Smenovekhovtsy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Smenovekhovtsy ( rus, –°–º–µ–Ω–æ–≤–µ—Ö–æ–≤—Ü—ã, p=sm ≤…™n…ôÀàv ≤ex…ôfts…®), a political movement in the

The Smenovekhovtsy ( rus, –°–º–µ–Ω–æ–≤–µ—Ö–æ–≤—Ü—ã, p=sm ≤…™n…ôÀàv ≤ex…ôfts…®), a political movement in the

The Smenovekhovtsy ( rus, –°–º–µ–Ω–æ–≤–µ—Ö–æ–≤—Ü—ã, p=sm ≤…™n…ôÀàv ≤ex…ôfts…®), a political movement in the

The Smenovekhovtsy ( rus, –°–º–µ–Ω–æ–≤–µ—Ö–æ–≤—Ü—ã, p=sm ≤…™n…ôÀàv ≤ex…ôfts…®), a political movement in the Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

n émigré

An ''émigré'' () is a person who has emigrated, often with a connotation of political or social self-exile. The word is the past participle of the French ''émigrer'', "to emigrate".

French Huguenots

Many French Huguenots fled France followin ...

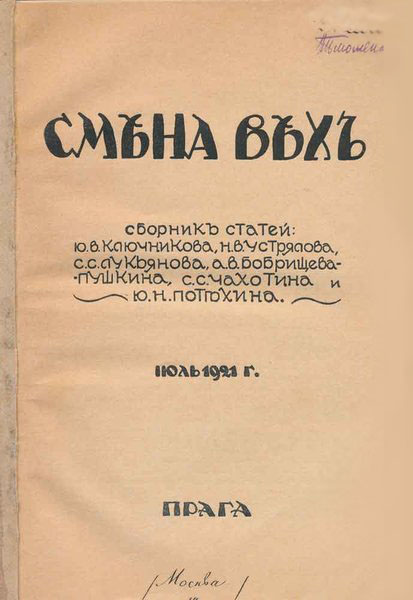

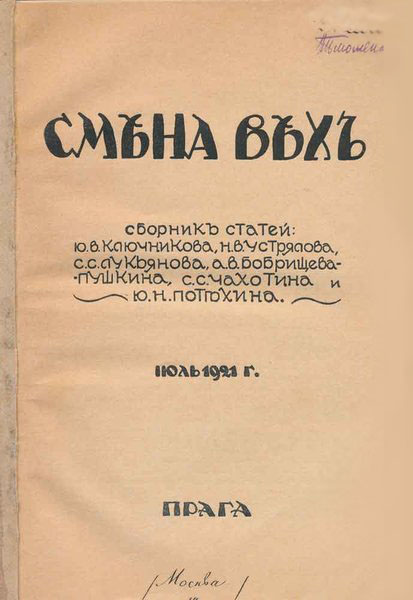

community, formed shortly after the publication of the magazine ''Smena Vekh'' ("Change of Signposts") in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and List of cities in the Czech Republic, largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 milli ...

in 1921. This publication had taken its name from the Russian philosophical publication ''Vekhi

Vekhi ( rus, –í–µ—Ö–∏, p=Ààv ≤ex ≤…™, t=Landmarks) is a collection of seven essays published in Russia in 1909. It was distributed in five editions and elicited over two hundred published rejoinders in two years. The volume reappraising the Russian ...

'' ("Signposts") published in 1909. The ''Smena Vekh'' periodical told its White émigré

White Russian émigrés were Russians who emigrated from the territory of the former Russian Empire in the wake of the Russian Revolution (1917) and Russian Civil War (1917–1923), and who were in opposition to the revolutionary Bolshevik commun ...

readers:

"TheThe ideas in the publication soon evolved into the ''Smenovekhovstvo'' movement, which promoted the concept of accepting theCivil War A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...is lost definitely. For a long timeRussia Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...has been travelling on its own path, not our path ... Either recognize this Russia, hated by you all, or stay without Russia, because a 'third Russia' by your recipes does not and will not exist ... The Soviet regime saved Russia - the Soviet regime is justified, regardless of how weighty the arguments against it are ... The mere fact of its enduring existence proves its popular character, and the historical belonging of its dictatorship and harshness."

Soviet regime

The political system of the Soviet Union took place in a federal single-party soviet socialist republic framework which was characterized by the superior role of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), the only party permitted by the Co ...

and the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

of 1917 as a natural and popular progression of Russia's fate, something which was not to be resisted despite perceived ideological incompatibilities with Leninism. ''Smenovekhovstvo'' encouraged its members to return to Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, –Ý–æ—Å—Å–∏–π—Å–∫–∞—è –°–æ–≤–µ—Ç—Å–∫–∞—è –§–µ–¥–µ—Ä–∞—Ç–∏–≤–Ω–∞—è –°–æ—Ü–∏–∞–ª–∏—Å—Ç–∏—á–µ—Å–∫–∞—è –Ý–µ—Å–ø—É–±–ª–∏–∫–∞, Ross√≠yskaya Sov√©tskaya Federat√≠vnaya Soci ...

, predicting that the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

would not last and would give way to a revival of Russian nationalism

Russian nationalism is a form of nationalism that promotes Russian cultural identity and unity. Russian nationalism first rose to prominence in the early 19th century, and from its origin in the Russian Empire, to its repression during early B ...

.

Smenovekhovtsy supported co-operation with the Soviet government in the hope that the Soviet state would evolve back into a "bourgeois state". Such cooperation was important for the Soviets

Soviet people ( rus, —Å–æ–≤–µÃÅ—Ç—Å–∫–∏–π –Ω–∞—Ä–æÃÅ–¥, r=sovy√©tsky nar√≥d), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, –≥—Ä–∞ÃÅ–∂–¥–∞–Ω–µ –°–°–°–Ý, gr√°zhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in ...

, since the whole Russian "White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White o ...

diaspora" included 3 million people. The leaders of ''smenovekhovstvo'' were mostly former Mensheviks

The Mensheviks (russian: меньшевики́, from меньшинство 'minority') were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

The factions em ...

, Kadets and some Octobrists

The Union of 17 October (russian: –°–æ—é–∑ 17 –û–∫—Ç—è–±—Ä—è, ''Soyuz 17 Oktyabrya''), commonly known as the Octobrist Party (Russian: –û–∫—Ç—è–±—Ä–∏—Å—Ç—ã, ''Oktyabristy''), was a liberal-reformist constitutional monarchist political party in ...

. Nikolay Ustryalov (1890-1937) led the group. On March 26, 1922, the first issue of ''Nakanune'' ( ru , –ù–∞–∫–∞–Ω—É–Ω–µ , translation = On the eve, the ''Smenovekhovtsy'' newspaper) was published; Soviet Russia's first successes in foreign policy were praised. Throughout its career, ''Nakanune'' was subsidised by the Soviet government. Alexey Tolstoy

Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy (russian: link= no, Алексей Николаевич Толстой; – 23 February 1945) was a Russian writer who wrote in many genres but specialized in science fiction and historical novels.

Despite having ...

had become acquainted with the movement in the summer of 1921. In April 1922, he published an open letter

An open letter is a letter that is intended to be read by a wide audience, or a letter intended for an individual, but that is nonetheless widely distributed intentionally.

Open letters usually take the form of a letter addressed to an indiv ...

addressed to émigré leader Nikolai Tchaikovsky

Nikolai Vasilyevich Tchaikovsky (7 January 1851 Adoption_of_the_Gregorian_calendar#Adoption_in_Eastern_Europe.html" ;"title="/nowiki> O.S._26_December_1850.html" ;"title="Adoption of the Gregorian calendar#Adoption in Eastern Europe">O.S. 26 De ...

, and defended the Soviet government for ensuring Russia's unity and for preventing attacks from the neighbouring countries, especially during the Polish-Soviet War of 1919–1921.

Conservative émigrés such as those in the Russian All-Military Union

The Russian All-Military Union ( rus, –Ý—É—Å—Å–∫–∏–π –û–±—â–µ-–í–æ–∏–Ω—Å–∫–∏–π –°–æ—é–∑, abbreviated –Ý–û–í–°, ROVS) is an organization that was founded by White Army General Pyotr Wrangel in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes on 1 Septembe ...

(founded in 1924) opposed the ''Smenoveknovstvo'' movement, viewing it as a promotion of defeatism and moral relativism, as a capitulation to the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, and as desirous of seeking compromise with the new Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

regime. Repeatedly, the Smenoveknovtsi faced accusations of ties with the Soviet secret-police organisation OGPU, which had in fact been active in promoting such ideas in the émigré community. On the ''Smenovekhovstvo'' movement in October 1921, Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

commented: "The Smenovekhovtsy express the moods of thousands of various bourgeois or Soviet collaborators, who are the participants of our New Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) () was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, ...

."

Representatives of the ''Smenovekhovtsy'' who settled in the Soviet Union did not survive the end of the 1930s; almost all the former leaders of the movement were arrested by the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

and executed at a later date.

There were other émigré organizations which, like the ''Smenoveknovtsy'', argued that Russian émigrés should accept the fact of the Russian revolution. These included the Young Russians (Mladorossi

The Union of Mladorossi (russian: Союз Младороссов, ''Soyuz Mladorossov'') was a political group of Russian émigré monarchists (mostly living in Europe) who advocated a hybrid of Russian monarchy and the Soviet system, best evide ...

) and the Eurasians (Evraziitsi

Eurasianism (russian: –µ–≤—Ä–∞–∑–∏–π—Å—Ç–≤–æ, ''yevraziystvo'') is a political movement in Russia which states that Russian civilization does not belong in the "European" or "Asian" categories but instead to the geopolitical concept of Eurasia, ...

). As with the Smenovekhovtsy, these movements did not survive after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. Ukrainian émigrés also fostered a movement in favour of reconciliation with the Soviet regime and of return to the homeland. This included some of the most prominent pre-revolutionary intellectuals such as Mykhailo Hrushevskyi

Mykhailo Serhiiovych Hrushevsky ( uk, Михайло Сергійович Грушевський, Chełm, – Kislovodsk, 24 November 1934) was a Ukrainian academician, politician, historian and statesman who was one of the most important figure ...

(1866-1934) and Volodymyr Vynnychenko

Volodymyr Kyrylovych Vynnychenko ( ua, Володимир Кирилович Винниченко, – March 6, 1951) was a Ukrainian statesman, political activist, writer, playwright, artist, who served as the first Prime Minister of Ukraine. ...

(1880-1951). The Soviet Ukrainian government funded a Ukrainian emigre journal called ''Nova Hromada'' (first published in July 1923) to encourage this trend. The Soviets referred to this movement as a Ukrainian Smena Vekh, as did its opponents among the Ukrainian emigres, who saw it as a defeatist expression of Little Russia

Little Russia (russian: –ú–∞–ª–æ—Ä–æ—Å—Å–∏—è/–ú–∞–ª–∞—è –Ý–æ—Å—Å–∏—è, Malaya Rossiya/Malorossiya; uk, –ú–∞–ª–æ—Ä–æ—Å—ñ—è/–ú–∞–ª–∞ –Ý–æ—Å—ñ—è, Malorosiia/Mala Rosiia), also known in English as Malorussia, Little Rus' (russian: –ú–∞–ª–∞—è –Ý—É— ...

n Russophilia

Russophilia (literally love of Russia or Russians) is admiration and fondness of Russia (including the era of the Soviet Union and/or the Russian Empire), Russian history and Russian culture. The antonym is Russophobia. In the 19th Century, ...

. For this reason, the actual proponents of the trend rejected the label of ''Smenovekhovtsy''.

Bibliography

* Christopher Gilley, The 'Change of Signposts' in the Ukrainian Emigration. A Contribution to the History of Sovietophilism in the 1920s, Stuttgart: ibidem, 2009. * Hilda Hardeman, Coming to Terms with the Soviet Regime. The "Changing Signposts" Movement among Russian Émigrés in the Early 1920s, Dekalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1994. * M.V. Nazarov, The Mission of the Russian Emigration, Moscow: Rodnik, 1994. *''"Changing Landmarks" in Russian Berlin, 1922-1924'' by Robert C. Williams in ''Slavic Review

The ''Slavic Review'' is a major peer-reviewed academic journal publishing scholarly studies, book and film reviews, and review essays in all disciplines concerned with Russia, Central Eurasia, and Eastern and Central Europe. The journal's titl ...

'' Vol. 27, No. 4 (Dec., 1968), pp. 581–593

See also

* Nikolay Vasilyevich Ustryalov *National Bolshevism

National Bolshevism (russian: –Ω–∞—Ü–∏–æ–Ω–∞–ª-–±–æ–ª—å—à–µ–≤–∏–∑–º, natsional-bol'shevizm, german: Nationalbolschewismus), whose supporters are known as National Bolsheviks (russian: –Ω–∞—Ü–∏–æ–Ω–∞–ª-–±–æ–ª—å—à–µ–≤–∏–∫–∏, natsional-bol'sheviki ...

Notes