Smithsonian–Roosevelt African Expedition on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Smithsonian–Roosevelt African Expedition was an expedition to tropical Africa in 1909-1911 led by former United States president

The party set sail from New York City on the steamer ''Hamburg'' on March 23, 1909, shortly after the end of Roosevelt's presidency on March 4. The ''Hamburg'' arrived at its destination at

The party set sail from New York City on the steamer ''Hamburg'' on March 23, 1909, shortly after the end of Roosevelt's presidency on March 4. The ''Hamburg'' arrived at its destination at

TheodoreRoosevelt.com's account of the trip and review of African Game Trails with photos

*

fro

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, funded by Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans i ...

and sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

. Its purpose was to collect specimens for the Smithsonian's new Natural History museum, now known as the National Museum of Natural History

The National Museum of Natural History is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. It has free admission and is open 364 days a year. In 2021, with 7 ...

. The expedition collected around 11,400 animal specimens which took Smithsonian naturalists eight years to catalog. Following the expedition, Roosevelt chronicled it in his book ''African Game Trails''.

Participants and resources

The group was led by the legendary hunter-tracker R. J. Cunninghame. Participants on the Expedition included Australian sharpshooter Leslie Tarlton; three American naturalists,Edgar Alexander Mearns

Edgar Alexander Mearns (September 11, 1856 – November 1, 1916) was an American surgeon, ornithologist and field naturalist. He was a founder of the American Ornithologists' Union.

Life

Mearns was born in n Highland Falls, New York to Al ...

, a retired U.S. Army surgeon; Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is consider ...

taxidermist Edmund Heller

Edmund Heller (May 21, 1875 – July 18, 1939) was an American zoologist. He was President of the Association of Zoos & Aquariums for two terms, from 1935-1936 and 1937-1938.

Early life

While at Stanford University, he collected specimens in the ...

, and mammalologist John Alden Loring

John Alden Loring (March 31, 1871 – May 8, 1947) was a mammalogist and field naturalist who served with the Bureau of Biological Survey, United States Department of Agriculture, the Bronx Zoological Park, the Smithsonian Institution and numerous ...

; and Roosevelt's 19-year-old son Kermit, on a leave of absence from Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

. The expedition also included a large number of porters, gunbearers, horse boys, tent men, and ''askari

An askari (from Somali, Swahili and Arabic , , meaning "soldier" or "military", which also means "police" in the Somali language) was a local soldier serving in the armies of the European colonial powers in Africa, particularly in the African G ...

'' guards.Edmund Morris, ''Colonel Roosevelt'' (Random House, 2010), p. 8. Equipment included material for preserving animal hides, including powdered borax

Borax is a salt (ionic compound), a hydrated borate of sodium, with chemical formula often written . It is a colorless crystalline solid, that dissolves in water to make a basic solution. It is commonly available in powder or granular form, ...

, cotton batting, and four tons of salt, as well as a variety of tools, weapons, and other equipment ranging from lanterns to sewing needles. Roosevelt brought a M1903 Springfield in .30-03 caliber and, for larger game, a Winchester 1895 rifle in .405 Winchester

The .405 Winchester (also known as the .405 WCF) is a centerfire rifle cartridge introduced in 1904 for the Winchester 1895 lever-action rifle.Cartridges Of The World, Frank Barnes, Krause Publications It remains to this day one of the most pow ...

. Roosevelt also brought his Pigskin Library, a collection of classics bound in pig leather and transported in a single reinforced trunk.

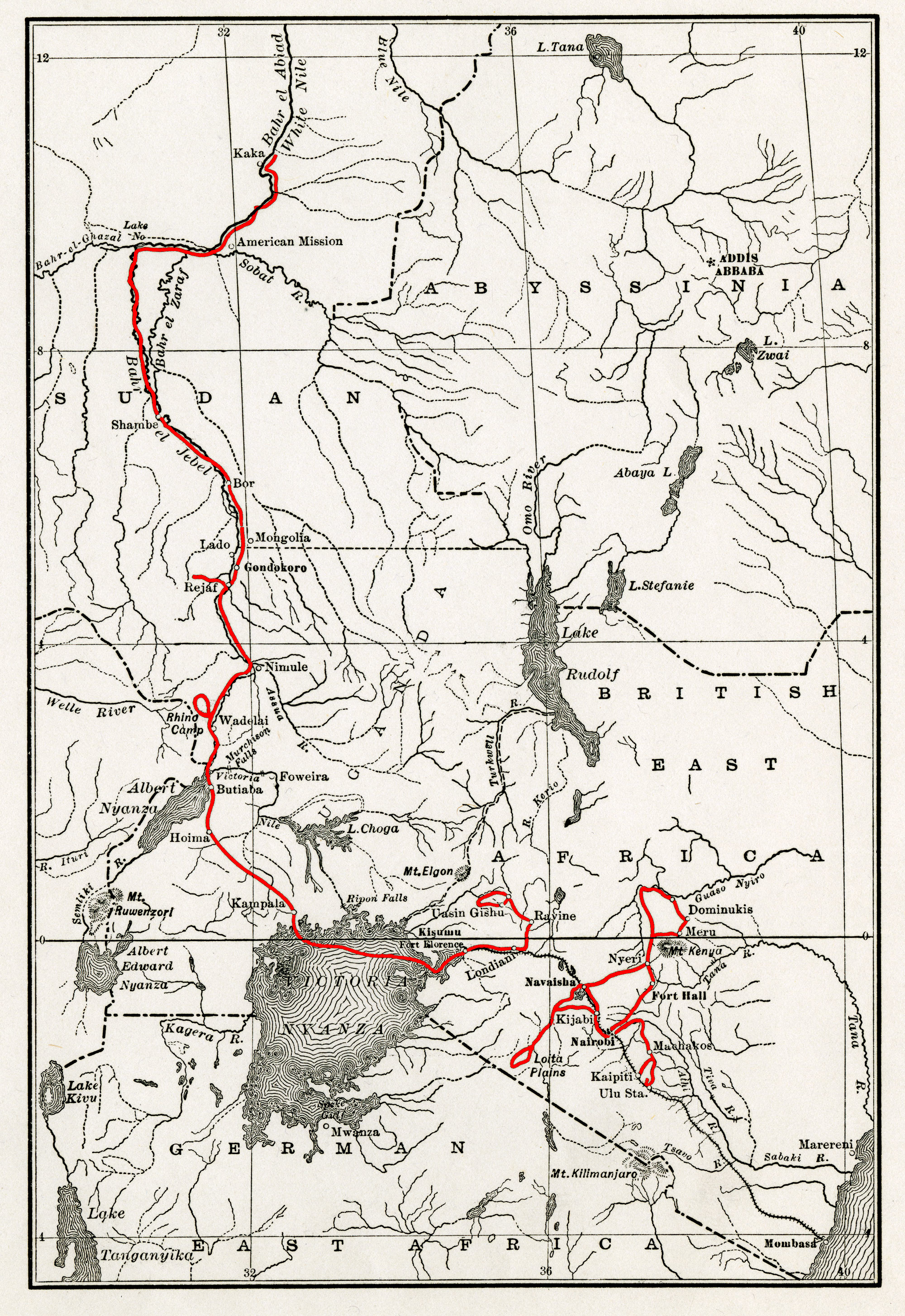

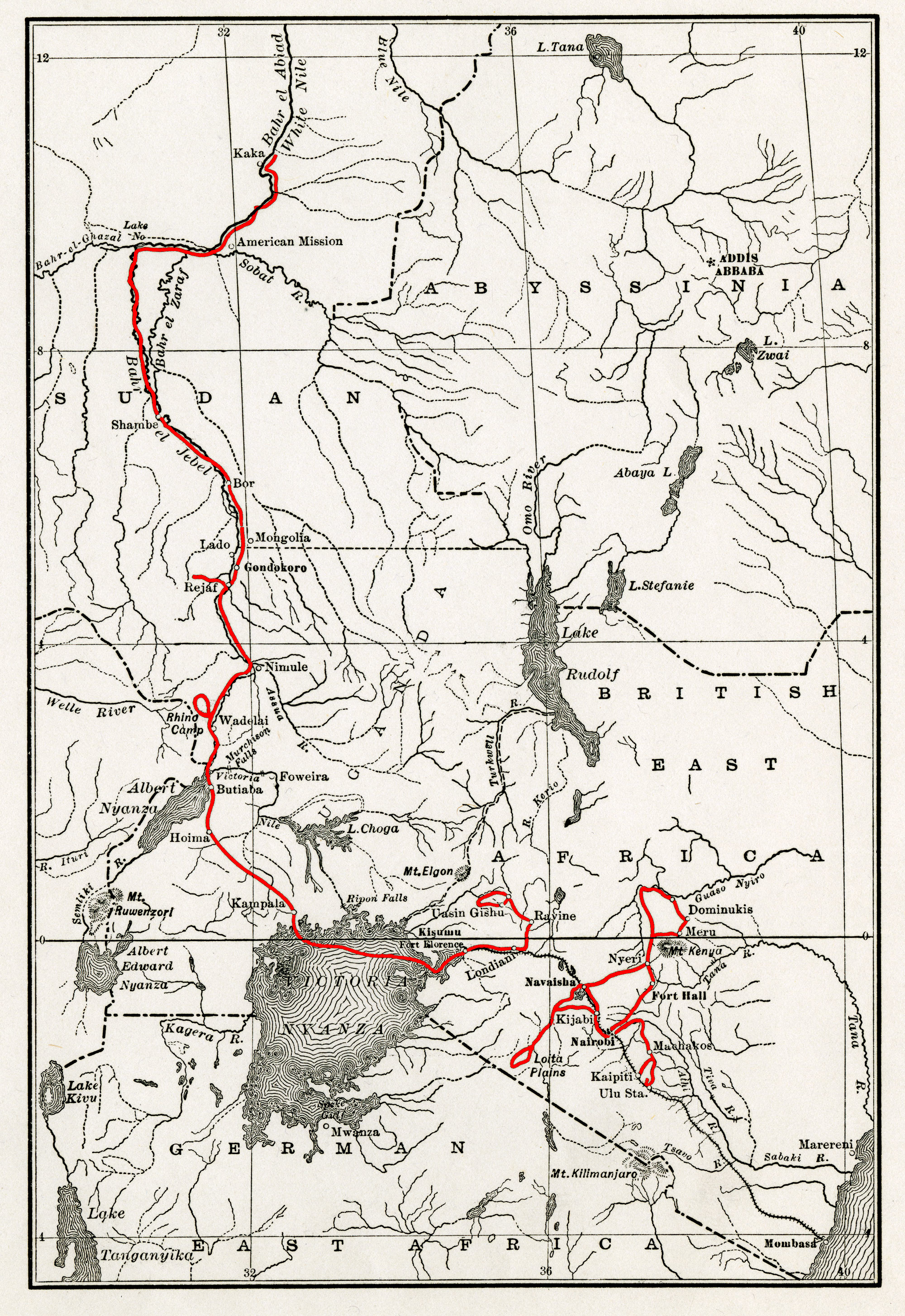

Timeline and route

The party set sail from New York City on the steamer ''Hamburg'' on March 23, 1909, shortly after the end of Roosevelt's presidency on March 4. The ''Hamburg'' arrived at its destination at

The party set sail from New York City on the steamer ''Hamburg'' on March 23, 1909, shortly after the end of Roosevelt's presidency on March 4. The ''Hamburg'' arrived at its destination at Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, where the party boarded the ''Admiral'', a German-flagged ship selected because it permitted the expedition to load large quantities of ammunition. While on board the ''Hamburg'', Roosevelt encountered Frederick Courteney Selous, a longtime friend who was traveling to his own African safari, traversing many of the same areas.

The party landed in Mombasa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of the British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital city status. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town is ...

, British East Africa

East Africa Protectorate (also known as British East Africa) was an area in the African Great Lakes occupying roughly the same terrain as present-day Kenya from the Indian Ocean inland to the border with Uganda in the west. Controlled by Britai ...

(now Kenya

)

, national_anthem = "Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

), traveled to the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

(now Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

) before following the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

to Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

in modern Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

. Financed by Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans i ...

and by his own proposed writings, Roosevelt's party hunted for specimens for the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

and American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 inter ...

in New York.

Results

Roosevelt and his companions killed or trapped approximately 11,397 animals. According to Theodore Roosevelt’s own tally, the figure included about four thousand birds, two thousand reptiles and amphibians, five hundred fish, and 4,897 mammals (other sources put this figure at 5,103). Add to this marine, land and freshwater shells, crabs, beetles and other invertebrates, not to mention several thousand plants, and the number of natural history specimens totals 23,151. A separate collection was made of ethnographic objects. The material took eight years to catalogue. The larger animals shot by Theodore and Kermit Roosevelt are listed on pages 457 to 459 of his book'' African Game Trails''. The total is 512, of which 43 are birds. The number of big game animals killed, was 18 lion, 3 leopard, 6 cheetah, 10 hyena, 12 elephant, 10 buffalo, 9 (now very rare) black rhino and 97White rhino

The white rhinoceros, white rhino or square-lipped rhinoceros (''Ceratotherium simum'') is the largest extant species of rhinoceros. It has a wide mouth used for grazing and is the most social of all rhino species. The white rhinoceros consists ...

. Most of the 469 larger non big game mammals included 37 species and subspecies of antelopes. The expedition consumed 262 of the animals which were required to provide fresh meat for the large number of porters employed to service the expedition. Tons of salted animals and their skins were shipped to Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

; the quantity took years to mount

Mount is often used as part of the name of specific mountains, e.g. Mount Everest.

Mount or Mounts may also refer to:

Places

* Mount, Cornwall, a village in Warleggan parish, England

* Mount, Perranzabuloe, a hamlet in Perranzabuloe parish, C ...

, and the Smithsonian shared many duplicate animals with other museum

A museum ( ; plural museums or, rarely, musea) is a building or institution that cares for and displays a collection of artifacts and other objects of artistic, cultural, historical, or scientific importance. Many public museums make these ...

s. Regarding the large number of animals taken, Roosevelt said, "I can be condemned only if the existence of the National Museum

A national museum is a museum maintained and funded by a national government. In many countries it denotes a museum run by the central government, while other museums are run by regional or local governments. In other countries a much greater numb ...

, the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 inter ...

, and all similar zoological institutions are to be condemned." Some context when considering whether the quantity of animals taken was excessive is that the animals were gathered over a period of ten months and were procured over an area that ranged from Mombasa through Kenya, to Uganda and the Southern Sudan—a distance traveled, with side trips, of several thousand kilometers. The diversity of larger mammal species collected was such that few individuals of any species were shot in any given area, and the large mammals collected had a negligible impact on the great herds of game that roamed East Africa at that time. Apologists for the Roosevelts have pointed out that the number of each big game species shot was very modest by the standards of the time: many hunters of that period, for example, such as Karamoja Bell, had killed over 1,000 elephants each, while the Roosevelts between them killed just eleven. In making this comparison it has to be remembered that the hunters weren’t collecting specimens for museums, but were occasionally employed by landowners to clear animals from land they wanted to use for plantations, and frequently as ivory hunter with or without hunting permit or licenses.

Although the safari was conducted in the name of science, it was as much a political and social event as it was a hunting excursion; Roosevelt interacted with renowned professional hunters and land-owning families, and met many native peoples and local leaders. Roosevelt became a Life Member of the National Rifle Association of America

The National Rifle Association of America (NRA) is a gun rights advocacy group based in the United States. Founded in 1871 to advance rifle marksmanship, the modern NRA has become a prominent gun rights lobbying organization while cont ...

, while President, in 1907 after paying a $25 fee. He later wrote a detailed account in the book ''African Game Trails'', where he describes the excitement of the chase, the people he met, and the flora

Flora is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous) native plants. Sometimes bacteria and fungi are also referred to as flora, as in the terms '' gut flora'' or '' skin flora''.

E ...

and fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is ''flora'', and for fungi, it is '' funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as '' biota''. Zoo ...

he collected in the name of science.

While Theodore Roosevelt greatly enjoyed hunting, he was also an avid conservationist. In ''African Game Trails'' he condemns "game butchery as objectionable as any form of wanton cruelty and barbarity" (although he does note that "to protest against all hunting of game is a sign of softness of head, not of soundness of heart") and as a pioneer of wilderness conservation in the USA he fully supported the British Government's attempts at that time to set aside wilderness areas as game reserves, some of the first on the African continent. He notes (page 17) that "in the creation of the great game reserve through which the Uganda railway runs the British Government has conferred a boon upon mankind", a conservation attitude which Roosevelt helped sow that finally grew and blossomed in the form of the great game parks of East Africa today.

See also

*''Roosevelt in Africa

''Roosevelt in Africa'' is a film by Cherry Kearton, released in 1910. It is a documentary about the Smithsonian–Roosevelt African Expedition, featuring Theodore Roosevelt in Africa. It is shot in silent black and white.

One of the biggest he ...

'' (film)

Further reading

TheodoreRoosevelt.com's account of the trip and review of African Game Trails with photos

*

fro

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Smithsonian-Roosevelt African Expedition Theodore Roosevelt 1909 in science 1910 in science 1909 in Africa 1910 in Africa Expeditions from the United States Smithsonian Institution African expeditions