party" that aggregated radical oppositionists and possibly even worked with the Communist Party in common cause seemed achievable.

In January 1936, just as the National Executive Committee of the Socialist Party was expelling the Old Guard, a factional battle was being won in the Trotskyist Workers Party of the United States to join the Socialist Party when a national branch referendum voted unanimously for entry. Negotiations began between the Workers Party and Socialist leaderships, with the decision ultimately made to allow admissions only on the basis of individual applications for membership, rather than en masse admission of the entire group. On June 6, 1936, the Workers Party's weekly newspaper, ''The New Militant'', published its last issue and announced "Workers Party Calls All Revolutionary Workers to Join Socialist Party". About half of the Workers Party heeded the call and entered the Socialist Party.

Although party leader Jim Cannon later hinted that the Trotskyists' entry into the Socialist Party had been a contrived tactic aimed at stealing "confused young Left Socialists" for his own organization, it seems that at its inception, the entryist tactic was made in good faith. Historian Constance Myers notes that "initial prognoses for the union of Trotskyists and Socialists were favorable" and it was only later that "constant and protracted contact caused differences to surface". The Trotskyists retained a common orientation with the radicalized Socialist Party in their opposition to the European war, their preference for industrial unionism and the Congress of Industrial Organizations over the trade unionism of the

Norman Thomas, his radical pacifist co-thinkers, and their young Marxist allies of the Militant faction sought to build a mass political movement by transforming the Socialist Party into what they called an "all-inclusive party". Not only was an appeal made to the radical intellectuals and trade unionists who were the historic core of the organization, but an effort was made to work closely with the Communist Party in joint actions and to infuse the Socialist Party with the leading personnel of small radical oppositional organizations, including in particular the anti-Stalinist communist groupings headed by Jay Lovestone (the so-called "Lovestoneites") and James P. Cannon (the so-called "Trotskyists"). An array of left-wing intellectuals came into the Socialist orbit as a result of this venture, including (from the Lovestoneites) Bertram D. Wolfe, Herbert Zam and Benjamin Gitlow, as well as (from the Trotskyists) Max Shachtman, James Burnham, Martin Abern and Hal Draper. A broad array of radicals from other tendencies also contributed to the pages of the party's official theoretical journal, including from the Communist Party orbit Joseph P. Lash of the American Student Union, the radical novelist James T. Farrell, public intellectual Sidney Hook, leading American Marxist of the 1910s Louis B. Boudin and Canadian Trotskyist Maurice Spector.

A bid was made to unite the factional and marginalized American Left in a common cause, and great hope was held for success in the enterprise. After the Nazis rose in Germany and Austria by 1934, no longer did the Communist Party engage in its Third Period epithets against the Socialists as so-called "social fascism, social fascists". Lillian Symes wrote in the Socialist Party's theoretical magazine in February 1937 of the "incredible change" taking place in the Communist Party in its seeming abandonment of sectarianism and move toward a broad "people's front" against fascism. At the same time, other radical organizations sought to alter their tactics so as to rapidly build an aggressive left-wing organization to oppose nascent fascism. Since 1934, the French Trotskyist organization had entered the French Socialist Party in an effort to build its strength and win support for its ideas. Pressure to follow this policy of the "French Turn" was building among the American Trotskyist group. For a brief period in 1935 and 1936, the vision of the Socialist Party as an "all-inclusive party" that aggregated radical oppositionists and possibly even worked with the Communist Party in common cause seemed achievable.

In January 1936, just as the National Executive Committee of the Socialist Party was expelling the Old Guard, a factional battle was being won in the Trotskyist Workers Party of the United States to join the Socialist Party when a national branch referendum voted unanimously for entry. Negotiations began between the Workers Party and Socialist leaderships, with the decision ultimately made to allow admissions only on the basis of individual applications for membership, rather than en masse admission of the entire group. On June 6, 1936, the Workers Party's weekly newspaper, ''The New Militant'', published its last issue and announced "Workers Party Calls All Revolutionary Workers to Join Socialist Party". About half of the Workers Party heeded the call and entered the Socialist Party.

Although party leader Jim Cannon later hinted that the Trotskyists' entry into the Socialist Party had been a contrived tactic aimed at stealing "confused young Left Socialists" for his own organization, it seems that at its inception, the entryist tactic was made in good faith. Historian Constance Myers notes that "initial prognoses for the union of Trotskyists and Socialists were favorable" and it was only later that "constant and protracted contact caused differences to surface". The Trotskyists retained a common orientation with the radicalized Socialist Party in their opposition to the European war, their preference for industrial unionism and the Congress of Industrial Organizations over the trade unionism of the Split with the Trotskyists

Before the March convention, the Trotskyist Socialist Appeal (US, 1935), Socialist Appeal faction held an organizational gathering of their own, meeting in Chicago, with 93 delegates gathering on February 20–22, 1937. The meeting organized the faction on a permanent basis, electing a National Action Committee of five to "coordinate branch work" and "formulate Appeal policies". Two delegates from the Clarity caucus were in attendance. James Burnham vigorously attacked the Labour and Socialist International, the international organization of left-wing parties to which the Socialist Party belonged, and tension rose along these lines among the Trotskyists. United action between the Clarity and Appeal groups was not forthcoming and an emergency meeting of Vincent R. Dunne and Cannon was held in New York with leaders of the various factions, including Thomas, Jack Altman, and Gus Tyler of Clarity. At this meeting Thomas pledged that the upcoming convention would make no effort to terminate the various factions' newspapers. No action was taken at the 1937 convention to expel the Trotskyist "Appeal faction", but pressure continued to build along these lines, fueled by the Communist Party's increasingly hysterical denunciations of Trotsky and his followers as wreckers and agents of international fascism. The convention passed a ban on future branch resolutions on controversial matters, an effort to rein in the factions' activities at the local level. It also banned factional newspapers, a move directly targeting ''The Socialist Appeal'', and formally established ''The Socialist Call'' as the party's national organ. Constance Myers indicates that three factors led to the expulsion of the Trotskyists from the Socialist Party in 1937: the divergence between the official Socialists and the Trotskyist faction on the issues, the determination of Altman's wing of the Militants to oust the Trotskyists, and Trotsky's own decision to move toward a break with the party. Recognizing that the Clarity faction had chosen to stand with the Altmanites and the Thomas group, Trotsky recommended that the Appeal group focus on disagreements over Spain to provoke a split. At the same time, Thomas, freshly returned from Spain, had concluded that the Trotskyists had joined the Socialist Party not to make it stronger, but to capture it for their own purposes. On June 24–25, 1937, a meeting of the Appeal faction's National Action Committee voted to ratchet up the rhetoric against American Labor Party and Republican Party (United States), Republican nominee for mayor of New York Fiorello LaGuardia, a favorite son of many in Socialist ranks, and to reestablish its newspaper, ''The Socialist Appeal.''Myers, ''The Prophet's Army,'' p. 139. This was met with expulsions from the party beginning August 9 with a rump meeting of the Central Committee of Local New York, which expelled 52 New York Trotskyists by a vote of 48 to 2, with 18 abstentions, and ordered 70 more to be brought up on charges. Wholesale expulsions followed, with a major section of the Young People's Socialist League (1907), Young People's Socialist League leaving the party with the Trotskyists. Secretary of Local New York Jack Altman declared that the Trotskyists "were expelled for attempting to undermine the Socialist Party, for loyalty and allegiance to an opponent organization, the Bureau of the Fourth International, and for refusing to abide by the decisions and discipline of the National convention, the National Executive Committee, and the City Central Committee of the party, and for no other reason". Editor Gus Tyler of ''The Socialist Call'' echoed Altman's sentiments, emphasizing that "the Trotskyites have, during the last week, [...] abandoned the usual means of inner party controversy—debate and appeals through party channels—and, like the Old Guard, have carried their argument into the public, into the capitalist press".[Gus Tyler], "The Trotskyites," ''The Socialist Call,'' vol. 3, whole no. 127 (August 21, 1937), p. 4. ''The Socialist Call''s editor saw the Trotskyist faction's issuance of a statement to ''The New York Times'' and the relaunch of its newspaper, ''The Socialist Appeal'', as particularly galling.Collapse of the united front

Things turned out no better for the official Communist Party, devoted as it was to Stalin's regime. The February–March 1937 joint plenum of the Central Committee and Central Control Commission of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, All-Union Communist Party in Moscow, which green-lighted a massive avalanche of secret police terror known to history as the Great Purge, changed everything. Baby steps towards multi-candidate elections and the rule of law in the Soviet Union crumbled instantly as show trials, spy mania, mass arrests and mass executions swept the land. The Trotskyist movement in the Soviet Union was particularly targeted, accused of plotting murder of Soviet officials and conducting sabotage and espionage in preparation for a fascist invasion—seemingly insane charges that the Soviet elite genuinely believed. Blood flowed like water as alleged Trotskyists and other politically suspect individuals were rounded up, "investigated" and disposed of with a pistol shot in the base of the skull or a 10-year sentence in the gulag. Around the world, Stalin's and Trotsky's adherents raged against each other. In Spain, the country in which the Lovestoneites invested most of their emotional energy as fervid supporters of the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), 1937 marked a similar bloodbath, with the Communist Party of Spain (main), Communist Party of Spain achieving hegemony among the Second Spanish Republic, Republican forces and conducting bloody purges of their own at the Soviet secret police's behest. Joint action between Communist oppositionists and the unflinching loyalists to Moscow was henceforth impossible. In 1937, Norman Thomas willingly acceded to a request from the League for Industrial Democracy (LID) to write a pamphlet on "Democracy versus Dictatorship". Thomas pulled no punches about the regime in the Soviet Union:There are still in both the eastern and western hemispheres many examples of rather crude and primitive military dictatorships. [...] They preach a nationalism whose benefits, spiritual or material, to some degree are for all the people. They profess a positive and paternal concern for the masses. If they rule them sternly that is for their own good. [...]Thomas further noted the Communist Party monopoly on the press, radio, schools, army and government and recalled his own recent visit to Moscow, writing:

In the USSR the dictatorship has been the dictatorship of the Communist Party, but all of its professions and all of its performance has been in the name of the entire working class, and the Communist Party still gives lip-service to a final withering away of all dictatorship, even the dictatorship of the proletariat.

The old keenness of political discussion in the party has almost died, at least in so far as policy is concerned. (Criticism of administration is still allowed). A quotation from Stalin is a final answer to all argument. He receives the same sort of exaggerated veneration in public appearances, in the display of his picture, and in written references to him that is accorded to a Mussolini or a Hitler.Any thought of common-cause with the Communists was now dismissed by Thomas, who indicated that the Communists' fairly recent change of line from fighting the existing trade unions and damning of all political opponents as "social fascists" to attempting to build a "popular front" was merely tactical, related to the perceived needs of Soviet foreign policy to build coalitions with capitalist countries to forestall fascist invasion. The factional havoc of the move to the "all-inclusive party" paralyzed activity while the Old Guard's new group, the Social Democratic Federation of America, controlled the bulk of the Socialist Party's former property and the allegiance of those best able to fund the organization. The expulsions of the Trotskyists and disintegration of the party's youth section left the organization greatly weakened, its membership at a new low.

Opposition to the New Deal and discrimination in the armed services

By 1940, only a small committed core remained in the Socialist Party, including a considerable number of militant pacifists. The Socialist Party continued to oppose Roosevelt's

By 1940, only a small committed core remained in the Socialist Party, including a considerable number of militant pacifists. The Socialist Party continued to oppose Roosevelt's Reunification

Reunification with the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) was long a goal of Norman Thomas and his associates remaining in the Socialist Party. As early as 1938, Thomas had acknowledged that a number of issues had been involved in the split which led to the formation of the rival Social Democratic Federation, including "organizational policy, the effort to make the party inclusive of all socialist elements not bound by communist discipline; a feeling of dissatisfaction with social democratic tactics which had failed in Germany" as well as "the socialist estimate of Russia; and the possibility of cooperation with communists on certain specific matters". Still, he held that "those of us who believe that an inclusive socialist party is desirable, and ought to be possible, hope that the growing friendliness of socialist groups will bring about not only joint action but ultimately a satisfactory reunion on the basis of sufficient agreement for harmonious support of a socialist program". The Socialist Party and the SDF merged to form the Socialist Party-Social Democratic Federation (SP-SDF) in 1957. A small group of holdouts refused to reunify, establishing a new organization called the Democratic Socialist Federation. When the Soviet Union led an invasion of Hungary in 1956, half of the members of Communist Parties around the world quit—in the United States alone half did and many joined the Socialist Party.Realignment, civil rights movement and the War on Poverty

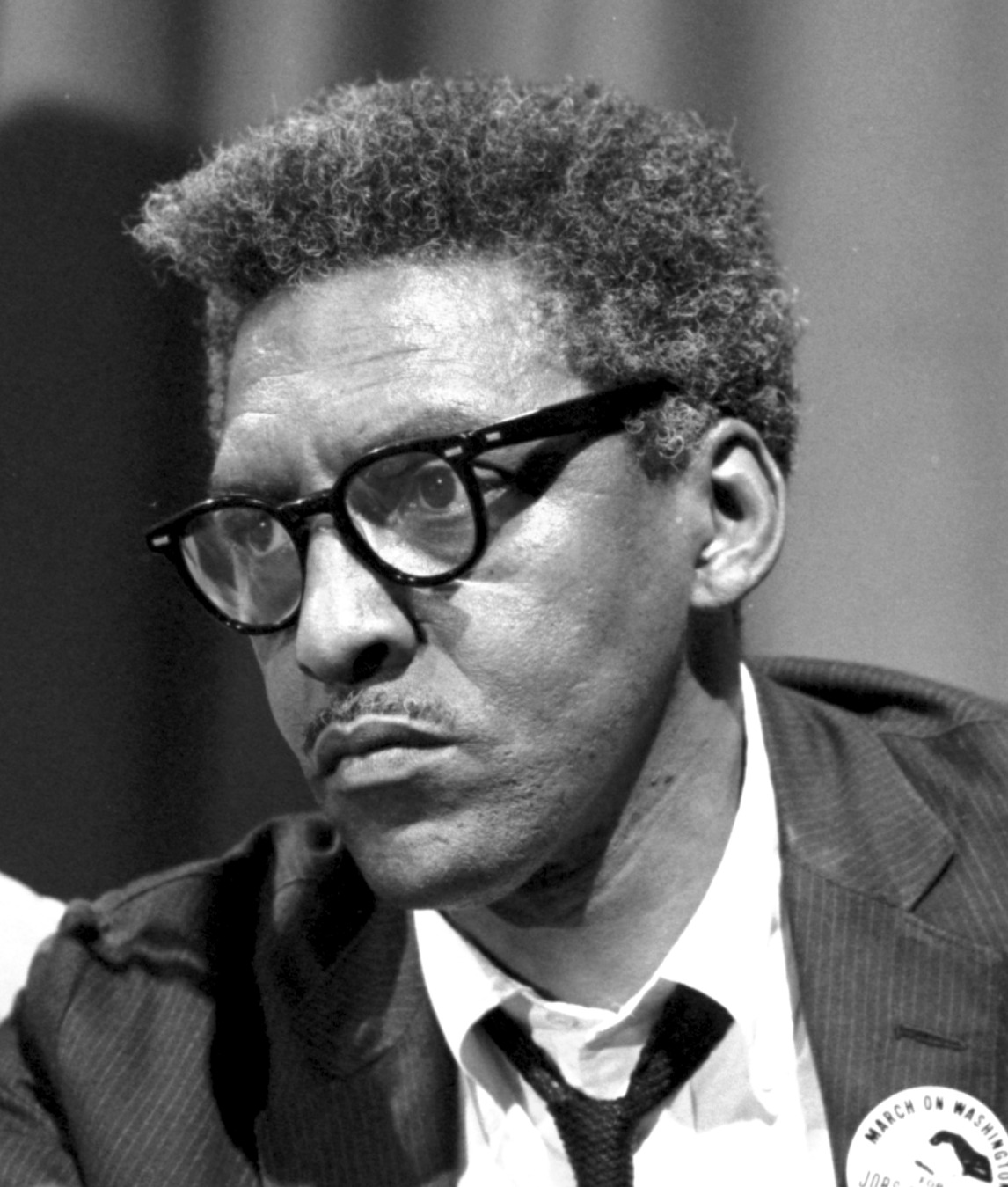

In 1958, the party admitted to its ranks the members of the recently dissolved Independent Socialist League, which had been led by Max Shachtman. Shachtman had developed a Marxist critique of Soviet Communism as "bureaucratic collectivism", a new form of class society that was more oppressive than any form of capitalism. Shachtman's theory was similar to that of many dissidents and refugees from communism, such as the theory of the "new class" proposed by Yugoslavian dissident Milovan Đilas (Djilas).Page 6: Shachtman was an extraordinary public speaker and formidable in debate and his intelligent analysis attracted young socialists like Irving Howe and Michael Harrington. Shachtman's denunciations of the Soviet 1956 invasion of Hungary attracted younger activists like Tom Kahn and Rachelle Horowitz. Shachtman's youthful followers were able to bring new vigor into the party and Shachtman encouraged them to take positions of responsibility and leadership. As a young leader, Harrington sent Kahn and Horowitz to help Bayard Rustin with the civil rights movement. Rustin had helped to spread pacificism and non-violence to leaders of the civil rights movement like Martin Luther King Jr., Martin Luther King Jr. while Kahn and Horowitz quickly became close assistants of Rustin. The civil rights movement benefited from intelligence and analysis of Shachtman and increasingly of Kahn. Rustin and his young aides, dubbed the Bayard Rustin Marching and Chowder Society by Harrington, organized many protest activities. The young socialists helped Rustin and A. Philip Randolph organize the 1963 March on Washington, where King delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech. Harrington soon became the most visible socialist in the United States when his ''The Other America'' became a best seller, following a long and laudatory ''The New Yorker, New Yorker'' review by Dwight Macdonald. Harrington and other socialists were called to Washington, D.C., to assist the Presidency of John F. Kennedy, Kennedy administration and then the Lyndon B. Johnson#Presidency (1963–1969), Johnson administration's War on Poverty and Great Society. The young socialists' role in the civil rights movement made the Socialist Party more attractive. Harrington, Kahn and Horowitz were officers and staff-persons of the League for Industrial Democracy (LID), which helped to start the New Left Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). The three LID officers clashed with the less experienced activists of SDS, like Tom Hayden, when the latter's Port Huron Statement criticized socialist and liberal opposition to communism and criticized the labor movement while promoting students as agents of social change. LID and SDS split in 1965, when SDS voted to remove from its constitution the "exclusion clause" that prohibited membership by communists. The SDS exclusion clause had barred "advocates of or apologists for totalitarianism". The clause's removal effectively invited "disciplined cadre" to attempt to "take over or paralyze" SDS as had occurred to mass organizations in the thirties. The experience of the civil rights movement and the coalition of labor unions and other progressive forces suggested that the United States was changing and that a mass movement of the democratic left was possible. In terms of electoral politics, Shachtman, Harrington and Kahn argued that it was a waste of effort to run electoral campaigns as Socialist Party candidates against Democratic Party candidates. They instead advocated a political strategy called "realignment" that prioritized strengthening labor unions and other progressive organizations that were already active in the Democratic Party. Contributing to the day-to-day struggles of the civil rights movement and labor unions had gained socialists credibility and influence and had helped to push politicians in the Democratic Party toward social-democratic positions on civil rights and the War on Poverty.From the Socialist Party to Social Democrats, USA

The Socialist Party's 1972 convention had two co-chairmen, Bayard Rustin and Charles S. Zimmerman of the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU);Gerald Sorin, ''The Prophetic Minority: American Jewish Immigrant Radicals, 1880-1920.'' Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985; p. 155. and a First National Vice Chairman, James S. Glaser, who were reelected by acclamation. In his opening speech to the convention, Rustin called for the group to organize against the "reactionary policies of the Nixon Administration" and also criticized the "irresponsibility and élitism of the 'New Politics' liberals". The party changed its name to Social Democrats, USA (SDUSA) by a vote of 73 to 34.

*

''The New York Times'' reported on the 1972 convention on other days, e.g.

*

* Renaming the party SDUSA was meant to be "realistic". ''The New York Times'' observed that the Socialist Party had last sponsored a Darlington Hoopes, candidate for President in

The party changed its name to Social Democrats, USA (SDUSA) by a vote of 73 to 34.

*

''The New York Times'' reported on the 1972 convention on other days, e.g.

*

* Renaming the party SDUSA was meant to be "realistic". ''The New York Times'' observed that the Socialist Party had last sponsored a Darlington Hoopes, candidate for President in Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee and Union for Democratic Socialism

Late in October 1972, before the Socialist Party's December Convention, Harrington resigned as National Co-Chairman of the Socialist Party.James Ring Adams, "Division in American Socialism," ''New America'' [New York], vol. 11, no. 15 (October 15, 1973), p. 6. Although little remarked upon at the time despite Harrington's status as "possibly the most widely known of the Socialist leaders since the death of Norman Thomas", it soon became clear that this was the precursor of a decisive split in the organization. Harrington had written extensively about the progressive potential of the so-called "New Politics" in the Democratic Party and had come to advocate unilateral withdrawal from the Vietnam War and positions more conservative party members saw as "avant-garde" on the questions of abortion and gay rights movement, gay rights. This put him and his co-thinkers at odds with the party's younger generation of leaders, who espoused a strongly labor-oriented direction for the party and who were broadly supportive of AFL–CIO leader George Meany. In the early spring of 1973, Harrington resigned from the SDUSA. The same year, he and his supporters formed the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC). At its start, DSOC had 840 members, of whom 2% served on its national board, while approximately 200 had been members of SDUSA or its predecessors whose membership was then 1,800, according to a 1973 profile of Harrington. Its high-profile members included Congressman Ron Dellums and William Winpisinger, President of the International Association of Machinists. In 1982, DSOC established the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) upon merging with the New American Movement, an organization of democratic socialists mostly from the New Left. The Union for Democratic Socialism was another organization formed by former members of the Socialist Party. David McReynolds, who had resigned from the Socialist Party between 1970 and 1971, along with many from the Debs Caucus, were the core members. In 1973, the UDS declared itself the Socialist Party USA.National Conventions

Presidential tickets

Other prominent members

This is a brief representative sample of Socialist Party leaders not listed above as presidential or vice presidential candidates. For a more comprehensive list, see the list of members of the Socialist Party of America. *Newspapers and magazines

* ''American Appeal'' (Chicago) * ''American Socialist'' (Chicago) * ''American Socialist Quarterly'' (New York) * '' Appeal to Reason'' (Girard, Kansas) * ''Chicago Daily Socialist'' (Chicago) * ''The Class Struggle (journal), The Class Struggle'' (New York) * ''Cleveland Citizen'' (Cleveland) * ''The Comrade'' (New York) * ''The Eye Opener'' (Chicago) * ''Hammer and Tongs (magazine), Hammer and Tongs'' (New York and elsewhere) * ''International Socialist Review (1900), International Socialist Review'' (Chicago) * ''The Jewish Daily Forward'' (New York) * ''Labor Action'' (San Francisco) * ''The Liberator (magazine), The Liberator'' (New York) * ''The Masses'' (New York) * ''The Messenger Magazine'' (New York) * ''Miami Valley Socialist'' (Dayton, Ohio) * ''Milwaukee Leader'' (Milwaukee) * ''The National Rip-Saw'' (St. Louis) * ''Naujienos (socialist newspaper), Naujienos'' (Chicago) * ''The New Age'' (Buffalo, New York) * ''New America (newspaper), New America'' (New York) * ''The New Day (newspaper), The New Day'' (Milwaukee) * ''The New Leader'' (New York) * ''New Times (Minneapolis), New Times'' (Minneapolis) * ''The New Review'' (New York) * ''New York Call'' (New York) * ''New Yorker Volkszeitung'' * ''Ohio Socialist'' (Cleveland) * ''Pearson's Magazine'' (New York) * ''Proletarec'' (Chicago) * ''Rabotnik Polski'' (Chicago) * ''Raivaaja'' (Fitchburg, Massachusetts) * ''Reading Labor Advocate'' (Reading, Pennsylvania) * ''The Social Democrat (Chicago), The Social Democrat'' (Chicago) * ''The Socialist (Columbus), The Socialist'' (Columbus, Ohio) * ''The Socialist (Seattle), The Socialist'' (Seattle, Toledo, Ohio and Caldwell, Indiana) * ''Socialist Appeal (US, 1935), The Socialist Appeal'' (Chicago and New York) * ''The Socialist Call'' (New York) * ''Socialist Party Monthly Bulletin'' (Chicago) * ''St. Louis Labor'' * ''Truth (Duluth newspaper), Truth'' (Duluth, Minnesota) * ''Työmies'' (Hancock, Missouri) * ''Der Wecker'' (New York) * ''Wilshire's Magazine'' (Los Angeles and New York) * ''The World (Oakland), The World'' (Oakland, California)Official national press

Most of the socialist press was privately owned as the party was concerned that a single official publication might lead to censorship in favor of the editors' views, in much the same way Daniel DeLeon used ''The People'' to dominate the Socialist Labor Party. A number of papers carried the party's official notices in its first years, the most important being ''The Worker'' (New York), ''The Appeal to Reason'' (Girard, Kansas), ''The Socialist'' (Seattle and Toledo, Ohio), ''The Worker's Call'' (Chicago), ''St. Louis Labor'', and ''The Social Democratic Herald'' (Milwaukee). The party soon discovered that it needed a more regular means of communication with its members and the 1904 National Convention decided to establish a regular party organ. Over the next seven decades, a series of official publications were issued directly by the SPA, most of which are today available on microfilm in essentially full runs: * ''Socialist Party Bulletin'' (monthly in Chicago) — vol. 1, no. 1 (September 1904), vol. 9, no. 6 (March/April 1913). * ''Socialist Party Weekly Bulletin'' (Chicago). — 1905? to 1909?. Mimeographed. New York Public Library has partial run on microfilm, August 12, 1905 – September 4, 1909. * ''The Party Builder'' (weekly in Chicago) — whole no. 1 (August 28, 1912) – whole no. 88 (July 11, 1914). * ''The American Socialist'' (weekly in Chicago). — vol. 1, no. 1 (July 18, 1914), vol. 4, no. 8 (September 8, 1917). * ''The Eye Opener'' (weekly in Chicago) — previously existing publication, official from vol. ?, no. ? (August 25, 1917) to vol. ?, no. ? (June 1, 1920). * ''Socialist Party Bulletin'' (monthly in Chicago) — vol. 1, no. 1 (February 1917), vol. ?, no. ? (June 1920). It may have suspended publication from July 1917 to May 1919. * ''The New Day'' (weekly in Milwaukee) — vol. 1, no. 1 (June 12, 1920), vol. ?, no. ? (July 22, 1922). * ''Socialist World'' (monthly in Chicago) — vol. 1, no. 1 (July 15, 1920), vol. 6, no. 8 (October 1925). * ''American Appeal'' (weekly in Chicago) — vol. 7, no. 1 (January 1, 1926), vol. 8, no. 48 (November 26, 1927). It was merged into ''The New Leader''. * ''Labor and Socialist Press News'' (Chicago) — August 30, 1929 – February 26, 1932. Mimeographed weekly. ** ''Labor and Socialist Press Service'' (Chicago) — March 4, 1932 – July 17, 1936. Mimeographed weekly. * ''American Socialist Quarterly'' (New York) — vol. 1, no. 1 (January 1932), vol. 4, no. 3 (November 1935). **''American Socialist Monthly'' (New York) — vol. 5, no. 1 (March 1936), vol. 6, no. 1 (May 1937). ** ''Socialist Review'' (irregular in New York) — vol. 6, no. 2 (September 1937), vol. 7, no. 2 (Spring 1940). * ''Socialist Action'' (monthly in Chicago) — vol. 1, no. 1 (October 20, 1934), vol. 2, no. 9 (November 1936). Three mimeographed "Socialist Action Pamphlets" also produced, press run of 200. * ''The Socialist Call'' (various in New York and Chicago) — vol. 1, no. 1 (March 23, 1935), vol. ?, no. ? (Spring 1962).Goldwater, Walter (1964). ''Radical Periodicals in America, 1890-1950''. New Haven: Yale University Library. pp. 2–3, 38–39. * ''Hammer and Tongs'' (irregular in New York and Milwaukee) — no numbers used, January 1940–November 1972. * ''Socialist Campaigner'' (irregular in New York) — vol. 1, no. 1 (early 1940) to vol. 5, no. 3 (December 26, 1944). Mimeographed. * ''Organizers' Bulletin'' (irregular in New York) — no. 1 (middle 1940) to no. 3 (September 1940). Mimeographed. * ''Progress Report'' (monthly in New York) — unnumbered, June 1950 – September 1951. Mimeographed, sent to branch organizers and functionaries. ** ''News and Views'' (monthly in New York) — unnumbered, October 1951–December 1953. Mimeographed, sent to branch organizers and functionaries. * ''Socialist Party Bulletin'' (monthly in New York) — unnumbered, October 1955?–January 1957. Two page typeset newsletter. ** ''Socialist Bulletin'' (monthly in New York) — unnumbered, February 1957–April 1958?. Name change due to merger with the Social Democratic Federation (United States), Social Democratic Federation. * ''New America'' (bimonthly in New York) — vol. 1, no. 1 (October 18, 1960), vol. ?, no. ? (1985). Continued as organ of Social Democrats, USA.Executive Secretaries

* 1901–1903: Leon Greenbaum * 1903–1905: William Mailly * 1905–1911: J. Mahlon Barnes * 1911–1913: John M. Work * 1913–1916: Walter Lanfersiek * 1916–1919: Adolph Germer * 1919–1924:Electoral history

Presidential elections