Slaves In Ancient Greece on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

"The slave is a necessary instrument, like other kinds of wealth, for the moral life." p.313 This paradigm was notably questioned in

The ancient Greeks had several words to indicate slaves, which leads to textual ambiguity when they are studied out of their proper context. In

The ancient Greeks had several words to indicate slaves, which leads to textual ambiguity when they are studied out of their proper context. In

Slaves were present through the

Slaves were present through the

All activities were open to slaves with the exception of politics. For the Greeks, politics was the only occupation worthy of a citizen, the rest being relegated wherever possible to non-citizens. It was status that was of importance, not occupation.

The principal use of slavery was in

All activities were open to slaves with the exception of politics. For the Greeks, politics was the only occupation worthy of a citizen, the rest being relegated wherever possible to non-citizens. It was status that was of importance, not occupation.

The principal use of slavery was in

It is difficult to estimate the number of slaves in ancient Greece, given the lack of a precise census and variations in definitions during that era. It seems certain that Athens had the largest slave population, with as many as 80,000 in the 6th and 5th centuries BC, on average three or four slaves per household. In the 5th century BC,

It is difficult to estimate the number of slaves in ancient Greece, given the lack of a precise census and variations in definitions during that era. It seems certain that Athens had the largest slave population, with as many as 80,000 in the 6th and 5th centuries BC, on average three or four slaves per household. In the 5th century BC,

Athenian slaves were the property of their master (or of the state), who could dispose of them as he saw fit. He could give, sell, rent, or bequeath them. A slave could have a spouse and child, but the slave family was not recognized by the state, and the master could scatter the family members at any time.Garlan, p.47. Slaves had fewer judicial rights than citizens and were represented by their masters in all judicial proceedings. A misdemeanor that would result in a fine for the free man would result in a flogging for the slave; the ratio seems to have been one lash for one drachma.Carlier, p.203. With several minor exceptions, the testimony of a slave was not admissible except under torture. Slaves were tortured in trials because they often remained loyal to their masters. A famous example of a trusty slave was

Athenian slaves were the property of their master (or of the state), who could dispose of them as he saw fit. He could give, sell, rent, or bequeath them. A slave could have a spouse and child, but the slave family was not recognized by the state, and the master could scatter the family members at any time.Garlan, p.47. Slaves had fewer judicial rights than citizens and were represented by their masters in all judicial proceedings. A misdemeanor that would result in a fine for the free man would result in a flogging for the slave; the ratio seems to have been one lash for one drachma.Carlier, p.203. With several minor exceptions, the testimony of a slave was not admissible except under torture. Slaves were tortured in trials because they often remained loyal to their masters. A famous example of a trusty slave was  However, slaves did belong to their master's household. A newly bought slave was welcomed with nuts and fruits, just like a newly-wed wife. Slaves took part in most of the civic and family cults; they were expressly invited to join the banquet of the ''Choes'', the second day of the

However, slaves did belong to their master's household. A newly bought slave was welcomed with nuts and fruits, just like a newly-wed wife. Slaves took part in most of the civic and family cults; they were expressly invited to join the banquet of the ''Choes'', the second day of the

In

In

Very few authors of antiquity call slavery into question. To

Very few authors of antiquity call slavery into question. To

Slavery in Greek antiquity has long been an object of

Slavery in Greek antiquity has long been an object of

The Slave Systems of Greek and Roman Antiquity

'. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, 1955. Specific studies * Brulé, P. (1978b). ''La Piraterie crétoise hellénistique'', Belles Lettres, 1978. * Brulé, P. and Oulhen, J. (dir.). ''Esclavage, guerre, économie en Grèce ancienne. Hommages à Yvon Garlan''. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, "History" series, 1997. * Ducrey, P. ''Le traitement des prisonniers de guerre en Grèce ancienne. Des origines à la conquête romaine''. Paris: De Boccard, 1968. * Foucart, P. "Mémoire sur l'affranchissement des esclaves par forme de vente à une divinité d'après les inscriptions de Delphes", ''Archives des missions scientifiques et littéraires'', 2nd series, vol.2 (1865), pp. 375–424. * Gabrielsen, V. "La piraterie et le commerce des esclaves", in E. Erskine (ed.), ''Le Monde hellénistique. Espaces, sociétés, cultures. 323-31 av. J.-C.''. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2004, pp. 495–511. * Hunt, P. ''Slaves, Warfare, and Ideology in the Greek Historians''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. * Ormerod, H.A. ''Piracy in the Ancient World''. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1924. * Thalmann, William G. 1998. ''The Swineherd and the Bow: Representations of Class in the “Odyssey.”'' Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press.

GIREA

– The International Group for Research on Slavery in Antiquity

a

Nomoi

on th

at ''attalus.org''

– subject index on slavery and related topics, by author

– free library

Greek Manumission Project

{{DEFAULTSORT:Slavery In Ancient Greece Labor history

Slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

was an accepted practice in ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

, as in other societies of the time. Some Ancient Greek writers (including, most notably, Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

) described slavery as natural and even necessary.Ernest Barker (1906) The Political thought of Plato and Aristotle"The slave is a necessary instrument, like other kinds of wealth, for the moral life." p.313 This paradigm was notably questioned in

Socratic dialogues

Socratic dialogue ( grc, Σωκρατικὸς λόγος) is a genre of literary prose developed in Greece at the turn of the fourth century BC. The earliest ones are preserved in the works of Plato and Xenophon and all involve Socrates as the p ...

; the Stoics

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asserting that th ...

produced the first recorded condemnation of slavery.J.M. Roberts. ''The New Penguin History of the World''. p.176–177, 223.

The principal use of slaves was in agriculture, but they were also used in stone quarries or mines, and as domestic servants. Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

had the largest slave population, with as many as 80,000 in the 5th and 6th centuries BC, with an average of three or four slaves per household, except in poor families. Slaves were legally prohibited from participating in politics, which was reserved for citizens.

Modern historiographical

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians hav ...

practice distinguishes between chattel slavery (personal possession, where the slave was regarded as a piece of property as opposed to a mobile member of society) versus land-bonded groups such as the penestae of Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thes ...

or the Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

n helots

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their ex ...

, who were more like medieval serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

(an enhancement to real estate). The chattel slave is an individual deprived of liberty and forced to submit to an owner, who may buy, sell, or lease them like any other chattel.

The academic study of slavery in ancient Greece is beset by significant methodological problems. Documentation is disjointed and very fragmented, focusing primarily on the city-state of Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

. No treatises are specifically devoted to the subject, and jurisprudence was interested in slavery only as much as it provided a source of revenue. Greek comedies and tragedies

Tragedy (from the grc-gre, τραγῳδία, ''tragōidia'', ''tragōidia'') is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful events that befall a main character. Traditionally, the intention of tragedy ...

represented stereotypes, while iconography

Iconography, as a branch of art history, studies the identification, description and interpretation of the content of images: the subjects depicted, the particular compositions and details used to do so, and other elements that are distinct fro ...

made no substantial differentiation between slaves and craftsmen

Craftsman may refer to:

A profession

*Artisan, a skilled manual worker who makes items that may be functional or strictly decorative

* Master craftsman, an artisan who has achieved such a standard that he may establish his own workshop and take ...

.

Terminology

The ancient Greeks had several words to indicate slaves, which leads to textual ambiguity when they are studied out of their proper context. In

The ancient Greeks had several words to indicate slaves, which leads to textual ambiguity when they are studied out of their proper context. In Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

and Theognis of Megara

Theognis of Megara ( grc-gre, Θέογνις ὁ Μεγαρεύς, ''Théognis ho Megareús'') was a Greek lyric poet active in approximately the sixth century BC. The work attributed to him consists of gnomic poetry quite typical of the time, f ...

, the slave was called (''dmōs''). The term has a general meaning but refers particularly to war prisoners taken as booty

Booty may refer to:

Music

*Booty music (also known as Miami bass or booty bass), a subgenre of hip hop

* "Booty" (Jennifer Lopez song), 2014

*Booty (Blac Youngsta song), 2017

* Booty (C. Tangana and Becky G song), 2018

*"Booty", a 1993 song by G ...

(in other words, property). During the classical period, the Greeks frequently used (''andrapodon''), (literally, "one with the feet of a man") as opposed to (''tetrapodon''), "quadruped" or livestock. The most common word for slaves is (''doulos''), used in opposition to "free man" (, ''eleútheros''); an earlier form of the former appears in Mycenaean inscriptions as ''do-e-ro'', "male slave" (or "servant", "bondman"; Linear B: ), or ''do-e-ra'', "female slave" (or "maid-servant", "bondwoman"). The verb

A verb () is a word (part of speech) that in syntax generally conveys an action (''bring'', ''read'', ''walk'', ''run'', ''learn''), an occurrence (''happen'', ''become''), or a state of being (''be'', ''exist'', ''stand''). In the usual descri ...

(which survives in Modern Greek, meaning "work") can be used metaphorically for other forms of dominion, as of one city over another or parents over their children. Finally, the term (''oiketēs'') was used, as meaning "one who lives in house", referring to household servants.

Other terms used to indicate slaves were less precise and required context:

:* (''therapōn'') – At the time of Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, the word meant "companion" (Patroclus

In Greek mythology, as recorded in Homer's ''Iliad'', Patroclus (pronunciation variable but generally ; grc, Πάτροκλος, Pátroklos, glory of the father) was a childhood friend, close wartime companion, and the presumed (by some later a ...

was referred to as the ''therapōn'' of Achilles

In Greek mythology, Achilles ( ) or Achilleus ( grc-gre, Ἀχιλλεύς) was a hero of the Trojan War, the greatest of all the Greek warriors, and the central character of Homer's ''Iliad''. He was the son of the Nereid Thetis and Peleus, k ...

and Meriones that of Idomeneus

In Greek mythology, Idomeneus (; el, Ἰδομενεύς) was a Cretan king and commander who led the Cretan armies to the Trojan War, in eighty black ships. He was also one of the suitors of Helen, as well as a comrade of the Telamonian Ajax. ...

); but during the classical age, it meant "servant".

:* (''akolouthos'') – literally, "the follower" or "the one who accompanies". Also, the diminutive

A diminutive is a root word that has been modified to convey a slighter degree of its root meaning, either to convey the smallness of the object or quality named, or to convey a sense of intimacy or endearment. A (abbreviated ) is a word-formati ...

, used for page

Page most commonly refers to:

* Page (paper), one side of a leaf of paper, as in a book

Page, PAGE, pages, or paging may also refer to:

Roles

* Page (assistance occupation), a professional occupation

* Page (servant), traditionally a young m ...

boys.

:* (''pais'') – literally "child", used in the same way as "houseboy

A houseboy (alternatively spelled as ''houseboi'') was a term which referred to a typically male domestic worker or personal assistant who performed cleaning and other forms of personal chores. The term has a record of being used in the British ...

", also used in a derogatory way to call adult slaves.

:* (''sōma'') – literally "body", used in the context of emancipation.

Pre-classical Greece

Slaves were present through the

Slaves were present through the Mycenaean civilization

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age in Ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750 to 1050 BC.. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainland ...

, as documented in numerous tablets unearthed in Pylos

Pylos (, ; el, Πύλος), historically also known as Navarino, is a town and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part of the municipality Pylos-Nestoras, of which it is th ...

140. Two legal categories can be distinguished: "slaves (εοιο)"Garlan, p. 32. and "slaves of the god (θεοιο)", the god in this case probably being Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a ch ...

. Slaves of the god are always mentioned by name and own their own land; their legal status is close to that of freemen. The nature and origin of their bond to the divinity is unclear. The names of common slaves show that some of them came from Kythera

Kythira (, ; el, Κύθηρα, , also transliterated as Cythera, Kythera and Kithira) is an island in Greece lying opposite the south-eastern tip of the Peloponnese peninsula. It is traditionally listed as one of the seven main Ionian Islands, ...

, Chios

Chios (; el, Χίος, Chíos , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greek island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. Chios is notable for its exports of mastic ...

, Lemnos

Lemnos or Limnos ( el, Λήμνος; grc, Λῆμνος) is a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos regional unit, which is part of the North Aegean region. The p ...

, or Halicarnassus

Halicarnassus (; grc, Ἁλικαρνᾱσσός ''Halikarnāssós'' or ''Alikarnāssós''; tr, Halikarnas; Carian: 𐊠𐊣𐊫𐊰 𐊴𐊠𐊥𐊵𐊫𐊰 ''alos k̂arnos'') was an ancient Greek city in Caria, in Anatolia. It was located i ...

and were probably enslaved as a result of piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

. The tablets indicate that unions between slaves and freemen were common and that slaves could work and own land. It appears that the major division in Mycenaean civilization was not between a free individual and a slave but rather if the individual was in the palace or not.

There is no continuity between the Mycenaean era and the time of Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, where social structures reflected those of the Greek dark ages

The term Greek Dark Ages refers to the period of Greek history from the end of the Mycenaean palatial civilization, around 1100 BC, to the beginning of the Archaic age, around 750 BC. Archaeological evidence shows a widespread collaps ...

. The terminology differs: the slave is no longer ''do-e-ro'' (doulos) but ''dmōs''. In the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odysse ...

'', slaves are mainly women taken as booty of war, while men were either ransomed or killed on the battlefield.

In the ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major Ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek Epic poetry, epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by moder ...

'', the slaves also seem to be mostly women. These slaves were servants and sometimes are concubines.

There were some male slaves, especially in the ''Odyssey'', a prime example being the swineherd

A swineherd is a person who raises and herds pigs as livestock.

Swineherds in literature

* In the New Testament are mentioned shepherd of pigs, mentioned in the Pig (Gadarene) the story shows Jesus exorcising a demon or demons from a man and a ...

Eumaeus

In Greek mythology, Eumaeus (; Ancient Greek: Εὔμαιος ''Eumaios'' means 'searching well') was Odysseus' swineherd and friend. His father, Ktesios son of Ormenos was king of an island called Syra (present-day Syros in the Greek islands o ...

. The slave was distinctive in being a member of the core part of the ''oikos'' ("family unit", "household"): Laertes

In Greek mythology, Laertes (; grc, Λαέρτης, Laértēs ; also spelled Laërtes) was the king of the Cephallenians, an ethnic group who lived both on the Ionian islands and on the mainland, which he presumably inherited from his father A ...

eats and drinks with his servants; in the winter, he sleeps in their company. Eumaeus, the "divine" swineherd, bears the same Homeric epithet A characteristic of Homer's style is the use of epithets, as in "rosy-fingered" Dawn or "swift-footed" Achilles. Epithets are used because of the constraints of the dactylic hexameter (i.e., it is convenient to have a stockpile of metrically fitting ...

as the Greek heroes.Garlan, p.43. Slavery remained, however, a disgrace: Eumaeus declares, "Zeus, of the far-borne voice, takes away the half of a man's virtue, when the day of slavery comes upon him".

It is difficult to determine when slave trading began in the archaic period. In ''Works and Days

''Works and Days'' ( grc, Ἔργα καὶ Ἡμέραι, Érga kaì Hēmérai)The ''Works and Days'' is sometimes called by the Latin translation of the title, ''Opera et Dies''. Common abbreviations are ''WD'' and ''Op''. for ''Opera''. is a ...

'' (8th century BCE), Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

owns numerous ''dmōes'' although their exact status is unclear. The presence of ''douloi'' is confirmed by lyric poets such as Archilochus

Archilochus (; grc-gre, Ἀρχίλοχος ''Arkhilokhos''; c. 680 – c. 645 BC) was a Greek lyric poet of the Archaic period from the island of Paros. He is celebrated for his versatile and innovative use of poetic meters, and is the ea ...

or Theognis of Megara

Theognis of Megara ( grc-gre, Θέογνις ὁ Μεγαρεύς, ''Théognis ho Megareús'') was a Greek lyric poet active in approximately the sixth century BC. The work attributed to him consists of gnomic poetry quite typical of the time, f ...

. According to epigraphic evidence, the homicide law of Draco

Draco is the Latin word for serpent or dragon.

Draco or Drako may also refer to:

People

* Draco (lawgiver) (from Greek: Δράκων; 7th century BC), the first lawgiver of ancient Athens, Greece, from whom the term ''draconian'' is derived

* ...

() mentioned slaves. According to Plutarch, Solon

Solon ( grc-gre, Σόλων; BC) was an Athenian statesman, constitutional lawmaker and poet. He is remembered particularly for his efforts to legislate against political, economic and moral decline in Archaic Athens.Aristotle ''Politics'' ...

() forbade slaves from practising gymnastics and pederasty. By the end of the period, references become more common. Slavery becomes prevalent at the very moment when Solon establishes the basis for Athenian democracy. Classical scholar Moses Finley

Sir Moses Israel Finley, FBA (born Finkelstein; 20 May 1912 – 23 June 1986) was an American-born British academic and classical scholar. His prosecution by the United States Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security during the 1950s, resulted ...

likewise remarks that Chios, which, according to Theopompus

Theopompus ( grc-gre, Θεόπομπος, ''Theópompos''; c. 380 BCc. 315 BC) was an ancient Greek historian and rhetorician.

Biography

Theopompus was born on the Aegean island of Chios. In early youth, he seems to have spent some time at Athen ...

, was the first city to organize a slave trade, also enjoyed an early democratic process (in the 6th century BC). He concludes that "one aspect of Greek history, in short, is the advance hand in hand, of freedom ''and'' slavery."

Economic role

All activities were open to slaves with the exception of politics. For the Greeks, politics was the only occupation worthy of a citizen, the rest being relegated wherever possible to non-citizens. It was status that was of importance, not occupation.

The principal use of slavery was in

All activities were open to slaves with the exception of politics. For the Greeks, politics was the only occupation worthy of a citizen, the rest being relegated wherever possible to non-citizens. It was status that was of importance, not occupation.

The principal use of slavery was in agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to ...

, the foundation of the Greek economy. Some small landowners might own one slave, or even two. An abundant literature of manuals for landowners (such as the ''Economy'' of Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, wikt:Ξενοφῶν, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Anci ...

or that of Pseudo-Aristotle Pseudo-Aristotle is a general cognomen for authors of philosophical or medical treatises who attributed their work to the Greek philosopher Aristotle, or whose work was later attributed to him by others. Such falsely attributed works are known as ps ...

) confirms the presence of dozens of slaves on the larger estates; they could be common labourers or foremen. The extent to which slaves were used as a labour force in farming is disputed. It is certain that rural slavery was very common in Athens, and that ancient Greece did not have the immense slave populations found on the Roman ''latifundia

A ''latifundium'' (Latin: ''latus'', "spacious" and ''fundus'', "farm, estate") is a very extensive parcel of privately owned land. The latifundia of Roman history were great landed estates specializing in agriculture destined for export: grain, o ...

''.

Slave labour was prevalent in mines and quarries

A quarry is a type of open-pit mine in which dimension stone, rock, construction aggregate, riprap, sand, gravel, or slate is excavated from the ground. The operation of quarries is regulated in some jurisdictions to reduce their environ ...

, which had large slave populations, often leased out by rich private citizens. The strategos

''Strategos'', plural ''strategoi'', Linguistic Latinisation, Latinized ''strategus'', ( el, στρατηγός, pl. στρατηγοί; Doric Greek: στραταγός, ''stratagos''; meaning "army leader") is used in Greek language, Greek to ...

Nicias

Nicias (; Νικίας ''Nikias''; c. 470–413 BC) was an Athenian politician and general during the period of the Peloponnesian War. Nicias was a member of the Athenian aristocracy and had inherited a large fortune from his father, which was inve ...

leased a thousand slaves to the silver mines of Laurium

Laurium or Lavrio ( ell, Λαύριο; grc, Λαύρειον (later ); before early 11th century BC: Θορικός ''Thorikos''; from Middle Ages until 1908: Εργαστήρια ''Ergastiria'') is a town in southeastern part of Attica, Greec ...

in Attica

Attica ( el, Αττική, Ancient Greek ''Attikḗ'' or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the city of Athens, the capital of Greece and its countryside. It is a peninsula projecting into the Aegean Se ...

; Hipponicos, 600; and Philomidès, 300. Xenophon''Poroi'' (''On Revenues''), 4. indicates that they received one obolus

The obol ( grc-gre, , ''obolos'', also ὀβελός (''obelós''), ὀβελλός (''obellós''), ὀδελός (''odelós''). "nail, metal spit"; la, obolus) was a form of ancient Greek currency and weight.

Currency

Obols were u ...

per slave per day, amounting to 60 drachma

The drachma ( el, δραχμή , ; pl. ''drachmae'' or ''drachmas'') was the currency used in Greece during several periods in its history:

# An ancient Greek currency unit issued by many Greek city states during a period of ten centuries, fro ...

s per year. This was one of the most prized investments for Athenians. The number of slaves working in the Laurium mines or in the mills processing ore has been estimated at 30,000.Lauffer, p.916. Xenophon suggested that the city buy a large number of slaves, up to three state slaves per citizen, so that their leasing would assure the upkeep of all the citizens.

Slaves were also used as craftsmen and tradesperson

A tradesman, tradeswoman, or tradesperson is a skilled worker that specializes in a particular trade (occupation or field of work). Tradesmen usually have work experience, on-the-job training, and often formal vocational education in contrast to ...

s. As in agriculture, they were used for labour that was beyond the capability of the family. The slave population was greatest in workshops: the shield factory of Lysias

Lysias (; el, Λυσίας; c. 445 – c. 380 BC) was a logographer (speech writer) in Ancient Greece. He was one of the ten Attic orators included in the "Alexandrian Canon" compiled by Aristophanes of Byzantium and Aristarchus of Samothrace i ...

employed 120 slaves, and the father of Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; el, Δημοσθένης, translit=Dēmosthénēs; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual prow ...

owned 32 cutlers and 20 bedmakers.

Ownership of domestic slaves was common, the domestic male slave's main role being to stand in for his master at his trade and to accompany him on trips. In time of war he was batman

Batman is a superhero appearing in American comic books published by DC Comics. The character was created by artist Bob Kane and writer Bill Finger, and debuted in Detective Comics 27, the 27th issue of the comic book ''Detective Comics'' on ...

to the hoplite

Hoplites ( ) ( grc, ὁπλίτης : hoplítēs) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Polis, city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with ...

. The female slave carried out domestic tasks, in particular bread baking and textile making.

Demographics

Population

It is difficult to estimate the number of slaves in ancient Greece, given the lack of a precise census and variations in definitions during that era. It seems certain that Athens had the largest slave population, with as many as 80,000 in the 6th and 5th centuries BC, on average three or four slaves per household. In the 5th century BC,

It is difficult to estimate the number of slaves in ancient Greece, given the lack of a precise census and variations in definitions during that era. It seems certain that Athens had the largest slave population, with as many as 80,000 in the 6th and 5th centuries BC, on average three or four slaves per household. In the 5th century BC, Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of "scientifi ...

remarked on the desertion of 20,890 slaves during the war of Decelea, mostly tradesmen. The lowest estimate, of 20,000 slaves, during the time of Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; el, Δημοσθένης, translit=Dēmosthénēs; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual prow ...

, corresponds to one slave per family. Between 317 BC and 307 BC, the tyrant Demetrius Phalereus

Demetrius of Phalerum (also Demetrius of Phaleron or Demetrius Phalereus; grc-gre, Δημήτριος ὁ Φαληρεύς; c. 350 – c. 280 BC) was an Athenian orator originally from Phalerum, an ancient port of Athens. A student of Theophrast ...

ordered a general census of Attica, which arrived at the following figures: 21,000 citizens, 10,000 metic

In ancient Greece, a metic (Ancient Greek: , : from , , indicating change, and , 'dwelling') was a foreign resident of Athens, one who did not have citizen rights in their Greek city-state (''polis'') of residence.

Origin

The history of foreign m ...

s and 400,000 slaves. However, some researchers doubt the accuracy of the figure, asserting that thirteen slaves per free man appear unlikely in a state where a dozen slaves were a sign of wealth, nor is the population stated consistent with the known figures for bread production and import. The orator Hypereides

Hypereides or Hyperides ( grc-gre, Ὑπερείδης, ''Hypereidēs''; c. 390 – 322 BC; English pronunciation with the stress variably on the penultimate or antepenultimate syllable) was an Athenian logographer (speech writer). He was one ...

, in his ''Against Areistogiton'', recalls that the effort to enlist 15,000 male slaves of military age led to the defeat of the Southern Greeks at the Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC)

The Battle of Chaeronea was fought in 338 BC, near the city of Chaeronea in Boeotia, between Macedonia under Philip II and an alliance of city-states led by Athens and Thebes. The battle was the culmination of Philip's final campaigns in 3 ...

, which corresponds to the figures of Ctesicles Ctesicles ( grc, Κτησικλῆς) was the author of a chronological work (Chronika or Chronoi), of which two fragments are preserved in Athenaeus.

Ctesicles was also a sculptor, who made a statue at Samos and an Athenian generalLysias

Lysias ...

.

According to the literature, it appears that the majority of free Athenians owned at least one slave. Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme

In Ancient Greece, a deme or ( grc, δῆμος, plural: demoi, δημοι) was a suburb or a subdivision of Athens and other city-states ...

, in ''Plutus

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Plutus (; grc-gre, Πλοῦτος, Ploûtos, wealth) is the god and the personification of wealth, and the son of the goddess of agriculture Demeter and the mortal Iasion.

Family

Plutus is most commonl ...

'', portrays poor peasants who have several slaves; Aristotle defines a house as containing freemen and slaves. Conversely, not owning even one slave was a clear sign of poverty. In the celebrated discourse of Lysias

Lysias (; el, Λυσίας; c. 445 – c. 380 BC) was a logographer (speech writer) in Ancient Greece. He was one of the ten Attic orators included in the "Alexandrian Canon" compiled by Aristophanes of Byzantium and Aristarchus of Samothrace i ...

''For the Invalid'', a cripple pleading for a pension explains "my income is very small and now I'm required to do these things myself and do not even have the means to purchase a slave who can do these things for me." However, the huge individual slave holdings of the wealthiest Romans were unknown in ancient Greece. When Athenaeus cites the case of Mnason

Mnason ( gr, μνασωνι τινι κυπριω) was a first-century Cypriot Christian, who is mentioned in chapter 21 of the Acts of the Apostles as offering hospitality to Luke the evangelist, Paul the apostle and their companions, when the ...

, a friend of Aristotle and owner of a thousand slaves, this appears to be exceptional. Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, owner of five slaves at the time of his death, describes the very rich as owning fifty slaves.

Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of "scientifi ...

estimates that the isle of Chios

Chios (; el, Χίος, Chíos , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greek island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. Chios is notable for its exports of mastic ...

had proportionally the largest number of slaves.

Sources of supply

There were four primary sources of slaves: war, in which the defeated would become slaves to the victorious unless a more objective outcome was reached;piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

(at sea); banditry (on land); and international trade.

War

By the rules of war of the period, the victor possessed absolute rights over the vanquished, whether they were soldiers or not. Enslavement, while not systematic, was common practice.Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of "scientifi ...

recalls that 7,000 inhabitants of Hyccara

Carini ( la, Hyccara or Hyccarum, grc, Ὕκαρα and Ὕκαρον) is a city and ''comune'' in the Metropolitan City of Palermo, Sicily, by rail west-northwest of Palermo. It has a population of 37,752.

History

Timaeus (historian), Timae ...

in Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

were taken prisoner by Nicias

Nicias (; Νικίας ''Nikias''; c. 470–413 BC) was an Athenian politician and general during the period of the Peloponnesian War. Nicias was a member of the Athenian aristocracy and had inherited a large fortune from his father, which was inve ...

and sold for 120 talents in the neighbouring village of Catania

Catania (, , Sicilian and ) is the second largest municipality in Sicily, after Palermo. Despite its reputation as the second city of the island, Catania is the largest Sicilian conurbation, among the largest in Italy, as evidenced also by ...

. Likewise in 348 BC the population of Olynthus

Olynthus ( grc, Ὄλυνθος ''Olynthos'', named for the ὄλυνθος ''olunthos'', "the fruit of the wild fig tree") was an ancient city of Chalcidice

Chalkidiki (; el, Χαλκιδική , also spelled Halkidiki, is a peninsula and ...

was reduced to slavery, as was that of Thebes in 335 BC by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

and that of Mantineia

Mantineia (also Mantinea ; el, Μαντίνεια; also Koine Greek ''Antigoneia'') was a city in ancient Arcadia, Greece, which was the site of two significant battles in Classical Greek history.

In modern times it is a former municipality in ...

by the Achaean League

The Achaean League (Greek: , ''Koinon ton Akhaion'' "League of Achaeans") was a Hellenistic-era confederation of Greek city states on the northern and central Peloponnese. The league was named after the region of Achaea in the northwestern Pel ...

.Garlan, p. 57.

The existence of Greek slaves was a constant source of discomfort for Greek citizens. The enslavement of cities was also a controversial practice. Some generals refused, such as the Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

ns Agesilaus II

Agesilaus II (; grc-gre, Ἀγησίλαος ; c. 442 – 358 BC) was king of Sparta from c. 399 to 358 BC. Generally considered the most important king in the history of Sparta, Agesilaus was the main actor during the period of Spartan hegemony ...

and Callicratidas Callicratidas ( el, Καλλικρατίδας) was a Spartan navarch during the Peloponnesian War. He belonged to the mothax class so he was not a Spartiate, despite his status he had risen to prominence. In 406 BC, he was sent to the Aegean to ta ...

. Some cities passed accords to forbid the practice: in the middle of the 3rd century BC, Miletus

Miletus (; gr, Μῑ́λητος, Mī́lētos; Hittite transcription ''Millawanda'' or ''Milawata'' (exonyms); la, Mīlētus; tr, Milet) was an ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia, near the mouth of the Maeander River in a ...

agreed not to reduce any free Knossian to slavery, and vice versa. Conversely, the emancipation by ransom of a city that had been entirely reduced to slavery carried great prestige: Cassander

Cassander ( el, Κάσσανδρος ; c. 355 BC – 297 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia from 305 BC until 297 BC, and ''de facto'' ruler of southern Greece from 317 BC until his death.

A son of Antipater and a cont ...

, in 316 BC, restored Thebes. Before him, Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 382 – 21 October 336 BC) was the king ('' basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

enslaved and then emancipated Stageira

Stagira (), Stagirus (), or Stageira ( el, Στάγειρα or ) was an ancient Greek city located near the eastern coast of the peninsula of Chalkidice, which is now part of the Greek province of Central Macedonia. It is chiefly known for bei ...

.

Piracy and banditry

Piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

and banditry provided a significant and consistent supply of slaves, though the significance of this source varied according to era and region. Pirates and brigands would demand ransom whenever the status of their catch warranted it. Whenever ransom was not paid or not warranted, captives would be sold to a trafficker. In certain areas, piracy was practically a national specialty, described by Thucydides as "the old-fashioned" way of life. Such was the case in Acarnania

Acarnania ( el, Ἀκαρνανία) is a region of west-central Greece that lies along the Ionian Sea, west of Aetolia, with the Achelous River for a boundary, and north of the gulf of Calydon, which is the entrance to the Gulf of Corinth. Today i ...

, Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

, and Aetolia

Aetolia ( el, Αἰτωλία, Aἰtōlía) is a mountainous region of Greece on the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth, forming the eastern part of the modern regional units of Greece, regional unit of Aetolia-Acarnania.

Geography

The Achelous ...

. Outside of Greece, this was also the case with Illyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria (; grc, Ἰλλυρία, ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; la, Illyria, ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyr ...

ns, Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

ns, and Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, rou ...

. During the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 3 ...

, Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern coa ...

ns and the mountain peoples from the coasts of Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

could also be added to the list. Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

explains the popularity of the practice among the Cilicians by its profitability; Delos

The island of Delos (; el, Δήλος ; Attic: , Doric: ), near Mykonos, near the centre of the Cyclades archipelago, is one of the most important mythological, historical, and archaeological sites in Greece. The excavations in the island are ...

, not far away, allowed for "moving myriad slaves daily". The growing influence of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kin ...

, a large consumer of slaves, led to development of the market and an aggravation of piracy. In the 1st century BC, however, the Romans largely eradicated piracy to protect the Mediterranean trade routes.

Slave trade

There was slave trade between kingdoms and states of the wider region. The fragmentary list of slaves confiscated from the property of the mutilators of the ''Herma

A herma ( grc, ἑρμῆς, pl. ''hermai''), commonly herm in English, is a sculpture with a head and perhaps a torso above a plain, usually squared lower section, on which male genitals may also be carved at the appropriate height. Hermae we ...

i'' mentions 32 slaves whose origins have been ascertained: 13 came from Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

, 7 from Caria

Caria (; from Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; tr, Karya) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Ionians, Ionian and Dorians, Dorian Greeks colonized the west of i ...

, and the others came from Cappadocia

Cappadocia or Capadocia (; tr, Kapadokya), is a historical region in Central Anatolia, Turkey. It largely is in the provinces Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde.

According to Herodotus, in the time of the Ionian Revo ...

, Scythia

Scythia (Scythian: ; Old Persian: ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) or Scythica (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ), also known as Pontic Scythia, was a kingdom created by the Scythians during the 6th to 3rd centuries BC in the Pontic–Caspian steppe.

His ...

, Phrygia

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; grc, Φρυγία, ''Phrygía'' ) was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River. After its conquest, it became a region of the great empires ...

, Lydia

Lydia (Lydian language, Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the mod ...

, Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, Ilyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria (; grc, Ἰλλυρία, ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; la, Illyria, ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyr ...

, Macedon

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by ...

, and Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

. Local professionals sold their own people to Greek slave merchants. The principal centres of the slave trade appear to have been Ephesus

Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἔφεσος, Éphesos; tr, Efes; may ultimately derive from hit, 𒀀𒉺𒊭, Apaša) was a city in ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in t ...

, Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' cont ...

, and even faraway Tanais

Tanais ( el, Τάναϊς ''Tánaïs''; russian: Танаис) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek city in the Don River (Russia), Don river delta, called the Maeotian Swamp, Maeotian marshes in classical antiquity. It was a bishopric as Tana ...

at the mouth of the Don

Don, don or DON and variants may refer to:

Places

*County Donegal, Ireland, Chapman code DON

*Don (river), a river in European Russia

*Don River (disambiguation), several other rivers with the name

*Don, Benin, a town in Benin

*Don, Dang, a vill ...

. Some "barbarian" slaves were victims of war or localised piracy, but others were sold by their parents.

There is a lack of direct evidence of slave traffic, but corroborating evidence exists. Firstly, certain nationalities are consistently and significantly represented in the slave population, such as the corps of Scythian archers employed by Athens as a police force—originally 300, but eventually nearly a thousand. Secondly, the names given to slaves in the comedies

Comedy is a genre of fiction that consists of discourses or works intended to be humorous or amusing by inducing laughter, especially in theatre, film, stand-up comedy, television, radio, books, or any other entertainment medium. The term o ...

often had a geographical link; thus ''Thratta'', used by Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme

In Ancient Greece, a deme or ( grc, δῆμος, plural: demoi, δημοι) was a suburb or a subdivision of Athens and other city-states ...

in ''The Wasps

''The Wasps'' ( grc-x-classical, Σφῆκες, translit=Sphēkes) is the fourth in chronological order of the eleven surviving plays by Aristophanes. It was produced at the Lenaia festival in 422 BC, during Athens' short-lived respite from the ...

'', ''The Acharnians

''The Acharnians'' or ''Acharnians'' (Ancient Greek: ''Akharneîs''; Attic: ) is the third play — and the earliest of the eleven surviving plays — by the Athenian playwright Aristophanes. It was produced in 425 BC on behalf of the young drama ...

'', and ''Peace

Peace is a concept of societal friendship and harmony in the absence of hostility and violence. In a social sense, peace is commonly used to mean a lack of conflict (such as war) and freedom from fear of violence between individuals or groups. ...

'', simply meant ''a Thracian woman''. Finally, the nationality of a slave was a significant criterion for major purchasers: Ancient practice was avoid a concentration of too many slaves of the same ethnic origin in the same place, in order to limit the risk of revolt. It is also probable that, as with the Romans, certain nationalities were considered more productive as slaves than others.

The price of slaves varied in accordance with their ability. Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, wikt:Ξενοφῶν, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Anci ...

valued a Laurion miner at 180 drachma

The drachma ( el, δραχμή , ; pl. ''drachmae'' or ''drachmas'') was the currency used in Greece during several periods in its history:

# An ancient Greek currency unit issued by many Greek city states during a period of ten centuries, fro ...

s; while a workman at major works was paid one drachma

The drachma ( el, δραχμή , ; pl. ''drachmae'' or ''drachmas'') was the currency used in Greece during several periods in its history:

# An ancient Greek currency unit issued by many Greek city states during a period of ten centuries, fro ...

per day. Demosthenes' father's cutlers were valued at 500 to 600 drachma

The drachma ( el, δραχμή , ; pl. ''drachmae'' or ''drachmas'') was the currency used in Greece during several periods in its history:

# An ancient Greek currency unit issued by many Greek city states during a period of ten centuries, fro ...

s each. Price was also a function of the quantity of slaves available; in the 4th century BC they were abundant and it was thus a buyer's market. A tax on sale revenues was levied by the market cities. For instance, a large helot market was organized during the festivities at the temple of Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

at Actium

Actium or Aktion ( grc, Ἄκτιον) was a town on a promontory in ancient Acarnania at the entrance of the Ambraciot Gulf, off which Octavian gained his celebrated victory, the Battle of Actium, over Antony and Cleopatra, on September 2, 31& ...

. The Acarnanian League, which was in charge of the logistics, received half of the tax proceeds, the other half going to the city of Anactorion, of which Actium was a part.

Buyers enjoyed a guarantee against latent defect

In the law of the sale of property (both real estate and personal property or chattels) a latent defect is a fault in the property that could not have been discovered by a reasonably thorough inspection before the sale.

The general law of the sal ...

s: The transaction could be invalidated if the purchased slave turned out to be crippled and the buyer had not been warned about it.

Status of slaves

The Greeks had many degrees of enslavement. There was a multitude of categories, ranging from free citizen to chattel slave, and including penestae orhelots

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their ex ...

, disenfranchised citizens, freedmen, bastards, and metic

In ancient Greece, a metic (Ancient Greek: , : from , , indicating change, and , 'dwelling') was a foreign resident of Athens, one who did not have citizen rights in their Greek city-state (''polis'') of residence.

Origin

The history of foreign m ...

s. The common ground was the deprivation of civic rights.

Moses Finley

Sir Moses Israel Finley, FBA (born Finkelstein; 20 May 1912 – 23 June 1986) was an American-born British academic and classical scholar. His prosecution by the United States Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security during the 1950s, resulted ...

proposed a set of criteria for different degrees of enslavement:

:* Right to own property

:* Authority over the work of another

:* Power of punishment over another

:* Legal rights and duties (liability to arrest and/or arbitrary punishment, or to litigate)

:* Familial rights and privileges (marriage, inheritance, etc.)

:* Possibility of social mobility (manumission or emancipation, access to citizen rights)

:* Religious rights and obligations

:* Military rights and obligations (military service as servant, heavy or light soldier, or sailor)

Athenian slaves

Athenian slaves were the property of their master (or of the state), who could dispose of them as he saw fit. He could give, sell, rent, or bequeath them. A slave could have a spouse and child, but the slave family was not recognized by the state, and the master could scatter the family members at any time.Garlan, p.47. Slaves had fewer judicial rights than citizens and were represented by their masters in all judicial proceedings. A misdemeanor that would result in a fine for the free man would result in a flogging for the slave; the ratio seems to have been one lash for one drachma.Carlier, p.203. With several minor exceptions, the testimony of a slave was not admissible except under torture. Slaves were tortured in trials because they often remained loyal to their masters. A famous example of a trusty slave was

Athenian slaves were the property of their master (or of the state), who could dispose of them as he saw fit. He could give, sell, rent, or bequeath them. A slave could have a spouse and child, but the slave family was not recognized by the state, and the master could scatter the family members at any time.Garlan, p.47. Slaves had fewer judicial rights than citizens and were represented by their masters in all judicial proceedings. A misdemeanor that would result in a fine for the free man would result in a flogging for the slave; the ratio seems to have been one lash for one drachma.Carlier, p.203. With several minor exceptions, the testimony of a slave was not admissible except under torture. Slaves were tortured in trials because they often remained loyal to their masters. A famous example of a trusty slave was Themistocles

Themistocles (; grc-gre, Θεμιστοκλῆς; c. 524–459 BC) was an Athenian politician and general. He was one of a new breed of non-aristocratic politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy. A ...

's Persian slave Sicinnus (the counterpart of Ephialtes of Trachis

Ephialtes (; el, Ἐφιάλτης, ''Ephialtēs''; although Herodotus spelled it as , ''Epialtes'') was the son of Eurydemus ( el, Εὐρύδημος) of Malis. He betrayed his homeland, in hope of receiving some kind of reward from the Persian ...

), who, despite his Persian origin, betrayed Xerxes and helped Athenians in the Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis ( ) was a naval battle fought between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles and the Persian Empire under King Xerxes in 480 BC. It resulted in a decisive victory for the outnumbered Greeks. The battle was ...

. Despite torture in trials, the Athenian slave was protected in an indirect way: if he was mistreated, the master could initiate litigation for damages and interest ( / ''dikē blabēs''). Conversely, a master who excessively mistreated a slave could be prosecuted by any citizen ( / ''graphē hybreōs''); this was not enacted for the sake of the slave, but to avoid violent excess ( / ''hubris

Hubris (; ), or less frequently hybris (), describes a personality quality of extreme or excessive pride or dangerous overconfidence, often in combination with (or synonymous with) arrogance. The term ''arrogance'' comes from the Latin ', mean ...

'').

Isocrates

Isocrates (; grc, Ἰσοκράτης ; 436–338 BC) was an ancient Greek rhetorician, one of the ten Attic orators. Among the most influential Greek rhetoricians of his time, Isocrates made many contributions to rhetoric and education throu ...

claimed that "not even the most worthless slave can be put to death without trial"; the master's power over his slave was not absolute. Draco

Draco is the Latin word for serpent or dragon.

Draco or Drako may also refer to:

People

* Draco (lawgiver) (from Greek: Δράκων; 7th century BC), the first lawgiver of ancient Athens, Greece, from whom the term ''draconian'' is derived

* ...

's law apparently punished with death the murder of a slave; the underlying principle was: "was the crime such that, if it became more widespread, it would do serious harm to society?" The suit that could be brought against a slave's killer was not a suit for damages, as would be the case for the killing of cattle, but a (''dikē phonikē''), demanding punishment for the religious pollution brought by the shedding of blood.Morrow, p.213. In the 4th century BC, the suspect was judged by the Palladion

In Greek and Roman mythology, the Palladium or Palladion (Greek Παλλάδιον (Palladion), Latin ''Palladium'') was a cult image of great antiquity on which the safety of Troy and later Rome was said to depend, the wooden statue (''xoanon' ...

, a court which had jurisdiction over unintentional homicide; the imposed penalty seems to have been more than a fine but less than death—maybe exile, as was the case in the murder of a Metic

In ancient Greece, a metic (Ancient Greek: , : from , , indicating change, and , 'dwelling') was a foreign resident of Athens, one who did not have citizen rights in their Greek city-state (''polis'') of residence.

Origin

The history of foreign m ...

.

However, slaves did belong to their master's household. A newly bought slave was welcomed with nuts and fruits, just like a newly-wed wife. Slaves took part in most of the civic and family cults; they were expressly invited to join the banquet of the ''Choes'', the second day of the

However, slaves did belong to their master's household. A newly bought slave was welcomed with nuts and fruits, just like a newly-wed wife. Slaves took part in most of the civic and family cults; they were expressly invited to join the banquet of the ''Choes'', the second day of the Anthesteria

The Anthesteria (; grc, Ἀνθεστήρια ) was one of the four Athenian festivals in honor of Dionysus. It was held each year from the 11th to the 13th of the month of Anthesterion, around the time of the January or February full moon. The ...

,Burkert, p.259. and were allowed initiation into the Eleusinian Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries ( el, Ἐλευσίνια Μυστήρια, Eleusínia Mystḗria) were initiations held every year for the cult of Demeter and Persephone based at the Panhellenic Sanctuary of Elefsina in ancient Greece. They are the " ...

. A slave could claim asylum in a temple or at an altar, just like a free man. The slaves shared the gods of their masters and could keep their own religious customs if any.

Slaves could not own property, but their masters often let them save up to purchase their freedom, and records survive of slaves operating businesses by themselves, making only a fixed tax-payment to their masters. Athens also had a law forbidding the striking of slaves: if a person struck what appeared to be a slave in Athens, that person might find himself hitting a fellow citizen because many citizens dressed no better. It astonished other Greeks that Athenians tolerated back-chat from slaves. Athenian slaves fought together with Athenian freemen at the battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes. The battle was the culmination of ...

, and the monuments memorialize them. It was formally decreed before the Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis ( ) was a naval battle fought between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles and the Persian Empire under King Xerxes in 480 BC. It resulted in a decisive victory for the outnumbered Greeks. The battle was ...

that the citizens should "save themselves, their women, children, and slaves".

Slaves had special sexual restrictions and obligations. For example, a slave could not engage free boys in pederastic

Pederasty or paederasty ( or ) is a sexual relationship between an adult man and a pubescent or adolescent boy. The term ''pederasty'' is primarily used to refer to historical practices of certain cultures, particularly ancient Greece and anc ...

relationships ("A slave shall not be the lover of a free boy nor follow after him, or else he shall receive fifty blows of the public lash."), and they were forbidden from the palaestra

A palaestra ( or ;

also (chiefly British) palestra; grc-gre, παλαίστρα) was any site of an ancient Greek wrestling school. Events requiring little space, such as boxing and wrestling, took place there. Palaestrae functioned both indep ...

e ("A slave shall not take exercise or anoint himself in the wrestling-schools."). Both laws are attributed to Solon

Solon ( grc-gre, Σόλων; BC) was an Athenian statesman, constitutional lawmaker and poet. He is remembered particularly for his efforts to legislate against political, economic and moral decline in Archaic Athens.Aristotle ''Politics'' ...

.

The sons of vanquished foes would be enslaved and often forced to work in male brothels, as in the case of Phaedo of Elis

Phaedo of Elis (; also ''Phaedon''; grc-gre, Φαίδων ὁ Ἠλεῖος, ''gen''.: Φαίδωνος; fl. 4th century BCE) was a Greek philosopher. A native of Elis, he was captured in war as a boy and sold into slavery. He subsequently c ...

, who at the request of Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

was bought and freed from such an enterprise by the philosopher's rich friends. On the other hand, it is attested in sources that the rape of slaves was prosecuted, at least occasionally.

Slaves in Gortyn

In

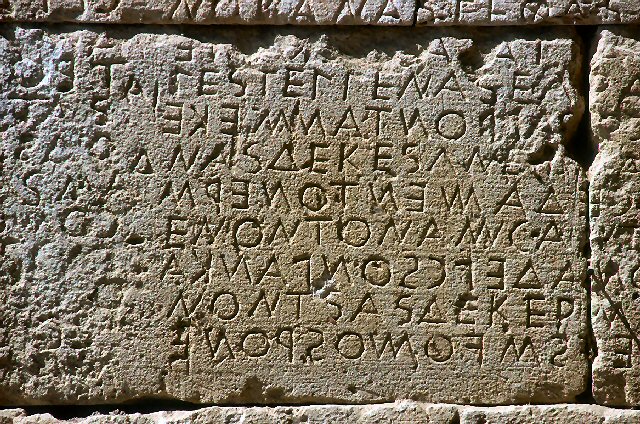

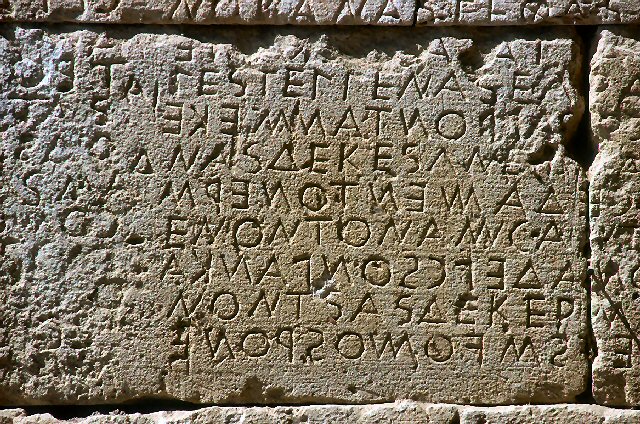

In Gortyn

Gortyn, Gortys or Gortyna ( el, Γόρτυν, , or , ) is a municipality, and an archaeological site, on the Mediterranean island of Crete away from the island's capital, Heraklion. The seat of the municipality is the village Agioi Deka. Gortyn ...

, in Crete, according to a code

In communications and information processing, code is a system of rules to convert information—such as a letter, word, sound, image, or gesture—into another form, sometimes shortened or secret, for communication through a communication ...

engraved in stone dating to the 3rd century BC, slaves (''doulos'' or ''oikeus'') found themselves in a state of great dependence. Their children belonged to the master. The master was responsible for all their offences, and, inversely, he received amends for crimes committed against his slaves by others.Finley (1997), p.200. In the Gortyn code, where all punishment was monetary, fines were doubled for slaves committing a misdemeanour or felony. Conversely, an offence committed against a slave was much less expensive than an offence committed against a free person. As an example, the rape of a free woman by a slave was punishable by a fine of 200 stater

The stater (; grc, , , statḗr, weight) was an ancient coin used in various regions of Ancient Greece, Greece. The term is also used for similar coins, imitating Greek staters, minted elsewhere in ancient Europe.

History

The stater, as a Gr ...

s (400 drachm

The dram (alternative British spelling drachm; apothecary symbol ʒ or ℨ; abbreviated dr) Earlier version first published in ''New English Dictionary'', 1897.National Institute of Standards and Technology (October 2011). Butcher, Tina; Cook, ...

s), while the rape of a non-virgin slave by another slave brought a fine of only one obolus (a sixth of a drachm).

Slaves did have the right to possess a house and livestock, which could be transmitted to descendants, as could clothing and household furnishings. Their family was recognized by law: they could marry, divorce, write a testament and inherit just like free men.

Debt slavery

Prior to its interdiction bySolon

Solon ( grc-gre, Σόλων; BC) was an Athenian statesman, constitutional lawmaker and poet. He is remembered particularly for his efforts to legislate against political, economic and moral decline in Archaic Athens.Aristotle ''Politics'' ...

, Athenians practiced debt enslavement: a citizen incapable of paying his debts became "enslaved" to the creditor. The exact nature of this dependency is a much controversial issue among modern historians: was it truly slavery or another form of bondage? However, this issue primarily concerned those peasants known as "hektēmoroi" working leased land belonging to rich landowners and unable to pay their rents. In theory, those so enslaved would be liberated when their original debts were repaid. The system was developed with variants throughout the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

and is cited in the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

.

Solon put an end to it with the / ''seisachtheia Seisachtheia ({{Lang-el, σεισάχθεια, from σείειν ''seiein'', to shake, and ἄχθος ''achthos'', burden, i.e. the relief of burdens) was a set of laws instituted by the Athenian lawmaker Solon (c. 638 BC–558 BC) in order to rect ...

'', liberation of debts, which prevented all claim to the person by the debtor and forbade the sale of free Athenians, including by themselves. Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

in his '' Constitution of the Athenians'' quotes one of Solon's poems:

And many a man whom fraud or law had soldThough much of Solon's vocabulary is that of ”traditional” slavery, servitude for debt was at least different in that the enslaved Athenian remained an Athenian, dependent on another Athenian, in his place of birth. It is this aspect which explains the great wave of discontent with slavery of the 6th century BC, which was not intended to free all slaves but only those enslaved by debt. The reforms of Solon left two exceptions: the guardian of an unmarried woman who had lost her virginity had the right to sell her as a slave, and a citizen could "expose" (abandon) unwanted newborn children.

Far from his god-built land, an outcast slave,

I brought again to Athens; yea, and some,

Exiles from home through debt’s oppressive load,

Speaking no more the dear Athenian tongue,

But wandering far and wide, I brought again;

And those that here in vilest slavery (''douleia'')

Crouched ‘neath a master’s (''despōtes'') frown, I set them free.

Manumission

The practice ofmanumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

is confirmed to have existed in Chios

Chios (; el, Χίος, Chíos , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greek island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. Chios is notable for its exports of mastic ...

from the 6th century BC. It probably dates back to an earlier period, as it was an oral procedure. Informal emancipations are also confirmed in the classical period. It was sufficient to have witnesses, who would escort the citizen to a public emancipation of his slave, either at the theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perform ...

or before a public tribunal.Garlan, p.80. This practice was outlawed in Athens in the middle of the 6th century BC to avoid public disorder.

The practice became more common in the 4th century BC and gave rise to inscriptions in stone which have been recovered from shrines such as Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), in ancient times was a sacred precinct that served as the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world. The oracle ...

and Dodona

Dodona (; Doric Greek: Δωδώνα, ''Dōdṓnā'', Ionic and Attic Greek: Δωδώνη, ''Dōdṓnē'') in Epirus in northwestern Greece was the oldest Hellenic oracle, possibly dating to the second millennium BCE according to Herodotus. Th ...

. They primarily date to the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, and the 1st century AD. Collective manumission was possible; an example is known from the 2nd century BC in the island of Thasos

Thasos or Thassos ( el, Θάσος, ''Thásos'') is a Greek island in the North Aegean Sea. It is the northernmost major Greek island, and 12th largest by area.

The island has an area of and a population of about 13,000. It forms a separate re ...

. It probably took place during a period of war as a reward for the slaves' loyalty, but in most cases the documentation deals with a voluntary act on the part of the master (predominantly male, but in the Hellenistic period also female).

The slave was often required to pay for himself an amount at least equivalent to his market value. To this end they could use their savings or take a so-called "friendly" loan ( / ''eranos'') from their master, a friend or a client like the hetaera

Hetaira (plural hetairai (), also hetaera (plural hetaerae ), ( grc, ἑταίρα, "companion", pl. , la, hetaera, pl. ) was a type of prostitute in ancient Greece, who served as an artist, entertainer and conversationalist in addition to pro ...

Neaira did.

Emancipation was often of a religious nature, where the slave was considered to be "sold" to a deity, often Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), in ancient times was a sacred precinct that served as the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world. The oracle ...

Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

, or was consecrated after his emancipation. The temple would receive a portion of the monetary transaction and would guarantee the contract. The manumission could also be entirely civil, in which case the magistrate played the role of the deity.

The slave’s freedom could be either total or partial, at the master’s whim. In the former, the emancipated slave was legally protected against all attempts at re-enslavement—for instance, on the part of the former master’s inheritors. In the latter case, the emancipated slave could be liable to a number of obligations to the former master. The most restrictive contract was the ''paramone'', a type of enslavement of limited duration during which time the master retained practically absolute rights. If a former master sued the former slave for not fulfilling a duty, however, and the slave was found innocent, the latter gained complete freedom from all duties toward the former. Some inscriptions imply a mock process of that type could be used for a master to grant his slave complete freedom in a legally binding manner.

In regard to the city, the emancipated slave was far from equal to a citizen by birth. He was liable to all types of obligations, as one can see from the proposals of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

in ''The Laws