Slavery in the Early Middle Ages on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Slavery, or the process of restricting peoples’ freedoms, was widespread within Medieval Europe. Europe and the Mediterranean world were part of a highly interconnected network of slave trading. Throughout Europe, wartime captives were commonly forced into slavery. Likewise, as European kingdoms transitioned to feudal societies, serfdom began to replace slavery as the main economic and agricultural engine. Throughout Medieval Europe, the perspectives and societal roles of enslaved peoples differed greatly, from some being restricted to agricultural labor to others being positioned as trusted political advisors.

Slavery in the early Middle Ages was initially a continuation of earlier

Slavery in the early Middle Ages was initially a continuation of earlier

(available on-line)

Eunuchs were especially valuable, and "castration houses" arose in Venice, as well as other prominent slave markets, to meet this demand. Venice was far from the only slave trading hub in Italy. Southern Italy boasted slaves from distant regions, including Greece, Bulgaria, Armenia, and Slavic regions. During the 9th and 10th centuries,

Trade and Traders in Muslim Spain: The Commercial Realignment of the Iberian Peninsula, 900–1500

'. Cambridge University Press. pp. 203–204. During the reign of Abd-ar-Rahman III (912–961), there were at first 3,750, then 6,087, and finally 13,750

The Nordic countries called their slaves ''

The Nordic countries called their slaves ''

Communities of Muslims, Christians, and Jews existed on both sides of the political divide between Muslim and Christian kingdoms in Medieval Iberia: Al-Andalus hosted Jewish and Christian communities while Christian Iberia hosted Muslim and Jewish communities. Christianity had introduced the ethos that banned the enslavement of fellow Christians, an ethos that was reinforced by the banning of the enslavement of co-religionists during the rise of Islam. Additionally, the

Communities of Muslims, Christians, and Jews existed on both sides of the political divide between Muslim and Christian kingdoms in Medieval Iberia: Al-Andalus hosted Jewish and Christian communities while Christian Iberia hosted Muslim and Jewish communities. Christianity had introduced the ethos that banned the enslavement of fellow Christians, an ethos that was reinforced by the banning of the enslavement of co-religionists during the rise of Islam. Additionally, the

in

Slavery in Poland existed on the territory of

Slavery in Poland existed on the territory of

The evidence indicates that slavery in Scandinavia was more common in southern regions, as there are fewer northern provincial laws that contain mentions of slavery. Likewise, slaves were likely numerous but consolidated under the ownership of elites as chattel labor on large farm estates.

The laws from 12th and 13th centuries describe the legal status of two categories. According to the Norwegian

The evidence indicates that slavery in Scandinavia was more common in southern regions, as there are fewer northern provincial laws that contain mentions of slavery. Likewise, slaves were likely numerous but consolidated under the ownership of elites as chattel labor on large farm estates.

The laws from 12th and 13th centuries describe the legal status of two categories. According to the Norwegian

Gen. 9:20–27

in which

* Barker, Hannah ''That Most Precious Merchandise: The Mediterranean Trade in Black Sea Slaves, 1260-1500'' (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019) * Campbell, Gwyn ''et al.'' eds. ''Women and Slavery, Vol. 1: Africa, the Indian Ocean World, and the Medieval North Atlantic'' (2007) * Dockès, Pierre. ''Medieval Slavery and Liberation'' (1989) * Frantzen, Allen J., and Douglas Moffat, eds. ''The Work of Work: Servitude, Slavery and Labor in Medieval England'' (1994) * Karras, Ruth Mazo. ''Slavery and Society in Medieval Scandinavia'' (Yale University Press, 1988) * Perry, Craig ''et al.'' eds. ''The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 2 AD500-AD1420 (Cambridge University Press, 2021) * Phillips, William D. ''Slavery from Roman Times to the Early Transatlantic Trade'' (Manchester University Press, 1985) * Rio, Alice. ''Slavery After Rome, 500-1100'' (Oxford University Press, 2017

online review

* Stuard, Susan Mosher. "Ancillary evidence for the decline of medieval slavery." ''Past & Present'' 149 (1995): 3-2

online

* Verhulst, Adriaan. "The decline of slavery and the economic expansion of the Early Middle Ages." ''Past & Present'' No. 133 (Nov., 1991), pp. 195–20

online

* Wyatt David R. ''Slaves and warriors in medieval Britain and Ireland, 800–1200'' (2009) {{Middle Ages Slavery in Europe History of slavery Medieval society

Early Middle Ages

Slavery in the early Middle Ages was initially a continuation of earlier

Slavery in the early Middle Ages was initially a continuation of earlier Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

practices from late Antiquity, and grew more widespread in the wake of the social chaos caused by the barbarian invasions

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Rom ...

of the Western Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

. With the continuation of Roman legal practices of slavery, new laws and practices concerning slavery spread throughout Europe. For example, the Welsh laws

Welsh law ( cy, Cyfraith Cymru) is an autonomous part of the English law system composed of legislation made by the Senedd.Law Society of England and Wales (2019)England and Wales: A World Jurisdiction of Choice eport(Link accessed: 16 March 2022 ...

of Hywel the Good

Hywel Dda, sometimes anglicised as Howel the Good, or Hywel ap Cadell (died 949/950) was a king of Deheubarth who eventually came to rule most of Wales. He became the sole king of Seisyllwg in 920 and shortly thereafter established Deheubarth ...

included provisions dealing with slaves. In the Germanic realms, laws instituted the enslavement of criminals, such as the Visigothic Code

The ''Visigothic Code'' ( la, Forum Iudicum, Liber Iudiciorum; es, Fuero Juzgo, ''Book of the Judgements''), also called ''Lex Visigothorum'' (English: ''Law of the Visigoths''), is a set of laws first promulgated by king Chindasuinth (642–65 ...

’s prescribing enslavement for criminals who could not pay financial penalties for their crimes and as an actual punishment for various other crimes. Such criminals would become slaves to their victims, often with their property.

As these peoples Christianized

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

, the church worked more actively to reduce the practice of holding coreligionists in bondage. St. Patrick

ST, St, or St. may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Stanza, in poetry

* Suicidal Tendencies, an American heavy metal/hardcore punk band

* Star Trek, a science-fiction media franchise

* Summa Theologica, a compendium of Catholic philosophy an ...

, who himself was captured and enslaved at one time, protested an attack that enslaved newly baptized Christians in his letter to the soldiers of Coroticus. The restoration of order and the growing power of the church slowly transmuted the late Roman slave system of Diocletian into serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which deve ...

.

Another major factor was the rise of Bathilde Bathilde is a Germanic given name, with variants as Bathilda, Balthild, Bathildis' or Böðvildr. It may refer to:

Persons

*Böðvildr, Germanic legendary character

*Balthild of Chelles (626–680), Merovingian queen

*Bathilde d'Orléans (1750– ...

, queen of the Franks, who had been enslaved before marrying Clovis II

Clovis II (633 – 657) was King of Neustria and Burgundy, having succeeded his father Dagobert I in 639. His brother Sigebert III had been King of Austrasia since 634. He was initially under the regency of his mother Nanthild until her ...

. When she became regent, her government outlawed slave-trading of Christians throughout the Merovingian

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from the middle of the 5th century until 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the Franks and northern Gauli ...

empire.

About 10% of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

’s population entered in the Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manus ...

(1086) were slaves, despite chattel slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

of English Christians being nominally discontinued after the 1066 conquest. It is difficult to be certain about slave numbers, however, since the old Roman word for slave (''servus'') continued to be applied to unfree people whose status later was reflected by the term ''serf''.Perry Anderson, ''Passages from antiquity to feudalism'' (1996) p 141

Slave trade

Demand from the Islamic world dominated the slave trade in medieval Europe.''Slavery, Slave Trade.'' ed. Strayer, Joseph R. Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Volume 11. New York: Scribner, 1982. For most of that time, however, sale of Christian slaves to non-Christians was banned. In the ''pactum Lotharii

The ''Pactum Lotharii'' was an agreement signed on 23 February 840, between Republic of Venice and the Carolingian Empire, during the respective governments of Pietro Tradonico and Lothair I. This document was one of the first acts to testify to ...

'' of 840 between Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

and the Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the ...

, Venice promised not to buy Christian slaves in the Empire, and not to sell Christian slaves to Muslims.Il ''pactum Lotharii'' del 840 Cessi, Roberto. (1939–1940) – In: Atti. Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, Classe di Scienze Morali e Lettere Ser. 2, vol. 99 (1939–40) p. 11–49 The Church prohibited the export of Christian slaves to non-Christian lands, for example in the Council of Koblenz in 922, the Council of London in 1102, and the Council of Armagh in 1171.

As a result, most Christian slave merchants focused on moving them from non-Christian areas to Muslim Spain, North Africa, and the Middle East, and most non-Christian merchants, although not bound by the Church’s rules, focused on Muslim markets as well. Arabic silver dirhams, presumably exchanged for slaves, are plentiful in eastern Europe and Southern Sweden, indicating trade routes from Slavic to Muslim territory.

Italian merchants

By the reign of Pope Zachary (741–752),Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

had established a thriving slave trade, buying in Italy, among other places, and selling to the Moors in Northern Africa (Zacharias himself reportedly forbade such traffic out of Rome). When the sale of Christians to Muslims was banned (''pactum Lotharii

The ''Pactum Lotharii'' was an agreement signed on 23 February 840, between Republic of Venice and the Carolingian Empire, during the respective governments of Pietro Tradonico and Lothair I. This document was one of the first acts to testify to ...

''), the Venetians began to sell Slavs and other Eastern European non-Christian slaves in greater numbers. Caravans of slaves traveled from Eastern Europe, through Alpine passes in Austria, to reach Venice. A record of tolls paid in Raffelstetten (903–906), near St. Florian on the Danube, describes such merchants. Some are Slavic themselves, from Bohemia and the Kievan Rus'. They had come from Kiev through Przemyśl, Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

, Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and List of cities in the Czech Republic, largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 milli ...

, and Bohemia. The same record values female slaves at a '' tremissa'' (about 1.5 grams of gold or roughly of a dinar) and male slaves, who were more numerous, at a ''saiga'' (which is much less).MGH, Leges, Capitularia regum Francorum, II, ed. by A. Boretius, Hanovre, 1890, p. 250–25(available on-line)

Eunuchs were especially valuable, and "castration houses" arose in Venice, as well as other prominent slave markets, to meet this demand. Venice was far from the only slave trading hub in Italy. Southern Italy boasted slaves from distant regions, including Greece, Bulgaria, Armenia, and Slavic regions. During the 9th and 10th centuries,

Amalfi

Amalfi (, , ) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Salerno, in the region of Campania, Italy, on the Gulf of Salerno. It lies at the mouth of a deep ravine, at the foot of Monte Cerreto (1,315 metres, 4,314 feet), surrounded by dramati ...

was a major exporter of slaves to North Africa. Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

, along with Venice, dominated the trade in the Eastern Mediterranean beginning in the 12th century, and in the Black Sea beginning in the 13th century. They sold both Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

and Slavic slaves, as well as Armenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, '' hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diasp ...

, Circassians

The Circassians (also referred to as Cherkess or Adyghe; Adyghe and Kabardian: Адыгэхэр, romanized: ''Adıgəxər'') are an indigenous Northwest Caucasian ethnic group and nation native to the historical country-region of Circassia ...

, Georgians, Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic languages

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic ...

and other ethnic groups of the Black Sea and Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia (country), Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range ...

, to the Muslim nations of the Middle East. Genoa primarily managed the slave trade from Crimea to Mamluk Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

, until the 13th century, when increasing Venetian control over the Eastern Mediterranean allowed Venice to dominate that market.Janet L. Abu-Lughod, ''Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250–1350'' Oxford University Press Between 1414 and 1423 alone, at least 10,000 slaves were sold in Venice.

Iberia

A ready market, especially for men of fighting age, could be found in Umayyad Spain, with its need for supplies of new mamelukes.Al-Hakam was the first monarch of this family who surrounded his throne with a certain splendour and magnificence. He increased the number of mamelukes (slave soldiers) until they amounted to 5,000 horse and 1,000 foot. ... he increased the number of his slaves, eunuchs and servants; had a bodyguard of cavalry always stationed at the gate of his palace and surrounded his person with a guard of mamelukes .... these mamelukes were called Al-l;Iaras (the Guard) owing to their all being Christians or foreigners. They occupied two large barracks, with stables for their horses.According to

Roger Collins

Roger J. H. Collins (born September 2, 1949) is an English medievalist, currently an honorary fellow in history at the University of Edinburgh.

Collins studied at the University of Oxford ( Queen's and Saint Cross Colleges) under Peter Bro ...

although the role of the Vikings in the slave trade in Iberia remains largely hypothetical, their depredations are clearly recorded. Raids on AlAndalus by Vikings are reported in the years 844, 859, 966 and 971, conforming to the general pattern of such activity concentrating in the mid ninth and late tenth centuries. Muslim Spain

Al-Andalus DIN 31635, translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=Berber languages, Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, ...

imported an enormous number of slaves, as well as serving as a staging point for Muslim and Jewish merchants to market slaves to the rest of the Islamic world.Olivia Remie Constable (1996). Trade and Traders in Muslim Spain: The Commercial Realignment of the Iberian Peninsula, 900–1500

'. Cambridge University Press. pp. 203–204. During the reign of Abd-ar-Rahman III (912–961), there were at first 3,750, then 6,087, and finally 13,750

Saqaliba

Saqaliba ( ar, صقالبة, ṣaqāliba, singular ar, صقلبي, ṣaqlabī) is a term used in medieval Arabic sources to refer to Slavs and other peoples of Central, Southern, and Eastern Europe, or in a broad sense to European slaves. The t ...

, or Slavic slaves, at Córdoba, capital of the Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

.

Ibn Hawqal

Muḥammad Abū’l-Qāsim Ibn Ḥawqal (), also known as Abū al-Qāsim b. ʻAlī Ibn Ḥawqal al-Naṣībī, born in Nisibis, Upper Mesopotamia; was a 10th-century Arab Muslim writer, geographer, and chronicler who travelled during the ye ...

, Ibrahim al-Qarawi, and Bishop Liutprand of Cremona

Liutprand, also Liudprand, Liuprand, Lioutio, Liucius, Liuzo, and Lioutsios (c. 920 – 972),"LIUTPRAND OF CREMONA" in '' The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium'', Oxford University Press, New York & Oxford, 1991, p. 1241. was a historian, diplomat, ...

note that the Jewish merchants of Verdun specialized in castrating slaves, to be sold as eunuch saqaliba, which were enormously popular in Muslim Spain.

Vikings

The Nordic countries called their slaves ''

The Nordic countries called their slaves ''thrall

A thrall ( non, þræll, is, þræll, fo, trælur, no, trell, træl, da, træl, sv, träl) was a slave or serf in Scandinavian lands during the Viking Age. The corresponding term in Old English was . The status of slave (, ) contrasts wi ...

s'' (Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlemen ...

: ''Þræll''). There were also other terms used to describe thralls based on gender, such as ambatt/ambott and deja. Ambott is used in reference to female slaves, as is deja. Another name that is indicative of thrall status is bryti, which has associations with food. The word can be understood to mean, cook, and to break bread, which would place a person with this label as the person in charge of food in some manner. There is a runic inscription that describes a man of bryti status named Tolir who was able to marry and acted as the king’s estate manager. Another name is muslegoman, which would have been used for a runaway slave. From this, it can be gathered that the different names for those who were thralls indicate position and duties performed.

A fundamental part of Viking activity was the sale and taking of captives. The thralls were mostly from Western Europe, among them many Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

, Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

, and Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancien ...

.

Many Irish slaves were brought on expeditions for the colonization of Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

.

Raids on monasteries provided a source of young, educated slaves who could be sold in Venice or Byzantium for high prices.

Scandinavian trade centers stretched eastwards from Hedeby

Hedeby (, Old Norse ''Heiðabýr'', German ''Haithabu'') was an important Danish Viking Age (8th to the 11th centuries) trading settlement near the southern end of the Jutland Peninsula, now in the Schleswig-Flensburg district of Schleswig-Holst ...

in Denmark and Birka

Birka (''Birca'' in medieval sources), on the island of Björkö (lit. "Birch Island") in present-day Sweden, was an important Viking Age trading center which handled goods from Scandinavia as well as many parts of the European continent and ...

in Sweden to Staraya Ladoga

Staraya Ladoga (russian: Ста́рая Ла́дога, p=ˈstarəjə ˈladəɡə, lit=Old Ladoga), known as Ladoga until 1704, is a rural locality (a '' selo'') in Volkhovsky District of Leningrad Oblast, Russia, located on the Volkhov River ne ...

in northern Russia before the end of the 8th century. The collection of slaves was a by-product of conflict. The Annals of Fulda recorded that Franks who had been defeated by a group of Vikings in 880 CE were taken as captives after being defeated. Viking groups would have political conflicts that also resulted in the taking of captives.

This traffic continued into the 9th century as Scandinavians founded more trade centers at Kaupang in southwestern Norway and Novgorod, farther south than Staraya Ladoga, and Kiev, farther south still and closer to Byzantium. Dublin and other northwestern European Viking settlements were established as gateways through which captives were traded northwards.Thralls could be bought and sold at slave markets. An account from the Laxdoela Saga spoke of how during the 10th century there would be a meeting of kings every third year on The Branno Islands where negotiations and trades for slaves would take place. Though slaves could be bought and sold, it was more common to sell captives from other nations.

The 10th-century Persian traveller Ibn Rustah

Ahmad ibn Rustah Isfahani ( fa, احمد ابن رسته اصفهانی ''Aḥmad ibn Rusta Iṣfahānī''), more commonly known as Ibn Rustah (, also spelled ''Ibn Rusta'' and ''Ibn Ruste''), was a tenth-century Persian explorer and geographer ...

described how Swedish Vikings, the Varangians

The Varangians (; non, Væringjar; gkm, Βάραγγοι, ''Várangoi'';Varangian

" Online Etymo ...

or " Online Etymo ...

Rus

Rus or RUS may refer to:

People and places

* Rus (surname), a Romanian-language surname

* East Slavic historical territories and peoples (). See Names of Rus', Russia and Ruthenia

** Rus' people, the people of Rus'

** Rus' territories

*** Kievan ...

, terrorized and enslaved the Slavs taken in their raids along the Volga River.

Slaves were often sold south, to Byzantine or Muslim buyers, via paths such as the Volga trade route

In the Middle Ages, the Volga trade route connected Northern Europe and Northwestern Russia with the Caspian Sea and the Sasanian Empire, via the Volga River. The Rus used this route to trade with Muslim countries on the southern shores of the ...

.

Ahmad ibn Fadlan

Aḥmad ibn Faḍlān ibn al-ʿAbbās ibn Rāšid ibn Ḥammād, ( ar, أحمد بن فضلان بن العباس بن راشد بن حماد; ) commonly known as Ahmad ibn Fadlan, was a 10th-century Muslim traveler, famous for his account of hi ...

of Baghdad provides an account of the other end of this trade route, namely of Volga Vikings selling Slavic slaves to middle-eastern merchants.

Finland proved another source for Viking slave raids.

Slaves from Finland or Baltic states were traded as far as central Asia. Captives may have been traded far within the Viking trade network, and within that network, it was possible to be sold again. In the Life of St. Findan, the Irishman was bought and sold three times after being taken captive by a Viking group.

Mongols

TheMongol invasions

The Mongol invasions and conquests took place during the 13th and 14th centuries, creating history's largest contiguous empire: the Mongol Empire ( 1206-1368), which by 1300 covered large parts of Eurasia. Historians regard the Mongol devastatio ...

and conquests in the 13th century added a new force in the slave trade. The Mongols enslaved skilled individuals, women

A woman is an adult female human. Prior to adulthood, a female human is referred to as a girl (a female child or adolescent). The plural ''women'' is sometimes used in certain phrases such as "women's rights" to denote female humans regardl ...

and children and marched them to Karakorum

Karakorum (Khalkha Mongolian: Хархорум, ''Kharkhorum''; Mongolian Script:, ''Qaraqorum''; ) was the capital of the Mongol Empire between 1235 and 1260 and of the Northern Yuan dynasty in the 14–15th centuries. Its ruins lie in th ...

or Sarai, whence they were sold throughout Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelago ...

. Many of these slaves were shipped to the slave market in Novgorod.

Genoese and Venetians merchants in Crimea were involved in the slave trade with the Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, 'Great State' in Turkic, was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the fragme ...

. In 1441, Haci I Giray declared independence from the Golden Horde and established the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate ( crh, , or ), officially the Great Horde and Desht-i Kipchak () and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary ( la, Tartaria Minor), was a Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the long ...

. In the time of the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate ( crh, , or ), officially the Great Horde and Desht-i Kipchak () and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary ( la, Tartaria Minor), was a Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the long ...

, Crimeans engaged in frequent raids into the Danubian principalities, Poland-Lithuania, and Muscovy Muscovy is an alternative name for the Grand Duchy of Moscow (1263–1547) and the Tsardom of Russia (1547–1721). It may also refer to:

*Muscovy Company, an English trading company chartered in 1555

* Muscovy duck (''Cairina moschata'') and Domes ...

. For each captive, the khan received a fixed share (savğa) of 10% or 20%. The campaigns by Crimean forces categorize into "sefers", officially declared military operations led by the khans themselves, and ''çapuls'', raids undertaken by groups of noblemen, sometimes illegally because they contravened treaties concluded by the khans with neighbouring rulers. For a long time, until the early 18th century, the khanate maintained a massive Slave Trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

with the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East. Caffa

uk, Феодосія, Теодосія crh, Kefe

, official_name = ()

, settlement_type=

, image_skyline = THEODOSIA 01.jpg

, imagesize = 250px

, image_caption = Genoese fortress of Caffa

, image_shield = Fe ...

was one of the best known and significant trading ports and slave markets. Crimean Tatar raiders enslaved more than 1 million Eastern Europeans.

England and Ireland

In medievalIreland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, as a commonly traded commodity slaves could, like cattle, become a form of internal or trans-border currency. In 1102, the Council of London convened by Anselm of Canterbury obtained a resolution against the slave trade in England which was aimed mainly at the sale of English slaves to the Irish.

Christians holding Muslim slaves

Although the primary flow of slaves was toward Muslim countries, as evident in thehistory of slavery in the Muslim world

The history of slavery in the Muslim world began with institutions inherited from pre-Islamic Arabia;Lewis 1994Ch.1 and the practice of keeping slaves subsequently developed in radically different ways, depending on social-political factors such ...

, Christians did acquire Muslim slaves; in Southern France, in the 13th century, "the enslavement of Muslim captives was still fairly common".

There are records, for example, of Saracen slave girls sold in Marseilles in 1248, a date which coincided with the fall of Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

and its surrounding area, to raiding Christian crusaders, an event during which a large number of Muslim women from this area were enslaved as war booty, as it has been recorded in some Arabic poetry, notably by the poet al-Rundi, who was contemporary to the events.

Additionally, the possession of slaves was legal in 13th century Italy; many Christians held Muslim slaves throughout the country. These Saracen slaves were often captured by pirates and brought to Italy from North Africa or Spain. During the 13th century, most of the slaves in the Italian trade city of Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

were of Muslim origin. These Muslim slaves were owned by royalty, military orders or groups, independent entities, and the church itself.

Christians also sold Muslim slaves captured in war. The Order of the Knights of Malta attacked pirates and Muslim shipping, and their base became a center for slave trading, selling captured North Africans

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in t ...

and Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic languages

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic ...

. Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

remained a slave market until well into the late 18th century. One thousand slaves were required to man the galleys (ships) of the Order.

While they would at times seize Muslims as slaves, it was more likely that Christian armies would kill their enemies, rather than take them into servitude.

Jewish slave trade

The role of Jewish merchants in the early medieval slave trade has been subject to much misinterpretation and distortion. Although medieval records demonstrate that there were Jews who owned slaves in medieval Europe, Toch (2013) notes that the claim repeated in older sources, such as those by Charles Verlinden, that Jewish merchants where the primary dealers in European slaves is based off misreadings of primary documents from that era. Contemporary Jewish sources do not attest any a large-scale slave trade or ownership of slaves which may be distinguished from the wider phenomenon of early medieval European slavery. The trope of the Jewish dealer of Christian slaves was additionally a prominent image in medieval Europe anti-Semitic propaganda.Slave trade at the close of the Middle Ages

As more and more of EuropeChristianized

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

, and open hostilities between Christian and Muslim nations intensified, large-scale slave trade moved to more distant sources.

Sending slaves to Egypt, for example, was forbidden by the papacy in 1317, 1323, 1329,

1338, and, finally, 1425, as slaves sent to Egypt would often become soldiers, and end up fighting their former Christian owners.

Although the repeated bans indicate that such trade still occurred, they also indicate that it became less desirable.

In the 16th century, African slaves replaced almost all other ethnicities and religious enslaved groups in Europe.

Slavery in law

Secular law

Slavery was heavily regulated inRoman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Ju ...

, which was reorganized in the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

by Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renova ...

as the Corpus Iuris Civilis

The ''Corpus Juris'' (or ''Iuris'') ''Civilis'' ("Body of Civil Law") is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Byzantine Emperor. It is also sometimes referred ...

. Although the Corpus was lost to the West for centuries, it was rediscovered in the 11th and 12th centuries, and led to the foundation of law schools in Italy and France. According to the Corpus, the natural state of humanity is freedom, but the "law of nations" may supersede natural law and reduce certain people to slavery. The basic definition of slave in Romano-Byzantine law was:

*anyone whose mother was a slave

*anyone who has been captured in battle

*anyone who has sold himself to pay a debt

It was, however, possible to become a freedman or a full citizen; the Corpus, like Roman law, had extensive and complicated rules for manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

of slaves.

The slave trade in England was officially abolished in 1102.

In Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

slavery was forbidden in the 15th century; it was replaced by the second enserfment. In Lithuania, slavery was formally abolished in 1588.

Canon law

In fact, there was an explicit legal justification given for the enslavement of Muslims, found in theDecretum Gratiani

The ''Decretum Gratiani'', also known as the ''Concordia discordantium canonum'' or ''Concordantia discordantium canonum'' or simply as the ''Decretum'', is a collection of canon law compiled and written in the 12th century as a legal textbook b ...

and later expanded upon by the 14th century jurist Oldradus de Ponte Oldradus de Ponte (died 1335) was an Italian jurist born in Lodi, active in the Roman curia in the early fourteenth century. Previously he had taught at the University of Padua. According to Joseph Canning''A History of Medieval Political Thought' ...

: the Bible states that Hagar

Hagar, of uncertain origin; ar, هَاجَر, Hājar; grc, Ἁγάρ, Hagár; la, Agar is a biblical woman. According to the Book of Genesis, she was an Egyptian slave, a handmaiden of Sarah (then known as ''Sarai''), whom Sarah gave to h ...

, the slave girl of Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Je ...

, was beaten and cast out by Abraham’s wife Sarah.

The Decretum, like the Corpus, defined a slave as anyone whose mother was a slave. Otherwise, the canons were concerned with slavery only in ecclesiastical contexts: slaves were not permitted to marry or to be ordained as clergy.

Slavery in the Byzantine Empire

Slavery in the Crusader states

As a result of the crusades, thousands of Muslims and Christians were sold into slavery. Once sold into slavery most were never heard from again, so it is challenging to find evidence of specific slave experiences. In the crusaderKingdom of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem ( la, Regnum Hierosolymitanum; fro, Roiaume de Jherusalem), officially known as the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem or the Frankish Kingdom of Palestine,Example (title of works): was a Crusader state that was establish ...

, founded in 1099, at most 120,000 Franks ruled over 350,000 Muslims, Jews, and native Eastern Christians. Following the initial invasion and conquest, sometimes accompanied by massacres or expulsions of Jews and Muslims, a peaceable co-existence between followers of the three religions prevailed. The Crusader states inherited many slaves. To this may have been added some Muslims taken as captives of war. The Kingdom’s largest city, Acre, had a large slave market; however, the vast majority of Muslims and Jews remained free. The laws of Jerusalem declared that former Muslim slaves, if genuine converts to Christianity, must be freed.

In 1120, the Council of Nablus

The Council of Nablus was a council of ecclesiastic and secular lords in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, held on January 16, 1120.

History

The council was convened at Nablus by Warmund, Patriarch of Jerusalem, and King Baldwin II of Jerusalem ...

forbade sexual relations between crusaders and their female Muslim slaves:Hans E. Mayer, "The Concordat of Nablus" (Journal of Ecclesiastical History

''The Journal of Ecclesiastical History'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal published by Cambridge University Press. It was established in 1950 and covers all aspects of the history of the Christian Church. It deals with the church bot ...

33 (October 1982)), pp. 531–533. if a man raped his own slave, he would be castrated, but if he raped someone else’s slave, he would be castrated and exiled from the kingdom. But Benjamin Z. Kedar argued that the canons of the Council of Nablus were in force in the 12th century but had fallen out of use by the thirteenth. Marwan Nader questions this and suggests that the canons may not have applied to the whole kingdom at all times.

Christian law mandated Christians could not enslave other Christians; however, enslaving non-Christians was acceptable. In fact, military orders frequently enslaved Muslims and used slave labor for agricultural estates. No Christian, whether Western or Eastern, was permitted by law to be sold into slavery, but this fate was as common for Muslim prisoners of war as it was for Christian prisoners taken by the Muslims. In the later medieval period, some slaves were used to oar Hospitaller ships. Generally, it was a relatively small number non-Christian slaves in medieval Europe, and this number significantly decreased by the end of the medieval period.

The 13th-century Assizes of Jerusalem

The Assizes of Jerusalem are a collection of numerous medieval legal treatises written in Old French containing the law of the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem and Kingdom of Cyprus. They were compiled in the thirteenth century, and are the largest c ...

dealt more with fugitive slaves and the punishments ascribed to them, the prohibition of slaves testifying in court, and manumission of slaves, which could be accomplished, for example, through a will, or by conversion to Christianity. Conversion was apparently used as an excuse to escape slavery by Muslims who would then continue to practise Islam; crusader lords often refused to allow them to convert, and Pope Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX ( la, Gregorius IX; born Ugolino di Conti; c. 1145 or before 1170 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decre ...

, contrary to both the laws of Jerusalem and the canon laws that he himself was partially responsible for compiling, allowed for Muslim slaves to remain enslaved even if they had converted.

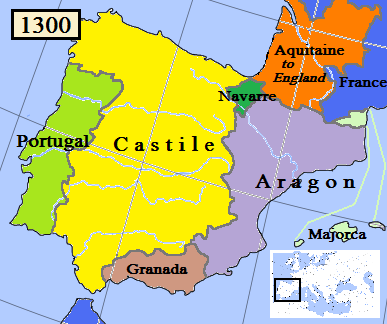

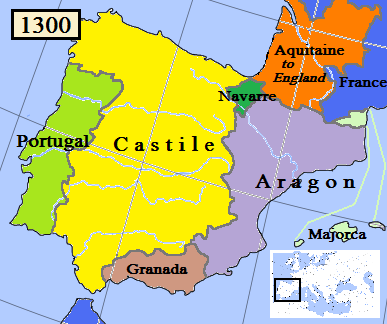

Slavery in Iberia

Communities of Muslims, Christians, and Jews existed on both sides of the political divide between Muslim and Christian kingdoms in Medieval Iberia: Al-Andalus hosted Jewish and Christian communities while Christian Iberia hosted Muslim and Jewish communities. Christianity had introduced the ethos that banned the enslavement of fellow Christians, an ethos that was reinforced by the banning of the enslavement of co-religionists during the rise of Islam. Additionally, the

Communities of Muslims, Christians, and Jews existed on both sides of the political divide between Muslim and Christian kingdoms in Medieval Iberia: Al-Andalus hosted Jewish and Christian communities while Christian Iberia hosted Muslim and Jewish communities. Christianity had introduced the ethos that banned the enslavement of fellow Christians, an ethos that was reinforced by the banning of the enslavement of co-religionists during the rise of Islam. Additionally, the Dar al-Islam

In classical Islamic law, the major divisions are ''dar al-Islam'' (lit. territory of Islam/voluntary submission to God), denoting regions where Islamic law prevails, ''dar al-sulh'' (lit. territory of treaty) denoting non-Islamic lands which have ...

protected ‘people of the book’ (Christians and Jews living in Islamic lands) from enslavement, an immunity which also applied to Muslims living in Christian Iberia. Despite these restrictions, criminal or indebted Muslims and Christians in both regions were still subject to judicially-sanctioned slavery.

Slavery in Al-Andalus

An early economic pillar of the Islamic empire in Iberia (Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

) during the eighth century was the slave trade. Due to manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

being a form of piety under Islamic law, slavery in Muslim Spain couldn’t maintain the same level of auto-reproduction as societies with older slave populations. Therefore, Al-Andalus relied on trade systems as an external means of replenishing the supply of enslaved people. Forming relations between the Umayyads, Khārijites and 'Abbāsids, the flow of trafficked people from the main routes of the Sahara towards Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

served as a highly lucrative trade configuration. The archaeological evidence of human trafficking and proliferation of early trade in this case follows numismatics and materiality of text. This monetary structure of consistent gold influx proved to be a tenet in the development of Islamic commerce. In this regard, the slave trade outperformed and was the most commercially successful venture for maximizing capital. This major change in the form of numismatics serves as a paradigm shift from the previous Visigothic economic arrangement. Additionally, it demonstrates profound change from one regional entity to another, the direct transfer of people and pure coinage from one religiously similar semi-autonomous province to another.

The medieval Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

was the scene of episodic warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regul ...

among Muslims and Christians (although sometimes Muslims and Christians were allies). Periodic raiding expeditions were sent from Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

to ravage the Christian Iberian kingdoms, bringing back booty and people. For example, in a raid on Lisbon in 1189 the Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire fou ...

caliph Yaqub al-Mansur

Abū Yūsuf Yaʿqūb ibn Yūsuf ibn Abd al-Muʾmin al-Manṣūr (; c. 1160 – 23 January 1199 Marrakesh), commonly known as Yaqub al-Mansur () or Moulay Yacoub (), was the third Almohad Caliph. Succeeding his father, al-Mansur reigned from 11 ...

took 3,000 female and child captives, and his governor of Córdoba took 3,000 Christian slaves in a subsequent attack upon Silves in 1191; an offensive by Alfonso VIII of Castile in 1182 brought him over two-thousand Muslim slaves. These raiding expeditions also included the Sa’ifa (summer) incursions, a tradition produced during the Amir reign of Cordoba. In addition to acquiring wealth, some of these Sa’ifa raids sought to bring mostly male captives, often eunuchs, back to Al-Andalus. They were generically referred to as Saqaliba

Saqaliba ( ar, صقالبة, ṣaqāliba, singular ar, صقلبي, ṣaqlabī) is a term used in medieval Arabic sources to refer to Slavs and other peoples of Central, Southern, and Eastern Europe, or in a broad sense to European slaves. The t ...

, the Arab word for Slavs. Slavs’ status as the most common group in the slave trade by the tenth century led to the development of the word “slave.” The Saqaliba were mostly assigned to palaces as guards, concubines, and eunuchs, although they were sometimes privately owned. Along with Christians and Slavs, Sub-Saharan Africans were also held as slaves, brought back from the caravan trade in the Sahara. Slaves in Islamic lands were generally used for domestic, military, and administrative purposes, rarely used for agriculture or large-scale manufacturing. Christians living in Al-Andalus were not allowed to hold authority over Muslims, but they were permitted to hold non-Muslim slaves.

Slavery in Christian Iberia

Contrary to suppositions of historians such asMarc Bloch

Marc Léopold Benjamin Bloch (; ; 6 July 1886 – 16 June 1944) was a French historian. He was a founding member of the Annales School of French social history. Bloch specialised in medieval history and published widely on Medieval France ov ...

, slavery thrived as an institution in medieval Christian Iberia. Slavery existed in the region under the Romans, and continued to do so under the Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is ...

. From the fifth to the early 8th century, large portions of the Iberian Peninsula were ruled by Christian Visigothic Kingdoms, whose rulers worked to codify human bondage. In the 7th century, King Chindasuinth issued the Visigothic Code

The ''Visigothic Code'' ( la, Forum Iudicum, Liber Iudiciorum; es, Fuero Juzgo, ''Book of the Judgements''), also called ''Lex Visigothorum'' (English: ''Law of the Visigoths''), is a set of laws first promulgated by king Chindasuinth (642–65 ...

(Liber Iudiciorum), to which subsequent Visigothic kings added new legislation. Although the Visigothic Kingdom collapsed in the early 8th century, portions of the Visigothic Code were still observed in parts of Spain in the following centuries. The Code, with its pronounced and frequent attention to the legal status of slaves, reveals the continuation of slavery as an institution in post-Roman Spain.

The Code regulated the social conditions, behavior, and punishments of slaves in early medieval Spain. The marriage of slaves and free or freed people was prohibited. Book III, title II, iii ("Where a Freeborn Woman Marries the Slave of Another or a Freeborn Man the Female Slave of Another") stipulates that if a free woman marries another person’s slave, the couple is to be separated and given 100 lashes. Furthermore, if the woman refuses to leave the slave, then she becomes the property of the slave’s master. Likewise, any children born to the couple would follow the father’s condition and be slaves.

Unlike Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Ju ...

, in which only slaves were liable to corporal punishment, under Visigothic law, people of any social status were subject to corporal punishment. However, the physical punishment, typically beatings, administered to slaves was consistently harsher than that administered to freed or free people. Slaves could also be compelled to give testimony under torture. For example, slaves could be tortured to reveal the adultery of their masters, and it was illegal to free a slave for fear of what he or she might reveal under torture. Slaves' greater liability to physical punishment and judicial torture suggests their inferior social status in the eyes of Visigothic lawmakers.

Slavery remained persistent in Christian Iberia after the Umayyad invasions in the 8th century, and the Visigothic law codes continued to control slave ownership. However, as William Phillips notes, medieval Iberia should not be thought of as a slave society, but rather as a society that owned slaves. Slaves accounted for a relatively small percentage of the population, and did not make up a significant portion of the labor pool. Furthermore, while the existence of slavery continued from the earlier period, the use of slaves in post-Visigothic Christian Iberia differed from early periods. Ian Wood has suggests that, under the Visigoths, the majority of the slave population lived and worked on rural estates.

After the Muslim invasions, slave owners (especially in the kingdoms of Aragon and Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

) moved away from using slaves as field laborers or in work gangs, and did not press slaves into military service.Phillips p.19 Slaves tended to be owned singly rather than in large groups. There appear to have been many more female than male slaves, and they were most often used as domestic servants, or to supplement free labor. In this respect, slave institutions in Aragon, especially, closely resembled those of other Mediterranean Christian kingdoms in France and Italy.

In the kingdoms of León and Castile, slavery followed the Visigothic model more closely than in the littoral kingdoms. Slaves in León and Castile were more likely to be employed as field laborers, supplanting free labor to support an aristocratic estate society. These trends in slave populations and use changed in the wake of the Black Death in 1348, which significantly increased the demand for slaves across the whole of the peninsula.

Christians were not the only slaveholders in Christian Iberia. Both Jews and Muslims living under Christian rule owned slaves, though more commonly in Aragon and Valencia than in Castile. After the conquest of Valencia in 1245, the Kingdom of Aragon prohibited the possession of Christian slaves by Jews, though they were still permitted to hold Muslim or pagan slaves. The main role of Iberian Jews in the slave trade came as facilitators: Jews acted as slave brokers and agents of transfer between the Christian and Muslim kingdoms.

This role caused some degree of fear among Christian populations. A letter from Pope Gregory XI

Pope Gregory XI ( la, Gregorius, born Pierre Roger de Beaufort; c. 1329 – 27 March 1378) was head of the Catholic Church from 30 December 1370 to his death in March 1378. He was the seventh and last Avignon pope and the most recent French pop ...

to the Bishop of Cordoba in 1239 addressed rumors that the Jews were involved in kidnapping and selling Christian women and children into slavery while their husbands were away fighting the Muslims.Roth p.160 Despite these worries, the primary role of Jewish slave traders lay in facilitating the exchange of captives between Muslim and Christian rulers, one of the primary threads of economic and political connectivity between Christian and Muslim Iberia.

In the early period after the fall of the Visigothic kingdom in the 8th century, slaves primarily came into Christian Iberia through trade with the Muslim kingdoms of the south. Most were Eastern European, captured in battles and raids, with the heavy majority being Slavs. However, the ethnic composition of slaves in Christian Iberia shifted over the course of the Middle Ages. Slaveholders in the Christian kingdoms gradually moved away from owning Christians, in accordance with Church proscriptions. In the middle of the medieval period most slaves in Christian Iberia were Muslim, either captured in battle with the Islamic states from the southern part of the peninsula, or taken from the eastern Mediterranean and imported into Iberia by merchants from cities such as Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

.

The Christian kingdoms of Iberia frequently traded their Muslim captives back across the border for payments of money or kind. Indeed, historian James Broadman writes that this type of redemption offered the best chance for captives and slaves to regain their freedom. The sale of Muslim captives, either back to the Islamic southern states or to third-party slave brokers, supplied one of the means by which Aragon and Castile financed the Reconquista

The ' (Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid ...

. Battles and sieges provided large numbers of captives; after the siege of Almeria in 1147, sources report that Alfonso VII of León

Alphons (Latinized ''Alphonsus'', ''Adelphonsus'', or ''Adefonsus'') is a male given name recorded from the 8th century (Alfonso I of Asturias, r. 739–757) in the Christian successor states of the Visigothic kingdom in the Iberian peninsula. ...

sent almost 10,000 of the city’s Muslim women and children to Genoa to be sold into slavery as partial repayment of Genoese assistance in the campaign.

Towards the end of the Reconquista, however, this source of slaves became increasingly exhausted. Muslim rulers were increasingly unable to pay ransoms, and the Christian capture of large centers of population in the south made wholesale enslavement of Muslim populations impractical. The loss of an Iberian Muslim source of slaves further encouraged Christians to look to other sources of manpower. Beginning with the first Portuguese slave raid in sub-Saharan Africa in 1411, the focus of slave importation began to shift from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic World, and the racial composition of slaves in Christian Iberia began to include an increasing number of black Africans.

Between 1489 and 1497 almost 2,100 black slaves were shipped from Portugal to Valencia.Saunders p.29 By the end of the 15th century, Spain held the largest population of black Africans in Europe, with a small, but growing community of black ex-slaves. In the mid 16th century Spain imported up to 2,000 black African slaves annually through Portugal, and by 1565 most of Seville’s 6,327 slaves (out of a total population of 85,538) were black Africans.

Slavery in Moldavia and Wallachia

Slavery existed on the territory of present-dayRomania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

while under The Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

and Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

rulership, from before the founding of the principalities of Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and s ...

and Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and for ...

in 13th–14th century, until it was abolished in stages during the 1840s and 1850s before the independence of the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia

The United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia ( ro, Principatele Unite ale Moldovei și Țării Românești), commonly called United Principalities, was the personal union of the Principality of Moldavia and the Principality of Wallachia, ...

was allowed, and also until 1783, in Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

and Bukovina (parts of the Habsburg monarchy and later The Austria-Hungarian Empire). Most slaves were of Roma

Roma or ROMA may refer to:

Places Australia

* Roma, Queensland, a town

** Roma Airport

** Roma Courthouse

** Electoral district of Roma, defunct

** Town of Roma, defunct town, now part of the Maranoa Regional Council

*Roma Street, Brisbane, a ...

(Gypsy) ethnicity and a significant number of ''Rumâniin

Serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which deve ...

slavery.

Historian Nicolae Iorga

Nicolae Iorga (; sometimes Neculai Iorga, Nicolas Jorga, Nicolai Jorga or Nicola Jorga, born Nicu N. Iorga;Iova, p. xxvii. 17 January 1871 – 27 November 1940) was a Romanian historian, politician, literary critic, memoirist, Albanologist, poet ...

associated the Roma people’s arrival with the 1241 Mongol invasion of Europe

From the 1220s into the 1240s, the Mongols conquered the Turkic states of Volga Bulgaria, Cumania, Alania, and the Kievan Rus' federation. Following this, they began their invasion into heartland Europe by launching a two-pronged invasion of ...

and considered their slavery as a vestige of that era. The practice of enslaving prisoners may also have been taken from the Mongols. The ethnic identity of the "Tatar slaves" is unknown, they could have been captured Tatars of the Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, 'Great State' in Turkic, was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the fragme ...

, Cumans

The Cumans (or Kumans), also known as Polovtsians or Polovtsy (plural only, from the Russian exonym ), were a Turkic nomadic people comprising the western branch of the Cuman–Kipchak confederation. After the Mongol invasion (1237), many so ...

, or the slaves of Tatars and Cumans.

While it is possible that some Romani people were slaves or auxiliary troops of the Mongols or Tatars and Nogai Horde

The Nogai Horde was a confederation founded by the Nogais that occupied the Pontic–Caspian steppe from about 1500 until they were pushed west by the Kalmyks and south by the Russians in the 17th century. The Mongol tribe called the Manghuds co ...

, the bulk of them came from south of the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

at the end of the 14th century, some time before the foundation of Wallachia.

The Roma slaves were owned by the boyars

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Kievan Rus', Bulgaria, Russia, Wallachia and Moldavia, and later Romania, Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. Boyars wer ...

(see Wallachian Revolution of 1848

The Wallachian Revolution of 1848 was a Romanian liberal and nationalist uprising in the Principality of Wallachia. Part of the Revolutions of 1848, and closely connected with the unsuccessful revolt in the Principality of Moldavia, it sought ...

), the Christian Orthodox monasteries, or the state. They were used only as smiths, gold panners and as agricultural workers.

The Rumâni were only owned by Boyars

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Kievan Rus', Bulgaria, Russia, Wallachia and Moldavia, and later Romania, Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. Boyars wer ...

and Monasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

, until the Independence of Romania from the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

on 9th of May 1877. They were considered less valuable because they were taxable, only skilled at agricultural work and couldn't be used at tribute.

It was common for both boyars and monasteries to register their Romanian serfs as "Gypsies" so that they would not pay the taxes that were imposed on the serfs. Any Romanian, regardless of gender, marrying a Roma would immediately become a slave that could be used as tribute.

Slavery in the Medieval Near East

The ancient and medieval Near East includes modern day Turkey, the Levant and Egypt, with strong connections to the rest of the north African coastline. All of these areas were ruled by either the Byzantines or the Persians at the end of late antiquity. Pre-existing Byzantine (i.e. Roman) and Persian institutions of slavery may have influenced the development of institutions of slavery in Islamic law and jurisprudence. Likewise, some scholars have argued for the influence of Rabbinic tradition on the development of Islamic legal thought. Whatever the relationship between these different legal traditions, many similarities exist between the practice of Islamic slavery in the early Middle Ages and the practices of early medieval Byzantines and western Europeans. The status of freed slaves under Islamic rule, who continued to owe services to their former masters, bears a strong similarity to ancient Roman and Greek institutions. However, the practice of slavery in the early medieval Near East also grew out of slavery practices in currency among pre-Islamic Arabs. Like the Old and New Testaments and Greek and Roman law codes, the Quran takes the institution of slavery for granted, though it urges kindness toward slaves and eventual manumission, especially for slaves who convert to Islam. In early Middle Ages, many slaves in Islamic society served as such for only a short period of time—perhaps an average of seven years. Like their European counterparts, early medieval Islamic slave traders preferred slaves who were not co-religionists and hence focused on "pagans" from inner Asia, Europe, and especially from sub-Saharan Africa.Wright, 2007, p. 3. The practice of manumission may have contributed to the integration of former slaves into the wider society. However, under sharia law, conversion to Islam did not necessitate manumission. Slaves were employed in heavy labor as well as in domestic contexts. Because of Quranic sanction of concubinage, early Islamic traders, in contrast to Byzantine and early modern slave traders, imported large numbers of female slaves. The very earliest Islamic states did not create corps of slave soldiers (a practice familiar from later contexts) but did integrate freedmen into armies, which may have contributed to the rapid expansion of early Islamic conquest. By the 9th century, use of slaves in Islamic armies, particularly Turks in cavalry units and Africans in infantry units, was a relatively common practice. In Egypt, Ahmad ibn Tulun imported thousands of black slaves to wrestle independence from theAbbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

in Iraq in 868. The Ikhshidid dynasty

The Ikhshidid dynasty (, ) was a Turkic mamluk dynasty who ruled Egypt and the Levant from 935 to 969. Muhammad ibn Tughj al-Ikhshid, a Turkic mamluk soldier, was appointed governor by the Abbasid Caliph al-Radi. The dynasty carried the Arabic t ...

used black slave units to liberate itself from Abbasid rule after the Abbasids destroyed ibn Tulun’s autonomous empire in 935.Lev, David Ayalon Black professional soldiers were most associated with the Fatimid dynasty

The Fatimid dynasty () was an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty of Arab descent that ruled an extensive empire, the Fatimid Caliphate, between 909 and 1171 CE. Claiming descent from Fatima and Ali, they also held the Isma'ili imamate, claiming to be the r ...

, which incorporated more professional black soldiers than the previous two dynasties. It was the Fatimids who first incorporated black professional slave soldiers into the cavalry, despite massive opposition from Central Asian Turkish Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

s, who saw the African contingent as a threat to their role as the leading military unit in the Egyptian army.

In the later half of the Middle Ages, the expansion of Islamic rule further into the Mediterranean, the Persian Gulf, and Arabian Peninsula established the Saharan-Indian Ocean slave trade.

This network was a large market for African slaves, transporting approximately four million African slaves from its 7th century inception to its 20th century demise. Ironically, the consolidation of borders in the Islamic Near East changed the face of the slave trade.Lewis, Race and Slavery A rigid Islamic code, coupled with crystallizing frontiers, favored slave purchase and tribute over capture as lucrative slave avenues. Even the sources of slaves shifted from the Fertile Crescent and Central Asia to Indochina and the Byzantine Empire.

Patterns of preference for slaves in the Near East, as well as patterns of use, continued into the later Middle Ages with only slight changes. Slaves were employed in many activities, including agriculture, industry, the military, and domestic labor. Women were prioritized over men, and usually served in the domestic sphere as menials, concubines (''cariye

Cariye (, " Jariya") was a title and term used for category of enslaved women concubines in the Islamic world of the Middle East.Junius P. Rodriguez: Slavery in the Modern World: A History of Political, Social, and Economic' They are particularl ...

''), or wives.Lewis, ''Race and Slavery'', p. 14

Domestic and commercial slaves were mostly better off than their agricultural counterparts, either becoming family members or business partners rather than condemned to a grueling life in a chain gang. There are references to gangs of slaves, mostly African, put to work in drainage projects in Iraq, salt and gold mines in the Sahara, and sugar and cotton plantations in North Africa and Spain. References to this latter type of slavery are rare, however. Eunuchs were the most prized and sought-after type of slave.

The most fortunate slaves found employment in politics or the military. In the Ottoman Empire, the Devşrime system groomed young slave boys for civil or military service. Young Christian boys were uprooted from their conquered villages periodically as a levy, and were employed in government, entertainment, or the army, depending on their talents. Slaves attained great success from this program, some winning the post of Grand Vizier to the Sultan and others positions in the Janissaries.

It is a bit of a misnomer to classify these men as "slaves", because in the Ottoman Empire, they were referred to as kul, or, slaves "of the Gate", or Sultanate. While not slaves per se under Islamic law, these Devşrime alumni remained under the Sultan’s discretion.

The Islamic Near East extensively relied upon professional slave soldiers, and was known for having them compose the core of armies. The institution was conceived out of political predicaments and reflected the attitudes of the time, and was not indicative of political decline or financial bankruptcy. Slave units were desired because of their unadulterated loyalty to the ruler, since they were imported and therefore could not threaten the throne with local loyalties or alliances.

Slavery in the Mediterranean